Introduction

Advance decision-making in mental health

Advance decision-making for mental health crises is one of the few medico-legal interventions which has widespread support from service users (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Gaillard, Vollmann, Gather and Scholten2023), clinicians (Swanson et al. Reference Swanson, Swartz, Hannon, Elbogen, Wagner, McCauley and Butterfield2003), and academic researchers (Henderson et al. Reference Henderson, Jackson, Slade, Young and Strauss2010). There is increasing international interest in advance decision-making due to the potential to increase service user autonomy (Ward, Reference Ward2017), improve the therapeutic alliance (Swanson et al. Reference Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen, Van Dorn, Ferron, Wagner, McCauley and Kim2006), and reduce compulsory admission (de Jong et al. Reference de Jong, Kamperman, Oorschot, Priebe, Bramer, van de Sande, Van Gool and Mulder2016, Molyneaux et al. Reference Molyneaux, Turner, Candy, Landau, Johnson and Lloyd-Evans2019). However, implementation has consistently proved challenging due to apprehension about practical and conceptual issues (Thornicroft et al. Reference Thornicroft, Farrelly, Szmukler, Birchwood, Waheed, Flach, Barrett, Byford, Henderson, Sutherby, Lester, Rose, Dunn, Leese and Marshall2013, Nicaise et al. Reference Nicaise, Lorant and Dubois2013, Lenagh-Glue et al. Reference Lenagh-Glue, Potiki, O’Brien, Dawson, Thom, Casey and Glue2021, Shields et al. Reference Shields, Pathare, van der Ham and Bunders2014).

Self-binding directives

Arguably the most conceptually controversial and practically challenging form of advance decision-making is a ‘self-binding directive’ (SBD), also called a ‘Ulysses contract’. This is a type of clause that may be included in advance decision-making documents (often known as psychiatric advance directives). The name originates from analogies with the ancient Greek myth in which Ulysses ordered his crew to bind him to the mast of his ship and to ignore his future requests to untie him when under the influence of the sirens’ call.

The Ulysses myth is understood to be similar to the dilemma faced by those who experience episodes of severe mental illness. It is common for those living with relapsing and remitting illnesses such as bipolar disorder (hereafter ‘bipolar’), psychosis, or severe depression to experience times when they are relatively symptom-free, functional, and well able to make decisions about their mental health care. However, during episodes of illness, people with such mental health conditions can lose the mental capacity (sometimes known as competence) to make these decisions and their preferences can stand in sharp contrast to those expressed when they are well (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Freyenhagen, Richardson and Hotopf2009, Reference Owen, Richardson, David, Szmukler, Hayward and Hotopf2008). An SBD allows the person to anticipate a future time when hospital admission and/or treatment will be required, to predict that at that future time they will refuse admission/treatment, and to request that health care professionals then override their contemporaneous wishes and provide admission/treatment in accordance. In effect, they can use the SBD clause in an advance decision-making document to make an advance request for involuntary care (Gergel and Owen, Reference Gergel and Owen2015). It is important to note that the terms ‘binding’ or ‘directive’ in this context are personal or relates to ‘the person’ in the sense given by the Ulysses story. It is not, or at least not necessarily, binding in the legal sense of confining decision makers given roles in mental health law to a contract or to an order. Viewed legally, an SBD is a request for involuntary treatment that should inform but not fetter such decision makers.

Ethical and empirical evidence on self-binding directives

A systematic review of ethical reasons for and against SBDs found 50 articles on this topic from multiple disciplines (Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Gieselmann, Gergel, Owen, Gather and Scholten2023). Key reasons in favour of SBDs included: promoting service user autonomy, promoting wellbeing, and reducing harm, improving relationships, justifying coercion, stakeholder support, and reducing coercion. Key concerns were: diminishing service user autonomy, unmanageable implementation problems, difficulties with assessing mental capacity, challenging personal identity, legislative issues, and causing harm. The most cited controversy was about whether SBDs enhance or diminish the service user’s autonomy. On the one hand, concerns were raised that SBDs can diminish negative liberty (i.e. one’s ability to do what one wants at a given point in time, free from interference from others). On this view, SBDs are a paternalistic tool that can increase psychiatric power to overrule a service user’s contemporaneous wishes. On the other side were those who argued that SBDs can enhance long-term autonomy (i.e. one’s ability to live according to one’s own life plans) through supporting the more authentic wishes of an individual’s well self.

The majority of the articles included in the systematic review were non-empirical, conceptual papers. However, mounting evidence from empirical work with service users and other stakeholders has begun to inform the debate and demonstrate that most find SBDs intuitive and helpful (Gergel et al. Reference Gergel, Das, Owen, Stephenson, Rifkin, Hindley, Dawson and Ruck Keene2021) (Scholten et al.). Recommendations on SBDs have been formulated using the available evidence, but these have not been tested in practice (Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Gieselmann, Gergel, Owen, Gather and Scholten2023) (Scholten et al. Reference Scholten, Efkemann, Faissner, Finke, Gather, Gergel, Gieselmann, van der Ham, Juckel, van Melle, Owen, Potthoff, Stephenson, Szmukler, Vellinga, Vollmann, Voskes, Werning and Widdershoven2023). There is currently no empirical work that examines the lived experience of actually using SBDs in a mental health crisis and service users’ retrospective views of the process.

Policy context in England and Wales

In England and Wales, the setting for this case report, there is an urgent need to address this issue. This comes in the wake of increasing support for advance decision-making and government commitment to reforming the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA) (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Gergel, Stephenson, Hussain, Rifkin and Keene2019). An independent review of this legislation concluded that introducing statutory support for service user advance decision-making was a key change that should be implemented. The recommendation was that service users be supported to create ‘Advance Choice Documents’ (ACDs) as a vehicle to express their advance wishes about care and treatment if they were detained under the MHA (Wessely et al. Reference Wessely, Gilbert, Hedley and Neuberger2018, Care DoHaS, 2021, Care DoHaS, 2021). It is vital that SBDs are considered when making policy decisions about the introduction of ACDs. This is because of the evidence that significant numbers of service users are likely to want to self-bind and it is a more complex and controversial form of advance decision-making (Gergel et al. Reference Gergel, Das, Owen, Stephenson, Rifkin, Hindley, Dawson and Ruck Keene2021, Hindley et al. Reference Hindley, Stephenson, Keene, Rifkin, Gergel and Owen2019). Services must be equipped to face this challenge and support service user wishes.

Aims

To help address this gap in the evidence base and form a foundation for future empirical work we present this first case report of an SBD. We have the following aims:

-

1. To report on the prospective and retrospective service user experience of making and using an SBD.

-

2. To compare the findings of this case report with the relevant arguments set out in a systematic review of reasons for and against SBDs.

Methods and context

Contextual information on the SBD process

The subject of this case report, ‘Jessica’ (not her real name), was a participant in the Crisis PACk (Crisis Preferences for Admission, treatment and Care) Study in South East London. This study comprised a clinical Quality Improvement Project on the implementation of ADM documents which included an SBD clause (i.e. Crisis PACks) and a qualitative research study on stakeholder (service user, clinician and carer) experience of these documents. Out of all the participants, Jessica’s case was selected to present as it is a fairly typical case which clearly captured the experience of self-binding within the follow-up period; i.e. Jessica had a document in place during a relapse and the time period when conducting a follow-up interview was possible. Jessica was also willing to be contacted and keen to support publishing her story. She wishes to raise awareness of SBDs and her experience with mental health services to help others in similar positions. This case study draws on interviews obtained during the Crisis PACk qualitative research study. These were interviews carried out with service users, treating clinicians and carers before an ADM document was made, after the document was made and then during the follow-up period. These interviews were thematically analysed in groups according to time point (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). They were coded by an interdisciplinary team with expertise in psychiatry, philosophy, and lived experience. Previous publications provide further detail including study protocol and findings (Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Gergel, Ruck Keene, Rifkin and Owen2022). For this case study the interviews relevant to Jessica were re-analysed by one person (LS) according to the time points (before the document was made, immediately afterwards, and then from an interview during a follow-up period). Details from clinical records during the period of crisis were also reviewed. As well as analysis of the individual time points the case was considered as a whole narrative. The initial analysis was discussed within the authorship team and with Jessica herself to draw out salient themes. The case study is structured as a narrative that runs longitudinally through time. This reflects both the unfolding experience of making and using an SBD and the order in which data was collected and analysed. Of note, only the clinical details which Jessica approved are included in the write up, some details have been omitted to protect confidentiality and according to her preference.

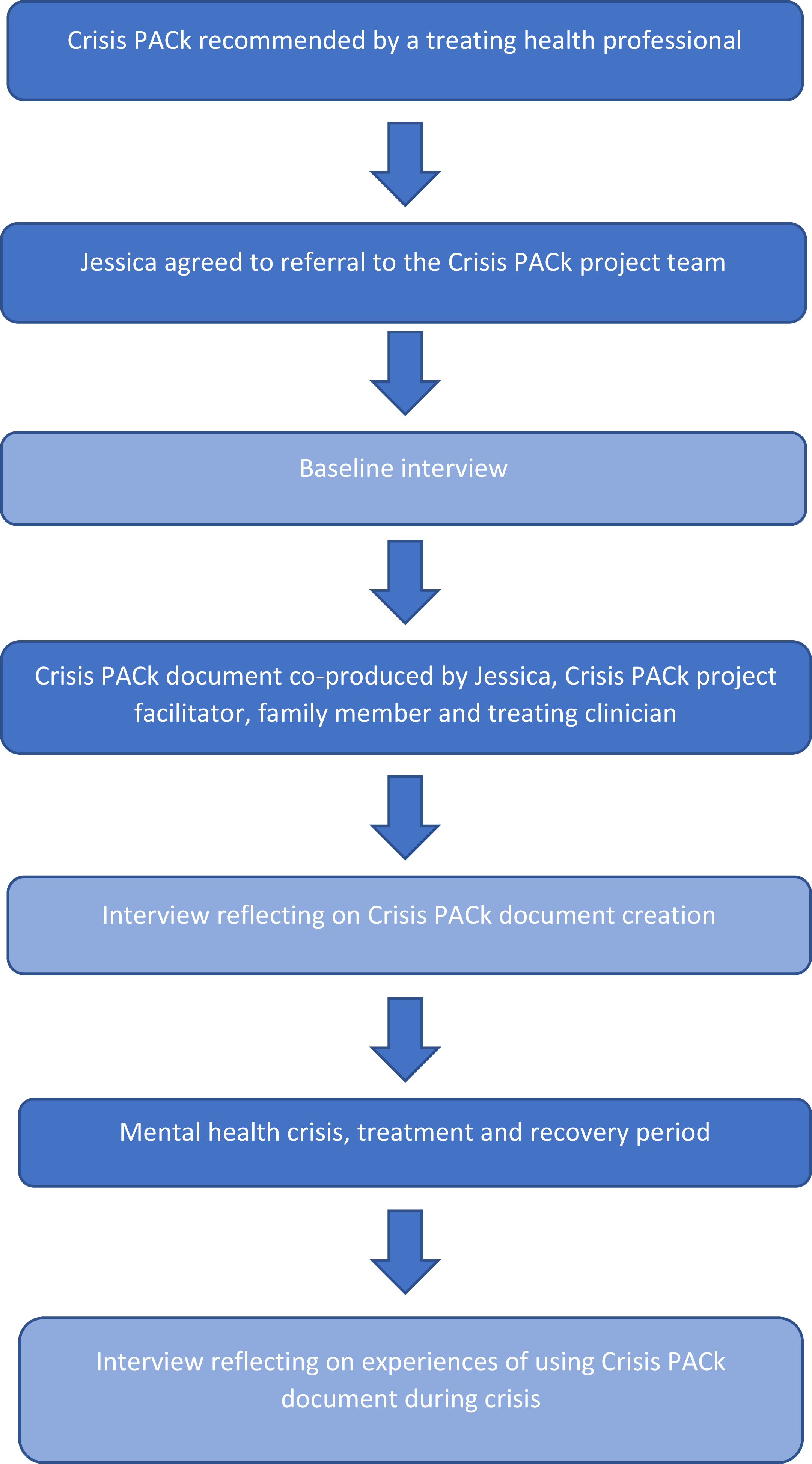

Jessica’s journey through the study is summarised in the figure below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Summary of Jessica’s journey through the Crisis PACk study.

SBDs are not legally supported in England and Wales. Accordingly, in the Crisis PACk study, the ADM document acted at the interface between the two relevant pieces of legislation: the Mental Capacity Act, 2005, (MCA) and the MHA. A summary of how this document functioned at this interface to support self-binding is set out below.

First are the sections that function as Advance Statements within the meaning of the MCA. This includes preferences for when they would want an MHA Assessment to take place. In effect, they are making an Advance Statement requesting a particular form of care; the application of the MHA and compulsory admission.

Second is a ‘personalised capacity assessment’. This section invites service users to describe particular patterns of thought, speech, and behaviour that they know they display when they have lost the capacity to make decisions about their care and treatment. The hope is that professionals will be guided from generic assessments of capacity towards the service user’s individual presentation.

Third is the ‘personalised risk assessment’. This can inform judgements about the kind of risks that may occur if admission is not implemented during MHA assessment.

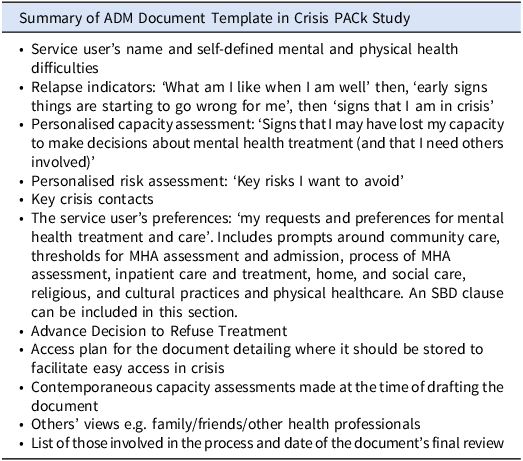

The Crisis PACk template is summarised in Table 1 with full details available in previous publications. (Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Gergel, Ruck Keene, Rifkin and Owen2022, Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Gergel, Keene, Rifkin and Owen2020).

Table 1. Summary of ADM document template in crisis PACk study

Contextual information on local psychiatric services

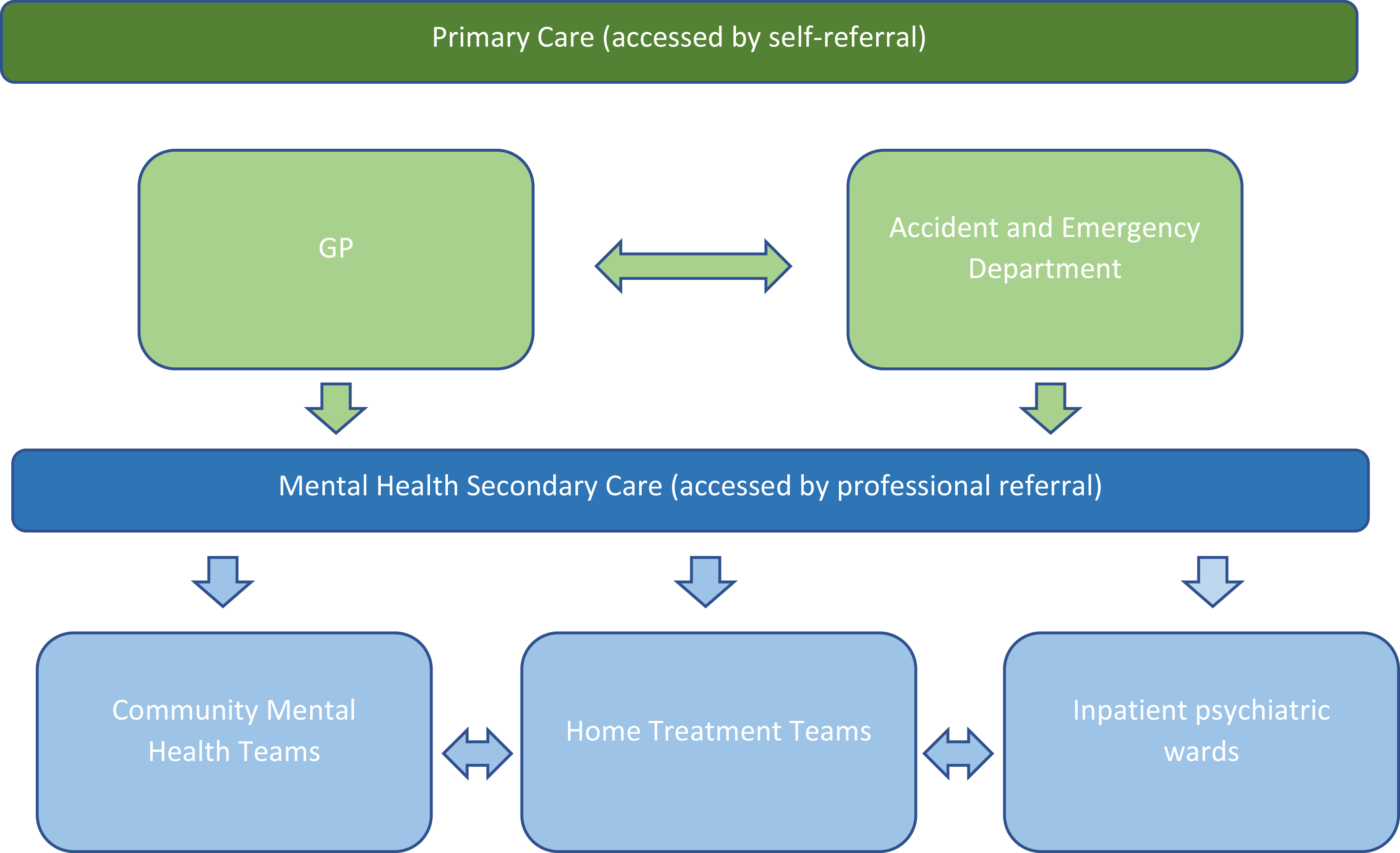

The Crisis PACk study took place in South East London, England. In this setting services are provided free by the National Health Service England (NHS-E). The NHS-E has a complex structure (NHS England, 2023) which, for the purposes of clarity and international understanding, can be understood as divided into the basic tiers of primary and secondary care (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sketch of pathways to care for adults with severe mental illness in England.

Secondary mental health care is comprised of Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) providing routine care, community teams providing intensive care (Home Treatment/Crisis Teams) and inpatient units. Service users can be admitted informally (i.e. voluntarily) or detained under the MHA. In England and Wales, detention under the MHA requires an assessment with two doctors and an Approved Mental Health Professional (often a specialist social worker) in attendance who all reach a consensus that it is necessary and lawful.

In a mental health crisis, it is common that a service user can be seen and assessed by multiple teams and staff in primary and secondary care settings. The crisis pathway experienced by Jessica is relatively typical, according to the authors’ experience of clinical work in mental health services.

Ethics, data use, and service user involvement

Ethical approval for the Crisis PACk qualitative research interview study was granted by Camberwell and St Giles ethics committee (REC reference 19/LO/1142.). Initial approval was granted on 03.09.2019, with an amendment approved on 04.08.2020 to allow the research to continue under pandemic restrictions. Governance and approval for the Crisis PACk Quality Improvement Project were provided by the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Quality Improvement team.

Direct quotes taken from the qualitative research interviews are used to illustrate key points in this case report. We also use understanding gained from field notes and informal communications with study participants, e.g. follow-up emails with professionals involved in Jessica’s crisis management. We do not quote directly from any confidential medical records.

‘Jessica’ was fully aware and involved in the creation of this article. She was asked for consent in advance of producing the first draft, consulted on further drafts, and approved the final draft. She has given informed consent to publish in accordance with the journal’s procedures.

The case report was written with reference to the CARE case report guidelines. (Gagnier et al. Reference Gagnier, Kienle, Altman, Moher, Sox and Riley2013)

Case report

Background

Jessica is a White British woman in her fifties, educated to degree level. She has held several professional roles and is a homeowner. She is a mother of two dependent children. She was widowed and is now a single parent. At the time of the project, she was unemployed but about to start a new job.

Jessica has lived with a diagnosis of bipolar for several decades and at the start of the project had needed four previous admissions, one of them under the MHA. She had her first experience of mania followed by depression in her early twenties. She did not require hospital care at that time. Her second, and most severe, experience of mania was several years later in the context of a high-pressure job, when she was hospitalised under the MHA. Following this, she became severely depressed and suicidal, requiring several admissions. Jessica experienced manic episodes with psychotic symptoms in the postnatal period with both of her children but managed these with home treatment. Jessica was then well for several years, but in 2019 became manic and then depressed in the context of work stress. This was exacerbated by the loss of a family member during the pandemic and anxiety about loved ones becoming unwell with COVID-19. She also experienced financial stress after leaving one job and losing another because of illness. It was in the wake of this episode that Jessica started working with a psychiatric community team and was referred to the project. In terms of medication, Jessica finds that her symptoms are relatively well maintained on a combination of a mood stabiliser (Sodium Valproate) and antipsychotic medication (Quetiapine).

Previous experience of mental health services

Jessica reported mixed experiences with mental health services. She found her previous inpatient care difficult. After her first admission in 2000, she saw the same psychiatrist and psychologist regularly, which she valued. She reflected that during her most recent episode, she noticed a shift in mental health provision, as she did not see a consistent psychiatrist and the care felt ‘rationed’. She had to travel to unfamiliar care settings rather than being offered home visits. She found it difficult to access psychological therapy because she had a diagnosis of bipolar. She also found it frustrating not to be able to talk to the psychiatrist responsible for her care directly. Her view of the current mental health system is that ‘something’s gotten lost…in terms of care. It feels very rigid, it feels quite impersonal’. So, for Jessica the project offered a valuable opportunity to have time with a psychiatrist and discuss her care and crisis plans in more detail.

Before drafting the ADM – Prospective views

Although Jessica recalled having previously made care plans and crisis plans with professionals, these were largely formulated by professionals and contained generic recommendations (e.g. that if she felt unwell, she should book a GP appointment). She was recommended for the project by her CMHT. The Crisis PACk was the most comprehensive advance decision-making document that she has made. In an initial interview, Jessica expressed her hopes that the document would ‘put in black and white what this illness does to me, and what it’s all about, and the various triggers…it would be good to perhaps help mental health professionals know what works and what doesn’t work for me’. In past episodes Jessica had found that when symptoms of mania escalated, this had had serious consequences for her professional and personal life. She had just been offered a new job and wanted to be open to any intervention that might help ensure that if she became unwell she got the appropriate help as soon as possible to reduce the risk of losing this job. As will be discussed, the help she had in mind included input from community services as well as inpatient admission. She was aware that when she is unwell she may refuse admission and wanted to use an SBD to ensure admission was timely to prevent these harms.

Jessica felt confident involving mental health professionals in the process of making the document. She was unconcerned about a potential power differential, although she raised the issue that this would be different were she not so well: ‘I’m relatively well now… I can sit in a meeting and hold my own…and…feel that I have a voice…much more so than when I’m not well. When I’m not well, that is not the time to be having these sorts of meetings.’ One aspect she anticipated would be difficult for her was facing the reality of her illness and what had happened to her: ‘the hardest thing is that it’s about you… you’re kind of objectively looking at yourself…realising there is a very serious illness lying in the background…that is… quite distressing’. Despite this, Jessica felt she was willing to talk about her illness and manage this potential distress.

Jessica was asked for her views on fluctuating capacity and personalised mental capacity assessments to anticipate loss of capacity. This was intuitive for her and she was able to reflect on how different she might appear when manic or depressed and how this might impact her decision-making: ‘when I’m manic I’m very hyper, and very agitated, and very talkative. I can come across as a little bit shouty…and definitely disinhibited…so I might be saying what’s on my mind, but it’s certainly not got any kind of controls…when I’m depressed I’m..non-communicative and…passive’.

In interviews Jessica discussed that she knew her attitude to medication can be different when unwell: ‘there is a difference definitely when I am relatively well, making decisions, putting forward a plan, agreeing to x,y,z medication to actually when I’m ill’. She gave the example that when she is getting unwell with mania, she is commonly prescribed Olanzapine, which causes significant weight gain. When manic, she prioritises preventing weight gain over calming the manic symptoms: ‘and that’s when you start to self-medicate. And that’s probably the glitch…I should stay on that drug but then I take myself off it when I’m in that situation because I just don’t want to be fat’.

In an interview after making her document, Jessica was asked to predict how she might view it if she were to become manic again. Her view was ‘your unwell self can’t even compute what’s in the plan…it’s another reality altogether…I guess the only way to try to explain that is…I’ve never taken LSD… but it’s probably a bit like that… and you’re hallucinating…so it’s hard to agree with any plan when you’re in that state’. She was also specifically asked about how professionals should respond if she contradicts her document when in an unwell state. Jessica was very clear, ‘they need to follow the plan I wrote when I was well…because that’s me being my best friend, and me being my own carer and me being my own mother…that’s me in my sane mind, making decisions for me when I’m unwell’.

Drafting the document

The document was initially drafted in an online one-on-one session with an independent facilitator. A meeting was then arranged with Jessica, her CMHT consultant, facilitator, and a family member. During this meeting, concerns arose about Jessica’s mental state. Jessica was well able to participate and retained basic decision-making capacity around her future treatment and care. It became clear, however, that Jessica was experiencing a period of particularly low mood and that this was subtly but significantly impacting her approach to advance decision-making. For example, her ability to imagine recovery from the episode and to generate a range of possible care outcomes, negative and positive, seemed hampered. Therefore, the meeting was postponed to allow Jessica to recover and ensure an authentic approach to decision-making.

Following this initial meeting, Jessica’s mental health deteriorated and she needed referral to a Home Treatment Team to manage her low mood. There was a reflection from clinicians involved that the process of meeting to discuss the document and discussing crisis care pathways may have increased Jessica’s awareness of crisis services that did exist and were available to her. This in turn may have meant Jessica felt that she could be more open about her depression and reach out for help.

In the second meeting, it was clear that Jessica had recovered and was able to express her wishes in a richer and clearer way. There is an update recorded on the document stating ‘less depressed, and my cognitive thinking is on the return. I am thinking more clearly and not in that foggy depressed state I was in’.

When drafting the document, Jessica described signs that she is experiencing mania as ‘I spend lots of money, experience sleeplessness, I invite random people into my life, I have excesses of energy’. In the document Jessica states: ‘If am I very very manic, psychotically manic, that is when I need to be in hospital.’ Key shared recommendations were around rapid responsiveness in crisis and increasing doses of specific medications that Jessica found tolerable in terms of side effects. Jessica expressed a preference that in a crisis, she would be most likely to accept benzodiazepines (Clonazepam) and an increased dose of her regular antipsychotic (Quetiapine). Her psychiatrist endorsed this and provided recommendations around dosage. Jessica did not make an outright refusal but cautioned against the prescription of one particular antipsychotic in a crisis (Olanzapine). This was because she was unlikely to comply with this medication when unwell due to the side effect of weight gain.

Jessica did wish to make an advance decision to refuse treatment with ECT. She had never had ECT and this was not expected to be part of her treatment in the future. However, a family member had experienced it during treatment for their mental illness and she did not like the idea of it.

Views after drafting the document

Jessica reported finding the process of making her document as ‘gentle and supportive’. She valued having psychiatric input and experienced this as ‘putting a big gold stamp on it’. Jessica also valued the fact that the process of making the document took several weeks. This afforded her time to think through her choices and discuss them with friends and family. She felt empowered, reporting ‘you own the process’. She also strongly endorsed the SBD elements in the document, saying, ‘they need to follow the plan I wrote when I was well’. The document was completed and uploaded to her mental health electronic health records on 12/08/2021. An alert was placed in the records stating: ‘Jessica has made a Crisis Pack (collaborative advance directive). Stored under correspondence. STAFF MUST READ if she presents in crisis or is admitted. Contains Advance Statements valid under MCA’. A copy was also sent to her GP, uploaded to a pan-London health advance decision-making document repository (Coordinate My Care), given to the service user, and trusted family members.

Follow-up and outcomes

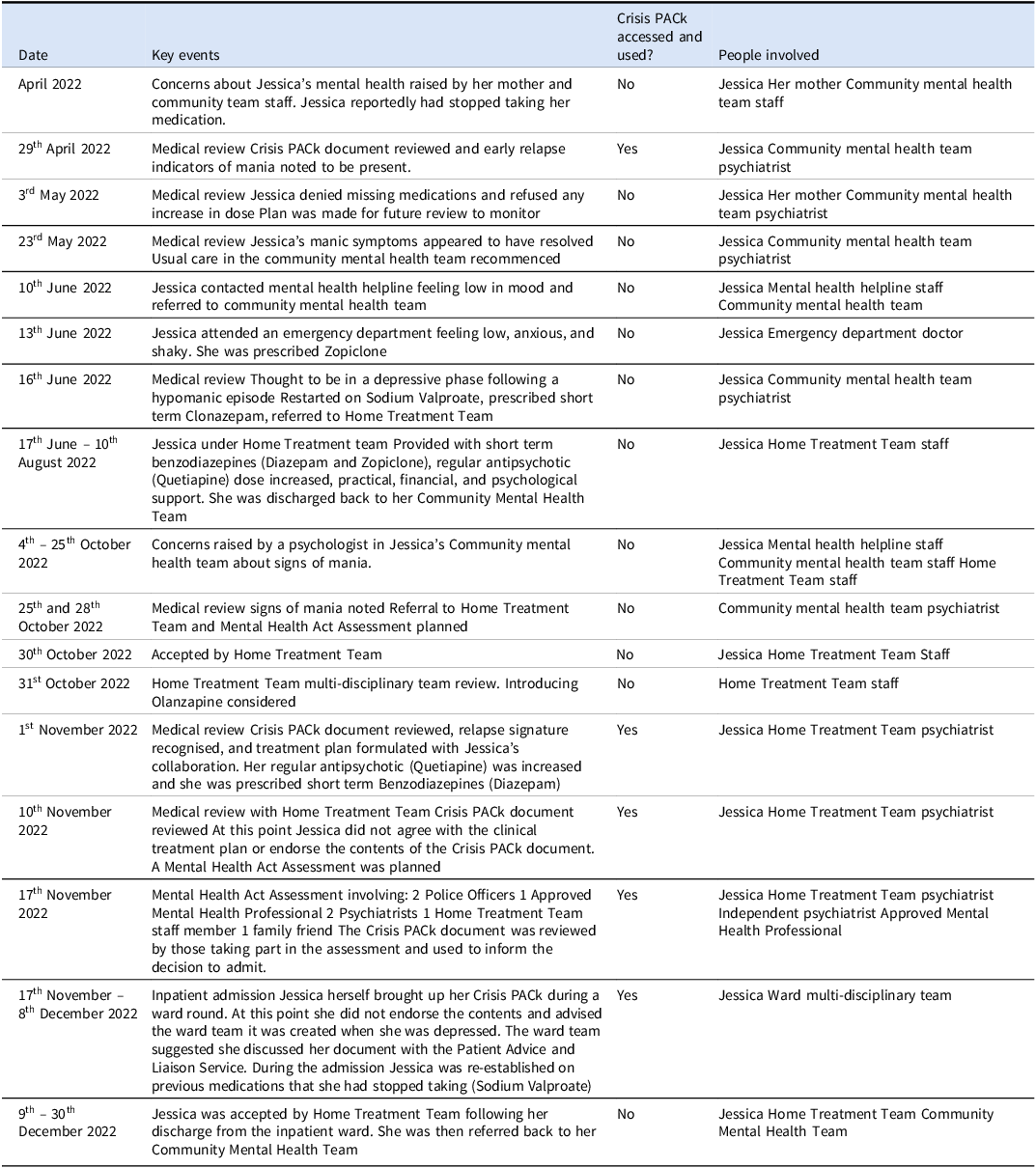

The events of this follow-up period are summarised in the table below:

Views on SBD when unwell

During the follow-up period when Jessica was in crisis there was clear documentation of fluctuation in her views on her document. When she was starting to display signs of relapse she initially endorsed her documents contents and was willing to formulate a collaborative plan with health professionals. However, as her symptoms escalated, she rejected the contents, and cast doubt on its validity asserting that it had been made during a time when she was depressed. She asserted that these prior wishes should be disregarded and her present wishes should be given authority.

Retrospective views on self-binding directives

In October 2023 (almost a year after detention under the Mental Health Act), Jessica was interviewed about her experiences. At this point, her mental state had recovered. Jessica’s shifting perspectives on the document during the crisis period were discussed and she was clear that she endorsed the original preferences she expressed when she was well, prior to her crisis. She felt that when she was unwell, she was in an ‘altered mental state’ and could argue against things previously agreed when well. She said ‘its like another personality takes over when I am unwell and in the throes of mania, I do things I would never normally do’. Her retrospective view was consistent with her prospective view: she was clear she wished professionals to follow the preferences she made when well and, if necessary, override those expressed when unwell. She felt pleased that at least some professionals looked at her document when she was in crisis and took it seriously.

She wished to make some changes to her document. She was satisfied with the SBD component of the document but wished to update her crisis contacts in the context of a bereavement and give more detail around her preferences for the process of a Mental Health Act assessment. Jessica reported finding the process of the Mental Health Act Assessment frightening. This was partly down to the large number of people it entailed coming into her home. She wished to emphasise the impact of having police attend Mental Health Act assessments on herself and her children and requested that the police were called only if necessary rather than automatically. She included a summary of how her mental health and in turn her ‘cognitive ability’ and her ‘judgement’ had been impacted over the past months both during times of depression and mania. She endorsed the treatment she had received under Home Treatment Team and the medication choices of Quetiapine and Benzodiazepines.

Retrospective feedback from one of the psychiatrists involved in managing Jessica’s care was also obtained. This psychiatrist was part of the Home Treatment Team and used Jessica’s document in medical reviews and during the Mental Health Act Assessment. Feedback from the psychiatrist involved was: ‘I thought [the ADM document] was really well laid out with extremely helpful information, particularly the direct quotes from Jessica herself and it really informed the way I and the team tried to work with her… she mentioned some preferences that we tried to keep sight of…the potential impact on her children which helped us work with friends and family to make a decision around the necessity of admission…at the time (she was unwell) she ….suggested that she’d never been on board with it.. She was just a bit too unwell…to engage fully with the plan’.

Discussion

Summary of key findings

This is, to our knowledge, the first case report of the experience of using a mental health SBD. It confirms SBDs can enhance the longitudinal experience of service user autonomy when applied during mental health crises. There were clearly documented changes in the service user’s decision-making capacity and endorsement of the SBD during the crisis period. Despite these changes the service user’s preferences remained consistent across time when in a well state. Implementation of SBDs within complex health systems was imperfect but possible. Despite these imperfections using a document that included self-binding was still seen as a good enough, positive intervention that the service user wished to keep as part of their care.

Comparison of findings with existing reasons for and against self-binding directives

This case report sheds light on five of the key areas in the debate on SBDs as identified in a systematic review of the existing literature (Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Gieselmann, Gergel, Owen, Gather and Scholten2023): whether SBD enhances or diminishes service user autonomy, implementation difficulties, difficulties assessing mental capacity, personal identity, and the potential to cause harm. These are discussed in more detail below.

The case report exemplifies an experience where using an SBD, overall, enhances service user autonomy. This occurs on three fronts. Firstly in terms of Jessica’s internal experience of personal autonomy through time. Secondly, Jessica’s agency interacting with others within a healthcare system. Thirdly, from an external perspective, the process through which coercion is justified. We consider each in turn.

Jessica wished to prioritise her longitudinal sense of personal autonomy over the risk of losing negative liberty at one particular point in time (when unwell). Jessica’s well self was able to assert autonomy over her unwell self to try and avoid harm to herself, her loved ones, and her relationships with them. Based on her experience of prior episodes, she was aware of the likelihood of conflict between these two ‘selves’ and she wished to choose. She was aware that she would be likely to refuse treatment that would reduce manic symptoms when unwell. This seems to be a relatively common position for service users living with Bipolar (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Gaillard, Vollmann, Gather and Scholten2023, Hindley et al. Reference Hindley, Stephenson, Keene, Rifkin, Gergel and Owen2019).

Jessica also experienced the process of creating a document as an empowering intervention within a mental health system. This concords with the experience of other service users making more general advance decision-making documents. (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Gaillard, Vollmann, Gather and Scholten2023) The process of creating the document afforded her access to an expensive and scarce resource – a Consultant Psychiatrist. The process of applying the document allowed her well self to ‘speak’ through time to an unfamiliar clinician who had only met her when unwell. The feedback from the Home Treatment Team Psychiatrist who assessed her in crisis suggested it was easier to take the views of her well self into account and apply this wisdom to management of her unwell self. Of course, it could be argued that her ability to exert her personal autonomy was limited by clinician awareness, willingness, and ability to access and apply the document in crisis and, as the timeline suggests, it was accessed in only a minority of crisis interactions.

From an external perspective, this case report exemplifies a prospective request for treatment and then retrospective approval. This pattern of endorsement seems to be evidence of the ‘thank you’ theory of involuntary treatment in action. This theory holds that coercion can be justified if there is a need for treatment, a loss and then regain of capacity during an episode of illness plus the service user approves of the use of coercion in retrospect (Stone and Stromberg, Reference Stone and Stromberg1975). There is other research exploring retrospective service user views of coercion. The data is complex, with some evidence suggesting retrospective endorsement may vary across international clinical settings, socio-economic circumstances, and functioning (Priebe et al. Reference Priebe, Katsakou, Amos, Leese, Morriss, Rose, Wykes and Yeeles2009). But it is at least possible to say retrospective endorsement of coercion is not uncommon and in some cases is the majority experience over time (Priebe et al. Reference Priebe, Katsakou, Glöckner, Dembinskas, Fiorillo, Karastergiou, Kiejna, Kjellin, Nawka, Onchev, Raboch, Schuetzwohl, Solomon, Torres-González, Wang and Kallert2010) and on regaining capacity (Owen et al. Reference Owen, David, Hayward, Richardson, Szmukler and Hotopf2009). However, this ‘thank you’ theory has lacked a prospective limb. This case report links a prospective request to self-bind to involuntary treatment (with the assistance of mental health services and law) with a retrospective endorsement of the involuntary treatment received. Therefore, it adds evidence that loss of negative liberty in applying SBDs and involuntary treatment may be justified from the point of view of autonomy-based ethics.

Existing literature on advance decision-making in general (Shields et al. Reference Shields, Pathare, van der Ham and Bunders2014) and SBDs in particular commonly cites implementation as a potentially insurmountable challenge (15, 17). This case report suggests that SBDs are clinically feasible, but that more work needs to be done to embed them in practice. Particular challenges in this case were around clinician awareness and access to the document.

In her journey to compulsory admission, Jessica had crisis contacts with at least 13 health professionals from her Community Mental Health Team, Crisis Phone Line, Home Treatment Team, Emergency Department, Mental Health Act Assessment team, and Ward Team.

Only two of these professionals referenced using the service user’s document to formulate treatment plans. These were the two psychiatrists who had been part of a team where there was a Consultant Psychiatrist and Junior Psychiatrist involved in the Crisis PACk project team.

The document was referenced in the recording of only two clinical meetings: the MHA assessment, where one of the aforementioned psychiatrists was involved and a routine ward round where Jessica herself mentioned the document.

This finding is consistent with empirical research on general advance decision-making, which suggests that a key barrier to implementation is clinician engagement (Thornicroft et al. Reference Thornicroft, Farrelly, Szmukler, Birchwood, Waheed, Flach, Barrett, Byford, Henderson, Sutherby, Lester, Rose, Dunn, Leese and Marshall2013). It must be acknowledged that making a document such as the one described in this case study requires an additional ‘up front’ investment of time and resource. The document was made as part of a pilot study where the average clinical time required was 38 minutes with a facilitator to draft the document and 78 minutes for a meeting with a treating clinician to complete the document (Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Gergel, Ruck Keene, Rifkin and Owen2022). However, in line with previous research on ADM documents, the clinicians who were aware of the document, and engaged with it in crisis reported finding it helpful rather than problematic (Gaillard et al. Reference Gaillard, Braun, Vollmann, Gather and Scholten2023). Economic analyses suggest that ADM documents are a cost-effective intervention, a factor which could also be motivating for clinicians, and health organisations (Loubière et al. Reference Loubière, Loundou, Auquier and Tinland2023). Case reports like this can thus help to bring to life what implementation science is finding – namely that important and feasible targets for quality improvement are: education and training for clinicians and clear strategies for embedding in clinical pathways during crisis contacts and key decision-making junctures (Lasalvia et al. Reference Lasalvia, Patuzzo, Braun and Henderson2023). At present, one known research project in South East London is exploring how ADM documents could be implemented and embedded in routine clinical practice at scale. This includes considering implementation strategies that will make most efficient use of senior clinicians’ time and protect the quality of a thoughtful and personalised ADM making process. Current strategies include employing and training specialist facilitators, engaging clinical champions, creating manuals, and embedding within digital tools (Henderson, Reference Henderson2024).

The assessment of mental capacity was a point of tension well illustrated in this case study. Jessica, when unwell with mania, questioned the legitimacy of the document for plausible reasons. She said that the document had been written when she was depressed. There was an element of truth in this as the drafting process had been paused when it became clear she was experiencing a depressive episode. This could have called the ‘existence’ of the document into question within the meaning of the MCA, as there may have been doubt about whether she had the capacity to make it at the time of drafting. This was a potentially challenging moment for clinicians who needed to be able to tolerate a dilemma akin to Ulysses commanding his crew to untie him while under the influence of the song of the sirens. However, the clinicians did not seem to find this tension too taxing, which may have been due to the detailed and clearly structured information in the document. Firstly, in the document was a statement in Jessica’s own words commenting on her mental health at the time. Here she acknowledged that she had been depressed but provided an update on how this mental state had improved. Secondly, the document contained a personalised mental capacity assessment where she described in her own words how health professionals might know she had lost capacity; this centred around the presence of mania. Thirdly, the document contained a clear description of personalised relapse indicators including changes in speech, thoughts, and behaviour, which indicated the presence of mania. Fourthly, the document contained a capacity assessment completed by a consultant psychiatrist at the time the document was written. This case study suggests that in this context, the issue of mental capacity assessment may be considered as a clinical quality and implementation issue rather than something which is conceptually insurmountable.

The systematic review of reasons for and against SBD clarified some key concerns around personal identity. Authors discussed that identifying an authentic self with authentic preferences is complex and assuming that the self at one point in time should have primacy over the self at another point in time is unjustified (Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Gieselmann, Gergel, Owen, Gather and Scholten2023; Kane, Reference Kane2017). Other empirical work exploring service user views on SBD suggests that for some, this is an important consideration and that there is a group who values and identifies with the experience of mania and considers it to be an important part of who they are (Gergel et al. Reference Gergel, Das, Owen, Stephenson, Rifkin, Hindley, Dawson and Ruck Keene2021). However, Jessica seemed to be one of the majority for whom it was very clear that her well self was her authentic self and should be given primacy. She had several analogies for the experience of mania, describing it as a different or altered personality, an altered mental state, akin to taking drugs or as having lost control. Also of note is the tone of control she wishes to exert over her future self. Interestingly, in contrast to the authoritarian ‘grievous bonds’ that Ulysses describes (Gergel and Owen, Reference Gergel and Owen2015), Jessica’s ideal is to be a maternal, caring figure who sets protective boundaries for herself. This view of SBD is consistent with work done by artist Beth Hopkins in partnership with other service users exploring binding as protective and creative (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2022).

Key reasons other authors have given to suggest SBDs may be harmful include: removing the benefits of mania, stigma of having an SBD, and disappointment to service users if SBDs are not accessed or followed in crisis. Jessica is clear that, for her well self, mania is not a beneficial state, and she wishes to have treatment even if this requires difficult admission to a psychiatric hospital. She acknowledges difficulty in facing the reality of having a serious mental illness but, for her, this does not negate the potential benefits of advance decision-making. She does not mention stigma from others as a serious consideration. However, the concern around disappointment if the SBD is not accessed in a crisis is a serious one, given the evidence from this case study around how poorly embedded mental health advance decision-making seems to be in current mental health services. Jessica, however, is pleased that her document was used by at least some clinicians and she takes a realistic view about the limitations of services. It seems important that this concern is understood as a spur for action towards better implementation rather than a reason not to attempt it.

Conclusion

This is the first case report of a service user’s experience of using a SBD. Importantly, it presents changing perspectives through time, describing a service user’s views both prospectively and retrospectively. It provides counterarguments to critics of SBDs who argue they may be unethical because of the impact on negative liberty, difficulties with implementation, assessing capacity, personal identity, and the potential to cause harm. The service user in this case report endorses SBDs and, in her case, it was possible to implement it within mental health services. However, it is notable that a document so valuable to autonomy-based psychiatric ethics was accessed by only a minority of healthcare professionals during her mental health crisis. This case is the latest in mounting empirical research, creating a wake-up call for policymakers involved in introducing provisions for mental health advance decision-making. SBD cannot be ignored – it is likely to be wanted by service users. To meet this demand, a conscious focus on implementation strategies to embed SBD into clinical crisis pathways is required.

Table 2. Summary of crisis events

Funding statement

MS reports funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (SALUS; grant number 01GP1792). LS and GO report funding from Wellcome; grant number 203376.

Competing interests

No competing interests.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for the Crisis PACk qualitative research interview study was granted by Camberwell and St Giles ethics committee (REC reference 19/LO/1142.). Initial approval was granted on 03.09.2019 with an amendment approved on 04.08.2020 to allow the research to continue under pandemic restrictions. Governance and approval for the Crisis PACk Quality Improvement Project was provided by the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Quality Improvement team. Direct quotes taken from the qualitative research interviews are used to illustrate key points in this case report. We also use understanding gained from field notes and informal communications with study participants, e.g. follow-up emails with professionals involved in Jessica’s crisis management. We do not quote directly from any confidential medical records. ‘Jessica’ was fully aware and involved in the creation of this article. She was asked for consent in advance of producing the first draft, consulted on further drafts and approved the final draft. She has given informed consent to publish in accordance with the journal’s procedures.