Introduction

Symptomatic urinary tract infection (ie, SUTI 1 ) is a common bacterial infection, occurring both in community health settings and in acute-care hospitals. Reference Foxman2 The severity of SUTI range from mild, simple cystitis, to a severe life-threatening systemic infection. Reference Foxman2,Reference Ronald3 More than 90% of SUTI offending pathogens, belong to the Enterobacterales family (eg, Escherichia coli). Reference Foxman2,Reference Ronald3 Extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) production among community-onset (CO) Enterobacterales isolates- particularly E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis -had become endemic worldwide. Reference Adler, Katz and Marchaim4 In 2024 the World Health Organization (WHO) classified these ESBL-producing Enterobacterales as “priority pathogens,” underscoring their global burden and threat on public health. 5 Despite this statement, controlled evidence from the community health settings, regarding the epidemiology of ESBL infections, remains limited. Reference Ben-Ami, Rodriguez-Bano and Arslan6–Reference Rodriguez-Bano, Picon and Gijon8 This is especially evident in mild SUTI, a common infectious syndrome that is often managed exclusively in the community.

In controlled trials, which were executed primarily at acute-care hospitals, not in community settings, invasive ESBL infections were significantly associated with worse patients’ outcomes (in comparison to patients with Enterobacterales susceptible infections, and in comparison to uninfected controls), primarily resulting from delays in initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy (DAAT). Reference Bradford9,Reference Kliebe, Nies, Meyer, Tolxdorff-Neutzling and Wiedemann10 DAAT is a strong modifiable independent predictor of mortality in severe sepsis, Reference Paul, Shani, Muchtar, Kariv, Robenshtok and Leibovici11 and specifically in ESBL infections. Reference Marchaim, Gottesman and Schwartz12 Although its impact on outcomes in milder infections may be less pronounced, Reference Paul, Shani, Muchtar, Kariv, Robenshtok and Leibovici11 identifying independent predictors of CO-ESBL SUTI—even in mild cases—could improve empiric prescribing practices and patient outcomes.

Matched case-case-control design is the gold standard methodology to determine independent predictors for acquisition of a multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) in general, Reference Kaye, Harris, Samore and Carmeli13 and specifically of ESBL infections Reference Vock, Aguilar-Bultet, Egli, Tamma and Tschudin-Sutter14 in hospitals. In the community, it is less established which patients should represent the source population from which the ESBL SUTI cases had “epidemiologically evolved.” Currently, there is lack in both case-case-control studies (ie, using a group of matched uninfected controls to reflect the source population) and lack of case-case studies (ie, using a group of matched patients with non-ESBL SUTI to reflect the source population) to explore the independent predictors of CO-ESBL SUTI managed in community settings. Reference Apisarnthanarak, Kiratisin, Saifon, Kitphati, Dejsirilert and Mundy15,Reference Tinelli, Cataldo and Mantengoli16

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recently revised its treatment guidelines for ESBL-producing Enterobacterales infections. Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 Nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) are recommended as preferred oral options for mild ESBL cystitis, provided the isolates are susceptible. Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 The IDSA discourages the use of oral fluoroquinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin) for this indication due to resistances and adverse events. Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 Oral amoxicillin–clavulanate is also strongly discouraged; Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 however, because it often appears on microbiology reports as a theoretically “valid” oral beta-lactam option, it may still be prescribed by non-specialists when isolates show phenotypic in-vitro susceptibility. Reference Warren, Abrutyn, Hebel, Johnson, Schaeffer and Stamm18 Fosfomycin is another oral option mentioned in the IDSA guidelines, but due to the current US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) registration restrictions and lack of breakpoints, fosfomycin is used in the United States. only for uncomplicated E. coli cystitis, in a single oral dose of three grams (regardless of ESBL production). Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 In several countries outside the United States, including in Israel, oral fosfomycin is administered for mild ESBL cystitis in three repeated doses of three grams, for three consecutive days, although controlled data pertaining to the effectiveness of this regimen are scarce. Reference Rouphael, Winokur and Keefer19

The aims of our study were: (1) to identify the independent predictors of CO-ESBL SUTI, and (2) to compare the effectiveness of oral regimens used for this indication. This could improve empiric prescribing (aim 1) and therapeutic management (aim 2) of ESBL SUTI in community health settings.

Methods

A retrospective observational matched case-case-control study Reference Kaye, Harris, Samore and Carmeli13 and a matched case-case study were conducted among insurers of Maccabi healthcare health maintenance organization (HMO), from the Shfella district, Israel, for two consecutive months (10–11/2019). Maccabi health care is the second largest HMO in the country, with over 600,000 insurers listed to the Shfella district. All positive urine cultures were reviewed, defined according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria, that is, as ≤2 pathogens and inoculum growth >105 CFU/mL 1 . Unique adult patients (>18 years) were included, who had either E. coli, K. pneumoniae, or P. mirabilis CO SUTI, determined according to CDC definitions. 1 Patients were included only if they had symptomatic UTI (eg, dysuria, high frequency, suprapubic pain or urgency, with or without fever and hematuria). Reference Nelson, Aslan and Beahm20,Reference Bono and Leslie21 Patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria were excluded. Complicated UTI (cUTI) was determined according to IDSA definition. 22 ESBL was diagnosed using the automated VITEK-2 (bioMérieux Inc., France), in accordance with CLSI 2019 criteria and breakpoints. Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie23 Patients with carbapenem-resistant and/or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales were excluded. The HMO ethic committee had approved the study prior its initiation.

The study comprised of three groups: (1) patients with CO-ESBL SUTI, (2) Patients with CO-non-ESBL SUTI, and (3) Uninfected controls without SUTI or any other active infection. Reference Kaye, Harris, Samore and Carmeli13 If ESBL was isolated in a polymicrobial culture, the patient was considered an ESBL “case.” Matching patients with CO-ESBL SUTI to patients with CO-non-ESBL SUTI (from the same 2-month study period) was in accordance with three parameters (listed in order of importance Reference Harris, Samore, Lipsitch, Kaye, Perencevich and Carmeli24 ): (1) bacteria type, (2) age group (in decades), and (3) place of residency (home versus any long-term care facility [LTCF]). The last criterion reflects the ambulatory equivalent to the parameter “time at risk,” to avoid over-matching for certain potential important predictors (eg, female sex, acute illness indices), in accordance with the established case-case-control methodology. Reference Harris, Samore, Lipsitch, Kaye, Perencevich and Carmeli24 Matching patients with CO-ESBL SUTI to uninfected controls for the case-case-control study was in accordance (listed in order of importance Reference Harris, Samore, Lipsitch, Kaye, Perencevich and Carmeli24 ): (1) age group (in decades), (2) place of residency (home versus LTCF), and (3) if they visited the same family clinic, at the same day (for a non-infectious complaint), as their matched ESBL case.

Since it is difficult to determine in the ambulatory settings the “appropriate” source population from which patients with ESBL SUTI had “epidemiologically evolved,” we determined the independent predictors for CO-ESBL SUTI in two separate analyses. First, is the “classical” case-case-control design, Reference Harris, Samore, Lipsitch, Kaye, Perencevich and Carmeli24 that is, the eventual predictors would be those associated with ESBL SUTI in its model versus uninfected controls (model 1), but which are not associated as well, with CO-non-ESBL SUTI in its model versus uninfected controls (model 2). The second analyses would be a case-case study, that is, the eventual predictors would be those associated with ESBL SUTI in its direct comparison to patients with non-ESBL SUTI (model 3).

The comparative effectiveness analyses of the various oral agents (study aim 2), were determined according to the outcomes of CO-ESBL SUTI patients who were treated with a single oral agent (for up to 14 days), for which their initial ESBL isolate was susceptible (in vitro Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie23 ). Since the study focused on patients with milder SUTI who were managed in the community (at least initially) with oral agents, patients who were immediately referred during the initial SUTI visit to the emergency room, or to home parenteral therapy (through a home IV team), were excluded (but were included in the ESBL predictors’ analyses, that is, study aim (1). However, referral to hospital or to home IV following the initial visit were captured as treatment failures. The oral regimens for ESBL SUTI that were compared (ie, embedded in the HMO electronic medical records system, to be used according to prescriber’s discretion): (1) nitrofurantoin (300 mg daily administered for 5–7 days), (2) TMP-SMX (for 5–7 days), (3) fluroquinolone (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, or ofloxacin for up to 7 days), (4) fosfomycin (3g daily, administered for 3 consecutive days), and (5) amoxicillin-clavulanate (875 mg amoxicillin/125 mg clavulanic acid twice daily for 7 days). Since SUTI is a mild condition with difficulties to determine the outcome based on retrospective charts review, we created a composite outcome to determine treatment failure. The composite outcome was met, if in the 14 days following the initial SUTI visit, patients had experienced any of the following: (1) clinical failure (documentation of continued SUTI symptoms or complains), (2) bacteriological failure (additional positive urine culture/s), (3) referral to emergency room or to home IV, (4) hospitalization, or (5) death (any cause).

Statistical analyses were executed with IBM SPSS 29.0 (2024). Univariable matched analyses, followed by multivariable matched analyses (logistic regression, stepwise backward selection), were executed to determine the independent predictors for CO-ESBL SUTI by comparing patients with CO-ESBL SUTI to uninfected controls (model 1), patients with CO-non-ESBL SUTI to uninfected controls (model 2), Reference Kaye, Harris, Samore and Carmeli13 and patients with CO-ESBL SUTI to patients with CO-non-ESBL SUTI (model 3). Predictors that were independently associated with CO-ESBL SUTI in model 1 but not with CO-non-ESBL SUTI in model 2 (case-case-control design), and the independent predictors per model 3 (case-case design), were considered potential independent predictors for CO-ESBL SUTI Reference Kaye, Harris, Samore and Carmeli13 (study aim 1). Variables with significant association (P < .05) per univariable analyses, were incorporated to the multivariable models. Models were tested for confounding and collinearity. Reference Bach, Wallisch and Klein25 SUTI acute illness indices, DAAT, and categorical and time-dependent outcomes, were compared only between the patients with CO-ESBL SUTI and the patients with CO-non-ESBL SUTI, using logistic and Cox regressions, respectively. χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare the effectiveness of the various oral agents, versus categorical outcomes, including the composite outcome (study aim 2).

Results

Descriptive analyses

There were 13,597 positive urine cultures 1 of Enterobacterales (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. mirabilis only) during the 2-month study period. After applying all inclusion criteria as depicted above, 1,455 unique patients were included in the final cohort, divided to three perfectly matched groups of 485 patients (Table 1): patients with CO-ESBL SUTI, patients with CO-non-ESBL SUTI, and uninfected controls. None of the patients died (of any cause) in the 14 days following the index visit. The mean population’s age was 58 ± 19 years and 1,144 (79%) were females. At baseline, 96 patients (6.6%) were functionally dependent, Reference Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson and Jaffe26 36 (2.5%) were chronic LTCF residents, and 22 patients (1.5%) had a urinary catheter. There were 446 (31%) patients with documentation of recent SUTI (in the previous 6 months), 557 (38%) had received antibiotics in the previous 3 months (for any indication), and 185 (12.7%) patients were known ESBL carriers from the previous year. The median Charlson’s weighted index comorbidity for the entire population was 1 (IQR = 0–2).

Table 1. Univariable comparisons between patients with CO-ESBL SUTI, CO-non-ESBL SUTI, and uninfected controls (485 patients in each group), maccabi health care, 10–11/2019

Notes. CO, community-onset; ESBL, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales; SUTI, symptomatic urinary tract infection; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals; SD, standard deviation; IQR, Interquartile range; MDRO, multidrug-resistant organism; BLBLI, beta-lactam beta-lactamase inhibitors combinations; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; Dx, diagnosis; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection.

a Valid percent: count divided by the total number of valid observations (after excluding the missing information from the denominator).

b Permanent devices: Patient has chronic/permanent device, that were in place at the date of SUTI initiation, eg., urinary catheter, tracheotomy, central line of any type, insulin pump, intra-uterine devices, orthopedic external fixators, implanted defibrillator, pacemaker, drains of any sort. Prosthetic heart valves, ileal conduit, joint prostheses, internal stents (eg, bile, coronary), were not captured as permanent devices.

c Past invasive procedure: Patient has had any type of invasive procedure in the prior six months, for example, any type of surgery (from minor to major), endoscopy, permanent central line insertion, lumbar puncture (LP), feeding tube insertion, abscess drainage, bone marrow biopsy, emergent dialysis.

d Past MDRO include any of the following: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), carbapenem-resistant or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CRE or CPE), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), ESBL-producing Enterobacterales, Acinetobacter baumannii, or Pseudomonas aureginosa.

e Chronic renal disease: serum creatinine≥1.7mg%. 28

f Chronic lung diseases include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, restrictive lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, bronchiectasis.

g Connective tissue disease include rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), scleroderma, vasculitis, psoriasis, gout, sarcoidosis.

h Glucocorticoids exposures were captured if administered for more than 48 hours in the past month.

i Immunosuppression / immunomodulation in the prior 3 months include any of the following: (1) neutropenia (<500 neutrophils) present at day of culture, (2) Glucocorticoid / steroid use for >48 hours in the past month, (3) Patient had received chemotherapy in the past 3 months, (4) Patient had received radiotherapy in the past 3 months, (5) Patient has HIV, (6) Patient has had a bone marrow or solid organ transplantation, and (7) Immunomodulators therapy in the past 3 months (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, etanercept).

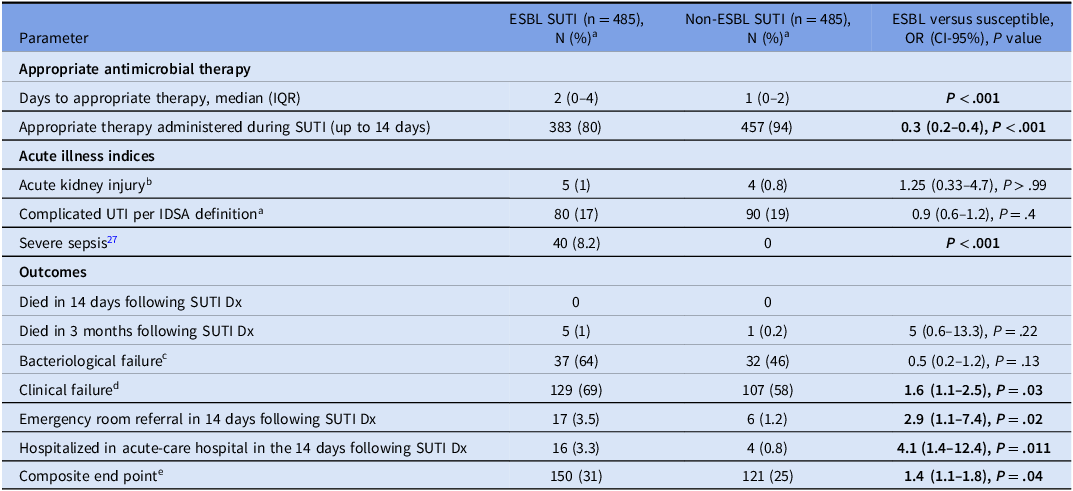

Of the 970 SUTI patients depicted in Table 2 (ie, 485 patients with CO-ESBL SUTI and 485 patients with CO-non-ESBL SUTI), 736 patients (76%) had E. coli, 208 (21%) had K. pneumoniae, and 26 (3%) had P. mirabilis. There were 170 (17.5%) patients with cUTI. Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 Overall, 841 (87%) patients had received appropriate antimicrobials, which was initiated in a median of one day (IQR = 0–4) from the index visit. There were 236 patients with documented clinical failure (ie, 24% of the entire SUTI cohort and 63% of the patients who had any additional documented visit to ambulatory clinic in the following 14 days) and 69 patients with documented bacteriological failure (ie, 7% of the entire SUTI cohort and 70% of the patients from which additional urine culture were obtained in the following 14 days). During the course of SUTI (up to day 14), 23 (2.4%) patients were referred to emergency rooms and 20 (2%) were hospitalized. Overall, 271 patients (28%) had met the composite worse outcome definition. As depicted in Table 2, Patients with ESBL SUTI suffered significantly from worse outcomes, that is, with higher rates of clinical failures, ER referrals, hospitalizations, and of the composite outcome. Of note, patients with non-ESBL SUTI had higher rates of bacteriological failures, though this was an insignificant statistical association.

Table 2. Antimicrobial management, acute illness indices, and outcomes, of patients with community-onset (CO) symptomatic urinary tract infections (SUTI), Maccabi health care, 10–11/2019 (n = 970)

Notes. ESBL, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales; SUTI, symptomatic urinary tract infection; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals; SD, standard deviation; IQR, Interquartile range; Dx, diagnosis.

a Valid percent: count divided by the total number of valid observations (after excluding the missing information from the denominator).

b Acute kidney injury was defined as a rise in serum creatinine by ≥1.5-fold.

c Bacteriological failure: continued positive urine culture within 14 days following culture date, only among patients that a culture was repeated.

d Clinical failure: continued SUTI’s symptoms or complains documented within 14 days following culture date.

e Composite end point was determined based of the presence of any one of the following parameters: bacteriological failureb, clinical failurec, referral to the emergency room, or had to be hospitalized.

Predictors for CO-ESBL SUTI

The univariable comparisons between the three groups of patients are depicted in Table 1. Many of the epidemiological parameters were significantly associated with both CO-ESBL SUTI and CO-non-ESBL SUTI in comparisons versus uninfected controls: eg, female sex, certain background conditions (eg, recent prior SUTI, known carrier from the past year of ESBL or other MDRO, functionally dependent, Reference Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson and Jaffe26 cognitively impaired, malignant tumor, elevated Chalson’s scores, Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie23 immunosuppressive conditions/states), and various recent healthcare exposures (eg, invasive procedure, urologic procedure, antibiotics in general and to certain classes in particular). However, there were certain epidemiological parameters, which were significantly associated only with CO-ESBL SUTI, but not with SUTI in general in the bivariable comparisons: eg recent hospitalization, permanent invasive device, the presence of a urinary catheter at the initial SUTI visit, and recent pregnancy or delivery. The epidemiological features that were associated with CO-non-ESBL SUTI (compared to uninfected controls), but not with CO-ESBL SUTI (compared to uninfected controls), were advanced nursing care administered at home, and congestive heart failure as a background condition (Table 1).

The bivariable analyses of the acute illness indices and of the outcomes, compared only the group of patients with CO-ESBL SUTI to the group of patients with CO-non-ESBL SUTI (Table 2). Patients with CO-ESBL SUTI had suffered significantly more often from severe sepsis indices, Reference Singer, Deutschman and Seymour27 from DAAT, referrals to emergency rooms, hospitalizations during the course of SUTI, and from an overall increase rate of the composite outcome.

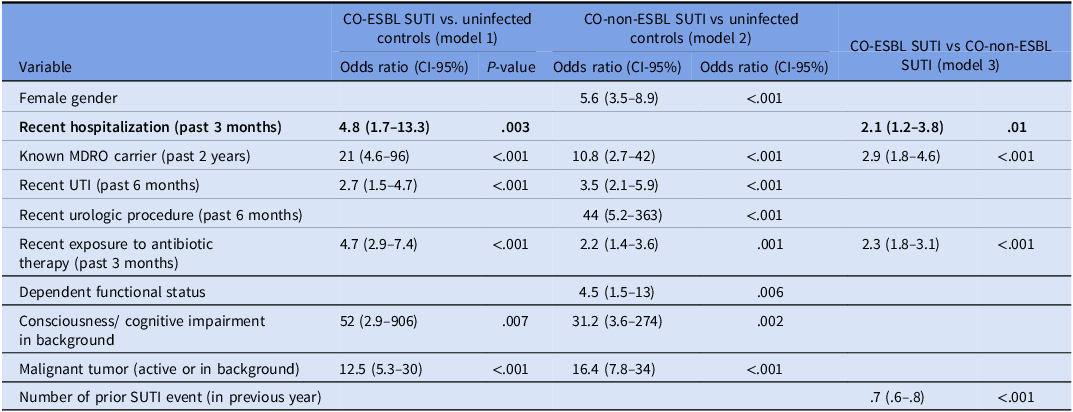

Table 3 summarize the final multivariable risk factors models for CO-ESBL SUTI versus uninfected controls (model 1), for CO-non-ESBL SUTI versus uninfected controls (model 2), and for CO-ESBL SUTI versus CO-non-ESBL SUTI (model 3). As highlighted in the table, the only parameter that was independently and significantly associated with model 1, but not with model 2 (ie, the case-case-control study), was recent (3 months) hospitalization in an acute-care facility. The independent predictors for CO-ESBL SUTI as per model 3 were again recent (3 months) hospitalization, in addition to carriage of MDRO from the previous two years, recent (3 months) exposure to (any) antimicrobial agent, and documented SUTI events from the past year (ie, the case-case study).

Table 3. Multivariable models of predictors for community-onset (CO) symptomatic urinary tract infections (SUTI), Maccabi health care, 10–11/2019

Notes. ESBL, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales; CI, confidence intervals; MDRO, multidrug-resistant organism; SUTI, symptomatic urinary tract infection.

Efficacy analyses of oral therapeutics used for CO-ESBL SUTI

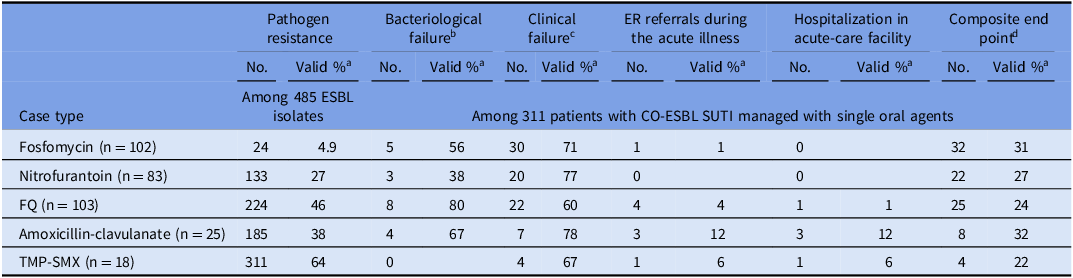

There were 331 patients with CO-ESBL SUTI, who were managed with a single oral agent, for which the ESBL isolate was susceptible (in vitro). As depicted in Table 4, fosfomycin had the lowest resistance rates to ESBL strains (4.9%), while TMP/SMX (64%) and fluroquinolones (46%) had the highest resistance rates. The outcomes of patients with ESBL SUTI were generally unfavorable, and overall, 91 patients (28%) had met the composite worse outcome definition. The agent with the lowest composite outcome rate (22%) was TMP/SMX, while the agent with the worse composite outcome rate (32%) was amoxicillin-clavulanate.

Table 4. Resistance rates and effectiveness of oral antimicrobials used for treatment of community-onset (CO) extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacterales (ESBL) symptomatic urinary tract infections (SUTI), Maccabi health care, 10–11/2019

Notes. ER, emergency room; FQ, Fluoroquinolones (eg, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin); TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

a Valid percent: count divided by the total number of valid observations (after excluding the missing information from the denominator).

b Bacteriological failures: continued positive urine culture within 14 days following culture date.

c Clinical failures: continued SUTI’s symptoms or complains documented within 14 days following culture date.

d Composite end point: bacteriological failure, clinical failure, referred to the emergency room, or had to be hospitalized.

Discussion

ESBL SUTI is a common ambulatory infection, and the rapid dissemination of ESBL-producing strains in the community, as declared by the WHO, 5 underscores the substantial burden of antimicrobial resistance on the general population. In this large study (1,455 patients), numerous potential predictors of CO-ESBL SUTI, were identified through bivariable (Table 1) and multivariable (Table 3) analyses. However, after applying the case-case-control design, Reference Kaye, Harris, Samore and Carmeli13 most predictors were associated with CO SUTI in general, with recent hospitalization remaining the only independent predictor specifically linked to CO-ESBL SUTI. In the case-case analysis (ie, with SUTI patients reflecting the background population), recent hospitalization was an independent predictor for ESBL SUTI, along with MDRO carriage from the past two years, recent antimicrobials exposure, and the number of prior SUTI events from the past year (captured as a continuous variable). We recommend that clinicians in this Israeli region consider the possibility of ESBL infection when managing patients with mild CO SUTI who present with any of these four predictors.

As previously reported in hospital settings, Reference Bradford9,Reference Kliebe, Nies, Meyer, Tolxdorff-Neutzling and Wiedemann10 community patients with CO-ESBL SUTI experienced significantly longer DAAT compared with those with CO-non-ESBL SUTI (ie, P < .001, Table 2). The increased DAAT, among other factors, Reference Paul, Shani, Muchtar, Kariv, Robenshtok and Leibovici11 might have resulted significant worse outcomes among patients with CO-ESBL SUTI (Table 2), but this was not one of the study aims and was not analyzed directly . Although none of the 1,455 patients died within 14 days of the index visit (ie, reflecting a population suffering a mild infectious syndrome), 150 of the CO-ESBL SUTI patients (31%) had met the composite definition of worse outcome, ie, implying SUTI treatment failure. This high rate of treatment failure underscores the epidemiologic importance of ESBL SUTI managed in community settings.

The comparative efficacy analysis between the oral regimens used to manage SUTI patients (Table 4), provides “real-world” descriptive data, from 331 patients with CO-ESBL SUTI, 1 despite the relatively small sample size in each treatment arm. As emphasized in recent IDSA treatment guidelines, this field remains characterized by lack of controlled evidence. Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 The outcomes of patients with ESBL SUTI did not differ between the various single oral agents, with nearly one-third of the patients experiencing treatment failure (Table 4). IDSA guidelines recommend to manage mild SUTI (regardless ESBL production) with either TMP/SMX or nitrofurantoin, as long as the offending isolate is susceptible. Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 TMP/SMX indeed displayed the lowest treatment failure rates (22%, with none of the patients experiencing bacteriological failures), but it had the highest initial resistance rates (64%). Nitrofurantoin was associated with composite outcomes rate of 27%, in similar to the other agents (Table 4). The IDSA guidelines also recommend, Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 and this is further supported by this study, that amoxicillin–clavulanate should be avoided for ESBL SUTI, even in mild infections caused by phenotypically susceptible strains. Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie23 The outcomes of patients managed with amoxicillin-clavulanate were the worse among this cohort of patients (32%). Hiding from non-trained prescribers the susceptibility results to amoxicillin-clavulanate should be locally considered. The IDSA guidelines also discourages the usage of fluoroquinolones for mild SUTI, Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17 and indeed 46% of the ESBL offending isolates were a priori resistant (Table 4), in addition to a strong significant association between recent fluoroquinolone usage (3 months) and ESBL SUTI emergence (Table 1). Fosfomycin was commonly prescribed (102 patients), having significant lower resistance rate compared to other agents (4.9%; P < .001). Of note, fosfomycin usage in this study was in three consecutive doses (3 g), administered for three consecutive days. Reference Warren, Abrutyn, Hebel, Johnson, Schaeffer and Stamm18 Despite the low resistance rates (resulting in part from the high benchmark to define non-susceptibility Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie23 ) and the enhanced regimen of 9 g, fosfomycin treatment outcomes were unfavorable (31% meeting the composite outcome definition), as other oral agents. Of note, treatment failure rate among the 8 patients with a fosfomycin susceptible K. pneumoniae ESBL strain, treated with fosfomycin (33%), were similar to the overall treatment failures rates. Reference Tamma, Heil, Justo, Mathers, Satlin and Bonomo17

Our study has several limitations. As an observational, retrospective, chart-review-based investigation, some documentation was missing or inaccurate. However, there is no reason to assume that these biases differentially affected either group, whether in the CO-ESBL SUTI predictors’ analysis (study aim 1) or in the oral agents’ effectiveness analysis (study aim 2). Since the study was executed in a single district from a single country, over a 2-month season, the results cannot be generalized to other locales without validation. However, the case-case-control and the case-case designs applied in this study (study aim 1), executed in community settings, applying established matching processes, Reference Harris, Samore, Lipsitch, Kaye, Perencevich and Carmeli24 and using two methods of analyses to explore independent predictors for CO-ESBL SUTI (to assist clinicians in the community in shortening DAAT), is a methodological strength. Additional limitation, in the treatment effectiveness sub analyses (study aim 2), are the low number of patients subjected to each treatment arm. We used a composite worse outcome, uniting several outcomes that represent SUTI treatment failures, to increase statistical power, acknowledging the natural complexities of capturing outcomes of a mild infectious syndrome, in chart-review retrospective study. Additional limitation, is the fact that outcomes were compared between groups without factoring severity of illness indices (who were commonly subtle ie Table 1), and other parameters that might affected patients’ outcomes. However, the data still project interesting descriptive (non-controlled) information, pertaining to the overall low cure rates of mild ESBL SUTI managed in the community, specifically patients managed with amoxicillin-clavulanate.

To conclude, CO-ESBL SUTI should be suspected, and empirically covered by primary prescribers in the Shfela district, Israel, particularly in patients with recent hospitalization, MDRO carriage, recent antimicrobials exposure, or prior SUTI events. This could reduce DAAT, which was frequent among patients with CO-ESBL SUTI, and improve their outcomes (which were significantly worse). In addition, according to this observational investigation, it is safe to manage CO-ESBL SUTI patients, who are not severely ill at the initial clinical assessment, with either TMP/SMX (although resistance rates are high) or any other agent, avoiding amoxicillin-clavulanate, even when the ESBL isolate is susceptible (in vitro). Further studies are needed to generalize these findings to other settings.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed in partial fulfillment of the M.D. thesis requirements of the Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization: D.M. and A.I.; methodology: S.Z.I. and D.M.; formal analysis: S.Z.I. and D.M.; investigation: S.Z.I., K.A., and D.M.; resources: K.A D.M.; data curation: S.Z.I., M.M., E.L., M.I., I.L., S.M., R.G.L., S.A., K.A., A.I., and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation: S.Z.I. and D.M.; writing—review and editing: S.Z.I. K.A., A.I., and D.M.; supervision: D.M.; project administration: S.Z.I. and D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of this manuscript.

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

All authors had declared no conflict of interests related to the study.