“International law and institutions are for various reasons under great stress,” read the opening line of the Journal’s invitation to use classic books as a starting point for reflecting on today’s world.Footnote 1 With that as the backdrop, it is not difficult to understand why the editors suggested we revisit Hersch Lauterpacht’s The Function of Law in the International Community.Footnote 2 Nowadays, this book provides the intellectual foundation of the project to judicialize politics. In publications of the last three decades, Lauterpacht’s Function is frequently cited as the authority for the idea that the international judge is at the heart of the international rule of law and therefore a key actor for justice and world peace.Footnote 3 At a time when not just the judicialization of politics is seen as under attack, but also the notion that interstate relations should be subject to legal constraints has been weakened, rereading the Function may reinvigorate the project of “standing tall for the rule of law.”Footnote 4

However, a reader who opens the Function with the hope of a quick energy-and-confidence boost will likely end up disillusioned. Spanning over four hundred pages, six parts, and twenty chapters, the Function is not a piece of academic writing that one would use as an exemplar of an arrow-to-goal thesis that today’s PhD candidates are told to write. The text does not directly tackle the topic suggested by the title—the function of law in the international community—until the very last pages. The idea of the centrality of the judge is more a premise than the book’s argumentative arc. Writing styles may have changed; perhaps today’s readers have less time—literally and figuratively—for anything but to-the-point writing. However, as we will show, reviewers at the time of the Function’s publication already criticized the book’s title and repetitiveness.Footnote 5 Moreover, contemporaneous books on related topics—for instance, by Helen May Cory and Annemarie Ascher—were in fact much more compliant with the arrow-to-a-goal instruction.Footnote 6 How, then, did this book become a cornerstone of the field of international law?

In this article, we show the Function’s changing fortunes: from its mixed reception, to becoming one of the main doctrinal and intellectual foundations of the judicialization of politics, to ultimately embodying legal cosmopolitanism as the discipline’s dominant sensibility. This rise is in sharp contrast to the books by Lauterpacht’s female contemporaries Cory and Ascher who, writing on related topics, received more positive reviews at the time but are hardly ever cited anymore. The Function “won” in at least two ways. First, many of Lauterpacht’s views on the doctrines that he discusses in the book have become conventional wisdom. In the Function, you will find Lauterpacht involved in a sustained polemic against his predecessors and contemporaries on a range of doctrines, including those of “de maximis non curat praetor,” “lacunae” in the law, and “political disputes” (pp. 50–53, 72, 139–42, 168–72). Today, however, the book reads as a statement of current and conventional views on such doctrines. Secondly, and more significantly, the Function’s premises have become the discipline’s premises, for instance, that more international adjudication equals more international justice and that more international adjudication equals more peace—core beliefs of the legal cosmopolitan project. The Function was a frontrunner: written during the interwar period, it captured a disciplinary sensibility that would coalesce only later, in the post-1945 period, and that would become the dominant sensibility post-1989. The victory of the Function’s legal cosmopolitanism was, however, more due to dynamics external and internal to the profession than to its own substantive arguments. Outside the profession, geopolitical developments in the 1990s (the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the post-Cold War globalization) provided strong tailwinds for the sensibility underpinning the Function to spread among the legal profession. International lawyers were confident that the increase of trade, communications, and cooperation would be accompanied by the proliferation of courts, realizing the judicialization of international relations.Footnote 7 More broadly, international lawyers who believed in the end of the Cold War as an ideological victory, saw and promoted the judicialization of politics as central to the liberal internationalist project.Footnote 8 But we will show that it was thanks to institutional and intellectual factors internal to the profession that it was specifically the Function, rather than other books, that became the foundation of legal cosmopolitanism.

While the Function embodies now conventional legal doctrine and its legal cosmopolitanism is still largely alive and kicking as the expression of a disciplinary sensibility—think of the hopes and professional excitement expressed when courts get involved in addressing the world’s headline crises, whether it is climate change, Ukraine or Gaza—we also argue that it is “falling.” By that we do not mean that the book has become any less popular or that the Function’s legal cosmopolitanism has been defeated—dead at the hands of legal pragmatism or political realism. Rather, when moving from the rise to the fall, our argument shifts analytical mode, from studying the popularity of the book and its ideas to assessing the problems of its underlying assumptions. When speaking of the Function’s fall, we argue that it is now evident that its functionalism is not delivering due to questionable assumptions. The Function powerfully articulates a legal cosmopolitan sensibility when postulating a series of interlocking functions that connect legal thought and doctrine with the international community’s ultimate purposes: the function of law is to secure peace; the judge’s function is to objectively assert the law; the international lawyer’s function is to choose the correct legal doctrines and theories that in turn support the judicial function and the function of international law. In sum, Lauterpacht’s assumption is that by choosing the right legal doctrine (for instance, on reservations, on justiciability, on rebus sic stantibus, on abuse of rights, on non liquet), the international lawyer promotes peace (and justice, a value that Lauterpacht touches upon more as an afterthought). However, these functions do not always align as harmoniously as Lauterpacht assumes. By speaking of a “fall” we highlight the potential dissonance between these functions. After all, it is far from evident that doctrinal mastery—artfully selecting the “right” legal doctrine—materially advances the cause of peace, or justice for that matter.

I. The Rise: How the Function Became the Intellectual Foundation of the Judicialization of Politics

A reader who may have expected to find in the Function a sociological understanding of law’s role in the international community will be surprised by the table of contents. The first section begins with “The Doctrine of the Limitations of the Judicial Process in International Law.” Most of the book’s over four hundred pages are dedicated to refuting a set of legal doctrines that Lauterpacht sees as restricting the function of law, primarily because they limit the judicial function by curtailing the authority of the international judge to adjudicate international disputes. He frames his disagreement with his predecessors and contemporaries in doctrinal terms; the book’s title notwithstanding, Lauterpacht rarely recognizes that the disagreement was also rooted in different assumptions about the function of law. It is only in the book’s final pages that Lauterpacht touches upon the function that is presumed throughout the book: the promotion of peace. There he argues that:

[I]t is essential that international lawyers should develop an attitude of criticism in regard to the very effective—although now somewhat trite—argument that law is not a panacea. Law can never, on the plane of mere fact, become an effective substitute for war. But that does not mean that law is not in itself a powerful constituent element of peace. (P. 437.)

He then specifies how he sees this: “The reign of law, represented by the incorporation of obligatory arbitration as a rule of positive international law, is not the only means for securing and preserving peace among nations. Nevertheless it is an essential condition of peace” (id.). The chain of reasoning in these sentences underpins the entire book: peace requires the reign of law and the reign of law requires international judges to have and exercise jurisdiction. On the final page, he goes a step further by presenting peace as a “metaphor for the postulate of the unity of the legal system” (p. 438). Work on the unity of the legal system is thus work on peace.

In some ways, then, the book reads like a sacred text. Assuming rather than justifying its central contention—in this case, international law’s function—the book seeks to create rather than probe a disciplinary practice. When Lauterpacht refers to the international judge as part of a priesthood,Footnote 9 one may see his audience, international lawyers, as members of a congregation. The Function reads like a breviary when Lauterpacht offers the congregation firm guidance on which doctrines to accept and which to reject in order to defend international law and advance peace. See, for instance, Lauterpacht on the doctrine de maximis non curat praetor:

There ought to be little doubt as to the legal repugnancy of the doctrine in question. To restrict law to small matters is to reduce to a minimum its proper function, namely, that of preservation of peace and of prevention of recourse to force…. The idea of the limitation of the function of judicial settlement to matters of little importance, obnoxious as it is as a general proposition, is also misleading from the point of view of the actual content and scope of international law. (P. 169, emphasis added.)Footnote 10

In Lauterpacht’s vision, if lawyers, scholars, and judges pursue the right legal thought, they will defend the right legal doctrines and thus fulfill the function of law. By connecting thought, doctrine, and function, Lauterpacht offers international lawyers a mission. Fighting hard for dry legal doctrine, is to stand tall for the rule of law and to advance international peace.

The Function is certainly not the only work that articulates a functionalist perspective and reminds international lawyers of their role in the project of expanding the international rule of law. The interwar period is full of similar works.Footnote 11 Take Helen May Cory’s Compulsory Arbitration of International Disputes, published by Columbia University Press in 1932, a year before Lauterpacht’s Function came out. Clearly structured, the book analyzes the idea of compulsory adjudication historically, ending with observing a significant increase in the number of compromissory clauses. Cory concludes: “A nation may settle its disputes by voluntary arbitration as effectively as by compulsory arbitration, but only by compulsory arbitration can it remove that uncertainty as to its intentions which is one of the greatest obstructions to an international sense of security and hence to the peace of the world.”Footnote 12 Lauterpacht does not cite Cory’s book—it may have come out too shortly before his own went to the press—even though the idealism of her historical analysis resonated with Lauterpacht’s project.

That the Function has become the intellectual foundation for the judicialization of politics would have surprised reviewers writing at the time that the book came out. Many of Lauterpacht’s contemporaries found the Function hard to penetrate. Reviewing it in the Yale Law Journal, Thomas Baty opened with:

Just as for Austin the essence of law was the definite human legislator, so for Professor Lauterpacht the essence of law is the definite human judge. This thought is the real core of his work, and it is to be regretted that it was not taken as his thesis, and advanced and defended as such. It is not until chapter XX, at the very conclusion of the work, that we get a formal presentation of the proposition; and then the proofs which the reader is offered are singularly unconvincing.Footnote 13

A review in the American Political Science Review opens by pointing out that the book does not contain what it says on the box:

The title of this book is misleading. The function of law in the international community is considered only incidentally in its bearing upon another and somewhat narrower problem, that of the limitation of the judicial process to the settlement of particular classes of disputes.Footnote 14

Philip Jessup mentioned repetitiveness in his evaluation.Footnote 15 Reviewer Frederick Dunn, a lawyer and political scientist, also criticized the methods: “he accepts uncritically the conventional notions of the nature of law and justice; he constantly employs terms of evaluation in analytical reasoning without first establishing his standards of value; he fails repeatedly to provide frames of reference for his general statements.”Footnote 16

Contrast these reviews with that of a contemporaneous book partially on the same topic: Annemarie Ascher’s Wesen und Grenzen der internationalen Schiedsgerichtsbarkeit und Gerichtsbarkeit, published in 1929, four years before Lauterpacht’s Function. In 1930, a reviewer in AJIL described that book as “a concise, systematic and well written statement of the origin, nature and functions of, and the contrast between, the International Court of Arbitration and the World Court of Justice,” concluding his review of her book with the words “Multum in parvo”—“a great deal in a small space.”Footnote 17 (Nonetheless, Ascher’s work, like Cory’s based on a PhD thesis, does not appear in the LSE professor’s Function.)

The Function also received praise: for its comprehensiveness; its exhaustiveness; and its engagement with foreign literature and its extensive bibliography and annexes. But the positive reviewers did not see the idea of the judge at the heart of the international rule of law as the book’s greatest contribution; most valued the book’s discussion of some specific doctrines, especially non-justiciabilityFootnote 18 and non liquet.Footnote 19

In the initial decades after its publication,Footnote 20 the Function was mostly cited for those specific doctrines or for points that Lauterpacht touched upon in passing. If we look, for instance, at AJIL articles that cited the book in the 1930s, we see that it was on matters such as the definition of aggression,Footnote 21 the clausula rebus sic stantibus,Footnote 22 declarations of war,Footnote 23 the understanding of the term “international community,”Footnote 24 and the concept of “peaceful change.”Footnote 25 In the 1940s and 1950s, the book was mainly referred to for its discussions of justiciability,Footnote 26 the binding force of international law,Footnote 27 and its discussion of non liquet.Footnote 28 After Lauterpacht’s sudden death in May 1960, two AJIL articles published in 1961 reflected on Lauterpacht’s overall contribution to the development of international law. It is in the discussion of his overall scholarly oeuvre and his judicial opinions that the authors highlight the Function as his most important work, focusing on the role of the international judge.Footnote 29 But AJIL articles in the 1960s–1980s continued to cite the book mostly on specific doctrines and issues, for instance the application of general principles,Footnote 30 the system of national judges in international courts,Footnote 31 and the concept of a “political dispute.”Footnote 32 In the 1990s, it was still the discussion of legal versus political disputes that got the attention.Footnote 33 In the 2010s and 2020s, however, the references shifted to Lauterpacht’s belief in the critical role of international judges.Footnote 34 A review of several books on international courts opened by invoking Lauterpacht in support of the claim that “judges play a central role in the promulgation of the rule of international law and help to keep the peace among states.”Footnote 35 In that review, Lauterpacht’s thinking—not just the Function but also some of this other work—provided the theoretical framework for evaluating the new works.

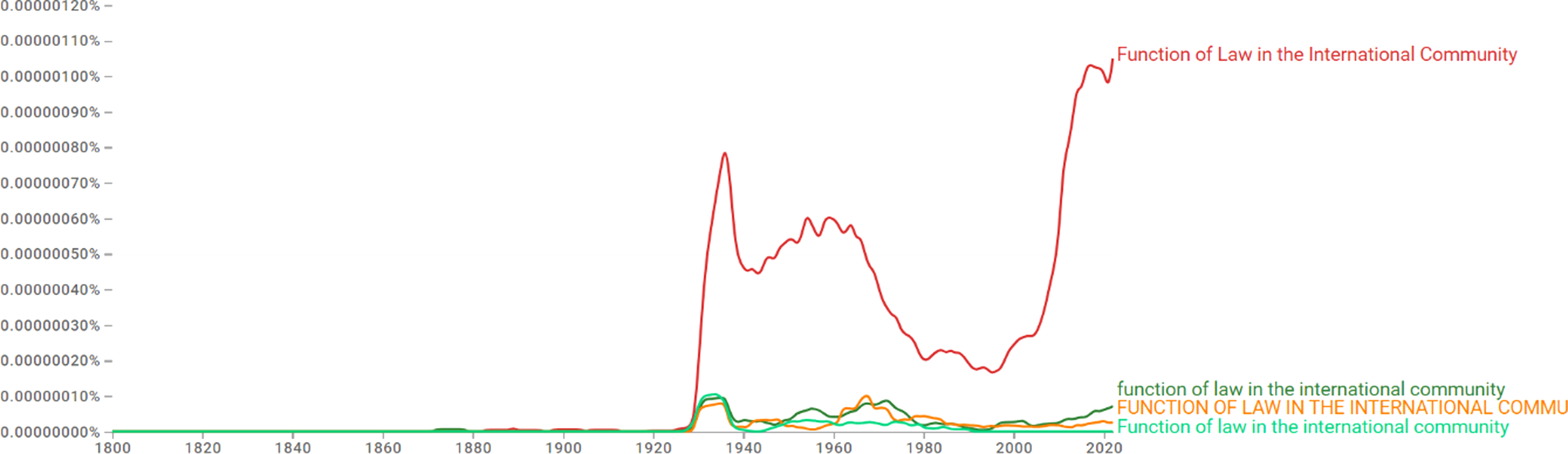

Moving from AJIL to citations in books digitized in the Google Books database, we can also observe a quantitative shift in references to the Function: The first peak of invocations of the Function in this Google N-gram occurs when the book has just come out. The references then decline, but increase again after the late 1990s, with a stark increase as of the 2010s. What happened?

Enter Martti Koskenniemi. Koskenniemi had engaged with the Function in his book From Apology to Utopia, published in 1989. As part of his structural analysis of international law as argumentative practice, Koskenniemi discussed Lauterpacht’s—and many others’—views on topics such as legal versus political disputes, judicial legislation, and the completeness of international law. In 1997, however, he published an article entirely on Lauterpacht, as part of a Symposium dedicated to Lauterpacht in the European Journal of International Law’s rubric “The European Tradition in International Law.”Footnote 36 In this intellectual biography, Koskenniemi argued that “Lauterpacht’s main contribution is to have articulated with admirable clarity the theoretical and historical assumptions on which the practice of international law is based.”Footnote 37 But, as we have argued above, Lauterpacht himself had not spelled out those assumptions. Rather, Koskenniemi extrapolated Lauterpacht’s assumptions from his writings, judgments, and context. And the Function was, according to Koskenniemi, Lauterpacht’s “most important doctrinal work.”Footnote 38 After a careful analysis, Koskenniemi concludes his discussion of the book by citing one sentence: “There is substance in the view that the existence of a sufficient body of clear rules is not at all essential to the existence of law, and that the decisive test is whether there exists a judge competent to decide upon disputed rights and to command peace.”Footnote 39 Koskenniemi then brings this sentence to the present in which he is writing, the late 1990s, observing:

Lauterpacht’s nominalism is ours, too. Our own pragmatism stands on the revelation that it is the legal profession (and not the rules) that is important…. Function of Law puts forward an image of judges as “Herculean” gap-fillers by recourse to general principles and the law’s moral purposes that is practically identical to today’s Anglo-American jurisprudential orthodoxy.Footnote 40

And speaking of Lauterpacht’s work more generally, he identifies “Lauterpacht’s utopia” as a “world ruled by lawyers.”Footnote 41

In this way, Koskenniemi provided the post-Cold War project of the judicialization of politics with a historical intellectual father. And that father was easily adoptable: in the 1990s, Lauterpacht’s story struck a chord with the prevailing liberal universalism. It was not just Lauterpacht’s ideas, but also his personal story that increasingly became of interest. The obituaries of the 1960s had given Lauterpacht’s work much praise, but had barely reflected upon the historical and personal context in which his thoughts had developed. Immediately after his discussion of the Function, Koskenniemi, however, continued his article with a detailed account of Lauterpacht’s early life as a Jew in Galicia, where the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire had gone hand in hand with rising nationalism and antisemitism, the challenges he faced as a Jew at the University of Vienna, and his assimilation in the UK. Lauterpacht’s cosmopolitanism resonated with the cosmopolitan esprit du temps of the late 1990s/early 2000s.

On its own, Koskenniemi’s 1997 article may not have been enough to proliferate the idea of Lauterpacht as intellectual father of the judicialization of politics. But his work on the article led to an invitation from the Lauterpacht Centre for International Law—founded by Hersch’s son, Sir Eli Lauterpacht, who had contributed to the same EJIL Symposium—to give the 1998 Hersch Lauterpacht Memorial Lectures. The EJIL article on Lauterpacht constituted one chapter of the book that would come out of those lectures: The Gentle Civilizer of Nations, Koskenniemi’s second famous and well-read book. Lauterpacht’s belief that international judges should rule the world was part of what Koskenniemi called the project of gentle civilizing. Lauterpacht, and especially his Function, are key protagonists in Koskenniemi’s argument about “the rise and fall of international law.” To Koskenniemi, Lauterpacht represents the end of the “rise” of international law, and the beginning of the “fall,” with rise and fall referring to the field’s sensibility. According to Koskenniemi, Lauterpacht’s Function still espoused a professional sensibility—a sensibility of being the juridical conscience of the civilized world—that had come to the fore around 1870. But Koskenniemi also identifies in the book, and especially Lauterpacht’s subsequent writing, a turn toward pragmatism, which, as a general shift in the field, he sees as the discipline’s “fall” since 1960. In Koskenniemi’s words, “The Function of Law is the last book on international theory—the theory of non-theory, the acceptable, sophisticated face of legal pragmatism.”Footnote 42

Koskenniemi expanded his intellectual biography of Lauterpacht in a contribution to the 2004 edited collection Jurists Uprooted, a study of the contribution of refugee and émigré legal scholars in the UK.Footnote 43 Koskenniemi presented Lauterpacht’s life as a metaphor for the emergence of modern international law.Footnote 44 Then, in 2008/2009, Koskenniemi gave the Function a final push by labeling it not merely Lauterpacht’s most important work, but also “the most important English-language book on international law in the 20th century.”Footnote 45

Koskenniemi thus played a significant role in the rise of the Function’s fame. He did not do so as a disciple; as a key protagonist in the emergence of critical approaches to international law, Koskenniemi interrogated the intellectual foundations of international law and found in Lauterpacht an example of a disciplinary sensibility. Koskenniemi’s spotlighting of the Function, then, is not explained by agreement with Lauterpacht’s positions on all the legal doctrines that Lauterpacht discusses, or even the book’s underlying assumptions. Rather, for Koskenniemi, the Function stands as a monument of a professional sensibility. In the field of international law, however, the Function has become better known for the idea that Koskenniemi highlighted as central to the book—lawyers as rulers of the world—than for the arguments for which he used the Function as an illustration.

After Koskenniemi’s multiple pieces on Lauterpacht, the Function and its author more generally continued to attract attention. In 2011, Sir Eli republished the book, inserting his father’s hand-written annotations to the first sixty pages.Footnote 46 In the 2010s, Philippe Sands’s best seller East West Street made Lauterpacht a household name. Where Koskenniemi had put intellectual ideas in historical and personal context, Sands emphasized the personal story, with books and articles appearing only as personal milestones.Footnote 47

The rise of Lauterpacht’s Function from a book appreciated for some doctrinal points to a keystone of the discipline is thus at least partially explained by fresh engagement with, historicization, and interpretation of the work more than fifty years after its publication. That this happened to the Function is in part thanks to Lauterpacht’s overall career trajectory: the impressive growth from Kelsen’s and McNair’s PhD student to lecturer at the LSE, Whewell Professor of International Law and Judge at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as well as the overall oeuvre of work and judicial opinions gave Lauterpacht a name that also benefited the Function’s reputation. It also helped that his son collected and published his father’s papers, wrote a biography, created a research center, and institutionalized memorial lectures that provided those bestowed the honor of giving them an additional occasion to re-engage with Lauterpacht’s work.Footnote 48 But the Function’s rise is also due to factors external to the discipline: Lauterpacht’s causes (judicialization, human rights, international crimes) struck a chord with projects that flourished in the geopolitical landscape of the 1990s–2010s. This, combined with his life story, has made Lauterpacht a “hero” in the field of international law.Footnote 49 Whereas Cory and Ascher, authors of clear and thorough books on some of the same topics as those covered in the Function, have generally disappeared from the international law radar,Footnote 50 the Function has become the symbol of an idea that was initially hardly picked up or appreciated.

II. Lauterpacht’s Victory: The Judicial Train Left the Political Station

While at the time of publication, the Function may have been read as a sustained polemic against predecessors and contemporaries, not so today, when most of Lauterpacht’s doctrinal choices have become dominant legal doctrine. In that sense, the Function has won. Take the political questions doctrine. In the Function, Lauterpacht referred to clauses in arbitration treaties and argued against the then prevalent idea that those disputes that affected the independence, honor, and vital interests of the state were “political” and therefore non-justiciable before international tribunals. Lauterpacht pointed out the problems with this terminology: the concepts legal and political were here used in very different ways than in the social sciences, namely merely as each other’s antonym, with political issues being important issues and legal issues being unimportant ones. Lauterpacht argued that if the concept of legal disputes was instead interpreted to mean those disputes that can be settled by applying legal rules, it would be evident that even the most political disputes could also be legal disputes, especially because in Lauterpacht’s view of international law, there was no non liquet: international law always had an answer.

Almost one hundred years later, the Function’s dismissal of the political questions doctrine is accepted wisdom. The ICJ has echoed Lauterpacht’s arguments in several cases. In contentious cases, it has held that the fact that a dispute has other, non-legal, aspects does not mean that the Court cannot consider it;Footnote 51 that the fact that the legal dispute is only one aspect of a political dispute is not a reason for the Court to decline deciding on the legal questionsFootnote 52 and the resolution of such legal questions may be an important, sometimes decisive, factor in promoting the peaceful settlement of the dispute.Footnote 53 The Court has adopted the same approach with respect to advisory opinions. According to the ICJ Statute, “The Court may give an advisory opinion on any legal question” by an authorized body.Footnote 54 Lauterpacht feared that this formulation with a reference to a legal question would lead to arguments that something was a political question and therefore not appropriate for the Court. And indeed, with respect to several requests for advisory opinions, we have seen states argue just that … but also the Court rejecting it.Footnote 55 In fact, the Court has never refused to give an advisory opinion on the ground that the question posed to it was not a legal question.

The Court has also rejected variations of the political questions doctrine. For instance, in the advisory proceedings on the Occupation of the Palestinian Territories, some states had argued that the Court’s opinion would undermine negotiations between Israel and Palestine and that the Court therefore should exercise its discretion to refrain from giving an opinion. The Court invoked its earlier case law, stating that its opinion would be an additional element in negotiations.Footnote 56 Another variant of the political questions doctrine is the argument that the Court does not have enough factual information or that the matter is too technical for courts to decide on—again an argument made in the Occupation proceedings and dismissed by the Court.

Other courts and tribunals have adopted the ICJ’s—and the Function’s—rejection of the political questions doctrine. The Appeals Chamber of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, for instance, opined in Lauterpachtian terms:

The doctrines of “political questions” and “non-justiciable disputes” are remnants of the reservations of “sovereignty,” “national honor,” etc. in very old arbitration treaties. They have receded from the horizon of contemporary international law, except for the occasional invocation of the “political question” argument before the International Court of Justice in advisory proceedings and, very rarely, in contentious proceedings as well. The Court has consistently rejected this argument as a bar to examining a case.Footnote 57

But it is not just that Lauterpacht’s view on the right answer to the political questions doctrine has prevailed. The legal cosmopolitanism that he espoused in the Function—the international judge as the promoter of world peace—triumphed toward the end of the twentieth century and is, as a disciplinary sensibility, still largely alive and kicking.

Lauterpacht may have paved the way for the Function’s victory by successfully combining continental legal philosophy, more specifically, German Staatslehre, with the common law tradition in international law.Footnote 58 By making the continental tradition speak to Anglo-American scholarship, Lauterpacht provided theoretical grounding for the practice of international lawyers, state practice and a vast amount of case law, mostly emerging from foreign residents making claims against host states based on diplomatic protection. In this way, he fostered a shared legal cosmopolitanism between the two dominant traditions in international law: a faith in legalistic pacificism, a suspicion of sovereignty and a treatment of trade and investment questions as matters of private law, to be protected through individual rights and diplomatic protection.

And so, the Function’s victory enabled not just the judicial train, but also international lawyers and the discipline in general, to purport to have left the political station: its cosmopolitan sensibility allowed international lawyers to engage in legal practice as if not expressing political preferences, for example, when choosing individual rights over sovereignty; commutative justice over distributive justice; judicial settlement over diplomatic negotiations; or when substantive inequalities emerging from foreign investment or economic and trade relations disappeared in the background, out of reach from the critical assessment of the law.

III. The “Fall”: When the Track Is Not Just

The Function triumphed and yet, we also observe its fall. Why? One scenario of its fall could be when the basic conditions for the international rule of law have been eroded and legal cosmopolitanism falls under the weight of political reality: what remains of the rule of law when violations of fundamental norms are no longer confined to the “vanishing point of international law”—Lauterpacht’s words for the law of warFootnote 59—but have become widespread? It is not just the lack of enforcement of the prohibition to use force and the international community’s inaction in front of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes in Gaza, Sudan, Myanmar—anyone remember R2P? It is also that setbacks in the “law of peace” are grinding down the rule of law: a multilateral trade regime without a functioning judicial settlement mechanism; states routinely ignoring non-refoulement obligations, climate commitments watered-down or flouted, and counting. Isn’t this the fall of international law? Given current geopolitics, has the Function not become a relic of the past?

We do not think so. On the one hand, the fall of international law is not new, neither as a geopolitical reality, nor as an idea shaping international lawyers’ disciplinary sensibilities. Cycles of war, collapse of the legal order, followed by institutional and disciplinary renewal are as old as 1648, 1919, 1945—to mention Westphalia, Versailles, and San Francisco, peace treaties that ended wars and inaugurated international orders. Rather than external shocks, these cycles are constitutive to international lawyers’ disciplinary ethos and commitments.Footnote 60 We know that international law and lawyers thrive in crisis.Footnote 61 Then, on the other hand, the question is not which changes in the geopolitical context—whether in 1965, 2003, 2022, or 2023—have pronounced the fall or end of international law, but how the invasions into the Dominican Republic, Iraq, Ukraine, and Gaza have reshaped, if not reinvigorated, disciplinary sensibilities, legal cosmopolitanism included.

The legal cosmopolitanism in the Function might be embattled, but is also largely alive and kicking—think of the hopes and professional excitement expressed by many when South Africa brought a case against Israel for genocide in Gaza to the ICJ,Footnote 62 when the General Assembly requested an advisory opinion on climate change and when the ICJ delivered the opinion,Footnote 63 or when a multiplicity of plans for accountability and reparation were proposed following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.Footnote 64 Thus, given the recurrence of crisis and renewal, today’s cosmopolitan retreat may be only temporary—not a real fall.

When speaking of the “fall” then, we do not refer to the Function’s popularity, but to a collapse of the project of legal cosmopolitanism due to the shaky assumptions on which it is built. That fall may be linked to the current geopolitical cycle of crisis, but is rooted in the assumptions of Lauterpacht’s project of legal cosmopolitanism. The Function assumes that when international lawyers advance legal doctrines and theories embodying the interests of the international community, when courts fulfill the judicial function resolving disputes and authoritatively declaring the content of the law, international law secures peace and justice. As mentioned above, the Function does not extensively theorize,Footnote 65 let alone empirically substantiate, these causal pathways. Nor does it define “peace” or “justice.” Instead, that more adjudication leads to more peace and justice is an assumption that shines through the text. This assumption becomes a postulate affirming the equivalence between the outcome of compulsory adjudication and peace and justice. Lauterpacht links adjudication to peace, for example, when arguing that the prohibition of non liquet follows from the completeness of the rule of law—an a priori assumption:

The first function of the legal organization of the community is the preservation of peace. . . . [T]his primordial duty of the law is abandoned and the reign of force is sanctioned as soon as it is admitted that the law may decline to function by refusing to adjudicate upon a particular claim. (P. 64.)

Lauterpacht reaffirms the link between adjudication and justice, for example, when rejecting the idea that, because of the absence of an international legislator, controversies involving unjust laws should not be resolved through arbitration. According to Lauterpacht, this idea is not only incompatible with the rule law, but also contradictory because justice can be secured only through law: “Even if the view be accepted … that the social ideal is not law, but justice, there still remains the fact that ultimately law is the more effective guarantee of securing that end” (p. 346). And, most famously, insisting that there are no controversies too political or important to be subject to judicial dispute settlement, the Function repeatedly instructs readers to see the link between the judicial function, peace, and justice.Footnote 66

Reaffirming these links, the Function ultimately identifies peace and justice with adjudication. For example, Lauterpacht warns against exaggerating the disadvantages of the absence of an international legislator. Although a legislator may bring the law closer to the demands of change necessary to preserve peace or justice, Lauterpacht defends adjudication, affirming that “[l]aw is more just than loose conceptions of justice and equity” (pp. 250–52). He offers as proof that when international tribunals have been instructed to decide according to equity, they have applied existing law because that solution seemed more just (p. 252). Similarly, confronting the critique that the judicial function must be limited when it is inconsistent with the requirements of justice and peace,Footnote 67 Lauterpacht highlights the impossibility of knowing what these inconsistencies are before an international tribunal takes a decision (pp. 245–47, 258–59). Lauterpacht is as clear about the “gravity” of the implications of this critique, namely, the “rejection of obligatory arbitration,” which means the “rejection of the postulate of the obligatory rule of law,” as he is clear about the fact that when courts decide, there are no fundamental inconsistencies with justice and peace. For the international legal order is a complete system, both formally and materially (p. 259). Formal completeness means that judges are obligated to exercise jurisdiction even in the absence of rules, by filling the gaps in the law. Lauterpacht acknowledges that because of formal completeness there will always be an answer to a legal question, but no guarantee that they will be consistent with justice and the purpose of the law. It is in fulfilling the principle of material completeness, consulting not only the letter of the law, but also its “spirit and purpose,” creatively applying and developing the law, that the judge reaches decisions consistent with justice and the social purpose of the law (pp. 77, 86, 134–35).

To the committed cosmopolitan international lawyer, then, there is only appearance of dissonance, only superficial tensions that can be resolved by working harder to realize the formal and material completeness of the law, by digging deeper into the well of knowledge found in (the correct) court decisions and (proper) scholarship. We argue, however, that the fall is caused by a “functional dissonance” in Lauterpacht’s legal cosmopolitanism, and by extension, the legal cosmopolitanism that still characterizes much of our field today. The assumed causal pathways do not always work. First, contrary to the project’s assumptions, there is no universal agreement over the law’s “spirit and purpose” and therefore over the meaning of the supposedly shared objectives that international adjudication is supposed to deliver. At the time of writing, “peace” for Palestine does not mean the same as what “peace” means for Israel.Footnote 68 Justice does not mean the same in all contexts.Footnote 69 Secondly, there are conflicts over goals: should peace, for instance in the sense of the absence of physical violence, prevail or justice, for instance in the sense of remedying wrongs? In other words, there are disagreements over the directions of travel of the judicial train. And finally, even if there is agreement on goals, the track does not always lead to the promised destination: adjudication does not necessarily lead to peace or justice.

Let us work through some examples of problematic assumptions in the Function. The Function teaches that the self-interested behavior of states justified under sovereignty can be tamed by a legal doctrine—“abuse of rights”—that in contrast to sovereignty reflects the interests of the international community (p. 299). However, a legal doctrine such as abuse of rights need not always expand community interests as the Function predicts, just like sovereignty need not always reflect only states’ narrow self-interest. Lauterpacht explains that in its primitive stage, international law is an individualistic system, devoted to recognizing the rights of states, its main subjects, and thus a system limited to preventing violence and maintaining peace.Footnote 70 But “with the growth of civilization and of the social integration of the community,” international law, based on justice, solidarity, and the common interest, regulates and limits states’ freedom of action (id.). For Lauterpacht, there is no reason to keep international law as an individualistic system and halt the progress of law toward a more advanced stage. According to Lauterpacht, the doctrine of abuse of rights enables this progress and the realization of common interests by limiting the anti-social use of rights.Footnote 71 However, a problem emerges when it is understood that a more advanced international law enhances justice, solidarity, and the common interests, assuming rather than defining what these goals are. The problem is that without careful deliberation, through diplomatic dialogue and negotiations, conflicts over the specific meaning of these goals are overlooked; so that the concrete interest, of a particular state, or individual, most likely a powerful state or individual, is translated as the larger and abstract interest of the international community.

Moreover, Lauterpacht’s arguments in support of the doctrine of abuse of rights illustrate the weak foundations of some of the assumed causal pathways. The function of this doctrine is, so Lauterpacht argues, “one of resort to a comprehensive legal principle of social justice and solidarity calculated to render inoperative unscrupulous appeals to legal rights endangering the peace of the community” (p. 306). But for that doctrine to be properly applied, it is necessary for courts to have compulsory jurisdiction. “Failing such compulsory jurisdiction, selfish claims of State sovereignty have a tendency to assert themselves in short-sighted and petulant manner in disregard of the purpose of the law and of the interests of peace” (id.). Throughout the text, he presents sovereignty as the opposite of community interests. For example, when Lauterpacht presents instances in which the exercise of state sovereignty is limited by the doctrine of abuse of rights, he assumes that states that exercise sovereignty selfishly pursue their own interest, for instance, when they regulate nationality, use their territory and create extraterritorial impacts, when they claim exclusive use of their airspace and when they deal with foreign residents. On the other hand, Lauterpacht assumes that it is in the international community’s interest to limit that sovereignty. However, in these instances, limiting sovereignty may or may not be in the interests of the international community. For instance, the arguments for the “freedoms of the air” are echoes of Grotius’s arguments for a mare liberum: anti-sovereignty, but not necessarily always in the interests of the international community. Consider the tension between freedom of the seas and the protection of marine resources beyond national jurisdiction, or the unequal use of airspace and global commons such as the high seas, the atmosphere and outer space. Although international law guarantees all states access to these spaces, the most developed and technologically advanced countries reap the greatest benefits, without any redistributive mechanism. Thus, in practice, the real tension may not be interests of the state versus interests of the international community, but interests of one state versus the interests of another state, which presents its interests as those of the international community. For example, the Function assumes that the protection of alien residents and their property are community interests, whereas the interests to regulate foreign investment in capital-importing states of the peripheries are selfish interests of particular states. But the interests of foreign residents are also the interests of the state of the foreign residents’ nationality, not only economically or politically, but also legally, as these states exercise diplomatic protection. In this case, the interests of certain states, capital-exporting states, are assumed to be the interests of the international community. But a case could equally be made that it was in the interests of the international community that after decolonization, newly independent states invoked their sovereignty to take control of the natural resources that colonial authorities had given away to foreign investors. And today, that protecting Ukraine’s sovereignty against Russian aggression is in the international community’s interests. By considering sovereignty as the opposite of legal cosmopolitanism, Lauterpacht’s sensibility—now a dominant sensibility in the field—makes it difficult for international lawyers to untangle the assumed nexus between legal cosmopolitanism and community interest and between sovereignty and the self-interest of states. This may be why it is hard for them to recognize that in most controversies there are legal cosmopolitan and sovereignty-based arguments as well as community and state interests on both sides.

These difficulties have several practical effects. Some states find it easier than others to express their interests in the language of legal cosmopolitanism. For states that rely more on arguments based on sovereignty, their international lawyers must overcome the discipline’s cosmopolitan bias. We may recognize an even more serious practical consequences resulting from the assumption that certain doctrines promote the collective interest (abuse of rights), and others do not (sovereignty), when, for example, Lauterpacht writes that abuse of rights, with the force of the law, justifies disavowing sovereignty:

A large part of the law of intervention is built upon the principle that obvious abuse of rights of internal sovereignty, in disregard of the obligations to foreign States and fundamental duties of humanity in relation to the State’s own population, constitutes a good legal ground for dictatorial interference. (P. 287.)

The idea that abuse of rights lies at the basis of the law of intervention—the international law that regulates the use of military force to collect public debt, exercise diplomatic protection or enforce compensation for injury to foreign residents and their property—would not have come as a surprise to many of Lauterpacht’s contemporaries.Footnote 72 The irony is that the year in which the Function was published also saw the signing of the 1933 Montevideo Convention, which, by sanctioning sovereign equality and non-intervention, marked the beginning of the end of the legal use of force in the law of intervention.Footnote 73 While Lauterpacht’s Anglo-American and continental European audience might not have noticed any dissonance, the idea that the function of abuse of rights is limiting sovereignty to secure community interests would have sounded off to semi-peripheral international lawyers and especially to Latin Americans. Whereas for Lauterpacht intervention on the ground of abuse of rights was the correct avenue for international law to promote peace and justice, for Latin Americans Montevideo was the culmination of a decades-long, hard-fought legal and diplomatic battle to advance international law through the expansion of sovereignty. Unlike for Lauterpacht, for the Latin American, it is by recognizing non-intervention as a corollary of sovereignty that international law promotes peace and justice.Footnote 74 They agreed on the outcomes; not the functional logics.

Lauterpacht’s assumption that international law as applied by international judges produces by definition fairer outcomes than those produced, for example, by diplomatic negotiations, may have created dissonance also for other international lawyers from the peripheries. Imagine a Chinese audience reading Lauterpacht’s treatment of unequal treaties—without him ever calling them such (pp. 199–201, 283, 326–27). In 1865, having been coerced into opening up to foreign trade, China signed an unequal treaty with Belgium. In 1926, the Chinese government, assisted by international lawyers of the stature of Wellington Koo, invoked rebus sic stantibus to unilaterally denounce the unequal treaty and renegotiate legal relations respecting the juridical equality of both nations. To the Chinese, there must have been no doubt about the unfairness of unequal treaties and of the standard of civilization justifying them, and the specific clauses providing Belgium with extraterritorial rights and consular jurisdiction, while limiting China’s power to impose tariffs. Lauterpacht, in contrast, looks at unequal treaties simply as treaties and at China’s denunciation as a juridical controversy with Belgium;Footnote 75 and thus, the Function assesses the matter through the lenses of its own assumption that correct legal doctrine and compulsory adjudication will lead to the respect of international law and to a just outcome. While an audience sensitive to the histories of international law in places such as China would see rebus sic stantibus and non-justiciability of political questions (enabling a political renegotiation of the unequal treaty) as the articulation of international legal doctrine toward peace and justice, Lauterpacht sees things differently. The Sino-Belgian controversy appears in the Function in a section where the main issue is the optional clause conferring compulsory jurisdiction over legal disputes to the Permanent Court of International Justice, and its potential limitation in relation to political disputes. The Chinese government refused to accept the Belgian proposal to submit the dispute over the interpretation of the clause regulating the renewal of the treaty to the Permanent Court. As Lauterpacht explains, China understood the controversy to be about the principle of equality between states and thus of a political, not legal character.Footnote 76 Given that Belgium withdrew the case, Lauterpacht is left to ponder, believing that the Court would not have recognized the objection’s validity, and concluding that the only case in which the optional clause was invoked reveals: “the cloven hoof of the doctrine of the elimination of important issues from the obligatory jurisdiction of international tribunals” (p. 200). The Sino-Belgian controversy reemerges in other sections of the Function, regarding rebus sic stantibus and tribunals deciding ex aequo et bono. Once again, Lauterpacht’s main concern is not the Chinese struggle to overcome unequal treaties, but rather the underlying doctrinal issue. In the section on ex aequo et bono, Lauterpacht notes that, by statute, the Permanent Court is entitled to decide cases based on equity. Defending the doctrine against critics, he discusses the Chinese proposal to request, jointly with Belgium, that the Permanent Court decide the controversy ex aequo et bono. In this case, Lauterpacht seems to be sympathetic to such a proposal. But then, his sympathy lies not with the Chinese struggle to abrogate unequal treaties, but with ex aequo et bono as a doctrine enabling legal change and with the judicial function as an instrument of peace.Footnote 77 As a matter of fact, ultimately Chinese international lawyers succeeded in abrogating the unequal treaty with Belgium, not through an ex aequo et bono decision of the Permanent Court, but through a renegotiation based on a unilateral denunciation justified under rebus sic stantibus.

The problem with the type of cosmopolitan legalism advocated by Lauterpacht is that the link between the judicial settlement of disputes and peace is not a hypothesis subject to critical examination, but a credo, a theoretical postulate, “a metaphor … for the unity of the legal system.”Footnote 78 Since the connection between international law, peace and justice is a theoretical postulate, its failure to hold true in practice is irrelevant to legal cosmopolitanism as a theory.Footnote 79 But that failure is not irrelevant to legal cosmopolitanism as a disciplinary practice. For us, then, the “fall” of the Function lies in it having become evident that its functional assumptions do not (always) hold in fact. The faith in the project of the judicialization of politics may not have collapsed, but the reasons to query that faith have become very apparent: while international lawyers celebrate the ICJ’s new spring, thousands and thousands are dying. It becomes harder and harder to ignore the functional dissonance.Footnote 80

IV. Conclusion

Unlike Helen May Cory’s and Annemarie Ascher’s works, Lauterpacht’s Function has become one of the best-known books in the canon of international law (though not necessarily one of the best read). It is understandable why the AJIL editors suggested (re-)reading that book in today’s times. Lauterpacht wrote at a time of crisis. (He himself did not write much in the book about that crisis; it is Koskenniemi who has situated the book in a time of crisis.) In that time of crisis, Lauterpacht presented the international judge as the only hope for world peace. For Lauterpacht, international law was not a collection of rules. It was a system, with the international judge as the foundation of the rule of law. Today, too, there is much talk of crisis. Going back to the Function means going back to a book that presents international lawyers as the answer to crises, potentially also today’s. Revisiting the Function today then is revisiting the idea that international lawyers offer hope, the only hope, in a world in which the rule of law seems under threat. However, while Lauterpacht’s doctrines have been accepted, the crisis is still, or again, there. That is because his solution, that of believing in the international judge as the foundation of the international rule of law, was never the only answer to the underlying question of how international law can lead to justice and peace.

Figure 1: Google N-gram showing references to the “Function of Law in the International Community” in books published between 1800 and 2022 and digitized by Google Books.