Introduction

Violence against political elites is on the rise across advanced industrialized societies. Brutal manifestations of this trend include the shooting of U.S. House Majority Whip Steve Scalise or the murder of Labour MP Jo Cox in 2016, but less severe forms of political violence are widespread, particularly in local politics. In a survey among British candidates, one third of all respondents indicated that they had experienced intimidating behaviour (Collignon & Rüdig, Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020). In a 2021 survey, 72 per cent of over 1600 German local politicians reported that they had been the target of verbal or physical abuse (Kommunalmagazin, 2021).

Beyond the magnitude of violence, it is concerning that members of groups, already underrepresented in politics, such as female politicians, tend to disproportionately become the targets of attacks (Collignon & Rüdig, Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020; Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2021). This raises our central research question: Does indirect exposure to political violence further exacerbate gender gaps in political ambition and descriptive representation? This is an important question because descriptive representation can translate into improved substantive representation (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1999; Wängnerud, Reference Wängnerud2009). In addition, the legitimacy of representative democracy can be undermined if the socio‐demographic composition of the political elite pool deviates too strongly from the underlying population (Arnesen & Peters, Reference Arnesen and Peters2018).

We argue that violence may deter women more strongly than men from political activity since political violence is disproportionately directed against female candidates and officeholders (Buckley et al., Reference Buckley, Keenan and Mariani2024; Collignon et al., Reference Collignon, Campbell and Rüdig2022; Daniele et al., Reference Daniele, Dipoppa and Pulejo2023; Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2021; Krook, Reference Krook2020; Krook & Restrepo Sanín, Reference Krook and Restrepo Sanín2020). Moreover, the prevalence of political violence may serve as a signal of ‘nasty’ politics, which women tend to dislike (Fridkin & Kenney, Reference Fridkin and Kenney2011, p. 315; Kanthak & Woon, Reference Kanthak and Woon2015). Finally, gender differences in risk aversion could result in differential reactions to political violence (Croson & Gneezy, Reference Croson and Gneezy2009).

Although closely related to recent work on the consequences of violence and hostility against women candidates and elected politicians for women's political representation (Bjarnegård et al., Reference Bjarnegård, Håkansson and Zetterberg2022; Buckley et al., Reference Buckley, Keenan and Mariani2024; Daniele et al., Reference Daniele, Dipoppa and Pulejo2023; Eady & Rasmussen, Reference Eady and Rasmussen2024; Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, Håkansson and Josefsson2023; Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2024a, Reference Håkansson2024b; Herrick et al., Reference Herrick, Thomas, Franklin, Godwin, Gnabasik and Schroedel2021), our research goes beyond these studies by examining indirect exposure to political violence and its effect on willingness to run and descriptive representation.Footnote 1

We focus on Germany, where women are strikingly underrepresented in local politicsFootnote 2 and where attacks against politicians increased dramatically. In 2023, the number of attacks grew by 30 per cent compared to 2022 (Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat & Bundeskriminalamt, 2024). Surveys of local politicians suggest that women are disproportionately targeted (Kommunalmagazin, 2020).Footnote 3

Our empirical analysis relies on two sources of evidence. First, we examine the relationship between attacks on politicians and the proportion of female candidates in German local elections using novel data from over 2000 municipalities. Second, we employ pre‐registered survey experiments (N = 3590) to expose respondents to information about political violence and measure its effects on political ambition.Footnote 4 We use different samples based on respondents’ political interests to assess their likelihood of considering candidacy.

We find no evidence that attacks on politicians reduce the proportion of female candidates in affected municipalities. Our experiment shows that information about political violence does not disproportionately discourage women with high political interest from running for office; if anything, it may reduce men's willingness to engage in politics. While risk aversion and a preference for cooperation do not moderate treatment effects, our treatment increases the perceived risk of being targeted. Among women with low political interest, there is some evidence that political violence may diminish political ambition in this group.

Overall, our findings suggest that indirect exposure to political violence per se may not further undermine the descriptive representation of women. They are also consistent with research showing that political ambition and engagement can increase when women are exposed to policy threats (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2023) or threats of sexual violence (Kreft, Reference Kreft2019). Furthermore, our study adds to our understanding of the conditions under which salient violence may or may not reduce women's political engagement (Hadzic & Tavits, Reference Hadzic and Tavits2019). Our results also highlight the need to sample relevant populations, as more likely candidates and highly engaged constituents may differ in important ways from the general population (see Magalhães & Pereira, Reference Magalhães and Pereira2024). Finally, our findings suggest that political violence can create a pipeline problem if it discourages the larger population of women from even considering running for office.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Why should the prevalence of political violence affect the gender gap in political ambition and descriptive representation? We propose three non‐mutually exclusive factors: The gendered nature of political violence, potential gender differences in risk aversion and a potentially stronger preference for cooperation and civil politics among women.

First, indirect exposure to political violence may curb women's political ambition and create a gender gap in descriptive representation if women anticipate to be at greater risk in the political arena. Departing from the finding that political violence is disproportionately directed against women (Collignon et al., Reference Collignon, Campbell and Rüdig2022; Daniele et al., Reference Daniele, Dipoppa and Pulejo2023; Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2021; Krook & Restrepo Sanín, Reference Krook and Restrepo Sanín2020; Krook, Reference Krook2020; Yan & Bernhard, Reference Yan and Bernhard2024), scholars have found that attacked female politicians are less likely to re‐run (Daniele et al., Reference Daniele, Dipoppa and Pulejo2023) and are more likely to consider leaving politics (Håkansson, Reference Håkansson2024b). These effects of direct attacks could spill over to women more generally given more widespread experiences of gendered physical violence and abuse among women (see, e.g., Müller et al., Reference Müller, Schröttle, Glammeier and Oppenheimer2007). This societal background matters because hostility towards women in politics is not only perceived by citizens and politicians as more severe but also perceived as attempts to remove women from politics (Eady & Rasmussen, Reference Eady and Rasmussen2024). In consequence, even women who are not directly targeted may anticipate the gendered nature of political violence resulting in a lower willingness to run for office among women generally and higher dropout among female candidates compared to male counterparts.

Research on other types of violence lends some empirical support to this notion. For instance, Hadzic and Tavits (Reference Hadzic and Tavits2019) show in a survey experiment that making past wartime violence salient reduces women's willingness to participate in politics more than men's. Similarly, providing cross‐national evidence, Wood (Reference Wood2024) finds that electoral violence is linked to fewer women in elected office.

Second, if women are more risk‐averse than men, they may be more likely than men to factor in the costs of running in a contentious political environment. Although evidence has suggested an existing gender gap in risk aversion in the general public (Croson & Gneezy, Reference Croson and Gneezy2009; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Soane, Fenton‐O'Creevy and Willman2005; Pate & Fox, Reference Pate and Fox2018), it is unclear to what extent this gender gap generalizes to potential political candidates and politicians. For instance, Magalhães and Pereira (Reference Magalhães and Pereira2024) show that female candidates are actually less risk‐averse than their male counterparts. Similarly, Linde and Vis (Reference Linde and Vis2017) find no gender differences in risk preferences among Dutch MPs. To take this heterogeneity into account, we use a distinct, pre‐treatment measure of risk aversion in our surveys to test this mechanism.

Third, the prevalence of political violence marks politics as contentious and ‘nasty’. Evidence suggests that this may deter women in particular because they dislike uncivil campaigning (Fridkin & Kenney, Reference Fridkin and Kenney2011, p. 315) and tend to adopt a more cooperative style of politics (Childs, Reference Childs2004). Accordingly, Kanthak and Woon (Reference Kanthak and Woon2015, pp. 603–604) find no gender gap in willingness to run for office when campaigning is guaranteed to be honest and truthful and the cost of competing is low. Similarly, Preece and Stoddard (Reference Preece and Stoddard2015) find that priming the competitiveness of the political arena reduces women's interest in political office but not men's. Finally, Schneider et al. (Reference Schneider, Holman, Diekman and McAndrew2016) provide evidence that women's lack of interest in power and conflict can partly explain the gender gap in political ambition. This hypothesized dynamic is not specific to the political domain: Previous research has, for instance, linked sexual harassment to gender‐specific labour market flows (Adams‐Prassl et al., Reference Adams‐Prassl, Huttunen, Nix and Zhang2024; Batut et al., Reference Batut, Coly and Schneider‐Strawczynski2022; Folke & Rickne, Reference Folke and Rickne2022). These studies show that women are less likely to apply for jobs in workplaces with a higher risk of sexual harassment even if alternative jobs offer lower wages. In conclusion, women's preference against ‘nasty politics’ could cause indirect exposure to political violence to widen the gender gap in political ambition.

All three rationales suggest that the prevalence of political violence increases the gender gap in politics. Combining observational data on politically motivated crimes and the share of female candidates on local party lists, we test the following observational implication of this argument:

H1: Fewer women will run for political office in municipalities that have experienced more crimes against politicians.

Focusing on individuals’ political ambition, we test the following individual‐level implication of our argument in an experimental setting:

H2: Informing individuals about the prevalence of political violence will reduce their willingness to run for office and engage in politics more strongly among women than among men.

To shed light on the underlying mechanisms, we focus on two potential moderators discussed above, namely risk aversion and preference for cooperation in politics:

H3: Informing individuals about the prevalence of political violence reduces their willingness to run for office and engage in politics. This effect should be stronger when interacting with the treatment with risk aversion.

H4: Informing individuals about the prevalence of political violence reduces their willingness to run for office and engage in politics. This effect should be stronger when interacting with the treatment with a preference for cooperation over competition in politics.

Empirical strategy

Observational data

Sample

We combine administrative data on crimes against politicians and political parties with administrative data on the share of female candidates on party lists in municipal elections in five German states. Our sample on the share of female candidates covers 4886 party lists in 2079 municipalities from the 2014 and 2019 municipal elections in Baden‐Württemberg, Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia as well as the 2016 and 2021 elections in Hesse. The five states are inhabited by 23 million people, or roughly 25 per cent of the German population. To these data on female candidacies, we match the number of politically motivated crimes in the respective municipality, originating from previously classified police reports of the German Federal Crime Office (BKA). We describe the sample and data origin in more detail in the Online Appendix Sections C.1 and C.2.

Independent variables

Our independent variables capture the prevalence of crime in a municipality in the 12 months ahead of the municipal elections. We distinguish between three forms of attacks against politicians. First, we create a binary and a count variable, respectively, for Any Political Crime(s) against political representatives or party infrastructure in a municipality. This includes minor crimes against party campaign material, such as the demolition of posters. We further create a binary and a count variable capturing any Attack(s) against Politicians. Finally, we also assess the influence of Severe Attacks against Politicians on female candidacies by focusing on serious physical and/or psychological abuse. We find that the severe attacks are regularly covered by local media outlets and should be salient enough to sway attitudes of other local politicians in the area (see MDR Sachsen, 2024, and NDR, 2024, for examples of local coverage). The data on crime stem from the official database of politically motivated crimes (PMC) by the German Federal Crime Office, which was published due to parliamentary inquiries. More information on their origin and the documents that contain information on attacks is presented in Sections C.1 and Table C.1 of the Online Appendix.

Outcome

The Change in the Share of Female Candidates between municipal council elections constitutes the outcome of interest. For each municipality, we calculate the difference in the average share of female candidates of the six main parties – CDU, SPD, Greens, FDP, Linke and AfD – between the two local elections.

Examining the share of female candidates in municipal elections is ideal for assessing the impact of PMCs on women in politics. Interviews with local representatives and additional evidence (see Online Appendix Sections B and C) suggest that party list nominations face fewer confounding factors at the local level. In fact, 68 per cent of municipal party lists in our data struggle to fill positionsFootnote 5 and thus rely on volunteers from the community, reducing the influence of party quotas and gatekeepers. For progressive parties with formal quotas, the average female candidate share is only 17 per cent and changes in the share are similar to parties without quotas (see Online Appendix Section C.5). Candidate willingness to engage with a party is therefore crucial in determining potential candidacies (see the evidence presented in Online Appendix Section B.1).

Covariates and estimation

In all models, we control for municipal‐level differences in population and population density. We also include state and election‐year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered by municipality.

Survey experiments

To measure the gendered effects of indirect exposure to political violence on political ambition, we conducted survey experiments in Germany.

Sample

We use the online access panel of the survey firm Bilendi. Overall, we recruited 3590 respondents across three surveys (July 2022; August/September 2022; December 2022), 50 per cent of whom are female.Footnote 6 Our main analysis focuses on respondents with high political interest (five or higher on a seven‐point scale), as they have a higher baseline probability of running for public office. This decision is based on qualitative evidence (Alin et al., Reference Alin, Bukow, Faus, John and Jurrat2021, pp. 17–18) suggesting that local political candidates in Germany often enter politics due to intrinsic motivation or recruitment by peers, rather than strategic career goals. Given the lack of a clear pathway into candidacy, we consider political interest as a necessary condition that creates a sample that arguably has a higher propensity to run for local office than an alternative sample that would not be filtered by political interest.Footnote 7

Our interviews with local party organizers (see Online Appendix B) revealed that recruiting candidates at the local level is difficult, often resulting in unfilled spots on party lists – only 32 per cent of local lists have a full slate. This lack of competition suggests that highly politically interested individuals may not only be more motivated but also better positioned to run for office. Nevertheless, in a secondary analysis, we examine whether political violence affects political ambition differently among respondents with varying levels of political interest, using data from our third survey, which includes individuals with lower political interest.

Treatment

We rely on an information treatment. In the control condition, we use a text to inform respondents about the importance and tasks of local politicians in Germany. The treatment condition includes an additional paragraph indicating that local politicians increasingly become targets of politically motivated crimes, accompanied by a graphical representation of the trend in crimes against politicians in Germany between 2019 and 2021. The exact treatment wording and the corresponding graph can be found in the questionnaire in Online Appendix F.5. (See Online Appendix E.3 for balance tests.)

We refrained from using a treatment that explicitly mentions the disproportionate targeting of women. First, our theoretical mechanisms summarized in H3 and H4 do not rely on priming disproportionate targeting by gender. Rather, if men and women differ in their risk aversion and their preference for political style, violence should generally result in gendered reactions. Second, due to a lack of reliable data on the gendered nature of political violence in Germany, we refrained from providing respondents with information that we were not able to fully back up with data. Finally, we wanted to ensure the experimental portion of the study to be compatible with our observational analysis, where we do not differentiate political violence by gender due to data availability reasons.

Another concern with the information treatment is whether it provides novel information to respondents, especially those with high political interest. A systematic analysis using the Nexis Uni database found only 419 articles on violence against politicians published in German newspapers in the last 5 years – compared to 1708 articles on violence against another type of public official – the police. This suggests that public awareness of violence against politicians is relatively low, making our treatment likely to introduce novel information to many respondents.

Outcomes

Our main outcomes of interest tap into respondents’ willingness to run (WTR) as a candidate in local council elections in their municipality and, as a lower level measure of participation, their willingness to engage (WTE) in the local politics of their community. Following Mendelberg and West (Reference Mendelberg and West2021), we additionally designed a quasi‐behavioural outcome in which we provided respondents in the first two survey rounds with the option to learn more about administrative steps required for candidacy by clicking on a separate page (henceforth Information outcome). We measure whether a respondent opted to view the information as a binary outcome. Finally, as secondary outcomes, we examine the treatment effect on respondents’ perceived personal danger/risk of candidacy (included in rounds one and two) and political engagement (included in all three rounds). The purpose of these outcome variables is to check if the treatment is strong enough to have any effect on respondents’ beliefs since exposure to information about political violence should most directly affect risk perceptions.

Attitudinal pre‐treatment moderators

We measure risk aversion using four items from the General Risk Propensity Scale (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Highhouse and Nye2019), creating an index from one to five, with higher values indicating greater risk aversion; this was measured in the first two surveys. Preference for a cooperative political style is measured with a binary indicator: one if the respondent values cooperation and consensus over competition and conflict in democratic politics and zero if they do not. This was included in all three surveys.

Results

Observational analysis

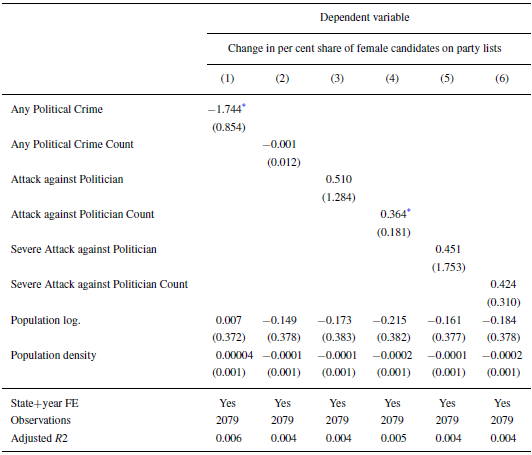

Table 1 shows the results of six linear regression models assessing the effect of political crime on female representation in German local elections.

Table 1. Political crime and female candidates in municipal elections

Note: The table presents the results of multivariate ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions on the municipality level. All models include the log population and population density as municipal‐level covariates as well as state and election year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered on the municipal level.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

According to model one, we observe a decline in the share of female candidates by roughly 1.7 percentage points when a municipality was exposed to at least one political crime, which includes less severe crimes like property damage. However, the count‐based models show that higher crime rates do not translate into fewer female candidacies. When excluding less severe crimes in models 3–6, we show that (severe) attacks against politicians do not reduce female representation in party lists. If anything, the estimates skew positive and mostly become statistically insignificant. These results persist if we omit any specific party in our sample (see Online Appendix Section C.5). In additional tests presented in Online Appendix Section C.4, we show that our outcome does not predict the occurrence of crime and that results are similar when looking at levels instead of within‐municipality changes in the share of female candidates. We also do not find any evidence that political crime is systematically related to the position of women on candidate lists (see Online Appendix Section D). Finally, our results are similar in contexts with high or low levels of female representation (see Online Appendix Section C.7).

Overall, we conclude that political violence – both in terms of quality and quantity – does not systematically correlate with the descriptive representation of women (in contrast to H1). This suggests the resilience of female politicians in the face of adverse political conditions.

Survey experiments

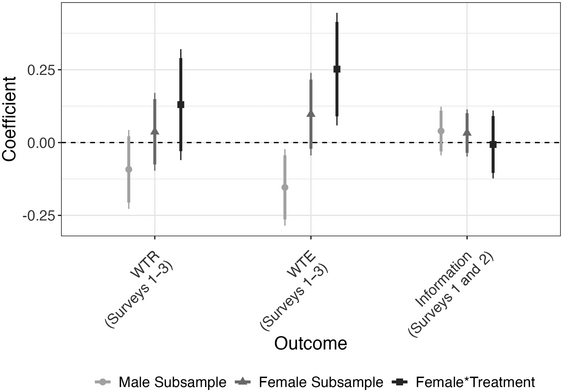

The results of the survey experiment reflect the findings from the observational analysis. As Figure 1 demonstrates for our three main outcome variables, there is no negative interaction effect between exposure to information about political violence and the dummy indicator for female respondents with high political interest (H2).Footnote 8 If anything, exposure to information about violence against politicians may actually reduce the gender gap, given the positive interaction effect for WTE as the outcome variable. This result is driven primarily by male respondents, who are deterred by our treatment, while female respondents are unaffected by it. There is, however, no difference in the treatment effect between males and females for WTR and the quasi‐behavioural information outcome.Footnote 9 In sum, contrary to our hypothesis, informing respondents with high political interest about the prevalence of political violence does not have a stronger deterrent effect on women's political ambitions than on men's.

Figure 1. Treatment effects on primary outcomes by gender.

Note: OLS coefficients with 90 per cent (thick bars) and 95 per cent (thin bars) confidence intervals based on robust standard errors. WTR and WTE range from 1 (“very unlikely”) to 5 (“very likely”). Information is a binary outcome. Within‐subgroup and interaction coefficients were estimated in separate models. Models with WTR or WTE as the outcome include a dummy indicator for the third survey. (See Online Appendix Figure E.6 for results using indices and alternative outcome measures and Online Appendix Table E.3 for full model results.) The analysis is restricted to respondents with high political interest.

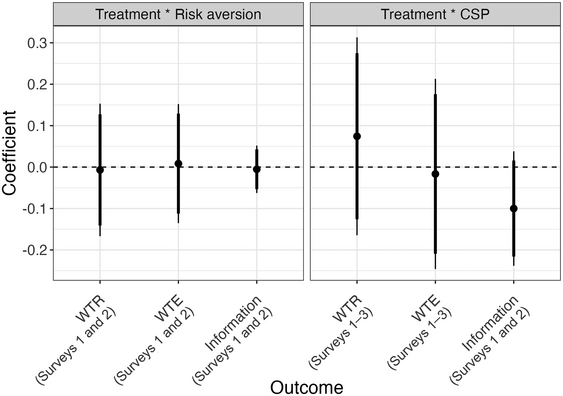

Turning to potential mechanisms for the hypothesized gender difference, Figure 2 shows the treatment's interaction with our pre‐treatment attitudinal measures. First, we do not find differential effects based on an individual's level of risk aversion. Thus, in contrast to H3, risk aversion, which in our sample tends to be slightly higher among women,Footnote 10 does not interact with the information treatment. Similarly, across all three outcomes, we find no evidence that preference for a cooperative style of politics moderates our treatment effect (in contrast to H4).Footnote 11

Figure 2. Treatment interaction with risk aversion index (pre‐treatment) and preference for a cooperative style of politics (pre‐treatment).

Note: OLS coefficients with 90 per cent (thick bars) and 95 per cent (thin bars) confidence intervals based on robust standard errors. WTR and WTE range from 1 (“very unlikely”) to 5 (“very likely”). Information is a binary outcome. Models using data from all three surveys include a dummy indicator for the third survey. (See Online Appendix Table E.4 for full model results.) The analysis is restricted to respondents with high political interest.

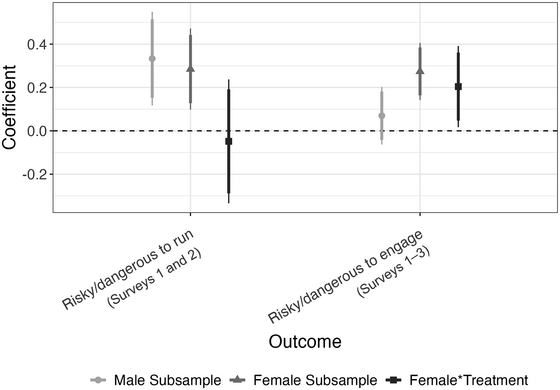

In Figure 3, we explore the effect of the treatment on the perception of the personal danger/risk associated with (1) political candidacy and with (2) political engagement on the local level. The treatment raises the perceived personal risk/danger of candidacy among both genders. There is also a positive treatment effect on the perceived risk/danger of political engagement in the female subsample. These findings are reassuring from a research‐design perspective since they suggest that our manipulation was strong enough to shape beliefs about the risk/danger of entering local politics – an outcome that should be most immediately affected by the information treatment. This risk perception, however, does not translate into lower willingness to enter the political arena among female respondents in our high political interest sample, which points to the existence of countervailing factors that make this group resilient to rising political violence.

Figure 3. Treatment effect on risk perception by gender.

Note: OLS coefficients with 90 per cent (thick bars) and 95 per cent (thin bars) confidence intervals based on robust standard errors. The scales of the outcome variables range from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 5 (“completely agree”). Within‐subgroup and interaction coefficients were estimated in separate models. Models with “Risky to engage” as the outcome include a dummy indicator for the third survey. (See Online Appendix Table E.5 for full model results.) The analysis is restricted to respondents with high political interest.

To address whether our null results are driven by familiarity with the facts in our treatment, we conduct an instrumental variables analysis in which we instrument the treatment with risk perception. The intuition for this exercise is that those for whom the treatment increased risk perception are arguably those who received new information about political violence. Thus, we treat this as an analysis of the effect of the information treatment among those for whom it plausibly provided new information. Similar to our main analysis, we do not find a significant interaction between the treatment and the gender of the respondent (see Online Appendix Figure E.7).

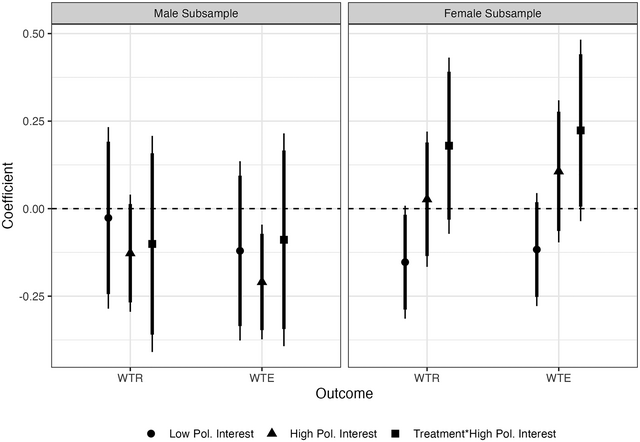

Finally, we also analyse treatment effects in a sample of respondents with low levels of political interest for two reasons: First, empirical evidence suggests that these respondents may differ in important traits such as risk aversion from politicians or politically interested populations (Magalhães & Pereira, Reference Magalhães and Pereira2024). Second, while these individuals have a low likelihood to become politically active, potential treatment effects among this sample may have long‐term pipeline effects if individuals are deterred from even considering to become active in politics. As Figure 4 shows, we find suggestive evidence of a negative treatment effect on political ambition among women with low political interest compared to those with high political interest. Moreover, the interaction between treatment and political interest is statistically significant at α = 0.1 for the WTE outcome. Men with varying levels of political interest, on the other hand, are not differentially affected by the treatment, given the lack of an interaction effect between political interest and the treatment.

Figure 4. Treatment effects by political interest and gender (Survey 3).

Note: OLS coefficients with 90 per cent (thick bars) and 95 per cent (thin bars) confidence intervals based on robust standard errors. WTR and WTE range from 1 (“very unlikely”) to 5 (“very likely”). High Pol. Interest is a dummy that equals one if respondents indicated a level of political interest of five or higher on a seven‐point scale, otherwise the variable is coded as zero (i.e., Low Pol. Interest = one to four on the seven‐point scale). Within‐subgroup and interaction effects were estimated in separate models. (See Online Appendix F for the question wordings).

Conclusion

Does political violence undermine the descriptive representation and political ambition of women? We study this question in the context of German local politics. Overall, indirect exposure to crimes against politicians does not decrease the share of women on party lists for municipal elections. Moreover, informing female respondents with high political interest – a section of the population that arguably has a higher likelihood to consider local candidacy and political engagement – about attacks against politicians does not decrease their political ambition. In contrast, there is suggestive evidence that exposure to political violence might decrease the gender gap in politics by having a stronger deterrent effect on politically interested men.

Our results point to resilience among women in the face of rising hostility against politicians. The underlying mechanisms are outside of the scope of this study but remain a promising avenue for further research. One potential explanation builds on recent evidence suggesting that the subset of female candidates and elected officials differ from the broader population in ways that challenge traditional notions of gendered political behaviour (Magalhães & Pereira, Reference Magalhães and Pereira2024; Yan & Bernhard, Reference Yan and Bernhard2024). For example, women who consider activity in politics – a male‐dominated environment – may have already developed a “thick skin” and mental fortitude, allowing them to overcome perceived personal risks or dangers associated with political engagement. In support of this proposition, in our third survey – where we also interviewed respondents with low political interest – we found a negative treatment effect among unlikely female candidates.

It may even be that exposure to political violence motivates potential female candidates to become active in politics to change it in a more cooperative and constructive direction.Footnote 12 Relatedly, men who consider entering politics might be more instrumentally motivated than women (Pate & Fox, Reference Pate and Fox2018, p. 177), which may explain why they are more likely to withdraw after exposure to our information treatment. Overall, we conclude that indirect exposure to political violence does not exacerbate the gender gap in political ambition or descriptive representation.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments, we thank Sofia Ammassari, Rafaela Dancygier, Hanno Hilbig, Jonathan Homola, Anne‐Kathrin Kreft, Patrick Kuhn, Tali Mendelberg, Simon Otjes, Tine Paulsen, Neeraj Prasad, Sascha Riaz and Antonio Valentim. We also thank conference participants at APSA 2021, DVPW 2021, EPSA 2022, MPSA 2022, APSA 2024 and seminar participants at the 2021 Amsterdam Workshop on Elections and Violence, the EUI and Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. For generous financial support, we thank Rafaela Dancygier and Princeton Research in Experimental Social Science (PRESS). The survey experiment was pre‐registered with EGAP (survey rounds one and two: https://osf.io/hxuz7; survey round three: https://osf.io/ab6sq) and was approved by Princeton University's IRB (protocol # 13775) and the WZB Research Ethics Review Board (2022/10/179). The Open Access publication was funded by the WZB Berlin Social Science Center via the DEAL‐Consortium.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://github.com/mariusgruenewald/pol_viol/tree/main/replication_package.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix