Introduction

Advancements in social and behavioral sciences have created an extensive evidence base regarding how we can intervene to improve the psychosocial and behavioral outcomes of individuals, groups, and communities facing a variety of complex issues and challenges. This evidence has supported the development, implementation, and evaluation of psychosocial and behavioral interventions (e.g., “any intervention that emphasizes psychological or social factors rather than biological factors [Reference Ruddy and House1, p.3],”) addressing diverse issues like mental health, family relationships, parenting, substance use, chronic disease management, and violence prevention. These interventions are often complex, targeting an interconnected web of risk and protective factors to improve participant outcomes [Reference Skivington, Matthews and Simpson2]. Although significant progress has been made in psychosocial and behavioral interventions, gaps remain in understanding their implementation, including their adoption by intended audiences, their acceptability to participants, and the fidelity with which they are implemented in practice [Reference Akiba, Powell, Pence, Nguyen, Golin and Go3–Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan5]. Addressing these gaps is a priority of implementation science, a field which seeks to understand and improve strategies for integrating evidence-based interventions in real-world practice as well as to improve their quality and outcomes [Reference Damschroder, Reardon, Widerquist and Lowery6–Reference Peters, Adam, Alonge, Agyepong and Tran9].

A significant focus of the implementation science literature is fidelity – the extent to which interventions are implemented as intended [Reference Bumbarger and Perkins10–Reference Dusenbury, Brannigan, Falco and Hansen12]. Fidelity is a core feature for evaluating intervention effectiveness and replicability. Fidelity is conceptualized through various models and frameworks, each comprising multiple components. Examples include the National Institute of Health Behavior Change Consortium Framework (which recommends considering fidelity as it relates to study design, training, treatment delivery, treatment receipt, and enactment of treatment skills) [Reference Bellg, Borrelli and Resnick13] and the Conceptual Framework of Implementation Outcomes (which recommends considering fidelity as it relates to adherence, dosage, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness and program differentiation) [Reference Carroll, Patterson, Wood, Booth, Rick and Balain14]. Although models and frameworks emphasize the many components of fidelity, researchers and practitioners most often collect data on how faithfully interventions are delivered because this information is essential for understanding how and why an intervention works and for identifying opportunities for continuous improvement [Reference Carroll, Patterson, Wood, Booth, Rick and Balain14,Reference Breitenstein, Gross, Garvey, Hill, Fogg and Resnick15]. Data on the delivery of an intervention can provide practical insights regarding implementation challenges (e.g., what is and is not feasible to deliver) and intervention effectiveness (e.g., why intervention effects are poorer in some contexts) [Reference Shenderovich, Lachman and Ward16,17]. Evaluating and reporting on fidelity of delivery is a critical aspect of intervention research and practice, as the quality and consistency with which an intervention is delivered are hypothesized to influence participant outcomes. Indeed, some studies have shown fidelity of delivery to be associated with improved participant outcomes [Reference Carroll, Patterson, Wood, Booth, Rick and Balain14,Reference Breitenstein, Gross, Garvey, Hill, Fogg and Resnick15,Reference Durlak and DuPre18]. Despite its importance, fidelity of delivery is often neither measured with reliable and valid tools nor reported in detail [Reference Martin, Steele, Lachman and Gardner19–Reference Stirman21].

Recently, we (Martin and colleagues) proposed a preliminary guideline for reporting on the fidelity of delivering parenting interventions [Reference Martin, Shenderovich, Caron, Smith, Siu and Breitenstein22]. Parenting interventions were chosen as the initial focus of the guideline because they align with the first and senior authors’ expertise, who identified the need for a fidelity of delivery reporting guideline, and because these interventions are complex, involving multiple components [Reference Petticrew23]. However, it became apparent that the guideline could be expanded to other psychosocial and behavioral interventions with similar complexity, and multicomponent structures. The purpose of this study was to refine the fidelity of delivery reporting guideline and broaden it to be relevant for a range of psychosocial and behavioral interventions. While this reporting guideline focuses only on fidelity of delivery, this does not take away from the importance of reporting on other components of fidelity and should be the focus of future work. In the rest of this paper, when we discuss fidelity, we are only referring to delivery fidelity.

Materials and methods

This study employed a modified Delphi technique, including surveys, consensus meetings, and iterative revisions, to refine the Fidelity of Intervention delivery in Psychosocial and behavioral Programs (FIPP) guideline [Reference Nasa, Jain and Juneja24].

FIPP development

The first iteration of the FIPP, developed with expert input and a literature review, consisted of six categories (intervention characteristics; intervention facilitator characteristics; fidelity assessor characteristics; fidelity measure characteristics; fidelity results; and bias) and 34 items. More details on this measure and the process used to develop it are provided in Martin et al. [Reference Martin, Shenderovich, Caron, Smith, Siu and Breitenstein22].

Participants

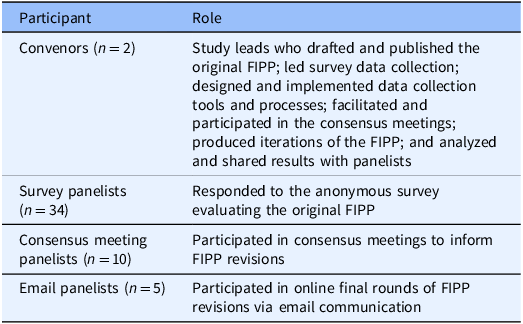

This study engaged two participant types – panel convenors and panelists (Table 1). Panel convenors drafted and published the original FIPP, generated and implemented data collection tools and processes, facilitated consensus meetings, produced iterations of the FIPP, and analyzed and shared results. Three groups of panelists were engaged. Survey panelists included anonymous individuals who completed an online survey about the original FIPP. Survey panelists were recruited using a link to the survey shared in the published commentary on the original FIPP [Reference Martin, Shenderovich, Caron, Smith, Siu and Breitenstein22]; word of mouth; and advertising in implementation science newsletters. Survey panelists were invited to share their email address if they were interested in participating in consensus meetings. Consensus meeting and email panelists included implementation science researchers and practitioners with expertise in collecting, using, and reporting on fidelity in their respective fields. Consensus meeting panelists represented a heterogeneity of viewpoints, interventions, and experiences with fidelity reporting. Email panelists were recruited by invitation from the panel convenors due to their research on implementation science and fidelity in a wide range of interventions. These panelists were added to the study following the consensus meetings based on feedback that the FIPP should be broadened to other types of interventions. There was no overlap in the panelists who participated in the consensus meetings and email communication.

Table 1. Participants in FIPP (fidelity of intervention delivery in psychosocial and behavioral programs) development (N = 51)

Modified Delphi data collection and analysis

The study adhered to the general recommendations outlined in the Delphi Critical Appraisal Tool [Reference Khodyakov, Grant, Kroger and Bauman25], using a modified Delphi approach with one survey round, two consensus meetings, online feedback, and iterative revisions. Seven steps were used to conduct this study, resulting in six rounds of iterative revisions to the FIPP.

-

1. Survey: The online survey launched in September 2023 and was open for six months. The survey had 42 questions and used a three-point Likert scale (very important = 3; not sure = 2; not important = 1) followed by a comment box for respondents to provide details and suggested revisions (see Supplemental Material 1 for FIPP Survey). An open-ended question at the end of the survey allowed respondents to identify any other items to include. Respondents could provide their email address if they were interested in participating in the consensus meetings.

-

2. Survey Analysis and FIPP Revisions: The convenors analyzed survey responses, compiling findings at an item level by summarizing the percentage of respondents who selected each response option as well as how many respondents did not answer each item. A report summarizing these findings guided preliminary FIPP revisions for consensus discussions.

-

3. Consensus Meetings with Panelists: The purpose of the virtual meetings, held in August and September 2024, was to review the survey outcomes and revised FIPP items to reach consensus on FIPP item inclusion and wording. It was at this stage that the focus of the reporting guideline broadened to all psychosocial and behavioral interventions.

-

4. Revisions and Further Panelist Feedback: The convenors reviewed meeting notes, making further FIPP modifications. The revised FIPP was emailed to the panelists for further written feedback and edits.

-

5. Revisions and Email Panelist Feedback: The FIPP was revised to broaden the application of the guideline to psychosocial and behavioral interventions. Invited implementation fidelity experts reviewed the revised FIPP and provided written feedback.

-

6. Final Feedback: Revisions broadened FIPP’s application to other psychosocial and behavioral interventions. The updated FIPP was circulated to all panelists for final comments.

-

7. Final FIPP: The convenors incorporated all feedback to produce the final FIPP guideline.

Ethics

This study was determined to be exempt from IRB review by the Ohio State University Office of Responsible Research Practices (2022E0017).

Results

Participants

Anonymous survey panelists (n = 34) provided details on their background and expertise and shared views on FIPP items. Among them, 19 identified as researchers or scientists; 18 as parenting program staff; 14 as parenting program coaches, supervisors, or consultants; 12 as parent program facilitators; and 10 as assessors of facilitator delivery. Consensus meeting panelists (n = 10) participated in discussions about the FIPP, primarily focusing on parenting interventions and represented academic and practice perspectives. Finally, email panelists (n = 5), all of whom were academics with expertise in implementation science and fidelity, contributed feedback at the invitation of the convenors.

Survey

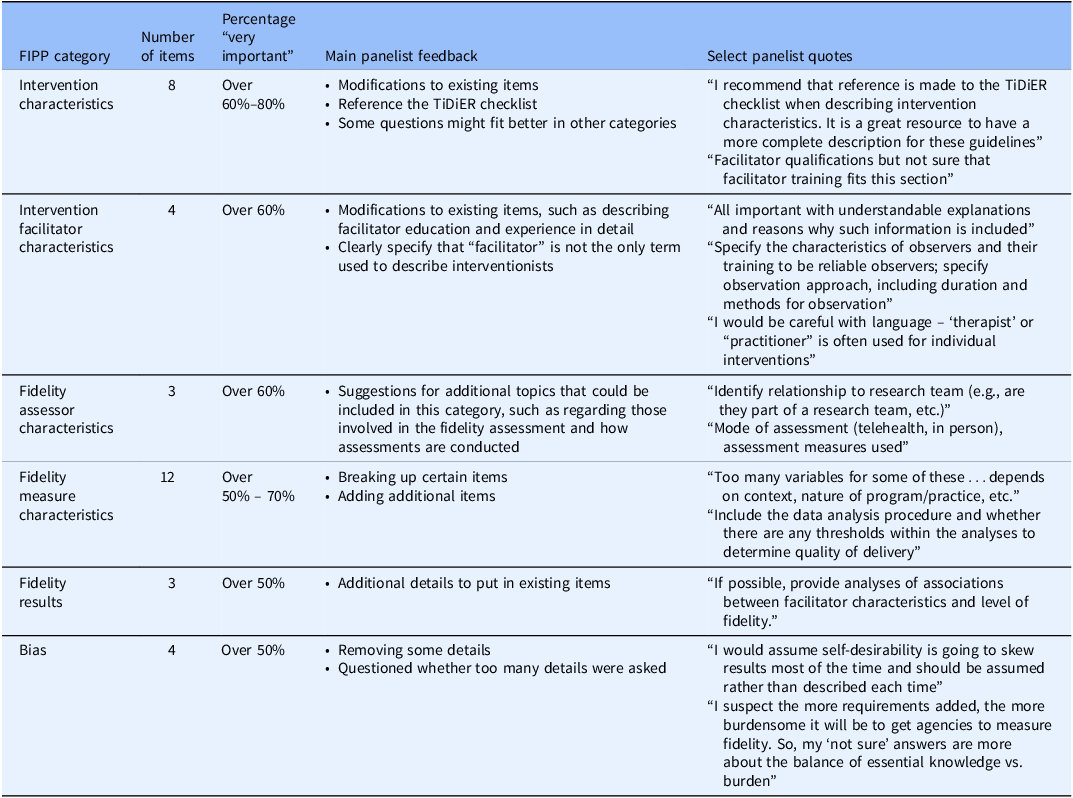

Of the 34 FIPP items listed in the survey, 50% of respondents rated all items as very important. A summary of the survey results are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of FIPP (fidelity of intervention delivery in psychosocial and behavioral programs) survey results (n = 34)

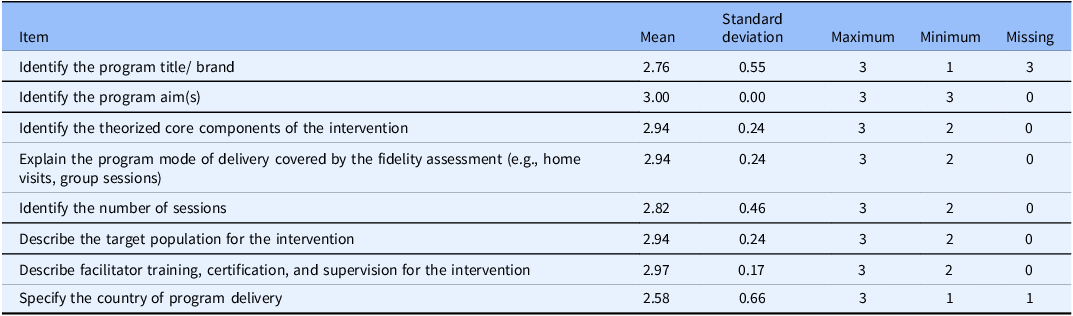

Intervention characteristics

All eight items in the intervention characteristics category received a “very important” by more than 65% of respondents, with seven of the eight items receiving this rating from over 80% of participants (see Table 3). Comments suggested a few potential revisions, referencing the TiDiER framework (e.g., standards for intervention reporting) and reconsidering placement of certain questions – such as whether the item on facilitator training might be better suited to a different category. This feedback is reflected in the following: “I recommend that reference is made to the TiDiER checklist when describing intervention characteristics. It is a great resource to have a more complete description for these guidelines” and “Facilitator qualifications but not sure that facilitator training fits this section.”

Table 3. Category 1 – intervention characteristics survey results (n = 34)

Note: Items were rated on a scale from 1 (Not important) to 3 (Very important).

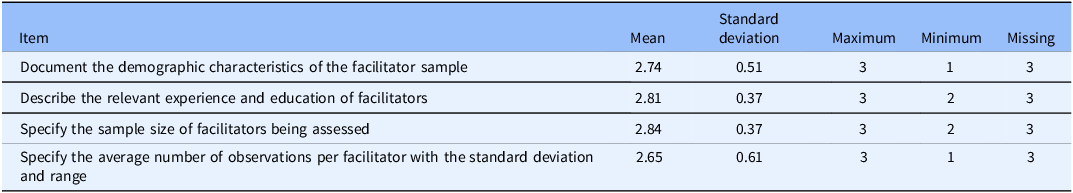

Intervention facilitator characteristics

The four items in the intervention facilitator category were rated as “very important” by over 71% of respondents (see Table 4). This view was reflected in respondent comments, such as: “All important with understandable explanations and reasons why such information is included.” However, comments indicated potential revisions that could be made to some items, including describing facilitator education and experience in detail (item 2): “Specify the characteristics of observers and their training to be reliable observers; specify observation approach, including duration and methods for observation.” Comments also suggested that the guideline clearly specify that “facilitator” is not the only term used to describe interventionists: “I would be careful with language – ‘therapist’ or “practitioner” is often used for individual interventions.”

Table 4. Category 2 – intervention facilitator characteristics survey results (n = 34)

Note: Items were rated on a scale from 1 (Not important) to 3 (Very important).

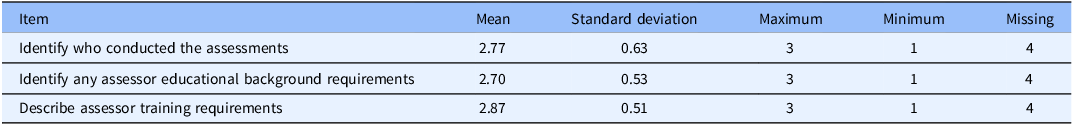

Fidelity assessor characteristics

The three items in the fidelity assessor category were rated as “very important” by over 73% of respondents (see Table 5). Comments included suggestions for additional topics that could be included in this category such as “Identify relationship to research team (e.g., are they part of a research team)” and “Mode of assessment (telehealth, in person), assessment measures used.”

Table 5. Category 3 – fidelity assessor characteristics survey results (n = 34)

Note: Items were rated on a scale from 1 (Not important) to 3 (Very important).

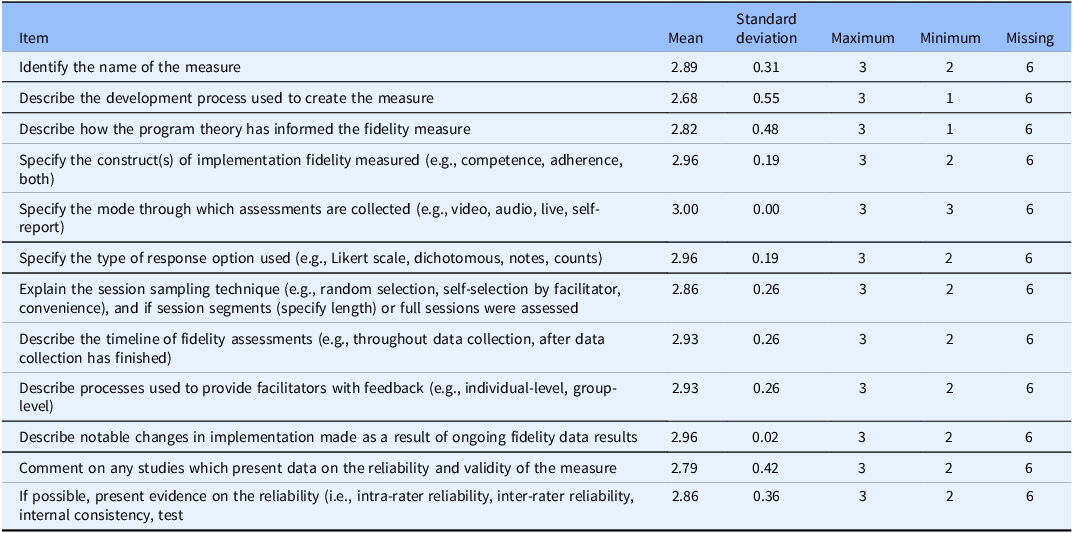

Fidelity measure characteristics

All12 items in this category were rated as “very important” by over 50% of respondents (or over 71% those who responded to the questions), with most of the items being rated as “very important” by over 70% of participants (see Table 6). Respondents suggested breaking up items (e.g., “Too many variables for some of these…depends on context, nature of program/practice, etc.”) and adding additional items (e.g., “Include the data analysis procedure and whether there are any thresholds within the analyses to determine quality of delivery”).

Table 6. Category 4 – fidelity measure characteristics survey results (n = 34)

Note: Items were rated on a scale from 1 (Not important) to 3 (Very important).

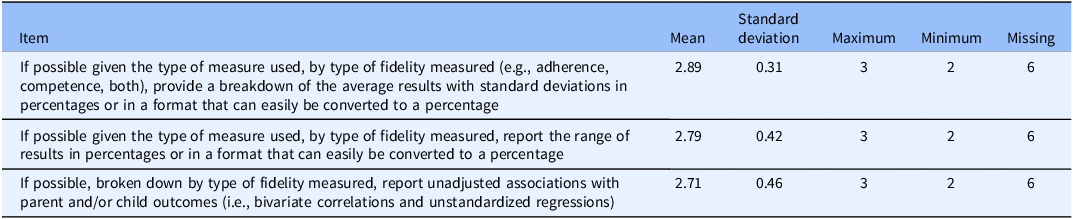

Fidelity results

Each of the three items in this category were rated as “very important” by over 50% of respondents (or over 71% of those who responded to the questions) (see Table 7). Respondent comments suggested that additional details were asked for in the items in this category, such as “If possible, provide analyses of associations between facilitator characteristics and level of fidelity.”

Table 7. Category 5 – results (Level of fidelity reported) survey results (n = 34)

Note. Items were rated on a scale from 1 (Not important) to 3 (Very important).

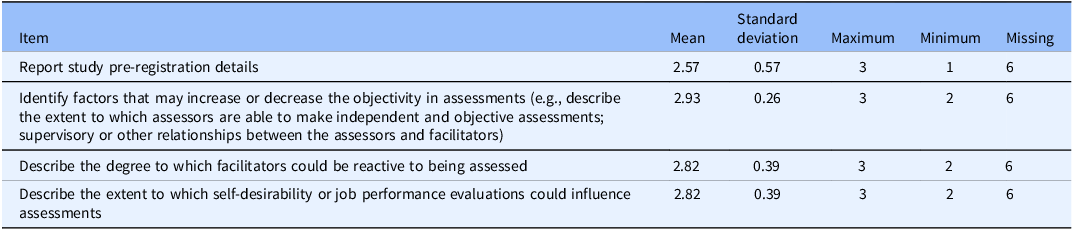

Bias

Each of the four items in this category were rated as “very important” by over 50% of respondents (or over 61% of those who responded to the questions) (see Table 8). Overall, respondents were satisfied with this category, as is illustrated by the following: “Really important for studies being written up and reported.” In their comments, respondents suggested removing some details (e.g., “I would assume self-desirability is going to skew results most of the time and should be assumed rather than described each time”) and questioned whether too many details were asked of those reporting on fidelity (e.g., “I suspect the more requirements added, the more burdensome it will be to get agencies to measure fidelity. So, my ‘not sure’ answers are more about the balance of essential knowledge vs. burden”).

Table 8. Category 6 – bias survey results (n = 34)

Note. Items were rated on a scale from 1 (Not important) to 3 (Very important).

Consensus meeting feedback with parenting program experts

Feeback from consensus meetings led to substantial revisions to the FIPP. Panelists emphasized expanding the scope of the FIPP beyond parenting programs to include various psychosocial and behavioral interventions. Accordingly, panelists recommended that implementation scientists working on other psychosocial and behavioral interventions be consulted to gather their input on the FIPP (e.g., “we should get input from other fidelity stakeholders” and “make sure that the various questions apply to [other] psychosocial programs”). Panelists also recommended rewording and clarifying items for better usability, with particular focus on the categories of intervention characteristics and fidelity measure characteristics (e.g., it was suggested that the item summarizing fidelity results be expanded to include qualitative findings, not just quantitative findings). Terminology adjustments were suggested to accommodate diverse intervention formats (e.g., ensure the wording accommodated programs that were self-delivered, rather than assuming all would have a facilitator) along with ideas for reordering items to enhance flow (e.g., recommendation to present intervention outcomes prior to specific details on intervention delivery). Finally, panelists suggested providing item definitions and examples to improve item clarity (e.g., the item on core intervention ingredients include a list of what this could mean, resulting in the addition of a list of examples – materials, activities, and support).

Email feedback from implementation scientists

Email panelists further refined the FIPP by recommending adjustments to item wording to suit diverse interventions and delivery methods, such as web-based programs. They also recommended structural changes to provide more consistency on item presentation and description. To illustrate, panelists identified the importance of clearly providing statements for FIPP users to only report on details that are applicable to their intervention and situation. Finally, panelists recommended clarifying that the guideline applies to interventions at any stage of development, not limited to evidence-based programs, underscoring the importance of fidelity reporting irrespective of the intervention’s evidence quality or amount. Feedback from the email panelists prompted further revisions, and the updated FIPP was circulated to the consensus meeting and email panelists for final edits and comments.

The FIPP guideline explanation and elaboration

The final FIPP includes 35 items organized into six categories (Supplemental Material 3 for the FIPP Reporting Guideline). Below we provide a description of each FIPP item with an example. We provide examples from three evidence-based programs – Parent Management Training Oregon Model program [Reference Forgatch and Kjøbli26], the LifeSkills Training program [Reference Botvin and Griffin27], and the Parenting for Lifelong Healthprogram [Reference Martin, Lachman, Murphy, Gardner and Foran28,Reference Martin, Lachman and Calderon29].

Category 1: Intervention characteristics

Item 1. Identify the intervention(s) title/name

Description: The name used to refer to the psychosocial and behavioral intervention, program, and/or treatment.

Example 1: GenerationPMTO – Group [Reference Holtrop, Miller, Durtschi and Forgatch30].

Example 2: LifeSkills Training – Middle school [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31]

Example 3: Parenting for Lifelong Health for Parents and Adolescents (PLH-Teens) [Reference Martin, Lachman, Murphy, Gardner and Foran28].

Item 2. Describe the intervention and its active ingredients

Description: The intervention being studied and the active ingredients and/or core components (e.g., materials, activities, support) established or hypothesized to achieve targeted participant outcomes.

Example 1: GenerationPMTO is a theory-based parent training intervention to strengthen parenting and social skills. The core components include clear directions, skill encouragement, emotion regulation, limit setting, effective communication, problem solving, monitoring, and positive involvement. Active teaching approaches are used (e.g., group problem solving, role play, homework assignments, video modeling) to engage parents in learning to apply the program techniques [Reference Holtrop, Miller, Durtschi and Forgatch30,Reference Sigmarsdóttir, Rodríguez, Gewirtz, Rains, Tjaden and Forgatch32].

Example 2: The LifeSkills Training (LST) middle school program is a classroom-based universal prevention program designed to prevent adolescent tobacco, alcohol, marijuana use, and violence. Three components include personal self-management skills, social skills, and information and resistance skills (specific to drug use). Teachers use demonstration, feedback, reinforcement, and practice to teach the content [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31].

Example 3: “PLH-Teens is a low-cost, open-access parenting program developed by Parenting for Lifelong Health (PLH) to reduce violence against children and child behavioral and emotional problems among families in low- and middle-income countries…[Reference Martin, Lachman and Calderon29, p.4] ”

Item 3. Described the intended intervention outcomes

Description: The outcomes the intervention aims to achieve, including proximal and distal behavioral, psychosocial, and/or health outcomes. Descriptions of intervention outcomes may include a summary of the key mechanism(s) activating the outcome(s), logic model, or theory of change.

Example: GenerationPMTO aims to increase positive parenting skills and decrease coercive parenting and negative reinforcement with the long-term goal of improved child social and behavioral outcomes [Reference Sigmarsdóttir, Rodríguez, Gewirtz, Rains, Tjaden and Forgatch32].

Item 4. Describe the intervention’s target population

Description: The intended participant characteristics including applicable demographics (e.g., sociodemographic, diagnostic).

Example: LST was delivered to middle/junior high school students between grades 6–9 [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31].

Item 5. Describe the intervention delivery method(s)

Description: The way the intervention content is provided, including method (e.g., online/remote, in-person, hybrid) and mode (e.g., self-administered, asynchronou/asynchronous, individual, group-based).

Example: GenerationPMTO – Group is delivered in 10 weekly sessions by two to three trained facilitators. Sessions are synchronous and group based [Reference Holtrop, Piehler and Gray33].

Item 6. Describe the intervention dose

Description: The frequency (e.g., daily, weekly, monthly) and duration (e.g., minutes, hours) of intervention delivery. May include the minimum and/or maximum intended dosage of the intervention.

Example: LST consists of 30 sessions taught over three years (with 15 sessions in year 1, 10 sessions in year 2, and 5 sessions in year 3). Additional violence prevention lessons are available each year (3 sessions in year 1, 2 sessions in year 2, and 2 sessions in year 3) [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31].

Item 7. Describe the intervention delivery setting

Description: The setting or where the intervention is delivered (e.g., community agency, home-based, schools, behavioral health organization).

Example: GenerationPMTO was tested and delivered in the Michigan state public mental health system [Reference Holtrop, Piehler, Miller, Young, Tseng and Gray34].

Item 8. Identify the country of intervention delivery

Description: The country of intervention delivery and include other geographic information (e.g., state, province) relevant to understanding the intervention.

Example: GenerationPMTO was implemented nationwide in Norway [Reference Askeland, Forgatch, Apeland, Reer and Grønlie35].

Item 9. Report study pre-registration details

Description: Any pre-published documents (e.g., a protocol) or registration in reporting databases (e.g., the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) or ClinicalTrials.gov) regarding the study protocol and an online link.

Example: This study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (ID NCT01795508).

Category 2: Intervention faciltiator characteristics

Item 10. Describe the qualifications, education, and experience required of intervention facilitators

Description: The educational, professional, or other training experience requirements for facilitators to implement the intervention.

Example: LST facilitators do not require specific qualifications, however, it is typically delivered by classroom teachers, counselors, or other school staff [Reference Mihalic, Fagan and Argamaso36].

Item 11. Describe the training and supervision facilitators receive for intervention delivery

Description: Training to deliver the specific intervention and nature/length of support provided to facilitators before, during, and after intervention implementation.

Example: GenerationPMTO facilitator training includes 2–3 workshops for a total of 10 days. Training includes opportunities for practice (e.g., modeling, video demonstrations, role play, experiential exercises, and video recording of practice followed up with direct feedback). GenerationPMTO training is supported with regular coaching and consultation via phone, videoconferencing, in written format, or in person [Reference Casaburo, Asiimwe, Yzaguirre, Fang and Holtrop37].

Item 12. Describe the recruitment or selection process for intervention facilitators

Description: Strategies used to recruit facilitators and/or any criteria used to select them. Indicate whether facilitators are internal or external to the organization implementing the intervention.

Example: “A convenience sample of primarily middle school teachers from 16 Kentucky counties were invited to attend teacher training sessions and were expected to implement the LST Program with students in the classroom [Reference Hahn, Noland, Rayens and Christie38, p.283].”

Item 13. Document the number of facilitators and their demographic characteristics

Description: The individuals who acted as facilitators and their applicable educational and sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race, ethnicity).

Example: “Though health teachers comprised the largest portion of LST facilitators, this varied by school and included social studies, science, math, computer science, and language arts teachers, as well as school counselors (18.8% of districts had a counselor teach LST). On average, LST instructors had 13.9 years of teaching experience [Reference Combs, Buckley, Lain, Drewelow, Urano and Kerns39, p.972].”

Category 3: Fidelity measure characteristics

Item 14. Identify the fidelity measure(s)

Description: The name of the fidelity measure(s) used to assess fidelity.

Example: The Botvin Life Skills Training Fidelity Checklist – Middle School Level 1 – was used to assess fidelity of implementation at the classroom level [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31].

Item 15. Describe the purpose of the fidelity measure(s)

Description: The purpose of the fidelity assessment to support intervention delivery or practice (e.g., coaching, supervision, certification, monitoring, evaluation, and/or research). Describe any fidelity requirements or criteria for continued delivery of the intervention (e.g., fidelity result threshold).

Example: “PLH developed an observational assessment tool, the PLH-Teens-Facilitator Assessment Tool or PLH-FAT-T, for several reasons including to monitor facilitator fidelity as part of program dissemination of PLH-Teens across multiple settings…. Versions of the PLH-FAT-T are used in multiple LMICs for purposes including certification, assessment of the quality of program delivery, and facilitator feedback on their delivery [Reference Martin, Lachman and Calderon29, p.3].” Facilitators are typically expected to receive a 60% on their assessments to continue delivering the program [Reference Martin, Lachman and Calderon29].

Item 16. Specify the fidelity construct(s) measured and/or the fidelity framework used

Description: The specific aspects of fidelity that the measure assesses (e.g., training, competence/quality of delivery, adherence, adaptations).

Example: The Botvin Life Skills Training Fidelity Checklist – Middle School Level assesses teacher adherence, and quality of delivery [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31].

Item 17. Describe the development process of the fidelity measure(s)

Description: The item development process, who was involved in development (e.g., program authors), item revision process, and/or adaptations based on other measures.

Example: The GenerationPMTO Fidelity of Implementation Rating System (FIMP) was developed by building on two earlier observational tools and integrating insights from prior research to assess interventionists’ competent adherence to GenPMTO core components. Through an iterative process involving behavioral coding, video analysis, and refinement, five global fidelity dimensions were created to evaluate intervention delivery in the context of individual family characteristics and needs [Reference Forgatch, Patterson and DeGarmo40].

Item 18. Describe how the intervention theory and/or active ingredients informed development of the fidelity measure(s)

Description: The connection between the intervention’s outcomes, the key strategies to achieve them, and how the fidelity measure focuses on these core components.

Example: The FIMP measures five dimensions of competent adherence specified in the intervention model, including PMTO knowledge, structure, teaching skill, clinical skill, and overall effectiveness and evaluates content of core components delivered [Reference Forgatch, Patterson and DeGarmo40].

Item 19. Describe studies presenting any reliability and/or validity data of the fidelity measure(s)

Description: Citations and results of past studies of the fidelity measure(s).

Example: The fidelity checklist for LST “has been used in past evaluations and program replications of LST, with inter-rater reliability ranging from .80 to .90 (Botvin, Baker, et al., 1995; Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, Tortu, & Botvin; 1990; Botvin et al., 1989; Hahn, Noland, Rayens, & Christie, 2002; Mihalic et al., 2008) [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31, p.116].”

Item 20. Describe any materials that accompany the fidelity measure(s)

Description: Materials (e.g., fidelity coding manuals, checklists, rating criteria/rubrics, forms, and data extraction spreadsheets) required for use of the fidelity measure(s).

Example: “The FIMP manual details procedures for scoring videotapes, defines each dimension, and provides necessary forms…. For each FIMP dimension, the manual provides a general definition, description of key features, rating guidelines, and rating examples [Reference Forgatch, Patterson and DeGarmo40, p.6].”

Item 21. Describe the structure of the fidelity measure(s)

Description: The number of items/questions and subscales.

Example: “Using the tool, facilitators are assessed on the delivery of one of two program activities. The two program activities, which assess facilitator adherence to program activities, are the home activity discussion (conversation led by the facilitator to review and discuss the assigned home practice activities; 7 items) and the role-play activity (facilitator-supported exercise to support participants in practicing key skills; 8 items)…. facilitators are assessed on an additional 16 skills items related to their ability to model key parenting skills (3 items), use PLH’s ‘Accept-Explore-Connect-Practice’ technique (5 items), and demonstrate collaborative leadership skills (8 items) [Reference Martin, Lachman and Calderon29, p.7].”

Item 22. Describe the response options and scoring method used in the fidelity measure(s)

Description: The design of measure items (e.g., Likert scale, dichotomous, notes, frequency counts) and scoring, including total score possible and range of possible scores.

Example: “Each dimension [of the FIMP] is scored on a scale that ranges from 1 (no evidence of competence) to 9 (exemplary). These scores are grouped generally into the superordinate domains needs work (1–3), acceptable (4–6), and good work (7–9) [Reference Sigmarsdóttir, Rodríguez, Gewirtz, Rains, Tjaden and Forgatch32, p.5].”

Category 4: Fidelity assessment method

Item 23. Specify the mode through which fidelity assessments are conducted

Description: The mode the fidelity assessment is completed, such as via video recordings, audio recordings, live observations, or self-reports.

Example: Fidelity assessments were conducted through in-person, direct classroom observations [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31] and “The FIMP uses data from 10-minute video segments, sampled from sessions focused on two intervention components (i.e., skill encouragement and limit setting), to assess practitioners’ competent adherence to GenPMTO [Reference Holtrop, Miller, Durtschi and Forgatch30, p.295].”

Item 24. Describe the level of data collection and fidelity sampling technique

Description: The level (e.g., session, facilitator, organizational level) of data collected and sampling method (e.g., random, self-selection, convenience). Include proportion of the total used for fidelity assessment.

Example: “Sixteen middle schools were randomly chosen from the 48 schools implementing LST in the school district. Each elective teacher conducting LST in the selected schools was observed one time. Between 2 and 12 observations and fidelity checks took place at each school based on the number of teachers delivering LST in that school. Due to random selection of one lesson per teacher by the observer, the types of lessons observed varied by teacher [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31, p.116].”

Item 25. Describe the timeline of fidelity assessments

Description: When assessments were conducted (e.g., throughout intervention delivery and/or after completion). Provide justification.

Example: During program implementation, “the funding agency responsible for facilitating LST required the organization to conduct observations and fidelity checks of the program in order to assess the quality of implementation of the participating teachers and classrooms [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31, p.116].”

Item 26. Describe the method used to provide fidelity feedback

Description: When (e.g., ongoing, at the end of intervention) and how (e.g., written, aggregated report) the fidelity feedback was provided.

Example: Fidelity monitoring occurred throughout intervention delivery using the observation-based FIMP, with facilitators receiving ongoing coaching [Reference Sigmarsdóttir and Guðmundsdóttir41].

Category 5: Fidelity assessor characteristics

Item 27. Identify the fidelity assessors and where they are situated within the implementation of the intervention

Description: Who (e.g., peers, supervisors, independent observers) conducted assessments and whether assessors are internal or external to the organization implementing the intervention.

Example: “Based on a structured job description, observers were recommended by school district personnel, with the explicit guidance that observers should not be school staff or familiar with the teachers implementing to reduce bias [Reference Combs, Drewelow, Habesland, Lain and Buckley42, p.931].”

Item 28. Describe the qualifications, education, and experience required of fidelity assessors

Description: The educational, professional, or other training experience or knowledge of the intervention required for conducting fidelity assessment.

Example: “All FIMP coders are certified GenerationPMTO specialists who are also certified fidelity coders [Reference Sigmarsdóttir, Rodríguez, Gewirtz, Rains, Tjaden and Forgatch32, p.4].”

Item 29. Describe assessor training and requirements

Description: The training provided to conduct fidelity assessment. Include applicable metrics (reliability) required to conduct fidelity assessment.

Example: “A passing score for coder certification or re-certification requires at least 80% agreement on three of the four FIMP annual test spots [Reference Sigmarsdóttir, Rodríguez, Gewirtz, Rains, Tjaden and Forgatch32, p.6].” and “FIMP training requires approximately 40 h. For reliability, three to five sessions are scored; an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) score of 70% or higher is required [Reference Askeland, Forgatch, Apeland, Reer and Grønlie35, p.1193].”

Item 30. Document the number of fidelity assessors and their demographic characteristics

Description: The number and applicable educational and sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity) of the fidelity assessors.

Example: “Among the [PLH-Teens] facilitators … the mean age was 33.6 years with a range from 25 to 54 years. Ten facilitators identified as male (41.7%), eight facilitators identified as female (33.3%), and six did not provide data on their gender (25.0%). Out of the 13 facilitators who reported their caregiving status, most facilitators were parents themselves (92.3%) [Reference Martin, Lachman and Calderon29, p.10].”

Category 5: Fidelity results and discussion

Item 31. Provide a descriptive summary of the fidelity assessment results

Description: The appropriate qualitative findings (e.g., narrative, quotes) and/or descriptive statistics (e.g., frequency, mean, standard deviation, ranges) of the fidelity results appropriate to the level (e.g., organization, group, facilitator) the data were collected. Include total measure and subscale scores.

Example: Mean (SD) fidelity scores on the FIMP ranged from 6.34 (0.71) to 7.03 (0.41) with high levels of fidelity sustained over time [Reference Askeland, Forgatch, Apeland, Reer and Grønlie35].

Item 32. Report unadjusted associations with proximal, primary, and/or secondary outcomes examined or other implementation outcomes

Description: The associations of the fidelity results (e.g., bivariate correlations, unstandardized regressions) appropriate to the level the data were collected with intervention or implementation outcomes.

Example: “Increased fidelity was not significantly associated with parent-reported child maltreatment or child conduct problems. As it relates to adolescent-reported outcomes, increased fidelity was associated with a 14% decrease in child maltreatment (IRR = 0.86 [95% CI = 0.82 – 0.90, p < 0.001]), a 27% decrease in child conduct problems (IRR = 0.73 [95% CI = 0.70 – 0.77, p < 0.001]), and a 23% decrease in child emotional problems (IRR = 0.77 [95% CI = 0.69 – 0.86, p < 0.001]) [Reference Martin, Lachman and Calderon29, p.10].”

Item 33. Provide a comparison of the fidelity results reported in other studies of the same intervention

Description: The comparison of the fidelity results in the present study to other studies reporting fidelity assessments of the same intervention.

Example: “Insignificant and negative associations were also found in the study of PLH-Teens in South Africa by Shenderovich et al. (2019)…In that study, while nearly all outcomes had an insignificant relationship, higher facilitator fidelity was associated with higher levels of adolescent-reported child maltreatment [Reference Martin, Lachman and Calderon29, p.12].”

Item 34. Describe how fidelity results informed implementation and/or intervention delivery

Description: How fidelity results informed changes and/or adaptations to the intervention, intervention delivery, or implementation.

Example: The fidelity findings “suggest adaptations may need to be made to LST components and how teachers are trained and delivering lessons in order to address these students’ social and emotional learning needs [Reference Vroom, Massey, Yampolskaya and Levin31, p.119].”

Item 35. Identify any potential sources of bias on the fidelity assessments and results

Description: Describe the extent to which self-desirability, job evaluations, reactivity to being assessed, or the relationship between facilitators and assessors may have influenced fidelity assessments. Provide details on any steps to minimize bias (e.g., audio or video tape all program sessions) among those being assessed.

Example: “To prevent bias, FIMP coders do not score certification sessions from therapists in their region. When there is uncertainty about pass or fail certification status, the FIMP team determines the outcome in consensus discussion. In case of disagreement within the team, the two FIMP leaders jointly decide the final scores [Reference Askeland, Forgatch, Apeland, Reer and Grønlie35, p.1193].”

Discussion

Overview of results

This study used a modified Delphi approach to revise and update the FIPP so that it is clearer to understand, easier to use, and applicable to a broad range of psychosocial and behavioral interventions. The FIPP provides researchers and practitioners working on complex interventions in multiple fields with a guideline which outlines considerations when evaluating fidelity of delivery, as well as outlines critical topics that should be reported in publications about fidelity that are based on the recommendations of an international network of intervention and implementation science experts. Capturing details on all aspects of fidelity, including but not limited to delivery, provides critical information for understanding how fidelity data are collected and important contextual information for interpreting fidelity results [Reference Martin, Lachman, Murphy, Gardner and Foran28]. In addition, it is hoped that this guideline will advance the level of rigor in the design and reporting of studies on fidelity of delivery, in alignment with fidelity frameworks in the implementation science literature [Reference Bellg, Borrelli and Resnick13,Reference Carroll, Patterson, Wood, Booth, Rick and Balain14].

Using the FIPP guideline

While the modified Delphi approach led to the creation of the FIPP for use by researchers and practitioners, the process also generated several considerations and recommendations regarding how the FIPP can be used. First, while the FIPP provides guidance for reporting fidelity of delivery, this guideline can support researchers and practitioners planning for fidelity in the design of studies. The FIPP might be useful in this regard by outlining important considerations for fidelity measurement, data collection, and data analysis. Second, because we aimed to be comprehensive, not all FIPP items will be relevant to all types of interventions or studies. As a result, it is recommended that FIPP users select what aspects of FIPP are appropriate for their purposes. For example, web-based interventions might not need to report on items in Category 5 (Facilitator Assessor Characteristics). Third, there are several reporting guidelines that could be used alongside the FIPP, including the TiDiER and FRAME frameworks which outline considerations in reporting interventions and intervention adaptations respectively [Reference Hoffmann, Glasziou and Boutron43,Reference Wiltsey Stirman, Baumann and Miller44]. As a result, FIPP users may choose to use the FIPP in concert with other guidelines that are appropriate for their contexts, interventions, and methods. Finally, the FIPP was designed to be applicable for interventions at any stage of development and testing. In other words, the guideline was not just designed for reporting on evidence-based interventions.

Strengths and limitations

The FIPP makes an important contribution to the literature by providing researchers and practitioners with a foundation for reporting on intervention fidelity of delivery. By offering a structured and consensus-based approach to reporting on fidelity of delivery, the FIPP contributes to more rigorous implementation research and supports the development of more replicable and effective interventions. Rigorous evidence and clear reporting on fidelity are essential for enabling replication of interventions in new settings and supporting evidence synthesis efforts. The FIPP guideline enhances this process by providing more detailed and specific guidance on fidelity reporting than existing implementation outcome reporting guidelines [Reference Lengnick-Hall, Gerke and Proctor45]. This level of precision is especially important, given the potential influence of fidelity on intervention participant outcomes. An additional strength to this consensus-based process was the inclusion of academic and practice level professionals to inform the FIPP’s development.

While the FIPP provides a valuable contribution to implementation science and fidelity evaluation, this study has several limitations that are critical to acknowledge. The study had a small, non-random sample [Reference Khodyakov, Grant, Kroger and Bauman25]. As only a small group of interested panelists participated, it is possible key perspectives could be missing from the FIPP. As a result, it is encouraged that researchers and practitioners with feedback about the FIPP reach out and work alongside the co-authors of this paper to improve the FIPP. For instance, we believe it is important that the fidelity community continue to revise and add to the items listed in the FIPP guideline. However, it is important to note that our study sample size is not unlike other published studies of reporting guidelines (e.g., a reporting guideline created by Gagnier and colleagues [Reference Gagnier, Kienle, Altman, Moher, Sox and Riley46] had 27 participants). Further, a systematic review of 244 reporting guideline papers found that most reporting guidelines are not developed based on Delphi methods, with only 25% using a Delphi approach [Reference Banno, Tsujimoto and Kataoka47]. Additionally, the modified Delphi approach used in this study has several limitations, including using a three-point Likert scale in our online survey, only using one round of consensus meetings per group, and consulting implementation science experts online only [Reference Khodyakov, Grant, Kroger and Bauman25]. While this study and the resulting FIPP reporting guideline focus specifically on fidelity of delivery – just one component of overall fidelity – future work could build on this foundation to develop comprehensive reporting standards that address all dimensions of fidelity. Expansion across all dimensions of fidelity may promote more complete and consistent fidelity assessment across divers interventions.

Conclusion and next steps

This study and the resulting FIPP reporting guideline aimed to advance the science and practice of fidelity of delivery reporting in psychosocial and behavioral interventions. By providing structured guidance on how fidelity of delivery should be reported, the FIPP contributes to greater rigor and transparency in implementation science. It is our hope that researchers and interventionists globally will adopt the FIPP to strengthen the quality of fidelity reporting, thereby, improving our understanding of interventions and ultimately enhance participant outcomes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2025.10219.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of researchers and practitioners around the world who provided their knowledge and insights to shape the version of the FIPP shared in this manuscript.

Author contributions

Mackenzie Martin: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Mason Moser: Methodology, Project administration, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing; Alicia C. Bunger: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; E.B. Caron: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Mary Dozier: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Jamie Lachman: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Joanne Nicholson: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Marija Raleva: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Rachel C. Shelton: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Yulia Shenderovich: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Kirsty Sprange: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Elaine Toomey: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing; Susan M. Breitenstein: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing.

Funding statement

MM’s contribution to this study was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship. YS’s contribution supported by DECIPHer, which is funded by Welsh Government through Health and Care Research Wales. YS is supported by Wolfson Centre for Young People’s Mental Health, established with support from the Wolfson Foundation.

Competing interests

None.