Introduction

Raising societal support for international cooperation is an important goal for most development organizations.Footnote 1 While the Dutch government has made the political decision to devote 0.8% of its gross national product (GNP) to international cooperation, this needs to be supported by a broad constituency. Many civil society organizations that depend on public co-funding are therefore also involved in consciousness-raising activities. Otherwise, they also try to gain support in order to maintain revenues from private fundraising.

Societal support for international cooperation programs is usually considered to be the result of a complex process of information provision that eventually may result in favorable opinions and/or concrete action. Development organizations increasingly rely on public campaigns and direct-mailing to create a solid constituency for their fundraising operations and political mobilization activities. Some more specialized agencies have developed exchange programs in which Western citizens—mostly young people—directly experience day-to-day life and developmental activities in the South. The latter programs are based on the principles of peer-group exchange and subsequent diffusion of knowledge and experiences among a wider audience.

Until now, little is known about the effectiveness of such exchange programs for raising societal support to development cooperation. Within the framework of OECD and the EU EuroBarometer, some regular monitoring is done to verify general public opinions on issues like state budget support to development assistance and changes in the public opinion on global and international affairs (OECD 2003). In addition, the European Social Science Survey provides periodically information regarding main drivers for citizenship involvement and political engagement. Far more difficult to assess are the underlying processes that could lead to adjustments in the societal support base. Most attention is usually given to information provision and knowledge diffusion that could contribute to changing attitudes and/or further engagement with the goals and activities pursued by international development agencies (Helmich and Smillie Reference Helmich and Smillie1998).

This article provides a first effort to assess the role of one particular mode of raising support to international cooperation among secondary school students in The Netherlands. The Edukans foundation has a long trajectory in involving Dutch secondary schools in societal support and fundraising campaigns for educational programs in developing countries. Using a wide range of information and training tools, every year on average about 52,000 students from different types of secondary schools are encouraged to take part in awareness raising and fundraising activities. The “Going Global” program which is the object of this study is directed at secondary schools, enabling a selective group of students to join an exchange visit to a Southern country, while receiving active support from their schoolmates. After their return they have to deliver several presentations on their experiences. It is expected that a more direct involvement with the living, working, and schooling conditions of contemporaries in a developing country will enable Dutch students to better understand the critical conditions for enhancing sustainable development and to develop favorable attitudes toward world citizenship. Moreover, the presentations of the exchange students to their fellow classmates may leave a stronger impression on their peers than the information provided by teachers or development organizations.

This article reviews the influence of the Going Global program on selected attitudinal and behavioral variables of secondary school children in the age range 16–19 years. We make two comparisons with help of propensity score matching: (1) a comparison between direct participants in international exchange trips and their classmates; (2) a comparison between indirectly exposed students, i.e., the classmates (peers) of the direct participants, and non-exposed students from non-participating schools. The classmates are exposed to Going Global in the school-wide campaigns and the exchange visit preparation, and receive presentations by the exchange students upon their return. The reference group of non-participants is selected from secondary schools with similar structural characteristics (i.e., rural/urban location, school types) that are used as a proxy for the baseline situation (in the absence of a pre-participation survey). We seek to identify the effect of participation in or exposure to the Going Global program on the supportive attitudes toward international development cooperation. By estimating Rosenbaum bounds we show that the results are robust to unobservable differences between the groups.

The remainder of the article is then structured as follows: first, we give a description of the Going Global exchange program; this is followed by a discussion of different views regarding the determinants of societal support to international cooperation; thereafter, we outline the survey design, the sampling strategy, and the matching procedures used for the assessment of the program. Results are processed with propensity score matching to control for the variation in intrinsic characteristics between the three groups of students.

We find significant positive effects on knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral variables—weighted for variation in group composition—indicating that the results can be largely attributed to the role of the Going Global program. For the exchange student strong positive effects are identified on all four dimensions of knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and tolerance. For the classmates positive effects can still be found on the dimensions of knowledge and attitudes, but no effect is registered on behavior and tolerance.

Going Global Program

The Going Global program of the Dutch development NGO Edukans was established in 1999 and started as an exchange of students between secondary schools in The Netherlands and India. During the following 10 years, a total of 160 Dutch secondary schools participated and 290 Dutch student representatives visited fellow students in several developing countries (i.e., India, Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Peru). Through information and diffusion activities, an estimated number of 52,000 Dutch college students are yearly in contact with the Edukans Going Global program.

The Going Global program is part of the societal support activities of Edukans and its overall objective is to actively engage young people in secondary school in the age category of 12–18 years with international cooperation. This youth is concretely informed about and practically involved with education settings in the South. It is expected that these young people will also widen support among their fellows, friends, and family in The Netherlands. In addition, the program also aims to enhance tolerance toward the multicultural nature of Dutch society. Respect for other cultures and exchange with marginalized groups within the society is considered a fundamental value of sustainable society building.

The exchange program is based on a philosophy of directly linking peer groups in secondary education. A key aspect is the concrete engagement of Dutch school students with people living in poverty situations prevailing in developing countries (and partly also in their own society). The participating secondary schools in The Netherlands are invited to propose a student representative as a candidate to participate in a 10 days visit to one of the countries where school programs supported by Edukans in the South take place. These representatives receive intensive training and are in charge of writing short Internet accounts and delivering several presentations on their experience upon their return to The Netherlands. During their preparations, the student delegates are supported by professional consultants, and during the trip they are accompanied by a filmmaker in charge of delivering an audiovisual report. The school is committed to raise funds (an amount around €13,000) by organizing several fund raising events (dance party, sponsor walk, etc.). The money raised is donated to Edukans for financial support to its development programs in the South.

The program has shown a favorable response among Dutch schools, gradually increasing the number of participating schools and also involving more schools from lower educational categories. Edukans developed different educational materials to be used in the schools. Audiovisual means are frequently used to enhance communication, and web-based information materials are made available to strengthen outreach. In addition, in partnership with other development organizations, educational events like theater performances have been organized.

Knowledge and awareness-raising objectives prevail within the Edukans Going Global program. Fundraising is another objective of the program, given that participating schools have to raise a specific amount of money. The direct financial returns of the Edukans exchange program have been gradually rising from €492,000 in 2003 to €560,000 in 2007. These returns are doubled through subsidies by other related development organizations (notably NCDO, Dutch National Committee for International Cooperation and Sustainable Development) within the framework of the Dutch fundraising incentive system. The money raised is earmarked for education projects implemented by Edukans in the country visited by the students. Edukans considers awareness-raising and fundraising as two sides of the same coin; people are enabled to act when they are touched by awareness-raising events, and while involved in fundraising activities young people become more engaged with international development issues.

The methodological foundations of the Edukans Going Global program are strongly based on linking Dutch secondary school students with their peers in developing countries. Combining information and knowledge exchange with a clear action perspective is thought to enhance the sensitivity to development issues among the school population. This “learning by doing” approach is preferred in order to guarantee a long-term emotional attachment that may eventually be translated into other supportive actions. More importantly, Edukans expects that the stories and experiences of the selected exchange students lead to rapid diffusion to and leave a deep impression with the classmates. This could lead to important externalities that make the program highly cost-efficient.

Assessing Societal Support to International Cooperation

Many Dutch development organizations consider activities for raising societal support to international cooperation as part of their core mission. It has become increasingly important to establish independent local fund-raising to maintain access to public co-funding for their overseas operations. Moreover, diffusion of information and direct engagement with development programs are critical for the consolidation of a stable societal support base for international cooperation activities.

Theoretical and empirical studies regarding processes and underlying determinants for societal support to international cooperation are scarcely available. The Dutch National Committee for International Cooperation and Sustainable Development (Bergmans Reference Bergmans2007) describes the public support base in terms of “engagement with” and “support to” the goals of international development cooperation. Box et al. (Reference Box, Engelhard and Kruiter1999) also include favorable opinion toward development cooperation as part of the societal support base. In practice, this is frequently equated with support for the earmarking of a fixed share of the public budget for development cooperation activities.

Three layers of societal support to development issues have been identified by Develtere (Reference Develtere2003): (a) primary support of people (mainly politicians and political parties) directly involved in decision-making regarding budgets for development cooperation; (b) secondary support base of actors engaged in political pressure and/or awareness-raising concerning international cooperation (like churches, pressure groups, media, and NGOs); and, (c) tertiary support base consisting of the broad public opinion that should guarantee a societal consensus regarding the actions of the two former groups. This gives room for a conceptual distinction between political support and societal support, whereby the latter provides a base for subsequent decisions in formal policy circles at local and national level (Box et al. Reference Box, Engelhard and Kruiter1999).

The constituting elements of societal support for international cooperation can be conceptualized in terms of different levels or degrees of engagement. A useful framework provided by Finger (Reference Finger1994) distinguishes between awareness, attitudes (conviction), and action. The provision of information enables people to create awareness about developmental issues that could eventually be translated into changing attitudes or concrete actions. Psychological and sociological factors like norms and values, family life, and social networks are likely to influence individual engagement (Fishbein and Ajzen Reference Fishbein and Ajzen1975). Given the specific position of youth, with simultaneous links to the family environment, the school setting, and friendship relationships with classmates, they are subject to multiple influences while making-up their minds about international affairs and poverty issues.

In a similar vein, Develtere (Reference Develtere2003) outlines four different dimensions of societal support toward international cooperation: knowledge, attitude, opinion, and action. The mutual relations between these dimensions are usually difficult to disentangle. Burgess et al. (Reference Burgess, Bedford, Hobson, Davies, Harrison, Berkhout, Leach and Scoones2003) outlines that attitudes change under the influence of access to information, but this hypothesis is refuted by Brantjes (Reference Brantjes and van der Velden2007) stating that not all people who are convinced that something should be done against poverty are also willing to take actions themselves. Other factors, like emotional attachment to the issue and feelings of connectedness to peer groups are supposed to be equally important to engage people into concrete behavior and action. Moreover, active experiences with target groups may strongly influence opinions and attitudes. This is confirmed in research regarding attitudes concerning migrants and asylum seekers, where direct exchange experiences lead to (positive) attitudinal change (Calne Reference Calne2000; Develtere Reference Develtere2003). The links and dynamics between knowledge, attitude, and behavior are hence not of a linear nature and the ways they influence or reinforce each other are yet to be determined.Footnote 2

Based on the preceding discussion regarding the constituent elements of societal support for development cooperation, we developed an analytical model for assessing the effects of the Edukans Going Global program at secondary schools in The Netherlands. Awareness (knowledge), engagement (attitude), and action (behavior) are considered as the prime elements of the youth’s support base, whereby each element may reinforce other components and vice versa. Providing information and enabling emotional engagement are likely to reinforce solidarity attitudes among young people. This complex interaction between “head, heart, and hands” could eventually lead to active engagement or commitment with development cooperation. In addition to international development issues, attention is given to the tolerance attitudes regarding ethnic and religious minorities (mainly former immigrants and refugees) within the current multi-cultural Dutch society, considered as an important expression of global citizenship.

Differences in support for international development among students that participated directly or indirectly in the Going Global program (compared to a reference group) are supposed to be influenced by a wide range of factors. For an unbiased assessment of the program, due attention should be given to intrinsic factors that could influence the participation and/or the results. The analytical model therefore needs to control for differences in education, religious, and family background, social networks,Footnote 3 and earlier involvement in international issues through club membership. These individual characteristics may lead to selection bias and thus should be separated from the effects of exposure to the Going Global program.

Data and Methods

Data collection regarding the effectiveness of the Edukans Global exchange program was conducted through a standardized electronic survey among three different groups of secondary school students (Data collection was conducted in the period August till October 2007). Distinction is made between: (1) students who directly participated in international exchange visits (valid N = 186); (2) exposed schoolmates that became acquainted with the exchange program through their fellow students (valid N = 608); and, (3) other students that never were in touch with the exchange program (valid N = 276). The last group is considered as a reference group of students with otherwise similar characteristics. For each category, data were collected for students that participate in one of the three different levels of secondary education in The Netherlands: lower level (VMBO, providing access to vocational education), medium level (HAVO, providing access to professional education), and higher level (VWO, providing access to university education).

The survey included a series of general questions regarding individual and family characteristics (age, gender, religious background, political preference, and social network). This was followed by several statements related to their knowledge, attitudes, and behavior with respect to international cooperation and tolerance toward the multicultural society. For the direct and indirect participants, specific questions were incorporated to capture their knowledge gained from and/or experiences in the Going Global exchange program, followed by retrospective questions on how this particular experience has influenced their opinions regarding international development cooperation.

The respondents were approached by letter and invited to reply through an Internet survey. Among the exchange students, the overall response rate was 65% for the nine groups that traveled abroad.Footnote 4 Classmates were selected from the Edukans database, making a regional stratification of secondary schools. From this sample, we selected 126 schools that provided a representative sample frame. We classified these schools according to characteristics of the school type and the participation rate in the Going Global exchange program (i.e., number of years and degree of intensity). The final sample selection identified 46 schools to participate in the survey that could be contacted about the data of (former) classmates. This resulted in a total number of 6,010 (former) classmates who were approached by letter. The final response rate of the Internet survey resulted in 608 valid replies, representing a reliable 10% response rate. For the reference group, we selected three secondary schools in different locations and with varied school types where the students never participated in any school program directed at development cooperation. The reference group consists of 276 students from secondary schools with similar structural characteristics (rural/urban location, school types, and performance scores) that are used as a proxy for the baseline situation (in the absence of a pre-participation survey). These students were directly visited in their classroom and are usually slightly younger than the other two groups (but of similar age when the former groups became participant of the Edukans exchange program).

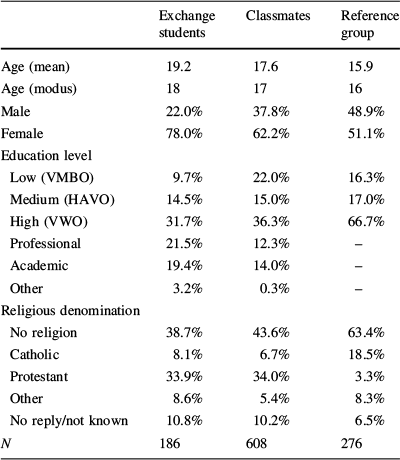

Descriptive statistics from the sample are provided in Table 1. We notice a larger female participation among the exchange students and their classmates. Moreover, in the reference group the proportion of students in higher-level secondary school education is larger, compensating for the fact that some former students from the medium and high level secondary school types are now following professional or academic training. In addition, the reference group appears to be less religiously affiliated. We control for these differences in the subsequent matching process.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics

|

Exchange students |

Classmates |

Reference group |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (mean) |

19.2 |

17.6 |

15.9 |

|

Age (modus) |

18 |

17 |

16 |

|

Male |

22.0% |

37.8% |

48.9% |

|

Female |

78.0% |

62.2% |

51.1% |

|

Education level |

|||

|

Low (VMBO) |

9.7% |

22.0% |

16.3% |

|

Medium (HAVO) |

14.5% |

15.0% |

17.0% |

|

High (VWO) |

31.7% |

36.3% |

66.7% |

|

Professional |

21.5% |

12.3% |

– |

|

Academic |

19.4% |

14.0% |

– |

|

Other |

3.2% |

0.3% |

– |

|

Religious denomination |

|||

|

No religion |

38.7% |

43.6% |

63.4% |

|

Catholic |

8.1% |

6.7% |

18.5% |

|

Protestant |

33.9% |

34.0% |

3.3% |

|

Other |

8.6% |

5.4% |

8.3% |

|

No reply/not known |

10.8% |

10.2% |

6.5% |

|

N |

186 |

608 |

276 |

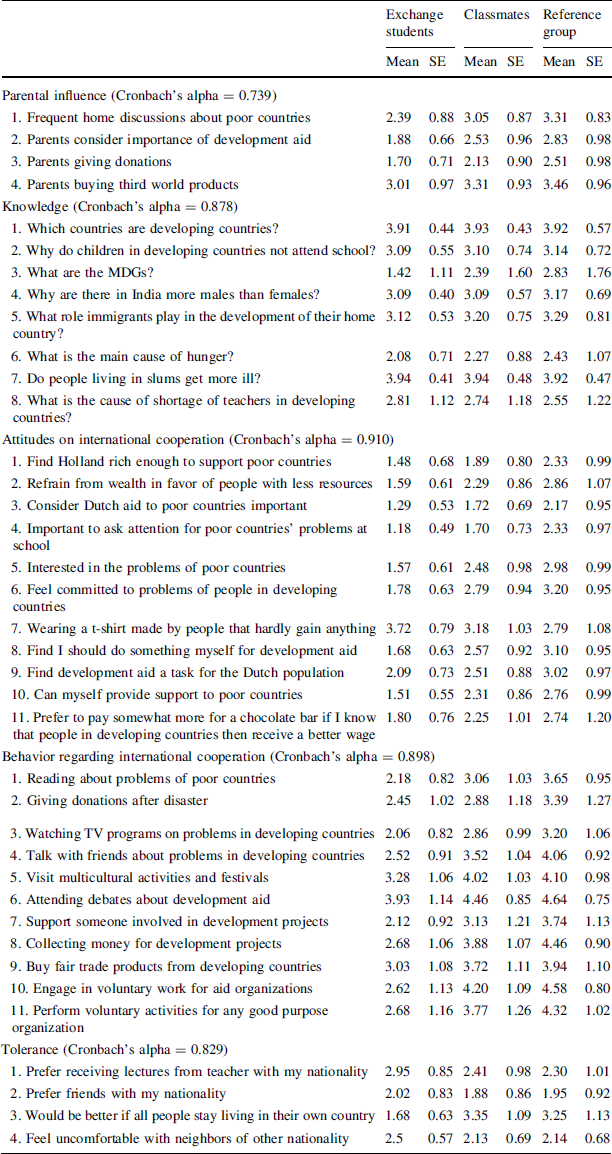

The four key dimensions of the survey included a series of statements regarding: (a) knowledge on development issues; (b) attitudes on international cooperation; (c) behavior in international solidarity; and, (d) tolerance vis-à-vis ethnic minorities. The knowledge questions could yield eight points, while the statements were recorded on a four or five points Likert scale for answers ranging from low (1) to high (4/5) degree of agreement. In addition, some questions were included to acknowledge parental influence. Annex 1 provides an outline of the different statements and their average scores and standard deviation for each of the three groups.

Data analysis is based on a careful process of propensity score matching (PSM) to control for the variation in intrinsic characteristics between the three groups of students (Ravallion Reference Ravallion2001; Rubin Reference Rubin1974). This procedure guarantees that differences in attitudinal variables are weighted for variation in group composition, thus guaranteeing that the results can be attributed to the role of the interventions by the Going Global program. Just taking the mean outcome of (in)direct participants and non-participants is likely to generate selection bias, since they usually differ even in the absence of treatment. We relied on a “matching” approach (Heckman et al. Reference Heckman, Ichimura and Todd1997; Smith Reference Smith1997; Rosenbaum and Rubin Reference Rosenbaum and Rubin1983; Rubin Reference Rubin1974; Rubin and Thomas Reference Rubin and Thomas1996) to address the selection problem. Its basic idea is to identify within the group of indirect participants those individuals who are similar to the participants in all observable pre-treatment characteristics. Rosenbaum and Rubin (Reference Rosenbaum and Rubin1983) suggest the use of balancing scores, i.e., functions of the relevant observed variables (like age, education, religion, residence, etc.) where the distribution of the outcomes is largely independent of the treatment. A commonly used balancing score is based on the probability of participating in the program given certain observed characteristics. Matching procedures based on this balancing score are known as PSM and are applied in our subsequent analysis of the role of the Edukans exchange program (Caliendo and Kopeing Reference Caliendo and Kopeing2005).

Whereas the selected analytical procedure provides clear insights in the differential effects of the international exchange program on attitudes and behavior, we cannot directly infer from these results that the possible changes in these variables are only due to their participation. Ideally, we would like to have information from the same students over time (e.g., before and after their engagement with the program) to enable insight in the counterfactual (e.g., what would have happened without participation in the program). As a robustness check, we account for possible unobservable heterogeneity through means of estimating Rosenbaum bounds.

Research Results

Most exchange students in the Going Global program maintain a strong engagement with international cooperation. Among this group of students, 85–90% declare to be better informed about and more involved in development issues. A quarter of this group returned to developing countries, around half of them remained active in development cooperation programs, and three quarters are engaged in voluntary work. Similar, but less pronounced effects are reported among the group of schoolmates that indicate to be better informed (60%) and more interested (40%) in international cooperation issues.

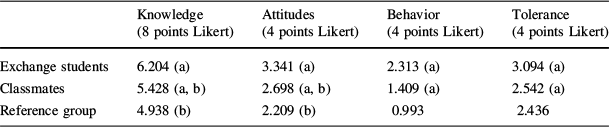

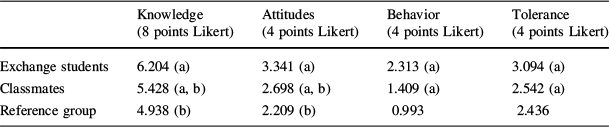

In order to verify how and whether these effects can be attributed to their engagement with the Going Global program, the survey answers on the set of questions regarding knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and tolerance need to be compared (see Table 2). Students involved in the exchange program record a higher score on all dimensions. This could be an indication of the positive effect of the program, but it might also be due to selection bias, e.g., if the program involves particularly students that are already fairly aware of international cooperation issues.

Table 2 Average scores on dimensions of societal support

|

Knowledge (8 points Likert) |

Attitudes (4 points Likert) |

Behavior (4 points Likert) |

Tolerance (4 points Likert) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Exchange students |

6.204 (a) |

3.341 (a) |

2.313 (a) |

3.094 (a) |

|

Classmates |

5.428 (a, b) |

2.698 (a, b) |

1.409 (a) |

2.542 (a) |

|

Reference group |

4.938 (b) |

2.209 (b) |

0.993 |

2.436 |

N = 1070

Note: (a) and (b) indicate significant differences (at 95% confidence level)

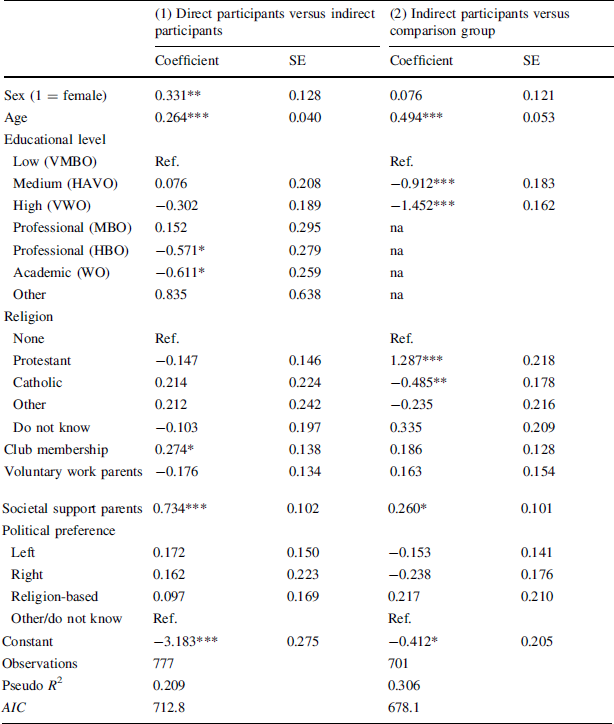

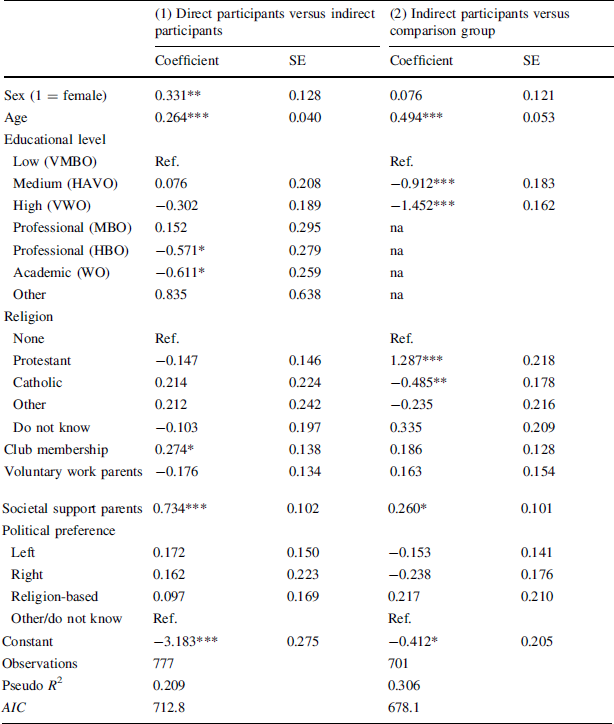

Further analysis of the data requires that the outcomes are corrected for differences in group composition. We need to control for the role of individual, family, and school variables that influence the attitudes and behavior regarding development cooperation. We therefore estimate two probit models to identify the propensity scores for, respectively, direct and indirect participants, and for indirect participants and the comparison group. Direct participants are significantly different from indirect participants in terms of gender, education, club membership, and the societal support of the parents. Indirect participants are significantly different from the comparison group in terms of age, education, religion, and the societal support of the parents. We control for these differences through means of nearest-neighbor and kernel matching in the remainder of this article. The full probit models are included in Annex 2.

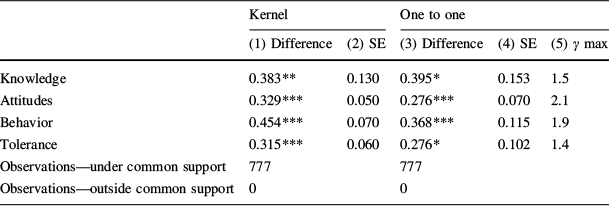

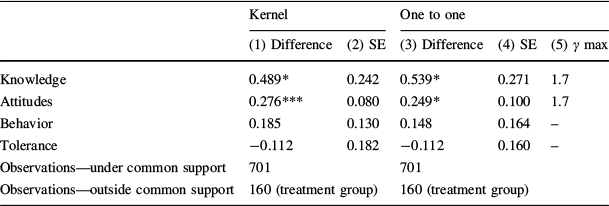

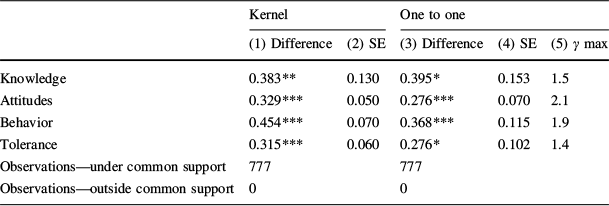

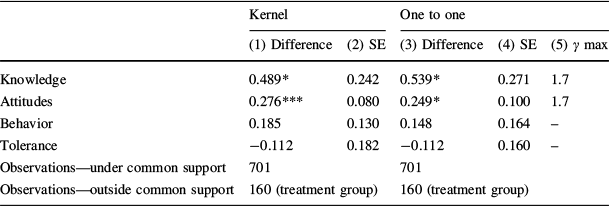

Next, we estimate the differences in scores of the impact dimensions for the direct and indirect participants (Table 3) and between the indirect participants and the comparison group (Table 4) for those students that belong to the common support domain. The impact of participation in the Going Global exchange program is undoubtedly positive for the exchange students on all four dimensions. Moreover, classmates also exhibit significantly higher scores compared to the reference group, except for the dimensions of behavior and tolerance. This may be considered as an indication for positive externalities forthcoming from the exchange program. Most positive impact is realized in the areas of knowledge and attitudes regarding issues of international development, whereas world-view changes toward global citizenship and respect for cultural or ethnic minorities in their own society are more difficult to reach for the latter group.

Table 3 Direct beneficiaries versus indirect beneficiaries

|

Kernel |

One to one |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) Difference |

(2) SE |

(3) Difference |

(4) SE |

(5) γ max |

|

|

Knowledge |

0.383** |

0.130 |

0.395* |

0.153 |

1.5 |

|

Attitudes |

0.329*** |

0.050 |

0.276*** |

0.070 |

2.1 |

|

Behavior |

0.454*** |

0.070 |

0.368*** |

0.115 |

1.9 |

|

Tolerance |

0.315*** |

0.060 |

0.276* |

0.102 |

1.4 |

|

Observations—under common support |

777 |

777 |

|||

|

Observations—outside common support |

0 |

0 |

|||

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Table 4 Indirect beneficiaries versus reference group

|

Kernel |

One to one |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) Difference |

(2) SE |

(3) Difference |

(4) SE |

(5) γ max |

|

|

Knowledge |

0.489* |

0.242 |

0.539* |

0.271 |

1.7 |

|

Attitudes |

0.276*** |

0.080 |

0.249* |

0.100 |

1.7 |

|

Behavior |

0.185 |

0.130 |

0.148 |

0.164 |

– |

|

Tolerance |

−0.112 |

0.182 |

−0.112 |

0.160 |

– |

|

Observations—under common support |

701 |

701 |

|||

|

Observations—outside common support |

160 (treatment group) |

160 (treatment group) |

|||

Tolerance appears to be the most difficult factor to influence. The expectation of Edukans that an increased tolerance would be a side-effect of the Going Global program only could be confirmed for the exchange students. The Edukans program does not explicitly address tolerance in its program, and this might explain why a positive effect on tolerance could not be registered for the schoolmates. The Going Global program has the most profound effect on the knowledge and attitudes dimensions, and much less on behavior.Footnote 5 This latter finding might be explained from the fact that the Going Global program focuses in particular on fund-raising events such as the sponsored walks and dance parties, and is not explicitly promoting other types of behavioral change. Moreover, knowledge and attitudes have proven to be more easily changeable than behavior in other studies as well, which indicates that increased knowledge does not necessarily and directly translate into behavior change (Finger Reference Finger1994).

Another interesting result of the survey concerns the specific impact of differences in schooling and educational level on societal support base parameters. It is commonly supposed that students of higher degree schooling programs will be more likely to become supportive of development cooperation programs. When correcting for schooling levels, the earlier found impact of the Going Global program on knowledge is retained. Even though students in lower degree education generally record a lower score on all support base dimensions, these differences are mostly not significant. The effect of the Going Global program among participants and non-participants in lower degree school types is particularly strong for the attitudinal dimension, and this effect is also substantially larger compared to the differences between both groups for mid- and high-level schooling degree types. This indicates a high effectiveness of the Going Global exchange program particularly among students involved in lower degree secondary education, contrary to the common assumption that attitudinal change is difficult to enforce with this category of students.

Robustness Checks

Frequently forwarded concerns with respect to the impact measurement of societal support base programs refer to the likelihood of self-selection. The specific contribution of the Going Global program was also assessed by comparing the attitudes of exchange students with similar students that otherwise visited developing countries (N = 132). This analysis confirmed the higher scores of the former group on all support base dimensions, thus indicating that mere contacts with development countries are not a sufficient condition for greater support base, and that the Going Global experience significantly contributes to a stronger commitment to international cooperation.

As discussed earlier, propensity score matching results can be biased by unobservable characteristics. The above results might be changed by factors that are not in the data. Recently, Becker and Caliendo (Reference Becker and Caliendo2007) suggest an indirect check for this condition by asking the question how large the effect of the unobservables needs to be in order to reverse the results found. We follow Johar (Reference Johar2009) in estimating these Rosenbaum bounds. Column 5 in Tables 3 and 4 show that unobservable heterogeneity has to be remarkably large, to change the qualitative findings of our results.

For both attitudes and behavior, the difference between direct participants and their peers stays significant at the 90% significance level for effects that would increase the odds of being treated with 1.9. The effect on tolerance and knowledge levels is slightly less robust to inclusion of unobservable heterogeneity. Even with relatively large magnitudes of unobserved heterogeneity, the impact of the Going Global program stays significantly positive. It is thus very likely that the program has increased societal support for its beneficiaries.

The same result holds when comparing peers with the comparison group. Increasing the odds of being treated with 1.7 does not rule out the positive effect of the Going Global program on attitude and knowledge of peers at the 90% significance level. Again, the results are remarkably robust to inclusion of unobserved heterogeneity.

Discussion and Conclusions

Programs for development education and consciousness-raising are increasingly evaluated against the background of their contributions to the societal support base for international cooperation. With the changing social structure and the secularization of value systems in Western societies, it becomes important to understand how young people establish their opinions regarding development cooperation programs. In the past, parental guidance and religious or political affiliation guaranteed to a large extent access to information and civil consent on development aid efforts. However, the current influence of global communication and youth involvement in networks make their attitudes and behavior subject to a far more diffuse process.

Relying on a unique data set of secondary school children in The Netherlands that have been involved in a specific international exchange program, we were able to trace the particular impact of peer-group exchange on the establishment of the knowledge base and related changes in attitudes and behavior regarding the importance attached to (public or private) development cooperation. In order to guarantee an un-biased assessment, survey results were compared among direct participants in international exchange visits organized by the Dutch Edukans Foundation, their schoolmates, and a reference group. Results are controlled for intrinsic differences in group and personal characteristics, and subsequent differences in knowledge, attitudes, and behavior, as well as tolerance levels, were compared among the three different groups.

The outcomes of the analysis confirm the effect on societal support of directly involving students in international exchange programs. Significant positive effects are registered particularly for all dimensions of attitude and most aspects of behavior. Also the knowledge on development issues among the exchange students is substantially higher. In addition, the program effects extend beyond the exchange students. The classmates of these exchange students show a more positive attitude towards development cooperation and display greater knowledge on the topic as a result of the program. The effects on increased tolerance are still visible with the exchange students, but externalities on the other group are not confirmed.

Our analysis confirms the importance of development education activities for maintaining and creating a wider societal support base for international cooperation. Although no direct cost–benefit analysis was made, the registered effects were quite substantial. The positive effects on the knowledge and attitudes of the exchange students and the spill-over effects to their schoolmates can be considered as a robust impact measurement. It would be interesting to investigate further implications of this in terms of practical actions and/or concrete involvement in development activities.Footnote 6 It is commonly assumed that the current youth generation prefers to engage in activities that offer a direct, concrete, and legitimate action perspective. The Edukans Going Global program can thus be considered as a successful example of direct peer exchange that contributes to a significant strengthening of civil society.

Appendix

Annex 1 Attitudinal statements (average score and standard deviation)

|

Exchange students |

Classmates |

Reference group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean |

SE |

Mean |

SE |

Mean |

SE |

|

|

Parental influence (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.739) |

||||||

|

1. Frequent home discussions about poor countries |

2.39 |

0.88 |

3.05 |

0.87 |

3.31 |

0.83 |

|

2. Parents consider importance of development aid |

1.88 |

0.66 |

2.53 |

0.96 |

2.83 |

0.98 |

|

3. Parents giving donations |

1.70 |

0.71 |

2.13 |

0.90 |

2.51 |

0.98 |

|

4. Parents buying third world products |

3.01 |

0.97 |

3.31 |

0.93 |

3.46 |

0.96 |

|

Knowledge (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.878) |

||||||

|

1. Which countries are developing countries? |

3.91 |

0.44 |

3.93 |

0.43 |

3.92 |

0.57 |

|

2. Why do children in developing countries not attend school? |

3.09 |

0.55 |

3.10 |

0.74 |

3.14 |

0.72 |

|

3. What are the MDGs? |

1.42 |

1.11 |

2.39 |

1.60 |

2.83 |

1.76 |

|

4. Why are there in India more males than females? |

3.09 |

0.40 |

3.09 |

0.57 |

3.17 |

0.69 |

|

5. What role immigrants play in the development of their home country? |

3.12 |

0.53 |

3.20 |

0.75 |

3.29 |

0.81 |

|

6. What is the main cause of hunger? |

2.08 |

0.71 |

2.27 |

0.88 |

2.43 |

1.07 |

|

7. Do people living in slums get more ill? |

3.94 |

0.41 |

3.94 |

0.48 |

3.92 |

0.47 |

|

8. What is the cause of shortage of teachers in developing countries? |

2.81 |

1.12 |

2.74 |

1.18 |

2.55 |

1.22 |

|

Attitudes on international cooperation (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.910) |

||||||

|

1. Find Holland rich enough to support poor countries |

1.48 |

0.68 |

1.89 |

0.80 |

2.33 |

0.99 |

|

2. Refrain from wealth in favor of people with less resources |

1.59 |

0.61 |

2.29 |

0.86 |

2.86 |

1.07 |

|

3. Consider Dutch aid to poor countries important |

1.29 |

0.53 |

1.72 |

0.69 |

2.17 |

0.95 |

|

4. Important to ask attention for poor countries’ problems at school |

1.18 |

0.49 |

1.70 |

0.73 |

2.33 |

0.97 |

|

5. Interested in the problems of poor countries |

1.57 |

0.61 |

2.48 |

0.98 |

2.98 |

0.99 |

|

6. Feel committed to problems of people in developing countries |

1.78 |

0.63 |

2.79 |

0.94 |

3.20 |

0.95 |

|

7. Wearing a t-shirt made by people that hardly gain anything |

3.72 |

0.79 |

3.18 |

1.03 |

2.79 |

1.08 |

|

8. Find I should do something myself for development aid |

1.68 |

0.63 |

2.57 |

0.92 |

3.10 |

0.95 |

|

9. Find development aid a task for the Dutch population |

2.09 |

0.73 |

2.51 |

0.88 |

3.02 |

0.97 |

|

10. Can myself provide support to poor countries |

1.51 |

0.55 |

2.31 |

0.86 |

2.76 |

0.99 |

|

11. Prefer to pay somewhat more for a chocolate bar if I know that people in developing countries then receive a better wage |

1.80 |

0.76 |

2.25 |

1.01 |

2.74 |

1.20 |

|

Behavior regarding international cooperation (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.898) |

||||||

|

1. Reading about problems of poor countries |

2.18 |

0.82 |

3.06 |

1.03 |

3.65 |

0.95 |

|

2. Giving donations after disaster |

2.45 |

1.02 |

2.88 |

1.18 |

3.39 |

1.27 |

|

3. Watching TV programs on problems in developing countries |

2.06 |

0.82 |

2.86 |

0.99 |

3.20 |

1.06 |

|

4. Talk with friends about problems in developing countries |

2.52 |

0.91 |

3.52 |

1.04 |

4.06 |

0.92 |

|

5. Visit multicultural activities and festivals |

3.28 |

1.06 |

4.02 |

1.03 |

4.10 |

0.98 |

|

6. Attending debates about development aid |

3.93 |

1.14 |

4.46 |

0.85 |

4.64 |

0.75 |

|

7. Support someone involved in development projects |

2.12 |

0.92 |

3.13 |

1.21 |

3.74 |

1.13 |

|

8. Collecting money for development projects |

2.68 |

1.06 |

3.88 |

1.07 |

4.46 |

0.90 |

|

9. Buy fair trade products from developing countries |

3.03 |

1.08 |

3.72 |

1.11 |

3.94 |

1.10 |

|

10. Engage in voluntary work for aid organizations |

2.62 |

1.13 |

4.20 |

1.09 |

4.58 |

0.80 |

|

11. Perform voluntary activities for any good purpose organization |

2.68 |

1.16 |

3.77 |

1.26 |

4.32 |

1.02 |

|

Tolerance (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.829) |

||||||

|

1. Prefer receiving lectures from teacher with my nationality |

2.95 |

0.85 |

2.41 |

0.98 |

2.30 |

1.01 |

|

2. Prefer friends with my nationality |

2.02 |

0.83 |

1.88 |

0.86 |

1.95 |

0.92 |

|

3. Would be better if all people stay living in their own country |

1.68 |

0.63 |

3.35 |

1.09 |

3.25 |

1.13 |

|

4. Feel uncomfortable with neighbors of other nationality |

2.5 |

0.57 |

2.13 |

0.69 |

2.14 |

0.68 |

Annex 2 Probit models

|

(1) Direct participants versus indirect participants |

(2) Indirect participants versus comparison group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Coefficient |

SE |

Coefficient |

SE |

|

|

Sex (1 = female) |

0.331** |

0.128 |

0.076 |

0.121 |

|

Age |

0.264*** |

0.040 |

0.494*** |

0.053 |

|

Educational level |

||||

|

Low (VMBO) |

Ref. |

Ref. |

||

|

Medium (HAVO) |

0.076 |

0.208 |

−0.912*** |

0.183 |

|

High (VWO) |

−0.302 |

0.189 |

−1.452*** |

0.162 |

|

Professional (MBO) |

0.152 |

0.295 |

na |

|

|

Professional (HBO) |

−0.571* |

0.279 |

na |

|

|

Academic (WO) |

−0.611* |

0.259 |

na |

|

|

Other |

0.835 |

0.638 |

na |

|

|

Religion |

||||

|

None |

Ref. |

Ref. |

||

|

Protestant |

−0.147 |

0.146 |

1.287*** |

0.218 |

|

Catholic |

0.214 |

0.224 |

−0.485** |

0.178 |

|

Other |

0.212 |

0.242 |

−0.235 |

0.216 |

|

Do not know |

−0.103 |

0.197 |

0.335 |

0.209 |

|

Club membership |

0.274* |

0.138 |

0.186 |

0.128 |

|

Voluntary work parents |

−0.176 |

0.134 |

0.163 |

0.154 |

|

Societal support parents |

0.734*** |

0.102 |

0.260* |

0.101 |

|

Political preference |

||||

|

Left |

0.172 |

0.150 |

−0.153 |

0.141 |

|

Right |

0.162 |

0.223 |

−0.238 |

0.176 |

|

Religion-based |

0.097 |

0.169 |

0.217 |

0.210 |

|

Other/do not know |

Ref. |

Ref. |

||

|

Constant |

−3.183*** |

0.275 |

−0.412* |

0.205 |

|

Observations |

777 |

701 |

||

|

Pseudo R 2 |

0.209 |

0.306 |

||

|

AIC |

712.8 |

678.1 |

||

ref reference group; na not applicable

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001