Impact statement

This study provides the first comparative empirical evidence on how grazing by guanacos – Patagonia’s native large herbivore – and domestic sheep affects plant regeneration in Patagonian shrub-steppes. Understanding these differences matters for both ecological conservation and livestock production in one of the most extensive dryland regions of South America. We show that both herbivores influence early plant regeneration through seedling emergence, although the magnitude of this response depends on site conditions and grazing history. In contrast, vegetative regeneration of perennial grasses responded positively only to short-term exclusion of guanacos, while sheep exclusion had no detectable effect. Because vegetative regrowth is a key mechanism supporting grassland persistence and forage continuity, this distinction has tangible implications for sustainable grazing management. Our findings underscore the importance of explicitly incorporating native herbivore densities when estimating grazing capacity. Recognizing the ecological role of the guanaco – an herbivore that co-evolved with Patagonian ecosystems – helps avoid overestimating forage availability and supports the design of grazing systems that maintain biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and long-term productivity. The evidence provided here contributes directly to refining grazing management models and informing public policies aimed at socio-ecological sustainability in arid regions. We also highlight that real-life grazing scenarios may involve more complex interactions than those reproduced in controlled experiments. For example, competitive exclusion in ranching systems or unusually high guanaco densities in protected areas can modify grazing pressures. Because guanacos and other wild herbivores can move across fences, areas assumed to be protected from domestic grazing may still experience non-negligible herbivory. For this reason, range-management programs should include reliable estimates of guanaco density to adjust sheep stocking rates and to better manage both sexual and asexual plant regeneration. Overall, this work provides essential scientific evidence to support adaptive grazing strategies that integrate native and domestic herbivores, contributing to the sustainable management of Patagonian drylands under variable environmental conditions.

Introduction

Rangelands constitute the most important forage source for sheep production and wild grazers in the Patagonian steppe. Historical high and continuous stocking rates have degraded vegetation and soils (Bertiller et al., Reference Bertiller, Ares and Bisigato2002), a process given, as in other rangelands worldwide, under poorly understood interactions with wild native herbivores (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Porensky, Riginos, Veblen and Young2017). In many areas, sheep (Ovis aries) share forage resources with guanaco (Lama guanicoe), an emblematic native wild large ungulate (85 kg), and with other minor wild species (choique, mara and European hare; Baldi et al., Reference Baldi, Pelliza-Sbriller, Elston and Albon2004). Even though guanaco abundance has been low, recent evidence indicates that, together with sheep, they currently may exceed by 60% the steppe carrying capacity (Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, Paredes, Ferrante, Cepeda and Rabinovich2019; but see Marino et al., Reference Marino, Rodríguez and Schroeder2020). Hence, sheep and guanaco coexistence has triggered conflicts among conservation advocates and ranchers. While environmental organizations claim for the conservation of guanaco and highlight the morphological and behavioral features that would make it less detrimental than sheep (Puig et al., Reference Puig, Videla, Cona and Monge2001), ranchers perceive guanaco as a sheep competitor (Baldi et al., Reference Baldi, Pelliza-Sbriller, Elston and Albon2004; Nabte et al., Reference Nabte, Marino, Rodriguez, Monjeau and Saba2013; Hernández et al., Reference Hernández, Corcoran, Graells, Roos and Downey2017).

The Patagonian steppe is dominated by a mosaic of shrubs and perennial grasses, the most important forage resources, together with annual herbaceous species thriving during short and favorable periods (Bertiller and Bisigato, Reference Bertiller and Bisigato1998). Shrubs and perennial grasses are interspersed in a matrix of bare soil, which is covered by annual species (Aguiar and Sala, Reference Aguiar and Sala1998; Bertiller and Bisigato, Reference Bertiller and Bisigato1998). Primary productivity is limited by low temperature during winter and by water shortage during spring and summer (Jobbágy et al., Reference Jobbágy, Sala and Paruelo2002). Perennial grasses concentrate their growth in autumn–winter but sustain year-round photosynthetic activity. Shrubs vary in their phenology, although their growth is concentrated in spring and summer (Golluscio et al., Reference Golluscio, Oesterheld and Aguiar2005). The dominant plant reproduction is by seeds, although grasses also reproduce through tillering (Gaitan et al., Reference Gaitan, López and Bran2009).

Micro-site conditions for plant regeneration vary between vegetated patches and bare soil (Bisigato and Bertiller, Reference Bisigato and Bertiller2004). The spatial distribution of seed and water availability are critical control of plant emergence and recruitment of seedlings and of the vegetative growth of perennial species (Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, Noy-Meir and Cibils2001; Bisigato and Bertiller, Reference Bisigato and Bertiller2004; Schwinning and Sala, Reference Schwinning and Sala2004). Seedling recruitment is more probable around vegetated patches than in bare soil, depending on the net balance of competition and facilitation interactions between adult plants and seedlings (Aguiar and Sala, Reference Aguiar and Sala1997; Aguiar and Sala, Reference Aguiar and Sala1999). Despite competition for resources being lower in bare soil, other stressors such as drought, wind, grazing and trampling are more severe in bare soil than near vegetated patches (Aguiar and Sala, Reference Aguiar and Sala1999; Bisigato and Bertiller, Reference Bisigato and Bertiller2004; Chartier and Rostagno, Reference Chartier and Rostagno2006; Bertiller et al., Reference Bertiller, Marone, Baldi and Ares2009; Leder et al., Reference Leder, Peter and Funk2015).

Sheep have impaired a long-term and extended grassland degradation process, given by the combination of recurrent grazing on certain species and individuals (selectivity) and by trampling (Bertiller and Ares, Reference Bertiller and Ares2011; Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, Paredes, Ferrante, Cepeda and Rabinovich2019). Sheep’s small body size (45 kg) contributes to their ability to select the most nutritious species or plant tissues, affecting their seed production, tillering of grasses and individual growth, under the most extended year-round grazing management (Bertiller et al., Reference Bertiller, Ares and Bisigato2002, Reference Bertiller, Marone, Baldi and Ares2009). Sheep jeopardize the regeneration of perennial grasses (Oñatibia and Aguiar, Reference Oñatibia and Aguiar2019) and reduce the soil seed bank and seedling emergence and establishment (Bertiller et al., Reference Bertiller, Marone, Baldi and Ares2009). Nevertheless, recent evidence indicates that moderate grazing intensity and grazing-rest management may enhance forage availability (Oñatibia and Aguiar, Reference Oñatibia and Aguiar2019; Buono, Reference Buono2020). Sheep grazing also modifies the structure of vegetation, increasing the number and size of bare soil interpatches and subdividing vegetated patches (Cepeda et al., Reference Cepeda, Oliva and Ferrante2024).

Guanaco is considered the most influential wild herbivore in Patagonia. Nevertheless, the empirical evidence on its impact on plant growth and regeneration is virtually nonexistent (Nabte et al., Reference Nabte, Marino, Rodriguez, Monjeau and Saba2013). Guanaco and sheep have a largely overlapping diet (Puig et al., Reference Puig, Videla and Cona1997, Reference Puig, Videla, Cona and Monge2001; Baldi et al., Reference Baldi, Pelliza-Sbriller, Elston and Albon2004), although guanaco would display a dietary flexibility as it can incorporate several shrub species (Baldi et al., Reference Baldi, Pelliza-Sbriller, Elston and Albon2004). Different from sheep, which are confined to a given and human-intervened area, guanaco is displaced by sheep toward marginal habitats (Marino et al., Reference Marino, Rodríguez and Schroeder2020) and moves away from sheep flocks and through the landscape by jumping fences (Puig et al., Reference Puig, Videla, Cona and Monge2001). This spatial mobility, together with a broader diet (Puig et al., Reference Puig, Videla and Cona1997) and its less destructive hoof structure contribute to the generalized notion that its impact on the steppe is less detrimental than that of sheep (Flores et al., Reference Flores, Cingolani, von Müller and Barri2012). However, there is no empirical evidence on their impacts in a comparative study (Puig et al., Reference Puig, Videla, Cona and Monge2001). Given that the impact of grazing depends not only on the type of herbivore but also on the density of animals in relation to the productivity of the rangelands, this experiment included conditions with different densities of guanacos and carrying capacity of the rangelands. Based on observational and manipulative studies, we evaluated the effects of sheep and guanaco on plant community regeneration through seed production and through tiller production in two sites of Patagonian shrub-steppe. We first evaluated the pre- and post- dispersal soil seed bank in areas grazed either by sheep or guanaco; second, we evaluated the short-term effect of grazing exclusion on seedling emergence and perennial grasses tillering. Based on the evidence presented above, we hypothesized that grassland regeneration from seeds and from tillers would be more impaired by sheep than by guanaco, particularly for grasses, the most valuable forage for sheep production.

Methods

Study system and design

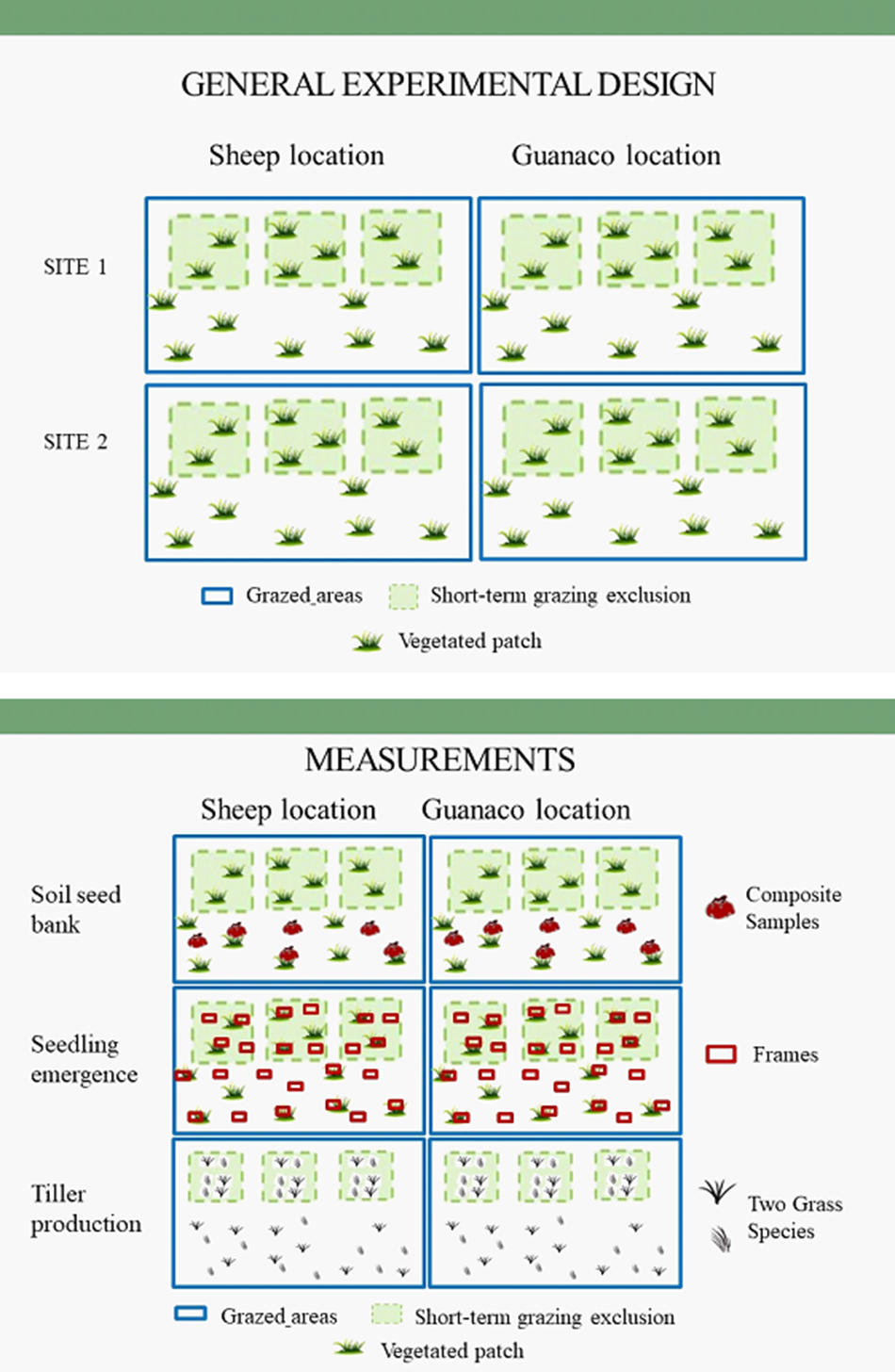

We conducted two complementary field studies at two sites in the Patagonian shrub-steppe to investigate the effects of guanaco and sheep on plant regeneration. The first study evaluated the soil seed bank in areas grazed either by guanaco or sheep. The second study evaluated seedling emergence of the whole plant community and tiller production of the two most important grass species of each site, and the effects of short-term grazing exclusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1. General scheme of the experimental design (upper panel) and of the measurements (lower panel). The blue squares represent the locations corresponding to each herbivore (grazed), and the inner green squares represent the short-term exclosures. The grasses represent the vegetated patches, and the remaining area represents the bare soil. In the lower panel, the bags represent soil samples for the seed bank (at both vegetated patches and bare soil), the red squares represent the grids for the emergency count, and the illustrations of different grasses denote the different grass species studied. Note that, because of the absence of differences between vegetated patches and bare soil, the analysis of emergence was made by pooling both microsites.

The shrub-steppe is composed of vegetated patches dominated by perennial tussocks and large shrubs in a matrix of bare soil (Oyarzabal et al., Reference Oyarzabal, Clavijo, Oakley, Biganzoli and Tognetti2018). Sites were located in two of the most representative vegetation units: Site 1 is in the Península Valdés ecotone, and Site 2 is included in the Monte vegetation unit (León et al., Reference León, Bran, Collantes, Paruelo and Soriano1998; Pazos et al., Reference Pazos, Bisigato and Bertiller2007; Oyarzabal et al., Reference Oyarzabal, Clavijo, Oakley, Biganzoli and Tognetti2018). Each site consisted of two paired locations grazed year-round, one exclusively by guanaco (reserve) and the other by sheep (ranch). The two sites were located 150 km apart, and guanaco and sheep locations within each site were separated by 5 km. Although guanaco can graze simultaneously with sheep and move freely across paddocks, sheep locations were free of guanaco presence (tracks or feces). During field visits, we visually confirmed the absence of guanaco either inside or around the sampling areas, supporting effective spatial segregation between herbivore types at the local scale.

Regarding the presence and behavior of guanacos within the paddocks, it is important to highlight that although guanacos can move freely between different areas of the site, their distribution within the paddocks is not homogeneous (Senft et al., Reference Senft, Coughenour, Bailey, Rittenhouse, Sala and Swift1987; Coughenour, Reference Coughenour1991; Teague et al., Reference Teague, Dowhower and Waggoner2004). Guanacos tend to concentrate in areas with higher resource availability, such as zones with denser vegetation or those with higher cover of perennial grasses and large shrubs. However, their area selection is also influenced by factors like water availability, forage quality and natural shading provided by large shrubs (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Gross, Laca, Rittenhouse, Coughenour, Swift and Sims1996).

In the paddocks of the studied sites, guanacos do not exhibit a completely random distribution. Instead, they show a strong preference for areas that allow access to a greater variety of vegetation, which may influence plant regeneration in the more heavily grazed zones. During field surveys, it was observed that guanacos tend to avoid areas near fences and roads, which could be related to safety concerns or ease of access to other areas with richer resources.

Furthermore, as guanacos are naturally nomadic, their grazing behavior is dynamic and changes over time depending on seasonality and forage availability (Schroeder et al., Reference Schroeder, Rodríguez, Marino, Panebianco and Peña2022). Grazing patterns in the paddocks may also be influenced by climatic conditions, especially rainfall distribution, which affects forage availability. This may explain the differences in grazing pressure observed between the two study years, with the first year having above-average precipitation and the second year being below average, which could have influenced guanaco behavior and their spatial distribution.

On the other hand, in areas of the paddocks where guanacos were present, no signs of significant overgrazing were observed near the exclosure areas, suggesting that while guanaco grazing is important, it was not leading to excessive vegetation degradation. In these sectors, plant regeneration appeared to be in an intermediate state, with a vegetative response that could indicate moderate grazing pressure, which may ultimately contribute to the diversity and resilience of the shrub-steppe ecosystem.

Guanaco areas showed no signs of sheep presence. Each location was delimited inside paddocks of at least 2,000 ha. Within each paddock, we identified homogeneous areas of ~1,500 m2 by analyzing satellite images (Landsat 8 OLI, 30 × 30 m resolution, bands 2–6), which were then ground-validated. Selected areas were located in homogeneous sectors of vegetation and topography, avoiding proximity to fences, roads, water points and ranch buildings (at least 500 m away) to minimize edge effects and represent average grazing conditions within each paddock. In February 2015, we built three exclosures (each 6 × 6 m, 1.6 m height) in each area, which excluded all large and medium herbivores, as well as small herbivores. Although total exclusion of herbivores is not a possible nor desirable scenario, we also excluded small herbivores to estimate the potential steppe regeneration capacity in the absence of vertebrate herbivores. During fieldwork, no signs (feces or burrows) of small herbivores were observed within the plots.

Plant cover of the grazed areas was analyzed by the Canfield method, on three transects of 30 m long, in coincidence with the position of each exclosure, beginning at 10 m from each exclosure to avoid the sectors more transited during the study (Figure 1). Measurements were recorded in spring (2014 and 2015) and autumn (2015). Aerial cover was grouped into shrubs, perennial herbaceous (mostly grasses) and annuals (forbs and graminoids). Total plant cover ranged from 63% in spring 2014 to 46% in spring 2015, following the precipitation pattern (see below).

Site 1 pair consisted of the “San Pablo de Valdés” reserve (42° 41′45.1′′ S and 64° 9′53.53′′ W), built in 2005, and the neighboring ranch “Bajo Bartolo” (42° 41′53.4′′ S and 64° 9′34.32′′ W), in Península Valdés. The reserve extension was 7,360 ha, and the ranch was 8,417 ha. Site 2 pair corresponded to “Viento Norte” reserve (43° 0′ 27.4′′ S and 65° 33′ 41.18′′ W), without sheep since 2012, and its neighboring area belonging to “Las Piedritas” ranch (43° 0′ 26.71′′ S and 65° 33′ 48.28′′ W). The reserve had 13,703 ha, and the ranch had 14,368 ha. The average temperature of both study sites was similar, ranging from 8 °C in winter and 20 °C in summer. The mean annual precipitation for the last 3 years (2013–2015) was 292 and 160 mm/yr for sites 1 and 2, respectively. Nevertheless, the 2 years studied exhibited a large variation as the first year was above the average and the second year below the average. Precipitation in site 1 was 346 mm in 2014 and 194 mm in 2015; in site 2, it was 208 and 98 mm in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Site 1 had a greater total cover than site 2 (Figure S1, Supplementary Material); in turn, site 1 had a greater shrub and a lower annual cover in the guanaco location than in the sheep location. Conversely, site 2 had a greater cover of annuals in the guanaco location than in the sheep location in autumn.

To discard potential confounding effects between herbivore type and stocking rate, we analyzed the carrying capacity of both sites and their corresponding stocking rates of each guanaco and sheep. Site 1 doubled the carrying capacity of site 2. In turn, in site 1, for both herbivores, stocking rate doubled carrying capacity, whereas in site 2, stocking rate of both herbivores was approximately half of carrying capacity (Table S1, Supplementary Material). It is important to note that the comparable stocking rates of sheep and guanacos observed between sites were not the result of deliberate site selection. Instead, they arose incidentally from the natural grazing patterns and local densities of the two herbivores, representing the prevailing conditions in each system at the time of sampling.

Estimates of carrying capacity and stocking rates were derived from the combination of regional forage availability and species-specific animal requirements. Forage availability was estimated based on published values of aboveground primary productivity and pastoral value for Patagonian shrub-steppe communities (Beeskow et al., Reference Beeskow, del Valle, Rostagno and Coronato1987; Nakamatsu et al., Reference Nakamatsu, Elissalde, Buono, Escobar, Behr and Villa2013), rather than direct biomass clipping or remote sensing. These estimates were combined with standard energetic requirements for sheep (Elissalde et al., Reference Elissalde, Escobar and Nakamatsu2010) and guanacos (Marino and Rodríguez, Reference Marino and Rodríguez2017) to derive carrying capacity values expressed in equivalent units (EU). In this study, one EU corresponds to one adult sheep equivalent, and guanaco forage demand was converted into sheep-EUs following Marino and Rodríguez (Reference Marino and Rodríguez2017). Assumptions and conversion factors used to derive EU are detailed in Table S1 (Supplementary Material).

Sheep stocking rates were obtained from the annual survey conducted by the provincial bureau of statistics (Dirección General de Estadística y Censos de Chubut, 2015) and corroborated by ranch owners. Guanaco stocking rates were estimated in situ using distance sampling (Marino and Rodríguez, Reference Marino and Rodríguez2017). Fixed transects were established from a vehicle traveling at low speed (20–30 km h−1), and for each detected group of guanacos, group size and perpendicular distance to the transect line were recorded. Density estimates and their 95% confidence intervals were obtained using DISTANCE 7.3 software and are reported in Table S1.

The similarity in stocking rates (expressed in EU) between sheep- and guanaco-grazed areas within each site was not imposed a priori but reflects the observed densities during the study period. Nevertheless, stocking rates were estimated at the paddock level and may differ from actual grazing pressure at the sampled plots due to the heterogeneous and selective grazing behavior of large herbivores in Patagonian rangelands (Teague and Dowhower, Reference Teague and Dowhower2003; Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Marino and Schroeder2024).

Studied variables and data analysis

In the first study, we evaluated the pre- and post-dispersal soil seed bank in the locations grazed by guanaco and sheep, and under vegetated patches and bare soil, whose density largely differs in these rangelands (Bisigato et al., Reference Bisigato, Villagra, Ares and Rossi2009). Vegetated patches and bare soil were analyzed independently and were not compared within the same statistical models. In each, we obtained three composite samples randomly selected near vegetated patches and three in the bare soil between patches. Each composite sample represented the statistical unit of analysis and was composed of three subsamples, collected with a core of 16 cm in diameter and 2 cm deep (Figure 1).

Sampling was conducted before (early spring) and immediately after (late summer-early autumn) seed dispersal (hereafter named pre- and post-dispersal); pre-dispersal was evaluated in September 2014 and 2015, and post-dispersal was evaluated in March 2015 and 2016. Soil was sieved (2 mm mesh), distributed in containers and incubated in a growth chamber for 3 months at field capacity, with 12-h light/darkness and fluctuating temperatures (25 °C/15 °C), following Morici et al. (Reference Morici, Kin, Mazzola, Ernst and Poey2006). Seedling emergence was recorded weekly for 3 months until emergence ceased. Seedlings were classified into the three functional groups mentioned above, and their density was expressed as seeds per square meter.

For comparisons between herbivores, we applied independent generalized linear models (GLMs) with a Poisson error distribution, or quasi-Poisson when overdispersion was detected using the Pearson test. Subsequently, the variance explained by the model, including the herbivore type (sheep or guanaco), was compared to the model without this factor using deviance analysis. Accordingly, for each site, we tested pre- and post-dispersal soil seed banks independently for vegetated patches and bare soil. For a given sampling moment (pre- or post-dispersal), data from the two evaluated years were pooled as values did not differ significantly between years.

In the second study, we evaluated the role of short-term exclusion on seedling emergence at the plant community-level and tiller production of the two most important grass species of each site. Records were obtained roughly every 3 months (autumn, winter, spring and summer), from April 2015 through January 2016. Seedling emergence was evaluated by sampling permanent 50 × 20 cm frames, subdivided into 5 × 5 cm quadrats. Both inside and outside each of the three exclosures, we sampled near vegetated patch and in the bare soil. As seedling emergence was similar in vegetated patches and bare soil, the data were combined for the analysis. On each sampling date, only seedlings with fewer than four leaves were recorded to avoid double-counting. Seedlings were not classified by functional groups, although most of them were annual grasses and forbs. The exclosure was considered the primary experimental unit, and frames and quadrats were treated as subsamples providing repeated observations within each exclosure and its paired grazed area. The seedling emergence of each site and herbivore type was analyzed using GLMs with a Poisson error distribution, or quasi-Poisson when overdispersion was detected using the Pearson test. Subsequently, the variance explained by the model including the grazing condition (grazing or exclusion) was compared to the model without this factor by a deviance analysis.

Tiller production was evaluated by selecting nine individuals inside and outside the exclosures. The species were Nassella tenuis and Piptochaetium napostaense (site 1) and Pappostipa speciosa and Poa lanuginosa (site 2) (Figure S2, Supplementary Material). Individuals of each species were similar in size. A quarter of each individual tussock was identified with a buried wire ring. We counted the number of new tillers produced inside the ring every 3 months, from autumn 2015 through summer 2016 (Figures S3 and S4, Supplementary Material).

Individual plants were treated as subsamples within each exclosure and paired grazed area. Tiller production of each species was compared between grazing conditions (grazing or exclusion) by GLMs with a Poisson error distribution, or quasi-Poisson when overdispersion was detected using the Pearson test. Subsequently, the variance explained by the model, including the grazing condition (grazing or exclusion), was compared to the model without this factor by a deviance analysis. For simplicity, the values presented correspond to the total tiller count obtained on the last measurement date (summer 2016).

Given the limited number of exclosures per treatment (n = 3), exclosure identity was not included as a random factor in mixed-effects models, and results are interpreted acknowledging this limitation.

Statistical analyses were performed with R software (version 4.3.0, R Core Team, 2023), with a significance level of 0.05.

Results

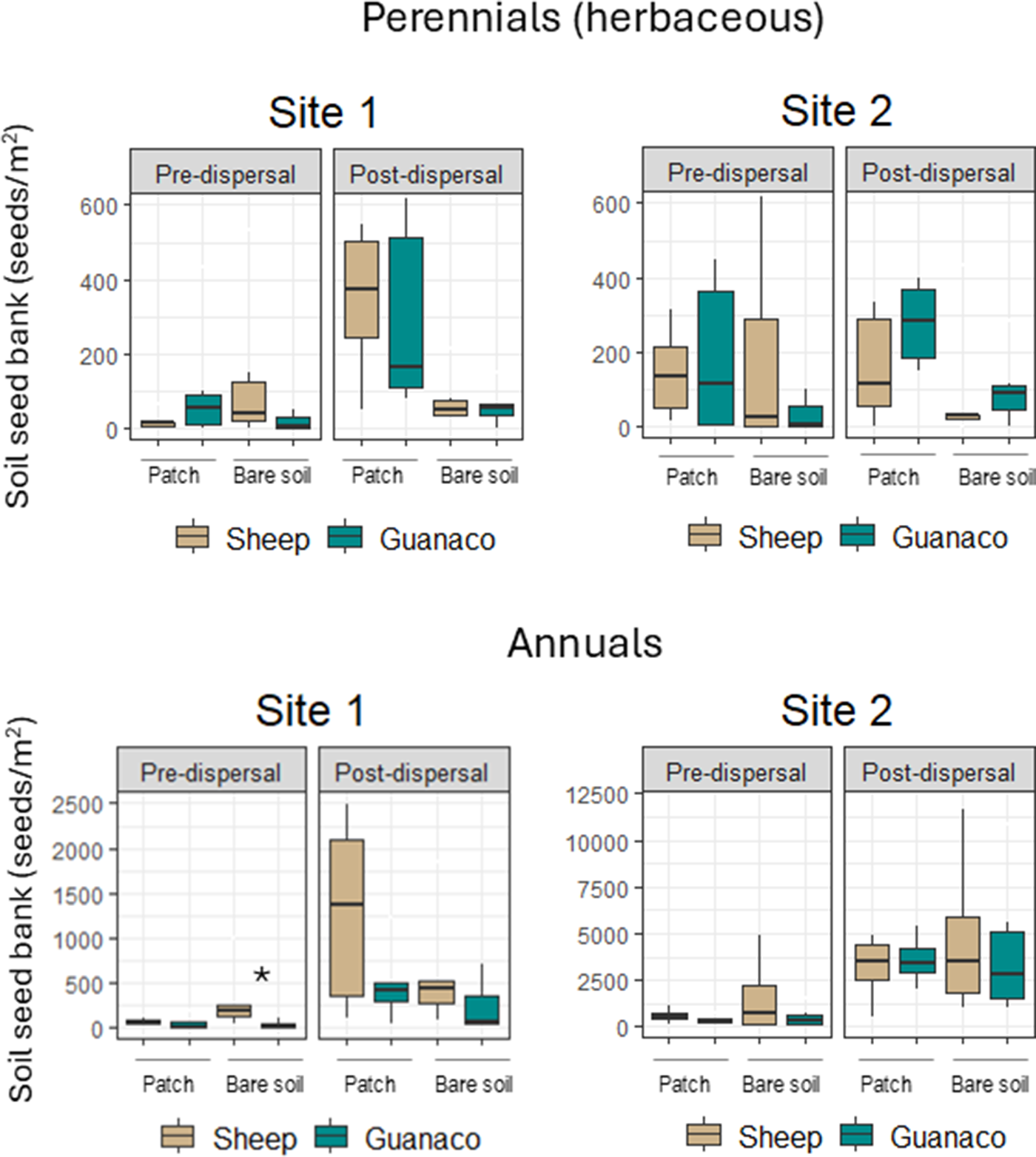

Overall, the soil seed bank of vegetated patches and bare soil was largely composed of annual species (~70–90% of total); perennial herbaceous species (mostly grasses) represented 30% of the pre- and 10% of the post-dispersal bank, whereas shrubs were completely absent despite their high plant cover (Figure 2 and Figure S1, Supplementary Material). We did not detect significant differences between herbivores, except for a greater abundance of annual species in the bare soil of sheep location of site 1, during pre-dispersal (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pre- and post-dispersal soil seed banks of perennial and annual herbaceous species from two sites of the Patagonian shrub-steppe subjected to grazing by either sheep or guanaco. Soil seed banks of vegetated patches and bare soil are analyzed by independent ANOVA tests. Samples represent pooled data of two years (pre-dispersal: September 2014 and 2015, and post-dispersal: March 2015 and 2016). Note that the y-axis magnitude of annuals differs between sites. The asterisk indicates significant differences between herbivores (p < 0.05). Shrubs are not included, as we did not detect seeds in the soil seed bank.

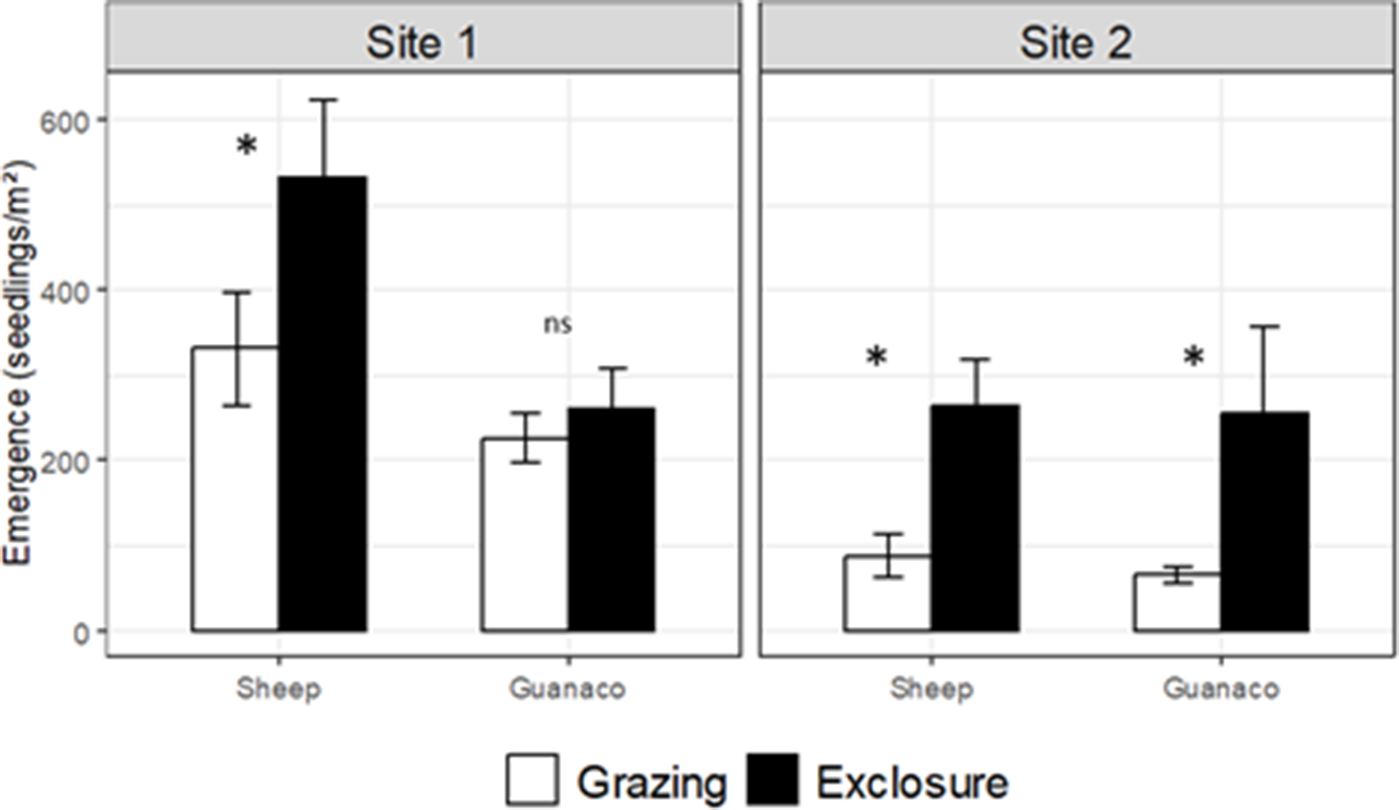

Seedling emergence significantly increased after short-term exclusion of both herbivores (Figure 3). in site 2, short-term grazing exclusion increased total seedling emergence by ~200–300% relative to grazed conditions, whereas in site 1 the increase was more modest (≈60% under sheep grazing) and negligible under guanaco grazing (Figure 3). in site 2, where stocking rate was half of carrying capacity, short-term exclusion of grazing increased seedling emergence by two- or three-fold (Figure 3 right panels). Conversely, in site 1, with higher stocking rates, we detected a ~ 60% greater seedling emergence due to short-term exclusion for sheep while guanaco had similar emergence (Figure 3 left panels). The highest emergence, overall, was recorded in winter, after the dispersion peak (Supplementary Table S2). This pattern was more consistent in site 1, whereas in site 2 it was recorded a peak in spring, particularly remarkable in the exclosures of the sheep location (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3. Total seedling emergence (accumulated records from April 2015 to January 2016) in two sites of the Patagonian shrub-steppe grazed by either sheep or guanaco and their respective short-term exclusions. The asterisks indicate significant differences between grazing and exclosure levels (p < 0.05).

Interestingly, seedling emergence showed a clearer positive response to grazing exclusion at site 2 than at site 1, despite site 1 experiencing substantially higher stocking rates. This pattern suggests that factors beyond current grazing pressure may influence recovery. Site 1’s high grazing intensity may have resulted in more depleted or compacted soils, reduced seedling microsites or legacy effects from historical overgrazing, limiting the immediate response of seedlings to herbivore exclusion. In contrast, site 2, with lower grazing pressure and potentially more favorable microsite conditions, allowed seedlings to respond more strongly to short-term exclusion. These observations highlight that grazing effects interact with local environmental conditions and land-use history, and that high stocking rates do not always translate directly into stronger suppression of early regeneration.

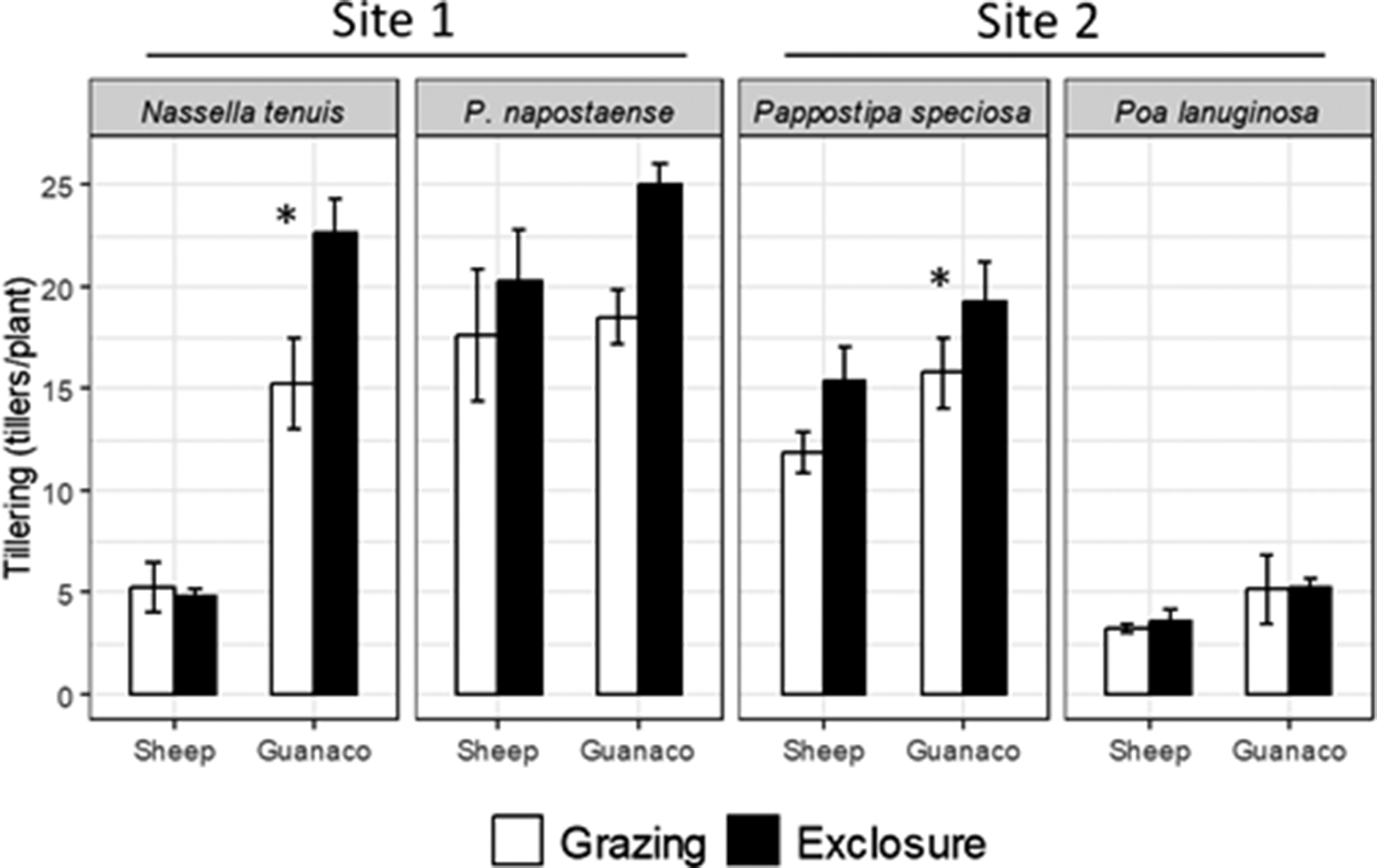

Tiller production only responded positively to guanaco short-term grazing exclusion (Figure 4). We detected a greater tiller production only after guanaco short-term exclusion; it was statistically significant (p < 0.05) for N. tenuis (site 1) and in P. speciosa (site 2) and marginal (p = 0.09) for P. napostaense (site 1) (Figure 4). In contrast, P. lanuginosa (site 2) was not responsive to short-term exclusion of guanaco (Figure 4). Surprisingly, short-term exclusion of sheep did not affect tiller production of any of the studied grasses (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Tiller production of the four most representative species from two experimental sites in the Patagonian shrub-steppe. Sampling corresponds to locations grazed by either guanaco or sheep and their corresponding short-term grazing exclosures. Note the different magnitudes of the axes and between species. Values correspond to the total tiller count, obtained on the last measurement date (summer 2016). Significant effects of the date are not indicated for simplicity. The asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). The complete datasets are presented in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Figures S3 and S4).

We explicitly tested site × treatment interactions for all response variables, but none of them were statistically significant. This indicates that the magnitude and direction of grazing-exclusion effects were similar between sites, despite contrasting vegetation structure and stocking rates. Accordingly, the patterns observed in seed bank dynamics, seedling emergence and tiller production represent consistent responses across sites rather than site-specific effects.

Discussion

Guanaco and sheep negatively affected different components of plant regeneration in the Patagonian shrub steppe. On the one hand, we found that the soil seed bank of areas grazed by either sheep or guanaco was similar. On the other hand, we detected positive responses of seedling emergence after short-term grazing exclusion of both herbivores. In addition, we also documented a positive tillering response after short-term guanaco exclusion and no significant effects of sheep short-term exclusion. Ultimately, our study offers empirical evidence of the substantial similarity between the soil seed banks of areas grazed by sheep and guanaco, partially contradicting our hypothesis of sheep having a more detrimental impact compared to guanaco.

Taken together, our results highlight that different components of plant regeneration respond in distinct ways to grazing and short-term exclusion in the Patagonian shrub-steppe. While the similarity in soil seed banks between sheep- and guanaco-grazed areas suggests that long-term seed inputs are not strongly filtered by herbivore identity, post-dispersal processes such as seedling emergence and vegetative regeneration appear more sensitive to grazing intensity, grazing history and herbivore traits. This decoupling between seed availability and establishment underscores the importance of microsite conditions, soil structure and disturbance legacies in regulating early regeneration stages, rather than seed limitation per se (Bisigato and Bertiller, Reference Bisigato and Bertiller2004; Franzese et al., Reference Franzese, Ghermandi and Gonzalez2016). Consequently, grazing impacts on regeneration cannot be inferred from seed bank size alone, but must be evaluated across multiple demographic stages.

It is important to acknowledge that the areas grazed by sheep and guanacos were located in neighboring ranches and reserves, respectively, and were therefore not randomly assigned. As a result, differences attributed to herbivore identity may partially reflect broader land-use contrasts, including divergent management histories, grazing legacies, habitat selection processes and reserve versus ranch contexts. For instance, sheep-grazed areas may bear stronger historical grazing pressure, greater soil disturbance or different vegetation trajectories compared with areas occupied primarily by guanacos, which could influence seedling microsites, soil properties or plant community structure independently of current herbivory (Cheli et al., Reference Cheli, Pazos, Flores and Corley2016). Conversely, reserves may offer more heterogeneous habitats or reduced human interference, potentially affecting guanaco distribution and foraging behavior (Schroeder et al., Reference Schroeder, Rodríguez, Marino, Panebianco and Peña2022; Puig et al., Reference Puig, Videla and Rosi2023). These contextual factors inherently confound the interpretation of herbivore effects and limit our ability to attribute observed differences solely to sheep or guanacos. Therefore, our results should be viewed as emerging from the combined influence of herbivore identity and land-use history, rather than from strictly controlled comparisons, and future work explicitly incorporating spatially replicated contrasts within land-use categories would help disentangle these effects.

Taking into account the limitations inherent in interpreting grazing effects of wild animals in protected areas, as well as the competitive exclusion that sheep impose in ranching contexts (Baldi et al., Reference Baldi, Pelliza-Sbriller, Elston and Albon2004; Flores et al., Reference Flores, Cingolani, von Müller and Barri2012; Marino et al., Reference Marino, Rodríguez and Schroeder2020), our findings indicate that grazing exclusion had a comparable positive effect on seedling emergence (20–30%) for both herbivores. This denotes their critical role of both domestic and wild herbivores controlling plant sexual recovery (Bullock et al., Reference Bullock, Hill and Silvertown1994; Defosse et al., Reference Defosse, Robberecht and Bertiller1997). Nevertheless, the greater seedling density relative to the size of the seed bank in areas grazed by guanaco would suggest a milder condition for seedling establishment with respect to the areas grazed by sheep. Despite our exclosure design also excluded small wild herbivores (choique, mara and European hare), and thus the grazing exclusion effect should not be completely attributed to sheep and guanaco, local literature indicates that small size herbivores are much less important than guanaco and sheep (Nabte et al., Reference Nabte, Saba and Monjeau2009, Reference Nabte, Marino, Rodriguez, Monjeau and Saba2013).

Interestingly, seedling emergence exhibited a clearer positive response to grazing exclusion at site 2 than at site 1, despite the fact that site 1 experienced substantially higher stocking pressure. This pattern suggests that current grazing intensity alone does not fully determine short-term regenerative responses. At site 1, prolonged overstocking and its cumulative grazing legacy may have produced more compacted soils, reduced infiltration, fewer suitable microsites for establishment or lower seedling resilience, thereby limiting the capacity of seedlings to respond rapidly to herbivore exclusion. In contrast, site 2 – where stocking rates remained below carrying capacity – likely retained more favorable soil structure, higher microsite availability and a less degraded understory, enabling a stronger and more immediate emergence response once grazing pressure was temporarily removed. These differences highlight the importance of grazing history and ecological legacies in shaping early recovery, and suggest that areas subjected to chronic overgrazing may require longer exclusion periods or additional management interventions before displaying detectable improvements.

From a management perspective, the positive response of seedling emergence to short-term grazing exclusion for both sheep and guanaco indicates that grazing-rest strategies can promote early stages of sexual regeneration in Patagonian rangelands. However, the contrasting magnitude of responses between sites suggests that the effectiveness of short-term exclusion strongly depends on grazing history and degradation status. In areas with prolonged overstocking, short-term exclusion alone may be insufficient to rapidly improve establishment conditions, and longer rest periods or reductions in stocking rates may be required. Conversely, in systems maintained below carrying capacity, even brief grazing exclusion may be effective in enhancing recruitment, highlighting the importance of preventing chronic overgrazing to retain ecosystem resilience.

Short-term grazing exclusion allowed to detect a beneficial effect on the tillering of only two of the four species (N. tenuis and P. speciosa). Herbivore effects on tiller production have received little attention, although our results agree with evidence obtained by Oñatibia and Aguiar (Reference Oñatibia and Aguiar2019), who also found beneficial effects of moderate grazing and grazing-rest management. In our study, the stocking rate of site 1 doubled the estimated carrying capacity, whereas in site 2, the stocking rate was half of the estimated carrying capacity. In this context, although sheep exclusion did not affect tiller production of any of the studied species, the positive response of guanaco exclusion across both sites suggests that grazing-rest strategies may be effective over a broader range of grazing intensities than previously documented.

The species-specific tillering responses observed in this study further suggest a functional group–dependent sensitivity to guanaco grazing. Guanaco exclusion enhanced tiller production in N. tenuis and P. speciosa, both medium-sized tussock grasses, and marginally affected a third tussock species, whereas P. lanuginosa, a small-stature grass, showed no detectable response. This pattern indicates that tussock grasses may be particularly sensitive to guanaco herbivory, likely due to their growth form, greater exposure of basal meristems and higher structural investment, which may increase vulnerability to defoliation. In contrast, short grasses, such as P. lanuginosa, may better tolerate grazing through rapid leaf turnover or lower grazing selectivity. This functional differentiation is consistent with recent findings by Cepeda et al. (Reference Cepeda, Oliva and Ferrante2024), who reported stronger negative effects of guanaco grazing on tussock grass cover and recruitment compared to short grasses in Patagonian systems, including similar responses in seedling establishment between grazed and protected areas. Together, these results highlight the importance of considering plant functional groups when evaluating grazing impacts and designing management strategies in Patagonian rangelands.

Our findings also have implications for the management of systems where domestic livestock and native herbivores coexist. The milder effects associated with guanaco grazing, particularly in terms of seedling establishment and vegetative responses, suggest that native herbivores may exert lower constraints on plant regeneration than sheep at comparable levels of forage use. This supports management approaches that explicitly differentiate between wild and domestic herbivores when estimating effective grazing pressure and designing stocking strategies. Incorporating guanaco densities into grazing assessments, rather than treating them as functionally equivalent to sheep, may improve the sustainability of mixed-use landscapes and reduce conflict between conservation and livestock production goals in Patagonia.

Another source of uncertainty arises from the fact that the estimated stocking rates and carrying capacities represent paddock-level averages, which may not accurately reflect the actual grazing pressure at the sampled plots. Herbivores in arid rangelands, such as the Patagonian shrub-steppe, typically exhibit spatially heterogeneous and selective grazing patterns, concentrating activity in preferred forage patches, areas near water points or sheltered microsites (Oñatibia and Aguiar, Reference Oñatibia and Aguiar2018). This spatial heterogeneity may decouple paddock-level animal loads from local grazing intensity, contributing to variability in vegetation and regeneration responses. Future research integrating indicators of animal spatial distribution (e.g., dung counts, track density and GPS-based movement patterns) with vegetation monitoring would help refine inferences about grazing pressure.

Finally, it is important to note that all responses documented in this study correspond to the first year after the establishment of the exclosures. Measurements of seed bank dynamics, seedling emergence and tillering were conducted between March 2015 and January 2016, capturing only early regenerative responses. Many demographic and structural vegetation changes in arid ecosystems require several years to manifest under grazing exclusion. Therefore, long-term monitoring is needed to determine whether the patterns observed here are maintained, attenuated or reversed over time, and to fully understand the cumulative impacts of sheep and guanaco on plant regeneration dynamics.

Conclusions

Our results show that although plant regeneration in the Patagonian shrub–steppe is affected by both sheep and guanaco grazing, the underlying mechanisms do not respond uniformly. The soil seed bank – dominated by annual species at both sites – did not differ between herbivores, indicating that the effects of grazing on seed accumulation and persistence are largely similar under guanaco and sheep. In contrast, herbivore exclusion significantly increased seedling emergence in both grazing contexts, highlighting the central role of herbivory in limiting sexual plant recovery.

Vegetative regeneration exhibited a contrasting pattern: guanaco exclusion stimulated tiller production in two of the four perennial grasses evaluated, whereas sheep exclusion produced no detectable effect. These results suggest that although both herbivores restrict regeneration from seeds, guanaco grazing may have weaker – or more readily reversible – effects on the vegetative recovery of some key species.

Additionally, the absence of significant site × treatment interactions indicates that these responses were consistent despite local differences in vegetation structure, land-use history and the relationship between stocking rate and carrying capacity. However, the relatively short duration of the experiment limits the extrapolation of these findings to long-term dynamics, particularly in arid ecosystems where demographic and recovery processes tend to manifest gradually.

Taken together, this study provides novel comparative evidence on how two coexisting herbivores – one domestic and one native – affect different components of plant regeneration. Our results underscore the need to explicitly incorporate guanaco abundance into stocking-rate assessments and management strategies, especially in productive landscapes where wild herbivores share forage resources with livestock. Implementing grazing-rest periods or temporary reductions in grazing pressure may enhance both seedling recruitment and vegetative regrowth of perennial grasses, contributing to the ecological and productive sustainability of Patagonian shrub–steppes.

Open peer review

For open peer review materials, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2026.10017.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2026.10017.

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Agricultural Technology, with the collaboration of the ranchers and reserve managers. The authors would like to particularly thank G. Buono for their contributions and permanent support, and M. Oesterheld, I. Clich and M. Sorondo for their contribution in different stages. G. Pazos and V. Rodríguez contributed with critical advice on guanaco ecology. The authors would also like to thank M. Poca and A. Bisigato who highly contributed to improving a previous version of this manuscript.

Author contribution

MVP, MS and VMP designed the study, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. MVP and VMP performed the experimental work. JS contributed to the statistical analyses and results discussion. All authors contributed to the critical reading of the manuscript and gave their final approval for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

Trelew, Argentina, 4 November, 2025

Editor-in-Chief

Journal Cambridge Prisms: Drylands.

Please find attached the manuscript entitled ‘Sheep and guanaco effects on plant regeneration of two Patagonian shrub-steppes’ co-authored by Valeria Pecile, M. Semmartin, V. Massara Paletto and José Saravia, to be considered for publication in Journal Cambridge Prisms: Drylands.

Briefly, this study investigated, for the first time, the comparative effects of grazing by guanacos and sheep on plant regeneration of a semiarid rangeland. In the Patagonian shrub-steppe, extensive sheep production is based on natural vegetation and coexists with guanaco, the most abundant native wild herbivore. While the impact of sheep on plant growth and regeneration is well documented, empirical evidence on the effects of guanaco is virtually nonexistent, which undermines accurate estimates of the actual stocking rate for sustainable sheep production.

We comparatively investigated the impact of grazing by sheep and guanaco on sexual and asexual plant regeneration by two field studies. Briefly, we found that plant regeneration by seedling emergence was similar for both herbivores and was similarly benefited by short-term grazing exclusion. In contrast, regeneration by tillering of perennial grasses was more impaired by sheep than by guanaco in four grasses studied.

Since our results reveal a considerable similitude in terms of the impact on plan regeneration, we highlight the importance of a thorough recording of guanaco stocking rate in continuous grazing or grazing-rest management programs. We conclude that our findings contribute to improve range management of these semi-arid lands.

None of the material included in this paper has been published or is under consideration for publication elsewhere. We hope you will find the manuscript suitable for publication.

With many thanks for your consideration.

Yours sincerely,

Valeria Pecile