Introduction

A significant increase in nonprofit activities in Asian countries reflects the essential roles NPOsFootnote 1 now play in that region's development and political change processes (e.g., Kim, Reference Kim2014; Kim & Kim, Reference Kim and Kim2018). Multiple forces are driving the recent nonprofit developments in Asia. First, the awareness of human rights and various international movements drive the formation and growth of nonprofit activities and participation (e.g., Anheier & Themudo, Reference Anheier and Themudo2005). Second, public services are increasingly delivered through civil society organizations (CSO, thus legitimizing the status of CSOs (e.g., Lee & Haque, Reference Lee and Haque2008). Third, nonprofit organizations are essential for incubating social innovations and policy changes (e.g., Chiavacci et al., Reference Chiavacci, Grano and Obinger2020).

Meanwhile, essential theories or frameworks about the relationship between the development of democracy and NPOs, including social capital theory (Lee, Reference Lee2010; Terbish & Rawsthorne, Reference Terbish and Rawsthorne2020), social networks (Suebvises, Reference Suebvises2018), and advocacy (Hillman, Reference Hillman2017; Kalicki, Reference Kalicki2019; Wahn, Reference Wahn2015), help to understand the development of nonprofits in Asia. An essential role of NPOs is to provide engagement opportunities for people to participate in reforms, movements, and the resolution of collective issues. It is essential to understand how NPOs have fostered participation and civic engagement opportunities and how NPO participation has affected political participation in countries at different stages of democratization.

However, while studies show that the number of NPOs is growing in Asia, NPOs supported and founded by a particular political party or regime might potentially reduce political or democratic activities, such as advocacy (Ganesan, Reference Ganesan2017; Shin & Lee, Reference Shin and Lee2017). Furthermore, studies have reported that governments began to use the "rule of law" and regulations as a policy tool to tighten civil society and limit nonprofit participation in the public policy-making process, especially in an authoritarian regime (e.g., Curley, Reference Curley2018). Different political regime types affect the environment in which a nonprofit organization operates in Asia (Sidel, Reference Sidel2008, Reference Sidel2010), providing a unique opportunity to understand such variation.

Although previous studies have generated a wealth of knowledge, most have focused on specific case studies. Most Asian NPO research is reported through case studies, and there is a need to empirically examine the relationship between NPO participation and democratic development. Therefore, there is a need to empirically compare information across Asian countries to develop a theoretical framework for assessing the effects of NPO participation.

This study investigates how NPO participation correlates with political participation in Asian countries. Specifically, we ask the following question: does NPO participation foster active participation in the community and political activities in Asia? How do different political regimes affect such relationships? Using the Asian Barometer Survey, we first map the nonprofit affiliations in different countries and areas, including five types of nonprofits (grouping from eighteen different types of nonprofit affiliations). Then, we empirically examine the correlation between nonprofit participation and various forms of political participation as compositions of contact with elected officials, higher-level officers, community leaders, influential leaders and media, problem resolution, petitions, protests, and forces in Asia. The Asian Barometer Survey provides unique information on NPO participation and political activity in Japan, Hong Kong, Korea, Mongolia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Malaysia, which allows us to explore the roles of nonprofits in Asia (Dore & Jackson, Reference Dore and Jackson2019). Furthermore, given that those nonprofits operated in different political regimes, we also further test how the political regimes moderate the effects of the relationship between nonprofit participation and political participation. This study is significant as it provides an empirical model to test if nonprofit participation is positively correlated with political participation and how the diversity of the NPO channels (measured by the presence of different types of NPOs) also has different effects on political participation when controlling individual characteristics, location, and time fixed effects.

Literature Review

The classical literature, Democracy in America (Tocqueville, Reference De Tocqueville1969), shows that nonprofit activities are "schools of citizenship," in which identities and preferences are expressed through the organization of the activities that a nonprofit represents (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000). As Clemens (Reference Clemens, Powell and Steinberg2006) reviewed, in this stream of literature, nonprofits are known for generating capacities for collective actions (Hall, Reference Hall1992), a vehicle for the mobilization of disadvantages (Clemens, Reference Clemens1997), or the expression of diverse interests and preferences (Walzer, Reference Walzer1983). Based on those arguments, nonprofits and associations are fundamental to democracy as they are the vehicle for cultivating collective action, democratic values, and skills (Clemens, Reference Clemens, Powell and Steinberg2006).

Nevertheless, nonprofits have played an essential role during political transitions by participating in governmental reforms and responding to joint problems during the spread of democratization. NPOs provide engagement opportunities for people to participate in movements and resolve joint problems. However, after waves of democratic transitions in Asian countries, nonprofits have played significant roles in service provisions, yet the roles in advocacy have declined, which might hinder the development of democracy (Kongkirati, Reference Kongkirati2016; Thompson, Reference Thompson2021). For instance, recent studies show that nonprofits in authoritarian states supported and founded by a particular political party or regime might reduce political or democratic activities, such as advocacy (Ganesan, Reference Ganesan2017; Shin & Lee, Reference Shin and Lee2017). Thompson (Reference Thompson2021) also finds a decline in advocacy activities and avoidance of criticizing the government in the Philippines and Thailand. The roles of civil society in the development of democratization might be more complex than understood before from western literature.

Furthermore, in recent years, there has been a significant increase in organized activities and growth in the nonprofit sector of Asian countries due to economic growth (Anheier & Salamon, Reference Anheier and Salamon2006). Meanwhile, while Asia's economic growth will dramatically reduce global inequality, the problem of inequality within each country will rise, especially in the developing countries in Asia (Milanovic, Reference Milanovic2016). Therefore, a new appreciation of nonprofits' role as a vehicle to reduce inequality through public service provisions (Anheier & Salamon, Reference Anheier and Salamon2006).

Despite the significant contributions of nonprofits in Asia to economic stability, mobilization, and political transition, scholarly efforts to advance comparative research on Asian nonprofit research have lagged. Previous international comparative studies on civil society, such as the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project and CIVICUS Civil Society Index Project, cover nearly 40 countries, but only a few Asian countries (Japan, India, and Thailand) were included (Salamon & Anheier, Reference Salamon and Anheier1998; Salamon et al., Reference Salamon, Sokolowski and List1999). A more recent international comparative study on nonprofits by Salamon et al. (Reference Salamon, Haddock, Sokolowski, Butcher and Einolf2017) also called for more understanding of Asian countries. As a result, there is a need for a theoretical framework and robust data to compare and understand the patterns of nonprofit sectors in Asian countries.

Determinate of Political Participation

Political participation refers to voluntary activities, such as resolving public issues, voting, petitioning, protesting, or communicating with various political actors, which the public undertakes to address public issues or influence public policy (Uhlaner, Reference Uhlaner2015). Tocqueville argues that political participation can be cultivated by the secondary institutions of individuals' life as the school of democracy.

Brady et al. (Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995) argue that the way to understand political participation is to understand why people do not participate in politics. They further argue that people do not take part in politics because they do not have the necessary resources (such as time, money, and civic skills), psychological engagement (such as interest, trust, and a sense of making no difference through politics), or access (networks, social capital, membership, or channeled for mobilization, etc. Therefore, Brady et al. (Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995) have further developed a resource model of political participation. In particular, they show that participation in church and volunteering works that enhance civic skills predicts individual political participation in the U.S.

NPO Participation and Democracy Development

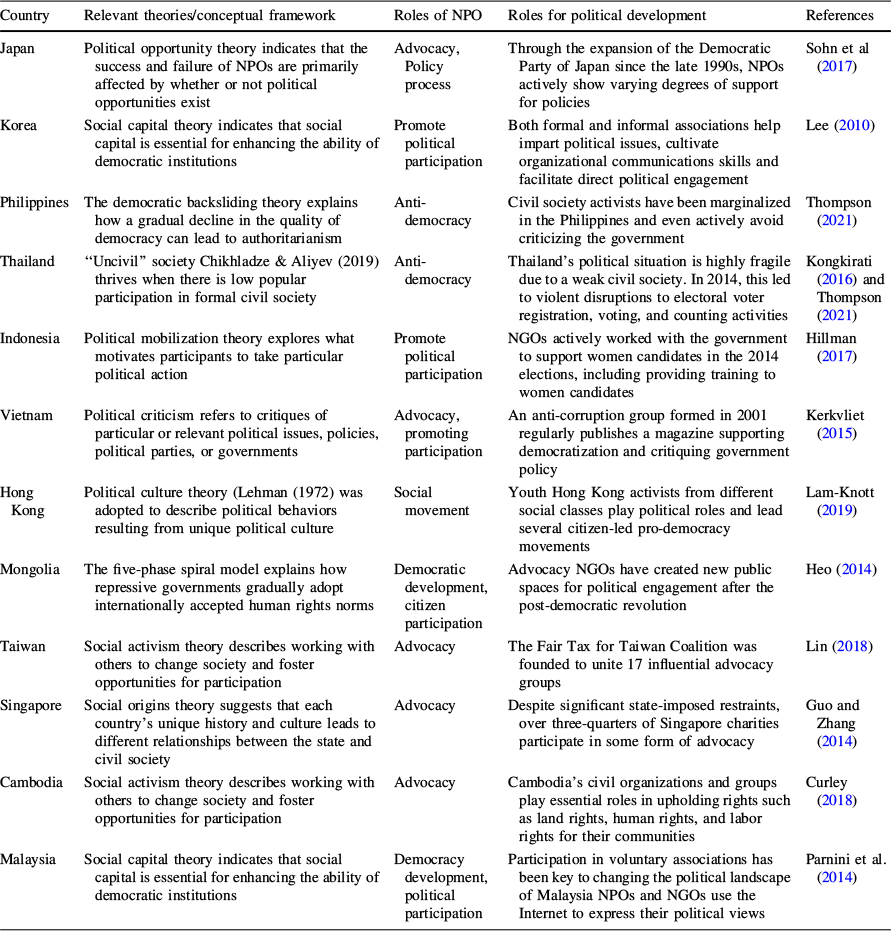

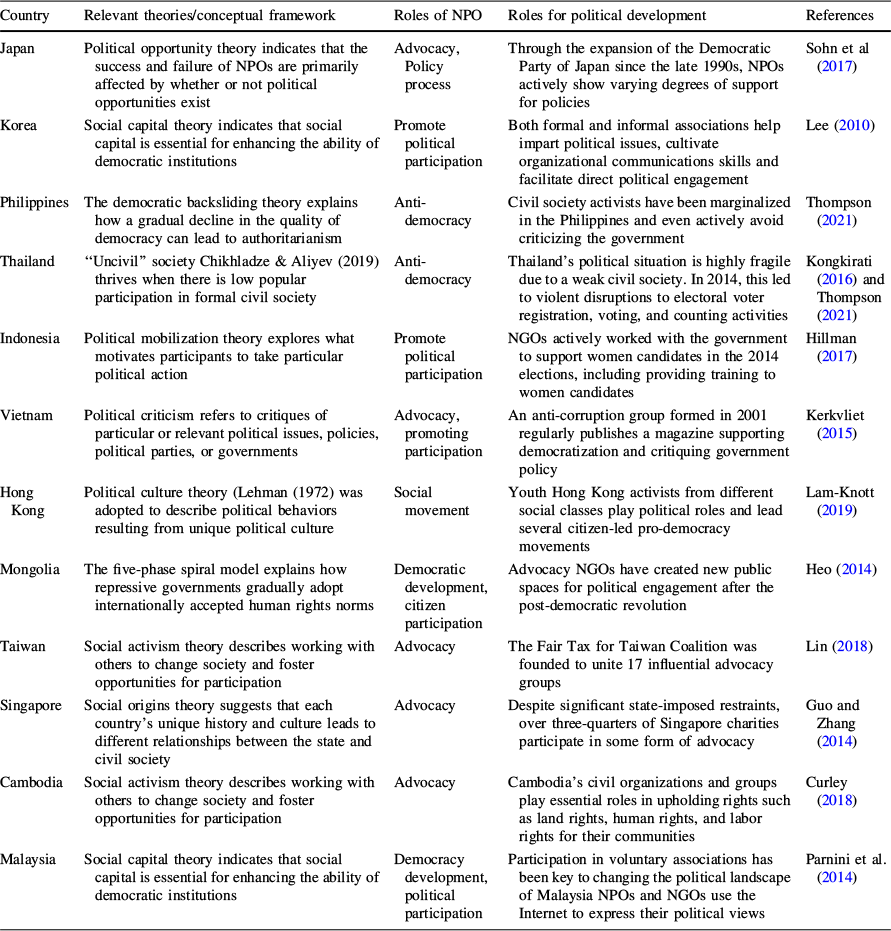

Nonprofit participation, generally speaking, refers to a form of giving or volunteering activities by the public (Jones, Reference Jones2006). This study focuses on the later activities of nonprofit participation. Specifically, volunteering involves activities organized by various entities, such as churches, civic and political organizations, or community associations (Liu & Nah, Reference Liu and Nah2022). The recent studies on Asian nonprofits have shed light on NPO participation and its roles in political participation that either leads to or hinder democratic development. We summarize related studies on Asian nonprofits (non-governmental organizations, associations, community-based organization, or civil society) regarding the theories adopted, the roles of nonprofits documented, and their relationship to political participation in Appendix 1.Footnote 2 The preliminary review shows the policy process (Kerkvliet, Reference Kerkvliet2015; Sohn et al., Reference Sohn, Jeong and Kim2017), public engagement (Heo, Reference Heo2014), social capital theory (Lee, Reference Lee2010; Parnini et al., Reference Parnini, Othman and Saifude2014; Terbish & Rawsthorne, Reference Terbish and Rawsthorne2020), social networks (Suebvises, Reference Suebvises2018), and advocacy (Hillman, Reference Hillman2017; Kalicki, Reference Kalicki2019; Lin, Reference Lin2018; Wahn, Reference Wahn2015) have been documented to explain the relationship between the development of democracy and NPO participation in Asia. For instance, Hillman (Reference Hillman2017) shows that a number of international and domestic civil society organizations in Indonesia effectively increased women's legislative representation in parliament by engaging women candidates in campaigning, communications, leadership, public speaking, and confidence-building activities. Additionally, Lee (Reference Lee2010) shows that individuals who are members of political associations have higher rates of democratic participation in South Korea than nonmembers. These studies indicate that NPOs provide channels through which citizens can participate in various social issues or political activities.

However, other studies show that NPOs potentially reduce political or democratic activities, such as voting or advocacy (Ganesan, Reference Ganesan2017; Kongkirati, Reference Kongkirati2016; Shin & Lee, Reference Shin and Lee2017; Thompson, Reference Thompson2021). For instance, Shin and Lee (Reference Shin and Lee2017) show that people's political advocacy activities are reduced through participatory governance in South Korea due to adoptive preferences. Others show that civil society organizations may inhibit democratic progress due to conflicts like those in Myanmar (Ganesan, Reference Ganesan2017). Given that most NPO research is reported through case studies, empirically examining the relationship between NPO participation and democratic development is necessary. Given the variation in democratic development across Asian countries, this region provides a unique opportunity for understanding such variation. Here, we will discuss how NPO participation affects democratic development in terms of political contact and political participation.

Effects of NPO Participation on Political Contact

One of the major functions of NPOs in Asia is advocacy, especially during democratic transitions (e.g.Allison & Taylor, Reference Allison and Taylor2017; Antlöv et al., Reference Antlöv, Brinkerhoff and Rapp2010; Hefner, Reference Hefner2019). According to government failure theory, NPOs often fill in the gaps in public services provision and provide what has not been provided by the government or market. In this process, NPOs alter the direction of public policies and express the people's preferences (Bryce, Reference Bryce2012). According to social network theory, NPOs serve as hubs and provide opportunities for NPO participants to build relationships with governments, communities, and policy stakeholders. For instance, certain NPOs, such as those related to agriculture, culture, and art, as well as unions and business associations, enable their members to express their needs to officials or influential leaders.

In the Asian context, NPOs attempt to influence government and policy decisions through direct and indirect methods, including contact with governments and mobilization. For instance, all NPOs in Singapore participate in advocacy activities, a higher number than the 67% of charities in the U.S. In particular, Guo and Zhang (Reference Guo and Zhang2014) show that NPOs in Singapore serve as hubs for their members to contact the government or participate in governmental committees involved in the policy-making process. In Indonesia, non-governmental organizations build social networks to pursue their agenda and develop their capacity to serve as a bridge for communication between the government and citizens (Antlöv et al., Reference Antlöv, Brinkerhoff and Rapp2010). Given these prior studies, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1

Across countries, those with NPO participation are more likely to have direct means of communication with the governments and public stakeholders.

Effects of NPO Participation on Political Participation

Political participation could be measured by participation in voting, signing a petition, joining a boycott, or joining in peaceful demonstrations/strikes (Jeong, Reference Jeong2013; Lee, Reference Lee2020). In South Korea, empirical studies show that participation in nonprofit and association are mostly positively related to political participation (Jeong, Reference Jeong2013; Lee, Reference Lee2020). For instance, Lee (Reference Lee2020) shows that people affiliated with humanitarian or charitable organizations are more likely to participate in boycotts or sign petitions, while affiliations with labor unions correlate with strikes. These empirical studies provide evidence that different types of organizations provide different types of channels for political participation.

Furthermore, Putnam (Reference Putnam1993) finds that a vibrant civil society is closely related to democratic development and government performance. Three critical theories explain the relationship between NPO participation and political participation. First, according to social capital theory, active participation in NPOs provides opportunities for citizens to deliberate on public affairs and participate in activities related to public issues (Suebvises, Reference Suebvises2018). NPO participation provides social capital, enabling citizens to take collective action regarding issues that affect their daily lives. Such participation cultivates the opportunities, knowledge, and skills needed to help resolve public issues, sign petitions, participate in protests, and vote (Putnam, Reference Putnam1993). Second, social network theory, a related concept, suggests that NPO participation also enables collective action by increasing social interactions among different stakeholders (Putnam & Goss, Reference Putnam, Goss and Putnam2002). NPO participation enriches citizens' interactions with the community and governmental actors and thus provides the opportunities and information necessary for citizens to participate in the policy-making process (Bryce, Reference Bryce2012). Third, in the public engagement literature, Boris and Mosher-Williams (Reference Boris and Mosher-Williams1998) show that advocacy nonprofits are an essential platform for citizens to participate in political activities. Furthermore, Child and Grønbjerg (Reference Child and Grønbjerg2007) show that environment-, animal-, and health-related as well as mutual benefit nonprofits are more likely than other types of nonprofits to participate in political advocacy activities.

In the Asian context, NPO participation is essential for political participation and activities (e.g., Jeong & Kearns, Reference Jeong and Kearns2015). In particular, nonprofits serve as civic leaders, facilitating political activism across society, as seen in South Korea (Jeong & Kearns, Reference Jeong and Kearns2015), Hong Kong (Lam-Knott, Reference Lam-Knott2019), and Indonesia (Hefner, Reference Hefner2019). For instance, Kim and Choi (Reference Kim and Choi2020) show that Asia–Pacific countries with better labor rights protection have more active NPO participation in the policy-making process. Additionally, Yeh and Cheng (Reference Yeh and Cheng2020) show that the Taiwan Pharmacist Association, a volunteer-based membership organization, played a vital role in negotiating with the government to work together for the public good, such as stabilizing facial mask supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on those prior studies, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2

Across countries, those with NPO participation are more likely to engage in political activities.

Moderating Effects by Political Systems

Previous studies show that political regime type affects the environment in which a nonprofit organization operates in Asia (Curley, Reference Curley2018; Kim & Choi, Reference Kim and Choi2020; Sidel, Reference Sidel2008, Reference Sidel2010). For instance, Kim and Choi (Reference Kim and Choi2020) show that countries where civil society organizations actively participate in the government's policy-making processes demonstrate better labor rights. They argue that those regime types play a critical role in shaping the relationship between civil society organizations and participation in policy-making. However, studies have also shown that government regulation and governance tighten the control over nonprofits affecting the types of nonprofits participating in the policy-making process in authoritarian or hybrid systems (e.g., Curley, Reference Curley2018; Curley et al., Reference Curley, Dressel and McCarthy2018). Thus, nonprofit participation in public policy-making varies across Asia, depending on the political systems. Based on those prior studies, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.1

The political regime (i.e., authoritarian or hybrid) weakens the positive effect of the likelihood of those with NPO participation engaging in political contact activities.

H3.2

The political regime (i.e., authoritarian or hybrid) weakens the positive effect of the likelihood of those with NPO participation engaging in political participation activities.

Method and Data

Data

To test our hypotheses, we adopted the Asia Barometer Survey (ABS) conducted in two waves, 2010 and 2015. The ABS provides comparable individual-level data on public opinion on social, economic, and political issues, as well as the background characteristics of the respondents. ABS is administrated by the Hu Fu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies at the National Taiwan University and adopted and modified from the Eurobarometer, established in 1970. A network of research teams administrated the survey, which adopted consistent data collection methodology and sampling techniques for cross-country comparisons (Lee, Reference Lee2017). The research teams conducted face-to-face or phone interviews with nationally representative samples of the voting population (ranging from 17 to 19 years old and above). For each country, a standard sample size of 1000 to 1600 respondents was selected, with a 24–90% response rate (Lee, Reference Lee2010). Studies adopted this dataset for understanding political perceptions (Welsh & Huang, Reference Welsh and Huang2016), social capital and participation (Lee, Reference Lee2010), and social capital (Kim, Reference Kim2013), as well as internet and political participation (Lee, Reference Lee2017).

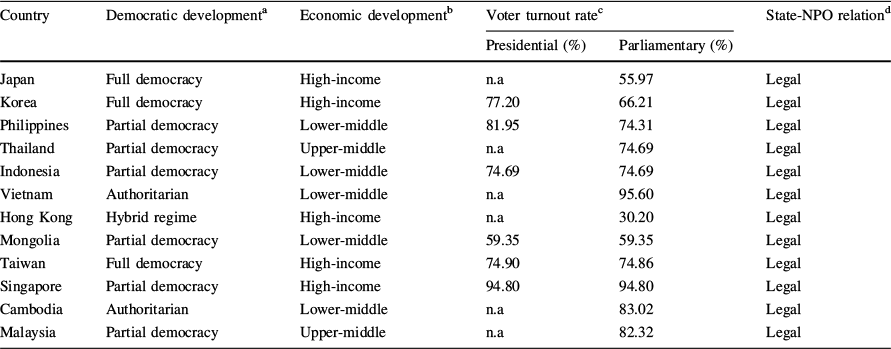

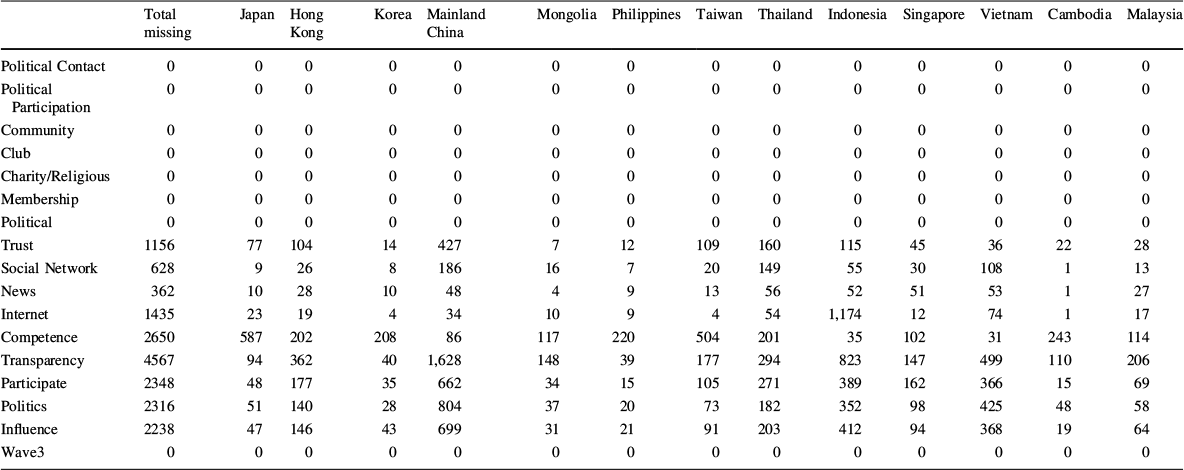

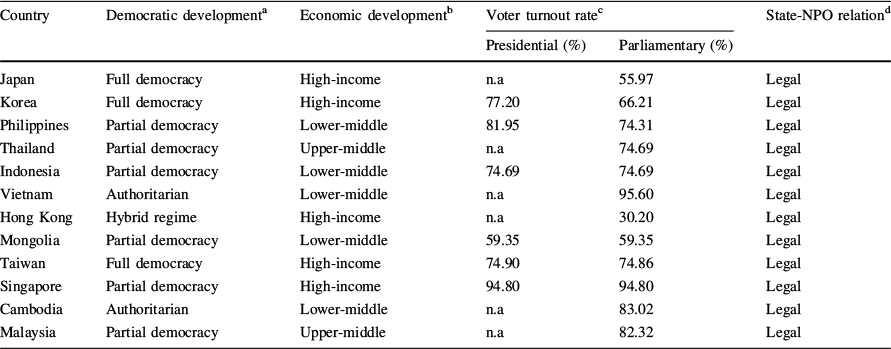

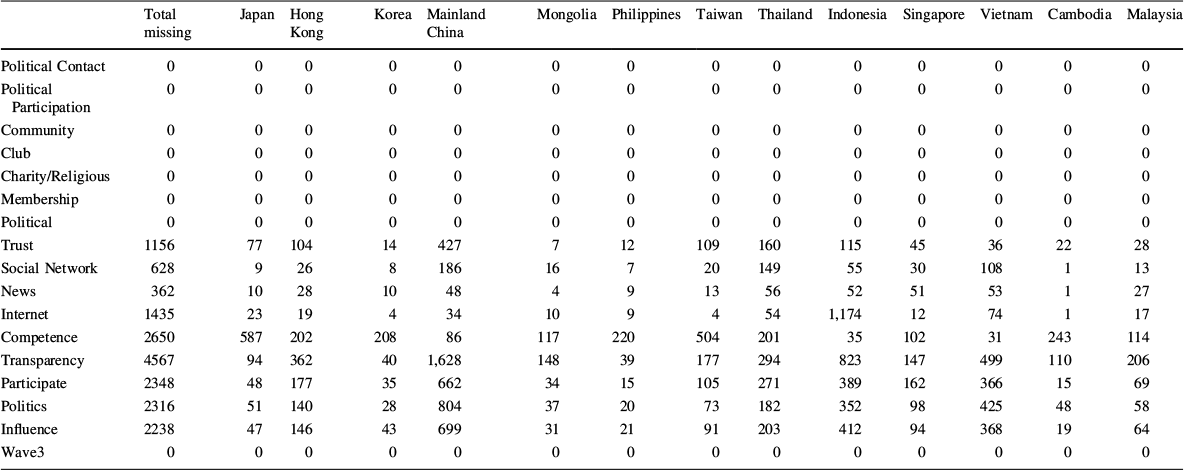

This data set contains sufficient information to investigate how NPO participation is associated with involvement in political activities across different Asian countries. In particular, the data set contains information on two types of political activities (political contact and participation), types of NPO participation, political attitudes, trust in institutions, and social capital. To contend with the missing data, we adopt the listwise deletion method. After removing the missing values, the total sample size was 25,348 responses in 12 countries and regions (See Appendix 4 for the tabulation of the missing values in the original dataset by countries). The 12 countries and regionsFootnote 3 included Japan, Hong Kong, Korea (South), Mongolia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Malaysia. Furthermore, we show the summaries of the studied samples' democratic development, economic development, and voter turnout rate, as well as the state and nonprofit relationship, measured by the legal status of nonprofits in Appendix 2.

Additionally, for testing the moderating effects of political systems, we adopted the Economist intelligence unit's index of democracy dataset in 2015 that provides assessments of the democratic states of the studied countries. In particular, the Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index (2008) contains assessments of 165 independent states and regions' states of democracy. The Index includes five categories: electoral process, government functioning, participation, political culture, and civil liberties. This dataset is also used for assessing democratic states in different fields (e.g., Elff & Ziaja, Reference Elff and Ziaja2018; Wigley et al., Reference Wigley, Dieleman, Templin, Kiernan and Bollyky2020).

Empirical Model

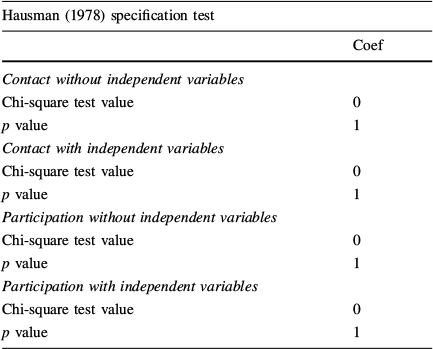

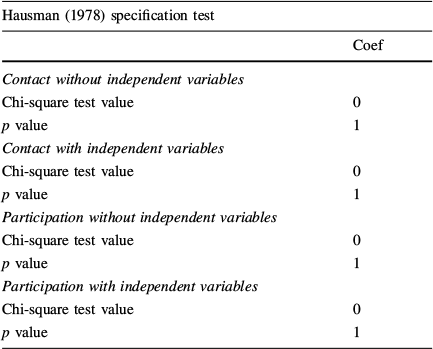

This study adopted ordered logistic regression models to test political activities and NPO participation hypotheses while controlling for other important individual characteristics. An ordered logistic regression model is used because the political activities are accounted for using a set of categorical variables, measuring the number of political activities from 0 to 5. Applying an ordinary least squares (OLS) model in this setting would lead to heteroscedastic disturbance (Greene, Reference Greene2003). Additionally, the Hausman test examines the country's fixed and random effects in each model for each dependent variable (Greene, Reference Greene2003). We examine each model by assuming that the country effect is random or fixed, while the null hypothesis is that the random effect is preferred. The Hausman results show that the p value is very small (all equal to 0), and thus the null hypothesis can be rejected (see Appendix 9). Hence, we can conclude that fixed effects are more appropriate than random effects for interpreting country effects in all models. Furthermore, we split the samples by political systems to account for any moderating effects.

Measurement of Variables

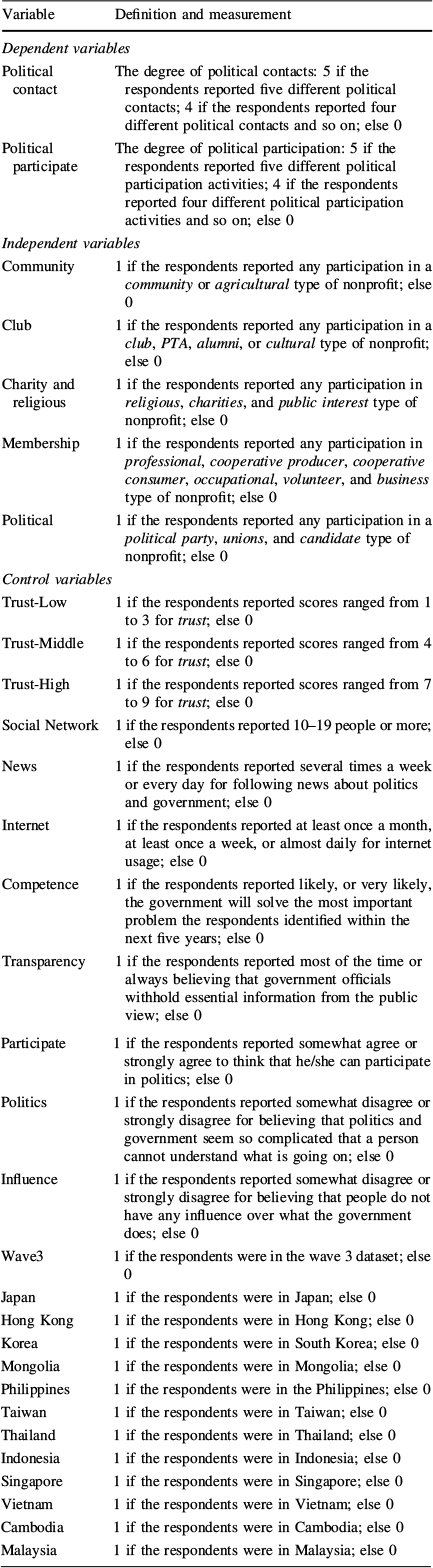

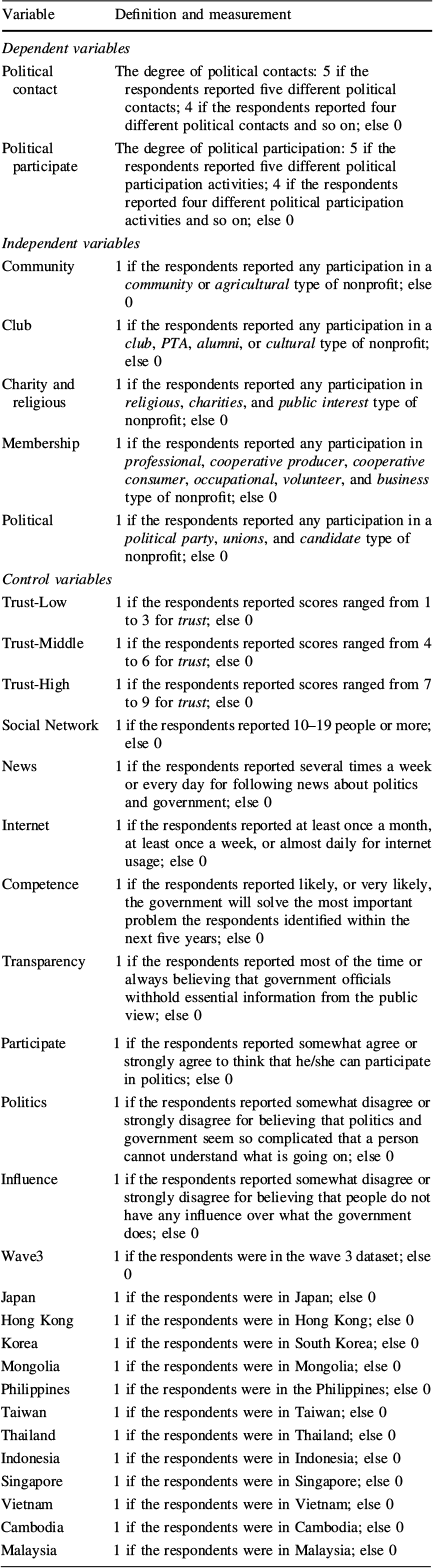

Appendix 3 shows the properties of the studied variables, including two independent variables, five types of NPO participation as the independent variables, and 24 control variables. Detailed descriptions of these variables are below.

Dependent Variables: Political Activities

Ten survey items were used to create two dependent variables: political contact and political participation, to understand the association between NPO participation and political engagement. Previous studies have combined the dependent variables and composited a new dependent variable (e.g., Kim, Reference Kim2014). This approach is also appropriate for this study. Therefore, all dependent variables are coded into categorical variables. We included five variables in the political contact category: contact with elected officials, higher-level officers, community leaders, influential leaders, and media. We included five variables in the political participation category, including problem resolution, voting, petitions, protests, and force. In particular, in the political contact variable, one if the respondent reported one type of political contact activities, two if the respondent reported two types of political contact activities, three if the respondent reported three types of political contact activities, four if the respondent reported four types of political contact activities, five if the respondent reported five types of political contact activities, 0 otherwise. Also, in the political participation variable, one if the respondent reported one type of political participation activities, two if the respondent reported two types of political contact activities, and so on, 0 otherwise.

Independent Variables: Nonprofit Participation

Based on the theories discussed above, survey questions on NPO participation were incorporated to measure the types of NPO participation among individuals in different countries. Additionally, because previous empirical studies show that different types of organizations facilitate different types of participation in political activities (Jeong, Reference Jeong2013; Lee, Reference Lee2020), we grouped those eighteen types of nonprofits into five major groups in order to show the diversity of nonprofit participation: community (including community and agricultural), club (including club, PTA, Alumni, and Culture), charity and religious (including charities, public interest, and religious), membership (including professional, cooperative for producer, cooperative for consumer, occupational, volunteer, and business), and political (including political party, unions, and candidate).

Control Variables

While this study aims to understand associations between NPO participation and political activities, participation in political activity is a function of other factors, including trust (Kim, Reference Kim2014), social networks, news consumption, internet usage, perception of the government, and perception of one's self-competence in political participation. We also incorporated news consumption and internet usage to capture individuals' connection to the outside world. Also, the study includes the perception of the government's ability to resolve issues to measure the perception of government competence and transparency. It was also essential to consider respondents' confidence in participating in political activities. In addition to instituting individual-level control, we also control for a time, wave 3, and country dummies to reduce endogeneity due to any country variance.

Findings

Description of Political Activities

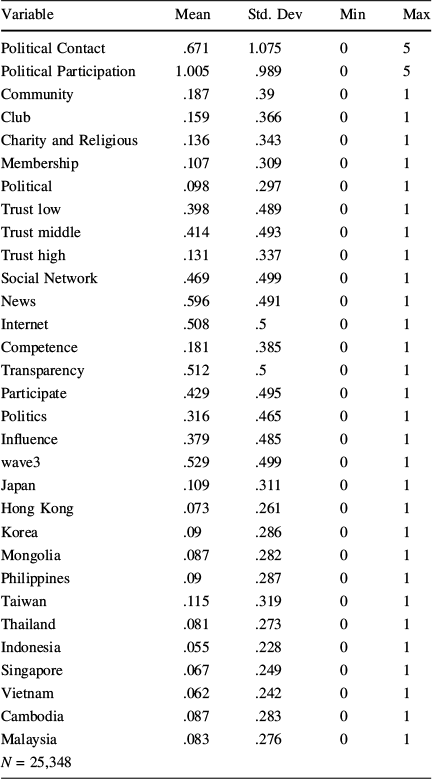

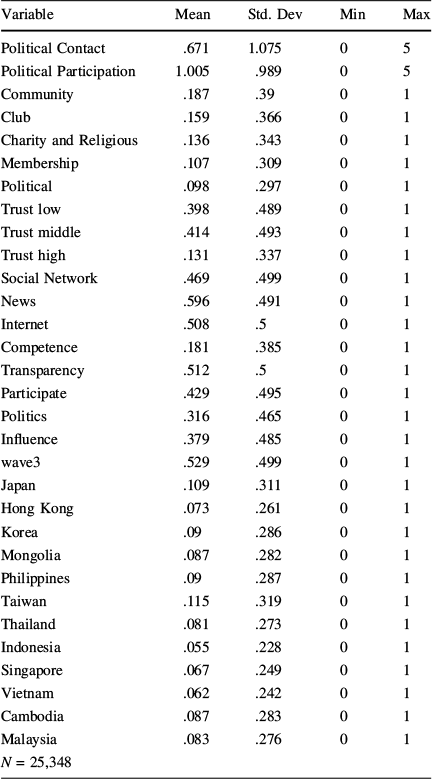

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the studied variables. In the dependent variable category, the average score for political contact is 0.671, while the one for political contact is 1.005.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics

Variable |

Mean |

Std. Dev |

Min |

Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Political Contact |

.671 |

1.075 |

0 |

5 |

Political Participation |

1.005 |

.989 |

0 |

5 |

Community |

.187 |

.39 |

0 |

1 |

Club |

.159 |

.366 |

0 |

1 |

Charity and Religious |

.136 |

.343 |

0 |

1 |

Membership |

.107 |

.309 |

0 |

1 |

Political |

.098 |

.297 |

0 |

1 |

Trust low |

.398 |

.489 |

0 |

1 |

Trust middle |

.414 |

.493 |

0 |

1 |

Trust high |

.131 |

.337 |

0 |

1 |

Social Network |

.469 |

.499 |

0 |

1 |

News |

.596 |

.491 |

0 |

1 |

Internet |

.508 |

.5 |

0 |

1 |

Competence |

.181 |

.385 |

0 |

1 |

Transparency |

.512 |

.5 |

0 |

1 |

Participate |

.429 |

.495 |

0 |

1 |

Politics |

.316 |

.465 |

0 |

1 |

Influence |

.379 |

.485 |

0 |

1 |

wave3 |

.529 |

.499 |

0 |

1 |

Japan |

.109 |

.311 |

0 |

1 |

Hong Kong |

.073 |

.261 |

0 |

1 |

Korea |

.09 |

.286 |

0 |

1 |

Mongolia |

.087 |

.282 |

0 |

1 |

Philippines |

.09 |

.287 |

0 |

1 |

Taiwan |

.115 |

.319 |

0 |

1 |

Thailand |

.081 |

.273 |

0 |

1 |

Indonesia |

.055 |

.228 |

0 |

1 |

Singapore |

.067 |

.249 |

0 |

1 |

Vietnam |

.062 |

.242 |

0 |

1 |

Cambodia |

.087 |

.283 |

0 |

1 |

Malaysia |

.083 |

.276 |

0 |

1 |

N = 25,348 |

Patterns of NPO Participation

Our data show diverse and dispersed participation for the independent variables that measure NPO participation in Appendix 5. The most common types of reported NPO participation are as follows: 18.7% participate in community associations; 15.9% participate in clubs; 13.6% participate in charity and religion; 10.7% participate in membership associations, and 9.8% participate in political-related associations.

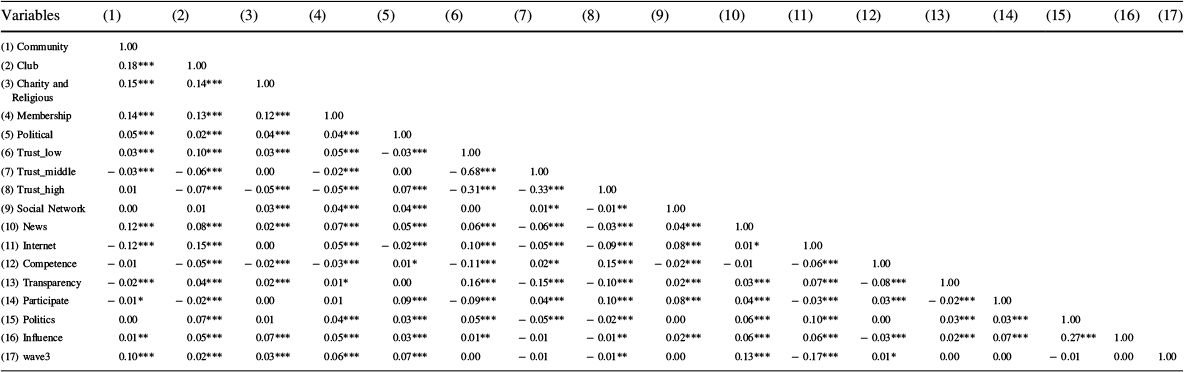

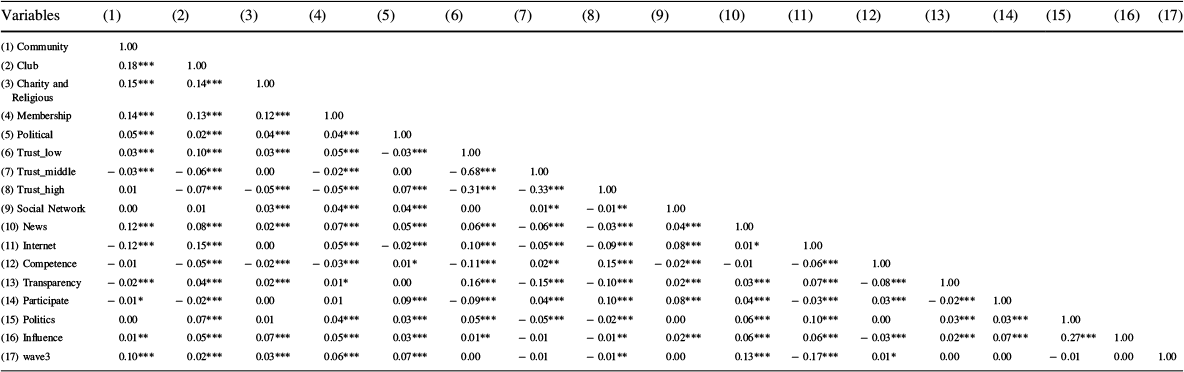

The correlations among the variables were examined and shown in Appendix 6. The correlation matrix examines the correlation between independent variables and control variables. Political party participation has a significant correlation with all the control variables. Additionally, NPO participation variables, including clubs, arts/cultural organizations, Charities, and public interest groups, statistically significantly correlated with most control variables. Given these correlations, we further employed the variance inflator factor (VIF) (Gómez et al., Reference Gómez, Pérez, Martín and García2016) to check for multicollinearity. Our results confirmed no multicollinearity problem in the modelsFootnote 4 (results upon request).

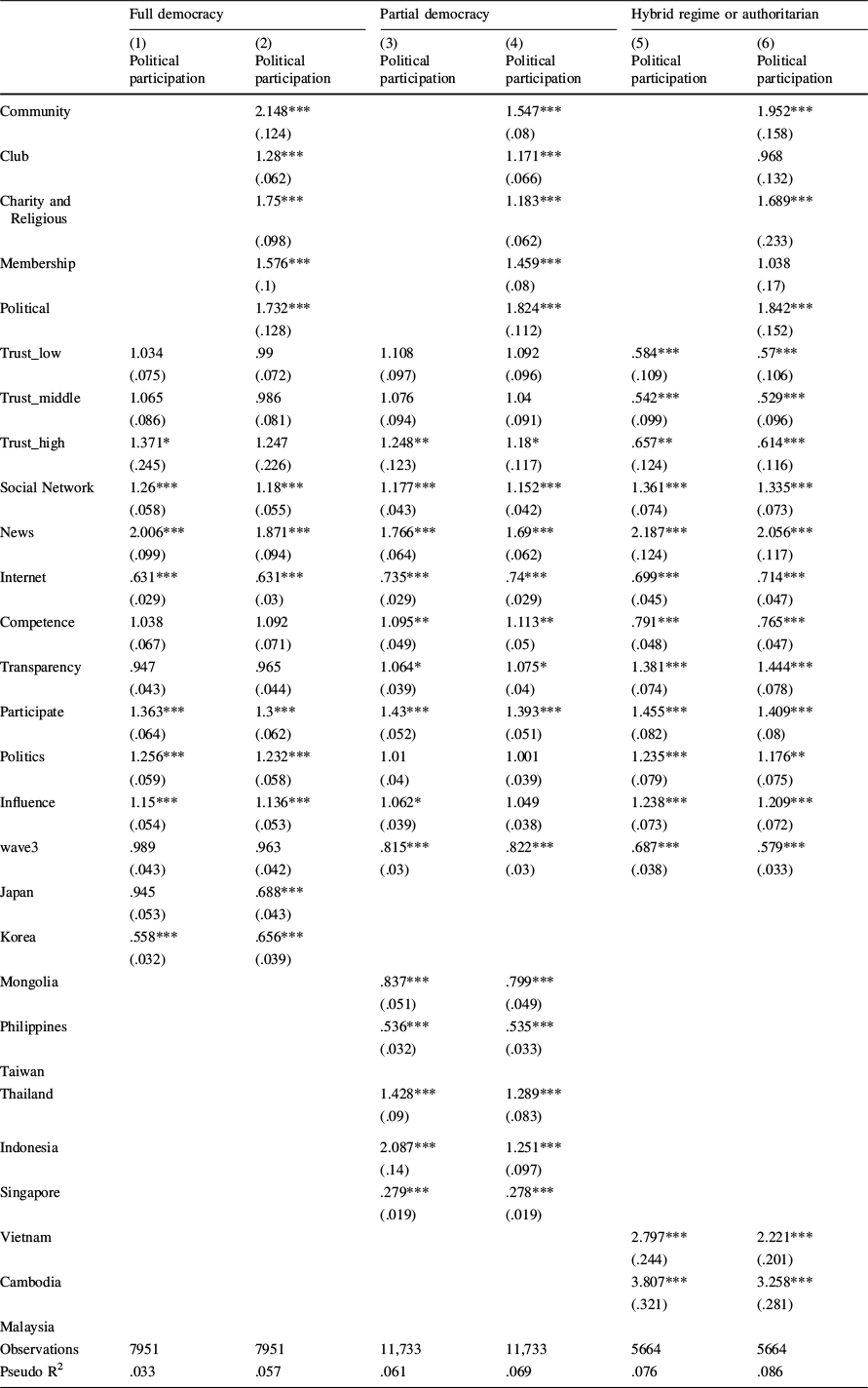

Table 2 Ordered logistic regression: political contacts and participations

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Political contact |

Political contact |

Political participation |

Political participation |

|

Community |

1.47*** |

1.793*** |

||

(.055) |

(.062) |

|||

Club |

1.17*** |

1.214*** |

||

(.046) |

(.043) |

|||

Charity/Religious |

1.374*** |

1.422*** |

||

(.055) |

(.052) |

|||

Membership |

1.537*** |

1.468*** |

||

(.067) |

(.059) |

|||

Political |

1.82*** |

1.72*** |

||

(.079) |

(.07) |

|||

Trust: low |

.986 |

.965 |

1.017 |

.991 |

(.06) |

(.059) |

(.054) |

(.053) |

|

Trust: middle |

1.04 |

.996 |

.993 |

.946 |

(.065) |

(.063) |

(.055) |

(.052) |

|

Trust: high |

1.216*** |

1.12 |

1.151** |

1.055 |

(.087) |

(.081) |

(.075) |

(.069) |

|

Social Network |

1.213*** |

1.178*** |

1.235*** |

1.198*** |

(.034) |

(.033) |

(.031) |

(.03) |

|

News |

1.694*** |

1.599*** |

1.913*** |

1.81*** |

(.049) |

(.047) |

(.049) |

(.047) |

|

Internet |

1.039 |

1.04 |

.697*** |

.701*** |

(.032) |

(.032) |

(.019) |

(.019) |

|

Competence |

1.058 |

1.065* |

.987 |

.996 |

(.037) |

(.037) |

(.031) |

(.031) |

|

Transparency |

1.068** |

1.079*** |

1.085*** |

1.104*** |

(.03) |

(.03) |

(.027) |

(.028) |

|

Participate |

1.571*** |

1.523*** |

1.417*** |

1.374*** |

(.044) |

(.043) |

(.036) |

(.035) |

|

Politics |

1.127*** |

1.101*** |

1.142*** |

1.121*** |

(.034) |

(.034) |

(.031) |

(.03) |

|

Influence |

1.119*** |

1.101*** |

1.127*** |

1.107*** |

(.032) |

(.031) |

(.029) |

(.029) |

|

wave3 |

1.061** |

1.018 |

.829*** |

.801*** |

(.029) |

(.028) |

(.02) |

(.02) |

|

Japan |

2.195*** |

yah |

3.623*** |

2.151*** |

(.195) |

(.129) |

(.231) |

(.145) |

|

Korea |

3.505*** |

3.116*** |

1.915*** |

1.673*** |

(.309) |

(.278) |

(.127) |

(.113) |

|

Mongolia |

2.505*** |

2.148*** |

4.916*** |

4.422*** |

(.227) |

(.196) |

(.324) |

(.294) |

|

Philippines |

5.628*** |

5.111*** |

3.2*** |

2.892*** |

(.49) |

(.446) |

(.209) |

(.19) |

|

Taiwan |

2.671*** |

2.003*** |

3.55*** |

2.698*** |

(.233) |

(.177) |

(.221) |

(.171) |

|

Thailand |

12.746*** |

10.577*** |

8.249*** |

6.544*** |

(1.099) |

(.922) |

(.554) |

(.447) |

|

Indonesia |

5.587*** |

2.853*** |

11.924*** |

5.623*** |

(.522) |

(.284) |

(.857) |

(.437) |

|

Singapore |

2.098*** |

1.907*** |

1.894*** |

1.737*** |

(.204) |

(.187) |

(.134) |

(.123) |

|

Vietnam |

17.455*** |

15.096*** |

3.023*** |

2.477*** |

(1.615) |

(1.402) |

(.225) |

(.186) |

|

Cambodia |

8.485*** |

7.442*** |

3.904*** |

3.465*** |

(.744) |

(.657) |

(.265) |

(.237) |

|

Malaysia |

6.244*** |

5.737*** |

6.147*** |

5.667*** |

(.543) |

(.5) |

(.406) |

(.375) |

|

Observations |

25,348 |

25,348 |

25,348 |

25,348 |

Pseudo R2 |

.078 |

.087 |

.065 |

.077 |

Standard errors are in parentheses

***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1

Effects of NPO Participation on Political Contact

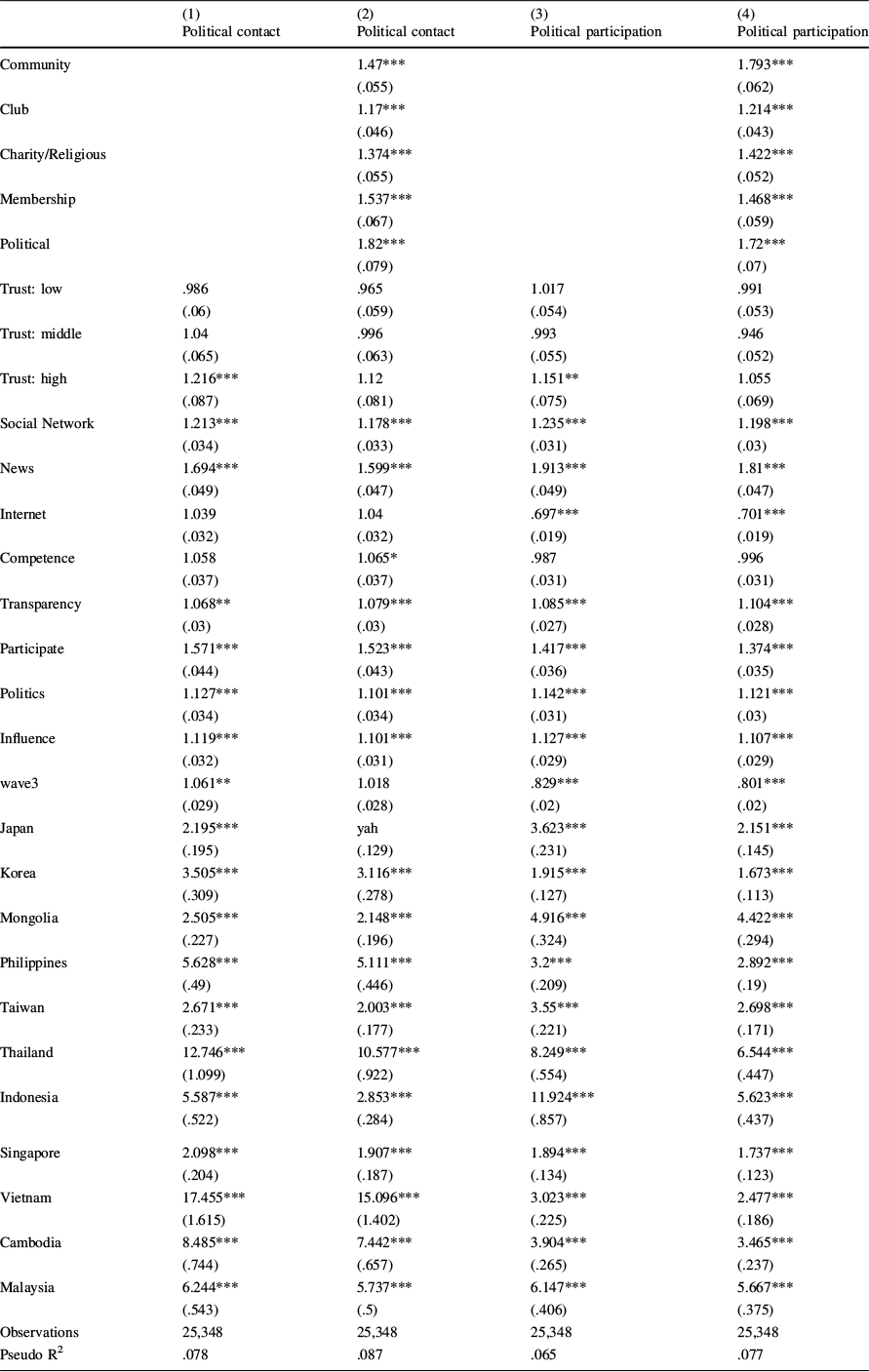

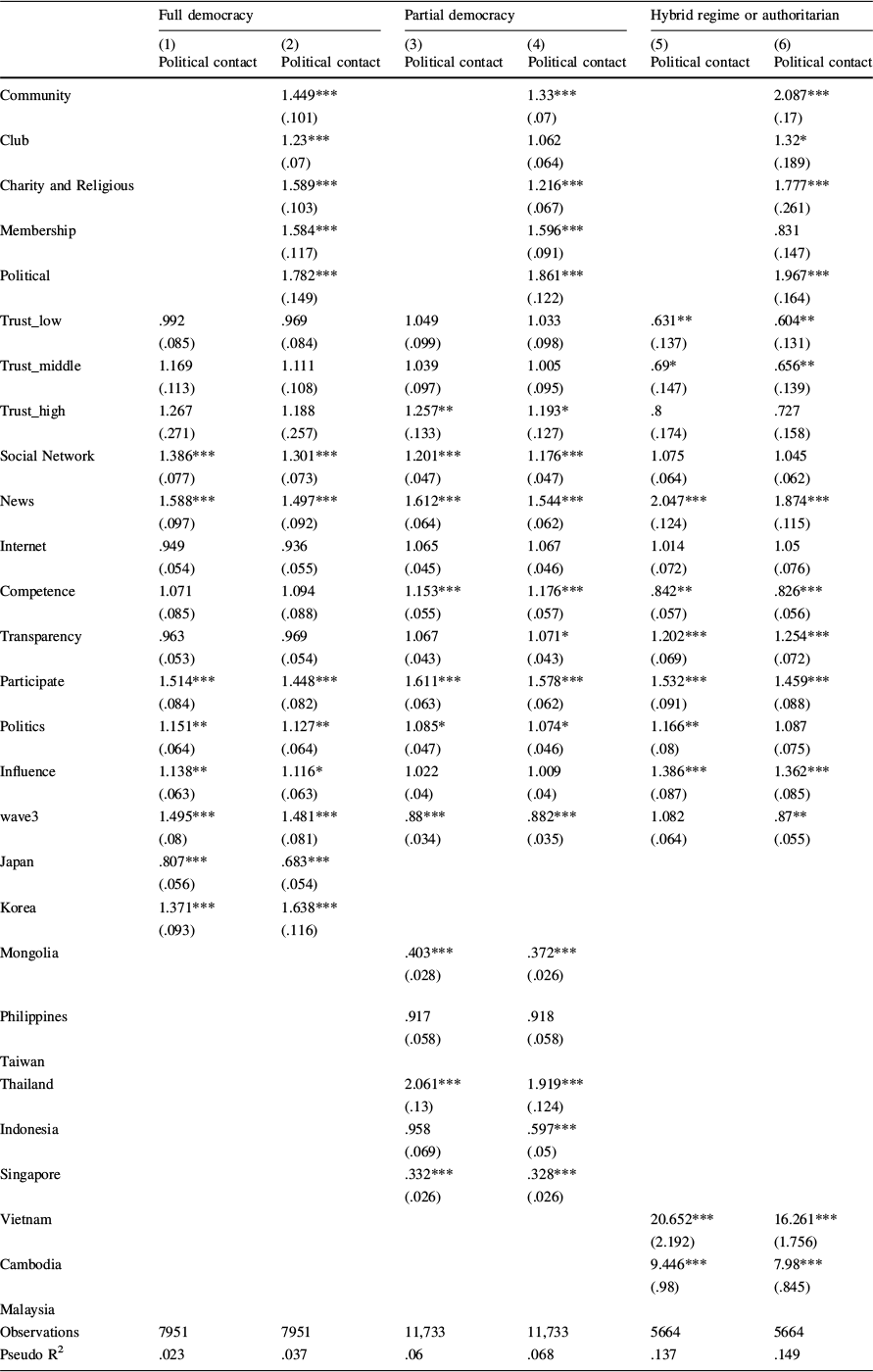

We hypothesized that NPO participation would be associated with political contact in Asia (Antlöv et al., Reference Antlöv, Brinkerhoff and Rapp2010; Guo & Zhang, Reference Guo and Zhang2014). Our results show that participating in NPOs is significantly positively associated with political contact activities (Table 2). More specifically, participating in the community, club, charity/religious, membership, or political type of NPOs is significantly positively associated with higher political contact. For instance, the odds of increasing political contact activities by a scale are 47.0% higher for the people participating in the community, 17.0% higher for the people participating in the club, 37.4% higher for the people participating the charity and religious organizations, 53.7% higher for the people participating the membership organizations, and 82.0% higher for the people participating the political organizations compared with those never contacted.

As for the findings of our control variables, the results are primarily in line with previous findings that social network size, level of news consumption, perception of government competence and transparency, knowledge of politics, and ability to affect change are significantly positively associated with political contact activities. Furthermore, for all the country dummies are significantly positively associated with political contact activities.

Effects of NPO Participation on Political Participation

We hypothesized that NPO participation would also be associated with the level of political participation in Asia (Jeong & Kearns, Reference Jeong and Kearns2015; Kim & Choi, Reference Kim and Choi2020; Lam-Knott, Reference Lam-Knott2019; Yeh & Cheng, Reference Yeh and Cheng2020). Our results show that participating in NPOs is significantly positively associated with political participation (Table 2). More specifically, participating in the community, club, charity/religious, membership, or political type of NPOs is significantly positively associated with higher political participation activities. For instance, the odds of increasing political participation activities by a scale are 79.3% higher for the people participating in the community, 21.4% higher for the people participating the club associations, 42.2% higher for the people participating the charity and religious organizations, 46.8% higher for the people participating in the membership organizations, and 72.0% higher for the people participating the political organizations compared with those never participated.

Most results are predicted based on literature when considering the control variables, including social networks, news consumption, perception of government transparency, and self-competence in political participation. Other control variables have only partial effects on political participation. Interestingly, internet usage and being in wave 3 (2015) are significantly negatively associated with political participation. When examining the results of country dummies, all the dummies are significantly positively associated with political participation activities.

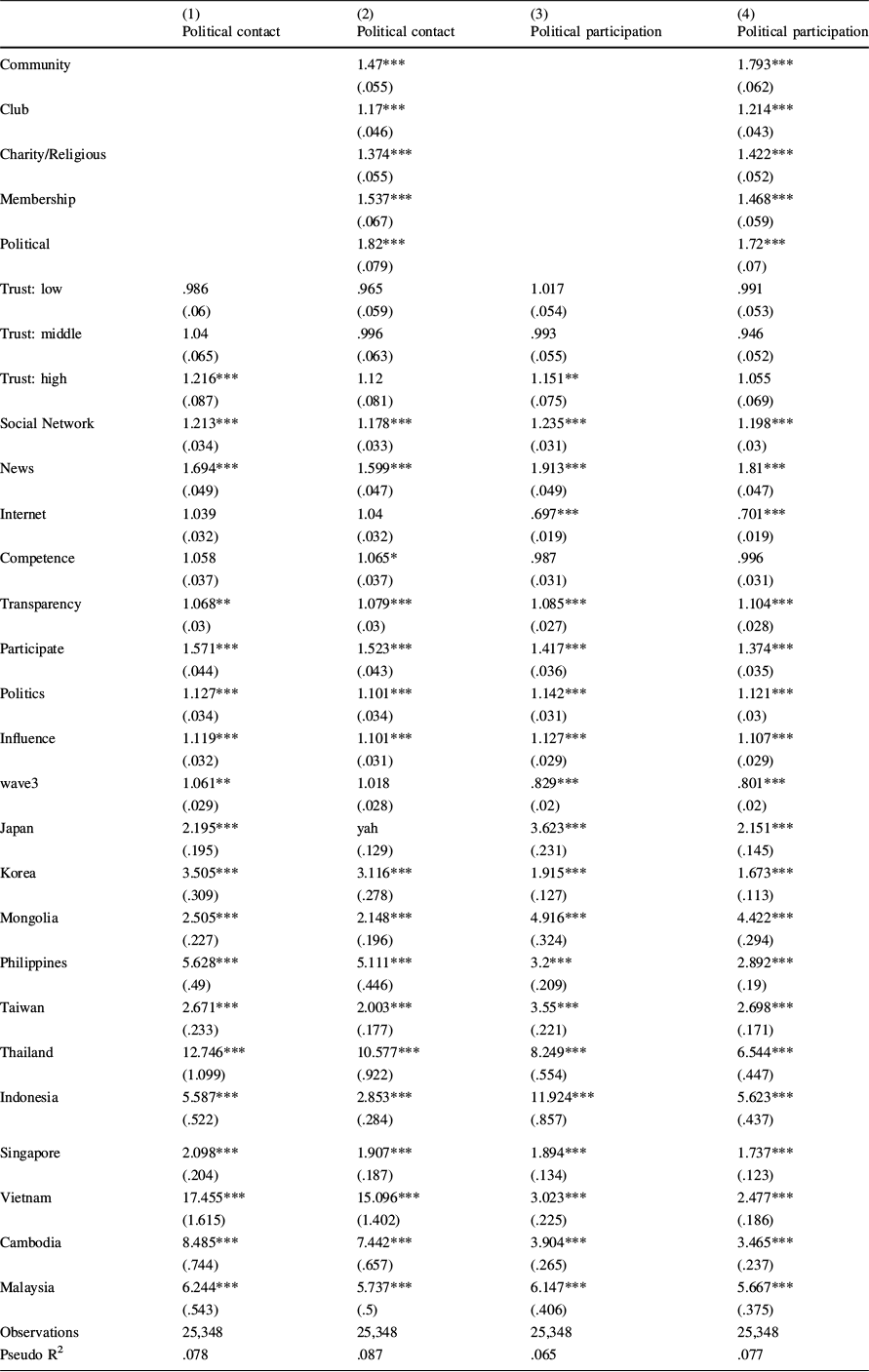

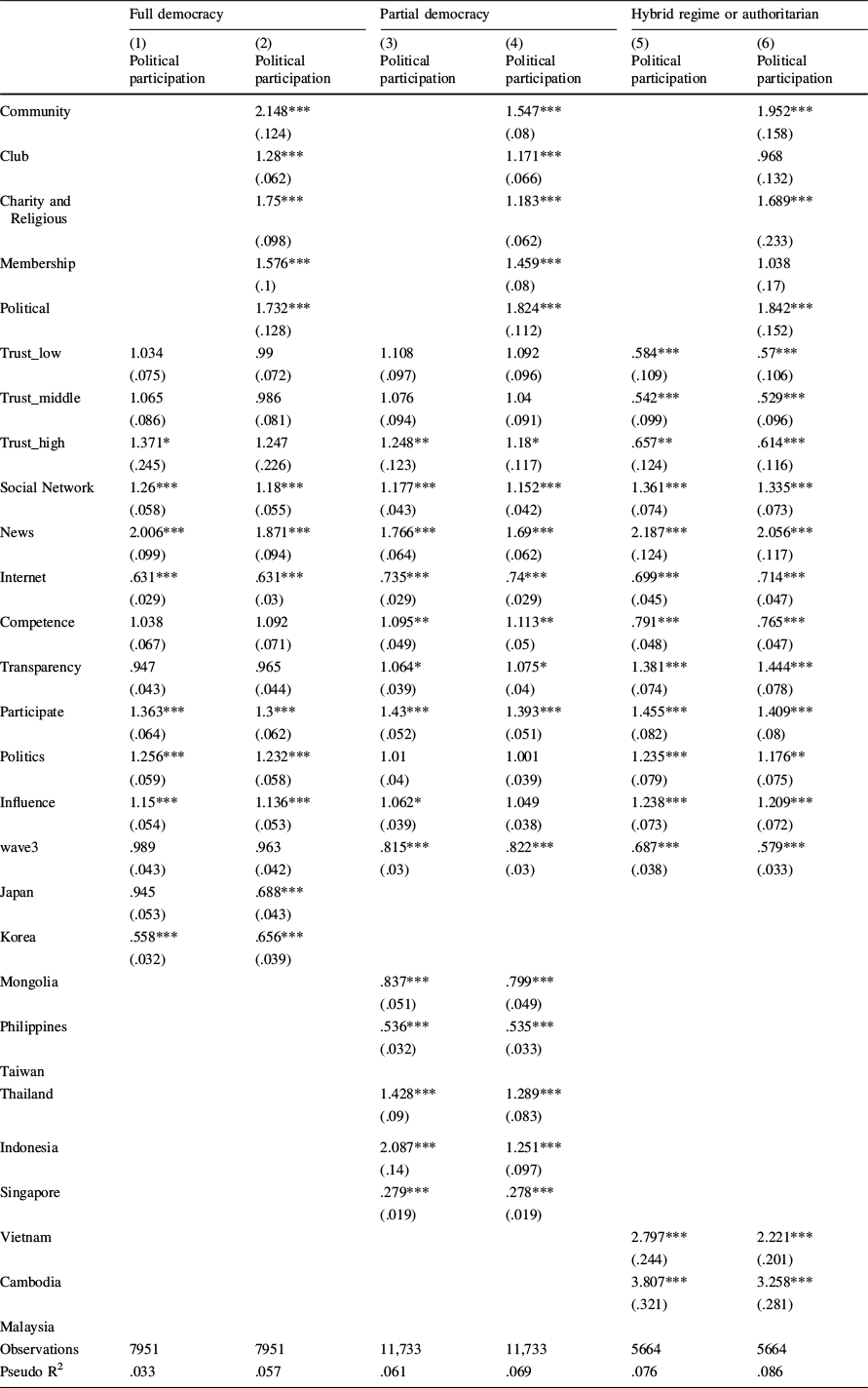

Moderating Effects of Political Systems

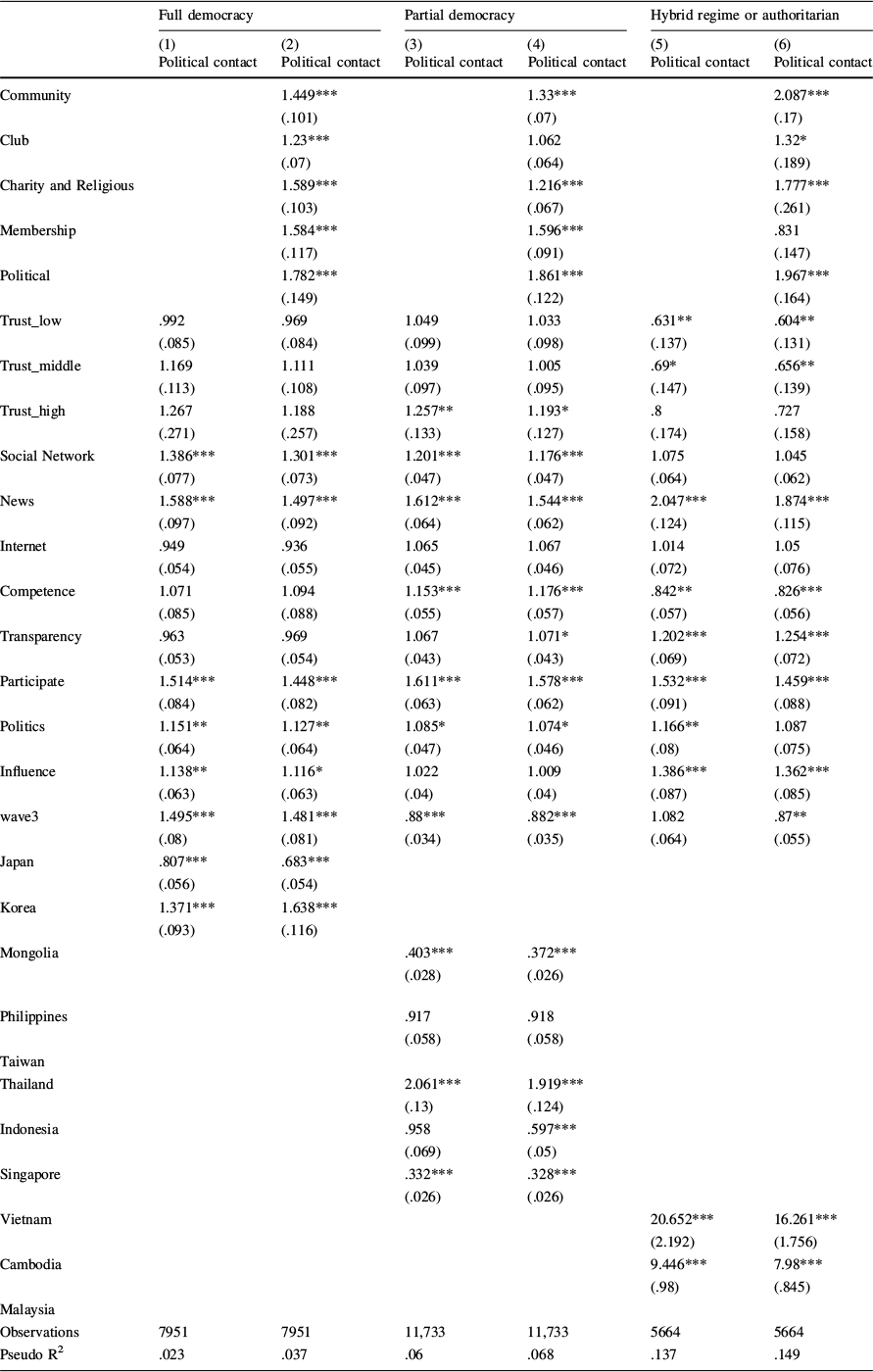

The ordered logistic regression with split samples helps us further specify the relationship between NPO participation and political contacts/participation moderating by democratic states, as argued by Kim and Choi (Reference Kim and Choi2020). First, the results in Appendix 7 confirm the variation of the relationships between NPO and political contacts among different political systems, according to the Chow test. For instance, in fully democratic states, participation in different types of NPOs is positively correlated with political contact activities. However, in the partial democracy and hybrid/authoritarian systems, only four types of NPO participation are positively correlated with political contact activities, except club participation. Similarly, for the hybrid/authoritarian systems, only four types of NPO participation are positively correlated with political contact activities, except membership participation. When examining control variables across different political systems, having lower trust and believing in governments’ competence are negatively associated with political contacts in the hybrid regime/authoritarian. The odds of being in Japan in the fully democratic system and Indonesia in the partial democratic system are also negatively associated with political contacts.

The results in Appendix 8 further confirm the variation of the relationships between NPO and political participation among different political systems, also confirmed by the Chow test. In the full and partial democratic states, participation in five different types of NPO remains positively correlated with political participation. However, for the hybrid and authoritarian systems, only the community, charity/religious, and political types of nonprofit participation positively correlate with political participation. When examining control variables, being in Japan, and South Korea in the fully democratic system and being in Mongolia, the Philippines, and Singapore in the partial democratic system is negatively associated with political participation. Also, respondents reported in wave 3, 2015 are negatively associated with political participation in the partial democratic and the hybrid and authoritarian systems, suggesting a possible decline in democratic participation due to increased government controls and regulations.

Discussions

Who Participate?

Based on the relevant literature, we hypothesized first that those with nonprofit participation are more likely to engage in political contacts. Results from the ordered logistic regression models substantiated this. These findings confirm the previous studies that NPOs are essential for democratic transitions, as they foster political engagement and participation (Collins, Reference Collins2014; Das, Reference Das2018; Wahn, Reference Wahn2015) and further expand the support to the Asian context, as argued by Guo and Zhang (Reference Guo and Zhang2014) and Antlöv et al. (Reference Antlöv, Brinkerhoff and Rapp2010). In Asia, NPOs also play an important role in channeling the voices of civil society to the government or influential leaders through establishing communication opportunities. Furthermore, we hypothesized a positive relationship between nonprofit and political participation regarding problem resolution, voting, petitions, protests, and forces. This finding confirms that nonprofit participation serves as the school of democracy (Jo, Reference Jo2020; Lee, Reference Lee2020) for facilitating participation in political activities in Asia.

Against the findings of positive relationships between nonprofit participation and political participation, heterogeneity remains in the types of nonprofits in which individuals may become politically socialized or mobilized in the authoritarian system. In the authoritarian system, only community, charity/religious, and political types of participation are found to have positive relationships with political participation, for instance. This finding adds a level of nuance to Curley’s (Reference Curley2018) and Kerkvliet’s (Reference Kerkvliet2015) findings that the roles of civil society in authoritarian regimes remained limited. Curley (Reference Curley2018) shows that a recent reform of the NGO law in Cambodia has shrunk the democratic space for civil society and provided power to the government authorities to ban activists of a local membership association from engaging in any political activities.

Lessons for Policies

This study provides the following lessons: First, developing a healthy and active civil society is essential to giving people a voice in policies. We find that NPOs serve as channels through which citizens can also express their views on public policies and affairs in Asia. By participating NPOs, citizens can legally and legitimately represent their NPO peers or communities to connect with various stakeholders in the policy-making process, including political leaders or other influential persons in society.

Second, to improve democratic development and political participation, it is necessary to pay more attention to NPO participation and development and the relationship between NPO participation and political participation in Asia. Such improvement comes from the diversity and accessibility of NPOs within a society. Certain NPOs have positive effects on political contact, while others have positive effects on political participation. Given the diversity in NPO types, it is necessary to ensure a healthy and supportive policy environment for the growth of NPOs and the development of NPO diversity. Governments and policy-makers need to recognize the legitimacy and functions of NPOs with a strong focus on advocacy or activism. The literature shows that NPOs in some Asian countries are established or controlled by the government (Ganesan, Reference Ganesan2017; Shin & Lee, Reference Shin and Lee2017). Also, allowing only certain types of NPOs that mainly serve to deliver public services to operate might not be genuinely beneficial for democratic development, as shown in the empirical data.

Third, the conditions that moderate relationships between NPO participation and political participation provide policy implications. Based on relevant literature, nonprofits are not simply providers of services but also potential vehicles for citizens to express their interests through connecting with political actors and exercising their civil duties through charities and religious nonprofits across different political environments. For instance, Suebvises (Reference Suebvises2018) finds that the development of civil society in Thailand positively affects citizens’ political participation. Suebvises (Reference Suebvises2018, p. 245) further argues that “the roles of government must be changed from controlling and directing the population to collaborate empowering and engaging with civil society.”

Study Limitations

Our findings are not entirely generalizable, and the current research has some limitations. First, we included two waves of cross-sectional data, but the respondents differed in the two waves; thus, the data are not longitudinal. Our analysis suffers from the problem of reverse causation. The causal relationship between NPOs and political participation cannot be established because it cannot be ruled out that a citizen with high political participation is more likely to participate in NPOs. Therefore, our study intends not to establish causal influence but to demonstrate an association relationship. Although the cross-sectional nature of our data prevents us from making strong causal arguments, the results from the ordered logistic regressions across different political systems suggest that the political environment moderates the relationships between nonprofits and political participation.

Second, our primary analysis is based on a single data source and thus might suffer from common method bias. To reduce such bias, we included two steps. We first conducted a principal component analysis, which helps estimate the common method variance (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). The variance in the first component is 0.065; thus, CMV is not an issue in this study since the underlying assumption was not met. We also include country-level data in political systems from other data sources, namely the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Index of Democracy.

The third limitation concerns the measurement of NPO participation. The Asia Barometer Survey does not contain information on the degree of NPO participation or a comprehensive list of NPO participation. For instance, a part-time volunteer at an NPO is less involved than the director of that NPO. The survey does not capture the degree and involvement of NPOs. A study incorporating the degrees and positions of NPO participation would enrich our understanding of the relationship between NPOs and political participation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings empirically contribute to the existing theories by building an empirical model to examine the relationship between nonprofit participation and political participation in the context of Asia. Theoretically, our findings further suggest a relationship moderated by the political environment in which nonprofits operate in Asia. Important implications of these results pertain to building the necessary NPO capacities. Social capital, social networks, and public participation theorists have stressed that NPOs provide connections and enable people to take collective action for a better democracy. Regulation, policies, and self-governance are required to cultivate a healthy NPO sector in terms of its growth, diversity, and accessibility to citizens.

Furthermore, future studies should focus on the growth and development of NPOs in different countries. For instance, what are the growth trends of various NPOs in each Asian county? Where do the resources and support come from for different types of NPOs? More importantly, who actually participates in different types of NPOs? Furthermore, scholars could develop a network of research to build cross-national datasets to develop nonprofit studies in Asia. Comparing NPO development will significantly enhance our understanding of the progress—or sometimes, setbacks—in democratic development in the studied countries.

Acknowledgments

I thank the HuFu Center for East Asia Democratic Studies at the National Taiwan University for East Asia Barometer data. Previous versions of this article were presented at the Civil Society and Democratization Workshop on August 12-13, 2021, and I am thankful for the helpful comments from the participants. More importantly, I thank Shawn Ho, Sinead O'Connor, Cindy Lo, and Serena Chen for data cleaning, coding, analyses, and literature review. Appreciation also goes to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

Funding

This study was funded by the Yushan (Young) Scholar Award, Ministry of Education, Taiwan, ROC (Grant Number: 110V0301) and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, ROC (112CD810-1) for the research and publication of this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix 1

See Table 3.

Table 3 Summaries of related studies by theories, roles of NPOs and democratic development (Selected articles from 70 reviewed articles)

Country |

Relevant theories/conceptual framework |

Roles of NPO |

Roles for political development |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Japan |

Political opportunity theory indicates that the success and failure of NPOs are primarily affected by whether or not political opportunities exist |

Advocacy, Policy process |

Through the expansion of the Democratic Party of Japan since the late 1990s, NPOs actively show varying degrees of support for policies |

Sohn et al (Reference Sohn, Jeong and Kim2017) |

Korea |

Social capital theory indicates that social capital is essential for enhancing the ability of democratic institutions |

Promote political participation |

Both formal and informal associations help impart political issues, cultivate organizational communications skills and facilitate direct political engagement |

Lee (Reference Lee2010) |

Philippines |

The democratic backsliding theory explains how a gradual decline in the quality of democracy can lead to authoritarianism |

Anti-democracy |

Civil society activists have been marginalized in the Philippines and even actively avoid criticizing the government |

Thompson (Reference Thompson2021) |

Thailand |

“Uncivil” society Chikhladze & Aliyev (2019) thrives when there is low popular participation in formal civil society |

Anti-democracy |

Thailand’s political situation is highly fragile due to a weak civil society. In 2014, this led to violent disruptions to electoral voter registration, voting, and counting activities |

Kongkirati (Reference Kongkirati2016) and Thompson (Reference Thompson2021) |

Indonesia |

Political mobilization theory explores what motivates participants to take particular political action |

Promote political participation |

NGOs actively worked with the government to support women candidates in the 2014 elections, including providing training to women candidates |

Hillman (Reference Hillman2017) |

Vietnam |

Political criticism refers to critiques of particular or relevant political issues, policies, political parties, or governments |

Advocacy, promoting participation |

An anti-corruption group formed in 2001 regularly publishes a magazine supporting democratization and critiquing government policy |

Kerkvliet (Reference Kerkvliet2015) |

Hong Kong |

Political culture theory (Lehman (1972) was adopted to describe political behaviors resulting from unique political culture |

Social movement |

Youth Hong Kong activists from different social classes play political roles and lead several citizen-led pro-democracy movements |

Lam-Knott (Reference Lam-Knott2019) |

Mongolia |

The five-phase spiral model explains how repressive governments gradually adopt internationally accepted human rights norms |

Democratic development, citizen participation |

Advocacy NGOs have created new public spaces for political engagement after the post-democratic revolution |

Heo (Reference Heo2014) |

Taiwan |

Social activism theory describes working with others to change society and foster opportunities for participation |

Advocacy |

The Fair Tax for Taiwan Coalition was founded to unite 17 influential advocacy groups |

Lin (Reference Lin2018) |

Singapore |

Social origins theory suggests that each country's unique history and culture leads to different relationships between the state and civil society |

Advocacy |

Despite significant state-imposed restraints, over three-quarters of Singapore charities participate in some form of advocacy |

Guo and Zhang (Reference Guo and Zhang2014) |

Cambodia |

Social activism theory describes working with others to change society and foster opportunities for participation |

Advocacy |

Cambodia’s civil organizations and groups play essential roles in upholding rights such as land rights, human rights, and labor rights for their communities |

Curley (Reference Curley2018) |

Malaysia |

Social capital theory indicates that social capital is essential for enhancing the ability of democratic institutions |

Democracy development, political participation |

Participation in voluntary associations has been key to changing the political landscape of Malaysia NPOs and NGOs use the Internet to express their political views |

Parnini et al. (Reference Parnini, Othman and Saifude2014) |

Appendix 2

See Table 4.

Table 4 Summaries of democratic development, state-NPO relation, and voter turnout rate

Country |

Democratic developmenta |

Economic developmentb |

Voter turnout ratec |

State-NPO relationd |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Presidential (%) |

Parliamentary (%) |

||||

Japan |

Full democracy |

High-income |

n.a |

55.97 |

Legal |

Korea |

Full democracy |

High-income |

77.20 |

66.21 |

Legal |

Philippines |

Partial democracy |

Lower-middle |

81.95 |

74.31 |

Legal |

Thailand |

Partial democracy |

Upper-middle |

n.a |

74.69 |

Legal |

Indonesia |

Partial democracy |

Lower-middle |

74.69 |

74.69 |

Legal |

Vietnam |

Authoritarian |

Lower-middle |

n.a |

95.60 |

Legal |

Hong Kong |

Hybrid regime |

High-income |

n.a |

30.20 |

Legal |

Mongolia |

Partial democracy |

Lower-middle |

59.35 |

59.35 |

Legal |

Taiwan |

Full democracy |

High-income |

74.90 |

74.86 |

Legal |

Singapore |

Partial democracy |

High-income |

94.80 |

94.80 |

Legal |

Cambodia |

Authoritarian |

Lower-middle |

n.a |

83.02 |

Legal |

Malaysia |

Partial democracy |

Upper-middle |

n.a |

82.32 |

Legal |

aThe Economist Intelligence Unit’s index of democracy

bThe world Bank: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

cInternational IDEA: https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/voter-turnout

2021 Legislative Council General Election (Hong Kong): https://www.elections.gov.hk/legco2021/eng/turnout.html

dSources from: Global Blockchain Compliance Hub, Council on Foundation, Japan NPO Center, Taiwan’s NGO policy: Lessons for Asia, The Law Affecting Civil Society in Asia, Mongolia – ICNL

Appendix 3

See Table 5.

Table 5 Description and measurement of variables

Variable |

Definition and measurement |

|---|---|

Dependent variables |

|

Political contact |

The degree of political contacts: 5 if the respondents reported five different political contacts; 4 if the respondents reported four different political contacts and so on; else 0 |

Political participate |

The degree of political participation: 5 if the respondents reported five different political participation activities; 4 if the respondents reported four different political participation activities and so on; else 0 |

Independent variables |

|

Community |

1 if the respondents reported any participation in a community or agricultural type of nonprofit; else 0 |

Club |

1 if the respondents reported any participation in a club, PTA, alumni, or cultural type of nonprofit; else 0 |

Charity and religious |

1 if the respondents reported any participation in religious, charities, and public interest type of nonprofit; else 0 |

Membership |

1 if the respondents reported any participation in professional, cooperative producer, cooperative consumer, occupational, volunteer, and business type of nonprofit; else 0 |

Political |

1 if the respondents reported any participation in a political party, unions, and candidate type of nonprofit; else 0 |

Control variables |

|

Trust-Low |

1 if the respondents reported scores ranged from 1 to 3 for trust; else 0 |

Trust-Middle |

1 if the respondents reported scores ranged from 4 to 6 for trust; else 0 |

Trust-High |

1 if the respondents reported scores ranged from 7 to 9 for trust; else 0 |

Social Network |

1 if the respondents reported 10–19 people or more; else 0 |

News |

1 if the respondents reported several times a week or every day for following news about politics and government; else 0 |

Internet |

1 if the respondents reported at least once a month, at least once a week, or almost daily for internet usage; else 0 |

Competence |

1 if the respondents reported likely, or very likely, the government will solve the most important problem the respondents identified within the next five years; else 0 |

Transparency |

1 if the respondents reported most of the time or always believing that government officials withhold essential information from the public view; else 0 |

Participate |

1 if the respondents reported somewhat agree or strongly agree to think that he/she can participate in politics; else 0 |

Politics |

1 if the respondents reported somewhat disagree or strongly disagree for believing that politics and government seem so complicated that a person cannot understand what is going on; else 0 |

Influence |

1 if the respondents reported somewhat disagree or strongly disagree for believing that people do not have any influence over what the government does; else 0 |

Wave3 |

1 if the respondents were in the wave 3 dataset; else 0 |

Japan |

1 if the respondents were in Japan; else 0 |

Hong Kong |

1 if the respondents were in Hong Kong; else 0 |

Korea |

1 if the respondents were in South Korea; else 0 |

Mongolia |

1 if the respondents were in Mongolia; else 0 |

Philippines |

1 if the respondents were in the Philippines; else 0 |

Taiwan |

1 if the respondents were in Taiwan; else 0 |

Thailand |

1 if the respondents were in Thailand; else 0 |

Indonesia |

1 if the respondents were in Indonesia; else 0 |

Singapore |

1 if the respondents were in Singapore; else 0 |

Vietnam |

1 if the respondents were in Vietnam; else 0 |

Cambodia |

1 if the respondents were in Cambodia; else 0 |

Malaysia |

1 if the respondents were in Malaysia; else 0 |

Measurement of the independent variables (nonprofit participation): respondents were presented with a card stating, "Can you identify the three most important organizations or formal groups you have participated in?" The card then listed the following types of organizations: political parties; community, religious, and faith-based organizations; clubs and associations; arts and cultural organizations; charities; public interest groups; unions and labor cooperatives; agricultural, professional, business organizations; parent-teacher associations (PTAs); producer cooperatives; consumer cooperatives; alumni associations; political campaigns; occupational organizations; and volunteer organizations (a total of eighteen types)

Measurements of control variables: To measure trust, the respondents were asked, "How much trust do you have in the following: the president (for presidential systems) or prime minister (for parliamentary systems), the courts, the national government in [capital city]?" To assess social networks, the respondents were asked, "On average, how many people do you have contact with on a typical weekday?" The study also includes the perception of the government's ability to resolve issues to measure the perception of government competence and transparency. Three additional questions are therefore included to capture the respondents' perceived competence in political participation: "I think I can participate in politics," “Sometimes politics and government seem so complicated that a person like me cannot understand what is going on,” and “People like me do not have any influence over what the government does.”

Appendix 4

See Table 6.

Table 6 Tabulation of missing values by countries

Total missing |

Japan |

Hong Kong |

Korea |

Mainland China |

Mongolia |

Philippines |

Taiwan |

Thailand |

Indonesia |

Singapore |

Vietnam |

Cambodia |

Malaysia |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Political Contact |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Political Participation |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Community |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Club |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Charity/Religious |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Membership |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Political |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Trust |

1156 |

77 |

104 |

14 |

427 |

7 |

12 |

109 |

160 |

115 |

45 |

36 |

22 |

28 |

Social Network |

628 |

9 |

26 |

8 |

186 |

16 |

7 |

20 |

149 |

55 |

30 |

108 |

1 |

13 |

News |

362 |

10 |

28 |

10 |

48 |

4 |

9 |

13 |

56 |

52 |

51 |

53 |

1 |

27 |

Internet |

1435 |

23 |

19 |

4 |

34 |

10 |

9 |

4 |

54 |

1,174 |

12 |

74 |

1 |

17 |

Competence |

2650 |

587 |

202 |

208 |

86 |

117 |

220 |

504 |

201 |

35 |

102 |

31 |

243 |

114 |

Transparency |

4567 |

94 |

362 |

40 |

1,628 |

148 |

39 |

177 |

294 |

823 |

147 |

499 |

110 |

206 |

Participate |

2348 |

48 |

177 |

35 |

662 |

34 |

15 |

105 |

271 |

389 |

162 |

366 |

15 |

69 |

Politics |

2316 |

51 |

140 |

28 |

804 |

37 |

20 |

73 |

182 |

352 |

98 |

425 |

48 |

58 |

Influence |

2238 |

47 |

146 |

43 |

699 |

31 |

21 |

91 |

203 |

412 |

94 |

368 |

19 |

64 |

Wave3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

The table includes the missing values before we dropped the observations with missing values for any variables we used. The missing values for the first two dependent variables were recoded to 0 for better interpretation. The missing values for election-every, election-most, and election-some are reasonable since these variables are factors from one survey question. The independent variable, NPO participation, is a dummy variable indicating participation in one specific organization; thus, there are no missing values. Hence, all missing values are from control variables: 1156 observations for trust, 628 for social network, 362 for news, 1435 for internet, 2650 for competence, 4567 for transparency, 2348 for participate, 2316 for politics, and 2238 for influence. These missing values were all dropped in the main analysis

Appendix 5

Distribution of NPO participation factors by country and region.

Note: This figure shows the NPO participation by country. Each country shows a different mix of NPO participation. It seems that the patterns of NPO participation are equally distributed in the full or partially democratic countries and regions. In Japan, the community (38.7%) accounts for most of NPO participation, followed by the club (29.1%) and membership (16.7%). In South Korea, club (54%) accounts for most of NPO participation, followed by charity and religion (24,3%) and community (9.8%). In Taiwan, charity and religion (33%) account for most of the NPO participation, followed by the club (23.9%) and political nonprofits (15.2%).

For those classified as partially democratic countries and regions, NPO participation patterns resemble similarities to those of fully democratic countries. In the Philippines, charity and religion (31.8%) account for most of the NPO, followed by the membership (23.2%) and club (22.8%). In Indonesia, community (31%) accounts for most of the NPO participation, followed by charity and religious (27%) and membership (18.6%). In Malaysia, community (29.9%) accounts for most of the NPO participation, followed by political (26%) and charity, and religious (18.2%). In Thailand, community (43.2%) accounts for most of the NPO participation, followed by charity and religious (20.2%) and membership (17.8%). In Singapore, club (27.6%) accounts for most of the NPO participation, followed by charity and religious (26.8%) and membership (23%). For Mongolia, political (45.1%) accounts the most of the NPO participation, followed by the membership (21.1%) and club (16.5%). In Cambodia, political (58%) also accounts for most of the NPO participation, followed by the community (34.8%) and membership (3.5%). In Vietnam, community (40.7%) accounts for most of the NPO participation, followed by political (21.9%) and club (16.8%). In Hong Kong, charity and religion (33.1%) account for most of the NPO participation, followed by the club (26.5%) and membership (15.5%). In those authoritarian or hybrid political systems, participation in political types of NPOs seems to account for a large proportion of the overall NPO participation, except in Hong Kong, perhaps because Hong Hong has been governed and influenced by the British system.

Appendix 6

See Table 7.

Table 7 Pairwise correlations (independent and control variables only)

Variables |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

(11) |

(12) |

(13) |

(14) |

(15) |

(16) |

(17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1) Community |

1.00 |

||||||||||||||||

(2) Club |

0.18*** |

1.00 |

|||||||||||||||

(3) Charity and Religious |

0.15*** |

0.14*** |

1.00 |

||||||||||||||

(4) Membership |

0.14*** |

0.13*** |

0.12*** |

1.00 |

|||||||||||||

(5) Political |

0.05*** |

0.02*** |

0.04*** |

0.04*** |

1.00 |

||||||||||||

(6) Trust_low |

0.03*** |

0.10*** |

0.03*** |

0.05*** |

− 0.03*** |

1.00 |

|||||||||||

(7) Trust_middle |

− 0.03*** |

− 0.06*** |

0.00 |

− 0.02*** |

0.00 |

− 0.68*** |

1.00 |

||||||||||

(8) Trust_high |

0.01 |

− 0.07*** |

− 0.05*** |

− 0.05*** |

0.07*** |

− 0.31*** |

− 0.33*** |

1.00 |

|||||||||

(9) Social Network |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.03*** |

0.04*** |

0.04*** |

0.00 |

0.01** |

− 0.01** |

1.00 |

||||||||

(10) News |

0.12*** |

0.08*** |

0.02*** |

0.07*** |

0.05*** |

0.06*** |

− 0.06*** |

− 0.03*** |

0.04*** |

1.00 |

|||||||

(11) Internet |

− 0.12*** |

0.15*** |

0.00 |

0.05*** |

− 0.02*** |

0.10*** |

− 0.05*** |

− 0.09*** |

0.08*** |

0.01* |

1.00 |

||||||

(12) Competence |

− 0.01 |

− 0.05*** |

− 0.02*** |

− 0.03*** |

0.01* |

− 0.11*** |

0.02** |

0.15*** |

− 0.02*** |

− 0.01 |

− 0.06*** |

1.00 |

|||||

(13) Transparency |

− 0.02*** |

0.04*** |

0.02*** |

0.01* |

0.00 |

0.16*** |

− 0.15*** |

− 0.10*** |

0.02*** |

0.03*** |

0.07*** |

− 0.08*** |

1.00 |

||||

(14) Participate |

− 0.01* |

− 0.02*** |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.09*** |

− 0.09*** |

0.04*** |

0.10*** |

0.08*** |

0.04*** |

− 0.03*** |

0.03*** |

− 0.02*** |

1.00 |

|||

(15) Politics |

0.00 |

0.07*** |

0.01 |

0.04*** |

0.03*** |

0.05*** |

− 0.05*** |

− 0.02*** |

0.00 |

0.06*** |

0.10*** |

0.00 |

0.03*** |

0.03*** |

1.00 |

||

(16) Influence |

0.01** |

0.05*** |

0.07*** |

0.05*** |

0.03*** |

0.01** |

− 0.01 |

− 0.01** |

0.02*** |

0.06*** |

0.06*** |

− 0.03*** |

0.02*** |

0.07*** |

0.27*** |

1.00 |

|

(17) wave3 |

0.10*** |

0.02*** |

0.03*** |

0.06*** |

0.07*** |

0.00 |

− 0.01 |

− 0.01** |

0.00 |

0.13*** |

− 0.17*** |

0.01* |

0.00 |

0.00 |

− 0.01 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

Appendix 7

See Table 8.

Table 8 Ordinary Logistic Regression: Political Contacts by Political Systems

Full democracy |

Partial democracy |

Hybrid regime or authoritarian |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

Political contact |

Political contact |

Political contact |

Political contact |

Political contact |

Political contact |

|

Community |

1.449*** |

1.33*** |

2.087*** |

|||

(.101) |

(.07) |

(.17) |

||||

Club |

1.23*** |

1.062 |

1.32* |

|||

(.07) |

(.064) |

(.189) |

||||

Charity and Religious |

1.589*** |

1.216*** |

1.777*** |

|||

(.103) |

(.067) |

(.261) |

||||

Membership |

1.584*** |

1.596*** |

.831 |

|||

(.117) |

(.091) |

(.147) |

||||

Political |

1.782*** |

1.861*** |

1.967*** |

|||

(.149) |

(.122) |

(.164) |

||||

Trust_low |

.992 |

.969 |

1.049 |

1.033 |

.631** |

.604** |

(.085) |

(.084) |

(.099) |

(.098) |

(.137) |

(.131) |

|

Trust_middle |

1.169 |

1.111 |

1.039 |

1.005 |

.69* |

.656** |

(.113) |

(.108) |

(.097) |

(.095) |

(.147) |

(.139) |

|

Trust_high |

1.267 |

1.188 |

1.257** |

1.193* |

.8 |

.727 |

(.271) |

(.257) |

(.133) |

(.127) |

(.174) |

(.158) |

|

Social Network |

1.386*** |

1.301*** |

1.201*** |

1.176*** |

1.075 |

1.045 |

(.077) |

(.073) |

(.047) |

(.047) |

(.064) |

(.062) |

|

News |

1.588*** |

1.497*** |

1.612*** |

1.544*** |

2.047*** |

1.874*** |

(.097) |

(.092) |

(.064) |

(.062) |

(.124) |

(.115) |

|

Internet |

.949 |

.936 |

1.065 |

1.067 |

1.014 |

1.05 |

(.054) |

(.055) |

(.045) |

(.046) |

(.072) |

(.076) |

|

Competence |

1.071 |

1.094 |

1.153*** |

1.176*** |

.842** |

.826*** |

(.085) |

(.088) |

(.055) |

(.057) |

(.057) |

(.056) |

|

Transparency |

.963 |

.969 |

1.067 |

1.071* |

1.202*** |

1.254*** |

(.053) |

(.054) |

(.043) |

(.043) |

(.069) |

(.072) |

|

Participate |

1.514*** |

1.448*** |

1.611*** |

1.578*** |

1.532*** |

1.459*** |

(.084) |

(.082) |

(.063) |

(.062) |

(.091) |

(.088) |

|

Politics |

1.151** |

1.127** |

1.085* |

1.074* |

1.166** |

1.087 |

(.064) |

(.064) |

(.047) |

(.046) |

(.08) |

(.075) |

|

Influence |

1.138** |

1.116* |

1.022 |

1.009 |

1.386*** |

1.362*** |

(.063) |

(.063) |

(.04) |

(.04) |

(.087) |

(.085) |

|

wave3 |

1.495*** |

1.481*** |

.88*** |

.882*** |

1.082 |

.87** |

(.08) |

(.081) |

(.034) |

(.035) |

(.064) |

(.055) |

|

Japan |

.807*** |

.683*** |

||||

(.056) |

(.054) |

|||||

Korea |

1.371*** |

1.638*** |

||||

(.093) |

(.116) |

|||||

Mongolia |

.403*** |

.372*** |

||||

(.028) |

(.026) |

|||||

Philippines |

.917 |

.918 |

||||

(.058) |

(.058) |

|||||

Taiwan |

||||||

Thailand |

2.061*** |

1.919*** |

||||

(.13) |

(.124) |

|||||

Indonesia |

.958 |

.597*** |

||||

(.069) |

(.05) |

|||||

Singapore |

.332*** |

.328*** |

||||

(.026) |

(.026) |

|||||

Vietnam |

20.652*** |

16.261*** |

||||

(2.192) |

(1.756) |

|||||

Cambodia |

9.446*** |

7.98*** |

||||

(.98) |

(.845) |

|||||

Malaysia |

||||||

Observations |

7951 |

7951 |

11,733 |

11,733 |

5664 |

5664 |

Pseudo R2 |

.023 |

.037 |

.06 |

.068 |

.137 |

.149 |

Standard errors are in parentheses

From the Chow-type Likelihood-ratio test, we examine the hypotheses that specify that all coefficients of a model do not vary between disjointed subsets of the data. So, the likelihood ratio test statistic is 268.48 (p = 0), indicating that the model split by democracy fits significantly better than the nested model

***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1

Appendix 8

See Table 9.

Table 9 Ordinary logistic regression: political participation by political regime

Full democracy |

Partial democracy |

Hybrid regime or authoritarian |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

Political participation |

Political participation |

Political participation |

Political participation |

Political participation |

Political participation |

|

Community |

2.148*** |

1.547*** |

1.952*** |

|||

(.124) |

(.08) |

(.158) |

||||