1 Introduction: Peripheral Growth Models and Economic Development

Few debates in development studies are as contentious as the one over the sources of development and growth. A wide range of competing growth theories is available – both neoclassical and heterodox (see Jones & Vollrath, Reference Jones and Vollrath2013; Aghion & Howitt, Reference Aghion and Howitt2009 for the former, and Hein, Reference Hein2014; Blecker & Setterfield, Reference Blecker and Setterfield2019 for the latter). Yet, the fact that only a small number of economies have successfully caught up with advanced countries since the second half of the twentieth century has only intensified the growth debate, especially in light of rising global inequalities since the 1980s and the stagnation of once rapidly growing late developers (Johnson & Papageorgiou, Reference Johnson and Papageorgiou2020). This discussion is particularly critical for peripheral economies, where challenges such as absolute poverty, lack of social safety nets, health crises, and – increasingly – climate vulnerability are sorely felt. In response, a range of scholarly approaches have tried to shed new light on the enduring questions of growth and development in global capitalism (e.g., Banerjee & Duflo, Reference Banerjee and Duflo2019; Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2023; Sen, Reference Sen2023; Rodrik & Stiglitz, Reference Rodrik and Joseph2024; Acemoglu, Reference Acemoglu2025; Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2025).

In recent decades, the debate on the political economy of development has arguably been shaped by the grand theories of new institutional economics and the developmental state (Acemoglu & Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; Haggard, Reference Haggard2018; see Section 2.1). Both focus on the necessary conditions for the successful transition to a high-income economy, deriving insights about this process from a few selected countries that achieved this goal. The debate has too often focused on individual “role models” for catch-up development – most notably South Korea – (see, e.g., Lee, Reference Lee2013), tending to downplay the structural conditions of the vast majority of developing and emerging economies that need to get into a growth-enabling phase in the first place. While we are far from denying the importance of institutions and state bureaucracies for economic and political development, this Element proposes a different perspective for the study of growth trajectories in so-called emerging economies such as Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa, Thailand, or Turkey. Starting from the observation that growth in these economies mostly occurs in episodes that are characterized by volatility, shaped by pronounced boom-bust cycles and sustained phases of stagnation (Pritchett et al., Reference Pritchett, Sen and Werker2017), we introduce the growth model perspective to development studies. We contend that this middle-range theory helps explain why some countries succeed in pursuing sustained periods of economic growth and stabilizing a highly volatile growth trajectory, while others fail and experience major crises and periods of stagnation. Thus, our claim is rather narrow: Instead of projecting long-term catch-up development to high-income status, the approach proposed here allows for examining growth dynamics in a shorter time frame, accounting for incremental changes in varying growth trajectories.

Developed simultaneously in post-Keynesian economics (PKE) and comparative political economy (CPE), the growth model perspective analyzes advanced capitalist economies by unpacking their aggregate demand composition and respective political underpinnings (e.g., Baccaro & Pontusson, Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016, Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2018; Hein et al., Reference Hein, Paternesi Meloni and Tridico2021; Hassel & Palier, Reference Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021; Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer2022; Kohler & Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer2022; Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Blyth and Pontusson2022). Growth models in these research traditions are understood through an empirical-historical lens, aiming to establish Weberian ideal types to allow for context-sensitive, mid-level theorizing on the similarities and differences of capitalist economies and their trajectories of expansion, stagnation, crisis, and change. More specifically, Baccaro and Pontusson (Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016) traced the emergence of two interdependent types of growth models in countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): a consumption-led growth model, partly bolstering domestic demand through household debt, and an export-led growth model, replacing domestic with external demand. Their intervention triggered an ongoing debate about the relative importance of demand-side and supply-side factors for growth (see Hope & Soskice, Reference Hope and Soskice2016; Hassel & Palier, Reference Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021; Schedelik et al., Reference Schedelik, Nölke, Mertens and May2021; Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer2022), reflecting a renewed interest among political economists in macroeconomics and its relation to politics (Amable et al., Reference Amable, Regan and Avdagic2019; Baccaro & Pontusson, Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2018; Blyth & Matthijs, Reference Blyth and Matthijs2017; Schwartz & Tranøy, Reference Schwartz and Tranøy2019). Subsequently, the growth model (GM) perspective has been used to explain international economic imbalances (e.g., De Ville & Vermeiren, Reference De Ville and Vermeiren2016; Johnston & Regan, Reference Johnston and Regan2016; Hall, Reference Hall2018; Akcay et al., Reference Akcay, Hein and Jungmann2022) and to map out the variety of growth models in advanced capitalist economies (Hein et al., Reference Hein, Paternesi Meloni and Tridico2021; Picot, Reference Picot, Hassel and Palier2021).

By introducing the growth model perspective to the broader field of development studies and applying the perspective to peripheral economies in global capitalism, this Element pursues two major goals. The first goal is to instigate a conversation between different research communities, in order to advance the debate on the sources and politics of development and growth (Acemoglu & Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; Pritchett et al., Reference Pritchett, Sen and Werker2017; Kelsall et al., Reference Kelsall, Schulz and Ferguson2022; Behuria, Reference Behuria2025). While the GM perspective is most vibrantly debated in CPE, an established interdisciplinary literature rooted in political science, sociology, and (heterodox) economics, broader questions of development and change – especially in non-OECD countries – are usually dealt with in the cross-disciplinary field of development studies. Despite occasional interactions in the past (e.g., Evans & Stephens, Reference Evans and Stephens1988), there are few interactions or conceptual overlaps found today. We believe that this separation has produced shortcomings. Among them is the tendency in development economics to emphasize stylized universal growth trajectories that every country will eventually follow, as was already common in, for example, Lewis (Reference Lewis1954) or Rostow (Reference Rostow1960). The basic assumption in this latter tradition holds that countries can be treated symmetrically and that their long-term growth trajectories follow more or less the same patterns (but see Sen Reference Sen2023 for an accommodating approach). In neo-institutionalist economics, the precondition to achieve higher rates of economic growth is strong institutions, associated with property rights, the rule of law, and liberal democracy. The developmental state approach sees state capacity as the main solution for the intricate problems of growth. The literature in CPE has rejected such perspectives and, by contrast, focuses on the persistent divergence of development paths and major differences in policy responses to external shocks. It seeks to explain these differences with the help of typological theories of capitalist economies (Clift, Reference Clift2021; May et al., Reference May, Nölke and Schedelik2024) and emphasizes diverse, uneven, and interdependent growth trajectories in a global economy. Leveraging the typological approach common in CPE, we believe, can help move beyond a one-size-fits-all perspective and provide new ground for conversation. In other words, having this conversation may contribute to understanding some of the enduring and intricate puzzles of development studies, especially why some countries thrive within imperfect economic and institutional conditions.

The second goal this Element pursues is to advance the growth model perspective in CPE itself, by adapting its concepts to countries beyond the well-studied hemisphere of OECD economies. Moving beyond the existing geographical confines of the GM perspective means exploring its applicability to so-called emerging capitalist economies (ECEs). ECEs are conventionally understood as countries transitioning from low-income, low-productivity economies with informal institutions toward higher-income economies, with expanding domestic markets and an accommodating set of institutions in financial systems, property rights, and industrial organization. Brazil, China, Mexico, Thailand, and Turkey are just a few of the countries in this heterogeneous group. The term emerging capitalist economies has become standard in the field, so we adhere to this convention. However, this does not imply agreement with the implicit normative assumption that every ECE will inevitably grow and develop – emerge – by further integrating into the global economy and strengthening capitalist institutions. On the contrary, instances of earlier successful catch-up are relatively rare. Many ECEs tend to experience severe growth slowdowns and periods of stagnation. In fact, as we argue in this Element, the particular way in which many ECEs are integrated into the global economy makes their development trajectories especially vulnerable to the whims of international capital. We therefore analyze their growth trajectories in terms of peripheral growth models, based on a recent cross-fertilization between the GM perspective and dependency approaches (Madariaga & Palestini, Reference Madariaga and Palestini2021; Schedelik et al., Reference Schedelik, Nölke, Mertens and May2021, Reference Schedelik, Nölke, May and Gomes2023; Avlijas & Gartzou-Katsouyanni, Reference Avlijaš and Gartzou-Katsouyanni2024, Reference Avlijaš, Gartzou-Katsouyanni and Regini2025; Bulfone et al., Reference Bulfone, Madariaga and Tassinari2025). One important advantage of this cross-fertilization is that it bases the study of economic growth in part on a perspective born from the periphery, thereby challenging the usual application of models developed in and for the global North to the global South. Moreover, economic dependencies today are not only pronounced in North-South relationships but also increasingly matter in relations between China and other countries of the South (Stallings, Reference Stallings2022). Finally, the combination of the GM perspective with dependency approaches also addresses a typical problem inherent in contemporary versions of the latter, such as the discussion on international financial subordination (Kvangraven et al., Reference Kvangraven, Koddenbrock and Sylla2021; Alami et al., Reference Alami, Alves and Bonizzi2023). Such a combination assists in balancing the structuralist bias of dependency theory with the potential for economic agency highlighted by the GM perspective (Petry & Nölke, Reference Petry, Nölke, Petry and Nölke2025; Schedelik & Nölke, Reference Schedelik and Nölke2025).

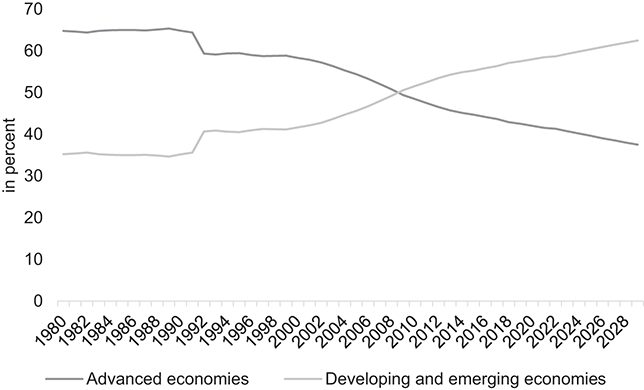

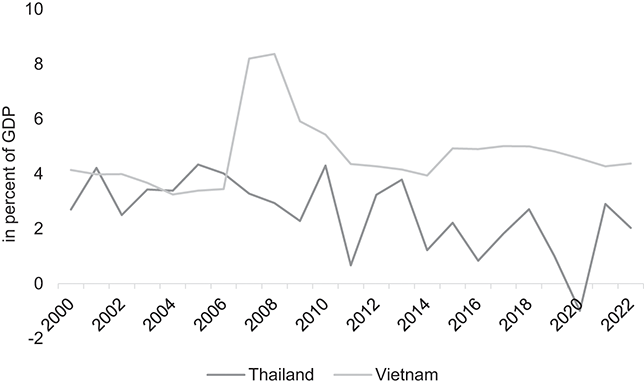

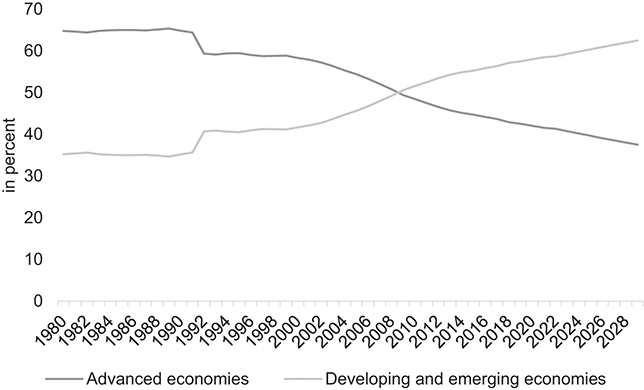

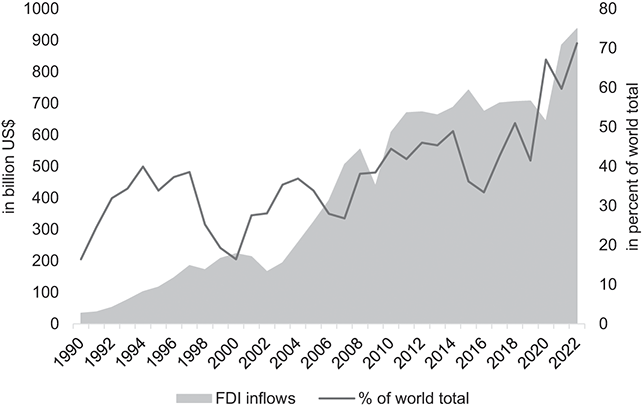

From our point of view, it is overdue to extend the GM perspective to this group of countries. After all, an approach centered on “growth” should provide meaningful insights about actually growing economies, which are increasingly to be found outside of the OECD. This shift in the global distribution of economic growth started in the early 1990s and is often attributed to the rise of China and the BRICSFootnote 1 on the one hand and the exhaustion of the postwar growth regime in the “West” on the other (Blyth & Matthjis, Reference Blyth and Matthijs2017). Consequently, the center of growth in the global economy has moved in the last decades: Around 2008, for the first time, more than half of global GDP was accounted for by developing and emerging economies (Figure 1).

Figure 1 GDP based on purchasing power parity (PPP), share of world GDP, 1980–2028

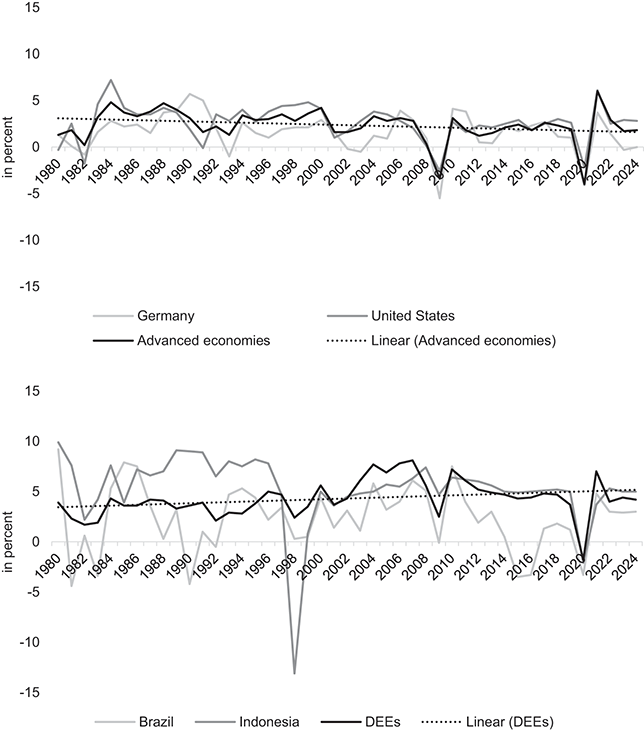

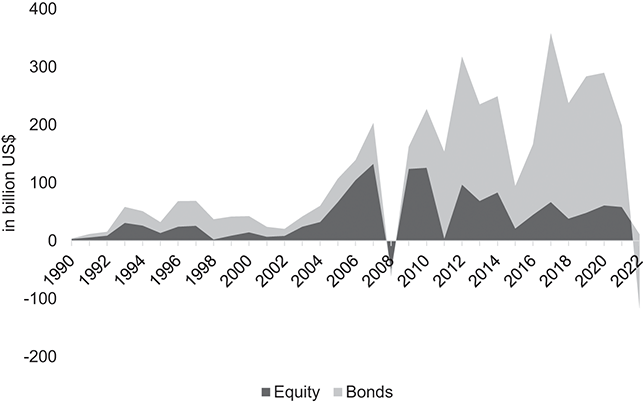

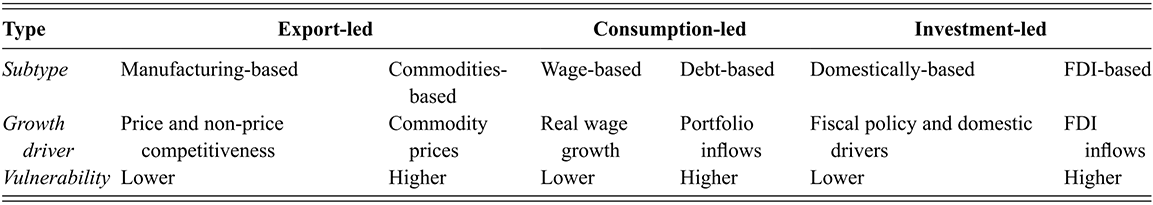

Overall, however, growth trajectories of developing and emerging economies are significantly different from those of advanced economies. Whereas the latter typically are characterized by a relatively stable long-run average growth rate, the former are characterized by higher volatility. This manifests itself in a stop-and-go pattern of growth, that is, sudden shifts between growth accelerations, slowdowns, and even outright collapses (Jones & Olken, Reference Jones and Olken2008; Kar et al., Reference Kar, Pritchett, Raihan and Sen2013). Hence, peripheral growth models in ECEs tend to show higher degrees of vulnerability, defined traditionally as “the exposure to external shocks” (Briguglio et al., Reference Briguglio, Cordina, Farrugia and Vella2009, 229; see Figure 2). A large part of this vulnerability stems from the external sector of these economies and relates to volatile export revenues, typically in a handful of commodities, as well as volatile capital flows, both portfolio and foreign direct investment flows. While these factors on their own are well researched, they are not yet integrated into an encompassing theoretical framework of growth. By advancing the GM perspective for the study of emerging economies, we aim to provide such a framework.

Figure 2 Annual real GDP growth of selected countries and country aggregatesFootnote 2

Our framework to study peripheral growth models builds on three pillars: (1) a novel and coherent typology of growth models in emerging economies, which highlights (2) different modes of integration into global economic structures and processes that lead to varying degrees of macroeconomic vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities, in turn, can potentially be mitigated by (3) economic policies, broad political coalitions, and coordinated state-business relations that are specific to the political economy of peripheral growth models – and which are often better understood by scholars of development. Here again, by adapting the toolbox of growth model research to ECEs, we hope to spark greater cross-disciplinary and global engagement.

Against this backdrop, this Element is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the main theoretical approaches to economic growth and development in various literatures in political economy and development studies. Based on this discussion, we introduce our own analytical framework for the study of peripheral growth models and present the methodological approach used in this Element. Section 3 proposes a typology of peripheral growth models and employs national accounts data to identify growth models in large ECEs over the past twenty years. Based on this descriptive dataset, it elaborates on the relevance and vulnerabilities of an “investment-led growth model,” which has so far received insufficient attention in the GM perspective. The section then lays out the small-N case universe from which we draw subsequent illustrative vignettes. Section 4 highlights how peripheral growth models are shaped through international interdependencies by analyzing the effects of global commodity cycles on the growth experience of several major exporters of primary resources, exemplified by Brazil and Indonesia, during and after the recent commodity boom. We further elaborate on the effects of global financial cycles on emerging countries, particularly those pursuing debt-based growth models, such as South Africa and Turkey. We finally point to the role of global value chains (GVCs) and foreign direct investment (FDI) for the investment-led growth models of countries such as Thailand and Vietnam in Southeast Asia. Subsequently, Section 5 analyzes the interaction of growth models and political dynamics in non-Western political settings by reflecting on the political support for growth models of selected emerging economies. Lastly, Section 6 concludes with a summary of the results, discussing the policy implications and future research avenues for the GM perspective in particular and the political economy of development more broadly.

2 Theory and Framework

In this section, we first review several theoretical approaches to economic development at the intersection of political science, sociology, and economics. Highlighting strengths and weaknesses of these perspectives, we argue for moving beyond the established fault lines in the development discourse. We do this by advancing the growth model perspective in CPE for the study of growth trajectories in emerging economies. Therefore, we subsequently introduce the main theoretical debate in CPE between the varieties of capitalism (VoC) approach and the GM perspective, arguing for an accommodating approach. We then propose our conceptual framework of peripheral growth models, which builds on but significantly extends traditional GM analyses. Finally, we discuss the case selection and research design for the empirical sections of this Element.

2.1 Political Economy Approaches to Economic Development

The neo-institutionalist literature in economics has revived the debate about the causes of (under)development (North, Reference North, Harris, Hunter and Lewis1995; Greif, Reference Greif2006; Acemoglu & Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012). This approach contends that strong institutions tend to achieve higher rates of economic development because these institutions provide the necessary incentives for investment, innovation, human capital accumulation, and economic exchange. By now, there is an established consensus that “institutions matter” for long-term growth (Rodrik et al., Reference Rodrik, Subramanian and Trebbi2004; Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson, Aghion and Durlauf2005). Though disagreement persists over what the best institutional design looks like, the dominant view has it that liberal political and economic institutions trump all other arrangements. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson have advanced this perspective in their account on “why nations fail” (Acemoglu & Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012). According to them, “inclusive” political and economic institutions associated with free markets, property rights, the rule of law, and pluralist democracy are prerequisites for economic growth. “Extractive” institutions divert resources away from their most efficient and socially optimal use by powerful elites. In a nutshell, Acemoglu and Robinson’s approach arguably proposes one universally applicable model for development: The liberal market economy, which is enforced and sustained by liberal democracy, thereby disavowing or even denying indigenous institutional constellations (Madra et al., Reference Madra, Bengi and Adaman2025, 7–8).

The neo-institutionalist approach has encountered severe criticism, however. To begin with, the dichotomy of inclusive and exclusive institutions is too simple to capture the real-world variety of institutional arrangements, their historical origins, and embeddedness in a hierarchically structured, globalized economy (Chang, Reference Chang2011; Ince, Reference Ince2024). Furthermore, this perspective, focusing on long-run growth rates, fails to explain the volatile growth episodes so prevalent in emerging economies (Pritchett et al., Reference Pritchett, Sen and Werker2017, 12). Finally, such a perspective cannot explain why many countries industrialized under authoritarian rule with heavy state intervention – the most obvious contemporary examples being East Asian “developmental states” and, more recently, China (Sen et al., Reference Sen, Pritchett, Kar and Raihan2018; ten Brink, Reference ten Brink2019). At the very least, an endorsement of these facts calls for more nuanced, context-sensitive institutional analyses devoted to mid-level theorizing (Merton, Reference Merton1968), rejecting universally valid one-size-fits-all accounts.

The developmental state literature mentioned earlier is one major example of a deep engagement with country case studies and comparative historical analysis (Johnson, Reference Johnson1982; Amsden, Reference Amsden1989; Wade, Reference Wade1990; Evans, Reference Evans1995). Primarily occupied with explaining the growth miracles of first- and second-tier East Asian late industrializers, this literature has informed a broad and lively debate about the role of the state in economic development (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2009; Stiglitz & Lin, Reference Stiglitz and Lin2013). After the 2008 financial crisis, this discussion has gained considerable momentum even in OECD countries (Mazzucato, Reference Mazzucato2013; Breznitz & Gingrich, Reference Breznitz and Gingrich2025). However, given the peculiarities of the East Asian developmental states and the specific external conditions permissive of their export-led growth models (Haggard, Reference Holland2019, 54–9), Johnson (Reference Johnson1982, 307) warned early on: “the dangers of institutional abstraction are as great as the potential advantages” of adopting Japan’s growth strategy in other contexts. Hence, the “quest for capacious and strategically oriented state institutions has ultimately proved elusive,” as only a handful of countries have achieved such a high degree of state capacity (Naseemullah, Reference Naseemullah2023, 7). Over time, the notion of developmental state has become a rather abstract buzzword detached from its origins and main conceptual elements (Fine, Reference Fine, Fine, Saraswati and Tavasci2013). Accordingly, the debate has shifted toward new directions, such as the question of whether a capacious state bureaucracy is possible at all in times of financialization and neoliberalism (Evans & Heller, Reference Evans, Heller, Leibfried, Huber, Lange, Levy and Stephens2015; Fine & Pollen, Reference Fine, Pollen, Fagan and Munck2018).

Hence, both neo-institutionalist and developmental state approaches tend to imply a (normative) linear model of development, which countries would only need to apply fully in order to achieve high levels of economic growth. Furthermore, development is treated as a purely domestic process, which, in our view, underestimates the structural conditions of the global political economy. Both approaches usually highlight the flaws of development in different countries, as the record of successful adopters of either model is quite small. In particular, Korea and Taiwan are seen as role models for development, successfully transitioning from a low- to high-income status in the twentieth century. However, these cases are economies with particular geopolitical and historical-institutional legacies, making it hard to generalize their developmental state model globally (Naseemullah, Reference Naseemullah2023). In addition, these countries recorded robust export growth throughout a large part of their development trajectory, highlighting the particular global economic conditions of the second half of the twentieth century in which they could grow through such a model. These structural conditions of the global political economy, so we contend, have changed in such a fundamental way that it is impossible to directly compare the growth trajectories of the 1960s and 1970s with those of the 2000s and onward.

This argument has also been highlighted by approaches that explain growth and development exogenously, locating the sources of and conditions for (under)development at the level of the global political economy. Drawing on dependency theory, world systems, postcolonial, and other critical approaches (e.g., Cardoso & Faletto, Reference Cardoso and Faletto1979; Wallerstein, Reference Wallerstein1976), this important strand of research investigates the hierarchical structure of the global economy and its constraining impact on economic development in peripheral countries. Contemporary versions of this argument underline three aspects of today’s global capitalism: global commodity markets, financial flow cycles, and global production networks. Studies on global commodity markets highlight the dependence of many developing and emerging economies on exporting commodities. These dependencies are profound, given the cyclical nature of commodity price movements over time (Akyüz, Reference Akyüz2022; Schedelik et al., Reference Schedelik, Nölke, May and Gomes2023). Similarly, scholars working on “dependent” or “subordinate” financialization highlight the severe repercussions of short-term financial flows on these economies (Bonizzi et al., Reference Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner and Powell2022; Lapavitsas & Soydan, Reference Lapavitsas and Soydan2022). Finally, the literature on global production networks argues that developing countries often are integrated in a subordinate position in these networks, being responsible for low-tech production, low-skills employment, harsh working conditions, and profound pollution (Wang et al., Reference Wang, He and Song2021). In all of these regards, the fate of peripheral economies is perceived as more or less determined by the overwhelming forces of the global economy, leaving little room for economic agency (Petry & Nölke, Reference Petry, Nölke, Petry and Nölke2025; Schedelik & Nölke, Reference Schedelik and Nölke2025; on this see also Avlijaš & Gartzou-Katsouyanni, Reference Avlijaš and Gartzou-Katsouyanni2024, Reference Avlijaš, Gartzou-Katsouyanni and Regini2025).

All exogenous–focused approaches arguably suffer from an underestimation of domestic politics beyond elites and state bureaucracies. This shortcoming has been addressed by the political settlements analysis approach (Khan, Reference Khan, Khan and Jomo2000, Reference Khan2010). It emphasizes how the distribution of power in society, including formal institutions but also informal networks and patron-client relations, can support or thwart developmental goals. Particularly in developing economies, where the economic structure is dominated by primary commodities, there is a need to promote economic diversification and technological upgrading. Contrary to the dominant neo-institutionalist view, certain types of rents can contribute positively to development. In this context, rents are broadly understood as “excess incomes, which do not exist in perfect markets” (Khan, Reference Khan, Khan and Jomo2000, 21). “Rents for learning” and “Schumpeterian rents,” which are necessary for the promotion of economic diversification, indigenous technological capabilities, and innovation, do not necessarily equate with waste and inefficiencies. As long as the distribution of power allows those rents to be used productively, state capture can be avoided. Traditionally, the political settlements literature lends itself to detailed country case studies, but recent endeavors have also tried to build a more quantitative approach (Kelsall et al., Reference Kelsall, Schulz and Ferguson2022; for a recent review, see Behuria, Reference Behuria2025).

By employing the growth model approach for developing and emerging economies, we aim to offer an alternative route mediating between the grand theories of neo-institutionalism, developmental state, and dependency. The growth model perspective is both more pragmatic and realist: It is pragmatic because it accounts for the incremental improvements of growth-enabling institutions and policies, knowing that hardly any country can “imitate” the trajectories of Korea, Taiwan, or – nowadays – China. It is realist in the sense that it treats development conditions as they are, not as they should be. Crucially, this entails that the task of development is first and foremost to minimize vulnerability, which is the major factor for stagnant or negative growth in the first place.

To summarize, existing political economy approaches to economic development have considerable strengths, but also major shortcomings. Regarding the latter, a preference for universally valid one-size-fits-all accounts seems to be the most prominent one. This is not only a problem for large parts of the neo-institutionalist literature, but also for part of the developmental state discussion, which tends to abstract from the particular circumstances of the East Asian cases during the mid twentieth century. Moreover, the recent rejuvenation of dependency approaches thus far tends to underplay the economic agency of emerging economies. Against this backdrop, typological approaches in CPE have the potential to complement existing perspectives on development by highlighting opportunities for macroeconomic agency in a context-sensitive way.

2.2 Approaches in Comparative Political Economy: Varieties of Capitalism and Growth Models

In contrast to the neo-institutionalist focus on a narrow set of institutions (e.g., property rights and the rule of law), CPE approaches build on a much richer set of socioeconomic institutions that account for the multidimensionality of growth trajectories. Along with regulation theory and the national business systems approach, particularly the VoC paradigm has been a key reference point in the CPE literature. This scholarship generally assumes that country-specific institutions matter for economic performance and that different institutional configurations are conducive to achieving economic and social objectives. Institutions are understood in a pragmatic way as solutions for coordination problems of firms. More specifically, it argues that key institutional spheres (such as corporate governance, financial system, industrial relations, or education and training), the identification of cross-cutting coordination mechanisms (inter-firm networks and associations versus competitive markets and formal contracts), as well as the notion of (positive) complementarities among institutions, allow for a parsimonious analysis of capitalist systems.

Crucially, VoC scholarship introduced ideal types of capitalist economies as analytical tools. Drawing on a long-established research tradition (Shonfield, Reference Shonfield1965; Streeck, Reference Streeck2010, 6–15), Peter Hall and David Soskice made the now-classical distinction between liberal market economies and coordinated market economies (Hall & Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001, 8). In the former, firms coordinate themselves primarily through competitive markets and formal contracts, whereas in the latter, they rely principally on inter-firm networks and associations. In contrast to the convergence thesis predominant in the 1990s, claiming that all capitalist economies would adapt themselves to the “superior” Anglo-Saxon model (Streeck Reference Streeck2010, 15–7), VoC argues that both types can be economically successful and internationally competitive, even in the long run. This idea rests on Hall and Soskice’s notion of “comparative institutional advantage,” which states that “the institutional structure of a particular political economy provides firms with advantages for engaging in specific types of activities there” (Hall & Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001, 37). As it does not focus on absolute, but comparative institutional advantages of nations, it is able to account for cross-national variation in product specialization.

Recent research has extended the VoC perspective, identifying four main types of emerging market capitalism (Schedelik et al., Reference Schedelik, Nölke, Mertens and May2021; Friel, Reference Friel2024): (1) a dependent market economy, originally envisaged for Central and Eastern Europe (Nölke & Vliegenthart, Reference Nölke and Vliegenthart2009); (2) a hierarchical market economy, modelled after Latin American economies (Schneider, Reference Schneider2013), but also identified in Turkey (Kiran, Reference Kiran2018); (3) a state-permeated market economy, found in East Asia (Carney, Reference Carney2016), China (ten Brink, Reference ten Brink2019), India and temporarily in Brazil (Nölke et al., Reference Nölke, ten Brink, May and Claar2020); and (4) a patrimonial market economy (Becker, Reference Becker2013), as depicted for the Arab world (Schlumberger, Reference Schlumberger2008) as well as for Russia and other former Soviet countries (Becker & Vasileva, Reference Becker and Vasileva2017). Focusing on supply-side institutions and firm characteristics, the VoC research program, however, has largely tended to ignore three major points: demand-side macroeconomics, (distributive) politics, and a country’s insertion in the global economy.Footnote 3 These points relate to the source and composition of economic growth (both domestic and external) as well as its stability through (domestic) political support and international factors such as financial flows or commodity price movements (Nölke et al., Reference Nölke, May, Mertens and Schedelik2022; Schedelik et al., Reference Schedelik, Nölke, May and Gomes2023). Since growth trajectories in emerging economies are more vulnerable and volatile than in advanced ones, these points are key for the purpose of this Element.

The GM perspective provided a response to the shortcomings of the VoC approach. It argues that national economies grow based on distinct patterns of demand (Baccaro & Pontusson Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016; Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Blyth and Pontusson2022). Instead of focusing on institutions and firm-based production systems, this perspective emphasizes how economies generate and sustain demand to fuel growth. Growth models in this perspective are defined descriptively based on the decomposition of GDP growth and the respective leading demand components, differentiating between consumption-led (e.g., the UK) and export-led models (e.g., Germany), for instance (Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Blyth and Pontusson2022). Crucially, the GM approach argues that such growth models are – to some degree – politically constructed and maintained. Governments shape particular models through their political choices and the respective macroeconomic policies. Business groups, unions, and voter segments form coalitions to support or contest a given model. Some GM analyses have used the Gramscian-inspired concept of a dominant social bloc to denote the political constellations of an entrenched bipartisan consensus on a growth strategy and crucial economic policies (Akcay & Jungmann, Reference Jungmann2023; Apaydin, Reference Apaydin2025; on the social bloc concept, see Amable & Palombarini, Reference Amable and Palombarini2024). The social bloc concept points to the occasional ideological framing of growth models as being in the “national interest,” downplaying the interests of marginalized groups and the inherent contradictions of a particular model (May et al., Reference May, Nölke and Schedelik2024). At the same time, growth models are inherently unstable and can be disrupted by external shocks (like financial crises), internal contradictions (like rising inequality), or political shifts, leading to pressures for adjustment or transformation. To summarize, the GM perspective makes crisis and change central to understanding capitalist diversity. Comparative political economists using this lens study how and why countries adopt certain growth models, how they cope with crises, and how institutions, coalitions, and ideas help sustain or shift these models over time (Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Blyth and Pontusson2022).Footnote 4

2.3 Conceptual Framework: Peripheral Growth Models in Emerging Capitalist Economies

By looking at the components and drivers of economic growth, its distributional implications and political underpinnings, the GM research program has shifted scholarly attention from the institutional structures of capitalist economies and their supply side effects on growth – the focus of the VoC perspective – back to macroeconomics and aggregate demand (Schwartz & Tranøy, Reference Schwartz and Tranøy2019). The analytical shift from supply to demand-side factors of the economy coincided with an evolving debate about the adequate macroeconomic theoretical foundations of growth model-inspired analyses (Hope & Soskice, Reference Hope and Soskice2016; Baccaro & Pontusson, Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2018; Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer2022). This discussion has led to substantial engagement of CPE scholars with PKE and its focus on “demand” or “growth regimes” (see Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer2022: 164–170 for overviews).Footnote 5

Although most growth model research to date has focused on advanced capitalist economies, first inroads have been made with regard to emerging economies (Schedelik et al., Reference Schedelik, Nölke, Mertens and May2021; Wood & Schnyder, Reference Wood and Schnyder2021; Akcay et al., Reference Akcay, Hein and Jungmann2022; Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer2022; Jungmann, Reference Jungmann2023; Baccaro & Hadziabdic, Reference Baccaro and Hadziabdic2024; Campana et al., Reference Campana, Vaz, Hein and Jungmann2024; Bulfone et al., Reference Bulfone, Madariaga and Tassinari2025). Country case studies and paired comparisons have used the framework to analyze stability and change in emerging capitalist economies (e.g., Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Doering and Gomes2021; Nölke et al., Reference Nölke, May, Mertens and Schedelik2022; Apaydin, Reference Apaydin2025; Güngen & Akcay, Reference Güngen and Akcay2024; Kalanta, Reference Kalanta2024) while others have leveraged the economies of Central and Eastern Europe to explore the political economy of FDI-led growth (Avlijaš et al., Reference Avlijaš, Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021; Ban & Adascalitei, Reference Ban, Adascalitei, Blyth, Pontusson and Baccaro2022; Bohle & Regan, Reference Bohle and Regan2021). Akcay et al. (Reference Akcay, Hein and Jungmann2022), Campana et al. (Reference Campana, Vaz, Hein and Jungmann2024), and Baccaro and Hadziabdic (Reference Baccaro and Hadziabdic2024) mapped the growth models of several large emerging economies and revealed not only variation between the countries but also a temporal shift in their growth models after the global financial crisis of 2008 and the end of the commodity boom in 2011 onward. Furthermore, recent scholarship has begun to conceptualize the notion of peripheral growth models (Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer2023; Bulfone et al., Reference Bulfone, Madariaga and Tassinari2025; Schedelik & Nölke, Reference Schedelik and Nölke2025), which refers to the “structural constraints imposed by global economic hierarchies” on growth trajectories in developing and emerging economies (Bulfone et al., Reference Bulfone, Madariaga and Tassinari2025, 296).

These and other studies on the political economy of emerging capitalist economies have suggested several factors that fundamentally enhance our understanding of growth, stagnation, and crisis in these countries. These factors, we argue, need to be more systematically integrated into the empirical GM research program. This Element aims to do so with respect to what we think are the three most important factors that have to be reflected in the study of peripheral growth models in emerging economies:

(1) A coherent typology of peripheral growth models needs to be developed. Such a typology must go beyond OECD-centric views and needs to take into account the stronger role for investments in emerging economies, which results from the need to expand less developed infrastructure and productive capacities. In particular, an investment-led model needs to be added to the prevalent juxtaposition of consumption-led and export-led growth models.

(2) The international context is important in a different way for most ECEs than for advanced economies. Growth in ECEs depends more strongly on how the country is integrated into global economic hierarchies and on systemic dynamics that come in the form of commodity cycles (which undergird many export-led growth models), a dependency on foreign capital (e.g., via FDI), and through processes of financial subordination magnified by global financial cycles. These international interdependencies create profound vulnerabilities vis-à-vis external shocks, which are typical for peripheral growth models.

(3) Growth and stagnation in ECEs depend differently on the embeddedness of economic actors in the political sphere than in advanced economies. While political coalitions and state-business relations are likely to define growth models across all types of political economies, the mechanisms through which politics shape particular growth trajectories in ECEs will usually differ from relatively stable Western systems of liberal democracy.

The selection of these factors is based on the literature on the political economy of development during the last decades. Based on this research, we are suggesting a more comprehensive research program for the GM perspective in emerging capitalist economies that not only studies macro-economic growth contributions in terms of aggregate demand components, but also systematically reflects on their international and macro-political embeddedness.Footnote 6 More specifically, we argue that, depending on the drivers of economic growth, a peripheral growth model’s vulnerability vis-à-vis external shocks varies considerably. But as growth models do not emerge automatically, their nature and degree of vulnerability are subject to various political factors.

2.4 Case Selection and Methods

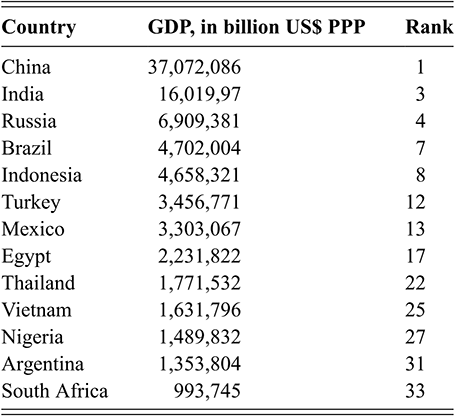

This Element investigates the growth trajectories of emerging capitalist economies, that is, mainly middle-income countries as defined by the World Bank. Our sample comprises thirteen ECEs that belong to the largest thirty-three countries with the biggest proportion of global GDP, according to the IMF (Table 1). This is where a large part of global growth has been attributed to, based on purchasing power parities. Given the GM perspective’s (narrow) focus on analyzing growth trajectories, we use this metric for our case selection instead of GDP per capita. In addition, we also do not aim to account for catch-up processes and the transition from middle- to high-income status. This would require an ordering of countries according to certain income thresholds, usually defined in per capita terms. Finally, the countries in our sample are a very diverse set of economies with different political-economic regimes and historical-institutional legacies, covering all the major world regions. This, we contend, should assist us in developing our theoretical perspective of peripheral growth models as a useful and adaptive framework for the analysis of growth trajectories in emerging economies.

| Country | GDP, in billion US$ PPP | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| China | 37,072,086 | 1 |

| India | 16,019,97 | 3 |

| Russia | 6,909,381 | 4 |

| Brazil | 4,702,004 | 7 |

| Indonesia | 4,658,321 | 8 |

| Turkey | 3,456,771 | 12 |

| Mexico | 3,303,067 | 13 |

| Egypt | 2,231,822 | 17 |

| Thailand | 1,771,532 | 22 |

| Vietnam | 1,631,796 | 25 |

| Nigeria | 1,489,832 | 27 |

| Argentina | 1,353,804 | 31 |

| South Africa | 993,745 | 33 |

Methodologically, we are using the following approaches for tackling the identification of growth models in ECEs and macro-political factors. For the detection of peripheral growth models, we employ a simple demand-side approach for growth accounting, whereas our study of political factors sustaining these models will be based on country vignettes. Vignettes, which have found their way from social psychology into other social sciences, are commonly understood to present case histories for the purpose of illustrating important traits of a situation or constellation. Importantly, they lend themselves particularly well to the development of a research program, in comparison to other traditions of case study research that require thick descriptions (Hughes, Reference Hughes1998, 381; Welch et al., Reference Welch, Piekkari, Plakoyiannaki and Paavilainen-Mäntymäki2011, 751–2).

Our vignettes are short case studies on the political factors supporting specific growth models. They do not claim to provide comprehensive evidence, but rather to validate a conceptual point. Correspondingly, the selection of country cases is based on their representative character for the conceptual argument at hand. Our empirical vignettes draw primarily on paired comparisons of “most similar” countries: Brazil and Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa, as well as Thailand and Vietnam. These pairs are structured similarly: They follow the same overall growth model but differ in their institutional and political approaches toward addressing the resulting structural vulnerabilities. While three of these countries were able to uphold growth overall in the time period under scrutiny (Indonesia, Turkey, and Vietnam), the other three experienced a substantial decline in their growth rates and stagnation or outright economic crisis (Brazil, South Africa, and Thailand; see Table 3). A notable finding in Section 5 relates to our argument that growth models depend on certain political-institutional constellations. We show that the less vulnerable economies in our sample, Indonesia, Turkey, and Vietnam, have associations or similar (informal) institutional arrangements that are a crucial element in the accommodation between various social groups, as well as between the state and business. These play little or no role in the more vulnerable cases of Brazil, South Africa, and Thailand. This shows that, at least within the limited time period studied in this Element, the political stabilization of a growth model rests on broad societal support and functional mechanisms for state-business relations.

3 A Typology of Peripheral Growth Models

In this section, we first introduce different types of peripheral growth models that will guide the study of growth trajectories of selected emerging capitalist economies in the following sections. We then analyze several descriptive statistics in order to identify growth models in our sample countries over the past two decades.

3.1 Adapting Growth Model Typologies to Emerging Capitalist Economies

Being aware of the fallacies of typological theorizing (Hay, Reference Hay2020), we acknowledge the limits of this framework right from the start. As ideal types are “limiting concept[s] with which the real situation or action is compared” (Weber, Reference Weber and Finch1947 [1922], 93, original emphasis), our typology is primarily meant to be a heuristic device for comparative analysis (Swedberg, Reference Swedberg2018, 189–90). It aims to reduce the complexity of contemporary capitalist development in emerging economies and to provide the conceptual basis for hypothesis formulation and empirical research. Of course, it does not claim to cover all growth experiences in the global South. Nor should the aim be to group all countries into ideal-typical categories. In reality, many cases display features of several of the ideal types mentioned below, thereby creating tensions with the temporal and spatial specificity of growth trajectories. Needless to say, not every country exhibits a well-defined growth model at any point in time, as there is ample evidence of crisis and stagnation in peripheral economies.

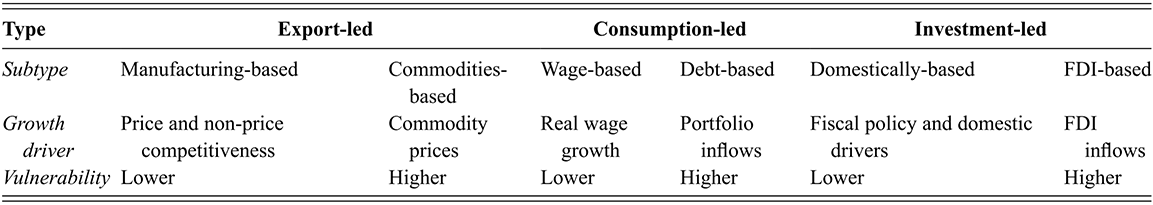

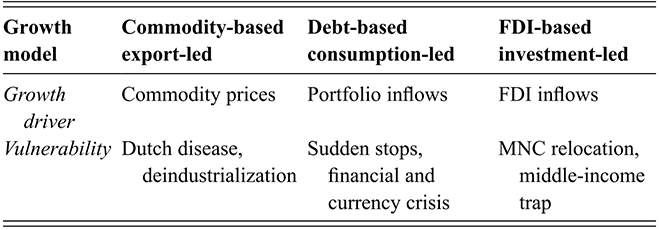

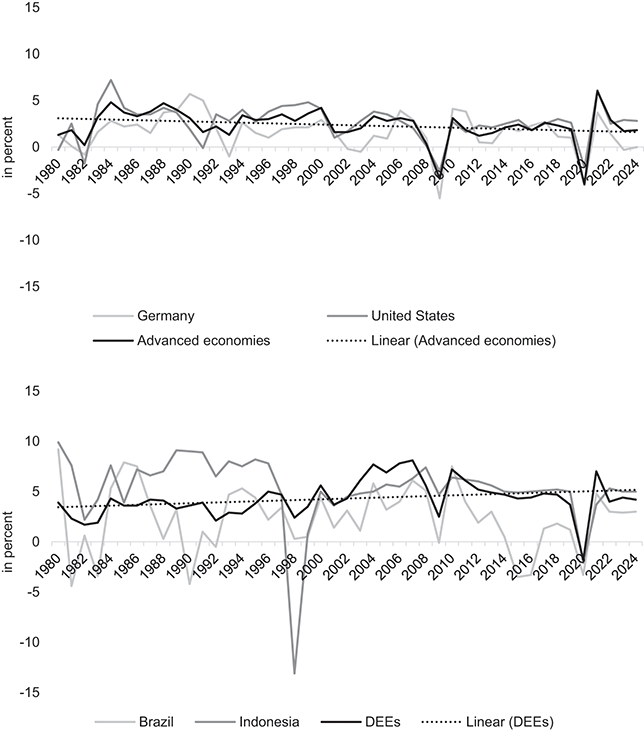

The identification of growth models starts with a basic distinction between their main components of aggregate demand: private consumption, government consumption, investment, and (net) exports. Next to these broad types of growth models, we introduce several subtypes, which, on the one hand, capture the main sources of growth experiences of emerging economies identified in the literature and, on the other hand, differ with regard to their degree of economic vulnerability (Table 2).

Table 2Long description

The table further differentiates between several subtypes of each model, based on the respective growth driver: manufacturing-based export-led growth, commodities-based export-led growth, wage-based consumption-led growth, debt-based consumption-led growth, domestically-based investment-led growth, and F D I-based investment-led growth.

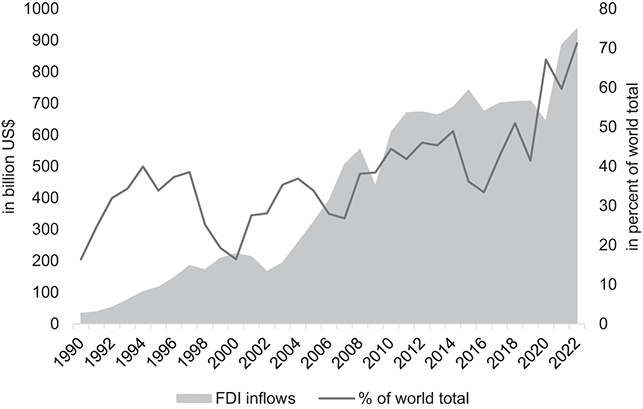

Due to their less developed productive structure and lower capital stock, investments play a much more important role in emerging economies than in advanced economies. The recent experience of India or China exemplifies this point (Ahuja & Nabar, Reference Ahuja and Nabar2012; ten Brink, Reference ten Brink2019).Footnote 7 Therefore, we propose a third type of growth model – investment-led growth – which has so far not been identified in the core countries (see, e.g., Picot, Reference Picot, Hassel and Palier2021; Baccaro & Hadziabdic, Reference Baccaro and Hadziabdic2024). Moreover, due to their position in the world economy, emerging economies are generally characterized by higher vulnerability – even though their vulnerability may vary with their economic profile and regime type. This elevates the possible negative impacts of variables linked to their international interdependencies (Bonizzi et al., Reference Bonizzi, Kaltenbrunner, Powell, Mader, Mertens and van der Zwan2020), such as massive capital outflows as witnessed during the 2008 global financial crisis and the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to account for this salient feature of growth in peripheral economies, we introduce the separate dimension of vulnerability, ranging from low to high, depending on the respective growth driver. The latter are factors, which are “not themselves part of aggregate income but influence the growth of its components” (Kohler & Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer2022, 1319).

Against this backdrop, we distinguish the following peripheral growth model types and their respective subtypes:

(i) Export-led growth models: These growth models are defined as sustained periods of growth that are primarily driven by exports. Here, it matters substantially which sectors of the economy are the main exporters. Economic complexity, value added, and the structure of global markets vary widely and have important repercussions on growth trajectories. Arguably, the main export sectors in emerging economies are either manufacturing or commodities. Services such as tourism are a third “export” sector that accounts for a sizable share of GDP growth, albeit mainly for smaller developing countries such as Bhutan and Jamaica.

(1) Manufacturing-based export-led growth refers to episodes when the main export sectors are in manufacturing. Countries can thrive based on higher price or non-price competitiveness, depending on the degree of price elasticity of demand of different manufacturing sectors and the structure of global markets. But typically, with poor technological capabilities, prices have a binding constraint on the manufacturing-based growth models of most low- and middle-income countries. Consequently, there is a tendency to repress real wage growth and, as a result, domestic consumption in economies with a large export sector is generally lower. This has negative repercussions on domestic welfare and inequality in the short term. However, in a mid- to long-term perspective, a manufacturing-based export-led growth model potentially leads to more sustainable and inclusive development, especially if a country manages to transition from price to non-price competitiveness (product differentiation, quality, and innovation), as exemplified by Korea.Footnote 8

(2) Commodities-based export-led growth refers to episodes when the main export sectors are natural goods. This holds true for the vast majority of peripheral economies. Lacking short-term alternative options, many countries, by necessity, adopt such a development strategy. However, this type of growth model has potentially destabilizing effects. First, commodity prices are highly volatile and often lead to pronounced boom-bust scenarios. Second, rising commodity prices generally trigger capital inflows from abroad, resulting in a loss of competitiveness for manufacturing and thereby gradually leading to deindustrialization (the Dutch Disease phenomenon). Further negative effects relate to political instability and armed conflicts arising from distributional conflicts over the exploitation of commodity rents (the so-called resource curse).

(ii) Consumption-led growth models: These growth models are defined as sustained periods of growth primarily driven by private consumption. Household consumption can be financed by two main sources: wages or debt. Hence, we further distinguish between two main subtypes here, wage-based growth and debt-based growth.

(1) Wage-based consumption-led growth refers to episodes when sustained real wage growth leads to higher incomes, which in turn fuel household consumption expenditure. Increased demand may then spur further investment by companies, resulting in a virtuous cycle of capital accumulation. Politically, such a growth model can be induced by several policies, such as minimum wage increases, public sector pay increases, or the strengthening of collective bargaining institutions and trade unions. We witnessed such a growth model in many countries in the two decades after World War II. However, the model has an inherent tendency to fuel inflation through continuous wage pushes and to squeeze the profits of capital (Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Blyth and Pontusson2022, 506).

(2) Debt-based consumption-led growth refers to episodes when credit expansion leads to higher disposable incomes of households, fueling consumption expenditure. This is particularly relevant for capital goods industries and real estate. One of the main drivers of debt-based models is capital inflows from abroad, which can drive down long-term interest rates and push up local asset prices. This may contribute to a credit boom, spurring domestic economic activity. However, relying too heavily on the inflow of foreign capital in turn creates vulnerability, as the danger of sudden stops and boom-bust cycles looms large.Footnote 9

(iii) Investment-led growth models: These growth models are defined by sustained periods of growth that are primarily driven by investment. Investment is based on two main sources: domestic or foreign capital.

(1) Domestically-based investment-led growth refers to episodes when increased investments in infrastructure, housing, plants, or machinery fuel growth. Fiscal policy is arguably one of the main drivers of such a growth model, albeit there are numerous other possible drivers of (private) investment (such as new technologies, for instance). Beyond boosting demand in the short run, investments build long-term economic capacity, enhance productivity, and create additional employment. If investment predominately takes place in (residential) housing, there may be overlaps with the debt-based growth model discussed earlier. Instability in this model may result mainly from overproduction and overindebtedness of the business sector.Footnote 10

(2) FDI-based investment-led growth refers to episodes when investments by multinational corporations (MNCs) in local production plants drive the growth model. This model, by definition, heavily relies on a continuous inflow of FDI. Interrupting these flows, for example, through the relocation of production plants by MNCs, represents the main source of vulnerability for this type of growth model. In a mid-term perspective, this translates into a structural challenge for an FDI-led development strategy, as MNCs often are not willing to share advanced technology with host countries (Gertler, Reference Gertler, Peck and Yeung2003; Liu, Reference Liu2008). Consequently, the latter eventually might be stuck in a so-called middle-income trap, which refers to a loss of competitiveness in labor-intensive manufacturing, while still not having reached the capacities for advanced production and R&D related activities.

We restrict ourselves to these types of growth models, which cover the main options for pursuing growth in emerging economies. Other models, which are, for example, based on remittances, foreign aid, or tourism, are mainly relevant for smaller developing countries with specific economic endowments and are hardly comparable to other economies.

3.2 Identifying Peripheral Growth Models

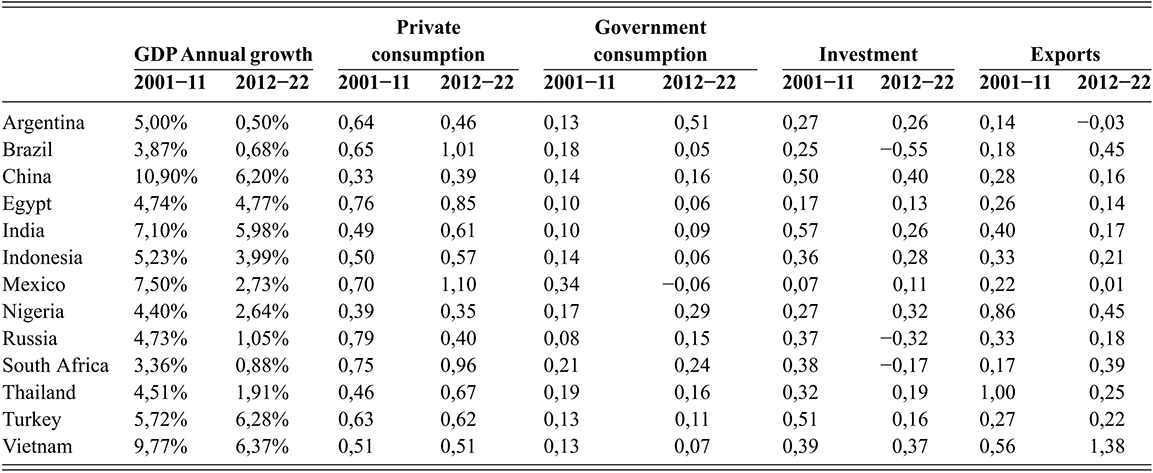

To develop an empirical approximation to growth models in ECEs, we use the relative contributions of aggregate demand components to GDP growth. Following Hein et al. (Reference Hein, Paternesi Meloni and Tridico2021), we calculate the relative contributions to GDP growth by dividing the change in one aggregate demand component (e.g., C for private consumption) by the change in GDP (Y: dC/dY). We are aware of the limitations of this method, which is less suited to specify the role of exports, the vulnerability of growth models, and their main drivers (Kohler & Stockhammer, Reference Stockhammer2022, 1318–19; Baccaro & Hadziabdic, Reference Baccaro and Hadziabdic2024, 1330–31). Traditionally relying on net exports as one component of aggregate demand, this method tends to either over- or underemphasize the actual role of exports for a country’s growth model. Many emerging economies have a less sophisticated productive structure and thus have high volumes of consumption or capital goods imports. In addition, their major export items are commodities, that is, raw materials and agricultural goods. Due to the high share of imports that are consumed by the private and/or the public sector of these economies, their massive gross exports often do not show up in growth contributions, where net exports are generally low or even negative. Therefore, we focus on gross instead of net exports.Footnote 11 In order to identify the vulnerabilities and drivers of each growth model, we employ qualitative case vignettes in the subsequent sections of this Element.

The period of observation depends on the availability of harmonized data (mostly 2000–2022), which we further split into two subperiods (2001–2011 and 2012–2022). The rationale for this division relates to the main growth drivers of peripheral growth models: the years 2011 and 2012 mark the end of the commodity super cycle, a peak of capital flows to ECEs, and a plateauing of FDI inflows to ECEs (Miranda-Agrippino & Rey, Reference Miranda-Agrippino, Rey, Gopinath, Helpman and Rogoff2022; Jungmann, Reference Jungmann2023; see Section 4). Furthermore, prior studies have identified growth model shifts in several ECEs around the year 2011 as well (Campana et al., Reference Campana, Vaz, Hein and Jungmann2024).

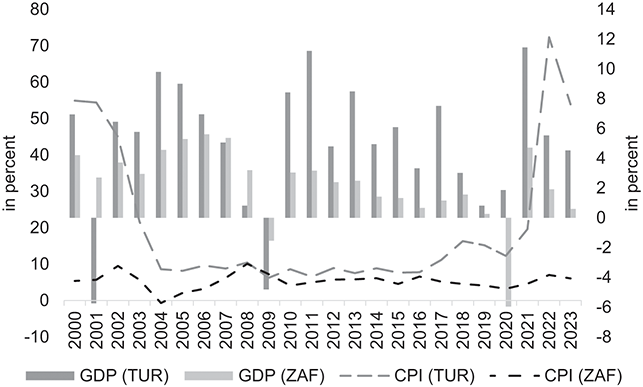

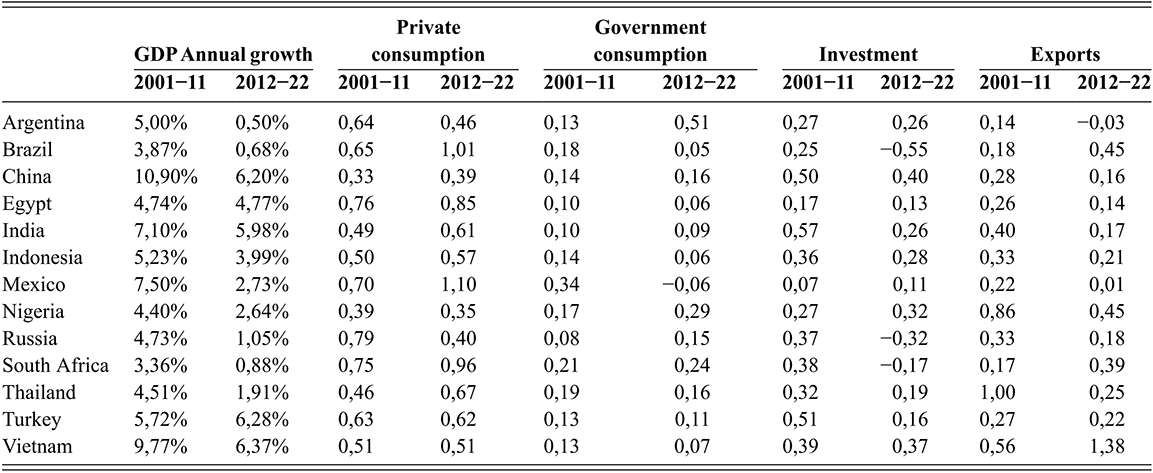

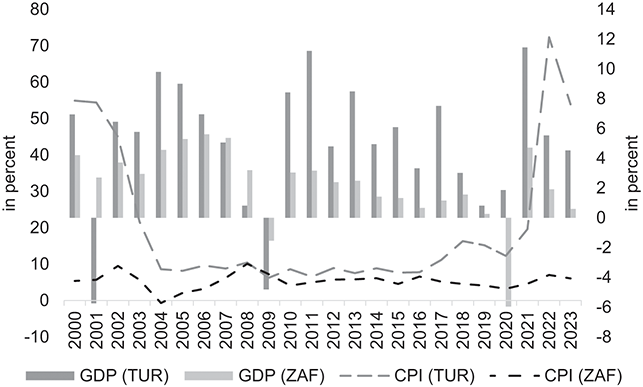

Table 3 displays the results for the fourteen selected ECEs. While ECE annual growth rates are, on average, much higher than in the United States or European countries in that period (2.15 percent for the US and 1.56 percent for the EU respectively, see World Bank, 2025), data for some ECEs, notably Argentina, Brazil, Russia, and South Africa, also show a steep decline from the 2000s to the 2010s. These countries seem to follow those vulnerable trajectories of boom-bust growth as laid out earlier. Thailand is another case that experiences a substantial drop in its GDP growth between the two periods, although less pronounced than the other four countries. The rest of the countries in our sample, notably China, Indonesia, and Vietnam, also show relatively declining growth rates overall, but appear to have been more successful in sustaining growth. Egypt and Turkey are the only countries in the sample whose growth rates increase in the later period.

Note: We have calculated the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for each aggregate demand component for each period. CAGR represents the annual growth rate required to move from the starting GDP to the final GDP over a specified period, assuming constant growth at this rate. By smoothing out yearly fluctuations, it eliminates the effects of volatility and is well-suited for long-term comparisons and trend analysis. For private consumption, we use household consumption expenditure; for investments, we use gross capital formation; for government consumption, we use general government final consumption expenditure; for net exports, we calculate separately the growth rates of exports and imports of goods and services. The absolute contribution for each aggregate demand component was obtained by multiplying their CAGR by their average weight shares in each period. Finally, we normalized them to obtain their relative contributions. The sum of private and government consumption, investment, and net exports equals to one. As the table displays exports rather than net exports, the sum will typically exceed unity.

Table 3Long description

The table shows the relative contributions of each aggregate demand component to G D P growth for Argentina, Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, and Vietnam in the period from 2001 until 2022.

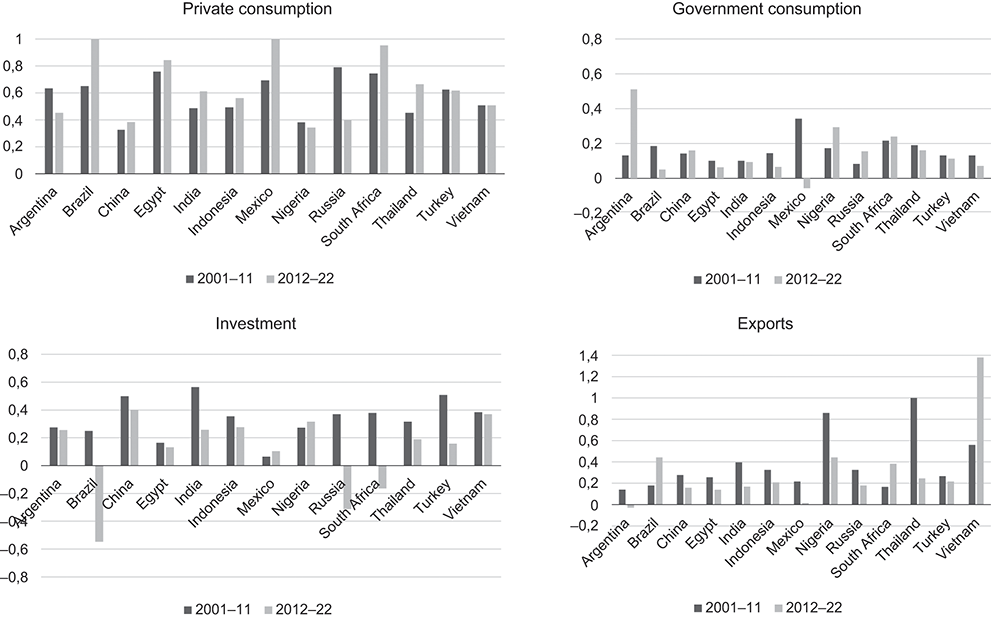

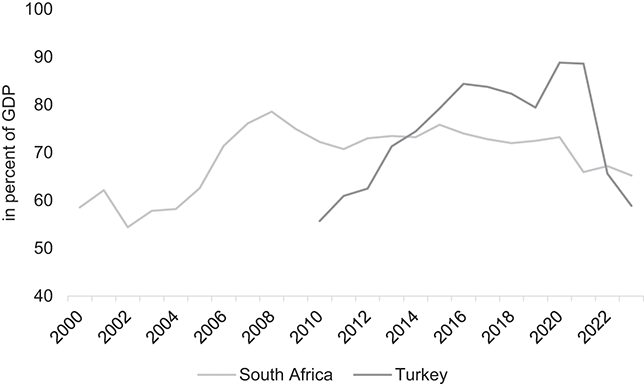

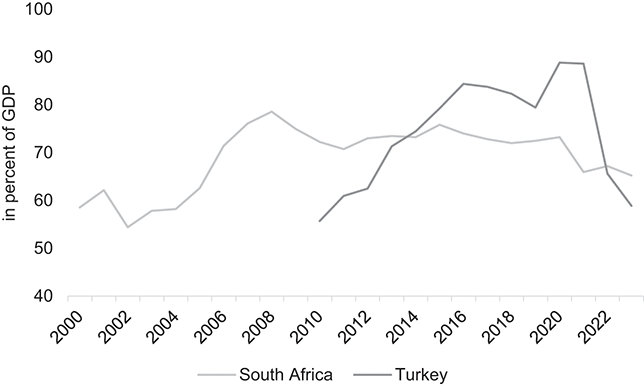

According to this data, there is not one single growth model for ECEs (Table 3). In general, however, private consumption plays an important role in many countries in our sample. Only China and Nigeria exhibit a slightly lower but still significant contribution of private consumption to GDP growth. South Africa appears to align with the consumption-led model, although government consumption plays an important role as well. The same holds true for Turkey, albeit with less pronounced government consumption. As we will demonstrate in the next section, household indebtedness has been driving this trend in both economies. While credit expansion in South Africa was especially salient in the period before the global financial crisis, it became more important in the subsequent period in Turkey. In both cases, capital inflows have been drivers of debt-based growth (Section 4). Wage-based growth models have been rare since the 1980s – with Israel between 2008 and 2018 as an exception (Bondy & Maggor, Reference Bondy and Maggor2024). Consequently, we do not find it in our sample.

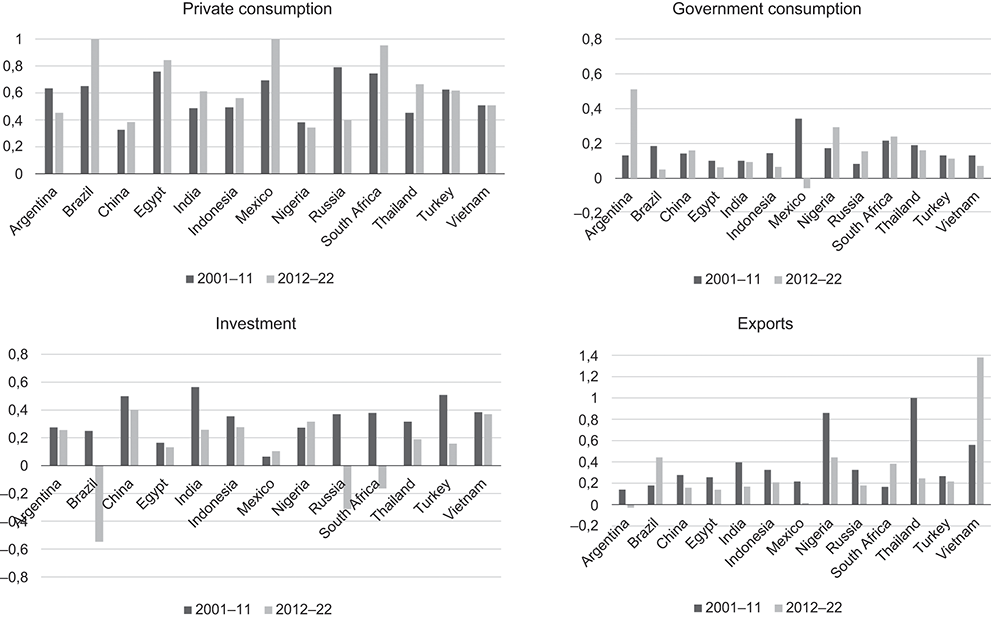

Overall, government consumption is less significant than the other demand components in our sample countries (Figure 3). Only Argentina, and to some extent Mexico and Nigeria, exhibit a relatively high degree of this component. In the former, this is mainly due to a sustained period of expansionary fiscal and social policies under the Kirchner governments (2003–2015) (Ianni, Reference Ianni2024), with public administration as well as educational and health services being major drivers of GDP growth (Baccaro & Hadziabdic, Reference Baccaro and Hadziabdic2025).

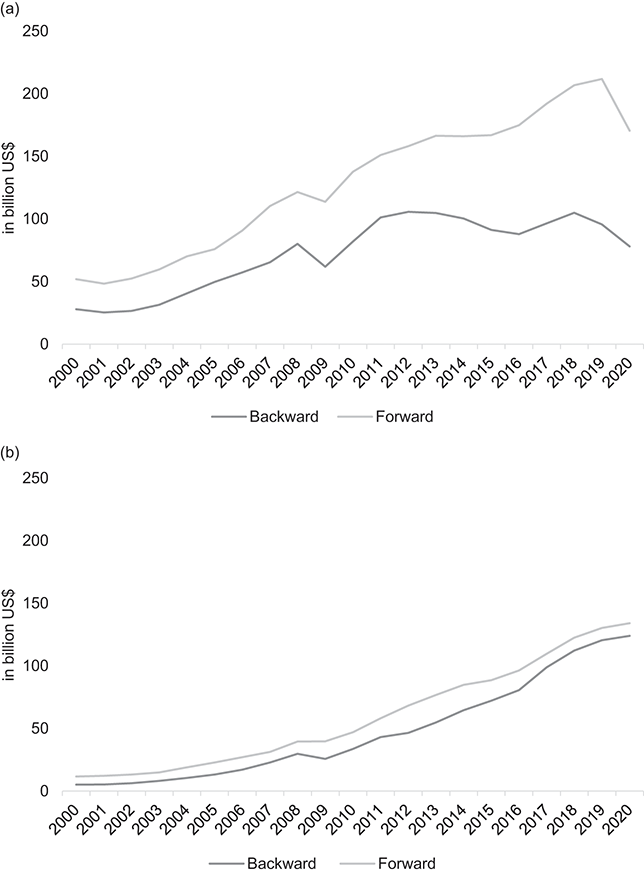

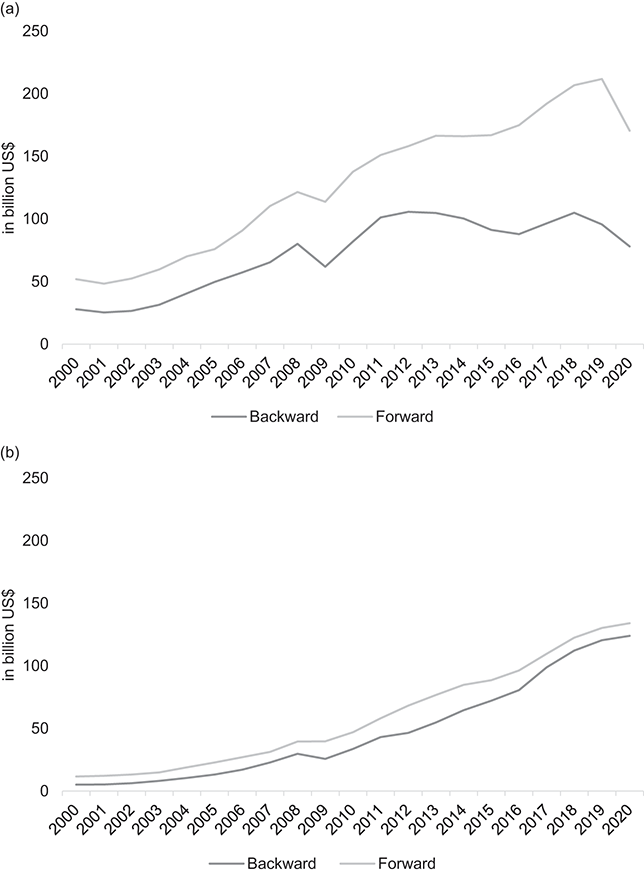

Investment, by contrast, seems to play a major role in many countries in our sample. Notably, China and India display a strong investment-led profile similar to that of Turkey and South Africa, though this tendency is declining sharply in the latter two cases. In all the cases, the construction sector plays an important role, contributing up to 34 percent to overall GDP growth in China in the 2010s, for instance (Baccaro & Hadziabdic, Reference Baccaro and Hadziabdic2025). Thailand and Vietnam also feature a significant share of investment in their GDP growth, but mainly in the manufacturing sector, dominated by foreign MNCs. However, this share is declining substantially in Thailand, while Vietnam seems to uphold it in the period 2012–2022 as well. As we will show in the next section, investment in both countries is heavily driven by FDI (Section 4).

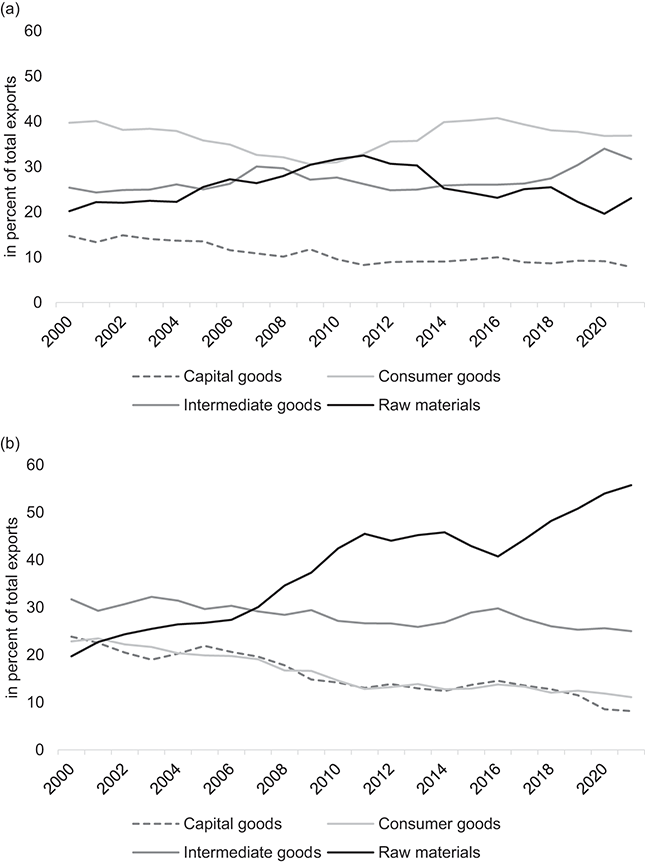

Finally, exports are very volatile but still significant in countries such as Brazil, Indonesia, Nigeria, Thailand, and Vietnam. While Thailand and Vietnam are highly integrated into global production networks, there is no country in the sample that displays a proper manufacturing-based export-led growth model, relying on indigenous manufacturing capacities. Given their heavy GVC participation, both Thailand and Vietnam only feature very high gross exports, while their net export contributions to growth are negligible or even negative. There is a striking similarity to the FDI-led models of East Central Europe, which also exhibit high volumes of gross exports, while foreign investment is the main driver of GDP growth (Avlijaš et al., Reference Avlijaš, Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021; Bohle & Regan, Reference Bohle and Regan2021). Brazil and Indonesia, by contrast, are part of a larger group of peripheral economies featuring commodities-based export-led growth, where commodity revenues at least temporarily serve as a basis for redistributive policies supporting domestic consumption (Nölke et al., Reference Nölke, ten Brink, May and Claar2020, 137–9, Passos & Morlin, Reference Passos and Morlin2022; Schedelik et al., Reference Schedelik, Nölke, May and Gomes2023). As we demonstrate in the subsequent section, both countries managed the vulnerabilities associated with this type of growth model very differently.

In sum, investment and private consumption are the key contributors to growth in the countries in our sample, while government consumption and exports are less significant overall. This questions the popular diagnosis of emerging economy growth as being mainly export-led, as discussed in the experience of East Asian “tiger states” in the 1980s (World Bank, 1993) or the rise of the BRICS countries, especially China, in the 2000s (Feenstra & Wei, Reference Feenstra and Wei2010). Further juxtaposing peripheral growth models with the consumption- and export-led models in advanced capitalist economies, we find investments to be heavily important for some ECEs, supporting our intuition for the addition of an investment-led growth model to the typology of an extended GM perspective. For a theory of capitalist diversity this should not be a surprising point to make since investments should be at the core of any theory about growth – and in fact has been for political economy scholarship of the so-called “golden age of capitalism” (Marglin & Schor, Reference Haggard, Kim and Moon1991; Schwartz & Tranøy, Reference Schwartz and Tranøy2019) and earlier development theories, such as those associated with the model of import-substitution industrialization in the global South (Irwin, Reference Irwin2021). It stands that only investments, besides representing an increase in aggregate demand, also expand productive capacity. Consumption and export growth boost demand and thus the utilization of the capital stock, yet only investments increase the capital stock. This point is particularly salient for ECEs since they usually have a lower capital stock than advanced economies and need to invest in order to catch up. At the same time, since higher investments yield additional capacity, there is also a need to find demand for this increased productive capacity.

Systematically introducing the possibility of an investment-led growth model helps us to understand the various political-economic trajectories of high-growth economies. We can also learn from studies on former transition economies in Central and Eastern Europe, as well as Ireland, which pointed to an FDI-based model (e.g., Bohle & Regan, Reference Bohle and Regan2021). For instance, the macro-political and institutional factors that shore up and constantly challenge such an investment-led growth model vary with the latter’s integration into the world economy and the type of investments within that model. For this reason, we later turn to a more qualitative vignette approach that is able to carve out potential causal effects supporting and sustaining an investment-led growth model by studying the growth trajectories of Thailand and Vietnam.

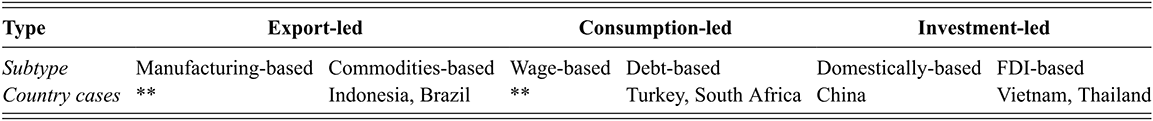

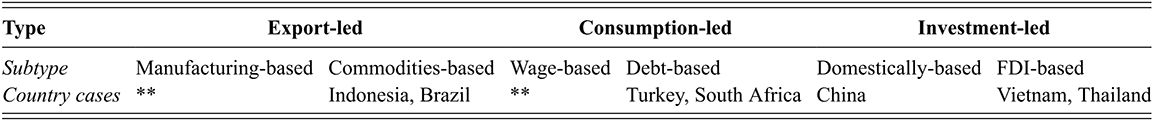

After all, and it is worth repeating, none of these models is dominant for ECEs as a group, and all types require differentiation. Table 4 proposes such a differentiation with a view toward exemplary cases. However, in contrast to the clear-cut growth models which could be found in Europe (only) before the global financial crisis (Baccaro & Pontusson, Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2016; Hein et al., Reference Hein, Paternesi Meloni and Tridico2021), we should be careful with the neat categorization of countries into singular types. We find a much higher degree of hybridity for the growth models in ECEs. Moreover, traditional growth model decomposition may lead to misleading impressions, given the high export shares for FDI-based models and the (partial) utilization of commodity export revenues for the stimulation of domestic consumption in commodity-led models discussed earlier. Correspondingly, our simplified classification should be taken as an invitation for further research on how to understand the nature of peripheral growth models.

Note: ** Not found in our sample.

Table 4Long description

The table identifies country cases for several growth model types, for instance Brazil and Indonesia as commodities-based export-led growth, Turkey and South Africa as debt-based consumption-led growth, Vietnam and Thailand as F D I-based investment-led growth, as well as China as domestically-based investment-led growth.

Moreover, we posit that the considerable heterogeneity within the category of ECEs demands an institutionally sensitive process when classifying growth models. In order to substantiate this claim, we move to the level of international interdependencies of peripheral growth models (Section 4) and their political underpinnings (Section 5). Through the study of commodities-based export-led growth (Brazil and Indonesia), debt-based consumption-led growth (South Africa and Turkey), and FDI-based investment-led growth (Thailand and Vietnam), we show how the international insertion of a country’s growth model shapes its vulnerabilities toward exogenous shocks. Still, each paired comparison demonstrates that despite structural dependencies, governments in ECEs can successfully mitigate the vulnerabilities arising from similar peripheral growth models. This capacity does not only rest on appropriate macroeconomic policies, but also on certain macro-political conditions. Subsequently, we illustrate the importance of these various factors, which represent constellations neglected in the study of growth models in the global North.

4 International Interdependencies and Peripheral Growth Models

In the following, we analyze three peripheral growth models in more detail. By drawing on paired comparisons of “most similar” countries, we outline some core features of commodities-based, debt-based, and FDI-based growth models, their respective growth drivers, and short- or mid-term vulnerabilities (Table 5). Specific attention is given to the ability of national governments to manage these vulnerabilities, under specific political conditions, contrasting the idea that their economic models are essentially determined by global dependencies (e.g., Kvangraven et al., Reference Kvangraven, Koddenbrock and Sylla2021; Alami et al., Reference Alami, Alves and Bonizzi2023). The GM perspective, with its emphasis on (short-term) economic policies, lends itself toward an identification of economic agency. In doing so, we are arguing that heterodox economic policies overall are more successful than the liberal orthodoxy in managing the vulnerabilities stemming from their insertion into the global economy during this particular time period (Alami & Dixon, Reference Alami and Dixon2020; Petry et al., Reference Petry, Nölke and Koddenbrock2024; Petry & Nölke, Reference Petry, Nölke, Petry and Nölke2025). Correspondingly, we are looking at two types of causalities here. On the one hand, we are pointing out how external growth drivers (commodity prices, portfolio, and FDI flows) are co-constituting the three types of peripheral growth models. On the other hand, we are sketching how, in each of these types, macroeconomic and industrial policies can make a difference with regard to the degree of each vulnerability.

Table 5Long description

Commodity-based export-led growth is associated with Dutch disease and deindustrialization; debt-based consumption-led growth is associated with sudden stops and currency crises; F D I-based investment-led growth is associated with M N C relocating and the middle-income trap.

4.1 Commodity Price Cycles and Export-Led Growth Models

Recently, GM scholarship has begun to study export-led growth models, especially the commodity-based subtype. Arguably, this is one of the most prevalent peripheral growth models globally (Schedelik et al., Reference Schedelik, Nölke, May and Gomes2023). This model heavily relies on the development of commodity prices, which are set on global markets with little or no pricing power for producer countries. In addition, commodity prices are characterized by large swings, dubbed commodity super cycles, where prices rise sharply for several years before plummeting (Erten & Ocampo, Reference Erten and Ocampo2013). Commodity price fluctuations overproportionally affect developing and emerging economies, which, on average, are less diversified and more commodity-dependent than advanced economies. These price cycles not only have a direct impact on export volumes and earnings, but also on macroeconomic stability, as economic activity in commodity-dependent ECEs closely mirrors the price movements of their major export items (IMF, 2012, 125). Here, we can draw on decades of development studies research, which has pointed toward the significant macroeconomic effects of an overreliance on natural resource extraction (see the literature on the “resource curse,” cf. Ross, Reference Ross2015).

The most important mechanism associated with fluctuations in commodity prices is the so-called “Dutch Disease” – termed after the economic side-effects of natural gas discoveries in the Netherlands in the 1950s (Corden, Reference Corden1984). It refers to the real appreciation of the currency due to huge capital inflows into investment projects in the booming commodity sectors and/or large increases in commodity revenues during boom periods (Frankel, Reference Frankel2010, 20). This results in increased domestic income and spending by the private and especially public sector, leading to higher prices and output in the nontradables sectors and consequently to higher wages across the economy (the so-called “spending effect”). At the same time, capital and labor move from other parts of the economy to the booming commodity sectors, which results in rising prices of nontradables vis-à-vis other tradables (the so-called “resource movement effect”). Both effects lead to a real exchange rate appreciation and, therefore, to a loss of international competitiveness and declining output in the manufacturing sectors and, hence, to deindustrialization (Brahmbhatt et al., Reference Brahmbhatt, Canuto and Vostroknutova2010). The predicament of the “Dutch Disease” is much less likely to occur in advanced economies that have developed a strong reliance on exports (such as Germany). These economies never fully tilt toward structural dependency – not least because the market structures for manufactured goods and commodities are fundamentally different: “what you export matters” (Hausmann et al., Reference Hausmann, Hwang and Rodrik2007). More specifically, avenues for diversification and technological upgrading are limited for most commodity-dependent developing and emerging economies, and depend on sustained political efforts, which are negatively affected by commodity price swings (UNCTAD, 2021).

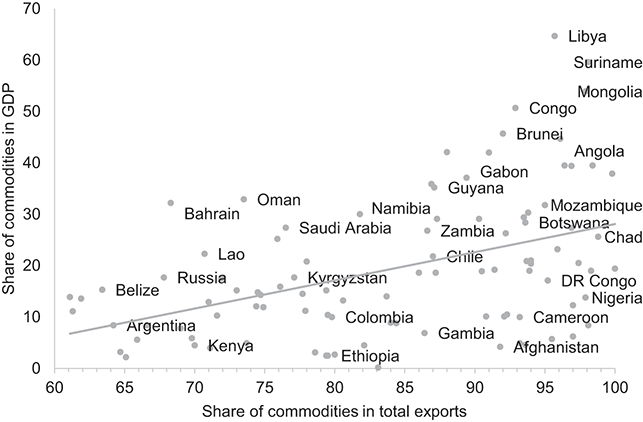

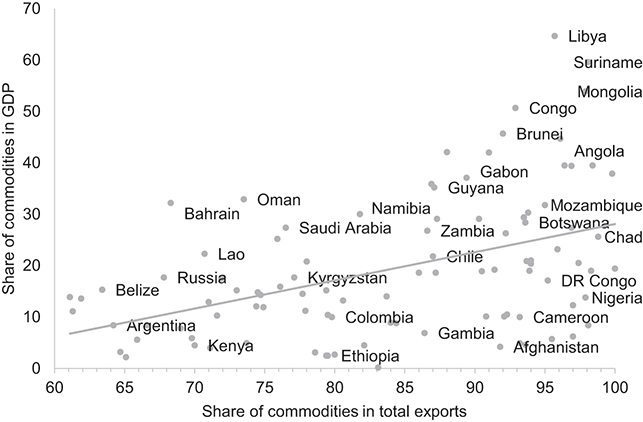

The reliance on commodity exports is a recurring and prevalent feature of most developing and emerging economies. In the 2018–2019 period, 101 countries out of 195 UNCTAD member states, that is, 53 percent, were commodity-dependent, that is, with a commodity export product share of more than 60 percent (UNCTAD, 2021, 5). Beyond that, we can identify a correlation between the degree of commodity dependence, that is, commodity exports as a share of merchandise exports, and the contribution of commodity exports to a country’s gross domestic product (Figure 4). A higher share of commodity export dependence is associated with a higher share of commodity exports in a country’s GDP. Commodity dependence, thereby can be as high as 99.8 percent in the case of Iraq and even 100 percent in the case of South Sudan. Furthermore, several countries rely on only one or a few commodities. Countries such as Iraq (93.5 percent), Angola (88 percent), Chad (79.6 percent), and Guinea-Bissau (88.4 percent) depend heavily on the export of one single product (UNCTAD, 2019).

Figure 4 Commodity dependence of developing and emerging economies

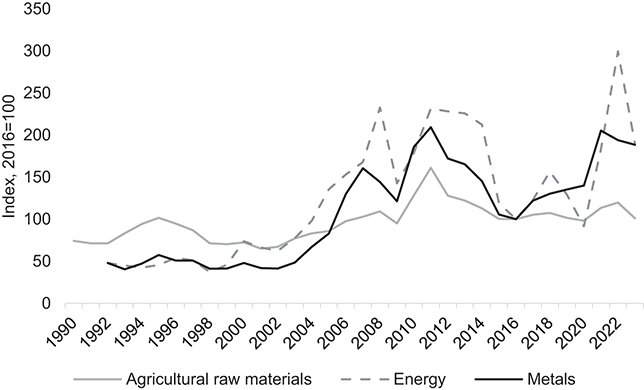

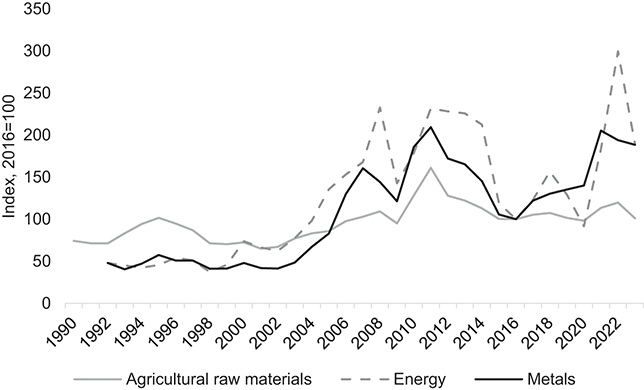

In the recent past, China’s rapid industrialization and the related output growth in the 2000s generated immense demand for primary products. From 1997 to 2017, China’s share of global energy consumption more than doubled, from 11 to 23 percent, while its share of global metals consumption even increased fivefold, from 10 to 50 percent (World Bank, 2018, 11). In comparison, advanced economies’ share of global energy and metals consumption declined from 50 to 40 percent and 70 to 30 percent, respectively, in the same period. This demand shock fueled a sustained commodity price boom, which lasted until the early 2010s. The commodity super cycle came to a halt during the GFC and particularly after 2011, when commodity prices contracted sharply (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 Commodity price cycles

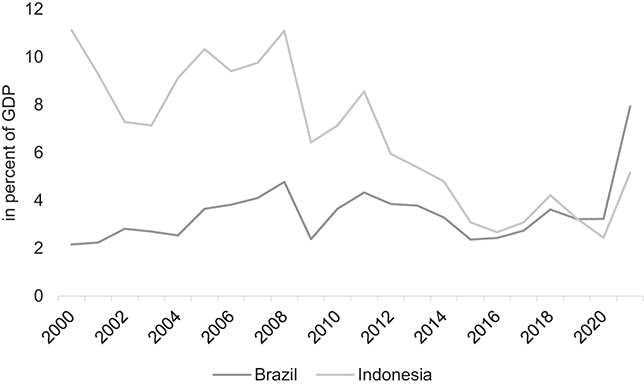

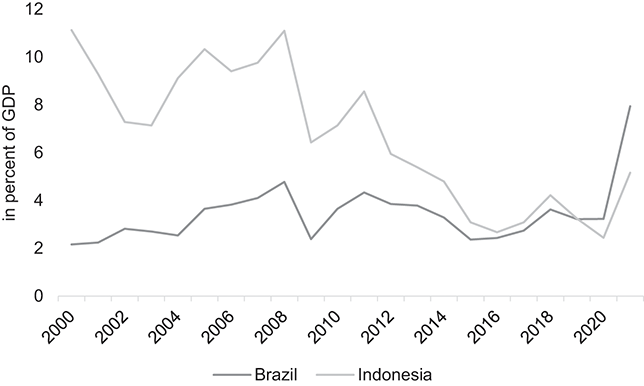

We can see the effects of these fluctuations on growth models by comparing Brazil and Indonesia, which are both commodity exporters and of a similar size. In both countries, the change in the growth trajectory at the end of the 2000s is striking, also in comparison with other major emerging economies (Section 3). Whereas exports were growth drivers for the two countries in the early 2000s, they were both hit hard by the strong reduction in export revenues after the end of the commodity boom that had been driven by China. In other words, the investment-led growth model in China created the demand for resources provided by extractivist suppliers with their commodities-based export-led growth model, only to increase pressure for adjustment when prices fell.