Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a globally prevalent condition, affecting over 280 million people, and is fundamentally characterized by affective disturbances like persistent low mood and anhedonia (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Aravkin, Zheng, Abbafati, Abbas, Abbasi-Kangevari and Borzouei2020; World Health Organization, 2023). There is a strong consensus that these symptoms are tightly linked to two core cognitive dysfunctions: a negative cognitive bias, where attention is preferentially captured by negative information, and impaired cognitive control, the ability to regulate goal-directed thought and behavior (Dotson et al., Reference Dotson, McClintock, Verhaeghen, Kim, Draheim, Syzmkowicz and Wit2020; Villalobos, Pacios, & Vázquez, Reference Villalobos, Pacios and Vázquez2021). Crucially, these two processes do not operate in isolation but interact dynamically, creating a cycle where negative biases disrupt control, and weakened control fails to inhibit negative biases (LeMoult & Gotlib, Reference LeMoult and Gotlib2019). While interventions targeting these mechanisms are effective, the precise neural dynamics of this dysfunctional interaction remain a critical, unanswered question in the pathophysiology of depression (Koster et al., Reference Koster, Hoorelbeke, Onraedt, Owens and Derakshan2017).

The face-word emotional Stroop paradigm is a classic tool for probing this interaction. This paradigm was developed on the basis of the classical Stroop and emotional Stroop tasks, and has been widely used in studies of emotional conflict. It allows for the direct examination of cognitive conflict between emotional stimuli (i.e. emotion–emotion conflict), rather than between emotion and color information as in traditional paradigms. Moreover, it enables the simultaneous investigation of emotional cognitive bias (emotional valence) and cognitive conflict (emotional congruency) as interactive factors within the same task (Etkin, Egner, Peraza, Kandel, & Hirsch, Etkin et al., Reference Etkin, Egner, Peraza, Kandel and Hirsch2006; Joyal et al., Reference Joyal, Wensing, Levasseur-Moreau, Leblond, Sack, A. and Fecteau2019; Strand, Oram, & Hammar, Reference Strand, Oram and Hammar2013). First, individuals with MDD often show generalized cognitive control deficits, reflected in slower reaction times (RTs) and lower accuracy compared to healthy controls (HCs) (Ros Segura et al., Reference Ros Segura, Satorres, Fernández Aguilar, Delhom, López Torres, Latorre Postigo and Meléndez2021; Wang, Xie, Zhang, & Hu, Reference Wang, Xie, Zhang and Hu2021). Second, this deficit is specifically modulated by emotion: individuals with MDD are disproportionately distracted by negative emotional words, whereas HCs can be more affected by positive distractors, confirming a direct behavioral link between emotional bias and cognitive control (Başgöze, Gönül, Baskak, & Gökçay, Reference Başgöze, Gönül, Baskak and Gökçay2015; Joyal et al., Reference Joyal, Wensing, Levasseur-Moreau, Leblond, Sack, A. and Fecteau2019).

Despite this consistent behavioral evidence, the underlying neural mechanisms are poorly understood, with the existing literature defined by a fundamental contradiction. One line of research reports neural hyperactivation in MDD during emotional conflict. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, these studies find increased activation in cognitive control regions like the prefrontal and parietal cortices, while electroencephalogram (EEG) studies show enhanced N2 and N450 event-related potential (ERP) components (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Becker, Huang, Wu, Eickhoff and Chen2018; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Wu, Liu, Yao and Hu2018; Mitterschiffthaler et al., Reference Mitterschiffthaler, Williams, Walsh, Cleare, Donaldson, Scott and Fu2008). This pattern is often interpreted as a compensatory mechanism, where the brain works harder to overcome emotional interference. Conversely, an equally substantial body of research reports neural hypoactivation. These studies document reduced engagement in similar frontal and parietal regions and attenuated ERP components like the N2, suggesting a core deficit in the brain’s capacity to mobilize resources for cognitive control (Chechko et al., Reference Chechko, Augustin, Zvyagintsev, Schneider, Habel and Kellermann2013; Etkin & Schatzberg, Reference Etkin and Schatzberg2011; Li et al., Reference Li, Hao, Zhang, Li and Hu2021).

This contradiction has stalled progress in developing a coherent neurocognitive model of affective disturbance in MDD, limiting our ability to link specific neural dysfunctions to the clinical presentation of the disorder. We propose that these conflicting findings reflect a more complex, time-dependent process that has not been adequately resolved. The limitation of many previous studies is their inability to dissociate the distinct cognitive stages involved in conflict processing (Gao, Yan, & Yuan, Reference Gao, Yan and Yuan2022). High-temporal-resolution EEG is particularly suitable for this purpose, as it allows us to isolate the subprocesses involved in the Stroop task. A recent review of Stroop-related EEG studies proposed a unified neurocognitive model of conflict processing, dividing it into three sequential stages: conflict monitoring, conflict inhibition, and conflict resolution (Heidlmayr, Kihlstedt, & Isel, Reference Heidlmayr, Kihlstedt and Isel2020). The conflict monitoring stage is indexed by the N2 component, a negative-going deflection typically observed over fronto-central regions with a latency of ~200–300 ms. A more negative N250 amplitude under incongruent conditions generally indicates greater cognitive resource allocation for conflict detection (Folstein & Van Petten, Reference Folstein and Van Petten2008; Heidlmayr et al., Reference Heidlmayr, Kihlstedt and Isel2020; Xue, Wang, Kong, & Qiu, Reference Xue, Wang, Kong and Qiu2017). The conflict inhibition stage is reflected by the N450 component, another negative-going waveform distributed over fronto-central areas, with a latency of around 400–500 ms. Larger N450 amplitudes under incongruent conditions are thought to reflect the increased cognitive effort required for the inhibition of conflicting information (Hanslmayr et al., Reference Hanslmayr, Pastötter, Bäuml, Gruber, Wimber and Klimesch2008; Kałamała, Ociepka, & Chuderski, Reference Kałamała, Ociepka and Chuderski2020; Sun & Harmon‐Jones, Reference Sun and Harmon‐Jones2021). The conflict resolution stage is indexed by the late sustained potential (LSP), a centro-parietal positive deflection occurring ~600–800 ms poststimulus, which has been associated with processes of conflict resolution and executive response execution (Heidlmayr et al., Reference Heidlmayr, Kihlstedt and Isel2020; Larson, Clayson, & Clawson, Reference Larson, Clayson and Clawson2014; West, Reference West2004).

Therefore, the present study was designed to resolve this hyper- versus hypoactivation debate. By leveraging the statistical power of a large (N = 276) and well-characterized sample, we aimed to provide a definitive, time-resolved account of emotional conflict processing. We hypothesized that the neural dysfunction in MDD is not uniform, but is stage-specific and context-dependent. Specifically, we predicted that the neural interaction between emotional valence and cognitive control would differ significantly between the MDD and HC groups, and that these group differences would manifest distinctly across the temporal cascade of processing, from initial conflict monitoring (N250) to subsequent conflict inhibition (N450) and resolution (LSP). Furthermore, we posited that the magnitude of these stage-specific neural abnormalities would be directly associated with the clinical severity of depression. By characterizing this dynamic process, this study seeks to provide a more nuanced neurocognitive model that can reconcile previous contradictory findings and clarify precisely when and how the interplay between emotional bias and cognitive control becomes dysfunctional in MDD.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent and were compensated for their time.

Participants

A total of 175 patients with MDD and 101 HCs were recruited. Inclusion criteria for the MDD group were: (1) a primary Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition diagnosis of MDD confirmed via the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I. 7.0.2); (2) a score ≥ 14 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17); and (3) being free of antidepressant medication for ≥14 days (≥28 days for fluoxetine). The inclusion criterion of HAMD-17 ≥ 14 was chosen to capture a broad and clinically representative spectrum of moderate to severe depression, enhancing the generalizability of our findings to real-world patient populations. The HC group had no current or past psychiatric disorders, confirmed by the M.I.N.I. General exclusion criteria for all participants included other major psychiatric or neurological conditions, current substance use disorder, and non-right-handedness.

Stimuli and task design

The task was a face-word emotional Stroop paradigm presented using E-Prime 3.0. Stimuli were happy and sad faces from the NimStim set (Tottenham et al., Reference Tottenham, Tanaka, Leon, McCarry, Nurse, Hare and Nelson2009) overlaid with the Chinese words for “happy” or “sad.” This created four conditions: Congruent-Positive, Incongruent-Positive, Congruent-Negative, and Incongruent-Negative (Figure 1a). As shown in Figure 1b, each trial involved a 1,000 ms fixation, followed by a 1,000 ms stimulus presentation, during which participants judged the facial emotion while ignoring the word. A jittered inter-trial interval of 3,000–5,000 ms followed each response.

Figure 1. Experimental design. (a) The combination of facial expressions and emotional words under various conditions; “Con,” congruent; “Incon,” incongruent; “Pos,” positive; “Neg,” negative. (b) An exemplar trial of the face-word emotional Stroop task.

Behavioral analysis

Mean accuracy and correct-trial RTs were analyzed using a 2 (Group: MDD vs. HC) × 2 (Face valence: Positive vs. Negative) × 2 (Congruency: Congruent vs. Incongruent) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).

EEG acquisition and preprocessing

EEG was recorded from a 64-channel system (Brain Products GmbH) at a sampling rate of 1,000 Hz. Offline processing using EEGLAB included band-pass filtering (0.1–30 Hz), re-referencing to averaged mastoids, epoching (−200 to 1,000 ms), baseline correction, and Independent Component Analysis (ICA)-based artifact rejection.

ERP analysis

Mean amplitudes for three a priori ERP components were extracted: N250 (200–300 ms, fronto-central sites: Fz, Cz, F1, F2, FC1, FC2, C1, C2), N450 (400–500 ms, right fronto-central sites: Fz, Cz, F2, FC2, C2, F4, FC4, C4), and LSP (600–900 ms, centro-parietal sites: Cz, CPz, Pz, C1, C2, CP1, CP2, P1, P2). For each component, the mean amplitude was averaged across all electrodes within the corresponding region of interest and within the specified time window. Amplitudes were analyzed with the same 2 × 2 × 2 ANOVA design. To probe significant interactions, simple effects analyses were conducted. Multiple-comparison correction was not performed in the present analysis, as our analyses focused on predefined time windows and electrode sites based on prior literature.

Brain-behavior and clinical correlation analyses

To test the relationship between neural activity, behavior, and clinical symptoms, we conducted two planned analyses: (1) Pearson correlations between the ERP conflict effects (incongruent minus congruent amplitude) and HAMD scores in the MDD group; and (2) stepwise linear regression analyses using N250, N450, and LSP amplitudes to predict accuracy and RT.

Results

Demographic and behavioral results

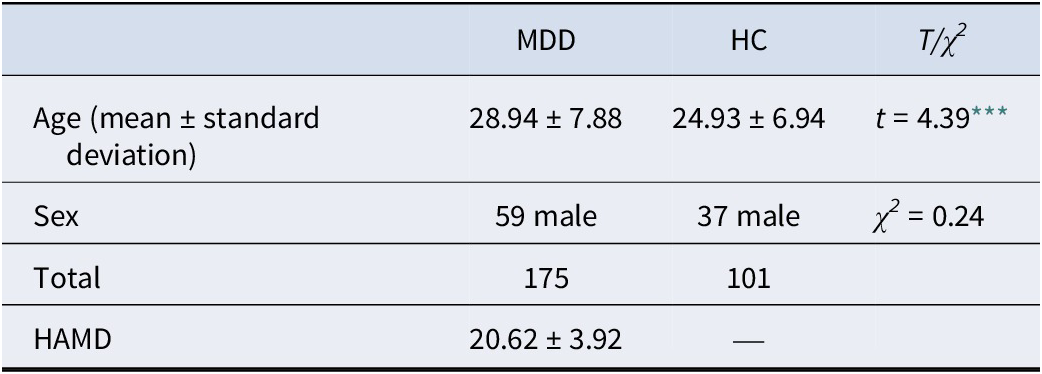

The groups were matched for sex but differed in age (t = 4.39, p < .001; Table 1). To rule out potential age-related confounds, all analyses were repeated in an age-matched subsample. The validation analyses yielded results consistent with the primary findings (see Supplementary Appendix for detailed statistics).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants

Note: HC, healthy control; MDD, major depressive disorder; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

*** p < .001.

Accuracy

Analysis of accuracy revealed significant main effects of valence (F(1, 274) = 16.75, p < .001, η 2ₚ = 0.058) and congruency (F(1, 274) = 160.61, p < .001, η 2ₚ = 0.370). The main effect of group was marginally significant (F(1, 274) = 3.16, p = .077, η2ₚ = 0.011), indicating a trend toward reduced accuracy in the MDD group. Critically, a significant valence × congruency interaction emerged (F(1, 274) = 47.78, p < .001, η 2ₚ = 0.148). As shown in Figure 2, this interaction indicated that the interference effect (lower accuracy on incongruent trials) was significantly larger for positive-face trials (happy face paired with “sad” word) than for negative-face trials.

Figure 2. The results of accuracy and reaction time. “Pos-Con,” positive-congruent; “Pos-Incon,” positive-incongruent; “Neg-Con,” negative-congruent; “Neg-Incon,” negative-incongruent. Error bars indicate 1 standard error. *** p < .001.

RTs

The RT analysis mirrored the accuracy results. There were significant main effects of valence (F(1, 274) = 30.89, p < .001, η 2ₚ = 0.101) and congruency (F(1, 274) = 580.07, p < .001, η 2ₚ = 0.679), but no main effect of group. A significant valence × congruency interaction was also found (F(1, 274) = 52.42, p < .001, η 2ₚ = 0.161). This interaction (Figure 2) again showed that the Stroop interference effect (slower RTs on incongruent trials) was more pronounced for positive-face stimuli compared to negative-face stimuli.

ERP results: a stage-specific neural cascade

N250 (conflict monitoring)

The MDD group exhibited significantly attenuated N250 amplitudes compared to HCs (main effect of group: F(1, 274) = 5.77, p = .017, η 2ₚ = .021). This indicates reduced neural activation during the initial monitoring stage (Figure 3). Further analysis showed a significant main effect of valence (F(1, 274) = 39.19, p < .001, η 2ₚ = .125). Supplementary Figure S3 shows the descriptive statistics of N250.

Figure 3. Grand-average waveforms and statistical results of the N250. (a) The gray rectangle indicates the analysis time window for the N250; “Pos-Con,” positive-congruent; “Pos-Incon,” positive-incongruent; “Neg-Con,” negative-congruent; “Neg-Incon,” negative-incongruent. (b) The main effect of group on N250. Error bars indicate 1 standard error. (c) The main effect of valence on N250. Error bars indicate 1 standard error. HC, healthy control; MDD, major depressive disorder; “Pos,” positive; “Neg,” negative. *** p < .001.

N450 (conflict inhibition)

A significant Group × Valence × Congruency interaction (F (1, 274) = 4.44, p = .036, η 2ₚ = .016) revealed qualitatively different processing strategies (Figure 4; see Supplementary Figure S1 for corresponding topographic plots). The HC group showed a significant valence × congruency interaction (F(1, 100) = 10.01, p = .002, η2ₚ = .092). HCs showed a context-specific conflict response, with larger N450 amplitudes for incongruent trials only under negative-face conditions (F (1, 274) = 13.12, p < .001, η2ₚ = .046). In contrast, the MDD group showed a generalized, nonselective conflict response for both positive (F(1, 274) = 6.11, p = .014, η2ₚ = .022) and negative conditions (F(1, 274) = 8.73, p = .003, η2ₚ = .031). This altered neural pattern was clinically relevant: the magnitude of the N450 conflict effect for positive-face trials (congruent minus incongruent) showed a significant group difference (F(1, 274) = 3.9, p = .049, η2ₚ = .014) and was positively correlated with HAMD scores within the MDD group (r = 0.157, p = 0.038).

Figure 4. Grand-average waveforms and statistical results of the N450. (a) The gray rectangle indicates the analysis time window for the N450. (b) The statistical results of the N450. Error bars indicate 1 standard error. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

LSP (conflict resolution)

The LSP component also revealed group differences (Figure 5), particularly in the processing of negative stimuli. The valence × congruency × group interaction approached significance (F(1, 274) = 3.19, p = .075, η 2ₚ = .011).Simple effects analysis revealed a significant valence × congruency interaction in both HCs (F (1, 100) = 19.94, p < .001, η2ₚ = .166) and MDD group (F(1, 174) = 5.06, p = .026, η2ₚ = .028). Both groups exhibited a significant congruency effect for positive stimuli but not negative stimuli. However, a direct comparison between groups highlighted a specific deficit in the MDD group. As shown in Figure 5 (see Supplementary Figure S1 for corresponding topographic plots), the MDD group exhibited significantly attenuated LSP amplitudes compared to HCs, specifically under negative conditions, both congruent (F(1, 274) = 4.09, p = 0.044, η2ₚ = .015) and incongruent F(1, 274) = 4.09, p = .065, η2ₚ = .012).

Figure 5. Grand-average waveforms and statistical results of the LSP. (a) The gray rectangle indicates the analysis time window for the LSP. (b) The statistical results of the LSP. Error bars indicate 1 standard error. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Validation analyses on an age-matched subsample confirmed all ERP results. The specific statistical results are shown in the Supplementary Appendix.

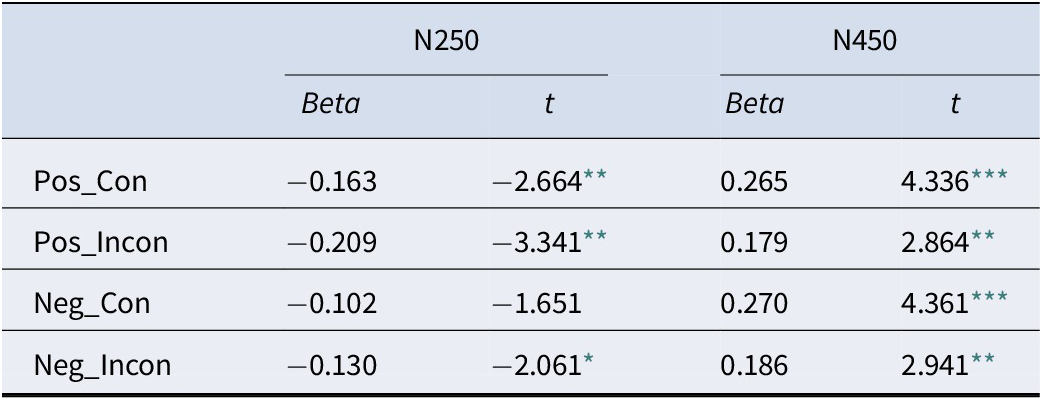

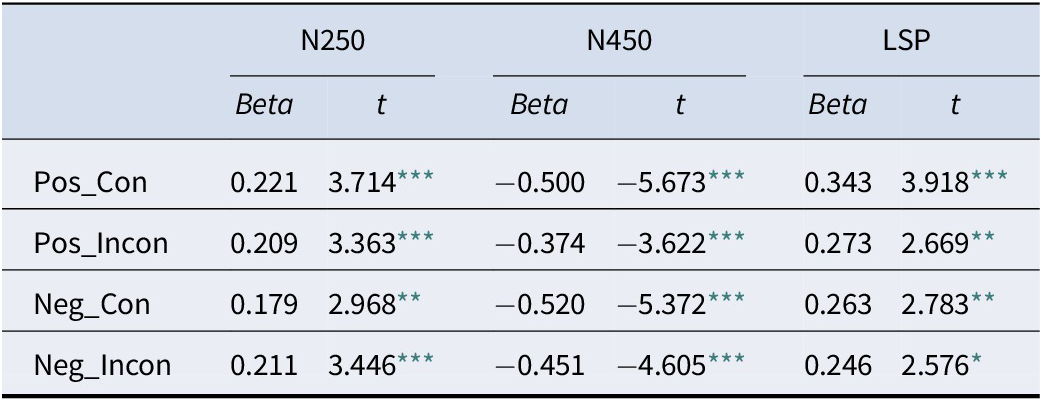

Linking neural activity to behavior

Stepwise regression analyses confirmed that behavior was an integrated outcome of this neural cascade. Accuracy was significantly predicted by the early N250 and N450 (LSP is not significant) components (Table 2), while RT was predicted by the full sequence of N250, N450, and LSP components (Table 3), demonstrating that the entire processing stream contributes to the final behavioral response.

Table 2. The results of linear regression analysis with accuracy as the dependent variable

* p < .05,

** p < .01,

*** p < .001.

Table 3. The results of linear regression analysis with reaction time as the dependent variable

* p < .05,

** p < .01,

*** p < .001.

Discussion

A central challenge in understanding MDD is to explain how emotional biases and cognitive deficits interact to maintain affective symptoms. The present study addresses this by providing a time-resolved neural account of this process, revealing that individuals with MDD engage a distinct and inefficient cascade of neurocognitive operations during emotional conflict. We demonstrate that while individuals with MDD may achieve comparable behavioral performance in emotional conflict tasks, their underlying neural processes are markedly different and inefficient. Our findings delineate a clear, stage-specific cascade of neurocognitive dysfunction – an initial processing deficit (hypoactivation), followed by compensatory effort (hyperactivation), and finally, impaired late-stage resolution (hypoactivation). This temporally resolved model offers a unifying framework that reconciles longstanding discrepancies in the literature.

In the present study, only a marginally significant group difference in accuracy was observed between the MDD and HC groups, and overall behavioral group differences were not significant. While some previous studies have reported similar findings (Chechko et al., Reference Chechko, Augustin, Zvyagintsev, Schneider, Habel and Kellermann2013; Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Chase, Greenberg, Etkin, Almeida, Stiffler and Phillips2017; Strand et al., Reference Strand, Oram and Hammar2013), others have documented clearer behavioral impairments in MDD (Alders et al., Reference Alders, Davis, MacQueen, Strother, Hassel and Zamyadi2019; Broomfield et al., Reference Broomfield, Davies, MacMahon, Ali and Cross2007; Gupta & Kar, Reference Gupta and Kar2012; Ros Segura et al., Reference Ros Segura, Satorres, Fernández Aguilar, Delhom, López Torres, Latorre Postigo and Meléndez2021; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xie, Zhang and Hu2021; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Wang, Kong and Qiu2017). A possible explanation concerns differences in sample characteristics. Many earlier studies recruited highly typical MDD samples using stricter inclusion criteria and smaller sample sizes, such as HAMD ≥19 (Başgöze et al., Reference Başgöze, Gönül, Baskak and Gökçay2015; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Wang, Kong and Qiu2017). Although this approach facilitates the detection of typical MDD-related deficits, the strong heterogeneity of MDD (Marx et al., Reference Marx, Penninx, Solmi, Furukawa, Firth, Carvalho and Berk2023; Rhee et al., Reference Rhee, Wilkinson, Steffens, Rosenheck and Olfson2020) may amplify cognitive impairments or highlight patterns specific to severely depressed individuals, thereby limiting generalizability. In contrast, the present study employed a HAMD ≥14 criterion, which included participants with relatively milder symptoms while strictly controlling for medication use. This sampling strategy improved the representativeness of the MDD group, although it may have contributed to the absence of significant behavioral group differences, further underscoring the complexity of MDD and the necessity of examining its cognitive-neural correlates. In addition, our task design differed from several previous studies: the distractor stimuli were fixed emotional words (“happy” and “sad”), and the targets were socially relevant emotional faces. Compared with paradigms that use a wider variety of emotional words as targets (Ovaysikia, Tahir, Chan, & DeSouza, Reference Ovaysikia, Tahir, Chan and DeSouza2011; Ros Segura et al., Reference Ros Segura, Satorres, Fernández Aguilar, Delhom, López Torres, Latorre Postigo and Meléndez2021), this design likely imposed a lower cognitive load, which could have reduced the detectability of behavioral group differences.

Early-stage hypoactivation

Early-stage group differences emerged in the context of emotional conflict processing. Compared to HCs, individuals with MDD exhibited significantly attenuated N250 amplitudes. This finding may reflect two distinct neurocognitive mechanisms. First, the N250 has been implicated in conflict monitoring (Heidlmayr et al., Reference Heidlmayr, Kihlstedt and Isel2020), and reduced amplitudes in MDD may indicate impaired recruitment of monitoring resources during early cognitive control (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Wang, Shen, Zeng, Yang, Kuang and Li2023; Li et al., Reference Li, Hao, Zhang, Li and Hu2021). This interpretation is supported by further regression analyses showing that N250 amplitudes significantly predicted both accuracy and RT, with coefficient directions aligning with theoretical expectations. Alternatively, prior research on facial affect processing suggests that the N250 also indexes early-stage decoding of emotional facial cues (Streit et al., Reference Streit, Ioannides, Liu, Wölwer, Dammers, Gross and Müller-Gärtner1999, Reference Streit, Wölwer, Brinkmeyer, Ihl and Gaebel2000, Reference Streit, Ioannides, Sinnemann, Wölwer, Dammers, Zilles and Gaebel2001). From this perspective, the blunted N250 in MDD may reflect deficits in facial emotion recognition (Labuschagne, Croft, Phan, & Nathan, Reference Labuschagne, Croft, Phan and Nathan2010; Wynn et al., Reference Wynn, Jahshan, Altshuler, Glahn and Green2013). Taken together, these results indicate that MDD is associated with insufficient neural engagement during the early phases of emotional conflict. Clinically, this may manifest as a reduced initial “alarm signal” for emotionally salient events, providing a potential neural basis for the emotional blunting and apathy reported by some patients.

Compensatory hyperactivation of the conflict effect under positive conditions

During the conflict inhibition stage, the initial deficit was followed by a qualitatively distinct regulatory shift, as indexed by the N450 component. Rather than reflecting a mere quantitative difference in interference magnitude (Broomfield et al., Reference Broomfield, Davies, MacMahon, Ali and Cross2007; Gupta & Kar, Reference Gupta and Kar2012; Joyal et al., Reference Joyal, Wensing, Levasseur-Moreau, Leblond, Sack, A. and Fecteau2019), a significant three-way interaction was observed. HCs showed a context-sensitive increase in neural engagement, with enhanced N450 amplitudes selectively elicited by incongruent trials involving negative facial expressions, but not positive ones – suggesting flexible allocation of cognitive control resources. In contrast, individuals with MDD exhibited a generalized, nonselective pattern of inhibitory activation, characterized by robust N450 conflict effects across both emotional valences. Notably, the largest N450 amplitudes emerged in positive-face/negative-word pairings, indicating maximal neural engagement when incongruent negative distractors interfered with positive targets. This pattern may reflect compensatory hyperactivation in MDD for tasks, shaped by the interplay of affective bias and cognitive conflict (Başgöze et al., Reference Başgöze, Gönül, Baskak and Gökçay2015; Joyal et al., Reference Joyal, Wensing, Levasseur-Moreau, Leblond, Sack, A. and Fecteau2019; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Wang, Kong and Qiu2017). The most pronounced difference between the MDD and HC groups in the N450 component was that the conflict effect under the positive-face condition was significantly larger in MDD compared with HCs. To probe the clinical relevance of this effect, Pearson correlation analyses revealed that the N450 conflict effect (incongruent minus congruent) under positive-face trials was significantly positively associated with HAMD scores in the MDD group, indicating that greater inhibitory effort in response to positive emotional conflict (negative distraction stimulus) tracked with symptom severity. Further regression analyses showed that N450 amplitudes significantly predicted both accuracy and RT, with coefficients consistent with theoretical expectations (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Lynn, Huc, Fogel, Knott and Jaworska2022). Together, these findings suggest that MDD is marked by compensatory overactivation during emotional conflict inhibition, particularly under positive-incongruent conditions.

Hypoactivation during conflict resolution

At the conflict resolution and response execution stage – indexed by the LSP component (Di Russo & Bianco, Reference Di Russo and Bianco2023; Heidlmayr et al., Reference Heidlmayr, Kihlstedt and Isel2020) – individuals with MDD exhibited significantly reduced neural activity when processing negative facial expressions. This attenuated LSP amplitude likely reflects an impaired capacity to disengage cognitive resources from emotionally negative content (De Raedt & Koster, Reference De Raedt and Koster2010; Gotlib & Joormann, Reference Gotlib and Joormann2010; West, Reference West2003). Given that the LSP typically emerges between 600 and 900 ms poststimulus, a window that closely aligns with behavioral RTs, its reduction is functionally relevant. Regression analyses further demonstrated a significant negative association between LSP amplitude and RT, indicating that lower LSP amplitudes predicted slower responses. This neural-behavioral coupling provides converging evidence that MDD is characterized by deficient late-stage conflict resolution and response execution under negative emotional conditions. This neural signature provides a powerful, moment-to-moment analogue for the clinical phenomenon of rumination, where patients report being unable to “get out” of a negative headspace.

Theoretical contributions and clinical relevance

A key contribution of the present findings is their potential to reconcile the ongoing debate regarding neural hyper- versus hypoactivation in MDD. Our results demonstrate that this is a binary distinction but a matter of temporal dynamics. Depression is characterized by both hypoactivation – during early-stage conflict monitoring (N250) and late-stage resolution (LSP) – and compensatory hyperactivation during the intermediate stage of conflict inhibition (N450). This stage-specific model provides a cohesive account of prior inconsistencies in the literature (e.g. Feng et al., Reference Feng, Becker, Huang, Wu, Eickhoff and Chen2018; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Wu, Liu, Yao and Hu2018; Li et al., Reference Li, Hao, Zhang, Li and Hu2021) and may serve as a bridge between conflicting neural models of depression.

Currently, there is no unified consensus on how emotional cognitive bias and cognitive control are related in MDD (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Yan and Yuan2022). Some studies suggest that these two processes operate in parallel (Everaert, Grahek, & Koster, Reference Everaert, Grahek and Koster2017; LeMoult & Gotlib, Reference LeMoult and Gotlib2019), whereas others propose a significant interactive relationship between them (Joormann & Quinn, Reference Joormann and Quinn2014; Villalobos et al., Reference Villalobos, Pacios and Vázquez2021). Our results show that during emotional conflict processing, both HC and MDD participants exhibited effects of emotional cognitive bias in the early conflict detection stage. At the conflict inhibition stage, HCs demonstrated an interaction between emotional bias and cognitive control, whereas the MDD group showed a parallel processing pattern of these two functions. In the conflict resolution stage, both groups displayed a similar interactive pattern between emotional bias and cognitive control. Taken together, our findings suggest that the two theoretical perspectives – parallel versus interactive – may both be valid but emerge at different cognitive stages. In MDD, the interaction between emotional cognitive bias and cognitive control appears only at the later conflict resolution stage, rather than during earlier inhibition processes. This delayed interplay may reflect impaired emotional regulation in MDD, which could contribute to symptoms such as rumination and negative interpretive bias (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Yan and Yuan2022; Villalobos et al., Reference Villalobos, Pacios and Vázquez2021).

Beyond reconciling theoretical models, our findings have significant clinical implications. First, the distinct N450 interaction pattern observed in the MDD group could serve as a potential biomarker for objectively assessing cognitive control deficits, which could aid in patient stratification or tracking treatment response. Second, the identification of a specific late-stage disengagement deficit (LSP) provides a strong neurophysiological rationale for the mechanisms of established treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based interventions, which explicitly train patients to disengage attention from maladaptive negative thoughts. This work thus bridges the gap between basic neuroscience and clinical application, pointing toward more targeted and measurable therapeutic strategies.

Limitations and future work

Several limitations should be noted. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, and although controlled for, subtle effects of age or prior medication history cannot be fully excluded. Future longitudinal research is needed to track these neural markers across illness progression and in response to treatment.

Conclusions

In summary, this study provides compelling evidence that individuals with MDD process emotional conflict through a distinct and inefficient cascade of neural events. By demonstrating stage-specific patterns of hypo- and hyperactivation, our findings advance a more nuanced neurocognitive model of depression, identifying specific, time-sensitive neural processes that could serve as targets for future diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291726103171.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation and gratitude to all the participants in this study.

Author contribution

All authors contributed substantially to this work. Dong Li, Z. Z., and K. L. performed analysis, made interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. Dan Li, R. L., J. Z., and Y. F. made contributions to the acquisition of data for the work. Z. Y. and G. W. helped draft the work and revise it critically. All authors made significant contributions to the paper to assess the important intellectual content, read, and approved the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding statement

This work was supported by STI2030-Major Projects (2021ZD0200600); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82471576);The Beijing Research Ward Excellence Program (grant number BRWEP2024W072120106); Beijing High-Level Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talent Support Program-Dengfeng Project (G202512066); Research Fund from Beijing Anding Hospital (YG202302).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.