1 Introduction

The idea that we need a transition is omnipresent in climate discourses today. Three recent examples illustrate the ubiquitous use of transition in Earth system governance. The first instance occurred at COP28 in Dubai, controversially presided over by Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, CEO of Abu Dhabi National Oil Co (ADNOC). All parties agreed on a roadmap for ‘transitioning away from fossil fuels’ (UN, 2023), but no clear timeline was agreed. The second example is the European election campaign in France. Jordan Bardella, the young and media-friendly president of the French far-right party National Rally (RN), announced that France had completed its energy transition (Wakim, Reference Wakim2024). Bardella conflated electricity use (mainly from nuclear energy) with the entire energy consumption mix in a misleading move aiming to defend energy sovereignty. The final example is the Energy Institute (EI) report on the global energy market, which highlights that despite all the rhetoric of green transition, fossil fuel consumption and emissions have reached unprecedented levels. Nick Wayth, Chief Executive of EI, declared ‘the transition has not even started’ (Chu, Reference Chu2024). A puzzle, then, emerges: is ‘transition’ simply a doublespeak for international climate conferences? Has it ended, or has it not even started?

Significant scholarship in political theory and environmental studies has shown how much metaphors and language matter in politics. ‘The language of politics is obviously not the language of a single disciplined model of intellectual inquiry,’ rightly notes J. G. A. Pollock (Reference Pollock1989, p. 17). In politics, the term ‘transition’ has a long trajectory: it was introduced by international actors who planned large-scale organisational changes conceptualised around the ideas of ‘democratic transition’ and ‘transitional justice’. In climate politics, the term ‘transition’ is frequently used as a shorthand for ‘energy transition’, ‘ecological transition’, or ‘green transition’. As discussed in more detail in Section 2, environmental historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz makes a convincing case for tracing the origin of the S-curve in energy politics from logistics and innovation economics. The political success and purchase of the term ‘transition’ are fascinating. In this first section, we problematise its polysemic use and prepare the ground for the critical examination of transition imaginaries that follows in the next sections.

A Brief Conceptual Genealogy

Even a cursory investigation into the term ‘transition’ shows that in the last fifty years, it has been employed to describe or explain social, economic, and political institutional changes. Indeed, the language of transition became central to institutional discourses in the 1990s (Aykut & Evrard, Reference Aykut and Evrard2017, pp. 18–19). With its focus on the transition to democracy, transitional justice, and transition to a liberal market economy, this paradigm has been popularised by international organisations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, well before the emphasis on energy transition. In the democratisation paradigm, the term ‘transition’ gave meaning and direction to regime crises and what would otherwise have been a period of deep uncertainty. After the fall of authoritarian regimes in South America and Southern Europe (Portugal, Spain, and Greece) in the 1970s, the democratisation literature flourished with scholars seeking to assess why democratic transitions succeed or fail. After the end of the Cold War, this literature gained a second wind, with (liberal) democracy promoted as the only ‘game in town’; armed with analytical and institutional frameworks, scholars attempted to explain the different waves of democratisation and why free trade capitalism was beneficial to democratic regimes (Clary, Reference Clary and Wiarda2010). During the last two decades, the world has witnessed regime changes, revolutions and restorations, and periods of democratic and authoritarian experimentation, questioning the straightforward narrative of a democratic transition. In attempting to write a history of these transitions, Cristiano Paixão and Massimo Meccarelli (Reference Paixão and Meccarelli2021, p. 2) note that if transitional justice is understood as ‘a single prescription – a uniform set of actions or reparations necessary in a post-dictatorship context’, the notion would be either ‘somewhat misleading … [or] almost useless for understanding the numerous processes for the shift from authoritarian regime to constitutional democracy’. Democratisation moves more like a pendulum rather than in waves.

This observation is relevant to the discussion on ecological transitions. Although transitioning to a new, ‘green’ phase in human history may sound like a novel idea, the vocabulary that permeates the discourse of green transition today has a long history. Indeed, its origins can be found in earlier discourses from the 1950s about demography transition, peak oil, and energy transition (Fressoz, Reference Fressoz2024; Smil, Reference Smil2010).Footnote 1 In the 1970s, it gained further traction as the solution to the ‘energy crisis’, with engineers, industry actors, and politicians in the United States appealing to a phasist energy history. This is famously depicted in an ‘Address to the Nation on Energy’ delivered by Jimmy Carter in 1977:

Twice in the last several hundred years, there has been a transition in how people use energy. The first was about 200 years ago when we changed away from wood – which had provided about 90 per cent of all fuel – to coal, which was much more efficient. This change became the basis of the Industrial Revolution. The second change occurred in this century, with the growing use of oil and natural gas.

The language of ‘energy transition’ was adopted in 1981 at the United Nations Conference on New and Renewable Sources of Energy in Nairobi and started dominating the global debate about energy (Basosi, Reference Basosi2020). More than forty years later, international politics has widely adopted this language of energy transition to discuss even issues unrelated to the environment and nature. This is captured well in the idea of ‘climatisation’ of global politics: a condition whereby ‘climate change is increasingly becoming the frame of reference for the mediation and hierarchisation of other global issues’ (Aykut & Maertens, Reference Aykut and Maertens2021, p. 502). In high-level policy and governmental responses to the climate crisis, ‘transition’ refers to the process of achieving a decarbonised world economy. In France, in 2017, under the Macron presidency, the Ministry of the Environment was renamed the Ministry of Ecological Transition; in 2022, a second Department was created, the Ministry of Energy Transition. Similarly, in 2018, the Spanish Ministry of the Environment was renamed the Ministry for the Ecological Transition (and then in 2020, the Ministry for the Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge). In 2021, at COP26 in Glasgow, the UK Government announced the creation of a Transition Plan Taskforce to develop the gold standard for private sector climate transition plans. This institutionalisation and formalisation of transition in public policy demonstrates the firm grip of the idea on political imagination. Evidently, ‘transition’ is a shorthand to describe changes in socio-economic systems aiming at low-carbon outcomes.

Academic scholarship on energy transitions has been growing rapidly in the last fifteen years, focusing primarily on socio-technical systems and the innovations required to decarbonise energy production, the cornerstone of the green transition in its mainstream manifestation. A notable concept emerging from the academic and policy debate on low-carbon transitions is ‘transition pathways’. This concept ‘underscores the multiple directions and processes of low-carbon change; interactions among technological, social, and natural dimensions; and cumulative choices spanning several decades’ (Rosenbloom et al., Reference Rosenbloom, Meadowcroft and Cashore2019, p. 172). This perspective integrates the literature on path dependence and historical institutionalism to imagine potential low-carbon transitions. The burgeoning field of ‘transition studies’ – led by scholars such as Frank W. Geels, Peter Newell and Benjamin K. Sovacool (Geels et al., Reference Geels, Sovacool, Schwanen and Sorrell2017) – focuses primarily on innovation and technological adoption. Using a complex lexicon to convey different scenarios and adjust parameters, these contributions take the discussion on the transition to a high level of abstraction (Fressoz, Reference Fressoz2024, pp. 29–30).Footnote 2 As Avelino (Reference Avelino2017) notes, power is frequently undervalued in the sustainability transitions literature, treating it instrumentally rather than an end in itself; yet, analysing power relations can help to approach critically the contradictions inherent in transition processes.

Another concept that has gained traction in agendas and practices of organisations on every level of governance today is the idea of ‘just transitions’. Grasped initially as a response to the resurgence of neoliberal globalisation calling to treat workers and communities affected by transitions in a just way, the just transition framework is multifaceted, covering different breadths, depths, and ambitions (Stevis, Reference Stevis2023). As a result, just transition is also highly contested as a framework for not addressing socioeconomic and environmental inequities. Stefania Barca (Reference Barca2020, p. 50) shows that the just transition framework reflects ‘a masculinist and Western-centric bias that persists in most large trade union confederations (even when women lead them), focusing on blue-collar jobs in heavy industry and infrastructures as the only sectors worth defending and “greening”, while downplaying the crucial contribution of agriculture, domestic and social reproduction work’. As Stevis (Reference Stevis2023, p. 59) clarifies, promises to ‘not leave anyone behind’ can obscure the politics of systemic change and blur the importance of local campaigns and struggles.

Another interesting manifestation of the term can be identified in the successful and well-known grassroots initiative of Transition Towns, which also contributed to the popularisation of the term in civil society. This citizen-led movement mainly focuses on energy independence, small-scale agriculture, and local food production. Co-founded in Totnes (UK) in 2007 by Rob Hopkins, an experienced permaculture teacher, and his former students Louise Rooney and Catherine Dunne, the Transition Network is a charity that aims to roll out transition principles to other towns around the UK and the world. Within a few years, the movement resulted in hundreds of hubs worldwide, thus challenging the idea of citizen apathy given climate change (North, Reference North2010; Urry, Reference Urry2011). The extraordinary spread of the movement can be attributed to its simple message of reclaiming community, skills, and resourcefulness. This message found fertile ground in the austerity conditions that the 2008 financial crisis created (Hopkins & Astruc, Reference Hopkins and Astruc2017). Transition Towns played an instrumental role in filling gaps in local services due to local authorities’ shrinking budgets following the 2008–2015 governmental austerity policies. Nonetheless, its emphasis on resilience bizarrely resonated with the austerity message of the ‘big society’ and the role played by volunteering in the collapse of the welfare state (Smith & Jones, Reference Smith and Jones2015). In any case, the movement’s use of the term ‘transition’ played a role in popularising (and localising) the notion that a socio-ecological transition is needed, making it central to local politics and citizen activism.

Overall, we observe that in its current use, whether referring to energy, sustainability, low-carbon, or socio-ecological transformations, ‘transition’ denotes a temporal and qualitative movement towards a greener future condition. Underpinning the term is a narrative that seeks to describe and evaluate our present moment: change is ongoing, and a new phase that is more ecologically sound will be reached. Transition is, therefore, a future-oriented term that seeks to define our contemporary condition as one in which everyone and everything should be mobilised in this journey towards genuine sustainability.

Contribution

The idea of transition is prominent in the Earth system governance scholarship on the planetary (Stevis & Felli, Reference Stevis and Felli2020), national (Morena et al., Reference Morena, Stevis and Shelton2018), and local (Berglund et al., Reference Berglund, Britton, Hatzisavvidou, Robbins and Shackleton2023) levels. This Element contributes to this flourishing field from a political theory perspective. Political theorists have made rich contributions to our understanding of the state’s role in ecological transitions (Eckersley, Reference Eckersley2021; Hatzisavvidou, Reference Hatzisavvidou2020), how sovereignty changes with a changing climate (Mann & Wainwright, Reference Mann and Wainwright2018), and the importance of expanding the concept of justice that underpins Earth system governance towards a direction that integrates more-than-human-natures (Celermajer et al., Reference Celermajer, Burke and Fishel2025). We contend that a political theory perspective on the study of transition politics can illuminate the conceptual and ideological pluralism that characterises this domain of politics by attending simultaneously to its normative and empirical aspects.

The starting point of this investigation is acknowledging that the idea of transition is used in polysemic ways. Behind the semblance of agreement are competing politics and power grab in the name of transition. To dispel misunderstandings, we do not reject the macropolitical project of the green transition or the energy transition. Like other critical transition studies scholars (Rosenbloom & Meadowcroft, Reference Rosenbloom and Meadowcroft2022; Sovacool, Reference Sovacool2021), we are interested in the effects of pursuing transition politics. Scholars such as Smil, Sovacool, and others frequently criticise transition based on the length of transition processes; these critics identify the problem with the transition’s technological and economic complexity, which prevents more rapid changes. Our approach differs in three ways. First, we do not critique the speed of transition but rather the epistemology that underpins the dominant transition vision and the politics through which it is advanced. Our project is a political theory of transition politics that draws on empirical developments to attend to the green transition’s ontological, epistemological, and cognitive aspects. Second, unlike scholars in transition studies who focus on the ‘meso-level’ of analysis (Köhler et al., Reference Köhler, Geels and Kern2019), namely that of socio-technical systems, we are concerned with the ‘macro-level’, the level where systemic changes are required. Third, we are interested in critically probing different transition visions. Even though the idea of transition is ubiquitous today in political rhetoric and the vocabulary of social organisations, businesses, and governments, we observe that there are different ways in which transitions to low-carbon futures are envisioned. This critical approach dispels the myth that environmental politics is a ‘valence issue’, namely an issue on which there is broad public agreement about desired policy outcomes and that, therefore, it is beyond contestation and disagreement. In developing a political theory of transition politics, we look at four elements: temporal and historical experiences of transitions, ecopolitical imaginaries of transitions, the affective dimension of transitions and finally, a decolonial transition that centres decolonial technology.

This Element has two aims. The first aim of Transition Imaginaries is to unearth the historical, normative, and political consequences deriving from using the green transition as a central tenet of climate politics. We demonstrate that the faith in ‘progress’ that permeates the mainstream transition vision harbours a form of delayism – the continuous postponement of meaningful socio-ecological change. Using materialist environmental history, we examine the assumptions that underpin and sustain the dominant transition narrative. We show that the attempt to mobilise people, materials, energies, and natures in the journey towards ‘real sustainability’ perpetuates the logic that informs what Walter Mignolo (Reference Mignolo2011) calls ‘the colonial matrix of power’. The second aim is to highlight the role of ecopolitical imaginaries in organising how transition is envisaged and advanced. Imaginaries are powerful political motifs, as political actors use them to produce shared meanings about the world, using cognitive schemes, cultural artefacts, metaphors, and narratives. Ecopolitical imaginaries also produce positive and negative affects, a vital issue we discuss at length in this Element.

Our overarching argument is that the currently hegemonic manifestation of transition politics is damaging in a triple sense: first, it hinders the realisation of forms of ecological politics that draw on marginalised philosophies of history and conceptions of time; second, it contributes to the development of sad affects through a disengaging technocratic and business-as-usual approach; and third, it results in further environmental damage in the present in the name of a greener future. Transition is a term often mobilised as the leading solution to the climate emergency; as such, it can function as a consensual term that depoliticises and smoothens forms of contestation. We concur with other scholars that a socio-ecological transition is imperative to ensure a sustainable and just future for everyone and everything. Our critique concerns the dominant transition paradigm rather than the idea of transition per se. The transition imaginaries we identify and analyse are the outcome of theoretical engagement with the unfolding conflicts we observe today in rhetoric, practices, and socio-material relations. Rather than systematically analysing transition plans and programmes, we offer a critical account of transition imaginaries.

This Element contributes to the current scholarship on Anthropocene politics and contemporary political theory more broadly by dissecting the variants of transition politics; highlighting the new conflict of temporalities; attending to the affective dimensions of the green transition; de-centring the role played by technological innovation. The Element, then, contributes to four contextual conditions of the Earth System Governance Research Framework (Earth System Governance Project, 2018, p. 48) – transformations, inequalities, Anthropocene, and diversity – by engaging with the current transition imaginaries as well as providing an alternative conceptualisation of transition, informed by a more diverse understanding of technology and temporality as well as marginalised forms of knowledge. The combination of our critical and decolonial approach builds on the diversity of the epistemological orientations of the ESG Research Framework (Earth System Governance Project, 2018, p. 38) to encompass views and cosmologies that go beyond Eurocentric accounts of knowledge production.

Outline

This Element is organised into four sections. In Section 2, we build on the work of the French environmental historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz (Reference Fressoz2024) and his genealogy of energy transition to examine the origins of the transition narrative. We take this idea further and argue that the vision of a post-carbon future reverberates both as a temporal order and as a knowledge system. Transition can be defined as ‘a black box that lies between the present and our idealised visions of the future’ (Heron & Dean, Reference Heron and Dean2022). This concept presents the temporal order of climate politics as brighter and linear, building from the modern regime of historicity (Hartog, Reference Hartog and Brown2015). This section concludes that the climate emergency has produced a new conflict of temporalities and historical experience.

Section 3 employs the notion of ecopolitical imaginary to dissect the ideological underpinnings and empirical manifestations of transition politics. Although it is undeniable that, in the descriptive sense, we are amid an unfolding transition to a planetary age, it is also crucial that the nuances and unequal outcomes of this process are also understood and interpreted in normative ways. To achieve this, we sketch five ecopolitical imaginaries through which transition politics gains cogency today: technocapitalist, eco-authoritarian, ecosocialist, post-growth, and ecoanarchist. We aim to demonstrate the ubiquity of transition politics while offering a nuanced analysis of its different manifestations and the damaging and beneficial effects produced on intellectual, affective, and material levels.

Section 4 draws on affective approaches to politics to explore and understand the epidemic of eco-anxiety today. Having examined transition imaginaries in Section 3, this section shows how affective attachments constitute and derive from an imaginary. The current preoccupation with the future, in terms of the sixth mass extinction or post-apocalyptic futures, produces sad affects such as eco-anxiety and grief. These sad affects diminish our power to act by dissociating people from the climate issue. Considering the ability of affects to augment or diminish our power to act, we point to the importance of infusing any alternative to the dominant transition paradigm with positive affects, such as joy and pleasure. We discuss the local experimentations of ZAD Notre-Dame-des-Landes as offering new positive attachments that counter the technocapitalist transition imaginary. We analyse these local experimentations as producers of joyful affects. Rather than serving as models of a utopian living, they function as images and produce affects, connecting to the structural and collective order.

Section 5 fleshes out the argument for a decolonial transition by focusing on the question of technology. We return to questions of temporality discussed in Section 1 and challenge the association of technology with anticipation. In the last section, we recover alternative conceptions of technology that exist today to displace the transition imaginary’s focus away from technologies typically associated with the dominant transition imaginary. In doing so, we turn to Bernard Stiegler’s philosophical work to sharpen our understanding of technology, its place in climate politics and its possible uses. Technology is often hailed as the ultimate and fitting solution to environmental degradation, energy systems, and sustainable living. We argue that there is no escape from technology; global climate change is a technological matter through and through. To show the problem of conceptualisation of technology, we turn to decolonial approaches to technology and two notable examples: the complex vernacular water harvesting techniques in Rajasthan, India, and the restoration of riverscapes by US environmental groups mimicking beaver dam activities. We conclude by sketching a decolonial transition imaginary.

2 Transition Politics and the New Conflict of Temporalities

The idea of a transition to a low-carbon future is ubiquitous in politics and public policy today, steering decision-making, industrial strategy, and financial investment towards solutions and projects that can contribute to implementing this ambitious idea. Three recent examples illustrate this omnipresence of transition in ecopolitics today: the European Green Deal (2020), Biden’s Green Industrial Policy (2022), and China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2020). Notwithstanding their differences in objectives, mechanisms, and deadlines, all these transition plans (which account for over half of the world economy) explicitly state a commitment to a single overarching goal: economic growth via a green transition.Footnote 3 On the national level, and in alignment with the Paris Agreement (2015), which introduced the goal to keep global warming well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, these plans reflect a ‘new’ growth strategy that aims to spur long-term economic growth fuelled by renewable energy sources. On the international level, not unlike the idea of ‘sustainable development’ (WCED, 1987), the green transition is today advanced as a universal goal that both the affluent Global North and the dispossessed Global South can pursue. In this sense, transition is a large-scale, universal project that attempts to speak to the needs and interests of all countries, irrespective of their past and present conditions.

The idea of a shared vision for humanity fits an era branded as the Anthropocene, the epoch of humans. What originally started as a debate between geologists very quickly captured the imagination of researchers in humanities and social sciences and even attained a broader cultural and political significance (Malhi, Reference Malhi2017). Although the diagnosis that it is the unifying category of anthropos that caused this change remains widely contested (see especially Bonneuil and Fressoz Reference Bonneuil and Fressoz2016; Haraway Reference Haraway2015; Moore Reference Moore2015), the advent of the Anthropocene on the conceptual and analytical levels marks an opportunity to reconsider the relationship between humanity and nature. As an event highlighting human-induced processes on the Earth, the Anthropocene creates opportunities for reflecting and acting upon the past and how human interventions, successes, and mistakes have shaped it. To the extent that modern ways of thinking have primarily informed such interventions, the Anthropocene marks an opportunity to reckon with them, to reconsider, confront, and revise them. It, therefore, calls into attention questions around epistemic injustice, the privileging of certain cosmologies over others, and the expropriation of earth materials in unequal and damaging ways.

Nonetheless, unproblematically advancing a concrete, monolithic vision for a green transition as a new common goal that ‘humanity’ – an undifferentiated agent that has collectively altered the Earth system – can jointly pursue overlooks these critical questions. Crucially, it misses the opportunity to reflect on the past and to respond to the injustices that marked it, with damaging effects manifesting in the present and anticipated in the future. The political use of transition is ‘ambivalent’ since it emphasises both the necessity of change and circumscriptions to protect the current political regime (Aykut & Evrard, Reference Aykut and Evrard2017, p. 19). Notably, the transition is, first and foremost, an argument about ordering time. As a political idea, it is underpinned by a particular understanding of temporality and our experience of it as humans via history. Yet, the transition also obscures the dramatic shift in historical experience; with the Anthropocene, there is an awareness of diachronicity and conflict of temporalities: the past, present and future are no longer organised according to the modern regime of historicity. As Andreas Malm (Reference Malm2018, p. 11) explains,

There is no synchronicity in climate change. Now more than ever, we inhabit the diachronic, the discordant, the inchoate: the fossil fuels hundreds of millions of years old, the mass combustion developed over the past two centuries, the extreme weather this has already generated, the journey towards a future that will be infinitely more extreme – unless something is done now – the tail of present emissions stretching into the distance … History has sprung alive through a nature that has done likewise.

Climate change results from deliberate, unjust, colonial, and criminal actions in the past. In the Anthropocene, the past is ever-present in the present; past actions haunt damaged and ruined landscapes. The future is either in peril or envisioned as a utopian territory composed of sustainable practices supported by green technologies.

Transition as a Hegemonic Idea

The idea of ‘transition’ as a policy, social, and economic goal is prevalent across different intellectual and political circles today; it is hegemonic. In this section, we outline this project’s origins and what it entails for the understanding of temporality in climate politics. Hegemony refers to the process and outcome of a social bloc’s efforts to secure domination and authority by integrating the interests of other social forces through a combination of consent and coercion (Gramsci, Reference Gramsci1971; Hall, Reference Hall1988). We purposefully use ‘hegemony’ here to call to attention the fact that what we discuss as green transition refers to the specific form that transition politics has taken today as a policy paradigm. Despite the semblance of agreement on the idea of a transition to a low-carbon future, this hegemony is contested by other ecopolitical imaginaries (Sections 3 and 5). On the international policymaking level, the green transition is presented as a strategic set of policy instruments that aim to curtail carbon emissions fast enough to prevent global temperatures from transgressing the dangerous threshold of 2°C above pre-industrial levels.Footnote 4 With the horizon of action to achieve this goal set until 2050 or 2060, the green transition includes ambitious plans to decarbonise all aspects of economic activity in energy, land use, industry, buildings, and transport. A central characteristic of the transition as a hegemonic idea is what Breno Bringel and Maristella Svampa (Reference Bringel and Svampa2023) call the ‘decarbonisation consensus’: a ‘new global agreement’ that promotes a carbon-free energy system based on electrification and digitisation and contributes to the exacerbation of environmental destruction and socioeconomic inequalities. In addition to this decarbonisation consensus, the green transition expresses a particular way of getting there. It implies thinking about temporality, history, and the role of humans as agents of all change on Earth. Bringing together the dominant Western-centred cosmology and the systems of knowledge associated with it, along with the institutional power accumulated on the level of global governance of the Earth system, the vision of a transition to a low-carbon world is projected as a widely accepted, jointly pursued goal.

Seemingly, the aspiration is to transform all aspects of social life radically towards more sustainable directions; in reality, the green transition is, first and foremost, an example of the economisation of life, a process theorised and well documented by Murphy (Reference Murphy2017). Take the example of the EU Green Deal. This ambitious policy package aspires to ‘transform the EU into a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy’ in which ‘economic growth is decoupled from resource use’ while ‘reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels’, ultimately ensuring that by 2050 there will be no net emissions of greenhouse gases (Murphy, Reference Murphy2017). Although it is presented as a holistic plan aiming to transform all domains of human activity and nature (air, soil, water, and biodiversity), the Green Deal is primarily a policy package to transition to a carbon-neutral economy. This is evidenced by the kind of directives, mechanisms, and instruments through which the Green Deal is delivered.

Yet, its proponents mobilise arguments beyond the economic sphere to acquire a hegemonic status and coalesce different social forces around the green transition. This is why the green transition is frequently presented as a social programme that aims to ‘improve the well-being and health of citizens and future generations’ (EU Green Deal) and to be ‘the largest investment ever in combatting the existential crisis of climate change’ while lowering prescription drug costs, health care costs, and energy costs (US Inflation Reduction Act). It is a vision for an improved society where everyone can reap the benefits of the growing economy. Advanced through ‘win-win’ rhetoric, which presents a particular form of transition to a low-carbon economy as the most beneficial scenario for our climate-changed world, the idea of transition has taken up most of the space of ecological politics on the public policy level in many of the world’s largest economies. Despite its seemingly novel, neutral, and consensual character, the green transition is the latest addition to the grand narratives of progress, development, and growth (Escobar, Reference Escobar2015; Kothari et al., Reference Kothari, Salleh, Escobar, Demaria and Acosta2019). These three processes have marked the history of modernity comprising the goal of what Walter D. Mignolo (Reference Mignolo2011) calls ‘the colonial matrix of power’: a structure that, in reality, includes not only these goals but also coloniality, manifesting through poverty, injustices, and corruption. The reality of climate coloniality is today unfolding ‘where Eurocentric hegemony, neocolonialism, racial capitalism, uneven consumption, and military domination are co-constitutive of climate impacts experienced by variously racialised populations who are disproportionately made vulnerable and disposable’ (Sultana, Reference Sultana2022, p. 4).

It is essential to acknowledge that the idea of an energy transition is not novel; it is well embedded within a broader narrative of humanity’s common journey on Earth. It is even composed of smaller competing narratives upheld by different public actors that emphasise either sustainable energy or decarbonised energy (therefore including nuclear energy) (Aykut & Evrard, Reference Aykut and Evrard2017, p. 31). Low-carbon transformations require investments over generations, and historical studies are crucial to understanding the weight of history in politics. While the genealogy of transition as an idea does not predetermine its current manifestations in governmental policy, political actors constantly mobilise history, as demonstrated by Fressoz and others. In his last book, environmental historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz examines the origin of the energy transition in the post-WWII United States to understand why it has become a dominant frame of reference in different domains of politics and not just in environmental policies. Fressoz’s genealogy of the concept of ‘energy transition’ finds that the timeline of the transition narrative follows ‘a “phasist” perception of energy’ (Fressoz, Reference Fressoz2022, p. 116). According to this logic, the history of energy production and consumption is represented as a series of phases and transitions. More specifically, in the 1950s and 1960s, the narrators of these transition ‘histories’ appealed to common sense and naturalised transitions. They argued that humanity had already experienced two transitions: from wood to coal and from coal to oil. The point was to prepare for the next transition: from oil to nuclear energy. Fressoz shows the limitations of this phasist interpretation of the history of energy production and consumption. He contends that we should shift perspective: from a phasist understanding of the history of energy (and its focus on ‘transition’) to an accumulative understanding (Fressoz, Reference Fressoz2020).Footnote 5 As he explains, historically, ‘sources of energy are as much part of a symbiosis as a competition’ (Fressoz, Reference Fressoz2022, p. 116). For instance, the ‘transition’ from wood to coal involved more global wood use (in coal extraction). Similarly, coal consumption increased only when oil became a central energy source for industrialised economies, necessitating new networks to enable oil extraction, refinement, transportation, and distribution. An accumulative interpretation of the history of energy, rather than a phasist one, emphasises dynamic understanding of past transformations rather than mere transitions. This shift from viewing history of matter as a succession of material phases to a more complex process whereby different intellectual, material, and political forces intermesh opens the way for a comprehensive understanding of transition. Knowledge and material production are more interconnected than a phasist historiography allows it. An approach that considers both the material and the intellectual aspects underpinning the green transition illuminates how it guides ecopolitical decisions and practices today, leading to a delayed meaningful action. Additionally, such an integrated approach encourages the consideration of the devastating impacts of the green transition on racialised and impoverished people and their ecosystems. As Cara New Daggett (Reference Daggett2018) notes, energy and work have always been intertwined, and the green transition attempts to conceal the power dynamics inherent in energy production and consumption.

Fressoz’s genealogy shows that the energy transition is neither historically novel nor intellectually groundbreaking. Its origins can be traced back to various sources: the atomic energy lobby, neo-Malthusians concerned about birth control, the influential ‘peak oil’ hypothesis, and the application of the logistic model (or S-curve) to the evolution of global energy mix. The energy transition narrative is a patchwork of disparate futurologies, each presenting a unique perspective on the future. These perspectives are driven by a commitment to preventing a catastrophe (a fossil fuel-free future). Fressoz concludes that in reusing and reproducing this transition framework in response to the current ecological crisis, we are perpetuating a ‘fake history built on recomforting illusion’ of energy transition and a ‘phantom future’ (Fressoz, Reference Fressoz2022, p. 145).

Fressoz’s arguments will likely be debated for years to come, and some early criticisms and correctives are worth noting. For instance, Adam Tooze (Reference Tooze2025) rightly notes that Fressoz’s genealogy remains centred around Anglo-American economies and neglects the significant rise in global emissions from East Asian economies from the 1990s, mainly due to the prominence of steel production and shipbuilding. Pierre Charbonnier (Reference Charbonnier2024) expresses concerns about the normative implications of Fressoz’s laser-sharp empirical work in crafting a properly materialist history of energy. The book’s ambiguities lie in its lack of discussion of degrowth as an alternative path to the green transition, which Charbonnier suggests could lead to resignation or fatalism in the face of the magnitude of the climate emergency. This sentiment was echoed by a collective of social scientists writing in Le Monde shortly after the book’s release (Creti et al., Reference Creti, Criqui and Derdevet2024). As with any book, interpretations and receptions vary, highlighting the significance of Fressoz’s ideas and the need to expand upon them. Fressoz’s sobering perspective on the absence of an actual transition can indeed be read in a pessimistic and anxiety-inducing way, a point we delve into in greater detail in Section 4.

Building on Fressoz’s conclusion, we extend the discussion beyond energy transitions to encompass transition politics. This involves forms of collective organisation and arrangement of bodies, materials, and natures necessary for transitioning to a decarbonised future. We argue that the post-carbon narrative, which is one of the transition narratives (Aykut & Evrard, Reference Aykut and Evrard2017), manifests as a philosophy of history (as a way of understanding history) and as a politics (a way of organising societies and natures) through which transition is materialised. We discuss these in turn next: taken together, these two components illuminate the multiple layers to which the idea of transition manifests and can be linked.

The Temporal Order of Transition

While the histories of energy transitions are materially inaccurate, they still have socio-political effects. Reinhardt Koselleck’s concept of historical experience provides insight into how the idea of green transition has shaped how humans experience temporality. Koselleck (Reference Koselleck2018) explains that a defining characteristic of modernity was the acceleration of human time perception, which was associated with the invention of clocks and railways. This acceleration led to the ‘denaturalisation of time’ (Koselleck, Reference Koselleck2018, p. 82; 85–91); as transportation became no longer limited by human or horsepower, or even wind and rain, but rather amplified greatly by machines and steam power. With modernity, the articulation of past, present, and future changed, driven by an impatience for progress and revolution. We observe that the ecological crisis has now opened a new conflict of temporalities, pitting human temporality against geological time, also known ‘anthropocenic time’, ‘climate change temporality’ (Simon & Tamm, Reference Simon and Tamm2023), or ‘deep time’ (Hanusch, Reference Hanusch2024). These different terminologies mobilised by authors include different parameters and scopes, primarily focusing on biophysical processes or incorporating human experience.

The paradox of transition politics lies in its ability to mobilise a modern experience of time for a historical period where revolution and progress are no longer operative as historical categories. This historical period is often characterised as ‘presentism’ (Hartog, Reference Hartog and Brown2015), a long and repetitive experience of the now. The Anthropocene and the recent large-scale collective consciousness of the climate crisis have disrupted the modern ‘regime of historicity’, giving rise to a new one, the anthropocenic or climate change temporalities (Nordbland, Reference Nordbland2021). In the modern regime of historicity, the future appeared as a telos, and the idea of progress became central, providing justification for various doctrines, both eschatological and secular. The Age of Reason and Enlightenment, along with scientific discoveries and modern science, were powerful motifs that reinforced this modern regime of historicity. As Hartog explains, the concept of ‘presentism’ accounts for the transformation of historical experience caused by the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the end of the USSR. With the end of the real-existing communism, people’s experience of political and historical alternatives vanished, and the present became the immanent and limitless reservoir of historical experience. Real-existing capitalism constructed the regime of ‘presentism’, the temporality of capital that seeks to subsume all forms of life and temporalities.

In recognising the existence of climate change and the role of humans as a geological force, a new conflict of temporalities and historical experience has emerged. Although Hartog considers the emergence of an ecological consciousness in terms of the regime of historicity, he hesitates to give it a new name. He uses the expression ‘apocalypse in slow motion’ (Hartog, Reference Hartog and Gilbert2022, p. 82) to conceptualise the reconfiguration of the past-present-future schema in the age of the climate crisis. The recent rise of eco-anxiety (Section 4) is partly linked to this new conflict of temporalities:

There is fear at times that are approaching too fast (the looming prospect of tipping points), and deep frustration at other times that are both too short and too slow (the short-termism and political delays of electoral democracy); there is sadness and nostalgia at times that are now out of reach (the future is already gone).

We concur with Louise Knops that the perception of the looming tipping points is central to this new regime of historicity. Unlike the modern regime of historicity that hailed the future as a brighter and more prosperous period to come, the ‘apocalypse in slow motion’ represents a new form of shared historical experience in which the present effectively burns the future. Unlike presentism, in which the future is a mere continuation of the limitless present, in the Anthropocenic regime of historicity, a new and negative image of the future emerges. The future is not only worse than the present, but it is deteriorating even more. The unfolding of the biodiversity extinction and the extreme weather systems feed this image of a burning future. There are different ways of describing this new form of historical experience. Some talk about ‘pre-traumatic stress syndrome’ (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan2020; Mihai & Thaler, Reference Mihai and Thaler2023), a fear of a future event that is already causing wounds in the present. Contrary to other environmental mental health disorders, such as ecosickness or ecophobia, pre-traumatic stress syndrome is a temporal notion based on an anticipation of a catastrophic future, partly created and sustained by dystopian films and fiction.

Interestingly, transition belongs to the modern regime of historicity, one in which the future gives sense to both the past and the present. Transition denotes a dynamic process with specific temporal and qualitative connotations, designating a shift from a carbon-intensive present towards a decarbonised, healthier, or, in other ways, improved future. Indeed, it affirms and validates change as a linear process: a more ecologically sound phase will be reached in the future if appropriate action is taken in the present. The temporal order underpinning transition defines the contemporary condition in a way that seeks to mobilise people, materials, energies, and natures in the journey towards ‘real sustainability’ with two effects: first, it perpetuates the logic of coloniality that informs the colonial matrix of power; second, it generates a ‘passive present’ (Danowski & De Castro, Reference Danowski and De Castro2017) thus foreclosing political possibilities and creating negative affects. As a future-oriented process, transition draws on linear perceptions of time advanced by settler colonialism and the forms of knowledge it privileges (Rifkin, Reference Rifkin2017). In this sense, the transition vision shares epistemological ground with the Western-centric understanding of modernity produced in an exploitative centre (Europe) that prospered by impoverishing an abundant periphery (Global South) on both material and cognitive levels. In sharing this ground, the transition vision reproduces the epistemic injustices that characterise the system of knowledge that Mignolo (Reference Mignolo2011) calls ‘the Western code’, which was advanced through the colonisation not only of lands but also of time:

‘time’ is a fundamental concept in building the imaginary of the modern/colonial world and an instrument for both controlling knowledge and advancing a vision of society based on progress and development.

The implementation and success of modernity and its associated economic, political, and social projects required the moulding of time. The ecological crisis is yet another instance in history when time is controlled not only in the name of progress, development, and growth as has been historically done, but also in the name of human civilisation’s survival. It is, therefore, not sufficient to examine transition politics as a mere continuation of the project of modernity. The phasist dimension of transition renews the project of modernity itself.

This is why it matters how the idea of a transition to a low-carbon future is narrated: what temporal orders are employed (a topic discussed in this section), what kind of imaginaries arise within it (a topic we discuss in the next section), who is seen as the agent of history driving this transition, and what are the material and affective impacts that this transition has (topics discussed throughout this Element). At stake on the intellectual level here is avoiding the repetition of a mistake that those who have narrated similar stories in the past have made: failing to consider the biophysical state of the Earth system. This mistake was explained in an exchange between Bruno Latour and Dipesh Chakrabarty, who discussed how predominant philosophies of history have traditionally overlooked the role of the Earth system as an agent of history. Latour proposes that historians studying the present have failed to account for the role of the Earth in human history due to an ‘excess of “moral clarity”’. This resulted in philosophies of history that were ‘blind themselves by the idea of a goal-oriented history’, which in turn ‘has triggered a form of (in)volutionary ignorance about the real state of the Earth’ (Latour & Chakrabarty, Reference Latour and Chakrabarty2020, pp. 423–427).Footnote 6 Latour’s diagnosis is invaluable because it makes blatantly clear the fact that although the first signs of the ecological crisis were already evident from the 1980s, modernist philosophies of history failed to account for it.

Equally invaluable, though, is Chakrabarty’s counterargument: it was not an excess of ‘moral clarity’ of the West that prevented historians from grasping what he calls ‘the planetary’ (the equivalent to Latour’s Gaia) in human history. As Chakrabarty explains (Latour & Chakrabarty, Reference Latour and Chakrabarty2020, p. 451), ‘postcolonial thought – for all its critique of the nation-state and race-class formations – was also just as environmentally blind as anti-colonial nationalism.’ For Chakrabarty, the planetary became the blind spot of historians because of the dividing line separating postcolonial thinkers and those embedded in Western epistemologies and ontologies, which entails that they have been preoccupied with different problems and questions. This lack of common ground can be remedied – albeit only in a patchy way using ‘band-aids’ as he suggests – if geological time is brought into historical time. This would entail considering the Anthropocene not simply as a geological process but as an epoch that forces a novel process of historicisation that bridges the hitherto distinct regions of knowledge, philosophy of history and philosophy of nature.

The idea that the green transition is the definitive action that will insulate humanity from the vicissitudes that the advent of the Anthropocene brings by ensuring that an ecological catastrophe will be averted exemplifies the kind of philosophy of history critically discussed by Latour and Chakrabarty. As an attempt to organise disparate events into a coherent whole and narrate them as a teleological story, it is a repetition of the mistake identified in their critical exchange. Despite seemingly an attempt to fold ‘the planetary’ into human attempts to govern nature, the green transition narrative functions as a grand narrative of human progress that advances towards a firmly defined telos (a decarbonised society); it thus displays the shortcomings of all philosophies of history identified by Latour. Mistaken by ‘the idea of a goal-oriented history’ (Latour & Chakrabarty, Reference Latour and Chakrabarty2020, p. 427), the green transition vision ignores the reality of biophysical limits, advancing ‘technofixes’ that, if pursued at the proposed scale, would contribute to the transgression of critical planetary boundaries (International Energy Agency 2022; Dillet & Hatzisavvidou, Reference Dillet and Hatzisavvidou2022). This mistake also leaves the idea of transition insensitive to the vicissitudes of those who are called to shoulder the environmental, health, and social costs of the extraction projects linked to transition, an aspect that we discuss more fully next. With its emphasis on a future affirmed as a horizon of anticipation, an endpoint that humanity as a unified agent marches towards, the idea of transition not only misses the geospatial dimension that Latour and Chakrabarty’s exchange illuminates but also fails to pay attention to the pluralism of temporalities embraced by different societies and communities that are called to endorse and pursue the transition vision.

In contrast to this discussion, in Section 5, we turn to decolonial approaches to technology and time as alternatives to the dominant and modernist transition narrative. Indeed, not everyone in the world lives or aspires to live in the same temporality. Drawing from his work on and with the Zapatistas in Mexico, Jérôme Baschet (Reference 67Baschet2022, p. 201) shows the significance of cyclical temporality of the indigenous communities alongside the modern and presentist regimes of temporality. In engaging with alternative understandings of temporality, we illuminate how counter-hegemonic views of time and technology also point to alternative transition imaginaries.

Transition Politics

The temporal order that infuses and sustains the dominant transition imaginary offers a one-sided, uniform, and totalising account of human history in the era of unprecedented anthropogenic climate change. When the temporal logic of transition is placed within a broader epistemological context, the green transition is an episode in the long history of modernity and the colonial matrix power. Functioning through a series of coordinated actions that resulted in yet-to-be-repaired epistemic injustices, the cognitive empire invaded the mental universe of the colonised, framing their ontological commitments and colonising their epistemological processes in ways that enabled capitalist extractivist and political subordination (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Reference Ndlovu-Gatsheni2021).Footnote 7 As argued in Mignolo’s quote earlier, time was a key reference point in the process of colonising people’s mental and affective processes; it was also central in the re-organisation of life around markets, money, and ‘the economy’, a re-organisation that required not only a way to measure and evaluate time but also the homogenisation of time so that it could be used as a resource.

In its dominant conceptualisation, the green transition is organised in a homogenous temporal framework that overwrites any differing way of appreciating time, thus erasing the pluralism of existing temporalities from policy planning. This is patently clear in the transition plans through which transition politics gains cogency. This is a politics comprising a series of practices, such as legislations, policies, and investments that aim at implementing the transition to a decarbonised society and economy within a specified timeframe – 2030 (e.g. EU), 2050 (e.g. the United States), or 2060 (e.g. China), depending on the ambition and perceived responsibility of each climate actor. Even in its most statist and bureaucratised version as ‘ecological planning’, the idea that the future can be constructed remains central. These sets of practices make up transition politics, the essence of which is exhausted in achieving ‘carbon neutrality’ by the set timescale at all costs. Although the transition timescales carry the authority of science, as they are the product of complex, collaborative research practices, they are far from ‘neutral’ or ‘objective’ depictions of reality. As important work in science and technology studies shows, time is co-produced with social arrangements, political order, and technoscientific advances (Marquardt & Delina, Reference Marquardt and Delina2021). The timescales of decarbonisation are not simply the outcome of powerful calculations by neutral computer models; they reflect political and economic priorities, deep ideological commitments, and funding choices. They integrate, in other words, views on what kind of knowledge matters and what kind of social and economic orders are envisioned. Transition politics is a mechanism for organising societies, natures, affects, and resources in the present so that the Earth’s atmosphere contains fewer greenhouse gases in the future. It is a future-oriented politics that, in its unfolding, may cause irreparable damage to landscapes and historically marginalised, impoverished, and racialised communities through extraction and homogenisation. To prevent this damage, transition politics should take a justice approach, a variant of which we outline in Section 5.

In its currently hegemonic manifestation, transition politics takes the form of ambient Prometheanism, the doctrine that ‘advocates humanity’s ability to confront the ecological crisis through costly technological interventions fuelled by intensified economisation’ (Dillet & Hatzisavvidou, Reference Dillet and Hatzisavvidou2022, 352). By centring all environmental action around ‘carbon neutrality’, pursued through intensified financial activity, industrial strategies that aim to foster economic growth, and technological innovation funded by Big Tech, the green transition advances the unique role that capitalism has long now attributed to technoscience and markets as the vehicle to human well-being. In 2024, many Silicon Valley companies dropped their net-zero pledges due to building new energy-intensive infrastructures (data centres, small nuclear plants) to support the growing demand for Artificial Intelligence (AI) models. At its most extreme, former Google CEO Eric Schmidt admitted that ‘we are never going to meet the climate goals anyway’, suggesting we should let AI ‘solve the problem’ (Niemeyer & Varanasi, Reference Niemeyer and Varanasi2024) as if it is a problem too great for human intelligence and its resolving requires immense energy and computing power. By intensifying the destruction of Earth’s resources and exacerbating existing socio-economic inequalities between and within countries of the Global North and the Global South, the green transition further economises global environmental change, making it simply a frontier of financialisation and investment. It is a form of necropolitics (Mbembe, Reference Mbembe2019) that dictates who must live and how to achieve ‘climate neutrality’. Ultimately, it contributes to the depoliticisation of climate change by promoting a seemingly benign mega-project that humanity can universally embrace and pursue.

As an epistemic project, the green transition requires and is materialised through the homogenising control of knowledge production in the present so that ecological catastrophe can be averted in the future. Whereas in modernity, science was used to justify the imposition of a unified way to ‘objectively measure’ time, now it is used to justify the temporal regime of transition politics. As a political project, the green transition concerns the continuation of the vision of economic growth through the complete redesign of the equipment (labour and technology) necessary for its implementation. The problem with the green transition as an epistemic and political project is that it relies on the assumption that because there are universal needs, there is also a single way to address them and, therefore, a particular kind of knowledge (‘a universal epistemic code’, as Mignolo puts it) that can be employed to move us to a pre-defined and programmed future. As a result, it is not only ‘nature and the universe [that are] subjected to time’s arrow, or linear time’ (Mignolo, Reference Mignolo2011, p. 170) anymore; it is also the livelihoods and landscapes with which some communities live that are subjected to a logic that aims at a universal goal. In celebrating growth and development and masking injustice and destruction, this project erases or devalues certain forms of knowledge and local histories.

This reckoning with the knowledge systems and temporality orders that inform ecopolitics matters. An alternative to the unfolding transition politics would be a politics that offers space for plural temporalities and addresses epistemic and political injustices. This could include an understanding of time not linked to the utilitarian logic of economic power and a conceptualisation of time beyond the present time or what Indigenous scholar and community leader Ailton Krenan calls ‘un tempo alem desse’. Progress, the notion that we are going somewhere, is based on seeing time as an arrow – always going somewhere. As Krenak (Reference Krenak2023, p. 36) argues, this is the basis of our deception. The value that a more pluralistic account of time brings is that it allows us to consider the re-creation of the world as always a possible event. We visit this argument more explicitly in the final section, where we engage with Krenak’s proposition for the ‘existence of the Earth as an active event, here and now’.

We contend that to envision more equitable futures on a climate-changed planet, it is essential to undo the homogenising temporal framework that underpins transition politics. This undoing cannot be realised without considering the mistakes of the past. In this section, we examined the temporal and historical dimensions of the green transition. This is a temporal notion that requires appreciation of the new conflict of temporalities opened by the ecological crisis. Whether formulated in terms of regimes of historicity or in geological time, anthropocenic time or even deep time, scholars point to the co-existence of multiple temporalities. In the next section, we turn to five imaginaries (technocapitalist, eco-authoritarian, ecosocialist, post-growth, and ecoanarchist) to study in detail their visions of transition and, therefore, of the future. While transition seems to describe a universal, widely shared vision, we show that each ecopolitical imaginary puts forward its version of transition pathways and transition endpoints.

3 Ecopolitical Imaginaries of Transition

Transition politics is not monolithic or uniform; it also does not fit within a single ideological frame. As discussed in this section, advocates of transition politics subscribe to different political and ideological viewpoints, envision disparate and often competing ecopolitical futures, and prioritise divergent and sometimes irreconcilable material arrangements. However, a shared dilemma is implicated in the various forms of transition politics: either transition to a decarbonised future or maintain the current fossil fuel-based societies, leading to ecological collapse. This dilemma functions not only as a form of political but also of emotional blackmail, as we further discuss in Section 4. The logic of anticipation or pre-emption is imbricated in transition politics in all its manifestations: the transition is a mechanism to pre-empt and control the future. As Anaïs Nony (Reference Nony2017, p. 102) notes:

pre-emption is the appropriation of something before it emerges as a common opportunity. … As a temporal logic, it refers to a situation where one opportunity is predicted to benefit some people over others.

The kind of anticipatory thinking (pre-emption) that informs transition politics relies on a linear understanding of temporality that, as discussed in the previous section, reduces ecological politics to a set of actions and policies that concern the future, for the benefit of some people over others. In the final section we discuss how an environmentally and socially just transition would be informed by multiple temporalities.

We contend that the assumptions underpinning and sustaining transition politics require a more systematic probing, both on the descriptive and the normative level. Although it is undeniable that we are amid an unfolding transition to a different ecological state (in a descriptive sense), the nuances and unequal outcomes of the attempt to manage this process must also be understood and interpreted in normative ways. In this section, we elaborate on the different ideological underpinnings of transition politics, assessing the conditions under which it takes an ambient Promethean character and preparing the ground for discussing its affective dimensions (Section 4). As discussed in Section 1, given the climatisation of politics, we propose that transition politics emerges as the overarching form of ecopolitics.Footnote 8 Nonetheless, when observed closer, as we endeavour in this section, transition politics takes various forms that may depart from hegemonic articulations of transition outlined in Section 2. In observing how the transition to low-carbon futures is envisioned today, we tease out how the imperative of transition justifies and legitimises policy priorities, technoscientific knowledge production, and intensified financialisation. The overarching point we make is that the idea of goal-oriented ecological politics and its associated preoccupation with anticipation and the future has created complacency about the state of the planet in the present; it has also led to erasing from public memory past mistakes that contributed to the current state of affairs while silencing the perspectives of those already marginalised in these debates. As Latour (Reference Latour and Chakrabarty2020, p. 426) observes, it is precisely ideas such as ‘going somewhere’, ‘moving forward’ or ‘leaving the past behind’ ‘that ‘cut one by one all the roots of reflexivity’. We concur and add that it is also these ideas – linked to ‘progress’ – that devastated the lives of Indigenous people and the nonhumans that that they consider part of their associated milieu. Counteracting these ideas is our purpose in the final section of this project.

Ecopolitical Imaginaries

In dissecting the various forms of transition politics, we employ the notion of imaginary. Following others who also argue for the crucial social role that imaginaries perform (Bottici, Reference Bottici2011; Castoriadis, Reference Castoriadis and Blamey1997; Jasanoff & Kim, Reference Jasanoff and Kim2009; Taylor, Reference Taylor2004), we see them as valuable clusters of social meaning that inform expectations, affects, and desires, shaping practices and decisions. Ecopolitical imaginaries are collective visions for sustainable futures created through collaboration between different ecopolitical actors and express the ideas inscribed in people’s imagination and material artefacts, from policies and institutions to technologies and novels, thus enabling meaningful interaction (Hatzisavvidou, Reference Hatzisavvidou2024, Reference Hatzisavvidou, Machin and Wissenburg2025). Ecopolitical imaginaries are a useful heuristic to think about shared understandings of ecopolitical reality. They clarify how particular visions of the future gain prominence in public discourse and policy and how alternative viewpoints contest them. Though there are points of intersections and similarities, ecopolitical imaginaries differ from political ideologies. Like ideologies, they also work as ‘mental frameworks’ (Hall, Reference Hall1998) that guide collective sense-making; however, imaginaries are not concrete ideational blocks, as different ideologies may inform them. Instead, they are clusters of co-produced social meaning that contain idealised visions for the future that evoke specific affects. This aspect of imaginaries is explored in more detail in Section 4.

Other researchers have previously identified specific imaginaries that organise social meaning and transformative action regarding climate change (Celermajer, Reference Celermajer2021; Levy & Spicer, Reference Levy and Spicer2013; Machin, Reference Machin2022). Following the approach of these researchers, we delineate imaginaries that emerge in academic texts, policy documents, and broader public discourse, which we have used as sources for our analysis. Rather than dissecting specific policies and plans, we outline the imaginaries that could implement them. Our discussion primarily concerns how different ecopolitical actors (policymakers, academics, activists, movements) envision the transition to sustainable futures. By attending to ecopolitical imaginaries, we consider the intersection of the political and the ecological, as well as the temporal and the affective. This approach allows us to move beyond the vague notion of ‘transition’, which is often used by political actors with varying and even competing ecopolitical projects. We explore the different political trajectories and visions associated with this notion. More specifically, we are interested in how the different imaginaries we identify affirm agency, temporality, technology, and envisioned outcomes; we are particularly interested in when and how the future becomes the raison d’être for damaging, extractive and exploitative forms of action in the present.

Ecopolitical imaginaries can play a vital role in responding to what Carl Death (Reference Death2022, p. 444) calls ‘the depoliticised, global, linear, and anthropocentric framing’ of hegemonic manifestations of ecological politics. As our analysis clarifies, transition politics takes manifold forms; despite the current predominance of one particular imaginary, this is contested by other imaginaries. Alternative ecopolitical imaginaries do not only offer entry points for critique and departure from hegemonic framings; they also provide images and affective sources that help us see that it is ‘always possible to picture things otherwise and to envisage alternative social relations’ (Death, Reference Death2022, p. 437). In this sense, they are valuable sources for envisioning ecopolitical futures through action that unfolds in the present to shape the future; alternative ecopolitical imaginaries can function as compasses for navigating radically transformative possibilities. Importantly, as we discuss, they engage multifariously with temporality and the affective dimension of politics. This is why we find the analytical category of ‘imaginaries’ so central to our analysis: it allows us to consider the temporal and affective aspects of politics and the contestation that emerges among different ecopolitical agents.

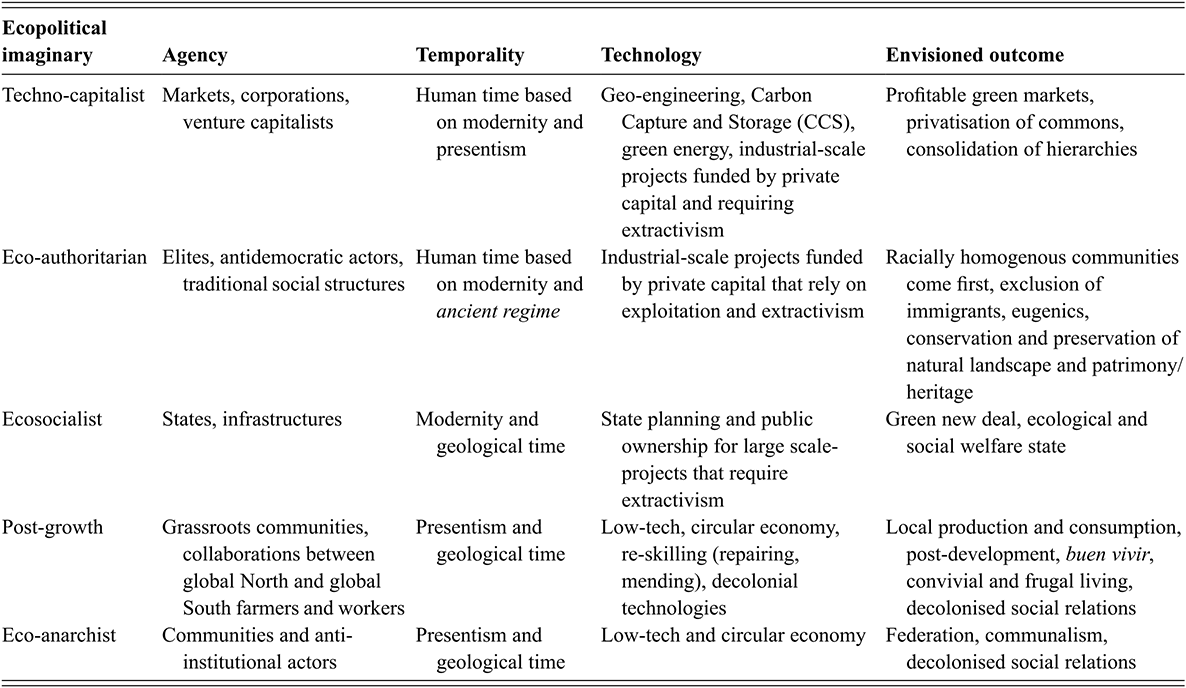

In our discussion, we sketch five ecopolitical imaginaries through which transition politics gains cogency today: the predominant techno-capitalist and four emerging alternatives, eco-authoritarian, ecosocialist, post-growth, and eco-anarchist (Table 1).

| Ecopolitical imaginary | Agency | Temporality | Technology | Envisioned outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Techno-capitalist | Markets, corporations, venture capitalists | Human time based on modernity and presentism | Geo-engineering, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), green energy, industrial-scale projects funded by private capital and requiring extractivism | Profitable green markets, privatisation of commons, consolidation of hierarchies |

| Eco-authoritarian | Elites, antidemocratic actors, traditional social structures | Human time based on modernity and ancient regime | Industrial-scale projects funded by private capital that rely on exploitation and extractivism | Racially homogenous communities come first, exclusion of immigrants, eugenics, conservation and preservation of natural landscape and patrimony/heritage |

| Ecosocialist | States, infrastructures | Modernity and geological time | State planning and public ownership for large scale-projects that require extractivism | Green new deal, ecological and social welfare state |

| Post-growth | Grassroots communities, collaborations between global North and global South farmers and workers | Presentism and geological time | Low-tech, circular economy, re-skilling (repairing, mending), decolonial technologies | Local production and consumption, post-development, buen vivir, convivial and frugal living, decolonised social relations |

| Eco-anarchist | Communities and anti-institutional actors | Presentism and geological time | Low-tech and circular economy | Federation, communalism, decolonised social relations |

Our taxonomical approach identify five imaginaries, it does not suggest they exhaust our ecopolitical condition or imagination. Reality is too complex and multi-layered to fit into neat analytical ‘boxes’.Footnote 9 Table 1 is a way to offer an overview of how agency (who enacts and pursues the imaginary), temporality (what temporal order is employed), technology (how this is pursued), and envisioned outcomes for each of the five ecopolitical imaginaries we discuss. This does not capture all the possible ways that transition is envisioned today; instead, it demonstrates the diverse vantage points from which transition politics is supported and argued for and, therefore, to illustrate the significance of articulating and pursuing a sixth ecopolitical imaginary for a transition to just sustainable futures (which we attend to in Section 5). We purposefully analyse these imaginaries because we see them shaping the public debate (which unfolds on the political and academic levels) on the green transition today. By dissecting these divergent imaginaries, we highlight and attend to the diversity of transition politics without claiming that we offer an exhaustive analysis of ecopolitical imaginaries, past and present. Indeed, we would welcome future research that adds to the imaginaries we identify. We see this approach as a way to dispel the myth that environmental politics is a ‘valence issue’, namely an issue on which there is broad public agreement about desired policy outcomes and that is beyond contestation and disagreement. Our approach clarifies a second point: that environmental politics is inherently democratic or progressive. Indeed, as the following discussion shows, the climatisation of politics means abandoning our inclination to associate de facto and de jure green politics with left politics.

The Technocapitalist Imaginary

Industrial-scale renewable energy production plants. Deep ocean mining to extract critical minerals for the construction of necessary equipment. Global reforestation projects so that mitigation can be materialised at speed. Carbon markets where harmful emissions are packaged into exchange and investment products. Technologies for geoengineering the climate that can alleviate the pressure to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Economic growth achieved through dematerialisation of production to address the increasing demand for ‘green products’. The technocapitalist imaginary aspires to harness the power of unregulated markets, making (a particular manifestation of) ecology attractive to venture capitalists, green philanthropists, and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs alike. Even if the future is not necessarily greener in strict terms, it is essential that the transition to it can be financially more profitable and less risky. Projected as a series of exciting investment opportunities that will ensure that capitalism is still materially and ethically legitimate and accepted, this is the dominant or hegemonic ecopolitical imaginary today. Simultaneously, the green transition is a technological challenge that can be addressed through financial products that will ensure that the dominant economic system continues to run – the only change being the fuel: renewables in the place of fossil fuels. This phasist understanding of the transition relies on a linear view of time, whereby human history can be narrated as a series of successive stages.

This is the imaginary, for example, portrayed and advanced in the EU green industrial policy (European Commission, 2023), which exemplifies the shift to viewing the green transition as a matter of profitable investment.Footnote 10 Carbon pricing has been an essential element of this imaginary: if carbon prices are correct, markets and rational behaviours will adjust towards a sustainable future. There is no need for explicitly normative or prescriptive measures; economic actors will work towards green and innovative solutions (Durand & Keucheyan, Reference Durand and Keucheyan2024). However, the gap in the level of investment required and the inadequacy of carbon pricing created the need for green industrial policies that diversify the policy mix and lower market barriers (Jakob & Overland, Reference Jakob and Overland2024). The EU green industrial plan introduces programmes such as InvestEU, which aims to derisk green investment, a strategy also favoured by the World Bank, G20, fiscal hawks, and mainstream economists (Skyrman, Reference Skyrman2024). Green derisking has the potential to accelerate decarbonisation by outsourcing it to private capital, while also derailing alternative pathways to decarbonisation (Gabor, Reference Gabor2023). The techno-capitalist transition is adaptationist, ‘a quest not to avoid the change, but rather to minimise its consequences’ (Felli, Reference Felli and Broder2021, p. 10). In the technocapitalist imaginary, the green transition is an opportunity for enhancing private profitability.

Confronting the green transition as a technological challenge that can be addressed through green investment is another aspect of this imaginary. The concept of ambient Prometheanism captures this, the preoccupation with humanity’s ability to confront the ecological crisis through optimistic but costly (and frequently unrealistic) technological interventions fuelled by intensified economisation while overlooking the social context within which these technologies and solutions emerge. The case of solar geoengineering is a point of relay: whereas in the past, such solutions were advanced mainly by conservative think tanks and politicians backed by the fossil fuel industry, today, they are promoted by coalitions of climate scientists, government agencies, environmental NGOs, and climate capital (Surprise & Sapinski, Reference Surprise and Sapinski2022). But behind the façade of grandiose innovative projects lies a deeply conservative spirit: its bearers see incremental, market-based decarbonisation as more palatable to technology capital (which now takes over the reins from the fossil capital). As Jesse Goldstein (Reference Goldstein2018) explains, clean technology entrepreneurship has fostered a vision of addressing climate change with new technologies that are hardly transformational. This new ‘green spirit of capitalism’ aims to ‘save the planet by looking for ‘non-disruptive disruptions’ through technologies that deliver ‘solutions’ without changing much of what causes the underlying problems in the first place.