Introduction

In the European Union (EU), ‘crisis’ has become normality. Perceived unfair and opaque EU austerity policies, high unemployment rates, bailout packages and an uncoordinated response to an unprecedented number of refugees, have made people aware of the negative consequences of supranational integration. This frustration has driven the success of anti‐EU parties, thereby nurturing polarisation in societies across European member states (e.g., Börzel, Reference Börzel2016; Hobolt & De Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2016; Lahusen & Grasso, Reference Lahusen and Grasso2018). Also, most recently with the COVID‐19 pandemic, crisis tackling has seemed to overwhelmingly remain a national issue, with citizens rallying around the (national) flag (Bol et al., Reference Bol, Giani, Blais and Loewen2020). While affecting different policy areas, EU crises represent an ongoing fundamental challenge to the legitimacy of the multilevel polity: how crises are managed and evaluated may well decide the future of the EU, as they directly affect the lives of millions of EU citizens. ‘[I]ntegrity and legitimacy … is central to the theme of crisis’ (Heath, Reference Heath, Cook and Holladay2010, p. 2) and the EU's legitimacy has long been a contested issue (Follesdal & Hix, Reference Follesdal and Hix2006). The political task of legitimation, that is, the public communication and justification of EU (crisis) politics for fostering legitimacy and public acceptance, remains a crucial challenge on the agenda of responsible decisionmakers (e.g., Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Nord and Falkheimer2015).

Given the societal importance, much research has analysed public political communication about the EU and its crises. However, the academic debate needs to be developed analytically: First, extant literature analysing EU crises typically does not focus on crisis managers’ legitimation efforts, that is, politicians’ direct communications (e.g., Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009; Börzel, Reference Börzel2016; Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Nord and Falkheimer2015; Zeitlin et al., Reference Zeitlin, Nicoli and Laffan2019). Second, they often analyse single crisis cases and/or do not assess public crisis communication across countries, over time or across different crises (Angouri & Wodak, Reference Angouri and Wodak2014; t'Hart & Tindall, Reference ’t Hart, Tindall, ’t Hart and Tindall2009). Third, while crises are the major confounding factors regarding contemporary EU politics, they are often incorporated into research focusing on communication only as a contextual issue; that is, studies look into communication ‘in times of crisis’ rather than confronting crises directly (e.g., Auel et al., Reference Auel, Eisele and Kinski2016; Rauh et al., Reference Rauh, Bes and Schoonvelde2020). Thus, we lack an adequate analytical framework to address the crisis aspect of political communication explicitly. Research has not yet developed a generalised perspective on political crisis legitimation processes to evaluate broader trends and patterns which are, however, likely to have influenced the political developments described above.

We aim to advance the discussion by constructing a conceptual and analytical framework to map and evaluate public political crisis communication, understood as the public legitimation of crisis politics by political decisionmakers. We develop a generic perspective that can transcend individual crises and also be applied beyond the EU context. We draw on crisis management research as an applied science that has evaluated different instances of crisis management and given prescriptions of what constitutes ‘good’ crisis communication (e.g., Coombs, Reference Coombs2007, Reference Coombs, Heath and O'Hair2010). Based on these recommendations, we define four dimensions along which public political crisis communication can be evaluated: (1) its accessibility, (2) its potential to allay fears, (3) its accommodation of public concerns, and (4) the political alignment conveyed in it. Providing a framework for identifying general patterns in the legitimation processes of crisis politics, we go beyond the contingencies of individual crises, allowing a long‐term comparison of the communicative performance of executives as crisis managers.

We demonstrate the viability of our approach by conducting a long‐term analysis of public crisis communication. Specifically, we analyse press releases of four national governments (Austria, Germany, Ireland, United Kingdom) and the European Commission and Councils, as well as speeches of leaders (chancellors/prime ministers, presidents of the European Commission/Council), over a period of 10 years (2009−2018). We use different methods of automated content analysis (e.g., Boumans & Trilling, Reference Boumans and Trilling2016) to assess how communication efforts score on the four defined dimensions. We demonstrate the cohesion of crisis‐relevant communication in contrast to non‐relevant communication based on a holistic similarity index, computed as the average cosine similarity of public political crisis communication across the four dimensions. Importantly, the similarity index is a structural measure that, detached from the actual contents of crisis communication, allows comparing crisis managers’ performances directly across different cultural and linguistic contexts. Overall, our study contributes to the debate on the crises of (European) democracies, providing a generic framework for evaluating political crisis legitimation.

Political legitimation in times of crisis

The challenge of crisis legitimation

The use of political power in democratic societies needs to be publicly justified to citizens in order to maintain political legitimacy (Beetham, Reference Beetham1991). This process of legitimation includes the making transparent of political processes and decisions by responsible decisionmakers. It should ideally result in the public acceptance of political output and the way power is used. Therefore, both the use of power and its legitimation need to build on and appeal to common normative standards and shared beliefs (e.g., Beetham, Reference Beetham1991; Habermas, Reference Habermas1962). The occurrence of a crisis may induce fundamental changes in how a political community is organised. Crises may question the shared beliefs and norms on which this community is built. Dominant agreements about the polity's legitimacy may have to be re‐assessed and shared normative standards re‐negotiated (’t Hart & Tindall, Reference ’t Hart, Tindall, ’t Hart and Tindall2009, p. 21). Executives may have to be exchanged if they, as responsible decisionmakers entrusted with the conduct of government, fail to tackle crises and lose control of the situation (Boin et al., Reference Boin, Kuipers and Overdijk2013; Heath, Reference Heath, Cook and Holladay2010).

‘Crisis’ is defined as a situation when ‘political‐administrative elites perceive a threat to the core values of a society and/or life‐sustaining systems in that society that must be addressed urgently under conditions of deep uncertainty’ (Boin et al., Reference Boin, Ekengren and Rhinard2020, p. 6 conferring Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Boin and Comfort2001). Crises, thus, pose severe challenges to political leaders: They are expected to act fast, responsibly and in the best interest of their citizens, yet in fast changing situations where the consequences of decisions are most difficult to anticipate (Heath, Reference Heath, Cook and Holladay2010). At the same time, the public demand for justification of such decisions is heightened exactly due to this increased uncertainty and the fact that political leaders’ decisions most directly define the conditions under which citizens live through a crisis and how they come out of it (Falkheimer & Heide, Reference Falkheimer, Heide, Coombs and Holladay2010). In democracies, where public support is the currency in which political success is traded, crises have made or broken many political careers (Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Nord and Falkheimer2015).

Crisis scholars stress the objectivity and subjectivity of crises. Crises are empirical phenomena with objectively measurable consequences, for example, natural disasters. More importantly, crises are social processes: ‘… perhaps most threat situations are not self‐evident. People must grow convinced that a certain development or condition threatens core values, public institutions, critical infrastructures, or the direct well‐being of people’ (Boin et al., Reference Boin, Ekengren and Rhinard2020, p. 6). In this subjective sense, crises are perceptual, and political crisis managers need to deal with these subjectivities to restore normality (Coombs, Reference Coombs, Heath and O'Hair2009, p. 100).

The legitimation of crisis politics – or crisis communication, defined as ‘the collection, processing, and dissemination of information required to address a crisis situation’ (Coombs, Reference Coombs, Heath and O'Hair2010, p. 20), therefore, is a crucial part of political crisis management as the ‘sum of activities aimed at minimizing the impact of a crisis’ (Boin et al., Reference Boin, Kuipers and Overdijk2013, p. 81). While the term may also include behind‐the‐scenes coordinative communication amongst crisis managers, public crisis communication is a symbolic resource or tool to manage the public's reactions to crises and their management (Benoit, Reference Benoit1995; Coombs, Reference Coombs, Heath and O'Hair2009). Via public communication, political leaders should manage both information and meaning. The management of information is thus instructive about the dissemination of factual information. It is important for the public to understand crises to know how to protect themselves and how crisis managers support them. Managing meaning concerns two levels: meaning as the perception of the crisis as such and meaning as the perception of the crisis manager (Coombs, Reference Coombs, Heath and O'Hair2010).

‘[C]risis communication is normative, as is its management. The goal of crisis management and communication is to prevent harm to others and to be accountable’ (Heath, Reference Heath, Cook and Holladay2010, p. 6). Beyond these normative considerations, it is, however, crucial to keep in mind that political decisionmakers have a strategic interest in being perceived as ‘good’, successful crisis managers since their political career may depend on it. Accordingly, political decisionmakers tailor their public crisis communication to the anticipated reactions of the general public to earn acceptance and to foster their own position (Coombs, Reference Coombs2015; Kreuder‐Sonnen, Reference Kreuder‐Sonnen2019; White, Reference White2019).

Four dimensions of public political crisis communication

Our goal is to transfer the main insights from crisis management research to the field of political communication, abstracted from individual crises and their topics; to develop a framework that can be applied to public political crisis communication, notwithstanding the exact time point or context in which communication is analysed. Focusing on democratic legitimation processes, the central goal is the acceptance of crisis politics by the people. The four aspects identified in the following, therefore, focus on the relationship between executives as senders and the public as receivers of crisis communication in terms of managing information and meaning.

(1) An increased accessibility of information is crucial to empower people, regardless of their cognitive or intellectual capacities, to understand and prepare, especially in a situation of increased stress and anxiety. The literature emphasises the process of explaining what is happening and making people understand how they can help themselves (Falkheimer & Heide, Reference Falkheimer, Heide, Coombs and Holladay2010, p. 515). Thus, executives should communicate in a way that contributes to citizens’ understanding (Temnikova, Reference Temnikova2012). Language complexity negatively affects political knowledge acquisition more generally (Tolochko et al., Reference Tolochko, Song and Boomgaarden2019). Increased complexity in communication is also regarded a strategy of political de‐politicisation in the face of the rising politicisation and contestation of EU politics – and connected to that, increased public Euroscepticism and surging support for Eurosceptic parties (e.g., Rauh et al., Reference Rauh, Bes and Schoonvelde2020; Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2020; also Flinders & Wood, Reference Flinders and Wood2017).

(2) Executives should ideally allay fears that the situation is out of control and convince the public that they can protect them and restore normality (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart, Stern and Sundelius2005; Heath, Reference Heath, Cook and Holladay2010). Crises are situations of great uncertainty. They primarily induce negative emotions such as anger and sadness, with anxiety being the most dominant one; they also raise positive feelings like hope to overcome or joy about having overcome the crisis (Jin & Pang, Reference Jin, Pang, Cook and Holladay2010). Crisis managers are expected to tackle the situation and address crises, also to warn people and to convey the sense of urgency and emergency needed in order to ensure compliance with countermeasures (Pang et al., Reference Pang, Jin and Cameron2008). They need to deal with emotions, act as coping facilitators, and ensure compliance. Paradoxically, however, excessive labelling of a crisis as ‘crisis’ and emphasizing the threats and uncertainty of the crisis situation may help to induce chaos and increase the likelihood of actually losing control if, for example, the stock market crashes as a reaction. This is because it gives room to the impression that crisis managers do not, in fact, control the situation as they should (Falkheimer & Heide, Reference Falkheimer, Heide, Coombs and Holladay2010). Coming across as anxious and overwhelmed by uncertainty, crisis managers would disappoint public expectations of calm, strong, self‐restrained leadership and risk losing public support (e.g., Collins & Jackson, Reference Collins and Jackson2015). Thus, crisis communication should ideally not convey high levels of anxiety.

(3) The accommodation of the public and crisis‐affected groups of society is essential. Executives can calm the emotions induced by crises by acknowledging peoples’ difficulties, also to ‘praise’ cooperation and thereby foster solidarity in the population and support for crisis measures (Holladay, Reference Holladay, Cook and Holladay2010). By making people visible, crisis managers express their solidarity and sympathy, create a sense of togetherness, to assure that they will not leave people alone with the consequences of crises, but also to foster motivation for the compliance with crisis measures (Jin & Pang, Reference Jin, Pang, Cook and Holladay2010; also Smith & Lazarus, Reference Smith, Lazarus and Pervin1990). In that sense, public crisis communication may range ‘from defensive, putting … [crisis managers’] interests first, to accommodative, putting … [people's] concerns first’ (Coombs & Holladay, Reference Coombs and Holladay2002, p. 171; Van der Meer et al., Reference Van der Meer, Verhoeven, Beentjes and Vliegenthart2014). Being too defensive in the handling of crisis meaning can leave an impression of egoism, carelessness and irresponsibility, in turn leading to a loss of trust, credibility and finally, legitimacy of political institutions (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart, Stern and Sundelius2005; Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Nord and Falkheimer2015). Crisis communication should hence be characterised by inclusion of the people, but also particularly crisis‐affected groups in a society, for example, employees or refugees.

(4) Finally, it is important to convey alignment in political crisis communication to project an image of calmness and strength of leadership to the public (Holladay, Reference Holladay, Cook and Holladay2010). The executive bodies analysed here incorporate different portfolios, for example, ministries or directorates, acting together as a collective, often constituted by parties united in a more or less stable coalition. Crisis situations, however, are prone to nourish rivalries. They open up possibilities for political change where different actors compete for being the most dominant voice in determining the meaning of crisis (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009; Olsson et al., Reference Olsson, Nord and Falkheimer2015). In such a situation, it is crucial for executives to display an image of unity regarding their public crisis communication for at least two reasons: First, the impression that crisis managers are not acting as a united collective will induce anxieties about how well they are able to coordinate and exert the control needed to tackle a crisis situation. Contradictory messages from different arms of the government may cause uncertainty as to which measures exactly should be implemented at all and thereby decrease compliance. Second, they become vulnerable to potentially damaging attacks by political opponents (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart, Stern and Sundelius2005: chapter 3; Van der Meer et al., Reference Van der Meer, Verhoeven, Beentjes and Vliegenthart2014). Therefore, crisis communication would ideally be characterised by political alignment of the involved (collective of) crisis managers.

In conclusion, four dimensions of public political crisis communication seem central for its evaluation: (1) accessibility; (2) allay; (3) accommodation; and (4) alignment. These four dimensions serve as the basis for a similarity index of public political crisis communication that allows to compare the cohesion of crisis‐relevant in contrast to non‐relevant communication, as well as across crisis managers, decoupled from the substantive contents of crisis communication. In order to demonstrate its viability and validity, we apply our framework to 10 years of EU crisis communication to map how executives communicated about crises along these four dimensions.

Data and methods

Period of analysis

We analyse a time frame of 10 years (2009 – 2018) of public political crisis communication by the EU's main executive institutions as well as the governments of Austria, Germany, Ireland and the United Kingdom. Given our ambition to develop a generic approach transcending individual crises and their specific communications, we analyse a period marked by very different crises: The literature distinguishes different phases of crises: pre‐crisis (if applicable), during crisis, and post‐crisis (Coombs, Reference Coombs, Heath and O'Hair2009; Heath, Reference Heath, Cook and Holladay2010). During each of these phases, different expectations are formulated as to what crisis managers ought to do (Palttala & Vos, Reference Palttala and Vos2012). Such phase models of crises are important in developing best‐practice responses and evaluate the contingencies of each individual crisis. They are, however, only of limited usefulness for our purposes given that in our period of analysis, phases of different, independent crises will overlap. In consequence of the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the end of 2008, a global financial crisis developed, and a whole series of crises followed: some directly linked to the financial turmoil, some in other policy fields, for example, in foreign policy, asylum and migration (Börzel, Reference Börzel2016 p. 8), or questioning the existence of the EU as such – Brexit (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2016). These topics are mirrored in the agendas of irregular meetings of the European Council.Footnote 1

Crises all had in common that they questioned the EU's legitimacy in terms of shared values increasingly fundamentally (e.g., Bauböck, Reference Bauböck2018; Börzel, Reference Börzel2016). Born as an economic community, the EU became more and more challenged by ‘the difficulty of striking a normative balance between freedom, security and justice in an increasingly political Union’ (Lavenex, Reference Lavenex2018, p. 1195). These crises were trans‐boundary: the interwoven nature of global political systems accelerated their evolution and spill‐over (Ansell et al., Reference Ansell, Boin and Keller2010), making the EU vulnerable to threats originating in other political contexts. Crises had different consequences in terms of the more or less successful implementation of tackling policies: the European Stability Mechanism, for example, was successfully institutionalised as a consequence of the financial crisis, while the quota system for redistributing refugees amongst member states was not (e.g., Bauböck, Reference Bauböck2018; Börzel & Risse, Reference Börzel and Risse2018; De La Porte & Heins, Reference De La Porte and Heins2016). These trans‐boundary crises, in their unprecedented nature and cross‐border magnitude, developed a strong political dimension globally. For the EU, in particular, they relentlessly revealed the shaky grounds on which this unconsolidated polity is still ‘failing forward’ (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Kelemen and Meunier2016).

Crises created new and deepened already existing divisions amongst member states and the EU's institutions, further eroding the legitimacy and usefulness of supranational cooperation. The involvement of the EU in national politics regarding especially the solution of the financial crisis is considered unprecedented (De La Porte & Heins, Reference De La Porte and Heins2016) and has caused heated contestation and political changes within member states’ societies and political systems (Falkner, Reference Falkner2016; Hernández & Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016). Salience and the resulting contestation of the EU's involvement was mainly influenced by member states’ memberships in crisis‐relevant policies (e.g., Euro area, Schengen), and related to that, how strongly executives and societies were challenged by the crises (debtor vs. donor country, number of asylum applications; see Table 1). Adding to these relevant dimensions of variance, the four countries selected for our analysis also represent member states of different political weight in the EU (length of membership, population, seats in European Parliament, strength of economy [GDP]) which is an important dimension due to the correlating capacity to influence decisions taken during crises and move EU integration forward (or not). Here, especially Germany has always been a motor of EU integration whereas the United Kingdom has traditionally been the strongest pundit. This is also mirrored in governing parties’ stances towards EU integration, displaying the potential for contestation in the standard deviation.

Table 1. Dimensions of variance across the included EU member states

Data

To investigate the public political crisis communication of executives, we rely on press releases as strategic public communication activities and active attempts to influence the public, and especially the media agenda (e.g., Kiousis et al., Reference Kiousis, Popescu and Mitrook2007).Footnote 2 In addition, we use public speeches of the heads of government/leaders of the institutions, thereby including a more direct way of communication by executives into our analysis (e.g., Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Schoonvelde, Traber, Dahiya and Vries2016). Speeches here include speeches to a public audience as well as speeches in parliament.Footnote 3

All available press releases and speeches were scraped from public webpages of the relevant institutions using the R packages rvest (Wickham, Reference Wickham2016) and pdftools (Ooms, Reference Ooms2019). For data cleaning and recoding, we relied on regular expressions, as well as the stringr (Wickham, Reference Wickham2019) and lubridate packages (Grolemund & Wickham, Reference Grolemund and Wickham2011). All included data is in English or German; all analyses were performed on the English and German corpora separately.

Identifying crisis‐relevant communication

Given our ambition to develop a generic perspective on crisis communication, we chose a time frame including large and challenging, but also overlapping, crises of different natures. The actual identification of genuine crisis communications, then, is not straight forward. If we opted for identifying crisis communication irrespective of the topic of the crisis, we would, for example, need to use a search string to filter out texts mentioning ‘crisis’ and related terms. Yet, as discussed for the allay dimension, it would, at least to some degree, be undesirable to use the label ‘crisis’ excessively; we therefore expect that crisis managers would not use it too frequently. Moreover, consequences of crises tend to become more ingrained in politics over time. The actual term ‘crisis’ may then not be uttered in every single instance of crisis communication anymore, thus potentially leaving out a large share of relevant instances.

Instead of looking for the term ‘crisis’, we opted for analysing the whole dataset on all four dimensions as defined above. We then used a topic model to cluster texts into topics given that topic modelling as an unsupervised approach allows exploring the dataset in its entirety rather easily. A dictionary, in contrast, is rather time‐consuming when developed from scratch (e.g., Lind et al., Reference Lind, Eberl, Heidenreich and Boomgaarden2020) and may still miss relevant instances of crisis communication not contained in the dataset used for development. Topic models, nevertheless, have some shortcomings as well. While they are a data‐driven method, topic models require a significant amount of human interpretation of the output. Therefore, a specific cluster of words may be considered to represent different topics by different researchers. Topic models are sensitive to input data and may show different results depending on how parameters are set (e.g., optimal number of topics, word propensities per topic, etc.). These problems are somewhat mitigated by the type of topic model used in this paper: structural topic modelling (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Stewart, Tingley, Lucas, Leder‐Luis, Gadarian, Albertson and Rand2014) utilises spectral initialisation for added model consistency. Overall, yet, topic models remain one of the most useful methods for classifying large text corpora and making sense of this classification.

We drew on external data (i.e., Eurobarometer item ‘What is the most important issue facing the country/EU’, topics of irregular EU‐summits, topics identified in academic literature) to define crisis‐relevant topics, that could potentially address a crisis topic. The topics included can mostly be clustered into the two dominant crises experienced in the time frame 2009–2018, namely the financial crisis with all its subtopics (work and social; taxation; budget; fiscal policy, banks, sovereign debt) and migration and related topics (refugees, asylum, borders, internal security, terrorism). In addition, Brexit and the overall legitimacy and future of the EU were identified as relevant (see online Appendix Tables A1–A5 as well as online Appendix Figures A1‐A5 and B1–B5 for further details). Not all communication about these topics will address them as a crisis issue in every single instance. This selection, however, provides a rather inclusive sample of potentially crisis‐relevant communication.

The full corpus of press releases and speeches consisted of 90,754 documents (40,746 and 50,008 documents in German and English, respectively) within the time frame of 2009 to 2018. For the analysis, we tested topic models with different numbers of topics and finally decided in favour of estimating a 75‐topic model for each country individually, based on the criterion of readability (Maier et al., Reference Maier, Waldherr, Miltner, Wiedemann, Niekler, Keinert, Pfetsch, Heyer, Reber, Häussler, Schmid‐Petri and Adam2018). The total of 5 × 75 topics was then checked and coded for crisis‐relevance by two trained coders separately (initial overall K‐alpha = 0.61, per cent‐agreement at 86.7). Controversial topics (i.e., where coders did not agree on relevance) were then discussed and eventually assigned relevance based on a common discussion of sample documents.

Following our generic approach to the study of public crisis communication, we did not distinguish individual crisis topics but subsumed all relevant communications in one category of ‘crisis‐relevant communication’. After manually classifying topics as relevant/irrelevant to EU crisis communication, there were 15933 English and 9087 German language documents classified as crisis relevant. The texts were classified by the highest probability topic.

Operationalisation and measurement of four dimensions of public political crisis communication

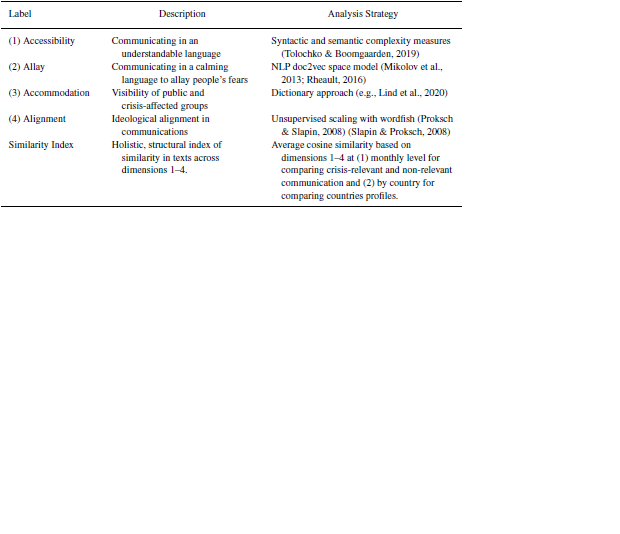

The four identified dimensions of public crisis communication were analysed using different approaches to automated text analysis as summarised in Table 2 (e.g., Boumans & Trilling, Reference Boumans and Trilling2016).

Table 2. Operationalizing four dimensions and a holistic measure of public crisis communication

(1) Accessibility. For analysing the accessibility of the text, two dimensions of text complexity were distinguished. Syntactic complexity relates to the structural characteristics of texts; measures like sentence length, average word length, syntactic depth and syntactic dependency, as well as the automated readability index were used. Semantic complexity relates to content characteristics, like lexical diversity (ratio of unique words to all words in the text), semantic entropy, as well as Yule's I. Based on that, we created composite scores for each of these two dimensions using principal component analysis (Tolochko & Boomgaarden, Reference Tolochko and Boomgaarden2019). However, Tolochko and Boomgaarden (Reference Tolochko and Boomgaarden2019) investigated the effect of different complexity dimensions on language consumption while this paper deals with language generation (for which the effects of these two separate dimensions are still not well understood). Therefore, we made a simplification by averaging semantic and syntactic complexity scores. A complex text thus scores high on both semantic and syntactic complexity. Higher accessibility scores mean less complexity.

(2) Allay. This dimension was included as a ratio of anxiety and calmness in crisis communication. We relied on the word vector model arguing that especially press releases are a rather formalised form of political text where emotions are likely to be communicated in a subtler way than, for example, a dictionary could measure (Rheault, Reference Rheault2016). The initial word2vec model (Mikolov et al., Reference Mikolov, Sutskever, Chen, Corrado and Dean2013) was trained on the English and German Wikipedia corpus. Further, seed words in both languages were selected from a thesaurus, indicating both the states of anxiety and calmness (see Rheault, Reference Rheault2016 on seed word selection and validation of the approach; see online Appendix Table B for our selection of seed words). We calculated the cosine similarity with anxiety and calmness seed words for frequent terms in the model (n > 200). The resulting vectors were then subtracted and normalised to a [−1; 1] interval to create an anxiety measure for each document. Higher allay scores stand for less anxiety in the text.

(3) Accommodation. For assessing the visibility of (crisis‐affected) people, we developed a dictionary. We started by inductively coding relevant terms directly from a random sample of both language corpora. To maintain comparability of the dictionaries, we translated terms missing in one language to the other and checked their validity with key‐word‐in‐context analysis. For validation of the dictionary, we manually coded the relevance of press releases and speeches based on a random sample of crisis‐relevant communications for each language (n = 2 × 200). Reliability of the manual coding was checked by another trained coder based on a sample of 2 × 50 items (K‐alpha = 0.92). In an iterative process, we added and removed terms from the dictionary until we achieved a satisfactory level of precision (0.88) and recall (0.93; e.g., Lind et al., Reference Lind, Eberl, Heidenreich and Boomgaarden2020). German authorities use gender‐neutral language, often leading to the inclusion of the male and the female form of the word in communication (e.g., ‘Bürgerinnen und Bürger’, addressing female and male citizens). In contrast, the grammatical gender has gradually disappeared from the English language (e.g., Curzan, Reference Curzan2003). To avoid a language bias, accommodation is included as the count of unique mentions of dictionary keywords in communication (e.g., ‘Bürgerinnen und Bürger’ and any further mention of the term counted as 1; see online Appendix Table C for our selection of dictionary terms). Higher accommodation scores stand for a higher degree of inclusion of the public in communications.

(4) Alignment. To measure political alignment, we used the unsupervised scaling method wordfish as first introduced by Slapin and Proksch (Reference Slapin and Proksch2008): wordfish works without anchor documents and can scale political documents according to their underlying positions based on word counts. We scaled the documents for each individual country, and then, based on the calculated wordfish score, calculated monthly standard deviations for crisis and non‐crisis texts. We inverted the standard deviations to better connect the measure to our theoretical framework. Therefore higher scores, that is, higher negative monthly standard deviations, correspond to more alignment within crisis‐relevant and non‐relevant texts for a given month for a given country.

Assessing public political crisis communication from a holistic angle

In order to analyse crisis communication in a holistic way, taking into account all four dimensions discussed above, cosine similarity scores were computed between vectors for each month, resulting in an n × n similarity matrix Mijk, where n is the number of observations in a given month i, for a given country j, and relating to crisis‐relevant or non‐relevant topics (k = 1 for crisis‐relevant, k = 0 for non‐relevant); the mean of the similarity matrix was further computed. Thus, each observation in this holistic similarity index is the average cosine similarity score of all communications for one month, country and category (crisis‐relevant/non‐relevant). Each country therefore has up to 120 data points (120 months in the dataset, some countries do not have crisis‐relevant communication in any given month, resulting in a data point exclusion) for each of the two categories – crisis‐relevant and non‐relevant observations.

Methodologically, comparing communication in a cross‐national setting is difficult because of various factors such as cultural, linguistic, and ideological differences, media logics, and so on. With a cross‐national crisis communication comparison, these difficulties are exacerbated simply because of the high stakes of such communication. It is reasonable to expect that texts related to crisis communication would exhibit some form of semantic similarity because they all talk about crises, and perhaps use similar language to describe crises. All of the theoretical dimensions discussed here are prone to be affected by these factors to a lesser or greater extent. Alleviating these concerns, our computed similarity index does not capture the semantic similarity of textual content within one country in a given period. Rather, it is the similarity in crisis dimensions’ scores, that is, in accessibility, allay, accommodation and alignment. The monthly vector scores for these dimensions were mapped onto a four‐dimensional Euclidean space and their cosine similarities compared. Thus, similar texts in this context refer to texts that are similar in terms of how they scored across the aforementioned dimensions, not how they compared in their content characteristics or linguistic specificities. Higher scores on this index imply that accessibility, allay, accommodation and alignment all change in one direction (either positive or negative), while lower scores indicate that these dimensions are distributed less cohesively in texts and do not co‐vary. This similarity index, in sum, allows us to determine the structural rather than content similarity of communication. In addition, it focuses on relative rather than absolute values, and thus easily allows a comparison of different groups within the data, notwithstanding their size (e.g., countries/EU, crisis‐relevant communication vs. non‐relevant communication).

Results

To understand the distinct patterns in crisis‐relevant communication, we contrasted it to non‐relevant communication to test the validity of our framework. To that end, a series of Welch two sample t‐tests were conducted for the accessibility, allay, accommodation and alignment dimensions first to compare their means. Figure 1 shows each of the pair‐wise comparisons for each dimension/country combination (results for speeches and press releases separately were very similar, please refer to online Appendix Figures C1 and C2 for separate figures for press releases and speeches respectively).

Figure 1. Individual Crisis Dimensions (Crisis‐relevant vs. non‐relevant communication). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: White dots represent the mean of non‐relevant observations ‐ mean of crisis‐relevant observations with 95% confidence interval plotted around the mean. Dotted line is 0. If the parameter is on the left of the vertical line, the mean is higher in crisis‐relevant communication and vice versa. All variables are normalized to (M = 0; SD = 1).

The results demonstrate that, while there are certain tendencies and clusters across countries with regard to their crisis communication, it is difficult to discern one concrete pattern. Accommodation shows similar scores across all sources, that is, texts tend to refer to people more frequently when dealing with a crisis‐relevant topic. Also, the allay dimension differs similarly across countries, showing that crisis‐relevant communication is overall characterised by lower allay scores, thus higher anxiety. The exception is Ireland, where there is no significant difference in anxiety in crisis‐relevant versus non‐relevant communication. Accessibility tends to vary from country to country – German and EU communications tend to be less accessible, while Irish and Austrian communications tend to be more accessible when dealing with a crisis. No significant difference is observed for the United Kingdom. Finally, crisis‐relevant communication tends to be more ideologically aligned than non‐relevant communication for Ireland and the United Kingdom; the opposite is, however, true for both the EU and German communications while there is no significant difference for the Austrian case.

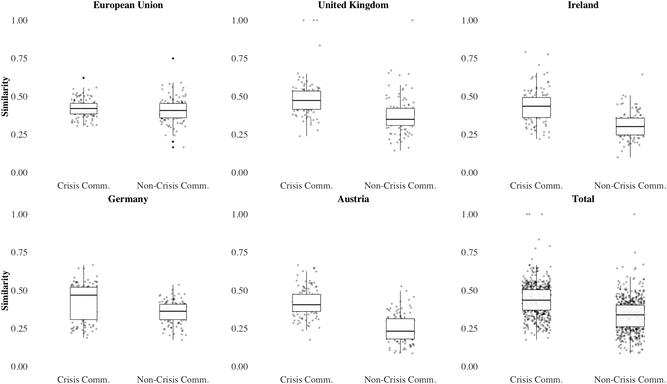

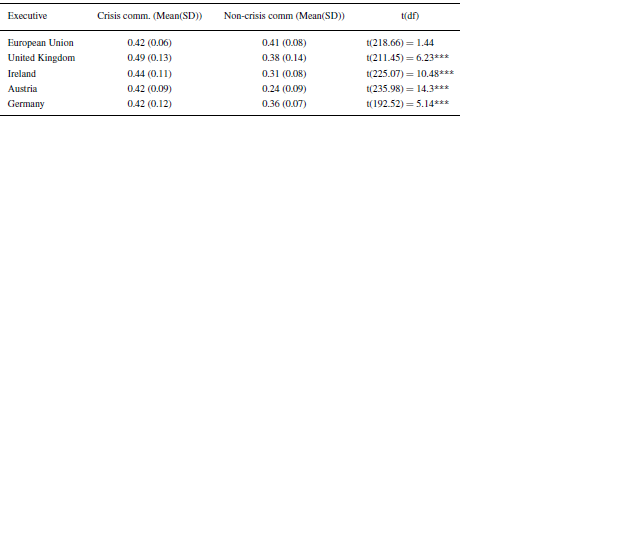

To analyse the overall cohesion of communications across the four dimensions, we calculated the holistic similarity index (see methods section) which gives us more abstract information about how similarly press releases and speeches scored across the four dimensions. Boxplots for countries visualise the difference in similarity indices for crisis‐relevant and non‐relevant communication in Figure 2. Again, a series of Welch two sample t‐tests were conducted to determine whether the similarity index on average is different for crisis‐relevant and non‐relevant communication. The results are reported in Table 3.

Figure 2. Crisis‐relevant vs non‐relevant communication by country.

Table 3. Mean comparison of similarity scores. welch two‐sample t‐tests

Note: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

The results show that for four out of five cases, crisis‐relevant communication is more cohesive with regards to its structure than non‐relevant communication. Within one month, thus, crisis texts tend to be more similar in how they reflect all of the aforementioned crisis dimensions – accessibility, allay, accommodation and alignment. The exception in our sample is the EU for which cohesion in both categories of communication is similar and thus, differences between crisis‐relevant communication and non‐relevant communication are not significant.

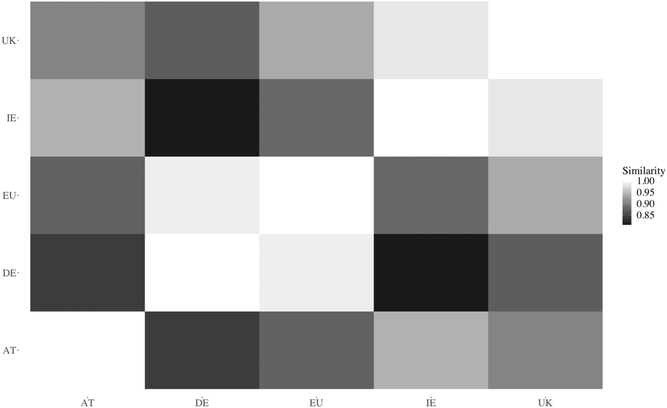

We additionally compared the similarity index across cases to understand how differently challenged crisis managers performed in comparison. For that purpose, instead of aggregating at the monthly level, all crisis‐relevant texts were aggregated at the country level, thus giving us one value of average cosine similarity by country. Figure 3 shows how similar (lighter shade) – or dissimilar (darker shade) – the countries are from each other in their crisis‐relevant communication.

Figure 3. Differences in average cosine similarity across countries.

Note: The figure is based on average cosine similarity measures by country. Lighter shades stand for greater similarity (comparison of average cosine similarity of the two cases), darker shades stand for lower similarity of two cases.

Germany, here, seems to be the least similar to other crisis managers, located most closely to the EU, while being the most dissimilar match for the other three member states, especially Ireland. The three member states, Austria, Ireland, and the UK, indeed cluster in their similarity of crisis communication: Austria is most similar to Ireland; Ireland and the UK, in turn, are very similar, while the EU as the political umbrella of all four member states in this analysis, is closest to Germany.

Discussion and conclusion

Looking first at the four dimensions of crisis‐relevant communication separately (see Figure 1), we see similar behaviour regarding accommodation and allay as crisis managers as they tended to communicate in more anxious language and refer to people more often regarding crisis‐relevant topics. With regard to accessibility and alignment, however, crisis‐relevant communication was quite inconsistent across countries.

Relating back to our framework, it seems that crisis managers did what was expected from them in that they accommodated the public and crisis‐affected groups, which also resonates with research on strategic political communication more generally (e.g., Strikovic et al., Reference Strikovic, Meer, Goot, Bos and Vliegenthart2020). Results for the alignment measure may be a mirror of doubt and dissensus about how to tackle crises, but also how to further develop the European project in the face of crises and rising Euroscepticism: especially in traditionally pro‐EU countries like Germany, but also in the EU as such for which all of the crises represent a fundamental questioning of its existence (Börzel, Reference Börzel2016). Results for accessibility of information partly resonate with Rauh et al. (Reference Rauh, Bes and Schoonvelde2020) who found an almost unchanged higher level of complexity in EU commissioners’ communication over the course of the Eurocrisis while national leaders’ communication became much clearer. Germany, here, is clearly an exceptional case with decreased levels of accessibility in its crisis communication overall.

In terms of allaying peoples’ fears, the same or higher levels – certainly not significantly lower levels – for crisis‐relevant communication could have been expected in line with our framework. Even considering that a crisis situation needs to be discussed, defined, evaluated and its urgency conveyed, it seems that executives did not manage to communicate to the media and the public that they would steer calmly through crisis‐troubled waters. In contrast, executives might have helped in initiating and maintaining the ‘crisis’ momentum. Relating back to the societal developments we have seen over the last 10 years, such anxious rhetoric, thus, may well have contributed to empowering populist or even anti‐democratic political forces capitalizing on peoples’ frustrations and anxieties (e.g., Moffit & Tormey, Reference Moffitt and Tormey2014; Hobolt & De Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2016).

Overall, the crises we witnessed over the last decade challenged and overwhelmed politicians and societies globally; thus, one reason for being less aligned, or communicating anxieties and complexity in crisis‐relevant communication, may have been the fundamental uncertainty of the whole situation as such – as the example of COVID‐19 vividly illustrates. In addition, the EU is a polity in the making, and crises made the unfinished nature of the political and legal construction of the EU and its consequences apparent. Some fundamental changes were brought about (De la Porte & Heins, Reference De La Porte and Heins2016), testing member states’ willingness to politically commit to the project in the long run while accepting short‐term losses for the gain of a (future) greater political good (Bauböck, Reference Bauböck2018; Börzel, Reference Börzel2016). Anxieties, more complexity, or less alignment, could thus mirror the uncertainties of crises, but also the uncertainties of the future of the EU and member states’ role in it.

However, regarding anxiety in particular, politicians could have used anxious language strategically to get attention from the media and the public. Linking to the literature on newsworthiness, crises have been found to possess an inherent news value (Heath, Reference Heath, Cook and Holladay2010, p. 1) due to multiple dimensions of uncertainty, augmented by framing contests between different (powerful) groups of societies that claim to define what happened and how the crisis should be solved. In addition, studies have also shown how crises can change established media logics and give room to previously unheard voices (Figenschou & Beyer, Reference Figenschou and Beyer2014). Executives would, thus, have an interest in strategically defining and making salient their own interpretation of the crisis while presenting themselves as the most adequate and able crisis managers. In this vein, the literature has discussed how political decisionmakers, especially in international organisations like the EU, may strategically attempt to maintain the crisis momentum to expand their discretionary powers, also to secure their own authority in the face of weakening representative ties with their electorate (Kreuder‐Sonnen, Reference Kreuder‐Sonnen2019; Merkel, Reference Merkel2020; White, Reference White2019). The legitimation of crisis politics would, in that sense, be a strategy aiming to foster the public conviction that the (long‐term) increase of executive powers is essential to tackle this exceptional state of emergency. Such a strategy would then basically follow a more general rationale of what has been discussed as the ‘politics of fear’ (e.g., Altheide, Reference Altheide2002; Wodak, Reference Wodak2015).

Zooming out of the individual dimensions and turning to the similarity index, results mostly foster the viability and validity of our approach. The EU sticks out as the one case in which crisis‐relevant communication does not significantly differ from non‐relevant communication (see Figure 2 and Table 3). The EU's competencies to implement EU‐wide measures to tackle the financial crisis remained very limited in the beginning of our period of analysis, as is, for example, documented in the judgment of the German Federal Constitutional Court of September 2011 (BVerfG, 2011). EU communication may, thus, have discussed crisis topics during that time, but not with the same sense of urgency due to the missing executive authority to tackle it. Another similar interpretation, again resonating with the difference between the national and the EU level as discussed by Rauh et al. (Reference Rauh, Bes and Schoonvelde2020), may be the following. The EU as a compound polity, thus a still unconsolidated composite of individual member states, may be characterised rather by a ‘coordinative’ discourse amongst policy makers than by ‘communicative’ discourse which happens between policy makers and the public (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2008). EU institutions’ press releases and speeches, then, would be less targeted at gaining acceptance of political output with European citizens in terms of legitimacy, but more to coordinate policies amongst the political decisionmakers involved. This may explain why our framework, targeted to evaluate crisis legitimation, does not hold in the same way for the EU as for national governments.

Beyond the special case of the EU, results in essence support the findings of Kleinnijenhuis and colleagues (Reference Kleinnijenhuis, Schultz and Oegema2015), who show that communication becomes less complex and multifaceted during times of crisis. The similarity index does not measure complexity directly, but rather provides an indication that crisis‐relevant communication is less variable in the analysed dimensions than non‐relevant communication, thus, supporting the conclusions by Kleinnijenhuis et al. (Reference Kleinnijenhuis, Schultz and Oegema2015), but from a different methodological perspective. In that sense, our similarity index may also be related to Suedfeld and Tetlock's (Reference Suedfeld and Tetlock1977) idea of integrative complexity, specifically, the differentiation aspect, which refers to the dimensions of communication and postulates that even complex communication should include a significantly varied multidimensional character. The similarity index, then, would show whether this characteristic (in a predetermined set of dimensions) is varied or coherent (as is the case in the current paper).

Regarding, finally, differences amongst crisis managers as shown in Figure 3, our results provide validation that the similarity index taps more than simply linguistic (i.e., German vs. English) features of the text, but actually provides structural information. Germany sticks out as a special case, being closest to the EU, whereas Austria, Ireland and the United Kingdom build a camp of their own. While these results merit further attention, clusters may be distinguished from one another in how they were affected by and/or reacted to crises (see also discussion of our case selection). Ireland as the only debtor country in the sample, needed to subordinate itself to unprecedented involvement from the EU in exchange for financial help during the Eurocrisis (Thorhallsson & Kirby, Reference Thorhallsson and Kirby2012); Austria became strongly affected by the migration crisis which led to a political shift to the right (Heinisch et al., Reference Heinisch, Werner and Habersack2020); and the United Kingdom decided to leave the EU altogether (Hobolt, Reference Hobolt2016). The EU, most fundamentally questioned by all crises, has consistently, more or less successfully, pursued its aim to maintain the legitimacy of EU politics (Bauböck, Reference Bauböck2018; Börzel & Risse, Reference Börzel and Risse2018). Germany, while affected especially by the migration crisis, has witnessed the first real establishment of a right‐wing populist party on the national stage (Arzheimer & Berning, Reference Arzheimer and Berning2019) but has remained the strongest pro‐EU integration motor throughout these challenges, also owing to the continuous and stable leadership of Angela Merkel (Bulmer & Paterson, Reference Bulmer, Paterson, Dinan, Nugent and Paterson2017). Differences in the structure of crisis communication may be read before this backdrop, especially regarding the political decision to remain a supporter and driver of the European project, and thus subscribe to the idea of supranational integration also at the cost of national sovereignty – or not.

Concluding, this study set out to conceptualise, operationalise and map different dimensions of crisis communication by the EU and four EU member states with different stakes and reactions to crises that occurred in the last decade. We defined four dimensions of public crisis communication developed along the rationales discussed in the crisis management literature: allay, accessibility, accommodation and alignment, consolidated in a holistic similarity index. Overall, results confirm the validity of the framework in that crisis‐relevant communication was mostly found to be significantly different from non‐relevant communication. Methodologically, we demonstrated that cosine similarity is useful in more ways than just for measuring semantic similarity, as is its predominant utilisation in the social sciences. Any application, where some sort of cohesion of dimensions is of interest – whether simple content dimensions, like vector space representation of texts, or more complex constructed dimensions as used in this paper – cosine similarity is a powerful metric that can provide utility in characterising cohesion in a multidimensional space.

Regarding limitations, the aim was to introduce a novel framework and demonstrate its viability and validity. Therefore, and accordingly, the substantial discussion of empirical results needed to remain somewhat limited and should be subject to further analysis. The richness of the data and analysis strategy is expected to trigger more substantial and explanatory engagement with EU crisis communication, especially regarding multilevel dynamics and the differences between national and EU level communications. Moreover, the sample would need to be larger and more diverse in order to further corroborate the validity of a four‐dimensional approach. It would, for example, be highly desirable to include EU member states in Central and Eastern Europe, some of which do continue to test the overall political cohesion and resilience of the EU as such, but also Greece, Italy or Spain as those member states hit hardest by crises. Moreover, we used a bilingual dataset to explore the validity of our approach, which was also a pragmatic decision. Relating to the (still) prevailing challenges that come with using automated approaches on a multilingual text corpus, only having to deal with English and German was an asset since most advancements in computational social science have been made in these two languages (see, e.g., Lind et al., Reference Lind, Eberl, Heidenreich and Boomgaarden2020). In that way, we were able to use some already tested instruments and thereby keep the still quite comprehensive effort of measuring our four dimensions of public political crisis communication within a manageable frame. Using this approach for future applications in other cases, however, could potentially enlarge the workload when attempting to accommodate more languages or having to invest into translations first.

Notwithstanding these limitations, we have provided evidence for the viability and validity of a novel, holistic way of looking at political crises and their public legitimation. We were able to illustrate the differences of how governments communicated about crisis‐relevant and non‐relevant topics from a generic perspective, providing a new analytical lens to confront the crisis aspect of legitimation efforts explicitly. Future work will delve deeper into more fine‐grained analyses of changes over time and factors that help to explain EU executives’ public crisis communication. Yet, we hope that the current paper will act as a starting point for a more in‐depth and at the same time abstracted investigation into the nature and management of (multi‐)national crises. In that way, more targeted empirical analyses of crisis communication could help to further theories and eventually also the practice of EU integration.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Loes Aaldering, Verena K. Brändle, Hyunjin Song and Veronika Wenninger for their support and feedback on earlier versions of this article. In addition, we would also like to thank Isabelle Engeli and the three anonymous reviewers of the European Journal for Political Research for their constructive comments. We furthermore acknowledge the funding by the Austrian Science Fund (Hertha‐Firnberg Program, Grant No. T 989‐G27) for Olga Eisele.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix Table A1: Relevant Topics with Label Terms for AT Sample

Appendix Table A2: Relevant Topics with Label Terms for DE Sample

Appendix Table A3: Relevant Topics with Label Terms for EU Sample

Appendix Table A4: Relevant Topics with Label Terms for IE Sample

Appendix Table A5: Relevant Topics with Label Terms for UK Sample

Appendix Table B: List of seed words for Allay measure in English and German

Appendix Table C: Dictionary terms for Accommodation Measure (visibility of crisis victims in communications)

Appendix Figure A1: Highest Word Probabilities for Relevant Topics AT

Appendix Figure A2: Highest Word Probabilities for Relevant Topics DE

Appendix Figure A3: Highest Word Probabilities for Relevant Topics EU

Appendix Figure A4: Highest Word Probabilities for Relevant Topics IE

Appendix Figure A5: Highest Word Probabilities for Relevant Topics UK

Appendix Figure B1: Visualisation of Topic Proportions for Relevant Topics AT

Appendix Figure B2: Visualisation of Topic Proportions for Relevant Topics DE

Appendix Figure B3: Visualisation of Topic Proportions for Relevant Topics EU

Appendix Figure B4: Visualisation of Topic Proportions for Relevant Topics IE

Appendix Figure B5: Visualisation of Topic Proportions for Relevant Topics UK

Appendix Figure C1: Scores for four dimensions of crisis communication for press releases

Appendix Figure C2: Scores for four dimensions of crisis communication for speeches

Data Replication Statement