Introduction

Whether sanctions serve a symbolic purpose – signaling disapproval of a target state’s actions (Kaempfer and Lowenberg Reference Kaempfer and Lowenberg1988; Whang Reference Whang2011) – or are used more strategically to influence the target’s behavior (Morgan and Schwebach Reference Morgan and Schwebach1997), democratic states’ ability to impose the sanctions is closely tied to public opinion (Allen Reference Allen2005; Baum and Potter Reference Baum and Potter2008; Canes-Wrone Reference Canes-Wrone2010; Whang Reference Whang2011). In general, domestic public support for sanctions tends to be higher when the issue at stake is particularly salient (McLean and Whang Reference McLean and Whang2014). However, for sanctions to be effective in achieving their intended goals, they must impose real costs on the target state. Doing so often also brings considerable costs to the states that impose them. If these burdens are significant or are perceived to be considerable, the public in the sending state may become less supportive of sanctions (Webb Reference Webb2018). This underscores the importance of studying how the public in the sending country perceives the costs of sanctions, i.e., whether those perceptions are accurate, and how communication about these costs might be improved to maintain or increase public support for sanctions as a foreign policy tool.

In recent years, the scholarly interest in public perceptions of sanctions in sender countries has been growing, and nuances have been sharpened. Some studies examined what drives public support or objection for sanctions. Such studies found that, for example, geopolitical factors, such as Euroscepticism and anti-American views, matter more than economic factors (Onderco Reference Onderco2017); in the context of the European Union’s external and internal sanctions, factors such as trust in institutions and satisfaction with democracy played a role in the level of public support (Pospieszna, Onderco and van der Veer Reference Pospieszna, Onderco and van der Veer2024); benefits to people’s own community increase support as compared to far away benefits (Christiansen, Heinrich and Peterson Reference Christiansen, Heinrich and Peterson2019); while moral grounds for perceptions of sanctions matter (Dietrich Reference Dietrich2021), they matter more in cases where the sender country bears less costs of the sanctions (Heinrich, Kobayashi and Peterson Reference Heinrich, Kobayashi and Peterson2017; Zarpli Reference Zarpli2023). People also support private sanctions (by firms) based on moral grounds even if they would bear some costs of such sanctions (Hart, Thesmar, and Zingales Reference Hart, Thesmar and Zingales2024). Other studies have examined which type of sanctions people tend to support. McLean and Roblyer (Reference McLean and Roblyer2017), for instance, found that people prefer targeted over comprehensive sanctions to minimize the burden on the population of the target state.

The literature on the perception of the costs of sanctions is more limited. Using a conjoint experiment design, Heinrich, Kobayashi, and Peterson (Reference Heinrich, Kobayashi and Peterson2017) and Arı and Sonmez (Reference Arı and Sonmez2025) found that participants supported the sanctions that had lower costs for their country, imposed costs on target countries’ leadership, and achieved long-term policy concessions from the target country.Footnote 1 Kantorowicz and Kantorowicz-Reznichenko (Reference Kantorowicz and Kantorowicz-Reznichenko2025) have found that, beyond economic costs, additional factors, such as the sanctioning coalition and aid program, significantly influence public support for international sanctions in sender states.

While these findings are important, the assumption that people are aware of the actual costs of the sanctions and that their preferences are driven by such objective costs is yet to be examined. It has been found that in other complex policy issues (e.g., public debt), people’s policy preferences are affected by incorrect perceptions of costs (Roth, Settele, and Wohlfart Reference Roth, Settele and Wohlfart2022). Given the complexity and rarity of sanctions’ regimes as a foreign policy, misperception of costs might be expected. Such misperception may also reduce support for sanctions. Therefore, the focus of the current study is on the question of whether people misperceive the costs of sanctions to their country, and if so, whether different interventions may increase the support for sanctions.

In this study, we examine whether different information frames could affect how people perceive the domestic costs of sanctions and, consequently, support for sanctions. To this end, we collect quota-representative samples of respondents from Germany and Poland. Both countries have imposed sanctions on Russia and are providing aid to Ukraine, thus bearing domestic costs. Crucially, however, these countries differ in their level of support for the sanctions, as Poland is recognized as one of the strongest supporters of the sanctions on Russia (e.g., Flash Eurobarometer 2022, Q4).

Using an experimental design, we demonstrate that people overestimate the costs of sanctions, in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) loss resulting from a full embargo, but that this perception can be corrected through the provision of actual information, which in turn enhances the support for the sanction. We also investigate whether using a contrast effect can further change the perception and enhance support. In particular, we contrast the sanctions costs with the GDP loss due to Covid-19, as well as with the GDP loss due to sanctions in the target state. We do not find evidence that using the ‘contrast effect’ can further change the perception and increase support for the sanctions beyond the effect of the actual information. Besides the intention measure, we also use a behavioral measure where participants have the chance to exert efforts to donate money to local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that promote sanctions. We do not find evidence that any of the framings lead to changes in behavior. Therefore, whereas participants are symbolically willing to support the sanctions, and their self-reported attitudes change when updating their beliefs following an information provision of the actual costs, this does not translate into actual action to promote the sanctions.

This study contributes to our understanding of public perception of sanctions, as it suggests that support or lack thereof might be a result of misconceptions rather than a reaction to an objective reality. In this article, we show that correcting misperceptions can influence people’s perceptions and positively shape their attitudes toward sanctions. In doing so, we contribute to the growing literature on misperception correction, which provides rather mixed evidence regarding how people respond to such interventions (e.g., Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin Reference Hopkins, Sides and Citrin2019; Grigorieff, Roth, and Ubfal Reference Grigorieff, Roth and Ubfal2020; Haaland and Roth Reference Haaland and Roth2020; Jørgensen and Osmundsen Reference Jørgensen and Osmundsen2022; Kobayashi and Tanaka Reference Kobayashi and Tanaka2025).

This article also offers valuable policy insights. Given the central role governments and the media play in political communication and shaping of policy preferences, policymakers may consider correcting misconceptions of costs to increase support for their policies. However, such efforts to correct misconceptions should be done with caution, as some studies inform us that certain communication strategies may lead to negative effects, e.g., reduced trust in public authorities or media (Hoes, Aitken, Zhang et al. Reference Hoes, Aitken, Zhang, Gackowski and Wojcieszak2024).

Theoretical framework

The importance of chosen communication strategies and the use of framing to influence public support for different policies has been widely recognized in the political science literature (e.g., Gamson and Modigliani Reference Gamson and Modigliani1987; Nelson and Oxley Reference Nelson and Oxley1999; Druckman Reference Druckman2001; Borrelli and Lockerbie Reference Borrelli and Lockerbie2008; Sheppard and von Stein Reference Sheppard and von Stein2022). In the particular context of public support for international sanctions, framing has also been found effective. For example, Rhee, Crabtree, and Horiuchi (Reference Rhee, Crabtree and Horiuchi2023) investigated the effect of the framing of the (real) Russian medical donation to the U.S. early in the Covid-19 pandemic on the later support for sanctions against Russia. The authors found that when the donation was framed as a benevolent act, participants were less willing to support sanctions against Russia. This effect disappeared when the donation was framed as an opportunistic act. On the other hand, Castanho Silva, Wäckerle, and Wratil (Reference Castanho Silva, Wäckerle and Wratil2022) discovered that only one frame – social norm nudge, i.e., that most citizens are in favor of sanctions – has a positive effect on the public support for an embargo.Footnote 2

Literature in economics has examined whether beliefs can be changed or updated in contexts where the public tends to over- or underestimate economic indicators. For example, Roth, Settele, and Wohlfart (Reference Roth, Settele and Wohlfart2022) focused on the topic of public debt, where people tend to underestimate the degree of their government’s indebtedness. Using an information experiment, the authors demonstrated that providing actual information about public debt made people perceive the debt as too high and be more supportive of policies for cutting debt.Footnote 3 In the context of international sanctions, the domestic public might overestimate the costs of sanctions. Therefore, providing actual information, leading to updated beliefs, might increase the support for sanctions. The first testable hypothesis is therefore as follows:

H1: Provision of information on estimated costs of sanctions leads to a downward adjustment of perceived costs of sanctions and increases public support for sanctions.

Further adaptations of beliefs might occur when the actual costs of sanctions are contrasted with other tangible costs. The idea of the ‘contrast effect’ was developed in the field of psychology and suggests that a reference point can influence people’s perceptions and decisions (Sherif, Taub, and Hovland Reference Sherif, Taub and Hovland1958). For instance, a discount of $20 is expected to be more valued in a purchase of an item costing $30 than an item costing $1000, even though the gain in absolute terms is the same. The contrast effect has been applied in political science literature. Aaroe (Reference Aaroe2012), for example, demonstrated experimentally that due to the contrast effect, partisan cues can shift the views of the opponent citizens even further away from the advocated standpoint. Support for this effect was also found in a study on salient policy issues (Bechtel, Hainmueller, Hangartner et al. Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller, Hangartner and Helbling2015). In the context of international sanctions, the domestic costs of the sender country might be perceived differently and have a different effect on behavior when contrasted with other costs.

Similar predictions, at least with respect to contrasting the costs of sanctions to the target, can also be derived from the social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). Building on this theory, in-group favoritism and out-group derogation may affect how people perceive their country’s foreign policy (Mansfield and Mutz Reference Mansfield and Mutz2009; Mutz and Kim Reference Mutz and Kim2017). For example, Mutz and Kim (Reference Mutz and Kim2017) have examined to which extent people support international trade under different conditions where their country loses/gains relative to the trading partner country. The authors have found the effect of ‘compatriotism’, where participants cared more about their country’s gain rather than an overall global gain. This effect was particularly pronounced for participants higher on the perceived national superiority scale. On the other hand, ‘intergroup competition’ – preferring the trading partner to lose even when it does not add any gain for one’s own country – was less pronounced. Such sentiments were only found among the group of participants high on the social dominance orientation.

In the context of international sanctions, in-group favoritism and out-group derogation may also be relevant for support for sanctions. In particular, if inter-group competition is prominent for perceptions, the willingness to accept domestic costs of sanctions may increase if the sanctioned country bears higher costs of the sanctions.

The two theories lead us to the second testable hypothesis:

H2: Contrasting the estimated costs of sanctions with other costs leads to a greater downward adjustment of perceived costs of sanctions and further increases public support for sanctions as compared to the situation where contrasting is absent.

If the dominant effect is the contrast effect as compared to the inter-group competition, then the perception of the presented costs of Covid-19 should be comparable to those of the target (out-group) country. If, on the other hand, intergroup competition is more prominent, the effect of the presentation of sanctions’ costs to the out-group should be more pronounced.

Experiment design

This study uses data stemming from samples of respondents from Germany (N = 1,152) and Poland (N = 1,117) collected in April–May 2022. The samples are quota-representative in terms of age, gender, region, and education. We used the services of an international survey firm Dynata, to recruit participants and administered the experiments in the local languages using Qualtrics. All participants gave their informed consent to take part in the study. The study has been approved by the ethics committee.Footnote 4

The experimental design was generally inspired by Roth, Settele, and Wohlfart (Reference Roth, Settele and Wohlfart2022). First, we wanted to elicit participants’ beliefs with respect to the costs to their country of a full embargo on Russian oil, gas, and coal (a much-debated sanction shortly before the launch of our survey). To this end, we have asked the participants to provide their own estimate of the costs of the embargo as a percentage loss to the country’s GDP over the course of one year.Footnote 5 Despite the frequent mention of the concept of GDP in the media, it was not expected that all participants would understand this concept or would be properly aware of its growth. Therefore, prior to eliciting the beliefs of the respondents, we explained what GDP is. In addition, the participants were randomly divided into two groups. One group did not receive any examples of GDP growth. The second group received an example of the GDP growthin Poland, Germany, and the EU in 2019 (an anchor to rely on). This stage was important to understand participants’ baseline beliefs about the costs of a potential embargo.

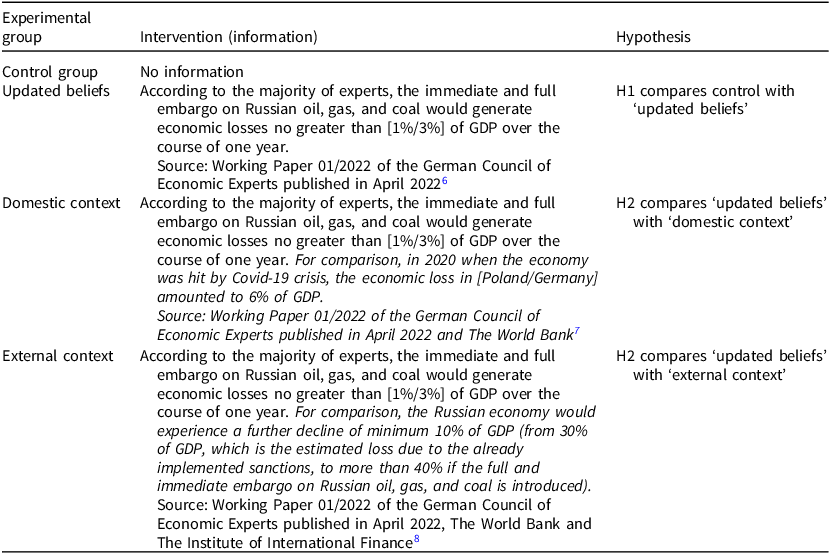

In the next stage, to test the effect of information provision, we randomly divided the participants into four experimental groups. The experimental interventions and the corresponding hypotheses are presented in Table 1. The control group received no information and served as a reference point to tease out the effect of the information provision.

Table 1. Experimental groups

Note: In brackets, we display what information the Polish and German respondents, respectively, were exposed to. The loss of GDP due to Covid-19 was calculated as the difference between projected GDP growth in the year 2020 (counterfactual) and the actual growth in this year.

To examine the effect of the different information provisions, we have used two measures, i.e., cost perception and self-reported support for the embargo (intention measure) and active support (behavioral measure).

Regarding the intention measures, participants were asked to indicate to what extent they agree with two statements on a 1–7 Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’ and 7 = ‘strongly agree’). The statements constituting the dependent variables (DV) 1 and 2 employed in this study are as follows:

The potential economic costs for the [Polish/German] economy of the immediate and full embargo on Russian oil, gas, and coal are too high (DV1: cost perception).

The government should introduce the immediate and full embargo on Russian oil, gas, and coal (DV2: self-reported support for the embargo).

To examine whether the information provision also affects actual decisions, we used a revealed preference measure based on Lange and Dewitte (Reference Lange and Dewitte2022). All participants were offered to take part in a number identification task (NIT). The task included three pages where the participants needed to identify specific numbers out of 40 numbers. Each time the participants were requested to first indicate YES/NO to the question of whether they would like to perform this task. Based on this, they were either referred to the task or not.

The task was voluntary in the sense of not affecting respondents’ baseline payment. However, we have indicated that for each page they fill out 90% correctly, we will donate €0.20 to an NGO that strongly supports the end of Russian oil and gas imports. The chosen NGOs signed a public call to reject any imports of fossil fuels from Russia to cut off the main source of revenue for Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. To measure the behavioral effect of the frames, we used two dependent variables: the willingness (saying YES) to perform the NIT (DV3) and the correct identification of at least 90% of the numbers (DV4). For the full flow of the experiment, including the NIT, see the online Supplementary Material.

The use of effort tasks to measure people’s behavioral support of some policy has been developed and validated in different recent studies. These tasks are meant to offer cost-effective behavioral measures. For example, several studies have used a similar numbers task to examine the level of effort participants are willing to exert for donation to an environmental cause (Lange and Dewitte Reference Lange and Dewitte2022; Vlasceanu, Doell, Bak-Coleman et al. Reference Vlasceanu, Doell, Bak-Coleman, Todorova, Berkebile-Weinberg, Grayson, Patel, Goldwert, Pei, Chakroff, Pronizius and van Bavel2024). In addition, Lange, Steinke, and Dewitte (Reference Lange, Steinke and Dewitte2018) investigated in the lab whether people would choose to finish the study faster at the expense of increased CO2 emissions (display of led lamps) or would be willing to stay longer in the lab to avoid such an option. Similarly, Farrelly, Bhogal, and Badham (Reference Farrelly, Bhogal and Badham2024) provided participants with a choice between performing a trivial task or passively accepting an environmentally damaging option (agreeing to receive unnecessary emails that led to CO2 emission). Farrelly, Bhogal, and Badham (Reference Farrelly, Bhogal and Badham2024) have also validated the measure by demonstrating that people higher on pro-environmentalism were more willing to perform the trivial tasks and avoid the emails. We have designed our behavioral measure building on the insights from these studies. The willingness to take part in trivial tasks and exert effort to increase accuracy was meant to proxy the willingness to act in order to support sanctions.

Results

As expected, participants in both countries significantly overestimated the expected GDP loss in their country as a result of a full energy embargo. The average estimate of the GDP loss by the public was 12.2% in Poland (16.8% when no anchor was given and 7.7% with the anchor) and 14.2% in Germany (18.7% when no anchor was given and 9.6% with the anchor). The detailed results of anchors and people’s tendency to overestimate the costs of sanctions can be found in the online Supplementary Material.

Intention measures

Given that people grossly overestimate the costs of sanctions, we turn to analyzing the effects of the information provision. The initial step is to examine whether simply providing information on the expected (estimated) domestic costs of the sanction to the sender country would make people change their perception of the costs (DV1), as well as change the support for the sanctions (DV2). Figure 1 illustrates that in both countries, relative to the control group, simply informing the participants about the expected costs (‘information’) decreases by about 0.4–0.7 points their perceived costs of the embargo (Germany: |t| = 3.2, p = 0.001, Poland: |t| = 5.0, p < 0.001), as well as increases by roughly 0.4 points their support for the sanctions (Germany: |t| = 2.6, p = 0.008, Poland: |t| = 2.9, p = 0.003).Footnote 9 Thus, we find support for H1. As expected, one can also observe a generally greater support for the energy embargo among the Polish respondents. For formal results from the OLS regressions, as well as the full distribution of responses on the 1–7 Likert scales, see the Supplementary Material.

Figure 1. Perception of costs and support for a full embargo.

We have also predicted that putting the expected domestic costs of the embargo in context might trigger the contrast effect and/or inter-group competition sentiment and even further change people’s perception and level of support for the sanctions (H2). As illustrated in Figure 1, contrasting the embargo costs with the loss due to Covid-19 as well as with the Russian expected GDP loss did not have an additional effect beyond the effect of the actual costs’ information. All in all, we see a statistically significant difference between the contrast effect groups and the control group, but there is no statistically significant difference between the contrast effect groups and the baseline information group (see Supplementary Material). While actual information matters, adding contrasting information (domestic costs of another crisis or the costs of the target country) does not increase the support further. The same pattern is identified for both countries. Therefore, we do not find support for H2.

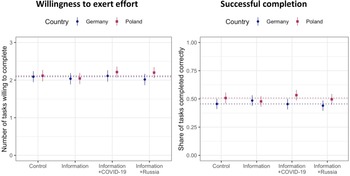

Behavioral measures

In light of the literature on the intention-behavior gap (Sheeran Reference Sheeran2002), we have also added a behavioral measure of support for the embargo. Participants had the opportunity to exert additional effort to donate money to NGOs that pressure for a full embargo in their country. We measured their willingness to participate in the effort task (DV3) and their actual effort as captured by correctly completing at least 90% of the task on each page (DV4). As Figure 2 demonstrates, neither of the treatments (information on estimated costs of an embargo, contrast with Covid-19 costs, contrast with costs on Russia) affected people’s behavior. This applies to the willingness to exert effort, as well as to the level of effort exerted (see also formal OLS regression models in Supplementary Material). Therefore, we find no support for H1 and H2 using the behavioral measures.Footnote 10

Figure 2. Behavioral measure for support of a full embargo.

Robustness checks and subgroup analyses

It is important to note that by and large the results replicate if we limit our samples to only those respondents who initially overestimated the costs of an embargo, i.e., they estimated the costs to be larger than 1% of GDP in Poland and 3% of GDP in Germany. While there is some indication that the contrast effect with Covid-19 leads to an even greater adjustment of perceived costs in Germany as compared to the sole information provision (|t| = 1.9, p = 0.061), this does not translate into an even greater support for sanctions (|t| = 1.2, p = 0.250). All these additional results are reported in the Supplementary Material.

While the previous analysis focused on average treatment effects, we also explore heterogeneous effects. In both countries, the positive impact of information treatments on support for sanctions is mainly driven by respondents residing in the West rather than the East. In Poland, the effects are stronger among voters inclined toward non-populist parties and those leaning left or center. Similarly, in Germany, non-populist voters show stronger (positive) responses, except that populist voters respond positively to the basic information treatment (without contrasting information). Right-leaning respondents in Germany generally show more positive effects, except when the treatment also includes contrasting information on Russia’s GDP losses.

Income also matters: in Poland, higher-income respondents drive the effects; in Germany, lower-income respondents react more to the basic information, while higher-income groups respond more to the treatments containing contrasting information. Finally, the GDP anchoring condition (providing further information about the economic growth in Germany and Poland in previous years) makes little difference except for the treatment contrasting Russia’s GDP loss, which is ineffective for non-anchored respondents in Poland and anchored ones in Germany. Full subgroup analyses are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Discussion

In this article, we focused on the public perception of the costs of international sanctions in the sender state. In democratic countries, public support is crucial for sustaining long-lasting foreign policy interventions, including sanctioning regimes. Hence, studying public support and examining tools that have the potential to build and enhance this support is key.

We have used the salient context of the 2022 Russian aggression against Ukraine and conducted an experimental survey on quota-representative samples of respondents from Germany and Poland, which both provide extensive support to Ukraine and impose sanctions on Russia. The specific sanction we used to provide a real, rather than a hypothetical, context was a full embargo on Russian coal, gas, and oil – a sanction that was saliently discussed in those countries just before we conducted our study.

Our starting assumption was that people might overestimate the expected costs of sanctions and, consequently, be less inclined to support the sanctions. Therefore, the first question we have examined was whether updating people’s cost calculation by providing the best estimate of potential costs would change their perception of the costs and self-reported support for the sanction. We found that it did. However, this support did not translate into action, as demonstrated by our behavioral measure of performing an effort task in order to donate money to NGOs acting to promote the full embargo on Russian oil.

Next, we examined whether contrasting the costs of the sanction, in addition to providing its evidence-based estimated size, would change the perception of the costs and enhance self-reported support for it. We found no evidence that contrasting the costs of the embargo with the domestic costs of the Covid-19 crisis, or with costs imposed on Russia, had any additional effect on perception and support. It also had no effect on the decision to take action within our behavioral measure.

While domestic issues typically hold greater importance for the public than foreign policies, when the latter become salient, the public are likely to form preferences (Fordham and McKeown Reference Fordham and McKeown2003; McLean and Whang Reference McLean and Whang2014; Kono Reference Kono2017; Wallace Reference Wallace2024). In the case of high-profile conflicts, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, foreign policies are expected to have greater significance for the public. Similar to other complex issues (such as GDP and public debt), people often under- or overestimate the costs of policies. This was confirmed in our study, where individuals overestimated the costs of sanctions on Russia. The value of our research lies in demonstrating that correcting such misconceptions may lead to greater support for sanctions. While we observe a gap between expressed and actual behavioral support (which we attempt to explain below), expressed support still holds considerable weight. For policymakers to sustain international sanctions, they need public support and legitimacy. Even if people are not actively working to promote the sanctions, their expressed support may indicate that they are unlikely to oppose or express dissent against them.

As the political communication literature highlights the crucial role of politicians, the media, and other actors in mobilizing support for various policies (McNair Reference McNair2017; Lim and Seo Reference Lim and Seo2009), our results also offer valuable insights for policymakers. They suggest that if politicians recognize the public’s misperception of the costs of sanctions, they may have an incentive to correct these misconceptions to increase support for their policies. However, communication strategies must be carefully crafted, based on a clear understanding of the source of the misperception. Rushed communication could undermine trust in the information being presented (Hoes, Aitken, Zhang et al. Reference Hoes, Aitken, Zhang, Gackowski and Wojcieszak2024).

Although we have focused on a specific conflict, we believe our findings have broader implications for understanding public attitudes toward sanctions. The Russia-Ukraine war has been especially salient for our participants due to their proximity to the conflict and its implications for their countries. In such cases, people typically seek out information on their own and form strong opinions. Therefore, any effects we observe signal the strength of the intervention. This suggests that similar interventions in less salient conflicts, where people may have less entrenched preferences (weaker priors), could be even more effective.

Despite contributing to the literature on international sanctions perception and providing practical policy implications, our study leaves several open questions, which should be tackled by future research on this topic. For our research, we have chosen a specific type of sanction, fossil fuel embargo. Despite being a prominent sanction in the context of the current war and widely relevant for other contexts, there are other types of sanctions. Therefore, in future research, perceptions of other types of sanctions should be examined. In addition, our behavioral measure showed that people were not incentivized to take action, even when their knowledge about the expected costs was updated. This is despite their self-reported support. Future research should look at the reason why it is the case. Is it due to the intention-behavior gap, or maybe a different type of action (as opposed to donating money to an NGO) would be more welcome by respondents? Finally, we acknowledge that the effects observed in this article have only been examined in the short run, and further research is needed to determine whether they persist over a longer period.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676526100656

Data availability statement

Replication material for this study is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RHXWWV.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially undertaken within the framework of the EUMOTIONS project (The Role of Emotions in EU Foreign Policy) financed by the Starters Grant from the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science. We thank the EJPR editor and the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which considerably strengthened the paper. We are also grateful to the participants of the 14th Annual Conference of the European Political Science Association in Cologne, the 2023 ‘Dag van het Gedrag’ conference in The Hague, and the 1st Conference of the European Society for Empirical Legal Studies in Warsaw for their helpful feedback. All remaining errors are our own.

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interest to report.

Ethics approval statement

This study has been approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of Erasmus School of Law (approval number ETH2122-0576).

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

All materials are original from the authors; thus, there is no need to obtain any permissions.