Introduction

The past three decades have witnessed the marketisation of social sector organisations around the world. The marketisation of the social sector means that non-profit organisations becoming “more market driven, client driven, self-sufficient, commercial or business like’’ (Dart Reference Dart2004, p. 414). This research defines the marketisation of social sector organisations as “social marketisation”. Basically, social marketisation refers to the tendency of using entrepreneurial and marketised strategies by third sector organisations in their survival, growth, and interactions with the government. It includes two indicators: social entrepreneurship and achieving government contracts for purchasing services.

Traditionally, social sector organisations primarily rely on donations or giving. A new phenomenon is emerging and growing, whereby an increasing number of third sector organisations are developing their own funding streams by selling products or services to customers, corporations, foundations, or the government. This phenomenon is important, because it indicates that social organisations are devising their own solutions, in the form of professional services, to address social problems or meet social demands. As a consequence, the proportion of their service income out of the overall revenue is growing. When the commercial income increases significantly (usually more than 35% or 50%), a social sector organisation has transformed into a social enterprise (Han Reference Han and Xu2013). What distinguishes social enterprises from for-profit enterprises is the way in which they use their profits. Social enterprises devote a significant proportion (usually 50% or more) of their profits to pursue social or environmental goals, rather than 100% shared by their shareholders (Han Reference Han and Xu2013).

Meanwhile, government procurements of services from third sector organisations have emerged and spread. Government procurement of services can create a market-based mechanism and a relatively equal playing field for social organisations to compete with each other in providing services and addressing social issues. Theoretically, the achievement of government contracts thus more relies on social organisations’ performance in solving social problems and meeting social demands, and less on their backgrounds or government ties.

Regarding the impact of the two new phenomena, existing literature claims that the marketisation of the social sector threatens or harms creating or maintaining a strong civil society (Eikenberry Reference Eikenberry2009; Eikenberry and Kluver Reference Eikenberry and Kluver2004; Nickel and Eikenberry Reference Nickel and Eikenberry2009). One of the reasons is that marketisation makes social sector organisations reduce their time and efforts on advocacy for public goods, but increase emphases on management concerns and short-term profitability (Eikenberry Reference Eikenberry2009, p. 137). This research, however, suggests that the tendency of social marketisation may strengthen the development of civil society, because it can enhance the involvement of third sector organisations on government policy making and improves the level of their influence on government policies.

There is a good reason to expect that social marketisation is positively related to a higher level of policy influence of third sector organisations. In a modern society, as social problems and social demands emerge and develop, social organisations can design and undertake professional services, as their unique solutions, to address complex social issues. As their service income grows and when they devote their half or more profits to addressing social issues, social organisations can address social problems in a more sustained and effective way. When they address social issues sustainably and effectively, they are more likely to make a difference to these issues. When social organisations garner the evidence that their solutions are effective in addressing social issues, or in other words they have created positive social change, they can use the evidence of positive social change to persuade the government, either directly or indirectly, to change its attitudes, behaviours, or policies. Therefore, the seemingly service-oriented marketisation process in the social organisation sector may, in the end, enhance the influence of third sector organisations on the related government policies on the social issues.

This research focuses on third sector organisations in the UK. The UK is the earliest and still a leading country in the development of social marketisation. Since the 1980s, the UK government has created many policies to foster efficient markets for third sector organisations to deliver public goods and services (Newman Reference Newman2007). In 2001, the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) set up a Social Enterprise Unit to provide support for social enterprises. This unit was incorporated into the Office for the Third Sector (OTS) in 2006, which was re-titled as the Office for Civil Society in the Cabinet Office in 2010 (Hall, Alcock and Millar Reference Hall, Alcock and Millar2012). In 2002, the national umbrella body, Social Enterprise UK, has been established. In 2005, the Community Interest Company (CIC) was set up as a new legal category for the registration of social enterprises in the UK. In 2009, the Department of Health established the Social Enterprise Investment Fund (SEIF) to assist social enterprises in delivering health and social care services. In 2010, all major parties in the UK announced support for the development of social enterprises. After the election 2010, Prime Minister David Cameron launched the “Big Society” scheme, one of its core strategies is to enhance the role of charities, social enterprises, and voluntary organisations in addressing social issues and meeting social demands. In 2011, the world’s first Social Impact Bond appeared in Britain. In 2012, Big Society Capital was launched in London. In 2013, Social Value Act was promulgated, Social Stock Exchange was founded, and G8 Social Investment Task Force was set up. The rapid development of social enterprises and financial support from the government made the UK become one of the best places to test the social marketisation thesis.

The following section of this article is organised as follows. Firstly, it reviews the literature on the factors affecting the policy influence of third sector organisations on government policies. Next, it presents the data used in this research and the measurements of dependent and independent variables. Finally, this research reports the results, draws the conclusion, and discusses the contribution and weakness of this research.

Literature Review

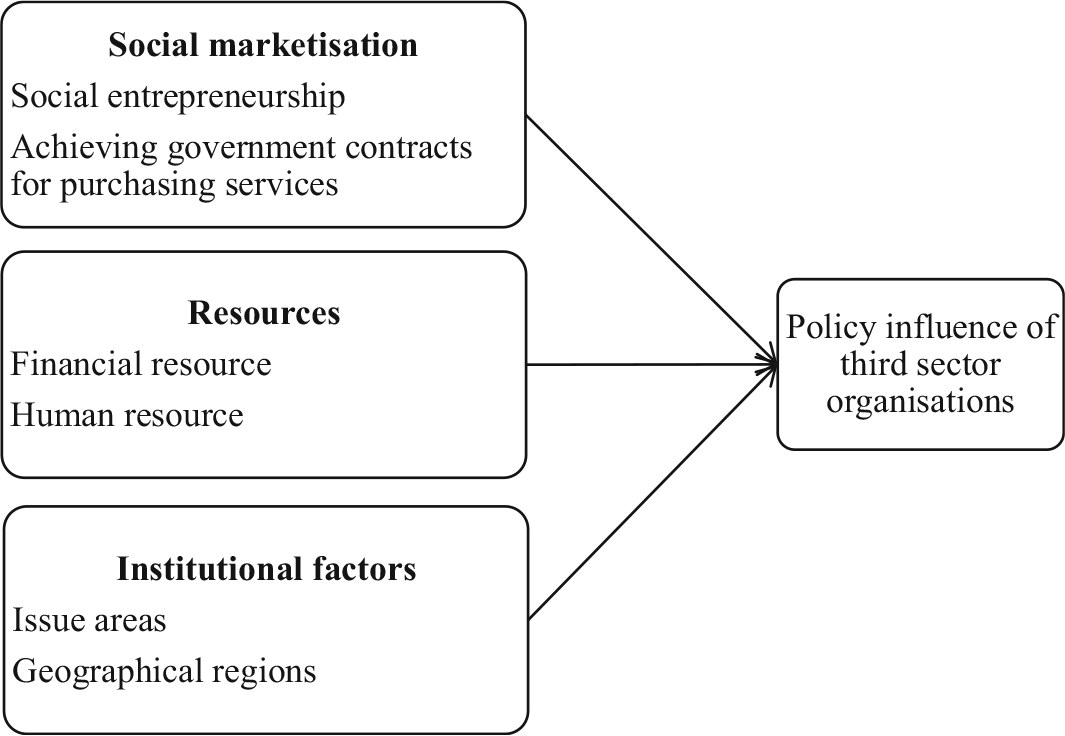

Based on the proposed hypothesis and existing literature, this research identifies three groups of factors to estimate the level of influence of third sector organisations on government policies. The three groups of factors are (1) social marketisation, (2) resources, and (3) institutional factors.

(1) Social Marketisation

As aforementioned, social marketisation refers to entrepreneurial and marketised strategies that social organisations use to survive, thrive, and interact with the state. It includes social entrepreneurship and achieving government contracts for purchasing services.

Social entrepreneurship means drawing upon business techniques to address social problems and create sustainable social changes (Dees Reference Dees1998; Nicholls Reference Nicholls2006). Social enterprises play a significant role in the social sector, by creating and sustaining social values, not only economic values (Dees Reference Dees1998). What distinguishes social enterprises from other social sector organisations is the generation of commercial income. Commercial income may include “program service fees, the sale of products not directly associated with the charitable activity, contracts to deliver services on behalf of a third party, profits from for-profit subsidiaries, and fees for endorsing products” (McKay et al. Reference McKay, Moro, Teasdale and Clifford2015, p. 340). Similarly, according to Salamon (Reference Salamon1993) and Young et al. (Reference Young, Salamon, Grinsfelder and Salamon2012), the substantial growth of service fees and sales as an income source of non-profit organisations is a significant dimension of the marketisation of the non-profit sector. McKay et al. (Reference McKay, Moro, Teasdale and Clifford2015) define the marketisation of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as substituting grants and donations with commercial revenue. Weisbrod (Reference Weisbrod2000) also notes that non-profit organisations are mimicking private firms, and there is a shift in the financial dependence of social organisations from charitable donations to commercial sales activities.

Not all social sector organisations that generate commercial revenue are social enterprises. How to use the profits is the key. According to one of the qualification criteria set by an SE certification agency in the UK (the Social Enterprise Mark), “over 50% of the profits generated from commercial activities are dedicated to social purposes” distinguishes a social enterprise from a business (100% profit distribution).Footnote 1 Therefore, only when social sector organisation uses 50% or more of the surpluses or profits to further the social or environmental goals, it can be regarded as a social enterprise (Han Reference Han and Xu2013).

The second dimension of social marketisation is achieving government contracts for purchasing services. Contract-based relations with the government are different from co-optation or corporatist relations. In the corporatist arrangement, social organisations receive government grants and subsidies, depending on their “singular, compulsory, non-competitive” status and leadership co-optation (Schmitter Reference Schmitter1974, pp. 93–94). In government procurement of services, SOs compete with each other, and there are no organisations enjoying monopolistic status in interest representation and resource distribution. Achieving government contracts thus relies more on the capacity and performance of the organisation in tackling social problems and meeting social demands, and less on their background or government ties.

Signing contracts with the government in solving social problems and meeting social demands can help establishing an institutional channel of information exchange and mutual learning between social sector organisations and the government. Social organisations can use this channel to inform the government how they address social issues and how well they address them. When the government perceived that the approaches or solutions of social organisations are effective in alleviating social problems, it becomes more willing to adopt similar approaches, or to help scale up the effective solutions from social sector organisations to address the social issues. The consequence is that the level of involvement and influence of social sector organisations is improved in the process. Based on the notion of social marketisation, this paper proposes Hypothesis 1: Social marketisation is positively related to the level of influence of third sector organisations on government policies.

(2) Resources

According to resource mobilisation theory (Jenkins Reference Jenkins1983; McAdam et al. Reference McAdam, McCarthy, Zald and Neil1988; McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977), social actors require and mobilise personnel, financial, and other resources to carry out activities and pursue their goals. Likewise, resource dependence theory (Aldrich and Pfeffer Reference Aldrich and Pfeffer1976; Aldrich Reference Aldrich1979; McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977; Pfeffer and Salanick Reference Pfeffer and Salanick1978) believes that organisations rely on resources—funding, people, information, and even recognition—from the external world to survive and thrive. Therefore, resources from the external environment play a significant role in shaping organisational decisions and behaviours, including their policy influence.

It is reasonable to expect that social organisations with more resources have a higher level of influence on government policies. Extant literature has shown that the availability of financial and human resources enhances collective actions (Andrews and Edwards Reference Andrews and Edwards2004). The scope and intensity of advocacy activities are greater in organisations with larger budgets and larger staff size (Bass et al. Reference Bass, Arons, Guinane, Carter and Rees2007; Child and Grønbjerg Reference Child and Grønbjerg2007; Donaldson Reference Donaldson2007; Mosley Reference Mosley2010; Nicholson-Crotty Reference Nicholson-Crotty2007). Conversely, the lack of resources is a primary barrier to conduct advocacy activities and to pursue policy changes (Almog-Bar and Schmid Reference Almog-Bar and Schmid2014; Bass et al. Reference Bass, Arons, Guinane, Carter and Rees2007).

Based on the existing literature, this research identifies two main resources social sector organisations have in affecting government policies, financial resources and human resources. Financial resources are the scale of income of the organisation. Human resources are the size of full-time staffs and part-time volunteers of the organisation. The research of Schmid et al. (Reference Schmid, Bar and Nirel2008), for example, has indicated that the larger number of volunteers in the organisation, the greater political influence the organisation has. Financial and human resources are thus expected to have positive associations with the level of social organisations’ influence on government policies. Based on resource dependence theory and resource mobilisation theory, this paper expects Hypothesis 2: Financial resources and human resources are positively related to the level of influence of third sector organisations on government policies.

(3) Institutional factors

In addition to resources, institutional factors are essential for social organisations to influence government policies. Neo-institutional theory highlights the role of a broader institutional environment. Neo-institutional theory posits that organisational structures and behaviours are largely shaped by the institutional or normative environment, instead of just reflecting resource dependencies or being determined by organisational strategies (DiMaggio and Powell Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983; Meyer and Rowan Reference Meyer and Rowan1977; Meyer and Scott Reference Meyer and Richard Scott1983; Powell and DiMaggio Reference Powell and DiMaggio1991; Scott Reference Scott2004; Scott and Christensen Reference Scott and Christensen1995; Scott et al. Reference Scott and John1994; Zucker Reference Zucker1987). In order to survive and grow, organisations have to conform to the rules, norms, values, standards, and expectations prevailing in the institutional environment.

When organisations are subject to largely the same institutional environment, they become increasingly similar to one another over time, or become “isomorphic”. DiMaggio and Powell (Reference DiMaggio and Powell1983) distinguish three mechanisms of isomorphic pressures (coercive, mimetic, and normative isomorphism). Similarly, Scott summarises “three pillars” of institutionalisation—regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive. The regulative pillar consists of rules, laws, and sanctions, the normative pillar involves certification and accreditation, and the cultural-cognitive pillar includes common beliefs and shared logics of action (Scott Reference Scott2001, p. 52).

Social organisations working in the same issue area confront almost the same institutional environment. Social organisations working in different issue areas do not equally engage in activities to influence government policy, and their level of policy influence thus may vary. For example, Child and Grønbjerg (Reference Child and Grønbjerg2007) indicate that non-profit organisations working in the fields of environment, health, and mutual benefits are more likely to engage in advocacy than human service organisations. Suárez and Hwang (Reference Suárez and Hwang2008) reveal that environmental organisations, civil rights groups, parent–teacher organisations (education), and hospitals (health) are more likely to lobby the government than organisations in other fields. Baumgartner and Leech (Reference Baumgartner and Leech2001) also find that interest groups tend to focus on a small number of issues. Therefore, social organisations working in different issue areas are expected to have different levels of policy influence.

The geographical region of operation is the second salient institutional factors. Some third sector organisations carry out their activities at the international level, some undertake activities nationwide, while some work only in the regional or local areas. As noted by Hsu et al. (Reference Hsu, Hsu and Hasmath2016) that resource strategies of NGOs have regional variances, one may expect that the regional differences of policy influence of social organisations also exist. Specifically, social organisations working at the international or national level are expected to be more active than organisations working in the regional, local, or neighbourhood areas. Therefore, based on the neo-institutional theory and existing studies, one may suggest Hypothesis 3: Issue areas and geographical regions affect the level of influence of third sector organisations on government policies.

In sum, based on the social marketisation hypothesis and existing literature as discussed above, this paper builds an analytical framework by combing three groups of factors to examine the level of influence of third sector organisations on government policies, as outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Analytical framework

Data, Variables and Measurements

To test the three hypotheses, this research uses a large-scale survey data from the UK, namely the National Survey of Charities and Social Enterprises (NSCSE). NSCSE, formerly known as the National Survey of Third Sector Organisations (NSTSO), was initiated by the Office for Civil Society of Cabinet Office UK and implemented by Ipsos MORI, Social Research Institute. In 2010, the investigators submitted survey invitations to 112,796 third sector organisations (charities, voluntary organisations and social enterprises) across all 151 single and two-tier authorities in the UK. A total of 44,109 organisations completed the postal or online questionnaire. The overall valid response rate is 41%. The questionnaire was to be completed by the leader of the organisation, a member of the senior management, or a member of the trustee board or management committee. The database NSCSE is now completely open accessed to scholars based in the UK.Footnote 2 More details of NSCSE, including sampling method, data processing, and questionnaire content, can be found in the online technical report.Footnote 3 The following section describes how the variables used in this research are measured in the survey questions.

(1) Three variables of policy influence

In NSCSE, policy influence of third sector organisations is measured by three variables: (1) overall policy influence, (2) policy involvement, and (3) policy consulting. In terms of overall policy influence, one question in the survey asked: “Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your ability to influence government decisions that are relevant to your organisation? The options are (1) very satisfied, (2) fairly satisfied, (3) neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, (4) fairly dissatisfied, (5) very dissatisfied, (6) don’t know, and (7) not applicable” (Q22 in the survey). The answers to options 1 to 5 are coded from five to one, respectively. A higher score means a higher level of policy influence.

In terms of policy involvement, one question in the survey enquired: “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements: local statutory bodies in your local area involve your organisation appropriately in developing and carrying out policy on issues which affect you? (1) Strongly agree, (2) tend to agree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) tend to disagree, (5) strongly disagree, (6) don’t know, and (7) not applicable” (Q21 in the survey). The answers to options 1 to 5 are coded from five to one, respectively. A higher score means a higher level of policy influence.

In terms of policy consulting, the survey asks: “To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements: local statutory bodies consult your organisation on issues which affect you or are of interest to you? (1) Strongly agree, (2) tend to agree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) tend to disagree, (5) strongly disagree, (6) don’t know, and (7) not applicable” (Q21 in the survey). The answers to options 1 to 5 are coded from five to one, respectively. A higher score means a higher level of policy influence.

(2) Social marketisation

In NSCSE, social entrepreneurship is measured by key variables: whether the organisation use the profit or surplus generated in their commercial activities to pursue social goals. The question in the survey asks: “If your organisation does generate a surplus or profit from its contracts or trading, do you use it to further your social or environmental goal? This could include reinvesting it in your or another charity, social enterprise and/or voluntary organisation or in the community. Options are (1) yes—we use up to 50% of the surplus/profit, (2) yes—we use 50% or more of the surplus/profit, (3) not applicable—we do not make a surplus/profit, (4) no, and (5) don’t know” (Q37 in the survey). Answers to option two are coded as one, and otherwise as zero.

Achieving government contracts for purchasing services is based on one question in the survey: “How successful, or not, have you been in applying for funding or bidding for contracts from local statutory bodies over the last 5 years?Footnote 4 Options are (1) very successful, (2) fairly successful, (3) not very successful, (4) not at all successful, (5) have never applied/bid, and (6) don’t know” (Q15 in the survey). Answers to options 1 and 2 are coded as one, answers to options 3–5 are coded as zero, and answers to option 6 are coded as missing values.

(3) Resources

In NSCSE, financial and human resources are measured by three variables: income size, staff size, and volunteer size. In terms of income size, one question in the survey asked: “Please indicate below your organisation’s approximate annual total turnover or income from all sources” (Q33 in the survey). The answers to this question are coded from 1 to 24, based on the size of the income.Footnote 5 A higher score means a larger size of income.

In terms of staff size, one question requested: “Please tell us the approximate number of full-time equivalent employees currently in your organisation” (Q30 in the survey). The answers of no employees are coded as 1, the answers of one employee are coded as 2, two employees are coded as 3, 3–5 employees are coded as 4, 6–10 employees are coded as 5, 11–30 employees are coded as 6, 31–100 employees are coded as 7, and 101 plus employees are coded as 8. No answers are coded as missing values. A higher score means a larger size of full-time employees.

In terms of volunteer size, the question enquired: “Please tell us the approximate number of volunteers, including committee/board members, that your organisation currently has” (Q31 in the survey). No volunteers are coded as 1, 1–10 volunteers are coded as 2, 11–20 volunteers are coded as 3, 21–30 volunteers are coded as 4, 31–50 volunteers are coded as 5, 51–100 volunteers are coded as 6, 101–500 volunteers are coded as 7, 501 plus are coded as 8. No answers are coded as missing values. A higher score means a larger group of volunteers in the organisation.

(4) Institutional factors

In NSCSE, institutional factors include issue areas and geographic areas. In terms of issue areas, one question asked: “Which are the main areas in which your organisation works? (Q4 in the survey) Options are: (1) community development and mutual aid, (2) cohesion/civic participation, (3) culture (including arts and music), (4) leisure (including sports and recreation), (5) economic well-being (including economic development, employment and relief of poverty), (6) accommodation/housing, (7) education and lifelong learning, (8) training, (9) environment/sustainability, (10) equalities/civil rights (e.g. gender, race, disabilities), (11) heritage, (12) health and well-being, (13) international development, (14) religious/faith-based activity, (15) criminal justice, (16) animal welfare, (17) capacity-building and other support for charities, (18) other charitable, social or community purposes.” These options are coded from 1 to 18, respectively.

For geographic areas, the question in the survey enquired: “Which one is the main geographic area in which your organisation carries out its activities? (1) Internationally, (2) nationally, (3) regionally, (4) your local authority area, (5) your neighbourhood, or (6) cannot say” (Q8 in the survey). The answers to options 1–5 are coded from five to one, respectively, and answers to option 6 are coded as missing values.

Results

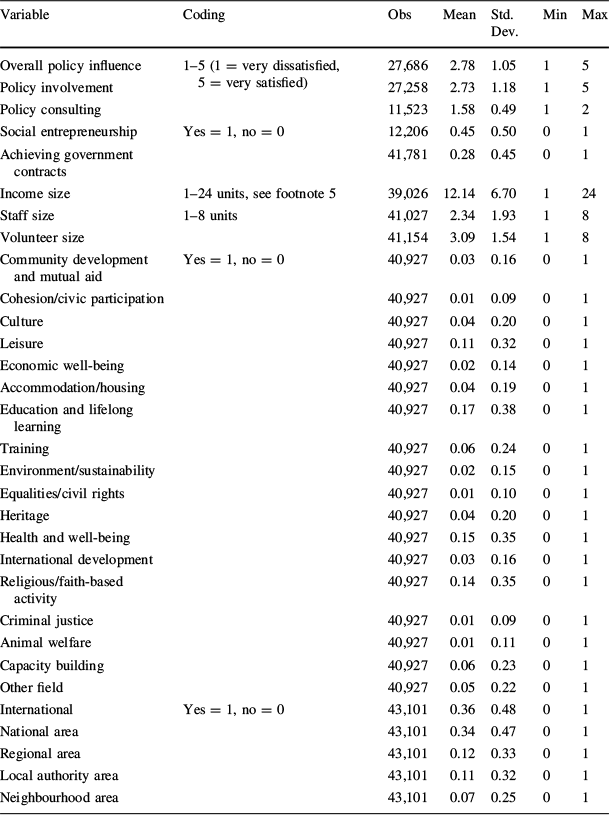

Table 1 reports the coding methods and descriptive statistics of all variables used in this research. The data of NSCSE reveals that, on average, the satisfaction of third sector organisations on their policy influence is 2.8 (1–5 scale). 2.1% of third sector organisations in the UK were very satisfied with their ability to influence policy. 14.3% of third sector organisations are fairly satisfied with their ability to influence policy. 22.5% of third sector organisations neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

Table 1 Coding methods and descriptive statistics of all variables

|

Variable |

Coding |

Obs |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min |

Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Overall policy influence |

1–5 (1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied) |

27,686 |

2.78 |

1.05 |

1 |

5 |

|

Policy involvement |

27,258 |

2.73 |

1.18 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

Policy consulting |

11,523 |

1.58 |

0.49 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Social entrepreneurship |

Yes = 1, no = 0 |

12,206 |

0.45 |

0.50 |

0 |

1 |

|

Achieving government contracts |

41,781 |

0.28 |

0.45 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Income size |

1–24 units, see footnote 5 |

39,026 |

12.14 |

6.70 |

1 |

24 |

|

Staff size |

1–8 units |

41,027 |

2.34 |

1.93 |

1 |

8 |

|

Volunteer size |

41,154 |

3.09 |

1.54 |

1 |

8 |

|

|

Community development and mutual aid |

Yes = 1, no = 0 |

40,927 |

0.03 |

0.16 |

0 |

1 |

|

Cohesion/civic participation |

40,927 |

0.01 |

0.09 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Culture |

40,927 |

0.04 |

0.20 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Leisure |

40,927 |

0.11 |

0.32 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Economic well-being |

40,927 |

0.02 |

0.14 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Accommodation/housing |

40,927 |

0.04 |

0.19 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Education and lifelong learning |

40,927 |

0.17 |

0.38 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Training |

40,927 |

0.06 |

0.24 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Environment/sustainability |

40,927 |

0.02 |

0.15 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Equalities/civil rights |

40,927 |

0.01 |

0.10 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Heritage |

40,927 |

0.04 |

0.20 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Health and well-being |

40,927 |

0.15 |

0.35 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

International development |

40,927 |

0.03 |

0.16 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Religious/faith-based activity |

40,927 |

0.14 |

0.35 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Criminal justice |

40,927 |

0.01 |

0.09 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Animal welfare |

40,927 |

0.01 |

0.11 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Capacity building |

40,927 |

0.06 |

0.23 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Other field |

40,927 |

0.05 |

0.22 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

International |

Yes = 1, no = 0 |

43,101 |

0.36 |

0.48 |

0 |

1 |

|

National area |

43,101 |

0.34 |

0.47 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Regional area |

43,101 |

0.12 |

0.33 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Local authority area |

43,101 |

0.11 |

0.32 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Neighbourhood area |

43,101 |

0.07 |

0.25 |

0 |

1 |

In terms of policy involvement and policy consulting, the average score of policy involvement is 2.7 (1–5 scale), and the average level of policy consulting is 2.9 (1–5 scale). Specifically, 3.9% of third sector organisations “strongly agree” that they were involved in developing and carrying out policy, and 5.2% of third sector organisations “strongly agree” that they were consulted by the government on issues which affect them or are of interest to them. 13.9% of third sector organisations “tend to agree” that they were involved in developing and carrying out policy, and 18.5% of third sector organisations “tend to agree” that they were consulted by the government on issues which affect them or are of interest to them.

Regarding the two key indicators of social marketisation, the data shows that 44.7% of third sector organisations in the UK become social enterprises, as they devote half or more of their profits or surpluses generated in their commercial activities to pursue social goals. 28.1% of third sector organisations succeeded in bidding for contracts from local statutory bodies over the last 5 years.

In terms of financial and human resources, the average income size of third sector organisations in the UK ranges from 17,501 to 20,000 GBP per year. On average, each organisation has two full-time employees and 11–20 volunteers.

In terms of issue areas, the data shows that, the top five issue areas in which third sector organisations work in the UK are education and lifelong learning (28.8% of all third sector organisations), leisure including sports and recreation (20.2%), health and well-being (17.5%), community development and mutual aid (17.1%), and religious/faith-based activity (14.1%).Footnote 6 In terms of geographical regions, 35.1% of social sector organisations in the UK are working at the neighbourhood, 32.8% are at the local authority area, 12.2% are at the regional level, 11.1% are at the national level, and 6.5% are at the international level, and 2.3% did not answer the question.

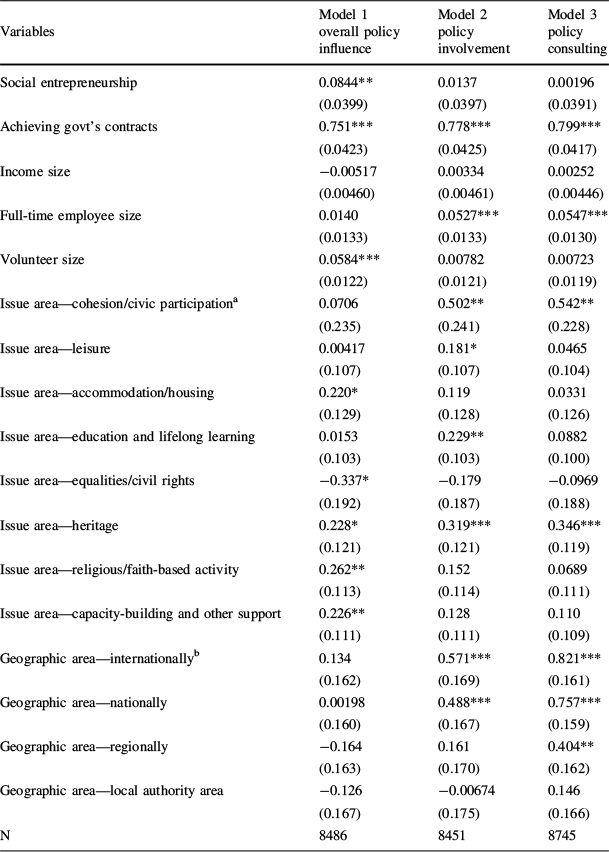

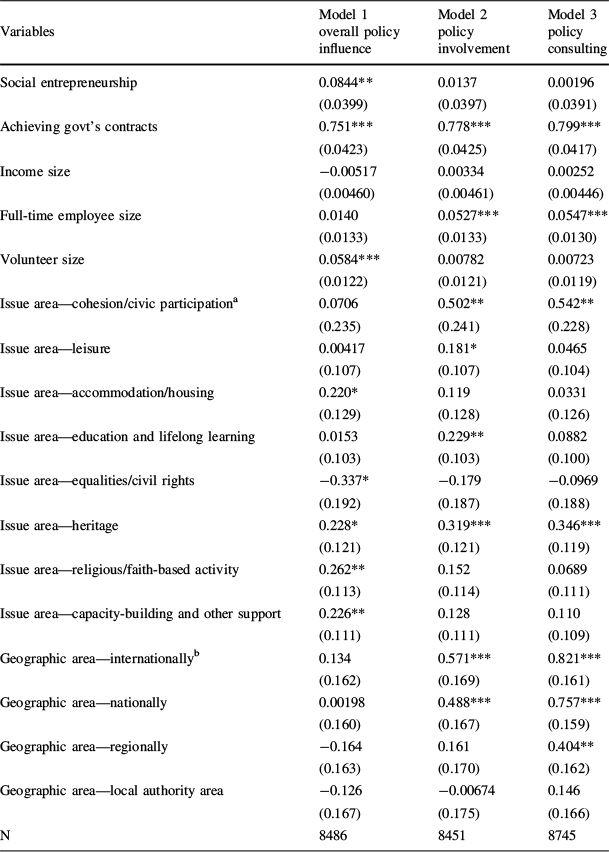

To estimate the three dependent variables measuring the policy influence of third sector organisations in the UK, this research uses three ordered logistic regressions in the statistical estimations, as the two dependent variables are ordinal variables. Before the regression analyses, a correlation analysis was conducted to examine the potential correlations among the independent variables. No high correlations were detected. Table 2 presents the results of the regression analyses and reports statistics of the coefficients in the three models.

Table 2 Regressions on policy influence of third sector organisations in the UK

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Variables |

overall policy influence |

policy involvement |

policy consulting |

|

Social entrepreneurship |

0.0844** |

0.0137 |

0.00196 |

|

(0.0399) |

(0.0397) |

(0.0391) |

|

|

Achieving govt’s contracts |

0.751*** |

0.778*** |

0.799*** |

|

(0.0423) |

(0.0425) |

(0.0417) |

|

|

Income size |

−0.00517 |

0.00334 |

0.00252 |

|

(0.00460) |

(0.00461) |

(0.00446) |

|

|

Full-time employee size |

0.0140 |

0.0527*** |

0.0547*** |

|

(0.0133) |

(0.0133) |

(0.0130) |

|

|

Volunteer size |

0.0584*** |

0.00782 |

0.00723 |

|

(0.0122) |

(0.0121) |

(0.0119) |

|

|

Issue area—cohesion/civic participationa |

0.0706 |

0.502** |

0.542** |

|

(0.235) |

(0.241) |

(0.228) |

|

|

Issue area—leisure |

0.00417 |

0.181* |

0.0465 |

|

(0.107) |

(0.107) |

(0.104) |

|

|

Issue area—accommodation/housing |

0.220* |

0.119 |

0.0331 |

|

(0.129) |

(0.128) |

(0.126) |

|

|

Issue area—education and lifelong learning |

0.0153 |

0.229** |

0.0882 |

|

(0.103) |

(0.103) |

(0.100) |

|

|

Issue area—equalities/civil rights |

−0.337* |

−0.179 |

−0.0969 |

|

(0.192) |

(0.187) |

(0.188) |

|

|

Issue area—heritage |

0.228* |

0.319*** |

0.346*** |

|

(0.121) |

(0.121) |

(0.119) |

|

|

Issue area—religious/faith-based activity |

0.262** |

0.152 |

0.0689 |

|

(0.113) |

(0.114) |

(0.111) |

|

|

Issue area—capacity-building and other support |

0.226** |

0.128 |

0.110 |

|

(0.111) |

(0.111) |

(0.109) |

|

|

Geographic area—internationallyb |

0.134 |

0.571*** |

0.821*** |

|

(0.162) |

(0.169) |

(0.161) |

|

|

Geographic area—nationally |

0.00198 |

0.488*** |

0.757*** |

|

(0.160) |

(0.167) |

(0.159) |

|

|

Geographic area—regionally |

−0.164 |

0.161 |

0.404** |

|

(0.163) |

(0.170) |

(0.162) |

|

|

Geographic area—local authority area |

−0.126 |

−0.00674 |

0.146 |

|

(0.167) |

(0.175) |

(0.166) |

|

|

N |

8486 |

8451 |

8745 |

Standard errors are in parentheses. *** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1

a“Issue area—other” as the reference category. Issue areas that are not statistically significant are omitted

b“Geographic area—neighbourhood” as the reference category

As reported in Table 2, social entrepreneurship is statistically significant in estimating the satisfaction of third sector organisation on their overall influence on government policies. When a social organisation becomes a social enterprise, its overall satisfaction on its policy influence increased 0.08 unit, when other factors are equal.

Achieving government contrasts for purchasing services is statistically significant in the three models. When a social organisation obtained government contracts, its overall policy influence improved 0.75 unit, its level of involving in policy making increased 0.78 unit, and its likelihoods of being consulting by the government increased 0.80 unit, after controlling for other factors. Therefore, the results verify the Hypothesis 1 that the two indicators of social marketisation are positively related to the policy influence of third sector organisations.

In terms of resources, income size does not significantly affect the level of policy influence of third sector organisations. An organisation with more full-time employees is more likely to involve in policy making, and more likely to be consulted by the government. An organisation with more volunteers is more satisfied with its overall influence on government policies. Therefore, the results partially support Hypothesis 2. Financial resources do not significantly affect the policy influence of third sector organisations, while human resources have a positive effect.

In terms of issue areas and geographical regions, the results show that third sector organisations working in the four issue areas (accommodation/house, heritage, religious/faith-based activities, capacity-building and other support) are more satisfied with their overall capacity to influence government decisions. Third sector organisations working in the four issue areas (cohesion/civic participation, leisure, education and lifelong learning, heritage) are more likely to involve in the process of developing and carrying out policies with the government. Social organisations working in the two fields (cohesion/civic participation and heritage) are more likely to be consulted by the government agencies in the UK. Social organisations active at the international or national level are more likely to involve in government policy making and being consulted by the government, than those organisations operated at the neighbourhood level. Therefore, the results support Hypothesis 3, that issue areas and geographical regions affect the level of influence of third sector organisations on government policies.

In sum, the results based on the survey data support the core argument of this research, that is social marketisation is positively related to the policy influence of third sector organisations. When third sector organisations become social enterprises, the level of their perceived policy influence increased. When third sector organisations achieved government contracts for purchasing services, the levels of their overall policy influence, involvement in government policy making, and the chance of being consulted by the government all improved.

Conclusion

The marketisation of social sector organisations or social marketisation emerged and spread around the world in the past three decades. Social entrepreneurship and achieving government contracts for purchasing services are two salient indicators of the new tendency of social marketisation.

In contrast with existing literature which claims that social marketisation makes social sector organisations reduce their efforts on advocacy and thus harms a strong civil society, this research finds that social marketisation is positively related to the influence of third sector organisations on government policies, and thus it can strengthen the development of civil society, rather than erode it.

Based on the National Survey of Charities and Social Enterprises in the UK, the results of regression analyses show that, when other factors are equal, the two indicators of social marketisation, social entrepreneurship and achieving government contracts for purchasing services, are both statistically significant in estimating the level of policy influence of third sector organisations.

Specifically, when a third sector organisation becomes a social enterprise, its satisfaction on its overall influence on government policies increased 0.08 unit, when other factors are equal. When a social sector organisation achieved government contracts, its overall policy influence improved 0.75 unit, the level of involving in policy making increased 0.78 unit, and the likelihoods of being consulting by the government increased 0.80 unit, when other factors are equal. Therefore, the results support the argument that the two indicators of social marketisation strengthen the policy influence of third sector organisations in the UK.

This research has two main contributions to the literature. Firstly, it finds a positive, rather than a negative, relationship between social marketisation and the perceived policy influence of social sector organisations. In contrast with the research claiming marketisation of the social sector threatens civil society in the USA (Eikenberry Reference Eikenberry2009; Eikenberry and Kluver Reference Eikenberry and Kluver2004; Nickel and Eikenberry Reference Nickel and Eikenberry2009), this study suggests that social marketisation in fact can strengthen the development of civil society, by enhancing the policy influence of social sector organisations. Secondly, this research responds to the call to add the diversity to the understanding of policy influence or advocacy in different country contexts, as the majority of the scholarship is based on experiences of social sector organisations in the USA (Almog-Bar and Schmid Reference Almog-Bar and Schmid2014; Ljubownikow and Crotty Reference Ljubownikow and Crotty2015).

The limitation of this study is that the policy influence of third sector organisations is measured by self-perceptions and self-reports. The nuanced forms and processes of influencing government policies are not considered in this research. Readers may also be curious about what policies are influenced and how they are influenced by social sector organisations. This limitation, however, has been extended by other research that explores how two specific social organisations have successfully promoted the emergence of five new government policies in the Chinese context (Han Reference Han2016).