As a matter of course, all democracies depend upon the willingness of capable candidates to step forward and serve (Dal Bó et al., Reference Dal Bó, Finan, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017). And when levels of elite polarization become especially acute, as they plainly have in the United States (McCarty, Reference McCarty2019), the benefits of moderate candidates come into sharp relief (Thomsen, Reference Thomsen2017). What might convince such individuals to run in higher numbers? Would higher-quality and more moderate candidates be willing to run for elected office if, upon winning, they could reasonably expect to accomplish something of significance?

The formal theoretical literature on selection into politics offers little guidance on these questions. In Dal Bó and Finan’s (Reference Dal Bó and Finan2018) model, for example, increasing the rewards of officeholding could either raise or lower the share of “high-quality” candidates—i.e., those who have characteristics that voters value—depending on how the opportunity costs of running covary with candidate quality. Similarly, increasing an officeholder’s policymaking authority could make the office especially attractive to ideological moderates or to ideological extremists, depending on what we assume about whether officeholders care more about policy changes close to or far from their ideal points. Ultimately, it is an empirical matter whether different kinds of candidates prioritize various aspects of holding a public office relative to other opportunities they may pursue.

For all its strengths, alas, the existing empirical literature on political selection says very little about what might generate a higher quality or more moderate candidate pool (for reviews, see Dal Bó and Finan, Reference Dal Bó and Finan2018; Gulzar, Reference Gulzar2021). To be sure, numerous studies document differences in the willingness of various kinds of people to run for elected office. The preponderance of this literature, however, focuses on candidates’ ascriptive, personality, and background characteristics. By comparison, it has far less to say about their political dispositions or quality—features, both, that bear directly on their performance in office.

When evaluating what might convince people to run for office, meanwhile, the empirical literature typically focuses on factors that only tangentially relate to a principal motivating reason for doing so—namely, the opportunity to serve and thereby make a difference. The literature documents the effects of fundraising obligations, a candidate’s probability of winning, party outreach efforts, and the financial rewards of holding office on the size and demographic composition of a candidate pool (see citations below). As Dal Bó and Finan (Reference Dal Bó and Finan2018, 543) point out, however, empirical evidence about the relevance of “nonpecuniary benefits” of actually holding elected office “is practically nonexistent.” And no one, to our knowledge, has studied how opportunities to advance a policy agenda, which vary widely and crucially depend upon the design of political institutions, affect the willingness of different groups of citizens to run for office.

To investigate the matter, we proposed a series of hypothetical political office profiles to a nationally representative sample of politically attuned and registered voters in the United States. In addition to items already recognized by the candidate-entry literature, we randomly varied aspects of a city council seat that directly affect how much the officeholder could advance a policy agenda: the amount of authority vested in the position, the voting requirements needed to enact a law, and the quantity of staffing that supports it. We then asked respondents how interested they were in running for each hypothetical office. We also created an index of moderation (based on ten questions eliciting partisanship, self-assessed ideology, affective polarization, policy preferences, and openness to compromise) and an index of quality (based on sixteen questions assessing managerial experience, cognitive ability, earnings, education, and political knowledge). Collectively, these data allow us to evaluate the effects of electoral and governance factors on both the overall size and composition of the candidate pool.

We find that lower campaign fundraising expectations, less media exposure, higher salaries, improved chances of winning, and greater authority all stimulate interest in running for office, thus likely increasing the size of the candidate pool. To alter the composition of the pool, however, one must move interest differentially, and here governance factors stand out as particularly important. Singularly, the opportunity to wield greater authority increases moderates’ average interest in running for office but has no similar effect for extremists. Meanwhile, more qualified respondents express relatively higher interest in running for office when greater authority is invested in an office, the threshold needed to pass legislation is lower, and staff support is higher. While these trends hold across the full distribution of interest, the disparities in estimated effects are particularly large at moderate-to-high levels of interest in running.

Consistent with other research (e.g., Hall, Reference Hall2019), we also find that more qualified individuals are particularly likely to run for office when they stand a good chance of winning the election, fundraising obligations are low, and salaries are high. We do not find any evidence, however, that electoral considerations differentially affect the willingness of ideologically moderate individuals to run for office.

These findings, we suggest, constructively bridge ongoing debates about institutional and electoral reform. Changes to the design of political institutions do more than just mitigate gridlock and dysfunction. They also alter the willingness of more moderate and more qualified individuals to run for office. So doing, the effects of institutional reforms radiate outward beyond the domains of governance and into our mass politics, underscoring the relevance of effective government for democratic flourishing.

1. Background

A substantial body of empirical work documents variable patterns of public office-seeking among different populations (Gulzar, Reference Gulzar2021). Much of this scholarship focuses on ascriptive characteristics such as sex and gender (Lawless and Fox, Reference Lawless and Fox2005, Reference Lawless and Fox2010; Lawless, Reference Lawless2015), race and ethnicity (Juenke and Shah, Reference Juenke and Shah2016; Shah et al., Reference Shah, Scott and Juenke2019), and age (Stockemer et al., Reference Stockemer, Thompson and Sundstrom2023). Related work focuses on the tendency of citizens with different latent characteristics—as defined by their personality traits (Dynes et al., Reference Dynes, Hans and Matthew2019) or ambition (Fowler and McClure, Reference Fowler and McClure1990; Lawless, Reference Lawless2012)—to seek public office. And other work investigates the relevance of socioeconomic indicators, including wealth (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Feigenbaum, Hall and Yoder2019), education (Carreri and Payson, Reference Carreri and Payson2021), and working-class background (Carnes, Reference Carnes2013; Carnes and Lupu, Reference Carnes and Lupu2016). Meanwhile, a handful of studies focus squarely on factors that directly affect candidates’ performance in office, including their ideology (Thomsen, Reference Thomsen2017; Hall, Reference Hall2019) and their qualifications, ability, or competence (Dal Bó et al., Reference Dal Bó, Finan, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017).

When looking for ways to alter the size or composition of a candidate pool, scholars recommend reforms that fall nearly exclusively in one of three domains.Footnote 1 The first involves reducing the considerable burdens, inconveniences, stresses, and financial costs of running a campaign. The unending obligations to raise money, the red-hot glare of the media, the invasions of privacy, and personal insults that pervade campaigns dissuade many Americans from running for public office (Lawless, Reference Lawless2012). Some of these costs may be intractable, as they are built into competitive elections. But others might be reduced by, say, providing public financing for campaigns. As Hall (Reference Hall2019, 103) argues, “Begging people to become candidates for office would be so much easier if we attacked some of the factors, most notably campaign finance reform, that currently deter so many citizens from entering politics.”

To enhance citizen interest in elected office, the literature also underscores the importance of parties, interest groups, and other political networks (Norris, Reference Norris1997; Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Karol, Noel and Zaller2009; Fox and Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2010; Broockman, Reference Broockman2014; Karpowitz Christopher and Preece, Reference Karpowitz Christopher and Preece2017). Citizens rarely decide to pursue elected office all on their own. Rather, they are recruited by others who, having planted the idea, then offer various forms of support in their campaigns. Acting on these insights, outreach organizations across the political spectrum, including Emily’s List and Run for Something on the Left and the Leadership Institute and Young America’s Foundation on the Right, devote themselves entirely to pipeline problems that inhibit various forms of political representation. By sharpening their messages, strengthening their networks, and building their relationships with prospective candidates, it is thought that outreach organizations might meaningfully enhance the size, diversity, and qualifications of candidate pools (Kreitzer and Osborn, Reference Kreitzer and Osborn2019).

Lastly, several scholars suggest that changes to electoral and voting rules may affect candidate-entry decisions (Kanthak and Woon, Reference Kanthak and Woon2015; Beath et al., Reference Beath, Christia, Egorov and Enikolopov2016; Arora, Reference Arora2020). Whether an election is held on- or off-cycle or candidates are selected via one voting rule or another, it is argued, systematically affects the composition of both an electorate and the candidates from which it must choose (Anzia, Reference Anzia2014; Fiva et al., Reference Fiva, Halse and Smith2020). If you want to alter the number or types of people seeking public office, then one need only recalibrate the terms under which they compete against one another.

Across this vast literature, however, relatively little attention is paid to the electoral contest’s actual prize: namely, the opportunity to serve in an office with variable powers, resources, and opportunities to change public policy. To be sure, studies have assessed the relevance of various pecuniary and professional considerations, such as salaries (Ferraz and Finan, Reference Ferraz and Finan2011; Gagliarducci and Nannicini, Reference Gagliarducci and Nannicini2013; Carnes and Hansen, Reference Carnes and Hansen2016), future earnings (Eggers and Hainmueller, Reference Eggers and Hainmueller2009; Querubin and Snyder, Reference Querubin, Snyder, Aragones, Bevia, Llavador and Schofield2009), and opportunities for career advancement (Schlesinger, Reference Schlesinger1966; Cherie et al., Reference Cherie, Sarah Fulton and Stone2007). Some studies find that women are more interested in running for office when they can see the policy consequences of their underrepresentation (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2023) or when they believe they can fulfill communal goals (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016). And since at least Black (Reference Black1972), scholars have noted the relevance of “structural incentives” (also commonly referred to as “political opportunity structures”) for candidate-entry decisions (see also Rohde, Reference Rohde1979; Stone and Maisel, Reference Stone and Maisel2003). Even when recognized, though, the political benefits of holding office are cast in general terms. Routinely, the candidate-entry literature either disregards or glosses over details about the actual job that elected officials are expected to perform, and the authority, opportunities, and support systems needed to perform it well.Footnote 2

The literature thus conceals the actual attraction of public service, as perceived by at least some individuals. Although they may dissuade some citizens from running, the burdens and inconveniences of elections are not the motivating reasons citizens seek elected office. Rather, many citizens enter politics in order to harness the powers of government in ways that alter public policy and change people’s lives. It stands to reason that elected officials’ ability to accomplish these things, which is not assured and crucially depends upon the institutional features of the position they hold, may inform their calculus about whether to run.

Though untested, such expectations are not without foundation. Research in organizational psychology affirms that job satisfaction and retention in other forms of work are higher when workers have more autonomy and perceive a greater impact of their work on others’ lives (see Humphrey et al. (Reference Humphrey, Nahrgang and Morgeson2007) for a review). It seems reasonable to expect potential political candidates to also consider these features when contemplating running. Indeed, many scholars of American politics lament the rise of polarization, gridlock, and political dysfunction not just for degrading the operations of government but also, and by extension, for depressing public interest in public service (Hall, Reference Hall2019).

By enhancing opportunities to govern, we may do more than just increase the size of a candidate pool. To the extent that these opportunities differentially appeal to various types of potential candidates, we also may alter the pool’s composition. In contemplating such heterogeneous effects, our main analyses investigate whether these opportunities are especially likely to convince higher-quality and more moderate individuals to run for public office.Footnote 3

It is possible, of course, that both populations are more likely to be nearly indifferent between running and not running, in which case marginal increases in the attractiveness of an office—whether by augmenting its authority, increasing its staff, or any other mode of improvement—would yield disproportionately more of these individuals into the candidate pool. But why might either group of individuals care more about these opportunities to govern? Let’s start with higher-quality individuals. Such individuals, it seems fair to postulate, may be better able to translate the authority needed to govern into actual governing accomplishments. And if authority and quality operate as complements, then higher-quality individuals should place more value on authority when assessing a potential office. Similarly, and relatedly, higher-quality individuals may foresee greater career advancement over the course of their professional lives. To the extent that establishing a record of accomplishment in one professional setting opens up subsequent opportunities for employment in another, then these individuals may pay particular attention to their ability to exercise meaningful and discernible influence in any job, very much including an elected office.

And why might more moderate individuals care more about opportunities to govern? One possibility is that most governing accomplishments are incremental movements from one basically moderate position to another, and ideological moderates care more about these shifts than ideological extremists do.Footnote 4 Another possibility is that accomplishments require both authority and compromise, and moderates are more willing to compromise than extremists are, so they value authority more. Yet another possibility (especially relevant to legislatures and other collective decision-making bodies like the ones in our vignettes below) is that ideological moderates expect to be the decisive vote on more issues, so their individual influence is more sensitive to the authority of the office than would be the case for ideological extremists.

While these heterogeneous effects are plausible, they are not theoretically guaranteed. Indeed, they could operate in the opposite direction. It is possible, for instance, that extremists and moderates expect to be equally influential and therefore care equally about authority, or that extremists care more about incremental policy changes than moderates do and therefore care more about authority. Given that previous empirical work is mostly silent on whether the prospect of wielding authority in office attracts candidates in general, or does so differentially by quality and moderation, we see a need for new evidence on the question.

2. Data and measures

To help answer these questions, we measured interest in running for hypothetical offices using a ratings-based conjoint design administered to 3,000 YouGov subjects, recruited to participate in an online survey in January of 2024.Footnote 5 To ensure our sample was oriented toward respondents who might plausibly consider running for elected office, we restricted participation to validated registered voters who stated that they followed government and public affairs at least “some of the time.”Footnote 6 In the experiment, respondents were presented with a series of hypothetical scenarios in which they might run for a full-time city council seat. For each scenario, respondents were asked to rate their interest in running for the described position on a scale from 1 to 10. In most of our analyses, we rescale this measure so that it ranges from 0 to 1. On this scale, the average response value was 0.314, the median was 0.222, and the standard deviation was 0.329.Footnote 7

Our decision to study a broad, representative sample of politically attuned, registered voters was intentional. Previous research has focused on politically more circumscribed populations. For example, Butler and Preece (Reference Butler and Preece2016) study local officeholders; Bernhard et al. (Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021) study participants in a candidate training program; and Lawless and Fox (Reference Lawless and Fox2005, Reference Lawless and Fox2010) study members of the professions that most often produce politicians. Our sample includes people even further removed from existing candidate pipelines, which allows us to study factors that might convince a broader range of citizens to run for office.Footnote 8

In our conjoint design, we experimentally vary different features of political office and are able to capture causal features of these manipulations in average marginal effects, discussed below. Beyond average effects, we also want to assess how these different features of office differentially appeal to more moderate and more qualified individuals. We leverage the variation in respondent characteristics within our sample to describe patterns of treatment effect heterogeneity across groups of respondents with different qualities. While treatment effects within groups retain a causal interpretation, differences in effects across groups should be interpreted descriptively, rather than causally.

We conceive of two senses in which citizens and officeholders can be politically moderate. First, they can have moderate political preferences, meaning that they prefer policies closer to the middle of the political spectrum. We measure this sense of moderation using respondents’ self-described political ideology (somewhat versus very liberal or conservative), self-described partisan identification (weak versus strong Democrat or Republican), and three continuous questions about police budgets, the federal minimum wage, and abortion policy. We also recognize that respondents can have a moderate political temperament, meaning that they tolerate those who disagree with them and are willing to seek compromise. To measure this second type of moderation, we use a measure of affective polarization (the absolute difference in the thermometer score the respondent assigns to Democrats and Republicans in their area) and four questions gauging support for compromise versus sticking with one’s principles. We recode each survey item so that the most moderate response is 1 and the least moderate response is 0. For each respondent, we then compute an average score across all ten variables. Our final measure of moderation has a mean value of 0.556, a median of 0.553, and a standard deviation of 0.170.

In measuring the quality of potential candidates, we seek to gauge respondents’ likely ability to serve effectively in public office. Since Jacobson (Reference Jacobson1989), scholars have routinely used past political experience as a proxy for a candidate’s quality. Whatever information such a measure contains, however, it is plainly inappropriate for a study of candidate entry that is informed, at least in part, by a concern that we are currently failing to attract the right kind of people to run.

More recently, scholars have introduced measures of quality that are both more suitable for studying candidate entry and more informative about different dimensions of quality. Drawing on their insights, our measure of quality is an index of questions that tap into distinct facets of quality as well as assessments of political knowledge and political interest. To assess respondents’ success in the private sector and education, we collect information on their full-time employment status, personal earnings (as in Besley et al., Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017), and college completion (as in Besley et al., Reference Besley, Montalvo and Reyanl-Querol2011). Drawing on Carreri (Reference Carreri2021) and Carreri and Payson (Reference Carreri and Payson2021), we include indicators for whether respondents have experience conducting various managerial tasks (running meetings, setting a budget, leading a team, writing an organizational mission statement, and developing a strategy for achieving organizational goals). Drawing on Dal Bó et al. (Reference Dal Bó, Finan, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017), we include three measures of cognitive reflection, which test respondents’ intelligence or ability to reason. Finally, we include the respondents’ self-assessed attention to politics and understanding of politics, as well as indicators for whether they can correctly identify four prominent political figures from photos. Although other studies more precisely capture specific components of quality (e.g., earning power in Besley et al., Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017, intellectual ability in Dal Bó et al., Reference Dal Bó, Finan, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017, and managerial skill in Carreri, Reference Carreri2021), our measure taps into each of these aspects, adds engagement with politics, and can be measured in an online survey that includes non-politicians. The final measure of quality has a mean value of 0.499, a median of 0.501, and a standard deviation of 0.194.Footnote 9

Our pre-registered measures of moderation and quality are original and, like all previous measures of these concepts, imperfect and somewhat arbitrary. Readers may disagree about which components belong in each measure or how the indices should be interpreted. For example, some readers may believe that a college education indicates privilege more than it indicates qualification for elected office. Besley et al. (Reference Besley, Montalvo and Reyanl-Querol2011) find that more educated national leaders tend to produce higher economic growth, but Carnes and Lupu (Reference Carnes and Lupu2016) find that college-educated leaders from the United States and Brazil do not perform better. However, the latter null results could be attributable to selection bias; among the selected sample of elected officials, we would expect those without a college degree to be exceptional on other dimensions. Furthermore, voters seem to prefer more educated candidates (Arceneaux and Wielen, Reference Arceneaux and Wielen2023) and perceive them as more qualified (Holliday, Reference Holliday2024). Although more privileged people are surely more likely to complete college, we suspect that smarter, harder-working people are also more likely to complete college, and in principle, a college education should impart valuable skills. Therefore, we believe college completion is a noisy but useful proxy for quality within our survey sample.

Anticipating potential concerns about our measures, we subsequently show that our main findings hold when we construct the aggregate indices in different ways and focus on different subindices. For example, our subsequent results on quality are similar if we use our aggregate measure or if we only use the more objective measures of quality that focus on whether respondents correctly answered questions from the cognitive reflection test. Figure 1 shows how our measure of interest in running for office corresponds with our measures of moderation and quality. Consistent with Hall (Reference Hall2019), we find that ideologically moderate individuals are, on average, notably less interested in running for office than ideologically extreme individuals. We also find that more qualified individuals are somewhat more interested in running for office, but the correlation with quality is not nearly as strong as the correlation with ideology. Supplementary Appendix Figure A2 further explores the relationship between interest in running for office and the joint distribution of moderation and quality. We find that moderation and quality are only weakly related, but together, they correspond strongly with interest in running for office. Respondents who are more extreme and more qualified are particularly likely to be interested in running for office, while those who are more moderate and less qualified express lower levels of interest.

Figure 1. Mean interest conditional on quality and moderation.

3. Experimental design and estimation strategy

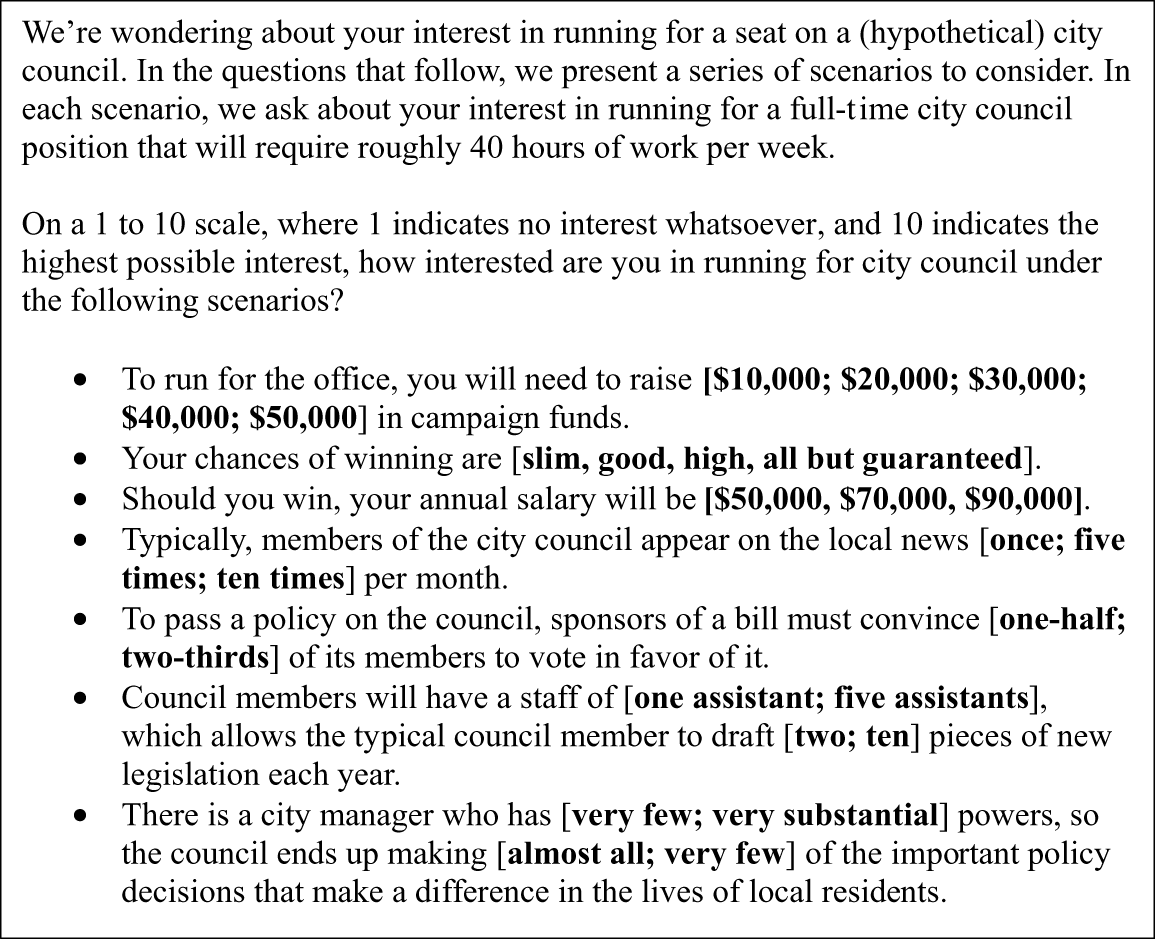

In our conjoint experiment, we randomly varied the features of a hypothetical city council position and measured respondents’ interest in running for such a position. Specifically, we randomly varied the fundraising expectations of the position, their likely chances of winning, the salary, the amount of media coverage, whether there is a majority or supermajority requirement for passing new laws, the amount of formal authority held by the city council, and the number of staff that each councilor can hire. The specific vignette text and feature components are presented in Figure 2. Each of our 3,000 respondents rated eight conjoint profiles, resulting in 24,000 observations. We randomly varied the order of features at the individual level, then held the order fixed for each respondent across scenarios. The levels associated with each feature were randomized independently, and each level was presented with equal probability.

Figure 2. Conjoint text and feature levels.

We estimate average marginal effects of the conjoint features using the following estimating equation:

\begin{equation}{Y_{ij}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{\ell = 1}^L {\beta _\ell }{T_{\ell ij}} + {\gamma _i} + {\delta _j} + {\varepsilon _{ij}}\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{Y_{ij}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{\ell = 1}^L {\beta _\ell }{T_{\ell ij}} + {\gamma _i} + {\delta _j} + {\varepsilon _{ij}}\end{equation} Conjoint interest ratings Y are indexed over individuals i and scenario order j and are rescaled to range from 0 to 1. Fixed effects for individuals and scenario order are denoted by ![]() ${\gamma _i}$ and

${\gamma _i}$ and ![]() ${\delta _j}$, respectively. The variable

${\delta _j}$, respectively. The variable ![]() ${T_{\ell ij}}$ represents a linearized measure of conjoint feature

${T_{\ell ij}}$ represents a linearized measure of conjoint feature ![]() $\ell $ with increasing levels equally spaced between 0 and 1. For example, a fundraising feature variable would take on a value of 0 for a variable level of $10,000, 0.25 for $20,000, 0.5 for $30,000, 0.75 for $40,000, and 1 for $50,000. The coefficients of interest,

$\ell $ with increasing levels equally spaced between 0 and 1. For example, a fundraising feature variable would take on a value of 0 for a variable level of $10,000, 0.25 for $20,000, 0.5 for $30,000, 0.75 for $40,000, and 1 for $50,000. The coefficients of interest, ![]() ${\beta _\ell }$, describe the average marginal effects of each feature. Standard errors are clustered at the individual level.

${\beta _\ell }$, describe the average marginal effects of each feature. Standard errors are clustered at the individual level.

Fixed effects are not necessary for unbiased estimates of our treatment effects, but analysis from our pilot experiment suggests that their inclusion provides greater statistical precision in our setting. Clustering is only necessary to account for random sampling (Abadie et al., Reference Abadie, Athey, Imbens and Wooldridge2023). Our effect estimands marginalize over a uniform distribution of profiles; this facilitates the straightforward linear interpretation of our coefficients as described. While different combinations of these features might occur at different frequencies in city council offices in practice, which could imply different reference distributions and possibly alternative estimands of interest (de la Cuesta et al., Reference la Cuesta, Brandon and Imai2022), we consider all hypothetical profile combinations to be plausible in theory.

In addition to the average marginal effects, we are also interested in the different effects of every conjoint feature on different subpopulations, as defined by their moderation and quality.Footnote 10 To recover possible heterogenous treatment effects, therefore, we modify Equation (1) to additionally include the interaction of treatment with our scales of quality or moderation separately. Scales are denoted by X and indexed by p:

\begin{equation}{Y_{ij}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{\ell = 1}^L \left( {{\beta _\ell }{T_{\ell ij}} + \,{\beta _{\ell \times p}}\,{T_{\ell ij}}{X_{pi}}} \right) + {\gamma _i} + {\delta _j} + {\varepsilon _{ij}}\end{equation}

\begin{equation}{Y_{ij}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{\ell = 1}^L \left( {{\beta _\ell }{T_{\ell ij}} + \,{\beta _{\ell \times p}}\,{T_{\ell ij}}{X_{pi}}} \right) + {\gamma _i} + {\delta _j} + {\varepsilon _{ij}}\end{equation} Coefficients of interest from the model are ![]() ${\beta _{\ell \times p}}$ for each feature and for quality and moderation, respectively.

${\beta _{\ell \times p}}$ for each feature and for quality and moderation, respectively.

4. Main findings

Table 1 presents our estimates from Equation (1) of the average marginal effect of each element of the conjoint. The estimated coefficients can be interpreted as the average effect of going from the lowest to the highest value of each variable, each of which has been rescaled to range from 0 to 1. For example, the first coefficient predicts that as the fundraising expectations increase from the lowest to the highest level presented in the experiment, respondents become on average .046 points (4.6 percent of the entire scale) less interested in running for office.

Table 1. Average effects of office features on interest

Respondent-clustered standard errors are in parentheses. **p < .01, *p < .05.

When focusing on factors unrelated to the core functions of elected office, our results generally align with those found in the candidate-entry literature. All else equal, respondents are more interested in running for office when their chances of winning are higher, when the salary of the position is higher, when their fundraising expectations are lower, and when they can expect to receive less media coverage. Of these factors, media coverage has the smallest average marginal effect, possibly because some respondents prefer more media coverage and others prefer less.

Of the three office characteristics that have to do with governing, we find no statistically significant average marginal effect for a supermajority rule (relative to a simple majority rule) or for the size of one’s staff. However, we do find that, on average, respondents are more interested in running for office when elected officials have more formal authority. The substantive magnitude of this effect is approximately four times the average marginal effect of media coverage, comparable to the effect of fundraising expectations, approximately two-thirds the effect of salary, and approximately half the effect of one’s chances of winning.

By reducing electoral costs and increasing either the salary or authority associated with an elected office, we can expect to augment overall levels of interest in running. But what might be done to alter the composition of a candidate pool? As shown in the top panel of Figure 1, moderates generally express lower levels of baseline interest in running for public office than do extremists; and as shown in the bottom panel, interest in running for office increases in measured levels of quality.

Do more moderate and more qualified individuals respond differently to the elements of the vignette? Tables 2 and 3 report heterogeneous effects for the two respective groups, as characterized in Equation (2). The first column of results in Tables 2 and 3 shows the predicted marginal effects for respondents at the lowest levels of moderation or quality, respectively, in our sample. The second column shows the predicted marginal effects for those with the highest level of moderation or quality. And the third column shows the interactive coefficients of interest, indicating the extent to which the marginal effect of each item changes as we go from the lowest to the highest level of moderation or quality.

Table 2. Heterogenous effects by moderation

Respondent clustered standard errors are in parentheses; **p < .01, *p < .05. N = 24,000. The table presents results from the regression described in Equation (2) in which we interact the conjoint items with our moderation scale. The first column shows the predicted marginal effects for respondents at the lowest levels of moderation in our sample. The second column shows the predicted marginal effects for those with the highest level of moderation. And the third column shows the interactive coefficients of interest, indicating the extent to which the marginal effect of each item changes as we go from the lowest to the highest level of moderation.

Table 3. Heterogenous effects by quality

Respondent clustered standard errors are in parentheses; **p < .01, *p < .05. N = 24,000. The table presents results from the regression described in Equation (2) in which we interact the conjoint items with our quality scale. The first column shows the predicted marginal effects for respondents at the lowest levels of quality in our sample. The second column shows the predicted marginal effects for those with the highest level of quality. And the third column shows the interactive coefficients of interest, indicating the extent to which the marginal effect of each item changes as we go from the lowest to the highest level of quality.

Interestingly, most of the interactive coefficients in Table 2 are statistically indistinguishable from zero. Although fundraising, winning, and pay have large average effects, those effects appear to be comparable for extremists and moderates. For example, while other scholars have suggested that higher salaries might increase the share of moderates running for office (e.g., Hall, Reference Hall2019), we find that higher salaries are no more compelling to moderates than to extremists. If anything, our point estimates suggest that extremists might be more responsive, although the interaction is not statistically significant. Somewhat surprisingly, we also find that extremists are more averse to media coverage than moderates, although this difference is also not statistically significant.

The one factor that significantly interacts with ideology is authority. While greater authority, on average, increases interest in running, this effect is particularly strong for ideologically moderate individuals. As we move from the most extreme to the most moderate respondents in our sample, the estimated effect of authority increases from approximately .01 to .06, and this difference is highly statistically significant (p = .006). Among all the elements in the conjoint, increased formal authority for elected officials is the single institutional reform that differentially induces moderates to run for office.

Table 3 shows the comparable results for quality. Here, we find that many of the conjoint factors interact with our measure of a candidate’s quality and qualifications. We find that, on average, more qualified individuals are particularly averse to fundraising expectations, responsive to their chances of winning, interested in a higher salary, and, notably, interested in more formal authority. Furthermore, although we detected no average effect of a supermajority requirement or staff size, the results in Table 3 suggest that this masked important heterogeneity by quality. We estimate that the least qualified respondents are more interested in running if there is a supermajority requirement for passing new laws, while the most qualified respondents are less interested, and the difference is statistically significant (p = .009). Furthermore, although we find no statistically significant evidence that the least qualified respondents are responsive to staff size, we find clear evidence that the most qualified respondents are more interested in running for office if they will have a larger staff, and this difference is also statistically significant (p = .017).

Once again, we see the abiding significance of opportunities to govern. More qualified individuals express higher levels of interest in running for elected office when they can expect to have more formal authority and staff support, and when policies are voted on a straight majoritarian basis. If we want higher-quality candidate pools, we would do well to design political offices that enable them, when elected, to exercise meaningful influence and accomplish something of value.

4.1. Robustness checks

When testing for interactions with moderation, we do not account for interactions with quality, and vice versa. Our moderation and quality scales are modestly positively correlated with one another (r = .056), so some of the apparent interactive effects associated with one variable could be explained by the interactive effects of the other variable. Although this analysis was not pre-registered, readers may be interested to know whether our results change when we simultaneously account for both sets of interactions. The results in Supplementary Appendix Table A2 suggest that none of our results change appreciably when we account for interactions with moderation and quality simultaneously.

All of our findings, thus far, are based on measures of moderation and quality resulting from averaging all of our constituent measures of each construct. Following our pre-registration plan, in Supplementary Appendix Table A3, we separately analyze different subindices of moderation and quality that rely on subsets of the measures used to create our main constructs. Exploratory factor analyses of our pilot data revealed that the cognitive reflection questions may measure a slightly different dimension of quality than the other questions that focus more on self-reported qualifications. And similarly, analyses of our pilot data revealed that our policy questions might pick up a slightly different dimension of moderation than our party- or identity-related questions. Although results can be expected to vary somewhat due to noise and imprecision, our findings are substantively comparable for both measures of quality and both measures of moderation.

In further exploratory analysis that was not pre-registered, we separately analyzed different components of the policy moderation subindex mentioned earlier. Specifically, we distinguished between issue moderation and support for compromise. Results of these analyses are available in Supplementary Appendix Table A15. Respondents who support compromise appear to be particularly responsive to the chances of winning, while those with moderate issue positions are not. Furthermore, our result that moderates are particularly responsive to formal authority is driven more by those who support compromise than by those with moderate issue positions.

4.2. Validity checks

To gauge the integrity of the data collection, we conducted a variety of validity checks. To begin, we considered the burdens placed on each respondent from evaluating eight separate scenarios, each with seven factors. Work by Bansak et al. (Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2018, Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2021) suggests this design selection should not result in meaningful respondent fatigue. Still, for idiosyncratic reasons, respondents in our sample may have paid less attention to the vignettes over time, which would cause the treatment effects to attenuate in later scenarios. To investigate this possibility, we estimated a version of Equation (2) with features interacted with an index of scenario order scaled from 0 to 1. As shown in Supplementary Appendix Table A4, we find no evidence of such attenuation over time.

Following the conjoint experiments, we directly asked respondents about the importance of each of the factors when thinking about running for public office. To assess how the estimated marginal effects from the conjoint experiments correspond with our respondents’ answers to these direct questions, we then estimated a version of Equation (2) with features interacted with the corresponding direct measure. Our findings, which are also presented in Supplementary Appendix Table A4, show that respondents are particularly sensitive to changes in factors of the conjoint that they subsequently recognized as important to them. Additional checks on attentiveness are reported in Supplementary Appendix Table A5.

4.3. Multiple testing

Of the 14 different interactive tests conducted across Tables 2 and 3, we obtained a statistically significant result (p < .05) for seven. Of course, with 14 different tests, some significant estimates could arise by chance even if there are no heterogeneous effects. To assess this possibility and to correct for multiple testing, we conducted simulations in which we randomly permuted all treatment variables according to the same randomization rules used in the original experiment, re-ran all tests, and recorded the lowest p-value and the number of significant interactive coefficients. We repeated this procedure 10,000 times. These simulations suggest that under the null hypothesis of no interactive effects, the chances of obtaining at least one significant result are 51 percent. The chances of at least two significant results are 15 percent. And the chances of at least three, four, or five significant results are 3, 0.4, and 0.05 percent, respectively. In none of our simulations did we obtain more than five significant interactive estimates. Similarly, in none of our simulations was the lowest p-value lower than that from our actual tests. Therefore, we can strongly reject the null hypothesis of no interactive effects, and we can be confident that most, if not all, of our significant estimates are the result of genuine interactive effects rather than an artifact of multiple testing.

We conducted similar tests focusing only on the six interactive tests associated with governing. We obtained significant estimates for four of the six tests. Simulations suggest that under the null, the chances of obtaining at least one, two, three, or four significant results are 26, 3.5, 0.2, and 0.02 percent, respectively. Similarly, we never obtained a p-value as low as the lowest p-value from our actual analysis. So if we consider all interactive tests or focus on those tests related to the nature of governing, we can reject the null hypothesis of no effects.

5. Extensions

Apart from column 4 of Supplementary Appendix Tables A2 and A15, all of the previously discussed analyses were pre-registered. We conducted additional exploratory analyses that were not pre-registered, relevant to both our main findings and the larger candidate-entry literature.

5.1. Varying cutpoints

The dependent variable in our analysis so far is a continuous measure of interest in running for office, so the average effects that we detect could reflect changes in interest among individuals who either have very little interest in running or are already committed to doing so. If so, then our main findings, while still politically relevant, may have less to say about the promise of different reforms for changing the overall size or composition of actual candidate pools.

To investigate this matter further, we re-estimated our main models for alternative characterizations of the dependent variable. We construct an indicator that is 1 if interest in running for office is above a cutpoint x, and 0 otherwise; we then repeat our earlier analysis, regressing this indicator on features of office interacted with respondent quality or moderation. By repeating this analysis for all possible cutpoints x, we can assess how the effect of each feature of office varies across more moderate and more qualified respondents with varying levels of interest in running for office.Footnote 11

Figure 3 shows these estimates by respondent moderation. Consider first the “Authority” panel, which reports the effect of changing the office in question from low authority to high authority on the predicted probability of interest in running being above each cutpoint x. When the cutpoint is 5 (on the original 1–10 scale), this effect is estimated to be about .09 for high-moderation respondents and around .015 for low-moderation respondents. The magnitude of the estimated effects for high-moderation respondents decreases as we increase the cutpoint, and the effect is also small for low cutpoints. For all cutpoints, however, the predicted effect is larger for high-moderation respondents than for low-moderation respondents. To the extent that the individuals moved at any of these cutpoints included respondents who became willing to run for office, this provides evidence that increasing the authority invested in the office should make the candidate pool more moderate. We do not see similarly large gaps for any other feature.

Figure 3. Varying cutpoints, moderation.

Figure 4 shows the same analysis by respondent quality. For office authority, office pay, and the probability of winning, we find sizable differences in the predicted effect between more and less qualified respondents across almost all cutpoints, but especially at cutpoints near the middle of the scale.Footnote 12 While the differences are smaller in magnitude, levels of staff support and the existence of supermajoritarian voting rules also create separation between the expressed levels of interest between more and less qualified individuals across the entire scale. Crucially, we do not find any evidence that our main findings are driven by low-interest respondents.

Figure 4. Varying cutpoints, quality.

5.2. High-quality moderates

All of our previous analyses parse the influence of different conjoint factors for more moderate and more qualified citizens. What happens when we subset the data to identify individuals who are both moderate and qualified? To do so, we code a binary variable indicating whether a respondent is both more qualified than the median respondent and more moderate than the median respondent. This applies to 25.4 percent of our respondents. In Supplementary Appendix Table A6, we test for heterogeneous effects according to this binary variable. We find that respondents who are both qualified and moderate are significantly more responsive to their chances of winning, salary considerations, and, most acutely, the authority vested in an elected office. Supplementary Appendix Figure A3 presents a visual representation of these findings, describing how treatment effects of the factors vary over the joint distribution of quality and moderation.

5.3. Other compositional changes

Whereas our paper focuses on candidates’ ideology and quality, the larger candidate-entry literature examines the representation of a wide array of background characteristics. Related to significant scholarly debates about women’s underrepresentation among political candidates (e.g., Lawless and Fox, Reference Lawless and Fox2005), therefore, Supplementary Appendix Table A7 shows heterogeneous effects by gender. Surprisingly, and in contrast with claims in the literature, most of the interactive estimates are statistically insignificant. Women are not differentially sensitive to fundraising requirements, chances of winning, or media coverage. The only significant result suggests that women, on average, are less responsive to salary, suggesting that paying higher salaries to politicians would increase interest in running more for men than for women, potentially decreasing women’s representation among elected officials. This is consistent with other work suggesting that the relationship between economic circumstances and political ambition differs for men and women (Bernhard et al., Reference Bernhard, Shames and Teele2021).

Other scholars have highlighted the underrepresentation of working-class Americans among political candidates (e.g., Carnes, Reference Carnes2013). We classify subjects as working class if they work in a service industry or in an industry involving manual labor (e.g., agriculture, mining, construction, manufacturing, restaurants, and lodging, maintenance), if they do not have a 4-year college degree, and if their personal earnings are less than $100,000 per year. Interestingly, we find no significant differences between working-class and non-working-class subjects in their responsiveness to our treatments (Supplementary Appendix Table A8).

We also investigated other sources of heterogeneity. On race, we find that white citizens are more responsive to authority and their chances of winning than are people of color (Supplementary Appendix Table A9). On age, we find that younger respondents are more sensitive to salary considerations and less sensitive to authority (Supplementary Appendix Table A10). We also considered differences between Democrats and Republicans, excluding independents. There, we find that Republicans are more averse to media coverage, whereas Democrats are more responsive to authority and averse to supermajoritarian voting requirements (Supplementary Appendix Table A11).

On net, reforms that would enhance the ability of elected officials to advance a policy agenda, whether by increasing the authority of the office or reducing the supermajoritarian threshold needed to pass legislation, would have no impact on the proportion of women or working-class candidates. Such changes, however, would produce a field of candidates that is proportionally older, whiter, and more Democratic in orientation. We do not find any evidence, meanwhile, that increases in staffing support would alter the composition of the candidate pools along any of these dimensions.

5.4. Additional factor analyses

We have estimated alternative versions of our main indices using a factor analysis of our newly collected data. The results are shown in Supplementary Appendix Tables A12 and A13, and the regression results using measures of quality and moderation based on these alternative measures are shown in Supplementary Appendix Table A14. All of the items have the expected sign in the construction of the first factors, and the subsequent results are very similar to our main results.

6. Discussion

The Founders worried a great deal about both the capacity of average citizens to select capable and representative leaders and the motivations of those who would seek to run. As James Madison lamented in Federalist 10, “Enlightened men will not always be at the helm.” His solution, of course, was not to change the character of citizens or devise ways for selecting only the virtuous among them. Rather, it was to erect institutions—separation of powers, multiple veto points, federalism, and all the rest—that would impede the ability of all politicians to exercise influence, and thereby limit the damage any one might cause.

So today, political observers routinely lament the rise of polarization among political elites and the paucity of high-quality candidates seeking office. Viewing the preponderance of ideological extremists and underqualified candidates seeking office, these observers take comfort in the founders’ handiwork, which makes it all but impossible for elected officials to accomplish very much in office. Extreme and lower-quality candidates may win elections, but at least they won’t be able to do anything of consequence. Political inefficacy is thus understood as a remedy to an undesirable political class.

Our findings reveal how this way of thinking is incomplete and possibly misguided. Reductions in authority, capacity, and opportunities to pass policy certainly mitigate the harm that a more extreme or less qualified politician can cause. But our findings suggest that these same reductions also dissuade moderates and highly qualified candidates from seeking elected office; in so doing, they exacerbate the very problems of polarization and mediocrity that are the cause of so much concern in our politics.

Voters may evaluate candidates differently when elected officials are more empowered to deliver on their campaign promises, inducing incentive effects that lie outside of the purview of this paper.Footnote 13 But the selection effects documented here reveal benefits from raising the stakes of electoral contests at exactly the time when there is so much to lament about our mass politics. This reform agenda presents risks. When conditioning on the existing candidate pool, relaxing impediments to lawmaking improves the chances that extreme or objectively bad ideas will be written into statute. But the findings in this paper suggest that conditioning on the existing pool of candidates is shortsighted. Some of the more moderate and more qualified potential candidates who currently are standing on the political sidelines may choose to run if they can reasonably expect to exercise meaningful influence upon winning an elected office.

Two more general lessons follow from this analysis, the first of which concerns the perpetuation of high-level ailments in American politics. Polarization, gridlock, and dysfunction may not just be the result of extreme and unqualified politicians. They also may be the cause. Seeing few opportunities to make a real difference in politics, more moderate and more qualified individuals may choose to take their talents elsewhere; and in so doing, they leave behind a pool of candidates that is less representative of an American public that is decidedly moderate in orientation (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Hill, Lewis, Tausanovitch, Vavreck and Warshaw2023), and less capable of acting on its interests. Thus ensues a vicious cycle in which polarization, gridlock, and dysfunction propagate, and the effectiveness of government degenerates.

The second general lesson concerns the larger class of institutional reforms that might alter the composition of electoral contests. In this paper, we focus on characteristics of an elected office that allow politicians to advance a policy agenda. But other office characteristics—the flexibility of work hours, the nature of involvement in different policy domains, the quality of office culture, or the opportunities for career advancement—also may stimulate interest not just of more qualified and more moderate citizens, but of other kinds of individuals who are featured prominently in the larger candidate-entry literature. By focusing squarely on features of the job for which candidates are running, we may yet uncover a whole host of institutional reforms that convince more women, members of the working class, underrepresented minorities, younger people, and any number of other constituents to run for public office.

7. Conclusion

Whereas the existing candidate-entry literature focuses nearly exclusively on factors that precede the casting of actual votes, we look to what follows. In particular, we focus on the ability of elected officials to advance a policy agenda, and we then investigate its implications for more moderate and more qualified citizens—who, in our sample, already are registered to vote and are attentive to politics—to express interest in running for public office.

Among all the factors we manipulate in our conjoint experiment, an increase in authority vested in a public office is the only means that seems likely to generate a more moderate candidate pool. When trying to enlist more qualified candidates to run for office, increases in authority coupled with higher levels of staff support and a straight majoritarian legislative voting rule all appear useful. By contrast, other factors that have been the subject of long-standing scholarly attention yield mixed returns. Higher salaries and lower fundraising obligations, for instance, both increase the average quality of the candidate pool, although neither can be expected to straightforwardly reduce observed levels of electoral polarization.

Who runs for office, we have learned, crucially depends upon what they are running for. The findings we present, however, hardly exhaust the opportunities for empirical investigation. We encourage future research to investigate how other changes to an elected office might affect the willingness of still other constituencies to seek public office. Future research should also evaluate whether our findings generalize to other elected positions beyond local city council seats and other samples of citizens, should develop and validate better measures of moderation, quality, and other characteristics of theoretical interest, and should further explore what makes authority especially attractive to moderate and high-quality potential candidates: differences in public service motivation or willingness to govern, differences in anticipated pivotality or effectiveness, or something else? Through this research, we anticipate that we may collectively recover a better understanding of how the design of political institutions affects who is willing to compete in politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10076. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BQAHGZ.

Acknowledgements

We thank David Broockman, Ethan Bueno de Mesquita, Nick Carnes, Amanda Clayton, Alex Fouirnaies, Bobby Gulotty, Andy Hall, Jennifer Lawless, Daniel Moskowitz, Julia Payson, Anton Strezhnev, Adam Zelizer, and seminar participants at the University of Chicago, the University of Oregon, Yale University, and Columbia University for helpful comments.

Competing interests

None declared.