Introduction

The year 2022 started with early general elections strengthening the ruling Socialist Party (PS), which won an absolute majority in the national Parliament. However, it took some time for the new government to learn to govern under such conditions.

Election report

Early general elections of 30 January 2022: A surprising absolute majority for the ruling PS

After the rejection of the 2022 budget by the opposition parties on October 2021, President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa called for early elections, which were scheduled for 30 January 2021. Campaigning lasted throughout the whole of January. The opinion polls gave mixed messages about who would win the elections but still with a strong tendency toward a victory of the ruling PS. Despite a growing erosion of the governmental ability of the ruling PS, voters still did not seem to be convinced about an alternation of power to the main opposition party, the Social Democratic Party (PSD). Most of the electorate did not perceive the PSD leader, Rui Rio, as a strong candidate.

Moreover, the PSD had competition on the right by new dynamic small right-wing parties. The right-wing populist Chega! and the Liberal Initiative (IL) emerged in the 2019 general election and could now carry out a more sophisticated campaign as parliamentary parties. On the left, the Block of the Left (BE) and the Communist Party-the Greens (PCP-PEV) wanted the PS to restore an alliance with them, such as the one forged after the 2015 general elections, which dissipated during the last legislative period (2019–2022).

The PS could count on a now well-experienced Prime Minister, Antonio Costa, who performed well both on the domestic front and on the European stage. Its electoral program featured four main issues. The number one priority was to improve good governance in Portugal, notably by continuing on the path of budgetary and public debt consolidation. The slogan used for this priority was “contas certas” (setting accounts right). Other topics were finding solutions to climate, demographic change, and digitalization. One major constraining factor was the restrictions related to COVID-19. Notably, there was controversy around who was allowed to go to the polling stations and under what circumstances.

The PSD hoped to get the first spot during the campaign, so it acted cautiously in relation to the PS. In case of failure, their second best option was to form a grand coalition, in Portuguese known as Bloco Central (Central Block). Since his election in the primaries of 2018, PSD leader Rui Rio has been a responsible opposition leader trying to find common ground with the ruling PS. However, part of the PSD did not see such a policy as very positive. Despite differences, his rivals Paulo Rangel and Luis Montenegro took part in the campaign and supported Rio. The slogan of the PSD was “New horizons for Portugal,” which focused on the idea of turning Portugal into a much more competitive economy with higher levels of productivity.

The smaller parties on the left were still recovering from the PS's decision not to renew their government agreement after the 2019 election. After years of modest redistribution policy, the PS was pressured by the European Commission to reduce the budget deficit and public debt. However, the two minor parties, the BE and the Communist Party (PCP-PEV), wanted the PS to return to the left-wing parliamentary alliance that became known as “geringonça” (contraption, innovative form of governing). The program of BE, under the slogan “strong reasons, clear commitments,” focused on protecting the environment, achieving higher wages and protecting the health sector. The demands of the Communists were also the rise of salaries through a higher minimum wage, more investment in the health sector and public services, and the fight against deteriorating working conditions.

The Ecological Party of People, Animals, and Nature (PAN) started the elections quite divided. Its leader, Inês Sousa Real, pursued a strategy of equidistance to PS and PSD. Nevertheless, such an approach was contested by part of the party leadership, which wanted a stronger commitment to a potential coalition with the PS. There was a general hope from her side to become part of the government if the PS did not achieve the absolute majority.

The micro party Livre (Free), whose leader was Rui Tavares, hoped to regain representation in Parliament. His program focused on a fair socio-ecological transformation in which the weakest groups of the population would be supported.

On the right, the Democratic Social Centre-People's Party (CDS-PP) had a problematic standing, given the proliferation of more small parties. Its leader, Francisco Rodrigues dos Santos, saw survival as the main goal in the context of this new competitive environment.

IL's main slogan was Portugal a crescer (Portugal growing). Its main focus was on making the Portuguese economy more competitive and reducing the state's role in it. For this transformation to happen, IL wanted to facilitate a change in political culture. Apart from it, the program emphasized the fight against political corruption, reforms in the health and education sector to ensure more freedom of choice for people, and the decentralization of power. The party leader, João Cotrim de Figueiredo, had gained a reputation through his parliamentary activity in the previous legislative period as a pro-business liberal representative, so opinion polls predicted a considerable increase in his party.

Similarly, opinion polls predicted good results for the populist right-wing party Chega! (Enough). Its leader's, André Ventura, main focus was attacking the policies of the PS. The party manifesto was heavily anti-socialist. It emphasized nationhood, anti-immigration, a review of the relationship with the EU, and even withdrawal from the Pact of Migration of the United Nations. Ventura used very xenophobic and aggressive language, which seemed to mobilize some voters.

On 28 January, two days before the election, a significant opinion poll came out in the major weekly newspaper Expresso. PS and PSD were practically head to head with a slight advantage for the former. According to this last opinion poll, PS would get 35 per cent, PSD 33 per cent, IL 6 per cent, Chega! 6 per cent, BE 5 per cent, PAN 2 per cent, CDS-PP 1 per cent, and Livre 1 per cent (Expresso 28 January 2022k: 1).

On 30 January, the day of the elections, Antonio Costa's PS achieved an absolute majority of seats with 117 seats (later 120 due to the vote of expatriates), despite just achieving 41 per cent of the vote (Table 1). One of the main reasons for this divergence between votes and seats was that the D'Hondt method for seat allocation is biased toward the larger parties, especially in small districts. If the gap between the first and second parties is enormous, then a majority of seats becomes likely even without a majority of votes. Rui Rio's PSD was the big loser of the night because it got only 29.3 per cent of the vote and 76 seats (later 77 due to the expatriate ballot). It seems that the opinion polls were utterly wrong. It was a considerable shock for the PSD. Another major loser was the CDS-PP, which could not achieve representation and declined from 4.3 per cent in 2019 to 1.6 per cent in 2022. Other losers were the left-wing parties BE, which lost more than half of the vote, reaching 4.5 per cent and eight seats, and the Communist Party-Green coalition (PCP-PEV), achieving only 4.4 per cent and six seats (−6). On election night, both small left-wing parties blamed their bad performance on the polarization strategy of the PS, which called for voters to act strategically in order to prevent the right from coming to power.

Table 1. Elections to the Parliament (Assembleia da República) in Portugal in 2022

Moreover, PAN also had to carry losses because its vote shrank by half to 1.5 per cent and one seat (−3). Livre was able to keep its representative, Rui Tavares.

The big winners were the two right-wing parties that emerged in 2019. Surprisingly, IL got four times more votes, reaching 5 per cent and eight seats, and Chega! became the third largest party in the Parliament, before the small left-wing parties, by achieving 7.2 per cent and 12 seats. The rise of these two right-wing parties is the main reason for the bad result of the PSD, which had to deal with the increasing fragmentation of the vote on the right.

Unfortunately, as in previous elections, the largest party was that of abstentionists. About 48 per cent of the electorate did not vote in the election, a slight improvement of 3 per cent in relation to 2019. Due to considerable logistic problems of electoral management in the two electoral constituencies abroad, the election of four seats in these two districts (Europe and outside Europe) had to be repeated. The results were announced on 23 March 2022. In the end, PS won three seats and PSD one from those constituencies (see Table 1).

A post-electoral survey conducted by the main weekly newspaper Expresso showed that PS won votes from BE and the Communists, while PSD supporters did not go to Chega! but to IL. Also, BE votes went to IL. CDS-PP lost votes to PSD, nil and blank votes. The PSD voters are more likely to be well-educated (16 per cent with a BA/Licenciatura), women, and older people. Voters for PS are older and less educated (Expresso 2022a, 2022b).

Cabinet report

The new Socialist government under Prime Minister Antonio Costa

There was a slight delay in building the new majority government of Prime Minister Antonio Costa. The main reason was major problems in the electoral management of expatriates’ votes in Europe and other parts of the world. Therefore, the Constitutional Court ruled that the elections in these electoral constituencies had to be repeated.

After the final result became known in the second half of March, Prime Minister Antonio Costa was keen to put the new government in place as soon as possible. Longevity in power creates a great problem for any Prime Minister who runs out of suitable personnel. Therefore, he had to expand his pool to the larger society to get excellent people with technical expertise and political experience into the government. The new Costa III government consists of 18 ministers, of which 10 occupy minister positions for the first time (Table 2). Out of the 18, seven are independents with close links to the PS. All the other appointments belonged to the party.

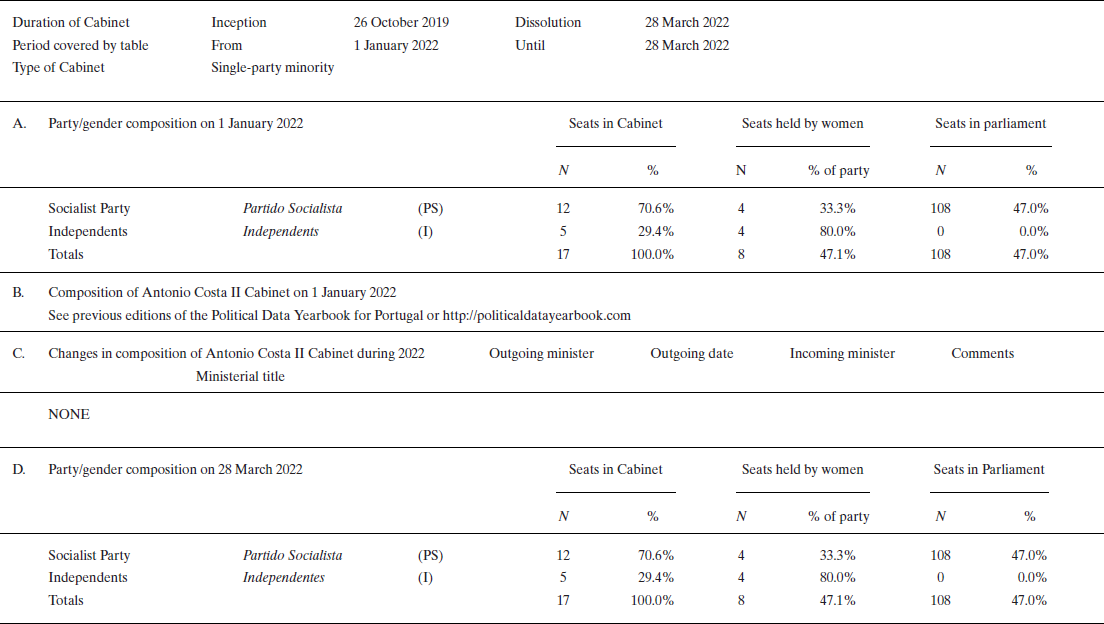

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Antonio Costa II in Portugal in 2022

Source: Governo de Portugal (2023).

Who are the seven independents among the ministers? They are part of the “academocratic” (the strong presence of academics in the Portuguese political elites) pool from which both main political parties tend to recruit their ministers. In the case of the PS, there is a solid inclination to recruit ministers from the prestigious School of Business and Social Sciences ISCTE, created after 1974. The best example is the new Minister for Defence Helena Carreira, a professor of military sociology. Another independent is Catarina Sarmento e Castro, who became the new Minister for Justice. She is a very well-qualified minister because she has been a judge in the Constitutional Court between 2010 and 2019 and a member of the Consultative Council of the General Prosecutor's Office. In the previous Costa II government, she was secretary of state for human resources and veterans. Quite an academic star is Elvira Fortunato, who became the new Minister for Science, Technology, and Higher Education. She is a full professor of materials engineering at NOVA University in Lisbon. Among the male independents, one has to mention Antonio Costa Silva, who has been a successful entrepreneur and prepared the Portuguese strategic plan for recovery and resilience funded by the Next Generation funding of the European Union. Costa was quite thankful for the work of Costa Silva, who appointed him Minister for Economy and Sea. The political scientist Pedro Adão e Silva is a television commentator who takes over culture. More continuity could be found in the Ministry of Education. Secretary of State of Education João Costa replaced, after six years, the former Education Minister Tiago Brandão Rodrigues. João Costa is a full professor of linguistics at the NOVA University and was a long-standing member of the negotiation team dealing with grievances among professors.

The other four new ministers are part of the PS organization. The most prominent is Fernando Medina, the former mayor of Lisbon, who became the “iron chancellor” of Portuguese finances. Medina intends to keep the budget accounts tight (Table 3).

The most essential element of Costa's team is Mariana Vieira da Silva, daughter of éminence grise of the party José Vieira da Silva. She is the confidante of the Prime Minister and took over coordination work related to the European funds from the Resilience and Recovery Plan (PRR) and the structural and investment funds for the Portugal 2030 strategy. It is a huge task, and it remains to be seen if she is up to the job. From the outside, the first months of the government were perceived as not being very well coordinated. This impression was aggravated by the external crisis related to the Russian war against Ukraine and the subsequent rise of inflation and energy prices (Expresso 2022h, 2022i).

One major problem was the deterioration of services in the national health system, which was substantially in debt and underfunded. Therefore, after the summer holidays, Health Minister Marta Temido had to resign. She presented that she did not have the necessary conditions to stay in the job. She was replaced by Manuel Pizarro, who also comes from the medical profession but since 2019 has been a member of the European Parliament for the PS.

Parliament report

The composition of the Portuguese Parliament in 2022 is reported in Table 4.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the Parliament (Assembleia da República) in Portugal in 2022

The cordon sanitaire around right-wing populist party Chega! (Enough)

Throughout March, the third-largest party, the populist right-wing Chega!, tried to get a candidate elected as vice-president of the Parliament. To become vice-president, the candidate has to achieve an absolute majority in the chamber. However, after four attempts with four different candidates, the Chega! failed to get a vice president elected. The Portuguese political parties established a cordon sanitaire around Chega!, not unlike the ones in place in Germany or Belgium around the radical right. Also IL, as the fourth largest party, had the right to appoint a vice-president. However, its main leader, João Cotrim de Figueiredo, failed to be elected, achieving only 108 votes (a minimum number of 116 was needed). Cotrim de Figueiredo expressed his disappointment about the result and declined to try a second time (Visão 2022a).

Negotiations for a very belated budget 2022 and 2023

The absolute majority of the PS contributed to entirely one-sided negotiations with the opposition. The budget bill draft for 2022 did not differ substantially from the one rejected at the end of October 2021. Nevertheless, 1400 amendments were submitted for consideration by the opposition parties (O Observador 2022). However, just about 50 of those were approved, mainly those proposed by the PAN and Livre, the parties that were more supportive of the government. All these changes had no financial impact on the budget. On 27 May 2022, the final vote took place, in which the PS got the bill approved with their majority of 120 MPs. The representatives of PAN and Livre abstained, while the other parties, the PSD, Chega!, IL, the PCP-PEV, and the BE, rejected the budget.

The legislative process of the budget bill for 2023, in October and November, led to a similar pattern of behavior by the Socialist government. Over 1800 amendments were submitted to Parliament. However, only 71 were adopted, all of them without any additional financial impact. On 25 November, the budget was approved by the 120 MPs of the PS. Livre and the PAN abstained from the vote, while the other parties, the PSD, Chega!, IL, the PCP-PEV, and the BE, also rejected this budget bill (SICNoticias 2022).

Finance Minister Medina's ambition was to take over from the PSD as the owner of the economic competence issue by being quite uncompromising on new commitments in the budget. The general plan was to reduce the high debt level of 127 per cent of the GDP to below 100 per cent by 2025. He wanted Portugal to no longer be part of the most indebted countries of the European Union.

Political party report

The 2023 legislative elections led to leadership changes in many political parties (Table 5).

Table 5. Changes in political parties in Portugal in 2022

Democratic-Social Centre-People's Party (CDS-PP)

The failure of the CDS-PP to gain representation in the Assembly of the Republic led to the resignation of its leader, Francisco Rodrigues dos Santos, on election night. In the 29th party conference, which took place on 2–3 April, Nuno Melo was elected as the new president. There were 1145 delegates at the party conference. Eight hundred and fifty-eight (74.9 per cent) voted for the list of Nuno Melo, while 287 cast blank votes (CNN Portugal 2022). Melo will be tasked with rebuilding a bankrupt party that lost most of its public funding subsidies. One of the priorities will be to reduce expenditure. Melo announced that the payment of membership fees will be compulsory from now on. The rest of the year, he worked toward modernizing the party organization.

Psd

PSD leader Rui Rio announced his resignation on election night. However, it took quite a while until a new leader replaced him. His former rival, Luis Montenegro, became the main candidate to succeed Rio in the party's presidency. However, the results of the primaries were only announced on 28 May 2022. Until then, just one other new candidate emerged, Jorge Moreira da Silva, who had been minister of environment in the Pedro Passos Coelho government (2011–2014) and had also worked for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in Paris since 2016. Moreira da Silva started his campaign on 14 April, but it was probably too late because the party organization was already completely controlled by supporters of Montenegro. Montenegristas dominated all regional districts. In the primaries, there were 44,628 registered voters, of which just 59.5 per cent cast their vote. The vast majority of voters supported Luis Montenegro, who got 19,246 votes (72.5 per cent), while Jorge Moreira da Silva only got 7304 votes (27.5 per cent) (Diário de Noticias 2022).

The new PSD leader took his time to start challenging the new Costa government. However, in the second half of the year, he increased his criticism of the government.

Il

On 23 October 2022, it was quite a surprise when trendy leader, João Cotrim de Figueiredo of IL, declared that he would resign due to the need to renew and broaden the party leadership. Soon after, two candidates emerged to succeed him: Rui Rocha e Carla Castro. Cotrim de Figueiredo supported the former. The party convention was initially scheduled for December but it was then postponed to January 2023.

Communist Party (PCP)

After 18 years as leader of the PCP, Jerónimo de Sousa (76 years old) decided to step down for health reasons. He proposed a much younger Paulo Raimundo, who had been a member of the executive bodies of the PCP since 2020. On 12 November 2022, the Central Secretariat unanimously elected the new leader. Raimundo (46 years old) was a member of the Communist Youth in 1991 and then became a party member in 1994. From then on, he rose very fast in the ranks of the Communist party (Visão 2022b). Although Raimundo was very well known inside the party apparatus, he was unknown outside the party.

Issues in national politics

The winding down of pandemic crisis

Although the pandemic crisis still affected political life in January and February, the vast vaccination program in Portugal soon calmed down the situation. By the summer, industrial production and tourism resumed considerably, contributing to a considerable improvement of the economy. In the first quarter, compared to the previous year, the growth rate was 11.9 per cent. In the second quarter, it was 7.4 per cent but then slowed down to 4.8 per cent in the third quarter and 3.2 per cent in the fourth quarter (Eurostat 2023).

The Russian war against Ukraine

One crisis ended, but the Russian war against Ukraine created a new one. Geographically, Portugal is far from the theater of war, but in reality, the country has a strong connection to Ukraine. Since the 1990s, many Ukrainians immigrated to Spain and Portugal and integrated into these societies. Before the war, 27,200 Ukrainians were living and working in Portugal. The war led to an increase to 45,500 people. About 18,400 Ukrainians came into the country under the EU program of temporary protection.

In Portugal, Ukrainians had to deal with some Russians trying to control the refugee civil society networks. One notable case that became known in the country related to the city council of Setúbal. The so-called “Setúbalgate” involved Russian Igor Khashin and his wife. The Council of Setúbal is a stronghold of the Communist Party. According to several reports in the media, the Council allowed Khashin to use a computer of the local authority, although Khashin was not part of the administration. In the confusion of incoming refugees, Khashin would register refugees in the Council's computer and ask the predominantly women refugees questions about the whereabouts of their husbands, sons, and male family members. He spoke Russian to them, which is common among eastern Ukraine Ukrainians. However, the Ukrainian embassy denounced Khashin and contacted the Portuguese government and Parliament to ban him from the refugee civil networks list. It seems that Khashin's organization, LIMAR, was well connected to public authorities and even sporadically with the Socialist government. He was removed from the list of NGOs supporting incoming Ukrainians. Igor Kashin and his wife denied having passed on information to the Russian authorities. They were also not charged by police (Expresso 2022c, 2022d).

Social concertation and the fight against inflation

The Russian war against Ukraine also had implications for the economy. The rise of inflation and the price of energy also impacted Portugal. Before the summer, the government was pressured to support the population against the cost-of-living crisis. In September, the government announced the distribution of €125 to help with inflation. The program had a limited effect because it did not differentiate between rich and poor.

However, on 9 October 2022, the government successfully got social partners, trade unions, and employers’ organizations to support a medium-term agreement to improve incomes, wages, and competitiveness. The last-minute deal was then integrated into the budget bill of 2023. The government committed itself to raising the minimum wage to €900 by 2026 and to reduce the tax burden of companies so that they could pay higher wages. Moreover, it included several measures to facilitate the transition of young people into the labor market (Expresso 2022f).

Constitutional Court ruling on statutes of Chega! as non-democratic

In November 2022, the Constitutional Court ruled that the statutes of the populist right-wing party Chega! give too much power to leader André Ventura. They were also too prescriptive on what members of the party were and were not allowed to do. This was the first time the Constitutional Court issued such a ruling affecting the internal affairs of a party (Expresso 2022j).

Negotiating and implementing the European funds

The Multiannual Financial Framework 2021–2027 awarded Portugal considerable funding. Apart from a regular package of structural and investment funds (€23 billion in 2022), the country was entitled to funds from the temporary Next Generation Fund/Recovery and Resilience Program (PRR) (€18.9 billion in 2022). Moreover, a large part of the previous package, Portugal 2020, was still unspent and partly being reprogrammed (for more details, see Magone Reference Magone2021: 328, Reference Magone2022: 380). However, the first signs emerged of implementation problems due to insufficient materials and personnel. In addition to this, most of the funding was to be invested in public administration projects that replaced national public investment. In particular, two-thirds of the funds were allocated to the public sector, with just about one-third going to the private sector. This prompted an intensive discussion between political parties, interest groups, and businesses about the allocation of the funds (AEP 2022; Expresso 2022e). By the end of the year, a new structural and investment program, Portugal 2030, was still being negotiated with the European Commission. The Portuguese government also asked for more time to implement the Next Generation Funding (Expresso 2022g, 2022h).

Acknowledgments

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

[Correction added on 13 November 2023, after first online publication: Projekt DEAL statement has been added in this version.]