1 Introduction

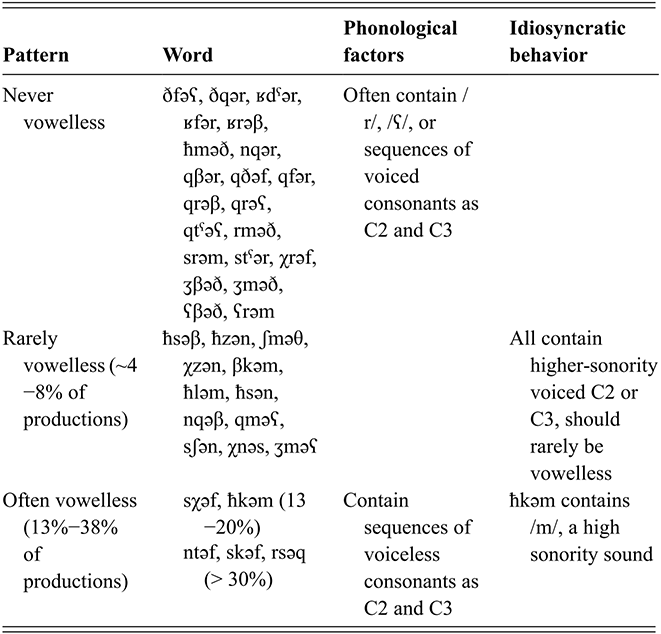

Tarifit is an Amazigh language spoken in northern Morocco. Tarifit is also known as Tarifiyt or Riffian, and many Tarifit speakers refer to their language as /θarifəʃt/ or Tamazight, though the latter term is used to refer to other Amazigh varieties as well. The term /θarifəʃt/ (or Irifiyen for the people who speak it) can also refer to the specific group of people in the region (we will give more details in what follows).

Amazigh languages are indigenous to North Africa. The Amazigh language group (also known as Berber) is one branch of the Afro-Asiatic language phylum and consists of many extant languages spoken in a large, but discontinuous area ranging from the Atlantic coast to western Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger river (Mourigh & Kossmann, Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019). The history of the Amazigh languages dates back to at least the second millennium BCE (Camps, Reference Camps1995). The word Berber derives from the Greek word Barbaroi (barbarian), a name that was used to refer to anyone who did not speak Greek. Because this term can be derogatory, Amazigh people prefer to be referred to as Amazigh (plural: Imazighen), meaning ‘free’ and ‘noble’ (Zouhir, Reference Zouhir, Orie and Sanders2013).

Amazigh languages share many basic grammatical structures, and much of their basic vocabulary, but there is also a huge amount of variation. In some ways, the Amazigh language family can be described as a dialect continuum, since there is gradient variation within regions over space. Lafkioui (Reference Lafkioui2018) suggests three major subdivisions of Amazigh varieties, though classifications are often problematic (Mourigh & Kossmann, Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019). The first is Northern Amazigh, which consists of Tarifit (including Senhaja Berber; north, northeast, and northwest Morocco), Tamazight (spoken in the Middle Atlas / central Moroccan region), Figuig Berber (east Morocco), Kabyle Berber (north Algeria), Tashawit (Aures, northeast Algeria), Mzab Berber (south Algeria), and Ouargla Berber (south Algeria). The second group is Southern Berber, which consists of languages such as Zenaga (spoken in Mauritania), Tashlhiyt (south Morocco), and Tetserret and Tuareg Berber (Sahara, Sahel). Eastern Berber is the third group, which includes languages such as Siwa (west Egypt), Sokna and El-Fogaha (Fezzan, central Libya), Yefren and Zuara (Tripolitania, north Libya), and Ghadames (east Libya), as well as all of the Amazigh languages of Tunisia (Jerba, Tamazret, and Sened).

Compared to other North African countries, Morocco contains the largest proportion of the population that speaks an Amazigh language as a mother tongue; the latest official census data (Reference Census2024) reports that around 25% of the total population of about forty million Moroccans speak an Amazigh language. The true number is probably larger; for instance, Mourigh and Kossmann (Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019) suggest that a quarter to a third of the population speak Amazigh, Ethnologue (Eberhard et al., Reference Eberhard, Simons and Fennig2025) states that there were thirteen million speakers between 2016 and 2017, and Belhiah et al. (Reference Belhiah, Majdoubi and Safwate2020) say that the proportion is closer to 30%.

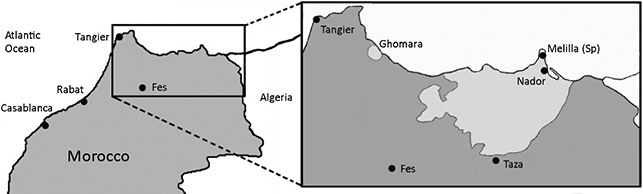

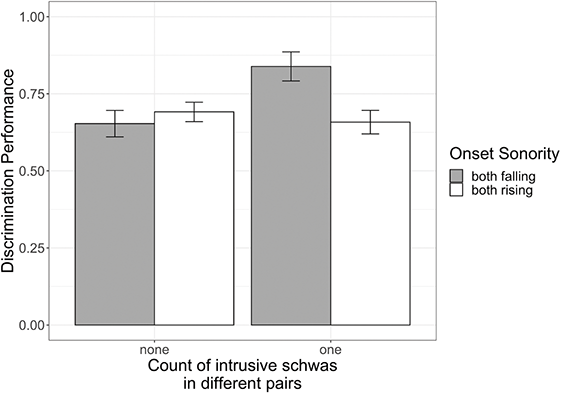

Tarifit is one of three largest Moroccan Amazigh languages, along with Tashlhiyt and Tamazight. There are approximately one million Tarifit speakers living in rural and urban regions in northeast Morocco (Census, Reference Census2024), while Tashlhiyt has the largest number of speakers (about five million), followed by Tamazight (about three million). Figure 1 shows the area of Morocco where Tarifit is spoken. Tarifit is spoken in a northern Moroccan region known as the “Rif,” which is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Algeria to the east, and the Middle Atlas mountain range to the south. The Rif language area comprises two predominantly Amazigh-speaking areas: the small geolinguistic enclave of Ghomara and the larger territory bordered to the west by Ktama, to the east by the Iznasen (near the Algerian border), and to the south by Guercif, the last Riffian geographic point before the Taza corridor (Lafkioui, Reference Lafkioui2017). Tarifit can be subdivided into two major dialect groups: Western and Eastern varieties (Lafkioui, Reference Lafkioui2024). The Western dialects are spoken in and around El Hoceima. The Eastern dialects are spoken in and around Nador. The major Eastern subvariety known as Guelaiya is the focus of the current Element. In addition to being spoken in Morocco, a large Tarifit-speaking diaspora community lives in Belgium, the Netherlands, and other parts of Europe, and Lafkioui (Reference Lafkioui2024) estimates that there are around six million Tarifit speakers in the diaspora.

Figure 1 Map of northern Morocco, inset showing Tarifit speaking regions, including Nador.

Multilingualism is high among Tarifit speakers. Tarifit speakers in Morocco generally learn Tarifit as their first language and use it primarily in the home and with other Tarifit-speaking community members. Tarifit speakers usually learn Moroccan Arabic at a young age, when they interact with non-Amazigh-speaking community members and in school, where Classical/Standard Arabic is learned and used in formal settings. Spanish and/or French may also be acquired for various reasons. French is learned at a young age in schools across the country, while Spanish is learned due to the Spanish presence in this part of the country (1912–1956). Moreover, Spanish is the official language of the enclave of Melilla, about fourteen kilometers from Nador, and there are many Spanish loanwords in the language. Tarifit speakers outside of Morocco use other languages in community, educational, or professional settings, such as French, Spanish, Dutch, English, or German.

Amazigh has been in contact with various dialects of Arabic since the seventh century when the Arab conquest of North Africa spread to Morocco. Arab settlements in the country introduced Arabic, and Arabs in the region also utilized local varieties of Amazigh primarily for informal communication with Amazigh families (Zakhir, Reference Zakhir2023). Yet, Arabic became the dominant language in the region and Amazigh languages were marginalized (El Guabli, Reference El Guabli2025). French occupation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries also led to the rise of Arabic-French bilingualism in the region, and there was debate on the use and status of Amazigh in schools. The French administration launched “the Berber decree of 1914” to encourage its teaching and established the first Amazigh School in Azrou in 1927 (Reino, Reference Reino2007). After Moroccan independence from France in 1956, Amazigh languages continued to suffer marginalization due to the “Arabization” process in Morocco and throughout the Maghreb (North African countries, mainly Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia).

Long term, sustained contact between Amazigh languages and dialectal Arabic has had an immense impact on language variation and change in the languages of Morocco (Chtatou, Reference Chtatou1997), and Moroccan Arabic and Moroccan Amazigh languages show similarities in many linguistic features, particularly syllabic and prosodic features (Chtatou, Reference Chtatou1997; Dell & Elmedlouai, Reference Dell and Elmedlaoui2012). An interesting discussion in the literature is the direction of influence due to language contact. Some researchers have attributed the patterns of vowel reduction and complexification of syllable structure observed in Moroccan Arabic to be the result of language contact from Amazigh (Chtatou, Reference Chtatou1997). Others have argued that some phonological features have been borrowed from Arabic into Amazigh, or that the similarities are the result of parallel phonological changes over time (Kossmann, Reference Kossmann2013). There is also bidirectional lexical and structural borrowing: a huge proportion of the Tarifit lexicon contains Arabic loanwords, and Moroccan Arabic also contains lexical and morphological borrowings from Amazigh (Kossmann, Reference Kossmann, Haspelmath and Tadmor2009).

As a response to marginalization, the Amazigh Cultural Movement (ACM) sought to remedy the threat to the Amazigh language and culture by advocating educational, media, and cultural reforms that would rehabilitate Amazigh (El Guabli & Boum, Reference El Guabli and Boum2022). Important cultural events for the Amazigh movement include a speech made by King Hassan II on August 20, 1994, saying that Amazigh is a fundamental component of the Moroccan identity and should be taught for children exactly as the other existing languages. For many, this royal declaration marked the start of official recognition of the historical and cultural importance of Amazigh in Morocco (Zakhir, Reference Zakhir2023). Another important event occurred in the 2001 official speech by King Mohamed VI when he emphasized the importance of Amazigh as a crucial cultural and linguistic part of the country and its identity. As a result, the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (IRCAM) was officially founded in the same year. The Moroccan government recognized Amazigh as an official language in 2011. This led to the presence of Amazigh in official government offices (such as parliament and public administrations to assist speakers), the use of Amazigh on public administrative websites, and the launch of official Amazigh TV channels. Figure 2, for instance, shows signage for the official administrative offices for the Nador municipality of Zeghanghane, written in Arabic, Tifinagh (the traditional Amazigh alphabet), and French. And, in 2023, the first day of the Amazigh new year became an official national holiday. However, Amazigh still remains marginalized relative to Arabic. For instance, Article 5 of the 2011 Moroccan Constitution stipulates that Arabic remains “the official language of the state, and the state works to protect and develop it, and promote its use.” In the same article, Amazigh is introduced as “also an official language because it is a shared heritage between all Moroccans with no exceptions.”

Figure 2 Sign marking the administrative offices for Zeghanghane, in Nador, written in Arabic, Tifinagh, and French.

The Amazigh language was integrated into the Moroccan educational system in the 2003/2004 academic year, initially in a limited number of primary schools nationwide. The number of schools offering Amazigh language instruction gradually increased, reaching a total of 2,221 primary schools by the 2022/2023 academic year, catering to approximately 331,111 students. Meanwhile, the number of trained specialist teachers in Amazigh language instruction grew from 200 to 400 per year. In the future, the authorities aim to train a new generation of bilingual teachers in Arabic and Amazigh, with an annual target of between 1,500 and 2,000 teachers (Al-Turki & Bouhfad, Reference Al-Turki and Bouhfad2023).

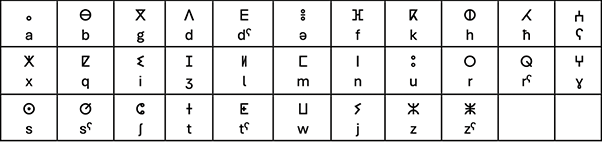

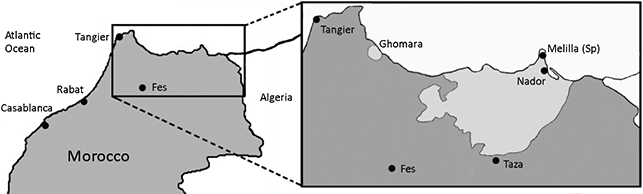

On the other hand, the status of the standardization of the Amazigh language in Morocco sparks debate. In 2003, the Moroccan government decided to codify Amazigh using an adapted form of the ancient Tifinagh script, one of the earliest known phonogrammatic writing systems (Boukous, Reference Boukous2014), dating from 200 BCE (Ishihara, Reference Ishihara2016). Tifinagh was invented by the Tuaregs in the desert of North Africa and it is still in use today.

Tifinagh is mostly consonantal, written either from right to left or left to right. There are some limitations of Tifinagh for writing modern Amazigh. For example, it has no way of indicating initial or medial short vowels (though the point, called a tagherit, may be used to indicate final /a/, /i/ or /u/). Consequently, a modernized form of the Tifinagh alphabet called “Neo-Tifinagh” was officially recognized in Morocco in 2003. Neo-Tifinagh, a “reinvented form” of Tifinagh written from left to right, was initially proposed by the Berber Academy (“Académie Berbère”) and adopted by Algerian activists in the 1970s in order to document their language (mainly Kabylie). Neo-Tifinagh combines Tifinagh characters with characters from other sources, but its use to write Amazigh has stirred political and ideological debates (see Soulaimani, Reference Soulaimani2023). Figure 3 provides the Neo-Tifinagh alphabet along with corresponding IPA symbols.

Figure 3 (Neo-)Tifinagh alphabet with corresponding IPA symbols.

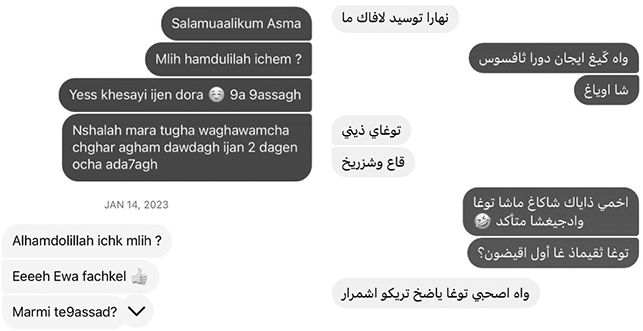

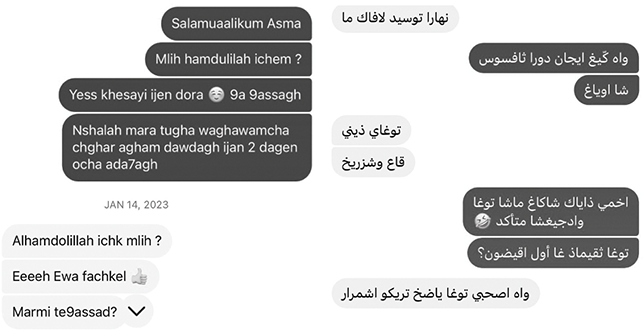

In practice, however, most Tarifit speakers use Latin script to write their language in everyday situations, such as when texting or posting to social media sites. Arabic script can also be used, though this may be less common. Figure 4 shows examples of Tarifit speakers texting using the Latin and Arabic scripts.

Figure 4 Texting in Tarifit using the Latin script (left) and the Arabic script (right).

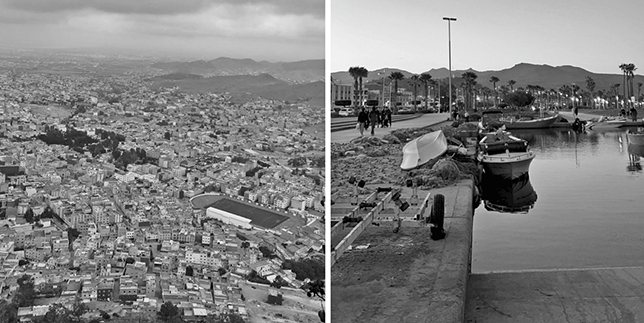

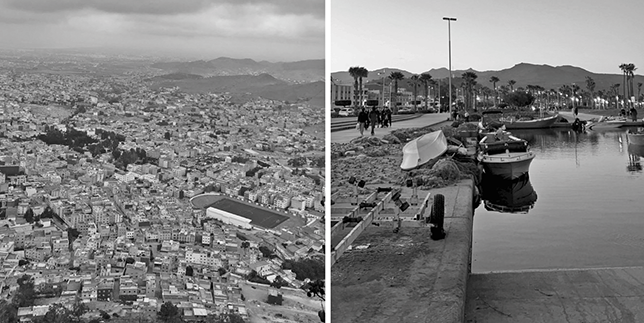

The language described in the Element is representative of the Tarifit variety known as Guelaiya, one of the varieties spoken in Nador, a city with about 565,987 inhabitants (Census, Reference Census2024) in northeastern Morocco, close to the border of Algeria, and home to a large Tarifit-speaking community. Figure 5 shows images of Nador, with a view overlooking the main residential area of the city and a walkway near a waterway.

Figure 5 Pictures of Nador. Left: the main residential area; right: a marina with boats.

The first documented study of Tarifit started in the nineteenth century with the work of René Basset (Reference Basset1897) who lays out a general dialectological overview of the Berber varieties. More recent grammatical descriptions of Tarifit can be found in Lafkioui (Reference Lafkioui2007), which gives a detailed description of the phonological, phonetic, morphological, and syntactic properties, shedding light on the geolinguistic variation, and Kossmann and Mourigh (Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019), which provides a comprehensive grammatical description of the variety spoken in Segangan, a main region in Nador. McClelland (Reference McClelland2008) provides a phonological description of this variety, and there is a dictionary (McClelland, Reference McClelland2004). Descriptions of phonological features of this dialect are also found in other works (such as Tangi, Reference Tangi1991; Dell & Tangi, Reference Dell and Tangi1992; Kossmann, Reference Kossmann1995; Lafkioui, Reference Lafkioui2007).

There is not much phonetic work on Tarifit (Bouarourou, Reference Bouarourou2014; Bouarourou et al., Reference Bouarourou, Vaxelaire, Laprie, Ridouane and Sock2018; Reference Bouarourou, Bouzidi, Vaxelaire, Sock and Adak2020). This Element describes the phonetics of this understudied and endangered language. Section 2 summarizes the phonological system, including the sound inventory, word structures, and major historical phonological processes. Section 3 outlines the speech materials used for the study, motivated by major theoretical issues in phonetic theory, sound change research, and work on the linguistics of Amazigh languages. Section 4 presents the acoustic analysis of words produced by native Tarifit speakers, covering the phonetic realization of the vowel phonemes – three “full” vowels /a, i, u/, and schwa – and variation in the realization of words across speakers. Stylistic variation is also explored by comparing speakers’ productions of clear and fast speech. Section 5 provides a perception study investigating Tarifit native speakers’ spoken word perception. Finally, in Section 6, we offer suggestions for future research.

2 Brief Phonological Sketch

This section provides some relevant facts about the phonology of Tarifit. Amazigh languages are described as “consonantal languages,” meaning that their phonological inventories have a high consonant-to-vowel ratio (Maddieson, Reference Maddieson2013). The phoneme inventory of Tarifit reflects this, containing many consonants and few vowels. Thus, Tarifit words rely heavily on consonantal contrasts, and less on vowel contrasts, for making semantic distinctions.

2.1 Consonants

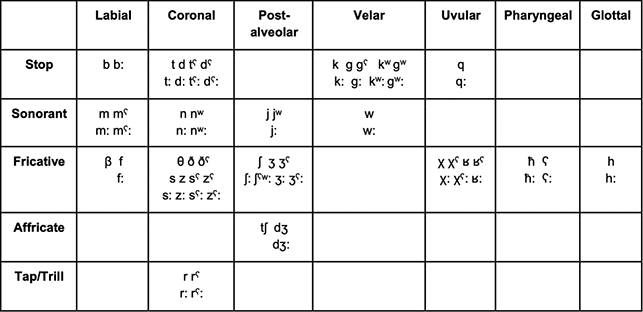

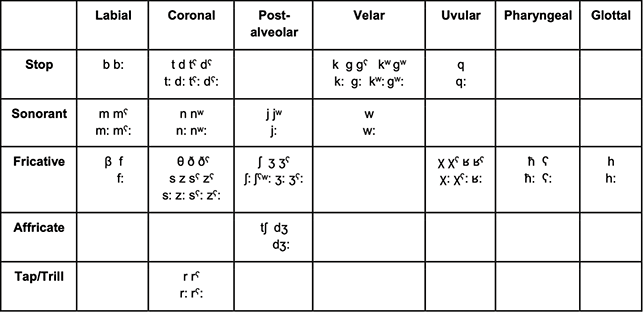

The consonant inventory of Tarifit is provided in Figure 6 and example words illustrating the different consonant contrasts are provided in (1) below.

Figure 6 The consonants of Tarifit (Nador [Guelaiya] variety).

(1) Example words

/β/ βaβa ‘father’ /b/ batata ‘potato’ /b:/ qub:u item of clothing /m/ asrəm ‘fish’ /mˤ/ azəmˤ ‘open’ /m:/ asəm:iðˁ ‘cold/wind’ /mˤ:/ zəmˤ: ‘squeeze’ /f/ afraðˁ ‘trash’ /f:/ if:ar ‘he hid’ /w/ awar ‘talk’ (noun) /w:/ ðuw:əχ ‘faint’ /t/ tak ‘leave it’ /t:/ itmət:a ‘he dies’ /tˁ/ amutˁa ‘motorcycle’ /tˁ:/ imətˁ:awən ‘tears’ /d/ akida horse /d:/ d:am ‘get off’ /dˁ/ dˤar ‘get down’ /dˁ:/ dˁ:aθ ‘you get off/down’ /n/ ʕini ‘maybe’ /n:/ aʒən:a ‘sky’ /nʷ/ jənʷa ‘he cooked’ /nʷ:/ ənʷ:arˤ ‘light’ /θ/ θam:aθ ‘earth/floor’ /ð/ ða ‘here’ /ðˁ/ ðˁaðˁ ‘finger’ /s/ ərkisan ‘cups’ /s:/ aməs:as ‘sour’ /sˁ/ sˤəf:a ‘filter’ /sˁ:/ θaməsˁ:at ‘thigh’ /z/ izi ‘fly’ /z:/ agəz:a ‘butcher’ /zˁ/ azˁru ‘rock’ /zˁ:/ zˁ:u ‘to plant’ /r/ sara ‘wander!’ (simple imperative) /r:/ ʁar: ‘only’ /rˁ/ ifurˁaðˁ ‘trash’ /rˁ:/ jiqarˤ: əβ ‘he approached’ /j/ uja ‘walk!’ (simple imperative) /j:/ ʒij:əf ‘choke’ /jʷ/ jʷa ‘moon’ /ʃ/ aʃəw:af ‘hair’ /ʃ:/ jitiʃ: ‘he gives’ /ʃ:ˤʷ/ əʃ:ˤʷarˤ ‘be filled’ /ʒ/ aʒəd:if ‘head’ /ʒ:/ jəsˤiʒ:əd ‘he hunted’ /ʒˤ/ uʒˤar ‘walk’ /ʒˤ:/ əʒˤ:af ‘cliff’ /tʃ/ χatʃi ‘maternal aunt’ /dʒ/ dʒuz ‘almonds’ /dʒ:/ amədʒ:ukər ‘friend’ /k/ amədʒ:ukər ‘friend’ /k:/ k:ar ‘get up’ /kʷ/ jəkʷa ‘he insults’ /kʷ:/ jətakʷ:aðˤ ‘he is arriving’ /g/ jətaɡi ‘he refuses’ /g:/ jənəg:əz ‘he is jumping’ /ɡʷ/ jəɡʷa ‘he walks’ /ɡʷ:/ aðəɡʷ:ar ‘father-in-law’ /ɡˤ/ fiɡˤa ‘snake’ /q/ aqəm:um ‘mouth’ /q:/ jəq:as ‘he tasted’ /χ/ ərfaχa ‘charcoal’ /χ:/ waχ:a ‘OK’ /χˤ/ χˤawəð ‘mess up’ /χˤ:/ rəχˤ:u ‘now’ /ʁ/ ʁar: ‘only’ /ʁ:/ məʁ:a ‘ɡrow old’ (imperfective) /ʁˤ/ ʁˤana ‘appetite’ /h/ abuhari ‘fool’ /h:/ fəh:əm ‘understand!’ (intensive imperative) /ħ/ muħar ‘improbable’ /ħ:/ rəħ:əm ‘move back!’ (intensive imperative) /ʕ/ ərʕaʕa ‘juniper’ /ʕː/ buʕːu ‘monster’

Tarifit is a “spirantizing” language, where historical bilabial and dental stops are produced as fricatives in all word environments, yet they are produced as stops when geminated. In contrast, velar and uvular singleton stops are usually produced as stops. So, for words where there is a singleton~geminate alternation, this is realized primarily as a fricative~stop contrast for bilabial and dental plosives (e.g. /ʒbð/ ‘to pull out’, simple imperative: [ʒβəð] vs. intensive imperative: [ʒəb:əð]; /χðm/ ‘to work’, simple imperative: [χðəm] vs. intensive imperative [χəd:əm]), but as a singleton~geminate contrast for velar and uvular plosives (e.g. /skf/ ‘to suck up’, simple imperative: [skəf] vs. intensive imperative: [sək:əf]; /nqβ/ ‘to pick’, simple imperative: [nqəβ] vs. intensive imperative: [nəq:əβ]). There are some contexts in which singleton stops occur, such as in a small number of lexical items (e.g. /tak/ ‘leave it’), loanwords (e.g. /batata/ ‘potato’) and in word-final clusters (e.g. /χə.mənt/ ‘they (F) worked’).

Consonants can contrast in labialization in Tarifit as well. Labialized consonants are distinct from consonant + /w/ sequences (McClelland, Reference McClelland2008, p. 31), for example: /jəʃˤʷ:arˤ/ ‘it is full (of something)’ vs. /əʃˤ:warˤ/ ‘advice’; /jənwa/ ‘he had an idea’ vs. /jənʷa/ ‘he cooked’.

Consonants also contrast in pharyngealization, and some consonants are labialized and pharyngealized. The coarticulatory effect of pharyngealized consonants results in vowel alternations across plain and pharyngealized consonant contexts (e.g. /a/ in [d:ɛθ] ‘live’ vs. [dˁ:ɑθ] ‘get down/get off’).

In addition to the consonants listed in Figure 6, there are several consonants that appear in a limited set of Tarifit words or as allophonic variants of phonemes. For instance, /p/ occurs in some loanwords from Spanish and French (e.g. /plasa/ ‘plaza’).

2.1.1 Syllable Structure

Tarifit words display a strong preference for CVC, CV, V, and VC syllable structures (Dell & Tangi, Reference Dell and Tangi1992; McClelland, Reference McClelland2008). Other possible syllable structures in Tarifit are CVCC, CCVC, and VCC (McClelland, Reference McClelland2008). For words with more complex syllable structures, phonological descriptions state that schwa is inserted (Mourigh & Kossmann, Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019). Complex onsets and codas can contain a variety of sonority sequences. Tarifit onset clusters can contain sequences of consonants that rise (e.g. /ħməð/ ‘thank!’, /χnəs/ ‘bend down!’), plateau (e.g. /sʃən/ ‘show!’, /ʒβəð/ ‘pull!’), and decrease (e.g. /ʕβəð/ ‘worship!’, /ðqər/ ‘weigh!’) in sonority toward the syllable center. Coda clusters can contain a variety of sonority sequences as well (e.g. /awðˤ/ ‘arrive!’, /juðf/ ‘he entered’, /rmuʒθ/ ‘wave’, /azm/ ‘open!’).

The allowance of complex consonant sequences (including vowelless words as allowable phonetic variants of some words, which we present data in detail for in this Element), has led some researchers to propose that consonants can be syllabic – that is, serving as the syllable nuclei – in Tarifit (McClelland, Reference McClelland2008).

2.2 Vowels

Words in Tarifit can contain four different contrastive vowels: three “full” vowels and schwa /a, i, u, and ə/. Vowel length is not contrastive in Tarifit. There are no phonemic diphthongs or vowel clusters, though dynamic vowel qualities can surface in some coarticulatory contexts and “long” vowels can surface when morphemes containing two vowels occur successively.

2.2.1 Non-concatenative Morpho-phonology of Tarifit: the Role of Schwa

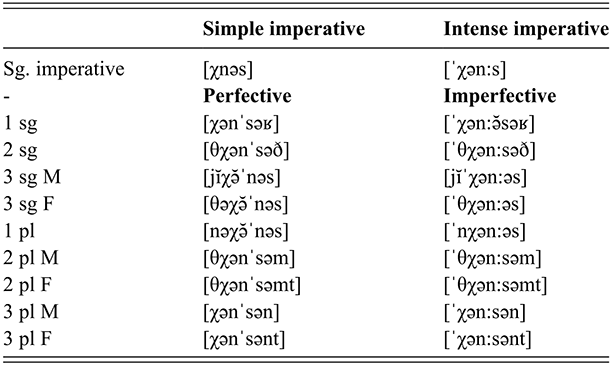

Tarifit has non-concatenative word formation processes where consonantal roots, defined semantically, are modified with vowels and prosodic patterns to derive words. In addition, affixes can be concatenated to the stem. This is illustrated in Table 1 displaying a verbal paradigm for the triconsonantal root /χns/ ‘bend down’ in the imperative, perfective, and imperfective forms.

| Simple imperative | Intense imperative | |

|---|---|---|

| Sg. imperative | [χnəs] | [ˈχən:s] |

| - | Perfective | Imperfective |

| 1 sg | [χənˈsəʁ] | [ˈχən:ə̆səʁ] |

| 2 sg | [θχənˈsəð] | [ˈθχən:səð] |

| 3 sg M | [jĭχə̆ˈnəs] | [jĭˈχən:əs] |

| 3 sg F | [θəχə̆ˈnəs] | [ˈθχən:əs] |

| 1 pl | [nəχə̆ˈnəs] | [ˈnχən:əs] |

| 2 pl M | [θχənˈsəm] | [ˈθχən:səm] |

| 2 pl F | [θχənˈsəmt] | [ˈθχən:səmt] |

| 3 pl M | [χənˈsən] | [ˈχən:sən] |

| 3 pl F | [χənˈsənt] | [ˈχən:sənt] |

The status of schwa in Tarifit is highly debated. Are the schwas in Table 1 underlyingly present in the lexicon of Tarifit speakers? Or are they epenthetic? Both stances have been claimed in literature on Tarifit (and in related Amazigh languages). Most Berberists (Laoust, Reference Laoust1918; Basset, Reference Basset1952; Penchoen, Reference Penchoen1973) argued that schwas in many Amazigh languages are inserted by rule because their occurrence is predictable. Laoust (Reference Laoust1918) uses the sonority index of consonants to explain schwa insertion. He proposes that in a string of C1C2 where C1 is less sonorant than C2, an impermissible cluster is formed, and thus a schwa is inserted between the two consonants.

Many researchers have argued that schwa in Tarifit is the result of an epenthesis process functioning to break up sequences of multiple consonants in a row, and schwa can be predicted from the phonological structure of the word; that is, schwa appears to break up triconsonantal sequences (/CCC/ ⇒ [CCəC]) (Kossmann, Reference Kossmann1995). Mourigh and Kossmann (Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019), for instance, argue that in the Nador variety of Tarifit, schwa is usually inserted from right to left by means of a rule that inserts it between two consonants following the constraint that schwa is never inserted to form an open syllable.

However, Kossmann (Reference Kossmann1995) argues that there is evidence that some schwas in Tarifit are underlyingly present. For instance, he notes that some suffixes appear to always surface with schwa, while others never do, which cannot be explained following the schwa insertion rule. Table 1 illustrates this: compare the first person singular [χənˈsəʁ] and the third plural feminine [χənˈsənt]. Verbs conjugated with [-ʁ] must be produced with a full schwa before the suffix and verbs conjugated with [-nt] always have a schwa before the [n] but never before the [t], despite the fact that such a form is phonotactically allowed in Tarifit (*[χnəsnət]). Other Tarifit experts claim that schwa is lexically specified in some words. Tangi (Reference Tangi1991), for instance, argues that in some cases schwa can be produced in an open syllable, and this is evidence that it is representationally present (e.g. /mʃðˤ -ʁ – as/ ‘brush’ perfective – 1sg.SUBJ – 3sg.ACC [məʃ.ˈðˤə.ʁas] ‘I brushed it’ [stress placement ours]).

Some researchers have argued that there are actually two types of schwa in Tarifit (and other Amazigh languages). Kossmann (Reference Kossmann1995), for instance, allows both epenthetic and lexically specified schwas in Tarifit. Dell and Tangi (Reference Dell and Tangi1992) propose that one type of schwa in Ath-Sidhar Tarifit is a transitional vocoid that surfaces between hetero-organic and/or voiced consonants, while the other schwa is phonologically inserted to serve as a syllable nucleus to syllabify consonants. In related Amazigh languages, systematic investigations have provided evidence for two distinct types of schwa. In Tashlhiyt, for instance, a schwa sometimes surfaces in phonologically vowelless words as a way to carry prosodic stress, while a second schwa functions as a transitional vocoid between phonologically marked consonant sequences (Ridouane & Cooper-Leavitt, Reference Ridouane and Cooper-Leavitt2019).

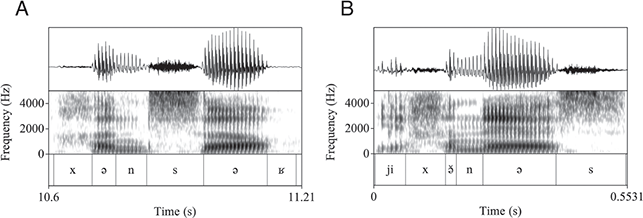

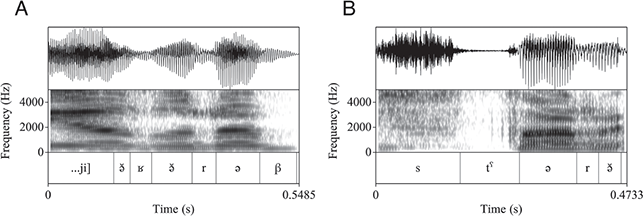

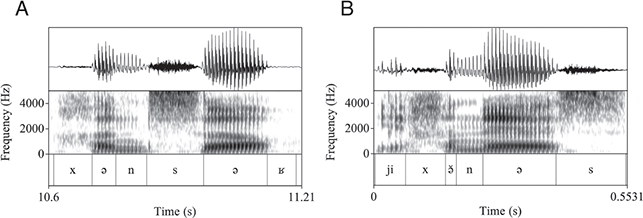

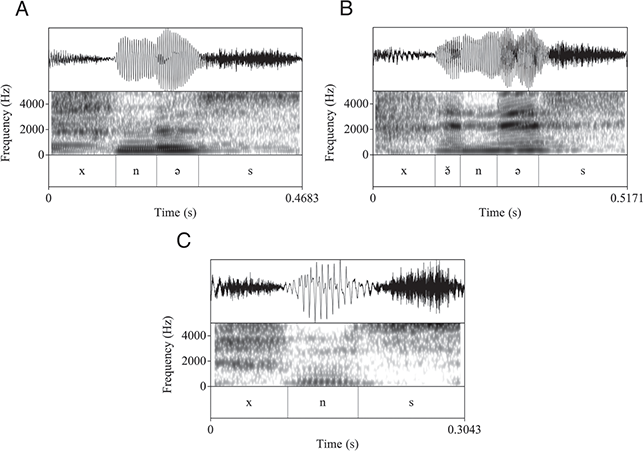

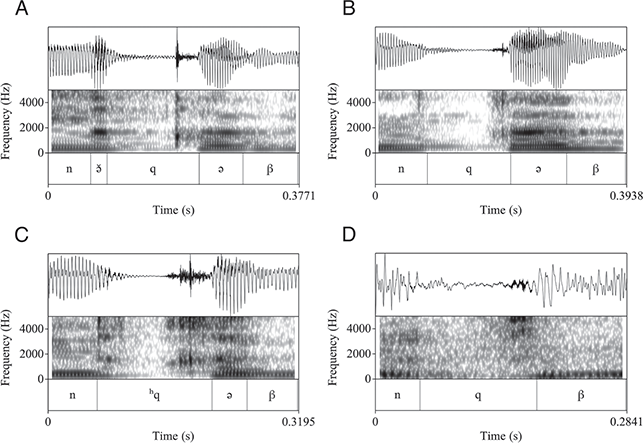

Note that Tarifit triconsonantal verbs following the conjugation pattern in Table 1 surface with one or multiple schwas and follow the “two schwas” analysis. The transcriptions in Table 1 are written with either a “full” schwa [ə] or a short schwa [ə̆]. These follow our own conventions derived from a careful phonetic analysis. For instance, Figure 7 provides waveforms and spectrograms illustrating productions of two of the forms in Table 1. Figure 7.a, [χənˈsəʁ] is produced with two schwas. The second is stressed and longer, while the first is unstressed and shorter, but still forming a robust syllable nuclei. Figure 7.b, [jĭχə̆ˈnəs] is produced with two vowel nuclei – an unstressed /i/ in the third person subject prefix and a stressed schwa between C2 and C3 of the root. Yet, a third short vowel surfaces between C1 and C2. This vowel can be considered a transitional vocoid, surfacing between C1 and C2 when they are adjacent but not tautosyllabic. It does not appear to be counted in syllabification (though more work on this issue is needed).

Figure 7 Triconsonantal verb /χns/ in two conjugated forms. A: [χənˈsəʁ] ‘I bent down’; B: [jĭχə̆ˈnəs] ‘he bent down’.

2.2.2 The Phonetics of Schwa in Tarifit

Few experimental studies report on the specific vowel properties of Tarifit (cf. Lafkioui, Reference Lafkioui2011). The prevalence of schwa in Tarifit, in particular, raises interesting questions about how it might vary in acoustic-phonetic ways. Inspection of the chart of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) would suggest that schwa is a vowel like any other; a central open-mid/close-mid unrounded vowel. However, the label “schwa” has been applied to a phonological value that is especially variable in its phonetic properties (Silverman, Reference Silverman and van Oostendorp2011). This variability is usually a consequence of schwa’s context: flanking consonants and vowels may have a significant coarticulatory influence on schwa’s phonetic starting and ending postures, typically far more coarticulatory influence than on vowels of other qualities. In terms of duration – a phonetic property that the IPA vowel chart does not indicate – schwa is typically quite short. Schwa is characterized as a weak or reduced vowel (Flemming, Reference Flemming2009). This is based on a number of generalizations about its crosslinguistic behavior: schwa is the outcome of neutralization of vowel quality contrasts in a number of languages including English (Chomsky & Halle, Reference Chomsky and Halle1968), and Dutch (Booij, Reference Booij1999). It is also commonly restricted to unstressed syllables due to vowel reduction and/or resistance to being stressed, such as in English, Dutch, and Indonesian (Cohn, Reference Cohn1989). Crosslinguistically, schwa is often singled out by deletion, such as in Dutch (Booij, Reference Booij1999), English (Hooper, Reference Hooper1978), French (Dell, 1973), and Hindi (Ohala, Reference Ohala1983), or insertion (Hall, Reference Hall, Kim, Miatto, Petrović and Repetti2024). Thus, it is a vowel that is relevant to many crosslinguistic phonological processes.

Descriptions of schwa in Tarifit are consistent with it being a vowel that is short and subject to coarticulation from adjacent consonants. Mourigh and Kossmann (Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019) state that, “depending on context and speech tempo, schwa may be shortened to the extreme or not pronounced at all” and that “it is quite often absent in actual pronunciation, especially in fast speech” (p. 25). However, as illustrated in Figure 7, there appear to be different types of schwas in Tarifit. One that carries stress is reliably present in the production of words and can act as a syllable nucleus. Another surfaces between consonants for articulatory purposes, and perhaps this can be deleted or has more variable phonetic properties. In this Element, we investigate the phonetics of schwa in Tarifit in detail. We compare vowel realization in clear and fast speech, in particular, in order to investigate the claim that schwa is reduced more in fast speech and how its realization might be affected by speaking style variation.

2.3 Issues with /r/

2.3.1 Merger with (*)/l/

One historical change that happened in Tarifit phonology was the merger of *l with /r/. This is an innovation unique to Tarifit, and related Amazigh languages have an l-r contrast (e.g. cognates across Tarifit and Tashlhiyt: Tarifit /trəf/ ‘to get mixed up’ vs. Tashlhiyt /tlf/; Tarifit /grəd/ ‘mistake’ vs. Tashlhiyt /ʁltˤ/). Not all dialects of Tarifit display the l-r merger; for instance, some of the Eastern varieties, such as that spoken in Kebdana (“Tachebdant”). The l-r merger also does not apply to forms with geminated /l/. Geminate /l:/ becomes [dʒ:]. For instance, /qrəb/ ~ /iqədʒ:əb/; /θaməllaht/ (from Classical Arabic /milh/) ~ /θamədʒ:aht/.

/l/ is present, however, in many words in Tarifit due to recent borrowings from Arabic, French, and Spanish that contain /l/. For example, /llah/ ‘god’, /lalla/ ‘ma’am’, /ləssəns/ ‘gas’, /plasa/ ‘plaza’, /lkitab/ ‘book’, and /lbəlgha/ ‘slippers’. There are also cases of borrowings from Arabic before and after the merger that illustrate the historic time depth of language contact with Arabic and its complex role on Tarifit. Examples are Arabic nouns that are borrowed with a definite article, as part of the stem become /r/ (e.g. /ərħið/ ‘wall’, /ərbar/ ‘mind’, /ərfuta/ ‘towel’) versus more recent ones that retain /l/ initially (e.g. /lkitab/ ‘book’). So, while there is a historical /l/ → /r/ merger in Tarifit, the existence of many recent borrowings containing /l/ means that this is a marginal phoneme in the language (e.g. /hləm/ ‘dream’, a recent Arabic borrowing).

2.3.2 Postvocalic /r/ Variation

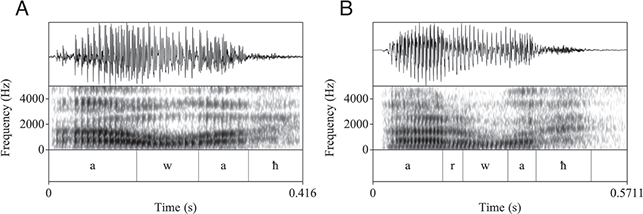

In Tarifit, the realization of postvocalic /r/ is optional following full vowels (when not preceded by another full vowel, i.e., /r/ → 0 / V _ # or C). For example, /arwaħ/ ‘come!’ can be pronounced variably as [arwaħ]~[awaħ]. This r-dropping is reported in many phonological descriptions of Tarifit (Tangi, Reference Tangi1991; Amrous & Bensoukas, Reference Amrous, Bensoukas, Boumal and Ameur2004; Lafkioui, Reference Lafkioui2011; Mourigh & Kossmann, Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019) – and some also report variation in rates of r-dropping across regional dialects – but, to our knowledge, there are no quantitative studies of its distribution and frequency across speakers within a dialect. Thus, in this Element, we investigate the realization of postvocalic r-dropping in Tarifit as an ongoing sound change and quantify its phonological and acoustic patterning across speech styles and speakers. Similar to the schwa~zero alternations in Tarifit, r-dropping is a phonological process involving deletion. Thus, it is relevant to understand the phonetic conditioning of this process and also understand how it integrates with the larger phonological system of the language.

2.4 Stress and Prosody

Amazigh languages have no lexical tones, and it is generally assumed that Northern Amazigh languages have no lexical stress (Kossmann, Reference Kossmann, Frajzyngier and Shay2012). In general, the default position of word stress in Tarifit is on the rightmost syllable, but shifts based on syllable weight with the heavier syllable attracting stress. This is illustrated in Table 1: stress falls on the rightmost syllable in /χənˈsəʁ/, but shifts when the medial consonant is geminated in /ˈχən:səʁ/. However, there are a few cases of word-specific stress patterns and some Tarifit words appear to contrast in stress: for example, /ˈwaχ:a/ ‘okay’ vs. /waˈχ:a/ ‘even’. The acoustic correlates of lexical stress involve duration, pitch, and intensity.

McClelland (Reference McClelland1996) investigated the acoustic correlates of prosody in Tarifit. He reports that the pitch and intensity work independently and complementary to each other in signaling clause boundaries and information structure. For instance, intensity appears to mark prosodic boundaries: higher intensity is found in clause-initial position and lower intensity is found in clause-final position. Meanwhile, pitch contours appear governed to mark information structure: higher pitch is observed on topicalized elements and adverbial clauses, while lower pitch is observed in “orientation” clauses used to provide background information or situational context (McClelland, Reference McClelland1996).

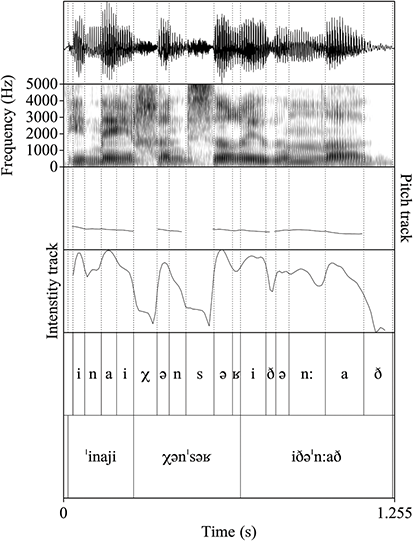

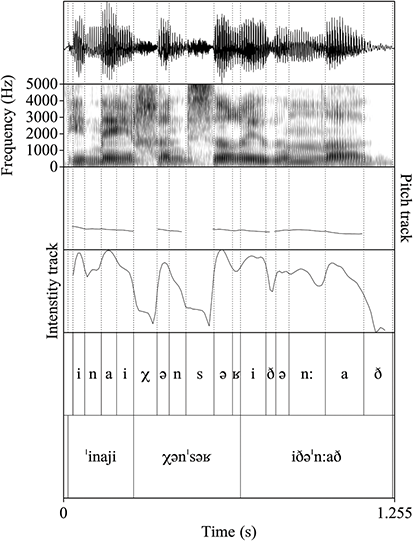

Figure 8 provides the waveform, spectrogram, pitch track, and intensity track of the sentence /ˈinaji χənˈsəʁ iðəˈn:að/. As seen, the pitch contour starts high and decreases over the utterance signaling a declarative phrase. Within lexical items, pitch rises on stressed syllables. Intensity is also increased on stressed syllables within words.

Figure 8 Waveform, spectrogram, pitch track and intensity track for the sentence /ˈinaji χənˈsəʁ iðəˈn:að/ ‘tell me “I bent down” yesterday’.

3 Materials for Phonetic Research on Tarifit

3.1 Theoretical Issues that Motivate the Data Presented in this Element

Tarifit remains highly understudied with respect to phonetic variation and perceptual patterns by speakers. The previous literature on phonological and phonetic patterns of Tarifit lack adequate phonetic documentation or have depended on impressionistic descriptions. Our aim in the present study is a basic descriptive analysis of the phonetics of Tarifit, as examining understudied smaller speech communities can contribute a greater understanding to the phonetic patterns in natural human languages. To that end, we collected both speech production and perception data by native speakers.

The phonetics of Tarifit can address broader questions in phonetic and phonological theory. Several theoretical issues are addressed here, and we have designed our data collection materials and procedure with these goals in mind. We lay out three broad theoretical contributions that motivate the current study and our study design.

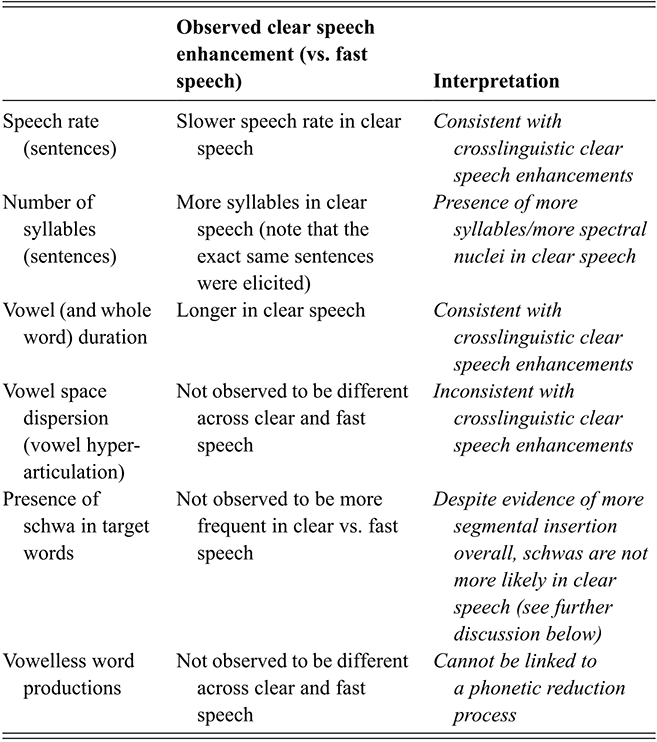

3.1.1 Clear Speech and Style-Conditioned Variation in Tarifit

Throughout a typical day, the speech produced by an individual varies greatly. The acoustic realization of utterances depends on the context, the physical and emotional state of the talker, and the audience. Speech variation can be thought of as lying on a continuum of hyper- to hypo-speech based on a trade-off between the needs of the listener (clarity-oriented) versus the needs of the speaker (efficiency-oriented) (Lindblom, Reference Lindblom, Hardcastle and Marchal1990; Scarborough & Zellou, Reference Scarborough and Zellou2013). More concretely, clear speech is characterized by a variety of acoustic modifications relative to fast (or casual, or conversational) speech, such as slowing speaking rate and producing more extreme segmental articulations (Zellou et al., Reference Zellou, Lahrouchi and Bensoukas2023). Previous research has shown that clear speech significantly enhances intelligibility for both normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners crosslinguistically (Chen, Reference Chen1980; Picheny et al., Reference Picheny, Durlach and Braida1985; Payton et al.,Reference Payton, Uchanski and Braida1994; Gagne et al., Reference Gagne, Querengesser, Folkeard, Munhall and Mastern1995; Schum, Reference Schum1996; Uchanski et al.,Reference Uchanski, Choi, Braida, Reed and Durlach1996; Helfer, Reference Helfer1997; Smiljanić & Bradlow, Reference Smiljanić and Bradlow2005; Tupper et al., Reference Tupper, Leung, Wang, Jongman and Sereno2021). However, what is not yet well understood is the extent to which all the intelligibility-enhancing acoustic adjustments that talkers adopt depend on the phonological and structural properties of their language, or whether some clear speech adjustments are crosslinguistically universal.

In the present study, we elicit clear and fast speech from native Tarifit speakers and examine phonological and phonetic variation across these different styles. Comparing speaking styles when examining an under-studied language is a less frequent approach to phonetic description (cf. Zellou et al., Reference Zellou, Lahrouchi and Bensoukas2022), despite the fact that it can be an intuitive and straightforward methodological approach to soliciting variation from native speakers. Moreover, Tarifit contains typologically unusual phonological structures (mentioned further below). Cross-language examination of clear speech provides a window into understanding the phonetic bases for crosslinguistic typological patterns (Peperkamp & Dupoux, Reference Peperkamp and Dupoux2007). Comparing clear and reduced speech can be one way to understand how sound patterns emerge and evolve over time (Blevins, Reference Blevins2004; Zellou et al., Reference Zellou, Lahrouchi and Bensoukas2022). This is a relatively understudied approach to examining these particular sound patterns and can inform theoretical perspectives on the factors that contribute to phonological contrasts being more or less common across languages of the world.

There have been phonological descriptions of vowel reduction and systematic deletion (or non-insertion) of schwa production in Tarifit under fast speaking conditions (McClelland, Reference McClelland2008, p. 20; Mourigh & Kossmann, Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019). These are all impressionistic descriptions – no study to our knowledge has measured the rate and realization of vowels in Tarifit across different speaking styles. We will examine vowel production across clear and fast speaking styles in order to examine whether vowel reduction in Tarifit is style-mediated speech.

Many words in Tarifit have full vowels, and some contrast with triconsonantal words in full vowel ~ schwa minimal pairs (e.g. /qrəb/ ~ /qrib/). What type of full vowel variation is found in a consonantal language, like Tarifit? We will measure acoustic variables, such as the degree of vowel variation in full vowels and schwas, using F1/F2 vowel space position. Amazigh languages are described as “consonantal languages,” meaning that they rely heavily on consonantal contrasts and less on vowel contrasts for lexical distinctions. Thus, we predict that there will be substantial variability across words with full vowels, especially in reduced speech. This could make discriminating between different vowels in Tarifit difficult. In fact, there is little work, to our knowledge, directly investigating the extent of vowel variability in an Amazigh language (and its subsequent influence on perception), though Zellou, Lahrouchi, and Bensoukas (Reference Zellou, Lahrouchi and Bensoukas2024) examine the production and perception of vowelless words in Tashlhiyt, a related language. There is some work suggesting that consonant-to-vowel coarticulation leads to substantial phonetic variation in vowels for languages with a high consonant-to-vowel ratio, like Tarifit (e.g. in Arabic: Embarki et al., Reference Embarki, Guilleminot, Yeou, Al Maqtari, Dodane and Embarki2007; Bouferroum & Boudraa, Reference Bouferroum and Boudraa2015). We explore this directly in the current study by comparing vowel space hyper-articulation for full vowels and schwa in Tarifit across different clarity-oriented speaking styles.

Understanding style-conditioned phonetic variation within and across languages is important to address issues of both speaker- and listener-oriented speech patterns (Smiljanić & Bradlow, Reference Smiljanić and Bradlow2005; Zellou et al., Reference Zellou, Lahrouchi and Bensoukas2023). We designed the current phonetic analysis of Tarifit to compare the effect of input- versus output-oriented effects on speech variation.

3.1.2 Theoretical Issues Related to Schwa in Tarifit

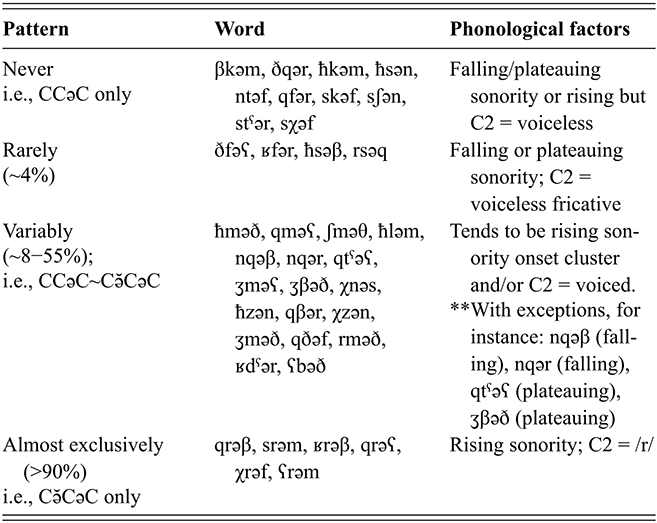

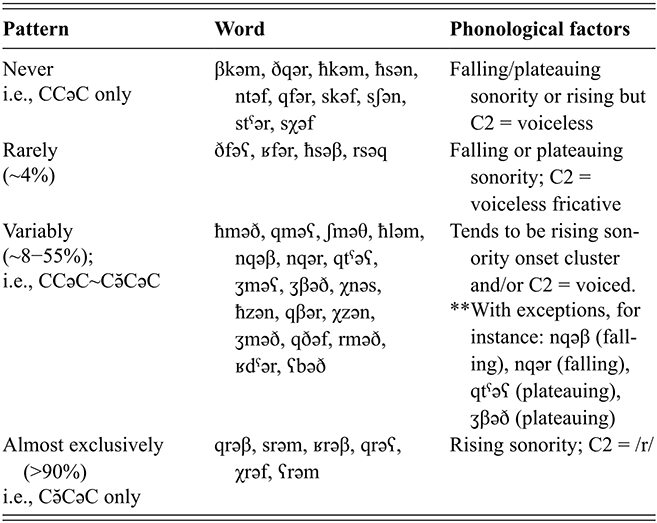

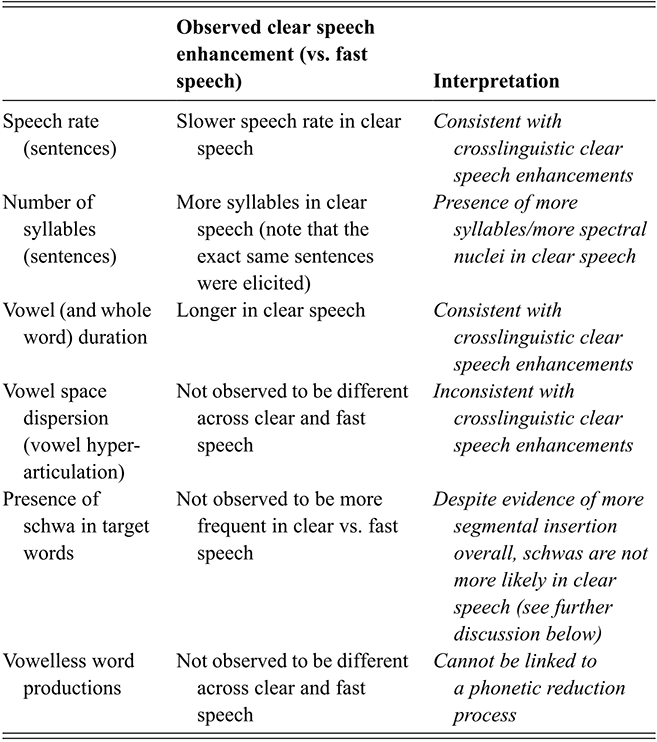

A second major theoretical concern we address is what types of patterns of phonetic variation of schwa occur with the production of triconsonantal roots in Tarifit, an Afroasiatic language with a non-concatenative morphological system. Crosslinguistically, non-concatenative morphological systems are rare. In non-concatenative morphology, it is proposed that words are derived using three types of morphemes: a consonantal root, a vocalic melody, and a prosodic template for how the segments are organized into CV structures (McCarthy, Reference McCarthy1981). For example, Classical Arabic triconsonantal stems /k-t-b/ are derived via vowel-and-prosodic template patterns: for instance, /kataba/ ‘he wrote’, /kattaba/ ‘he caused to write’, /kitaab/ ‘a book’. Tarifit has a non-concatenative morphological system with its own unique properties, so triconsonantal verb stems do not have full-vowel vocalic melodies and surface with a schwa: /χdm/ ‘to work’, [χðəm] ‘work!’. Thus, triconsonantal verb stems in Tarifit have root-and-template morphological alterations that do not involve a full-vowel vocalic melody. We will look at the phonetic variation associated with these words. In particular, we ask how schwa is realized in production and perception in Tarifit, for words containing triconsonantal roots and a schwa-based vocalic melody; here, we examine the CCəC prosodic template pattern associated with the simple imperative form of the verb. For instance, is there variation in the production of triconsonantal roots that take the CCəC prosodic template? Are there words that have variable phonetic shapes? Is schwa the same length in all words? Do some words have more or fewer schwas? We focus on words with CCəC structure as a starting point to understand the nature and distribution of schwa in Tarifit.

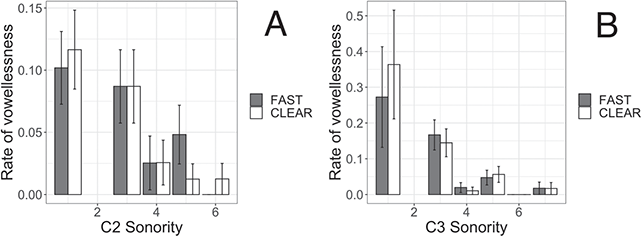

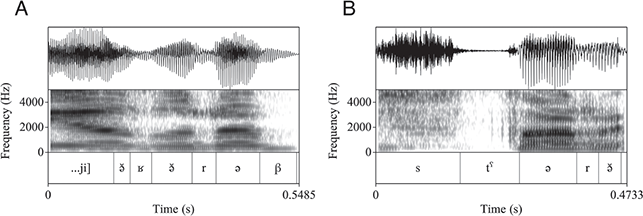

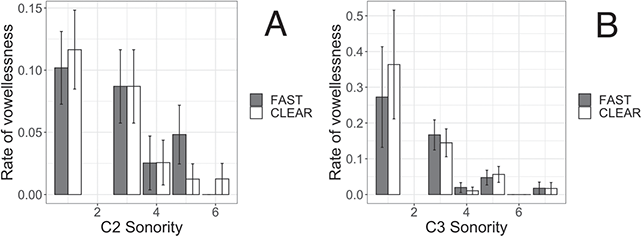

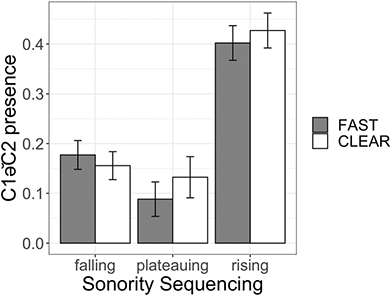

In the next sections, we motivate the study of two issues related to schwa. First, we look at issues related to variable schwas that are present in the initial consonant clusters in CCəC words. These schwas are not always present, according to our initial investigation. Sometimes, CCəC words are pronounced like [Cə̆CəC], with a shorter schwa/“vocoid” element between C1 and C2. In Section 3.1.2.1, we explore what phonological factors might predict when this C1ə̆C2 schwa surfaces. In particular, we predict, based on crosslinguistic studies of vowel intrusion and epenthesis, that C1ə̆C2 is driven by issues related to sonority and syllable structuring features of these words in Tarifit. Speaking style might also play a role in the presence and realization of this vowel, so we examine that as a factor as well.

Next, we examine variation in the “prosodic template” schwa in CCəC words (i.e., the schwa between C2 and C3). Again, our preliminary investigations led us to observe some variations in the realization of this schwa. In particular, CCəC words can sometimes be produced as vowelless – that is, with no phonetic vowel present in the produced word. Our study will explore whether this type of phonetic variant of CCəC words is systematically produced by Tarifit speakers and, if so, under what speech style and phonological conditions they arise.

Schwa Insertion: Consonant Clusters and Sonority

Because of the high ratio of consonants to vowels in the language, and the important role of the consonantal root system in Amazigh lexical formation, many words in Tarifit contain sequences of consonants, with few to no “full” vowels (i, u, a). This results in words that contain consecutive consonants that vary in their sonority patterns. For example, triconsonantal verbs in Tarifit can contain words with consonant cluster onsets that have sonority rises: /qrəʕ/ ‘rip!’, /ʒməð/ ‘freeze!’, /qməʕ/ ‘suppress!’; plateaus: /ħsəβ/ ‘count!’, /sχəf/ ‘pass out!’, /sʃən/ ‘show!’; and falls: /nqəβ/ ‘pick!’, /ħkəm/ ‘judge!’, /ntəf/ ‘pluck!’.

In our CCəC target words, we examine whether variations in the sonority profile of the first and second consonants condition systematic variation in the presence and duration of a schwa. Word-onset sonority profiles are argued to be more constrained than coda profiles crosslinguistically (Pouplier & Beňuš, Reference Pouplier and Beňuš2011), and listeners seem to be more sensitive to sequential probabilities in onset position (Van der Lugt, Reference Van der Lugt2001). The sonority profile of consonant sequences has also been shown to be a meaningful classification for languages related or in close contact with Tarifit, such as Tashlhiyt (Lahrouchi, Reference Lahrouchi2010; Zellou et al., Reference Zellou, Lahrouchi and Bensoukas2024) and Moroccan Arabic (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Gafos, Hoole and Zeroual2011; Zellou & Afkir, Reference Zellou and Afkir2025).

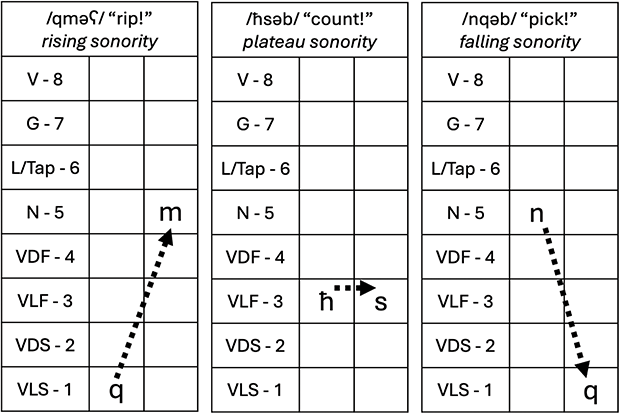

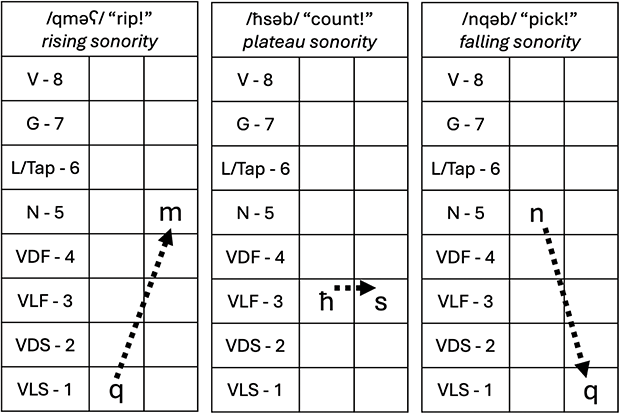

The three sonority profile types (rising, plateau, and falling) are illustrated in Figure 9. In each example, the segments are ranked based on the sonority hierarchy (Parker, Reference Parker2002) to illustrate the differences across word types. Sounds are assigned a ranking within a universal hierarchy of sonority: vowels are assigned the highest numerical sonority score, and consonants are assigned lower values based on their acoustic-sonority properties (8 = vowels; 7 = glides; 6 = liquid/rhotic tap /r/; 5 = nasals; 4 = voiced fricatives; 3 = voiceless fricatives; 2 = voiced stops; 1 = voiceless stops). For rising sonority clusters, sonority increases from the first to the second segment. In plateauing sonority clusters, there is not a large sonority difference from C1 to C2. In falling sonority clusters, sonority decreases from C1 to C2. It has been argued that the sonority hierarchy is an active mechanism in shaping sequences of onset clusters across languages (Berent et al., Reference Berent, Lennertz, Jun, Moreno and Smolensky2009). In particular, onset consonant clusters with rising sonority are unmarked structures, since preferred syllable structures contain sequences with peak sonority in the nucleus and decreasing sonority at the edges (Clements, Reference Clements, Kingston and Beckman1990; Zec, Reference Zec1995).

Figure 9 Some Tarifit words with onset consonant clusters varying in sonority.

Figure 9Long description

In each example, the segments are ranked based on the sonority hierarchy (Parker, 2002) to illustrate the differences across word types. Sounds are assigned a ranking within a universal hierarchy of sonority: vowels are assigned the highest numerical sonority score, and consonants are assigned lower values based on their acoustic-sonority properties (8 = vowels, 7 = glides, 6 = liquid/rhotic tap /r/, 5 = nasals, 4 = voiced fricatives, 3 = voiceless fricatives; 2 = voiced stops; 1 = voiceless stops). For rising sonority clusters, sonority increases from the first to the second segment. In plateauing sonority clusters, there is not a large sonority difference from C1 to C2. In falling sonority clusters, sonority decreases from C1 to C2.

How might the sonority of onset clusters in Tarifit influence C1ə̆C2 schwa? This Element investigates if sonority plays a role in patterns of schwa variation in Tarifit. Many Tarifit words contain highly complex syllable structure and consonant sequences that defy cross-linguistic sonority preferences. In our target word list, we have triconsonantal words that vary in the sonority value of the segments. We predict sonority will condition schwa variation. Much crosslinguistic work on sonority sequencing of adjacent consonants predicts patterns of vowel epenthesis and deletion (e.g. Hall, Reference Hall2006; Crouch et al., Reference Crouch, Katsika and Chitoran2023). Could sonority patterns of consonants in Tarifit explain some of the schwa variation? We explore at least two main hypotheses. First, some theoretical work found that the function of epenthesis is to repair phonologically marked or dispreferred word structures (Davidson & Stone, Reference Davidson, Stone, Garding and Tsujimura2003; Hall, Reference Hall2006). Since falling-sonority onset clusters are phonologically dispreferred, one prediction is that C1ə̆C2 schwa will be more frequent (and, perhaps, longer when present) in words that contain consonant sequences with falling sonority.

Second, a recent study on Georgian found that schwa is more likely to be inserted, and longer in duration when present, in rising sonority clusters compared to falling sonority clusters (Crouch et al., Reference Crouch, Katsika and Chitoran2023). These patterns are interpreted as stemming from the coordination of consonant sequences during syllable planning: speakers plan syllables to contain a single nucleus (= a single amplitude envelope peak). For syllables containing a rising sonority cluster, inserting a vocoid between the first and second consonant adds a sonorous element at or around the same location of the underlying syllable nucleus. This is not problematic, so vowel insertion can occur. In contrast, for falling onset clusters, inserting a vocoid between the first and second consonant creates a sonority peak away from the nucleus – this enhances sonority toward the syllable edge (which is a dispreferred structure) and it could create the perception of two sonority peaks in the amplitude envelope (which is dispreferred because speakers are planning a single syllable, not two syllables). A critical articulatory feature of Georgian is that adjacent consonants tend to be non-coarticulated, or timed sequentially, rather than overlapping. So, the presence of large lags between adjacent consonants is a language-specific articulatory property of Georgian (Crouch et al., Reference Crouch, Katsika and Chitoran2023), and hence, the presence of schwas in consonant clusters is a consequence of gestural non-coarticulation in the language. This makes the authors argue that a lack of schwas in falling sonority clusters, in particular, is driven by a motivation to avoid two sonority peaks and maintain the tautosyllabic parse within the syllable. The hypothesis that epenthesis is less likely in voiceless clusters for perceptual reasons related to the syllable parse is also supported by Fleischhacker (Reference Fleischhacker2001) who showed that prothesis is preferred in sibilant + stop clusters, while anaptyxis is preferred in other clusters (in practice usually obstruent + sonorant clusters), for example. Egyptian Arabic istadi ‘study’ vs. bilastik ‘plastic’. Fleischhacker (Reference Fleischhacker2001) also presents results of a perception experiment showing that the preferred epenthesis sites are those that diverge less perceptually from the underlying cluster.

Like Georgian, languages related to or in contact with Tarifit – Tashlhiyt and Moroccan Arabic – also display nonoverlapping consonant coordination (Hermes et al., Reference Hermes, Mücke and Auris2017). And, Tarifit speakers produce greater consonant separation of clusters when speaking Moroccan Arabic than non-Tarifit Arabic speakers (Zellou & Afkir, Reference Zellou and Afkir2025). So, the language-specific articulatory preconditions that might be required for vowel insertion in clusters in Georgian might also be present in Tarifit. If this is the case, we predict that C1ə̆C2 schwa will be more frequent and longer in Tarifit onset clusters containing rising sonority profiles than those with falling sonority profiles.

We will also examine these patterns across clear and fast speaking styles. If vowel insertion for rising sonority clusters (or, more specifically, the blocking of vowel insertion in falling sonority clusters) is related to speakers’ syllable planning, we might find greater differences in schwa realization by sonority profiles across clear and fast speech styles.

Schwa Deletion: Vowelless Words in Tarifit

As mentioned above, our initial exploratory investigations of Tarifit revealed that, occasionally, CCəC words can be phonetically produced as vowelless – with no phonetic vocoids present in the speech signal. In other words, the schwa in CCəC words can be deleted.

It is well-documented that Tashlhiyt contains many vowelless words – words and utterances that contain only consonants and no lexical vowels, for example, /tftktstt/ ‘you sprained it’ (Ridouane, Reference Ridouane2008; Dell & Elmedlouai, Reference Dell and Elmedlaoui2012). Since the two languages are genetically related, Tarifit and Tashlhiyt have many global phonological properties in common – they have similar consonant and vowel inventories, and both languages permit highly complex consonant sequences consisting of rising, plateau, and falling sonority patterns. But, vowelless words are not phonologically present in Tarifit, which has been described as having a process requiring schwas in order to avoid sequences of more than two consonants in a row (Mourigh & Kossmann, Reference Mourigh and Kossmann2019).

However, we believe that phonetically vowelless words are produced in Tarifit. We will examine the production of CCəC words produced by Tarifit speakers to examine how frequently phonetically vowelless words occur. We also ask what the phonological factors are that might allow for vowellessness to occur. And, we ask whether vowellessness varies across speaking style.

Vowelless words are important for phonological theory because they are typologically rare. There is a considerable amount of prior work looking at the phonetic and phonological patterns of vowelless words in Tashlhiyt (Dell & Elmedlaoui, Reference Dell and Elmedlaoui2012; Ridouane, Reference Ridouane2008), where they have become fully phonologized in the language. These studies have enhanced theoretical understandings of the human capacity for phonological structure and variation in languages of the world (Ridouane & Fougeron, Reference Ridouane and Fougeron2011; Ridouane & Cooper-Leavitt, Reference Ridouane and Cooper-Leavitt2019).

What about a language where vowellessness is allophonic? Examining Tarifit, where vowelless production of words appears to be a phonetic variant of some words, can shed light on the phonetic and phonological conditions that have allowed vowellessness to phonologize in other languages (or, perhaps, what blocks vowellessness phonologizing in Tarifit). We will look at the rate and phonetic patterning of vowelless word productions, examining the phonological factors that condition its realization, as well as how it might vary across words, speakers, and speaking styles.

3.1.3 Variation and Sound Change in Tarifit

We guided the phonetic analysis in this Element to focus on features that are highly variable in Tarifit in order to examine patterns of synchronic variation and how they might influence ongoing sound changes.

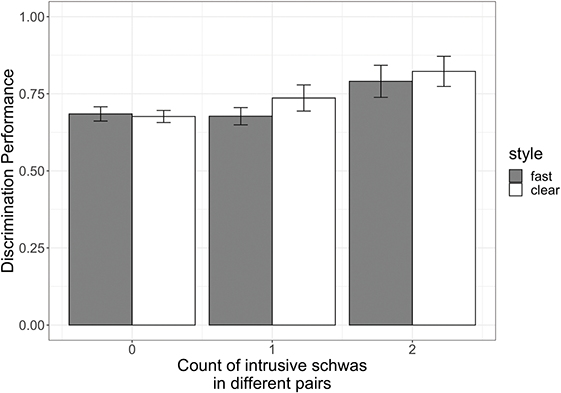

Our results also reflect broader issues about how articulatory and perceptual constraints guide syllable structure variation across languages. In particular, in addition to collecting production data on the categorical and gradient properties of schwa in Tarifit, we will also examine the perception of words with CCəC structure. One approach to understanding the relationship between synchronic and diachronic variation is perceptual: some hold that auditory factors can provide insight into the stability of a phonological system (Ohala, Reference Ohala1993; Blevins, Reference Blevins2004; Beddor, Reference Beddor2009; Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Kleber, Reubold, Schiel, Stevens, Katz and Assmann2019). For instance, it has been argued that observed crosslinguistic phonological tendencies are the result of auditory properties of the speech signal or perceptual processing mechanisms (Blevins, Reference Blevins2004). Does intrusive schwa make Tarifit words more perceptible? That is tested in Section 5, the results from which can speak to these broader theoretical issues, as well as our claims made in Section 4 about the psychological nature of intrusive schwa for Tarifit speakers.

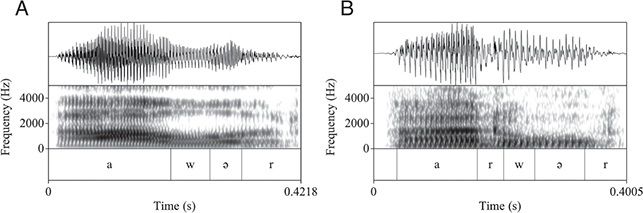

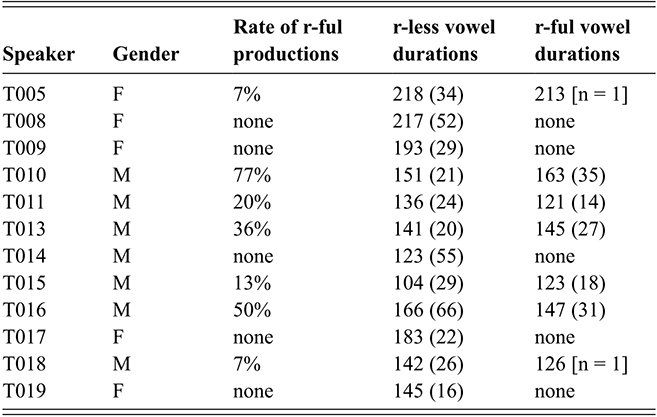

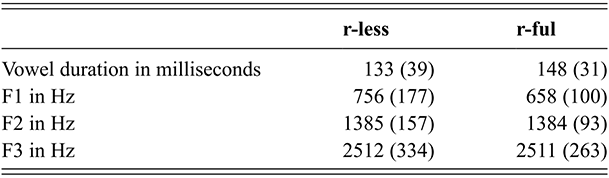

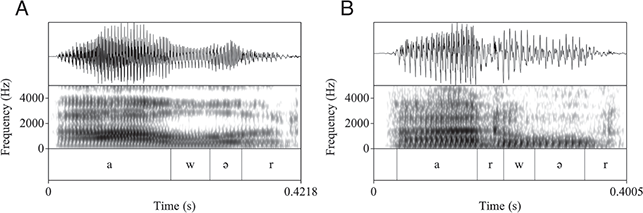

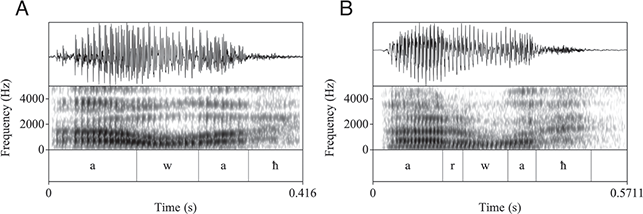

Additionally, as outlined in Section 2, postvocalic dropping of /r/ is reported in many phonological descriptions of Tarifit (Tangi, Reference Tangi1991) – and some also report some variable r-dropping across speakers – but, to our knowledge, there are no quantitative studies of its distribution and frequency across speakers. Moreover, some authors claim that r-dropping in some dialects of Tarifit leads to concomitant vowel changes for /a/: the r-dropped variant is purported to contain longer vowels and sometimes diphthongization (Amrous & Bensoukas, Reference Amrous and Bensoukas2006). We will examine the realization of postvocalic r-dropping in Tarifit: what is the rate of r-dropping? Do all speakers vary equally or is there variation across individuals? Are there acoustic changes in the vowel associated with r-dropping? This appears to be a change in the speech patterns of Tarifit. Thus, we outline the quantitative speech patterns in order to describe phonological variation and ongoing change in the language.

3.2 Target Words

We recorded twelve native Tarifit speakers each producing ninety-four words in Tarifit. The target words were carefully selected for having structures that we examine in the current study: thirty-eight words with CCəC; ten words with CCVC structure; and fourteen words with the context for postvocalic /r/ dropping. There were also twenty-eight filler items. Below, each of the sets of target words for these types is discussed in turn. (The full set of target words used in the current study is provided in the appendices.)

3.2.1 CCəC Words

In order to examine the patterns of consonant clusters and the status of prosodic schwa, our list contained thirty-eight words with CCəC structure. These words are never produced with a full, peripheral vowel, but have an obligatorily phonological schwa between C2 and C3 (according to the phonological summaries of Tarifit). Thus, our goal is to collect words with the structure in order to determine the distribution and acoustic qualities of the vowel. Additionally, our preliminary investigations revealed the presence of short transitional schwa-like vowels produced between some consonant clusters.

We will examine CCəC words in Tarifit for presence and acoustic properties of vowels between C1 and C2 in these words. We hypothesize that the sonority of the onset cluster will predict patterns of C1 and C2 vowel insertion. We selected CCəC words that have a range of phonological characteristics in order to comprehensively examine the factors that predict transitional vowel production in consonant clusters in Tarifit. Seventeen of the CCəC words contain onset clusters with rising sonority sequencing profiles, six contain sonority plateaus, and fifteen contain sonority falls.

We are also interested in the production of phonetically vowelless CCəC words. We predict that sonority properties of C2 and C3 will play a role in predicting when speakers produce CCəC words as fully vowelless. Our CCəC target words contained C2s and C3s that ranged in sonority values from one to seven (see Figure 9 for our sonority scale values).

3.2.2 CCVC Words

Our target words also contained ten Tarifit words with CCVC structure. The purpose of these words was twofold. First, since one of the primary goals of this study is to examine the presence and qualities of vowels produced in words with schwa, we want to compare those patterns to a “control” condition – words with a full vowel. If the presence of the schwa in CCəC is epenthetic in nature, its distribution and acoustic properties should be different from the vowels in CCVC words.

Second, this set of target words will allow us to examine the presence and properties of consonant clusters in CCəC and CCVC minimal pairs, where the phonological properties of C1 and C2 are identical (our list contains four minimal pairs of this type: /ħzən/ vs. /ħzin/; /qrəβ/ vs. /qriβ/; /ʁrəβ/ vs. /ʁriβ/; /ʒməʕ/ vs. /ʒmiʕ/). Thus, we will examine if vowel intrusion between C1 and C2 varies based purely on word structure.

Third, we are also interested in the vowel space of Tarifit – how speakers enhance it in clear speech and how much variation is present given the high consonant-to-vowel phoneme inventory of the language.

Our CCVC items contains words with the three full vowels of Tarifit: /i, a, and u/. Our goal is to provide a basic description of the qualities of these vowels by our speakers.

We note that many of our CCVC words are recent borrowings from Arabic. As mentioned in Section 2, Tarifit contains a large number of Arabic loanwords, many of which occur for both the CCVC and CCəC words. The CCVC words, in particular, are ones that speakers will know have Arabic origin.

3.2.3 Postvocalic /r/ Words

Speakers also produced fourteen Tarifit words that contained the condition for postvocalic r-dropping (i.e., a coda /r/ following the low vowel /a/; e.g. /arwaħ/). Prior work has discussed postvocalic r-dropping as an innovative phonological pattern in Tarifit (Tangi, Reference Tangi1991), and several researchers claim it is associated with compensatory vowel lengthening (Amrous & Bensoukas, Reference Amrous and Bensoukas2006), i.e., [arwaħ] ~ [a:waħ], yet little quantitative work has examined the rate and phonetic characteristics of r-dropping.

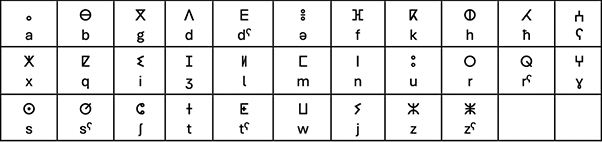

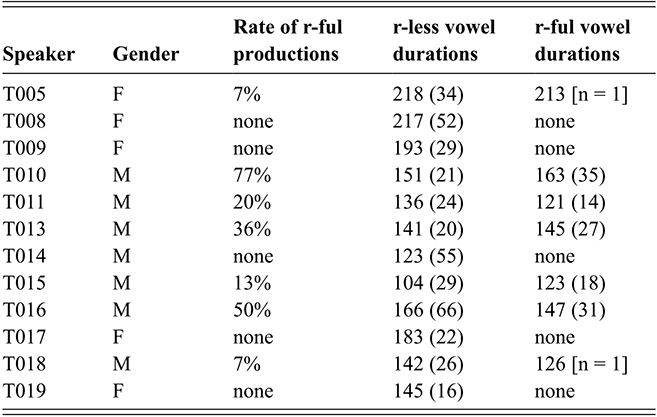

3.3 Speakers, Procedure, and Recordings

We present data produced by twelve native speakers of Tarifit: six females and six males, aged from eighteen to fifty-four (mean = thirty-five).

All participants were living in Nador, and all reported that they spoke at least one other language, including Arabic (n = twelve), French (n = seven), English (n = six), Spanish (n = three), and/or Dutch (n = one).

Speakers were presented with a subset of the target words in a frame sentence: /inaji ___ iðən:að/ ‘Tell me ___ yesterday’. This reading task included eighty target CCəC, CCVC, CVC, and C:VC words (i.e., not the r-dropping words).

The sentences were written in Arabic script with the vowels and syllable structure indicated with diacritics (e.g. geminates diacritized with a shadda, a coda consonant diacritized with a sukun). The target words were presented in a randomized order to the speakers who were instructed to read them. We note that reading Tarifit in Arabic orthography is not natural for many speakers. We had speakers familiarize themselves with the words by looking over a written list of the words before beginning the production task. Sometimes, speakers made an error, and then were instructed to reread the utterance to produce the same word. Only correct productions of target words were analyzed in the present study.

Speakers produced the entire word list two times, in two different speaking styles. To elicit clear speech, they were given instructions similar to those used to elicit clear speech in prior work (Bradlow, Reference Bradlow, Gussenhoven and Warner2002; Zellou et al., Reference Zellou, Lahrouchi and Bensoukas2022): “In this condition, speak the words clearly to someone who is having a hard time understanding you.” Then, the speakers produced the words in a fast speaking style with instructions also similar to those used in prior work (Bradlow, Reference Bradlow, Gussenhoven and Warner2002): “Now, speak the list as if you are talking to a friend or family member you have known for a long time who has no trouble understanding you, and speak quickly.”

Following this sentence reading task, some participants completed the r-dropping word list production. Not all the same speakers who produced the word reading task completed the r-dropping production task, and we were subsequently able to recruit more speakers for the r-dropping task to reach twelve speakers total. For our twelve r-dropping speakers, there were five female and seven male speakers and they had similar age and language background demographics as the group who completed the word list reading task (mean age = thirty-five).

The r-dropping words were not presented in written form – since providing an orthographic representation of the words would mean explicitly writing the “r,” we were worried this might bias speakers to produce r-ful productions. Therefore, a second task was designed where participants heard a recording of a word in Moroccan Arabic and then were instructed to provide a translation of the word in Tarifit (thus, producing one of the words with an r-dropping context). For instance, participants would hear a recording of a speaker producing the Moroccan Arabic word /aji/ ‘come!’ and then they were instructed to provide the corresponding Tarifit word, in this case /arwaħ/ ‘come!’ (variably as [arwaħ]~[awaħ]). We did not provide speaking style instructions in this task and participants produced each of the fourteen r-dropping words in isolation (no frame sentence) only once.

Recordings were done in a quiet room using a head-mounted microphone (Shure WH20XLR) and digitized at a 44.1kHz sampling rate.

3.4 Production Data Processing, Coding, and Analysis

The recordings were segmented into individual sentences, target words, and segments by one of a team of trained research assistants, and then all word and segment boundaries were verified by a second researcher. We used predetermined criteria for identifying the onset and offset of vowels in target words: an abrupt increase or reduction in amplitude of higher frequency formants in the spectrograms; an abrupt change in amplitude in the waveform; and simplification of waveform cycles.

We made several categorical and continuous measurements of the target words for our analyses:

1) Sentence-level speech rate measurements (total number of syllables and number of syllables per second for each utterance) were made with a Praat script (de Jong et al., Reference de Jong, Pacilly and Heeren2021).

2) Word and vowel duration (all target words).

3) Formant values (F1 and F2) of vowels in the target words. F1 and F2 measurements were taken at vowel midpoint (50% of vowel duration) for each target word’s vowel and log mean normalized (Barreda, Reference Barreda2020). Log mean normalization was performed individually for each speaker based on the average formant frequency values for all vowels produced by that speaker.

4) For CCəC and CCVC target words, we coded for the presence or absence of a vowel between the first consonant (C1) and the second consonant (C2) and, if a vowel was present, its duration.

5) For CCəC words, we coded if the word was vowelless or not.

6) For r-dropping words, we categorically coded for whether the post-a /r/ was present (r-ful) or absent (r-less); this was first independently done by two trained researchers and then verified by a third researcher. In cases where there was disagreement, the third researcher made the final decision. Vowel duration and formant frequencies of the /a/ were also measured.

3.5 Statistical Modeling

All acoustic variables were analyzed using separate logistic mixed effects models (for binary variables) or linear mixed effects models (for continuous variables). All statistical models were run in R using the lmer() function in the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015). Where relevant, estimates for degrees of freedom, t-statistics, and p-values were computed using Satterthwaite approximation with the lmerTest package (Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). Full model outputs and glmer/lmer syntax for all models discussed in this Element are provided in the Online Appendix www.cambridge.org/Afkir_Zellou.

4 Acoustic Analysis of Tarifit

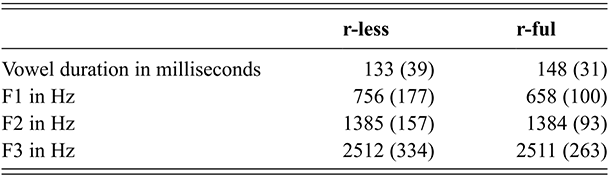

4.1 Acoustic Properties of Utterances across Clear and Fast Speech

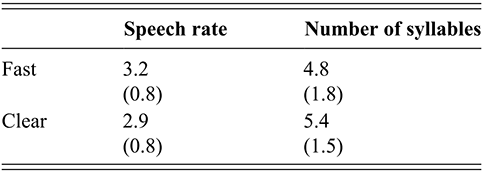

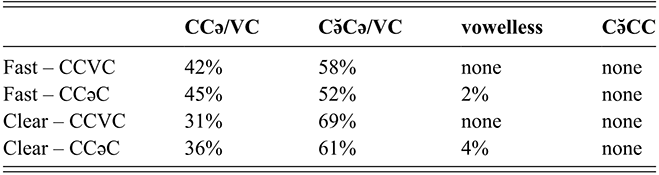

Our first analysis investigated whether we did in fact elicit two distinct speaking modes from Tarifit speakers. At the sentence level, we measured each utterance’s speech rate (average number of syllables per second) with a Praat script (de Jong et al., Reference de Jong, Pacilly and Heeren2021) to assess differences in speaking rate across word reading list conditions. In making this calculation, the script also automatically parses each sentence into syllables, defining syllables as spectral intensity peaks preceded and followed by dips in intensity (peaks that are not voiced are not calculated as syllable nuclei) (de Jong et al., Reference de Jong, Pacilly and Heeren2021). This is also a useful measure for our current analyses, as we are interested in whether the same utterances produced across fast and clear speech styles contain different prosodic structures as a result of vowel insertion processes. For instance, one clear speech strategy could be to slow down all segments in an utterance; an alternative, but not mutually-exclusive strategy, could be to insert additional segmental units and increase the amount of syllabic content in the speech signal. Therefore, we analyze syllable counts for each utterance across styles as well. Table 2 provides the mean and standard deviations for speaking rate and syllable counts across fast and clear speech.

| Speech rate | Number of syllables | |

|---|---|---|

| Fast | 3.2 (0.8) | 4.8 (1.8) |

| Clear | 2.9 (0.8) | 5.4 (1.5) |

We ran two separate mixed effect linear regression models on speech rate and number of syllables. (All the details about each model reported in this Element – including the model output and (g)lmer syntax – are provided in the Online Appendix www.cambridge.org/Afkir_Zellou.) The speech rate model (Online Appendix B.1 www.cambridge.org/Afkir_Zellou) computed a significant effect of speaking style (est. = 0.1, p < 0.01): Tarifit speakers produced a faster speaking rate in our fast speech condition, and slower speech rate in the clear speech condition. The number of syllables per utterance model (Online Appendix B.2 www.cambridge.org/Afkir_Zellou) also revealed a significant effect of speech style (est. = -0.3, p < 0.05): despite the fact that our task provided speakers with the same sentences in each task, speakers produced more syllables per utterance in the clear speech than in the fast speech style.

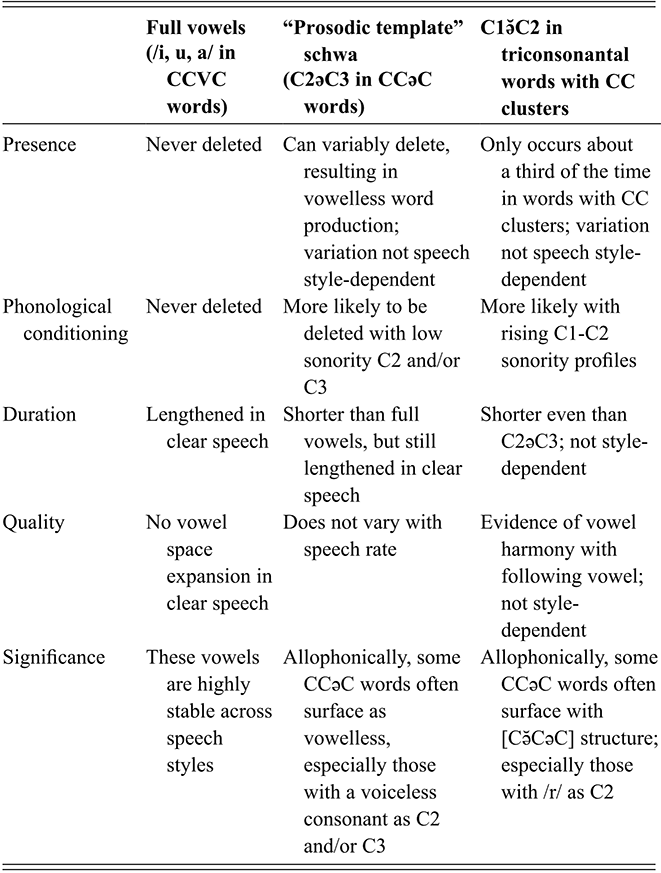

4.2 Vowel Variation in Triconsonantal Words

This section presents an analysis of the acoustic properties of CCəC and CCVC words in Tarifit across different speech styles.

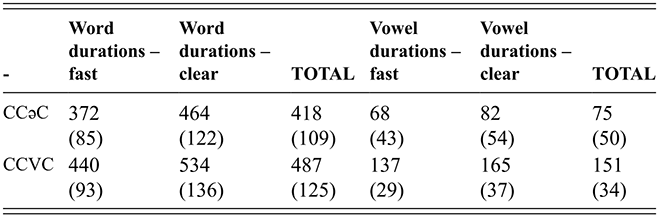

4.2.1 Vowel Changes Across Clear and Fast Speech

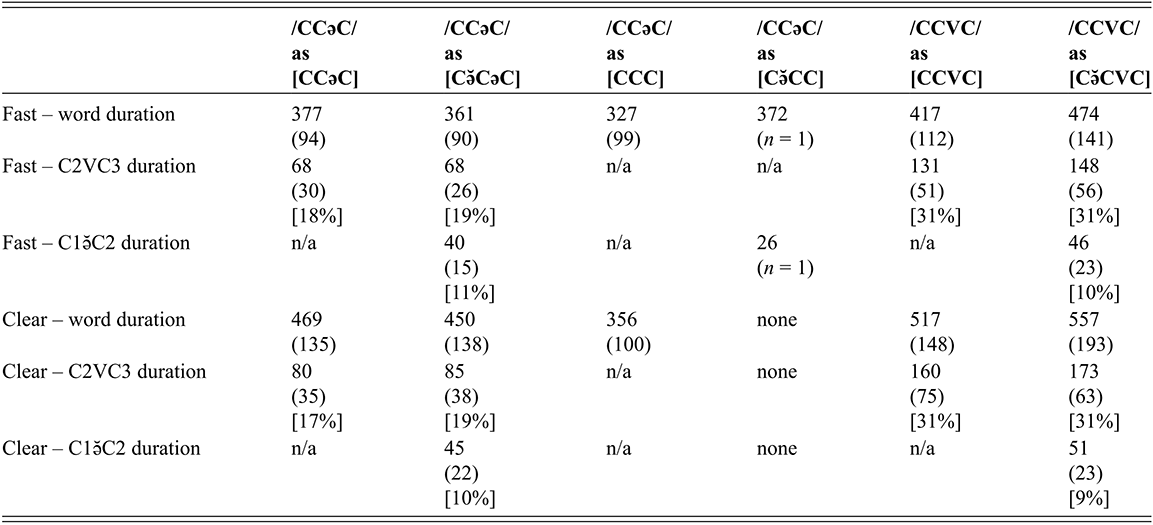

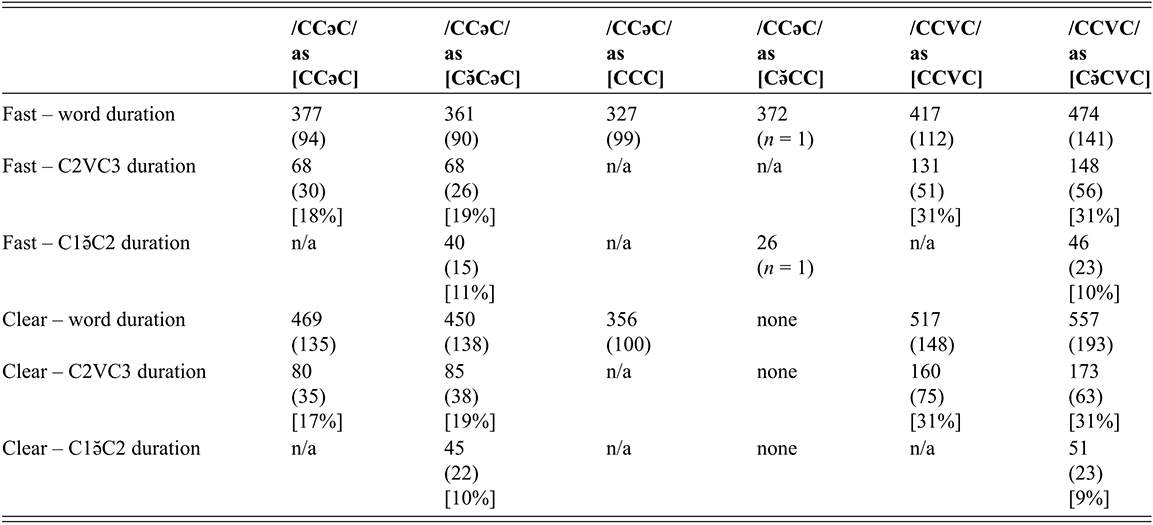

Table 3 presents the average vowel and word durations (and standard deviations) for CCəC and CCVC words across clear and fast speech modes. Overall, clear speech contains longer vowel durations for both CCəC and CCVC words (Online Appendix B.3 www.cambridge.org/Afkir_Zellou, significant main effect of style, est. = -0.04, p < 0.05). This is consistent with crosslinguistic work showing that clear speech contains slower and longer segment durations (Picheny et al., Reference Picheny, Durlach and Braida1986; Krause & Braida, Reference Krause and Braida2002; Smiljanić & Bradow, Reference Smiljanić and Bradlow2005). Comparing across word types, we observe that CCVC words are longer than CCəC, and this can be accounted for by the longer vowels in the former word form (a significant main effect of word type on vowel duration (est. = 0.2, p < 0.001)). Numerically, full vowels in CCVC words are twice as long as schwa in CCəC words, and this ratio is maintained across clear and fast speaking styles (with no significant interaction between style and word type, p = 0.08).

| - | Word durations – fast | Word durations – clear | TOTAL | Vowel durations – fast | Vowel durations – clear | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCəC | 372 (85) | 464 (122) | 418 (109) | 68 (43) | 82 (54) | 75 (50) |

| CCVC | 440 (93) | 534 (136) | 487 (125) | 137 (29) | 165 (37) | 151 (34) |

We can also consider these values as a ratio of vowel to word duration in order to investigate what proportion of each word consists of the vowel for each word type and how that changes across speaking style. For CCəC words, the schwa takes up 18.2% of the word duration in fast speech and 17.6% in clear speech. For CCVC words, the vowel takes up 31.1% of the word duration in fast speech and 30.8% in clear speech. This shows how vowels take up a larger proportion of word duration in CCVC words than in CCəC words, and this is maintained across clear and fast speaking styles.

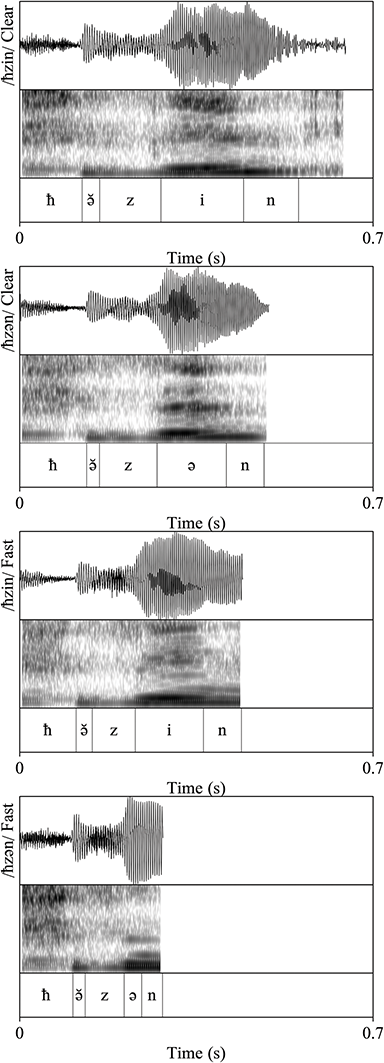

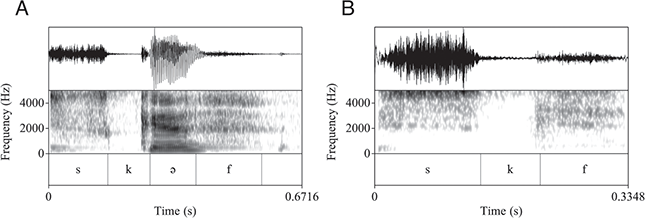

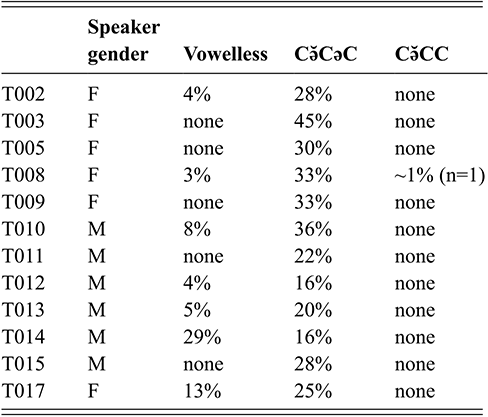

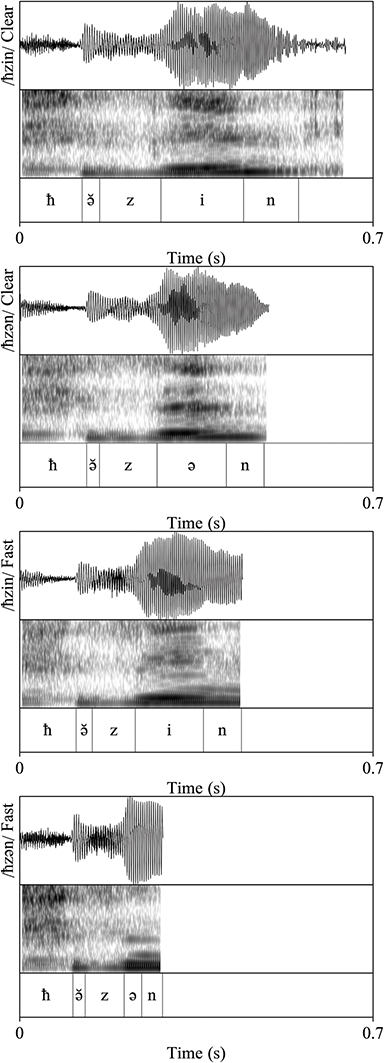

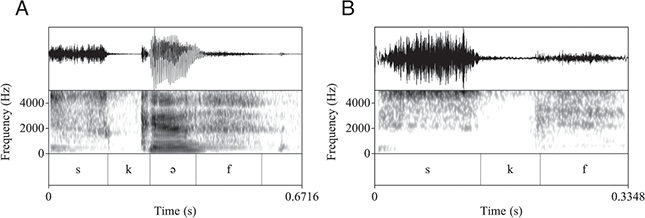

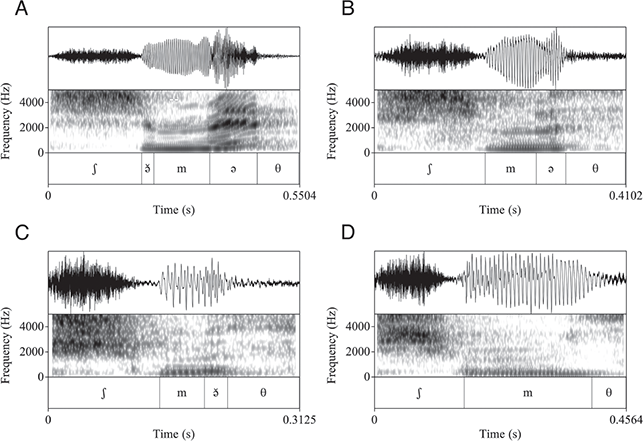

The durational patterns of the grand means of the two different word types across speaking styles can be observed in Figure 10, which provides waveforms, spectrograms, and segmentations for a CCVC-CCəC minimal pair spoken by one speaker in clear and fast speech. While both words and segments get shorter in fast speech, the whole word and vowel durations of /ħzin/ (CCVC structure) are longer than /ħzən/ (CCəC structure) in both clear and fast speech.

Figure 10 Waveforms and spectrograms of the words /ħzin/ (CCVC structure) and /ħzən/ (CCəC structure) in clear and fast speech.

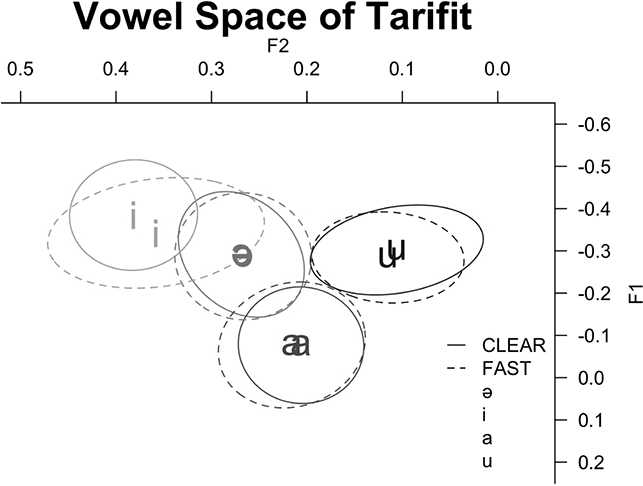

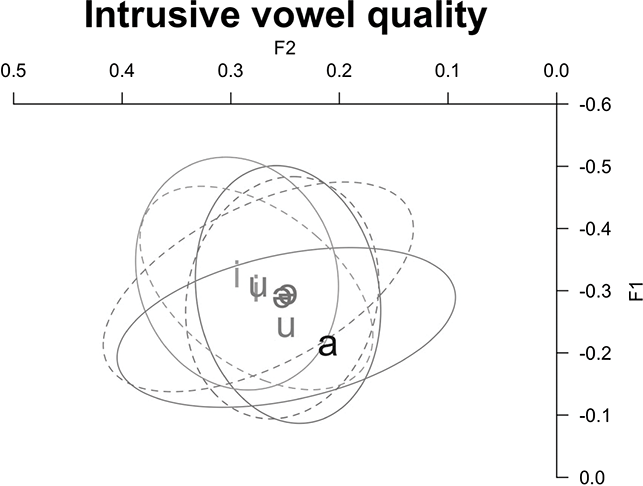

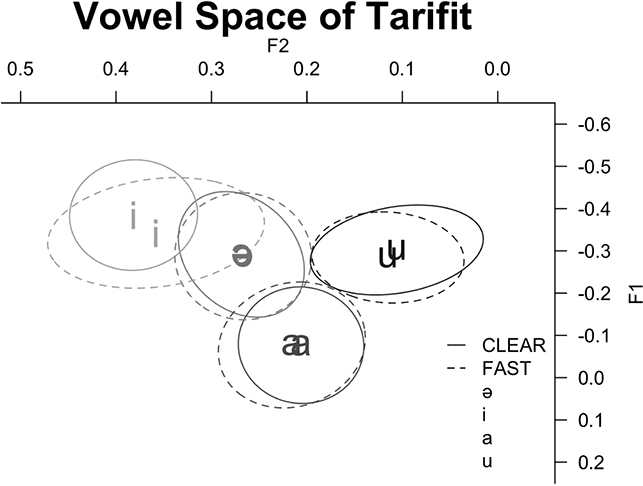

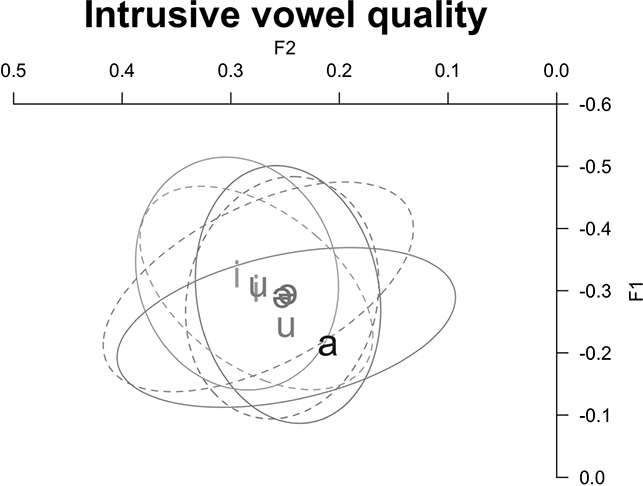

Next, we examine vowel quality. Figure 11 is a plot of F1 and F2 provided in log mean normalized values at midpoint for vowels in CCəC and CCVC words across fast and clear speech modes. The full vowels are appropriately located in the corners of the vowel space and distinct in quality from the mid-central schwa. The schwa, here the “prosodic template” vowel between C2 and C3, remains in the center of the vowel space and does not overlap with the other vowel categories. Thus, four distinct vowel qualities are produced by Tarifit speakers. Comparing across speech modes, there is substantial consistency within each vowel quality across the different speaking styles – the ellipses across clear and fast speech for each vowel are largely overlapping.

Figure 11 Vowel plot of mean and ellipses (95% confidence interval) for log mean normalized formant values for full vowels (/i, u, a/) in CCVC words and schwa in CCəC words across clear (solid lines) and fast (dotted lines) speaking styles.

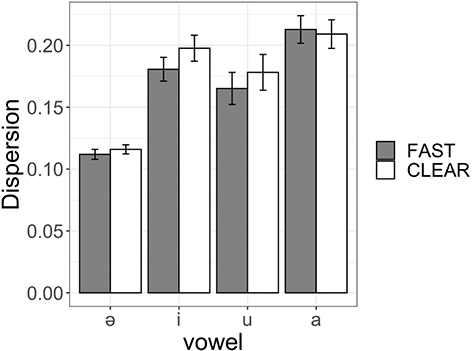

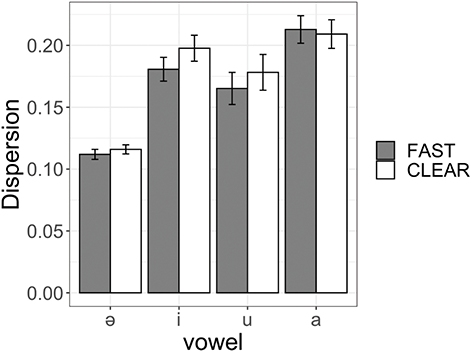

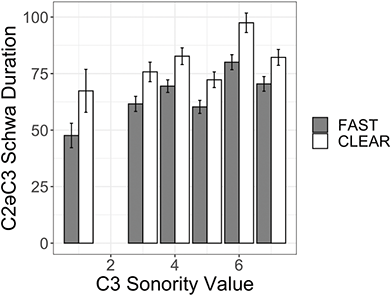

We investigate whether Tarifit speakers produce vowel space hyper-articulation in clear speech. Hyper-articulation (also known as vowel dispersion) can be measured as acoustic distance in F1-F2 space from the vowel space center for each person (Bradlow et al., Reference Bradlow, Torretta and Pisoni1996; Wright, Reference Wright1997). Distance from vowel space center was calculated for each token from log mean normalized F1 and F2 values. The Euclidean distance from vowel space center was calculated for each midpoint measurement, in log mean normalized F1-F2 space for each talker. Figure 12 plots mean dispersion values for /i, u, and a/ in CCVC words and schwa in CCəC words across clear and fast speaking styles.

Figure 12 Mean and standard error values for Euclidean distance from vowel space center for vowels in CCVC (/i, u, a/) and CCəC (/ə/) words across clear and fast speaking styles.

We modeled Euclidean distance values using a mixed effects linear regression. The model included fixed effects of style (fast vs. clear) and vowel type (i, u, a, ə). We also included vowel duration (log) as a fixed effect predictor. The model included by-speaker and by-word random intercepts, as well as by-speaker random slopes for style and vowel type. (The summary statistics are provided in Online Appendix B.4. www.cambridge.org/Afkir_Zellou) The model computed only an effect for vowel type: /i/, /u/ and /a/ are more dispersed from vowel space center than /ə/ (for all comparisons: est. = 0.1, p < 0.05). There was no effect of speaking style on vowel dispersion values (p = 0.9). Nor were there any interactions with speaking style and vowel types on vowel space expansion (all p > 0.05).

Previous crosslinguistic work has shown that vowel space expansion (using the same Euclidean distance measure calculated in the present study) is observed in clear speech to similar magnitudes across different languages, such as similar vowel space expansion in clear speech in Croatian and English (Smiljanić & Bradlow, Reference Smiljanić and Bradlow2007). Yet, in our dataset, we find that Tarifit speakers do not produce more vowel space hyper-articulation in clear speech. They increase vowel duration in clear speech, but vowel space positioning is not altered.

4.2.2 Distribution of Schwas in CCəC Words

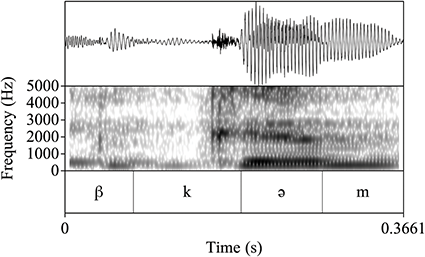

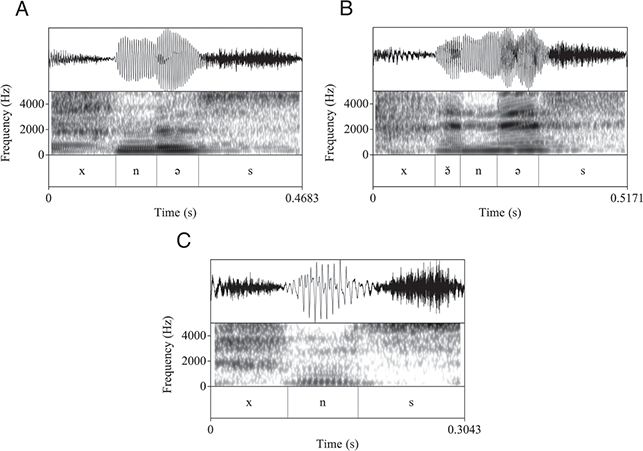

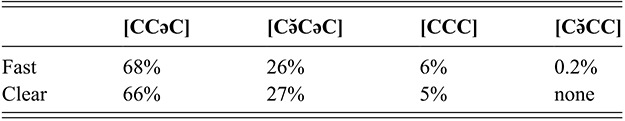

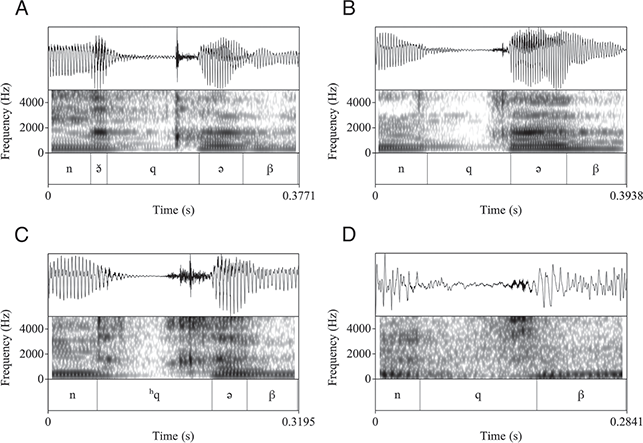

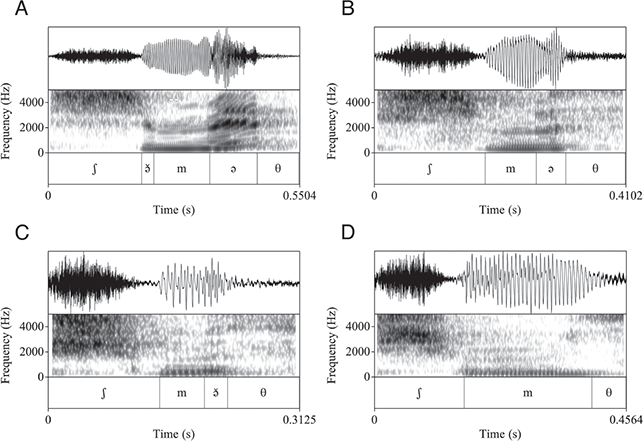

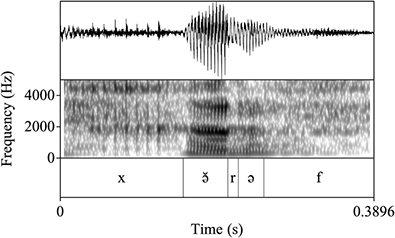

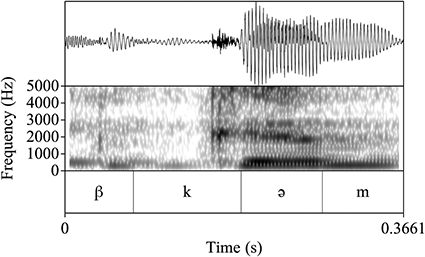

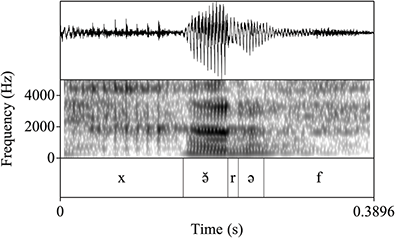

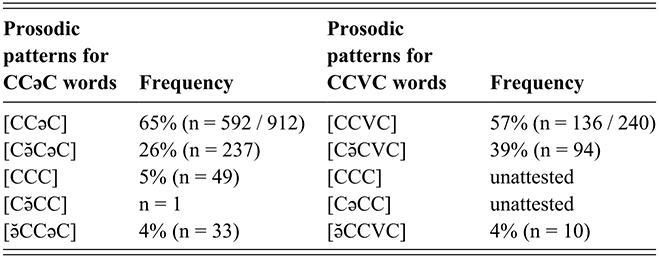

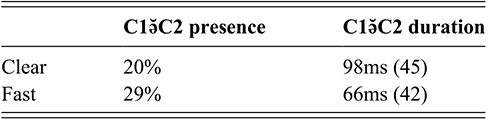

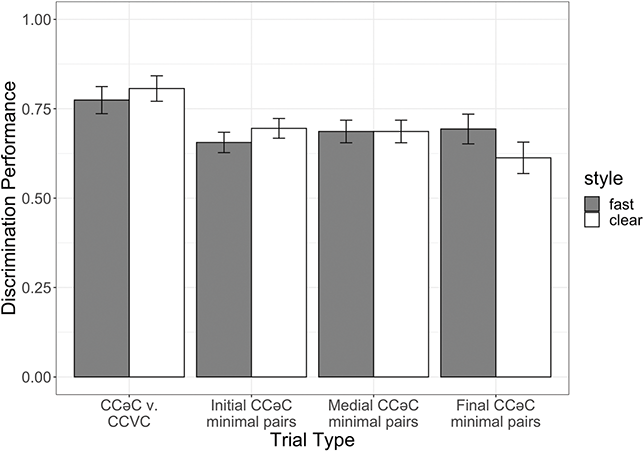

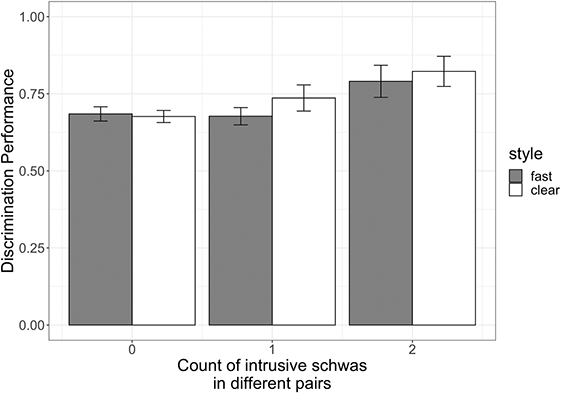

As outlined in Section 2, most Tarifit triconsonantal words containing no full vowels are produced with a schwa between C2 and C3 in the simple imperative form. (Here, we refer to this vowel as C2əC3, but we also refer to it as the “prosodic template” schwa since it occurs as a vocalic melodic for this verbal conjugation.) Yet, we will illustrate that there is substantial variation in the realization of schwas in these word types. Triconsonantal words are most often produced as [CCəC], what we consider the “canonical” prosodic pattern for this inflectional form. This is illustrated in the spectrogram for the word /βkəm/ in Figure 13.

Figure 13 Waveform and spectrogram of /βkəm/ [βkəm].