Introduction

In the last decades, Euroscepticism has become increasingly visible among both the political elites and citizens (Verney Reference Verney2015). Its study has flourished to explore the proliferation of anti-European values, the content of political communication during electoral campaigns, or the effect of various crises on public support for the European Union (EU) (Leruth et al. Reference Leruth, Startin and Usherwood2017; de Vries Reference Vries and Catherine2018). Euroscepticism has been studied in relation to internal and external crises. Internally, the legitimacy crisis triggered by the 2016 referendum that resulted in the UK leaving the EU, fuelled discussions about potential similar approaches in other member states. For example, the radical-right in France mentioned this possibility in case of a victory in the legislative elections. The Hungarian and Polish governments referred to the possibility to leave due to issues of sovereignty and conflicts about the rule of law (Cisłak et al. Reference Cisłak, Pyrczak, Mikiewicz and Cichocka2020). Externally, previous research investigated how the global financial or the refugee crises influenced Euroscepticism (Magalhães Reference Magalhães2017; Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld, Schaper, de Lange and van der Brug2018) and found mixed results. Studies also looked at how the recent global health crisis (COVID-19) had an impact on the political support for national institutions. However, we know little about the effects of the pandemic on the Eurosceptic attitudes of citizens. Understanding these effects is important because of its unprecedented magnitude in the history of the EU: it involved life-threatening conditions for large segments of the population and the limitation of rights and freedoms for everyone.

Our article fills this gap in the literature and aims to identify the effect of people’s attitudes towards the EU’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic on the belief that their country has a better future outside the EU. This belief is an exemplary case of disruptive dissensus, as conceptualized in the introduction of this special issue, and a strong version of Euroscepticism as illustrated in previous studies (Gherghina and Tap Reference Gherghina and Tap2023). Our analysis covers all 27 EU Member States and uses individual-level data from the Standard Eurobarometer 95, which collected survey data on probability representative samples at national level in June-July 2021, and country-level data collected by the authors between the beginning of the pandemic and the end of May 2021. We run a multi-level statistical analysis that accounts for two individual variables (perception about how the EU handled the pandemic and trust in how it will handle it in the future) and four country-level characteristics: percentage of deaths due to COVID-19 in the population, lockdown duration, percentage of vaccinated people and presence of populists in government. The empirical analysis controls for several explanations that have been associated in the literature with support for the EU: dissatisfaction with democracy in the EU and in the country, limited information, and the common socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age and education).

We bring two important contributions to the literature. First, we illustrate how much the public connects the recent crisis of COVID-19 with their attitudes towards the EU. This informs about how congruent their attitudes are with the Eurosceptic discourses of some political elites in many member states. We provide evidence about how the public reacts to the EU institutional and policy responses to the pandemic (Quaglia and Verdun Reference Quaglia and Verdun2023). Second, this study complements earlier research that assessed people’s attitudes towards the responses provided by the national governments during the pandemic (Jørgensen et al. Reference Jørgensen, Bor, Lindholt and Petersen2021; Erhardt et al. Reference Erhardt, Freitag and Filsinger2023). We provide insights about the attitudes developed by the public towards the EU resulting from its perceived handling of the pandemic.

The next section reviews the literature about the relationship between external crises and EU exit. We formulate two hypotheses related to the potential effects of crises. The third section presents the data and methods used to test empirically the hypotheses. The fourth section presents an overview of the EU’s measures during COVID-19 and citizens’ desire to exit from the EU. Next, we present the results of our analysis and interpret the results in relation to the existing literature. The conclusions summarize the key findings and discuss their implications for the broader field of study.

COVID-19 and EU Exit

We argue that COVID-19 could have a negative influence on EU legitimacy and credibility in the eyes of the public for three main reasons: people may associate the unpopular measures with the EU, preferences for institutions in proximity to address crises, and a spillover effect at EU level of pandemic management at national level.

First, some unpopular measures taken by the national governments in the member states to address the COVID-19 pandemic and contain the spread of the virus (Lynggaard et al. Reference Lynggaard, Jensen and Kluth2022) could be associated, by the population, with the EU. This is in line with earlier evidence according to which Euroscepticism is rooted in domestic political crises and attitudes redeveloped in relation to those crises (Real-Dato and Sojka 2020). In general, national governments shift the blame for their failures through fuzzy national structures. This happens because the government often gets punished, i.e. lower public support, for events beyond their control such as external crises that negatively affect the population (Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009; Foster and Frieden Reference Foster and Frieden2017; Margalit Reference Margalit2019).

During the pandemic, some governments used blame diffusion strategies that spilled out of the political system when the fuzzy national structures were no longer sufficient to absorb it (Hinterleitner et al. Reference Hinterleitner, Honegger and Sager2023). This could especially happen since, in some countries, the anger induced by COVID-19 determined some respondents to view democratic regimes with less sympathy (Erhardt et al. Reference Erhardt, Freitag and Filsinger2023). The spilling out may be at the EU, which could have been blamed by some segments of the population, for example, for pushing the member states to speed up the vaccination rates (European Commission 2021) or the introduction of the EU digital COVID certificate as the main possibility to ensure freedom of movement. This blame attribution to the EU was effective in the political discourse of the political leaders in several countries. These did not create new Eurosceptic narratives but consolidated and adapted the existing narratives to the pandemic context (Hloušek and Havlík 2023).

Second, people prefer institutions in their proximity to handle external crises. During COVID-19, the measures used to manage the pandemic involved a trade-off between civil liberties and public health, which could be accepted more easily if decisions are taken nationally because domestic political institutions are closer to citizens and they know their own needs. There is evidence about a strong preference of people for national as opposed to European responses to the pandemic, which is considerably stronger for the COVID-19 than for other crises (Amat et al. 2020). This preference has been reflected in the growing trust in national political institutions during the pandemic in many countries (Bol et al. Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021; Esaiasson et al. Reference Esaiasson, Sohlberg, Ghersetti and Johansson2021). Both the lockdown measures and the intensity of the pandemic rallied people around national institutions (Schraff Reference Schraff2021). These results indicate that people appear to be more lenient and understanding towards the actions of national institutions during the pandemic than towards the more distant–from both geographic and accountability perspectives–EU institutions.

Third, there were instances in which countries dealt poorly with the pandemic. In their case, the existing Eurosceptic attitudes could have been strengthened or expanded in the wake of COVID-19 effects. More precisely, the regions with sharper divides between Eurosceptics and EU-supporters among politicians faced problems agreeing on anti-pandemic measures and the excess deaths have been significantly higher (Charron et al. Reference Charron, Lapuente and Rodríguez-Pose2023). This could mean that the people who were Eurosceptic before the pandemic maintained their negative view towards the EU, while those who were neutral or even EU-supporters could have been disheartened about the absence of an EU response to improve the situation in their country.

Following all these arguments, we expect that dissatisfaction with the measures that the EU took against COVID-19 (H1) and low trust in its ability to make the right choices about the pandemic in the future (H2) are likely to result in disruptive dissensus regarding the future in the EU, i.e. preferences for exit. These causal mechanisms rely on the established association between the specific and diffuse support (Hetherington Reference Hetherington1998). Our expectations gauge both retrospective and prospective attitudes because we seek to understand whether the sources of people’s preferences are rooted in the EU’s past performance or it is an ongoing concern.

Controls

Our analysis controls for several common sources of Euroscepticism at the individual level. The first is the category of dissatisfied democrats that can have two points of reference: the EU and their country. To start with the EU, one of the frequent critiques is its democratic deficit according to which it is an elite-like supranational structure with limited electoral and popular accountability, inability to represent the will of member state citizens, and with opaque practices in the decision-making processes (Vollaard 2018). There is a positive relationship between satisfaction with national democracy and satisfaction with EU democracy. This relationship can be due to the inclusion of national governments in the EU decision-making process or to the fact that people have limited information about what happens at the European level. As such, people can use their attitudes towards the national political system as a proxy for their opinions about democracy in the EU (Hobolt Reference Hobolt2012).

The second control is the limited information about the EU. Limited knowledge about the EU can lead to an uninformed and sceptic public towards the EU (Galpin and Trenz 2017). The limited information generates a vicious circle in which the people perceive distance between themselves and the EU because they do not know much about it, and they have little incentive to learn about it since it is distant. The third control is political efficacy because those citizens who feel their voice is represented in the EU may be more likely support it (Mcevoy Reference Mcevoy2016). The fourth control is the ideological placement of citizens: previous research indicates that sometimes the right-wing reject European integration (van Elsas, Hakhverdian, and van der Brug Reference Elsas, Erika, Hakhverdian and van der Brug2016) and other times this rejection can be found among left-wing oriented individuals (Wagner Reference Wagner2022). We control for age, education and gender because earlier studies show that these can influence Euroscepticism (Hakhverdian et al. Reference Hakhverdian, van Elsas, van der Brug and Kuhn2013; Díaz-Lanchas et al. Reference Díaz-Lanchas, Sojka and Di Pietro2021).Footnote 1

We also control for several variables at the country level. We expect that a higher percentage of deaths due to COVID-19 in the population, higher lockdown duration, and lower vaccination percentage in the country to favour peoples’ Euroscepticism. These variables reflect the severity of the pandemic, the anti-pandemic measures and citizens’ exposure to them (Lynggaard et al. Reference Lynggaard, Jensen and Kluth2022). Previous research on crises have shown that the severity of crises can have an impact on people’s attitudes towards the EU (Di Mauro and Memoli Reference Mauro, Danilo and Memoli2016; Magalhães Reference Magalhães2017). Also, the presence of populists in government may have a positive effect on this type of disruptive dissensus since populist parties display various types of Euroscepticism (Pirro and Taggart Reference Pirro and Taggart2018).

Anti-pandemic measures and EU exits

This section provides an overview of the EU measures during the pandemic and a brief discussion about the rhetoric about EU exit in several member states. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU adopted several measures that had been implemented by all the member states. Most measures were temporary restrictions on non-essential travel, providing COVID vaccines and creating the EU vaccination certificate (European Council 2020). Even though the EU took the initiative to propose a set of measures against COVID-19, most of the national political leaders took measures to protect their citizens long before the EU published the set of recommendations. For example, many EU member states decided individually to close their borders in March 2020 as a reaction to the virus (Pool 2024).

In general, these leaders focused on addressing the pandemic and adapting to the particular trajectories of its development in their countries rather than engaging with the EU measures. For example, several governments used scientific evidence and experts’ advice to address the pandemic and responded quite promptly. The containment measures were adopted in the early phases of the pandemic while response uncertainty was still high in countries relying on scientific knowledge (Lynggaard et al. Reference Lynggaard, Jensen and Kluth2022).

Compared to the member states, the EU used a step-by-step approach in fighting the pandemic outbreak. It focused on four major points: limiting the spread of the virus; supporting jobs, businesses and the economy; promoting research for treatments and vaccines; and ensuring the provisional equipment (Council of the European Union 2023). The coordinated response came after all member states had declared multiple coronavirus cases within their countries.

The EU tried to limit the spread of the virus by allocating funds for research. The main objective in research was to develop reliable tests that could detect the virus in a couple of minutes, but also to develop vaccines against the virus (Council of the European Union 2021). Apart from investing in research, the EU has also facilitated the medical support between countries creating corridors to send medical equipment and teams of doctors and nurses from one country to another (Council of the European Union 2021). The coronavirus pandemic has affected countries’ economies, but the EU has created a few schemes to decrease the impact of the pandemic on economies and to help member states to recover. One of the main schemes created by the EU is “Next Generation EU”, its main purpose being to help countries and businesses recover, but also to empower a better prepared EU in case of other crises. This fund could also be used for projects aimed to support the green and digital transitions (Council of the European Union 2024). Another instrument created by the EU was for temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE). This instrument acted as a loan for member states to support the existing jobs for a short-time (Council of the European Union 2022).

Rhetoric about EU exit in several member states

Brexit has changed the main idea revolving around the EU enlargement and integration. The latter has been often seen in the last decades as a one-way street and the Euro-optimists expected this to be only a matter of time before the European map was printed in reflex blue (Gastinger Reference Gastinger2021). This changed in 2016 when the UK voted to leave the EU, indicating that an exit is possible. This idea was picked up by the political elites of several member states and used in their discourse. Previous research has investigated the likelihood of potential EU exits: Austria, Czech Republic, and Sweden appeared as strong candidates for such an option, followed by Denmark, Greece, Cyprus, France, and Italy (Gastinger Reference Gastinger2021). These findings are confirmed for Eastern European countries where the Czech Republic is by far the closest to a potential exit compared to the other member states in the region (Gherghina and Tap Reference Gherghina and Tap2023).

After Brexit, Italy was considered one of the candidates for an exit. Almost half of the population was inclined to back their nation’s exit from the EU if the UK and its economy would be in a good shape in five years after Brexit (Walsh 2020). The emerging Italexit party, which promised to liberate Italy “from the cage of the European Union and the single currency” (AlJazeera 2020) was modelled after Nigel Farage’s UK-based Brexit Party and aspired to a comparable level of popularity. Since two influential political parties in the coalition government, the right-populist League and the left-populist Five Star Movement, supported Italexit as a solution to the country's economic and social problems (including immigration), the possibility of Italy leaving the EU was a real possibility (Fingleton Reference Fingleton2019). The effects would have been complicated because, in addition to higher trade barriers between Italy and the rest of the EU, there would also be exchange rate differences in the case of a Eurozone exit (Fingleton Reference Fingleton2019).

The day after making it to the second round of the 2017 French presidential election, Marine Le Pen campaigned in Burgundy. "I do not want to leave the EU (…) that is not my goal” (The Guardian 2022). However, much of what the leader of the far-right National Rally wants to achieve—regarding the economy, social policy, and immigration—requires breaking the EU's regulations. In the 2022 presidential elections, her specific policy suggestions are in direct conflict with the obligations of EU membership. The policy has been dubbed "Frexit in all but name" by critics and commentators (The Guardian 2022). The idea of "Czexit" has been mentioned several times by the far-right and populist parties. However, this is unlikely to happen since the country is a net beneficiary of subsidies from Brussels and there are currently no mechanisms in place to stage a referendum (Hutt 2021).

Research design

We empirically test these effects with the help of individual-level data from the Standard Eurobarometer 95, which conducted the surveys in June-July 2021 in all 27 member states. We chose May 2021 because until then most of the countries had lifted the lockdowns or had relaxed almost completely the restrictions (Lynggaard et al. Reference Lynggaard, Jensen and Kluth2022). One of the main reasons for this decision was that vaccines were available. Also, starting with 1 July 2021, the EU Digital COVID Certificate has been put in use to facilitate people’s movement and the reopening of borders between countries (European Commission 2023). The country-level data were collected from the beginning of the pandemic until May 2021, while the individual level comes from the survey conducted among the citizens of the EU member states after the May 2021 moment, i.e. Eurobarometer 95.

The survey sampling is multi-stage and probabilistic, which is based on a random selection of sampling points after stratification by the distribution of the national, resident population according to their area of residence, proportional to the population density and size relative to the total coverage of the country. The sampling includes random use of addresses, route procedures, selection from the household or from electoral registers (GESIS Eurobarometer Data Service 2023). The country samples are usually around 1,000 respondents, but some samples are roughly half of that due to the country size (Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta). The samples range between 502 in Malta to 1,525 respondents in Germany, the latter being initially divided between East and West.

The dependent variable is the strong version of Euroscepticism related to the preference to exit the EU. To measure this variable, we use the extent to which the respondents agreed with the statement that their country has a better future outside the EU. The available answers range between “totally disagree” and “totally agree”, measured on a four-point ordinal scale. We measure satisfaction with the measures that the EU took against COVID-19 (H1) through the answer provided to the question about the individuals’ satisfaction with the measures taken against COVID-19 by the EU. The answers were recorded on a four-point ordinal scale coded ascendingly between “not at all” and “very much”. The trust in the EU’s ability to make the right choices about the pandemic in the future (H2) was measured with the help of the answers given to a question with this exact wording. The available answers range between “do not trust at all” and “totally trust”, coded on a four-point scale.

The first two control variables are measured through the answers provided to the questions about how satisfied the respondents are with democracy in the EU and in the country. Both are measured on a three-point ordinal scale: “not very satisfied”, “fairly satisfied” and “very satisfied”. To measure the knowledge about the EU we use a cumulative index that includes three items related to the number of countries in the Euro area, the direct election of the EP members, and whether Switzerland is a EU member state. The correct answers were coded 1, while the incorrect and “do not know” answers were coded 0. In general, we excluded the “do not know / no answer” options from the analysis, but in this particular case related to knowledge about the EU the “do not know” option has meaning–if people used that option, it is equivalent to having an incorrect answer to the question. The respondent’s ideological position is the answer to the common question about left–right self-placement on the 10-point ordinal scale (1 is left and 10 is right). Age is measured on a six-point scale that ranges between the “15–24 years” category and the “over 65 years” category. Education is also an ordinal variable that gauges the level of education from primary to postgraduate education, with specific labels in each country. Gender is a dichotomous variable that is coded 1 for men and 2 for women.

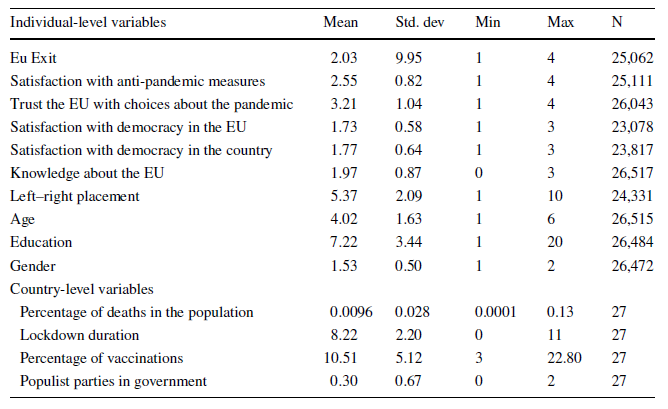

The variables at the country level are measured as follows. The percentage of deaths due to COVID-19 in the population is calculated using the number of deaths reported by the member states until June 2021, which is the moment of the data collection for the Eurobarometer survey. This number and information about the population size was double checked with information from Worldometer (2021).The lockdown duration is measured as the total number of months cumulated from all lockdown phases in each country (Lynggaard et al. Reference Lynggaard, Jensen and Kluth2022). The percentage of vaccination in the country is based on the information included in official country reports until 31 May 2021. The presence of populists in government is coded as 0 for absence, 1 for populist parties as minor coalition partners and 2 for populists as major coalition partners (at the end of May 2021). The descriptive statistics are available in Appendix 1.

Method and reverse causality

Methodologically, we rely on multi-level ordinary logistic regression models to test the effects of dissatisfaction with how the EU addressed the pandemic and trust in its ability to handle it in the future on Euroscepticism. There is evidence of clustering. The chi square test for the LR test vs logistic model has a value of 1239.58 and it is statistically significant, which gives support for the use of a multi-level as opposed to a single level model. The model that contains the randomly varying intercepts fits significantly better than a single level where the intercepts are not randomly varying. However, the value of the estimated intraclass correlation coefficient is at the lower limit of the conventional threshold that indicates substantial clustering (0.05). We also checked for multicollinearity for the individual-level data (first level of our analysis) and there are no reasons for concern. The highest value of the correlation coefficient between the independent and control variables is 0.48.

The issue of reverse causality is possible from a theoretical perspective and, in this case, quite probable: the negative attitudes towards the EU could drive citizens to assess its efforts towards the pandemic as being poor. In the absence of panel data, we cannot exclude completely the idea of reverse causality, but we can show empirically that it is more probable to have the pandemic efforts (cause) before the disruptive dissensus in the EU (effects). We checked the aggregate preferences for a future outside the EU at country level in November 2018 (Eurobarometer 90.3) and November–December 2019 (Eurobarometer 92.3), both before the COVID-19 pandemic. In these surveys the general percentage in favour of leaving the EU is somewhat higher than in the 2021 survey used in our analysis. More important, in 17 member states the percentage of people favouring the disruptive dissensus is higher or considerably higher during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the periods before. For example, Sweden was one of the countries with the lowest desire to exit the EU in 2018 (19.5%) but increased in 2021 to almost 36%. To use another example, Lithuania had a relatively low level of dissensus in 2018 and 2019 (21% or 22%) and this increased to roughly 30% in 2021. These ascending trends indicate that reverse causality is less likely than the direction hypothesized in our article.

Analysis and results

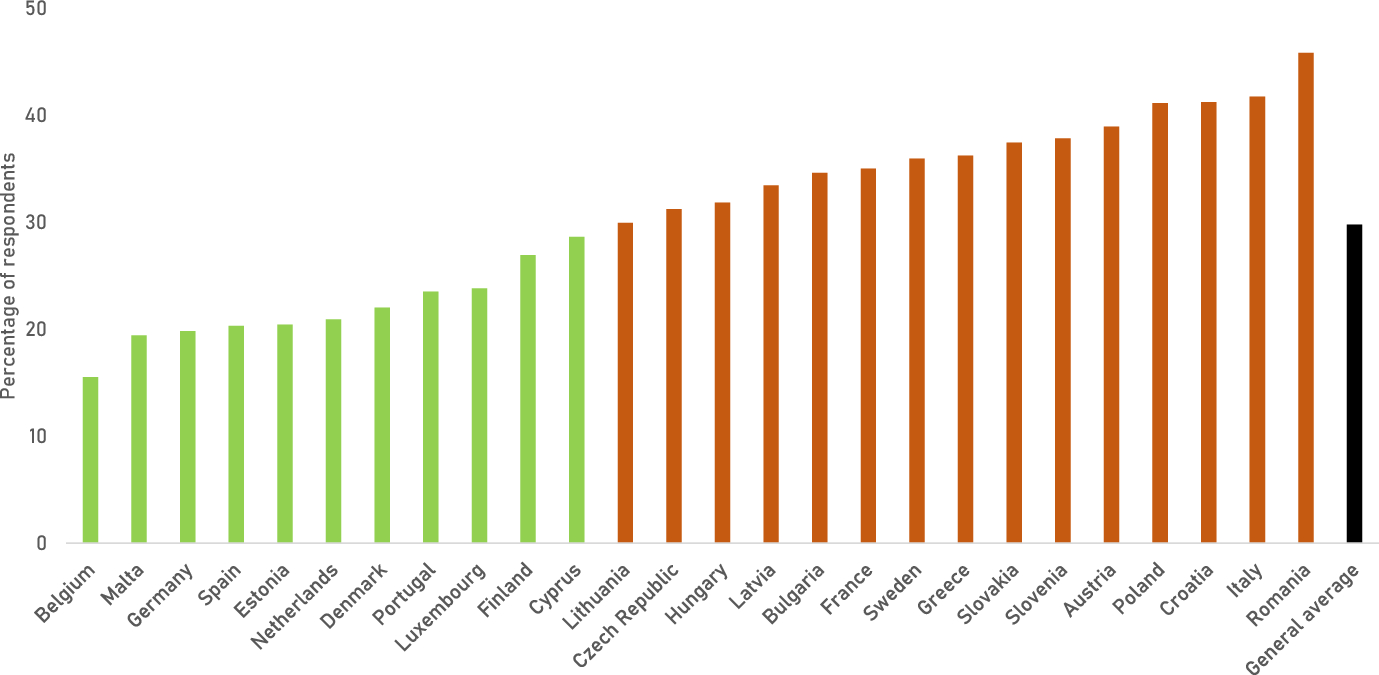

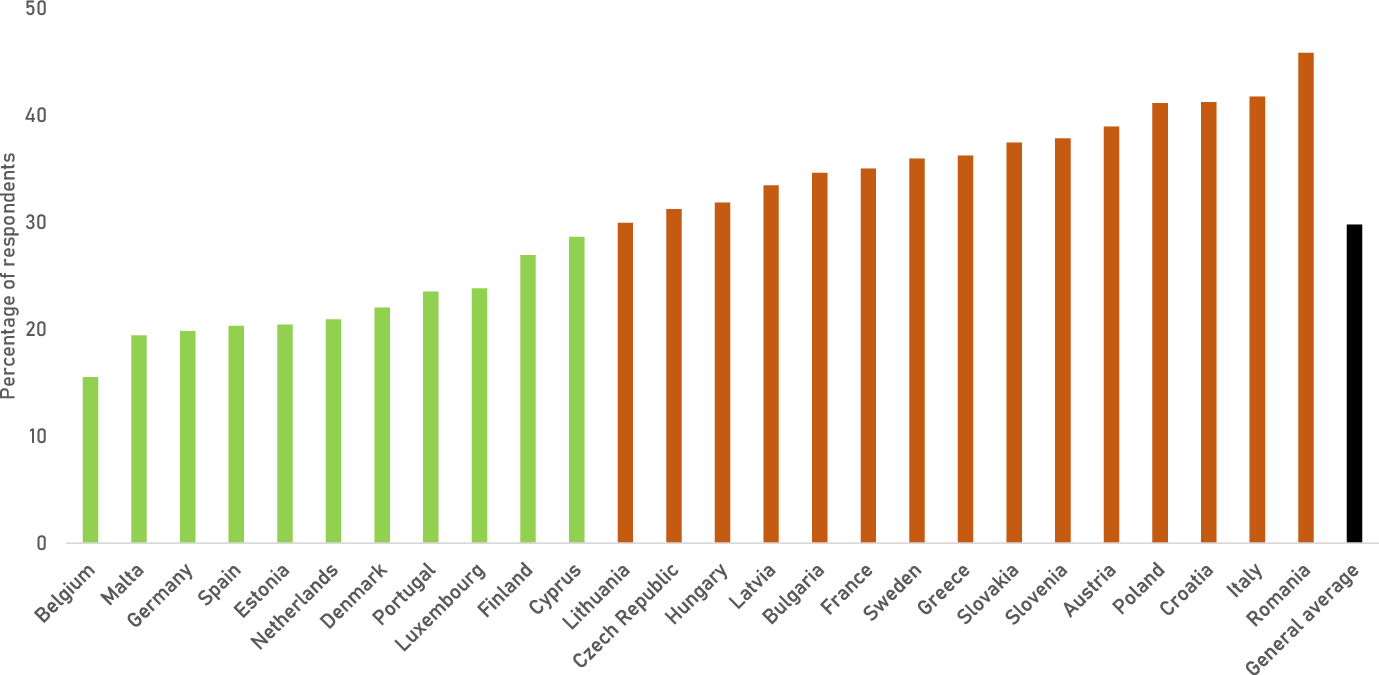

Figure 1 depicts the distribution of Eurosceptic respondents in the 27 member states. The bars are the cumulated percentages of those respondents in each country who indicate that they tend to agree and totally agree with the statement that their country has a better future outside the EU. The average percentage of Eurosceptic citizens in all the EU member states is almost 30%. The green bars correspond to the countries that have lower percentages than this average, while the red bars are for countries above the average. Most of the recent member states, with accession in 2004, 2007 and 2013, are in the group of countries with higher levels of Euroscepticism. The presence of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland in that group confirms their ongoing criticism against the EU in the last decade. The presence of countries such as Croatia or Latvia may be surprising since both are net beneficiaries of the EU subsidies and their governments have often been supporters of integration. The positioning of Romania as the member state with the highest number of Eurosceptics is also surprising since its population has been among the champions of Euro-optimism for many years. This percentage can reflect the episodes of democratic backsliding in 2012–2013 and 2017–2018 in which the political elites in government promoted an anti-EU rhetoric (Gherghina and Soare Reference Gherghina and Soare2016; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Reference Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier2020). In spite of this, the Romanian politicians or political parties have never referred explicitly to a potential exit.

Fig. 1 The distribution of Eurosceptic respondents in the member states

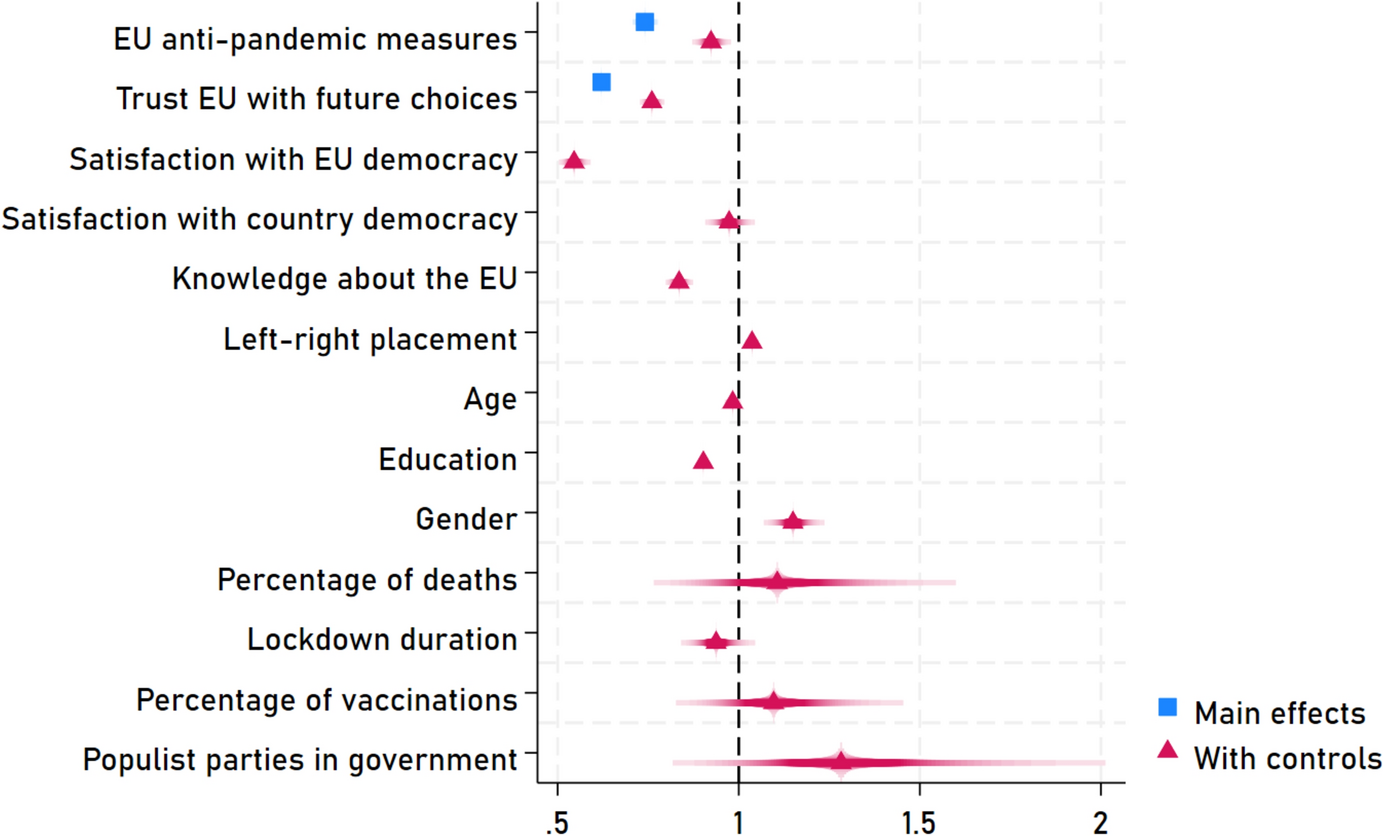

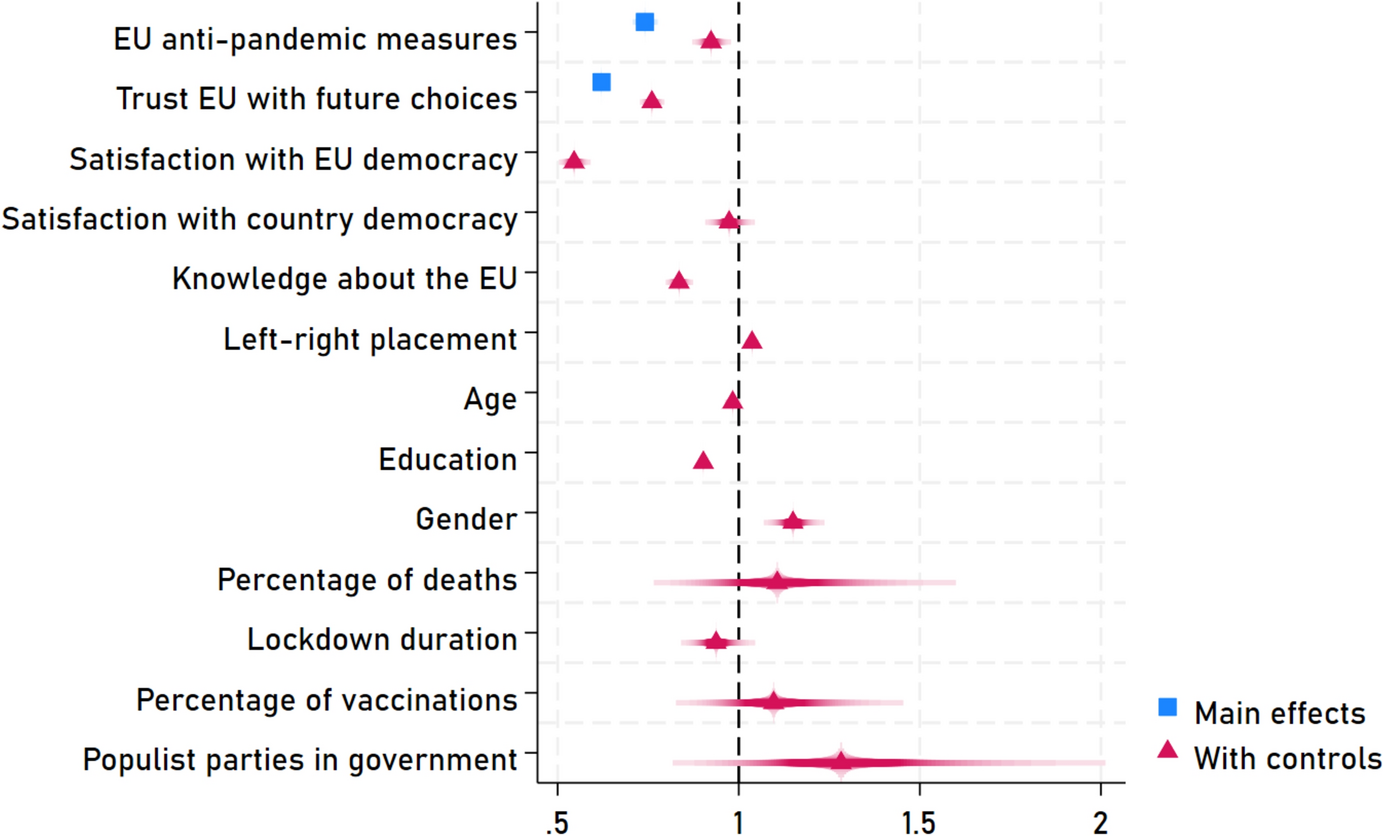

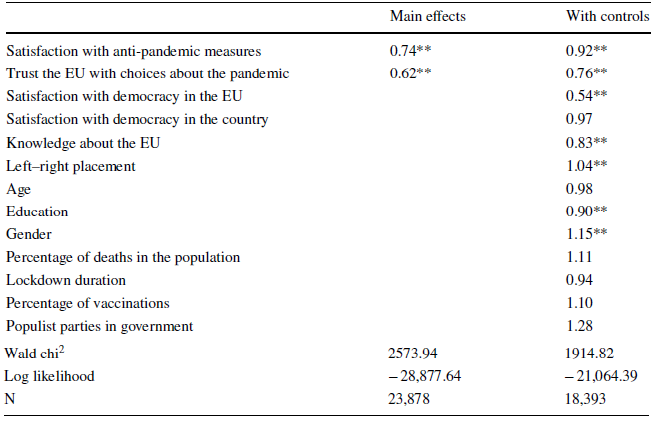

Figure 2 includes the results of the multi-level ordinal logistic regression analysis. We ran two models—one with the main effects and another with controls (for full model specifications, see Appendix 2). The model with the main effects shows strong empirical support for the theoretical expectations: those individuals who are dissatisfied with the anti-pandemic measures in the EU (H1) and those who do not trust the EU’s choices about the pandemic in the future (H2) are more Eurosceptic compared to the respondents who are satisfied and trust the EU. The prospective assessment–the trust in future decisions–has a stronger impact. These results advance the state of the art about dissensus and Euroscepticism in two directions.

Fig. 2 The effects on Euroscepticism at individual level

First, we complement the existing literature according to which Euroscepticism is rooted in domestic political crises (Real-Dato and Sojka 2020). We show that how, at least in an extreme form, Euroscepticism is rooted in international crises and in the ways the EU handles them. It is less important whether this is due to blame diffusion (Hinterleitner et al. Reference Hinterleitner, Honegger and Sager2023) or to the preference that people have for national institutions in their proximity to address the crises (Amat et al. 2020). Instead, the European citizens may consider the EU directly responsible for crisis handling and their assessments are based on its actions. It is a sign of accountability. This could mean that those individuals who were Eurosceptic before the pandemic found confirmatory evidence for their attitudes. Those people with neutral views, or even once Euro-optimists, could become critical towards the EU’s perceived failure to address the crisis.

Second, we add nuances to the literature about popular support for political institutions in times of crises. The mixed evidence regarding the popular support for national political institutions during the pandemic (Bol et al. Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021; Esaiasson et al. Reference Esaiasson, Sohlberg, Ghersetti and Johansson2021; Rieger and Wang Reference Rieger and Wang2022) is partially due to different causes for support. In the case of the EU, we show that the extreme Eurosceptic attitudes of roughly 30% of the European citizens are driven by similar causes across the member states.

The model with the control variables tells a similar story about the hypothesized effects: they are statistically significant, but the effect size is smaller than in the previous model. Only some of the individual-level controls are statistically significant. The dissatisfaction with democracy in the EU has a strong effect on Euroscepticism, confirming earlier findings. The less knowledgeable citizens about the EU appear to be more Eurosceptic, which nuances findings from two decades ago, according to which people with higher levels of information formed opinions about the EU based on the assessment of institutions (Karp et al. Reference Karp, Banducci and Bowler2003). There is a weak probability that lower educated respondents and women are likely to be more Eurosceptic. The findings about education are in line with previous results (Hakhverdian et al. Reference Hakhverdian, van Elsas, van der Brug and Kuhn2013). There is a very small effect of right-wing respondents being in favour of EU exit. This size of effect can be a confirmation that Eurosceptic attitudes are visible at both extremes of the political spectrum (de Vries and Edwards Reference Vries, Catherine and Edwards2009).

None of the country-level controls has a statistically significant effect on the disruptive dissensus. The severity of the pandemic, reflected in the percentage of deaths, lockdown duration or percentage of vaccinations, does not appear to matter. A sizeable effect is observable for the variables related to populists. Respondents from countries with populist parties in government have a higher probability to prefer EU exit, which is consistent with the general arguments in the literature about the Eurosceptic messages of populist parties.

Conclusions

This study aimed to identify the effect of people’s attitudes towards the EU’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic on a strong form of Euroscepticism, i.e. the belief that their country has a better future outside the EU. This disruptive dissensus is embraced by less than one third of European citizens, which illustrates that the radical Eurosceptic discourses of several national political leaders reach limited audiences. We find that the negative attitude about how the EU handled the pandemic and low trust in how it would handle it in the future favour EU exit. These effects hold when controlling for several variables that usually impact the Eurosceptic attitudes, including the severity of the pandemic or the presence of populists in government.

These results add to a growing literature about the relationship between political support during the COVID-19 pandemic (Devine et al. Reference Devine, Gaskell, Jennings and Stoker2021; Belchior and Teixeira Reference Belchior and Teixeira2023; Schraff Reference Schraff2021) and nuance previous findings about the EU support. We show that disruptive dissensus is linked to specific forms of dissatisfaction about the EU’s approaches towards the pandemic. These forms are strong because the individuals faced existential challenges during the pandemic, i.e. they felt severe threats to their lives. This made individual-level attitudes matter across members states, which explains why the country-level variables about the pandemic intensity are irrelevant in explaining the dissensus. However, this specific dissatisfaction is likely to be short-lived because the memory of the pandemic will fade in the future. We also illustrate that the EU policy initiatives during the pandemic have definitely not broken the link between specific and diffuse support, which holds during crises. Our analysis finds that longer-lasting forms of diffuse support, such as the satisfaction with how democracy works in the EU, are a strong predictor for the EU exit. This means that even if the EU has low efficiency and effectiveness in addressing crises, this will not have a great influence on the dissensus. The correlation between the specific and diffuse criticism against the EU is lower than 0.4 among our respondents. Moreover, the public attitudes towards the EU are associated more with EU-level actions rather than derived from domestic processes. For example, the dissatisfaction with how democracy works in the country makes no difference. We contribute to the literature about people’s attitudes towards the responses provided by the national governments during the pandemic (Bol et al. Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2021; Erhardt et al. Reference Erhardt, Freitag and Filsinger2023) by illustrating that the assessment is more nuanced at transnational level.

Our findings open a new perspective on the explanation of disruptive dissensus or extreme forms of Euroscepticism in the pandemic context. We provide insights into the importance of both retrospective and prospective actions, and of a combination between specific and diffuse critiques. Further research could build on the results and test the effect of cultural, psychological or socio-economic determinants as alternative explanations for strong Eurosceptic attitudes. These would allow exploring a broader range of potential drivers and would help in refining the causal mechanisms. These could be also tested on clusters of member states.

Appendix

Appendix 1: Descriptive statistics of the variables included in the analysis

Appendix 2: The multi-level ordinal logistic regression

The reported coefficients are odds-ratio. **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.