1. Introduction

An immediate consequence of the celebrated Dirichlet’s class number formula is that

![]() $L(1,\chi)\gt0$

for any real primitive multiplicative character

$L(1,\chi)\gt0$

for any real primitive multiplicative character

![]() $\chi$

of modulus q. It thus follows that there exists some

$\chi$

of modulus q. It thus follows that there exists some

![]() $x_0(q)$

which may depend on q such that

$x_0(q)$

which may depend on q such that

Establishing quantitative variants of (1·1) is a fundamental problem related to the existence of putative Siegel zeros. Such problems have origins in the work of Turán [ Reference Turán15 ], who showed that if partial sums of the Liouville function satisfy

then the Riemann hypothesis is true. Haselgrove [

Reference Haselgrove11

] proved that (1·2) is false and Borwein, Ferguson and Mossinghoff [

Reference Borwein, Ferguson and Mossinghoff3

] have established that

![]() $x = 72, 185,376,951,205$

is the smallest integer counterexample to (1·2). This naturally raises the question: why is this number so large?

$x = 72, 185,376,951,205$

is the smallest integer counterexample to (1·2). This naturally raises the question: why is this number so large?

As noted by Granville and Soundararajan [

Reference Granville and Soundararajan7

], combining Haselgrove’s result with quadratic reciprocity implies that for any large

![]() $x_0\gt0$

there exists a real Dirichlet character

$x_0\gt0$

there exists a real Dirichlet character

![]() $\chi$

such that

$\chi$

such that

In particular,

![]() $x_0(q)$

in (1·1) is not bounded by a constant independent of q. If

$x_0(q)$

in (1·1) is not bounded by a constant independent of q. If

![]() $\chi$

is a real Dirichlet character mod q, it is possible to obtain an upper bound on

$\chi$

is a real Dirichlet character mod q, it is possible to obtain an upper bound on

![]() $x_0(q)$

in (1·1). Indeed, combining Siegel’s lower bound for

$x_0(q)$

in (1·1). Indeed, combining Siegel’s lower bound for

![]() $L(1,\chi)$

with partial summation gives

$L(1,\chi)$

with partial summation gives

where

After applying the Pólya–Vinogradov inequality

![]() $S(t)\ll q^{1/2}\log{q}$

, we see that one may take

$S(t)\ll q^{1/2}\log{q}$

, we see that one may take

in (1·1).

In this paper, we obtain some new results which aim to quantitativley determine how negative the sums in (1·1) can get. To describe these results, we first introduce some notation from [

Reference Granville and Soundararajan7

]. Let

![]() ${\mathcal F},{\mathcal F}_1$

and

${\mathcal F},{\mathcal F}_1$

and

![]() ${\mathcal F}_0$

denote the set of completely multiplicative functions satisfying

${\mathcal F}_0$

denote the set of completely multiplicative functions satisfying

respectively. A quantitative form of the above question is to establish lower bounds for

We clearly have

and a quadratic reciprocity argument yields

In [ Reference Granville and Soundararajan7 ], Granville and Soundararajan showed that for sufficiently large x we have

and

The inequality (1·5) is not expected to be sharp and in [

Reference Granville and Soundararajan7

] the question of improving this result is raised. A consequence of (1·4), (1·5) and (1·6) is an upper and lower bound for each of

![]() $\delta,\delta_0$

and

$\delta,\delta_0$

and

![]() $\delta_1$

. We expect the lower bounds for

$\delta_1$

. We expect the lower bounds for

![]() $\delta,\delta_0$

and

$\delta,\delta_0$

and

![]() $\delta_1$

to be far from the truth and understanding their asymptotic behaviour remains a mystery. Our first result is an improvement on (1·5).

$\delta_1$

to be far from the truth and understanding their asymptotic behaviour remains a mystery. Our first result is an improvement on (1·5).

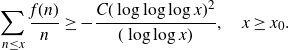

Theorem 1·1 There exist constants

![]() $C,x_0$

such that if

$C,x_0$

such that if

![]() $x\ge x_0$

then

$x\ge x_0$

then

Another route to explain why partial sums of multiplicative functions tend to be positive is to ask, given large x, how likely it is for

to be negative. We refer the reader to [ Reference Angelo and Xu1 , Reference Aymone, Heap and Zhao2 , Reference Kalmynin13 ] for a series of recent investigations into sign changes of partial sums of random multiplicative functions.

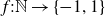

Let

![]() $(f(p))_{p\ prime}$

be a sequence of independent random variables taking values

$(f(p))_{p\ prime}$

be a sequence of independent random variables taking values

![]() $\pm 1$

with probability

$\pm 1$

with probability

![]() $1/2$

and put

$1/2$

and put

![]() $f(n)=\prod_{p^k\vert| n}f^k(p)$

for all

$f(n)=\prod_{p^k\vert| n}f^k(p)$

for all

![]() $n\ge 1.$

Given

$n\ge 1.$

Given

![]() $x\ge 1$

we let p(x) denote the probability that

$x\ge 1$

we let p(x) denote the probability that

Angelo and Xu [ Reference Angelo and Xu1 ] have recently shown that there exists an absolute constant c such that

We establish a somewhat stronger result.

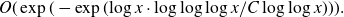

Theorem 1·2 With f as above, let p(x) denote the probability that (1·7) holds. There exists an absolute constant c such that

Granville and Soundararajan [

Reference Granville and Soundararajan7

] have shown that for any large x there is a function

![]() $f\,:\,\mathbb{N}\to \{-1,1\},$

for which (1·7) holds. It is possible to count trivial variations of Granville and Soundararajan’s construction [

Reference Granville and Soundararajan7

] and this produces a bound of the form

$f\,:\,\mathbb{N}\to \{-1,1\},$

for which (1·7) holds. It is possible to count trivial variations of Granville and Soundararajan’s construction [

Reference Granville and Soundararajan7

] and this produces a bound of the form

for some absolute constant

![]() $\eta$

. It is an interesting question to determine if there exists

$\eta$

. It is an interesting question to determine if there exists

![]() $\gamma\in \mathbb{R}$

such that

$\gamma\in \mathbb{R}$

such that

1·1. Main ideas

Roughly speaking, the proofs of both Theorem 1·1 and Theorem 1·2 start with a simple convolution identity (which is used in [

Reference Granville and Soundararajan7

] but not in [

Reference Angelo and Xu1

]) and our main novelty comes from introducing a bilinear structure allowing us to incorporate finer information on the distribution of f on large primes

![]() $x^v\le p\le x$

. More precisely, if

$x^v\le p\le x$

. More precisely, if

![]() $g(n)=\sum_{d\vert n}f(d)$

then

$g(n)=\sum_{d\vert n}f(d)$

then

and crucially

![]() $g(n)\ge 0$

for all

$g(n)\ge 0$

for all

![]() $n\ge 1.$

The remaining task is to produce satisfactory lower and upper bounds for the first and second terms on the right-hand side of (1·8). In the case of Theorem 1·1, arguing as in [

Reference Granville and Soundararajan7

] one may proceed further and write, as in Lemma 2·1

$n\ge 1.$

The remaining task is to produce satisfactory lower and upper bounds for the first and second terms on the right-hand side of (1·8). In the case of Theorem 1·1, arguing as in [

Reference Granville and Soundararajan7

] one may proceed further and write, as in Lemma 2·1

To upper bound the second term we use Halász type estimates due to Hall and Tenenbaum (Lemma 2·3) and more recent bounds due to Granville, Harper and Soundararajan (Lemma 2·2). At this stage we depart from the argument in [ Reference Granville and Soundararajan7 ] and key novelty in our approach lies in treating the lower bounds for the first sum. Here, rather than using a classical bound due to Hildebrand (as in [ Reference Granville and Soundararajan7 ]), we rely on a recent additive combinatorics result of Matomäki and Shao [ Reference Matomäki and Shao14 ], which allows us to prove the main technical Proposition 3·3. Roughly speaking, either the conditions to apply Matomäki and Shao’s result are satisfied or we can make a more efficient use of Halász type estimates.

We next oultine the proof of Theorem 1·2. Returning to (1·8), note that since

![]() $g(n)\ge 0$

, we have

$g(n)\ge 0$

, we have

and direct application of Bernstein’s inequality produces a simple lower bound

with an acceptable probability. We are thus left with estimating the probability of the event

We do so by a direct application of the majorant principle and this reduces the problem to upper bounding very high moments of the unweighted partial sums

The key observation here (see Proposition 5·6) is that since we are interested in the event where the partial sums are extremely large (in absolute value), it is more beneficial to work “close to the 1-line” rather than proceed, as in the work of Harper [

10

], close to “

![]() $1/2$

-line” (where the main interest is when partial sums have size around

$1/2$

-line” (where the main interest is when partial sums have size around

![]() $\sqrt{x}$

). This is accomplished by introducing a bilinear structure which allows us to combine bounds on the density of smooth numbers with Rankin’s trick to treat the contribution of large primes.

$\sqrt{x}$

). This is accomplished by introducing a bilinear structure which allows us to combine bounds on the density of smooth numbers with Rankin’s trick to treat the contribution of large primes.

We believe that Proposition 3·3 and Proposition 5·6 are of independent interest and could be useful in future investigations.

2. Preliminaries for the proof of Theorem 1·1

Here we collect several key facts, based on the argument of Granville and Soundararajan [ Reference Granville and Soundararajan7 ]. The following is [ Reference Granville and Soundararajan7 , proposition 3·1].

Lemma 2·1. Let

![]() $f\in {\mathcal F}$

and define

$f\in {\mathcal F}$

and define

![]() $g(n)=\sum_{d|n}f(d).$

Then

$g(n)=\sum_{d|n}f(d).$

Then

where

![]() $\gamma$

denotes Euler’s constant.

$\gamma$

denotes Euler’s constant.

We will use a version of Halász’s theorem in the form given by Granville and Soundararajan [ Reference Granville and Soundararajan6 , Theorem 2b].

Lemma 2·2. Let

![]() $f\in {\mathcal F}$

and define

$f\in {\mathcal F}$

and define

![]() $M=M(x)$

by

$M=M(x)$

by

where

![]() $F(s)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}{f(n)}/{n^{s}}$

for

$F(s)=\sum_{n=1}^{\infty}{f(n)}/{n^{s}}$

for

![]() $\Re{s}\gt1.$

Then

$\Re{s}\gt1.$

Then

where

![]() $\phi=\phi_f(x)$

is a real number in the range

$\phi=\phi_f(x)$

is a real number in the range

![]() $|t|\le \log{x}$

where the function

$|t|\le \log{x}$

where the function

![]() $t\rightarrow |F(1+1/\log{x}+it)|$

attains its maximum.

$t\rightarrow |F(1+1/\log{x}+it)|$

attains its maximum.

A result of Hall and Tenenbaum [ Reference Hall and Tenenbaum9 ] allows one to remove the dependence on t in Lemma 2·2 at the cost of a worse upper bound.

Lemma 2·3. For any

![]() $f\in {\mathcal F}$

we have

$f\in {\mathcal F}$

we have

\begin{equation*}\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\ll x\exp\left(-\kappa\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)}{p}\right),\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\ll x\exp\left(-\kappa\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)}{p}\right),\end{equation*}

with

![]() $\kappa=0.32867$

.

$\kappa=0.32867$

.

The following estimate is well known, for a proof see [ Reference Granville and Soundararajan5 , Equation 2.1.6].

Lemma 2·4 For any

![]() $x\ge 2$

and

$x\ge 2$

and

![]() $t\in \mathbb{R}$

, we have

$t\in \mathbb{R}$

, we have

\begin{align*}\sum_{p\le x}\frac{\Re(p^{it})}{p}=\log\log x+O(1) \quad {if} \quad |t|\le 1/\log{x}\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{p\le x}\frac{\Re(p^{it})}{p}=\log\log x+O(1) \quad {if} \quad |t|\le 1/\log{x}\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{p\le x}\frac{\Re(p^{it})}{p}=\log(1/|t|)+O(1) \quad {if} \quad \frac{1}{\log{x}}\le |t|\le 100\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{p\le x}\frac{\Re(p^{it})}{p}=\log(1/|t|)+O(1) \quad {if} \quad \frac{1}{\log{x}}\le |t|\le 100\end{align*}

and

\begin{align*}\left|\sum_{p\le x}\frac{\Re(p^{it})}{p} \right|\le \log\log(2+|t|)+O(1) \quad {if} \quad |t|\ge 100.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\left|\sum_{p\le x}\frac{\Re(p^{it})}{p} \right|\le \log\log(2+|t|)+O(1) \quad {if} \quad |t|\ge 100.\end{align*}

3. Lower bounds for nonnegative multiplicative functions

We next show how ideas from [ Reference Granville, Koukoulopoulos and Matomäki8 , Reference Matomäki and Shao14 ] may be used to obtain lower bounds for the function g(n) defined in Lemma 2·1. The main result of this section is Proposition 3·3.

The following is due to Matomäki and Shao [ Reference Matomäki and Shao14 , Hypothesis P] which improves on the work of Granville, Koukoulopoulos and Matomäki [ Reference Granville, Koukoulopoulos and Matomäki8 ].

Lemma 3·1 Fix

![]() $\lambda\in (0,1)$

. If x is sufficiently large and u,v satisfy

$\lambda\in (0,1)$

. If x is sufficiently large and u,v satisfy

and

![]() ${\mathcal P}$

is a subset of the primes in

${\mathcal P}$

is a subset of the primes in

![]() $(x^{1/v},x^{1/u}]$

with

$(x^{1/v},x^{1/u}]$

with

then there exists an integer

![]() $k\in [u,v]$

such that

$k\in [u,v]$

such that

where

![]() $\pi_v$

is a constant with

$\pi_v$

is a constant with

![]() $\pi_v=v^{-o(v)}$

as

$\pi_v=v^{-o(v)}$

as

![]() $v\rightarrow \infty$

. If u is fixed and

$v\rightarrow \infty$

. If u is fixed and

![]() $v\ge 1000u^2/\lambda^2$

, one can take

$v\ge 1000u^2/\lambda^2$

, one can take

![]() $k\le e^{-1/u}v$

.

$k\le e^{-1/u}v$

.

Our next result uses arguments in the spirit of [ Reference Hildebrand12 , p. 218].

Lemma 3·2 Let g be a nonnegative multiplicative function satisfying

for each prime power

![]() $p^{j}$

. For any real numbers

$p^{j}$

. For any real numbers

![]() $x,z\ge 1$

satisfying

$x,z\ge 1$

satisfying

for a sufficiently large absolute constant

![]() $C_1$

we have

$C_1$

we have

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n}\gg \exp\left(\sum_{p\le z}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n}\gg \exp\left(\sum_{p\le z}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right).\end{align*}

Proof. Let

![]() $\delta={1}/{\log{z}},$

and consider

$\delta={1}/{\log{z}},$

and consider

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n}&\ge \sum_{\substack{n\ge 1 \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n}-\sum_{\substack{n\gt x \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n} \\&\ge \prod_{p\le z}\left(1+\sum_{j\ge 1}\frac{g(p^{j})}{p^{j}} \right)-\frac{1}{x^{\delta}}\sum_{\substack{n\ge 1 \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n^{1-\delta}}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n}&\ge \sum_{\substack{n\ge 1 \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n}-\sum_{\substack{n\gt x \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n} \\&\ge \prod_{p\le z}\left(1+\sum_{j\ge 1}\frac{g(p^{j})}{p^{j}} \right)-\frac{1}{x^{\delta}}\sum_{\substack{n\ge 1 \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n^{1-\delta}}.\end{align*}

By (3·1)

\begin{align*}\log\left(\sum_{\substack{n\ge 1 \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n^{1-\delta}}\right)&=\sum_{p\le z}\frac{g(p)}{p}+O(1)\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\log\left(\sum_{\substack{n\ge 1 \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n^{1-\delta}}\right)&=\sum_{p\le z}\frac{g(p)}{p}+O(1)\end{align*}

which implies that for some absolute constant C

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n}&\gg \exp\left(\sum_{p\le z}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right)\left(1-C\exp\left(-\frac{\log{x}}{\log{z}}\right)\right) \gg \exp\left(\sum_{p\le z}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right)\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}\frac{g(n)}{n}&\gg \exp\left(\sum_{p\le z}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right)\left(1-C\exp\left(-\frac{\log{x}}{\log{z}}\right)\right) \gg \exp\left(\sum_{p\le z}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right)\end{align*}

assuming

![]() $C_1$

in (3·2) is large enough. This completes the proof.

$C_1$

in (3·2) is large enough. This completes the proof.

We are now in a position to establish the main result of this section.

proposition 3·3 Let

![]() $\varepsilon\gt0$

be sufficiently small,

$\varepsilon\gt0$

be sufficiently small,

![]() $f\in {\mathcal F}$

and define

$f\in {\mathcal F}$

and define

![]() $g(n)=\sum_{d|n}f(d).$

For

$g(n)=\sum_{d|n}f(d).$

For

![]() $x\ge 2$

and

$x\ge 2$

and

![]() $0\lt\delta \lt1$

which may depend on x, let

$0\lt\delta \lt1$

which may depend on x, let

![]() ${\mathcal P}_{\delta}$

denote the set

${\mathcal P}_{\delta}$

denote the set

Suppose that for some v satisfying

we have

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x^{1/v}\le p \le x}}\frac{1}{p}\ge 1+\varepsilon.\end{align}

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x^{1/v}\le p \le x}}\frac{1}{p}\ge 1+\varepsilon.\end{align}

Then

\begin{align*}\sum_{n\le x}g(n) \gg \varepsilon^4\left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\exp\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{f(p)}{p}\right)x.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{n\le x}g(n) \gg \varepsilon^4\left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\exp\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{f(p)}{p}\right)x.\end{align*}

Proof. Let

![]() $G=\sum_{n\le x}g(n),$

and define

$G=\sum_{n\le x}g(n),$

and define

so that

\begin{align*}G& \ge \sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}g(a)\sum_{\substack{b\le x/a \\ p|b \implies p\in {\mathcal B}}}g(b).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}G& \ge \sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}g(a)\sum_{\substack{b\le x/a \\ p|b \implies p\in {\mathcal B}}}g(b).\end{align*}

If

![]() $p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta},$

then since f is completely multiplicative, for any integer

$p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta},$

then since f is completely multiplicative, for any integer

![]() $j\ge 1$

we have

$j\ge 1$

we have

and hence

since

This implies that

\begin{align}G\ge \sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}g(a)\sum_{\substack{b\le x/a \\ p|b \implies p\in {\mathcal B}}}(1-\delta)^{\Omega(b)},\end{align}

\begin{align}G\ge \sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}g(a)\sum_{\substack{b\le x/a \\ p|b \implies p\in {\mathcal B}}}(1-\delta)^{\Omega(b)},\end{align}

where

![]() $\Omega(n)$

counts the number of prime factors (with multiplicity) of an integer n and we have used the inequality

$\Omega(n)$

counts the number of prime factors (with multiplicity) of an integer n and we have used the inequality

![]() $\omega(n)\le \Omega(n)$

, where

$\omega(n)\le \Omega(n)$

, where

![]() $\omega(n)$

counts the number of distinct prime factors of an integer n.

$\omega(n)$

counts the number of distinct prime factors of an integer n.

Our next step is to apply Lemma 3·1 to the inner summation over b. This requires verifying for each

the following lower bound holds

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ (x/a)^{1/v}\le p \le x/a}}\frac{1}{p}\ge 1+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\end{align}

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ (x/a)^{1/v}\le p \le x/a}}\frac{1}{p}\ge 1+\frac{\varepsilon}{2}.\end{align}

By (3·3) and the fact that

we have

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ (x/a)^{1/v}\le p \le x/a}}\frac{1}{p}\ge \sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x^{1/v}\le p \le x}}\frac{1}{p}-\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x/a\le p \le x }}\frac{1}{p}\ge 1+\varepsilon-\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x/a\le p \le x }}\frac{1}{p}\end{align}

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ (x/a)^{1/v}\le p \le x/a}}\frac{1}{p}\ge \sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x^{1/v}\le p \le x}}\frac{1}{p}-\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x/a\le p \le x }}\frac{1}{p}\ge 1+\varepsilon-\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x/a\le p \le x }}\frac{1}{p}\end{align}

and by (3·6)

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x/a\le p \le x }}\frac{1}{p}&\le \log\log{x}-\log\log{(x/a)}+o(1) \\ & \le \log\log{x}-\log\log{(x^{1-\varepsilon/5})}\le \frac{\varepsilon}{4}+o(1)\cdot\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta} \\ x/a\le p \le x }}\frac{1}{p}&\le \log\log{x}-\log\log{(x/a)}+o(1) \\ & \le \log\log{x}-\log\log{(x^{1-\varepsilon/5})}\le \frac{\varepsilon}{4}+o(1)\cdot\end{align*}

Combining the above with (3·8) implies (3·7). By Lemma 3·1, for each a satisfying (3·6), if v satisfies

then there exists an integer

![]() $k\le {v}/{e}$

such that

$k\le {v}/{e}$

such that

Hence

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{b\le x/a \\ p|b \implies p\in {\mathcal B}}}(1-\delta)^{\Omega(b)}&\ge v^{o(v)}\left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{k}\frac{x}{a \log{x}} \\ & \ge \left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\frac{x}{a \log{x}},\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{b\le x/a \\ p|b \implies p\in {\mathcal B}}}(1-\delta)^{\Omega(b)}&\ge v^{o(v)}\left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{k}\frac{x}{a \log{x}} \\ & \ge \left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\frac{x}{a \log{x}},\end{align*}

which combined with (3·5) implies

\begin{align}G\ge \left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\frac{x}{\log{x}}\sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}\frac{g(a)}{a}.\end{align}

\begin{align}G\ge \left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\frac{x}{\log{x}}\sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}\frac{g(a)}{a}.\end{align}

Recalling (3·4)

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}\frac{g(a)}{a}=\sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\le x^{1/v}}}\frac{g(a)}{a}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}\frac{g(a)}{a}=\sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\le x^{1/v}}}\frac{g(a)}{a}.\end{align*}

If

![]() $\varepsilon$

is sufficiently small then by (3·9) the condition that

$\varepsilon$

is sufficiently small then by (3·9) the condition that

![]() $C_1$

in (3·2) is sufficiently large is satisfied. Hence we may apply Lemma 3·2 to deduce that

$C_1$

in (3·2) is sufficiently large is satisfied. Hence we may apply Lemma 3·2 to deduce that

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}\frac{g(a)}{a}\gg \exp\left(\sum_{p\le x^{\varepsilon^2/40000}}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{a\le x^{\varepsilon/5} \\ p|a \implies p\in {\mathcal A}}}\frac{g(a)}{a}\gg \exp\left(\sum_{p\le x^{\varepsilon^2/40000}}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right).\end{align*}

Using (3·10) gives

\begin{align*}G\gg \left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\frac{x}{\log{x}}\exp\left(\sum_{p\le x^{\varepsilon^2/40000}}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right),\end{align*}

\begin{align*}G\gg \left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\frac{x}{\log{x}}\exp\left(\sum_{p\le x^{\varepsilon^2/40000}}\frac{g(p)}{p}\right),\end{align*}

and the result follows after noting

\begin{align*}\sum_{p\le x^{\varepsilon^2/40000}}\frac{g(p)}{p}&\ge \sum_{p\le x}\frac{g(p)}{p}+2\log{\varepsilon}+O(1) \\&\ge \log\log{x}+\sum_{p\le x}\frac{f(p)}{p}+4\log{\varepsilon}+O(1).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{p\le x^{\varepsilon^2/40000}}\frac{g(p)}{p}&\ge \sum_{p\le x}\frac{g(p)}{p}+2\log{\varepsilon}+O(1) \\&\ge \log\log{x}+\sum_{p\le x}\frac{f(p)}{p}+4\log{\varepsilon}+O(1).\end{align*}

4. Proof of Theorem 1·1

First note we may assume that

since otherwise, for any constant C there exists

![]() $x_0$

such that if

$x_0$

such that if

![]() $x\ge x_0$

then

$x\ge x_0$

then

\begin{align*}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\gt -\frac{1}{(\log{x})^{1/6}}\gt -\frac{C(\log\log\log{x})^2}{(\log\log{x})}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\gt -\frac{1}{(\log{x})^{1/6}}\gt -\frac{C(\log\log\log{x})^2}{(\log\log{x})}.\end{align*}

By (4·1) and Lemma 2·1, for sufficiently large x we have

\begin{align*}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}&\ge \frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)+(1-\gamma)\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}f(n)-\frac{1}{2(\log{x})^{1/6}} \\&\ge \frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)+(1-\gamma)\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}f(n)+\frac{1}{2}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n},\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}&\ge \frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)+(1-\gamma)\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}f(n)-\frac{1}{2(\log{x})^{1/6}} \\&\ge \frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)+(1-\gamma)\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}f(n)+\frac{1}{2}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n},\end{align*}

which implies that

\begin{align}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge 2\left(\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)-\frac{(1-\gamma)}{x}\left|\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right|\right).\end{align}

\begin{align}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge 2\left(\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)-\frac{(1-\gamma)}{x}\left|\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right|\right).\end{align}

Hence from Lemma 2·2, there exists an absolute constant

![]() $C_1$

such that

$C_1$

such that

\begin{align}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge 2\left(\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)-\frac{C_1(1+M)e^{-M}}{1+|t|}\right),\end{align}

\begin{align}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge 2\left(\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)-\frac{C_1(1+M)e^{-M}}{1+|t|}\right),\end{align}

where M is defined by

for some

![]() $|t|\ll \log{x}.$

Let

$|t|\ll \log{x}.$

Let

![]() $\varepsilon\gt0$

be small, define

$\varepsilon\gt0$

be small, define

for a suitable absolute constant C and put

Consider the set

We distinguish between two cases. Either

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{1}{p}\le 1+\varepsilon\end{align}

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{1}{p}\le 1+\varepsilon\end{align}

or

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{1}{p}\gt 1+\varepsilon.\end{align}

\begin{align}\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{1}{p}\gt 1+\varepsilon.\end{align}

Suppose first that (4·7) holds and consider

\begin{align*}\Re\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)&\ge \Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\not \in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)+O(1) \\& \ge \Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\not \in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{1+p^{-it}}{p}\right)-\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\not \in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{|1+f(p)|}{p}+O(1).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\Re\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)&\ge \Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\not \in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)+O(1) \\& \ge \Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\not \in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{1+p^{-it}}{p}\right)-\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x \\ p\not \in {\mathcal P}_{\delta}}}\frac{|1+f(p)|}{p}+O(1).\end{align*}

If

![]() $p\not \in {\mathcal P}_{\delta},$

then recalling (4·6)

$p\not \in {\mathcal P}_{\delta},$

then recalling (4·6)

which implies for such values of p

\begin{align*}\Re\left(1-f(p)p^{-it}\right)&=\Re\left(1+p^{-it}\right)-\Re\left((f(p)+1)p^{-it}\right) \\&\ge \Re\left(1+p^{-it}\right)-\varepsilon_1\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\Re\left(1-f(p)p^{-it}\right)&=\Re\left(1+p^{-it}\right)-\Re\left((f(p)+1)p^{-it}\right) \\&\ge \Re\left(1+p^{-it}\right)-\varepsilon_1\end{align*}

and consequently by (4·7), we have

\begin{align}\Re\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)&\ge \Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x }}\frac{1+p^{-it}}{p}\right)-\varepsilon_1 \log{v}+O(1).\end{align}

\begin{align}\Re\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)&\ge \Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x }}\frac{1+p^{-it}}{p}\right)-\varepsilon_1 \log{v}+O(1).\end{align}

We next consider two subcases depending on the size of t relative to x. Suppose first that

By Lemma 2·4

\begin{align*}\left|\Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x }}\frac{p^{-it}}{p}\right)\right|\le 2\log\log{|t|}+O(1)\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\left|\Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x }}\frac{p^{-it}}{p}\right)\right|\le 2\log\log{|t|}+O(1)\end{align*}

and hence from (4·9)

\begin{align*}\Re\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)&\ge (1-\varepsilon_1) \log{v}+O(\log\log{|t|}).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\Re\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)&\ge (1-\varepsilon_1) \log{v}+O(\log\log{|t|}).\end{align*}

After recalling (4·5) and (4·6), we get

which when combined with (4·3), (4·4) and the bound

gives

\begin{align}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge -\frac{C(\log\log\log{x})^2}{(\log\log{x})}\frac{(\log{|t|})^{O(1)}}{|t|}\ge -\frac{C'(\log\log\log{x})^2}{(\log\log{x})}\end{align}

\begin{align}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge -\frac{C(\log\log\log{x})^2}{(\log\log{x})}\frac{(\log{|t|})^{O(1)}}{|t|}\ge -\frac{C'(\log\log\log{x})^2}{(\log\log{x})}\end{align}

for some absolute constant C’. If

![]() $|t|\le 100$

then by Lemma 2·4

$|t|\le 100$

then by Lemma 2·4

\begin{equation*}\Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x }}\frac{p^{-it}}{p}\right)\ge -C'\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\Re\left(\sum_{\substack{x^{1/v}\le p \le x }}\frac{p^{-it}}{p}\right)\ge -C'\end{equation*}

for some absolute constant C’. Hence from (4·9)

\begin{align*}\Re\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)&\ge (1-\varepsilon_1)\log{v}+O(1).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\Re\left(\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)p^{-it}}{p}\right)&\ge (1-\varepsilon_1)\log{v}+O(1).\end{align*}

After recalling (4·5) and (4·6), we get

which when combined with (4·3), (4·4) and the fact that

![]() $g(n)\ge 0$

, gives

$g(n)\ge 0$

, gives

\begin{align}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge -\frac{C'(\log\log\log{x})^2}{(\log\log{x})}\end{align}

\begin{align}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge -\frac{C'(\log\log\log{x})^2}{(\log\log{x})}\end{align}

for some absolute constant C ′. This completes our analysis of the case when (4·7) holds. Suppose next that (4·8) holds. By (4·3) and Proposition 3·3

\begin{align*}\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)\gg \varepsilon^4\left(\frac{(1-\delta)}4{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}(\log{x})\exp\left(-\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)}{p}\right) .\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\frac{1}{x}\sum_{n\le x}g(n)\gg \varepsilon^4\left(\frac{(1-\delta)}4{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}(\log{x})\exp\left(-\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)}{p}\right) .\end{align*}

Recalling (4·6), we have

\begin{align*}\left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\log{x}&\gg \exp\left(-\frac{v(1+o(1))\log{(v/\varepsilon_1)}}{e}\right)(\log{x})^{1-1/e} \\&\gg (\log{x})^{1-1/e+o(1)}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\left(\frac{(1-\delta)}{v}\right)^{v(1+o(1))/e}\log{x}&\gg \exp\left(-\frac{v(1+o(1))\log{(v/\varepsilon_1)}}{e}\right)(\log{x})^{1-1/e} \\&\gg (\log{x})^{1-1/e+o(1)}.\end{align*}

Upon applying Lemma 2·3 and (4·2) we deduce

\begin{align*}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge C_1(\log{x})^{1-o(1)}\exp\left(-\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)}{p}\right)-C_2\exp\left(-\kappa\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)}{p}\right),\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{n\le x}\frac{f(n)}{n}\ge C_1(\log{x})^{1-o(1)}\exp\left(-\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)}{p}\right)-C_2\exp\left(-\kappa\sum_{p\le x}\frac{1-f(p)}{p}\right),\end{align*}

for some absolute constants

![]() $C_1,C_2$

. Optimising the function

$C_1,C_2$

. Optimising the function

subject to the restriction

![]() $u\ge 0$

implies

$u\ge 0$

implies

and combined with (4·10) we complete the proof.

5. Preliminaries for the proof of Theorem 1·2

We next present some preliminary results required for the proof of Theorem 1·2. The following is known as Bernstein’s inequality.

Lemma 5·1 Let

![]() $X_1,\dots,X_n$

be a sequence of independent random variables satisfying

$X_1,\dots,X_n$

be a sequence of independent random variables satisfying

For all

![]() $t\gt0$

we have

$t\gt0$

we have

\begin{align*}P\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}X_i\ge t\right)\le \exp\left(-\frac{t^2/2}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\mathbb{E}(X_i^2)+Mt/3}\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}P\left(\sum_{i=1}^{n}X_i\ge t\right)\le \exp\left(-\frac{t^2/2}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\mathbb{E}(X_i^2)+Mt/3}\right).\end{align*}

For

![]() $1\le z \le w$

define

$1\le z \le w$

define

\begin{equation*}\Psi(w,z)=\sum_{\substack{n\le w \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}1.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\Psi(w,z)=\sum_{\substack{n\le w \\ p|n \implies p\le z}}1.\end{equation*}

The following is due to Canfield, Erdös and Pomerance [ Reference Canfield, Erdös and Pomerance4 , Corollary p. 15].

Lemma 5·2 Let

![]() $1\le z\le w$

be real numbers and define

$1\le z\le w$

be real numbers and define

If

then

Recall that

![]() ${\mathcal F}_1$

denotes the space of completely multiplicative functions f satisfying

${\mathcal F}_1$

denotes the space of completely multiplicative functions f satisfying

![]() $f(p)=\pm 1$

for

$f(p)=\pm 1$

for

![]() $p\le x.$

Let

$p\le x.$

Let

![]() $\mu$

denote the counting measure on

$\mu$

denote the counting measure on

![]() ${\mathcal F}_1$

, normalised so that

${\mathcal F}_1$

, normalised so that

and let

![]() $\mathbb{E}$

denote expectation with respect to

$\mathbb{E}$

denote expectation with respect to

![]() $\mu$

. We will make considerable use of the majorant principle.

$\mu$

. We will make considerable use of the majorant principle.

Lemma 5·3 Let q be an even integer and

![]() $a_n$

and

$a_n$

and

![]() $b_n$

be two sequences of real numbers satisfying

$b_n$

be two sequences of real numbers satisfying

Then

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}a_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right]\le \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}b_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right].\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}a_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right]\le \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}b_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right].\end{align*}

Proof. Recall that

![]() $f(p)=\pm 1$

with probability

$f(p)=\pm 1$

with probability

![]() $1/2$

. If q is an even integer, then for any real numbers

$1/2$

. If q is an even integer, then for any real numbers

![]() $a_n$

we have

$a_n$

we have

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}a_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right]=\sum_{\substack{1\le n_1,\cdots,n_{q} \le x \\ \exists s\in \mathbb{N} \ : \ n_1n_2\cdots n_{q}=s^2}}a_{n_1}\ {\cdots}\ {a_{n_{q}}}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}a_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right]=\sum_{\substack{1\le n_1,\cdots,n_{q} \le x \\ \exists s\in \mathbb{N} \ : \ n_1n_2\cdots n_{q}=s^2}}a_{n_1}\ {\cdots}\ {a_{n_{q}}}.\end{align*}

Hence if

![]() $|a_n|\le b_n$

then

$|a_n|\le b_n$

then

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}a_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right]\le \sum_{\substack{1\le n_1,\cdots,n_{q} \le x \\ \exists s\in \mathbb{N} \ : \ n_1n_2\ {\cdots}\ n_{q}=s^2}}b_{n_1}\cdots b_{n_q}=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}b_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right].\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}a_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right]\le \sum_{\substack{1\le n_1,\cdots,n_{q} \le x \\ \exists s\in \mathbb{N} \ : \ n_1n_2\ {\cdots}\ n_{q}=s^2}}b_{n_1}\cdots b_{n_q}=\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}b_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right].\end{align*}

A particular consequence of Lemma 5·3 is as follows.

Corollary 5·4 Let q be an even integer and

![]() $c_n$

a sequence of nonnegative real numbers. For any

$c_n$

a sequence of nonnegative real numbers. For any

![]() ${\mathcal A},{\mathcal B}\subseteq\mathbb{N}$

satisfying

${\mathcal A},{\mathcal B}\subseteq\mathbb{N}$

satisfying

![]() ${\mathcal A}\subseteq {\mathcal B}$

, we have

${\mathcal A}\subseteq {\mathcal B}$

, we have

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ n\in {\mathcal A}}}c_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right]\le \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ n\in {\mathcal B}}}c_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right].\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ n\in {\mathcal A}}}c_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right]\le \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ n\in {\mathcal B}}}c_nf(n)\right)^{q}\right].\end{align*}

Proof. This follows from Lemma 5·3 taking

\begin{equation*}a_n=\begin{cases}c_n \quad \text{if $n\in {\mathcal A}$} \\ 0 \quad \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}a_n=\begin{cases}c_n \quad \text{if $n\in {\mathcal A}$} \\ 0 \quad \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\end{equation*}

and

\begin{equation*}b_n=\begin{cases}c_n \quad \text{if $n\in {\mathcal B}$} \\ 0 \quad \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}b_n=\begin{cases}c_n \quad \text{if $n\in {\mathcal B}$} \\ 0 \quad \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\end{equation*}

after noting the condition

![]() $a_n\le b_n$

follows from the assumption that

$a_n\le b_n$

follows from the assumption that

![]() ${\mathcal A}\subseteq {\mathcal B}$

.

${\mathcal A}\subseteq {\mathcal B}$

.

Our main input for Theorem 1·2 is the following.

Corollary 5·5. For any

![]() $M\gt0$

, there exists a constant

$M\gt0$

, there exists a constant

![]() $C\gt0$

such that for sufficiently large x

$C\gt0$

such that for sufficiently large x

\begin{align*}\mu\left(\left\{ f\in {\mathcal F}_1 \ : \ \left|\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right|\ge \frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right\} \right)\le \exp \left(-\exp\left(\frac{(\log \log \log{x})\log{x}}{C\log\log{x}}\right)\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mu\left(\left\{ f\in {\mathcal F}_1 \ : \ \left|\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right|\ge \frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right\} \right)\le \exp \left(-\exp\left(\frac{(\log \log \log{x})\log{x}}{C\log\log{x}}\right)\right).\end{align*}

Corollary 5·5 is a consequence of the following moment inequality.

proposition 5·6. For any

![]() $C \gt 0$

, positive real number x sufficiently large in terms of C and any even integer q, we have

$C \gt 0$

, positive real number x sufficiently large in terms of C and any even integer q, we have

\begin{align*}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]\right)^{1/q}& \ll x^{7/8}\exp\left(\left(q\exp\left(-\frac{(\log\log\log{x})\log{x}}{C\log\log{x}}\right)+2\log\log{x}\right)\right) \\&\quad+\left( \frac{x}{(\log{x})^{C/4-1}}\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\left(\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]\right)^{1/q}& \ll x^{7/8}\exp\left(\left(q\exp\left(-\frac{(\log\log\log{x})\log{x}}{C\log\log{x}}\right)+2\log\log{x}\right)\right) \\&\quad+\left( \frac{x}{(\log{x})^{C/4-1}}\right).\end{align*}

We first show that Proposition 5·6 implies Corollary 5·5 which in turn implies Theorem 1·2. We then prove Proposition 5·6 in Section 5·3.

5·1. Deduction of Theorem 1·2 from Corollary 5·5:

Let

![]() $g(n)=\sum_{d\vert n}f(d)$

and apply (1·8) to get

$g(n)=\sum_{d\vert n}f(d)$

and apply (1·8) to get

By Lemma 5·1, the probability that

is bounded by

Since

![]() $g(n)\ge 0$

for all

$g(n)\ge 0$

for all

![]() $n\ge 1,$

this implies that for sufficiently large x the probability that

$n\ge 1,$

this implies that for sufficiently large x the probability that

is equal to

After applying Corollary 5·5 with

![]() $M=1/2$

the desired result follows.

$M=1/2$

the desired result follows.

5·2. Deduction of Corollary 5·5 from Proposition 5·6

By Lemma 5·3, for any even integer q

\begin{align}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]\le \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right].\end{align}

\begin{align}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]\le \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right].\end{align}

We next use Markov’s inequality, which states that for a nonnegative random variable X and real number

![]() $y\gt0$

we have

$y\gt0$

we have

Applying this with

\begin{equation*}X=\left|\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right|^{q}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}X=\left|\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right|^{q}\end{equation*}

and

we get

\begin{align*}\mu\left(\left\{ f\in {\mathcal F}_1 \ : \ \left|\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right|\ge \frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right\} \right)\le \left(\frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right)^{-q}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mu\left(\left\{ f\in {\mathcal F}_1 \ : \ \left|\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right|\ge \frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right\} \right)\le \left(\frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right)^{-q}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]\end{align*}

which by (5·2) implies that

\begin{align*}\mu\left(\left\{ f\in {\mathcal F}_1 \ : \ \left|\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right|\ge \frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right\} \right)\le \left(\frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right)^{-q}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right].\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mu\left(\left\{ f\in {\mathcal F}_1 \ : \ \left|\sum_{n\le x}\left\{\frac{x}{n}\right\}f(n)\right|\ge \frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right\} \right)\le \left(\frac{M}{\log{x}}x\right)^{-q}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right].\end{align*}

Applying Proposition 5·6 with the choice of parameter

completes the proof of Corollary 5·5.

5·3. Proof of Proposition 5·6

Let

where C is a sufficiently large absolute constant. Since

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{m\le x}}f(m)=\sum_{\substack{n\ell\le x \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ p|\ell \implies p \lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)f(n)=\sum_{j\le \log{x}+1}\sum_{\substack{n\ell\le x \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ p|\ell \implies p \lt x^{\varepsilon} \\ e^{j}\le \ell \lt e^{j+1}}}f(\ell)f(n),\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{m\le x}}f(m)=\sum_{\substack{n\ell\le x \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ p|\ell \implies p \lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)f(n)=\sum_{j\le \log{x}+1}\sum_{\substack{n\ell\le x \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ p|\ell \implies p \lt x^{\varepsilon} \\ e^{j}\le \ell \lt e^{j+1}}}f(\ell)f(n),\end{align*}

by Minkowski’s inequality and the majorant principle to ignore the condition

![]() $n\ell \le x$

we get

$n\ell \le x$

we get

\begin{align*} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\le \sum_{j\le \log{x}+1}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\le x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\end{align*}

\begin{align*} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\le \sum_{j\le \log{x}+1}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\le x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\end{align*}

and hence

\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\le S_1+S_2,\end{align}

\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\le S_1+S_2,\end{align}

where

\begin{align}S_1=\sum_{j\le \log{x}/2}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\end{align}

\begin{align}S_1=\sum_{j\le \log{x}/2}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\end{align}

and

\begin{align*}S_2=\sum_{\log{x}/2\lt j\le \log{x}+1}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}S_2=\sum_{\log{x}/2\lt j\le \log{x}+1}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

Consider first

![]() $S_2$

. Taking a maximum over the outer summation, we see that there exists

$S_2$

. Taking a maximum over the outer summation, we see that there exists

![]() $j\ge \log{x}/2$

such that

$j\ge \log{x}/2$

such that

\begin{align*}S_2\le (\log{x})\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}S_2\le (\log{x})\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

Define

![]() $\beta$

by

$\beta$

by

![]() $x^{\beta}=e^{j+1}$

, and note that

$x^{\beta}=e^{j+1}$

, and note that

![]() $\beta\ge 1/2.$

Since f is completley multiplicative,

$\beta\ge 1/2.$

Since f is completley multiplicative,

![]() $|f(n)|\le 1$

for each

$|f(n)|\le 1$

for each

![]() $n\in \mathbb{N}$

and hence

$n\in \mathbb{N}$

and hence

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\ll x^{1-\beta}\Psi(x^{\beta},x^{\varepsilon}).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon}}}f(n)\sum_{\substack{\ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}f(\ell)\ll x^{1-\beta}\Psi(x^{\beta},x^{\varepsilon}).\end{align*}

This implies

We apply Lemma 5·2 with

Define

and note that by (5·3)

![]() $u\rightarrow \infty$

and

$u\rightarrow \infty$

and

Combining (5·1) and (5·6) gives

By (5·3), if x if sufficiently large in terms of C then

and hence

Consequently, using (5·4)

\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\ll S_1+\frac{x}{(\log{x})^{C-1}}.\end{align}

\begin{align} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{n\le x}f(n)\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\ll S_1+\frac{x}{(\log{x})^{C-1}}.\end{align}

We now turn our attention to estimating

![]() $S_1.$

We recall (5·5) and write

$S_1.$

We recall (5·5) and write

\begin{align*}S_1=\sum_{j\le \log{x}/2}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ \ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}(\ell n^{3/4})\frac{f(n\ell)}{n^{3/4}\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}S_1=\sum_{j\le \log{x}/2}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ \ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}(\ell n^{3/4})\frac{f(n\ell)}{n^{3/4}\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

If

![]() $n,\ell$

satisfy conditions in the above summation, we have

$n,\ell$

satisfy conditions in the above summation, we have

and hence Lemma 5·3 implies

\begin{align*}S_1\ll x^{3/4}\sum_{j\le \log{x}/2}e^{j/4}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ \ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}\frac{f(n\ell)}{n^{3/4}\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}S_1\ll x^{3/4}\sum_{j\le \log{x}/2}e^{j/4}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ \ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}\frac{f(n\ell)}{n^{3/4}\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

By Corollary 5·4

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ \ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}\frac{f(n\ell)}{n^{3/4}\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\ll \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x }}\frac{f(n)}{n^{3/4}}\sum_{\substack{\ell \ge 1 \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}\frac{f(\ell)}{\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x/e^{j} \\ p|n \implies p\ge x^{\varepsilon} \\ \ell \le e^{j+1} \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}\frac{f(n\ell)}{n^{3/4}\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\ll \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x }}\frac{f(n)}{n^{3/4}}\sum_{\substack{\ell \ge 1 \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}\frac{f(\ell)}{\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\end{align*}

and hence by another application of Corollary 5·4

\begin{align*}S_1&\ll x^{7/8}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x }}\frac{f(n)}{n^{3/4}}\sum_{\substack{\ell \ge 1 \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}\frac{f(\ell)}{\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q} \\& \ll x^{7/8}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{p\le x^{\varepsilon}}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*}S_1&\ll x^{7/8}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\sum_{\substack{n\le x \\ p|n \implies x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x }}\frac{f(n)}{n^{3/4}}\sum_{\substack{\ell \ge 1 \\ p|\ell \implies p\lt x^{\varepsilon}}}\frac{f(\ell)}{\ell}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q} \\& \ll x^{7/8}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{p\le x^{\varepsilon}}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]^{1/q}.\end{align*}

We next expand the expectation as a product to get

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]&\le \exp(O(q))\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1+\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)\right)^{q} \right] .\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]&\le \exp(O(q))\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1+\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)\right)^{q} \right] .\end{align*}

Observe that

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{p\le x}\left(1+\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)\right)^{q} \right]=\prod_{p\le x}\frac{1}{2}\left( \left(1+\frac{1}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{q}+\left(1-\frac{1}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{q} \right)\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{p\le x}\left(1+\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)\right)^{q} \right]=\prod_{p\le x}\frac{1}{2}\left( \left(1+\frac{1}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{q}+\left(1-\frac{1}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{q} \right)\end{align*}

and since for any real number a

the above implies

\begin{align*}\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\frac{1}{2}\left( \left(1+\frac{1}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{q}+\left(1-\frac{1}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{q} \right)&\le \prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p \le x}\frac{\exp(q/p^{3/4})+\exp(-q/p^{3/4})}{2} \\&\le \prod_{x^{\varepsilon\le p \le x}}\exp\left(\frac{q^2}{p^{3/2}}\right) \\&\le \exp\left(\frac{q^2}{x^{\varepsilon/2}}\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\frac{1}{2}\left( \left(1+\frac{1}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{q}+\left(1-\frac{1}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{q} \right)&\le \prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p \le x}\frac{\exp(q/p^{3/4})+\exp(-q/p^{3/4})}{2} \\&\le \prod_{x^{\varepsilon\le p \le x}}\exp\left(\frac{q^2}{p^{3/2}}\right) \\&\le \exp\left(\frac{q^2}{x^{\varepsilon/2}}\right).\end{align*}

The above inequalities imply that

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]&\le \exp\left(\frac{q^2}{x^{\varepsilon/2}}+O(q)\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]&\le \exp\left(\frac{q^2}{x^{\varepsilon/2}}+O(q)\right).\end{align*}

After recalling (5·3), the latter yields

\begin{align}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]&\le \exp\left(q^2\exp\left(-\frac{(\log\log\log{x})(\log{x})}{4C\log\log{x}}\right)+O(q)\right).\end{align}

\begin{align}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{x^{\varepsilon}\le p\le x}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p^{3/4}}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]&\le \exp\left(q^2\exp\left(-\frac{(\log\log\log{x})(\log{x})}{4C\log\log{x}}\right)+O(q)\right).\end{align}

We finally deduce the bound

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{p\le x^{\varepsilon}}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]&\ll \exp\left(O(q)+q\sum_{p\le x^{\varepsilon}}\frac{1}{p}\right) \\ &\le \exp\left(O(q)+q\log \log{x}\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*}\mathbb{E}\left[\left(\prod_{p\le x^{\varepsilon}}\left(1-\frac{f(p)}{p}\right)^{-1}\right)^{q} \right]&\ll \exp\left(O(q)+q\sum_{p\le x^{\varepsilon}}\frac{1}{p}\right) \\ &\le \exp\left(O(q)+q\log \log{x}\right).\end{align*}

Combining the above with (5·5) and (5·8), we get

and the result follows from (5·7) after renaming the constant C.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Yu-Chen Sun for his comments. We are also grateful to the referee for corrections and very insightful comments. The first author is currently supported by the Australian Research Council DE220100859 and part of this work was carried out while both authors were visiting the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics, Bonn. We thank MPIM (Bonn) for providing excellent working conditions and a Focused Research Grant (HIMR).