In December 2017, Carl-Ludwig Thiele, at the time a member of the German central bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) executive board, wrote an article for the online publication of the World Gold Council (WGC) Gold Investor, entitled “Transparency – At Least as Valuable as Gold.”Footnote 1 The article focuses on policy changes and public relations moves undertaken by the Bundesbank in response to fears among the public that German gold was at risk by being stored outside the country or even that it was “not really there.” One such response to these types of public concern was the transfer of 674 tonnes of gold from vaults in London and New York to Frankfurt. He outlines four “steps to increasing transparency”: the disclosure of the amount of gold in the bank’s possession and of the transfer of gold from Paris and New York to Frankfurt, the commissioning of a film to document the transfer, and the publication of “all German gold bars, totalling around 270,000 in number” (Thiele Reference Thiele2017). The year after this article was published, to mark the completion of the gold transfer program, the Bundesbank also produced a striking coffee-table book, Germany’s Gold.

In framing these changes in this way, the article links the gold transfer program to broader trends toward “transparency” within gold markets. These transparency projects have expanded tremendously in the last three decades as a particular iteration of “audit culture” (Power Reference Power1994; Strathern Reference Strathern2000). In this chapter, I consider how transparency and gold are established and maintained as “global values” and how actors differently positioned within gold markets seek to align them, with greater and lesser degrees of success. I trace how this happens in three clusters of transparency projects: certification schemes and voluntary frameworks for mining companies; efforts to use blockchain technologies to increase transparency in the supply chain; and efforts to verify (and perform the verification of) gold’s presence in European central banks, especially the Deutsche Bundesbank. Exploring these specific sites where transparency and gold convene, both supporting and tugging against each other, illuminates a critical moment in gold’s history and also allows us to consider transparency from an angle that, unlike many other discussions, does not only operate “within the limits of the very ideology of the phenomenon under examination” (Ballestero Reference Ballestero2012a: 161). In particular, I view gold and transparency as engaged in competitive processes of value-making (and unmaking).

As part of this volume’s attention to “the comparative establishment of the position of transparency in a broader system [or systems] of value” (see the Introduction), this chapter assesses transparency as a global value in relation to the seemingly more self-evident (perhaps, or perhaps not) global value of gold. This approach must first take account of the dynamic and processual nature of transparency as a value – and, indeed, of value (or, more precisely, value-making) itself. Elsewhere (Ferry Reference Ferry2013) I have argued for seeing value-making as a two-part process, consisting both of “making meaningful difference” and also, critically, of “making difference meaningful.” By this last phrase, I mean the often messy process through which it is established that it is worth distinguishing between two or more given values. One can say that one bar of gold is finer (has a higher percentage of gold) than another, or that one policy for informing the public about central bank holdings is more transparent than another, and that can be taken as an important and relevant comparison. And this comparison can be the subject of contention or consensus.

However, for there to be any point to that comparison, at least some people must recognize that it is worth making distinctions between gold and transparency. The historical, political nature of this aspect of value often escapes notice, and yet it is arguably the site of most politics around value. We can frame the emergence of transparency in the past few decades in these terms, as the relative stabilization of value-making acts such that transparency becomes something for which differences are meaningful – that is, something valuable.

Indeed, this is what efforts at ethical marketing aim to do: to establish some chosen characteristic as worth making distinctions between – organic or shade-grown coffee, Malagasy vanilla, conflict-free diamonds (Bell Reference Bell2017; Osterhoudt Reference Osterhoudt2017; Roseberry Reference Roseberry1996).Footnote 2 Getting people to buy these ethical products is one kind of value-making act (and each successful or uncontested value-making act helps to make the next one more successful), but so are actions such as the establishment of metrics and certification systems, press conferences, or, as in this case, alignment with another value that seems to be secure or uncontested. Hence the headline “transparency – at least as valuable as gold” or the familiar phrase that something is “worth its weight in gold” (even when that something is not a tangible, weighable object, as in the case of transparency). In these phrases, gold is taken as the stable and self-evident form of value. and whatever is being aligned with it is claimed as also (like gold) worth making distinctions between.

But wait. It appears from the title of the Gold Investor article (which is, as you may be able to tell, aimed primarily at investors in gold) that transparency is the thing that needs to be argued for, whose value must be shored up by reference to the self-evident value of gold. But in a broader context, gold as a global value is not as stable as you might think. Thiele is arguing for the value of transparency to the immediate audience of gold investors (who are likely to be among gold’s staunchest allies, one may presume), but on a broader scale the article and the actions it describes can be read as an attempt to shore up gold’s shaky status as a global value by linking it to transparency.

A Brief and Imperfect History of Gold as Global Value

In order to understand what is happening with gold now, we need some sense of how it has been established as valuable, especially in European and Euro-descended contexts.Footnote 3 For centuries, gold has been viewed as a substance with distinctive and impressive material semiotic force (Green Reference Green2007; Maurer Reference Maurer2005; Vilar Reference Vilar and White2011) that is linked to value and sovereignty and thus to market and state (Hart Reference Hart1986). In particular, gold’s close association with money is both a consequence and a driver of its tremendous cultural power over the course of many centuries. During these centuries, gold functioned primarily as a method for large payments and as a reserve currency (with silver and copper much more commonly in circulation), as well as a means of adornment and of the display of power and transcendence (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2012).

While Britain moved to a single gold standard in the early nineteenth century, most other countries operated on either a silver or a bimetallic standard. Only after 1870, because of Britain’s dominance as an industrial and financial power, did most European and American countries, and others outside these zones, move to a gold standard (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2019: chapter 2). The gold standard as an international system lasted until 1931 (barring an interruption from World War I to the mid 1920s) (Green Reference Green2007), though not without continual adjustments and coordinated action between countries to maintain its efficacy in times of crisis. The system depended on an “overriding commitment on the part of central banks to external convertibility” (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2019: 32) and was ultimately challenged by the rise of fractional reserve banking, since this form of banking depends on a central bank as backstop or “lender of last resort,” leading to a structural tension between external convertibility and domestic financial stability.

Obviously critical to gold’s value, and equally obviously beyond the capacity of this chapter to capture adequately, are gold’s uses as a sign of power, luxury, and transcendence. From the gold halos of saints in Byzantine art, to the crowns on the crowned heads of Europe, to John Donne’s lines in “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,”

to the gold plates of aristocracies, to the gold toilet on display at the Guggenheim museum (titled America), to the Yellow Brick Road leading to the Emerald City where trickery and illusion reign (Graeber Reference Graeber2011: 53), to the gold-induced madness in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre – we could go on and on – gold signifies a bewildering range of things: power, transcendence, truth, falsity, idolatry, shit, and so on. Many of these meanings come from (or are perceived as coming from) its material qualities of malleability, mass, luster, nobility (non-reactivity), and color. And these ways in which gold acts as a global value endure, even as its value as a reserve currency has been displaced.

Gold’s status as reserve currency came to an end over the course of the twentieth century, first in the 1930s and again in 1971 when Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of gold with the dollar at a rate of $35 per ounce. As we will see below, although much of the world’s gold is still held in central banks (especially in the US, Germany, UK, France, and China), it no longer plays any significant functional role in national economies,Footnote 4 although it may serve to project confidence and security (as Thiele suggests in his article).

In the years following this decoupling of gold and the dollar (and therefore much of the world’s money supply), gold’s price rose precipitously, culminating in the early 1980s at a price of $850 per ounce (London Fix Price).Footnote 5 The price then declined through the 1980s and was driven yet further down when the Bank of England sold off over half its reserves (395 tonnes) (Ash Reference Ash2019). This began to reverse as the prices for commodities in general, and gold in particular, rose in the early 2000s. Gold reached a nominal high of just over $1,900 per ounce in 2011 (when adjusted for inflation, the high at the beginning of 1980 is still the historical high in real terms).Footnote 6 For several years after this, gold’s price wandered in the range of $1,100–$1,300 per ounce, in many cases close to the cost of production. In the summer of 2019, gold rose again above $1,500 and above $1,800 during the Covid pandemic, invasion of Ukraine, and rising inflation. This is in part because of gold’s generally accepted value as a barometer for fears of instability and crisis,Footnote 7 and the fact that its price tends to move independently of other important asset classes such as the US dollar and the stock market (Baur and Lucey Reference Baur and Lucey2010). As of this writing, in September 2024, gold reached a historical (nominal) high at $2,580 per ounce, with the 400-ounce gold bar topping $1 million in August 2024 (Maruf Reference Maruf2024).

Notwithstanding these recent high prices, gold-mining companies since the 2000s have faced a series of ups and downs. The dramatic Bre-X hoax concerning an alleged gold mine in Indonesia brought lots of unwanted publicity to the ill-regulated field of “junior mining” and what one interlocutor described as a “nuclear winter” in mining investment (Tsing Reference Tsing2000). A few years later, high metals prices spurred exploration and production in many brown- and greenfield sites, building on existing or newly exploited facilities, as well as artisanal and small-scale mining in Latin America, Africa, Australia, and Papua New Guinea; these in turn have sparked conflicts both explosive and grinding (Kirsch Reference Kirsch2014; Li Reference Li2015; Luning Reference Luning2012; Rosen Reference Rosen2020). These years have increased public awareness of the links between gold mining and armed conflict, and the severe environmental damage caused by both “informal” small-scale mining and large-scale mining, especially open-pit mining (Verbrugge and Geenen Reference Verbrugge and Geenen2020). Calls for further controls, transparency, and ethical practices in the gold sector have grown more and more insistent.

Gold faces opposition in financial circles as well. Because it is listed as a commodity, many institutional investors (such as pension funds) cannot invest in it. Many financial professionals dislike it as an investment because in its physical form it gives little to no return and in other forms (as mining equities or exchange-traded funds) it can be risky and its price movements complex and difficult to understand. One interlocutor, when asked why many financial advisers don’t like to invest in gold, licked his finger and held it up as if testing the direction of the wind, and said, “It’s too hard to interpret.” Its cultural and affective associations as outdated and fetishized (“idolized” or “worshipped,” as my interlocutors would tend to describe it) and the vocal presence of “gold bugs”Footnote 8 (called by one of my interlocutors “the tinfoil hat crowd,” in reference to the farcical Facebook attempt to pit conservative news commentator and gold bug Glenn Beck against a poodle in a tinfoil hat) make it seem kooky and cranky to some investors, and organizations such as the WCG spend time distinguishing their perspective on gold from these more extreme positions and seeking to burnish gold’s reputation as a sensible, rational investment.

Of course, gold is still recognized widely as a valuable asset and it still commands cultural force the world over. Its price is high and demand for gold in China, India, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East booms; and, as the recent prices attests, it continues to work as a safe-haven asset in times of uncertainty, and to respond to changes in interest rates. Technologies for investing in gold (such as exchange-traded funded and asset tokenization) continue to be invented. Nevertheless, gold’s age as a global currency is over, and its integrity as a stable nexus of value-making practices has been fraying for some time. Moreover, its associations with money laundering and arms trading and the environmental damage caused by mercury use, large-scale open-pit mining, and unregulated small-scale mining have placed the industry on the back foot, causing some actors and institutions to mobilize transparency as a strategy to “clean up” the industry and “burnish” its reputation.

Transparency talk can be found throughout gold extraction, circulation and, investment these days; this chapter centers especially on the invention of technologies to render the supply chain more transparent, the mobilization of blockchain technology (discursive and material) in these technologies, and, drawing on the topic of the Gold Investor article with which I began, efforts by central banks to project simultaneously transparency and security with respect to their gold reserve holdings.

Transparency’s Trajectory

Transparency technologies have been defined by Andrea Ballestero in the introduction to a 2012 Political and Legal Anthropology Review special issue on the topic as “a political and legal device … intended to correct the democratic deficits of existing forms of law, bureaucracy, and even subjectivity” (Reference Ballestero2012a: 160). They aim to infuse institutions with rationality, fairness, and accountability, and are generally contrasted with opacity, secrecy, conspiracy, and corruption.

The story of transparency’s journey to prominence and proliferation as a global value can be told in several different ways: as, for instance, a descendant of glasnost (the term describing movements toward “openness” within Soviet institutions during the Gorbachev period) promoted by NGOs (especially environmental ones) in the former Soviet republics (Zakharchenko Reference Zakharchenko2009). In this context, transparency projects are positioned as part of the movement for “democratization” and against “corruption.” The organization Transparency International, which was founded in 1993, has developed a ranking system to measure governmental corruption, an early use of metrics.

The language of transparency also became enfolded into emerging audit culture in the 1990s (Power Reference Power1994; Shore and Wright Reference Shore and Wright1999; Strathern Reference Strathern2000), both as a normative discourse and as a set of tools and institutions. For instance, in 1999, Shore and Wright, in speaking of the particular iterations of audit culture within British higher education, wrote: “Foremost in the new semantic cluster associated with audit culture are ‘transparency’, ‘accountability’, ‘quality’ and ‘performance’, all of which are said to be encouraged and enhanced by audit” (Reference Shore and Wright1999: 566). In this sense, the language of transparency provides the discursive infrastructure for audit culture in its various iterations. In addition to these semantic uses of the language of transparency, technologies of transparency have emerged in multiple areas. These include systems of certification that attest to the ethical sourcing of commodities; the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative standard, to which national government can sign up to improve transparency surrounding revenues from oil, gas, and mining; and chain of custody protocols and infrastructures – including, as we will see, digital technologies like blockchain. This chapter attends briefly to the ways in which a language of transparency is deployed (as, for instance, by Thiele, in the article discussed above) in order to help establish the gold market as ethical and ethics as a meaningful component of the gold market, and then moves to a discussion of several technologies of transparency in supply chains and in the verification of gold in central bank vaults.

Transparency’s trajectory has brought it to the realms of gold mining, refining, transport, and finance. In recent years, the hidden aspects of gold’s expressions as a global value (its presence and location in vaults, the London Fix Price, the OTC marketFootnote 9 in London, its use in arms dealing and narcotrafficking) have come under increasing scrutiny. Within these contexts, transparency emerges as both the idiom through which those who insist on knowing more about how gold moves through the world operate, and also the procedures and infrastructures by which those who are invested (literally and figuratively) in gold seek to defend themselves. These actors use transparency to combat “political risk,” to broaden markets for gold through “ethical marketing” techniques and pronouncements, and to sidestep governmental regulation; at a broader level, they seek to shore up its status as a global value. The article by Carl-Ludwig Thiele and the “steps to increasing transparency” it describes reflect one example among many of these attempts to use transparency to shore up gold, even as the article also uses gold to ratify transparency. In what follows, I briefly discuss three sites where processes of transparency intersect with gold, paying particular attention to how both are made and unmade as global values through these intersections.Footnote 10

Supply Chains

One such site, with an accompanying set of technologies for creating transparency, is the gold supply chain from mine to refinery to market. These technologies include certification schemes – that is, methods by which consumers can learn the path that gold has taken from the mine, and through which different origins for gold are (putatively) “certified.” Many of these are collected in the OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance (OECD 2016). They can been used to ascertain (ideally) that the gold is “conflict-free” – that is, not sourced in areas that are “identified by the presence of armed conflict, widespread violence, including violence generated by criminal networks, or other risks of serious and widespread harm to people” (OECD 2016: 66) These systems occur at all points in the supply chain, though many are concentrated at the refinery or “choke point” stage, and refineries are now compelled by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) to follow its “responsible sourcing guidelines” as a condition for inclusion in the Good Delivery List (a list of accredited refineries, previously focused only on questions of gold purity and security).Footnote 11 In the words of Matthieu Bolay:

Through the idioms of transparency and responsibility, such initiatives [guidance frameworks, certification systems, and other technologies for ensuring that gold extraction and circulation follow ethical norms] pretend – although selectively – to render visible and legible the social life of gold and the networks that brought it into being prior to its legitimate and licit status as a commodity or financial asset.

Not surprisingly, gold supply chain certification programs range widely in their restrictiveness and are also frequently criticized either for being too utopian or as corporate “greenwashing.” This is, of course, a localized version of arguments that are common throughout the domains of ethical supply chains, fair trade, corporate social responsibility, and business and finance more generally (Falls Reference Falls2011; Kirsch Reference Kirsch2014; Rajak Reference Rajak2011; Reichman Reference Reichman2011; Tripathy Reference Tripathy2017; West Reference West2010). As in these other cases, there is a fundamental instability at the heart of these endeavors; as soon as a particular certification garners the support of corporations, it tends to alienate many activists, more or less by definition. Put in the terms I have been using in this chapter, the challenge of certification lies in the tension over whether values of transparency (and related concepts of ethics and accountability) and gold (as something produced and promoted by global corporations) are opposed or aligned.

Over the past eight or so years, the position of mining companies and member associations such as the WGC and the LBMA has shifted dramatically toward supporting certification and, at least nominally, greater transparency in general. To a significant but difficult to measure degree, their response has been provoked by the emergence and strengthening of guidance frameworks for responsible gold production such as the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) and Earthworks’ “Golden Rules” (part of its “No Dirty Gold” campaign), which tend to operate outside the industry or, in the case of IRMA, with only a few relatively small mining corporations participating.

Greater attention to responsible mining has been evident through the course of my research, including at the two LBMA conferences I have been able to attend. At the LBMA conference in 2014, there was a post-conference “Responsible Gold Forum” co-sponsored by the LBMA and the Responsible Jewelry Council, which lasted about two hours. Since many attendees were either leaving for the airport or socializing with colleagues, it was only sparsely attended. In one session, presenters were immediately put on the defensive by a member of the audience who complained that the acronyms and jargon of the proposed certification process were too hard to remember.

In 2018, one of the eight sessions and a keynote speech in the main conference were devoted to ethical concerns and transparency. In the panel session, entitled “Gold Bar Integrity Up the Supply Chain,” the deputy director of the NGO Enough Project, which works primarily in Congo, spoke to a robust audience about supply chain transparency to ensure conflict-free precious metals. Later, an executive of the WGC remarked to me that inviting a member of an NGO of this type (i.e., independent of a corporation or member organization) would have been unthinkable a few years before.

Within the industry, reasons given for the benefits of greater transparency are pragmatic as well as ethical, at least once one leaves behind the realms of websites and presentation slides. Van Bockstael argues:

[M]any current initiatives that are being supported by key players in the mining industry are promoting a host of principles dedicated to sustainability, but can also be seen as a way of insulating the “responsible” members of the mining industry from those who, by omission, are less so and who could, in the future, be responsible for the next environmental disaster due to mismanagement, or provide the spark for the next big activist campaign due to links with unsavoury regimes or atrocities.

Here, we can see a strategy of calculated display, not only as an act of compliance and ethical consideration, but also as a shield to protect other, more enclaved and opaque processes that may not be so ethically oriented.

Since these two conferences, the WGC, the member organization for the majority of the world’s medium and large gold-mining companies, has worked to produce information and strategies to bring transparency and related “responsible” practices to the gold market. In 2019, the WGC launched the Responsible Gold Mining Principles (RGMP), a framework of principles and guidance for its member companies with respect to mining and the supply chain.

Terry Heymann, chief financial officer for the WGC, who also oversaw the development of the RGMP, describes the framework in the publication Climate Action as “an overarching framework which sets out clear expectations to investors, consumers and downstream users as to what constitutes responsible gold mining” (Cooper Reference Cooper2020). The RGMP sets out ten principles, divided into “Governance,” “Social,” and “Environmental” (following the now canonical division within ethical/responsible business and finance). Issues related to transparency of supply chains, impact, and revenue are covered primarily in the first three and the tenth principles.

The RGMP comes with several supporting tools, including an “assurance framework” to help with implementation and oversight and a benchmark comparing the RGMP and the framework from the International Council on Mining and Metals (also a member organization, but for metals-mining companies more generally, not only gold-mining companies).

These “frameworks,” “guidances,” and “benchmarks” seek to perform a hortatory function and to set out a common set of standards for what responsible gold mining would look like. These are necessary technologies for building transparency or other forms of ethical practice, but they do not get into the specific details of how these can be met.Footnote 12

The WGC website states that “Conformance to the RGMP is a requirement for membership in the World Gold Council”Footnote 13 and the principles have achieved broad-based support as a metric used by companies to demonstrate their compliance with its goals, and maybe also to work toward greater compliance.

Blockchain

One rapidly emerging area for handling the details has been blockchain technology. The 2018 LBMA conference featured a slew of companies touting blockchain technology in a whole slew of applications, but especially to guarantee a transparent and clean “chain of custody” from mine to refinery. This guarantee is crucial to most precious metal certification schemes, and since refineries often bear the brunt of costs of certification, there is a strong interest in increasing trustworthiness and lowering costs at that stage of the journey (Bolay Reference Bolay2021).

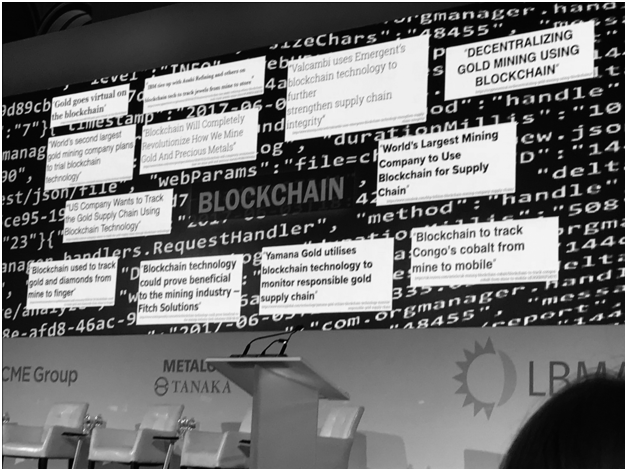

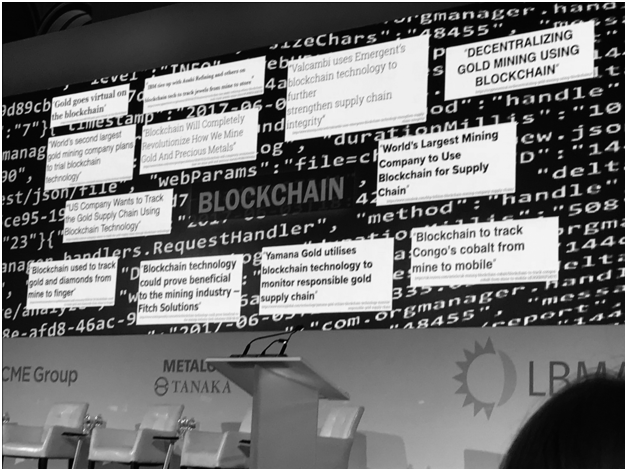

Blockchain technology purports to provide this by means of a digital, distributed ledger that supposedly cannot be hacked. At the 2018 LBMA conference, as I mentioned above, there were numerous vendors advertising blockchain technology, as well as a keynote speaker and panel participant presenting on the possibilities of using the technology for greater transparency. A presentation by Sakhila Mirza, General Counsel for the LBMA, on “Gold Market Integrity” discussed at length the capacity of “technology” to create transparency while also ensuring the continued capacity for discretion in the highly specialized and secretive gold OTC market. Her presentation concluded with a call for proposals on how best to meet the requirements without exposing market participants too much (how to negotiate the divide between secrecy and display). Figure 7.1 is a slide in her presentation demonstrating how much blockchain technology is expected to be part of this solution.

Figure 7.1. A presentation slide from the LBMA meeting, 2018.

In fact, using blockchain technology to bring transparency to the gold supply chain isn’t so easy to do, especially along the lines of the “private” or “proprietary” solutions I saw advertised at LBMA. Filipe Calvão notes this contradiction, saying: “The notion of centralized or permissioned database locations, which is to say, who controls access and dissemination of data, is … at odds with the principles of distributed accountability” (Calvão Reference Calvão2019: 129). One financial technology expert with whom I spoke, who had been invited to the LBMA 2018 conference, confirmed this point, saying:

A lot of what I saw [in the vendor booths] was based on a misguided understanding of what blockchain is. As long as it’s private you are just using an expensive database. You can’t put gold in a blockchain and think you’re putting transparency in the supply chain. You can’t truly put something on the blockchain, you’re just using the system as a pointer.

That is, you can record bars of gold in a database structured by blockchain technology, but there will be points of weakness in the system – who logs it in, how the bar is labeled or identified – so the very reason why you would use blockchain in the first place is lost.

Acknowledging this need for “human appreciations at the entry point” of digitized information on gold into the blockchain, Bolay (Reference Bolay2021: 97) also foregrounds other ways in which the technology creates new kinds of actors, networks, and possibilities, including the simultaneous storage of digitized information concerning gold’s movement through the chain of custody and the process of creating digital slices of gold as a transferable asset, or of the ethical inscriptions linked to it (as, for instance, conflict-free gold) through the process known as “tokenization.” Asset tokenization is a current trend in financial technology or “fintech” that has opened new possibilities for rendering gold as a physical object divisible and liquid through creating a “digital double” (Bolay Reference Bolay2021: 99) on a blockchain.Footnote 14

In an article in the journal Political Geography, Filipe Calvão and Matthew Archer (Reference Calvão and Archer2021) examine the ways in which blockchain technologies have proliferated in mining industries, arguing that these modes of creating, managing, and owning data by digital means are “parallel but … increasingly inextricable from the material extraction of minerals, developed under the banner of blockchain-based due diligence practices, chain of custody certifications, and various transparency mechanisms” (2). Like my interlocutor, they also note that, “in contrast to public blockchains like Bitcoin, these are primarily private blockchains that operate as permission-based centralized ledgers” (3). Not only do these “expensive databases” not provide the transparency and accountability they promise, Calvão and Archer show that they also carve out new channels by which value can be extracted from commodity chains, often in highly opaque and unaccountable ways.

In the past few years, it seems some of the buzz over blockchain as a technology for bringing transparency to gold supply chains has diminished (as we see with other “use cases” for blockchain), partly because the challenges and costs of implementing it at scale have become more evident. A November 2023 article in the environmental journalism magazine Mongabay outlines these challenges and costs in Brazil, noting that “blockchain shouldn’t be viewed as a panacea to an industry rife with social and environmental risks” (Espinosa and Lyons Reference Espinosa and Lyons2023).

Central Bank Vaults

As I have introduced above, transparency projects have also been coalescing around the verified presence of gold in (especially European) central bank vaults. And these, too, show us the process by which vying values of gold and transparency can at times be brought into (uneasy) alignment and at times work to undermine each other. For one thing, a dynamic by which transparency projects are made publicly visible – the ways in which they are performed – happens in all domains where transparency operates but intersects with gold in particular ways. For one thing, gold as a global value manifests, and arguably depends on, an oscillation between display and secrecy, at times flashing out spectacularly and at other times hidden away in vaults, graves, or hoards. This aspect of gold has been noted by several anthropologists, including Maurice Godelier (Reference Godelier1999) in his use of gold to demonstrate the “enigma of the gift,” which he sees as a dialectic between keeping and giving away (see also Weiner Reference Weiner1992), and Gustav Peebles, for whom gold operates as a key example in his re-theorization of “the hoard” as a fundamental principle of banking (Peebles Reference Peebles2014; see also Ferry Reference Ferry2020).

In an article in the journal Cultural Geographies, Erica Schoenberger draws on diverse archaeological and ethnohistorical sources to show how gold’s scarcity has been enhanced at certain moments through artificial restriction of its supply. Among other sites, Schoenberger points particularly to the necropolis of Varna in what is now Bulgaria, which dates to the fifth millennium BCE, in which large quantities of gold were sequestered in what she describes as “self-cancelling supply” (Schoenberger Reference Schoenberger2011: 7). That is, by burying gold, Varna’s chiefs simultaneously demonstrated their power and removed gold from circulation. While Schoenberger’s emphasis falls on the notion of socially constructed scarcity, the material she presents also suggests a counterpoint between display and removal from display. The golden objects associated with royalty are frequently displayed on ceremonial occasions such as coronations and weddings, but are then removed from display by being buried and placed in vaults away from public view. The process of “self-cancelling supply” described by Schoenberger can also be seen as a process of revealing and removing from view.

Schoenberger concludes her discussion by noting how the pattern of sequestering gold by burying it in tombs continues into the twentieth century with the practices of holding gold reserves in central banks. She writes, “From the graves of Varna to the underground vaults of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the history of the social value of gold is in part a history of different ways of creating artificial scarcity” (Schoenberger Reference Schoenberger2011: 19).

For one thing, between 1999 and 2019, many central banks signed a collective agreement restricting how much they could sell, in recognition of the potential to destabilize the gold price by flooding the market (as happened in the late 1990s). The WGC described this predicament and the agreements that have been developed to manage it thus:

Collectively, at the end of 2018, central banks held around 33,200 tonnes of gold, which is approximately one-fifth of all the gold ever mined. Moreover, these holdings are highly concentrated in the advanced economies of Western Europe and North America, a legacy of the days of the gold standard. This means that central banks have immense pricing power in the gold markets.

In recognition of this, major European central banks signed the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) in 1999, limiting the amount of gold that signatories can collectively sell in any one year. There have since been three further agreements, in 2004, 2009 and 2014.Footnote 15

This need to restrict the circulation of gold, at least periodically, overlapped with gold’s dual role as object of visual display and invisible hoard (Graeber Reference Graeber1996).

In September 2019, the CBGA was allowed to lapse, so banks no longer participate in this voluntary agreement to limit sales on the grounds that the market in gold had grown and matured since the 1990s and that banks had “no plans to sell.” The rationale that the CBGA is no longer needed is based largely on the idea that central banks continue to hold and buy gold, suggesting that the function of self-canceling supply continues to operate, even after the agreement has ended.Footnote 16

Strikingly, central banks – and central bankers – find themselves in a complicated position with respect to the gold reserves they hold. Because of the shift in gold’s position in the global economy since the end of dollar–gold convertibility in 1971 (as discussed above), the importance of gold as a national asset has inarguably declined, although observers differ by how much. Those who are more attached to the idea that gold has intrinsic value and who mistrust the very concept of “fiat money,” not surprisingly, feel that stewardship of gold reserves remains a critical task for central banks. Others – perhaps including many central bankers – are agnostic about or skeptical of the sound money thesis but recognize gold’s cultural and symbolic force, which make it a telling barometer for global crisis or instability.Footnote 17

Indeed, most central bankers, arguably, see the management of the money supply as a far more important dimension of their job.Footnote 18 As one interlocutor, former chair of a European central bank (though not one with large gold reserves), told me, “When I talk with other [central] bankers, we find gold a bit of a nuisance. We wish we could get rid of it.” Nevertheless, central bankers must, at least nominally, respond to the public pressure to keep the gold they have. In addition, central banker must be extremely careful about any information or publicity connected to their gold holdings. Public statements concerning gold in central banks tend toward “managed transparency,” including carefully timed press releases, public statements, and photographs demonstrating their careful stewardship of the nation’s gold supply.

The Deutsche Bundesbank gives a good example: in the face of (mostly right-wing) pressure to move the gold holdings housed in New York and Paris back to Frankfurt, framed in terms of a lack of transparency and a sense that perhaps the gold “wasn’t really there,” the bank instituted a transfer (called by some outside the bank a “repatriation”), which was completed in late 2017.

The many interviews, articles, press conferences, and other media artifacts (including the Gold Investor article), and the book and museum exhibition that accompanied its completion, can be seen from several angles: as full-throated celebrations of gold; as demonstrations of the bank’s “increased [though necessarily limited] transparency”; and as protections against the potential liabilities of gold as a kind of anti-value (as Van Bockstael argues above). These public performances of gold’s presence and the transparent actions that allow the gold to “shine forth” draw on powerful ideas about materiality (including qualities like mass and shine) and value as tied to white male and European bodies. Figure 7.2, an image included in an article on the Bundesbank website announcing the completed transfer of Germany’s gold from New York in 2016 (the transfer from London was completed in 2017), brings together a lustrous gold bar and some kind of testing or logging tool (which also looks a bit like a jeweler’s loupe, suggesting that its purpose is to “see” the gold either literally or figuratively) with the date of the bar and the word “Switzerland” (where the most trusted refineries are concentrated). In this image, transparency, accountability, gold, whiteness, and maleness converge in a coordinated act of making value.

Figure 7.2. Gold bars at a press conference, Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017.

Transparency infuses gold with value in each of the three areas I have described, but with different histories and different effects. As I suggested above, the frameworks for responsible and ethical supply chains fall within a broader range of attempts to establish ethical value chains for many different commodities and can be seen as and analyzed in terms of pressures from nongovernmental organizations, activist groups, and consumers concerned with environmental and social justice. Blockchain technologies are mobilized to meet these ends but also participate in other conversations with other concerns, such as freedom from governmental interference and the “transparency” of distributed ledgers, as well as the increased liquidity of digital assets, with the promise of a more “transparent” field for investment in gold. The transparency work done by central bankers is oriented somewhat differently, toward finding new solutions to a perennial problem they face – how to perform gold’s “real” presence in their vaults while also keeping it secure. These varied audiences and aims sometimes align, but not always. By viewing them next to each other, I hope to have highlighted the ways in which transparency and gold converge and vie against each other as global values.

Gold’s fortunes in mining and finance are up in the air these days. In mining, gold faces what companies and investors call “political” or “reputational” risk, narrow profit margins (especially as new technologies of transparency become more necessary), and impatient investors. In finance, actors vie to shore up its place as a globally recognized and trusted asset, or to relegate it firmly to a humbler place, according to its relatively restricted use values in jewelry and technologies, and as one among any number of commodities on which to build derivative contracts (futures, options, etc.). In these stormy seas, languages and techniques of transparency are conscripted to right gold’s ship, and, in doing so, to solidify transparency itself. As in other exercises in imperfect commensuration, gold and transparency both align and grind gears; in doing so, as David Graeber has written, they “bring universes into being” (Reference Graeber2013).