Introduction

The political year 2019 was dominated by party politics and the issues of climate change, environmental protection and energy transition. While the Christian Democratic Union/Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU) and the Social Democratic Party/Sozialdemokratische Partei (SPD) scored poor election results in the European Parliament (EP) and (almost all) regional elections in Bremen, Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia, the Greens/Die Grünen (G) were the winners of the election year 2019. At the Land level, we witnessed a continued change from the traditional bipolar logic of party competition to the Greens becoming a pivotal player and indispensable coalition partner. Following the poor performance of her party in the elections to the EP, the SPD party leader Andrea Nahles resigned, and the party saw a long process of leadership selection involving its membership base.

Election report

European elections

In the ninth direct elections to the EP on 26 May 2019 (Table 1), 96 seats were up for election. Voter turnout rose significantly from 48.1 per cent in 2014 to 61.4 per cent. This is the highest voter turnout in all European elections in the Federal Republic of Germany since 1994 (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2019a: 12).

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament (Europäisches Parlament) in Germany in 2019

The CDU, the Christian Social Union/Christlich Soziale Union (CSU) and the SPD scored their worst results in the last 25 years (28.9 and 15.8 per cent, respectively). For the Greens in Germany, a 20.5 per cent share of the vote marked a historical success (+9.8 percentage points). They were returned as the second strongest party behind the CDU/CSU. The Alternative for Germany/Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) improved to 11.0 per cent (+3.9 percentage points). While The Left/Die Linke (L) incurred some losses (–1.9 percentage points), the Free Democratic Party/Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP) registered some gains (+2.1 percentage points). Both parties reached a good 5 per cent of the vote. Due to the lack of an electoral threshold in the European elections, a large number of other parties also managed to enter Parliament (in total, other parties accounted for 12.9 per cent of the vote).

Manfred Weber (CSU) was the Spitzenkandidat of the European People's Party (EPP)/Europäische Volkspartei (EVP) for the office of Commission President. Due to blocking in the European Council, in particular by French President Emmanuel Macron, and the EP's inability to unite behind a common Spitzenkandidat, German Federal Minister of Defence Ursula von der Leyen (CDU) finally became President of the European Commission.

Regional elections

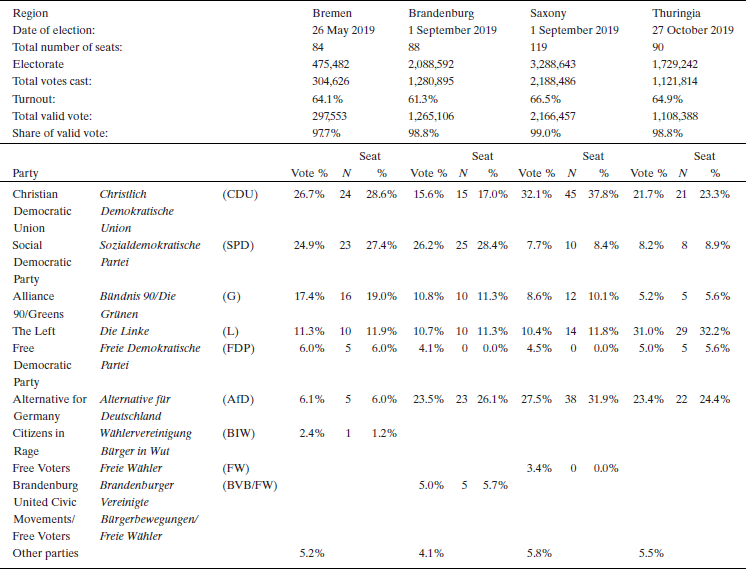

Four Land elections were held: in the city‐state of Bremen (26 May) and in the three Eastern German Länder of Brandenburg, Saxony (both 1 September) and Thuringia (27 October) (Table 2). Voter turnout rose significantly in all four regional elections, with the highest increase in Saxony (+17.4 percentage points compared with 2014).

Table 2. Results of regional (Bremen, Brandenburg, Sachsen, Thüringen) elections in Germany in 2019

Notes: In Bremen, there are 69 seats for Bremen and 15 seats for Bremerhaven. Because the 5 per cent threshold applies separately to Bremen and Bremerhaven, a party may win seats in Parliament by passing the threshold in one of the two electoral regions, even though it remains below 5 per cent in the state‐wide results. Every voter has five votes, which can be cast for parties/voter associations and/or individual candidates. Cumulative voting and panachage are possible.

For Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia, total valid vote and share of valid vote refer to the second vote.

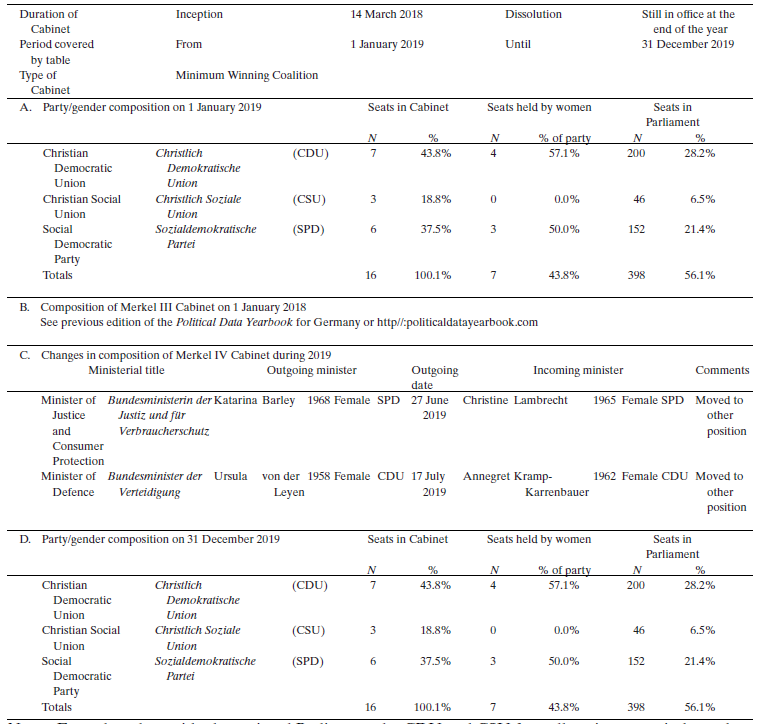

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Merkel IV in Germany in 2019

Notes: Even though outside the national Parliament the CDU and CSU formally exist as two independent party organizations, the sister parties traditionally form a common group in the Bundestag. Therefore, regarding the determination of the coalition type, both are considered as one ‘party’.

In Bremen, for the first time in the post‐war period, the CDU became the strongest party (26.7 per cent of the vote). The SPD lost 7.9 percentage points and scored its worst election result in the city‐state (24.9 per cent of the vote). This was the first time since 1947 the party was not returned as the strongest party to the Bremer Bürgerschaft (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2019b: 10, 42). With slight gains, The Left achieved its best ever result (11.3 per cent of the vote), and the Greens their second‐best result (17.4 per cent of the vote). The FDP narrowly made the 5 per cent threshold (6.0 per cent of the vote), while the AfD scored well below their results in the last federal and other recent regional elections (6.1 per cent of the vote). In Bremerhaven, the right‐wing voters’ association Citizens in Rage/Wählervereinigung Bürger in Wut (BIW) passed the 5 per cent threshold and gained one seat in the state legislature. In August 2019, the SPD, Greens and The Left agreed on a coalition government. This is the first coalition of the three parties in a Western German Land. After the resignation of former SPD mayor Carsten Sieling, Andreas Bovenschulte (SPD) became mayor and President of the Senate.

In Brandenburg, as for the past 29 years, the SPD was returned as the strongest party, yet it incurred losses (–5.7 percentage points) and slipped below 30 per cent for the first time since 1990 (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2019c). The Left and the CDU lost significantly (–7.9 and –7.4 percentage points, respectively) and fell to 10.7 and 15.6 per cent of the vote, respectively. This is the worst ever result for both in Brandenburg. The AfD gained significantly (+11.3 percentage points) and became the second strongest party in the state parliament (23.5 per cent of the vote). The Greens and FDP doubled their results, but while the former achieved their best result in a state election in an Eastern German Land (10.8 per cent of the vote), the latter failed to pass the 5 per cent threshold. The incumbent coalition of the SPD and The Left lost its majority. Prime Minister Dietmar Woidke (SPD) was re‐elected and now governs with the CDU and Greens.

In Saxony, the CDU suffered significant losses (–7.3 percentage points) in its ‘flagship stronghold’ (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2019d: 8; translated by the author). Mustering 32.1 per cent of the vote, it remained the strongest party ahead of the AfD, which, with an increase of 17.7 percentage points, was the second strongest party to enter the state legislature (27.5 per cent of the vote). The SPD fell to 7.7 per cent (–4.6 percentage points), its worst ever result in any state parliament election. The previous grand coalition was clearly voted out of office. While The Left achieved its worst election result in an Eastern German Land after 1990 (10.4 per cent of the vote), the Greens scored their best ever result in Saxony (8.6 per cent of the vote). The FDP once again missed the threshold to enter the Saxon state parliament. Three months after the state elections, a so‐called Kenya coalition of the CDU, Greens and SPD was formed led again by Prime Minister Michael Kretschmer (CDU).

In Thuringia, The Left achieved a record result with 31 per cent (+2.8 percentage points), becoming the strongest party ahead of the AfD, which mustered 23.4 per cent of the vote (+12.8 percentage points). In contrast, the CDU lost heavily (–11.8 percentage points) and fell to its worst ever result in Thuringia (21.7 per cent). The SPD also suffered losses (–4.2 percentage points) and achieved its second worst result (8.2 per cent) in any state election only topped by the result in Saxony (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2019e). The Greens and the FDP narrowly passed the 5 per cent threshold. Until the end of 2019, government formation proved difficult. The previous coalition of The Left, SPD and Greens no longer had a majority. There was no majority without The Left or the AfD in the Thuringian state legislature.

Cabinet report

There were two changes in Angela Merkel's fourth Cabinet in 2019. Katarina Barley (1968, female, SPD), Minister of Justice and Consumer Protection, was the lead candidate for her party in the elections to the EP. After her election, she was replaced by Christine Lambrecht (1965, female, SPD) in June. In July, then CDU party leader Annegret Kramp‐Karrenbauer (1962, female, CDU) succeeded Ursula von der Leyen (1958, female, CDU) as Minister of Defence.

Parliament report

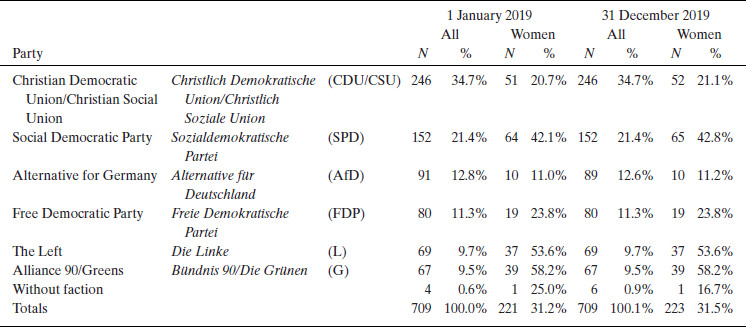

Table 4 depicts the composition of the Bundestag (lower house). In 2019, two members of the AfD left their parliamentary party group and are now independent MPs in the Bundestag. A total of 13 MPs left Parliament and were replaced by successors. This led to one more female MP in the SPD and CDU party groups, respectively. The share of female MPs increased slightly to 31.5 per cent.

Political party report

The year 2019 marked several far‐reaching changes in parties’ leadership (Table 5).

Table 5. Changes in political parties in Germany in 2019

Notes: From June to December, the SPD had a transitional party leadership. Originally by the Prime Ministers of Rhineland‐Palatinate and Mecklenburg‐Western Pomerania Malu Dreyer (1961, female, SPD) and Manuela Schwesig (1974, female, SPD), and the then leader of the SPD in Hesse Thorsten Schäfer‐Gümbel (1969, male, SPD).

Confirmed in office: AfD co‐chairperson Jörg Meuthen (1961, male, AfD), FDP chairperson Christian Lindner (1979, male, FDP), co‐chairperson of The Left parliamentary party group Dietmar Bartsch (1958, male, Left).

In January, Bavarian Prime Minister Markus Söder (1967, male, CSU) was elected party leader at a special party conference with 87.4 per cent of the vote. He replaced Horst Seehofer (1949, male, CSU) who remained Minister of the Interior. In April, the FDP party conference elected Nicola Beer (1970, female, FDP) deputy party chairperson with 59 per cent of the vote.

Following the poor performance of her party in the elections to the EP, the SPD party and parliamentary party group leader Andrea Nahles (1970, female, SPD) resigned from both offices in June. A transitional leadership was formed by three Land politicians, the Prime Ministers of Rhineland‐Palatinate and Mecklenburg‐Western Pomerania Malu Dreyer (1961, female, SPD) and Manuela Schwesig (1974, female, SPD), and the then leader of the SPD in Hesse Thorsten Schäfer‐Gümbel (1969, male, SPD). With 23 regional conferences and the selectorate consisting of all‐party members, the process of leadership selection was designed to maximize grassroots participation. Two‐person teams with at least one female candidate were explicitly encouraged. Eventually, six pairs of candidates took part and a run‐off vote became necessary. With 53 per cent, Saskia Esken (1961, female, SPD) and Norbert Walter‐Borjans (1952, male, SPD) emerged as winners from the members’ vote (voter turnout 54 per cent) in November. On 6 December, the federal party congress confirmed the results of the membership vote and elected Esken with 75.9 per cent of the vote and Walter‐Borjans with 89.2 per cent. In June, Rolf Mützenich (1959, male, SPD) provisionally took over the chairmanship of the SPD parliamentary group and was elected chairman on 24 September with 97.7 per cent of the vote.

On 12 November, Sahra Wagenknecht (1969, female, The Left), prominent co‐leader of The Left group in the German Bundestag since 2015, was replaced by Amira Mohamed Ali (1980, female, The Left), a lawyer who is part of the left wing of her party and has only been in Parliament for two years.

On 30 November, the AfD federal party conference elected Tino Chrupalla (1975, male, AfD), a member of the Bundestag for Saxony, as party chairman to replace former party leader Alexander Gauland (1941, male, AfD). Co‐chairman Jörg Meuthen (1961, male, AfD) was confirmed in office.

Issues in national politics

Political competition was dominated by party politics as well as the issues of climate change, environmental protection and energy transition. Alongside the climate strikes by the Fridays for Future youth movement, public debate also centred on measures to combat climate change. In March, the German government formed a cabinet committee on climate protection. In September, this ‘climate cabinet’ presented the so‐called climate package, which was passed by the Bundestag in November. Among other things, it contains regulations on CO2 price, taxes on flight tickets and an increase in tax breaks for commuters. The package is intended to achieve the targets for 2030; the Greens in particular found the measures to be insufficient.

The social policy issue in 2019 was basic pensions, an election campaign promise by the SPD. After a long dispute, the coalition parties agreed on a compromise in November, which provided for an income test, but not the means test that CDU/CSU had demanded.

The murder of Kassel's district president, Walter Lübcke, in June, numerous attacks on local politicians, and the attack on a synagogue in Halle in October sparked a debate on right‐wing extremist terrorism in Germany.

With the votes of all parliamentary party groups in the opposition, the Bundestag set up a committee of inquiry into a new German motorway toll and especially into the conduct of the Minister of Transportation Andreas Scheuer (CSU) in November. In June, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) had declared the German concept for tolls on motorways to be illegal because it breached anti‐discrimination laws.

Overall, developments in 2019 confirm ongoing, fundamental changes in the German party system, that is partisan dealignment with traditional parties (Poguntke Reference Poguntke2014). At the same time, the Greens were the winners of the election year 2019. At the Land level, we see a continuing shift from the traditional bipolar logic of party competition to the Greens becoming a pivotal party and indispensable coalition partner. Whether this translates to the federal level remains to be seen.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Anne Möcklinghoff for her support with data collection.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.