Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli are the most common carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), associated with the highest number of infections. Usually, they are normal inhabitants of the gut microbiota but can also be opportunistic pathogens that cause urinary tract infections, pneumonia, meningitis, surgical wound infections, and liver infections. Nosocomial, often deadly infections, include blood stream infections that can develop into sepsis [Reference Vading1].

CRE with resistance to last resort carbapenems are regarded as critical global health threats due to their pandemic spread and increasing mortality rates [Reference Navon-Venezia, Kondratyeva and Carattoli2]. The aim of this study was to evaluate the sudden emergence of CRE that occurred in wastewater outlet samples collected in Kristianstad, Southern Sweden.

In spring (March) and summer (August) 2024, phenotypically CRE isolates were detected in samples from outlet water from the Kristianstad wastewater treatment plant (WWTP), which warranted a more intense sampling over 2 weeks in September–October 2024. The plant had the capacity to treat wastewater from 210,000 persons daily, wastewater from the city hospital and a large pig slaughterhouse during the studied period. Cleaning procedures included mechanical, biological and chemical processes. The treated effluent was thereafter pumped into the recipient lake Hammarsjön, which is an extended part of the river Helge Å (figure in Supplementary Materials). The samples were collected where the effluent from the plant is pumped out into the lake. Three litres of surface water were collected into 1 L sterilized glass bottles and transported back to the laboratory for further analyses within 2 h. Volumes of 300 ml x 3 from every flask were filtered through sterile 47 mm 0,2 μm filters (Supor® 200, Pall Corporation, Michigan, USA) using a filtering devise equipped with a vacuum pump. The filters where thereafter placed onto KPC ChromAgar™ (Paris, France) plates and incubated for 18–24 h at 37 °C. In total 55 CRE isolates were obtained from these samples subsequently identified as E. coli (n = 29) and K. pneumoniae (n = 26) by Microflex Biotyper MALDI-ToF MS (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) using the 1,829,023 Maldi Biotyper Compass Library. Total counts of bacteria were not performed. PCR analyses were achieved with primers and amplification protocols as described by Mentasti et al. (2019) using SYBRGreen and melt curve analyses [Reference Mentasti3]. The analyses indicated bla NDM genes in 94% (52/55) and bla OXA-48-like genes in 56% (31/55) of the isolates (data not shown). Phenotypical antibiotic resistance to meropenem were detected by the standard disc diffusion method according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, https://www.eucast.org/bacteria/methodology-and-instructions/disk-diffusion-and-quality-control/).

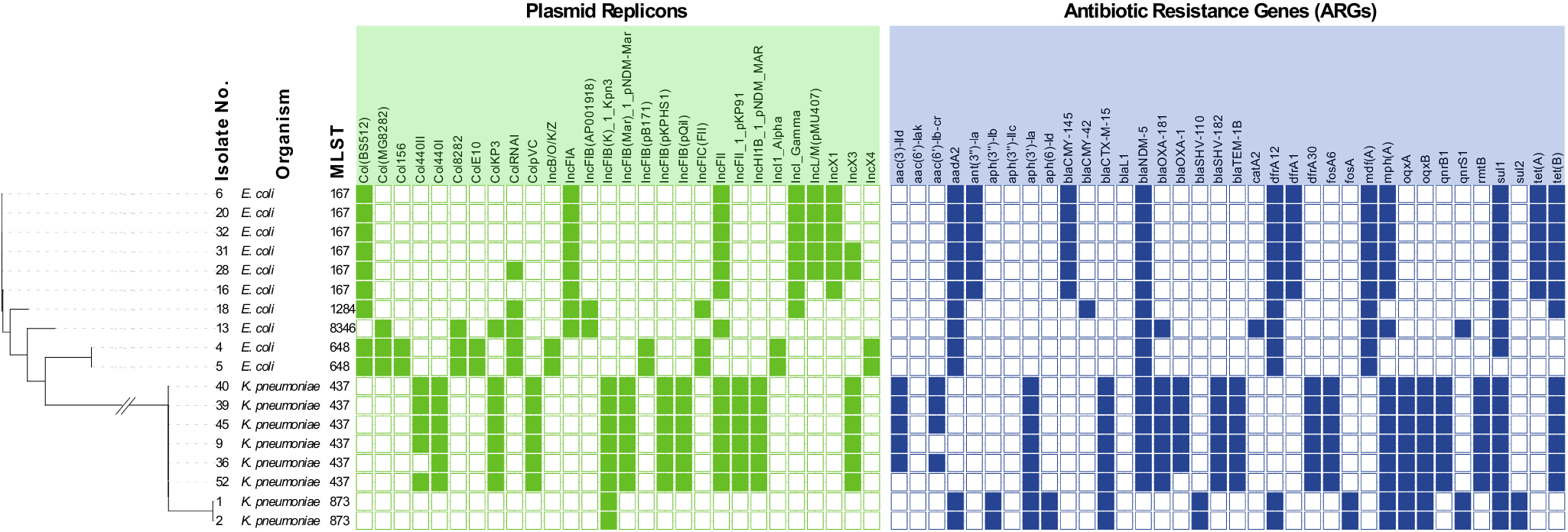

To further characterize the isolates, 18 representative isolates, ten E. coli and eight K. pneumoniae, were whole genome sequenced. The selection of the isolates was based on different dates of isolation and species. DNA was prepared using DNAeasy Blood and Tissue kit from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) and sequenced at Eurofins Genomics (Constance, Germany) using INVIEW Resequencing of Bacteria on Illumina NovaSeq X+, PE150 mode. The isolates were analysed for multi-locus sequencing type, plasmid type, virulence genes, and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [Reference Rudbeck4]. The phylogenetic tree in Figure 1 shows how the two species group separately, with each species comprising different sequence types (STs) that exhibited conserved plasmid profiles, and where all isolates were multi-drug-resistant (MDR). MDR is defined here as presence of ARGs providing resistance to ≥3 antibiotic classes.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of all isolates, showing isolate number, species, multi locus sequencing types (MLST), plasmid replicons (Inc groups), and presence of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). The sequencing results were analysed using BACTpipe, a pipeline for WGS bacterial genomes [Reference Navon-Venezia, Kondratyeva and Carattoli3]. In the pipeline, fastp is used for pre-processing of paired ends, followed by Kraken2 for taxonomic identification and shovill for de novo assembly. Lastly, genome annotation is completed using prokka and statistics about the assembly and annotation are reported by MultiQC. MLST was determined using the achtman scheme (mlst v. 2.23.0), plasmid types were determined using ABRicate PlasmidFinder (2014), virulence genes were identified using ABRicate VFDB (2016) and ARGs were identified using ABRicate ResFinder (v. 4.0, 2020). Phylogenetic analyses were carried out using Mashtree (2022) where the final phylogenetic tree annotations were produced using iTOL (v. 7.0, https://itol.embl.de/). Sequence data are available under GenBank accession numbers JBRMLF000000000 to JBRMLW000000000.

The E. coli isolates belonged to ST167 (n = 6), ST648 (n = 2), ST1284 (n = 1), and ST8346 (n = 1). The K. pneumoniae isolates belonged to ST437 (n = 6) and ST873 (n = 2). Analysis with ResFinder (https://genepi.food.dtu.dk/resfinder) revealed NDM-5 metallo-β-lactamase genes in all E. coli and in the K. pneumoniae ST437 isolates. The isolates that contained both bla NDM-5 and bla OXA-181 belonged to K. pneumoniae ST437 and E. coli ST8346 (see supplementary material). E. coli ST167 and ST1284 were PCR positive for bla OXA-48 but no corresponding genes were detected by ResFinder.

Virulence genes were detected in all isolates. K. pneumoniae are divided into classic (cKp) and hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp), where the latter is characterized by a hypermucoid phenotype and presence of iron acquisition siderophores, including yersiniabactin, salmochelin, aerobactin, and enterobactin [Reference Lai, Lu and Hsueh5]. The yersiniabactin operon encoded by the ybtAEPQSTUX operon, irp1 and irp2, and siderophore receptor fyuA were found in all ST437. Presence of the aerobactin receptor gene (iutA) and aerobactin synthesis operon (iucABCD) is considered a hallmark of hvKp, enabling growth in iron-poor host environments. However, the K. pneumoniae detected in this study lacked both the rmpA/rmpA2 locus conferring a hypermucoviscous phenotype and the full aerobactin and salmochelin loci and are thus not hvKp.

The two K. pneumoniae isolates from March belonged to ST873, a type previously known to carry bla NDM-1. Interestingly, these isolates were tested intermediate and resistant to meropenem, respectively, by the disc diffusion method, but harboured only the extended-spectrum β-lactamases bla SHV-110 and bla CTX-M-15. Therefore, the underlying mechanism of carbapenem resistance in the ST873 isolates requires further investigation.

E. coli ST167 and ST1284 both belong to globally dominant CRE E. coli types. In this study, ST1284 harboured the aerobactin operon, whereas ST167 was negative for this operon but contained the yersiniabactin operon. This study also detected ST8346, an emerging multi-resistant CRE type with recently reported co-carriage of bla NDM-5 and bla OXA-181 on IncF and IncX plasmids, respectively [Reference Chen6]. Finally, ST648 is also an emerging CRE clone. Thus, all the E. coli types identified in the WWTP outlet water are well established pathogens implicated in urinary tract infections, bloodstream infections, sepsis, and wound infections [Reference Chen6].

The development of MDR in K. pneumoniae and E. coli may result in treatment failures and is a global health problem. Particularly, the recent emergence of high carbapenemase resistance is a cause of concern [Reference Vading1]. In Sweden, mandatory laboratory reporting of CRE has been practiced since 2007. Reports from 2024 show an incidence of CRE infections of 3.9 cases per 100,000 inhabitants [7]. The most frequent sequence types reported were K. pneumoniae ST147, ST307, and ST395, and for E. coli ST167, ST69, and ST648, while bla OXA-48 followed by bla NDM were the most common carbapenemases. In this study, we determined that several isolates recovered over a 2-week period were K. pneumoniae ST437. This type belongs to the clonal complex CC11 and is considered an emerging clone with epidemic potential. Additionally, it is frequently found in nosocomial infections in humans, as well as in environmental sources such as rivers and wastewater in many parts of the world [Reference Sahoo8]. NDM-5-positive E. coli has increased during the last years in Europe, and E. coli ST167 is predominant [9].

Several K. pneumoniae and E. coli STs associated with carbapenemases and/or ESBL carriage, seem to accumulate in wastewater and sewage and are often recovered from inlets to WWTPs [Reference Karkman10]. Hence, WWTP inlets can provide a reflection on the carrier status of larger populations in communities [Reference Al-Mustapha11], while detection of multidrug-resistant and virulent bacteria in treated effluent from WWTPs, as in the case of the isolates analysed in this study, indicates a high contribution from incoming water with increasing risk of resistance transmission [Reference Mollenkopf12].

The temporarily detection of K. pneumoniae ST437 and E. coli ST167 in the treated effluent from the WWTP in Kristianstad community was preceded by over 10 years (2014–2024) of surveillance sampling, where CRE was never isolated. The presence of bla NDM-5 in the Swedish environment is thus of great concern and suggests that highly virulent and multidrug-resistant clones may be more common in Sweden than previously known.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268826101071.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) reference numbers JBRMLF000000000 to JBRMLW000000000.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kaisa Thorell for support with computational analyses, and ÅS thanks the EU and Swedish Research Council for funding in the frame of the collaborative international consortium PARRTAE financed under the This ERA-NET is an integral part of the activities developed by the Water, Oceans and AMR Joint Programming activities. Biomedical science students at Kristianstad University kindly helped with the initial laboratory analysis.

Author contribution

Data curation:; Formal analysis:; Funding acquisition:; Conceptualization:

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Kristianstad University, Faculty of Natural Science, which contributed to the analyses (CA & ASRH) and the ERA-NET Aquapollutants Joint Transnational Call GA na869178 (ÅS).

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standard

No ethical approval was required since the study only involved monitoring of environmental bacteria and not human or animal subjects.