1 Introduction

Ordinal data are ubiquitous in psychology and related fields. With such data, e.g., arising from responses to rating scales, it is often recommended to estimate correlation matrices through polychoric correlation coefficients (e.g., Foldnes & Grønneberg, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2022; Garrido et al., Reference Garrido, Abad and Ponsoda2013; Holgado–Tello et al., Reference Holgado–Tello, Chacón–Moscoso, Barbero–Garcıa and Vila–Abad2010). The resulting polychoric correlation matrix is an important building block in subsequent multivariate models like factor analysis models and structural equation models (SEMs), as well as in exploratory methods like principal component analysis, multidimensional scaling, and clustering techniques (see, e.g., Mair (Reference Mair2018) for an overview). An individual polychoric correlation coefficient is the population correlation between two underlying latent variables that are postulated to have generated the observed categorical data through an unobserved discretization process. Traditionally, it is assumed that the two latent variables are standard bivariate normally distributed (Pearson, Reference Pearson1901) to estimate the polychoric correlation coefficient from observed ordinal data. Estimation of this latent normality model, called the polychoric model, is commonly carried out via maximum likelihood (ML) (Olsson, Reference Olsson1979). However, recent work has demonstrated that ML estimation of polychoric correlation is highly sensitive to violations of the assumption of underlying normality. Violations of this assumption result in a misspecified polychoric model, which can lead to substantially biased estimates of its parameters and those of subsequent multivariate models (Foldnes & Grønneberg, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2019, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2020; Grønneberg & Foldnes, Reference Grønneberg and Foldnes2022; Jin & Yang-Wallentin, Reference Jin and Yang-Wallentin2017), particularly SEMs using diagonally weighted least squares (Foldnes & Grønneberg, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2022), where the latter is based on weights derived under latent normality.

Motivated by the recent interest in non-robustness of ML, we study the estimation of the polychoric model under a misspecification framework stemming from the robust statistics literature (e.g., Huber & Ronchetti, Reference Huber and Ronchetti2009). In this setup, which we call partial misspecification here, the polychoric model is potentially misspecified for an unknown (and possibly zero-valued) fraction of observations. Heuristically, the model is misspecified such that the affected subset of observations contains little to no relevant information for the parameter of interest, the polychoric correlation coefficient. Examples of such uninformative observations include careless responses, misresponses, or responses due to item misunderstanding. Especially careless responding has been identified as a major threat to the validity of questionnaire-based research findings (e.g., Credé, Reference Credé2010; Huang, Liu, et al., Reference Huang, Liu and Bowling2015; Meade & Craig, Reference Meade and Craig2012; Welz et al., Reference Welz, Archimbaud and Alfons2024; Woods, Reference Woods2006). We demonstrate that already a small fraction of uninformative observations (such as careless respondents) can result in considerably biased ML estimates.

As a remedy and our main contribution, we propose a novel way to estimate the polychoric model that is robust to partial model misspecification. Essentially, the estimator poses the question “What is the best fit that can be achieved with the polychoric model for (the majority of) the data at hand?” The estimator compares the observed frequency of each contingency table cell with its expected frequency under the polychoric model, and automatically downweights cells whose observed frequencies cannot be fitted sufficiently well. As such, our estimator generalizes the ML estimator, but, in contrast to ML, does not crucially rely on the correct specification of the model. Specifically, our estimator allows the model to be misspecified for an unknown fraction of uninformative responses in a sample, but makes no assumption on the type, magnitude, or location of potential misspecification. The estimator is designed to identify such responses and to simultaneously reduce their influence so that the polychoric model can be accurately estimated from the remaining responses generated by latent normality. Conversely, if the polychoric model is correctly specified, that is, latent normality holds true for all observations, our estimator and ML estimation are asymptotically equivalent. As such, our proposed estimator can be thought of as a generalized ML estimator that is robust to potential partial model misspecification, due to, for instance (but not limited to), careless responding. We show that our robust estimator is consistent, asymptotically normal, and fully efficient under the polychoric model, while possessing similar asymptotic properties under misspecification, and it comes at no additional computational cost compared to ML.

The partial misspecification framework in this article is fundamentally different from that considered in recent literature on misspecified polychoric models. In this literature (e.g., Foldnes & Grønneberg, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2019, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2020, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2022; Grønneberg & Foldnes, Reference Grønneberg and Foldnes2022; Jin & Yang-Wallentin, Reference Jin and Yang-Wallentin2017; Lyhagen & Ornstein, Reference Lyhagen and Ornstein2023), the polychoric model is misspecified in the sense that all (unobserved) realizations of the latent continuous variables come from a distribution that is nonnormal. Under this framework, which is also known as distributional misspecification, the parameter of interest is the correlation coefficient of the latent nonnormal distribution, and all observations are informative for this parameter. While the distributional misspecification framework led to novel insights regarding (the lack of) robustness in ML estimation of polychoric correlation, the partial misspecification framework of this article can provide complimentary insights regarding the effects of a fraction of uninformative observations in a sample (such as careless responses), which is our primary objective.

Nevertheless, while our estimator is designed to be robust to partial misspecification caused by some uninformative responses, it can in some situations also provide a robustness gain under distributional misspecification. It turns out that if a nonnormal latent distribution differs from a normal distribution mostly in the tails, our estimator produces less biased estimates than ML because it can downweigh observations that are farther from the center.

To enhance accessibility and adoption by empirical researchers, an implementation of our proposed methodology in R (R Core Team, 2024) is freely available in the package robcat (for “ROBust CATegorical data analysis”; Welz et al., Reference Welz, Alfons and Mair2025) on CRAN (the Comprehensive R Archive Network) at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=robcat. Replication materials for all numerical results in this article are provided on GitHub at https://github.com/mwelz/robust-polycor-replication. Proofs, derivations, and additional simulations can be found in the Supplementary Material.

This article is structured as follows. We start with reviewing related literature (Section 2) followed by the polychoric correlation model and ML estimation thereof (Section 3). Afterward, we elaborate on the partial misspecification framework (Section 4) and introduce our robust generalized ML estimator, including its statistical properties (Section 5). These properties are then examined by a simulation study in which we vary the misspecification fraction systematically, and compare the result to the commonly employed standard ML estimator (Section 6). Subsequently, we demonstrate the practical usefulness in an empirical application on a Big Five administration (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1992) by Arias et al. (Reference Arias, Garrido, Jenaro, Martinez-Molina and Arias2020), where we find evidence of careless responding, manifesting in differences in polychoric correlation estimates of as much as 0.3 between our robust estimator and ML (Section 7). We then investigate the performance of the estimator under distributional misspecification (Section 8) and conclude with a discussion of the results and avenues for further research (Section 9).

2 Related literature

ML estimation of polychoric correlations was originally believed to be fairly robust to slight to moderate distributional misspecification (Coenders et al., Reference Coenders, Satorra and Saris1997; Flora & Curran, Reference Flora and Curran2004; Li, Reference Li2016; Maydeu-Olivares, Reference Maydeu-Olivares2006). This belief was based on simulations that generated data for nonnormal latent variables via the Vale–Maurelli (VM) method (Vale & Maurelli, Reference Vale and Maurelli1983), which were then discretized to ordinal data. However, Grønneberg & Foldnes (Reference Grønneberg and Foldnes2019) show that the distribution of ordinal data generated in this way is indistinguishable from that of ordinal data stemming from discretizing normally distributed latent variables.Footnote 1 In other words, simulation studies that ostensibly modeled nonnormality did in fact model normality. Simulating ordinal data in a way that ensures proper violations of latent normality (Grønneberg & Foldnes, Reference Grønneberg and Foldnes2017) reveals that polychoric correlation is in fact highly susceptible to distributional misspecification, resulting in possibly large biases (Foldnes & Grønneberg, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2020, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2022; Grønneberg & Foldnes, Reference Grønneberg and Foldnes2022; Jin & Yang-Wallentin, Reference Jin and Yang-Wallentin2017). Consequently, it is recommended to test for the validity of the latent normality assumption, for instance, by using the bootstrap test of Foldnes & Grønneberg (Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2020).

Another source of model misspecification occurs when the polychoric model is only misspecified for an uninformative subset of a sample (partial misspecification), where, in the context of this article, the term “uninformative” refers to an absence of relevant information for polychoric correlation, for instance, in careless responses. Careless responding “occurs when participants are not basing their response on the item content,” for instance, when a participant is “unmotivated to think about what the item is asking” (Ward & Meade, Reference Ward and Meade2023). It has been shown to be a major threat to the validity of research results through a variety of psychometric issues, such as reduced scale reliability (Arias et al., Reference Arias, Garrido, Jenaro, Martinez-Molina and Arias2020) and construct validity (Kam & Meyer, Reference Kam and Meyer2015), attenuated factor loadings, improper factor structure, and deteriorated model fit in factor analyses (Arias et al., Reference Arias, Garrido, Jenaro, Martinez-Molina and Arias2020; Huang, Bowling, et al., Reference Huang, Bowling, Liu and Li2015; Woods, Reference Woods2006), as well as inflated type I or type II errors in hypothesis testing (Arias et al., Reference Arias, Garrido, Jenaro, Martinez-Molina and Arias2020; Huang, Liu, et al., Reference Huang, Liu and Bowling2015; Maniaci & Rogge, Reference Maniaci and Rogge2014; McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Mitchell, Kim and Hough2010; Woods, Reference Woods2006). Careless responding is widely prevalent (Bowling et al., Reference Bowling, Huang, Bragg, Khazon, Liu and Blackmore2016; Meade & Craig, Reference Meade and Craig2012; Ward & Meade, Reference Ward and Meade2023) with most estimates on its prevalence ranging from 10% to 15% of study participants (Curran, Reference Curran2016; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Curran, Keeney, Poposki and DeShon2012; Huang, Liu, et al., Reference Huang, Liu and Bowling2015; Meade & Craig, Reference Meade and Craig2012), while already a prevalence 5%–10% can jeopardize the validity of research findings (Arias et al., Reference Arias, Garrido, Jenaro, Martinez-Molina and Arias2020; Credé, Reference Credé2010; Welz et al., Reference Welz, Archimbaud and Alfons2024; Woods, Reference Woods2006). In fact, Ward & Meade (Reference Ward and Meade2023) conjecture that careless responding is likely present in all survey data. However, to the best of our knowledge, the effects of careless responding on estimates of the polychoric model have not yet been studied.

Existing model-based approaches to account for careless responding in various models typically explicitly model carelessness through mixture models (e.g., Arias et al., Reference Arias, Garrido, Jenaro, Martinez-Molina and Arias2020; Steinmann et al., Reference Steinmann, Strietholt and Braeken2022; Ulitzsch, Pohl, et al., Reference Ulitzsch, Pohl, Khorramdel, Kroehne and von Davier2022; Ulitzsch, Yildirim-Erbasli, et al., Reference Ulitzsch, Yildirim-Erbasli, Gorgun and Bulut2022; Van Laar & Braeken, Reference Van Laar and Braeken2022). In contrast, our method does not model carelessness since we refrain from making assumptions on how the polychoric model might be misspecified. Another way to address careless responding is to directly detect them through person-fit indices and subsequently remove them from the sample (e.g., Patton et al., Reference Patton, Cheng, Hong and Diao2019). As a primary difference, our method simultaneously downweights aberrant observations during estimation rather than removing them. We refer to Alfons & Welz (Reference Alfons and Welz2024) for a detailed overview of methods addressing careless responding in various settings.

Conceptually related to our approach, Itaya & Hayashi (Reference Itaya and Hayashi2025) propose a way to robustly estimate parameters in item response theory (IRT) models. Their approach is conceptually similar to ours in the sense that it is based on minimizing a notion of divergence between an empirical density (from observed data) and a theoretical density of the IRT model. Like our approach, they achieve robustness by implicitly downweighting responses that the postulated model cannot fit well. Methodologically, our approach is different from Itaya & Hayashi (Reference Itaya and Hayashi2025) because our method is based on C-estimation (Welz, Reference Welz2024), which is designed specifically for categorical data, while they use density power divergence estimation (DPD) theory (Basu et al., Reference Basu, Harris, Hjort and Jones1998), which is not restricted to categorical data.Footnote 2 A relevant consequence is that our estimator is fully efficient, whereas DPD estimators lose efficiency as a price for gaining robustness. To the best of our knowledge, DPD estimators have not yet been studied for estimating polychoric correlation.

Another related branch of literature is that of outlier detection in contingency tables (see Sripriya et al. (Reference Sripriya, Gallo and Srinivasan2020) for a recent overview). In this literature, an outlier is a contingency table cell whose observed frequency is “markedly deviant” from those of the remaining cells (Sripriya et al., Reference Sripriya, Gallo and Srinivasan2020). This literature is agnostic with respect to the observed contingency table and therefore does not impose a parameterization on each cell’s probability. In contrast, the polychoric correlation model imposes such a parametrization through the assumption of latent bivariate normality. Another difference is that we are not primarily interested in outlier detection, but robust estimation of model parameters.

An alternative way to gain robustness against violations of latent nonnormality is to assume a different latent distribution, for instance, one with heavier tails. Examples from the SEM literature use elliptical distributions (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Bentler and Chan2004) or skew-elliptical distributions (Asparouhov & Muthén, Reference Asparouhov and Muthén2016), while Lyhagen & Ornstein (Reference Lyhagen and Ornstein2023), Jin & Yang-Wallentin (Reference Jin and Yang-Wallentin2017), and Roscino & Pollice (Reference Roscino, Pollice, Zani, Cerioli, Riani and Vichi2006) consider nonnormal distributions specifically in the context of polychoric correlation. Furthermore, it is worth pointing out that the term “robustness” is used in different ways in the methodological literature. Here, it refers to robustness against model misspecification. A popular but different meaning is robustness against heteroskedastic standard errors and corrected goodness-of-fit test statistics (e.g., Li, Reference Li2016; Satorra & Bentler, Reference Satorra, Bentler, Eye and Clogg1994, Reference Satorra and Bentler2001, and the references therein), which is, for instance, how the popular software package lavaan (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012) uses the term. We refer to Alfons & Schley (Reference Alfons and Schley2025) for an overview of the different meanings of “robustness” and a more detailed discussion.

3 Polychoric correlation

The polychoric correlation model (Pearson & Pearson, Reference Pearson and Pearson1922) models the association between two discrete ordinal variables by assuming that an observed pair of responses to two polytomous items is governed by an unobserved discretization process of latent variables that jointly follow a bivariate standard normal distribution. If both items are dichotomous, the polychoric correlation model reduces to the tetrachoric correlation model of Pearson (Reference Pearson1901). In the following, we first define the model and review ML estimation thereof and then introduce a robust estimator in the next section.

3.1 The polychoric model

For ease of exposition, we restrict our presentation to the bivariate polychoric model. The model naturally generalizes to higher dimensions (see, e.g., Muthén (Reference Muthén1984)).

Let there be two ordinal random variables, X and Y, that take values in the sets

![]() $\mathcal {X} = \{1,2,\dots ,K_X\}$

and

$\mathcal {X} = \{1,2,\dots ,K_X\}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {Y}=\{1,2,\dots ,K_Y\}$

, respectively. The assumption that the sets contain adjacent integers is without loss of generality. Suppose there exist two continuous latent random variables,

$\mathcal {Y}=\{1,2,\dots ,K_Y\}$

, respectively. The assumption that the sets contain adjacent integers is without loss of generality. Suppose there exist two continuous latent random variables,

![]() $\xi $

and

$\xi $

and

![]() $\eta $

, that govern the ordinal variables through the discretization model

$\eta $

, that govern the ordinal variables through the discretization model

$$ \begin{align} X= \begin{cases} 1 &\text{if } \xi < a_1,\\ 2 &\text{if } a_1 \leq \xi < a_2,\\ 3 &\text{if } a_2 \leq \xi < a_3,\\ \vdots\\ K_X &\text{if } a_{K_X-1} \leq \xi, \\ \end{cases} \qquad \text{ and } \qquad Y= \begin{cases} 1 &\text{if } \eta < b_1,\\ 2 &\text{if } b_1 \leq \eta < b_2,\\ 3 &\text{if } b_2 \leq \eta < b_3,\\ \vdots\\ K_Y &\text{if } b_{K_Y-1} \leq \eta, \\ \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} X= \begin{cases} 1 &\text{if } \xi < a_1,\\ 2 &\text{if } a_1 \leq \xi < a_2,\\ 3 &\text{if } a_2 \leq \xi < a_3,\\ \vdots\\ K_X &\text{if } a_{K_X-1} \leq \xi, \\ \end{cases} \qquad \text{ and } \qquad Y= \begin{cases} 1 &\text{if } \eta < b_1,\\ 2 &\text{if } b_1 \leq \eta < b_2,\\ 3 &\text{if } b_2 \leq \eta < b_3,\\ \vdots\\ K_Y &\text{if } b_{K_Y-1} \leq \eta, \\ \end{cases} \end{align} $$

where the fixed but unobserved parameters

![]() $a_1 < a_2 < \dots < a_{K_X-1}$

and

$a_1 < a_2 < \dots < a_{K_X-1}$

and

![]() $b_1 < b_2 < \dots < b_{K_Y-1}$

are called thresholds.

$b_1 < b_2 < \dots < b_{K_Y-1}$

are called thresholds.

The primary object of interest is the population correlation between the two latent variables. To identify this quantity from the ordinal variables

![]() $(X,Y)$

, one assumes that the continuous latent variables follow a standard bivariate normal distribution with unobserved pairwise correlation coefficient

$(X,Y)$

, one assumes that the continuous latent variables follow a standard bivariate normal distribution with unobserved pairwise correlation coefficient

![]() $\rho \in (-1,1)$

, that is,

$\rho \in (-1,1)$

, that is,

$$ \begin{align} \begin{pmatrix} \xi \\ \eta \end{pmatrix} \sim \text{N}_2 \left( \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} , \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \rho \\ \rho & 1 \end{pmatrix} \right). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{pmatrix} \xi \\ \eta \end{pmatrix} \sim \text{N}_2 \left( \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} , \begin{pmatrix} 1 & \rho \\ \rho & 1 \end{pmatrix} \right). \end{align} $$

Combining the discretization model (3.1) with the latent normality model (3.2) yields the polychoric model. In this model, one refers to the correlation parameter

![]() $\rho = \mathbb {C}\mathrm {or} \left [\xi ,\ \eta \right ]$

as the polychoric correlation coefficient of the ordinal X and Y. The polychoric model is subject to

$\rho = \mathbb {C}\mathrm {or} \left [\xi ,\ \eta \right ]$

as the polychoric correlation coefficient of the ordinal X and Y. The polychoric model is subject to

![]() $d=K_X+K_Y-1$

parameters, namely, the polychoric correlation coefficient from the latent normality model (3.2) and the two sets of thresholds from the discretization model (3.1). These parameters are jointly collected in a d-dimensional vector

$d=K_X+K_Y-1$

parameters, namely, the polychoric correlation coefficient from the latent normality model (3.2) and the two sets of thresholds from the discretization model (3.1). These parameters are jointly collected in a d-dimensional vector

Under the polychoric model, the probability of observing an ordinal response

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

at a parameter vector

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

at a parameter vector

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

is given by

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

is given by

$$ \begin{align} p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \mathbb{P}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} \left[ X = x, Y=y \right] = \int_{a_{x-1}}^{a_x}\int_{b_{y-1}}^{b_y} \phi_2\left(t,s; \rho \right)\text{d} s\ \text{d} t, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \mathbb{P}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} \left[ X = x, Y=y \right] = \int_{a_{x-1}}^{a_x}\int_{b_{y-1}}^{b_y} \phi_2\left(t,s; \rho \right)\text{d} s\ \text{d} t, \end{align} $$

where we use the conventions

![]() $a_0=b_0=-\infty , a_{K_X}=b_{K_Y}=+\infty $

, and

$a_0=b_0=-\infty , a_{K_X}=b_{K_Y}=+\infty $

, and

$$\begin{align*}\phi_2\left(u,v; \rho \right) = \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{1-\rho^2}} \exp\left( -\frac{u^2-2\rho uv + v^2}{2(1-\rho^2)} \right) \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\phi_2\left(u,v; \rho \right) = \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{1-\rho^2}} \exp\left( -\frac{u^2-2\rho uv + v^2}{2(1-\rho^2)} \right) \end{align*}$$

denotes the density of the standard bivariate normal distribution function with correlation parameter

![]() $\rho \in (-1,1)$

at some

$\rho \in (-1,1)$

at some

![]() $u,v\in \mathbb {R}$

, with corresponding distribution function

$u,v\in \mathbb {R}$

, with corresponding distribution function

Regarding identification, it is worth mentioning that in the case where both X and Y are dichotomous, the polychoric model is exactly identified by the standard bivariate normal distribution. If at least one of the ordinal variables has more than two response categories, the polychoric model is over-identified, so it could identify more parameters than those in

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

.Footnote

3

We refer to Olsson (Reference Olsson1979, Section 2) for a related discussion.

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

.Footnote

3

We refer to Olsson (Reference Olsson1979, Section 2) for a related discussion.

To distinguish arbitrary parameter values

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

from a specific value under which the polychoric model generates ordinal data, denote the latter by

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

from a specific value under which the polychoric model generates ordinal data, denote the latter by

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star} = \left (\rho _{\star}, a_{\star,1},\dots , a_{\star,K_X-1}, b_{\star,1}, \dots , b_{\star,K_Y-1}\right )^\top $

. Given a random sample of ordinal data generated by a polychoric model under parameter value

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star} = \left (\rho _{\star}, a_{\star,1},\dots , a_{\star,K_X-1}, b_{\star,1}, \dots , b_{\star,K_Y-1}\right )^\top $

. Given a random sample of ordinal data generated by a polychoric model under parameter value

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

, the statistical problem is to estimate the true

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

, the statistical problem is to estimate the true

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

, which is traditionally achieved by the ML estimator (MLE) of Olsson (Reference Olsson1979).Footnote

4

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

, which is traditionally achieved by the ML estimator (MLE) of Olsson (Reference Olsson1979).Footnote

4

3.2 Maximum likelihood estimation

Suppose we observe a sample

![]() $\{(X_i, Y_i)\}_{i=1}^N$

of N independent copies of

$\{(X_i, Y_i)\}_{i=1}^N$

of N independent copies of

![]() $(X,Y)$

generated by the polychoric model under the true parameter

$(X,Y)$

generated by the polychoric model under the true parameter

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

. The sample may be observed directly or as a

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

. The sample may be observed directly or as a

![]() $K_X\times K_Y$

contingency table that cross-tabulates the observed frequencies. Denote by

$K_X\times K_Y$

contingency table that cross-tabulates the observed frequencies. Denote by

the observed empirical frequency of a response

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

, where the indicator function

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

, where the indicator function ![]() takes value 1 if an event E is true, and 0 otherwise. The MLE of

takes value 1 if an event E is true, and 0 otherwise. The MLE of

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

can be expressed as

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

can be expressed as

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_N^{\mathrm{\ MLE}} = \arg\max_{\boldsymbol{\theta}\in\boldsymbol{\Theta}} \left\{ \sum_{x\in\mathcal{X}}\sum_{y\in\mathcal{Y}} N_{xy} \log\left(p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta})\right) \right\}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_N^{\mathrm{\ MLE}} = \arg\max_{\boldsymbol{\theta}\in\boldsymbol{\Theta}} \left\{ \sum_{x\in\mathcal{X}}\sum_{y\in\mathcal{Y}} N_{xy} \log\left(p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta})\right) \right\}, \end{align} $$

where the

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

are the response probabilities in (3.3), and

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

are the response probabilities in (3.3), and

$$ \begin{align} \boldsymbol{\Theta} = \bigg( \Big(\rho, \big(a_i\big)_{i=1}^{K_X-1}, \big(b_j\big)_{j=1}^{K_Y-1}\Big)^\top \ \Big|\ \rho\in(-1,1),\ a_1 < \dots < a_{K_X-1},\ b_1 < \dots < b_{K_Y-1} \bigg) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \boldsymbol{\Theta} = \bigg( \Big(\rho, \big(a_i\big)_{i=1}^{K_X-1}, \big(b_j\big)_{j=1}^{K_Y-1}\Big)^\top \ \Big|\ \rho\in(-1,1),\ a_1 < \dots < a_{K_X-1},\ b_1 < \dots < b_{K_Y-1} \bigg) \end{align} $$

is a set of parameters

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

that rules out degenerate cases, such as

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

that rules out degenerate cases, such as

![]() $\rho = \pm 1$

or thresholds that are not strictly monotonically increasing. This estimator, its computational details, as well as its statistical properties are derived in Olsson (Reference Olsson1979). In essence, if the polychoric model (3.1) is correctly specified—that is, the underlying latent variables

$\rho = \pm 1$

or thresholds that are not strictly monotonically increasing. This estimator, its computational details, as well as its statistical properties are derived in Olsson (Reference Olsson1979). In essence, if the polychoric model (3.1) is correctly specified—that is, the underlying latent variables

![]() $(\xi , \eta )$

are indeed standard bivariate normal—then the estimator

$(\xi , \eta )$

are indeed standard bivariate normal—then the estimator

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

is consistent for the true

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

is consistent for the true

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

. In addition,

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

. In addition,

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

is asymptotically normally distributed with mean zero and covariance matrix being equal to the model’s inverse Fisher information matrix, which makes it fully efficient.

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

is asymptotically normally distributed with mean zero and covariance matrix being equal to the model’s inverse Fisher information matrix, which makes it fully efficient.

As a computationally attractive alternative to estimating all parameters in

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

simultaneously in problem (3.4), one may consider a “2-step approach” where only the correlation coefficient

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

simultaneously in problem (3.4), one may consider a “2-step approach” where only the correlation coefficient

![]() $\rho _{\star}$

is estimated via ML, but not the thresholds. In this approach, one estimates in a first step the thresholds as quantiles of the univariate standard normal distribution, evaluated at the observed cumulative marginal proportion of each contingency table cell. Formally, in the 2-step approach, thresholds

$\rho _{\star}$

is estimated via ML, but not the thresholds. In this approach, one estimates in a first step the thresholds as quantiles of the univariate standard normal distribution, evaluated at the observed cumulative marginal proportion of each contingency table cell. Formally, in the 2-step approach, thresholds

![]() $a_{\star,x}$

and

$a_{\star,x}$

and

![]() $b_{\star,y}$

are, respectively, estimated via

$b_{\star,y}$

are, respectively, estimated via

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{a}_{x} = \Phi_1^{-1}\left( \frac{1}{N}\sum_{k=1}^x\sum_{y\in\mathcal{Y}} N_{ky} \right)\qquad\text{and}\qquad \widehat{b}_{y} = \Phi_1^{-1}\left( \frac{1}{N}\sum_{x\in\mathcal{X}}\sum_{l=1}^y N_{xl} \right), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \widehat{a}_{x} = \Phi_1^{-1}\left( \frac{1}{N}\sum_{k=1}^x\sum_{y\in\mathcal{Y}} N_{ky} \right)\qquad\text{and}\qquad \widehat{b}_{y} = \Phi_1^{-1}\left( \frac{1}{N}\sum_{x\in\mathcal{X}}\sum_{l=1}^y N_{xl} \right), \end{align} $$

for

![]() $x=1,\dots ,K_X-1$

and

$x=1,\dots ,K_X-1$

and

![]() $y=1,\dots ,K_Y-1$

, where

$y=1,\dots ,K_Y-1$

, where

![]() $\Phi _1^{-1}(\cdot )$

denotes the quantile function of the univariate standard normal distribution. Then, taking these threshold estimates as fixed in the polychoric model, one estimates in a second step the only remaining parameter, correlation coefficient

$\Phi _1^{-1}(\cdot )$

denotes the quantile function of the univariate standard normal distribution. Then, taking these threshold estimates as fixed in the polychoric model, one estimates in a second step the only remaining parameter, correlation coefficient

![]() $\rho _{\star}$

, via ML. The main advantage of the 2-step approach is reduced computational time, while it comes at the cost of being theoretically non-optimal because ML standard errors do not apply to the threshold estimators in (3.6) (Olsson, Reference Olsson1979). Using simulation studies, Olsson (Reference Olsson1979) finds that the two approaches tend to yield similar results in practice—both in terms of correlation and variance estimation—for small to moderate true correlations, while there can be small differences for larger true correlations.

$\rho _{\star}$

, via ML. The main advantage of the 2-step approach is reduced computational time, while it comes at the cost of being theoretically non-optimal because ML standard errors do not apply to the threshold estimators in (3.6) (Olsson, Reference Olsson1979). Using simulation studies, Olsson (Reference Olsson1979) finds that the two approaches tend to yield similar results in practice—both in terms of correlation and variance estimation—for small to moderate true correlations, while there can be small differences for larger true correlations.

Software implementations of polychoric correlation vary with respect to their estimation strategy. For instance, the popular R packages lavaan (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012) and psych (Revelle, Reference Revelle2024) only support the 2-step approach, while the package polycor (Fox, Reference Fox2022) supports both the 2-step approach and simultaneous estimation of all model parameters, with the former being the default. Our implementation of ML estimation in package robcat also supports both strategies.

4 Conceptualizing model misspecification

To study the effects of partial model misspecification from a theoretical perspective, we first rigorously define this concept and explain how it differs from distributional misspecification.

4.1 Partial misspecification of the polychoric model

The polychoric model is partially misspecified when not all unobserved realizations of the latent variables

![]() $(\xi ,\eta )$

come from a standard bivariate normal distribution. Specifically, we consider a situation where only a fraction

$(\xi ,\eta )$

come from a standard bivariate normal distribution. Specifically, we consider a situation where only a fraction

![]() $(1-\varepsilon )$

of those realizations are generated by a standard bivariate normal distribution with true correlation parameter

$(1-\varepsilon )$

of those realizations are generated by a standard bivariate normal distribution with true correlation parameter

![]() $\rho _{\star}$

, whereas a fixed but unknown fraction

$\rho _{\star}$

, whereas a fixed but unknown fraction

![]() $\varepsilon $

are generated by some different but unspecified distribution H. Note that H being unspecified allows its correlation coefficient to differ from

$\varepsilon $

are generated by some different but unspecified distribution H. Note that H being unspecified allows its correlation coefficient to differ from

![]() $\rho _{\star}$

so that realizations generated by H may be uninformative for the true polychoric correlation coefficient

$\rho _{\star}$

so that realizations generated by H may be uninformative for the true polychoric correlation coefficient

![]() $\rho _{\star}$

, such as, after discretization, careless responses, misresponses, or responses stemming from item misunderstanding.

$\rho _{\star}$

, such as, after discretization, careless responses, misresponses, or responses stemming from item misunderstanding.

Formally, we say that the polychoric model is partially misspecified if the latent variables

![]() $(\xi ,\eta )$

are jointly distributed according to

$(\xi ,\eta )$

are jointly distributed according to

for

![]() $u,v\in \mathbb {R}$

. Conceptualizing model misspecification in such a manner is standard in the robust statistics literature, going back to the seminal work of Huber (Reference Huber1964).Footnote

5

We therefore adopt terminology from robust statistics and call

$u,v\in \mathbb {R}$

. Conceptualizing model misspecification in such a manner is standard in the robust statistics literature, going back to the seminal work of Huber (Reference Huber1964).Footnote

5

We therefore adopt terminology from robust statistics and call

![]() $\varepsilon $

the contamination fraction, the uninformative H the contamination distribution (or simply contamination), and

$\varepsilon $

the contamination fraction, the uninformative H the contamination distribution (or simply contamination), and

![]() $G_\varepsilon $

the contaminated distribution. Observe that when the contamination fraction is zero, that is,

$G_\varepsilon $

the contaminated distribution. Observe that when the contamination fraction is zero, that is,

![]() $\varepsilon = 0$

, there is no misspecification so that the polychoric model is correctly specified for all observations. However, neither the contamination fraction

$\varepsilon = 0$

, there is no misspecification so that the polychoric model is correctly specified for all observations. However, neither the contamination fraction

![]() $\varepsilon $

nor the contamination distribution H is assumed to be known. Thus, both quantities are left completely unspecified in practice and

$\varepsilon $

nor the contamination distribution H is assumed to be known. Thus, both quantities are left completely unspecified in practice and

![]() $\Phi _2\left (u,v; \rho _{\star} \right )$

remains the distribution of interest. That is, we only aim to estimate the model parameters

$\Phi _2\left (u,v; \rho _{\star} \right )$

remains the distribution of interest. That is, we only aim to estimate the model parameters

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

of the polychoric model, while reducing the adverse effects of potential contamination in the observed ordinal data. The contaminated distribution

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

of the polychoric model, while reducing the adverse effects of potential contamination in the observed ordinal data. The contaminated distribution

![]() $G_\varepsilon $

, on the other hand, is never estimated. It serves as a purely theoretical construct that we use to study the theoretical properties of estimators of the polychoric model when that model is partially misspecified due to contamination.

$G_\varepsilon $

, on the other hand, is never estimated. It serves as a purely theoretical construct that we use to study the theoretical properties of estimators of the polychoric model when that model is partially misspecified due to contamination.

Leaving the contamination distribution H and contamination fraction

![]() $\varepsilon $

unspecified in the partial misspecification model (4.1) means that we are not making any assumptions on the degree, magnitude, or type of contamination (which is possibly absent altogether). Hence, in our context of responses to rating items, the polychoric model can be misspecified due to an unlimited variety of reasons, for instance, but not limited to careless/inattentive responding (e.g., straightlining, pattern responding, and random-like responding), misresponses, or item misunderstanding.

$\varepsilon $

unspecified in the partial misspecification model (4.1) means that we are not making any assumptions on the degree, magnitude, or type of contamination (which is possibly absent altogether). Hence, in our context of responses to rating items, the polychoric model can be misspecified due to an unlimited variety of reasons, for instance, but not limited to careless/inattentive responding (e.g., straightlining, pattern responding, and random-like responding), misresponses, or item misunderstanding.

Although we make no assumption on the specific value of the contamination fraction

![]() $\varepsilon $

in the partial misspecification model (4.1), we require the identification restriction

$\varepsilon $

in the partial misspecification model (4.1), we require the identification restriction

![]() $\varepsilon \in [0, 0.5)$

. That is, we require that the polychoric model is correctly specified for the majority of observations, which is standard in the robust statistics literature (e.g., Hampel et al., Reference Hampel, Ronchetti, Rousseeuw and Stahel1986, p. 67). While it is in principle possible to also consider a contamination fraction between

$\varepsilon \in [0, 0.5)$

. That is, we require that the polychoric model is correctly specified for the majority of observations, which is standard in the robust statistics literature (e.g., Hampel et al., Reference Hampel, Ronchetti, Rousseeuw and Stahel1986, p. 67). While it is in principle possible to also consider a contamination fraction between

![]() $0.5$

and

$0.5$

and

![]() $1$

, one would need to impose certain additional assumptions on the correct model to distinguish it from incorrect ones when the majority of observations are not generated by the correct model. Since we prefer refraining from imposing additional assumptions, we only consider

$1$

, one would need to impose certain additional assumptions on the correct model to distinguish it from incorrect ones when the majority of observations are not generated by the correct model. Since we prefer refraining from imposing additional assumptions, we only consider

![]() $\varepsilon \in [0, 0.5)$

. We discuss the link between identification and contamination fractions beyond 0.5 in more detail in Section E.1 of the Supplementary Material.

$\varepsilon \in [0, 0.5)$

. We discuss the link between identification and contamination fractions beyond 0.5 in more detail in Section E.1 of the Supplementary Material.

Furthermore, as another, more practical reason for considering

![]() $\varepsilon \in [0,0.5)$

, having more than half of all observations in a sample being not informative for the quantity of interest would be indicative of serious data quality issues. When data quality is unreasonably low, it is doubtful whether the data are suitable for modeling analyses in the first place.

$\varepsilon \in [0,0.5)$

, having more than half of all observations in a sample being not informative for the quantity of interest would be indicative of serious data quality issues. When data quality is unreasonably low, it is doubtful whether the data are suitable for modeling analyses in the first place.

4.2 Response probabilities under partial misspecification

Under contaminated distribution

![]() $G_\varepsilon $

with contamination fraction

$G_\varepsilon $

with contamination fraction

![]() $\varepsilon \in [0, 0.5)$

, the probability of observing an ordinal response

$\varepsilon \in [0, 0.5)$

, the probability of observing an ordinal response

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

is given by

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

is given by

$$ \begin{align} f_{\varepsilon} \left(x,y\right) = \mathbb{P}_{G_\varepsilon} \left[ X = x, Y=y \right] = (1-\varepsilon) p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta}_{\star}) + \varepsilon \int_{a_{\varepsilon,x-1}}^{a_{\varepsilon,x}} \int_{b_{\varepsilon,y-1}}^{b_{\varepsilon,y}} \text{d} H, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{\varepsilon} \left(x,y\right) = \mathbb{P}_{G_\varepsilon} \left[ X = x, Y=y \right] = (1-\varepsilon) p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta}_{\star}) + \varepsilon \int_{a_{\varepsilon,x-1}}^{a_{\varepsilon,x}} \int_{b_{\varepsilon,y-1}}^{b_{\varepsilon,y}} \text{d} H, \end{align} $$

where the unobserved thresholds

![]() $a_{\varepsilon ,x},b_{\varepsilon ,y}$

discretize the fraction

$a_{\varepsilon ,x},b_{\varepsilon ,y}$

discretize the fraction

![]() $\varepsilon $

of latent variables for which the polychoric model is misspecified. The thresholds

$\varepsilon $

of latent variables for which the polychoric model is misspecified. The thresholds

![]() $a_{\varepsilon ,x},b_{\varepsilon ,y}$

may be different from the true

$a_{\varepsilon ,x},b_{\varepsilon ,y}$

may be different from the true

![]() $a_{\star,x},b_{\star,y}$

and/or depend on contamination fraction

$a_{\star,x},b_{\star,y}$

and/or depend on contamination fraction

![]() $\varepsilon $

. However, it turns out that from a theoretical perspective, studying the case where the

$\varepsilon $

. However, it turns out that from a theoretical perspective, studying the case where the

![]() $a_{\varepsilon ,x},b_{\varepsilon ,y}$

are different from the

$a_{\varepsilon ,x},b_{\varepsilon ,y}$

are different from the

![]() $a_{\star,x},b_{\star,y}$

is equivalent to a case where they are equal.Footnote

6

$a_{\star,x},b_{\star,y}$

is equivalent to a case where they are equal.Footnote

6

The population response probabilities

![]() $f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right )$

in (4.2) are unknown in practice because they depend on unspecified and unmodeled quantities, namely, the contamination fraction

$f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right )$

in (4.2) are unknown in practice because they depend on unspecified and unmodeled quantities, namely, the contamination fraction

![]() $\varepsilon $

, the contamination distribution H, and the discretization thresholds of the latter. Consequently, we do not attempt to estimate the population response probabilities

$\varepsilon $

, the contamination distribution H, and the discretization thresholds of the latter. Consequently, we do not attempt to estimate the population response probabilities

![]() $f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right )$

. We instead focus on estimating the true polychoric model probabilities

$f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right )$

. We instead focus on estimating the true polychoric model probabilities

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

while reducing bias stemming from potential contamination in the observed data.

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

while reducing bias stemming from potential contamination in the observed data.

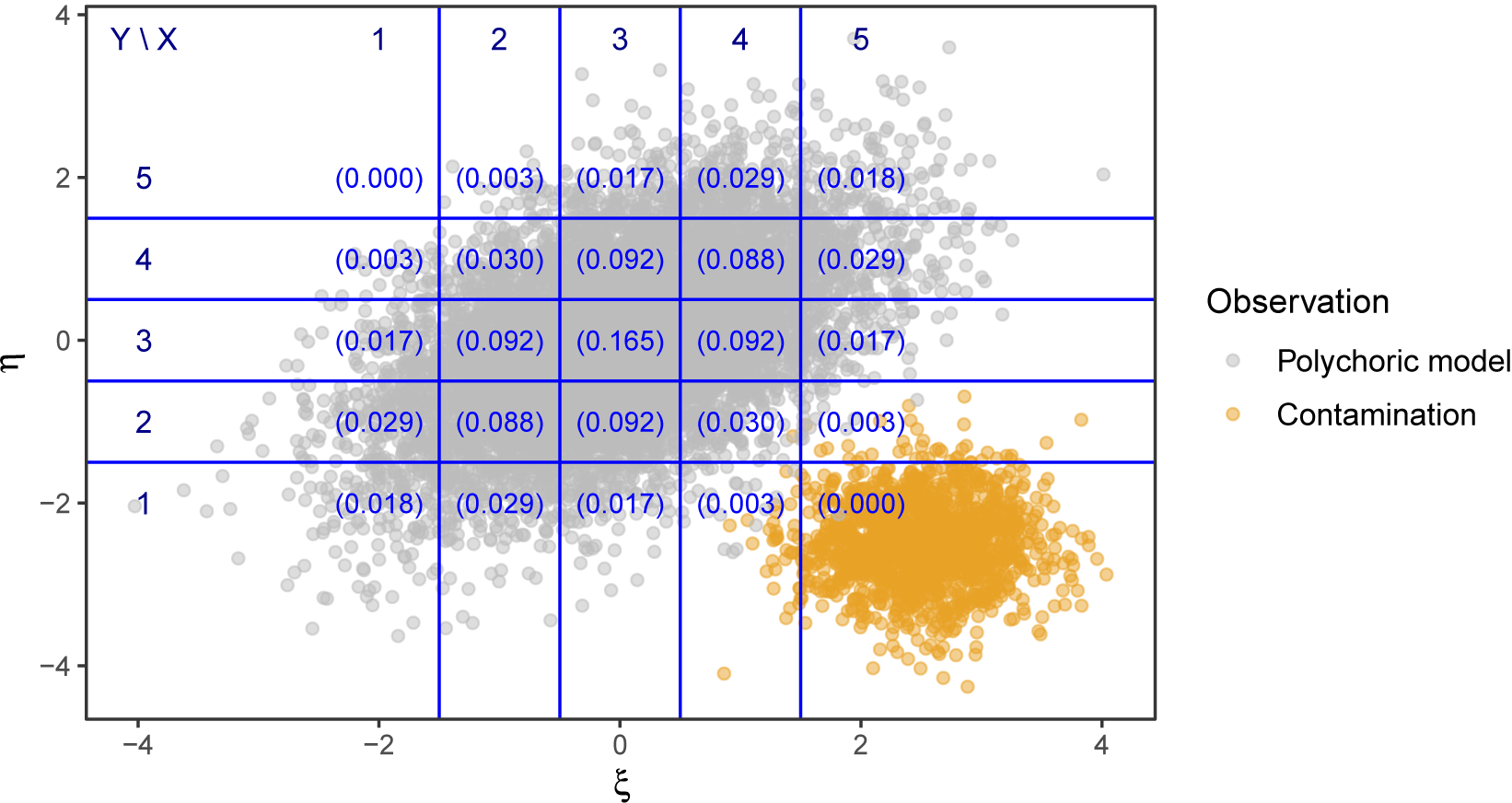

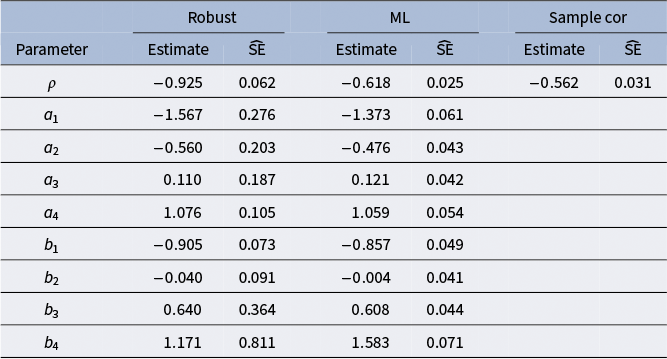

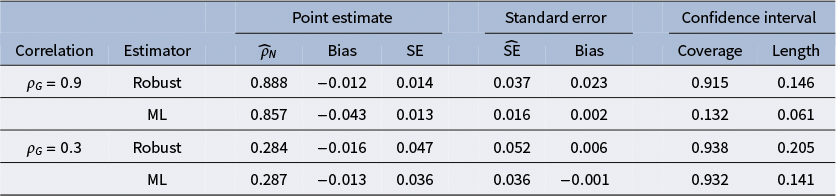

Figure 1 visualizes a simulated example of bivariate data drawn from contaminated distribution

![]() $G_\varepsilon $

, where a fraction of

$G_\varepsilon $

, where a fraction of

![]() $\varepsilon =0.15$

of the data follow a bivariate normal contamination distribution H (orange dots) with mean

$\varepsilon =0.15$

of the data follow a bivariate normal contamination distribution H (orange dots) with mean

![]() $(2.5, -2.5)^\top $

, variance

$(2.5, -2.5)^\top $

, variance

![]() $(0.25, 0.25)^\top $

, and zero correlation, whereas the remaining data are generated by a standard bivariate normal distribution with correlation

$(0.25, 0.25)^\top $

, and zero correlation, whereas the remaining data are generated by a standard bivariate normal distribution with correlation

![]() $\rho _{\star}=0.5$

(gray dots). In this example, the data from the contamination distribution H primarily inflate the cell

$\rho _{\star}=0.5$

(gray dots). In this example, the data from the contamination distribution H primarily inflate the cell

![]() $(x,y) = (5,1)$

after discretization. That is, this cell will have a larger empirical frequency than the polychoric model allows for, since the probability of this cell is nearly zero at the polychoric model, yet many realized responses will populate it. Consequently, due to (partial) misspecification of the polychoric model, an ML estimate of

$(x,y) = (5,1)$

after discretization. That is, this cell will have a larger empirical frequency than the polychoric model allows for, since the probability of this cell is nearly zero at the polychoric model, yet many realized responses will populate it. Consequently, due to (partial) misspecification of the polychoric model, an ML estimate of

![]() $\rho _{\star}$

on these data might be substantially biased for

$\rho _{\star}$

on these data might be substantially biased for

![]() $\rho _{\star}$

. Indeed, calculating the MLE using the data plotted in Figure 1 yields an estimate of

$\rho _{\star}$

. Indeed, calculating the MLE using the data plotted in Figure 1 yields an estimate of

![]() $\widehat {\rho }_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}=-0.10$

, which is far off from the true

$\widehat {\rho }_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}=-0.10$

, which is far off from the true

![]() $\rho _{\star}=0.5$

. In contrast, our proposed robust estimator, which is calculated from the exact same information as the MLE and is defined in Section 5, yields a fairly accurate estimate of

$\rho _{\star}=0.5$

. In contrast, our proposed robust estimator, which is calculated from the exact same information as the MLE and is defined in Section 5, yields a fairly accurate estimate of

![]() $0.47$

.

$0.47$

.

Figure 1 Simulated data with

![]() $K_X=K_Y=5$

response options where the polychoric model is misspecified with contamination fraction

$K_X=K_Y=5$

response options where the polychoric model is misspecified with contamination fraction

![]() $\varepsilon =0.15$

.

$\varepsilon =0.15$

.

Note: The gray dots represent random draws of

![]() $(\xi ,\eta )$

from the polychoric model with

$(\xi ,\eta )$

from the polychoric model with

![]() $\rho _{\star}=0.5$

, whereas the orange dots represent draws from a contamination distribution that primarily inflates the cell

$\rho _{\star}=0.5$

, whereas the orange dots represent draws from a contamination distribution that primarily inflates the cell

![]() $(x,y)=(5,1)$

. The contamination distribution is bivariate normal with a mean

$(x,y)=(5,1)$

. The contamination distribution is bivariate normal with a mean

![]() $(2.5,-2.5)^\top $

, variances

$(2.5,-2.5)^\top $

, variances

![]() $(0.25, 0.25)^\top $

, and zero correlation. The blue lines indicate the locations of the thresholds. In each cell, the numbers in parentheses denote the population probability of that cell under the true polychoric model.

$(0.25, 0.25)^\top $

, and zero correlation. The blue lines indicate the locations of the thresholds. In each cell, the numbers in parentheses denote the population probability of that cell under the true polychoric model.

It is worth addressing that there exist nonnormal distributions of the latent variables

![]() $(\xi ,\eta )$

that, after discretization with the same thresholds, result in the same response probabilities as under latent normality (Foldnes & Grønneberg, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2019). This implies that there may exist contamination distributions H and contamination fractions

$(\xi ,\eta )$

that, after discretization with the same thresholds, result in the same response probabilities as under latent normality (Foldnes & Grønneberg, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2019). This implies that there may exist contamination distributions H and contamination fractions

![]() $\varepsilon> 0$

under which the population probabilities

$\varepsilon> 0$

under which the population probabilities

![]() $f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right )$

in (4.2) are equal to the true population probabilities of the polychoric model,

$f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right )$

in (4.2) are equal to the true population probabilities of the polychoric model,

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

, that is,

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

, that is,

![]() $f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right ) = p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

for all

$f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right ) = p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

for all

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

. In this situation, the polychoric model is misspecified, but the misspecification does not have consequences because the response probabilities remain unaffected. To avoid cumbersome notation in the theoretical analysis of our robust estimator, we assume consequential misspecification throughout this article, that is,

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

. In this situation, the polychoric model is misspecified, but the misspecification does not have consequences because the response probabilities remain unaffected. To avoid cumbersome notation in the theoretical analysis of our robust estimator, we assume consequential misspecification throughout this article, that is,

![]() $f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right ) \neq p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

for some

$f_{\varepsilon } \left (x,y\right ) \neq p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

for some

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

whenever

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

whenever

![]() $\varepsilon> 0$

. However, it is silently understood that misspecification need not be consequential, in which case there is no issue and both the MLE and our robust estimator are consistent for the true

$\varepsilon> 0$

. However, it is silently understood that misspecification need not be consequential, in which case there is no issue and both the MLE and our robust estimator are consistent for the true

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

.

$\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star}$

.

4.3 Distributional misspecification

A model is distributionally misspecified when all observations in a given sample are generated by a distribution that is different from the model distribution. In the context of the polychoric model, this means that all ordinal observations are generated by a latent distribution that is nonnormal. Let G denote the unknown nonnormal distribution that the latent variables

![]() $(\xi , \eta )$

jointly follow under distributional misspecification. The object of interest is the population correlation between latent

$(\xi , \eta )$

jointly follow under distributional misspecification. The object of interest is the population correlation between latent

![]() $\xi $

and

$\xi $

and

![]() $\eta $

under distribution G, for which the normality-based MLE of Olsson (Reference Olsson1979) turns out to be substantially biased in many cases (e.g., Foldnes & Grønneberg, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2020, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2022; Jin & Yang-Wallentin, Reference Jin and Yang-Wallentin2017; Lyhagen & Ornstein, Reference Lyhagen and Ornstein2023). As such, distributional misspecification is fundamentally different from partial misspecification: In the former, one attempts to estimate the population correlation of the nonnormal and unknown distribution that generated a sample, instead of estimating the polychoric correlation coefficient (which is the correlation under standard bivariate normality). In the latter, one attempts to estimate the polychoric correlation coefficient with a contaminated sample that has only been partly generated by latent normality (that is, the polychoric model). The assumption that the polychoric model is only partially misspecified for some uninformative observations enables one to still estimate the polychoric correlation coefficient of that model, which would not be feasible under distributional misspecification (at least not without additional assumptions).

$\eta $

under distribution G, for which the normality-based MLE of Olsson (Reference Olsson1979) turns out to be substantially biased in many cases (e.g., Foldnes & Grønneberg, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2020, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2022; Jin & Yang-Wallentin, Reference Jin and Yang-Wallentin2017; Lyhagen & Ornstein, Reference Lyhagen and Ornstein2023). As such, distributional misspecification is fundamentally different from partial misspecification: In the former, one attempts to estimate the population correlation of the nonnormal and unknown distribution that generated a sample, instead of estimating the polychoric correlation coefficient (which is the correlation under standard bivariate normality). In the latter, one attempts to estimate the polychoric correlation coefficient with a contaminated sample that has only been partly generated by latent normality (that is, the polychoric model). The assumption that the polychoric model is only partially misspecified for some uninformative observations enables one to still estimate the polychoric correlation coefficient of that model, which would not be feasible under distributional misspecification (at least not without additional assumptions).

Despite not being designed for distributional misspecification, the robust estimator introduced in the next section can offer a robustness gain in some situations where the polychoric model is distributionally misspecified. We discuss this in more detail in Section 8.

5 Robust estimation of polychoric correlation

The behavior of ML estimates of any model crucially depends on the correct specification of that model. Indeed, ML estimation can be severely biased even when the assumed model is only slightly misspecified (e.g., Hampel et al., Reference Hampel, Ronchetti, Rousseeuw and Stahel1986; Huber, Reference Huber1964; Huber & Ronchetti, Reference Huber and Ronchetti2009). For instance, in many models of continuous variables like regression models, one single observation from a different distribution can be enough to make the ML estimator converge to an arbitrary value (Huber & Ronchetti, Reference Huber and Ronchetti2009; see also Alfons et al. (Reference Alfons, Ateş and Groenen2022) for the special case of mediation analysis). The non-robustness of ML estimation of the polychoric model has been demonstrated empirically by Foldnes & Grønneberg (Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2020, Reference Foldnes and Grønneberg2022) and Grønneberg & Foldnes (Reference Grønneberg and Foldnes2022) for the case of distributional misspecification. In this section, we introduce an estimator that is designed to be robust to partial misspecification when present, but remains (asymptotically) equivalent to the ML estimator of Olsson (Reference Olsson1979) when misspecification is absent. We furthermore derive the statistical properties of the proposed estimator.

Throughout this section, let

![]() $\{(X_i, Y_i)\}_{i=1}^N$

be an observed ordinal sample of size N generated by discretizing latent variables

$\{(X_i, Y_i)\}_{i=1}^N$

be an observed ordinal sample of size N generated by discretizing latent variables

![]() $(\xi ,\eta )$

that follow the unknown and unspecified contaminated distribution

$(\xi ,\eta )$

that follow the unknown and unspecified contaminated distribution

![]() $G_\varepsilon $

in (4.1). Hence, the polychoric model is possibly misspecified for an unknown fraction

$G_\varepsilon $

in (4.1). Hence, the polychoric model is possibly misspecified for an unknown fraction

![]() $\varepsilon $

of the sample.

$\varepsilon $

of the sample.

5.1 The estimator

The proposed estimator is a special case of a class of robust estimators for general models of categorical data called C-estimators (Welz, Reference Welz2024), and is based on the following idea. The empirical relative frequency of a response

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

, denoted

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

, denoted

is a consistent nonparametric estimator of the population response probability in (4.2),

$$\begin{align*}f_{\varepsilon} \left(x,y\right) = \mathbb{P}_{G_\varepsilon} \left[ X = x, Y=y \right] = (1-\varepsilon) p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta}_{\star}) + \varepsilon \int_{a_{\varepsilon,x-1}}^{a_{\varepsilon,x}} \int_{b_{\varepsilon,y-1}}^{b_{\varepsilon,y}} \text{d} H, \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}f_{\varepsilon} \left(x,y\right) = \mathbb{P}_{G_\varepsilon} \left[ X = x, Y=y \right] = (1-\varepsilon) p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta}_{\star}) + \varepsilon \int_{a_{\varepsilon,x-1}}^{a_{\varepsilon,x}} \int_{b_{\varepsilon,y-1}}^{b_{\varepsilon,y}} \text{d} H, \end{align*}$$

as

![]() $N\to \infty $

(see, e.g., Chapter 19.2 in Van der Vaart (Reference Van der Vaart1998)). If the polychoric model is correctly specified

$N\to \infty $

(see, e.g., Chapter 19.2 in Van der Vaart (Reference Van der Vaart1998)). If the polychoric model is correctly specified

![]() $(\varepsilon = 0)$

, then

$(\varepsilon = 0)$

, then

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

will converge (in probability) to the true model probability

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

will converge (in probability) to the true model probability

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

because

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

because

for all

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

. Conversely, if the polychoric model is misspecified

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

. Conversely, if the polychoric model is misspecified

![]() $(\varepsilon> 0)$

, then

$(\varepsilon> 0)$

, then

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

may not converge to the true

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

may not converge to the true

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

because

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

because

for some

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

, since we assume consequential misspecification.

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

, since we assume consequential misspecification.

It follows that if the polychoric model is misspecified, there exists no parameter value

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }\in \boldsymbol {\Theta }$

for which the nonparametric estimates

$\boldsymbol {\theta }\in \boldsymbol {\Theta }$

for which the nonparametric estimates

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

converge pointwise to the associated model probabilities

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

converge pointwise to the associated model probabilities

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

for all

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

for all

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

. Hence, it is indicative of model misspecification if there exists at least one response

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

. Hence, it is indicative of model misspecification if there exists at least one response

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

for which

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

for which

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

does not converge to any polychoric model probability

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

does not converge to any polychoric model probability

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

, resulting in a discrepancy between

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

, resulting in a discrepancy between

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

and

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

and

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

.Footnote

7

This observation can be exploited in model fitting by minimizing the discrepancy between the empirical relative frequencies,

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

.Footnote

7

This observation can be exploited in model fitting by minimizing the discrepancy between the empirical relative frequencies,

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

, and theoretical model probabilities,

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

, and theoretical model probabilities,

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

, to find the most accurate fit that can be achieved with the polychoric model for the observed data. Specifically, our estimator minimizes with respect to

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

, to find the most accurate fit that can be achieved with the polychoric model for the observed data. Specifically, our estimator minimizes with respect to

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

the loss function

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

the loss function

$$ \begin{align} L\left( \boldsymbol{\theta},\ \widehat{f}_{N} \right) = \sum_{x\in\mathcal{X}}\sum_{y\in\mathcal{Y}} \varphi\left(\frac{\widehat{f}_{N}(x,y)}{p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}-1\right)p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta}), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} L\left( \boldsymbol{\theta},\ \widehat{f}_{N} \right) = \sum_{x\in\mathcal{X}}\sum_{y\in\mathcal{Y}} \varphi\left(\frac{\widehat{f}_{N}(x,y)}{p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta})}-1\right)p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta}), \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\varphi : [-1,\infty ) \to \mathbb {R}$

is a prespecified discrepancy function that will be defined momentarily. The proposed estimator

$\varphi : [-1,\infty ) \to \mathbb {R}$

is a prespecified discrepancy function that will be defined momentarily. The proposed estimator

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

is given by the value minimizing the objective loss over parameter space

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

is given by the value minimizing the objective loss over parameter space

![]() $\boldsymbol {\Theta }$

,

$\boldsymbol {\Theta }$

,

For the choice of discrepancy function

![]() $\varphi (z) = \varphi ^{\mathrm {MLE}}(z) = (z+1) \log (z+1)$

, it can be easily verified that

$\varphi (z) = \varphi ^{\mathrm {MLE}}(z) = (z+1) \log (z+1)$

, it can be easily verified that

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

coincides with the MLE

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

coincides with the MLE

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

in (3.4). In the following, we motivate a specific choice of discrepancy function

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

in (3.4). In the following, we motivate a specific choice of discrepancy function

![]() $\varphi (\cdot )$

that makes the estimator

$\varphi (\cdot )$

that makes the estimator

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

less susceptible to misspecification of the polychoric model while preserving equivalence with ML estimation in the absence of misspecification.

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

less susceptible to misspecification of the polychoric model while preserving equivalence with ML estimation in the absence of misspecification.

The fraction between empirical relative frequencies and model probabilities with value 1 deducted,

$$\begin{align*}\frac{\widehat{f}_{N}(x,y)}{p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta})} -1, \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\frac{\widehat{f}_{N}(x,y)}{p_{xy}(\boldsymbol{\theta})} -1, \end{align*}$$

is referred to as Pearson residual (PR) (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay1994). It takes values in

![]() $[-1,+\infty )$

and can be interpreted as a goodness-of-fit measure. PR values close to 0 indicate a good fit between data and polychoric model at

$[-1,+\infty )$

and can be interpreted as a goodness-of-fit measure. PR values close to 0 indicate a good fit between data and polychoric model at

![]() $\boldsymbol {\theta }$

, whereas values toward

$\boldsymbol {\theta }$

, whereas values toward

![]() $-1$

or

$-1$

or

![]() $+\infty $

indicate a poor fit because empirical response probabilities disagree with their model counterparts. To achieve robustness to misspecification of the polychoric model, responses that cannot be modeled well by the polychoric model, as indicated by their PR being away from 0, should receive less weight in the estimation procedure such that they do not over-proportionally affect the fit. Downweighting when necessary is achieved through a specific choice of discrepancy function

$+\infty $

indicate a poor fit because empirical response probabilities disagree with their model counterparts. To achieve robustness to misspecification of the polychoric model, responses that cannot be modeled well by the polychoric model, as indicated by their PR being away from 0, should receive less weight in the estimation procedure such that they do not over-proportionally affect the fit. Downweighting when necessary is achieved through a specific choice of discrepancy function

![]() $\varphi (\cdot )$

proposed by Welz et al. (Reference Welz, Archimbaud and Alfons2024), which is a special case of a function suggested by Ruckstuhl & Welsh (Reference Ruckstuhl and Welsh2001). The discrepancy function reads

$\varphi (\cdot )$

proposed by Welz et al. (Reference Welz, Archimbaud and Alfons2024), which is a special case of a function suggested by Ruckstuhl & Welsh (Reference Ruckstuhl and Welsh2001). The discrepancy function reads

$$ \begin{align} \varphi(z) = \begin{cases} (z+1) \log(z+1) &\text{ if } z \in [-1, c],\\ (z+1)(\log(c+1) + 1) - c-1&\text{ if } z> c, \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \varphi(z) = \begin{cases} (z+1) \log(z+1) &\text{ if } z \in [-1, c],\\ (z+1)(\log(c+1) + 1) - c-1&\text{ if } z> c, \end{cases} \end{align} $$

where

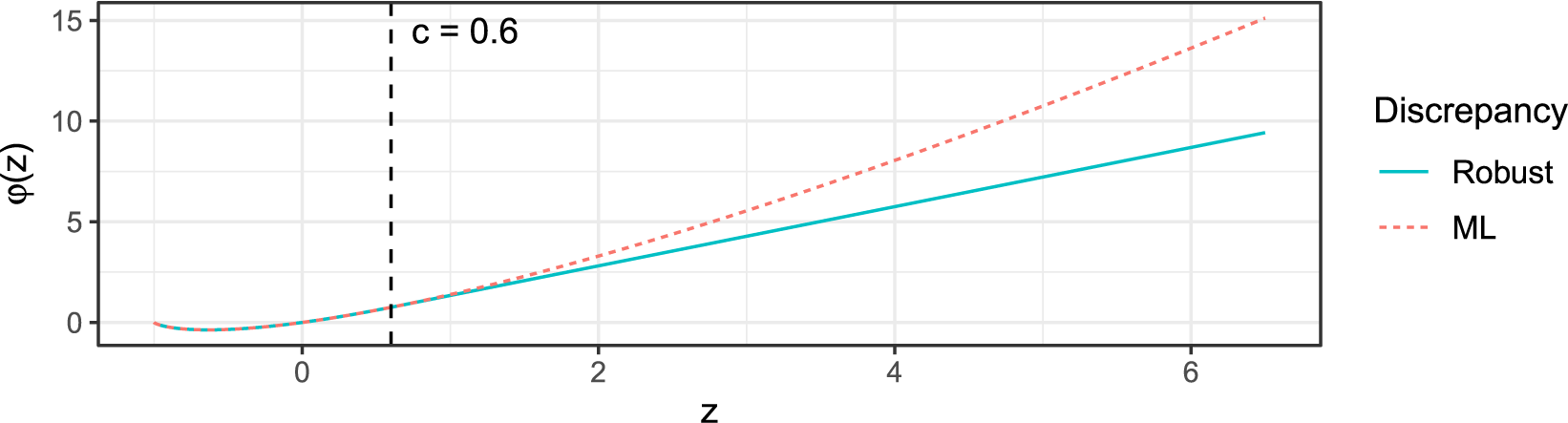

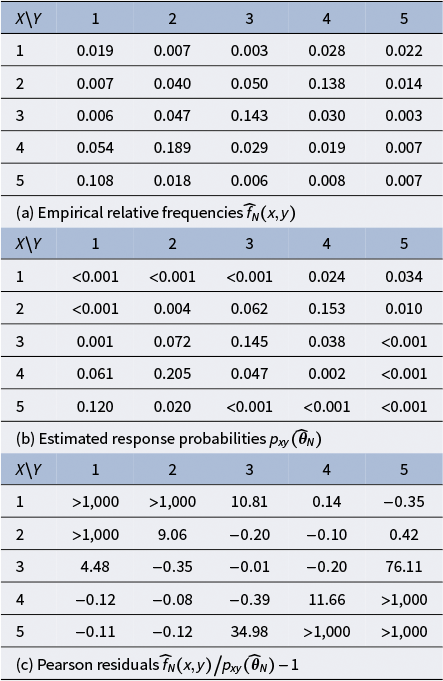

![]() $c\in [0,\infty ]$

is a prespecified tuning constant that governs the estimator’s behavior at the PR of each possible response. Figure 2 visualizes this function for the example choice

$c\in [0,\infty ]$

is a prespecified tuning constant that governs the estimator’s behavior at the PR of each possible response. Figure 2 visualizes this function for the example choice

![]() $c=0.6$

as well as the ML discrepancy function

$c=0.6$

as well as the ML discrepancy function

![]() $\varphi ^{\mathrm {MLE}}(z) = (z+1) \log (z+1)$

. Note that deducting 1 in (5.1) and adding it again in (5.3) is purely for keeping the interpretation that a PR close to 0 indicates a good fit. We further stress that although the discrepancy function (5.3) can be negative, the loss function (5.1) is always nonnegative (Welz, Reference Welz2024).

$\varphi ^{\mathrm {MLE}}(z) = (z+1) \log (z+1)$

. Note that deducting 1 in (5.1) and adding it again in (5.3) is purely for keeping the interpretation that a PR close to 0 indicates a good fit. We further stress that although the discrepancy function (5.3) can be negative, the loss function (5.1) is always nonnegative (Welz, Reference Welz2024).

Figure 2 Visualization of the robust discrepancy function

![]() $\varphi (z)$

in (5.3) for

$\varphi (z)$

in (5.3) for

![]() $c = 0.6$

(solid line) and the ML discrepancy function

$c = 0.6$

(solid line) and the ML discrepancy function

![]() $\varphi ^{\mathrm {MLE}}(z) = (z+1) \log (z+1)$

(dotted line).

$\varphi ^{\mathrm {MLE}}(z) = (z+1) \log (z+1)$

(dotted line).

For the choice

![]() $c=+\infty $

, minimizing the loss (5.1) is equivalent to maximizing the log-likelihood objective in (3.4), meaning that the estimator

$c=+\infty $

, minimizing the loss (5.1) is equivalent to maximizing the log-likelihood objective in (3.4), meaning that the estimator

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

is equal to

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

is equal to

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

for this choice of c. More specifically, if a PR

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

for this choice of c. More specifically, if a PR

![]() $z = \frac {\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)}{p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })}-1$

of a response

$z = \frac {\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)}{p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })}-1$

of a response

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

is such that

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

is such that

![]() $z\in [-1, c]$

for fixed

$z\in [-1, c]$

for fixed

![]() $c\geq 0$

, then the estimation procedure behaves at this response like in classic ML estimation. As argued before, in the absence of misspecification,

$c\geq 0$

, then the estimation procedure behaves at this response like in classic ML estimation. As argued before, in the absence of misspecification,

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

converges to

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

converges to

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

for all responses

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta }_{\star})$

for all responses

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

, therefore, all PRs are asymptotically equal to 0. Hence, if the polychoric model is correctly specified, then estimator

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

, therefore, all PRs are asymptotically equal to 0. Hence, if the polychoric model is correctly specified, then estimator

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

is asymptotically equivalent to the MLE

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

is asymptotically equivalent to the MLE

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

for any tuning constant value

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N^{\mathrm {\ MLE}}$

for any tuning constant value

![]() $c \geq 0$

. On the other hand, if a response’s PR z is larger than c, that is,

$c \geq 0$

. On the other hand, if a response’s PR z is larger than c, that is,

![]() $z> c \geq 0$

, then the estimation procedure does not behave like in ML, but the response’s contribution to loss (5.1) is linear rather than super-linear like in ML (Figure 2). It follows that the influence of responses that cannot be fitted well by the polychoric model is downweighted to prevent them from dominating the fit. The tuning constant

$z> c \geq 0$

, then the estimation procedure does not behave like in ML, but the response’s contribution to loss (5.1) is linear rather than super-linear like in ML (Figure 2). It follows that the influence of responses that cannot be fitted well by the polychoric model is downweighted to prevent them from dominating the fit. The tuning constant

![]() $c\geq 0$

is the threshold beyond which a PR will be downweighted, so the choice thereof determines what is considered an insufficient fit. The closer to 0 the tuning constant c is chosen, the more robust the estimator is in theory. In Section C of the Supplementary Material, we explore different values of c in simulations and motivate a specific choice that we use for all numerical results in this article, namely,

$c\geq 0$

is the threshold beyond which a PR will be downweighted, so the choice thereof determines what is considered an insufficient fit. The closer to 0 the tuning constant c is chosen, the more robust the estimator is in theory. In Section C of the Supplementary Material, we explore different values of c in simulations and motivate a specific choice that we use for all numerical results in this article, namely,

![]() $c=0.6$

.

$c=0.6$

.

Note that the discrepancy function

![]() $\varphi (\cdot )$

in (5.3) may only downweight overcounts, that is, the empirical probability

$\varphi (\cdot )$

in (5.3) may only downweight overcounts, that is, the empirical probability

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

exceeding the theoretical probability

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

exceeding the theoretical probability

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

for some cell

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

for some cell

![]() $(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

. One might wonder why undercounts—

$(x,y)\in \mathcal {X}\times \mathcal {Y}$

. One might wonder why undercounts—

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

being smaller than

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

being smaller than

![]() $p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

, resulting in negative PRs—are not downweighted as well. Indeed, the discrepancy function in (5.3) does not change its behavior compared to the MLE for PRs below 0. The empirical frequency

$p_{xy}(\boldsymbol {\theta })$

, resulting in negative PRs—are not downweighted as well. Indeed, the discrepancy function in (5.3) does not change its behavior compared to the MLE for PRs below 0. The empirical frequency

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

is a relative measure, so if a contingency table cell

$\widehat {f}_{N}(x,y)$

is a relative measure, so if a contingency table cell

![]() $(x,y)$

has inflated counts, the other cells will have reduced values of

$(x,y)$

has inflated counts, the other cells will have reduced values of

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}$

. If the discrepancy function would downweight undercounts, there is a risk of downweighting non-contaminated cells simply because these cells have reduced

$\widehat {f}_{N}$

. If the discrepancy function would downweight undercounts, there is a risk of downweighting non-contaminated cells simply because these cells have reduced

![]() $\widehat {f}_{N}$

values if at least one cell is inflated due to contamination. Such behavior could result in bias since non-contaminated cells are not supposed to be downweighted. We refer to Ruckstuhl and Welsh (Reference Ruckstuhl and Welsh2001, p. 1128) for a related discussion.

$\widehat {f}_{N}$

values if at least one cell is inflated due to contamination. Such behavior could result in bias since non-contaminated cells are not supposed to be downweighted. We refer to Ruckstuhl and Welsh (Reference Ruckstuhl and Welsh2001, p. 1128) for a related discussion.

With the proposed choice of

![]() $\varphi (\cdot )$

, we stress that our estimator

$\varphi (\cdot )$

, we stress that our estimator

![]() $\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

in (5.2) has the same time complexity as ML, namely,

$\widehat {\boldsymbol {\theta }}_N$

in (5.2) has the same time complexity as ML, namely,

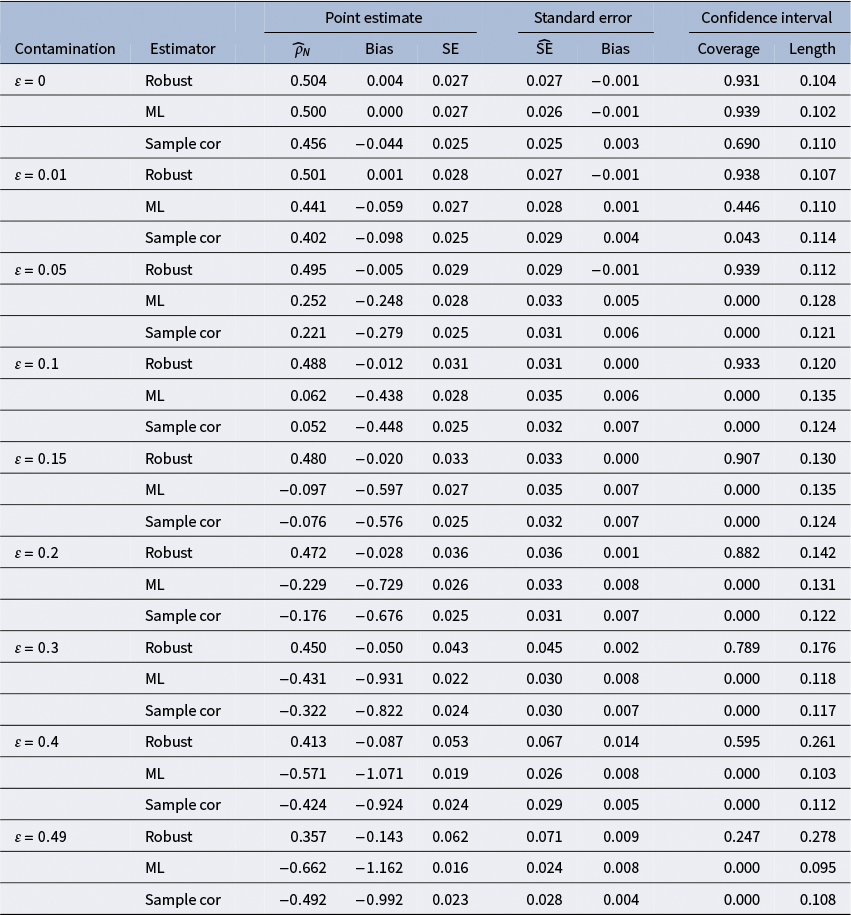

![]() $O\big (K_X\cdot K_Y\big )$