Psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, are a group of severe mental disorders with an estimated mean lifetime prevalence of 1.94%. Reference Perälä, Suvisaari, Saarni, Kuoppasalmi, Isometsä and Pirkola1 Bipolar I disorder is an affective disorder with an estimated lifetime prevalence of 1–3.3%. Reference Rowland and Marwaha2,Reference Hasin and Grant3 Both disorders are considered leading mental health causes of disability according to the Global Burden of Disease study. 4 One critical prognostic indicator for functional, cognitive and quality of life outcomes in people with such disorders is the frequency of hospital readmissions. Reference Cardoso, Bauer, Meyer, Kapczinski and Soares5 Readmission rates also serve as a widely recognised marker for assessing the quality of mental health services, especially in the management of psychotic disorders. Reference Suokas, Lindgren, Gissler, Liukko, Schildt and Salokangas6,Reference Patel, Pilon, Gupta, Morrison, Lafeuille and Lefebvre7 Evidence suggest that coordinated and effective transition from in-patient to out-patient mental healthcare significantly reduces the risk of readmission among patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Reference Marcus, Chuang, Ng-Mak and Olfson8 Community-based mental health services remain the cornerstone of the ongoing care and rehabilitation of individuals with chronic and severe mental disorder. A substantial body of literature supports their effectiveness in improving clinical outcomes and reducing readmission rates. Reference Wanchek, McGarvey, Leon-Verdin and Bonnie9–Reference Barnett, Gonzalez, Miranda, Chavira and Lau15 Although much of the existing research has focused on urban areas, a growing number of studies have begun to address mental health services in rural and remote areas. The delivery of mental healthcare in these areas is often described as a complex issue, influenced by a range of factors, including stigma, limited availability of services, inconsistent implementation of policies and the social exclusion of people with mental disorders. Reference Nicholson12,Reference Barnett, Gonzalez, Miranda, Chavira and Lau15

Mobile mental health units in rural Greece

In Greece, a significant proportion of the population lives in remote or rural regions characterised by lower socioeconomic status and restricted access to mental health services. To address the needs of people living in underserved areas, mobile mental health units (MMHUs) have been established as a decentralised model of community mental healthcare. These units aim to prevent relapses and effectively manage regular psychiatric follow-up of individuals with severe mental illness. Reference Peritogiannis and Mavreas16 Two studies, based on relatively small samples of patients living in northern rural Greece, have demonstrated the effectiveness of MMHUs in reducing both total and involuntary readmissions. Reference Garbi, Tiniakos, Mikelatou and Drakatos17–Reference Peritogiannis, Fragouli-Sakellaropoulou, Stavrogiannopoulos, Filla, Garmpi and Pantelidou19

Crete, the largest island in southern Greece, has a population of approximately 630 000 residents and is predominantly sustained by agriculture and tourism. 20 The island has a unique combination of geographical and sociocultural features, including numerous remote villages with high levels of illiteracy and tightly knit families, often extended to include hundreds of members bound to offer strong intra-familial support. Reference Chereji and Tsantiropopulos21 Notably, Crete reports suicide rates that are twice the national average and mental health resources remain scarce, particularly in the eastern part of the island. Reference Basta, Vgontzas, Kastanaki, Michalodimitrakis, Kanaki and Koutra22 To address these disparities, the School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Crete (PAGNH) established an MMHU to provide psychiatric care to underserved populations in the inland region of the Heraklion District, where access to both public and private mental health professionals is minimal or entirely absent. The Psychiatric Unit at PAGNH initiated the operation of a pilot MMHU in 2013, with the goal of gradually covering the mental health needs of approximately 120 000 residents in rural and semi-rural areas of this inland region. The MMHU aimed to prevent and promptly intervene in severe mental illness, as well as to provide diagnosis and appropriate management. Reference Paschalidou, Anastasaki, Zografaki, Krasanaki, Daskalaki and Chatziorfanos23 Today, this MMHU operates through regular visits to seven community healthcare centres, serving a population of over 120 000 citizens in rural and semi-rural areas of Heraklion. Reference Paschalidou, Anastasaki, Zografaki, Krasanaki, Daskalaki and Chatziorfanos23

The current study

The overall goal of this study was to examine the effectiveness of the Heraklion MMHU in reducing hospital readmissions among individuals diagnosed with psychosis or bipolar disorder living in its catchment area. The first objective was to compare total and involuntary admission rates before and after treatment by the MMHU. The second objective was to explore sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with changes in patients’ readmissions, with the goal of identifying potential predictors of reduced readmissions. Collectively, these outcomes were expected to provide valuable insight into the clinical impact of this community-based model and to further reinforce the importance of preserving and further developing its operation in the underserved rural areas of Heraklion.

Method

Participants

Participants were individuals who were treated by the MMHU between January 2013 and December 2022. Inclusion criteria were: (a) a confirmed diagnosis of psychosis or bipolar I disorder, (b) age over 15 years and (c) regular follow-up by the MMHU for a minimum of 12 months. Exclusion criteria were: (a) follow-up initiated in 2023, (b) death or relocation outside the Heraklion region, (c) diagnosis of a psychotic disorder secondary to a general medical condition, (d) substance- or medication-induced psychotic disorder and (e) moderate to severe intellectual developmental disorder. Out of 660 patients with a diagnosis of psychosis or bipolar disorder who visited the MMHU during the years 2013–2023, 288 met the inclusion criteria. Among the excluded patients, approximately 21% had died (including death by suicide), 30% had transitioned to care by private psychiatrists or other public services in urban areas, 18% had relocated, 26% had insufficient duration of follow-up and 5% lacked essential clinical/administrative data. The final sample had a mean age of 48 years (s.d. = 12.85 years) and 187 (64.9%) were male. Of the total sample, 201 (69.8%) were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder and 87 (30.2%) with bipolar I disorder. The mean duration of pre- and post-MMHU follow-up was 5.4 years (s.d. = 2.9 years) and ranged from 1 to 10 years.

Design and procedure

In this retrospective study we used a unidirectional pre–post mirror comparison design to evaluate an equal period before and after participants’ engagement with treatment by the MMHU. Data were retrieved from participants’ medical records and were de-identified before statistical analysis; therefore, informed consent was not required. Diagnoses were based on evaluations by two board-certified psychiatrists using ICD-10 criteria. 24 Involuntary admissions were identified from participants’ electronic health records at PAGNH on the basis of the unanimous decision of two certified psychiatrists. This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2013, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Crete (protocol code 34/9.11.2018, approved 10 December 2018).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise demographic and clinical data: means and standard deviations (s.d.) for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical ones. The study’s first aim was to compare the number of voluntary and involuntary admissions before and after MMHU follow-up, using an equal pre- and post-period for each participant. Admissions were analysed using means, standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals. As data on admissions were not normally distributed, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess changes in admission rates within the same group of participants before and after MMHU follow-up. We further explored potential differences in primary outcomes between two participant subgroups: those followed up by the MMHU after multiple in-patient admissions (subsample A; n = 100) and those followed up after their first in-patient admission (subsample B; n = 55). Demographic and clinical differences across groups were estimated using either the z-test of proportion (categorical data) or the t-test of independence (continuous data), with significance set at P < 0.05. To address the second objective, i.e. determining potential protective sociodemographic and/or clinical characteristics affecting readmission rates, we performed regression analyses on data from 179 participants who had been followed up by the MMHU for at least 1 year and had a minimum of one admission either before or after their first visit. To evaluate the magnitude of the regression effect, we calculated Cohen’s f 2, with values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 representing small, medium and large effects respectively. Reference Cohen25 Clinical change was measured by subtracting post-follow-up admissions from pre-follow-up admissions. Positive values indicated clinical improvement, negative values indicated deterioration and zero values indicating no clinical change. We also explored whether consistent follow-up influenced outcomes. A new variable ‘visit rate to MMHU’ was established by calculating each participant’s average follow-up visits (number of total visits/number of years of attendance). Participants were then categorised into ‘low’ and ‘high’ visit groups based on the total sample’s median value. We hypothesised that patients in the high visit rate group will demostrate greater clinical improvement (e.g. lower involuntary readmissions) than those in the low visit rate group. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28 for Windows.

Results

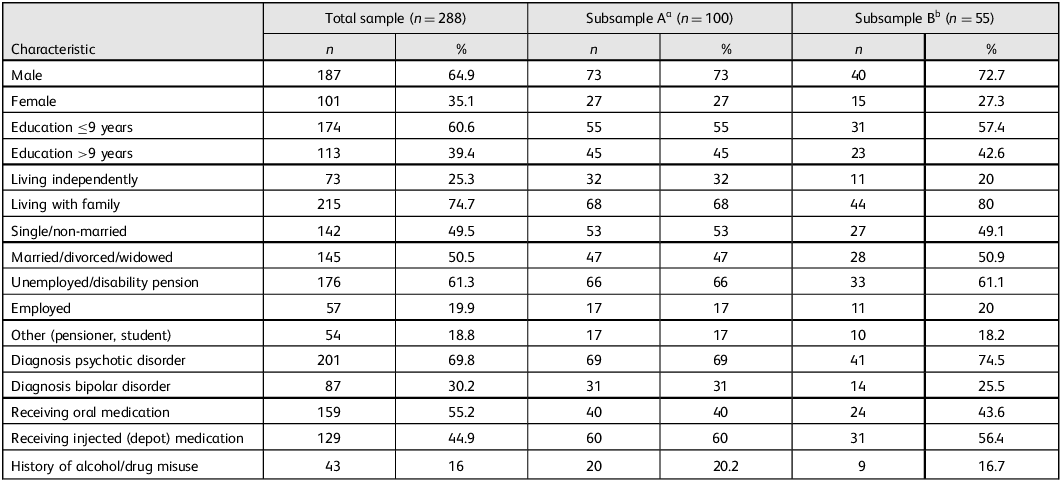

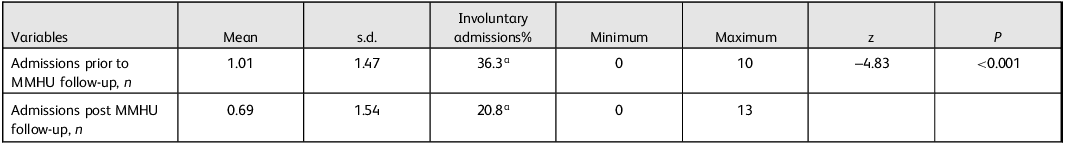

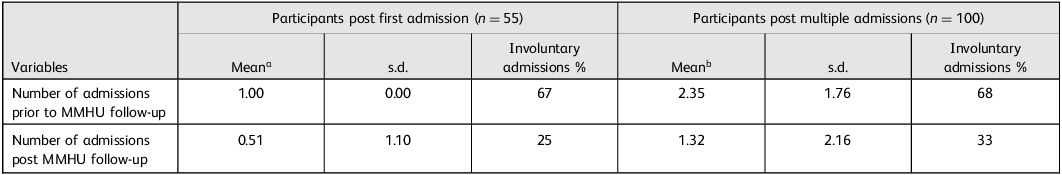

The demographic and clinical characteristics for all participants are summarised in Table 1. Consistent with the study’s primary objective and hypothesis, a statistically significant reduction in the number of admissions (both voluntary and involuntary) was observed following initiation of care by the MMHU (z = −4.83, P < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant decline in involuntary admissions among participants after their MMHU intervention (Table 2). A similar significant reduction in admissions was observed in the subsample of participants (n = 55) who first visited the MMHU after a single admission (z = −4.51, P < 0.001). The mean number of admissions prior to MMHU treatment was 1.00, compared with 0.51 following MMHU treatment. A substantial effect was also evident among participants with a history of multiple admissions (z = −5.18, P < 0.001), with the mean admission rate decreasing from 2.35 pre- to 1.32 post-MMHU follow-up (Table 3). Importantly, the frequency of involuntary admissions also declined significantly. Among patients with a single prior admission, the rate of involuntary admissions decreased from 67 to 25%, whereas for those with multiple prior admissions, the rate reduced from 68 to 33% (both P < 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 1 Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the total sample (n = 288) and of those who were referred to the mobile mental health unit (MMHU) after their first (n = 55) or multiple in-patient admissions (n = 100)

a Subsample A refers to participants who had ≥2 admissions prior to their follow-up by the MMHU.

b Subsample B refers to participants who had ≤1 admission prior to their follow-up by the MMHU.

Table 2 Average number of admissions (voluntary and involuntary) and percentage of involuntary admissions prior to and post first visit to the mobile mental health unit (MMHU) in the total sample (n = 288)

a Differences between involuntary admissions are statistically significant (z = −3.51, P < 0.001).

Table 3 Average number of admissions (voluntary and involuntary) and percentage of involuntary admissions prior to and post mobile mental health unit (MMHU) follow-up in participants with only one admission versus multiple admissions prior to their first MMHU visit

a Statistically significant mean difference: z = −4.51, P < 0.001.

b Statistically significant mean difference: z = −5.18, P < 0.001.

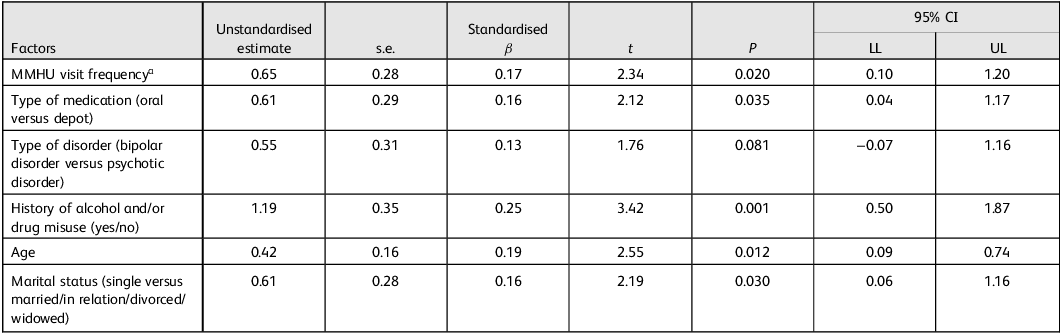

Consistent with the study’s secondary objective, analysis of sociodemographic and clinical factors predicting readmission rates showed that a reduction in readmissions was associated with older age (β = 0.42, t(174) = 2.55, P = 0.012), depot medication (β = 0.61, t(174) = 2.12, P = 0.035), lack of a history of alcohol and/or drug misuse (β = 1.19, t(174) = 3.42, P = 0.001) and being ever married (β = 0.61, t(177) = 2.19, P = 0.030) (Table 4). Moreover, participants with psychosis tended to have lower readmission rates compared with those with bipolar disorder (β = 0.55, t(174) = 1.76, P = 0.081). Frequency of visits to the MMHU was not found to have a significant effect on the outcome. However, after examination of the variable’s distribution, we observed that values in the upper 50th percentile were distributed mainly between 5 and 9 visits per year, with only a few participants making more than 9 visits per year. We therefore identified 5–9 visits per year as the normative frequency of follow-up by the MMHU (assigned a value of 1) and we merged <5 and >9 visits per year into a single category indicative of a non-normative frequency of follow-up by the MMHU (assigned a value of 0). Although we used the percentile-based categorisation to divide our sample into two equal-sized groups (‘frequently followed up’ versus ‘not-frequently followed up’ participants) to ensure statistical comparability and prevent potential estimation bias, this subgroup distribution is exploratory. Repetition of the regression analyses with this modified dichotomous variable revealed that the normative visit frequency to the MMHU was a strong protective factor associated with significant reduction of readmissions (β = 0.65, t(174) = 2.34, P = 0.020) (Table 4). The overall regression model was statistically significant (F(4, 174) = 3.81, P = 0.005), indicating that all tested predictors apart from the diagnosis type reliably contribute to a reduction in participants’ readmission rates. This model explained a small, yet significant proportion of variance (R 2) in participants’ improvement after attending the MMHU, with R 2 = 0.081, corresponding to a small to medium effect size with Cohen’s f 2 = 0.09; thus, approximately 8.1% of the variance in relapse rates can be reliably explained by the combined influence of age, visit frequency and medication status, with a relatively small standard error of estimate (σ est = 1.83).

Table 4 Regression analysis of demographic and clinical factors predicting readmission rates (n = 179)

LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit; MMHU, mobile mental health unit.

a Visit frequency as redefined by the normative (5–9 visits/year) and non-normative (≤4 and ≥10 visits/year) frequency of follow-up by the MMHU.

Finally, an analysis was conducted to examine the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants identified as having a non-normative visit frequency to the MMHU. Of the 179 participants, 74 (41.3%) had 4 or fewer visits per year and only 13 (7.3%) had 10 or more. In both the low- and high-frequency groups, the majority were men (75.7 and 76.9% respectively). Owing to the limited sample size in the high-frequency group, further comparative analysis was restricted to participants classified as having a normative visit frequency (n = 92) and those with low visit frequency (n = 74). Results revealed that participants maintaining a normative pattern of MMHU visits were generally younger and had attained higher levels of education, compared with those with a lower frequency of visits.

Discussion

Readmission rates

The primary finding of our study was a significant reduction in readmissions among patients with psychosis or bipolar disorder following long-term engagement (averaging 5 years) with the MMHU, regardless of whether they had had single or multiple admissions prior to their initial visit. In addition, we found a two- to three-fold decrease in the rate of involuntary admissions compared with pre-MMHU levels. Notably, the most favourable outcomes were observed among patients who maintained a follow-up frequency of 5–9 visits per year. These findings, derived from a relatively large sample in rural southern Greece (Heraklion/Crete), confirm and expand on results from smaller studies in northern Greece. Reference Garbi, Tiniakos, Mikelatou and Drakatos17,Reference Peritogiannis, Gioti, Gogou and Samakouri18 The data support the effectiveness of the MMHU model as a community-based mental health service capable of delivering sustained clinical benefits to individuals with severe mental illness residing in rural and underserved areas, regardless of regional or sociocultural differences as well as variations in unit structure, staffing and accessibility to community health resources. Similar evidence of efficacy has been reported in diverse international settings, including rural Haiti, Reference Fils-Aimé, Grelotti, Thérosmé, Kaiser, Raviola and Alcindor26 the Norwegian fjords Reference Ruud, Aarre, Boeskov, Husevåg, Klepp and Kristiansen13 and rural Virginia. Reference Wanchek, McGarvey, Leon-Verdin and Bonnie9 Furthermore, the observed reduction in hospital readmissions among first-time and chronically admitted patients highlights the capacity of the MMHU’s multidisciplinary team to deliver effective integrated care that mitigates relapse risk, especially since no policy and/or service-level changes had been made since it began operating. Therefore, our outcomes provide empirical support for the implementation of structured, frequent follow-up programmes for individuals with psychotic or bipolar disorders, particularly in rural or resource-limited settings.

Involuntary admission rates

A significant and marked reduction was also observed in the number of involuntary admissions. Reduction of involuntary admissions is of crucial importance for Greece, given the high rates of such admissions in the country. Reference Drakonakis, Stylianidis, Peppou, Douzenis, Nikolaidi and Rzavara27,Reference Stylianidis, Georgaca, Peppou, Arvaniti and Samakouri28 A substantial body of research has documented the adverse emotional impact of involuntary admissions on patients, including experiences of anger, fear, hopelessness, despair, loss of dignity and overall dissatisfaction with care. Reference Katsakou, Rose, Amos, Bowers, McCabe and Oliver29–Reference Iudici, Girolimetto, Bacioccola, Faccio and Turchi33 De Jong and colleagues Reference de Jong, Kamperman, Oorschot, Priebe, Bramer and van de Sande34 found that integrated treatment may reduce the likelihood of involuntary admissions by up to 29%, and Wormdahl and colleagues Reference Wormdahl, Hatling, Husum, Kjus, Rugkåsa and Brodersen35 emphasised the importance of involving primary care services in efforts to prevent such admissions, rather than relying solely on secondary mental healthcare. In this context, our findings suggest that a community-based service, closely connected with primary healthcare and community services, is effective in reducing involuntary admissions among patients in rural and remote areas of Greece. These results align with previous studies demonstrating similar benefits from community mental health centres and MMHUs operating in urban or rural north-west Greece Reference Peritogiannis, Gioti, Gogou and Samakouri18,Reference Peritogiannis, Manthopoulou, Gogou and Mavreas36 and worldwide. Reference Wanchek, McGarvey, Leon-Verdin and Bonnie9,Reference Cervello, Pulcini, Massoubre, Trombert-Paviot and Fakra10,Reference Ruud, Aarre, Boeskov, Husevåg, Klepp and Kristiansen13,Reference Fils-Aimé, Grelotti, Thérosmé, Kaiser, Raviola and Alcindor26

Outcome predictors

Further, we examined sociodemographic and clinical factors potentially associated with psychiatric readmissions. Our analysis revealed that a reduction in readmissions was associated with older age, no history of alcohol and/or substance misuse, receipt of depot medication and having current or past interpersonal relationships (Table 4). These findings are consistent with previous literature, which has identified older age, absence of substance/alcohol misuse and being ever married as protective factors for hospital readmissions. Reference Suokas, Lindgren, Gissler, Liukko, Schildt and Salokangas6,Reference Donisi, Tedeschi, Wahlbeck, Haaramo and Amaddeo37,Reference Álvarez, Palau, Russo and Nieto38 Although the association between diagnosis type (psychotic disorder versus bipolar disorder) and readmission rate did not reach statistical significance in our sample, diagnosis type remains a clinically relevant variable warranting further investigation. Some evidence suggests that individuals with bipolar disorder may have a lower adherence to treatment compared with those with psychotic disorder, potentially contributing to higher readmission rates. However, the current literature remains inconclusive on this matter and further research with larger and/or targeted samples is warranted. Reference Donisi, Tedeschi, Wahlbeck, Haaramo and Amaddeo37 Notably, the use of depot medication emerged as a particularly strong protective factor, consistent with a growing body of evidence supporting the association between long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics and reduced risk of psychiatric readmission. Reference Álvarez, Palau, Russo and Nieto38–Reference Besana, Civardi, Mazzoni, Miacca, Arienti and Rocchetti43 A recent study further demonstrated that initiating LAIs early, particularly in young adults experiencing a first episode of psychosis, significantly lowered the likelihood of future readmission. Reference Besana, Civardi, Mazzoni, Miacca, Arienti and Rocchetti43

An additional key finding is that maintaining a normative visit frequency, defined as 5–9 visits per year with an MMHU psychiatrist, serves as a strong protective factor against hospital readmissions in people with psychotic or bipolar disorder. Previous research has consistently highlighted the association between timely post-discharge follow-up and reduced risk of readmission in these populations. Reference Suokas, Lindgren, Gissler, Liukko, Schildt and Salokangas6,Reference Marcus, Chuang, Ng-Mak and Olfson8,Reference Nelson, Maruish and Axler44–Reference Kurdyak, Vigod, Newman, Giannakeas, Mulsant and Stukel47 In particular, many studies emphasised the role of immediate follow-up, typically within 30 days of discharge, in preventing relapse and readmission. To our knowledge, our study is among the first to suggest that a specific frequency of follow-up – approximately one visit every 1.5 to 2 months – may be optimal in reducing the likelihood of readmission. This finding carries important clinical and operational implications, suggesting that a structured, moderate-frequency follow-up schedule may not only support patient stability, but also optimise the allocation of limited mental health resources, especially in rural areas where access to psychiatrists is often constrained. The MMHU model, which collaborates closely with families and local community services such as primary healthcare centres, appears to play a pivotal role in sustaining engagement and continuity of care, thereby mitigating relapse risk. Nevertheless, although the association between visit frequency and reduced readmission is statistically significant, the effect size observed in the regression model is modest. Thus, the clinical utility of this finding should be interpreted with caution and further research is warranted to validate these results in larger and more diverse populations.

In contrast, both low and high frequency of visits per year were associated with increased rates of readmission. Reduced visit frequency may be indicative of suboptimal engagement with services, potentially driven by factors such as poor treatment adherence, limited social support, lower educational attainment and persistent stigma – particularly prevalent in small or rural communities. These barriers may hinder regular contact with mental health services and contribute to relapse or crisis requiring hospital admission. Conversely, a high frequency of visits – defined as 10 or more per year – may be indicative of a more severe or treatment-resistant illness trajectory. This pattern may also signal greater complexity in clinical presentation, warranting structured treatments such as those offered in community-based day care programmes. Supporting this interpretation, unpublished data from our pilot day care centre in the rural town of Moires (population ∼6000 residents in southern Heraklion) suggest that individuals with higher clinical needs benefit from frequent, multidisciplinary engagement beyond standard out-patient care.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths, including the large sample of patients with psychosis or bipolar I disorder drawn from a well-defined catchment area in Heraklion, Crete, a region characterised by distinct geographical and sociocultural characteristics, with a population exceeding 120 000 residents, served by a single hospital and a single MMHU. Reference Kalseth, Lassemo, Wahlbeck, Haaramo and Magnussen48 This MMHU implements standardised diagnostic, therapeutic and legal procedures, thereby minimising variability due to regional service differences. Our findings also highlight key sociodemographic and clinical factors, including the optimum number of annual visits associated with reduction in both voluntary and involuntary readmissions. These results are consistent with a previous study of community-based mental health services in urban Greek settings, Reference Madianos and Economou49 which also reported reduction in involuntary admissions, decrease total in-patient days and improved monitoring of individuals with chronic mental illness, and with a report by the Council of Europe on good practices. Reference Peritogiannis, Samakouri and Vgontzas50 As the largest longitudinal cohort study of a rural/island mental health population in Greece, with an average follow-up of approximately 5 years, this study provides important insights for both clinical practice and public health policies, especially in regions with scarce mental health resources.

Our research is not without limitations. First, the analysis was restricted to data extracted from patients’ medical records, which, although reliable for clinical information, may be insufficient to capture other significant variables associated with an increased risk of readmission, such as the length of hospital stay or the quality and accessibility of services within mental health units. Reference Kalseth, Lassemo, Wahlbeck, Haaramo and Magnussen48 Although the study’s pre–post mirror design entails certain methodological limitations, such as absence of a control group, potential expectancy effects and the possibility of unmeasured confounding variables (e.g. socioeconomic factors such as the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic), the findings nonetheless provide meaningful insights into the community mobile mental health service. Another methodological limitation involves the use of percentile-based categorisation to evenly divide the sample into two groups for visit frequency. Although this method reduces selection bias, it may not accurately reflect the natural distribution within the clinical population and it may constrain the generalisability of findings related to visit frequency. Moreover, the absence of a control or comparison group – such as patients from urban settings or those differing in race, ethnicity or cultural background Reference Madianos and Economou49 – may restrict the interpretability and external validity of the results. Finally, owing to the relatively small number of high-frequency attendees, we were unable to perform comparative analyses across low-, normative- and high-frequency attending groups in terms of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Future studies with more diverse and larger samples would be valuable to contextualise and extend these findings.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate readmission rates in a large cohort of individuals with psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder within a well-defined catchment area in Crete, served by a uniform public mental health service network. In accordance with our research objective, a significant reduction in both total and involuntary readmissions was observed after MMHU follow-up, independent of patients’ prior admission history. Reduced readmission rates were associated with older age, absence of substance misuse, treatment with depot medication and having formed intimate interpersonal relationships currently or in the past. Noticeably, a normative visit frequency (defined as 5–9 visits per year) was associated with the lowest readmission rates, highlighting its relevance for both clinical and public mental health planning. Future research should investigate the underlying factors contributing to persistent readmission risk among patients with high-frequency service use, despite their regular engagement with psychiatric care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2025.10084

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study, along with the analyses, are openly available as supplementary material to the article.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the attending and in-training psychiatrists of the Department of Psychiatry at the University Hospital in Heraklion who rotated through the Mobile Mental Health Unit for their valuable assistance in data collection.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Region of Crete, grant number 152721/5-7-2018.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.