Introduction

Recent global studies reinforce the notion that financial difficulties can significantly impact both the quality and timeliness of veterinary care for companion animals, particularly among financially disadvantaged households (King et al. Reference King, Mueller, Dowling-Guyer and McCobb2022; Muldoon & Williams Reference Muldoon and Williams2024a,Reference Muldoon and Williamsb). Preventive care, such as vaccination, desexing, dental procedures, and parasitic control, is often delayed or forgone due to cost, causing health to deteriorate and, later, requiring more expensive interventions (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Wu and Morales2021).

The COVID-19 epidemic put further pressure on household budgets and worsened disparities as regards access to veterinary services, especially in rural and disadvantaged areas (Applebaum et al. Reference Applebaum, Tomlinson, Matijczak, McDonald and Zsembik2020; Bibbo et al. Reference Bibbo, Johnson, Drost and Sanders2022). The wider implications of the issue are increasingly becoming recognised, particularly through a welfare structure lens, which emphasises the mutual relations between animal welfare, human welfare and socioeconomic conditions (Protopopova Reference Protopopova2021). When pet guardians are unable to provide essential care, the emotional toll can contribute to stress and feelings of moral failure, which can affect animal welfare and the overall well-being of human families (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Wu and Morales2021). Despite an increasing focus on these concerns internationally, there has been a paucity of studies examining these dynamics in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ). Previous studies have noted concerns regarding the uptake and value of pet insurance (Gates et al. Reference Gates, Walker, Zito and Dale2019; Forrest et al. Reference Forrest, Awawdeh, Pearson and Waran2023), which can influence decisions about the financial stress of caring for companion animals.

Globally, pet guardianship is a widespread practice, with companion animals playing an integral role in the lives of millions of people (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Martin, Christian, Houghton, Kawachi, Vallesi and McCune2017). The human-animal bond brings many benefits, including companionship, emotional support, and improved physical and mental well-being (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Huang, Robinson, Wilson, Bulbulia and Sibley2020). However, alongside these positive aspects, pet guardianship also entails financial responsibilities that can pose challenges for many individuals and families. The costs associated with pet care, encompassing routine veterinary visits, vaccinations, preventive medications, and potential emergency treatments, can accumulate significantly over time (Gates et al. Reference Gates, Walker, Zito and Dale2019). These financial obligations can be particularly burdensome for low-income households, possibly leading to complicated decisions regarding their pets’ health and well-being (Applebaum et al. Reference Applebaum, Tomlinson, Matijczak, McDonald and Zsembik2020). Even people with stable incomes can find their finances strained by unexpected veterinary bills or specialised care.

Furthermore, the cost of veterinary care for pets is increasing due to advancements in small animal practice, including specialisation, complex diagnostics, and advanced treatments (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Garrett, Gilles, Houlihan, McCobb, Pailler, Putnam, Scarlett, Treglia, Watson and Wietsma2021). These increased costs are a major obstacle to accessing care for many animal guardians (Kipperman et al. Reference Kipperman, Kass and Rishniw2017; Benson & Tincher Reference Benson and Tincher2024). The increasing complexity of veterinary medicine also introduces ethical challenges, such as balancing patient interests with financial constraints and client expectations (Kipperman et al. Reference Kipperman, Kass and Rishniw2017; Springer et al. Reference Springer, Sandøe, Bøker Lund and Grimm2019; Quain et al. Reference Quain, Ward and Mullan2021). Veterinarians report that economic limitations affect their ability to ensure optimal care and contribute to burn-out (Kipperman et al. Reference Kipperman, Kass and Rishniw2017). Strategies to address these issues, such as improving customer education, discussing costs and pet insurance with customers, and implementing various care approaches, are recommended. Despite these challenges, better patient care and timely interventions (Ackerman Reference Ackerman2024) continue to enhance veterinarians’ ability to improve outcomes.

Pet health insurance offers several advantages, including an increased willingness to pay for veterinary care and a reduced likelihood of pre-surgical euthanasia (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Stevenson and Boller2021; Chiu et al. Reference Chiu, Li, Lhermie and Cazer2021). Insured pet guardians tend to spend more on veterinary services, potentially improving access to care (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Williams, Hansen and Coble2020). However, pet insurance has limitations, particularly for owners with limited financial resources who struggle to afford premiums or veterinary costs (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Volk and Kunzmann2022). The uptake of pet insurance remains relatively low, with only a minority of pet owners utilising it (Chiu et al. Reference Chiu, Li, Lhermie and Cazer2021). Factors influencing insurance adoption include education about treatment costs and disease risks (Chiu et al. Reference Chiu, Li, Lhermie and Cazer2021). While pet insurance can reduce the costs associated with veterinary clinics (Becker et al. Reference Becker, Volk and Kunzmann2022), its uptake has been slow (Paul & Skiba Reference Paul and Skiba2012).

Understanding the attitudes and experiences of pet guardians regarding the financial aspects of having a pet is crucial for promoting responsible pet care and ensuring the welfare of companion animals. Studies show that pet guardians generally report positive experiences, with women exhibiting higher bonding levels (Meier & Maurer Reference Meier and Maurer2022). However, financial costs represent a significant concern, especially for older adults with limited resources (Lian & Mathis Reference Lian and Mathis2016; Meier & Maurer Reference Meier and Maurer2022). Community-based veterinary programmes can help address these financial barriers (Kogan et al. Reference Kogan, Accornero, Gelb and Slater2021). Communication between veterinarians and pet guardians regarding costs remains a challenge, with differing perspectives on the value of services (Coe et al. Reference Coe, Adams and Bonnett2007). Attitudes towards responsible pet guardianship vary based on gender and guardian status (Selby et al. Reference Selby, Rhoades, Hewett and Irvin1979). Overall, promoting pet guardianship while addressing financial and practical concerns could enhance the well-being of both humans and animals (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Lord, Hill and McCune2015; Fox & Gee Reference Fox and Gee2019).

While Aotearoa NZ pet guardians generally recognise the importance of proper care practices, there are knowledge gaps, particularly around the need for regular veterinary visits and the impact of breeding on animal welfare (Gates et al. Reference Gates, Walker, Zito and Dale2019; Forrest et al. Reference Forrest, Awawdeh, Pearson and Waran2023). Also, studies have found that while pet guardians value the mental, physical, and social benefits of having a pet, the high costs of veterinary care and pet insurance are major concerns (Abra et al. Reference Abra, Granziera, Huijser, KMPMdB, Haddad and Paolino2019; Byard & Langlois Reference Byard and Langlois2020). Financial constraints have also been identified among NZ pet guardians, particularly for lower-income households, which often lead to compromised care or difficult decisions regarding their pets (Forrest et al. Reference Forrest, Awawdeh, Pearson and Waran2023).

Internationally, studies have shown similar trends. For instance, Abra et al. (Reference Abra, Granziera, Huijser, KMPMdB, Haddad and Paolino2019) and Byard and Langlois (Reference Byard and Langlois2020) reported that pet guardians value the mental, physical, and social benefits of pet ownership but are often burdened by the rising costs of veterinary care and insurance. Muldoon and Williams (Reference Muldoon and Williams2024b) further noted that financial constraints can compromise animal welfare and place emotional strain on pet owners in economically vulnerable households. Despite the importance of these issues, limited research exists on the attitudes of NZ pet guardians regarding financial responsibilities towards their pets. To address this knowledge gap, part of the Furry Whānau Wellbeing research study, funded by the NZ Companion Animal Trust (NZCAT), explored pet owners’ financial responsibilities, including the importance of pet insurance, the impact of veterinary costs, and the ethical considerations of owning a pet (Forrest et al. Reference Forrest, Pearson, Thomson, Bakri, Steiner and Waran2019). By shedding light on these multifaceted issues, this research explores methods for enhancing our communities’ understanding of their responsibilities as pet owners so we can implement effective behaviour change programmes to benefit the welfare of companion animals (dogs and cats) in NZ.

Furthermore, research on the financial aspects of pet guardianship not only addresses animal welfare and public health issues but also has the potential to impact the global targets established by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Specifically, this study contributes to SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), highlighting the importance of equitable access to veterinary care as an aspect of holistic well-being.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Eastern Institute of Technology Research and Ethics Approval Committee (REAC, ref: 19/53) and informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data collection

Data for this study were collected as part of the 2019 Furry Whānau Wellbeing research project funded by the NZCAT (Eastern Institute of Technology’s Research and Ethics Approval Committee ref: 19/53). Detailed information regarding participants, survey questions, and data collection methods can be found in Forrest et al. (Reference Forrest, Pearson, Thomson, Bakri, Steiner and Waran2019). In short, a nationwide online survey was open to NZ pet guardians aged 18 and over from January 8 to March 31, 2019. This study focuses on an in-depth analysis of the responses to Question 38 of the survey, which specifically addressed the economic impact of pet guardianship. The question read as follows: Please choose the option (Strongly agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, Strongly disagree) that most closely describes how you feel about the following statements: ‘Expense is a factor in the level of vet/animal healthcare that dogs and/or cats receive’; ‘If my income were higher, I would spend more money on my dog and/or cat’s health and well-being’; ‘Pet insurance is important’; ‘People should only own a pet if they can afford to keep it’; ‘Owning a pet has caused me financial stress (vet bills)’. The data presented in this study are available upon request from either of the corresponding authors (LA or RF).

Statistical analysis

Respondents had the option to skip any questions or sub-questions in the survey. The quantitative data, which consisted of forced responses to survey questions, were analysed using descriptive statistics. For each statement, cross-tabulations and Chi-squared and z-tests (α = 0.05, with Bonferroni corrections) were used to explore whether the respondents’ choices were associated with gender (female, male), ethnicity (Māori, NZ European, Other), age (18–24 years, 25–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, 55–64 years, 65–74 years, 75–84 years), income range (< NZ$14,000, NZ$14,000–NZ$48,000, NZ$48,000–NZ$70,000, NZ$70,000–NZ$100,000, > NZ$100,000, would rather not say), qualification level (1–10), whether they had a child or children (yes, no), whether they had a rural upbringing (yes no), or whether they were currently living in a town/city (yes, no).

To identify the most significant predictors of agreement for each statement, a forward stepwise binary logistic regression based on the likelihood-ratio test was employed. Three separate analyses were performed for the following dependent variables: (1) ‘Expense is a factor in the level of vet/animal health care that dogs and/or cats receive’; (2) ‘Pet insurance is important’; and (3) ‘People should only own a pet if they can afford to keep it’. For each variable, responses were coded as 1 for agreement (which included agree and strongly agree responses) and 0 for did not agree (which included neutral, disagree and strongly disagree responses). The probability for variable entry was set at P < 0.05, and for removal at P > 0.10. The overall significance of each final model was evaluated using the Omnibus Test of Model Coefficients, and the proportion of variance explained was estimated using the Nagelkerke R2 statistic. Odds ratios were calculated to interpret the effect of each significant predictor. All statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS® Statistics software (version 25). The qualitative data were derived from open-ended responses to Question 38, where participants were invited to describe how the financial cost of care affected their ability to support their pets. Two researchers analysed the qualitative data independently for emergent themes and categories using a general inductive approach (Thomas Reference Thomas2006) to minimise the likelihood of researcher bias.

Results

Demographic description of the respondents

A total of 2,744 individuals across NZ responded to the online survey. A detailed demographic breakdown of all respondents, including cat and dog owners, is provided in our previous publications (Forrest et al. Reference Forrest, Pearson, Thomson, Bakri, Steiner and Waran2019, Reference Forrest, Awawdeh, Esam, Pearson and Waran2022, Reference Forrest, Awawdeh, Pearson and Waran2023; Awawdeh & Forrest Reference Awawdeh and Forrest2024). The sample was predominantly female (92.3%), with males significantly underrepresented at 7.7%, compared to 49.4% in the 2018 NZ census. Māori were also underrepresented, comprising 8.3% of respondents compared to 16.5% nationally. Most respondents identified as NZ European (83.4%), followed by Other European (10.1%), with smaller proportions identifying as Māori, Pacific Peoples, Asian, or other ethnicities. Respondents represented all age ranges from 18 to 85+, with Māori present across all age groups except for those aged 85 and older.

Household income data were provided by 2,251 respondents and were relatively evenly distributed across income brackets above NZ$14,000. There was a noticeably lower representation of respondents reporting household incomes below NZ$14,000. Across ethnic groups, Māori and NZ European respondents were similarly represented across income brackets, although some regional and demographic variability was observed. Weak but statistically significant associations were found between income and the number of adults and children in the household. Of the 2,358 respondents who answered the pet guardian questions, 37.5% (n = 885) owned both types of pets, 28% (n = 652) were cat-only owners, and 26% (n = 609) were dog-only owners. Nine per cent (n = 212) of the respondents owned neither a cat nor a dog at the time of completing the survey but had been pet owners previously.

A total of 2,298 respondents answered Q38 and indicated their level of agreement with statements regarding the financial costs associated with pet care. The demographics for this subsample were similar to those of the entire sample, indicating there was no obvious selection bias associated with a particular demographic when choosing to answer (or skip) this question.

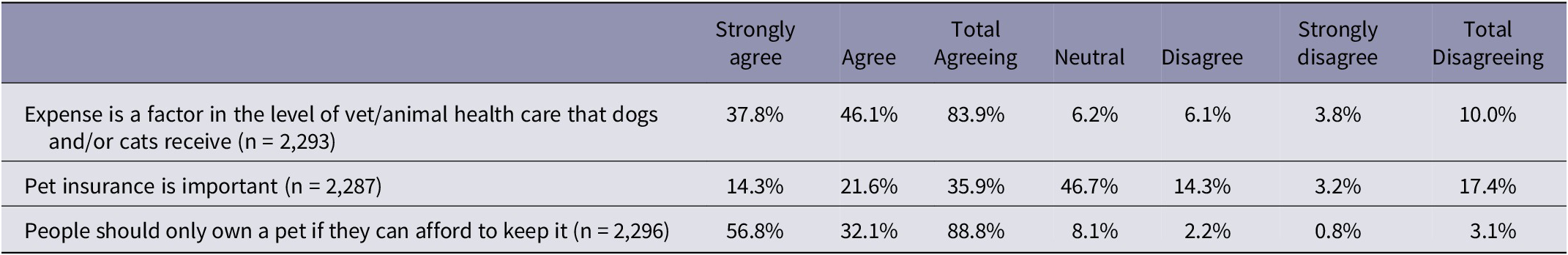

For each statement, there were between 2,287 and 2,296 responses. Table 1 shows that more than 80% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that expense is a factor in the level of healthcare that dogs and/or cats receive, and that people should only own a pet if they can afford to keep it. Only 36% of respondents considered pet insurance to be important.

Table 1. Percentages of 2019 New Zealand Pet Survey respondents selecting each level of agreement for each statement regarding certain financial aspects of pet care

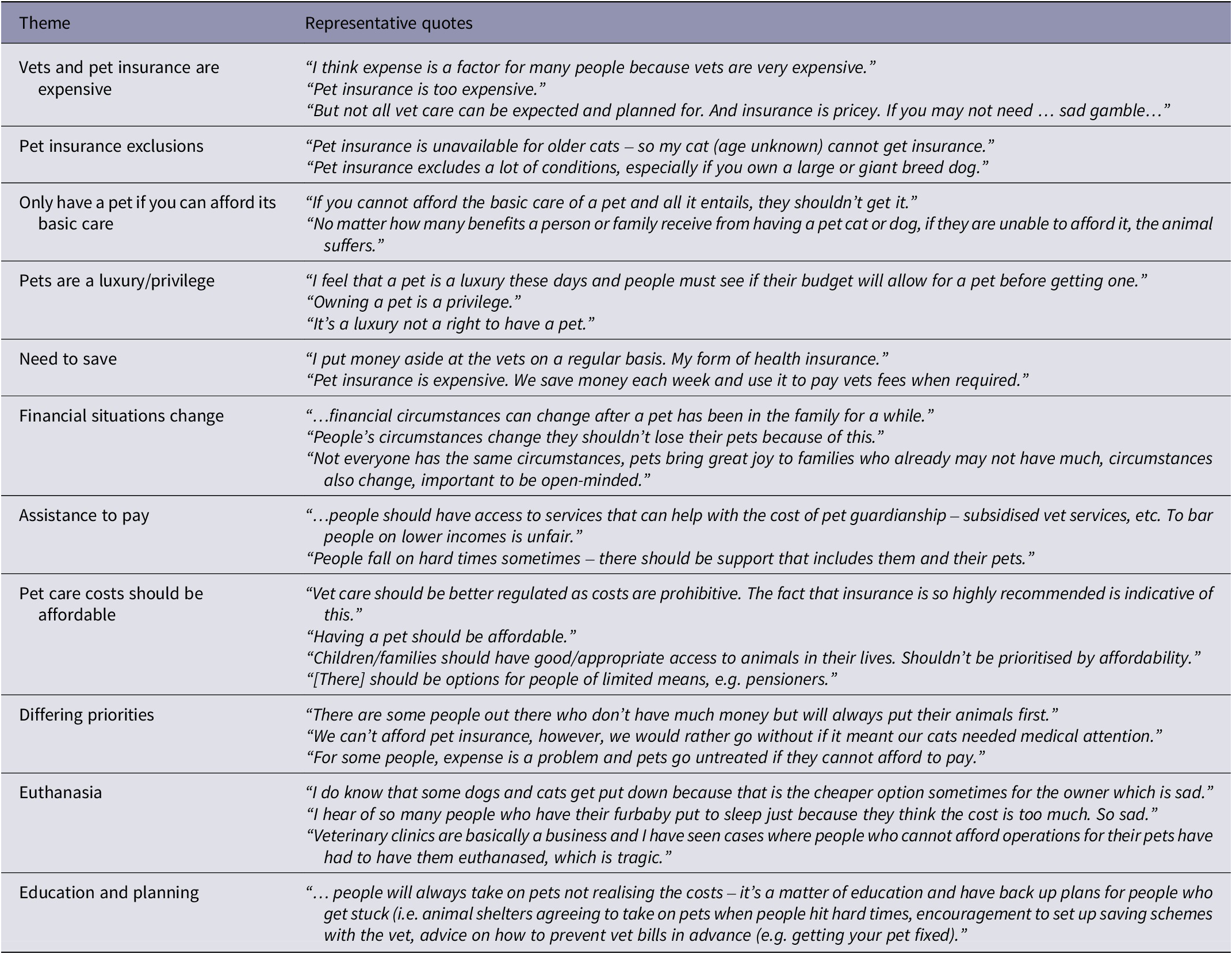

A total of 319 respondents left comments, and several themes emerged (see Table 3). The major themes were that veterinary care and pet insurance are expensive and that pet insurance often has exclusions; that pets should only be owned by those who can afford them and that pets are a luxury and a privilege; that if you own a pet, you need to save for unexpected costs and that sometimes situations change and that there should be financial assistance; that pet care needs to be more affordable; that guardians have differing priorities; that sometimes costs result in pets being euthanased and that education and planning are important.

For the statement ‘Expense is a factor in the level of vet/animal health care that dogs and/or cats receive’, household income level was associated with a higher percentage of those respondents with a household income between NZ$48,000–NZ$70,000 selecting strongly agree (45 versus 33%) and a lower percentage selecting strongly disagree (2 versus 6%) compared to respondents with a household income of over NZ$100,000. A rural upbringing was also associated with the choice selection for this statement, with a higher percentage of respondents who grew up in rural areas agreeing (50 versus 45%) and fewer being neutral (4 versus 7%). Regarding the importance of pet insurance, age range, household income, qualification level, the presence of children in the household, and town or city dwelling were associated with the answer choices. For the age ranges 18–14 and 25–34, a higher percentage strongly agreed (22 and 25%, respectively), and a lower percentage selected neutral (34 and 35%, respectively) compared to all other age ranges up to 75 years (strongly agree range 0–13%; neutral range 49–61%). For household income, those with NZ$14,000–NZ$48,000 and NZ$48,000–NZ$70,000 had a lower percentage of respondents who selected ‘strongly agree’ (both 11%) compared with those with a household income of over NZ$100,000 (19%). A higher percentage of respondents with a level 7 qualification selected ‘strongly agree’ (19%) than those with a level 1 qualification (6%). For respondents with children, a lower percentage strongly agreed or agreed (11 and 19%, respectively, compared to respondents without children, 16 and 23%, respectively), and a higher percentage selected ‘disagree’ (18 versus 13%). The final statement in the finance section was, ‘People should only own a pet if they can afford to keep it.’ A higher percentage of those in the 18–24 and 25–34 age ranges strongly agree (67 and 66%, respectively) compared to those aged 55 to 64 (47%). For household income, those earning between NZ$14,000 and NZ$48,000 had a lower percentage of respondents who selected ‘strongly agree’ (48%) and a higher percentage selecting ‘neutral’ (15%), compared to those with a household income of over NZ$100,000 (63 and 7%, respectively). No other significant associations were observed.

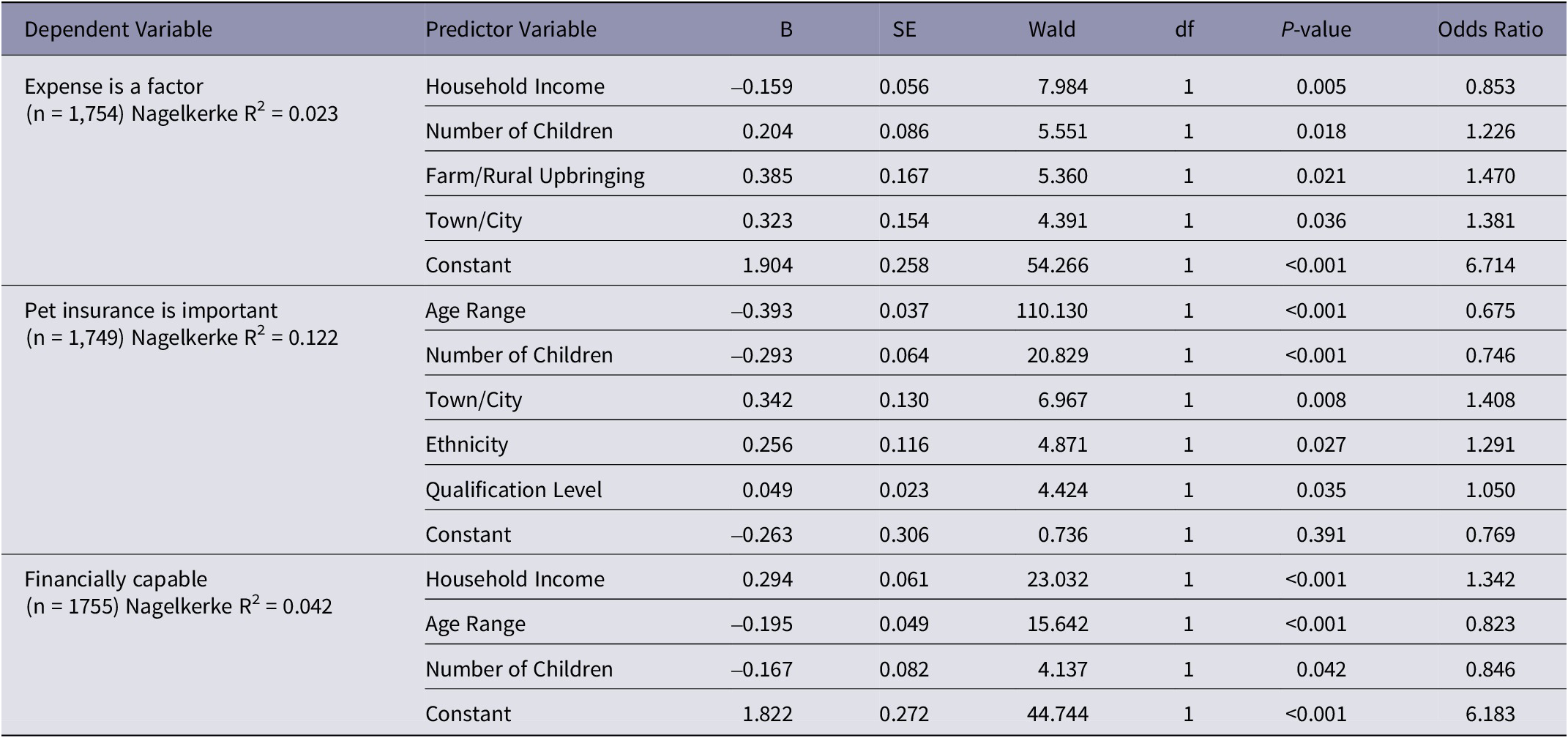

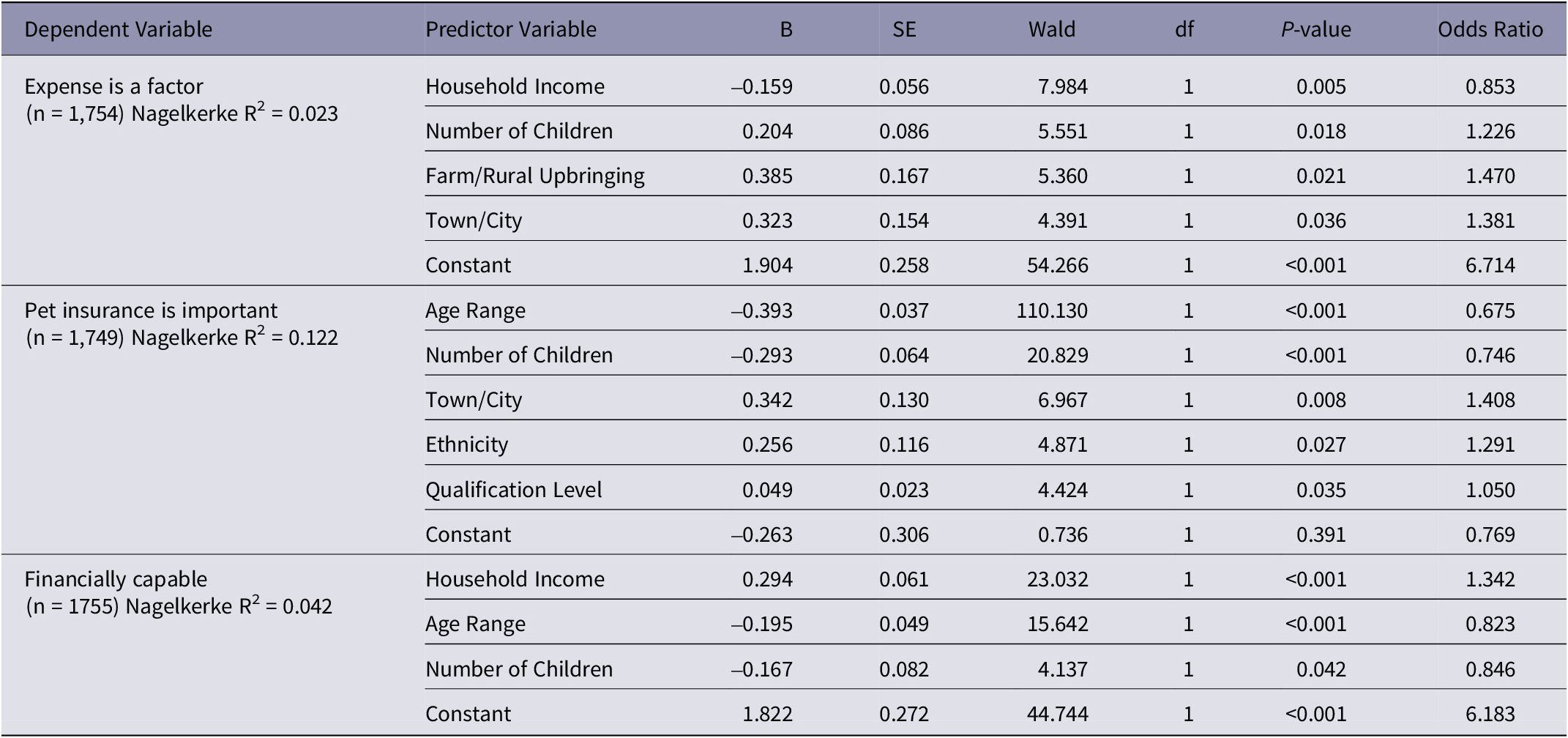

Three binary logistic regression models were developed to identify the demographic factors predicting respondent agreement with the statements on the economics of pet care. The results of the analyses are summarised in Table 2 The final model for expense as a factor in pet care (χ2[4] = 22.983; P < 0.001) explained 2.3% of the variance and correctly classified 85.2% of cases. As shown in Table 2, higher household income was associated with decreased odds of agreeing that expense is a factor in veterinary care. Conversely, having more children, having a rural upbringing, or living in a town/city were all associated with increased odds of agreeing with the statement. The model for pet insurance, being important (χ2[5] = 162.779; P < 0.001) accounted for 12.2% of the variance with an overall classification accuracy of 68.2%. Increasing age and a higher number of children were associated with decreased odds of agreeing that pet insurance is important. In contrast, higher qualification level, identifying with a particular ethnicity (NZ European), and living in a town or city were associated with increased odds of agreement. The final model for only owning a pet if they can afford to be kept (χ2[3] = 37.834; P < 0.001) explained 4.2% of the variance and correctly classified 88.6% of cases. Higher household income was associated with increased odds of agreeing that people should only own a pet if they can afford it. Increasing age and a higher number of children were associated with decreased odds of agreeing with the statement.

Table 2. A summary of the forward stepwise (likelihood ratio) binary logistic regression analyses for 2019 New Zealand Pet Survey

Table 3. Thematic analysis of comments related to some of the financial aspects of providing pet care among 2019 New Zealand Pet Survey respondents

Discussion

The 2019 NZ Pet Survey found that financial constraints significantly impact pet guardianship, with factors such as age, household income, education level, geographic location, and pet insurance contributing to disparities in access to veterinary care. These findings mirror global research showing that cost can act as a barrier to low-income pet guardians accessing veterinary services, particularly preventive treatment (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Wu and Morales2021; King et al. Reference King, Mueller, Dowling-Guyer and McCobb2022). The current survey confirms this concern, highlighting how financial hardship affects not only the care pets receive but also the emotional well-being of their guardians.

Over 83% of respondents indicated that cost influenced the veterinary care their pets received — a concern that has likely intensified in the years since the survey due to worsening economic conditions in Aotearoa NZ, including rising inflation, housing stress, and the broader cost-of-living crisis (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Ren, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Jiang2025). Similar to international studies (Spitznagel et al. Reference Spitznagel, Cox, Jacobson, Albers and Carlson2019; Jatrana & Crampton Reference Jatrana and Crampton2020; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Garrett, Gilles, Houlihan, McCobb, Pailler, Putnam, Scarlett, Treglia, Watson and Wietsma2021; King et al. Reference King, Mueller, Dowling-Guyer and McCobb2022; Muldoon & Williams Reference Muldoon and Williams2024a,Reference Muldoon and Williamsb). These findings emphasise how financial hardship can hinder timely access to veterinary services, leading to poorer outcomes for animals and increased psychological stress for their caregivers.

Notably, rural respondents in the NZ survey were more likely to perceive financial constraints as a major factor influencing veterinary care decisions, suggesting disparities in access and cost structures between rural and urban settings. These findings align with international studies, which show that financial fragility is often worsened by limited geographic access to veterinary services due to the uneven distribution of veterinary staff (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Wu and Morales2021). This highlights the urgent need for improved access to affordable veterinary care, particularly in rural communities.

Delays in treatment and inadequate access to preventive care were commonly associated with financial hardship. Several studies have documented that pet guardians experiencing financial stress may delay routine visits and long-term treatments (Chaumet et al. Reference Chaumet, Rossi, Murphy and Nakamura2021; Forrest et al. Reference Forrest, Awawdeh, Pearson and Waran2023). As a result, these challenges increase emotional stress on pet guardians, who often view their inability to provide adequate care as a personal failure, further compounding their mental health burden (Spitznagel et al. Reference Spitznagel, Cox, Jacobson, Albers and Carlson2019). Several responders reported that unexpected veterinary expenses, such as emergency surgeries, diagnostics, or ongoing management of chronic conditions, were common causes of stress for them. These findings are consistent with international studies showing that financial shock from emergency veterinary bills often leads to delayed care or economic euthanasia (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Williams, Hansen and Coble2020). Furthermore, participants in the current survey reported sacrificing other household necessities to meet pet-related costs, illustrating the broader impact of financial hardship on family well-being.

International solutions, such as financial planning tools, community support programmes, employer-backed pet insurance, and veterinary social work have been explored to alleviate these burdens (Kogan et al. Reference Kogan, Accornero, Gelb and Slater2021; Protopopova Reference Protopopova2021). Educational interventions delivered during routine veterinary appointments may empower guardians to plan for future expenses. More accessible financial strategies — such as care packages or dedicated savings accounts — can provide realistic alternatives to conventional pet insurance. While insurance can offset costs and improve access to advanced care (Springer et al. Reference Springer, Lund, Grimm, Kristensen, Corr and Sandøe2022), it remains a limited solution. Only one-third of respondents considered it essential, noting that premiums are prohibitively high and that many policies exclude common conditions, particularly in older animals and certain breeds. This finding mirrors global trends of low uptake driven by factors such as perceived need, trust in insurers, and high cost (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Goda and McGarry2012; Paul & Skiba Reference Paul and Skiba2012; Chaumet et al. Reference Chaumet, Rossi, Murphy and Nakamura2021). While pet insurance can mitigate financial barriers, its effectiveness is limited by high premiums and exclusions, particularly for older pets or specific breeds (Cunningham Reference Cunningham, Salem and Rowan2007; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Williams, Hansen and Coble2020; Becker et al. Reference Becker, Volk and Kunzmann2022). These findings highlight the need for greater transparency and inclusivity in insurance policies. Future research could explore regulatory strategies to broaden coverage, develop targeted insurance options for vulnerable groups, and improve public understanding of the risks and benefits associated with pet insurance (Chiu et al. Reference Chiu, Li, Lhermie and Cazer2021).

Some guardians described distressing decisions — including euthanasia — not based on medical advice but on affordability. These decisions caused long-lasting emotional impact. Veterinarians also experience moral injury when financial constraints prevent them from providing standard care (Kipperman et al. Reference Kipperman, Kass and Rishniw2017). These findings highlight the need for systemic support, such as ethics training, communication frameworks, and psychological resilience programmes for veterinary professionals. The involvement of veterinary social workers or trained advocates could help guide clients through emotionally charged and financially constrained decisions (Quain et al. Reference Quain, Ward and Mullan2021). This study also highlights broader socioeconomic inequalities. Households earning under NZ$70,000 were significantly more likely to report financial stress and less likely to use pet insurance. These financial challenges were amplified among rural residents, families with children, and those with lower educational attainment. Beyond affordability, logistical barriers, such as limited transportation, clinic availability, and workforce shortages — especially in rural areas — further limit access to care (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Wu and Morales2021; King et al. Reference King, Mueller, Dowling-Guyer and McCobb2022; Muldoon & Williams Reference Muldoon and Williams2024b). These intersecting challenges reveal systemic inequities that call for coordinated, multi-stage interventions. To address these disparities, public funding for essential veterinary services in underserved communities is a necessary step. International examples show that integrating animal welfare into existing social support systems — such as housing, aged care, and family services — can enhance both human and animal outcomes (Fox & Gee Reference Fox and Gee2019; Adams et al. Reference Adams, Applebaum, Eliasson, McDonald and Zsembik2021).

Community-driven, preventive approaches were strongly supported by participants, many of whom recommended subsidised mobile clinics, savings education, and affordable care packages. These ideas mirror successful international initiatives aimed at improving access while reducing reliance upon insurance alone (Kogan et al. Reference Kogan, Accornero, Gelb and Slater2021). Equipping guardians with preventive care knowledge and cost-effective treatment options may increase preparedness and reduce stress. Policy-makers and veterinary associations should collaborate to create a supportive infrastructure to address financial barriers in pet healthcare. This could include tax incentives for veterinary donations, grants for community clinics, and incorporating veterinary services into social welfare assessments. Equally important is supporting veterinarians through training in financial communication, ethical decision-making, and burn-out prevention. Creating a national guideline for the ‘Spectrum of Care’ model would further enable veterinary professionals to tailor treatment options to a guardian’s financial capacity (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Garrett, Gilles, Houlihan, McCobb, Pailler, Putnam, Scarlett, Treglia, Watson and Wietsma2021). This model improves access and supports business morale by legalising the financially constrained care routes.

These recommendations also align with broader social goals. Promoting animal health contributes to the well-being of families and communities, echoing the objectives of SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being). By analysing how income, education, and geography affect access to veterinary care, this research also supports SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) and SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), particularly through its call for more inclusive, pet-friendly policies and urban planning.

Given the scale and complexity of financial challenges, future research should examine the behavioural psychology of pet care, including how pet-related expenses are prioritised in household budgets. Qualitative studies capturing the lived experiences of economically diverse groups — especially Māori and Pasifika communities — are needed to inform culturally appropriate and equitable policy (Forrest et al. Reference Forrest, Awawdeh, Pearson and Waran2023).

In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated these challenges, amplifying the financial strain on pet guardians and highlighting the interconnectedness of human and animal health (Enders-Slegers & Hediger Reference M-J and Hediger2019; Applebaum et al. Reference Applebaum, Tomlinson, Matijczak, McDonald and Zsembik2020; Bibbo et al. Reference Bibbo, Johnson, Drost and Sanders2022; Charmaraman et al. Reference Charmaraman, Kiel, Richer, Gramajo and Mueller2022; Meier & Maurer Reference Meier and Maurer2022). This has highlighted the importance of integrating animal welfare considerations into future public health emergency preparedness and response efforts, as advocated by the One Health Framework (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Applebaum, Eliasson, McDonald and Zsembik2021; Protopopova Reference Protopopova2021). By identifying systemic barriers and proposing integrated solutions, this research contributes to a more equitable and resilient model of companion animal care — one that acknowledges the shared well-being of people and their animals.

Study limitations

While offering insights into the financial aspects of pet guardians, this study acknowledges certain limitations. The voluntary nature of the online survey led to self-selection bias, resulting in a non-representative sample with a disproportionately high number of non-Māori individuals and females compared to the national population. Furthermore, the data were collected in early 2019, over six years ago and before the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the significant economic disruptions caused by the pandemic and the worsening cost-of-living crisis since then, the findings may not fully reflect the current realities faced by NZ pet guardians. However, the findings provide a valuable pre-pandemic baseline for future research on how financial and social conditions have influenced attitudes and practices over time.

Animal welfare implications

Overall, the findings of this study highlight both the direct and indirect impacts of financial constraints on animal welfare and the well-being of their guardians in Aotearoa NZ — impacts that are increasingly relevant in the current economic climate. Since the survey was conducted in 2019, NZ has experienced significant economic challenges, including rising inflation, increased cost of living, and worsening housing affordability. These shifts have likely intensified the financial pressures already reported by participants, further limiting their ability to access preventive care or timely treatment for their animals.

The study suggests that when pet guardians are unable to afford necessary treatment and preventive care, it often results in delays that can lead to worsening health conditions or, in some cases, euthanasia. Additionally, the emotional stress experienced by guardians who are unable to provide appropriate care for their pets can negatively affect their decision-making, further compromising the welfare of the animals in their care. Given the ongoing economic pressures, it is likely that these issues are now even more widespread and urgent than they were in 2019.

Conclusion

The financial aspects of pet guardianship present a complex challenge, impacting both the well-being of the pet and its owner. This study, along with a growing body of global research, highlights the need for comprehensive strategies to promote sustainable and equitable pet guardianship. Policy-makers, veterinary professionals, and animal welfare organisations must collaborate to develop innovative solutions that improve access to affordable veterinary care, enhance financial literacy among pet guardians, and provide support systems for those facing economic hardship. By addressing these challenges, we can foster a world where the human-animal bond thrives, promoting the health and happiness of both pets and their guardians in alignment with the One Health Framework and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the 2019 New Zealand Pet Survey was provided by the New Zealand Companion Animals Trust.

Competing interests

None.