Bipolar disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are prevalent psychiatric conditions that frequently present with overlapping symptoms, complicating differential diagnosis and clinical management. Up to 20% of adults diagnosed with bipolar disorder also meet the criteria for comorbid ADHD, and 10–12% of youths with ADHD are later diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Reference Torres, Gómez, Colom, Jiménez, Bosch and Bonnín1,Reference Brancati, Perugi, Milone, Masi and Sesso2 Early-onset bipolar disorder symptoms may also be misdiagnosed as ADHD during adolescence, given the overlap in features such as restlessness, impulsivity and distractibility. In contrast to ADHD, bipolar disorder is characterised by intermittent episodes of (hypo)mania and depression, separated by periods of affective stability where excessive mood symptoms are mostly absent. Nonetheless, many individuals with bipolar disorder continue to experience residual symptoms during clinical remission, including persistent cognitive impairments. Reference Sparding, Silander, Pålsson, Östlind, Ekman and Sellgren3

Most studies indicate weaker overall executive functioning in individuals with bipolar disorder (with and without comorbid ADHD) as compared with adults with ADHD alone. Reference Jespersen, Obel, Lumbye, Kessing and Miskowiak4–Reference Udal, Øygarden, Egeland, Malt and Groholt7 Furthermore, we found that bipolar disorder patients with a history of childhood ADHD demonstrated poorer working memory compared with bipolar disorder patients without ADHD, although no differences were observed in other cognitive domains. Reference Salarvan, Sparding and Clements5 Other studies have similarly reported greater impairments in executive function, attention and working memory in bipolar disorder + ADHD patients relative to those with bipolar disorder alone. Reference Jespersen, Obel, Lumbye, Kessing and Miskowiak4,Reference Udal, Øygarden, Egeland, Malt and Groholt7–Reference Torres, Garriga, Sole, Bonnín, Corrales and Jiménez9 However, findings are not entirely consistent. A recent meta-analysis reported that cognitive performance did not differ significantly between bipolar disorder + ADHD and bipolar disorder groups, while bipolar disorder + ADHD patients had worse psychosocial functioning than those with either bipolar disorder or ADHD alone, and poorer visual memory than ADHD patients. Reference Amoretti, De Prisco, Clougher, Garriga, Corrales and Fadeuilhe10 To determine whether comorbidity has an additive effect on cognitive deficits, it is preferable to examine bipolar disorder, bipolar disorder + ADHD and ADHD within the same study design.

In ADHD, deficits in executive function – including cognitive flexibility, inhibition and working memory – have been shown to be associated with impaired occupational functioning. Reference Barkley and Murphy11,Reference Butzbach, Fuermaier, Aschenbrenner, Weisbrod, Tucha and Tucha12 In bipolar disorder, we previously reported that deficits in executive function, rather than illness severity, related to poor occupational function even during euthymia. Reference Drakopoulos, Sparding and Clements13 Furthermore, we previously found greater functional impairments in individuals with bipolar disorder + ADHD compared with those with bipolar disorder alone. Reference Rydén, Thase, Stråht, Åberg‐Wistedt, Bejerot and Landén14 However, most existing research is based on cross-sectional data, and it remains unclear whether cognitive performance can reliably predict long-term occupational outcomes. Moreover, we previously found that a higher polygenic risk for ADHD, but not for bipolar disorder, was associated with increased risk of long-term sick leave in individuals with bipolar disorder. Reference Jonsson, Hörbeck, Primerano, Song, Karlsson and Smedler15 Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the cognitive deficits observed in bipolar disorder and ADHD are driven by genetic liability for ADHD, bipolar disorder or both.

Aims of the study

The present study aimed to characterise neuropsychological performance and occupational functioning in individuals with bipolar disorder, ADHD and comorbid bipolar disorder + ADHD. First, we sought to delineate cognitive and occupational features distinguishing bipolar disorder with and without comorbid ADHD, relative to individuals with ADHD alone and healthy controls. Second, we aimed to replicate and extend previous findings by investigating whether neurocognitive functioning predicts long-term occupational outcomes. Third, we explored whether cognitive functioning is associated with polygenic scores (PGS) for bipolar disorder, ADHD and educational attainment.

Method

Sample

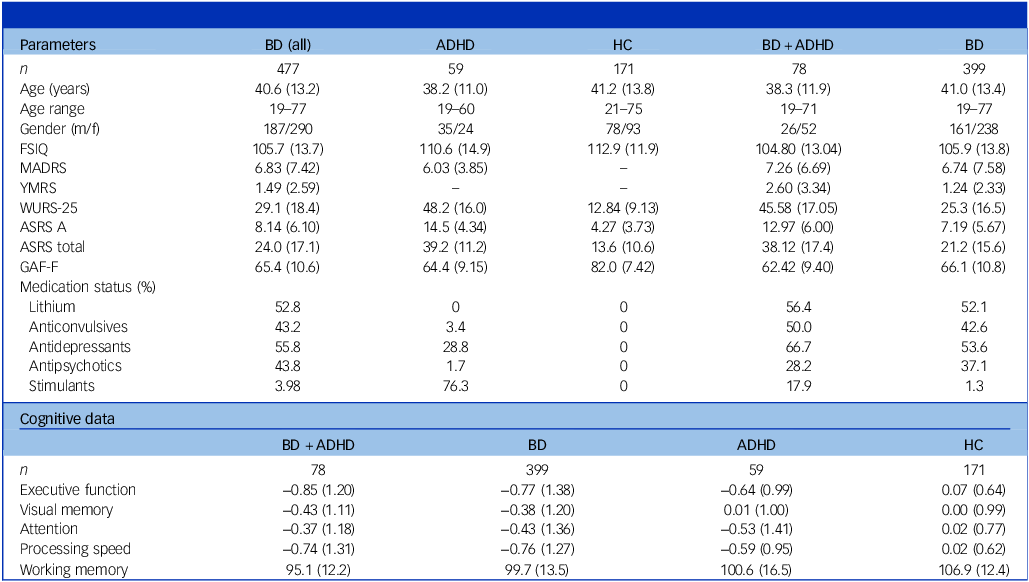

Study participants included (a) 477 individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder type 1 (bipolar disorder I) or type 2 (bipolar disorder II), (b) 59 individuals diagnosed with ADHD and (c) 171 healthy controls (see Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2026.10538) from the St. Göran project, a naturalistic, longitudinal study conducted at two study sites. Reference Landén, Jonsson, Klahn, Kardell, Göteson and Abé16 All participants underwent a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation performed by board-certified specialists in psychiatry or psychiatric residents. Diagnoses were made using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV TR) criteria and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) diagnostic interview, following a modified Swedish version of the Affective Disorder Evaluation. Reference Sachs, Thase, Otto, Bauer, Miklowitz and Wisniewski17 DSM-IV criteria have consistently been utilised since the study’s inception in 2005 to ensure reliable assessments and comparisons over time. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) was used for differential diagnostics, and to screen for comorbid psychiatric conditions. Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavas and Weiller18 Additional details are provided in ref. Reference Landén, Jonsson, Klahn, Kardell, Göteson and Abé16 . ADHD comorbidity in bipolar disorder was defined based on two criteria: (a) a life-time diagnosis of ADHD recorded in the National Patient Registry or established during the diagnostic study evaluation; and (b) fulfilment of symptom criteria for both childhood and adult ADHD, indicated by an Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) part A score >10, an ASRS total score >27 and a Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS)-25 score >46. Reference Ward, Wender and Reimherr19,Reference Kessler, Adler, Ames, Demler, Faraone and Hiripi20 Using this definition, 78 (16.4%) individuals with bipolar disorder were classified as having comorbid ADHD.

Table 1 Clinical, demographic and cognitive data

BD (all), all study participants with bipolar disorder; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; HC, healthy controls; BD + ADHD, bipolar disorder with comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; BD, bipolar disorder without comorbid ADHD; FSIQ, full-scale intelligence quotient from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale; MADRS, Montgomery−Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; WURS-25, Wender Utah Rating Scale; ASRS A, Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; GAF-F, Global Assessment of Functioning, functional dimension; WAIS-III, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third edition.

Data are presented as means, with standard deviation in parentheses. Working memory data were limited to individuals assessed with WAIS-III (238 bipolar disorder, 59 bipolar disorder + ADHD, 59 ADHD, 169 controls). All cognitive variables are z-scaled based on the mean and standard deviation of the healthy control group, except for the Working Memory Index, which is t-scaled to a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15.

Healthy controls were evaluated by a psychiatrist using MINI and parts of the Affective Disorder Evaluation. Exclusion criteria for controls included any previous or ongoing major psychiatric illness (defined as any psychiatric hospitalisation, current psychiatric morbidity or evidence of substance misuse); first-degree relatives with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; or neurological conditions (see ref. Reference Landén, Jonsson, Klahn, Kardell, Göteson and Abé16 for further details).

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the regional ethics committee in Stockholm, Sweden (no. dnr 2005/3:7). All study participants signed informed consent.

Clinical measures

Affective symptoms were assessed using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer21 and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). Reference Montgomery22 ADHD symptoms were assessed using both ASRS and WURS-25. Reference Ward, Wender and Reimherr19,Reference Kessler, Adler, Ames, Demler, Faraone and Hiripi20 Global functioning was evaluated using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale, which provides separate ratings for symptoms (GAF-S) and functional level (GAF-F). Reference Aas23 Participants were assessed during a clinically stable mood state as established by a YMRS score <6 and a MADRS score <14, and having maintained remission for at least 8 weeks.

Cognitive measures

All study participants underwent comprehensive neuropsychological testing, administered by a trained psychologist at specialised out-patient clinics in Stockholm and Gothenburg. The assessment included the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), four tests from the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System and the Rey Complex Figure Test. Reference Delis, Kaplan and Kramer24 The test battery was designed to capture five cognitive domains: executive function (switching, inhibition, strategic fluency), visual memory (visuospatial encoding and retrieval), working memory (active maintenance and manipulation of information), attention (sustained attention and response control) and processing speed (efficiency of basic cognitive operations). Composite scores for each domain were computed by standardising and averaging the relevant subtests (requiring two or more valid subtests per domain), with full details provided in the Supplementary Material. IQ was represented by the WAIS Full-Scale (FSIQ) score. While most of the study participants were tested using WAIS-III, 164 individuals from the Gothenburg site were tested using WAIS-IV (see Supplementary Material 2.2.1 and Supplementary Fig. 2 for details and sensitivity analyses). As an estimate of premorbid cognitive abilities, we extracted information on school grades from class 9 (age 15–16 years) and final school grades (age 18–19 years) from the Swedish National Agency for Education (Skolverket), which maintains national educational records in Sweden. Because grading systems had changed over the study period, the secondary school grades were nationally standardised and recoded into deciles to improve comparability. For final school grades, however, there is no standardised system (see Supplementary Material for further details).

Occupational function

The study interview included detailed information on occupational status. Participants reported whether, during the past 12 months, they had (a) worked at 50% or more of a full-time position, (b) worked at less than 50% of a full-time position, (c) engaged in supported employment or (d) had not worked. Individuals who were full-time students, engaged in full-time caregiving or on parental leave were considered active, because these roles reflect normative life circumstances rather than occupational impairment. Individuals older than 64 years were excluded, to account for regular retirement. Cross-sectional occupational status was categorised into two groups: active (working ≥50% of a full-time position) and inactive (working <50%, supported employment or not working).

Because the aim of this study was to predict occupational function using cognitive data, we extracted register data from the Swedish longitudinal integrated database for health insurance, and from labour market studies for the year of neurocognitive testing and the following 4 years. Two outcome variables were calculated as proportions across this 5-year period: (a) time in the workforce, defined as the proportion of years in which an individual’s main source of income derived from labour market activity, study funds or caregiving/parental leave; and (b) long-term sick leave, defined as the proportion of years in which an individual had received more than 60 days of sick-leave compensation (see Supplementary Material for details).

Genotyping and polygenic scoring

Participants in the present study (St. Göran project) were also included in the larger Swedish Bipolar Collection, Reference Landén, Joas, Karanti, Melchior, Zachrisson and Sigström25 in which genotyping was performed. Genotyping was conducted in four batches using Affymetrix 6.0 and Illumina platforms (PsychChip, OmniExpress and GSA). Quality control and imputation to the HRC 1.1 reference panel were performed separately for each batch using the RICOPILI pipeline. Reference Lam, Awasthi, Watson, Goldstein, Panagiotaropoulou and Trubetskoy26 Polygenic scores were computed using PRS-CS based on publicly available summary statistics from genome-wide association studies for bipolar disorder, Reference Koromina, van der Veen, Boltz, David and Yang27 ADHD Reference Demontis, Walters, Athanasiadis, Walters, Therrien and Nielsen28 and educational attainment. Reference Lee, Wedow, Okbay, Kong, Maghzian and Zacher29 In PRS-CS, we applied the global shrinkage parameter (phi) set to 1 × 10−5 to generate PGS within each genotyping batch. Detailed descriptions of the genotyping, imputation and polygenic scoring procedures are provided in Supplementary Methods and in refs Reference Jonsson, Hörbeck, Primerano, Song, Karlsson and Smedler15,Reference Jonsson, Song and Joas30 . PGS data were available for 219 bipolar disorder participants and 126 controls with corresponding cognitive data.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical data were analysed using t-tests and χ 2-tests for group comparisons. Raw scores from cognitive testing were standardised into z-scores based on the mean and standard deviation of the control group at each study site. The cognitive variables were transformed such that higher z-values indicate better performance. Outliers exceeding ±3 s.d. were winsorised by replacing them with the nearest value within the ±3 s.d. threshold. Binary logistic regression and ordinary least-squares regressions were used to analyse the cognitive and occupational data. All models were adjusted for age and gender. For significant models, pairwise group comparisons were performed using model-derived contrasts to examine differences between specific groups, adjusted for age and gender. For the association of PGS with cognitive data, we applied multiple linear regression to model each cognitive outcome as a function of the three PGS variables while adjusting for gender, age at sampling, population stratification (the first five ancestry principal components) and genotyping platform.

For the investigation of whether executive functioning predicts occupational functioning (time in the workforce), multiple linear regression models were fitted separately for each diagnostic group to examine the relationship between executive functioning and occupational functioning, adjusting for age, gender and IQ.

To correct for multiple comparisons, false discovery rate (FDR) correction (Benjamini–Hochberg procedure) was applied. Statistical analyses were conducted using the statsmodels Python package (version 0.14.6 in Python version 3.11 on a Windows platform; Skipper Seabold & Josef Perkthold; https://github.com/statsmodels/statsmodels).

Results

Demographic and clinical data

The study groups did not differ in regard to age (see Table 1). Gender distribution was similar across groups, except for a significantly higher proportion of females in the ADHD group compared with the bipolar disorder group (χ 2 (1,1) = 7.94, P FDR = 0.014). Regarding ADHD comorbidity, individuals with bipolar disorder + ADHD had higher YMRS scores than those with bipolar disorder alone (t (263) = 2.68, P FDR = 0.028). Both the bipolar disorder + ADHD and ADHD groups scored higher on WURS and ASRS compared with the bipolar disorder group (see Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2).

Bipolar subtype distributions did not differ between bipolar disorder with and without ADHD. Among individuals with bipolar disorder + ADHD, 38.5% were classified as bipolar disorder I and 50.0% as bipolar disorder II. In the bipolar disorder-only group, 41.5% were bipolar disorder I and 43% were bipolar disorder II. The remaining individuals in both groups were categorised as bipolar disorder not otherwise specified.

At age 15–16 years, individuals with ADHD had significantly lower school grades compared with those with bipolar disorder (Kruskal–Wallis (H)(1) = −8.46, P FDR = 0.01) and healthy controls (H (1) = −8.99, P FDR = 0.01), while no significant differences were observed between individuals with bipolar disorder and healthy controls, or between the ADHD and bipolar disorder + ADHD groups. In regard to final school grades (age 18–19 years), individuals with bipolar disorder + ADHD had significantly lower school grades than both the bipolar disorder group (t (297) = −3.84, P FDR = 0.001) and controls (t (172) = −2.65, P FDR = 0.001). Similarly, individuals with ADHD had lower final school grades than those with bipolar disorder (t (171) = −3.90, P FDR = 0.001) and controls (t (171) = −2.94, P FDR = 0.011). No significant differences were found between bipolar disorder and controls, nor between bipolar disorder + ADHD and ADHD (see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3).

Cognitive data

All patient groups preformed significantly worse than healthy controls (s.d. = 0.64–0.85 for executive function) across all cognitive domains (all P FDR < 0.01), with the exception of visual memory, where no significant difference was observed between the ADHD group and controls (see Fig. 1, Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Among the clinical groups, individuals with bipolar disorder + ADHD showed significantly poorer working memory compared with those with bipolar disorder alone (t (426) = −2.21, P FDR = 0.048).

Fig. 1 Cognitive performance across four domains by diagnostic group. Executive function, attention and processing speed are z-scaled based on healthy controls. Working memory is represented by the Working Memory Index (WMI) from Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, scaled to a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Boxplot whiskers represent 1.5 × interquartile range. BD + ADHD, bipolar disorder with comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; BD, bipolar disorder without comorbid ADHD; HC, healthy controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Occupational function

Among participants younger than 65 years, cross-sectional interview data showed that both the bipolar disorder and ADHD groups had markedly lower odds of being occupationally active compared with healthy controls: 88% lower in bipolar disorder (odds ratio 0.12, 95% CI [0.06, 0.27], P FDR < 0.001) and 86% lower in ADHD (odds ratio 0.14, 95% CI [0.05, 0.37], P FDR < 0.001). Higher age was associated with reduced odds of being active (odds ratio 0.97, 95% CI [0.96, 0.99], P FDR = 0.001), indicating that each additional year of age decreased the odds of being active by approximately 2.7%. Gender was not a significant predictor, and no differences were observed between the patient groups.

In longitudinal analyses of occupational functioning over the 5 years following cognitive testing, all patient groups spent significantly less time in the workforce compared with healthy controls (P FDR < 0.001; see Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 6). Individuals with bipolar disorder + ADHD spent less time in the workforce than both those with bipolar disorder alone (t (575) = 4.24, P FDR < 0.001) and those with ADHD (t (575) = 4.96, P FDR < 0.001). The bipolar disorder group in turn spent less time in the workforce than the ADHD group (t (575) = 2.26, P FDR = 0.024). Increasing age was again negatively associated with occupational functioning (P < 0.001; see Supplementary Table 6). In regard to long-term sick leave, we found similar results (see Supplementary Table 6).

Fig. 2 Occupational function across diagnostic groups. Time in the workforce is defined as having received one’s main yearly income from active work or caretaking. Each group is represented by a grey violin plot showing the kernel density estimate (KDE) of the distribution; individual data points are plotted within the KDE contour. Coloured boxplots indicate the median, and whiskers extend to 1.5 × interquartile range. Outliers are indicated by coloured outlined circles. BD + ADHD, bipolar disorder with comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; BD, bipolar disorder without comorbid ADHD; HC, healthy controls. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Prediction of occupational function

In the full sample, a regression model including executive function and FSIQ as predictors, with age and gender as covariates, explained 14.5% of the variance in time in the workforce representing occupational function. Executive function emerged as the strongest predictor (standardised regression coefficient (stand β) = 0.26, P FDR < 0.001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.35]), followed by FSIQ (stand β = 0.09, P FDR = 0.044, 95% CI [0.00, 0.18]), age and gender.

When diagnostic group (ADHD, bipolar disorder, bipolar disorder + ADHD and controls) was added to the model, the explained variance increased to 23.8%, but only group and age remained significant predictors while executive function and FSIQ no longer contributed significantly (see Supplementary Material for details). We therefore conducted separate regression analyses within each diagnostic group. In the bipolar disorder group, occupational function was significantly predicted by executive function (stand β = 0.20, 95% CI [0.09, 0.31], P FDR = 0.006) and age (stand β = −0.17, 95% CI [−0.28, −0.06], P FDR = 0.023). In the bipolar disorder + ADHD group, age was negatively associated with occupational function but this did not remain significant following FDR correction (stand β = −0.32, 95% CI [−0.58, −0.06], P = 0.016, P FDR = 0.083). No significant predictors were identified in the ADHD or control groups (see Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 7).

Fig. 3 Relation between executive function and occupational function. Executive function is represented by z-scores based on the mean and standard deviation of healthy controls. Occupational function is represented by the variable time in the workforce, defined as having received one’s main yearly income from active work or caregiving. Higher values indicate better occupational function. BD + ADHD, bipolar disorder with comorbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; BD, bipolar disorder without comorbid ADHD; HC, healthy controls.

We also compared the predictive value of current cognitive capacity (FSIQ at the time of testing) with premorbid cognitive abilities, estimated using final school grades at age 18–19 years and school grades at age 15–16 years, within the bipolar disorder group. While higher FSIQ explained a modest proportion of variance in occupational function over the following 5 years (up to 8.5%), premorbid cognitive abilities did not predict occupational outcomes (see Supplementary Material 5.3 for details).

Secondary analysis: subgroup with cognitive and occupational impairments

We identified a subgroup of 25 individuals with marked cognitive (executive function below −2 s.d.) and occupational impairments (≤20% time in the workforce): 18 with bipolar disorder, 5 with bipolar disorder + ADHD and 2 with ADHD. This subgroup was significantly older, had lower GAF scores, lower FSIQ and a higher rate of antipsychotic medication use. No significant differences were observed for depressive symptoms (MADRS), manic symptoms (YMRS), gender or the use of lithium, anti-epileptic, antidepressant or central stimulants (see Supplementary Table 8 for details).

PGS

We examined associations between PGS and cognitive performance. In healthy controls, the educational attainment PGS was positively associated with executive function (stand β = 0.21, 95% CI [0.09, 0.32], P FDR = 0.003), attention (stand β = 0.32, 95% CI [0.18, 0.46], P FDR < 0.001) and processing speed (stand β = 0.20, 95% CI [0.08, 0.33], P FDR = 0.023). In the bipolar disorder group, educational attainment PGS was positively associated with working memory (stand β = 0.19, 95% CI [0.08, 0.30], P FDR = 0.007). No significant associations were observed between PGS for bipolar disorder or ADHD and cognitive performance in any group (see Supplementary Tables 9.1 and 9.2). The bipolar disorder + ADHD group showed a non-significant trend towards higher ADHD PGS compared with the bipolar disorder group without comorbid ADHD (P = 0.10).

Discussion

This study aimed to characterise cognitive and occupational function in individuals with bipolar disorder, ADHD and bipolar disorder + ADHD. The main findings were as follows: (a) all patient groups – bipolar disorder, bipolar disorder + ADHD and ADHD – displayed lower performance across all cognitive domains compared with healthy controls, with the bipolar disorder + ADHD group exhibiting significantly poorer working memory than the bipolar disorder-only group. (b) Occupational functioning was impaired across all patient groups, both cross-sectionally and prospectively, over the 5 years following cognitive testing. Individuals with bipolar disorder + ADHD had the most pronounced occupational impairments, followed by bipolar disorder and then ADHD. (c) In the bipolar disorder group, lower executive function and higher age significantly predicted poorer occupational functioning over time. This association was observed neither in the ADHD group nor in controls. (d) PGS for educational attainment were positively associated with cognitive performance, with a stronger effect observed in the bipolar disorder group as compared with healthy controls. No significant associations were found between PGS for bipolar disorder and ADHD, respectively, and cognitive performance.

Cognition in bipolar disorder and ADHD

Individuals with bipolar disorder, ADHD and bipolar disorder + ADHD exhibited broad cognitive impairments relative to controls, except for visual memory in the ADHD group. This relative preservation is consistent with previous findings suggesting that visuospatial abilities may remain intact in ADHD despite widespread executive and attentional deficits. Reference Torres, Garriga, Sole, Bonnín, Corrales and Jiménez9 Notably, the bipolar disorder + ADHD group exhibited significantly poorer working memory than the bipolar disorder group without comorbid ADHD, while cognitive performance between bipolar disorder + ADHD and ADHD alone was largely similar. Thus, our results suggest that working memory may be particularly sensitive to combined neurodevelopmental and mood-related disruptions in the bipolar disorder + ADHD group; this is supported by some, Reference Jespersen, Obel, Lumbye, Kessing and Miskowiak4,Reference Salarvan, Sparding and Clements5,Reference Udal, Øygarden, Egeland, Malt and Groholt7 but not all, previous studies. Reference Torres, Sole, Corrales, Jiménez, Rotger and Serra‐Pla6,Reference Çelik, Ceylan, Ongun, Erdoğan, Tan and Gümüşkesen31 Given the central role of working memory in planning, self-regulation and goal-directed behaviour, deficits in this domain may contribute to the occupational and psychosocial impairments observed in bipolar disorder + ADHD. These findings underscore the importance of screening for comorbid ADHD in bipolar disorder, and of considering working memory as a target for cognitive interventions.

The presence of cross-diagnostic cognitive impairments highlights a shared neurocognitive burden. Executive dysfunction, attentional deficits and slowed processing speed were observed across all clinical groups, suggesting disruption of core cognitive domains regardless of diagnosis. These findings support the value of transdiagnostic approaches to cognitive assessment and intervention.

The wide confidence intervals in our cognitive data (see Fig. 1) reflect the well-documented cognitive heterogeneity in bipolar disorder, supporting the existence of cognitive subgroups ranging from preserved to markedly impaired cognition. Reference Sparding, Silander, Pålsson, Östlind, Ekman and Sellgren3 This variability underscores the importance of personalised treatment strategies that account for individual cognitive profiles, including targeted interventions such as working memory training for those with bipolar disorder + ADHD. Clinically, these findings underscore the need to incorporate targeted cognitive remediation, cognition-focused psychoeducation and supported employment interventions into treatment planning for patients with pronounced executive deficits.

Cognitive and occupational function

All clinical groups demonstrated significantly reduced occupational functioning, both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, with the bipolar disorder + ADHD group displaying the most pronounced impairments. These findings align with previous research indicating that individuals with bipolar disorder + ADHD often display earlier illness onset, more frequent mood episodes, greater substance use and poorer treatment response – factors probably contributing to greater functional disruptions. Reference Torres, Gómez, Colom, Jiménez, Bosch and Bonnín1,Reference Amoretti, De Prisco, Clougher, Garriga, Corrales and Fadeuilhe10,Reference Schiweck, Arteaga-Henriquez, Aichholzer, Edwin Thanarajah, Vargas-Cáceres and Matura32

In the bipolar disorder group, executive function was a key predictor of occupational functioning, highlighting the importance of cognitive capacity in shaping functional outcomes. In contrast, school grades – used as a proxy for premorbid cognitive abilities – did not predict occupational function, suggesting that early cognitive potential may have limited relevance once the illness has developed. This supports previous evidence that cognitive decline in bipolar disorder is pronounced around illness onset, with adult functional outcomes more strongly influenced by illness-related changes than by genetic predisposition or baseline ability. Reference Miskowiak and Lewandowski33

However, it remains unclear whether severe cognitive impairments in bipolar disorder are present from the early stages or develop progressively over the course of the disorder. Reference Sparding, Joas, Clements and Sellgren34 This distinction is central to the debate on neuroprogression in bipolar disorder, which posits that repeated mood episodes, psychosocial stressors and related neurobiological changes may cumulatively contribute to cognitive decline over time (for a discussion, see ref. Reference Yatham, Schaffer, Kessing, Miskowiak, Kapczinski and Vieta35 ). Although our registry-based outcome variables provide longitudinal data across 5 years, this time frame does not capture the longer-term, lifespan trajectories required to determine whether occupational functioning declines as a consequence of illness progression.

By contrast, within the bipolar disorder + ADHD group, age but not cognitive performance was related to lower occupational functioning. More broadly, older age was linked to lower occupational function across all patient groups. This may reflect age-related decline in executive and occupational function, as previously reported in ADHD. Reference Helgesson, Björkenstam, Rahman, Gustafsson, Taipale and Tanskanen36–Reference Biederman, Petty, Fried, Fontanella, Doyle and Seidman38

From a phenomenological perspective, the more pronounced impairments in the bipolar disorder + ADHD group probably reflect the cumulative burden of overlapping symptom dimensions. ADHD involves persistent inattention, impulsivity and executive dysfunction, while bipolar disorder introduces episodic shifts in affect, motivation and cognitive control. When combined, these processes may exceed compensatory capacities, leading to more pervasive cognitive and occupational difficulties. Importantly, this study included only individuals with well-established childhood-onset ADHD, and the sample’s mean age (∼40 years) reduces the likelihood that our findings reflect recent increases in adult ADHD diagnoses.

PGS and cognition

We examined genetic contributions to cognitive performance using PGS for bipolar disorder, ADHD and educational attainment. While no significant associations were observed between cognitive performance and PGS for bipolar disorder or ADHD, the educational attainment PGS was positively associated with several cognitive domains in both bipolar disorder and controls. These findings echo previous research suggesting that the PGS for educational attainment captures genetic variance related to cognitive capacity. Reference Lee, Wedow, Okbay, Kong, Maghzian and Zacher29 One consideration is that a higher educational attainment PGS may serve as a protective factor against cognitive decline in bipolar disorder, potentially serving as a biomarker for cognitive resilience. Future studies should use longitudinal design and account for environmental moderators, such as treatment history and socioeconomic factors, to better understand how genetic predispositions interact with real-world outcomes.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, although we employed a well-established battery of neurocognitive tests, it may have lacked sensitivity to detect certain cognitive impairments in ADHD. This reflects broader concerns about the limited ecological validity of traditional neuropsychological testing, which may not capture context-dependent symptoms such as distractibility and impulsivity. Emerging tools such as virtual reality-based assessments may offer more ecologically valid measures by better approximating real-life cognitive demands. Reference Miskowiak, Jespersen, Kessing, Aggestrup, Glenthøj and Nordentoft39 Second, while the overall sample was large and clinically well characterised, the bipolar disorder + ADHD and ADHD subgroups were smaller than the bipolar disorder group, which may have limited the statistical power to detect more nuanced differences in cognitive performance across diagnostic groups. Third, pharmacological treatments may affect cognitive performance. In our sample, individuals with both severe occupational impairments and executive dysfunction were more likely to have been prescribed antipsychotic medication. While antipsychotics are essential for managing acute symptoms and preventing relapses, their potential long-term cognitive side-effects may hinder functional recovery. Although causality has not been established, existing evidence suggests that cognitive performance in medicated populations may underestimate true capacity. Clinicians should therefore carefully evaluate the necessity and dosage of antipsychotic medication in supporting cognitive and occupational recovery. Although stimulant medication may theoretically mitigate cognitive deficits in ADHD, our sensitivity analyses comparing stimulant-treated and non-treated individuals did not reveal clear differences in cognitive performance. Furthermore, we cannot account for the potential influence of sleep-related factors on cognitive performance, because detailed sleep measures were not systematically collected.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2026.10538

Data availability

Custom-written code will be shared following reasonable request from a qualified academic investigator for the sole purpose of replicating procedures and results presented in the article. Data are available following formal request, and access is regulated by the EU General Data Protection Regulation, the Swedish Public Access and Confidentiality Act and the Swedish Ethical Review Act.

Acknowledgements

We thank all our study participants and the staff at St. Göran bipolar affective disorder units in Stockholm and Gothenburg. We especially acknowledge our research nurses Annika Blom, Agneta Carlswärd-Kjellin, Benita Gezelius, Lena Lundberg, Stina Stadler, Therese Tureson and Martina Wennberg, psychologists Timea Sparding and Andreas Aspholmer and data manager Mathias Kardell. Eleonore Rydén is gratefully acknowledged for recruiting the attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder group.

Author contributions

A.L.K. and M.L. designed the study. M.L. collected the data. A.L.K., E.H., A.G. and L.J. analysed the data, which were interpreted by A.L.K., A.G., E.H., L.J., E.P. and M.L. A.L.K. drafted the manuscript, which all other authors revised. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, no. 2022-01643), the Swedish Brain Foundation (Hjärnfonden, no. FO2025-0004-HK-212), the Swedish Federal Government under the LUA/ALF agreement (no. ALFGBG-965444) and the Märta-Lundqvist Foundation. The funders had no role in the design, data collection, data analysis and reporting of this study.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.