Clinical Implications

▪ Cariprazine was generally safe and well tolerated in patients with schizophrenia when flexibly dosed at 3–9 mg/d for up to 48 weeks of treatment.

▪ The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were akathisia, headache, insomnia, and weight gain. Most were mild or moderate in intensity and rarely resulted in discontinuation.

▪ Mean changes in metabolic, cardiovascular, and laboratory parameters were generally small and not clinically significant. Prolactin levels decreased over the course of 48 weeks of treatment.

▪ There were no unexpected safety issues or deaths in patients exposed to long-term cariprazine treatment in this study.

▪ This study provides further evidence supporting the safety and tolerability of cariprazine for the long-term treatment of schizophrenia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe and chronic psychiatric disorder associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and functional impairment. Compared with the general population, patients with schizophrenia are at greater risk for medical comorbidities,Reference Dixon, Postrado, Delahanty, Fischer and Lehman 1 , Reference Weber, Cowan, Millikan and Niebuhr 2 including metabolic syndromeReference De Hert, van Winkel and Van Eyck 3 and cardiovascular disease.Reference Laursen, Munk-Olsen and Vestergaard 4 Antipsychotics are generally effective for treating the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, although due to the heterogeneous nature of the disease, many individual patients have a preferential response to certain compounds. With regard to tolerability, antipsychotics have different likelihoods of being associated with troublesome adverse effects, including weight gain, dyslipidemia, hyperprolactinemia, sedation, QT prolongation, and extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).Reference Leucht, Pitschel-Walz, Abraham and Kissling 5 , Reference Weiden 6 According to findings from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE), 74% of patients discontinued the study medication before 18 months had elapsed,Reference Lieberman, Stroup and McEvoy 7 suggesting that available antipsychotics are associated with substantial limitations. Since schizophrenia is a lifelong disease that requires continuous pharmacological treatment for most patients, establishing the long-term safety and tolerability of new compounds is essential for identifying treatments that are amenable to maintenance therapy.

Cariprazine, a dopamine D3 and D2 receptor partial agonist, is approved for the treatment of schizophrenia, as well as for manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder. Cariprazine has also shown efficacy versus placebo as a monotherapy in patients with bipolar depressionReference Durgam, Earley and Lipschitz 8 and as adjunctive therapy in patients with major depressive disorderReference Durgam, Earley and Guo 9 ; additionally, efficacy has been demonstrated for cariprazine versus risperidone in a randomized clinical trial of patients with predominantly negative symptoms of schizophrenia.Reference Németh, Laszlovszky and Czobor 10 Unlike other available atypical antipsychotics, cariprazine has a greater affinity for D3 than D2 receptors in vitro,Reference Kiss, Horváth and Némethy 11 and it exhibits high occupancy of both D3 and D2 receptors in vivo in ratsReference Kiss, Horti and Bobok 12 and humans.Reference Slifstein, Abi-Dargham and D’Souza 13 In addition to potent partial agonist activity at D3 and D2 receptors, cariprazine also acts as an antagonist at the serotonin 5-HT2B receptors, a partial agonist at 5-HT1A receptors, and shows lower or negligible affinity at other receptors, including noradrenergic, histaminergic, and cholinergic receptors.Reference Kiss, Horváth and Némethy 11 , Reference Seneca, Finnema and Laszlovszky 14

Cariprazine was effective and generally well tolerated in three 6-week randomized, placebo- and/or active-controlled phase II (cariprazine 1.5, 3.0, or 4.5 mg/dReference Durgam, Starace and Li 15 ) and phase III (cariprazine 3 or 6 mg/dReference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 ; 3–6 and 6–9 mg/dReference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 ) studies conducted in adult patients with schizophrenia. In these studies, cariprazine was not associated with clinically meaningful changes in metabolic parameters, prolactin increase, prolongation of QT interval, or substantial increases in body weight; however, the incidence of akathisia and EPS was higher with cariprazine than with placebo. In a 48-week, open-label extension study (NCT00839852), treatment with low-dose cariprazine (1.5–4.5 mg/d) was generally well tolerated and did not result in any new safety concerns.Reference Durgam, Greenberg and Li 18 In the open-label study presented in the our current report (NCT01104792), evidence related to the long-term safety and tolerability of cariprazine was extended by evaluating higher doses (3–9 mg/d) in adult patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

This multinational, open-label, flexible-dose, long-term study was conducted between May of 2010 and January of 2013 at 86 study centers in United States, Colombia, India, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine; 13 U.S. study centers and 10 non-U.S. study centers received investigational product but did not enroll any patients. At each study center, the principal investigator was responsible for ensuring that the study was conducted in compliance with the study protocol and the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. The study protocol was approved by an institutional review board (U.S. sites) or an ethics committee (non-U.S. sites) and followed the European Union Clinical Trial Directive (Directive 2001/20/EC) where applicable. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH–E6) GCP guidelines. All participants provided written informed consent. At most study centers, patients were compensated for their participation.

Study design

Eligible patients included both new patients and patients who had completed double-blind treatment in one of two lead-in studies: RGH-MD-04 (NCT01104766)Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 or RGH-MD-05 (NCT01104779).Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 RGH-MD-04 was a 6-week, double-blind, fixed-dose study in which patients were randomized to cariprazine 3 or 6 mg/d, placebo, or aripiprazole 10 mg/d. RGH-MD-05 was a 6-week, double-blind, fixed/flexible-dose study in which patients were randomized to cariprazine 3–6 mg/d, cariprazine 6–9 mg/d, or placebo. Study centers were dedicated to enrolling either new patients or patients who had completed one of the lead-in studies. This 53-week study comprised a no-drug screening period of up to 7 days for all patients regardless of whether they were continuing from a lead-in study or were new patients, and a 48-week open-label treatment period with flexibly dosed cariprazine 3–9 mg/d. Patients who completed open-label treatment or who prematurely discontinued were monitored as outpatients for 4 additional weeks during the safety follow-up period, and they received treatment as usual at the investigator’s discretion but no additional study drug.

For patients who had completed a lead-in study, the final double-blind treatment visit was considered the start of the open-label screening period. Patients were hospitalized at the end of a lead-in study, and all newly entering patients were hospitalized during open-label screening. All patients, including those who completed a lead-in study as outpatients, were hospitalized during the first week of open-label treatment, after which they could be discharged and followed up as outpatients if their dosage was stabilized for at least 3 days and they did not require a dosage adjustment at discharge. Patients were allowed to remain hospitalized for up to 2 weeks at the discretion of the investigator.

The initial dose of cariprazine was 1.5 mg/d, which could be increased in 1.5-mg increments to 3.0 mg/d on day 2 and to a maximum of 4.5 mg/d on day 3 or 4. Patients were required to receive doses of 3.0 or 6.0 mg/d on days 5–7, which could be increased to 9.0 mg/d subsequently. Dose increases were allowed in cases of inadequate response if there were no tolerability issues, and dose decreases to the previous available level were permitted at any time if the investigator determined that there were significant tolerability issues. Visits occurred weekly for the first 6 weeks and biweekly until the end of the study.

Inclusion criteria

Consistent with eligibility criteria for the lead-in studies,Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 , Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 the current study included men and women aged 18 to 60 years. Patients entering from the lead-in studies and newly entering patients were required to have met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Text Revision (DSM–IV–TR), 19 criteria for schizophrenia (paranoid type, disorganized type, catatonic type, or undifferentiated type) for at least 1 year, as determined using the modified Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM–IV (SCID). Continuing patients needed to have completed the double-blind treatment period in one of the lead-in studies. All patients were required to have a score ≤25 on the positive subscale of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),Reference Kay, Opler, Spitzer, Williams, Fiszbein and Gorelick 20 , Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler 21 and a Clinical Global Impressions–Severity (CGI–S)Reference Guy 22 score ≤3. Patients were required to have normal physical examination findings, vital signs, clinical laboratory test results, and electrocardiogram (ECG) results or abnormal results that were not considered clinically significant. Patients were also required to have a designated caregiver who accompanied the patient at each visit. If the caregiver could not attend, written documentation of study medication compliance had to be provided.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the study for DSM–IV–TR diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, or other psychotic disorders, except for schizophrenia. Suicide risk, defined as a suicide attempt in the previous two years, significant risk as judged by the investigator, or information collected from the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C–SSRS)Reference Posner, Brown and Stanley 23 was exclusionary. Patients with substance abuse/dependence (other than nicotine or caffeine) within the past three months were excluded, as were patients with positive urine drug screens. Additionally, urine drug screens were routinely conducted throughout the study to monitor drug use. Patients with positive results were discontinued due to protocol violation or allowed to continue based on investigator judgment. If a second positive urine drug screen was collected, the patient was discontinued from the study. Additional reasons for exclusion included a body mass index (BMI) <18 or >40 kg/m2; pregnancy or breastfeeding; electroconvulsive therapy in the past 3 months; prior depot neuroleptic treatment or clozapine within the past 10 years (except low-dose episodic use for insomnia); a first episode of psychosis; or treatment-resistant schizophrenia during the last 2 years, defined as little or no symptomatic response to at least two antipsychotic trials of a least 6 weeks in duration at a therapeutic dose.

Medications with psychotropic activity were not allowed except for the short-term use of lorazepam (for agitation, irritability, hostility, restlessness; max= 2–6 mg/d); zolpidem (max=12.5 mg/d), zaleplon (max =20 mg/d), chloral hydrate (max=2000 mg/d), or eszopiclone (max=3 mg/d) (for insomnia); and diphenhydramine (50 mg/d), benztropine (2–4 mg/d), or propranolol (doses based on cardiovascular measures) (for EPS or akathisia). No such medications were permitted within 8 hours of psychiatric or neurological assessments. Patients with EPS who were not adequately controlled by medication at baseline or patients with clinically significant uncontrolled adverse events (AEs) from the lead-in studies were excluded.

Outcome assessments

The primary objective of our study was an evaluation of the long-term safety and tolerability of cariprazine. Safety assessments included AE reports, vital signs, clinical laboratory tests, ECGs, physical examinations, ophthalmologic examinations, the C–SSRS, and EPS scales (Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale [AIMS],Reference Guy 24 Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale [BARS],Reference Barnes 25 Simpson–Angus Scale [SAS]Reference Simpson and Angus 26 ). Efficacy assessments were collected but not categorized as primary, secondary, or additional categories. These assessments included the PANSS, the CGI–S, the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale, Revision 4 (SQLS–R4), the Cognitive Drug Research (CDR) Attention Battery, and the Color Trails Test (CTT).

Statistical analyses

Safety parameters were summarized with descriptive statistics based on the safety population, which consisted of all participants who received at least one dose of open-label cariprazine. For mean changes in safety parameters, the baseline value from the lead-in study was employed for patients entering the open-label study from a lead-in study, and the last evaluation before the first dose of open-label cariprazine was used as the baseline for new patients. Mean changes in safety parameters were based on end-of-study values, which were defined as the last available postbaseline assessment during the open-label treatment period.

For patients who completed one of the lead-in studies, an AE that began during open-label treatment was considered a treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) if it was not present before the first dose of double-blind study drug in the lead-in study or if it increased in intensity following the first dose of open-label cariprazine. For new patients, an AE that began during the open-label treatment period was defined as a TEAE if it was not present before the first dose of open-label cariprazine or if it was present but increased in intensity following the first dose of open-label cariprazine.

Efficacy analyses were based on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which consisted of all patients in the safety population who had at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment. Missing data were imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) approach. Efficacy analyses were performed using descriptive statistics, and no inferential statistics were performed.

Dosing compliance for a specified period was defined as the total number of capsules taken by a patient during that period divided by the number of capsules that were prescribed to be taken during the same period multiplied by 100. Descriptive statistics were utilized to summarize study drug compliance for the safety population during the open-label treatment period.

Results

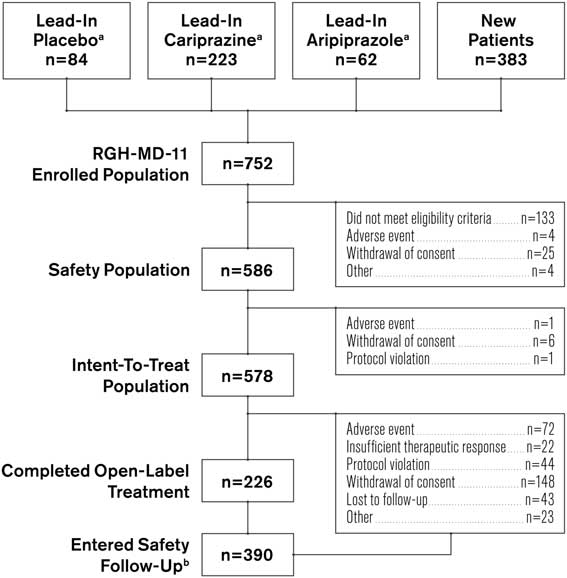

Of the 752 patients who enrolled in the study (Figure 1), 369 completed a lead-in study and 383 were new patients. A total of 18 patients from the lead-in studies and 148 new patients discontinued before the start of open-label treatment (primarily for failure to meet eligibility criteria). Of the 586 remaining participants in the safety population, 235 were new patients and 351 patients had completed a lead-in study (lead-in treatment: cariprazine, 210; aripiprazole, 61; placebo, 80). Approximately 39% of participants completed the study; the most frequent reasons for discontinuation were withdrawal of consent (26.3%) and AEs (12.5%). Follow-up contact with the study centers was conducted to ensure that withdrawal of consent was not due to unreported AEs or other specific underlying reason. Participants who continued from a lead-in study had higher completion rates than newly enrolled patients (46.7 vs. 26.4%, respectively).

Figure 1 Patient populations and disposition. a Patients who received indicated treatment in lead-in study RGH-MD-04 or RGH-MD-05. b Includes both patients who completed the study and patients who prematurely discontinued from the study.

The mean treatment duration was 183.2 days, total exposure to cariprazine was 293.8 patient-years, and the mean cariprazine dose was 5.7 mg/d. The most frequent modal daily dose was cariprazine 6 mg/d (50.9%), followed by 9 mg/d (25.3%), 3 mg/d (22.9%), and 1.5 mg/d (1% [e.g., patients discontinuing during the first week]). Overall treatment compliance ranged from 80 to 110%, with a mean treatment compliance of 99.5%. How treatment compliance affected study outcomes was not investigated.

The demographic and baseline characteristics of the safety population are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients in the study were men; the mean age of participants was 39 years, and the mean duration of schizophrenia was in excess of 12 years. The mean extension baseline PANSS total and CGI–S scores were 66.5 and 3.0, respectively, indicating a mildly ill population at the start of the study (Table 1).

Table 1 Demographics and baseline characteristics (safety population)

a Race and ethnicity were not collected for 15 patients at Romanian study centers per local regulations.

b Based on 584 patients.

c Baseline efficacy variables were based on patients with both baseline and postbaseline efficacy assessments (PANSS, n=572; CGI–S, n=578; SQLS–R4, n=527); baseline was defined as the latest assessment before the first dose of open-label cariprazine.

BMI=body mass index; CGI–S=Clinical Global Impressions–Severity; PANSS=Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SD=standard deviation; SQLS–R4=Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale, Revision 4.

Safety and tolerability

Adverse events

A summary of TEAEs during the 48-week open-label period is presented in Table 2. TEAEs were reported in 81.2% of participants, most of which (>95%) were considered by the investigator to be mild or moderate in intensity, and more than half (53.5%) were considered related to cariprazine. The most frequent TEAEs were akathisia, headache, insomnia, and weight gain. The incidences of somnolence (3.2%) and sedation (2.7%) were low.

Table 2 Summary of adverse events

During the screening period, 1 patient died, 3 patients had SAEs (including the patient who died), and 4 patients discontinued the study due to AEs (including the 3 who had SAEs).

A newly emergent AE occurred during the safety follow-up period and was either not present before the start of the safety follow-up period or increased in severity.

NEAE=newly emergent adverse event; TEAE=treatment-emergent adverse event.

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported in 59 (10.1%) patients during open-label treatment and in 7 patients during the safety follow-up period. No deaths occurred in the safety population, but during the screening period before study drug was received, one death was reported in a 45-year-old male patient with a history of hypertension. This patient was newly enrolled (i.e., not continuing from a lead-in study) and had never received the study drug. The cause of death was cardiac hypertrophy of undetermined etiology. The SAEs reported in ≥1% of patients were worsening of schizophrenia (4.3%), worsening of psychotic disorder (2.0%), and social stay hospitalization (1.0%). In total, 73 (12.5%) patients in the safety population discontinued due to AEs. The only AEs leading to discontinuation in ≥1% of participants were worsening of schizophrenia (2.7%) and psychotic disorder (2.0%). The most frequently reported TEAEs occurred during the first 6 weeks of treatment, and no unanticipated AEs were reported during long-term cariprazine therapy (Table 3).

Table 3 Most frequent adverse events (≥5%) by time to first occurrences (safety population)

N1=number of patients in the safety population who had a treatment duration greater than or equal to the start of the time interval.

Clinical laboratory and safety parameters

The changes in clinical laboratory and other safety parameters are presented in Table 4. Cholesterol (total, HDL, and LDL) and triglyceride levels decreased from baseline to the end of open-label treatment. An increase of almost 5 mg/dL in glucose was observed at the end of open-label treatment. For total cholesterol, shifts from normal/borderline baseline values (<240 mg/dL) to high values (≥240 mg/dL) at the end of open-label treatment were observed in 24 of 486 (4.9%) patients; for LDL cholesterol, shifts from normal/borderline (<160 mg/dL) to high (≥160 mg/dL) values were observed in 16 of 504 (3.2%) patients; for HDL cholesterol, shifts from normal (≥40 mg/dL) to low values (<40 mg/dL) were observed in 52 of 418 (12.4%) patients; for triglycerides, shifts from normal/borderline (<200 mg/dL) to high (≥200 mg/dL) values were observed in 36 of 460 (7.8%) patients; and for fasting glucose, shifts from normal/impaired (<126 mg/dL) to high (≥126 mg/dL) were observed in 31 of 523 (5.9%) patients.

Table 4 Change from baseline in clinical laboratory and safety parameters (safety population)

a N=patients who had a baseline and ≥1 postbaseline measurement for the given parameter.

b Mean change (SD) from baseline at the end of the open-label treatment period.

Mean increases in body weight and waist circumference were observed during open-label treatment with cariprazine (Table 4); 26.3% of patients had a ≥7% increase from baseline in body weight. Patients categorized as underweight (BMI < 18.5) at baseline had the highest percentage of clinically significant weight gain (40%). The percentages of patients with a significant weight increase in BMI subgroups categorized as normal (18.5 to ≤25), overweight (25 to <30), and obese (≥30) were 33.3, 27.7, and 15.1%, respectively.

Mean creatine phosphokinase (CPK) values were increased at the end of open-label treatment; however, in patients completing the full 48 weeks, mean CPK values decreased from baseline (–1.81 U/L). An increase in CPK value from normal at baseline to >1.5 times the upper normal limit at the end of treatment was observed in 41 (9.8%) patients, and most such increases appeared spontaneously and returned to prestudy levels with continued administration of cariprazine. A total of 10 patients had CPK values greater than 5,000 U/L or greater than 1,000 U/L with positive urine myoglobin; 2 patients had SAEs associated with CPK elevations. In one patient, an SAE of blood creatine phosphokinase increase (>29,000 U/L with positive urine myoglobin) led to study discontinuation. In another patient, an SAE of muscle injury (possibly related to vigorous exercise) was reported with a CPK of 32,280 U/L and positive urine myoglobin; laboratory values gradually decreased to prestudy levels. One additional patient with a nonserious AE of increased blood CPK (14,940 U/L) in addition to other laboratory value AEs was also discontinued from the study.

Small mean increases in liver biochemistry parameters were not considered clinically relevant, and no patient met Hy’s law criteria (alanine aminotransferase [ALT] or aspartate aminotransferase [AST] ≥3 times the upper limit of normal [ULN] concurrent with total bilirubin ≥2 times ULN and alkaline phosphatase <2 times ULN). 27 Two patients discontinued treatment due to increased ALT (227 and 309 U/L) and AST (132 and 238 U/L), and one patient discontinued due to increased bilirubin (35.92 μmol/L). Mean prolactin levels decreased during open-label treatment (–15.3 ng/mL).

Cardiovascular safety

Mean changes from baseline in blood pressure and pulse were not considered clinically meaningful (Table 5); 20.5% of patients met the criteria for orthostatic hypotension (defined as a ≥20-mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure or a ≥10-mmHg reduction in diastolic blood pressure while changing from a supine to a standing position), but there were no reports of syncope. For ECG assessments, mean ventricular heart rate and QTc interval decreased following open-label cariprazine treatment. One (0.2%) patient had a postbaseline QTcF value >500 msec, and 3 (0.5%) patients had QTcB postbaseline values >500 msec. An increase from baseline of >60 msec in QTcF or QTcB values occurred in 2 (0.3%) and 7 (1.2%) patients, respectively.

Table 5 Change from baseline in cardiovascular safety parameters (safety population)

a n=patients who had a baseline and≥1 postbaseline measurement for the given parameter.

b Mean change from baseline at the end of the open-label treatment period.

Orthostatic hypotension=≥20 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure or ≥10 mmHg reduction in diastolic blood pressure while changing from a supine to a standing position.

QTcB = QT interval corrected for heart rate using Bazett’s formula; QTcF=QT interval corrected for heart rate using the Fridericia formula; SD=standard deviation.

Extrapyramidal symptoms

Mean change (SD) from baseline to the end of open-label treatment was 0.0 (1.48) on the AIMS, 0.1 (1.21) on the BARS, and –0.0 (2.05) on the SAS. The incidences of treatment-emergent parkinsonism (SAS total score ≤3 at baseline and >3 postbaseline) and akathisia (BARS total score ≤2 and >2 postbaseline) were 11.1 and 17.8%, respectively. The most common EPS-related TEAEs (≥5% of patients) were akathisia (15.7%), extrapyramidal disorder (6.7%), tremor (6.7%), and restlessness (5.8%). Among all EPS-related TEAEs, most incidences were considered mild (62.1%) or moderate (35.4%), with 2.6% classified as severe. A total of 5 (0.9%) patients discontinued due to akathisia, 2 (0.3%) due to extrapyramidal disorder, and 1 (0.2%) each due to restlessness, dystonia, parkinsonism, salivary hypersecretion, tremor, and musculoskeletal stiffness.

Suicidal ideation/behavior

No suicidal behavior was recorded on the C–SSRS during open-label treatment. Active suicidal ideation with a specific plan and intent was recorded for 1 (0.2%) patient, and nonspecific active suicidal thoughts was recorded for 4 (0.7%) patients. A total of 11 (19%) patients had positive responses for the least severe category (“wish to be dead”), and 4 patients had SAEs of suicidal ideation (all concurrent with hallucinations or exacerbation of schizophrenia), with no reported suicidal behavior (3 of whom discontinued the study). One additional patient discontinued the study with a suicidal ideation AE that was secondary to increased psychosis.

Ophthalmologic examinations

Ophthalmologic examinations revealed no evidence of retinal toxicity or cataracts. The overall incidence of ocular TEAEs was 5.6%; in these patients, the most commonly reported ocular TEAEs were blurred vision (1.9%) and dry eye (0.7%). All other ocular TEAEs were reported in <1% of patients. One patient discontinued the study due to a TEAE of optic neuropathy that was considered unrelated to cariprazine.

Efficacy

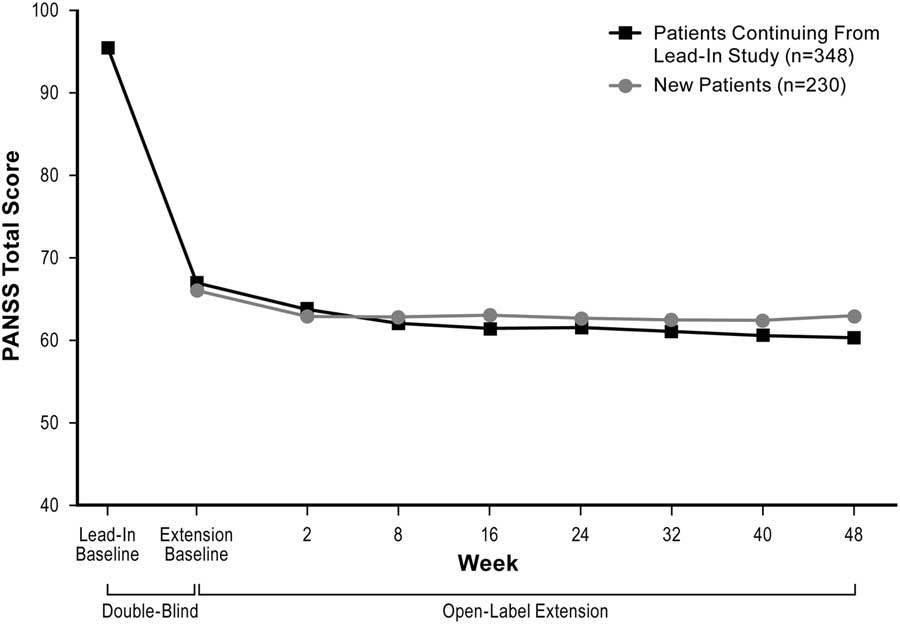

Mean PANSS total scores decreased over the course of the study (Figure 2). Mean (SD) change from the extension baseline to week 48 was –5.0 (14.0) using LOCF analysis and –12.0 (13.2) using OC analysis. Mean reductions from the extension baseline to week 48 were also observed on the PANSS positive subscale (LOCF: –1.6 [4.6]; OC: –3.5 [4.0]) and PANSS negative subscale (LOCF: –1.3 [4.0]; OC: –2.6 [4.5]) scores; CGI–S scores (LOCF: –0.1 [0.8]; OC: –0.5 [0.7]); and SQLS–R4 scores (LOCF: –4.4 [21.3]; OC: –10.7 [21.4]).

Figure 2 Change in mean PANSS total score (ITT population, LOCF).

Mean CDR attention test scores were similar at baseline and week 48; mean CTT scores were lower at week 48 than at baseline. Data for both the CDR attention tests and the CTT were highly variable (data not shown).

Discussion

In this open-label study conducted to evaluate the long-term safety and tolerability of cariprazine in the treatment of adults with schizophrenia, flexibly dosed cariprazine 3–9 mg/d was generally safe and well tolerated for up to a year. In addition, there was no signal of worsening on efficacy measures during the 48-week open-label treatment period; numerical improvements were observed on all efficacy assessments following 48 weeks of cariprazine treatment.

The safety and tolerability profile of cariprazine in our study was consistent with those observed in prior 6-week, double-blind placebo-Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 and active-controlledReference Durgam, Starace and Li 15 , Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 studies in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia, as well as in a previous 48-week, open-label extension study in patients with schizophrenia.Reference Durgam, Greenberg and Li 18 The incidence of TEAEs in our current long-term study (81%) was comparable to the incidence observed in cariprazine-treated patients in short-term studies (61–78%);Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 , Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 the majority of TEAEs were mild or moderate in intensity, and more than half were considered related to cariprazine treatment. The only individual TEAEs classified as SAEs in ≥1% of patients were related to exacerbation of psychotic disorder or social circumstances. Similarly, exacerbation of schizophrenia and psychotic disorder were the only AEs leading to discontinuation in ≥1% of patients. The incidence of these events in our study was similar to that observed with other antipsychotics in other long-term maintenance studies;Reference Chrzanowski, Marcus, Torbeyns, Nyilas and McQuade 28 , Reference Cutler, Kalali, Mattingly, Kunovac and Meng 29 psychotic exacerbation in long-term studies of antipsychotic treatment may reflect poor treatment compliance, which is the most common reason for psychotic relapse in this patient population.

Akathisia was the most commonly reported TEAE (16%), and 78% of the incidences of akathisia occurred during the first 5 weeks of the study. The overall incidence of akathisia in our long-term study was similar to what was observed in the short-term lead-in studies (15% for fixed-dose cariprazine 6 mg/d;Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 and 16 and 17% for fixed/flexible-dose cariprazine 3–6 and 6–9 mg/d, respectivelyReference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 ). There were no akathisia SAEs, and <1% of patients discontinued cariprazine treatment due to akathisia. Of note to clinicians, akathisia tends to be dose-related,Reference Kane, Fleischhacker, Hansen, Perlis, Pikalov and Assunção-Talbott 30 and the fast titration schedule applied in our study (up 6 mg/d by day 5) may have contributed to the rate of akathisia, considering the long half-life of cariprazine and its two active metabolites (especially didesmethyl cariprazine, which has a half-life of over a week). In general, the rates of akathisia and other EPS-related TEAEs in our study were comparable to other atypical antipsychotics following long-term treatment.Reference Keks, Ingham, Khan and Karcher 31 – Reference Citrome, Cucchiaro and Sarma 35

Some antipsychotics are associated with substantial weight gain, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance, all of which may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetesReference Newcomer 36 and can contribute to nonadherence. Despite the observation of some weight gain as described below, long-term treatment with cariprazine in this open-label uncontrolled (no placebo) study was not associated with clinically relevant changes in metabolic parameters, with the possible exception of increased serum glucose. For cholesterol, mean total (–5.3 mg/dL), LDL (–3.4 mg/dL), and HDL (–1.3 mg/dL) levels decreased, as did the level of triglycerides (–1.7 mg/dL), while an increase in glucose (4.9 mg/dL) was observed at the end of the 48-week treatment period. These findings are consistent with the short-term lead-in studies,Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 , Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 as well as with a previous 48-week extension study in patients with schizophrenia,Reference Durgam, Greenberg and Li 18 and they suggest that cariprazine may have a favorable metabolic profile. Weight gain and metabolic disturbances are clearly associated with schizophrenia and with medication treatments. While the data were favorable in this study, the lack of a placebo control limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions about the long-term weight gain and metabolic profile of cariprazine.

Open-label treatment with cariprazine 3–9 mg/d was associated with a small mean increase in body weight (+1.5 kg) at the end of open-label treatment. This increase was comparable with changes observed with cariprazine 6–9 mg/d during the 6-week lead-in study (+1.2 kg) and slightly higher than the changes observed with cariprazine 3–6 mg/d (+0.6–0.8 kg) or aripiprazole 10 mg/d (+0.7 kg) in the 6-week lead-in studies.Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 , Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 The percentage of patients who experienced a ≥7% gain in body weight (26%) in our study is comparable to or lower than the percentages observed in studies of similar length with other atypical antipsychotics. In a one-year double-blind study of aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia, 21% experienced a weight increase of 7% or more.Reference Fleischhacker, McQuade, Marcus, Archibald, Swanink and Carson 33 In contrast, in a 52-week, randomized, double-blind, comparative study of olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine in patients with first-episode psychosis, a weight gain ≥7% was noted in substantially higher percentages of patients (olanzapine 80%; risperidone 58%; quetiapine 50%).Reference McEvoy, Lieberman and Perkins 37 Furthermore, observations from two 6-week, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled cariprazine studies found that rates of significant weight gain were similar between cariprazine and aripiprazole (both 6.0%) in one studyReference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 and lower with cariprazine (8%) than risperidone (17%) in the other.Reference Durgam, Starace and Li 15 In the current study, the highest incidence of weight gain occurred in patients categorized as underweight (BMI<18.5) at baseline (40%), and the lowest incidence occurred in patients who were obese (BMI≥30) at baseline (15%). These results are consistent with findings from a previous analysis of patients treated with atypical antipsychotics that suggested that low baseline BMI (<25 kg/m2) may be associated with a higher risk of weight gain.Reference Lee, Park, Patkar and Pae 38

Some atypical antipsychotics have also been associated with a number of other adverse effects, such as QT prolongation, hyperprolactinemia, and sedation. In our study, mean changes in blood pressure, pulse rate, and ECG were not clinically relevant. Mean ventricular heart rate and QTc interval was decreased at the end of treatment, and very few patients experienced clinically meaningful changes in ECG parameters. In the current study, orthostatic hypotension tended to be asymptomatic with no associated syncope or dizziness. The incidence was 20.5%, slightly higher than that observed in the short-term lead-in studies, although it is difficult to compare due to the variable incidences of orthostatic hypotension seen with different fixed- and flexible-doses of short-term cariprazine (12–13% for placebo;Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 , Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 18 and 12% for fixed-dose cariprazine 3 and 6 mg/d, respectively;Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 16 and 7 and 13% for fixed/flexible-dose cariprazine 3–6 and 6–9 mg/d, respectivelyReference Kane, Zukin and Wang 17 ). In general, long-term use of cariprazine does not appear to be associated with increased risk of orthostatic hypotension.

Cariprazine was not associated with elevated prolactin levels. A mean decrease in prolactin levels was observed at the end of the one-year treatment period, which may be expected from an agent with a D2 partial agonist receptor profile such as cariprazine. Similar to the lead-in studies, long-term cariprazine treatment in our study was associated with a low incidence of sedation or somnolence (both occurred in <4% of patients). Ophthalmologic examinations revealed no evidence of clinically significant retinal toxicity or cataracts over the 48-week treatment period in our study. Ophthalmologic testing was conducted during this long-term study in response to a finding of cataract formation in 13-week and 1-year preclinical toxicity studies of cariprazine in beagle dogs. However, consistent with other short- and long-term studies of cariprazine in humans, no clinically significant ophthalmologic changes were observed in the current study.

Although the primary objective of this open-label study was to evaluate the long-term safety and tolerability of cariprazine, efficacy assessments were collected and evaluated. PANSS scores (total, positive, and negative), CGI–S scores, and SQLS–R4 scores decreased over the course of the study, suggesting that overall symptomatology and quality of life improved with long-term treatment. Without a placebo- or active-control group for comparison, no efficacy conclusions can be drawn; however, the data indicate that no decrease in efficacy was observed after a year of cariprazine treatment. This finding is consistent with data from other long-term open-label antipsychotic trials in patients with schizophrenia, suggesting that these agents may continue to be effective over the course of long-term treatment.Reference Chrzanowski, Marcus, Torbeyns, Nyilas and McQuade 28 , Reference Cutler, Kalali, Mattingly, Kunovac and Meng 29

A previous 48-week open-label extension study evaluated the safety and tolerability of cariprazine at low doses (1.5–4.5 mg/d) in patients with schizophrenia.Reference Durgam, Greenberg and Li 18 The present study was designed to augment these results by investigating the one-year safety and tolerability of cariprazine at higher doses (6–9 mg/d). Currently, the FDA-approved dose range for the treatment of schizophrenia is 1.5–6 mg/d; doses >6 mg/d are not FDA-approved due to concerns about a potential dose–response relationship for certain safety parameters. The results of the two long-term studies were generally consistent, with no evidence of new tolerability issues in the higher cariprazine dose range. Of note, the overall completion rate in this higher-dose-range study (39%) was lower than the completion rate in the low-dose study (49%); however, the low-dose trial only included patients continuing from a lead-in study, and the completion rate for patients who entered this trial from a lead-in study (47%) was comparable. New patients discontinued at a higher rate than continuing patients for all the reasons recorded, with the greatest differences being observed between those committing protocol violations (continuing patients 6%, new patients 11%) and those lost to follow-up (continuing patients 5%, new patients 11%). Most safety parameters, including incidences of common TEAEs, treatment-emergent akathisia and parkinsonism, metabolic changes, and changes in body weight, were similar between the two studies.

The heterogeneity of the patient population entering our study is a limitation of note. Approximately half of the patients were new patients who did not participate in either lead-in study, while the remaining participants were a combination of patients who had received placebo, cariprazine, or aripiprazole in the lead-in studies. While all patients underwent a one-week washout period, prior treatment may have resulted in a high degree of patient variability. For example, changes in weight and waist circumference may have been biased depending on whether patients had received previous treatment in a lead-in study or were newly entering the study. Additional limitations include the open-label design of the study, which did not allow for comparison with a placebo or a comparator antipsychotic control group. While the flexible-dose design allowed for individual dosing strategies and is more representative of true clinical practice, it limits one’s ability to fully assess the safety and tolerability of individual doses. Despite demonstrating efficacy in a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study and being an approved dose, 1.5 mg/d was not studied here. Additionally, the titration schedule may have been faster than what would ideally occur in clinical practice, especially given the long half-life of one of the active cariprazine metabolites (didesmethyl cariprazine). Although withdrawal of consent, which was recorded for 26% of patients, is typically a consequence of undisclosed AEs or a lack of efficacy, the contributing factors in our study may have included the stringent participation criteria, including the need for informed consent from both patient and caregiver, the requirement that the caregiver be present or assist in the patient’s compliance with study visits, and the long duration of the study. The occurrence of additional AEs was excluded as a cause for withdrawal of consent via follow-up communication with the study sites.

Conclusions

The results from our study are consistent with a previous 48-week study and support the long-term safety and tolerability of cariprazine in adult patients with schizophrenia. No new safety concerns associated with the long-term use of cariprazine at doses up to 9 mg/d were revealed, and there was no evidence of diminished efficacy with cariprazine one year after treatment initiation. The distinct mechanism of action and the collective safety results suggest that cariprazine is generally a safe and effective long-term treatment for schizophrenia and that it is an important addition to other available treatment options.

Disclosures

Andrew Cutler reports grants and personal fees from Acadia, grants and personal fees from Allergan, grants and personal fees from Alkermes, grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants from Braeburn, grants and personal fees from Forum, grants and personal fees from Intra-Cellular Therapies, grants from Janssen, grants from Lilly, grants and personal fees from Lundbeck, grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants and personal fees from Noven, grants and personal fees from Otsuka, grants from Pfizer, grants from Reckitt Benckiser, grants and personal fees from Sunovion, grants and personal fees from Takeda, grants and personal fees from Teva, all outside the submitted work.

Suresh Durgam reports other from Allergan (formally Forest Research Institute), during the conduct of the study; other from Allergan (formally Forest Research Institute), outside the submitted work.

Yao Wang has nothing to disclose.

Raffaele Migliore reports other from Allergan Plc. (formally Forest Research Institute), outside the submitted work.

Kaifeng Lu reports other from Allergan PLC (formally Forest Research Institute), outside the submitted work.

István Laszlovszky reports personal fees from Gedeon Richter Plc., outside the submitted work; in addition, he holds a patent for cariprazine.

György Németh reports personal fees from Gedeon Richter Plc., outside the submitted work. In addition, he holds a patent for cariprazine.

The study was funded by Forest Research Institute Inc., an Allergan affiliate (Jersey City, New Jersey, USA), and Gedeon Richter Plc. (Budapest, Hungary). Forest Research Institute and Gedeon Richter Plc. were involved in the study design, collection (via contracted clinical investigator sites), analysis, and interpretation of the data, and the decision to present these results. Editorial and writing assistance was provided by Paul Ferguson of Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, Illinois, USA), a contractor for Allergan Inc.