Introduction

Wet brewers’ grains (WBG) are used in beef and dairy cattle diets due to their concentration of protein, fat and digestible fibre (Henry and Morrison, Reference Henry and Morrison1915; Westendorf and Wohlt, Reference Westendorf and Wohlt2002; Harmon and Phipps, Reference Harmon and Phipps2022). However, since they have low dry matter content (DM; ∼20%), storage on farms for extended periods is a challenge (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Luo, Myung and Liu2014; Ferraretto et al., Reference Ferraretto, Fernandes, Silva Filho, Sultana and Moriel2018a; Heinzen et al., Reference Heinzen, Agarussi, Diepersloot and Ferraretto2022). A potential strategy to address this issue is ensiling this co-product together with low-moisture feeds (Ferraretto et al., Reference Ferraretto, Fernandes, Silva Filho, Sultana and Moriel2018a). Maize (Zea mays L.) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor [L.] Moench) grains may be options as they have high concentration of starch (Ferraretto et al., Reference Ferraretto, Fernandes, Silva Filho, Sultana and Moriel2018a).

Although studies have shown the possibility of adequate fermentation of the WBG with maize mixture (Ferraretto et al., Reference Ferraretto, Fernandes, Silva Filho, Sultana and Moriel2018a; Ferraretto et al., Reference Ferraretto, Silva Filho, Fernandes, Kim and Sultana2018b; Heinzen et al., Reference Heinzen, Agarussi, Diepersloot and Ferraretto2022), the literature is lacking studies on the effects of using sorghum together with this co-product. Additionally, studies have been limited to the fermentation characteristics of this mixture, without showing the nutritional effects that ensiling may cause.

Ensiling rehydrated grains is a strategy for enhancing starch digestibility (Owens et al., Reference Owens, Secrist, Hill and Gill1997); however, digestibility depends on how resistant prolamins are to enzymatic digestion (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Esser, Shaver, Coblentz, Scott, Bodnar, Schmidt and Charley2011; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Pacheco, Godoi, Alhadas, Pereira, Rennó, Detmann, Paulino, Schoonmaker and Valadares Filho2020). According to Duodu et al. (Reference Duodu, Taylor, Belton and Hamaker2003), sorghum prolamins (kafirin) and maize prolamins (zein) are similar, but kafirins are considered more hydrophobic than zeins, which directly decreases starch digestibility. Another important factor to observe is the difference in protein fractions. Changes in these fractions resulting from the breakdown of proteins during the fermentation process directly affect the efficiency of protein use by ruminants, affecting both nitrogen availability for ruminal microorganisms and the supply of amino acids in the intestine (Schwab and Broderick, Reference Schwab and Broderick2017). Different protein fractions degrade at different rates in the rumen, which may alter the protein metabolism of the animals (Schwab and Broderick, Reference Schwab and Broderick2017). These changes, however, are different for maize and sorghum (Gholizadeh et al., Reference Gholizadeh, Naserian, Yari, Jonker and Yu2021).

Our hypothesis is that sorghum or maize grains, when ensiled with WBG, would provide a suitable fermentation profile with low DM losses but with differences in starch degradability and modifications in the protein profile. The aim of this study was to evaluate the starch degradability, modification of the protein profile, fermentation profile and dry matter losses (DML) of maize or sorghum ensiled with WBG.

Materials and methods

The experiment was conducted on the experimental farm of the University of Lavras, in the county of Lavras, Minas Gerais, Brazil (21°14′43″ S, 44°59′59″ W). The climate in the region is classified as humid subtropical with a dry winter (Köppen-Geiger climate classification: Cwa; Sá Jr. et al., Reference Sá, Carvalho, Silva and Alves2012).

Preparation of the silages and treatments

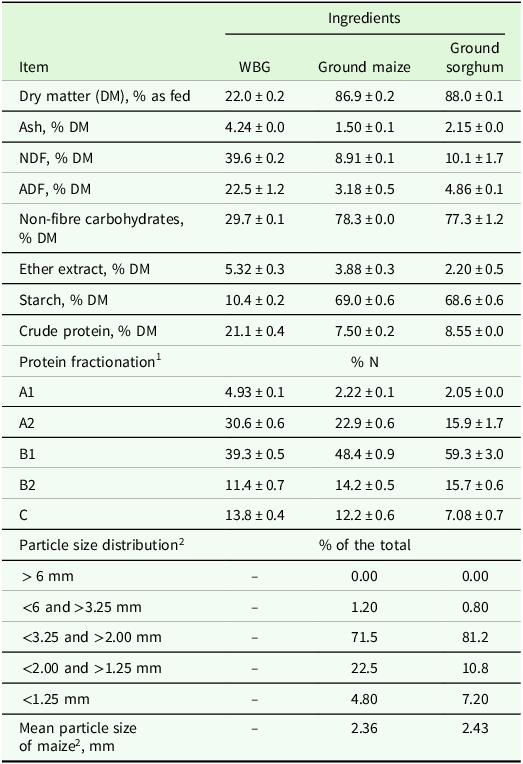

The maize and sorghum grains were purchased from a commercial farm, stored at the feed mill and then processed in a hammermill (model no. 0; Benedetti, Veranópolis, RS, Brazil) to ensure similar particle size between the two ingredients (Table 1). The mean particle size was obtained according to Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Huber, Santos, Simas and Theurer1998). After grinding, the treatments were defined using two different combinations of grains with WBG. The WBG (Table 1) was obtained from a local brewery (Cervejaria Joia Mesquita, Lavras, Brazil) straight after the brewing process.

Table 1. Chemical composition, protein fractionation of maize, sorghum and wet brewers grain (WBG) before ensiling, and particle size distribution of the grains (n = 3)

NDF, fibre insoluble in neutral detergent; ADF, fibre insoluble in acid detergent.

1 Protein fractionation according to CNCPS (Van Amburgh et al., 2015).

2 Particle size distribution based on Yu et al. (Reference Yu, Huber, Santos, Simas and Theurer1998).

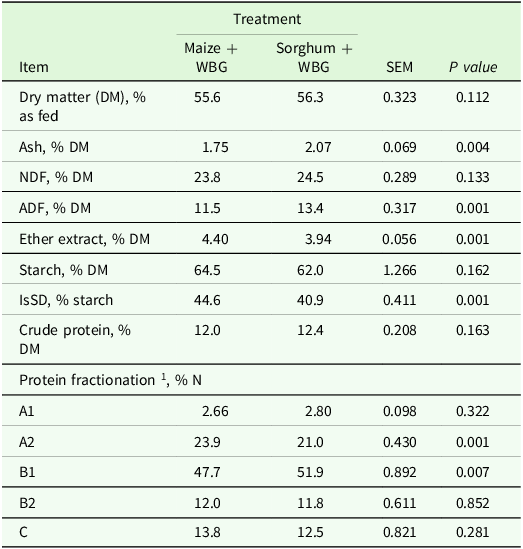

Two treatments were prepared: 1) maize + WBG: maize grain silage rehydrated with wet brewers grain; and 2) sorghum + WBG: sorghum grain silage rehydrated with wet brewers grain (Table 2). The mixture was composed of 47.7% WBG and 52.3% maize or sorghum (on a fresh matter basis) to obtain a final dry matter content of approximately 55%. The ingredients were weighed for each treatment, and the mixtures were prepared manually and individually for each silo.

Table 2. Chemical composition of maize and sorghum grains rehydrated with wet brewers grain (WBG) before ensiling

SEM, standard error of the mean; NDF, fibre insoluble in neutral detergent; ADF, fibre insoluble in acid detergent; IsSD, ruminal in situ starch degradation at 7 h.

1 Protein fractionation according to CNCPS (Van Amburgh et al., Reference Van Amburgh, Collao-Saenz, Higgs, Ross, Recktenwald, Raffrenato, Chase, Overton, Mills and Foskolos2015).

After mixing, 10 replicates of each treatment were ensiled in 1-L jars equipped with a device to vent gas. Samples were collected from each experimental unit to determine the fresh composition of the mixture. After compaction (983 ± 17 kg/m3), the silos were weighed, sealed and stored at room temperature for 90 days. Upon opening the silos, the content was weighed, homogenised and subsampled. The chemical composition, fermentation end products and microbial counts were determined in duplicate for each subsample.

Preparation of samples, analyses and calculations

The DM losses due to fermentation were calculated based on the difference between the DM weight of the material in each silo at ensiling and after the storage period (Tabacco et al., Reference Tabacco, Piano, Cavallarin, Bernardes and Borreani2009).

Aqueous extracts from the fresh and ensiled samples were prepared by homogenising 30 g of wet sample with 270 g of deionised water using a Stomacher device (Stomacher 400, Seward, London, UK) for 4 minutes. From the extract, one aliquot was used to determine pH using a pH meter (model Edge HI 11310; Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA; Bernardes et al., Reference Bernardes, Gervásio, De Morais and Casagrande2019). Another aliquot of the silage samples (2 mL) was acidified with 10 μL of 50% H2SO4 and frozen at −20 °C for subsequent analysis of fermentation products. For microbiological analyses, a third aliquot was prepared using sterile peptone water instead of deionised water and was subsequently diluted in sterile peptone physiological saline solution. To count yeasts and moulds, the surface plating technique was used with Yeast Extract Glucose Chloramphenicol (YGC) Agar culture medium (Fluka, Sigma-Aldrich Química Brasil LTDA). Serial dilutions (10−1 to 10−4) were prepared in duplicate and incubated at 28 °C for 3 and 5 days, respectively. After incubation, the colonies were counted individually, based on their macromorphological characteristics. The enumeration of LAB was performed using the surface plating technique. However, the culture medium used was De Man-Rogosa-Sharpe agar (HiMedia) and the serial dilutions were 10−2 to 10−5. The plates were incubated at 35 °C for 3 days, and then counting was performed. The number of microorganisms was counted as colony-forming units (CFU) and expressed as log10.

After thawing, the aqueous extract was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to obtain the supernatant, which was used to measure the concentrations of the fermentation end products. The organic acids and alcohols of the silage were determined using high-efficiency liquid chromatography (HPLC). The analyses were carried out on a Shimadzu HPLC system equipped with a quaternary pump (model LC-20AT), diode array detector (DAD) (model SPDM-20A), degasser (model DGU-20A5) and interface (model CBM-20A). Samples were automatically injected by an autosampler (model SIL-20A). The analytes were separated on a Supelcogel 8H (300 mm × 7.8 mm) column (cat. 59246-U) equipped with a Supelcogel 8H (10 mm × 7.8 mm) pre-column, with isocratic elution using 0.005 mol/L H2SO4 buffer solution as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min and a column temperature of 30ºC. The injection volume was 20 µL. Acids were analysed at 210 nm and alcohols with a refractive index detector. Compounds were identified by comparing retention times with known standards (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and quantified using external standardisation.

Subsamples of the fresh mixture (day 0) and of the silage (day 90) were dried in a forced-air laboratory oven at 55 °C for 72 h for pre-drying and then ground in a Wiley mill (Wiley TE-680, Philadelphia, USA) with a 1-mm sieve. After grinding, the DM was determined by drying in a laboratory oven at 105 °C (method 934.01; AOAC, 1990). Silage DM content was not corrected for the loss of volatile organic compounds. Crude protein (CP) was obtained using the Kjeldahl method and calculated as total N × 6.25 (method 984.13), and the ash concentration was determined by complete combustion in a muffle furnace at 600 °C for 5 h (method 942.05). The ether extract (EE) was quantified using the Soxhlet method (method 963.15), according to the AOAC (1990). To determine the concentration of neutral detergent fibre (NDF), the samples were treated with thermostable amylase, free of sodium sulphite (Mertens et al., Reference Mertens, Allen, Main and Thiex2002; method F-012/1, Detmann et al., Reference Detmann, Silva, Rocha, Palma and Rodrigues2021). Acid detergent fibre (ADF) was obtained using method F-014/1 (Detmann et al., Reference Detmann, Silva, Rocha, Palma and Rodrigues2021). Starch content was determined using α-amylase and amyloglucosidase enzymes and quantified by colorimetry for glucose, as described in Fernandes et al. (Reference Fernandes, da Silva, Carvalho, Schwan, Pereira, Pereira and Ávila2022), adapted from Hall et al. (Reference Hall, Arbaugh, Binkerd, Carlson, Thi Doan, Grant, Heuer, Inerowicz, Jean-Louis, Johnson, Jordan, Kondratko, Maciel, McCallum, Meyer, Odijk, Parganlija-Ramic, Potts, Ruiz, Snodgrass, Taysom, Trupia, Steinlicht and Welch2015).

Starch degradation

For evaluation of in situ starch degradability, samples of the silage and of the material before ensiling (fresh mixture, day 0) were dried in a forced-air laboratory oven at 55 °C for 72 h and then ground in a Wiley mill (Wiley TE-680, Philadelphia, USA) with a 2-mm sieve. Bags (10 × 20 cm, with microporosity of 50 ± 10 μm) containing 5 ± 0.30 g of DM were used, following the methodology described by Gusmão et al. (Reference Gusmão, Lima, Ferraretto, Casagrande and Bernardes2021). Three rumen-cannulated cows of the Tabapuã breed were used. Their diet consisted of a total mixed feed ration composed of 56.5% maize silage, 11% grain maize, 28.7% dried distiller’s grain with solubles, 0.8% urea and 3.0% minerals (DM basis). The cows underwent a 15-day feed adaptation period. The bags with the samples were placed inside 2 mesh bags (30 × 40 cm) and incubated in the rumen for 7 h. Blank bags (without samples) were also included in the mesh bags and incubated to correct for possible DM infiltrations in the sample bags. Immediately after incubation, the bags were immersed in cold water to halt fermentation. They were then rinsed in a washing machine set to rinse and spin cycles with water at room temperature. Five wash and spin cycles were used to ensure cleaning of the bags. Two control bags (0-h incubation) were washed together with the incubated bags to correct for particle losses. After the washing process, the bags were dried in a forced-air laboratory oven at 55 °C for 48 h, ground using a mortar and pestle to pass through a 1 mm sieve and analysed for starch, as previously described.

Protein fractionation

The ammonia concentration was estimated based on method N-006/1 (Detmann et al., Reference Detmann, Silva, Rocha, Palma and Rodrigues2021). The soluble protein, neutral detergent insoluble nitrogen (NDIN) and acid detergent insoluble nitrogen (ADIN) concentration were determined according to the methods described by Licitra et al. (Reference Licitra, Hernandez and Van Soest1996). Based on these analyses, N fractionation was carried out using CNCPS version 6.5, considering the A1 (ammonia), A2 (soluble true protein), B1 (insoluble true protein), B2 (fibre-bound protein) and C (indigestible protein) fractions (Van Amburgh et al., Reference Van Amburgh, Collao-Saenz, Higgs, Ross, Recktenwald, Raffrenato, Chase, Overton, Mills and Foskolos2015).

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using a completely randomised design, with treatment as the sole fixed effect, employing the MIXED procedure of SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The statistical model was defined as:

where Y ij is the observation of the response variable for treatment i in replicate j, μ is the overall mean, T i is the fixed effect of treatment, and ε ij is the random error term assumed to be normally distributed with mean zero and variance σ 2 .

Least squares means (LSMEANS) were estimated for treatment comparisons using the pdiff option, and Tukey’s honestly significant difference adjustment was applied to control for multiple comparisons. Model residuals were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was verified by visual inspection of residual plots. All residuals exhibited normal distribution for all variables. Statistical significance was declared at P < 0.05.

Results

Chemical composition, starch degradability and protein fractionation

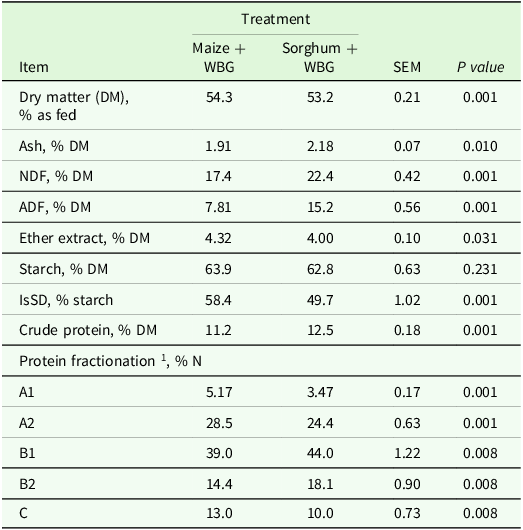

The DM content was affected by the treatments (P = 0.002); the maize + WBG had a higher DM value (54.3%) compared to the sorghum + WBG (53.2%; Table 3). The ash content was higher for sorghum + WBG (P = 0.010). Additionally, CP content differed significantly (P < 0.001), being 12% higher in the sorghum + WBG treatment. The EE content was higher in maize + WBG (4.32%) compared to sorghum + WBG (4.00%) (P = 0.031). Regarding NDF and ADF, both parameters had differences: NDF values were 17.4% and 22.4% (P < 0.001) while ADF values were 7.8% and 15.2% (P < 0.001) for maize + WBG and for sorghum + WBG, respectively. No difference between the treatments was observed for starch content, with 63.9% in maize + WBG and 62.8% in sorghum + WBG (P = 0.231). However, starch degradation was higher for maize + WBG (58.4%) than for sorghum + WBG (49.7%) (P < 0.001).

Table 3. Chemical composition and degradability of starch from maize and sorghum silages rehydrated with wet brewers grain (WBG)

SEM, standard error of the mean; NDF, fibre insoluble in neutral detergent; ADF, fibre insoluble in acid detergent; IsSD = ruminal in situ starch degradation at 7 h.

1 Protein fractionation according to CNCPS (Van Amburgh et al., Reference Van Amburgh, Collao-Saenz, Higgs, Ross, Recktenwald, Raffrenato, Chase, Overton, Mills and Foskolos2015).

Regarding protein fractionation of the silages, data show that the treatments affected all the fractions. The A1 fraction had values of 5.17% for maize + WBG and 3.47% for sorghum + WBG (P < 0.001). The A2 fraction, in turn, had values of 28.5% for maize + WBG and 24.4% for sorghum + WBG (P < 0.001). In the B1 fraction (P = 0.008), there were values of 39.0% for maize + WBG and 44.0% for sorghum + WBG. The B2 fraction exhibited 14.4% for maize + WBG and 18.1% for sorghum + WBG (P = 0.008), while the C fraction had 13.0% for maize + WBG and 10.0% for sorghum + WBG (P = 0.008).

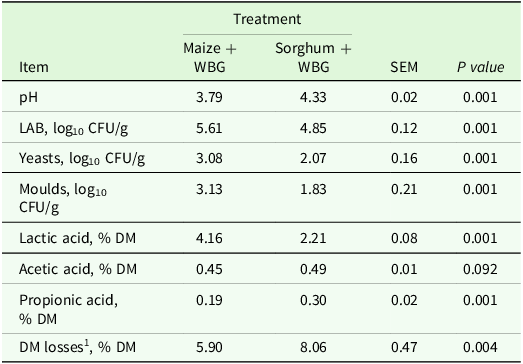

pH, DML, fermentation products and microbial count

The pH value of the silages was different between the treatments (P < 0.001), with values of 3.79 for maize + WBG and 4.33 for sorghum + WBG (Table 4). Similarly, DML differed significantly (P = 0.004), with the maize + WBG treatment showing 37% lower losses compared to sorghum + WBG. The results indicated that treatments altered LAB populations, with values of 5.61 log10 for maize + WBG and 4.85 log10 for sorghum + WBG (P < 0.001). Yeast counts also had differences, with 3.08 log10 for maize + WBG and 2.07 log10 for sorghum + WBG (P < 0.001). In addition, the mould count was higher in the maize + WBG treatment (3.13) compared to sorghum + WBG (1.83 log10) (P < 0.001). For lactic acid content, the results were 4.16% DM for maize + WBG and 2.21% DM for sorghum + WBG (P < 0.001). The acetic acid concentration did not show a difference between the treatments, with 0.45% DM for maize + WBG and 0.49% DM for sorghum + WBG (P = 0.092). However, propionic acid had a difference, with 0.19% DM for maize + WBG and 0.30% DM for sorghum + WBG (P < 0.001). The 1,2-propanediol, ethanol and butyric acid concentrations were not detected in silage samples.

Table 4. Microbial count and fermentation end products of maize and sorghum silages rehydrated with wet brewers grain (WBG)

SEM, standard error of the mean; LAB, lactic acid bacteria; CFU, colony forming units; DM, dry matter.

1 Dry matter losses during the storage period. 1,2-propanediol, ethanol and butyric acid were not detected.

Discussion

Chemical composition, starch degradability and protein fractionation

The type of grain can significantly affect the silage fermentation profile (Agarussi et al., Reference Agarussi, Pereira, Pimentel, Azevedo, da Silva and Silva2022). Chemical and structural factors of the grain affect the availability of substrates for fermentation, which, in turn, can considerably modify the nutritional composition of the silage produced (Rooney and Pflugfelder, Reference Rooney and Pflugfelder1986; McAllister et al., Reference McAllister, Phillippe, Rode and Cheng1993; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Bueno, Jacovaci, Donadel, Ferraretto, Nussio, Jobim and Daniel2020). In this respect, the DM content of the maize + WBG treatment was higher (54.3%) than that of the sorghum + WBG treatment (53.2%). The fermentation rate may alter DM losses, which depend on the dominant microbial species and on the fermentation substrate (Pahlow et al., Reference Pahlow, Muck, Driehuis, Elferink, Spoelstra, Buxton, Muck and Harrison2003; Borreani et al., Reference Borreani, Tabacco, Schmidt, Holmes and Muck2018). The lower DM in sorghum + WBG silages may result from higher production of propionic acid, which is associated with higher DM losses. During propionate production, lactate is oxidised to pyruvate, which undergoes decarboxylation, generating a CO2 molecule (Rooke and Hatfield, Reference Rooke, Hatfield, Buxton, Muck and Harrison2003). The carbon present in the CO2 molecule comes from compounds in the ensiled material, which were previously part of the DM fraction. For that reason, the release of this gas directly contributes to reduction in total DM (Rooke and Hatfield, Reference Rooke, Hatfield, Buxton, Muck and Harrison2003; Borreani et al., Reference Borreani, Tabacco, Schmidt, Holmes and Muck2018).

Insoluble compounds, such as ash, generally do not undergo significant changes in silage. However, their concentration may increase due to the consumption of some soluble components by microorganisms (Meschy et al., Reference Meschy, Baumont, Dulphy and Nozières2005; Baumont et al., Reference Baumont, Arrigo and Niderkorn2011), which can lead to a higher ash content in the silage dry matter. In our study, sorghum + WBG silages exhibited higher ash content, which may reflect greater utilisation of soluble compounds during fermentation.

The sorghum + WBG treatment had a higher CP concentration. This difference can be attributed to the chemical composition of the sorghum grain, which, in our study, was associated with higher CP content than the maize grain. However, it should be considered that nitrogen loss may occur during fermentation (Bueno et al., Reference Bueno, Lazzari, Jobim and Daniel2020), even though in smaller quantity compared to other soluble fractions and with smaller effects on the total CP content (Rooke and Hatfield, Reference Rooke, Hatfield, Buxton, Muck and Harrison2003). Moreover, CP values could be slightly higher than those in the material that gave rise to the silage, due to the consumption of other nutrients, such as soluble carbohydrates (Bueno et al., Reference Bueno, Lazzari, Jobim and Daniel2020).

The maize + WBG had a higher EE content compared to sorghum + WBG. Maize grain has a higher lipid content compared to sorghum grain (NASEM, 2021). Therefore, these differences in EE content are linked to natural differences in the oil concentration of each grain.

The NDF values in our study decreased after 90 days of fermentation. Different studies with different crops have shown reduction in fibre components after ensiling (Yahaya et al., Reference Yahaya, Kawai, Takahashi and Matsuoka2002; Desta et al., Reference Desta, Yuan, Li and Shao2016; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Dong, Li, Chen, Bai, Jia and Shao2018; Roseira et al., Reference Roseira, Pereira, da Silveira, da Silva, Alves, Agarussi and Ribeiro2023). A possible explanation for this reduction would be the solubilisation of the cell wall components due to the acidic conditions in the silage, as well as by microbial activity (Morrison, Reference Morrison1979).

The larger amounts of NDF and ADF in the sorghum + WBG treatment compared to the maize + WBG treatment can be attributed to the structural composition of the sorghum grain. Sorghum generally has a higher proportion of fibre components, including a more resistant and fibre-rich pericarp (Duodu et al., Reference Duodu, Taylor, Belton and Hamaker2003), which may explain the higher NDF and ADF values.

For ensiled feeds, special importance should be given to protein fractionation, as ensiling directs nutrients toward fermentation, which ends up modifying the feed value of the silage by changing nutrient composition and availability (Bueno et al., Reference Bueno, Lazzari, Jobim and Daniel2020). In this study, the protein fractionation was modified after ensiling in all the treatments. In addition, the treatments presented different protein fractionation profiles.

According to Arcari et al. (Reference Arcari, Martins, Tomazi, Gonçalves and Santos2016), Castro et al. (Reference Castro, Pereira, Dias, Lage, Barbosa, Melo, Ferreira, Carvalho, Cardoso and Pereira2019) and Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Pacheco, Godoi, Alhadas, Pereira, Rennó, Detmann, Paulino, Schoonmaker and Valadares Filho2020), ensiling is responsible for increasing the A fraction of silages. Similarly, our data show that the A1 (ammonia) and A2 (soluble protein) fractions of both treatments increased numerically compared to the mixture before ensiling. The maize + WBG treatment had higher values for these fractions. Several studies (Saylor et al., Reference Saylor, Casale, Sultana and Ferraretto2020; Saylor et al., Reference Saylor, Diepersloot, Heinzen, McCary and Ferraretto2021) have demonstrated that higher proportions of soluble protein fractions are linked to enhanced starch digestibility in maize-based silages (including whole-plant maize silage and high-moisture corn). Consequently, the greater A1 and A2 fractions observed in the maize + WBG treatment may account for its higher starch degradability (Ferraretto et al., Reference Ferraretto, Silva Filho, Fernandes, Kim and Sultana2018b) compared with sorghum + WBG. The less pronounced increase for the treatment containing sorghum may be related to the structure of the protein matrix that coats the grain (Rooney and Pflugfelder, Reference Rooney and Pflugfelder1986). Most of the protein in the sorghum grain consists of kafirin (Duodu et al., Reference Duodu, Taylor, Belton and Hamaker2003), a storage protein of the prolamin group (Johns and Brewster, Reference Johns and Brewster1916). This protein has low solubility and is less degradable due to its intrinsic properties (Rooney and Pflugfelder, Reference Rooney and Pflugfelder1986; Duodu et al., Reference Duodu, Taylor, Belton and Hamaker2003; Belton et al., Reference Belton, Delgadillo, Halford and Shewry2006; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Pacheco, Godoi, Alhadas, Pereira, Rennó, Detmann, Paulino, Schoonmaker and Valadares Filho2020). Compared to maize protein (zein), kafirin is more hydrophobic and less digestible (Herrera-Saldana et al., Reference Herrera-Saldana, Huber and Poore1990; Belton et al., Reference Belton, Delgadillo, Halford and Shewry2006).

The increase in soluble protein in grain silages is directly correlated with the extent of proteolysis and the resulting increase in starch digestibility (Ferraretto et al., Reference Ferraretto, Silva Filho, Fernandes, Kim and Sultana2018b). The protein matrix undergoes solubilisation during fermentation, which increases the surface area available for ruminal microorganism activity (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Esser, Shaver, Coblentz, Scott, Bodnar, Schmidt and Charley2011). However, the different prolamins that coat the maize and sorghum grains act as physical barriers to degradation (Hoffman et al., Reference Hoffman, Esser, Shaver, Coblentz, Scott, Bodnar, Schmidt and Charley2011). Sorghum generally has lower starch digestibility compared to maize. The resistance of the hard layer of the peripheral endosperm to digestive activity is primarily responsible for this effect (Rooney and Pflugfelder, Reference Rooney and Pflugfelder1986). This may explain the increase in starch digestibility in our study for silages of the maize + WBG treatment, even though the starch values were similar in the treatments. Other studies also indicate that the starch-protein matrix in sorghum grain may be more resistant to degradation compared to maize grain (Duodu et al., Reference Duodu, Taylor, Belton and Hamaker2003; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Pacheco, Godoi, Alhadas, Pereira, Rennó, Detmann, Paulino, Schoonmaker and Valadares Filho2020).

In the B1 and B2 fractions, higher values were obtained in the sorghum + WBG treatment, suggesting a larger amount of available and potentially more degradable protein associated with sorghum fibre. It is noteworthy that sorghum has high fibre content, with insoluble (75%–90%) and soluble (10%–25%) fibres present in the cell walls of the pericarp and endosperm (Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Zhang, Warner and Fang2019; Mohamed et al., Reference Mohamed, Fawzi, Basit, Kaleemullah and Sofy2022). This increase in the B1 and B2 fractions in the treatment using sorghum grain can therefore be explained by the structural arrangement of the cell wall of this grain, which has higher NDF content compared to maize grain (NASEM, 2021).

The C fraction had higher values for the maize + WBG treatment, even though higher values of ADF were found in sorghum as an ingredient and in the sorghum + WBG mixture before and after ensiling. However, it is important to highlight that silage fermentation is a complex process and that it can be affected not only by the ingredients but also by their interactions during fermentation. The C fraction contains proteins associated with lignin and Maillard reaction products that are not degradable in the rumen (Krishnamoorthy et al., Reference Krishnamoorthy, Muscato, Sniffen and Van Soest1982). Maize has a larger amount of soluble reducing sugars, such as glucose (Rooke and Hatfield, Reference Rooke, Hatfield, Buxton, Muck and Harrison2003; NASEM, 2021). This can facilitate the reaction during fermentation, beginning with condensation between a carbonyl group of a reducing sugar and an amine compound (Martins et al., Reference Martins, Jongen and Van Boekel2000). In addition, it is important to emphasise that when grains are ensiled, conditions such as pH and temperature can accelerate this type of reaction (Van Boekel, Reference Van Boekel2001). This may have been the situation in the maize + WBG silage, especially because of its higher concentration of soluble sugars and partially degraded proteins (A1 and A2 fractions). In contrast, since sorghum grain has a higher proportion of slow-degrading proteins (B1 and B2), a smaller amount of substrate may have been available for this type of reaction.

The results of this study highlight the importance of evaluating not only the fermentation quality and DM losses of silage, but also the nutritional modifications that ensiling enables, especially when using byproducts such as wet brewers grain. This information allows diets to be adjusted to optimise the efficiency of nitrogen use by animals, reducing losses and environmental impacts. In addition, by evaluating the dynamics of using different ingredients and combinations in ensiling, it is possible to select strategies that enhance preservation of true protein and the supply of protein fractions that meet both the needs of ruminal microorganisms and the metabolic requirements of the animals. Thus, knowledge of protein fractionation in the silages produced not only enhances understanding of protein dynamics in silage but also contributes to the formulation of more efficient and sustainable diets.

pH, DML, fermentation end products and microbial count

The pH value is directly affected by the concentration of organic acids produced by microorganisms in silage, and lactic acid is most effective in lowering pH during the fermentation process (Kung et al., Reference Kung, Shaver, Grant and Schmidt2018). The lower pH value of the maize + WBG treatment compared to the sorghum + WBG treatment is likely due to higher proteolysis in the silo, which can be inferred from the higher proportion of soluble protein. This, in turn, can lead to higher release of peptides and free amino acids, which favour the growth of lactic acid-producing bacteria (Pahlow et al., Reference Pahlow, Muck, Driehuis, Elferink, Spoelstra, Buxton, Muck and Harrison2003; Young et al., Reference Young, Lim, Der Bedrosian and Kung2012; Ferraretto et al., Reference Ferraretto, Fredin and Shaver2015).

Similarly, in this study, larger populations of LAB and lactic acid were found in the maize + WBG treatment. Larger populations of LAB are also responsible for reducing the effects of undesirable microorganisms, which may explain the lower DM losses found in the maize + WBG treatment (Borreani et al., Reference Borreani, Tabacco, Schmidt, Holmes and Muck2018). The DM losses during ensiling are directly related to fermentation efficiency and microbial activity (Borreani et al., Reference Borreani, Tabacco, Schmidt, Holmes and Muck2018; Wróbel et al., Reference Wróbel, Nowak, Fabiszewska, Paszkiewicz-Jasińska and Przystupa2023). Another important aspect that can directly alter losses during the fermentation process is the type of ingredient used in the treatments. Given the grain structure of maize, it is usually more digestible than sorghum (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Pacheco, Godoi, Alhadas, Pereira, Rennó, Detmann, Paulino, Schoonmaker and Valadares Filho2020) and tends to have a more efficient fermentation response. This factor is particularly relevant in silages, where the combination of high DM and high pH can compromise silage stabilisation.

The acetic acid values were similar for the two treatments and can be considered adequate based on the concentrations recommended for this acid in high-moisture grain silages (Kung et al., Reference Kung, Shaver, Grant and Schmidt2018).

Propionic acid was higher in the sorghum + wet brewery grain (WBG) treatment. Despite the common association between propionic acid and clostridial fermentations (Kung et al., Reference Kung, Shaver, Grant and Schmidt2018), the absence of butyric acid suggests that its origin in this experiment is not related to Clostridium activity, possibly involving alternative metabolic pathways. Additionally, the higher concentration of propionic acid may be beneficial for the preservation and stabilisation of silages, since it has an antifungal effect (Woolford, Reference Woolford1975; Kung et al., Reference Kung, Robinson, Ranjit, Chen, Golt and Pesek2000; Kung et al., Reference Kung, Stokes, Maine, Lin, Buxton, Muck and Harrison2003). Besides organic acid concentration, other variables that may indicate higher stability of these silages are the counts of yeasts and filamentous fungi. Fungi, particularly yeasts, generally play important roles in the aerobic deterioration of silage (Muck et al., Reference Muck, Nadeau, McAllister, Contreras-Govea, Santos and Kung2018). In this study, the counts of these microorganisms differed between treatments and were lower in the sorghum + WBG treatment, which may support the hypothesis of higher stability for this treatment.

Conclusions

Wet brewers’ grains ensiled with maize showed lower fermentation losses, higher A1 and A2 protein fractions (i.e., greater ammonia nitrogen and soluble true protein content, respectively) and higher starch degradability compared with sorghum silages rehydrated with wet brewers’ grains.

Author contributions

Natália Nunes de Melo (Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing), Thiago Fernandes Bernardes (Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing), Matheus Wilson Silva Cordeiro (Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft).

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All animals used in this study were cared for according to acceptable practices and experimental protocols that were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of the University of Lavras (039/23).