‘The research of Ararat is borne out, though not completely, by this catalogue. In its turn, the show is a free adaptation of the indications shown in the catalogue.’Footnote 1 The statement, demonstrating a keen awareness of the non-correspondence between the performance and the record, appears in the exergue of the presentational volume published for the inaugural performance of the Armenian intermedial project Ararat. The spectacle took place on 9, 12, 13 and 15 March 1977 at the church of San Maurizio at the Major Monastery in Milan. Ararat materialized through a meticulously crafted catalogue that includes highlights from the performance and commentary on its aesthetics, displaying a high degree of graphic subtlety.

Edited by the Milanese publishing house Scheiwiller, the artefact transcends the standard programme booklet. Due to its length of over 100 pages and dimensions of twenty by twenty-four centimetres, the catalogue deviates from conventional formats, rendering it atypical in physicality, scope and design. It includes complete scores by composer Ludwig Bazil, the original Armenian poems that he set to music with Italian and English translations, and nearly forty drawings by painter Herman Vahramian. It features essays by prominent intellectuals from the Milanese cultural milieu of the 1970s as well. Theatre reviewer Ugo Ronfani offers a critical overview of the avant-garde endeavour while ethnomusicologist Michele Straniero analyses the selected poetic texts, noting how the performance’s media interactions underscore their broader significance. Art critic Vanni Scheiwiller highlights Vahramian’s abstract, music-inspired language. Musicologist Khachi Khachik examines Bazil’s efforts to innovate while remaining rooted in the Armenian classical music school. Together, the authors underscore the event’s multifaceted nature, situating it at the intersection of the arts.Footnote 2

Ararat stands as an ambitious and complex project, forging an Armenian avant-garde production deeply grounded in intermediality. Milan-based artist Vahramian and co-creator Bazil staged a total-art event featuring music, poetry and paintings. The performance’s core consisted of fifteen musical pieces encompassing string quartets, arias for soprano and bass, an a cappella composition for choir, and a flute solo piece. The lyrical content of the vocal parts derived from Armenian poems spanning diverse periods, including odes by the medieval theologian Gregory of Narek (951–1003), the troubadour from the eighteenth century Sayat Nova (1712–95), and victims of the Armenian genocide such as the composer Komitas Vardapet (1869–1935) and the poets Siamanto (1878–1915) and Daniel Varujan (1884–1915). Throughout the musical performance, a video projector reproduced scenes of Armenian archeological sites, photographs of miniatures and khatchkars (literally ‘crosses of stone’, the typical memorial monuments of medieval Armenia), a collection of black-and-white non-figurative pictures sketched by Vahramian, and renowned paintings of the Western artistic avant-garde by Vasilij Kandinskij, Paul Klee and Marc Chagall.Footnote 3

As the exergue suggests, the catalogue’s contents aim to elicit the aesthetic and artistic explorations of the performance rather than capture it. By exploring its role as an archival remnant, I argue that the Ararat catalogue should be regarded as an integral component of the performance rather than a mere paratext.Footnote 4 It functions as an evocative remnant which aligns with, but does not fully encapsulate, the intermedial presentation, requiring the exploration of the volume’s peculiar metonymic involvement – its proximities to and displacement from the avant-garde event. Specifically, I investigate how the diasporic urban context reinforces the catalogue’s affective impacts by strengthening its mnemonic role, making it a crucial reference for constructing a historiography of Armenian performances. Central to my research is the notion of metonymy as a historiographical tool, essential for dispersed and marginalized histories such as that of the Armenian diaspora in Milan. The catalogue, as metonymy, supports the narrative of the Milanese-Armenian community through associative connections between material remnants and performance. By examining the catalogue through the lens of metonymy, we gain insights into how diasporic communities use performative objects to navigate their cultural and historical accounts. As a process defining one object through a shift to another contiguous or closely associated with it, metonymy involves the evocation by fragments – such as performance artefacts – of broader cultural wholes. In diasporic contexts, where post-traumatic legacies often shape collective memory, these fragments acquire an enhanced affective charge, enabling the reconstruction of disrupted narratives.Footnote 5

Ararat has been largely overlooked in the historiography of Milanese-Armenian cultural productions.Footnote 6 The intermedial approach reflected an effort to develop a pioneering artistic and performative practice within a minoritarian community. Therefore the limited scholarship on Ararat has tended to interpret the event as an isolated, unique episode rather than a potential turning point for Armenian performances. Recognizing that, in theatre and performance studies, ‘historiography ultimately consists of stories told by archival objects, images, texts’, I address this gap by building on the interconnection between text and performance and the temporal afterlife of ephemerality.Footnote 7 Particularly, I delve into metonymy as part of an ongoing conversation within performance studies about the conflict between the fleeting nature of events and their documentation. Crucially, both the Ararat performance and its catalogue offer a compelling vision of a still-evolving and highly contested debate about the relationship between archival remains and performative disappearance. I aim to reframe the performance remnant as an archiving tool appointed ‘to reimagine the writing of history [engaging] with subjects whose existence would have been unremarkable’ in dominant narratives.Footnote 8 The same counterhegemonic account significantly affected the attitude of the diasporic artists involved in Ararat.

The interaction between the Ararat performance and its catalogue offers a relevant contribution to the ongoing discussion regarding the tensions between archival and performative logics, exemplified by Diana Taylor’s definition of the archive as textual ‘objects’ and of the repertoire as ‘embodied acts’.Footnote 9 Rather than remaining distinct, according to Taylor, the domains mutually intersect, as they ‘constantly interact in many forms of again-ness’.Footnote 10 Further complicating their relationship, the Ararat catalogue serves as an archival repository that simultaneously enacts the event’s posterity, thereby promoting embodied memory. The interplay blurs the boundaries between the archive and the repertoire, positioning the artefact as a site where fragments both document and prolong the narratives of the performance through the lens of metonymy. According to Peggy Phelan’s insights on performance ontology, metonymy illustrates how the event’s disappearing nature affects its material relics. Performance varies from the metaphorical rhetoric of similarity. Due to the impossibility of reproduction, it works within the domain of metonymy, embracing strategies of ‘displacement’, where remnants suggest connections to the performance without fully encapsulating it.Footnote 11 Tracing performative remains beyond archival evidence, Rebecca Schneider expands on the idea that performance only vanishes when approached through archival logics that prioritize reproducibility and permanence.Footnote 12 Linking the notion of metonymy to the intersection between archive and performance, I explore how the Ararat catalogue navigates the porous boundaries between archives and ephemerality, thus framing metonymy as a key tool for contributing to the historiography of Milanese-Armenian cultural productions. Particularly, metonymy offers a deeper insight into the mnemonic practices of the Armenian community in Milan, as it performs the afterlives of event remnants, both to sustain internal, often neglected, histories and to reach potential allies within the broader urban audience.

The Ararat catalogue functions as a significant vantage point for examining the interplay between the archive as a historiographical resource of a transnationally marginalized diasporic community and performance as a transient site of identity negotiation. The catalogue, as a record imbued with historiographical connotations, critically embodies Sara Ahmed’s concept of ‘sticky’ materiality. According to Ahmed, stickiness manifests as an investment making items ‘saturated with affect, as sites of personal and social tension’.Footnote 13 While Ahmed emphasizes how emotions and objects can delineate boundaries and exclusions within the community, I focus here on the potential, connective aspects of emotionally charged artefacts within the Armenian diaspora. As I will elaborate, within Armenian communities, the volume’s affective power derives from its sacred-like qualities. The Ararat catalogue’s materiality endures as a shared locus of gathering and resilience, anchoring the community’s politics of belonging across temporal thresholds. Strikingly, the catalogue involves the durational and non-linear timeline that, according to Schneider, characterizes performance remains. Schneider critiques archival logic as a colonial and patriarchal mechanism of hegemonic record-keeping. However, I argue that by shifting her focus to diasporic frameworks, the archive can instead assist the Ararat catalogue in functioning ‘as both the act of remaining and a means of re-appearance and “reparticipation”’, activating embodied memory through metonymy.Footnote 14 Additionally, the fleeting aspects of metonymy as a memory facilitator parallel José Esteban Muñoz’s assertion that ‘ephemera is a mode of proofing and producing arguments often worked by minoritarian culture’, highlighting the necessity of expanding beyond conventional archives to encompass the elusive dimensions of historiography.Footnote 15 While focused on queer identities, Muñoz’s insights extend to material ephemera as cultural practices of resistance across broader contexts of otherness. In this light, the Ararat catalogue merges archival role and ephemeral trace to perform the afterlives of the Milanese-Armenian community’s marginalized narratives.

This study examines the archiving methods used to create the Ararat catalogue, revealing how distinctive, document-based practices within Armenian diasporas contribute to historiographical self-enactments for the community. My analysis focuses on the artefact’s content, layout and outreach to uncover its metonymic values and its role as a performing archive that narrates the event.

The catalogue as metonymy

The Ararat catalogue’s layout and contents highlight how the volume establishes itself as a metonymy of the performance. The artefact presents all the musical texts composed by Bazil in their entirety, while the black-and-white sketches by Vahramian function as a graphic link among scores, poetic verses and presentational captions. At times, the pictorial symbols cover entire pages; at other times, they occupy half a page alongside the musical scores (Figs. 1–2). The arrangement of the scores also varies, spanning two consecutive sheets or appearing as a single musical line on an otherwise blank page (Figs. 3–4). Through this intricate graphic interrelation and layout, the design exemplifies the convergence of arts involved in the performance, thereby highlighting the intermedial nature of the avant-garde project. The artistic integration adopted in the material record thus aligns with the concepts that Vahramian and Bazil sought to illuminate. Nonetheless, the transition from the three-dimensionality of the live event to the two-dimensionality of printed material results in a challenging editorial structure. The catalogue, while rich in its artistic design, can only juxtapose music and paintings rather than fully capturing their reciprocal interactions. These features underscore the distinction between multimedia and intermedia. As Chiel Kattenbelt notes, the former ‘refers to the occurrence where there are many media in one and the same object’, while the latter ‘refers to the co-relation of media in the sense of mutual influences between media’.Footnote 16 While the catalogue integrates various media within a single artefact, it primarily operates through a proximate predisposition towards multimedia. This approach focuses more on presenting diverse media in conjunction, rather than exploring the deeper, interconnected interplay characteristic of intermedia.

Fig. 1 Vahramian’s black-and-white abstract illustrations serve as the primary illustrative feature of the Ararat catalogue. The sketches draw inspiration from both musical gestures and the Persian alphabet.

Fig. 2 The catalogue frequently presents a multimedia juxtaposition of paintings and musical scores. The depicted musical piece is the composition for string quartet Ani, performed during the show along with all the other compositions included in the volume.

Fig. 3 Poems appear alongside their associated musical pieces, although the scores remain the primary graphic element on the sheet. The musical setting of the medieval poem Meghedi Narekatsi by Gregory of Narek was composed for bass voice and string quartet.

Fig. 4 The layout often emphasizes blank spaces, containing only small fragments of the musical parts. In this instance, the featured musical extract comes from the composition for string quartet Vardavarin.

For the same reason, another crucial aspect of the performance – its reliance on abstract language – finds only partial fulfilment.Footnote 17 Non-figurative expression is immediately evident in Vahramian’s painting.Footnote 18 In his essay from the catalogue, Khachik emphasizes a similar foundation in Bazil’s music. He notes that ‘the abstraction of tradition by means of harmonic components and suitable techniques led to a reproduction of the original idea deeply-rooted in the Armenian musical tradition’.Footnote 19 Thus the musicologist identifies the composer’s strength in seamlessly integrating and innovating within Armenia’s classical music repertoire a quality that unfolds through the musical enactment. However, the scores featured in the catalogue, while essential, do not fully capture the essence of the musical work as performed. This issue has increasingly become a significant driving force in the historiography of musical performance. Building on the assumption that ‘performance is a better starting point than a musical score for testing theories of many musical behaviors’,Footnote 20 modern musicology asserts that ‘[t]he experience of live or recorded performance is a primary form of music’s existence, not just the reflection of a notated text’.Footnote 21 Serving primarily as a guide for the performers, the scores cannot independently convey Bazil’s abstractive inclination. Nevertheless, the fact that the catalogue includes them integrally reveals a commitment to documenting as much as possible the most ethereal components of the event, such as music. Hence, similar to the musical texts, the artefact reinforces its role as a mnemonic device not by claiming to fully represent the performance, but by functioning as a relic of the performance itself.

Memory is inherently incomplete, as the exergue of the catalogue states. The metonymic consciousness of this assertion connects to the fragmentary reflection that the volume establishes in relation to Ararat as a performance. Not only do the elements documented in the catalogue fail to reproduce the event itself; they also implicate an additional form of disappearance. The remnant encompasses omissions, errors and inaccuracies. The Ararat catalogue addresses what is left unsaid and unintended, drawing an implicit connection to the underrepresented or missing histories of Armenian diasporic performances.Footnote 22

The most evident gap arises from the unacknowledged musical scores performed during the show, particularly the flute composition. In addition to the string and vocal parts, Bazil composed an instrumental piece for flute, incorporated into the performance by exploiting the peculiar architectural design of the church of San Maurizio. Until the late eighteenth century, the building served as a cloistered monastery for Benedictine nuns. This historical context shaped the internal configuration with a double-spaced layout intended to separate different groups of attendants. The devotees occupied the courtroom at the entrance, while the nuns prayed and sang in the exclusive chamber behind the altar. The seizure of Milan by Napoleon and the subsequent secularization process initiated by the pro-French Cisalpine Republic led to the suppression of the convent in 1798. Following this event, a narrow aisle was opened beside the apse to connect the Public Room and the Nuns’ Room, establishing both an architectural and an allegorical link between the communal and the secret.Footnote 23 In Ararat, the organizers leveraged the double-space suggestion by initially placing the spectators in the Public Room, where the flautist Cecilia Vallini performed an instrumental introduction.Footnote 24 This preamble served as a ritual initiation into the upcoming performance. Upon concluding her solo, Vallini guided the audience from the Public Room to the Nuns’ Room, where the total-art event continued with video projections.Footnote 25 Notably, the catalogue does not document this proxemic dynamic, despite all reviews of Ararat focusing on and praising the enchanting and initiatory live experience.Footnote 26 Given the considerable interest the flute performance generated among the audience and critics, one might find it quite surprising that Vallini’s part is missing from the catalogue. While the section dedicated to the musical cast presentation mentions the performer,Footnote 27 the introduction she played was not published until December 1977, nine months after Ararat’s premiere.Footnote 28 Although one could infer that the flute performance differs from the total-art framework due to the absence of ad hoc background paintings, the omission remains unexplained and reveals another discrepancy between the performance and its remnants.

Similarly, regarding the images, the catalogue excludes several visual elements except for the black-and-white graphics, such as the archaeological ruins and the homages to the European avant-garde movements. The deliberate focus on Vahramian’s creations delineates a strong emphasis on Armenian-ness, avoiding any references outside the diasporic framework. This choice has political implications as it highlights the Armenian nature of the event, while also reflecting aesthetic considerations by preserving sections of the performance’s original visuality. Although scenographic elements could serve as a valuable tool for staging cultural denial, as studies on scenography and trauma suggest,Footnote 29 both options further distance the object from an illustrative commitment.

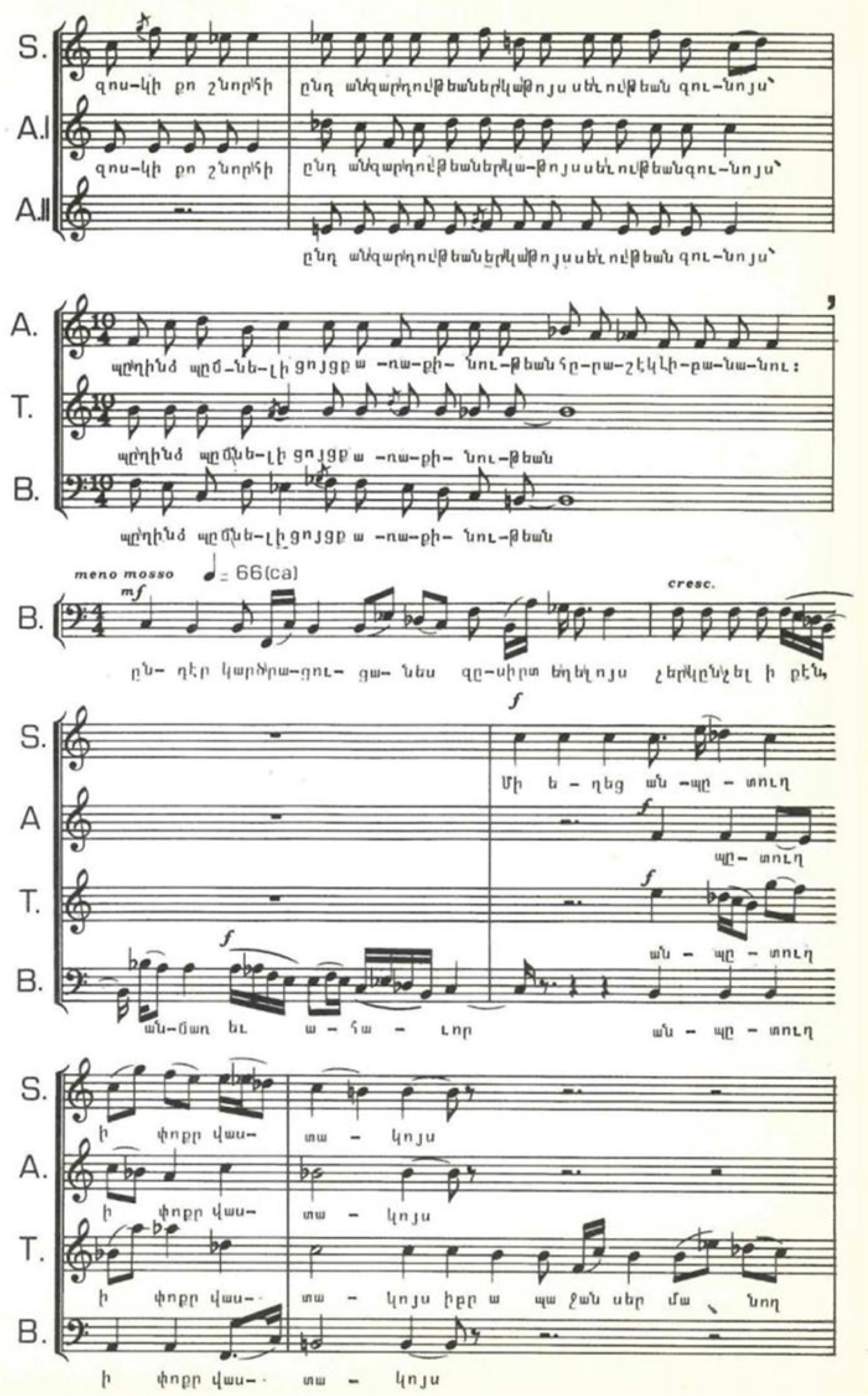

Another type of oversight characterizes the catalogue’s contents, as evidenced by the printed musical scores. The graphically sophisticated layout prioritizes formal elegance over readability. The artistic emphasis results in a few inaccuracies within the scores, particularly concerning the intricate metrical provisions and rhythmic complexities specified by Bazil. A key example involves the musical setting of the poem Matian Voghbergutian by Gregory of Narek, performed by an a cappella choir, which showcases the effects of unusual compositional writing. For this significant mystic and religious opus in Armenian spirituality, Bazil employed essential vocal scoring, homorhythmic melodies and modal developments to honour the performative characteristics of Armenian Christian liturgical chants. However, the atypical free verse adopted by the medieval poet allowed for an untethered musical discourse enriched by the dissonant language of contemporary music and, markedly, frequent tempo changes. The printed score fails to reflect these variations consistently, resulting in notable errors that musicians can readily detect (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Ararat’s musical scores frequently exhibit printing errors or significant metrical inaccuracies. In the ‘meno mosso’ section at the middle of the page, which depicts an excerpt from the musical setting of the poem Matian Voghbergutian by Gregory of Narek, note that the bass part is mistakenly notated in 4/4 time instead of the intended, and less common, 9/4 metre.

Whether they stem from archival decisions or unconscious lapses, discrepancies position the catalogue in a relationship that diverges from a mere duplication of the performance. The disparity between the ephemeral nature of the live show and the mnemonic function of the catalogue implies that the latter aims to evoke rather than directly illustrate the intermedial event. This approach facilitates memory processes through archiving practices. As a supportive tool, the catalogue fulfils its role by remaining both integral to and distinct from the Ararat performance. By incorporating fallibility as a fundamental characteristic, the object unveils the challenge of documenting performance as a process of transference. It relies on a complementary rather than an overlapping relationship with the show – an interplay defined by metonymy.

Instead of being confined solely to the relic, metonymy enhances the mediation between the event and participants. As the avant-garde endeavour aimed to present a comprehensive Armenian art experience to the Milanese audience, public outreach had to consider the lasting impact on all spectators, not just the community members. This enduring and mnemonic influence relied specifically on the catalogue, which, through its essays, targeted an educated group of attendees with an interest in Armenian culture. Probably, all journalists who attended the premiere or subsequent performances of Ararat received a copy of the document, as the recurrence of phrases and concepts from the catalogue’s essays in the articles suggests.Footnote 30 For instance, the reviews constantly reference the connection between Ararat and the historical German avant-garde of the early twentieth century, an element highlighted in Ugo Ronfani’s introductory analysis.Footnote 31 Similarly, Giuseppina Manin, a critic for the prominent Milanese newspaper Il corriere della sera, defines Bazil’s compositions as ‘musical tales’ (racconti musicali in Italian), a term directly borrowed from Khachik’s musicological explanation.Footnote 32

The catalogue’s role in guiding the public outreach of the event through journalistic and news media further complicates the function that the remnant assumes in mitigating the ephemerality of the performance. As Gunhild Borggren and Rune Gade describe, the artefact evolves into a performing archive. Specifically, their theory ‘alludes to how archives are formative in shaping history and thus perform human beings, structure and give form to our thoughts and ideas’.Footnote 33 In the context of Ararat, the catalogue serves not only as a record of the performance but also as an active component in perpetuating and interpreting its significance. Due to its close association with the performance and the artists’ efforts in curating it, the volume disseminates the event’s memory to as broad an audience as possible. As the object becomes capable of performing its own contents, it unveils a sticky association with the performance, thereby solidifying its metonymic status. Ultimately, the catalogue’s dual role as both a document and a dynamic participant in the performance’s aftermath underscores its importance in preserving and extending the reach of the avant-garde project. By crafting a historiography that reflects the ongoing process of securing and revisiting memory, the item actively contributes to the narrative of the performance’s legacy.Footnote 34 The Ararat catalogue supports the nuanced interplay between materiality and mnemonic projection. Through its metonymic nature, it encompasses both the preservation of the performance and the dynamic role of the archive.

Armenian performative shifts in Milan

The Ararat project developed within a diaspora with a long-established history. The emergence of an organized Armenian community in Milan dates to the final years of the 1910s, coinciding with the diaspora resulting from the Armenian genocide. After the systematic campaign of deportation and annihilation initiated by the Young Turks in 1915, many Armenians were forced to flee both to the Middle East, as evidenced by the numerous communities currently living in Iran, Lebanon and Syria, and to Europe (in particular France) and the United States. A small but enterprising group of survivors eventually relocated to large Italian cities. The Armenians who migrated to Italy during this period boasted a high level of education and sought urban settings, such as Milan, which offered significant economic opportunities.

Over the ensuing decades, Milanese-Armenians integrated into the entrepreneurial fabric of the city. While adapting to Milanese lifestyle, they endeavoured to maintain a connection with their ancestral practices. Prior to the Second World War, the Mekhitarist College in viale Umbria, which closed in 1932, served as the principal gathering centre for the community, functioning as both a religious and a social landmark. This space hosted both administrative community assemblies and Armenian Christian rituals. Furthermore, the community organized concerts with Armenian and Italian musicians as well as dance events, theatrical performances and conferences on Armenian history.Footnote 35

In the 1950s, a clear spatial differentiation emerged between secular and religious performances as Armenians bolstered their presence in Milan by supporting the construction and organization of their most cherished communal spaces. Casa Armena Hay Dun (Armenian House) in piazza Velasca, instituted in 1953, immediately became the primary venue for concerts, balls and conferences.Footnote 36 Until the 1970s it hosted opera singers, composers and musicians of Armenian descent, hailing from Italy and from the Soviet Union, Lebanon and Turkey.Footnote 37 Additionally, the Armenian Apostolic Church, erected in via Jommelli in 1955, provided a location for Armenian Christian rituals and their distinctive liturgy.Footnote 38

The groundbreaking rupture represented by the Ararat endeavour in the 1970s lies in its divergence from established aesthetic and spatial paradigms to conceptualize an Armenian total art for the first time. Given the project’s challenging nature within a mostly conservative context, Vahramian and Bazil’s avant-garde initiative contributes to a more nuanced perspective on the diasporic community in the city, while connecting to the pervasive intermedial features characterizing the avant-garde scene in Milan during the 1970s. Centred around personalities such as playwright Dario Fo and composer Luciano Berio, theatrical and musical institutions in the city hosted multimedia seasons that featured provocative stage productions, visual arts and concerts.Footnote 39 Additionally, the expansive intermedial landscape influenced music festivals not directly connected to the avant-garde. Musica e poesia a San Maurizio (Music and Poetry at San Maurizio) serves as a pivotal example, as it had been held in the church of San Maurizio since 1976 – just a year before Ararat was performed in the same space. Conceived by musicologist Sandro Boccardi, the festival featured Renaissance music concerts and poetry readings. The scenographic presence of the church’s frescoes, created by eminent sixteenth-century local painters, notably Bernardino Luini and his sons, intensifies the performances with a rich visual experience. Just like Ararat, Musica e poesia thus embodies a convergence of three main media: music, literature and image.Footnote 40

The Ararat project reveals an underrepresented aspect of the widespread Milanese trend. Within the Milanese-Armenian context, the Iran-born painter Herman Vahramian and composer Ludwig Bazil stand out as key representatives of this other avant-garde endeavour. Being childhood friends, their biographies developed concurrently along parallel and intersecting trajectories. Vahramian (1940–2009) was born in Tehran, the capital of Iran, where he pursued studies in classical Armenian painting and sculpture during the 1950s. Like many of his contemporaries, he decided to continue his education in Europe, selecting Rome as the destination for his major in architecture. He relocated to Milan in 1969 to attend classes at the Politecnico di Milano, a renowned technical university known for its programmes in engineering, architecture and design. In Milan, he became one of the most active supporters of the cultural activities of the Armenian community. In the early 1970s, he exhibited his works at Armenian House, showcasing an eclectic style developed from abstract painting and influenced by the curvilinear forms of Perso-Arabic script. His ideas materialized in stylized and evocative tortuosity, harmonizing with the stylistic features of graphic art.Footnote 41

Born in Hamadan, approximately halfway between Tehran and Iran’s border with Iraq, Bazil (1931–90) also completed his education in Rome. After graduating in composition and violin from the prestigious Santa Cecilia Academy, he returned to Iran, where in 1959 he founded the Hay Yerg (Armenian Singing) ensemble to preserve the scholarly and folkloric traditions of his native people. He served as the director of the Tehran Opera Chorus until 1964, after which he permanently settled in Munich, Germany. He maintained a deep connection to Italy, and during one of his many visits, he reunited with his old friend Vahramian. This renewed acquaintance inspired them to conceive an ambitious project that combined music and painting in the city where Vahramian had relocated.Footnote 42

The confluence of media lies at the heart of their research process. Owing to a theoretical focus on intermediality, the catalogue of the performance and the press release described Ararat as an Armenian avant-garde project aiming to harness a minoritarian culture.Footnote 43 Rather than being simply juxtaposed, music, poetry and painting interwove in a collaborative web of references. In his essay, Khachik compares Bazil’s compositive development to a literary narrative, describing it as a ‘musical story … transforming the real musical background into an abstraction’.Footnote 44 An abstract sensibility is similarly evident in Vahramian’s paintings, which exhibit a heightened intermedia awareness. Scheiwiller elucidates that his sinuous arabesques aim at ‘the merging of hearing and sight … seeking to operate musically in order to obtain a “sound painting”’.Footnote 45

The catalogue as a remnant of the project complicates the archiving of Ararat’s ephemeral networks. Its intermedial presentation markedly differs from the immediacy of live performance. By departing from the event itself, the record confronts the inevitable issues of disappearance, displacement and metonymy. Due to the impossibility of fully capturing the performance through the materiality of a printed book, the catalogue establishes a proximate relationship with the event by reiterating the artistic and conceptual themes that informed the Ararat performance. Hence, the artefact involves intermediality through its editorial layout and design. It presents scores and paintings side by side, with accurate references to the poems selected for the musical pieces, thereby intentionally delegating the realization of these aesthetic concepts to the live act. Thus the effort to configure the interaction among the arts does not aim to replace the performance but functions as an integral part of it, serving both as a guiding resource for the audience and as a means of preservation and remembrance. As a metonymy, the catalogue not only reflects the performance’s artistic and conceptual themes, but also contributes to historiographical discourse by sustaining the embodied memory of the event within the Armenian diaspora of Milan, ultimately conveying the cultural narratives of the community.

The process of writing a historiography of Ararat based on the performance remnants, such as the catalogue, necessitates a metonymic approach shaped by the material evidence itself. Such a perspective does not preclude the development of a coherent narrative. Instead, it allows for a more sophisticated understanding of the porous boundaries between the event and its remains.

A catalogue of denied culture

Beyond its aesthetic value, the primary objective of the Ararat project involved direct engagement with the Italian public discourse of the 1970s, addressing the prevailing lack of awareness about Armenian culture. During an interview at the premiere, Vahramian articulated that the show intended to familiarize the Milanese audience with the core aspects of a largely unfamiliar culture, through contemporary art that reflected Armenian heritage.Footnote 46 This sociocultural initiative emerged as a product of a generational divide. By the mid-1970s, younger members of the Armenian-Italian community, particularly those in Milan, were criticizing their predecessors for being excessively detached from engagement with Italian public debates, which they believed older generations had deliberately avoided to preserve their cultural origins. These concerns appeared in the Armenian monthly newspaper La voce – Zain (The Voice), first published in Milan in 1975. In its second issue, editor Rita Agopian critiques elderly ‘members of [the Armenian] community’ who ‘due to their deep attachment to traditions, fear that these traditions will be lost’.Footnote 47 Agopian argued that embracing a new openness to Italian society could help revive communal cultural roots. At the time, superficial categorizations positioned Armenian culture between Middle Eastern exoticism and Soviet communism, under whose rule the Republic of Armenia fell in 1921, shortly before the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Venues like Zain aimed not only to establish an unprecedented cultural touchstone within the community but also to highlight the distinct features of Armenian culture to the Italian context.Footnote 48 The Milanese community’s shift in stance paralleled the efforts to bring the Armenian genocide to the forefront of public discourse. While commemorations had historically occurred within the private confines of the scattered Armenian communities across Italy, 1976 marked the first public event in Rome commemorating the tragedy of 1915.Footnote 49

Both Vahramian and Bazil played integral roles in the cultural milieu of the 1970s and remained committed to heritage recovery outreach following the San Maurizio endeavour in 1977. Ararat served as the catalyst of a wide range of cultural projects spearheaded by the two artists. Shortly after the total-art performance, they launched the I/COM (Institute for Research and Dissemination of Non-dominant Cultures), a multidisciplinary association focused on diaspora and cultural studies.Footnote 50 The publication of proceedings from the institute’s inaugural 1978 conference at the Club Turati in Milan bore the eloquent title La struttura negata (The Denied Structure). In his introduction, Italian sociologist Giorgio Pacifici remarked, ‘The denial of the problems of [minority] groups is manifested by the way their problems are dealt with … since they are not considered important enough to be brought to the attention of the general public.’Footnote 51 The critique directly addressed the disregard for Armenian concerns in Italian cultural and political circles, stressing the concept of denial as a perpetuation of the collective trauma inherent in Armenian history.

The emphasis on denial as a form of cultural trauma facilitates a link to broader discussions on archival practices and responses to cultural marginalization. Ann Cvetkovich, in her exploration of emotions and archives within minoritarian communities, observes that ‘trauma challenges common understandings of what constitutes an archive’, and thus ‘[t]he memory of trauma is embedded not just in narrative but in material artifacts’.Footnote 52 In their attempts to confront the ongoing impact of trauma through cultural denial, Armenian communities imbue material records with a mnemonic significance, thereby endowing the act of archiving with a deeper affective resonance.

By reconnecting the performance relic with the archive and a potential Milanese-Armenian historiography, the record stands out as one of the ‘strategies of self-enactment’ for the minoritarian community.Footnote 53 When considering the Ararat catalogue as an archival remnant, with its dual existence as both text and material artefact, it becomes apparent that specific practices of the denied Armenian culture influenced its archiving methods. One notable aspect is the emphasis on editorial design, a defining feature of Vahramian’s work. In subsequent publications for I/COM, he utilized book layouts as a vehicle to express his artistic conception at its most advanced level.Footnote 54 Vahramian’s profound passion for written and printed material within Armenian culture reflects a long-standing reverence for paper as a significant medium. Given the substantial role that Christianity plays in shaping Armenian identity, Armenian communities treat physical books with a high regard akin to that of sacred texts.Footnote 55 Armenian liturgy dictates that priests must not touch the Holy Scripture directly, but only after it has been enveloped in a ceremonial embroidered cloth. Similarly, Armenian medieval manuscripts frequently include admonitions to handle ancient volumes with the utmost care and respect, emphasizing the need to avoid damaging or soiling their pages. The intersection of sacrality and materiality instills any book produced within Armenian communities with a collective affective meaning.Footnote 56 Consequently, within the archival context, Armenian textual records acquire a communitarian ‘social life’ that lies ‘at the heart of the interplay between the fields of “heritage” and “religion,” namely the heritagization of the sacred and the sacralization of heritage’.Footnote 57 This osmotic process results in a hallowed attachment that creates a bond among members of Armenian culture, investing the book as an object imbued with heightened significance within a communal and diasporic context.Footnote 58

Additionally, intermediality pertains to the highly regarded heritage of medieval miniatures, another central facet of Armenian book culture. Considered a form of national pictorial art, these manuscripts integrate textual elements – whether literal, religious or occasionally musical – with intricately refined illustrations.Footnote 59 The fusion of artistic languages and media produces evocative layouts, which serve as a foundational reference for the elegant design evident in the modern Ararat catalogue. The artefact, which can be regarded as an archive of marginalized mise en page practices within book culture, becomes particularly compelling due to its proximity to the performance.

The catalogue’s contents function metonymically, reflecting the cultural and material significance of Armenian book practices. By embodying values of reverence and preservation, the catalogue offers insight into the cultural importance of archival practices within the Armenian community. Its role extends beyond simple documentation to serve as a vital artefact that connects past practices with contemporary archival methods. The catalogue uncovers the timeless relationship between the sacredness of the text and the artistic efforts involved in producing editorial materials.

Conclusion

The archival relic of an overlooked avant-garde performance by Milanese-Armenian artists functions as metonymy for the event. The object overtly admits its inability to fully capture the performance, exposing that it cannot represent it ‘completely’. Rather than framing the remnant negatively, this acknowledgement facilitates a productive interplay, allowing metonymy to emerge. The Ararat catalogue encapsulates the performance’s intermedial aesthetics and abstract approach in a shifted and fragmentary manner. Thus it functions as a metonymy for the live act, since the concepts and ideas shaping the ephemeral event have become attached to the artefact, reinforcing its proximity to the performance.

The Ararat catalogue serves as a performance archive, complicating conventional understandings through a marginalized framework that engages embodied memory to facilitate both preservation and ongoing reinterpretations. It draws on Armenian archival practices that emphasize the sanctity of book culture by actualizing these heritages through the graphic vision of Vahramian, whose visual approach complements the transient essence of the music performed. The performance primarily focused on the sound atmosphere created by Bazil and its interactive references to ancient poetry and modern paintings. The printed volume responds to disappearance by highlighting the residues left behind, retaining scores and sketches. Conceived specifically for the performance, the catalogue exists as an ephemeral object that carries cultural and historical significance despite its impermanence. While short-lived in its material form, it serves as a remnant for a potential counterhegemonic historiography, activated through the artefact’s metonymic features.Footnote 60

The remnant involves a non-univocal time, allowing ephemera to retain presence even after the event and project it toward the future, thus inducing narrations and memories.Footnote 61 The creators of Ararat envisioned the performance as a challenge in recognizing Armenian cultural and artistic specifics, aiming to endure this vision. Consequently, the catalogue played a role in publicizing the event. The essays provided critics and reviewers with a source, guiding the dissemination of the show in Milanese news and forging a shared interpretation of it. Hence it functions as a performing archive that acts beyond the event it evokes.

Such considerations elevate the Ararat catalogue to a status beyond the auxiliary tool. It stimulates mnemonic and evocative operations through its materiality, becoming an essential part of the performance’s legacy. The volume allows users, both within and beyond the Armenian community, to engage with the past artistic event. Although the artefact cannot entirely represent the project, it writes its historiography through the suggestions it facilitates. The interplay of metonymy, archive and memory enhances the affective dimension of the performance object.

Unfortunately, evidence suggests that the Ararat project has not fully achieved its original goals. Although Milan’s reception of the performance showed appreciation, Ararat did not prominently bring the Armenian genocide and recognition of the Armenian people into broader public discourse. Instead, the Armenian diaspora continued to occupy a secondary role within the Italian sociocultural context. The project primarily affected the Milanese community, which, while significant, did not possess the influence required to amplify its voice on a national scale.Footnote 62

The discussion shifts when considering Ararat’s role within the community framework. As an artistic venture that deviated from the community’s established performing habits, the performance helped Vahramian and Bazil emerge as pivotal figures in cultural activities beyond the Milanese diaspora. As a precursor to the international I/COM project, Ararat gains relevance in the historiography of Armenians in Milan, Italy and Europe. Nevertheless, its contributions have frequently gone unrecognized, as it was often overshadowed by the political focus emphasized in the I/COM conferences. This foundational performance serves as a valuable historiographical resource for a more nuanced understanding of the Armenian diaspora’s role in Italy.

The catalogue demonstrates how the diasporic context informs the archiving of the disappearing performance. Through its graphic dimension, it reveals the metonymy embedded in the artefact, transforming its materiality into a means for prolonging the minoritarian project. Contributing to the possibility of narrating a marginalized historiography, the object emerges as a medium of material memory. An Armenian avant-garde in an urban diaspora, the Ararat project showcases how minoritarian artists actively work to overcome barriers, benefiting both their own community and broader society. Performance serves as both a political and an affective means of advocacy, sustenance and persistence for the community albeit with limitations.