6.1 Introduction

The popular narrative in Estonia says that, during the revolutionary periods, there have never been serious alternatives to political independence. From 1991 onwards, this narrative has not lost its momentum. However, this chapter looks at the period of 1987–1988 and claims that it was the finest hour for imagining alternative futures for Estonia.

In the distant past, there have been several, even utopian visions of how we could ‘imagine alternatively’ Estonia’s future. For instance, socialist revolutionary poet Gustav Suits proposed a dual Finnish–Estonian state in November 1917 and later the ‘Estonian Labour Republic’ (Eesti Töövabariik) in January 1918.Footnote 1 In 1972, when Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union, the Estonian émigré professor Rein Taagepera proposed his 30-year plan for Estonia towards a socialist satellite state status (the ‘Hungarian path’).Footnote 2 Both envisioned Estonia as expanding the internal sovereignty but sharing the united external politics. Both men shared the view that it is important to focus on the available resources at your disposal, to exhaust all the means to survive as a nation, even if it does not severely cut ties with the big neighbour. In 1987–1988, new imaginary scenarios emerged in Estonia. Should Estonia develop itself into an economically independent republic (or at least a free trade zone) in the renewed Soviet Union, to a sovereign socialist republic (which shares its foreign and defence politics with the centre) or an independent republic, restored by the legal continuation of the pre-war Republic?

In a more general sense, this chapter shows how the imagination of alternative futures take place in a state-socialist system which has opened all the channels to vision and discuss reforms. In what language and through which concepts are the alternative futures being produced? Taking Soviet Estonia as a case study, the chapter shows the specific concepts during the mid-perestroika (1987–1988) period which opened, facilitated, but also delimited the imagination of Estonian futures. The chapter argues that these concepts were innovated by local reformists, through which the alternative scenarios were constructed, creating the peripheral ‘conceptual revolution’ during the perestroika.

6.2 Creating the Repertoire of Futures

Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in 1856, that ‘it is not always that things are going from bad to worse that revolutions break out. On the contrary, it oftener happens when a people suddenly find the government relaxing its pressures.’Footnote 3 Relaxation of the top-down planning in the economy but also the media censorship during 1986–1987 became the most visual marker of the change in Soviet society. In retrospect, we can conceptualize this moment as an early revolutionary situation. Nowadays, many scholars confirm Tocqueville’s observation, however, less has been said about specific conceptual processes of how these ‘moments of relaxation’ during the pre-revolutionary periods become revolutionary situations. Charles Tilly has defined the nature of ‘revolutionary situations’ in history by referring to the main two characteristics as ‘the appearance of contenders, advancing exclusive competing claims to control the state, or some segment of it’ and the ‘incapacity or unwillingness of rulers to suppress these contenders’.Footnote 4 While these conditions were indeed present in 1988 in the Soviet Union, I am more interested in looking at the more ambiguous start of this situation in which the contenders emerge from the local political and scholarly elite. Which claims, concepts and arguments do these contenders use, and in which forms do they make them? Tilly’s concept of ‘contentious repertoires’ brings us closer to this question.Footnote 5 According to Tilly, ‘repertoires’ refer to ‘claim-making routines that apply to the same claimant–object pairs … these can include, for instance, petition letters, pamphleteering, strikes, civil disobedience, etc.’Footnote 6 Repertoires function as an available structural menu for contenders (to choose their action form), but also limit it, as, according to Tilly, repertoire changes very rarely.

However, Tilly’s approach to ‘repertoires’ as a menu for contentious actions was related to the direct, physical form of action and not so much to intellectual conditions. For instance, although Tilly highlights ‘pamphleteering’ in France in the eighteenth century before the French Revolution, we are not shown the actors’ manipulation in the pamphlets to pursue their political goals, or whether, and if so, how, some concepts were made oppositional. In this chapter, I view expert concepts, argumentative languages and even scientific methods as potentially open to innovation and manipulation in the political sphere. Thus, I want to expand the concept of repertoire for innovators in revolutionary situations by moving from direct physical forms of contention to more abstract ones, considering many more linguistic aspects. Which kind of ‘concepts’ and ‘languages’ can be used in the moments when the regime’s pressure has been relaxed, but only a limited array of concepts are at hand? To answer that, I will turn next to the Estonian case, which shows the importance of concepts, including its impact on the Soviet collapse.

6.3 From ‘Future Scenarios’ to ‘Self-management’ in 1987

Two years before Polish Round Table Talks (February–April 1989), before the Civic Forum and Václav Havel’s last arrest by the secret police in Prague in October 1989 and before the first mass demonstration in Romania in December 1989, one of the first revolutionary situations in Eastern Europe after the Solidarność movement, where (to use Tilly`s words) ‘the contenders advance claims to control some segment of the state’, emerged in 1987 in Soviet Estonia. On 26 September 1987, a group of Estonian scientists and experts published a short article entitled ‘A Proposal: Estonian SSR to Full Self-Management’ (Ettepanek—kogu Eesti NSV täielikule isemajandamisele) in the progressive local newspaper Edasi (Forward).Footnote 7 Four men were named in the byline (Siim Kallas, Tiit Made, Edgar Savisaar and Mikk Titma) and, thus, the document was quickly named the ‘Four-Man Proposal’ (Nelja mehe ettepanek). All four men were members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).Footnote 8 The proposal called upon the Estonian government and the scientific community to draft plans to achieve an independently operating economy in the union. The request declared the need for ‘a radical rearrangement of the Estonian economy and the society as a whole’. The proposal’s main message was that public debate should be started on how to gain ‘full self-accounting status’ for the republic and how to place the economy (including all-union enterprises) on Estonian territory completely under the jurisdiction of the Estonian SSR. The article also proposed giving the republic its national currency. The novelty of the revolutionary ‘Four-Man Proposal’ consisted of the quest for financial independence of the republic – the claim for the budgetary control over the all-union enterprises, independent economic foreign relations, taxation and currency on the republic’s level was unheard of in the Soviet Union. The proposal was considered a ‘utopian’ plan by many contemporaries. Siim Kallas (one of the signatories of proposal) later said that, although the project was clearly unreachable, ‘it was still very useful and healthy project, which helped [metaphorically] to heat the oven, to present constantly more and more radical claims to Moscow’.Footnote 9

The project was also presented as ‘opening up the multiple scenarios’, inviting experts and scholars to join the debate. This approach was established in May 1987 through a public contest of ‘economic development scenarios’ announced by the main activist of the Four-Man Proposal, Edgar Savisaar, who headed the department in the Estonian Plan Committee, the regional branch of Gosplan. Although the scenario method known by the local management school from the 1970s, the contest for ‘future scenarios’ was the first of its kind in Estonia. The Planning Committee’s official manual for contestants stated that:

The contest aims to receive original, scientifically argued, alternative future scenarios that would consist of well-explained ideas for structural changes and economic innovation in the republic; to deploy new techniques for future visioning that would meet the objective conditions of the modern age, and to form interdisciplinary expert groups of scientists from different fields.Footnote 10

More than 100 teams registered for the contest; although only around 20 proposals were accepted (because of the contest’s strict requirements), and 6 of these won prizes.Footnote 11 The topics of the scenarios included imagining foreign trade in ESSR in the service sector, the vision for secondary schools, reforms in agriculture and so on. After the contest, Savisaar demanded from the government that the six winning scenarios be made public and debated with scientists. The public discussion (as a pillar for glasnost policy) was supposed to change the political culture. Savisaar wrote, in spring 1988, that is why ‘a scenario method is an ideal tool for a dialogue between scientists and the political authorities, helping to present alternative future visions and their probable results’.Footnote 12 However, the results of the contest were not taken into account at higher levels of political decision-making. This was one of the reasons why Savisaar organized another brainstorming session with an expert group in the Plan Committee in August 1987. The task for the experts was to continue with the scenarios, this time to work out innovative ideas on how to radically change the whole republic`s economic management. However, fearing that it will stay in the cabinets like the scenario contest, Savisaar decided to publish the new proposal straight away in the popular media and it was made on 26 September 1987. Although the new proposal was worked out by approximately ten members, it was publicly signed by only four men in September.

The Four-Man Proposal called the Estonian scientific community to brainstorm the concept of ‘territorial self-management’ (isemajandamine) and to ‘release the intellectual resources of the people’. Most importantly, it generated a massive debate from October 1987 until the end of 1988. The discussions on ‘what it would take to carry out this project’ took place every week, mostly in progressive newspapers, mobilizing reform-minded top officials, intellectuals and academics from very different fields. In the end, the reform-minded vice-chairman of the Council of Ministries of Estonia, Indrek Toome, publicly endorsed the project. The new project was exported to other Baltic republics as well. In the autumn of 1988, the governments of all three Baltic republics established a common platform to begin negotiations with Moscow to gain ‘economic independence’ from central planning. Two concepts, the ‘scenario method’ and ‘economic self-management’, had not only helped to construct a novel political project but also facilitated the scientists’ path to politics.

Thus, Estonian experts and scientists entered politics by means of their professional language. How unique was this process in East Central Europe? Although it was an exceptional move in the Soviet republics, we can find similar cases in some other countries. For instance, Czechoslovakian forecasting scholar Miloš Zeman rose to politics with his article Prognostika and Perestroika, published in August 1989. While Savisaar in Estonia employed the concept of ‘future scenario’ in 1987, Zeman used ‘prognostika’ in 1989 as an important scientific source of critical thinking on the ‘plurality of possible futures’.Footnote 13 Just like Savisaar, Zeman emphasized the necessity of dialogue and public discussion on both social and economic problems. In both cases, the published texts were arrowed at the ultra-centralist rule. This shows one transnational current in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, where forecasting experts became politicians with the help of their professional language. Both men eventually became prime ministers of their countries; Savisaar in 1990 and Zeman in 1998.

Month after month, the utopian project of ‘self-management’ (isemajandamine) gradually expanded in Estonia. The meanings that were initially connected only with economic policies permeated the social and political sphere in early spring 1988. The Tartu Group of Self-Management (Isemajandamise Tartu rühm), consisting of academics from various fields at the University of Tartu, stated in their first meeting on 15 February 1988, that ‘isemajandamine is not only an economic but also a social and ideological problem … the hope is that regulating the society’s economic base will also reactivate social mechanisms’.Footnote 14 A fundamental shift in the rhetoric was the group’s statement that ‘the economy is only an instrument for the ultimate goals of isemajandamine’, which were the ‘increase of sovereignty and subjectivity, growth of welfare, increase of freedom of choice, etc.’Footnote 15 The ‘self-management’ as a concept quickly expanded to self-management in all spheres (culture, environment, regional policy, etc.).

Again, comparing the Estonian case with the developments in East-Central Europe in that period, there is a similarity between this discourse of ‘self-management in all social spheres’ and the discourse of self-management in the civic society proposed by Czech dissidents in the mid-1980s. In 1985, Czech dissident Petr Uhl, in his essay ‘The Alternative Community as Revolutionary Avant-garde’, explicitly says that ‘social (and not merely economic) self-management is a combination of direct and indirect forms of democracy’.Footnote 16 In the same year, another Czech dissident, Rudolf Battěk, argued in favour of ‘different forms of self-management’ and the need for ‘pluralizing sovereignty’ in society. According to Battěk, ‘social structures can be democratized by expanding the elements of self-management, limiting institutional growth, making allowances for ideas as motivational factor, and strengthening direct democracy by eliminating priorities and privileges’.Footnote 17 Paul Blokker has described it as a continuation of ‘republican language’, as it promoted direct democracy, people’s moral responsibility to the state and civic initiative from below.Footnote 18 The intriguing part is that, whereas in East-Central Europe this ‘language’ was kept alive by dissidents, in the Estonian SSR it emerged from the community of social scientists, many of them being members of the Communist Party.

6.4 From ‘Self-management’ to ‘Sovereignty’ in 1988

The Tartu group changed the abbreviation of isemajandamine (IM) to IME (Isemajandav Eesti) in the spring of 1988. In Estonian, ‘IME’ literally means ‘miracle’ (ime), which helped to give the movement even more positive, creative, even spiritual image. Reformers saw that, although an (economically) utopistic project, a miracle in that sense, it mobilizes the whole nation. By autumn 1988, IME had multiple simultaneous meanings – it denoted a social movement, economic independence, and social self-regulation, but perhaps most importantly it acquired the meaning of political sovereignty.

Indeed, from the perspective of world politics, the most important by-product of the mushrooming discourse on self-management was the revival of the forgotten concept of ‘sovereignty’ at the end of 1987. By the constitution of the Soviet Union (1977), every Soviet republic was a ‘sovereign socialist Soviet state’ (§ 76). The concept of ‘sovereignty’ (in Estonian, suveräänsus) was brought into the IME debate in October 1987 by lawyers who said that the republic’s economic independence cannot be achieved without the republic’s sovereignty. Legal scholar Indrek Koolmeister was the first, who stated in October 1987 that ‘speaking of being a master in your country, it is not only an economic but also a political-legal category … to speak about the people as a master at the state level means to talk about the sovereignty of people, about its power, and the ways of its realization’.Footnote 19 From there, several lawyers started to argue that ‘sovereignty’ was a constitutional right of every Soviet republic, as the all-union constitution clearly states. Legal scholars Igor Gräzin and Peeter Kask emphasized in November 1987 that ‘the republic`s self-management presumes the sovereignty of the republic to expand its rights … and using the constitutional rights that ensure sovereignty is not only the republic’s right but also its duty’.Footnote 20 It was a remarkable conceptual transfer of the ‘sovereignty’ from constitutional law to the public sphere, irrespective of the fact that, only a year earlier, this very concept was not perceived by Estonian reformers applicable on the political arena at all.

In September 1988, the politically and legally more useful term ‘sovereignty’ replaced ‘self-management’ in reformists’ tactics. During the 11th Plenum of the Estonian Communist Party on 9–10 September 1988, Estonian political scientist Andrus Park invited others ‘to pay attention to the legal-political questions to secure the Estonian SSR’s economic independence’, stressing that ‘the keyword for the IME movement from now on should be “sovereignty” and only then “self-management”’.Footnote 21 However, the final manoeuvre was made due to a direct constitutional dispute with Gorbachev’s team, who demanded in summer 1988 that Estonia should confirm the new amendments in the Soviet Union’s constitution. In response, on 16 November 1988, the Supreme Soviet of the Estonian SSR adopted the Declaration of Sovereignty. The declaration asserted the ESSR’s ‘sovereignty’ and Estonian laws’ primacy over those promulgated by Moscow’s all-union government. This step became a blueprint that was soon followed by virtually all other Soviet republics (including the Russian SFSR) and many autonomous republics in 1989–1990. This process, known as the ‘Parade of Sovereignties’,Footnote 22 put the central government at a serious disadvantage in its efforts to re-establish control over the Soviet Union and led to its dissolution in 1991.

The importance of the ‘sovereignty factor’ on the dissolution of the Soviet Union has been acknowledged. Edward D. Walker has written the most meticulous study on the effect of the factor on the USSR’s dissolution. Walker emphasized the importance of the sovereignty declarations adopted in 1988–1990, saying that

‘Sovereignty’ killed the Soviet Union … The concept of ‘sovereignty’, more than any other competitor such as ‘democracy’, ‘liberty’, or ‘markets’, was used with great effect by the anti-union opposition in the union’s republics to challenge the authority of the USSR’s central government.Footnote 23

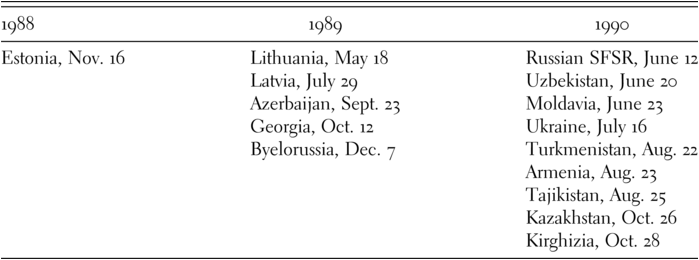

The political efficiency of the concept was also highly esteemed by Boris Yeltsin, who recalled later that ‘as soon as the word “sovereignty” resounded in the air … the last hour of the Soviet empire was chiming’.Footnote 24 Throughout 1990, Boris Yeltsin presented ‘sovereignty’ as a central concept in his speeches in RSFSR regions, calling on regions to declare their sovereignty. Eventually, all fifteen union republics (SSRs) in the Soviet Union and twenty-six different autonomous regions (including ASSRs) in the Russian SFSR adopted sovereignty declarations between 1988 and 1991 (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 The ‘Parade of Sovereignties’ (SSRs)

| 1988 | 1989 | 1990 |

|---|---|---|

| Estonia, Nov. 16 | Lithuania, May 18 Latvia, July 29 Azerbaijan, Sept. 23 Georgia, Oct. 12 Byelorussia, Dec. 7 | Russian SFSR, June 12 Uzbekistan, June 20 Moldavia, June 23 Ukraine, July 16 Turkmenistan, Aug. 22 Armenia, Aug. 23 Tajikistan, Aug. 25 Kazakhstan, Oct. 26 Kirghizia, Oct. 28 |

While the importance of the ‘sovereignty factor’ on the dissolution of the Soviet Union has been recognized, some of its questions remain unanswered. For instance, why did it happen first in Estonia and not in other Soviet republics? Why did the concept of ‘sovereignty’ rise to prominence in Estonia in late 1987? What was the reason for this particular development in the ESSR on the all-union scale?

Even though in November 1988 the ‘sovereignty of the Estonian SSR’ was declared on the grounds of the ESSR’s constitutional rights, its unexpected ‘emergence’ in late 1987 was related to something else. The rebirth of ‘sovereignty’ in Estonia was caused by the need to form a legal basis for the project of territorial self-management. In other words, in 1987–1988, ‘sovereignty’ was supposed to serve the goal of ‘self-management’ and not vice versa. ‘Self-management’ became a central political concept in the ESSR from September 1987 onwards, before it was replaced by its local successor, ‘sovereignty’, in late 1988. It was an unintended conceptual consequence of the gradually expanding debate on self-management in 1987. Thus, to understand the spread of ‘sovereignty’ in Soviet republics in 1987–1989, one should pay attention not only to constitutional factors (i.e., to the Soviet constitution) but also to why and where the new claim arose, what its relation was to other concepts in the ongoing debate, and which contextual resources made it possible to create those preceding claims.

6.5 Two Conceptual Revolutions: Central and Peripheral

The Sovietologist Archie Brown was the first, in 1989, to describe the years of the mid-perestroika campaign (1987–1988) as a ‘conceptual revolution’. To quote Brown, ‘the conceptual revolution, like perestroika in general, was in many respects a revolution from above, stimulated by the new vocabulary of politics Gorbachev used’.Footnote 25 Brown pointed out several concepts in Gorbachev`s speeches that ‘helped to open space for the new political activity’.Footnote 26 During perestroika, in 1989, Archie Brown noted that Gorbachev and his allies used three ‘new concepts’ in 1987–1988, which, according to Brown, ‘deserve special emphasis, as they helped to open space for new political activity and provide a theoretical underpinning for some of the concrete reforms that the more radical interpreters of perestroika were attempting to implement’.Footnote 27 These were (1) ‘socialist pluralism’ (sotsialisticheskoe plyuralizm) as a pluralism of opinion; (2) ‘state based on the rule of law’ (pravovoe gosudarstvo); and (3) ‘checks and balances’ (sderzhek i protivovesov) as separation of powers.Footnote 28 All three received the endorsement of Gorbachev, which corroborates Brown’s claim about ‘the revolution from above’. However, as we have seen, there was another, parallel conceptual revolution ‘from below’ (or ‘from the side’) happening in the periphery – the cases of ‘self-management’ and ‘sovereignty’ in Estonia showed the power of concepts during the perestroika. We saw the miraculous revival of ‘sovereignty’ in 1988, but the Estonian version of ‘self-management’ (isemajandamine) was similarly remarkable. What is the origin of that particular concept? Next, I will briefly describe the conceptual genealogy of isemajandamine in Estonia.

The Estonian term isemajandamine was part of the Soviet economic vocabulary. It was a translation from a Russian term khozrachet (an acronym of the longer version khozyaistvennyi raschet). As a Bolshevist concept, it was coined in the early 1920s, when Lenin and Bukharin explained the basis of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in terms of the ‘system of khozraschet’.Footnote 29 To work ‘on khozraschet’ meant that a given economic unit (factory, enterprise) had achieved self-sufficiency, in which costs were covered from the unit’s own profits, that is, independently of state directives. Thus, it was completely different from Marxist concept of workers’ ‘self-government’ (sometimes used as a synonym to ‘self-management’) which had its own historical roots in East Central Europe (radnicko samoupravljanje in Yugoslavia; samorząd robotniczy in Poland, etc.). In short, khozraschet denoted the economic independence of the unit. In 1941, when the Soviets occupied Estonia, khozraschet was translated into Estonian as isemajandamine.Footnote 30 It was widely used during the late 1950s (related with Khrushchev’s Sovnarkhoz reform) and during the Kosygin reform plans in the mid-1960s when the self-sufficiency of the economic system was set as the priority in the reform agenda. In the 1970s, the concept faded from the publicity into a long quiescence everywhere in the Soviet Union, including in Estonia. During the early perestroika, NEP and khozraschet returned to the Soviet economic debate, perhaps most powerfully with pro-perestroika economist Nikolai Smelev’s article ‘Advances and Debts’ (‘Avansy i dolgi’) in Novyi Mir in June 1987.Footnote 31 From mid-1987 onwards, Gorbachev incorporated the term into his programmatic vocabulary and frequently spoke of the need for ‘full cost accounting in enterprises’ (polnyi khozraschet predpriyatii).Footnote 32 For instance, in his June 1987 speech in the CPSU Plenum, Gorbachev proposed that all state enterprises work ‘on full self-accounting and self-financing’, starting in 1988.

Smelev described khozraschet as more than just an accounting term. As he saw it, the NEP marked the transition from ‘administrative socialism’ to ‘khozraschet socialism’.Footnote 33 However, in official Soviet economic discourse, the term still had a very technical meaning. It regulated only the management forms and hierarchical relations within the economic units. For instance, khozraschet’s qualifiers were ‘internal’ (in Russian, vnutrennyi; in Estonian, sisemine) and ‘full’ (in Russian, polnyi; in Estonian, täielik). Vnutrennyi khozraschet (internal self-accounting) was a management form in which only a small individual unit within a collective farm or enterprise (such as a brigade) had khozrachet status. In contrast, in polnyi khozraschet (full self-accounting), the whole enterprise or farm worked as an economically self-managing unit. It was used everywhere in the Soviet Union only as a technical accounting term, referring to the enterprises’ obligation to operate without losses and not to anything else. It was also the case with the Estonian SSR until 1987, when the Four-Man Proposal radically changed the conventional meaning of khozraschet. The conceptual change was made on two levels. The first was in September 1987, when the Four-Man Proposal lifted its meaning from the individual-unit (enterprise) level to the territorial (republican) level. The second took place in spring 1988, when the Tartu Group of Self-Management and the IME Council expanded it from the strictly economic level into a much broader social sphere. The aforementioned changes also had a specific linguistic resource. The Estonian term isemajandamine had the prefix ‘self-’ (ise-), which made it similar to another Estonian term, iseseisvus (‘independence’). The prefix was missing not only in the Russian term khozraschet but also in its translations to the native languages in other Soviet republics. This particular resource explains (but only partially) why the conceptual innovation of khozraschet was so resonant in the Estonian SSR.

The innovation of the isemajandamine inadvertently made space for other concepts and subsequent shifts, as it motivated other economists to come up with alternative ideas. In the autumn of 1988, economist Arno Köörna proposed that, instead of being a ‘self-managing republic’, Estonia should become the first ‘free economic zone’ in the Soviet Union, based on the Chinese model.Footnote 34 The proposal of a ‘free economic zone’ by Köörna attracted numerous critics discussing how to proceed with the reforms in Soviet Estonia. While Köörna and his supporters emphasized that becoming a special economic zone would be ‘concrete, real and radical’, the vast majority of economists and intellectuals argued against it, saying that a free economic zone would not be a step forward but rather a step back. In October 1988, the rival working groups of the ‘self-management’ project (the Economic Institute of the Academy of Sciences and the IME Council) published a joint position paper in which they highlighted all the criticisms of Köörna’s idea. The main point was that ‘a self-managing republic can only be a sovereign state, whereas an economic zone can exist only as a part of a state but never as a state as a whole’.Footnote 35 In other words, the orientation of the political elite was clear – it was not towards economic but to political sovereignty in 1988. In other words, the imagination process was so rapid that visions that might have been welcomed as innovative and appropriate in late 1987 (like a free trade zone) were, in the second half of 1988, interpreted as outdated, unnecessary and even dangerous to the IME project. Within a year, an economic proposal had been changed into a political request for republic’s sovereignty. The peripheral ‘conceptual revolution’ had transformed economic concepts into political ones.

6.6 Conclusion

Concepts which derive from an expert-language framework can acquire broader resonance and meaning in society and contribute to the rise of a revolutionary situation. This chapter shows the identification of those conceptual processes in pre-revolutionary periods. A specific conceptual process sequentially unfolded in the ESSR in 1987–1988, culminating in the concept of ‘sovereignty’ rising to prominence in late 1987. First, the conceptual innovation of ‘self-management’ (isemajandamine) in Soviet Estonia enabled new kinds of social and political mobilization at different levels: (1) it opened the public press as a new discussion channel for the academics and experts who became involved in an intense debate about the current economic and political situation in Estonia; (2) official working groups were created to develop the idea at the level of the Communist Party and the Academy of Sciences; and (3) it helped to create a common conceptual platform for the Popular Fronts (and later for the national governments) of the three Baltic republics in their quest for economic independence. Secondly, if we analyse official language and concepts in authoritarian regimes, we have to consider the highly ideologized language, hierarchical discourse, censorship constraints, code words, previous connotations, and so on. The reform-minded scientists who masterfully innovated the old term, isemajandamine (which started to signify utopian situation where the whole republic could be financially independent), filled the conceptual void for reform-socialist forces. It became the centre of their language for two years (1987–1988) before it led to ‘sovereignty’ at the end of 1988 when the new concept took over the lead role in the reformists’ agenda. Thus, ‘self-management’ acted like a vanishing mediator, a utopian project, but at the same time an extremely useful one for the local reformers. Both the project and concept (isemajandamine) disappeared in 1991, when Estonia become an independent state, and has not been used in the local political sphere since.

However, it is important to stress that the political development of the ‘self-management’ project in 1987–1988 was an open-ended process without foreseeable consequences. One of the members in the initial expert group, management scholar Erik Terk, said in 2018 that ‘we had no way of knowing how it would end … we did not imagine independence; the realistic aim back then was to negotiate as many economic rights from Moscow as possible’.Footnote 36 The development in the direction of political independence in 1988 was not initially planned as a step-by-step strategy, even if in hindsight it is very tempting to see it this way. We should not underestimate the role of the scenario method, used by the experts in the IME movement. We could illustrate this as a serendipitous process. The invention of ‘territorial self-management’ in September 1987 inspired the scholarly audience to produce new concepts (that they were not using in the first half of 1987) like ‘sovereignty’. Eventually, the concept of ‘sovereignty’, which was initially meant to serve as a legal empowerment for the self-management project, turned out to be the most powerful concept for all Soviet republics.

The process of expanding the ESSR’s economic-territorial rights, from ‘self-management’ to ‘sovereignty’, eventually culminated with the official Declaration of Sovereignty, the first of its kind in the Soviet Union (16 November 1988). In 1989–1990, following the Estonian example, all Soviet republics issued their declarations of sovereignty, including the Russian SFSR in June 1990. This process, known as the Parade of Sovereignties, seriously disadvantaged the position of the central government in its pursuit to rebuild the union and, therefore, led to its dissolution. What initially started as a local territorial innovation plan, almost as an imaginary utopia, ultimately had very serious and unexpected legal consequences for the Soviet empire.