Introduction

Public legitimacy as the public's belief that it is ‘rightful and proper’ to accept the political regime and abide by its rules (Easton, Reference Easton1975) is an important requirement for effective government in liberal democracies, which have to rely mainly on voluntary compliance with collective decisions instead of the use of force. Against this background we ask a straightforward and practice-relevant question: What kind of decisions do policy makers have to take on a day-to-day basis to strengthen citizens' legitimacy beliefs?

A diverse body of literature in political science argues that citizens' attitudes towards political systems are largely determined by whether the political decisions produced by the system serve citizens in the realization of their personal preferences (egotropic representation). This line of thought ranges from systems theory focussing on the role of outputs or performance of a system for political support (Easton, Reference Easton1965, Reference Easton1975), over work that shows that citizens who are ‘winners’ in the democratic process and get their preferences represented are more supportive of democracy and its institutions (e.g., Anderson & Guillory, Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016, Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017; Ezrow & Xezonakis, Reference Ezrow and Xezonakis2011; Mayne & Hakhverdian, Reference Mayne and Hakhverdian2017), to the notion of ‘stealth democracy’, according to which citizens are not interested in political participation but are satisfied as long as they get their preferences (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002).

Here, we argue that when forming legitimacy beliefs about political decisions, citizens may not only care about their personal preferences (i.e., whether a decision is favoured by themselves), but also about whether the collective preferences of the majority of citizens are realized (sociotropic representation). While sociotropic concerns about the collective are prominent in many fields in political science (e.g., economic voting or preferences for redistribution), only a few studies have addressed them specifically with regard to legitimacy beliefs in political decisions (e.g., Arnesen et al., Reference Arnesen, Broderstad, Johannesson and Linde2019; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017). We advance on these studies by exogenously varying cues about whether the majority of citizens support a political decision or oppose it, whereas previous studies either did not provide a cue about majority preferences or focussed on decisions that were all supported by majorities. Varying cues about majority support is important: While democratic procedures are often justified on the grounds that they ‘automatically’ create legitimacy beliefs by channelling the preferences of the majority into policy outputs, decisions in representative democracies – in which representatives and not citizens take decisions – may not always follow majority preferences.

We focus on the European Union (EU) as a case for which many analysts have claimed that a failure to represent majority preferences in political decisions is the root cause of recurrent crises of public legitimacy the EU system experiences (e.g., Føllesdal & Hix, Reference Føllesdal and Hix2006; Hix, Reference Hix2008; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999). While much of the empirical literature on EU attitudes has focussed on support for EU membership as a broad, general measure of legitimacy (see Hobolt & de Vries, Reference Hobolt and de Vries2016), no empirical work has addressed legitimacy beliefs in specific, concrete EU decisions. This is surprising given that the extant theoretical literature assumes that the ‘inputs’ and ‘throughputs’ that lead to EU decisions, as well as the quality of these decisions as ‘outputs’, strongly influence the EU's legitimacy (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2013).

Theoretically, we conjecture three mechanisms that could increase citizens' legitimacy beliefs in response to sociotropic representation, even in cases where the majority's preference is in conflict with personal preferences. First, citizens may view majority endorsement of a policy as a persuasive cue for its legitimacy in cases where they identify with this majority as a group (group endorsement) (e.g., Lupia, Reference Lupia1994). Second, citizens may unreservedly take majority opinion as a cue because they assume that it is the ‘good’, ‘valid’ or ‘intelligent’ opinion, which should be represented (consensus heuristic) (e.g., Axsom et al., Reference Axsom, Chaiken and Yates1987; Mutz, Reference Mutz1998). Third, citizens who can expect to belong to the majority on many political issues may value the principle of majority representation, for it is in their long-term interest (long-term utilitarian calculus) (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Moehler & Lindberg, Reference Moehler and Lindberg2009).

Empirically, we design a novel single-profile vignette survey experiment, in which citizens rate fictitious, political decisions at the EU level on a legitimacy dimension. The decisions vary by whether they are in line with respondents' personal opinion on an issue, national and EU-wide majority opinion, as well as procedural parameters during EU-level decision making (e.g., size of majorities in the decision-making bodies). This experimental design provides us with a more convincing causal identification than related work studying the effect of representation on various attitudes towards the political system using observational data (e.g., Anderson & Guillory, Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Ezrow & Xezonakis, Reference Ezrow and Xezonakis2011; Mayne & Hakhverdian, Reference Mayne and Hakhverdian2017).

Moreover, our design also advances on the recently growing survey-experimental literature measuring the impact of representation on legitimacy as decision acceptance (e.g., Arnesen, Reference Arnesen2017; Arnesen & Peters, Reference Arnesen and Peters2018; Arnesen et al., Reference Arnesen, Broderstad, Johannesson and Linde2019; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016, Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017). While many existing studies focus on decisions by hypothetical decision-making bodies in single issue areas or taken by special procedures (e.g., referendums), our design emulates political decisions as they occur day-to-day in an actual representative democracy (the EU), marginalizing over a set of ten different policies from five substantive issue areas. This improves the ecological validity of our findings.

Results from

![]() $n = 20,880$ vignette ratings, obtained from representative samples of citizens in five EU countries, show that legitimacy beliefs are primarily driven by whether a decision is congruent with personal opinion. However, even if a decision is incongruent with personal opinion, legitimacy beliefs are stronger if this decision was taken in line with either EU-wide or national majority opinion. Subgroup analyses show that, in particular, citizens with weak issue attitudes react to the representation of majority opinion. This suggests that the effect mainly runs through the consensus heuristic mechanism, whereby respondents identify majority opinion as an opinion of special validity that should be represented. In contrast to our results on representation, procedural parameters within the EU's policy-making process only have a very limited influence on legitimacy beliefs.

$n = 20,880$ vignette ratings, obtained from representative samples of citizens in five EU countries, show that legitimacy beliefs are primarily driven by whether a decision is congruent with personal opinion. However, even if a decision is incongruent with personal opinion, legitimacy beliefs are stronger if this decision was taken in line with either EU-wide or national majority opinion. Subgroup analyses show that, in particular, citizens with weak issue attitudes react to the representation of majority opinion. This suggests that the effect mainly runs through the consensus heuristic mechanism, whereby respondents identify majority opinion as an opinion of special validity that should be represented. In contrast to our results on representation, procedural parameters within the EU's policy-making process only have a very limited influence on legitimacy beliefs.

Our results therefore support calls for stronger majority representation in EU policy making as one potential means to strengthen the EU's legitimacy (e.g., Hix, Reference Hix2008), and illustrate how democratic procedures, more generally, create public legitimacy through fostering majority representation.

Public legitimacy and its determinants

Democratic systems are in need of support by the public to survive in the long run. This support can take on various forms. Most famously, Easton's system-theoretical account delineates diffuse and specific support (Easton, Reference Easton1975). While specific support relates to citizens' evaluations of current political decisions, policies or actions, diffuse support relates to ‘a reservoir of favorable attitudes or good will that helps members to accept or tolerate outputs to which they are opposed or the effects of which they see as damaging to their wants’ (Easton, Reference Easton1965, p. 273). In this framework, public legitimacy is one form of diffuse support and refers to citizens' conviction that it is ‘rightful and proper’ to accept the political regime and abide by its rules (Easton, Reference Easton1965, Reference Easton1975; Gilley, Reference Gilley2006). It creates a baseline stability to the system, a ‘reservoir of support’ for a political system that enables institutions to take decisions (Tyler, Reference Tyler2006). Legitimacy means the regime's entitlement to control and to make political decisions, even if its subjects do not like the specific decision.

As part of diffuse system support, legitimacy ‘tends to be more durable’ (Easton, Reference Easton1975, p. 444). However, ‘over a long time period’ diffuse system support may change as ‘a product of spill-over effects from evaluations of a series of outputs and of performance’ (Easton, Reference Easton1975, p. 446). We therefore argue that it is important to consider citizens' evaluations of political decisions as primary outputs of political systems on a legitimacy dimension. If a series of decisions is favourably (unfavourably) evaluated in light of the legitimacy concept, then citizens might gain (or lose) belief in the system's rightful and proper exercise of power over them – at least in the long run. Each decision effectively serves as some test of whether citizens believe that the legitimacy of the system is embodied in this very decision.

Much work has shown that citizens' legitimacy perceptions of a decision greatly depend on whether the decision is in line with their personal preferences – often called ‘outcome favorability’ (e.g., Anderson & Guillory, Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Arnesen & Peters, Reference Arnesen and Peters2018; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016, Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017; Ezrow & Xezonakis, Reference Ezrow and Xezonakis2011; Mayne & Hakhverdian, Reference Mayne and Hakhverdian2017). Most importantly, using 28 vignette and field experiments Esaiasson et al. (Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016) consistently find that outcome favourability is the dominant determinant of decision acceptance, not only directly but also through an influence on procedural fairness perceptions that again shape citizens' decision acceptance. While we therefore know that citizens care about their personal preferences when forming legitimacy beliefs in decisions, some work has also investigated whether citizens value their own personal influence in decision making, including by participating in direct majority voting (e.g., Arnesen, Reference Arnesen2017; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2012; Persson et al., Reference Persson, Esaiasson and Gilljam2013). For instance, relying on field experiments, Esaiasson et al. (Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2012) find that personal involvement in a decision through direct voting consistently increases legitimacy beliefs. In contrast, using survey experiments, Arnesen (Reference Arnesen2017) finds little difference in legitimacy beliefs when varying the degree of personal influence, which may be due to weaker participant involvement in survey experiments, as opposed to field experiments.

While these studies still primarily focus on egotropic effects (e.g., whether personal preferences are fulfilled, or whether the respondent is personally involved in decision making), a limited amount of work has looked at genuinely sociotropic effects on legitimacy beliefs. Focussing on metropolitan governance and public transport, Strebel et al. (Reference Strebel, Kübler and Marcinkowski2018) show that citizens prefer decision-making bodies that use majority voting rather than unanimity, and implement a project at lower costs, which may be interpreted as a sociotropic concern for the common pool resource of public funds. However, this study does not elicit the legitimacy of decisions but primarily preferences for decision-making bodies (the dependent variable is a choice between two planning commissions). Esaiasson et al. (Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017) focus on the legitimacy of political decisions and show that when controlling for personal outcome favourability, adapting a decision towards respondents' perceived majority opinion of the public does not significantly increase legitimacy. However, a limitation of the study is that public opinion is not provided as an exogenously manipulated cue, but the authors ask respondents what they perceive to be the public's majority view. Finally, Arnesen et al. (Reference Arnesen, Broderstad, Johannesson and Linde2019) exogenously vary the size of a majority supporting or opposing EU membership of Norway in a referendum, and find that larger majority sizes increase the legitimacy belief in the referendum outcome. However, in their setting, the referendum outcome as a decision is – by definition – always supported by a majority and not a minority. There is no variation in whether the majority is represented; it always is.

We advance on these important works by considering how an exogenous cue about public opinion, as respondents will often receive in the real world (e.g., in media reports), influences legitimacy beliefs in political decisions that are taken through ‘standard’, representative procedures, and may therefore be in line or conflict with majority opinion. Moreover, we focus on the mechanisms by which representation of the majority may alter citizens' legitimacy beliefs. We also document egotropic and especially sociotropic effects on legitimacy beliefs across a unique set of five countries as well as several issue areas.

While our main focus is on majority representation, in particular, procedural aspects of decision making such as stakeholder/civil society involvement, transparency or voting rules are also prominent in the literature as determinants of legitimacy beliefs. While some studies find sizeable effects of procedures and even highlight that low-quality procedures can diminish the effects of egotropic representation (Bernauer et al., Reference Bernauer, Mohrenberg and Koubi2020; Dellmuth et al., Reference Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg2019; Strebel et al., Reference Strebel, Kübler and Marcinkowski2018), others find – on the contrary – that perceptions of the quality of procedures are largely endogenous to, constrained or even shaped by outcome favourability (Anderson & Guillory, Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Arnesen, Reference Arnesen2017; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016). This suggests that the evaluation of outcomes and procedures could be closely intertwined in the minds of voters. To avoid confounding, it is therefore important to also vary procedural aspects of decision making. We consider these procedures specifically for our case of the EU below.

Majority representation and legitimacy

A key aspect of political decisions that should influence their evaluation by citizens on the legitimacy dimension is whether the decisions are in line with the preferences of the majority of citizens. This is what we call ‘majority representation’.Footnote 1 The idea that democratic systems legitimize themselves by being responsive to majority preferences is prominent in majoritarian or median voter models of democracy (e.g., Dahl, Reference Dahl1971; Powell, Reference Powell2000). In fact, it seems plausible that if political decisions consistently defy the majority's preferences, legitimacy beliefs will necessarily decline among many citizens (e.g., in terms of Easton's ‘spill-over effects'). However, note that while we often associate majority representation to be a byproduct of democratic procedures, these are themselves not a necessary condition for legitimacy beliefs. Recent work has argued and shown that legitimacy beliefs can also emerge in autocracies (e.g., Gerschewski, Reference Gerschewski2018; Mauk, Reference Mauk2020).

How does the representation of majority preferences influence legitimacy beliefs in decisions? The first, obvious channel through which majority representation could increase legitimacy is by realizing personal preferences, as all citizens who belong to the majority should increase their legitimacy beliefs due to outcome favourability (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Anderson & Guillory, Reference Anderson and Guillory1997; Arnesen & Peters, Reference Arnesen and Peters2018; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017, Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016; Ezrow & Xezonakis, Reference Ezrow and Xezonakis2011; Mayne & Hakhverdian, Reference Mayne and Hakhverdian2017). In essence, effects of egotropic representation are aggregated. The most prominent theoretical mechanism that explains egotropic effects is based on a rational choice model of opinion formation, in which citizens form expectations about the benefits and costs of a policy for them. The more net utility a policy provides, the more favourable opinions citizens will develop towards the system that has produced this policy (utilitarian calculus). This mechanism has, for instance, been highlighted in the context of ‘winners-losers gaps’ in legitimacy attitudes (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005) as well as support for European integration (Gabel, Reference Gabel1998). We therefore expect the following:

Hypothesis 1 (Aggregation of Egotropic Effects): Legitimacy beliefs in a political decision will be stronger if the substance of the decision is in line with personal preferences.

We argue that in addition to this aggregation of egotropic effects, majority representation may also influence legitimacy through a second channel: Citizens may more genuinely care about whether a decision is congruent with the preference of the majority, irrespective of whether it is congruent with their personal preference. We contribute by formulating three mechanisms of why citizens, and even those that do not personally endorse a policy, might be willing to accept it more and consider it more legitimate if it realizes the collective preference.

First, citizens may increase their legitimacy belief in a decision that is in line with majority opinion, as they may rely on the majority's endorsement as a trusted source cue to substitute for a lack of information about the policy (e.g., Lupia, Reference Lupia1994; Lupia & McCubbins, Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998). The majority's endorsement serves as an information shortcut about potential aspects of the policy citizens may not know themselves. Essential for this mechanism is the persuasiveness of the source cue. In our case, where the source is the majority of citizens in a political entity (i.e., a group), identification with this group should be key for the cue's persuasiveness. For instance, only if citizens identify with the nation, they should rely on the opinion of co-nationals and increase their legitimacy beliefs in decisions endorsed by a majority of – say – Germans, Italians or French. In the U.S. context it has been demonstrated that citizens regularly form opinions about policies on the basis of group endorsements (Arceneaux & Kolodny, Reference Arceneaux and Kolodny2009; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). In the literature on support for EU integration, scholars have highlighted the importance of citizens’ identification with the nation (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). Here, we bring both strands of thinking together and consider that citizens may rely on endorsements that come from ‘the nation itself’, in the form of majority opinion. We call this mechanism group endorsement.

Second, citizens may view a decision as more legitimate if the majority of the public supports this decision, because they feel the majority choice is the ‘good’, ‘valid’ or even ‘intelligent’ choice; that is, the majority has some special ability to identify and support legitimate policies.Footnote 2 In the social psychology literature, this type of cognitive schema has been termed as consensus heuristic and found to apply most strongly to citizens with weak involvement on an issue, who use majority endorsement as a cue to form their own opinion (in our case, their legitimacy belief) in absence of accessible and univalent own attitudes (Axsom et al., Reference Axsom, Chaiken and Yates1987). In the political science context, Mutz (Reference Mutz1998) has provided some evidence that citizens apply a consensus heuristic when forming political evaluations of unknown candidates, but we have little evidence for the relevance of the consensus heuristic mechanism in other political situations. In contrast to group endorsement, the consensus heuristic mechanism does not depend on identification with a group but stipulates that the majority cue is persuasive per se, especially for individuals with weak involvement on an issue, who simply ‘jump on the bandwagon’ of the majority's assessment.Footnote 3

Third, citizens who tend to hold the majority's preferences on many political issues (e.g., political moderates) may support the principle of majority representation out of long-term utilitarian considerations. They may have learned that although they may not share the majority's opinion on every issue, sociotropic representation is beneficial for them on average, over a large set of issues. Hence, they may view decisions as more legitimate if they realize majority preferences. Similar lines of thought are prominent in the literature on the alternation of winning and losing in democratic elections (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005; Moehler & Lindberg, Reference Moehler and Lindberg2009). We call this mechanism long-term utilitarian calculus. In any case, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 2 (Sociotropic Effects): Legitimacy beliefs in a political decision will be stronger if the substance of the decision is in line with the preferences of the majority of citizens.

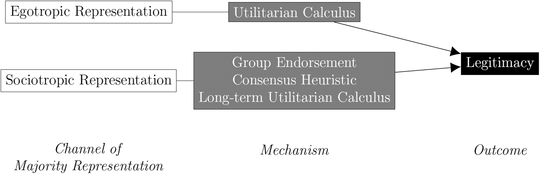

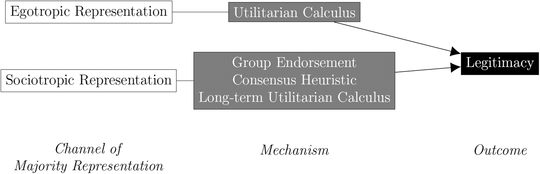

Figure 1 summarizes our theoretical expectations with regard to the egotropic and sociotropic effects of majority representation on legitimacy beliefs.

Figure 1. Theoretical model of the impact of majority representation.

The case of the EU

There are few cases of democratic political systems whose legitimacy has been as frequently discussed among policy makers, the public and academics alike as the EU's (e.g., Beetham & Lord, Reference Beetham and Lord1998; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999). It is therefore important to ascertain what measures could strengthen EU legitimacy. However, given high constitutional hurdles for institutional change (e.g., the agreement of 27 national governments and parliaments), we focus on what policy makers could practically do in day-to-day decision making within the EU's current institutional structure. Theoretical work has argued that the EU's legitimacy is strongly shaped by how and what kind of political decisions the EU takes (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2013). Specifically, much work distinguishes the quality of decision-making inputs (e.g., opportunities for citizen/stakeholder participation), throughputs (e.g., inclusiveness of decision making) and outputs (e.g., representation, delivering people's preferences).

The role of majority representation as an output factor takes central stage in the academic debate. While some argue that the EU should be considered (more) legitimate in the eyes of experts as well as citizens if its policies were supported by majorities across the EU or in many member states, they disagree about whether EU policies actually realize majority representation (Føllesdal & Hix, Reference Føllesdal and Hix2006; Hix, Reference Hix2008; Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik2002). Others, however, fundamentally question the theoretical premise that majority representation will always enhance public (or ‘social') legitimacy in the EU case. They point to the conundrum that there are effectively numerous different majorities across the EU – at least, different national ones in the member states and an EU-wide one. While citizens may consider policies more legitimate that are supported by a national majority, they may not be receptive to the views of the EU-wide majority, especially when national and EU-wide majorities diverge. In Joseph Weiler's words, an early advocate of this view, the EU may lack the ‘social fabric […] that the electorate accepts the new boundary of the polity and […] the legitimacy - in its social dimension - of being subjected to majority rule in a much larger system comprised of the integrated polities’ (Weiler, Reference Weiler1991, p. 2472). In terms of our theoretical mechanisms (see above), this view suggests that most citizens may only, or at least primarily, rely on national majority opinion as a trusted source cue, while neglecting EU-wide majority opinion.

Several other literatures on EU-related public opinion, not directly concerned with the legitimacy of EU decisions, suggest that large groups of the electorate, with different forms of Eurosceptic predispositions, may not be swayed by EU-wide majority opinion. First, the fact that national versus European identity strongly constrains broad support for European integration could be read as an indication that many citizens will not rely on the majority of fellow EU citizens when evaluating EU policies (e.g., Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). Second, the apparent lack of public support for European solidarity in redistributive policy areas (e.g., bailouts during the eurozone crisis) points to the possibility that many citizens (esp. those with weak cosmopolitan values) do not view the EU as the legitimate polity, but only their own national state (e.g., Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014). Third, we know that citizens who are negatively predisposed towards the integration project are also biased in their attribution of blame to the EU (Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014). Arguably, for such groups it is even conceivable that they may interpret EU-wide majority support for a policy as a signal of illegitimacy. All this suggests that the influence of EU-wide majority representation on legitimacy beliefs may be limited and mostly run through the group endorsement mechanism for those that identify strongly with the ‘new’ polity that is the EU.

Regrettably, we have very little quantitative empirical evidence on whether different forms of majority representation affect citizens’ legitimacy beliefs in EU decisions. The few existing studies usually only focus on egotropic and not sociotropic representation, and they also use subjective measurements of citizens' self-perceived quality of representation (e.g., asking respondents whether the EU takes decisions in their interest), which may well be endogenous to preexisting legitimacy beliefs (Ehin, Reference Ehin2008; Rohrschneider, Reference Rohrschneider2002). Our main interest is therefore in experimentally identifying the effect of majority representation on legitimacy beliefs in EU decisions. Following our discussion above, we analytically consider congruence of a policy with national majority opinion as well as with EU-wide majority opinion.

In addition to our focus on representation on the output side, we also consider one prominent input and one prominent throughput factor that vary in EU day-to-day decision making and could influence legitimacy beliefs. This provides us with benchmarks to which we can compare the effects of representation (e.g., their substantive magnitude) and makes the identification of these effects more credible as we effectively control for confounders (e.g., if citizens draw inferences about these factors from receiving information about representation). It also ensures that we present realistic EU decisions to our respondents that vary on more than two characteristics, as decisions vary on multiple aspects in reality and citizens may learn about multiple aspects in mass communications about these decisions (see Online Appendix A). First, with regard to input, the European Commission (henceforth, ‘the Commission'), which prepares all legislative proposals, can opt for more or less stakeholder participation by choosing to hold public consultations on issues. In these consultations, not only individuals and interest groups but also public bodies can submit their views on draft legislative initiatives. The Commission then may or may not incorporate this feedback in its legislative proposal. Public consultations are the Commission's major institutionalized instrument that aims at increasing legitimacy through wider participation (Lindgren & Persson, Reference Lindgren and Persson2010).

Second, in the ‘throughput’ realm, the inclusiveness of legislative decision-making in the Council of the EU and the European Parliament (EP) may vary. Some have argued that taking decisions in consensus in the Council can act as a signal to domestic audiences that negotiations were conducted fairly, leaving only ‘winners’ around the table, which should strengthen legitimacy perceptions (Heisenberg, Reference Heisenberg2005, pp. 81–84). While in current practice, decision making in the Council is mostly consensual, with only about 1–2 per cent of votes given by governments in opposition to decisions, the degree of inclusiveness could definitely vary within the existing institutional rules. Reh (Reference Reh2012), among others, has argued more generally that ‘inclusive compromises’ in the EU, that is, negotiation outcomes characterized by generous concessions and broad-based support among actors, foster legitimacy perceptions by signalling nondomination, empathic concern and perspective-taking. Following this line of thought, we also consider the level of inclusive decision making in the EP, where decisions can be taken with narrow versus broad-based support.

Survey-experimental design

We are interested in how majority representation, as well as the procedural factors described above, affect perceptions of the legitimacy of EU decisions. In observational studies, it is hard to isolate the influence of a specific factor on attitudes of political support, as a multitude of diverse political decisions that occurred in reality may have influenced individuals. To tackle this, we design a single-profile vignette survey experiment that grants us full control to randomly vary different aspects of EU decisions and elicit respondents’ evaluations of single decisions. Our design presents respondents with a paragraph that describes a single political decision, which is defined by different attributes and related levels, which we draw fully randomly and independently of each other, creating a whole ‘universe’ of decisions. This allows us to estimate the causal effect of an attribute level, marginalizing over the distribution of all other attribute levels.

In recent years, vignette and conjoint survey experiments have been used extensively in political science to study citizens' attitudes and preferences (e.g., Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). Dellmuth (Reference Dellmuth, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018) stresses the potential of survey experiments for studying legitimacy beliefs. Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto2015) have shown that different forms of vignette and conjoint experiments produce revealed preferences that converge to behavioural benchmarks. Most importantly, as survey experiments vary choices on multiple dimensions, they provide respondents with multiple reasons to justify their response, which reduces social desirability bias (e.g., Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014, p. 3). This is a key advantage for our purpose, as respondents may hold priors about the socially desirable response on a normatively charged issue like legitimacy. To further increase ecological validity, our vignette design presents simplified information about EU decision making as conveyed in mass communications (e.g., limited procedural details); presents single decisions instead of pairs, as decisions usually occur individually in reality; and draws decisions from five important issue areas covering a broad range of the EU's activities.

Setup and vignettes

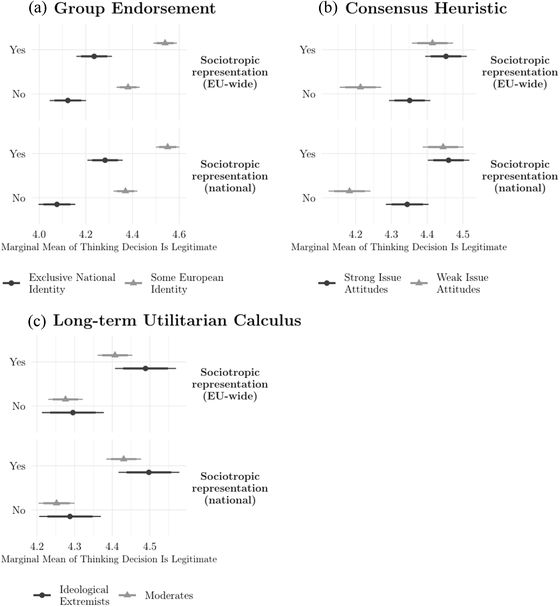

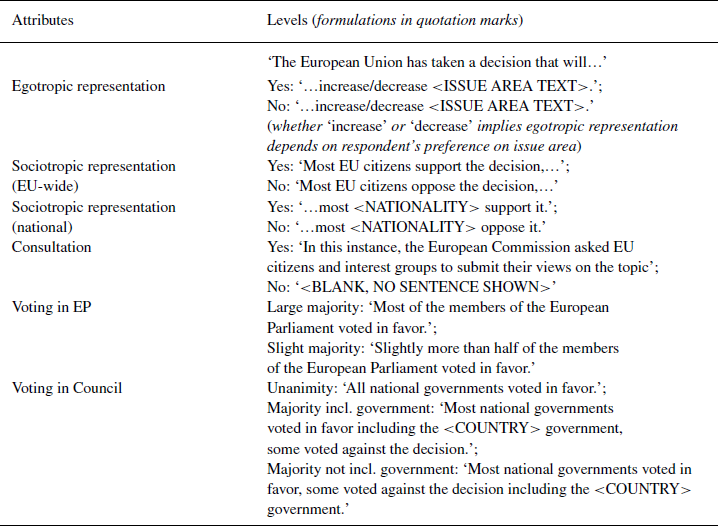

Our stimulus material are short text vignettes that describe a political decision taken by the EU.Footnote 4 While we briefed respondents that all decisions were fictitious, we instructed them to imagine that the decision had been taken and report how they would react to it. An overview of the attributes and levels of the vignettes is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Design of vignettes

Note:

![]() $<$ISSUE AREA TEXT>

$<$ISSUE AREA TEXT>

![]() $\longrightarrow$ environmental protection = ‘environmental protection at the cost of more [with the benefit of less] regulation for businesses’; consumer protection = ‘consumer protection at the cost of more [with the benefit of less] bureaucracy for businesses’; financial support = ‘financial support for weak economies, creating [reducing] costs for economically stronger member states’; military cooperation = ‘military cooperation between member states’; reallocation of refugees = ‘the reallocation of refugees between member states’.

$\longrightarrow$ environmental protection = ‘environmental protection at the cost of more [with the benefit of less] regulation for businesses’; consumer protection = ‘consumer protection at the cost of more [with the benefit of less] bureaucracy for businesses’; financial support = ‘financial support for weak economies, creating [reducing] costs for economically stronger member states’; military cooperation = ‘military cooperation between member states’; reallocation of refugees = ‘the reallocation of refugees between member states’.

The attributes of the vignettes were selected so as to test our theoretical expectations from above. First, to test Hypothesis 1 and exogenously vary egotropic representation, we randomly draw our decisions from five issue areas (with replacement), where in each area a decision can go in two opposing substantive directions (e.g., increase vs. decrease environmental protection). Including multiple issue areas is important given recent evidence that survey-experimental effects of text-based treatments can greatly vary by issue (Blumenau & Lauderdale, Reference Blumenau and Lauderdale2020). We therefore also assess the robustness of our findings across issues (see Online Appendix I.2). Our areas are: environmental protection, consumer protection, military cooperation, financial support for member states with struggling economies and refugee reallocation. These areas cover a wide range of salient EU activity, including ‘high’ (e.g., military cooperation) versus ‘low’ (e.g., consumer protection) politics issues as well as regulatory (e.g., environmental protection) versus redistributive (e.g., financial support) policies. The vignettes randomly presented respondents with a decision on either side of the issue (see

![]() $<$ISSUE AREA TEXT> in Table 1). As we surveyed respondents’ policy preferences on each issue area prior to the experiment (see Online Appendix E), we know whether each drawn decision is in line with respondents’ personal preference. For instance, we ask respondents pretreatment whether they want to ‘increase’ or ‘decrease military cooperation between member states’. We then randomly draw a decision that either increases or decreases military cooperation. Randomization ensures that for half of the decisions presented, egotropic representation is realized, while it is absent for the other half.

$<$ISSUE AREA TEXT> in Table 1). As we surveyed respondents’ policy preferences on each issue area prior to the experiment (see Online Appendix E), we know whether each drawn decision is in line with respondents’ personal preference. For instance, we ask respondents pretreatment whether they want to ‘increase’ or ‘decrease military cooperation between member states’. We then randomly draw a decision that either increases or decreases military cooperation. Randomization ensures that for half of the decisions presented, egotropic representation is realized, while it is absent for the other half.

Second, to test Hypothesis 2, we vary sociotropic representation by providing respondents with a cue about whether the majority of the public across the EU as well as the majority in their country supports or opposes the EU's decision. Specifically, our vignettes state that ‘Most EU citizens [support/oppose] the decision, most [

![]() $<$NATIONALITY>] [support/oppose] it’. Given that figures of public support for specific policies are highly dependent on question wording, and given citizens’ knowledge of public opinion is limited, we assume that our treatments of majority preference are plausible albeit randomization. Third, regarding input in the form of stakeholder involvement, we randomly either state that interest groups and the public were consulted before the decision was taken or do not mention the consultation phase at all. Fourth, to provide information on the throughput stage, we vary the inclusiveness of decision making in the relevant legislative bodies: either most or only slightly more than half of the members in the EP voted in favour of the decision, and support by national governments in the Council varies between either unanimity, support including the respondent's own government or support not including the respondent's own government.

$<$NATIONALITY>] [support/oppose] it’. Given that figures of public support for specific policies are highly dependent on question wording, and given citizens’ knowledge of public opinion is limited, we assume that our treatments of majority preference are plausible albeit randomization. Third, regarding input in the form of stakeholder involvement, we randomly either state that interest groups and the public were consulted before the decision was taken or do not mention the consultation phase at all. Fourth, to provide information on the throughput stage, we vary the inclusiveness of decision making in the relevant legislative bodies: either most or only slightly more than half of the members in the EP voted in favour of the decision, and support by national governments in the Council varies between either unanimity, support including the respondent's own government or support not including the respondent's own government.

We formulated the levels of our attributes with a view to how citizens would learn about these aspects of EU decision making in real-world mass communications (e.g., through television media). For instance, as Commission consultations are entirely optional, media would likely only mention them if they took place but not find it news-worthy that no consultation was held. We reflect this by leaving the attribute blank in half of the cases. Detailed justifications for the attribute levels are in Online Appendix A. One randomly drawn example of a vignette is:

“The European Union has taken a decision that will increase environmental protection at the cost of more regulation for businesses. Most EU citizens support the decision, most

![]() $<$NATIONALITY> support it. In this instance, the European Commission asked EU citizens and interest groups to submit their views on the topic. Slightly more than half of the members of the European Parliament voted in favor. All national governments voted in favor.”

$<$NATIONALITY> support it. In this instance, the European Commission asked EU citizens and interest groups to submit their views on the topic. Slightly more than half of the members of the European Parliament voted in favor. All national governments voted in favor.”

After reading the vignette, respondents were asked to rate each decision on two legitimacy scales. The literature has used different approaches of measuring respondents’ legitimacy beliefs. In a pretest, we validated the question items used in this study against other operationalizations found in the literature (details are in Online Appendix B). First, some studies use perceptions of procedural fairness to operationalize legitimacy (e.g., De Fine Licht et al., Reference De Fine Licht, Naurin, Esaiasson and Gilljam2014; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016; Persson et al., Reference Persson, Esaiasson and Gilljam2013), drawing on findings by Tyler (Reference Tyler2006), who describes fairness as psychologically closely connected to legitimacy. However, such works often focus on small-scale decision making in groups, lacking institutional political context. While this promises important insights for our understanding of legitimacy in general, we argue that questions about procedural fairness do not sufficiently tap into the acceptance of the right to rule, which is central to legitimacy in our specific case. Citizens may think that it is ‘rightful and proper’ that a political system has taken a particular decision, although they do not believe this decision is fair.

Second, some studies use formulations that stress the right of an institution to take a decision directly and unilaterally (Levi et al., Reference Levi, Sacks and Tyler2009; Scherer & Curry, Reference Scherer and Curry2010). We decided against such questions (e.g., ‘the EU should have the right to take this decision’) because our pretest showed that they correlate highly with items measuring support for EU integration (e.g., support for EU membership and trust in the EU), which are more about the allocation of competences and surrendering sovereignty than about acknowledging the EU's right to rule. Third, some studies focus on decision acceptance as a measurement of legitimacy, as it is connected fairly closely to accepting the right to rule of a political system (e.g., Arnesen & Peters, Reference Arnesen and Peters2018; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016; Scherer & Curry, Reference Scherer and Curry2010). We adopt this way of surveying legitimacy and follow closely the operationalization proposed by Arnesen and Peters (Reference Arnesen and Peters2018). In addition, we also adopt a fourth approach that directly asks respondents how ‘legitimate’ the decision is from their perspective. Gangl (Reference Gangl2003) and Neuner (Reference Neuner2018) have suggested that, notwithstanding the complexity of the concept, asking for legitimacy directly may be preferable to asking for more pliable concepts (e.g., ‘acceptance’) that are not legitimacy precisely. Our two legitimacy items that respondents answer for each presented decision are:

Legitimacy Q1: ‘On a scale from 1 to 7, how legitimate do you think this decision is?’

-

• Scale from 1 (‘not at all legitimate’) to 7 (‘very legitimate’)

Legitimacy Q2: ‘On a scale from 1 to 7, how willing are you to accept this decision?’

-

• Scale from 1 (‘not at all willing’) to 7 (‘very willing’)

The two questions provide different angles to the respondent: While in Q1 she is asked to judge the decision in the abstract, Q2 asks for an act(ion) (‘accept’). The two questions are rather short, simple to understand and translate easily into the five languages used for the survey (see below). Our analyses show that the two measures correlate at

![]() $r = 0.84$ and substantively all results hold for either dependent variable (for differences in the interpretation of the outcomes, see Online Appendix L). In the ‘Results’ section, we present all analyses using the legitimacy operationalization (Q1). Results for the acceptance operationalization (Q2) can be found in Online Appendix K.

$r = 0.84$ and substantively all results hold for either dependent variable (for differences in the interpretation of the outcomes, see Online Appendix L). In the ‘Results’ section, we present all analyses using the legitimacy operationalization (Q1). Results for the acceptance operationalization (Q2) can be found in Online Appendix K.

Sample

We fielded our experimental design in five EU member states, namely, France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain in autumn 2018. This selection of countries achieves diversity on important aggregate-level covariates that could influence our experimental effects. First, Germany, Poland and Spain have particularly low levels of public Euroscepticism, while Italy and to a lesser extent France have higher levels (see Figure D2 in the Online Appendix). Second, Emmanuel Macron's LREM, the German grand coalition, and the Spanish PSOE government are all pro-EU governments by partisan ideology, whereas the Italian and Polish administrations are key examples of governments lead by populist, anti-EU parties. Hence, our country sample allows us to assess the robustness of individual-level effects to different aggregate-level predispositions towards the EU as well as varying elite environments. In addition, our sample consists of the five largest member states by population, which allows us to draw inferences about the attitudes of the majority of the EU's population.

The multinational survey was conducted online by Dalia Research with a fieldwork period from 30 November 2018 to 13 December 2018. Dalia Research sources survey respondents through thousands of websites and apps. Quotas were defined for sex, age (three groups) and education (four groups) to be nationally representative for the 18–65 years voting-eligible population in each country. The target samples for each country encompassed

![]() $\ge 800$ respondents, resulting in a total of 4,176 completed interviews. Respondents rated five vignettes each, providing us with

$\ge 800$ respondents, resulting in a total of 4,176 completed interviews. Respondents rated five vignettes each, providing us with

![]() $n = 20,880$ rated EU decisions. Besides the experiment and questions on respondents’ policy preferences regarding the five issue areas covered by the experiment, we also asked several demographic questions, as well as questions about membership in the EU, political identity, left-right self-placement and past voting behaviour. The quality of our sample is highlighted by the fact that the distributions of several key variables in our sample highly converge to distributions of these variables in recent Eurobarometer surveys (see Online Appendix D for details). Online Appendix N contains the English source questionnaire as well as the translated questionnaires.

$n = 20,880$ rated EU decisions. Besides the experiment and questions on respondents’ policy preferences regarding the five issue areas covered by the experiment, we also asked several demographic questions, as well as questions about membership in the EU, political identity, left-right self-placement and past voting behaviour. The quality of our sample is highlighted by the fact that the distributions of several key variables in our sample highly converge to distributions of these variables in recent Eurobarometer surveys (see Online Appendix D for details). Online Appendix N contains the English source questionnaire as well as the translated questionnaires.

Results

We follow recent advice by Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020), who argue that the analysis of stated preference experiments through average marginal component effects (AMCEs), as suggested by Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014), can be misleading because the interpretation of AMCEs is dependent on which attribute levels are chosen as the baseline for comparison. AMCEs can be especially misleading when comparing subgroup preferences, as they do not allow direct statements about absolute but only relative preferences (in comparison to the baseline category). Since we use subgroup analyses in several instances below, we adopt Leeper et al.'s (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020) approach and analyse marginal means (MMs) instead of AMCEs using the ‘cregg’ package in R (Leeper, Reference Leeper2020). Importantly, in fully randomized designs, AMCEs are nothing other than differences in MMs (between two attribute levels). Hence, while focussing on MMs may safeguard against certain inferential errors, it is not a fundamentally different approach from analyses using AMCEs.Footnote 5 Below we present pooled results from all

![]() $n = 20,880$ vignette ratings from all five countries with respondent-level cluster-robust standard errors.

$n = 20,880$ vignette ratings from all five countries with respondent-level cluster-robust standard errors.

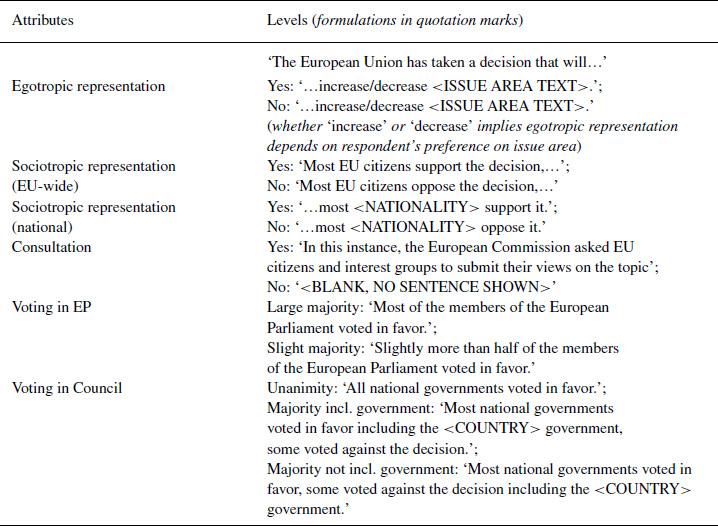

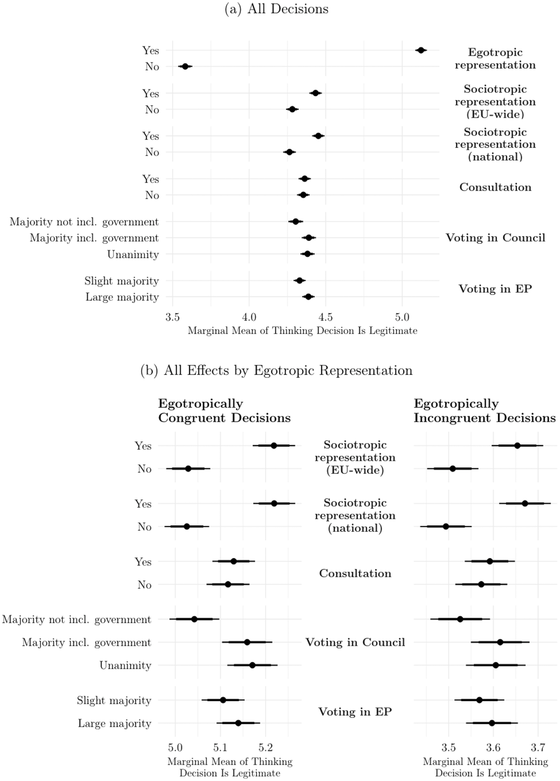

Figure 2(a) shows the main results of the MM analysis.Footnote 6 The horizontal lines denote 95 per cent as well as 84 per centFootnote 7 confidence intervals in all figures below. Most obviously, egotropic representation, the congruence between the decision and the respondent's own preference, has a very strong effect on thinking a decision is legitimate. On our scale from 1 to 7, the effect is 1.54, or 0.87 standard deviations on the dependent variable. This is evidence for Hypothesis 1 and supports the general assumption in the field that legitimacy beliefs are strongly shaped by egotropic representation.

Figure 2. Marginal means of perceived legitimacy.

Notes: Marginal means with thin 95 per cent and thick 84 per cent confidence intervals; outcome is on 1 (‘not at all legitimate’) to 7 (‘very legitimate’) scale.

But most importantly, we also find an effect of sociotropic representation, the congruence between the decision and majority opinion. If the decision is supported by either national or EU-wide public opinion, legitimacy beliefs are significantly stronger than if the majority opposes the decision. Against a baseline of opposing national and EU-wide majority opinion, positive opinion on both levels leads to an increase in legitimacy evaluations of 0.35 points or 0.20 standard deviations. When public opinion differs between the national and the EU level, the effect is split in about half. This is clear evidence for Hypothesis 2 that the realization of the preferences of the majority of citizens is relevant for legitimacy beliefs. In addition, the effects of sociotropic representation are not constrained by egotropic representation. The panels in Figure 2(b) plot MMs by egotropic representation separately: The left-hand panel only uses decisions that were egotropically congruent, that is, the policy change was in line with a respondent's preference, whereas the right-hand panel uses those decisions that were egotropically incongruent, went against a respondent's personal preferences. The patterns of MMs and experimental effects are almost indistinguishable from each other, no matter whether a decision is in line with personal preference.Footnote 8 In Online Appendix J we show that actually none of the effects of any attributes significantly vary by egotropic representation. Even if citizens personally dislike the substance of a decision (right-hand panel), they still more strongly believe in its legitimacy when majority preferences are realized. Hence, citizens care about majority representation independently of their own personal representation.

Meanwhile, whether the Commission decided to consult interest groups and the public in the decision does not have a significant effect on perceiving the decision as legitimate. Voting in the Council does have an effect, but only if the respondent's own government has voted against the decision, leading to a more negative evaluation of the legitimacy of the decision. However, this effect is rather small with −0.11 points on the scale or 0.06 standard deviations. Voting behaviour in the EP does not influence legitimacy perceptions, although the MM for decisions that most MEPs approved is slightly larger than that for less inclusively taken decisions, but the difference is not statistically significant. These results suggest some positive effect of the inclusiveness of decision making on legitimacy beliefs, but the size of these effects is rather small.

Robustness checks reveal that the effects of egotropic and sociotropic representation apply widely. A first concern pertains to the role of predispositions towards the EU. Individuals with Eurosceptic predispositions may react less to both forms of representation than individuals with Europhile predispositions, as they may view any decision by the EU as illegitimate. In Online Appendix I.1, we perform subgroup analyses by support for EU membership and voting intention for Eurosceptic and/or populist parties. They reveal clearly that egotropic and sociotropic representation sway the legitimacy beliefs of individuals irrespective of their predispositions on the EU. Second, in Online Appendix I.2 we also demonstrate that the egotropic and sociotropic representation effects are not only very similar across countries and issue areas but also statistically significant in each country and for each issue area.

Mechanisms of sociotropic representation

Which mechanism presented above explains the effects of sociotropic representation? First, we consider the group endorsement mechanism. Our experiment provides limited information about the political decision taken by the EU, which could make respondents rely on majority endorsement as a source cue. As source cues are only effective if people find the source trustworthy and credible, we would expect that respondents who identify with their nation have a stronger effect from the national majority endorsing the policy, while those that identify with ‘Europe’ should have a stronger effect from EU-wide majority endorsements. Such group-serving biases have been frequently observed in the EU context. For instance, Hobolt and Tilley (Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014) show that people with Eurosceptic predispositions tend to attribute responsibility for positive outcomes to the national level, while they blame the EU for negative outcomes. In order to measure group identification, we rely on the widely used question on exclusive national identity: ‘Do you see yourself as…? 1)

![]() $<$NATIONALITY

$<$NATIONALITY

![]() $>$ only, 2)

$>$ only, 2)

![]() $<$NATIONALITY

$<$NATIONALITY

![]() $>$ and European, 3) European and

$>$ and European, 3) European and

![]() $<$NATIONALITY

$<$NATIONALITY

![]() $>$, 4) European only, 5) None of the above’. For simplicity, all respondents choosing (1) are classified as having exclusive national identity, while we pool the less frequent responses (2), (3) and (4) in a category of respondents with some European identity.

$>$, 4) European only, 5) None of the above’. For simplicity, all respondents choosing (1) are classified as having exclusive national identity, while we pool the less frequent responses (2), (3) and (4) in a category of respondents with some European identity.

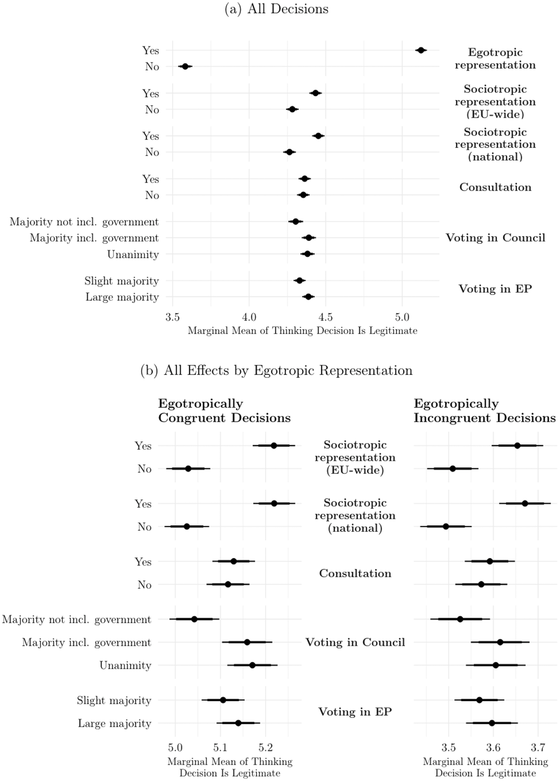

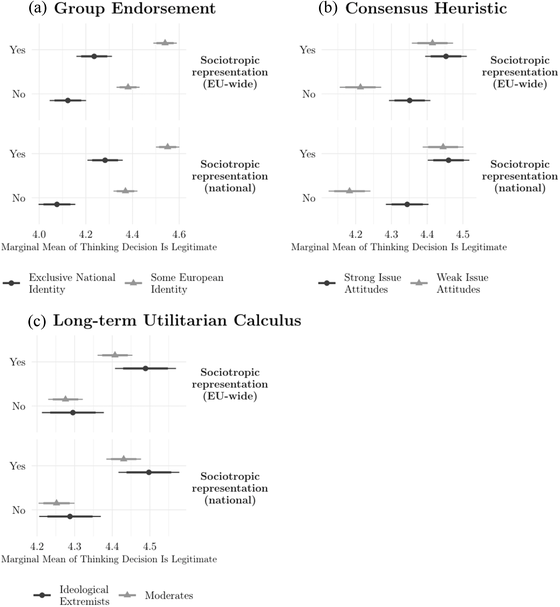

In panel (a) of Figure 3 we plot the sociotropic representation effects by group identification. Strikingly, we find that the effects of both sociotropic representation cues are about equally sized for respondents with exclusive national versus some European identity. The cue about the EU-wide majority preference also has an effect on respondents that exclusively identify with the nation, and national majority preference also sways the legitimacy beliefs of those with some European identity. Hence, we have no evidence that the effects of sociotropic representation on public legitimacy could be explained by group endorsements.

Figure 3. Mechanisms of sociotropic representation.

Notes: Marginal means with thin 95 per cent and thick 84 per cent confidence intervals; outcome is on 1 (‘not at all legitimate’) to 7 (‘very legitimate’) scale.

Second and alternatively, if the consensus heuristic is important, sociotropic representation effects should be stronger for respondents who hold weak attitudes towards EU policies, since such individuals are more likely to engage in heuristic instead of systematic information processing and take consensus information as a cue to form their opinion about the legitimacy of a decision. We consider attitude accessibility as a key component of attitude strength that is easy-to-measure operatively through response latencies – the time respondents take to provide their attitudes in surveys (Bassili, Reference Bassili1996; Mulligan et al., Reference Mulligan, Grant, Mockabee and Monson2003).Footnote 9 Specifically, we use the time respondents take to provide their political preferences on the five issue areas our political decisions relate to. Importantly, high attitude accessibility is closely related to other components of attitude strength, in particular, high attitude importance and low ambivalence (Krosnick, Reference Krosnick1989). If attitudes are highly important, respondents often think about them and resolve ambivalence about them, this clarity – in return – leads to fast accessibility. Mutz (Reference Mutz1998) and Axsom et al. (Reference Axsom, Chaiken and Yates1987) argue that low importance/involvement is most relevant for respondents’ reliance on majority preference as the ‘valid’ view. In panel (b) of Figure 3 we plot MMs for sociotropic representation, dividing the sample at the median into respondents with strong (short response latency) versus weak (long response latency) issue attitudes.Footnote 10 The results show clearly that the effects of sociotropic representation of EU-wide as well as national majority preference are stronger for respondents with weak issue attitudes. This is consistent with the consensus heuristic mechanism.

Finally, we evaluate the evidence for the long-term utilitarian calculus mechanism. If citizens consider decisions which represent majority preference more legitimate because the principle of majority representation is in their long-term interest, we would expect sociotropic effects to be larger for individuals that usually share the view of the majority. Specifically, we would expect that political moderates, who are in the centre of the preference distribution, should react more strongly to sociotropic representation than political extremists, who have outlying preferences (cp. Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005). To identify moderates and extremists, we rely on the widely used ideological self-placement item and count individuals that place themselves between 3 and 7 on an 11-point left-right scale as ‘ideological moderates’, while we classify individuals between 0 and 2 as well as 8 and 10 as ‘ideological extremists’. Panel (c) of Figure 3 reveals little difference in the effects of sociotropic representation between moderates and extremists – if anything, the effects for extremists are marginally larger. Hence, we have no evidence that the long-term utilitarian calculus mechanism explains the effects of majority representation.

In Online Appendix J, we also verify through regression analysis that the effects of sociotropic representation statistically significantly vary by the strength of issue attitudes, as stipulated by the consensus heuristic, but not by the factors relating to the other mechanisms. We also perform several robustness checks that support our main findings (see Online Appendix I.3).

Conclusion

Using a survey experiment fielded in five EU countries, we here provide original evidence that majority representation increases legitimacy beliefs in political decisions taken in a democratic, representative process. Importantly, this not only occurs because majority representation realizes the personal preferences of a large number of citizens, but also because citizens care about the representation of the majority in and by itself – irrespective of their own opinion about the policy.

Our analyses suggest that many citizens use majority support for a decision as a consensus heuristic for whether a decision is legitimate and whether they should accept it. And they seem to do so widely: no matter whether the majority cue relates to EU-wide or national opinion, whether individuals are Eurosceptic or only identify with the nation or whether the decision is in line with individuals’ personal preference. Majority representation matters in and by itself. This result directly speaks to and partially challenges important strands in the literature on EU public opinion. The fact that large parts of the European electorate are to some extent swayed by EU-wide majority opinion in their legitimacy beliefs provides evidence for the social acceptance of the EU polity and its new democratic majorities (cp. Weiler, Reference Weiler1991, p. 2471). In fact, we identify no group which does not increase its legitimacy belief in response to the sociotropic representation of EU-wide majority opinion. Hence, while other forms of EU public opinion, such as broad support for the EU, preferences for European solidarity or responsibility attributions to the EU are certainly constrained by citizens’ identity, values and predispositions (e.g., Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014; Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), these factors do not eradicate the effect of EU-wide majority representation on legitimacy beliefs in EU decisions. In addition, our findings also contribute to the general literature on decision acceptance (in particular, Arnesen et al., Reference Arnesen, Broderstad, Johannesson and Linde2019; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017) by showing that sociotropic representation can increase legitimacy beliefs if it is provided as a clear exogenous cue, which arguably happens frequently in reality through media reports of opinion polls or stories on what ‘people on the street’ think.

Our findings have important implications for the debate on how the EU can tackle its legitimacy crisis. Specifically, they support the claim by Hix (Reference Hix2008) that majoritarian representation could increase public support for the EU. According to our findings, majority representation will strengthen legitimacy beliefs at least through two channels:

1. Egotropic aggregation. If EU decisions are in line with majority opinion on binary issues, the effects of egotropic representation apply to the largest possible number of citizens.

2. Consensus heuristic processing. Especially citizens with weak issue attitudes on EU policies will assume that majority support for EU decisions signals the legitimacy or ‘validity’ of these decisions.

Importantly, our results suggest that by strengthening majority representation in day-to-day decision making, the EU cannot only increase the legitimacy beliefs of those citizens positively predisposed towards integration but also of Eurosceptics. Notwithstanding these findings, while following majority preferences will increase the sum of legitimacy beliefs across all citizens, it may dampen legitimacy beliefs of those citizens whose preferences deviate from the majority's on most issues. It therefore depends on the exact objective function of legitimacy that EU policy makers want to maximize to determine which EU decisions should be taken under what preference constellations (e.g., if only decisions with 80 per cent support should be adopted). Defining this function is, at bottom, a political task that can only be informed by academic findings (see Online Appendix M for simulations on how decisions affect the legitimacy beliefs of different strata).

In contrast to the impact of majority representation, our results point to only a small impact of procedural parameters on legitimacy beliefs. Moreover, this impact does not increase when decisions are not in line with personal preferences; concerns about procedures and their fairness are not heightened when outcome favourability is lacking (cf. Arnesen et al., Reference Arnesen, Broderstad, Johannesson and Linde2019; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2016). This discourages calls to solve the EU's legitimacy crisis by honing its institutional design, although we have to stress that our procedural variation in attribute levels stays within the ‘rules of the game’ of the current European constitutional settlement. Hence, we cannot generalize about large-scale institutional reforms of procedures through EU treaty making (for work on the effects of institutions in the EU/international context, see de Vries, Reference de Vries2018; Dellmuth et al., Reference Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg2019). But our results certainly highlight that in any future discussion of the EU's institutional architecture, reforms that aim at strengthening majority representation should receive special consideration (e.g., removing unanimity). With regard to day-to-day decision making, the weak effects of procedural parameters compared to those of representation also suggest that – in maximizing some objective function of legitimacy – the EU could potentially accept a weakening of inclusive decision making in the institutions if it serves representation goals.

A central limitation of our experimental design is that we only assess the legitimacy consequences of policy change. In all our vignettes, the EU has taken some decision. Therefore, we can contrast the consequences of different decisions but not compare taking a particular decision to retaining the status quo. A second limitation is that we do not incorporate party-related attributes of decisions. For instance, we do not provide respondents with cues about the voting behaviour of national and/or European parties. Third, we formulated our vignettes in a way to best ensure they primarily provide ‘neutral’ information about a decision. We deliberately did not vary the valence attached to our attributes. Future work should address these limitations with amended experimental designs. Such work could also investigate to what extent our findings travel to other political systems (e.g., apply in national policy making). For a better understanding of the exact interpretation and potential limits of the consensus heuristic, it would also be helpful to further vary the different types of majorities that are (not) represented by a decision (e.g., regional/local majorities, global public opinion).

All this will put us in a position to comprehensively assess the influence of majority representation on public legitimacy, and provide guidance to policy makers on how they can adjust day-to-day decision making in order to increase legitimacy within the existing institutional rules of Western democracies.

Acknowledgments

This work has been presented at the 2019 Annual Meetings of the Midwest Political Science Association and the European Political Science Association as well as at workshops and events of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies at Harvard University, the UCL Department of Political Science, and the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics. The authors would like to thank Christopher J. Anderson, Jack Blumenau, Bruno Castanho Silva, Nick Clark, Denis Cohen, Ben Lauderdale, Jorge Fernandes, Sara B. Hobolt, Fabian G. Neuner, Mafalda Pratas, Sven-Oliver Proksch, Bernd Schlipphak, Christine Trampusch, Catherine de Vries and Claudia Wiesner for very valuable comments on earlier versions of this article. They are also grateful to Lucile Dreidemy, Marion Laboure, Jan Nagel, Daniel Saldivia and Miriam Sorace for assisting with the translations of the source questionnaire. The survey fielded for this work was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Management, Economics and Social Sciences at the University of Cologne. The authors would like to acknowledge the generous funding by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation (20.16.0.045WW).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table B1: Correlations between Different Question Wordings

Figure C1: Age and Sex of Respondents

Figure C2: Urbanity and Education of Respondents

Figure D1: Left-Right Self-Placement (Comparison to Eurobarometer)

Figure D2: Support for EU Membership (Comparison to Eurobarometer)

Figure D3: Political Identity (Comparison to Eurobarometer)

Figure D4: Voting Intentions

Figure E1: Respondent's Personal Preference By Issue Area and Country

Figure F1: Effect of Vignette Order

Figure G1: Response Latencies by Vignette Order

Figure G2: Marginal Means of Perceived Legitimacy by Vignette Response Latency

Figure G3: Marginal Means of Perceived Legitimacy Excluding Fast Respondents (First Quartile)

Figure H1: Marginal Means of Perceived Legitimacy Excluding Egotropic Representation Effect

Figure I1: Marginal Means of Perceived Legitimacy by Euroscepticism

Figure I2: Marginal Means of Perceived Legitimacy by Eurosceptic Party Support

Figure I3: Marginal Means of Perceived Legitimacy by Populist Party Support

Figure I4: Marginal Means of Perceived Legitimacy by Education

Figure I5: Marginal Means of Perceived Legitimacy by Country

Figure I6: Marginal Means of Perceived Legitimacy by Issue Area

Figure I7: Marginal Means of Sociotropic Representation by Issue Area

Figure I8: Response Latencies to Vignettes by Personal, EU-wide and National Preference

Figure I9: Sociotropic Representation Effects by Attitude Strength Excluding Fastest Respondents (10%)

Figure I10: Test of Consensus Heuristic by Country

Figure I11: Sociotropic Representation Effects by Preference Outlier Status

Table J1: AMCEs of Attribute Levels (Both Outcomes)

Table J2: AMCEs of Attribute Levels (Group Endorsement Mechanism)

Table J3: AMCEs of Attribute Levels (Consensus Heuristic Mechanism)

Table J4: AMCEs of Attribute Levels (Long-term Utilitarian Calculus Mechanism)

Table J5: AMCEs of Attribute Levels (Congruent and Non-Congruent Decisions, Sociotropic Representation Only)

Table J6: Regression Results for All Three Mechanisms

Table J7: Regression Results for Interactions with Egotropic Representation

Figure K1: Marginal Means of Decision Acceptance

Figure K2: Marginal Means of Decision Acceptance for Non-Congruent Decisions

Figure K3: Sociotropic Representation Effects by Group Identification (Accept)

Figure K4: Sociotropic Representation Effects by Attitude Strength (Accept)

Figure K5: Sociotropic Representation Effects by Preference Extremity (Accept)

Figure L1: Difference in Ratings between Accept and Legitimate

Figure M1: Simulation of Change in Legitimacy By Public Support of Decision

Supplementary Material