Introduction

In a growing number of countries, populists are in power. After witnessing sweeping institutional reforms in Hungary and Poland and the aggressive rhetoric of the Trump administration, many fear the impact that populist governments may have on the quality of democracy. While there is a scholarly consensus that the populist ideology clashes with some central tenets of liberal democracy in theory (Albertazzi & Mueller, Reference Albertazzi and Mueller2013; Rummens, Reference Rummens, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati2019), whether or not the participation of populist parties in government constitutes a threat to democracy in practice has been highly debated. Among scholars of populism, there are essentially two positions: The inclusion–moderation hypothesis states that populist parties become more moderate when they come into power. The nature of electoral competition, a shifted focus towards the provision of public goods, and the need to compromise with coalition partners cause populist parties to behave more like mainstream parties (Berman, Reference Berman2008). Critics, however, contend that populist parties maintain their extreme policy positions and rhetoric even once they are in office (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Reference Akkerman and Rooduijn2015; Schwörer, Reference Schwörer2021) and find that populist governments are associated with a decrease in the rule of law and media freedom (Huber & Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016, Reference Huber and Schimpf2017; Houle & Kenny, Reference Houle and Kenny2018; Kenny, Reference Kenny2020).

The answer to whether or not populist parties in government pose a threat to democracy requires a measure of how often the policies enacted by these governments transgress the boundaries established by democratic constitutions. While previous studies have analysed the party positions expressed in the manifestos and communication of populist parties while they are in office (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Reference Akkerman and Rooduijn2015; Schwörer, Reference Schwörer2021), we know much less about the content of their actual policies. In this paper, we shed light on the policies of coalition governments that included a populist party by analysing constitutional court decisions. As is the case with all governments – populist and non‐populist – many laws are reviewed by constitutional courts. We contend that if populist policies erode constitutional democracy and limit minority rights, we should see courts striking down laws passed by these governments more often than those enacted by non‐populist governments. If, on the other hand, populists moderate their policies once they enter (coalition) governments, we should see no differences between the policies of populist and non‐populist governments in terms of their constitutionality.

We explore the relationship between populist parties in government and constitutional courts, focusing on the case of Austria. We draw on Austrian data for several reasons. First, the country experienced several governments that included populist parties. Therefore, we can rely on a large number of court decisions and governments with varying populist participation levels. Second, all governments with populist participation in Austria were coalition governments. When populist governments possess large electoral majorities, they can implement sweeping judicial reforms that undermine judicial independence. If constitutional courts can no longer act impartially, some populist policies may prevail, even though fully independent courts would have held them unconstitutional. However, coalition governments usually lack the electoral majorities and willingness to overhaul the judicial system or pass constitutional amendments. Finally, the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) is one of the most prominent and successful right‐wing populist parties in a Western democracy. Unlike many other populist parties that have emerged more recently, the FPÖ has a long history and has been in government multiple times at the federal and state levels.

Our empirical analysis relies on a novel dataset consisting of more than 2000 decisions made by the Austrian Constitutional Court (VfGH) between 1980 and 2021. In line with the predictions of the inclusion–moderation hypothesis, the results show that the court did not overrule laws enacted by governments with populist parties more often than it overruled laws enacted by non‐populist governments. Even for policy issues that are of particular importance for populist parties, such as migration and security, we do not find any evidence that laws passed by populist parties in government implement unconstitutional policies more often than those passed by non‐populist governments.

Our findings provide an interesting contrast to other recent studies that have found that populist parties maintain extreme positions even when they are included in the government (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Reference Akkerman and Rooduijn2015; Albertazzi & McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2005; Schwörer, Reference Schwörer2021). To explain these differences, we contend that it is essential to distinguish between positions expressed in populist party manifestos or in the rhetoric of politicians and the policies implemented by populist parties in government. We argue that the mechanisms that underlie the inclusion–moderation hypothesis apply much less to the former than to the latter. Party manifestos and rhetoric are primarily a means to communicate policy positions to the voters and the party base. Unlike actual policy, manifestos and rhetoric are much less subject to the moderation pressures of a coalition partner and the attention shift towards the provision of public goods induced by the responsibility of government. In fact, by communicating extreme positions in their party manifestos and speech but moderating their actual policies, populist parties manage to overcome a key dilemma of government participation: taking on government responsibility counteracts the anti‐elite narrative that populist parties rely on to draw support from their party base.

We make several contributions to the research on populism and judicial politics. First, our paper is – to our knowledge – the first to empirically study the impact of populists in power using court data. Recently, in a review of the literature on populism, Rooduijn (Reference Rooduijn2019) pointed out that the study of populism would benefit from increased interaction with adjacent fields. Our paper attempts to build a bridge between populism research on the one hand and the growing interest in populism among scholars of judicial politics on the other. Second, although research on populism has been very prolific in the last decade, we still know little about the relationship between courts and populist parties. Constitutional courts are not only a frequent target of populist criticism, but they also play an important role as guardians against attacks on the core values of liberal democracy and minority rights. While legal scholars are increasingly interested in the proper role of courts confronted with the populist ideology (Graber et al., Reference Graber, Levinson and Tushnet2018; Prendergast, Reference Prendergast2019; Tushnet & Bugarič, Reference Tushnet and Bugarič2021), the topic has not received much attention from social scientists (for an exception, see Mazzoleni & Voerman, Reference Mazzoleni and Voerman2020; Voeten, Reference Voeten2020). Finally, we introduce a novel and comprehensive dataset of decisions made by the Austrian Constitutional Court.

Populists in power: A threat to democracy?

The relationship between populism and democracy has been widely debated over the last few decades (Abts & Rummens, Reference Abts and Rummens2007; Canovan, Reference Canovan1999; Laclau, Reference Laclau2005; Mény & Surel, Reference Mény and Surel2002; Mouffe, Reference Mouffe2005; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012b; Weyland, Reference Weyland2020). While not all scholars agree on the exact nature of this relationship, a consensus that populism is hostile to the institutional and pluralistic elements of liberal democracy has emerged (de La Torre & de Lara, Reference de La Torre and de Lara2020; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012a; Müller, Reference Müller2016). Recent experiences in Hungary (Batory, Reference Batory2016) and Poland (Markowski, Reference Markowski2019), where populist governments hold large electoral majorities, exemplify the incompatibility of populism and liberal democracy. There is much less empirical evidence concerning the effect of populist parties in power on the quality of democracy when governments lack the majorities needed to implement sweeping institutional reforms. The inclusion–moderation hypothesis states that including populist parties in government can ‘tame’ them (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016a; Berman, Reference Berman2008). However, recent empirical studies suggest that populist parties maintain their extreme party positions and rhetoric even after being included in government (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Reference Akkerman and Rooduijn2015; Schwörer, Reference Schwörer2021).

In the following subsections, we review the literature on populism, populist parties in government and their relationship with liberal democracy. Then, we argue that the mechanism underlying the inclusion–moderation hypothesis is much stronger in situations in which the coalition partner can successfully constrain the populist party. While the rhetoric and policy agendas outlined in manifestos can be decided upon independently by the populist party, the policy output is more likely to be moderated by the consideration of the coalition partner's position as a veto player.

Populism and constitutionalism

According to the extensively used ideational approach, populism is understood as a ‘thin‐centred ideology concerning the structure of power’ (Abts & Rummens, Reference Abts and Rummens2007, p. 408). Populism's concept of a power structure is defined by three key elements: the people, the general will and the elite. The people are a homogeneous group with a general will, and they are the sole sovereign (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017). While populist parties generally conceptualize the people as a homogeneous group, they differ on how this group is defined: Left‐wing populism tends to distinguish the people from the elite in socio‐economic terms, while right‐wing populist parties invoke ethnonational characteristics (Huber & Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2017). The enemy of the people is the elite (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017). The separation between these two groups is a moral one. While the ‘pure’ people are regarded as ‘good’ and as having ‘common sense’, the elite are seen as corrupt and as ‘traitors’ of the people (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004). Populists portray the elite and their institutions as a small, powerful and privileged group suppressing the interests and values of the people in the ‘real’ world (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017). As a consequence, populists argue that power needs to be given back to the people with whom it properly resides.

Many scholars have observed that populism and the ideals of liberal democracy are incompatible with one another (Abts & Rummens, Reference Abts and Rummens2007; Müller, Reference Müller2016; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati1998, Reference Urbinati2019). Liberal democracy is based on pluralism and the idea that no politician can represent ‘the people’ as a whole (Rummens, Reference Rummens, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017). To ensure the liberties of the people that are not part of the current majority, liberal democracies complement popular sovereignty with the rule of law, which is often embodied in a constitution (Habermas & Rehg, Reference Habermas and Rehg2001). An independent, counter‐majoritarian institution – a constitutional court – is tasked with interpreting and applying the constitution (Kelsen, Reference Kelsen1931).

In contrast, populists have a Schmittian understanding of democracy (Abts & Rummens, Reference Abts and Rummens2007). Schmitt argued that the people are only sovereign if they can breach the rule of law without consequences (Schmitt, Reference Schmitt1929). Constitutions, and the courts interpreting them, place restrictions on popular sovereignty that directly clash with the populist ideal of extreme majoritarianism. The populist conceptualization of the people as a homogeneous group makes populism necessarily anti‐pluralistic (Abts & Rummens, Reference Abts and Rummens2007; Müller, Reference Müller2016; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2017). In populism, ‘[c]onstituent power, rather than being the power of the multitude, becomes the power of the majority’ (Blokker, Reference Blokker, Delledonne, Martinico, Monti and Pacini2020).

The tension with liberal democracy becomes apparent in frequent populist attacks on constitutional limitations, courts and judges. In the United States, Trump wrote that Supreme Court decisions ‘tell you only one thing, we need NEW JUSTICES’ (Wagner, Reference Wagner2020, emphasis in original). In Austria, a constitutional court's decision was called a ‘carnival joke’ (Faschingsscherz) (Der Standard, 2004) by an FPÖ politician. The German right‐wing populist party Alternative für Deutschland claimed that courts have lost their common sense and labelled them the gravediggers of the rule of law (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 2018). In Israel, the government initiated laws enabling the Knesset to outvote judicial review decisions (Roznai, Reference Roznai, Graber, Levinson and Tushnet2018). These instances show that populists regard courts and judges as part of the elite and perceive them not only as obstacles but as proactive enemies of the people. Judges are seen as illegitimate legislators, acting only in their own self‐interest and in the interest of minorities (Blokker, Reference Blokker2019).

Nevertheless, not all scholars see populism as universally detrimental to democracy. Laclau (Reference Laclau2005) argues that strong populist parties may contribute to the re‐politicization of a society. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012a) contend that populism can have both positive and negative effects on democracy. According to them, the direction of the effect depends on the government status of populist parties. In government, populist parties try to weaken institutions and checks and balances, while in opposition they can improve the quality of democracy through the inclusion of minorities and the revitalization of conflictive democracy (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012a). The inclusionary aspect of populism is also emphasized by de La Torre and de Lara (Reference de La Torre and de Lara2020), who argue that political participation increases when populists are in office but acknowledge that it often comes at the ‘cost of pluralism’ (de La Torre and de Lara, Reference de La Torre and de Lara2020, p. 1454).

Populism in government

Participation in government poses a challenge for populist parties. On the one hand, populist parties are, like other parties, office‐seeking (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016a; Krause & Wagner, Reference Krause and Wagner2021). On the other hand, government participation runs counter to the anti‐elite narrative and critical view of liberal democratic systems espoused by populist parties. Populist voters may see government participation, cooperation with other parties and policy compromises as a betrayal of core beliefs. While the populist aspects of parties make them effective in opposition and elections, their ideology can become disadvantageous in public office (Heinisch, Reference Heinisch2003).

The inclusion–moderation hypothesis states that competing for office and participating in government leads to the moderation of radical parties (Berman, Reference Berman2008). To be electorally competitive and to grapple with the realities of governing, populist parties have to give up their more extreme positions, at least to some extent. The mechanisms underlying the inclusion–moderation hypothesis are threefold. When competing for office, parties must appeal to the median voter to attract sufficient electoral support (Berman, Reference Berman2008). This logic implies that populist parties who seek participation in government often have to appeal to a larger share of the electorate rather than just to radical, protest or niche voters. While this mechanism is particularly prevalent in two‐party systems, the incentives motivated by coalition considerations are stronger in multiparty systems. To signal their interest in cooperating with mainstream parties, populist parties need to moderate their policy agendas to be considered as possible coalition partners (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016a; Krause & Wagner, Reference Krause and Wagner2021). In coalition negotiations, parties have to compromise further to agree on a given policy (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016a; Berman, Reference Berman2008). Once in office, populist parties must prove that they can deliver public goods (‘filling potholes'), leaving less room for ideological messaging (Berman, Reference Berman2008).

Whether or not these mechanisms are effective is widely debated (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016c; Akkerman & Rooduijn, Reference Akkerman and Rooduijn2015; Albertazzi & McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2016; Schwörer, Reference Schwörer2021). Existing studies have analysed the rhetoric or policy agendas of populist parties (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Reference Akkerman and Rooduijn2015; Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016b; Bernhard, Reference Bernhard2020; Schwörer, Reference Schwörer2021; van Spanje & van der Brug, Reference van Spanje and van der Brug2007). Only a few studies find a moderating effect (Bernhard, Reference Bernhard2020; van Spanje & van der Brug, Reference van Spanje and van der Brug2007), while most empirical studies conclude that populist parties do not become more like mainstream parties when they participate in government (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Reference Akkerman and Rooduijn2015; Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016c; Albertazzi & McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2005; Frölich‐Steffen & Rensmann, Reference Frölich‐Steffen, Rensmann, Delwit and Poirer2007; Schwörer, Reference Schwörer2021). Instead, the policy positions of populist right‐wing parties have become even more radical over the last two decades, despite increased government participation (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016b).

However, the analysis of policy agendas and party rhetoric provides only a partial test of the inclusion–moderation hypothesis. We argue that if populist parties become more moderate, this should be visible primarily in their actual policy output. Unlike party manifestos and rhetoric, the policy output is much more subject to the moderation pressure of coalition partners and the need to deliver public goods. Policy agendas and rhetoric, on the other hand, are much more targeted towards populist party supporters and therefore are less likely to be moderated. In fact, by maintaining more radical positions in party manifestos and rhetoric while implementing rather moderate policies, populist parties address the key populist dilemma of government participation. Faced with the trade‐offs of entering a coalition government, populist parties need to find ways to reduce the costs of governing (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016a). One way to do this is for populist parties to have ‘one foot in and one foot out’ (Albertazzi & McDonnell, Reference Albertazzi and McDonnell2005, p. 953). Populist parties can use manifestos and rhetoric to uphold their anti‐elite narrative, shift blame and mobilize their supporters. Fostering their anti‐elite narrative in policy agendas and rhetoric allows populist parties to act as the ‘opposition in government’ (Albertazzi et al., Reference Albertazzi, McDonnell and Newell2011, p. 484) despite moderation in their policy output.

While populist parties do not necessarily share (extreme) policy positions (Bartha et al., Reference Bartha, Boda and Szikra2020), we argue that they are more likely to transgress constitutional boundaries than mainstream parties if this is necessary for pursuing their policy goals. While policy stances outside the constitutional scope are not exclusive to populist parties, we argue that due to their contempt of counter‐majoritarian institutions, populist parties would prefer not to moderate their policies in these instances, unlike mainstream parties. This is an issue, particularly if populists want to govern with liberal democratic parties. To successfully cooperate with mainstream parties, populist parties need to moderate their policies outside the constitutional scope (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange, Rooduijn, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016a; Berman, Reference Berman2008). How often this occurs depends on the populist party's specific ideology. Populist radical right parties that base their ideologies on nativism and authoritarianism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007, Reference Mudde2013), which, for example, often clash with laws on equal treatment, can be expected to cross constitutional boundaries more frequently than left‐wing populists. Still, the common contempt for constitutional provisions of populist parties increases the likelihood of transgressing these boundaries for populists of all kinds.

In the following sections, we scrutinize the inclusion–moderation hypothesis by analysing policy outcomes based on a novel dataset of constitutional court decisions made in Austria between 1980 and 2021.

Case selection and institutional background

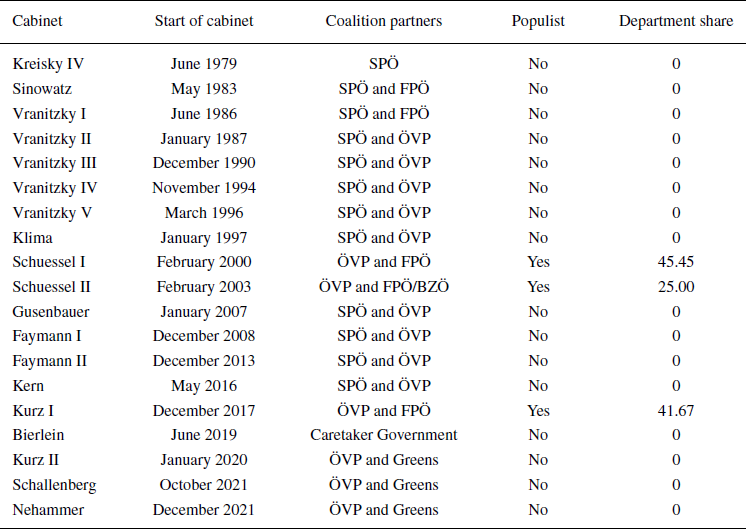

Austria is a prominent and widely discussed example of populist government participation (Fallend, Reference Fallend2004, Reference Fallend, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012; Fallend & Heinisch, Reference Fallend and Heinisch2016). Since 1980, the FPÖ, and its splinter party, the BZÖ, have been junior coalition partners in five out of 19 cabinets. In three of these cabinets, we consider the FPÖ or BZÖ as populist. The FPÖ took a populist turn once Haider took over the party in 1986 (Fallend, Reference Fallend, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012; Pelinka, Reference Pelinka, Frölich‐Steffen and Rensmann2005). We do not consider the party populist in the Sinowatz or Vranitzky I cabinets. Table 1 provides an overview of the legislative periods and governments included in our study, information concerning whether or not a populist party was a junior coalition partner, and the share of departments occupied by politicians from one of the populist parties.

Table 1. Cabinets included in the dataset

There are several reasons that Austria is an attractive case to study populist government participation. First, FPÖ/BZÖ participation in government is not clustered in one particular period. Second, the FPÖ/BZÖ has been in government with different coalition partners. Third, the strength of the FPÖ/BZÖ as a junior coalition partner varies, as indicated by the share of ministries occupied by the populist party. In all cases, the FPÖ/BZÖ held a substantial number of ministries. In two legislative periods (Schuessel I and Kurz I), the party held an almost equal share of ministries compared to the coalition partner. These facts ensure that our results are not driven by a particular time period, a particular coalition or the negligible influence of the FPÖ/BZÖ in the governing coalition.

Today, the FPÖ is one of the most successful right‐wing populist parties in Europe and has been described as a prototype of populism in Western Europe (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2013; Pelinka, Reference Pelinka, Wodak, Khosravinik and Mral2013). Various scholars classify the FPÖ and BZÖ as populist parties. They are included in The PopuList, a dataset on populist parties in Europe (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, van Kessel, Taggart, Mudde, Lewis, Halikiopoulou, de Lange, Pirro and Froio2019). Furthermore, the FPÖ scores high in the Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA) (Meijers & Zaslove, Reference Meijers and Zaslove2021). However, the FPÖ only took its populist turn in 1986 after the liberal wing of the party lost power (Fallend, Reference Fallend, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012). This can be observed in the V‐Party dataset, which is based on expert assessments (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasoglu, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken, Laebens, Medzihorsky, Neundorf, John Reuter, Ruth‐Lovell, Weghorst, Wiesehomeier, Wright, Alizada, Bederke and Seim2022). The FPÖ's populism score rises above 0.5 (on a 0 to 1 scale) only in 1986 (see the Online Appendix section A1).

Anecdotal evidence underscores the tension between the FPÖ and BZÖ as populist parties and constitutional democracy. A prominent example is the Ortstafelstreit. In the region of Carinthia, where the FPÖ (later the BZÖ) was the major force in government, its longtime leader Jörg Haider refused to implement bilingual town signs after the VfGH had ruled that this was required by the constitution (Heinisch, Reference Heinisch2003). The stand‐off went so far that FPÖ politicians called the constitutional court decision ‘politically void’ (politisch nichtig) (Der Standard, 2002, 2007; Heinisch, Reference Heinisch2003) and – as mentioned previously – a ‘carnival joke’ (Faschingsscherz) (Der Standard, 2004). The constitutional court's president addressed the danger of these verbal attacks in public speeches, the VfGH's annual report and interviews (Der Standard, 2002, 2007; Verfassungsgerichtshof Österreich, 2002).

On the federal level, the FPÖ's hostility towards liberal democratic institutions can be observed in their party manifestos. In the 1990s, the party developed a concept for democratic reform that aimed to implement more plebiscites, disempower political parties and centralize power (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, 2005; Haider, Reference Haider1994; Heinisch & Hauser, Reference Heinisch, Hauser, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016). Part of the concept, which called the current democratic system an authoritarian state (Obrigkeitsstaat), was a new system for appointing high court judges (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, 2005). These claims, as well as the FPÖ's campaign against the constitutional court, ‘constituted an area where the party strayed furthest from the mainstream’ (Heinisch & Hauser, Reference Heinisch, Hauser, Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016, p. 77). These instances show that the FPÖ did and does hold preferences outside the constitutional scope. Whether or not they were able to systematically transform these interests into policy outputs is the question at hand.

The mainstream coalition partners tried to ‘tame’ the FPÖ. For a long time, cooperating with the FPÖ was not considered as an option by the mainstream parties in Austria. Its most frequent coalition partner, the ÖVP, stated that the FPÖ could only govern once the party was inside the ‘constitutional arch’ (Fallend, Reference Fallend2004, p. 122), pushing the FPÖ to give up some of its most radical ideas. Before the FPÖ entered the government, the party toned down its most radical rhetoric and expanded its policy agenda, including, for example, more socio‐economic demands (Fallend, Reference Fallend2004; Pelinka, Reference Pelinka, Frölich‐Steffen and Rensmann2005), to build common ground for possible coalitions as well as to have more policies to trade‐off in negotiations.

Austria is also a promising case because of its constitutional court. Our empirical analysis evaluates the policies of populist and non‐populist legislators in terms of their constitutionality by analysing constitutional court decisions. However, the court's verdicts can only be seen as an objective measure of constitutionality if the judges can act independently and are isolated from political pressure. When populist governments command large electoral majorities, they can reform judicial procedures and undermine judicial independence. In Austria, the FPÖ never obtained a level of electoral support that would have allowed them to implement sweeping judicial reforms.

When it was founded in 1920, the VfGH was the first centralized high court, and it has since been used as a model for many European constitutional courts (Stone Sweet, Reference Stone Sweet2000). Most judges on the VfGH are appointed by the first chamber, the Nationalrat, and the federal government (9 out of 12). Only three are nominated by the second chamber, the Bundesrat. For a long time, the nominations were dominated by the grand coalition, since the federal government usually also holds a majority in parliament. This changed at the beginning of the 2000s when the FPÖ joined the government, and it changed again with the new coalition of Conservatives and Greens in 2020. Still, the judges are considered to be independent of political parties (Gamper & Paleroma, Reference Gamper, Paleroma, Harding and Leyland2009; Pelinka, Reference Pelinka, Ismayr and Groß2003; Ehs, Reference Ehs2015). The judges hold office until they turn 70 and do not have to face re‐election. To ensure the independence of each of the judges, the court does not publish their individual votes and does not allow dissenting opinions (Ehs, Reference Ehs2015), even though politicians consider implementing the latter from time to time. At the beginning of a case, one of the justices is assigned as the rapporteur. This justice researches the case, proposes whether or not a case should be accepted and writes the first draft of a decision, which is then discussed in the court's (non‐public) deliberation process. The decisions are written in a very formal language, and the VfGH's communications attempt to ensure that people perceive the institution as a neutral, law‐abiding actor.

However, even when courts are independent, their decisions might be influenced by strategic political considerations (Engst, Reference Engst2021; Vanberg, Reference Vanberg2001, Reference Vanberg2015). Vanberg (Reference Vanberg2001) argues that under certain circumstances, constitutional courts are motivated to misrepresent their true assessments because they fear that the legislature might not comply with the court's ruling, which could erode its authority. Especially when cases are not covered extensively by the news (‘low transparency'), evasion attempts by the legislature may be unnoticed and may not create a public backlash. There are at least two reasons that the Austrian Constitutional Court is unlikely to amend its opinions due to these kinds of strategic considerations. First, the court issued decisions on only 14.4 per cent of laws when the cabinet that implemented the law under consideration was still in office. In other words, in the large majority of cases, the cabinet that enacted a particular law was already out of office when the court finalized its review process. Therefore, the court's fear that the legislature would evade its decision is mitigated. Second, the Austrian Constitutional Court has consistently been one of the most trusted institutions in Austria and scored much higher in a trust‐index survey than other political actors and institutions (OGM & APA, 2022). A high level of public support for the court is crucial to ensuring that judges do not amend their opinions to avoid conflicts with the executive branch (Caldeira & Gibson, Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992, Reference Caldeira and Gibson1995; Carrubba, Reference Carrubba2009; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Vanberg, Reference Vanberg2001, Reference Vanberg2005). We include a graph on trust in Austrian institutions in the Online Appendix (section A.1). V‐Dem data have ranked the independence of the Austrian Constitutional Court consistently high (see Online Appendix Section A.1; Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Alizada, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Hindle, Ilchenko, Kinzelbach and Ziblatt2022b; Maerz et al., Reference Maerz, Edgell, Hellemeier and Illchenko2022), implying that the court seldom or never takes decisions that ‘merely reflect government wishes’ (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova and Ziblatt2022a). This can also be seen in the aforementioned decision on bilingual town signs. Instead of backing down, the court remained assertive and started to engage in the discussion publicly in interviews to ensure compliance with its decision (Der Standard, 2001c, 2001b, 2001a).

With its independent constitutional court and recurring populist government participation, Austria allows us to measure the impact of populist policies through constitutional review. We elaborate on our approach to measuring the policy impact in the next section.

Data and empirical strategy

The key challenge of our study is to develop a measure of the impact of populist parties in government on policy. Above, we have argued that a populist ideology often causes parties to push and overstep the boundaries of constitutional democracy and its institutions. If populists in government follow through and translate their agenda into legislative activity, this should be reflected in the number of laws repealed by high courts and clashes with the judiciary. Therefore, we utilize the decisions made by constitutional courts as a measure of the constitutionality of policies.

Our empirical analysis is based on a novel dataset of all published decisions, 3163 in total, made by the Austrian Constitutional Court between 1980 and 2021. The VfGH is the only court in Austria that is allowed to review and invalidate acts by the government. All decisions were obtained from the Legal Information System (RIS), which provides decisions online from 1980 onward. Lawsuits can be filed by different actors. Lower courts or the constitutional court itself can initiate a review process if they are concerned that a law they have to apply in a pending case might be unconstitutional. Individuals can ask the constitutional court to review a law if they claim that it violated their rights. Abstract review can be initiated by provincial governments or a third of the members of either the national parliament or the federal council. Abstract review is used seldom; only 3.5 per cent of the cases in our dataset were initiated by political actors. Most of these cases were initiated either by a third of the national parliament or by a provincial government; only in a handful of cases did a third of the federal chamber ask the court to review the legislation. In general, a large share of the reviews are initiated by the lower court or the VfGH itself (45.4 per cent) or by individuals (50 per cent).

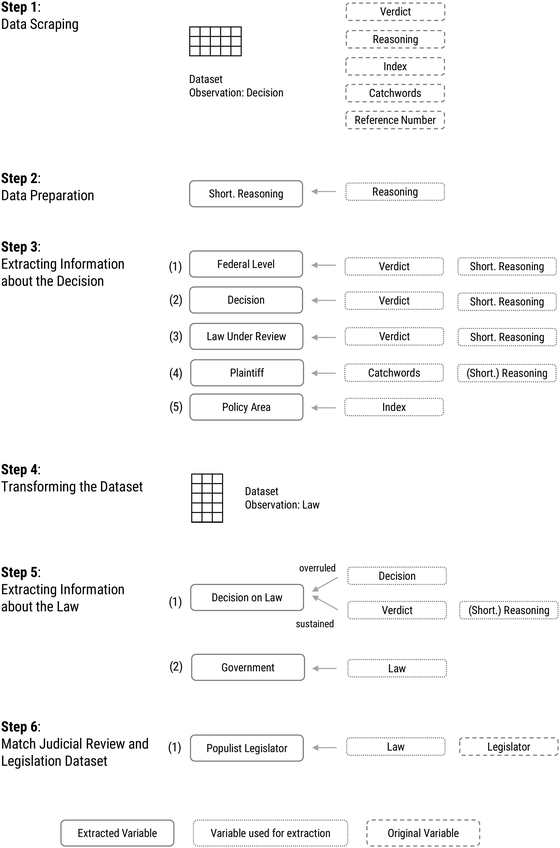

We extracted the relevant information from the decision documents. The published decisions of the court roughly follow a common structure. Each decision document contains the verdict, a justification, the index, several catchwords and a reference number. To prepare the data for further processing, we created a shortened version of each justification by removing all legal arguments in the reasoning that contain no important information for this study. From the pre‐processed decision text, we automatically extract the laws under review in the case, whether these laws correspond to federal or state laws, and, importantly, the court's decision. Furthermore, we extract the identity of the plaintiff from the decision document's catchwords and reasoning and the corresponding policy area from the index.

A natural starting point would be to conduct the analysis on the level of the decision. However, in some cases, the court reviews more than one law in the same decision. Thus, in the same decision, the court may uphold one government law while repealing another. Moreover, since the court can review multiple government laws in a single decision, it is also possible that the laws discussed in a single decision originate from different governments. To avoid any ambiguity in the data, we use each law under review as the unit of analysis. On the law level, we then identify for each law which government was in power at the time of the decision. Figure 1 summarizes most of the steps of the data collection process.

Figure 1. Data extraction and collection.

To identify whether or not the initiator of a law was part of a populist party, we further scraped a dataset of all Austrian legislation since 1980, including the federal law gazette number, date, and name of each law. We used the federal law gazette, which also includes either information on the legislating department or a weblink to the bill on the parliament website. For laws passed before 2004, we had to use the parliament website to obtain information on the department. In cases in which the bill was initiated by a member of parliament or a committee, we also used the parliament website to scrape this information. In the next step, we checked whether or not a department was held by either an FPÖ or BZÖ politician at the time that a bill was brought forward, or we checked whether or not one of the members of parliament who initiated a bill was a member of the FPÖ or BZÖ. If a bill was initiated by a committee, we considered the initiators to be non‐populist. We then matched the federal law gazette number in the legislation dataset with the number in the judicial review dataset to determine which laws under judicial review were initiated by populist actors.

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable decision captures the verdict of the court and is coded 1 if a complaint was sustainedFootnote 1 and consequently the law was invalidated; it is coded 0 if the complaint was overruled. For cases in which the court decided to partly invalidate some parts of a law and uphold others, decision is coded 1.

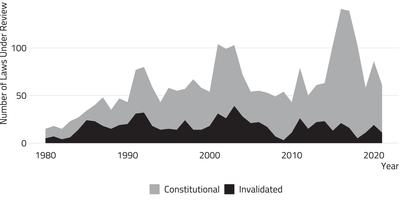

Figure 2 displays the total number of laws under review included in our data for each year, distinguishing between invalidated and upheld laws. On average, our data contain decisions on 64 laws for each year. In the early 1980s, fewer published decisions are available compared to more recent years. The figure indicates that especially more recently, the majority of complaints are overruled. Nevertheless, sustained complaints are not rare. Overall, the court invalidated 30.8 per cent of all of the laws that were under review.

Figure 2. Total number of complaints for which decisions were made.

Main independent variable

Our main independent variable concerns whether or not a law was brought into parliament by a member of a populist party. If – after 1986 – either the department that drafted the legislation was held by the FPÖ or BZÖ or one of the members of parliament (MPs) that initiated the bill was a member of either of those parties, the independent variable is coded 1. As presented in Table 1, there were in total three governments with populist participation in power since 1980, as we do not consider the FPÖ populist until Haider became the chair. The dummy variable is 0 if a law was initiated by MPs from non‐populist parties,Footnote 2 if it was initiated by a department that was held by non‐populist parties, or if it was a committee bill. As an alternative operationalization, we use a binary variable that indicates whether or not a government included a populist party. The results are presented as a robustness check in the Online Appendix.

Control variables and estimation strategy

To account for confounding variables, we introduce several control variables. The question of whether or not populist parties become more moderate is particularly meaningful for their core policy areas, in which they exhibit the most radical preferences (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Reference Akkerman and Rooduijn2015). We control for three important policy areas: migration, security and social policies. Each variable is set to 1 if the law under review is within the respective policy area and is 0 otherwise. The FPÖ and BZÖ share key characteristics of right‐wing populist parties, including a focus on migration and law and order (Fallend, Reference Fallend, Mudde and Kaltwasser2012). Furthermore, these parties often focused on social policy in their election campaigns (Fallend, Reference Fallend2004). If these parties implemented more laws concerning these policy areas and, at the same time, if laws in these areas are inherently more or less likely to be repealed by the court, excluding these control variables could introduce bias. Furthermore, we use the policy area variables to test for possible interactions with our populist variable. For the interaction tests, we created a binary variable Pop Policy, which indicates whether or not a law falls within the domain of security, migration, or social policy.

The Austrian constitution makes it possible to pass laws as constitutional laws with a two‐thirds majority. This mechanism was used by the grand coalitions between the SPÖ and ÖVP to evade the implementation of judicial review outcomes (Lachmayer, Reference Lachmayer, Jakab, Dyevre and Itzcovich2017). We use a variable indicating whether or not a government had a two‐thirds majority in parliament to control for the possible effect of a government's ability to pass a law as a constitutional law. To control for the generally more successful litigation by courts, we include a variable that indicates whether or not the review was initiated by a lower court or the VfGH itself; this variable is coded 1 if this is true and is 0 otherwise. The same applies to reviews that were initiated by either a provincial government or a third of either the national parliament or federal chamber. We control for this by including the variable Abstract Review, which is coded 1 if the review was initiated by either of these actors and is 0 otherwise. If the propensity of the court acting as the plaintiff is correlated with populist parties in government, our results could be biased without the use of this variable. A recent study of the German Federal Constitutional Court demonstrates that government briefs are related to the probability that the court will overrule a complaint (Krehbiel, Reference Krehbiel2019). We control for this possible confounding variable by including a binary variable that indicates whether or not a government brief has been filed.

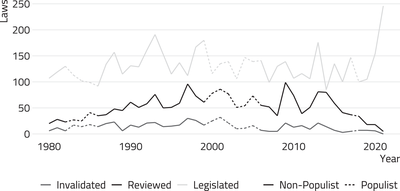

Finally, we include the total number of laws passed by each government over its time in office.Footnote 3 This variable controls for potentially different levels of legislative activity between populist and non‐populist governments. If, for example, the FPÖ and BZÖ struggled with settling into their new role in government and, consequently, did not enact any or enacted only a few laws, there would be little opportunity for courts to review laws. Figure 3 visualizes the total number of laws enacted each year between 1979 and 2021.Footnote 4 Overall, there are no substantial differences in legislative activity between populist and non‐populist governments.

Figure 3. Legislative activity over time.

Our dependent variable is binary, which calls for a logistic regression model. Moreover, our data exhibit a hierarchical structure. Court decisions on laws are nested in years and cabinets. Additionally, in a few cases (19.8 per cent), more than one law was under review in a single decision. To account for the hierarchical structure of the data, we adopt a multi‐level modelling strategy that includes random intercepts for years, cabinets, and decisions for various specifications. An alternative to the hierarchical models that we present in the main text is fixed‐effects specifications, which are presented in the Online Appendix (section B.3, Table 7).

Finally, we exclude all decisions in which the court only made decisions based on formal issues and limit the analysis presented in the main text to all decisions in which the court made decisions based on the substance of laws. Regression results that include all the decisions can be found in the Online Appendix in Sections B.1 and B.2 (Tables 4 and 6).

Results

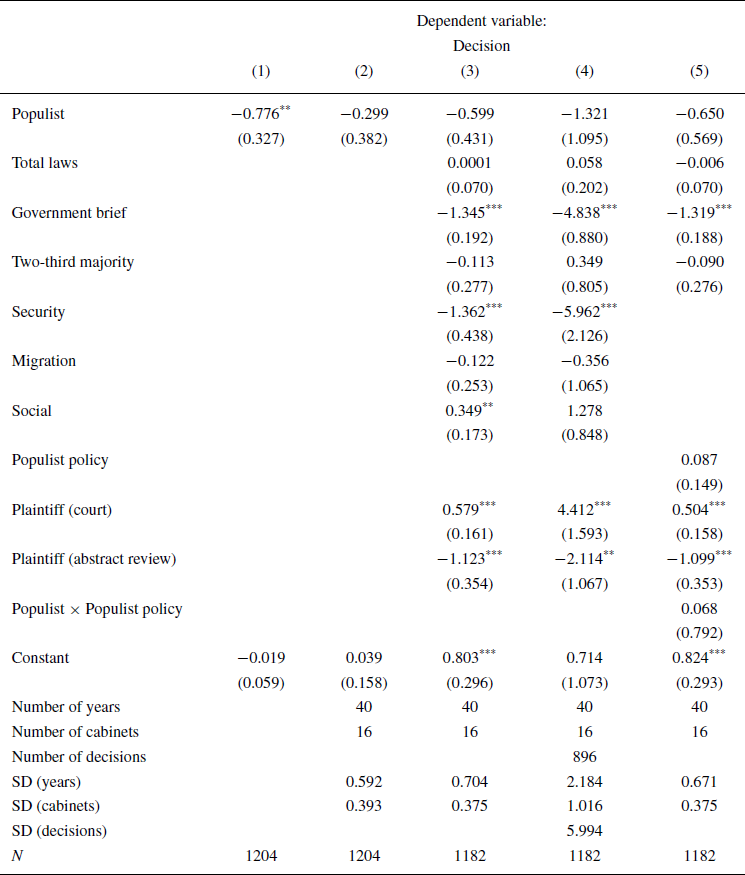

Table 2 presents the results of five logistic regression model specifications. All models include our main independent variable, which indicates whether or not a law was initiated by a populist actor (Populist). Except for model (1), all model specifications account for the hierarchical data structure by including random intercepts for years and cabinets (models (2)–(5)) and decisions (model (4)). The inclusion of random intercepts for years and cabinets accounts for 13.6 per cent of the variation in the outcome variable (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.136), which indicates that a multi‐level approach is an appropriate modelling strategy.

Table 2. Hierarchical logistic regression results

Note: *p<0.1;

![]() $^{**}$p<0.05;

$^{**}$p<0.05;

![]() $^{***}$p<0.01

$^{***}$p<0.01

Our theoretical discussion suggests that if populist parties moderate their policies once they are in office and become more like mainstream parties, we should find that the populist variable has no effect on the likelihood that a law will be repealed. Thus, the coefficient of Populist should be statistically insignificant and close to 0. On the other hand, if populist parties do not become more moderate, we expect a statistically significant, positive effect of our populism variable on the likelihood that a law will be repealed.

Our analysis finds no differences between populist and non‐populist governments with respect to the probability of repeals by the constitutional court. Only the first model, which includes nothing but our key independent variable, reports a statistically significant effect of Populist. However, the sign is negative. In all of our models that account for the hierarchical data structure, we do not find a significant relationship between the strength of the populist party in a coalition and how often laws transgressed the constitution. Across all model specifications, the effect is stable in size and remains far from conventional levels of statistical significance.

Model (5) includes an interaction term that considers interactions between the populist variable and the variable indicating whether or not a law falls in the domain of security, migration, or social policy (Populist Policy). The model provides no evidence that laws in these policy areas enacted by populist legislators are more likely to be invalidated than laws by non‐populist legislators. The Akaike Information Criterion and the log‐likelihood ratio test indicate that model (4) has the best model specifications.

Our main results support the inclusion–moderation hypothesis. They suggest that the FPÖ/BZÖ did moderate their policies to fit within constitutional boundaries when they entered the government. This also holds for policy areas that are of special concern for populist parties, such as security, migration, and social policy. While security policies are generally invalidated significantly less often than laws in other policy areas, this effect is independent of populists being in office.

Our results are robust to different measurements of the independent variable. Neither a change to a rougher measurement, which indicated whether or not a government includes a populist party (see Online Appendix Section B.2, Table 5), nor fixed‐effects specifications (see Online Appendix Section B.3, Table 7) show substantially different results. Our results are further robust to limiting the data to different time periods (see Online Appendix Section B.4, Table 8). In no model that we computed did we detect a statistically significant positive impact of governments that included populists on the likelihood that a law would be held unconstitutional. For some model specifications, the share of populist departments does become statistically significant. However, contrary to expectations, the direction of the effect is negative (see Online Appendix Section B.3, Table 7, model (4)).

Turning to the control variables, our results reveal several factors that determine the probability that a law will be invalidated. First, the identity of the plaintiff is crucial. Courts possess the necessary knowledge to assess whether or not a law is unconstitutional and if a review process might be successful. In line with this argument, we find that laws are more often found to be unconstitutional if a court acts as the plaintiff. On the other hand, the abstract review process is negatively related to the probability of success of a constitutional complaint compared to the baseline category (individual complaints).Footnote 5 Second, we find that a government brief in support of a law decreases the probability of a law being repealed. This finding corresponds with recent empirical evidence from the German Federal Constitutional Court (Krehbiel, Reference Krehbiel2019). Moreover, laws regarding security policy are less likely to be invalidated than other laws.

Alternative explanations

Three main alternative arguments could explain our finding that populist parties in government do not violate the constitution more often than non‐populist governments. First, one might argue that, with all else equal, laws initiated by populist legislators have a higher probability of becoming the subject of a case at the constitutional court than laws initiated by non‐populist legislators. In other words, these laws are being considered in court more often irrespective of their constitutionality. If this argument were true, it would attenuate the estimated effect of populist parties towards zero. In this case, even though the average law introduced by a populist legislator would have a higher likelihood of being unconstitutional, we would likely not find this effect in our analysis. This is because even laws initiated by a populist party that are extremely likely to be upheld by the court are becoming actual court cases, while the same laws initiated by non‐populist actors are not challenged in court.

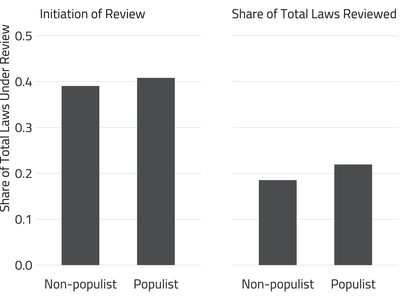

To explore this alternative explanation, we analyse whether or not there are any discernible differences between populist and non‐populist actors in terms of the likelihood that their legislation is reviewed in court. Figure 4 visualizes the frequency of lawsuits and the share of laws under judicial review in relation to the legislative activity of populist and non‐populist governments by policy area. There are no statistically significant differences in the total number of lawsuits and the number of laws reviewed by the court between populist and non‐populist legislators.Footnote 6 Overall, these results do not provide any support for the argument that the court has to review laws by populists more often than laws by non‐populists, irrespective of their underlying constitutionality.

Figure 4. Share of laws under review in relation to laws passed by the legislature. Initiation of review includes all review attempts (a law can be attempted to be reviewed multiple times). Share of laws reviewed only includes each law once if the court was asked to review it.

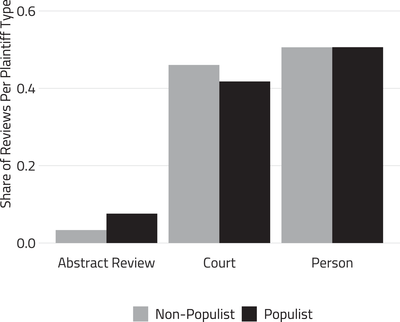

Another alternative explanation concerns the identity of the plaintiff. The results presented in Table 2 indicate that the constitutional court sustains complaints more often when courts act as plaintiffs compared to when individuals act as plaintiffs and abstract review. If populist laws were brought to court more often by individuals and politicians instead of courts compared to non‐populist laws, these complaints would have a lower likelihood of succeeding, which again could bias our estimate towards zero.

To account for this possibility, we control for the identity of the plaintiff in our main regression (models (3)–(5)). Additionally, Figure 5 visualizes the share of court cases for populist and non‐populist laws according to the type of plaintiff. The figure does not show any clear differences and, therefore, does not lend any support to the alternative explanation.Footnote 7

Figure 5. Share of laws reviewed per plaintiff for populist and non‐populist legislators.

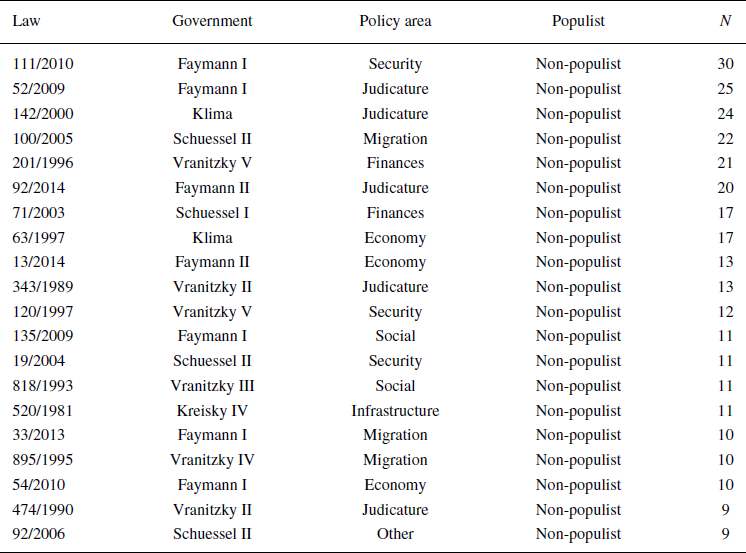

A final alternative explanation concerns the fact that in some cases the same law can be under review in several independent lawsuits at the same time. If the court decides to sustain one of these complaints, the other pending complaints become superfluous and might be thrown out by the court on that basis. If there are laws initiated by a populist party that triggered many lawsuits, and the same was not the case for non‐populist legislators, our estimate could be biased downwards. This is because there would be more superfluous and subsequently thrown‐out cases for populist laws than for non‐populist laws. Table 3 demonstrates that this is not the case. The table provides an overview of the most frequently reviewed laws in the dataset, the corresponding government and the policy area. None of the 20 most frequently reviewed laws were initiated by populists.

Table 3. Most frequently reviewed laws

In summary, none of the three presented alternative explanations that could account for the non‐significant effect of laws initiated by populists on the likelihood of a constitutional court repeal finds any support in the data. These robustness checks further strengthen the results presented in Table 2.

Conclusion

Do populist parties in government push for and overstep constitutional boundaries more often than non‐populist governments? In contrast to studies of populist policy positions and rhetoric, our findings show that the actual policies initiated by the FPÖ/BZÖ did not exceed constitutional boundaries more often than policies initiated by other Austrian governments. The results shed light on the behaviour of populist parties in government and in particular on the inclusion–moderation thesis. While populist parties may not moderate their positions on paper, they do moderate their actual policies to fit within constitutional boundaries in practice.

Some scholars have described populist (coalition) governments as a threat to liberal democracy and the rule of law (Huber & Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016, Reference Huber and Schimpf2017; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati1998, Reference Urbinati2019). At least with respect to the policies implemented by coalition governments with FPÖ/BZÖ participation in Austria, our findings suggest that this fear is unfounded. In line with the predictions of the inclusion–moderation hypothesis, populist parties seem to have moderated their policies once they were in power. However, our results cannot speak to the possible detrimental impact of populist rhetoric on public trust and the quality of democracy. Our study does not rule out the idea that populist parties constitute a threat to constitutional democracy when they govern with large electoral majorities and without the need to cooperate with coalition partners.

Importantly, in the case of Austria, the FPÖ/BZÖ always acted as a junior coalition partner. We can observe the effect of a coalition partner on the moderation of the populist party when we compare the Austrian federal governments with the regional Carinthian case. Having been the major actor in the Carinthian government for a long time, the FPÖ and later the BZÖ actively pushed for stand‐offs with the constitutional court, refusing to implement its decisions and starting a public quarrel with the VfGH (Heinisch, Reference Heinisch2003; Fallend & Heinisch, Reference Fallend and Heinisch2016). This was not the case for the federal government. Working with a coalition partner at all times, the populist parties were not able to push constitutional boundaries; instead, they moderated their policy output. The comparison of our results with the example from the region of Carinthia emphasizes the importance of the coalition partners of populists in enforcing liberal democratic values. If the populist party's coalition partner does not enforce these values, we cannot expect moderation, as the Carinthian experience suggests.

To stay in office, populists must do more than satisfy their coalition partner. To win enough votes in upcoming elections, they also need to fulfill at least some of their supporters’ expectations. Our results indicate that populists in office resolve this quandary by adopting a two‐pronged strategy. Instead of pushing for stand‐offs with the court frequently, populists in government pushed constitutional boundaries with specific larger legislative acts of importance to the populist electorate. Laws, such as the 2003 asylum law or 2019 welfare cuts (which targeted asylum seekers), signalled to populist voters that their party was trying to push through policies of importance to them, whether these policies are outside the constitutional scope or not. Moderating their actions when necessary to keep the coalition going, populists seem to use specific legislative acts and public communication to satisfy their electoral base.

A key implication of our findings for research on populism is that it is important to distinguish between the party manifestos of populist parties, populist politicians’ rhetoric and the actual policy content of populist parties in power. Hostile rhetoric and radical party manifestos do not automatically manifest themselves as laws that are detrimental to liberal democracy. Identifying the incompatibilities between the populist ideology and constitutional democracy in theory does not directly imply the incompatibility of the policies initiated by governments with populist participation and constitutional democracy in practice.

Our paper proposes a new way of studying the policies of (populist) governments by assembling and examining a novel dataset of constitutional court decisions. Recently, there has been increasing interest in populist parties from scholars of judicial politics (Voeten, Reference Voeten2020). At the same time, scholars of populism have stressed the benefits of cross‐pollination with the related literature (Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2019). This project bridges both fields and promotes an emerging research agenda on populism and judicial politics.

Acknowledgements

We thank Vera Troeger, Thomas Bräuninger, Robert A. Huber, Adam Scharpf, Verena Fetscher, the participants of the ECPR General Conference 2021 panel on ‘Judicial decision‐making under public and political scrutiny’, as well as the four anonymous reviewers for valuable feedback on previous drafts of the paper. We are grateful to the organizers of the populism seminar for the opportunity to present and discuss an earlier version of our paper, to Josef Holnburger for helpful comments on our data collection and to Lasse Ramson for insightful information on Austrian constitutional law.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure 6: Judicial independence of the VfGH according to V‐Dem data (Coppedge et al., 2022a).

Figure 7: Trust index according to a survey by OGM and APA (2022).

Figure 8: Populism score from the V‐Party data set (Lindberg et al., 2022b) based on expert assessments of anti‐elitism and people‐centrism.

Figure 9: Initiators of judicial review by type over time.

Figure 10: Initiators of judicial review by type over time.

Figure 11: Laws under review per cabinet.

Table 4: Hierarchical regressions, including all cases repealed on formal grounds.

Table 5: Regression using a dummy variable indicating populist governments as the independent variable, excluding all cases repealed on formal grounds.

Table 6: Regression using a dummy variable indicating populist governments as the independent variable, including all cases repealed on formal grounds.

Table 7: Fixed‐effects specifications, excluding cases repealed on formal grounds.

Table 8: Results based on decisions taken from 2000–2020, excluding cases repealed on formal grounds.

Data S1