Introduction

The Assisted Decision-making (Capacity) Act, 2015, (ADMCA), which was amended in 2022 and fully implemented in 2023, codified Advance Healthcare Directives (AHDs) for the first time in Ireland (ADMCA, 2015). Advance refusals of treatment set out in AHDs are legally binding provided that general conditions for their validity (the directive was entered into voluntarily and is not inconsistent with a capacitous person’s subsequent actions) and applicability (the person must now lack capacity, and the circumstances and treatment must be as specified in the directive) are satisfied. AHDs can include advance decisions pertaining to physical and mental health treatment (Decision Support Service 2023). However, for service users admitted involuntarily under the Mental Health Act, 2001 (MHA), the binding status of an AHD for mental health treatment depends on the grounds on which the person is detained (ADMCAA 2022, MHA 2001). By contrast, AHDs for physical health treatment are binding for all.

The MHA outlines criteria for involuntary admission on the grounds of illness, disability or dementia causing a serious likelihood of immediate and serious harm to self or others (the risk criterion – section 3[1] [a]), impaired judgment such that failure to admit is likely to lead to serious deterioration of the person’s condition or prevent administration of appropriate treatment (the treatment criterion – section 3[1] [b]), or both criteria simultaneously (MHA 2001). Prior to 2023, the criteria under which a service user was detained had no practical consequence for their care or treatment. However, the Assisted Decision-making (Capacity) (Amendment) Act 2022 (ADMCAA), introduced new clinical relevance to these criteria by stipulating that AHDs are binding on mental health treatment for involuntary service users only when detained under the treatment criterion (section 3[1] [b]) and thus not when detained on grounds of risk (section 3[1] [a]) (2022). Although the statute and the Code of Practice on AHDs for Healthcare Professionals (Decision Support Service 2023) are silent on applicability for service users detained on both grounds, a reading of the debates preceding enactment of the legislation strongly suggests intent to exclude this group from binding AHDs for mental health (Seanad Eireann Debate 2022). For this reason, we interpret the risk exclusion broadly in this paper. While the Mental Health Bill, 2024, proposes to extend binding AHDs for mental health treatment to all involuntary service users (in addition to revising the criteria for detention), several aspects of the Bill have attracted criticism (Kelly Reference Kelly2024) and at present, pending Seanad Eireann stages, the content of the final statute remains undecided.

Although its approach seems uniquely complex, Ireland is not alone in its differential treatment of advance directives for mental health treatment. A recent international comparison found that psychiatric advance directives tend to have less legal force, more restrictions on scope, and more conditions allowing the directive to be overridden than their medical equivalents (Gloeckler et al. Reference Gloeckler, Scholten, Weller, Keene, Pathare, Pillutla, Andorno and Biller-Andorno2025). For instance, in England and Wales, advance decisions to refuse treatment, legally binding under the Mental Capacity Act, 2005, do not apply to those detained under the Mental Health Act, 1983, unless they pertain to physical rather than mental health treatment. In contrast, Germany’s legal framework offers a more unified approach, where advance directives for physical and mental health treatment are commensurate and both remain binding during involuntary admissions. Ireland would appear to be unique in affording binding status to AHDs for some but not all of those detained in hospital under mental health legislation.

This distinction prompted our study of the characteristics of groups who would qualify for binding or non-binding AHDs at point of detention. What is already known about the groups detained on the grounds of risk (under section 3[1] [a] or both criteria) versus those detained under the treatment criterion (section 3[1] [b]) alone? Two prior studies have examined characteristics of service users detained under different MHA criteria in Ireland. The DIAS study, which studied eight years of involuntary admissions (n = 423) to three Dublin hospitals, found that detention based solely on the risk criterion was associated with female gender and having a diagnosis other than schizophrenia (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Curley and Duffy2018). A recent study examining ten years of involuntary admissions to Galway University Hospital (n = 505) found that those admitted under the risk criterion alone were younger and less likely to have a psychotic disorder or previous involuntary admission (O’Mahony et al. Reference O’Mahony, Aylward, Cevikel, Hallahan and McDonald2025). As binding force of AHDs was not the focus of these studies, both considered section 3(1)(a) alone and it is not apparent without further analysis whether these associations would carry to the broader group for whom AHDs would be non-binding at time of detention.

To date, no study has looked specifically at binding force of mental health AHDs for service users detained under the MHA. Our retrospective observational study therefore undertook to examine involuntary admissions to Elm Mount Unit, St Vincent’s University Hospital (EMU), over a three-year period from 2021 to 2023, with the objectives:

-

1. To compare characteristics of involuntary service users for whom AHDs would be binding or not (if the document were otherwise valid and applicable).

-

2. To calculate median bed days when an AHD would be binding versus non-binding for a service user admitted under the MHA.

Importantly, when we refer to binding force of mental health AHDs, we mean the potential binding force if a service user had an AHD for mental health treatment at time of detention. We did not have records of actual AHDs held by service users admitted to the unit and the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) (Amendment) Act, 2022, came into force midway through the period studied. However, we contend that as AHDs become more frequently used in mental health care, the issue of binding force during involuntary admissions will become increasingly pertinent for service users and psychiatrists. We note that recent survey data demonstrates a high willingness among Irish inpatient service users to make mental health AHDs (Redahan and Kelly Reference Redahan and Kelly2025).

Methods

Setting

EMU is a 36 bedded acute psychiatric unit (and approved centre within the meaning of the MHA) serving an urban/ suburban population across five general adult catchment areas in Dublin. General adult mental health care is delivered by multidisciplinary teams, led by consultant psychiatrists working across both community and inpatient settings under a sectorised model. Three beds are reserved for service users receiving care for eating disorders and six beds are for those under the older adult mental health service. EMU has no intensive care unit or seclusion facility but has access by referral to a private psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU).

Data collection

This is a retrospective observational study. We included all admissions of adult service users involuntarily detained to Elm Mount Unit between 2021 and 2023. Data was collected from the hospital’s register of residents and Mental Health Act documents associated with each admission.

We recorded service user characteristics including age, gender, occupation, marital status, country of origin, homelessness, substance use, and ICD 10 diagnosis at time of discharge. For patients with multiple diagnoses, a psychotic or mood disorder was accepted as the primary diagnosis. We recorded legal details including: initial detention under Form 6 or Form 13 and detention criteria used, mode of admission including whether initially admitted as a voluntary patient and the forms under which the application was made, detention criteria used on any Form 7 (renewal order) and Form 8 (tribunal report), and duration of involuntary status including date of Form 14 (revocation of the order) and Form 10 (transfer to another approved centre). We also recorded discharge destination, time from detention to discharge, whether the patient was admitted under general or older adult mental health, and the general adult catchment area (anonymised, to examine individual variability in practice).

Of note, we chose to code service users admitted with bipolar psychosis under the diagnostic group ‘bipolar disorder’ rather than ‘psychotic disorder’ to preserve integrity of the bipolar group, as service users with bipolar have called for advance directives in a nearby jurisdiction (Hindley et al. Reference Hindley, Stephenson, Keene, Rifkin, Gergel and Owen2019).

Data analysis

We employed descriptive statistics, Chi-square testing and Mann Whitney U testing as appropriate using IBM SPSS Statistics version 30.0 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA). We compared clinical and legal characteristics for all involuntary admissions for which initial detention criteria on Form 6 (admission order) or Form 13 (admission order to detain a voluntary patient) was available, according to whether a mental health AHD would be binding, that is detained under the treatment criterion (section 3[1] [b]), or non-binding, that is detained under section 3(1)(a) or both criteria. For admissions who were both detained and revoked in EMU (i.e. not transferred to another approved centre), we also calculated involuntary bed days per service user for which an AHD would be binding or not, through additionally examining detention criteria cited on Form 7 (renewal orders) and Form 8 (tribunal reports) over the course of the admission.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the SVUH Ethics and Medical Research Committee – RCR24-015.

Results

Characteristics of involuntary admissions to Elm Mount Unit (EMU) from 2021 to 2023

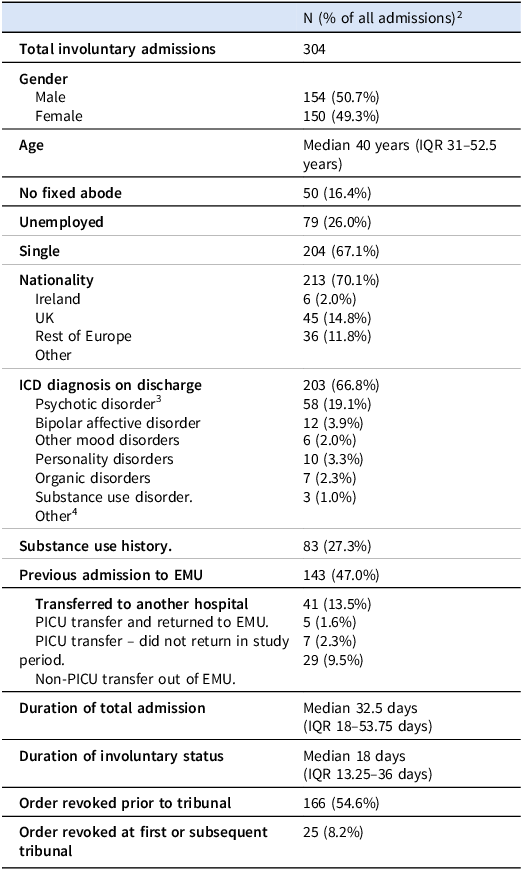

There were 304 involuntary admissions of 227 service users over the study period. These service users were inpatients for a median of 32.5 days per admission, of which a median of 18 days were involuntary. Table 1 outlines the characteristics of all involuntary admissions over the study period. Gender distribution was even within the full cohort (51% male). Most admissions were of service users who were single (67%). A minority were unemployed (26%) and of no fixed abode (16%). The most common diagnosis was of psychotic disorder (67%) followed by bipolar affective disorder (19%). Almost half (47%) had a previous admission to EMU.

Table 1. Characteristics of involuntary admissions1 to Elm Mount Unit (EMU) from 2021 to 2023

1Characteristics are per admission rather than per individual service user; there were 80 repeat admissions over the study period.

2Unless otherwise specified (i.e. for age, duration of admission).

3‘Psychotic disorder’ includes schizophrenia and delusional disorders (F20-29) and substance-induced psychotic disorders. It does not include bipolar psychosis, which was categorised under ‘bipolar affective disorder’.

4‘Other’ diagnosis included eating disorders, anxiety disorder, and intellectual disability.

Characteristics of groups for which mental health AHDs would be binding or not

We examined characteristics of groups for which AHDs for mental health treatment would be binding or not at point of detention through looking at detention criteria cited on Form 6 and Form 13. Information on MHA criteria cited at point of detention was missing for 17 admissions (5.6%), hence these were excluded from the analysis. This left a total of 287 involuntary admissions of 212 service users. The excluded group was not significantly different in terms of age (p = 0.94), gender (p = 0.76), or duration of involuntary status (p = 0.26).

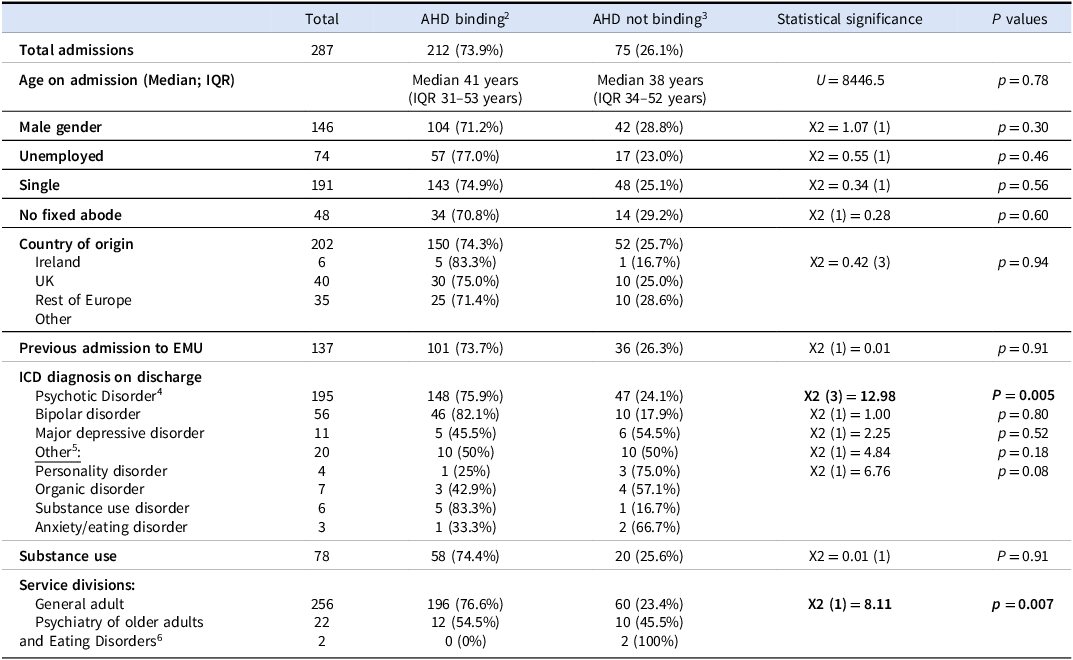

We found that 73.9% involuntary admissions in our sample would permit service users a binding AHD at point of detention (i.e. for 73.9% admissions, the person was detained on the treatment criterion alone). Table 2 outlines clinical characteristics of service user groups permitted binding or non-binding AHDs at point of detention. There was a significant difference in terms of diagnosis between groups for whom AHDs would be binding or non-binding (X2 (6) = 18.37, P = 0.005), but this was not accounted for by any particular diagnosis on post hoc analysis. There was no significant difference in terms of other clinical characteristics including age, gender, marital status, employment status, homelessness, or substance use. Service users in the general adult service (v. older adult mental health or eating disorders services) were more likely to be afforded binding AHDs (X2 (2) = 10.96, p = 0.004), although this may be explained by a significant difference in diagnostic groups across these services (X2 (12) = 75.36, P < 0.001). We tested for variability by general adult catchment area and found no significant difference in terms of criteria used at point of detention across sectors.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of groups for whom advance healthcare directives for mental health would be binding or not binding at point of detention 1

1All percentages given are row percentages.

2AHD binding: Initially detained under the treatment criterion only (section 3[1] [b]).

3AHD not binding: Initially detained under the risk criterion (section 3[1] [a]) or both criteria (section 3[1] [a]) and (section 3[1][b]).

4‘Psychotic disorder’ includes schizophrenia and delusional disorders (F20-29) and substance-induced psychotic disorders. It does not include bipolar psychosis, which was categorised under ‘bipolar affective disorder’.

5‘Other’ includes personality disorder, organic disorder (F1-F09, without psychosis), substance use disorders, eating disorders and anxiety disorders as the number of service users in each diagnostic group was too low for Chi squared testing.

6Psychiatry of Older Adults and Eating Disorders analysed as one group as the number of service users in the ‘Eating disorder’ group was too low for Chi squared testing.

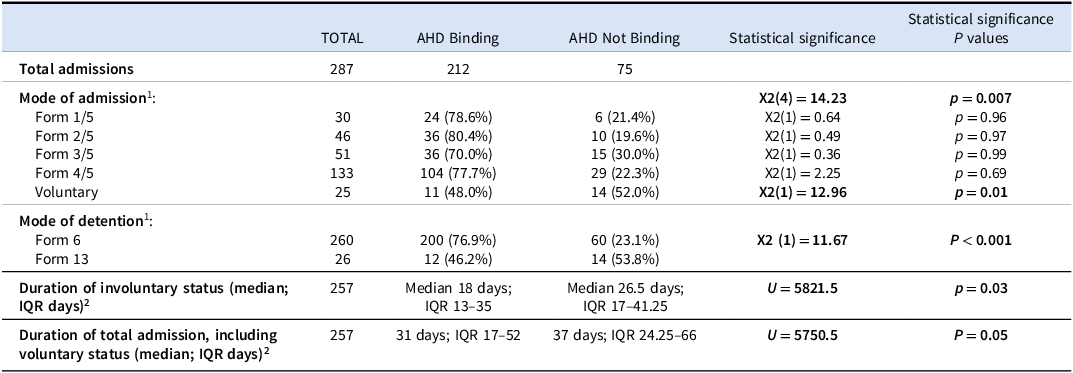

Table 3 outlines legal characteristics of service user groups permitted binding or non-binding AHDs at point of detention. We found that service users detained on Form 6 rather than Form 13 were significantly more likely to qualify for a binding AHD (X2 (1) = 11.67, p < 0.001), reflecting the increased likelihood that the risk criterion is invoked when a voluntary service user is detained after trying to leave. There was a significant difference in duration of involuntary status between groups with those afforded binding AHDs at detention having shorter involuntary admissions (U = 5821.5, p = 0.03).

Table 3. Legal characteristics of groups for whom advance healthcare directives for mental health would be binding or non-binding at point of detention

1Missing data included n = 1 missing for form 6/13 and n = 2 missing for application forms due to being transferred to EMU from other hospitals.

2Service users who were transferred to other hospitals on a Form 10 and did not return (n = 24), who remained inpatient at time of data collection in December 2024 (n = 1), or for whom Form 7/8 data was missing (n = 5), were excluded from bed day calculations.

We looked specifically at the subgroup of service users with bipolar affective disorder as this group has strongly endorsed mental health advance directives in a study in a neighbouring jurisdiction (Hindley et al. Reference Hindley, Stephenson, Keene, Rifkin, Gergel and Owen2019). In our study, service users with bipolar disorder were not significantly more likely to be permitted binding AHDs at point of detention than the wider group (82.1% v. the overall group’s 72.1%, X2 (1) = 2.35, p = 0.13). Of interest, involuntary service users with bipolar were less likely to be unemployed (17.8% v. 38.3%; X2 (1) = 6.99, p = 0.008) or homeless (5.2% v. 19.5%; X2 (1) = 6.9, p = 0.009) but otherwise had no significant differences from the wider group in terms of clinical and legal characteristics.

Changes to mental health AHD binding status over the course of admission

We examined how binding force of mental health AHDs was likely to change after the initial detention, through mapping how MHA criteria changed on Form 7 (renewal orders) and Form 8 (tribunal reports) over the course of an involuntary admission. To ensure an accurate picture of the whole service user journey, this was calculated only for admissions for which the service user was not transferred to another approved centre on a Form 10.

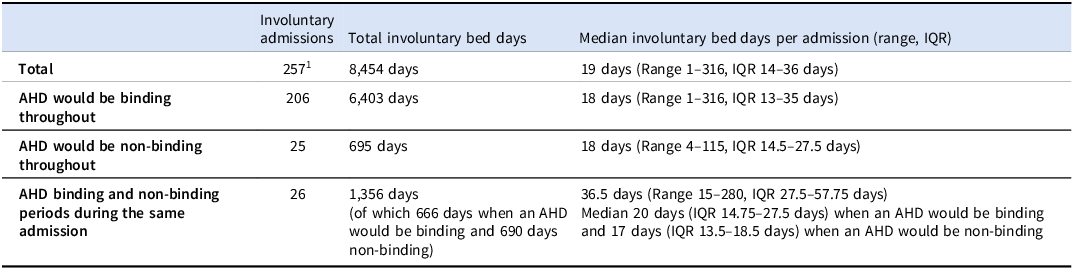

Initial detention criteria remained the same until the order was revoked for 231 of the 257 (89.9%) admissions for which this data was accessible. Of these, 135 were revoked prior to tribunal (58.4%), 19 were revoked at first tribunal (8.2%), and 77 had Form 7 and 8s citing the same criteria as the admission order (33.3%). For the 231 whose AHD binding status remained the same, 206 qualified for binding AHDs throughout (i.e. detained on treatment criterion only) and 25 would have non-binding AHDs throughout (risk criterion cited). Of the 25 non-binding throughout, 19 were revoked prior to or at tribunal (76%), that is only 6 had the risk criterion upheld at tribunal (24%).

For 26 of 257 admissions (10.1%), the service user had periods in the same admission when an AHD would be binding and periods when it would be non-binding. Of those, 21 would be non-binding at point of detention (risk criterion cited) and subsequently changed to binding, while 5 would be binding initially (detained on treatment criterion alone) but later changed to non-binding. We had no examples of binding status changing more than once throughout an admission. In terms of bed days, service users in this group had a median of 20 bed days when they would qualify for a binding AHD (IQR 14.75–27.5 days) and 17 bed days when their AHD would be non-binding (IQR 13.5–18.5 days).

Table 4 outlines AHD binding status over the course of the involuntary admissions in terms of involuntary bed days. Overall, we found that service users would be afforded a binding AHD for 83.6% of their involuntary bed days (7069 of 8454 days over 257 admissions).

Table 4. Binding status of advance healthcare directives for mental health over the course of the involuntary admissions

1Service users who were transferred to other hospitals on a Form 10 and did not return (n = 29), who remained inpatient at time of data collection in December 2024 (n = 1), or for whom Form 7/8 data was missing (n = 5), were excluded from bed day calculations.

Of note, 98 of 128 involuntary admissions that went to a first tribunal were affirmed under the treatment criterion (v. 19 revoked and 11 affirmed on grounds of risk or both criteria), that is of those admissions affirmed, 89.9% would be permitted binding AHDs thereafter and 10.1% non-binding.

Discussion

Our study found that 73.9% of involuntary service users were initially detained under the treatment criterion alone and therefore would qualify for binding AHDs for mental health treatment at point of detention under the current legal framework. We note that this proportion was larger than in previous studies: the DIAS Study found 66.4%, or 271 of 408 service users, calculated based on their Table 2 (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Curley and Duffy2018), and the Galway Study found 66.8%, or 327 of 492 service users, calculated based on their Table 2 (O’Mahony et al. Reference O’Mahony, Aylward, Cevikel, Hallahan and McDonald2025), detained on the treatment criterion alone. This discrepancy could potentially reflect sociodemographic characteristics of the catchment areas, although none were significantly associated with detention criteria in our study, or local detention practices, although we found no significant variability between general adult sectors admitting to EMU. It could also reflect changing practice over time, our sample being more recent than the other studies.

We found that the groups for which AHDs would be binding versus non-binding at point of detention differed significantly in terms of diagnosis. While no specific diagnostic group was identified, some groups being small, we noted that three of four service users with a primary diagnosis of personality disorder at time of discharge were detained under the risk criterion and so would not qualify for binding AHDs. Evidence remains limited for advance directives in personality disorders with a single RCT showing high user acceptability but no change in clinical outcomes (Borschmann et al. Reference Borschmann, Barrett, Hellier, Byford, Henderson, Rose, Slade, Sutherby, Szmukler, Thornicroft, Hogg and Moran2013). There has been particular interest in AHDs among the bipolar population (Hindley et al. Reference Hindley, Stephenson, Keene, Rifkin, Gergel and Owen2019) but our study showed no significant difference in binding status for bipolar service users. We did find the bipolar group significantly more likely to be in employment and fixed accommodation, sociodemographic factors which may plausibly facilitate AHD writing, although a recent Irish study showed no significant association of employment status with willingness to make an AHD in an inpatient population (Redahan and Kelly Reference Redahan and Kelly2025).

We found that those for whom AHDs would be non-binding at point of detention had a longer duration of involuntary admission and were more likely to be detained on a Form 13 rather than a Form 6. However, looking over the course of involuntary admission, we found that service users would qualify for binding AHDs on 83.6% of involuntary bed days in our study. This was partly explained by the fact that 89.9% admissions affirmed by the first tribunal would qualify for binding AHDs in the days afterward; the Galway study similarly reported a large majority of tribunals affirming on the treatment criterion (O’Mahony et al. Reference O’Mahony, Aylward, Cevikel, Hallahan and McDonald2025). While the merits of binding versus non-binding AHDs can be debated, it is important to recognise that non-binding AHDs can still helpfully guide treatment decision-making and provide a useful tool to support individualised care in keeping with a service user’s values and preferences (Gloeckler et al. Reference Gloeckler, Scholten, Weller, Keene, Pathare, Pillutla, Andorno and Biller-Andorno2025).

Our study has several implications for service users and psychiatrists. Firstly, service users writing mental health AHDs might be reassured by our findings that a majority of directives would be binding at point of detention (73.9%) and for a large part of their admission (83.6% of involuntary bed days). This is particularly pertinent as evidence shows that fears about directives being honoured is a barrier for service users completing their directive (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Gaillard, Vollmann, Gather and Scholten2023). While binding AHDs can cause concern among psychiatrists who fear that they will be used for radical treatment refusals (Shields et al. Reference Shields, Pathare, Van Der Ham and Bunders2014), evidence shows that the vast majority of AHDs conform with practice standards (Gaillard et al. Reference Gaillard, Braun, Vollmann, Gather and Scholten2023).

Secondly, our study found that binding status of AHDs changed during 10.1% admissions, but changes were only possible at formal reviews of the admission order (i.e. tribunals or renewal orders). While the law as it stands ties exclusion from AHD binding force to risk of immediate and serious harm, it does not permit flexibility to reflect changes in risk over the course of an involuntary order. Risk is dynamic; it may rapidly diminish following initiation of treatment, or with time, or may acutely escalate during admission for various reasons. Tying binding force of AHDs to detention criteria is a blunt instrument; choice of detention criteria was never designed to carry clinical implications and so there are no in-built review mechanisms. Such a rigid system carries the risk that psychiatrists who are anxious about the content of an AHD might be more inclined to detain on grounds of risk rather than treatment to permit the AHD to be more easily overridden.

To our knowledge, ours is the first study to examine potential binding force of mental health AHDs in Irish mental health units. Regarding generalisability, the study was limited by the fact that it was a single centre study and conducted over three years, a shorter period than previous studies looking at detention criteria. However, as EMU is a busy acute unit, we still had a substantial sample of 287 admissions for analysis of group characteristics by binding status at initial detention and 257 admissions for which bed day analysis was possible, with missing data owing to the high rate of transfers in and out of the unit. Further, the recency of the data collection may better reflect current practice, and this is important in understanding the potential for binding AHDs in Irish mental health units in the coming years. This was a retrospective chart review rather than prospective data collection, but we felt this was prudent given the actively evolving legal landscape. On this point, it is worth noting that our study period spanned pre- and post-ADMCA/ ADMCAA implementation and so it is possible that awareness of the new legal significance of detention criteria might have altered detention practice for later detentions.

Conclusion

The Assisted Decision-making (Capacity) (Amendment) Act, 2022, introduced new clinical relevance to detention criteria under the MHA by stipulating that AHDs are binding on mental health treatment for involuntary service users unless they are detained on grounds of risk. While mental health AHDs remain infrequently used at present, a 2025 survey demonstrated a high willingness to make an AHD among Irish inpatient service users (Redahan and Kelly Reference Redahan and Kelly2025). Should AHDs become more common, our study indicates that legally binding AHDs would apply for most service users for the majority of their inpatient stay. As such, psychiatrists will need to be cognisant of AHDs at time of admission and will need to review adherence of treatment plans to AHDs following tribunal decision. Future studies examining the practical use of mental health AHDs in clinical practice in the Irish setting will be of material importance to the speciality.

Acknowledgements

The research team thank Aine Kilcoyne, Mental Health Act Administrator at Elm Mount Unit, for her assistance and support.

Funding statement

This project received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

Dr Kane is a practising consultant psychiatrist currently based in Elm Mount Unit – she worked in the unit for 7 months of the 3-year data collection period. None of the authors have any other conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Ethical approval was granted by the St Vincent’s University Hospital Ethics and Medical Research Committee – RCR24-015.