Introduction

The deaths of Adam Toledo, Andrés Guardado, Sean Monterrosa, and Mario Gonzalez Arenales at the hands of law enforcement have increasingly drawn national attention to the experiences of Hispanic populations with police violenceFootnote 1 . While much of the public discourse on police brutality has centered on the Black community, these cases reveal that Hispanics also face disproportionate use of force and fatal encounters with law enforcement (Chavez Reference Chavez2021). Widespread media coverage of such tragedies has exposed stark disparities in the criminal justice system and contributed to polarized attitudes toward law enforcement. As protests against police violence intensified, so did calls to “defund” and restructure police departments, prompting legislative efforts to enhance accountability and transparency. In response, other segments of American society gathered in support of law enforcement, advocating for increased funding to maintain public safety (Drakulich and Denver Reference Drakulich and Denver2022). This divide is deeply embedded in political discourse, fueling contentious public debates and heightened scrutiny of police practices that are ingrained in broader societal issues of race, individual worldview, and the role of police in America.

This study investigates whether the authoritarian worldview, defined as a psychological orientation favoring order, conformity, and authority (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1981; Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Hetherington and Suhay Reference Hetherington and Suhay2011; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Perry, Sibley, and Duckitt Reference Perry, Sibley and Duckitt2013), predicts support for law enforcement and whether ethnicity moderates this relationship. While authoritarianism has been consistently linked to punitive policies and strong police support, few studies examine how it shapes perceptions of law enforcement within Hispanic communities. This study addresses that gap by exploring whether authoritarianism predicts favorable views of police among Hispanic individuals and whether this relationship is shaped by identity-based factors.

The Hispanic identity encompasses a diverse range of national origins, racial-ethnic identities, and socio-political beliefs that shape their views of law enforcement. These differences are important, as many report experiences of racial profiling, over-policing, and immigration enforcement, all of which may foster distrust of police (Hurwitz, Peffley, and Mondak Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015; Noe-Bustamante, Mora, and Lopez Reference Noe-Bustamante, Gonzalez-Barrera, Edwards, Mora and Lopez2021). Yet, some research finds that segments of the Hispanic population express favorable views of law enforcement, challenging the assumption that historically marginalized groups uniformly hold negative perceptions of the police (Correia Reference Correia2010; Lim and Bontcheva-Loyago Reference Lim and Bontcheva-Loyaga2024). These contrasting experiences complicate how authoritarian values emerge within Hispanic populations. This tension is especially salient in today’s political climate, where heightened deportation efforts by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) have renewed fear and distrust in many Hispanic communities.

We build on existing research on authoritarianism and its key components of perceived threat, social conformity, identity, and opposition to challenges to authority. Together, these components reinforce a climate of fear with a desire for social order through authority, in this case, law enforcement, and opposition to challenges to that authority. We hypothesize that authoritarian individuals are generally supportive of the police, but for Hispanic authoritarians, factors such as acculturation and racial-ethnic identity may moderate how authoritarian worldviews shape attitudes toward law enforcement. To explore this relationship, we analyze data from the 2020 American National Election Study (ANES), which includes comprehensive survey items on police favorability and sample sizes for both non-Hispanic white and Hispanic respondents.

Public Perceptions of Police and Authoritarianism

Scholars traditionally conceptualize authoritarianism as a combination of three personality traits: submission to authority, outgroup aggression, and social conformity (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1981, Reference Altemeyer1996; Hetherington and Suhay Reference Hetherington and Suhay2011). More recent studies emphasize the trait of social conformity (Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009), defined as “a desire for an orderly and structured world” (Hurwitz and Peffley Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1992, 400). This preference for order is contingent on a stronger sense of social threat, which authoritarians experience more acutely than non-authoritarians, that generates support for policies, institutions, and government actions that prioritize social stability and minimize disorder (Altemeyer Reference Altemeyer1996; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Kehrberg Reference Kehrberg2017; Lipset Reference Lipset1959). Within this framework, the concept of the “thin blue line” positions law enforcement as agents of social conformity, preventing society from descending into “a dangerous and chaotic world” (Perry, Sibley and Duckitt Reference Perry, Sibley and Duckitt2013). Those with authoritarian worldviews tend to support a strong police presence, viewing officers as enforcers of social norms and defenders of the dominant social group (Larsen Reference Larsen1968; Perry et al. Reference Perry, Sibley and Duckitt2013). In this sense, we would predict that more authoritarian non-Hispanic whites would support law enforcement as agents of social control, preserving the existing social and political hierarchies that favor their racial group.

Although authoritarianism generally predicts support for law enforcement, public perceptions are also shaped by race and ethnicity. Research has shown that even when controlling for characteristics such as socioeconomic status, political ideology, and direct or indirect experiences with law enforcement, trust in police differs across racial and ethnic groups (Brown and Benedict Reference Brown and Benedict2002; Epp, Maynard-Moody and Naider-Markel Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014; Hurwitz et al. Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015; Thomas and Hyman Reference Thomas and Hyman1977; Tyler Reference Tyler2005). These differences often stem from collective experiences of negative interactions with police, discriminatory treatment, and overrepresentation within the criminal justice system (Brown and Benedict Reference Brown and Benedict2002; Hurwitz et al. Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015; Lopez and Livingston Reference Lopez, Livingston and Center2009; Menjivar and Bejarano Reference Menjivar and Bejarano2004; Noe-Bustamante et al Reference Noe-Bustamante, Gonzalez-Barrera, Edwards, Mora and Lopez2021). When Hispanic individuals encounter stop-and-frisk practices, immigration raids, or other hostile policing strategies, it contributes to the authoritarian notion that police serve as representatives of an institution that prioritizes social order, conformity, and submission to authority.

Research demonstrates that Hispanics, on average, exhibit higher levels of authoritarianism than non-Hispanic whites (Nation and LeUnes Reference Nation and LeUnes1983; Ramirez Reference Ramirez III1967; Henry Reference Henry2011; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Pérez and Hetherington Reference Pérez and Hetherington2014). While higher authoritarianism may imply stronger support for law enforcement, these negative encounters complicate that assumption (Engelhardt, Feldman and Hetherington Reference Engelhardt, Feldman and Hetherington2023). Historically, law enforcement has played a central role in maintaining an American social order that has subordinated communities of color through systems of slavery, Jim Crow segregation, (Alexander Reference Alexander2012), and racially biased policing, culminating in movements such as Black Lives Matter. Dawson (Reference Dawson1994) contends that the pattern of systemic and structural racism fosters a strong sense of race-linked fate: the belief that an individual’s fate is intertwined with the fate of their racial group identity (e.g., Hurwitz et al. Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015; McClain et al Reference McClain, Johnson Carew, Walton and Watts2009; Russell and Garand Reference Russell and Garand2023). These negative interactions with law enforcement decrease trust and reposition the police as an institution of enforcers of social control rather than protectors of public safety. High-profile incidents of police brutality against Hispanics can cultivate a sense of race-linked fate (Telles and Ortiz Reference Telles and Ortiz2008) that may moderate the influence of authoritarian values, weakening support for police even among those with strong preferences for order and authority. Among marginalized communities, authoritarianism may function differently than it does within dominant groups. Rather than reflecting an ideological preference for social conformity, it may emerge as a psychological defense mechanism to cope with marginalization and group-based threat (Henry Reference Henry2011). Thus, authoritarianism may arise as a psychosocial response to race-related stress prompted by unjust interactions, including those with the police. When law enforcement is perceived as perpetuating racial injustice through raids, arrests, and deportations, authoritarian Hispanics may still value social order but reject law enforcement as a means of achieving it. From this perspective, Hispanic Americans, even those with authoritarian worldviews, are unlikely to view law enforcement as agents of social conformity who protect their interests. Rather, they may perceive the police as instruments of oppression that are tasked with preserving social order and enforcing norms that perpetuate harm against their ethnic group.

Alternatively, there is reason to expect that a positive relationship between authoritarianism and support for law enforcement will appear, mirroring patterns observed among non-Hispanic Whites. Acculturation, defined as the process by which immigrants and their descendants adopt the dominant culture norms and values, leads to significant shifts in both personal and socio-political identities over generations (Newton Reference Newton2000). As individuals become more acculturated, their worldviews often shift. Research shows that first-generation immigrants often hold significantly different beliefs and cultural orientations than the later, more acculturated generations (Abrajano and Alvarez Reference Abrajano and Alvarez2011; Branton Reference Branton2007; de la Garza et al. Reference De la Garza, Garcia, Garcia and Falcon1993; Kehrberg et al. Reference Kehrberg, Cepek, Trubo and Yonts2025; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Polinard and Wrinkle1984; Rouse et al Reference Rouse, Wilkinson and Garand2010; Voss et al. Reference Voss, Kehrberg, Butz, Freeman, Hansen and Leal2013). Later-generation Hispanics are more likely to assimilate into dominant cultural frameworks and less likely to maintain strong ethnic identities (Branton Reference Branton2007; Abrajano and Alvarez Reference Abrajano and Alvarez2011). For some, this results in greater alignment with pro-police authoritarian views. By contrast, first-generation immigrants may view American law enforcement more positively in comparison to repressive policing regimes in their countries of origin. Menjivar and Bejarano (Reference Menjivar and Bejarano2004) describe this as a “bifocal lens,” reinforcing favorable views of American law enforcement within early generations (Correia Reference Correia2010; Lim and Bontcheva-Loyago Reference Lim and Bontcheva-Loyaga2024). Through this perspective, American police are perceived as more professional, honest, fair, and legitimate (Correia, Reference Correia2010; Lim and Bontcheva-Loyago Reference Lim and Bontcheva-Loyaga2024).

Racial-ethnic self-identification also convolutes the relationship between authoritarianism and attitudes toward law enforcement. The panethnic nature of the Hispanic identity encompasses diverse racial and cultural backgrounds that may undermine race-linked fate. Research demonstrates that Hispanics vary in how they classify their racial-ethnic identity, with a growing segment that neither identifies as Hispanic, nor views their fate from the experiences of earlier generations (Filindra and Kolbe Reference Filindra and Kolbe2022; Lopez et al. Reference Lopez, Gonzalez-Barrera and Lopez2017). Prior scholarship finds that the strength of panethnic identity declines across generations, with third generation and later individuals more exposed to the dominant cultural identity and more fully integrated into American society (Abrajano and Alvarez Reference Abrajano and Alvarez2011; Branton, Reference Branton2007; Callister, Galbraith and Galbraith Reference Callister, Galbraith and Galbraith2019; Hood et al. Reference Hood, Morris and Shirkey1997; Newton Reference Newton2000; Rouse et al. Reference Rouse, Wilkinson and Garand2010). As acculturation progresses and racial-ethnic self-identification diversifies, some individuals may feel less psychologically connected to a panethnic group identity (Filindra and Kolbe, Reference Filindra and Kolbe2022; Newton, Reference Newton2000). Flindra and Kolbe (Reference Filindra and Kolbe2022) and Cuevas-Molina (Reference Cuevas-Molina2023) find that Hispanics who identify as Republican and hold conservative political views are more likely to self-identify as white and express white identity salience. Scholars contend that this shift may serve as a psychological response to avoid stigmatization and structural disadvantage embedded in American social structures (Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2013; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). This weakening of group-based identity can diminish the role of linked fate in shaping law enforcement attitudes (Russell and Garand Reference Russell and Garand2023). Thus, Hispanics who identify as white and align their racial identity with the dominant group may be more inclined to adopt authoritarian worldviews that prompts greater support for law enforcement, further complicating the relationship between ethnicity and authoritarianism.

In summary, the relationship between authoritarianism and attitudes toward law enforcement among Hispanics is multifaceted. While authoritarianism often predicts pro-police attitudes, this relationship is shaped by processes such as acculturation, racial-ethnic self-identification, and political orientation that further complicate this relationship. This study seeks to address a gap in the literature by examining how authoritarianism interacts with identity-based factors to shape perceptions of law enforcement among Hispanic respondents.

Data and Measures

This study draws on data from the 2020 ANES, a nationally representative time-series survey designed to measure public opinion and voting behavior in U.S. presidential elections. The ANES was conducted in two waves: pre- and post-election.Footnote 2 Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, most respondents completed the survey online, while smaller subsets were completed by telephone and video conferencing, yielding a representative cross-sectional sample of 8,280 respondents.Footnote 3

The ANES offers two key advantages for this analysis. First, it includes items that measure authoritarianism, immigration history, and attitudes toward law enforcement. Second, its sample sizes for both non-Hispanic white and Hispanic respondents enable intergroup comparisons. After excluding participants with missing data on key independent variables, the sample sizes ranged from 4,244 to 4,379 for non-Hispanic whites and 440 to 471 for Hispanics.Footnote 4

Attitudes Toward Law Enforcement

We combined four items into a single index to measure overall attitudes toward law enforcement. The first item uses a feeling thermometer to assess general opinions of police.Footnote 5 The second asks, “What is the best way to deal with the problem of urban unrest and rioting?” with response options emphasizing either addressing systemic racism and police violence or prioritizing law and order.Footnote 6 The third item assesses perceptions of fairness in how police treat white and Blacks individuals.Footnote 7 The fourth item measures attitudes toward police use of force.Footnote 8

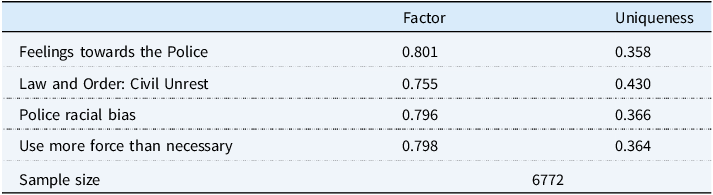

The combined four-item measure produced a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 overall, indicating acceptable internal consistency. The reliability was similar across groups, 0.76 for non-Hispanic whites and 0.72 for Hispanics. As shown in Table 1, a principal component factor analysis of these items yielded a unidimensional scale with an eigenvalue greater than 1.0. This analysis supports combining the items into a single index reflecting a reliable measure for overall attitudes toward law enforcement, ranging from negative to positive.

Table 1. Factor analysis creating a law enforcement attitudinal measure

Note: Reports are results of principal components factor analysis, the factor we use had an eigenvalue of 2.48.

Authoritarianism

Although authoritarianism has long been used to explain ideological values, the measurement of the construct has evolved over time. Earlier measures, such as the F-Scale (Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson and Sanford1950) and Altemeyer’s (Reference Altemeyer1981) Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale, have largely been replaced by the Child-Rearing Scale (CRS) (Feldman and Stenner Reference Feldman and Stenner1997; Feldman Reference Feldman2003). Scholars argue that the CRS is a superior measure because it excludes questions with political content (Engelhardt et al. Reference Engelhardt, Feldman and Hetherington2023). As Feldman (Reference Feldman2003) notes, prior measures such as the RWA index included questions about prejudice, intolerance, and conservatism, which made predicting prejudice and the like from authoritarianism a tautological exercise.

The CRS consists of four questions asking respondents to identify which qualities they believe are more important in children (e.g., Hetherington and Suhay Reference Hetherington and Suhay2011; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Kehrberg Reference Kehrberg2020; Stenner Reference Stenner2005). The question stem reads: “Although there are a number of qualities that people feel that children should have, every person thinks that some are more important than others. I am going to read you pairs of desirable qualities. Please tell me which one you think is more important for a child to have.” Respondents select between four value pairs: (1) “being independent” or “respectful of elders”; (2) “self-reliance” or “obedience”; (3) “curiosity” or “good manners”; and (4) “being considerate” or “being well behaved.” The authoritarian responses are “respect for elders,” “obedience,” “good manners,” and “being well-behaved,” reflecting values of order, conformity, and obedience to authority. The design minimizes social desirability bias and avoids overlap with political beliefs (Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Hetherington and Suhay Reference Hetherington and Suhay2011; Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Stenner Reference Stenner2005). Each response is coded as 0 for the non-authoritarian value, 1 for the authoritarian value, and 0.5 if the respondent selects both.Footnote 9 The scores from the four items are summed and rescaled to range from 0 (endorsing non-authoritarian values on all four items) to 1 (endorsing authoritarian values on all items signifies high authoritarianism), creating a nine-point scale. The combined scale demonstrates acceptable internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.66.

Acculturation and White Identity Salience

To further examine the factors shaping attitudes toward law enforcement, we include two additional variables: immigrant generational status, as a proxy for acculturation, and feelings toward non-Hispanic whites, measuring white identity salience. The ANES provides data on family immigration history, from which we constructed a four-category generational variable: (1) first-generation, respondents who are immigrants; (2) second-generation, respondents born in the United States to at least one foreign-born parent; (3) third-generation, respondents and their parents were born in the United States, but at least one foreign-born grandparent; and (4) fourth-generation, respondents, their parents, and all grandparents born in the United States.

Although widely used as a proxy for acculturation (e.g., Branton Reference Branton2007; de la Garza et al. Reference De la Garza, Garcia, Garcia and Falcon1993; Kehrberg et al. Reference Kehrberg, Cepek, Trubo and Yonts2025; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Polinard and Wrinkle1984; Rouse et al. Reference Rouse, Wilkinson and Garand2010), generational status is not a direct measure of racial and ethnic identity, as it may evolve over time (see Alba and Islam Reference Alba and Islam2009) and across generations (Portes and Rumbaut Reference Portes and Rumbaut2001). Nonetheless, it provides useful insight into how acculturation processes may shape variation in attitudes toward law enforcement.

Another pathway is to consider how racial-ethnic identification and intergroup attitudes influence support for law enforcement. Hispanics who identify as white and express strong white identity salience may be more likely to align with dominant white cultural norms (Cuevas-Molina Reference Cuevas-Molina2023; Filindra and Kolbe Reference Filindra and Kolbe2022). For these individuals, law enforcement may symbolize the protection of the social order they perceive themselves as part of. In this context, their authoritarianism reflects alignment with majority-group norms, rather than a defensive response to discrimination. Moreover, Hispanics who self-identify as white and experience white identity salience may not fit Pérez and Hetherington’s (Reference Pérez and Hetherington2004) concern that the child-rearing measure misrepresents authoritarianism values across racial and ethnic populations. Instead, their authoritarianism may operate similarly to that of non-Hispanic whites.

Unfortunately, the 2020 ANES dataset limits our ability to directly compare Hispanics who self-identify as white with those who do not in terms of authoritarianism and attitudes toward policing. However, we include a proxy for white identity salience using the ANES item “white feeling thermometer,” which asks respondents how coldly or warmly they feel toward non-Hispanic whites. Higher scores reflect warmer, more positive feelings, while lower scores indicate colder, less favorable attitudes. Both the generational measure of acculturation and the feeling thermometer measure of identity salience are rescaled to range from 0 to 1.

Control Variables

We include several control variables to account for factors known to influence attitudes toward law enforcement. These include Hispanic identity, socioeconomic status, and demographic characteristics. Prior research consistently shows that both indirect and direct contact with law enforcement is associated with more negative views of the police (e.g., Brown and Benedict Reference Brown and Benedict2002; Epp, Maynard-Moody and Naider-Markel Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014; Thomas and Hyman Reference Thomas and Hyman1977). Not all encounters with the police are negative experiences, but being stopped and/or questioned by the police can be a negative experience, especially for people of color who are more likely to be searched (Epp et al. Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014). To account for these types of police encounters, we include a variable indicating whether the respondent or a family member has been “stopped or questioned” by police within the past twelve months. This variable is recoded as 0 (not stopped) and 1 (stopped).

The Hispanic identity is not monolithic. Internal variation is driven by acculturation, immigration history, and racial and ethnic identity that influence social and political attitudes (Hood et al. Reference Hood, Morris and Shirkey1997; Newton Reference Newton2000; Branton Reference Branton2007; Rouse et al. Reference Rouse, Wilkinson and Garand2010; Abrajano and Alvarez Reference Abrajano and Alvarez2011; Callister et al. Reference Callister, Galbraith and Galbraith2019; Kehrberg et al. Reference Kehrberg, Cepek, Trubo and Yonts2025). As such, added control variables of Hispanic identity, partisanship, and political ideology are included. Hispanic identity is measured with an ANES item that asks respondents whether they are of Hispanic, Spanish, or Latino origin, coded as No (0) and Yes (1). Partisanship is measured on a seven-point scale ranging from strong Democrat (0) to strong Republican (1), with Independents coded at the mid-point (.5). Respondents who selected “refused” or “don’t know” were excluded from the analysis. Finally, political ideology is assessed on a seven-point scale; respondents were asked to place themselves on an ideological spectrum ranging from extremely liberal (lowest value) to extremely conservative (highest value).

Socio-economic status is measured using education and household income. Education is coded on a four-point scale: (1) less than a high school degree, (2) high school degree, (3) some college or an associate’s degree, (4) bachelor’s degree or higher. Household income is measured on a 21-category scale ranging from less than $9,999 (lowest) to $250,000 or more annually (highest). Demographic controls include gender (1 = female, 0 = male) and age.Footnote 10 All independent and control variables, except age, are rescaled to range between 0 and 1.

Data Analysis

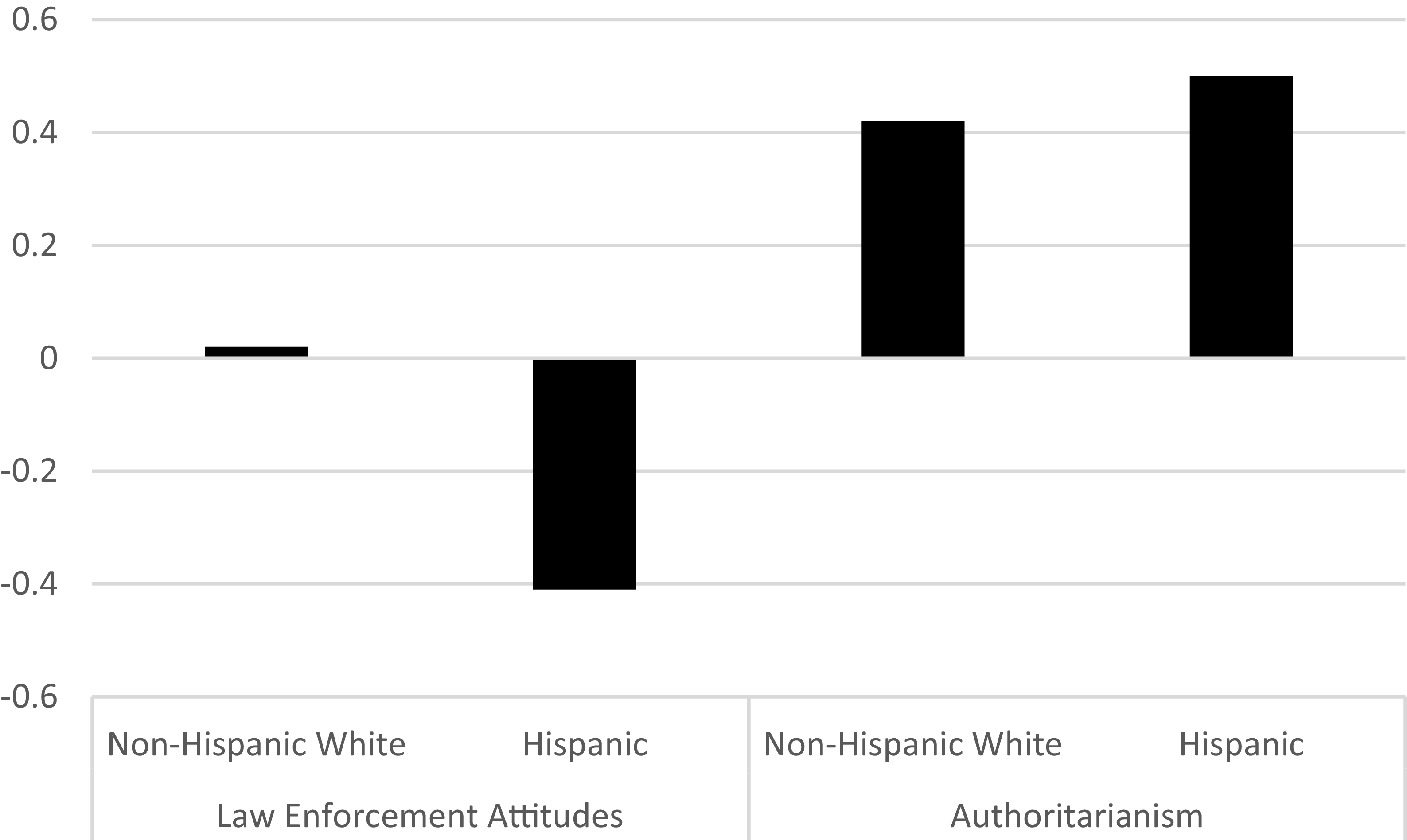

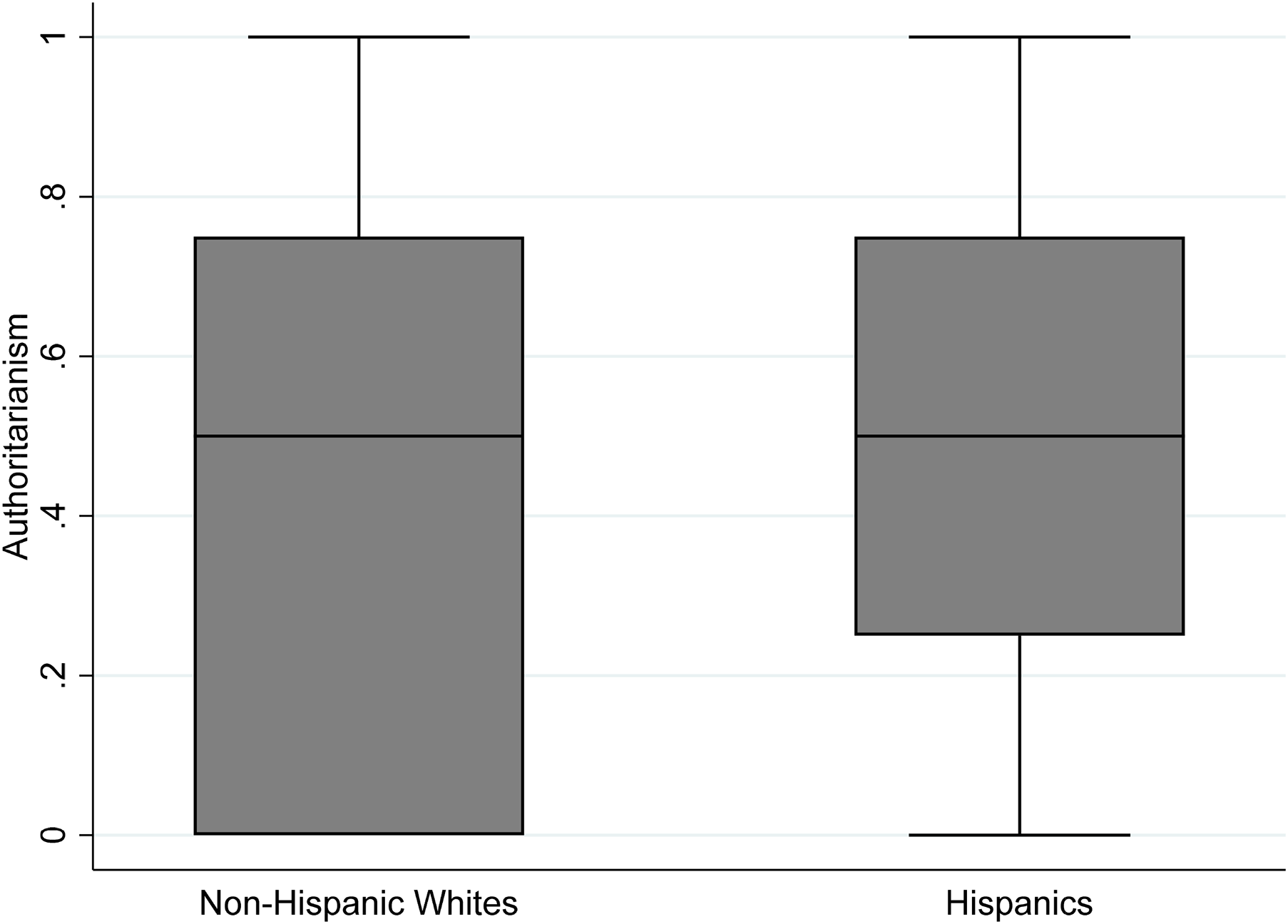

We begin the data analysis by establishing baseline attitudes toward law enforcement and levels of authoritarianism for non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics. As illustrated in Figure 1, non-Hispanic whites express slightly positive attitudes toward the police (m = 0.02), whereas Hispanics report more negative views (m = −0.41). A t-test confirms that this difference is statistically significant (t = 8.67, p < .001). In terms of authoritarianism, Hispanics exhibit marginally higher levels (m = 0.50) compared to non-Hispanic whites (m = 0.42), with the difference again reaching statistical significance (t = −4.87, p < .001).

Figure 1. Average level of law enforcement attitudes and authoritarianism by ethnic groups. Values plotted are the mean value for each group. Higher values indicate more favorable attitudes towards police and higher levels of authoritarianism.

Authoritarianism and Support for Law Enforcement

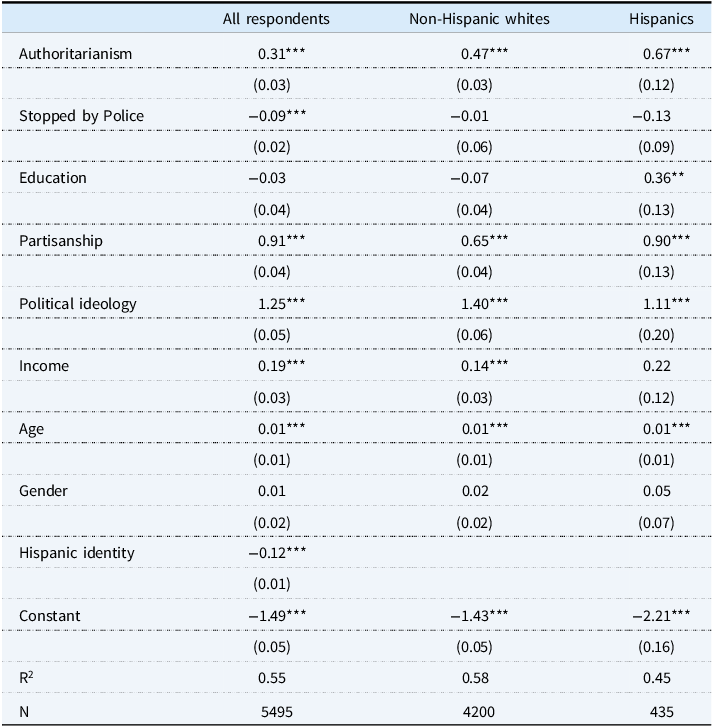

Next, we examine whether authoritarianism predicts attitudes toward law enforcement using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models, controlling for socio-political and demographic factors. Analyses were conducted for the combined sample, non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics. The first column of Table 2 presents the effects of the combined sample to explore the overall baseline relationship. As hypothesized, authoritarianism emerges as a strong positive predictor of favorable attitudes toward law enforcement (b = 0.31, p < .001). These findings support longstanding perspectives that authoritarians view the police as essential agents of social order, fulfilling authoritarians’ needs for creating structure in what they perceive to be a dangerous world. Hispanic identity is negatively associated with support for law enforcement (b = −0.12, p < .001). This suggests that, on average, Hispanics express less favorable views of law enforcement than non-Hispanic whites. This difference likely reflects racialized experiences with policing, which diminish support for police institutions (e.g., Brown and Benedict Reference Brown and Benedict2002; Epp, Maynard-Moody and Naider-Markel Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014; Thomas and Hyman Reference Thomas and Hyman1977).

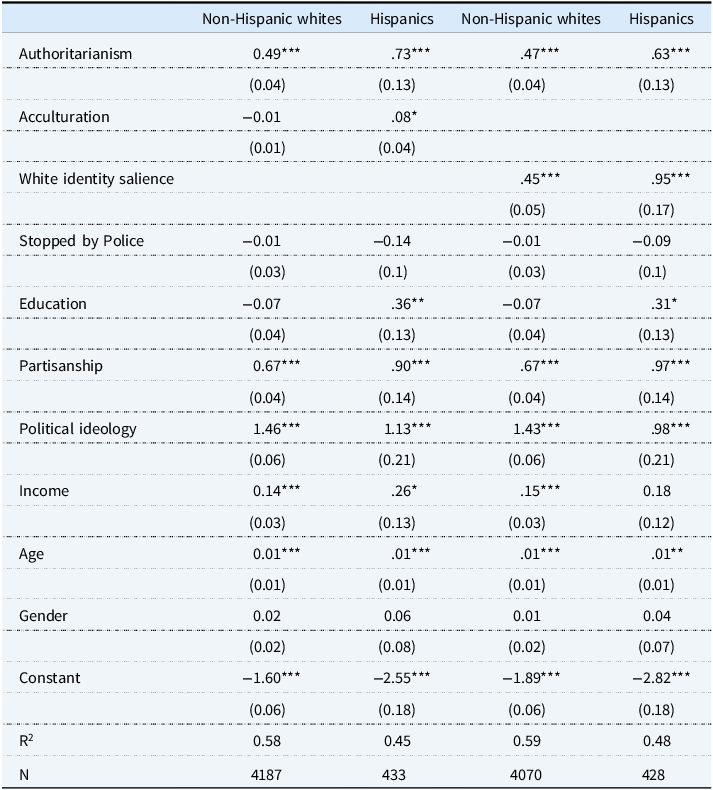

Table 2. Relationship between authoritarianism and law enforcement attitudes

Note: *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001. All models use OLS Regression to generate coefficient estimates.

Partisanship and political ideology also emerge as strong predictors of pro-law enforcement attitudes. This finding supports prior arguments that conservatives and Republicans, like authoritarians, prioritize order and hierarchy and exhibit greater support for law enforcement. This finding coincides with prior scholarship demonstrating that the Republican Party’s law-and-order rhetoric has shaped public opinion along partisan lines (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and James1989), attracting individuals with authoritarian dispositions and strengthening the connection between conservative political identity and pro-police attitudes (Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009). Regarding the demographic controls, education and gender do not exhibit statistically significant effects. However, both income and age are positively correlated with support for law enforcement. This indicates that older and higher-income individuals perceive the police more favorably than younger and lower-income individuals. This pattern highlights the role of economic and social privilege in shaping perceptions of the police as protectors of societal order.

Racial-Ethnic Group Comparisons

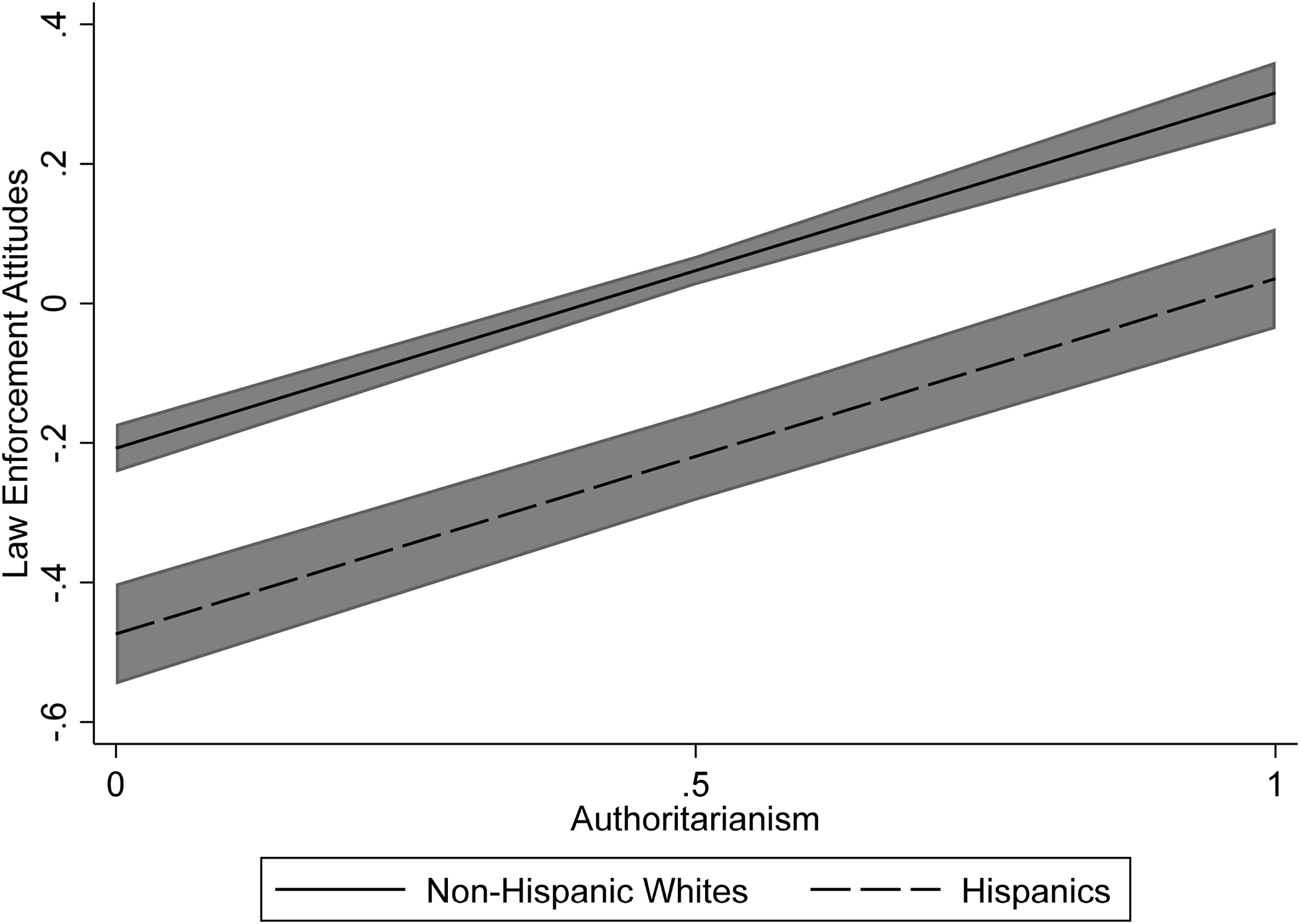

To assess whether the relationship between authoritarianism and attitudes toward law enforcement differs by ethnicity, we estimated separate models for non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics (Table 2, columns 2 and 3). For non-Hispanic whites, authoritarianism is positively and significantly associated with favorable law enforcement attitudes (b = 0.47, p < .001). Among Hispanics, authoritarianism also displays a positive and significant effect, with an even larger coefficient (b = 0.67, p < .001). These findings indicate that authoritarianism is a strong predictor of law enforcement attitudes in both groups, although Hispanics report lower baseline support. Figure 2 illustrates these results, showing positive marginal effects of authoritarianism on law enforcement attitudes for both groups. The positive slopes demonstrate that individuals with higher authoritarianism are more likely to express positive attitudes toward the police.

Figure 2. Graphing the marginal effects of authoritarianism on attitudes towards law enforcement by ethnic groups. Higher values indicate more positive attitudes towards law enforcement.

Most control variables display similar effects across groups. However, key differences arise in the effects of education and income. Income is positively associated with pro-law enforcement attitudes for both groups, but only reaches significance for non-Hispanic whites, likely reflecting sample size differences. Education, in contrast, is positively and significantly associated with law enforcement support for Hispanics (b = 0.36, p < .01). This implies that for some Hispanic individuals, higher educational attainment may not only be linked to greater endorsement of police, but also integration into mainstream, pro-institutional worldviews.

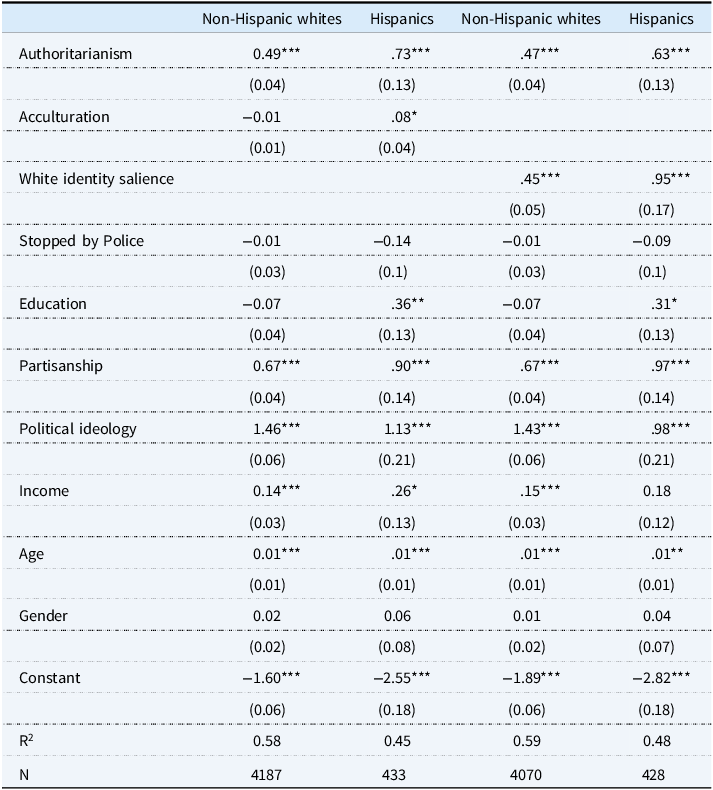

The Role of White Identity Salience and Acculturation

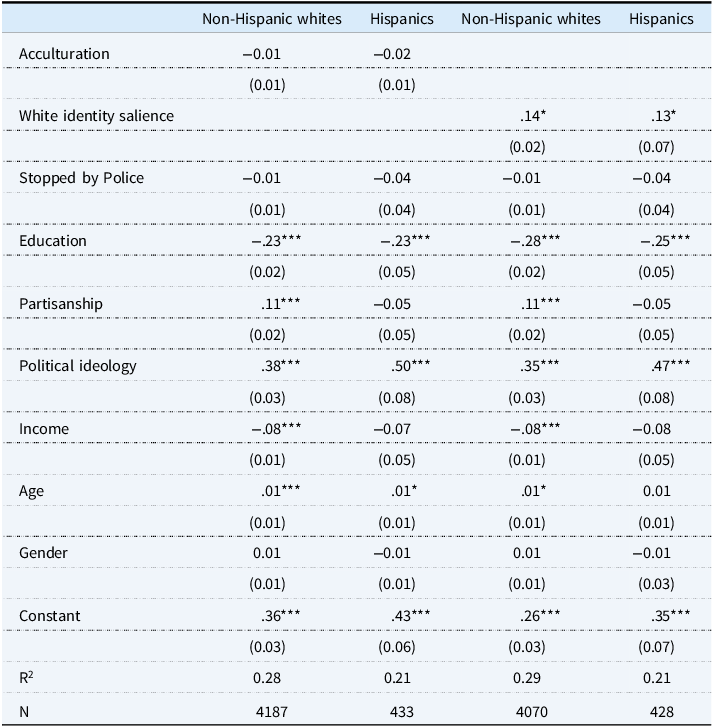

In Table 3, we analyze how social and cultural factors shape attitudes toward law enforcement by estimating separate OLS regression models for non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics to assess potential group differences. These models incorporate measures of acculturation and white identity salience. Authoritarianism remains a strong and significant predictor across all models. Among non-Hispanic whites, the relationship is stable (b = 0.49, p < .001; b = 0.47, p < .001), whereas for Hispanics, the effect is more substantial (b = 0.73, p < .001; b = 0.63, p < .001). These results reaffirm that authoritarianism is a consistent predictor of support for law enforcement across racial and ethnic groups, exerting a more pronounced influence on Hispanic respondents.

Table 3. Differences in law enforcement attitudes including acculturation and white identity salience

Note: *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001. All models use OLS Regression to generate coefficient estimates.

Shifting the focus to the white identity salience and acculturation variables, white identity salience was strongly associated with positive law enforcement attitudes for Hispanics (b = 0.95, p < .001) and non-Hispanic whites (b = 0.45, p < .001). These results highlight the importance of racial identity salience in explaining political attitudes for ethnic groups. Acculturation also exerts a meaningful influence on law enforcement attitudes for Hispanics (b = 0.08, p < .05), but not for non-Hispanic whites (b = −0.01, p > .05). Later-generation Hispanics, who are more accultured and further removed from the immigrant experience, tend to express more favorable views of law enforcement. This pattern is evident in the average attitudes toward police across Hispanic immigrant generations. First through third-generation Hispanics, on average, hold negative attitudes toward law enforcement with mean values ranging between −0.43 (second generation) and −0.29 (third generation). In comparison, fourth-generation Hispanics have slightly positive attitudes (m = 0.05), closely resembling the overall mean for non-Hispanic whites (m = 0.02).

Finally, education continues to show a positive association with attitudes toward police among Hispanics (b = 0.36 and 0.31, p < .01 and p < .05, respectively), while remaining non-significant for non-Hispanic whites. Remarkably, experiences of being stopped by police do not reach statistical significance in either group, revealing that political identity, authoritarianism, and white identity salience are more influential predictors of law enforcement attitudes than being stopped by the police.

We shift the focus of our analysis to examine the predictors of authoritarianism itself, starting with the distribution of authoritarianism scores using boxplots in Figure 3. Among Hispanics, authoritarianism scores cluster more tightly around the mean, as indicated by the first quartile. In contrast, non-Hispanic whites show a broader distribution, with a larger proportion reporting lower levels of authoritarianism. However, the third and fourth quartiles show comparable distributions across both groups. These patterns raise important questions about whether authoritarianism functions similarly across racial-ethnic groups.

Figure 3. Distribution of authoritarianism by ethnic group.

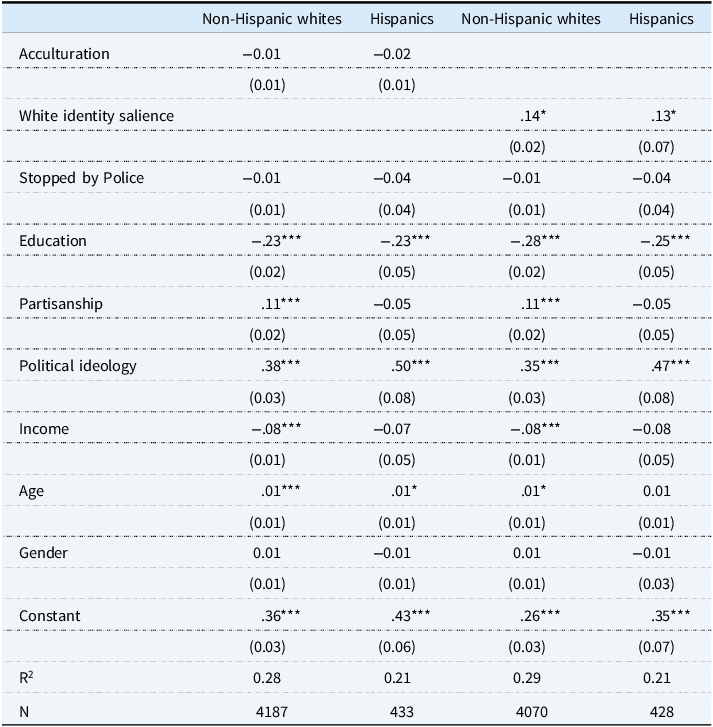

In Table 4, we present OLS regression results predicting authoritarianism itself as the dependent variable with separate statistical models for non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and based on key independent variables. This approach allows us to assess whether the social and political foundations of authoritarianism differ between non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics. Starting with the control variables, party identification predicts authoritarianism only for non-Hispanic whites (b = 0.11, p < .001 in both models), suggesting that partisan attachments are a stronger driver of authoritarianism in this group, with Republicans expressing more authoritarian attitudes on average. Income is negatively associated with authoritarianism for non-Hispanic whites (b = −0.08, p < .001), but this relationship does not appear among Hispanics. Age shows a small but consistent positive association with authoritarianism across both groups. Experiences of being stopped by police and gender are not significantly associated with authoritarianism in any model.

Table 4. Estimating differences in authoritarianism

Note: *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001. All models use OLS Regression to generate coefficient estimates.

White identity salience is a consistent predictor of authoritarianism for both groups. Among non-Hispanic whites, it shows a modest positive effect (b = 0.14, p < .05), a pattern similarly observed for Hispanics (b = 0.13, p < .05). In contrast, acculturation does not significantly predict authoritarianism for either group with regression coefficients near zero for both non-Hispanic whites (b = −0.01, p > .05) and Hispanics (b = −0.02, p > .05). These findings indicate that individual assimilation into a white identity is more closely linked to authoritarian attitudes while generational differences in acculturation do not significantly account for variation in authoritarianism.

Taken together, these analyses demonstrate that authoritarianism, political identity, and white identity salience are key predictors of support for law enforcement across racial and ethnic groups. However, the social and political foundations of authoritarian worldviews differ slightly. For non-Hispanic whites, partisanship and white identity salience play a more prominent role in shaping authoritarianism. For Hispanics, acculturation and white identity salience exert greater influence on support for law enforcement, suggesting that cultural assimilation processes may shape political attitudes in distinct ways.

Discussion

The findings for Hispanics challenge the notion that authoritarianism emerges primarily as a defensive psychological response to stigmatization and discrimination (Henry Reference Henry2011). If race-linked fate and shared negative experiences with law enforcement shaped authoritarian orientations, more authoritarian Hispanics would likely express critical views of police. Instead, our analysis demonstrates the opposite pattern; more authoritarian Hispanics are more likely to hold favorable views of the police. This supports the interpretation of authoritarianism as a stable worldview that prioritizes social order and conformity, rather than a defensive psychological response to marginalization. The critical role of racial identity salience emerges for both non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics showing that an affinity for the dominant racial group is linked to greater endorsement of authoritarian values emphasizing social order and deference to authority.

The study advances the literature by demonstrating that authoritarianism functions as a stable psychological orientation across racial and ethnic groups, not solely as a response to group-based threats. These findings undermine assertions that experiences of discrimination fundamentally transform how authoritarianism influences attitudes toward state institutions. Future research should explore why Hispanic communities, despite facing frequent discrimination and disproportionate police contact (Hurwitz et al. Reference Hurwitz, Peffley and Mondak2015; Noe-Bustamante et al. Reference Noe-Bustamante, Gonzalez-Barrera, Edwards, Mora and Lopez2021), still associate authoritarianism with favorable views of law enforcement.

Among non-Hispanic whites, authoritarianism is predicted by lower education, Republican partisanship, conservative ideology, older age, and lower income, consistent with prior research (Hetherington and Weiler Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009; Pérez and Hetherington Reference Pérez and Hetherington2014; Torres-Vega, Ruiz, and Moya, Reference Torres-Vega, Ruiz and Moya2021). While lower education and conservative ideology similarly predict authoritarianism for Hispanics, income and age do not. This suggests that socioeconomic class and acculturation shape authoritarianism differently across groups. These results partially reflect Filindra and Kolbe’s (Reference Filindra and Kolbe2022) findings that linked Hispanic white identity to Republican partisanship, conservative ideology, and higher income, though negatively correlated with education.

In sum, these findings raise important questions about whether authoritarianism among Hispanics reflects cultural assimilation into dominant white conservative worldviews or a response to social disorder or group-based threat. Future research should incorporate more refined measures of white identity salience and acculturation to disentangle these mechanisms. Unfortunately, the 2020 ANES dataset limits our ability to test these possibilities directly.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a consistent positive relationship between authoritarianism and support for law enforcement across both non-Hispanic white and Hispanic individuals. Despite facing elevated levels of police discrimination (Correia Reference Correia2010; Lim and Bontcheva-Loyaga Reference Lim and Bontcheva-Loyaga2022), Hispanic communities often adopt authoritarian values that emphasize respect for authority and social order (Henry Reference Henry2011). However, authoritarianism alone does not fully explain these attitudes. Generational status moderates perceptions of law enforcement, with fourth-generation Hispanics expressing more favorable views of police while exhibiting similar levels of authoritarianism to first-generation immigrants. These patterns reflect broader processes of acculturation and white identity salience, through which later-generation Hispanics adopt political preferences that conform to the dominant white majority (Cuevas-Molina Reference Cuevas-Molina2023; Filindra and Kolbe Reference Filindra and Kolbe2022).

This finding also challenges aspects of the bifocal lens perspective (Correia Reference Correia2010; Lim et al. Reference Lim and Bontcheva-Loyaga2022), which argues that immigrants’ authoritarian values coexist with favorable perceptions of American policing despite experiences of discrimination. While our study does not directly test this framework, it highlights how acculturation and identity salience shape attitudes toward law enforcement.

Although limited by the dataset’s scope, this analysis shows that perceptions of law enforcement vary with acculturation, while authoritarianism does not. White identity salience also predicts authoritarianism among Hispanics, underscoring the importance of individual-level identity processes. Future research should explore these dynamics using larger, more representative samples that allow for deeper analysis of acculturation, racial identity formation, and socioeconomic integration. Such efforts will clarify how race-linked fate, cultural adaptation, and support for state authority intersect to shape these attitudes.

Finally, as the Hispanic population continues to expand in the United States, policymakers must prioritize inclusive policing strategies that reflect Hispanic diversity. These efforts include access to language services, community engagement initiatives, and cultural competency training for officers. Reforms must also focus on improving the quality of police encounters, as procedural justice approaches emphasize transparency, fairness, and respect in police-citizen interactions (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2007; Kaariainen and Siren Reference Kääriäinen and Sirén2011; Tyler Reference Tyler2005). Some practitioners argued that even intrusive traffic stops and searches could be offset by the police being polite and professional (see Epp et al. Reference Epp, Maynard-Moody and Haider-Markel2014 for a review of this argument). However, structural inequalities in policing cannot be addressed solely through improved interactions. Sustained efforts to confront racial disparities, expand oversight, and reduce discriminatory practices are essential for rebuilding trust in law enforcement. In an era of polarized debates over policing and racial justice, transformative reform, not public relations, remains necessary to promote equity and legitimacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Benjamin Gonzalez O’Brien, Adam M. Butz, Christopher D. Berk, Hope Martinez, the participants of the Race, Ethnicity, and Politics Research Group, and the reviewers for their feedback on previous drafts of this article.

Funding statement

The authors did not receive any funding for this project.

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendix

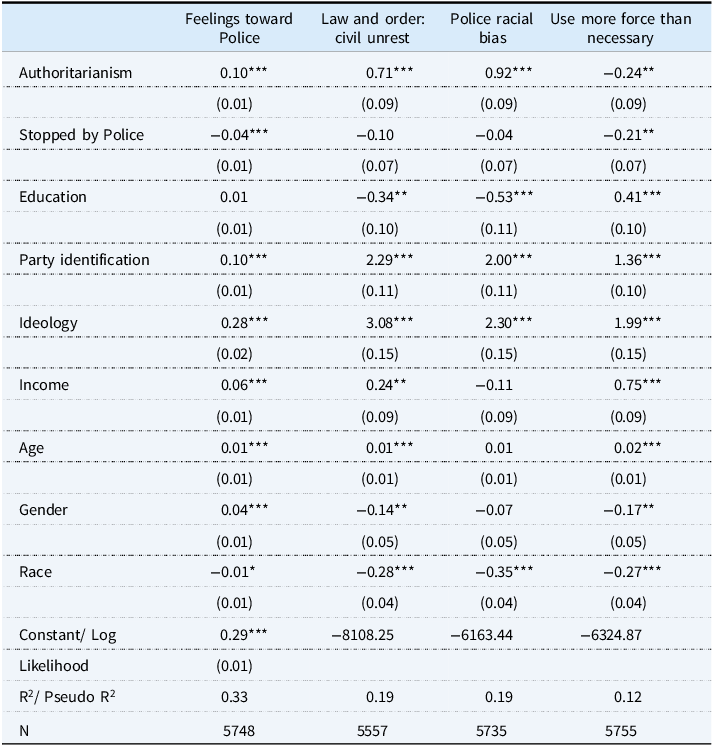

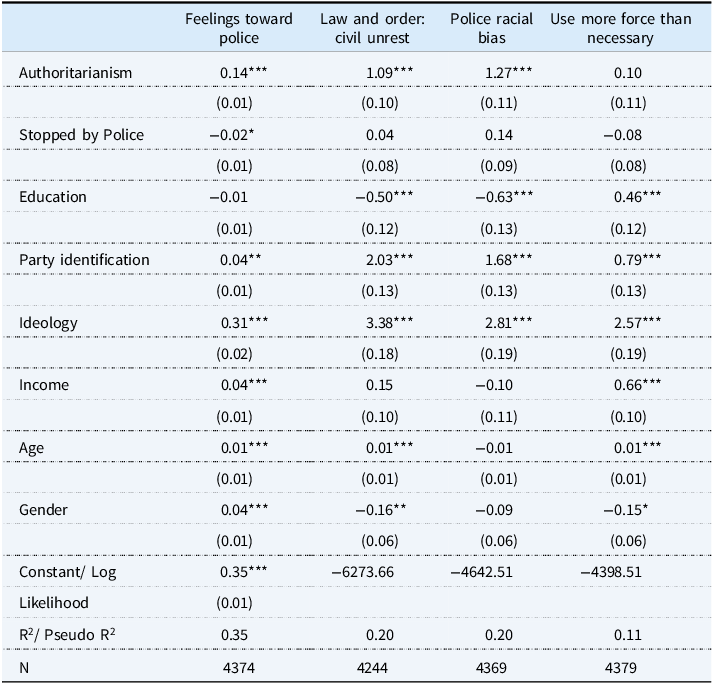

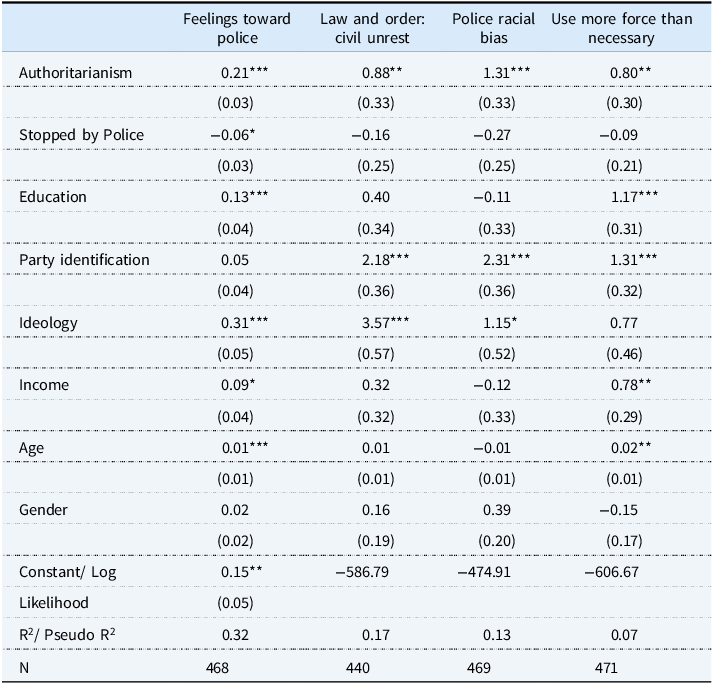

Table A1. Relationship between authoritarianism and law enforcement attitudes

Note: *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001. Feelings toward Police uses OLS Regression to generate coefficient estimates. All other models use ordered logistic regress to generate coefficient estimates.

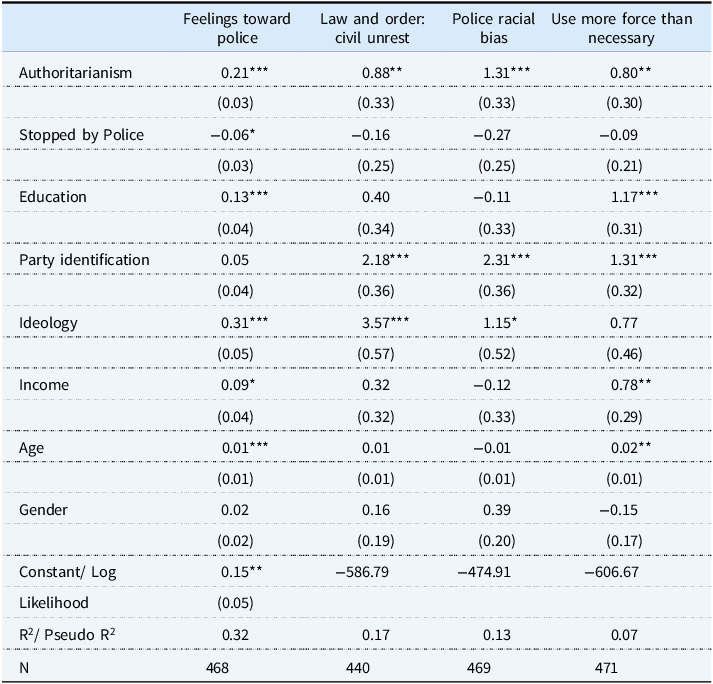

Table A2. Relationship between authoritarianism and law enforcement attitudes for non-Hispanic whites

Note: *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001. Feelings toward Police uses OLS Regression to generate coefficient estimates. All other models use ordered logistic regress to generate coefficient estimates.

Table A3. Relationship between authoritarianism and law enforcement attitudes for Hispanics

Note: *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001. Feelings toward Police uses OLS Regression to generate coefficient estimates. All other models use ordered logistic regress to generate coefficient estimates.