Introduction

Like its predecessor 2018, the political year of 2019 in Swedish politics was historic in several ways. The uniquely protracted government formation process was concluded in January. The Social Democrats/Socialdemokraterna (S)–Green Party/Miljöpartiet de gröna (MP) minority coalition continued in office, but only due to an agreement with the Centre Party/Centerpartiet (C) and Liberals/Liberalerna (L) which involved difficult concessions for the governing parties. This government constellation remained in office throughout the year, but its position was vulnerable with recurring threats of no‐confidence votes. The economy showed signs of a slowdown although fiscal stability was maintained.

Election report

Elections to European Parliament

Sweden's sixth election to the European Parliament (EP) took place on 26 May. The campaign was relatively quiet, certainly in comparison with the parliamentary election eight months earlier. The main themes were the climate, migration, welfare and crime prevention (Blomgren Reference Blomgren and Bolin2019). There was discussion about the balance of power between the European Union (EU) and its member nations, but the Swedish EU membership was not seriously debated. The two most EU‐sceptical parties, the Left Party/Vänsterpartiet (V) and the Sweden Democrats/Sverigedemokraterna (SD), no longer demanded a Swedish EU exit. Indeed, a clear majority of the electorate was in favour of continued EU membership. Turnout rose to 55.3 per cent, an increase of 4.2 percentage points compared with 2014, and the highest ever for an EU election in Sweden. Four parties, SD, the Moderate Party/Moderata Samlingspartiet (M), C and the Christian Democrats/Kristdemokraterna (KD), gained one seat each, SD making the biggest gain in votes. S held on to its position as the biggest party, while M and SD ended as the second and third biggest parties, respectively. L and MP made losses, the former keeping its representation in the Parliament by a narrow margin. The Feminist Initiative/Feministiskt initiativ (FI) lost its only seat after one period (Berg and Oscarsson Reference Berg, Oscarsson and Bolin2019).

Table 1. Elections to the European Parliament (Europaparlamentet) in in 2019

Notes: aPreviously named Folkpartiet Liberalerna (see Political Data Yearbook for Sweden 2015).

b On 1 February 2020, after the exit of the UK, Sweden's total number of seats increased from 20 to 21. The new seat went to the Green Party.

Source: Swedish Election Authority website, https://data.val.se/val/ep2019/.

Cabinet report

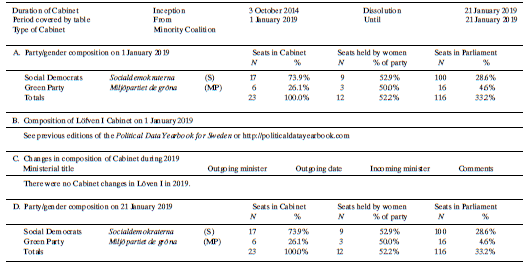

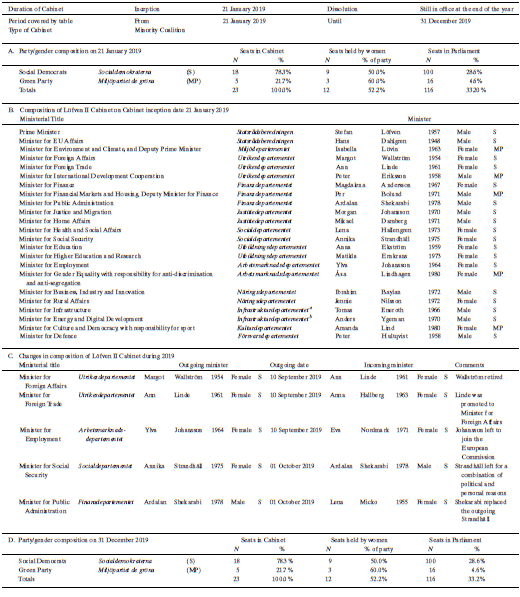

As described in the previous issue of the Political Data Yearbook, the government formation process after the 2018 parliamentary election was not concluded by the end of that year. At the beginning of 2019, the Löfven I minority Cabinet, consisting of S and MP, was still in office in a caretaker capacity. Negotiations between S, MP, C and L had begun in late 2018 and, on 11 January 2019, a four‐party agreement was presented that would allow the S‐MP government to continue with parliamentary support from C and L (see also Issues in national politics). Key to the Agreement was to keep V and SD from political influence, although only the former party is mentioned explicitly in the Agreement text. For this reason V threatened to vote against Löfven in the vote of investiture, but backed down after a meeting whose exact contents were not made public. The party still maintained a latent threat of future no‐confidence motions against the government. Löfven was voted in as Prime Minister on 18 January. S and MP voted for Löfven; M, SD, KD and one C member voted against, while C, V and L abstained. The number of votes against totalled 153, which was more than the votes in favour, but meant that Löfven was accepted as a government is only rejected if more than half of all 349 members (i.e., at least 175) vote against it. The Löfven II minority Cabinet was presented on 21 January. It contained 23 ministers, with the MP representation reduced to five because of its loss in the 2018 election. Six ministers departed, including the MP male spokesperson Gustav Fridolin, who had announced in 2018 that he would step down as joint party leader in May (see Political parties report). The new ministers included Anders Ygeman (S), who came back after leaving in connection with the National Transport Agency scandal in 2017 (see the Political Data Yearbook for that year), and the 70‐year‐old Hans Dahlgren (S), who has extensive foreign policy experience but had never before served in a Cabinet. The thus concluded government formation process had been the longest in Swedish history, lasting 131 days (Aylott and Bolin Reference Aylott and Bolin2019).

The Cabinet was reshuffled twice during the year. In September, the Minister for Foreign Affairs Margot Wallström and the Minister for Employment Ylva Johansson left the Cabinet. The highly experienced Wallström cited family reasons for stepping down, but there were disagreements about her ideological foreign policy, which included feminism, nuclear disarmament and criticism of Israel. The appointment of Minster for Foreign Trade Ann Linde as Wallström's successor was interpreted as a step towards a more ‘realpolitik’‐oriented approach, although the differences should not be overstated (Eriksson Reference Eriksson2019). Linde's vacated post was taken by the previously unknown Anna Hallberg, whose background was in business and banking. She did not have a political background, becoming a party member of S when joining the Cabinet (Marmorstein 2019). Ylva Johansson left to join the European Commission, where she later took the Home Affairs portfolio. She was replaced by Eva Nordmark, chair of the white‐collar union TCO. On 1 October, the Minister for Social Security Annika Strandhäll left for a combination of personal and political reasons. She had suffered a family bereavement, but also received criticism for the removal of the director‐general of the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (see also Parliament report). Strandhäll, who returned to her seat in Parliament, was replaced by the Minister for Public Administration Ardalan Shekarabi. His position was filled by Lena Micko, a member of the S party executive and holder of top positions in the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions.

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Löfven I in Sweden in 2019

Source: Swedish government website www.regeringen.se.

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Löfven II in Sweden

Notes: aInfrastrukturdepartementet was created on 1 April 2019. Between 21 January and 31 March, Eneroth was placed at Näringsdepartementet

b Infrastrukturdepartementet was created on 1 April 2019. Between 21 January and 31 March, Ygeman was placed at Miljödepartementet

Source: Swedish government website www.regeringen.se.

Parliament report

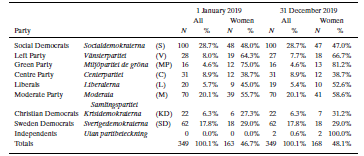

There were no important changes in the composition of the Riksdag. Two members, one from L and one from V, left their respective parties, but kept their seats as independents. Neither joined nor formed new parties. In contrast to 2018, when the Löfven I caretaker government saw its budget rejected, the budget process in 2019 went according to plan. The M‐KD budget that, instead of the government budget, had been adopted by Parliament in late 2018, was modified. The Spring Budget presented by the government in April and the Main Budget presented in September were both passed. There was still turbulence, with no‐confidence motions tabled against two S ministers. The first was tabled by M against the Minister for Social Security Annika Strandhäll. The background was Strandhäll's dismissal in April 2018 of the Swedish Social Insurance Agency Director‐General Ann Marie Begler. Strandhäll's critics argued that Begler had been made a scapegoat for carrying out government instructions to reduce the number of people on sick leave, which proved unpopular. The debate centred on whether the organization led by Begler had gone too far, or merely followed its instructions, and if the principle of an independent civil service had been violated. Strandhäll narrowly survived the no‐confidence vote, held on 28 May 2019. A total of 172 members (M, KD, L and SD) voted against the minister, which was three short of the 175 required for dismissal. Only S and MP voted against the motion, while V and C passively supported the minister by abstaining. The abstention by C was the decisive factor, as V had always seemed less likely to vote against her. Strandhäll's handling of the Begler affair had also been referred to the standing Committee on the Constitution, as part of its annual scrutiny of the government. In its report, presented on 4 June, the committee unanimously criticized Strandhäll (Lindstam Reference Lindstam2019). She left the government on 1 October, albeit for partly different reasons (see Cabinet report). The second no‐confidence motion was tabled in November, by SD against the Minister for Justice Morgan Johansson. The background was a series of gang‐related shootings and bombings. SD argued that Johansson, whose responsibilities include the police force, had not proved up to the task of dealing with violent gang crime. The motion was supported by M and KD. On 15 November, these three parties voted to dismiss Johansson, representing a total of 151 votes, which was 24 fewer than the required majority. S, MP, L and one independent voted against, while C, V and one independent abstained (Hamidi‐Nia Reference Hamidi‐Nia2019).

A third no‐confidence vote seemed possible when V, on 21 November, presented five demands to refrain from seeking to dismiss the Minister for Employment Eva Nordmark. V did not on its own have enough seats to table a no‐confidence motion, but when SD, M and KD indicated a willingness to follow V, the threat became real as these four parties together command a total of 181 seats, six more than the 175 required for dismissal. V's demands focused on a draining of resources to the Swedish Public Employment Service (SPES), which was forced into staff cuts and was set to close many of its offices around the country. A partial reason was that the M‐KD budget, adopted in late 2018, cut funding to the SPES, but in addition the January Agreement includes a profound reform of its organization, which includes a shift towards private labour agencies. The recently appointed Nordmark had not herself drawn up these plans, but she had been recruited to the government to carry them out. M, KD and SD saw V's criticism as an opportunity to damage the government and its support parties, while V felt the need to show its independence of the government and the January Agreement. On 5 December, V and M announced their intention to table a no‐confidence motion. Four days later V backtracked after the government had delayed the reform plans by one year. V, however, declared itself ready to take new no‐confidence initiatives if the retracted proposals were to return (Ahlander et al Reference Ahlander2019).

Table 4. Party and gender composition of (Riksdagen) in Sweden in 2019

Sources: Swedish Parliament website www.riksdagen.se; Swedish Election Authority website, relevant document available at https://data.val.se/val/val2018/nulaget/avgangna_ledamoter.xls.

Political party report

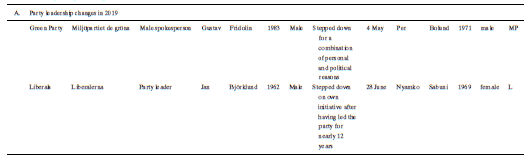

Two parties changed leader in 2019. Jan Björklund, L leader since 2007 and minister in the Alliance government 2006–14, announced his resignation on 6 February. On 24 June, the party's selection committee proposed Nyamko Sabuni as Björklund's successor, and she was appointed unopposed at an extraordinary party congress on 28 June (Hållbus Reference Hållbus2019). Born in Burundi, Sabuni had served in the Alliance government 2006–13 (see the Political Data Yearbook for 2006 and 2013), but been away from frontline politics in the past six years.

In October 2018, the MP male spokesperson since 2011, Gustav Fridolin, had announced that he would step down at the party congress in May 2019. He had served in the S‐led Löfven I government from its formation in 2014, but was not included in Löfven II due to his upcoming departure as spokesperson. On 4 May, the MP congress appointed Per Bolund as Fridolin's successor. The decision was not unanimous, his relatively unknown opponent Magnus Wåhlin receiving one‐third of the delegate votes (Pettersson Reference Pettersson2019). Bolund is a minister in the Löfven II Cabinet (Table 3), and also served in Löfven I.

Institutional change report

Besides the institutional change reported in the previous Political Data Yearbook, several changes in the Freedom of Speech Act and Freedom of the Press Act, confirmed by Parliament on 14 November 2018, took effect on 1 January 2019. Many of the changes were of a technical nature but, among other things, the crime of persecution of population groups (Hets mot folkgrupp) was extended to include non‐binary gender, and there were changes to regulations about the online publication of material with relevance to personal integrity (Aftonbladet 2018).

Table 5. Changes in political parties in Sweden in 2019

Sources: See media sources cited in text.

Issues in national politics

The January Agreement, which secured the installation of the Löfven II Cabinet (see Cabinet report), concluded the break‐up of the four‐party centre‐right Alliance, launched in 2004 and in government 2006–14 (see the respective years in the Political Data Yearbook). The main reason for the decision by C and L to support a continued S‐MP government was to keep SD from political influence, which would have been more difficult in a government constellation not including S. Differences in relations to SD seemed to be the key dividing line between the former Alliance parties, where M and KD adopted a more pragmatic approach than C and L. The leaders of KD and M both held substantive policy meetings with SD leader Jimmie Åkesson in 2019. This gave SD an unprecedented degree of legitimacy and led to unconfirmed speculations about the possible future formation of an M‐KD‐SD ‘conservative bloc’. The 73‐point January Agreement contained several important concessions, especially for S. The reform of the SPES has been mentioned (see Parliament report), but it also included changes to the labour market regulations, with increased freedom for employers to hire and fire, deregulation of the housing rental market, and a revised taxation system (Fritzell and Palme Reference Fritzell and Palme2019). These and other proposals represent a rightward turn for S, and some representatives of the main governing party admitted that they did not like some parts of the Agreement. Internal criticism within S was met with the argument that an M‐led government with influence from SD was an even worse option. C and L faced a difficult task to explain to their voters why they had allowed S and MP to continue in office, but they too highlighted the exclusion of SD from political influence. The barring of V was also important, and a key part of the C and L narrative to justify the agreement was that both flank parties were kept from influence. They could also claim significant policy successes in the Agreement, but their voters were not convinced and especially L suffered in the polls. Large parts of the reform package in the January Agreement were scheduled to be completed by the 2022 election. Fact‐finding Commissions of Inquiry were launched to prepare the necessary legislation, but the timetable seemed tight. The January Agreement meant that political stability was restored after the preceding turbulence, but as shown by the recurring threats of no‐confidence votes (see Parliament report) the Löfven II Cabinet was not in a secure position. The four ‘January parties’ S, MP, C and L were all struggling in the polls, and there was a remaining threat that V would again join forces with other parties to table no‐confidence motions.

The economy slowed somewhat. In December 2019, the National Institute of Economic Research (NIER) reported a 1.2 per cent growth in gross domestic product (GDP) for 2019, and projected a further slowdown to 0.7 per cent for 2020 (NIER 2019). Inflation, measured as 12‐month changes in the consumer price index (CPI), peaked at 2.2 per cent in May, then sank to 1.4 per cent in August, but had again increased to 1.8 per cent by the end of the year (SCB 2020). This was within the target rate of +‐2 per cent set by the central bank, Riksbanken, which increased the Repo (repurchase agreement) interest rate from –0.50 per cent to –0.25 per cent on 9 January 2019 (announced in December 2018). This level was maintained throughout 2019, but on 19 December an increase to 0 per cent was announced, to take effect on 8 January 2020 (Riksbanken 2019, 2020). Fiscal stability was maintained. The National Debt Office (NDO) reported a fiscal surplus of SEK112 billion (approximately €11 billion), an increase of SEK32 billion compared with 2018 and the fourth consecutive annual surplus. National debt maintained its downward trajectory, and sank by SEK149 billion to SEK1113 billion (approximately €111 billion) at the end of 2019. Relative to GDP, it sank from 26 per cent to 22 per cent, the lowest level since 1976 (NDO 2020: 6). Unemployment, however, began to grow. In January 2020, the SPES announced that the overall level of unemployment, as a proportion of the population aged 16–64 years, rose from 6.4 per cent in 2018 to 6.8 per cent in 2019 (SPES 2020:14).