Introduction

Wetlands are vital ecosystems for biodiversity, supporting many species of conservation concern that depend on them (Balian et al. Reference Balian, Segers, Martens, Lévéque, Balian, Lévêque, Segers and Martens2008; Dudgeon et al. Reference Dudgeon, Arthington, Gessner, Kawabata, Knowler and Lévêque2006; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Whitfield, Biggs, Bray, Fox and Nicolet2003). Although wetlands were the focus of the first global conservation treaty, the Ramsar Convention, adopted more than 50 years ago, it must be recognised that wetland degradation and loss continue globally, particularly in inland areas (Davidson Reference Davidson2014; Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, Barchiesi, Beltrame, Finlayson, Galewski and Harrison2015; McInnes et al. Reference McInnes, Davidson, Rostron, Simpson and Finlayson2020). Among the primary threats to wetland species are land reclamation for agricultural purposes and alterations in water use (Davidson Reference Davidson2014; Dudgeon et al. Reference Dudgeon, Arthington, Gessner, Kawabata, Knowler and Lévêque2006). In this context, understanding how animals utilise space – especially their responses to the increasing unpredictability and depletion of food resources due to global change – becomes crucial (Grémillet and Boulinier Reference Grémillet and Boulinier2009; Kingsford et al. Reference Kingsford, Roshier and Porter2010; Platteeuw et al. Reference Platteeuw, Foppen and Eerden2010; Ramírez et al. Reference Ramírez, Rodríguez, Seoane, Figuerola and Bustamante2018).

Waterbirds are considered valuable flagship species for driving management actions aimed at wetland conservation because (1) they are highly sensitive to changes in wetland suitability due to their high position in the food chain (Amat and Green Reference Amat, Green, Hurford, Schneider and Cowx2010; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Li, Wu, Sun, Feng and Zhao2023; Sergio et al. Reference Sergio, Caro, Brown, Clucas, Hunter and Ketchum2008), and (2) they are more popular and extensively studied compared with other groups (Becker Reference Becker, Markert, Breure and Zechmeister2003; Green and Elmberg Reference Green and Elmberg2014; Hafner Reference Hafner1997). Among them, terns of the genus Chlidonias (also known as Marsh Terns) are long-distance migrants that breed in highly fragile, unpredictable, and sometimes ephemeral inland water-bodies (primarily fish-ponds and flooded grasslands), characterised by dynamic water budgets, some of which may dry out during the breeding season (Ledwoń et al. Reference Ledwoń, Neubauer and Betleja2013; Paillisson et al. Reference Paillisson, Reeber, Carpentier and Marion2006; van der Winden et al. Reference van der Winden, Beintema and Heemskerk2004). For instance, site occupancy studies have shown low site fidelity in the Black Tern Chlidonias niger, likely due to the considerable instability of wetland habitat conditions (Shephard et al. Reference Shephard, Szczys, Moore, Reudink, Costa and Bracey2023). Meanwhile, little is known about the fine-scale space use by Marsh Terns during breeding (Chapman Mosher Reference Chapman Mosher1986; McKellar and Clements Reference McKellar and Clements2023), despite the fact that such data are crucial for designing effective conservation strategies (Allen and Singh Reference Allen and Singh2016; Katzner and Arlettaz Reference Katzner and Arlettaz2020). This knowledge gap is particularly relevant for the Whiskered Tern Chlidonias hybrida.

The Whiskered Tern is currently classified as ‘Least Concern’ globally, with a broad distribution and a population that is increasing, although with varying trends across countries (BirdLife International 2022). In France, where the study took place, the species is listed as ‘Vulnerable’ and breeds only in a few large wetland regions (MNHN et al. 2020). In the historical stronghold of La Brenne (central France), the Whiskered Tern has experienced a fluctuating demographic trend over the past four decades (Caupenne Reference Caupenne and Issa2015), with a slight decline over the last 15 years (authors, unpublished data). In this area, the primary threats to Whiskered Terns are believed to be intensive fish-farming practices (which lead to a degradation of aquatic vegetation where the terns build their nest; Paillisson et al. Reference Paillisson, Reeber, Carpentier and Marion2006) and the alteration of pond water budget due to global change (Lledó et al. Reference Lledó, Mateo and Moliner2018; Rocamora and Yeatman-Berthelot Reference Rocamora and Yeatman-Berthelot1999; and as noted in other waterbirds, Ma et al. Reference Ma, Cai, Li and Chen2010; Ramírez et al. Reference Ramírez, Rodríguez, Seoane, Figuerola and Bustamante2018; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zhou and Song2015).

To date, in the absence of more suitable methods, foraging habitats used by Whiskered Terns have been inferred either from the identification of prey (aquatic and terrestrial) delivered to partners or chicks at nest-sites, but without precise information about the actual foraging sites (e.g. Dostine and Morton Reference Dostine and Morton1989; Paillisson et al. Reference Paillisson, Reeber, Carpentier and Marion2007), or through direct observation of birds foraging in specific areas, but without knowing their colonies of origin (Ortiz Lledó Reference Ortiz Lledó2016; Wiles and Worthington Reference Wiles and Worthington1996). However, identifying foraging areas and understanding how they are used over time is critical from a conservation perspective. With advancements in bio-logging, particularly the reduction in the mass of solar-powered transmitters, it is now possible to study the movements of small terns (100–150 g) over extended periods (Buck et al. Reference Buck, Sullivan, Teitelbaum, Brinker, McGowan and Prosser2022; Martinović et al. Reference Martinović, Galov, Svetličić, Tome, Jurinović and Ječmenica2019; Morten et al. Reference Morten, Burgos, Collins, Maxwell, Morin and Parr2022; Paton et al. Reference Paton, Loring, Cormons, Meyer, Williams and Welch2020). Two recent studies explored space use in Chlidonias species: one in the Black Tern using satellite transmitters (McKellar and Clements Reference McKellar and Clements2023) and one in the Black-fronted Tern Chlidonias albostriatus using GPS-bluetooth transmitters (Gurney Reference Gurney2022), but no study has yet been conducted on the Whiskered Tern.

In the present study, we provide the first fine-scale tracks of Whiskered Terns during the breeding season, based on a small sample size. The main objective was to describe how individuals use space throughout the breeding season, considering a set of quantitative indicators (i.e. home range, foraging distance, habitat use and selection, and fidelity to foraging grounds) as reference data for comparison with future studies, and to propose some research questions that could be addressed with further bio-logging investigations. These, in turn, could contribute to conservation efforts.

Methods

Study area and fieldwork

La Brenne (46°46′N, 01°10′E), also known as the land of a thousand fish-ponds, contains approximately 4,000 fish-ponds embedded within a landscape predominantly made up of semi-natural grasslands, woodlands, and heathlands, covering a total of 580 km2. Most of the ponds are privately owned and managed for fish farming and wildfowling (Trotignon et al. Reference Trotignon, Williams and Hémery1994). Ponds are typically drained every 7–10 years to maintain dykes and hydraulic works, and to facilitate the mineralisation of organic matter. Consequently, Whiskered Tern colonies establish in different ponds from year to year, depending on water levels and the development of vegetation beds. During the breeding season of 2023, Whiskered Terns bred in 14 fish-ponds, totalling 835 pairs.

Four adult Whiskered Terns were captured at their nest during incubation in three distinct colonies using a tent trap. They were banded and equipped with solar-powered GPS-UHF transmitters (nanoFix GEO+RF) manufactured by Pathtrack® (Otley, UK). Details on capture and equipment (including practical recommendations for future studies) can be found in Supplementary material Appendix S1. Three body feathers were sampled for molecular sexing (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Double, Orr and Dawson1998; two males and two females). To prevent battery depletion, knowing that birds roost at night, the tags were programmed to record one location every 30 minutes between 03h00 and 21h00 GMT (i.e. approximately one hour before sunrise and one hour after sunset). Archived data were periodically downloaded using a mobile station from the pond shoreline, 200–300 m from the focus nests.

Phenology

The timing of breeding for each equipped individual was estimated based on the age of eggs at capture (Paillisson et al. Reference Paillisson, Reeber, Carpentier and Marion2007) (Appendix S1) and an average incubation duration of 21 days (Cramp Reference Cramp1985; Gochfeld and Burger Reference Gochfeld, Burger, del Hoyo, Elliott and Sargatal1996; authors’ personal observations). Estimated hatching dates were validated through daily observations made around the hatching period from the pond shoreline using a telescope. Locations were thus categorised into four distinct periods, i.e. pre-incubation, incubation, rearing, and post-breeding – the latter being characterised by birds continuing to move around the colony pond after the rearing period – to explore space use by birds across time (Table 1).

Table 1. Tracking days (with the number of GPS fixes and % foraging locations in brackets) and home range sizes (95% kernel density estimates, KDE95 in km2, with the maximum distance (in km) from the nest location) for the four equipped Whiskered Terns during the breeding periods. A dash (–) indicates that no tracking was available. Additional details on the method used to identify foraging positions are provided in the main text

Two birds (47420 and 47816) abandoned their respective nest the day after equipment deployment due to nest submersion following a severe thunderstorm. For these two birds, data presented below refer to renesting in a second colony.

Space use descriptors

Raw data were filtered to remove aberrant locations using an 80 km/hour speed threshold filter (maximum flight speed calculated in Whiskered Terns; authors unpublished data) between consecutive locations (0–2.8% of the original data depending on the individual also including missing locations).

We first calculated the home range size for each bird and each breeding period using 95% kernel density estimates (KDE95 in km2) based on all available locations (Lambert-93 projected coordinate system). We then calculated the home range overlap between subsequent pairs of periods, for each bird, as a proxy for fidelity to grounds surrounding the colony, more specifically, the proportion of the smallest KDE95 (in %) shared with the second one. These two metrics are commonly used in conservation research (Fieberg and Kochanny Reference Fieberg and Kochanny2005; Kie et al. Reference Kie, Matthiopoulos, Fieberg, Powell, Cagnacci and Mitchell2010; Powell Reference Powell, Boitani and Fuller2000). Finally, we calculated the distance to the nest (hereafter ‘nest distance’), defined as the straight-line distance between the nest and each recorded location.

We then filtered locations associated with foraging occasions. Typically, the activity of breeders can be divided into nest attendance and foraging, the latter primarily involving shallow plunge diving or capturing prey from the water surface or from aquatic/terrestrial plants (Gwiazda and Ledwon Reference Gwiazda and Ledwon2015; Paillisson et al. Reference Paillisson, Reeber, Carpentier and Marion2006). Visual inspection of frequency histograms of nest distance revealed a first peak in distances under 25 m for each individual and each breeding period, which were assigned to nest attendance – both members of the pair share nest attendance (Chambon et al. Reference Chambon, Latraube, Bretagnolle and Paillisson2020), though it cannot be excluded that birds may occasionally forage very close to their nests. In contrast, any location more than 25 m from the nest and located within ponds (even within the colony pond) or grasslands was considered a potential foraging position, based on a previous study (Latraube et al. Reference Latraube, Trotignon and Bretagnolle2006; see also the Discussion). Two data sources were used to characterise habitats: the water-body map of the Parc Naturel Régional de la Brenne (Parc Naturel Régional de la Brenne 2020) and the natural habitat map of the Indre department (CarHab, Cartographie des Habitats naturels; Bellenfant Reference Bellenfant2023). Accordingly, 4% of locations far from the nests did not match a foraging habitat (specifically woodlands and heathlands) and likely represented transient birds (birds flying between their nests and foraging areas). This selection resulted in, on average (mean ± SD), 20.4 ± 8.4 foraging positions per day and per bird during the breeding season (all birds combined).

We calculated two foraging descriptors. (1) The proportion (in %) of each habitat visited: ponds (including the pond where the colony is located and nearby ponds) and grasslands, for each bird across time. To detect habitat preferences, this proportion was compared with the proportion of ponds or grasslands (in %) in buffer areas centred on the nest with a radius corresponding to the maximum distance from the nest location observed during each breeding period (values are presented in Table 1). In practice, we randomly generated 10 times more locations in foraging habitats (pseudo presence) than observed foraging positions (as recommended by Fieberg et al. Reference Fieberg, Signer, Smith and Avgar2020) using the two aforementioned maps. (2) The mean nest distance (in km) for each habitat and breeding period (specifically, the mean of daily mean values to limit a possible sample size effect among individuals). This value was compared to the mean nest distance calculated from the randomly generated locations.

Due to small sample sizes, no statistical analyses were conducted; instead, we presented the main findings to stimulate further bio-logging research on the Whiskered Tern. All calculations were conducted in R (v.4.2.1.; R Core Team 2022) primarily using the packages amt (Signer et al. Reference Signer, Fieberg and Avgar2019), sf (Pebesma Reference Pebesma2018; Pebesma and Bivand Reference Pebesma and Bivand2023) and sp (Bivand et al. Reference Bivand, Pebesma and Gómez-Rubio2013; Pebesma and Bivand Reference Pebesma and Bivand2005).

Results

Overall, KDE95s were relatively restricted among individuals and throughout the season (ranging from 2.00 km2 to 14.95 km2; Table 1 and Figure 1), except during the post-breeding period when adults continued to return to their colony but travelled farther (22.45 km2 and 74.45 km2 for two individuals). KDE95 values varied across the season, but the small sample size prevented us from testing any particular trend (Table 1). In all cases, the overlap in the home range between subsequent periods was high, ranging from 82% to 100% (as shown in Figure 1). Additionally, for all individuals combined, 95% of the locations were on average within 1.87, 2.73, 2.96, and 8.15 km of the nests during rearing, pre-incubation, incubation, and post-breeding, respectively (mean daily nest distance for each bird is provided in Appendix S2).

Figure 1. Home ranges (95% kernel density estimates) of the four breeding Whiskered Terns across distinct breeding periods (when applicable): pre-incubation (orange), incubation (green), rearing (blue), and post-breeding (red). The nest location is marked by a black dot. Ponds (blue) and grasslands (green) are also shown on the maps.

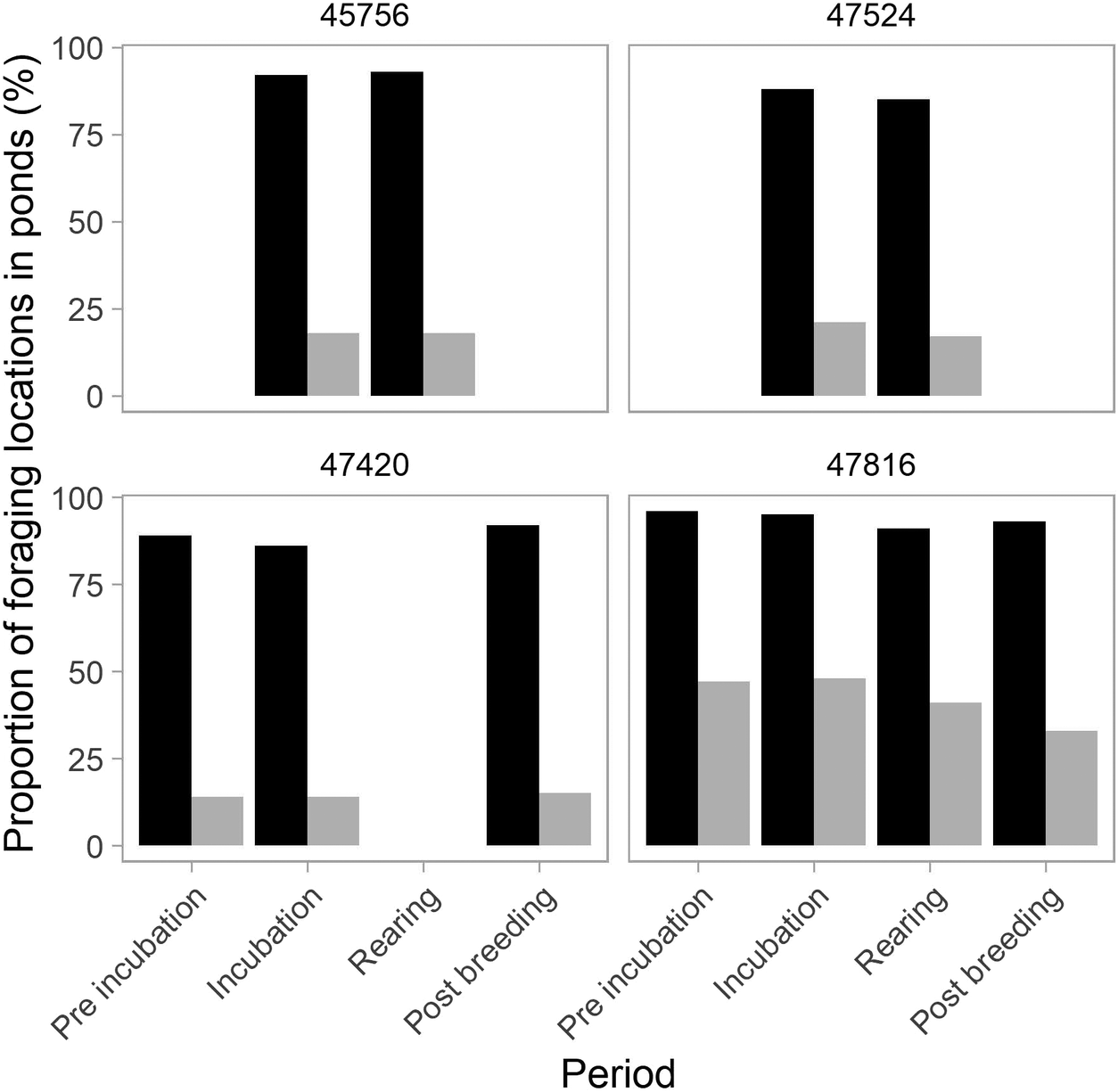

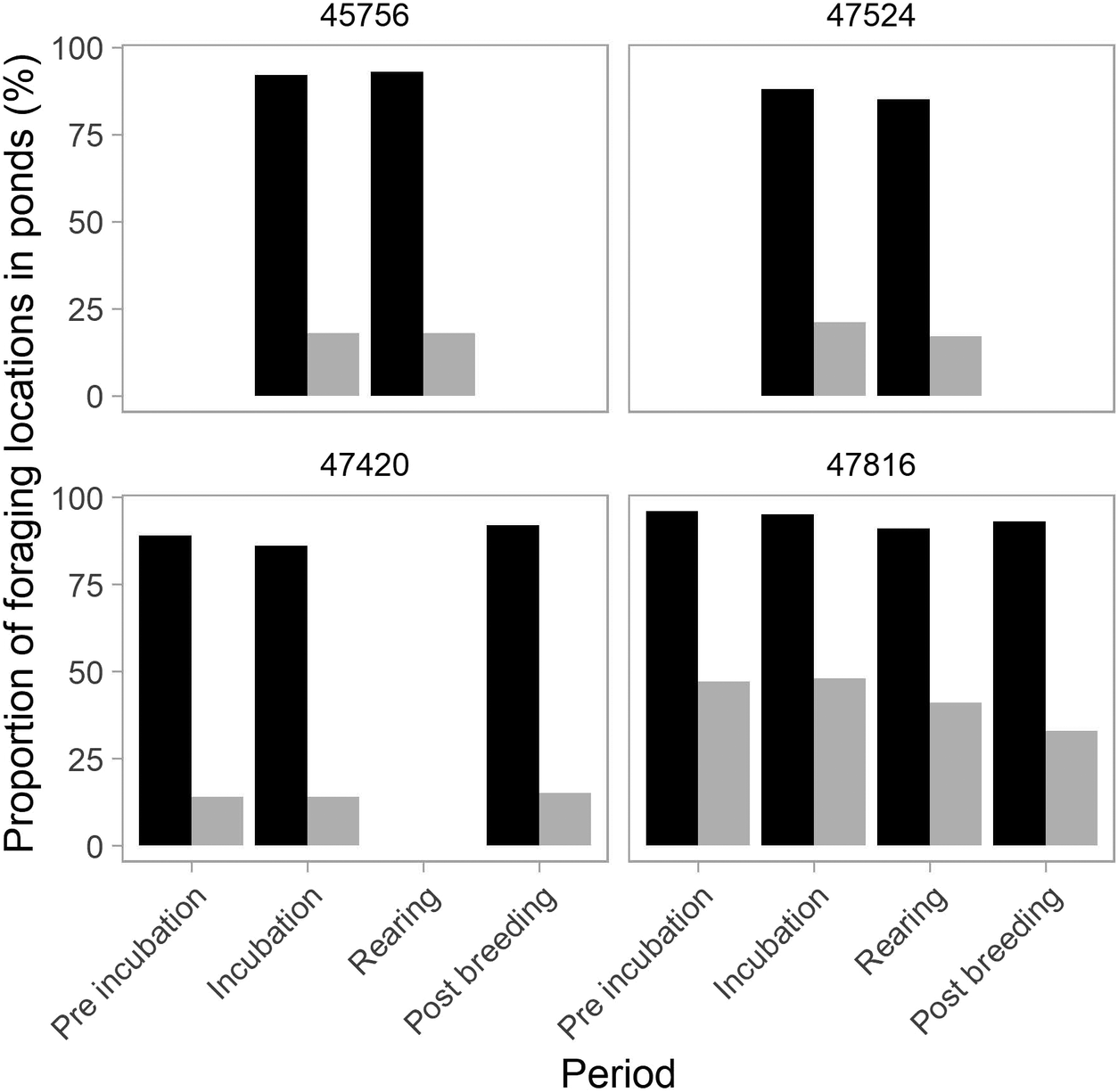

Whiskered Terns foraged primarily within ponds across all periods (mean ± SD: 91 ± 4% (range: 85–96%) of all foraging positions compared with 9 ± 4% (5–15%) in grasslands (Figure 2). They foraged particularly within the colony pond during incubation (63%, on average, 33–80% depending on the individual), compared with 33% (range: 32–34%) during chick rearing (Appendix S3). Whiskered Terns were much more frequently found foraging in ponds compared with the proportion of randomly generated locations in ponds throughout the season (observed: 85–96% vs randomly generated: 14–48%), while they were, complementarily, less frequently found in grasslands (observed: 4–15% vs randomly generated: 52–86%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Variation in the percentage of foraging positions occurring in ponds for the four Whiskered Terns across breeding periods. Recorded locations are represented in black, while randomly generated locations are in grey. Values for grasslands, the second foraging habitat (not shown), can be inferred visually.

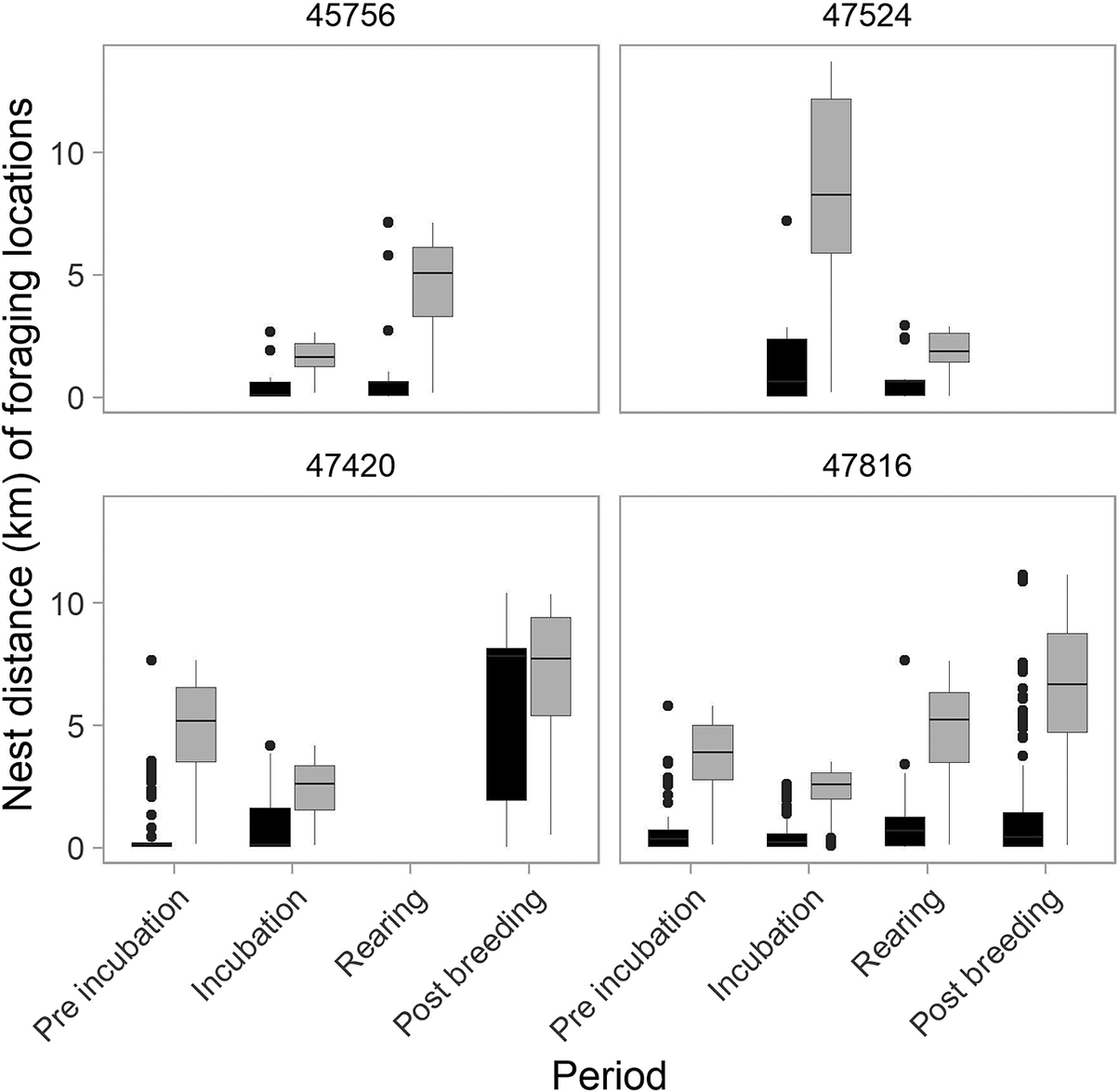

Additionally, they foraged preferentially close to their colony compared with the distribution of foraging habitats in buffer areas (Figure 3; see also density plots in Appendix S4).

Figure 3. Comparison of nest distances between recorded (black) and potential (randomly generated, grey) foraging locations within ponds across breeding periods.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that most of the daily nest distances of breeding Whiskered Terns did not exceed 2–3 km (up to 8 km during the post-breeding period), resulting in restricted home-range sizes, and that birds preferentially visited ponds close to their colony throughout the season. The small sample size, however, prevented the detection of a clear pattern in space use over time, though birds appeared to remain faithful to their foraging grounds near their colonies.

To date, no comparable bio-logging study on this species has been conducted. However, Gwiazda and Ledwon (Reference Gwiazda and Ledwon2015) observed that Whiskered Terns foraged at distances up to 2 km from their colony in a Polish breeding area, which shares similarities with our study area (a complex of fish-ponds). Thus, the nest distance values observed in both regions are quite similar. Future research could examine how different landscape types, particularly in terms of habitat composition and heterogeneity, influence the foraging behaviour of Whiskered Terns to better understand their habitat needs. For example, it is plausible that in wetland regions dominated by croplands, with a lower density of foraging habitats (such as ponds), birds might need to travel longer distances, crossing unsuitable areas, to reach more fragmented foraging sites (Evens et al. Reference Evens, Beenaerts, Neyens, Witters, Smeets and Artois2018; McKellar and Clements Reference McKellar and Clements2023). We encourage further studies to investigate this issue and assess its potential impact on the breeding success of Whiskered Terns. The only documented data on daily nest distances in Chlidonias species come from studies on Black Terns and Black-fronted Terns. For Black Terns, nest distances ranged from a mean of 2.4 km (Chapman Mosher Reference Chapman Mosher1986, based on visual tracking of nesting birds) to 8.9 km (McKellar and Clements Reference McKellar and Clements2023, using bio-logging). These findings suggest that foraging distances in Black Terns are likely site-specific and are strongly influenced by the spatial arrangement of suitable foraging habitats. Similarly, for Black-fronted Terns, nest distances varied across colonies, with mean values ranging from 3.8 km to 7.9 km (Gurney Reference Gurney2022). These results align with the idea that landscape features may influence the movements of breeding Marsh Terns, as previously discussed. Consequently, future research is needed to better understand the habitat requirements of this central-place forager during nesting, as its foraging range is likely constrained by their need to return to their colony (as observed in other terns; Catlin et al. Reference Catlin, Gibson, Hunt, Weithman, Boettcher and Gwynn2024; Morten et al. Reference Morten, Burgos, Collins, Maxwell, Morin and Parr2022; Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, Ackerman, Eagles-Smith, Herzog and Hartman2018).

The fact that Whiskered Terns remained largely faithful to foraging areas close to their colonies throughout the breeding season suggests that the surrounding area is sufficiently suitable to meet their needs, even during chick rearing. This observation is consistent with findings in the Caspian Tern Hydroprogne caspia (Beal et al. Reference Beal, Byholm, Lötberg, Evans, Shiomi and Akesson2021). Notably, Whiskered Terns foraged primarily in ponds (91% of all foraging positions), which likely offered both preferred and more predictable prey compared with grasslands. This interpretation is supported by the fact that aquatic prey constitutes most of the diet of Whiskered Terns: 96% of visually identified prey brought back to the nests during chick-rearing are fish, amphibians or aquatic invertebrates (see Appendix S5) (Dostine and Morton Reference Dostine and Morton1989; Gwiazda and Ledwon Reference Gwiazda and Ledwon2015). In contrast, most grasslands were mown during chick rearing, a practice known to reduce the availability and accessibility of food resources (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Buckingham and Morris2004; Vickery et al. Reference Vickery, Tallowin, Feber, Asteraki, Atkinson and Fuller2001). Moreover, invertebrate prey in agricultural areas may offer lower energy or require greater time investment compared with fish, making them less optimal for successful chick-rearing (Baert et al. Reference Baert, Stienen, Verbruggen, Van de Weghe, Lens and Müller2021; Ledwoń and Neubauer Reference Ledwoń and Neubauer2017). This could explain why Whiskered Terns only visited grasslands opportunistically.

Remaining faithful to a small area around the colony, as we observed, offers several advantages: (1) access to social information from neighbouring conspecifics regarding high-quality foraging areas (Cecere et al. Reference Cecere, Bondì, Podofillini, Imperio, Griggio and Fulco2018; Wakefield et al. Reference Wakefield, Bodey, Bearhop, Blackburn, Colhoun and Davies2013;); (2) familiarity with the area, which likely increases foraging efficiency (Ramellini et al. Reference Ramellini, Imperio, Morinay, De Pascalis, Catoni and Morganti2022; Rebstock et al. Reference Rebstock, Abrahms and Boersma2022); (3) reduced energetic costs compared with long foraging trips (Si et al. Reference Si, Skidmore, Wang, Boer, Toxopeus and Schlerf2011). Additionally, breeding success in small terns is known to depend on the proximity of productive foraging areas (Perrow et al. Reference Perrow, Gilroy, Skeate and Tomlinson2011, for the Little Tern Sternula albifrons). Our findings may support this notion, suggesting that wetland regions with a high density of suitable ponds are beneficial for Whiskered Terns, as they do not need to travel far from their nests to find food. In contrast, long foraging distances, as observed in Black Terns (McKellar and Clements Reference McKellar and Clements2023), may be linked to the search for high-quality prey that is not available closer to the colony.

Sex-specific differences in space use may also exist in Whiskered Terns, as documented in other bird species exhibiting sexual size dimorphism (Camphuysen et al. Reference Camphuysen, Shamoun-Baranes, van Loon and Bouten2015; González-Solís et al. Reference González-Solís, Croxall and Wood2000; Gurney Reference Gurney2022; Quinn Reference Quinn1990). Notably, sexual dimorphism is more pronounced in Whiskered Terns than in other tern species (especially in terms of head and bill size; Ledwoń Reference Ledwoń2011). This could explain potential differences in foraging niches between males and females (Dostine and Morton Reference Dostine and Morton1989; Gwiazda and Ledwon Reference Gwiazda and Ledwon2015). Such differences may also arise from sex-related reproductive behaviours. For example, females generally exhibit greater nest attendance during nest building and incubation (Chambon et al. Reference Chambon, Latraube, Bretagnolle and Paillisson2020), which may make them less mobile than males, leading to less selective foraging and potentially shorter foraging distances. Sex-related differences in foraging behaviour could also vary with individual traits (e.g. body mass) or brood size/age (Gwiazda et al. Reference Gwiazda, Ledwoń and Neubauer2017), but this issue requires further investigation. Unfortunately, our data set was too small to explore these aspects.

Another limitation of our study was the assumption that all locations beyond the nest-site corresponded to foraging behaviours (except those that did not match a foraging habitat). While this assumption is likely accurate, the relative short distances to the nests and the 30-minute GPS fix interval made it difficult to distinguish between different behaviours (e.g. resting, foraging or travelling). More refined movement models (e.g. path-segmentation models; McClintock and Michelot Reference McClintock and Michelot2018) could help to better identify foraging behaviour based on speed and turning angle, but this would require higher-frequency data acquisition.

Looking ahead, additional bio-logging studies are necessary to (1) validate our preliminary findings on the space use of breeding Whiskered Terns at a fine spatial scale and (2) test the speculations presented here to improve our understanding of their habitat needs. Such data are crucial for informing conservation strategies. Current conservation efforts focus on preserving ponds with vegetation to support breeding colonies, but there is still a lack of detailed knowledge regarding the space use of Whiskered Terns around these colonies. Gaining reliable information on key questions – such as how far breeders travel daily, which foraging areas are critical, and which factors influence breeding productivity – will be essential for guiding effective conservation measures. This could include actions such as habitat protection, agri-environmental schemes, and other interventions to improve foraging opportunities.

In conclusion, this study provides unique insights into the daily movements of breeding Whiskered Terns using high-resolution bio-logging, marking the first step in exploring their movement ecology during the breeding season with the goal of informing conservation efforts. Furthermore, understanding the species’ itinerance outside the breeding season, including migration routes and potential staging and wintering areas (which remain poorly understood), is critical for developing a comprehensive conservation strategy across the full annual cycle (Marra et al. Reference Marra, Cohen, Loss, Rutter and Tonra2015). Again, bio-logging will be invaluable for exploring these aspects.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270925100294.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Vivien Airault (Parc Naturel Régional de la Brenne) who provided us with the map of water-bodies of La Brenne. We also thank Marie-Claire Martin (PEM platform, ECOBIO) who molecularly sexed birds, and Guillaume Abraham and Nicolas Rodet Heuze for their help during fieldwork, specifically in collecting behavioural observations during the rearing period. This study was made possible thanks to the unconditional support of the Réserve naturelle nationale de Chérine. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. This study meets the legal and ethical requirements of capturing, handling, and attaching GPS tags from the Centre de Recherches sur la Biologie des Populations d’Oiseaux (Licence number 432). Capture permit was delivered to L.B., A.C. and C.D.F. The data are available from the corresponding author upon request.