Introduction and rationale

Affective polarization – that is, the deep divide between partisan in‐groups and out‐groups that is driven by affective considerations – has become a defining feature of contemporary Western democracies (Garzia et al., Reference Garzia, Ferreira da Silva and Maye2023; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012), shaping political attitudes and behaviour. Heightened affective polarization has been associated with lower willingness to cooperate with political opponents (e.g., Abramowitz & Webster, Reference Abramowitz and Webster2016; Finkel et al., Reference Finkel, Bail, Cikara, Ditto, Iyengar, Klar, Mason, McGrath, Nyhan, Rand, Skitka, Tucker, Van Bavel, Wang and Druckman2020), undermining support for democratic principles (Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021, but see also Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2023) and even increased support for political violence (Kalmoe & Mason, Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022). The negative consequences of this partisan animosity extend beyond the political realm, carrying broader societal implications. Polarized individuals are less likely to marry, befriend or socialize with people from out‐parties, even when they belong to the same family (Chen & Rohla, Reference Chen and Rohla2018; Huber & Malhotra, Reference Huber and Malhotra2017). Intra‐party hostility may also possibly negatively impact citizens’ health and well‐being (Nelson, Reference Nelson2022). Affective polarization can, furthermore, have important economic impact, introducing biases in professional activities (Gift, & Gift, Reference Gift and Gift2015), economic expectations (Guirola, Reference Guirola2022) and conditioning consumption patterns (McConell et al., Reference McConnell, Margalit, Malhotra and Levendusky2018).

Within the manifold drivers of affective polarization that have been identified in the literature (for a review see, e.g., Iyengar et al., 2019), attention is increasingly turning towards the role of political elites. On the one hand, this “top down” effect could be fundamentally ideological, manifesting through a growing ideological divide among the positions of elites, that is, elite polarization (Banda & Cluverius, Reference Banda and Cluverius2018). On the other hand, it could derive from elites' political communication styles and political rhetoric, for example, their use of political attacks (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Andersen, Ditonto, Kleinberg and Redlawsk2017; Martin & Nai, Reference Martin and Nai2024) or incivility during election campaigns (Liang & Zhang, Reference Liang and Zhang2021; Mutz, Reference Mutz2007). Against this backdrop, however, it remains unclear to what extent specific characteristics of politicians themselves, and in particular their personalities, relate to levels of mass affective polarization.

Recent research has asserted the relevance of polarized feelings towards political leaders (Ahn & Mutz, Reference Ahn and Mutz2023; Druckman & Levendusky, Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019; Reiljan et al., Reference Reiljan, Garzia, Ferreira da Silva and Trechsel2024). At the same time, we have seen a stark rise in popularity of politicians, often populists, with a dark, divisive and uncompromising personality – some examples immediately come to mind, from Donald Trump in the United States (US) to Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil. This type of politician tends to be disliked by the public at large, while being at the same time rather popular among more aggressive voters (e.g., Nai, Reference Nai2022; Nai et al., Reference Nai, Aaldering, Silva, Garzia and Gattermann2023). Because voters take cues from their leaders, both on issue stances and on attitudes (e.g., Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2010), a fundamental – yet, as of today, unanswered – question is whether such cue taking also unfolds with regards to the dark personality of political leaders when it comes to affective polarization. Can the presence of leaders with dark personality traits be associated with affective polarization?

In this article, we investigate to what extent politicians’ dark personality traits – that is, the ‘dark triad’ of narcissism (bombastic self‐promotion and egotistic entitlement), psychopathy (coldness and callous disregard of others’ emotions) and Machiavellianism (proclivity for cunning and scheming behaviours) (Paulhus & Williams, Reference Paulhus and Williams2002) – is linked to heightened levels of intra‐party animosity in the public.

Specifically, our intuition is that it is in particular the (dark) personality of in‐party politicians that matters. Insights from several streams of research support this intuition. First, from the psychological standpoint of information processing, ideologically congruent cues should be expected to be the most influential for people's opinion. As amply shown by research in motivated reasoning (Kunda, Reference Kunda1990; Slothuus & De Vreese, Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010), humans are hardwired to reject attitudinally incongruent cues and lend an attentive ear to inputs that match their predisposition, may they be ideological or otherwise. Specifically, partisans tend to sample information from the ideologically congruent in‐group preferentially, leading them to develop more skewed evaluations in favour of that in‐group (Derreumaux et al., Reference Derreumaux, Bergh and Hughes2022), while at the same time actively engaging in motivated rejection of inconsistent information (Jain & Maheswaran, Reference Jain and Maheswaran2000). With this in mind, normative cues from ideologically proximate elites should be more influential than equivalent cues from disliked or ideologically distant elites.

Second, while expressions of political aggressiveness – in our study dark personality traits in elites, but also the use of political attacks and incivility – tend to be generally disliked by the public at large (Bøggild & Jensen, Reference Bøggild and Jensen2024; Frimer & Skitka, Reference Frimer and Skitka2018; Nai & Maier, Reference Nai and Maier2024), it is to be expected that this should not be the case in hyper‐partisan situations. In times of heightened political conflict (for instance during elections), voters are expected to undergo a stronger pull from in‐group loyalties, possibly even leading them to support a more muscular profile in their elites (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012). In line with this logic, Laustsen and Petersen (Reference Laustsen and Petersen2020) show that voters showcase a stronger preference for more ‘dominant’ candidates in times of increased political conflict. In competitive contexts such as elections, in other terms, more dominant and dark personality traits in in‐party elites can be expected to exert a stronger pull in voters.Footnote 1

Third, and more generally, considerable evidence exists that voters express a preference for candidates that showcase a similar personality profile as their own (Aichholzer & Willmann, Reference Aichholzer and Willmann2020). With this in mind, we could expect that people feeling particularly close to dark politicians to be more likely to espouse a more aggressive and confrontational political stance themselves as well, for instance when it comes to affective polarization. Evidence showing that it is particularly voters high in populist attitudes that express a high appreciation for darker candidates (Nai, Reference Nai2022) seems in line with the general idea.

All in all, these different strands of research seem to suggest that voters should pay more attention to cues coming from in‐party candidates, and that dominant and generally ‘dark’ traits could be more likely to exert an effect on subsequent political attitudes. In short, we advance the intuition that it is in particular for ‘close’ (in‐party) candidates that dark personality traits are associated with more marked affective polarization in voters. Recent evidence showing a similar mechanism for campaign negativity (Martin & Nai, Reference Martin and Nai2024) seems to support this intuition.

To avoid excessive case‐driven determinism (e.g., the fact that dark traits in politicians might be more endemic in the politics of certain countries or electoral systems), we test our intuition on a large‐scale dataset that covers more than 90 ‘top’ politicians having competed in 40 recent (2016‐2021) national elections worldwide ‐ from Donald Trump to Angela Merkel, Emmanuel Macron, Narendra Modi and many more ‐ linked with a compilation of post‐election surveys with national samples of voters (CSES data). Our results show that the dark personality of top politicians can be associated with upticks in affective polarization in the public – but only for candidates of voters’ in‐party (that is, their preferred party), and only for high levels of ideological proximity between the candidate and the voter. All data and codes are available for replication and re‐analysis at the following OSF repository: https://osf.io/2c7w4/

Data and methods

Datasets

We link two independent data sources. Measures for the personality of candidates come from a large‐scale expert survey covering a large sample of national elections worldwide between 2016 and 2022 (NEGex dataset; Nai & Maier, Reference Nai and Maier2024). After each election covered, a sample of experts rated candidates for both the Big Five and the Dark triad (see below). Experts are scholars with expertise in electoral politics, political communication, country politics, identified via their scientific outputs (publications) and self‐described expertise (e.g., on their personal website). Table A2 (online Appendix A) includes, for each election, details about the average expert that provided ratings for all countries included in the investigation.

Measures for mass affective polarization come from the Module 5 (2016‐2021) of the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES),Footnote 2 a collection of post‐electoral surveys including a common module of questions across countries. The overlap between NEGex and the CSES includes 91 ‘top’ candidates having competed in 40 unique national elections in both two‐party and multi‐party systems across the world. The list includes world top players such as recent US presidential candidates Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump and Joe Biden, Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil), Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen (France), Angela Merkel (Germany), Theresa May, Jeremy Corbyn and Boris Johnson (UK), Viktor Orbán (Hungary), Narendra Modi (India), Silvio Berlusconi (Italy), Shinzō Abe (Japan), Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (Turkey), Mark Rutte and Geert Wilders (The Netherlands) and many more (see Table A1 for the full list).

In order to isolate the effects of personality traits of specific candidates, we have pooled all country‐level datasets and assigned at the upper level for each voter (i) the personality of their preferred candidate (in‐party), and (ii) the personality of their most disliked candidate (out‐party). In‐party candidates have been assigned based on the party respondents declared to feel closest to; individuals that declared not to feel close to any political party were thus excluded from the analysis. Out‐party candidates have been identified based on the party leader receiving the lowest feeling thermometer score among all leaders scored by a respondent; individuals scoring equally low two or more candidates have been excluded from the analysis because we were unable to uniquely identify the personality of the least liked candidate.

The pooled dataset, hierarchical in nature (voters nested into their preferred candidate), includes information for approximately 34,000 individuals and 91 unique candidates.

Measures

Dark personality of candidates

The NEGex questionnaire asks experts to rate the personality of a selection of 2–3 top candidates for the election surveyed. Three dark personality traits, that is, Machiavellianism, psychopathy and narcissism, are measured via a simplified version of the ‘Dirty Dozen’ (D12; Jonason & Webster, Reference Jonason and Webster2010). Experts had to assess whether the candidate might be someone who, for example, ‘wants to be admired by others’ or ‘tends to be callous or insensitive’ (from 0 ‘disagree strongly’ to 4 ‘agree strongly’).Footnote 3 Scores on items are averaged to yield separate measures for narcissism (M = 2.8, SD = 0.7), psychopathy (M = 2.2, SD = 0.9) and Machiavellianism (M = 2.1, SD = 0.8). The average score on the three traits reflects the ‘dark core’ of candidate personality (M = 2.4, SD = 0.7).

To isolate the specific effect of dark personality traits, all models control for the candidate Big Five personality traits. We rely on the ten items personality inventory (TIPI; Gosling et al., Reference Gosling, Rentfrow and Swann2003), which yield five separate variables for extraversion (M = 2.4, SD = 0.8), agreeableness (M = 1.7, SD = 0.8), conscientiousness (M = 2.7, SD = 0.8), emotional stability (M = 2.3, SD = 0.8) and openness (M = 1.9, SD = 0.7). To avoid over‐specifying the models by including five measures, we use them to compute the ‘huge two’ meta‐traits of plasticity and stability (Silvia et al., Reference Silvia, Nusbaum, Berg, Martin and O'Connor2009), reflecting, respectively, average scores of extraversion and openness (plasticity; M = 2.2, SD = 0.6) and agreeableness, conscientiousness and emotional stability (stability; M = 2.2, SD = 0.7). Table A2 (online Appendix A) includes the personality scores for all candidates in the analysis (separate dark traits, plus three meta‐traits of dark core, plasticity and stability). The average level of agreement across all experts on the personality traits rated is relatively good, as indicated with standard deviations that are not excessively high; the higher average standard deviation (SD = 1.04, reflecting a range just above 20per cent of the 0–4 original scale) is for the statement ‘Tends to use flattery to succeed’ (second item for the Machiavellianism trait), whereas the lower average standard deviation (SD = 0.87) is for the statement ‘Wants attention from others’ (second item for the narcissism trait).

It might seem unorthodox to rely on expert ratings to measure the personality profile of leading political figures. Yet, especially when working on large‐scale comparative investigations, no valid alternative exists (as of today); self‐assessments (e.g., via questionnaires; Maier et al., Reference Maier, Oschatz, Stier and Zettler2023) are unrealistic, and the analysis of candidates’ output, such as speeches (e.g., Ramey et al., Reference Ramey, Klingler and Hollibaugh2017) remains possibly complex when different languages come into play. Of course, using expert ratings should not be done incautiously, most notably due to the possible biasing effect of experts’ ideological preferences with regards to the candidates they are asked to assess (e.g., Wright & Tomlinson, Reference Wright and Tomlinson2018). With this in mind, we will discuss below two important sets of robustness checks, that (i) use adjusted measures of personality that ‘filter out’ the effect of average expert ideological leaning, and (ii) control for the average profile of experts, including their ideological leaning. Results of these checks yield robust results, suggesting that the potentially biasing role of experts’ political leanings, while certainly not absent, should not be overestimated.

Affective polarization

Feeling thermometers have typically been used as the workhorse instrument to measure affective polarization in comparative perspective (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). The CSES surveys include a 0–10 feeling thermometer asking respondents to rate candidates in their country, where 0 denotes maximum dislike and 10 denotes maximum liking. Leveraging on these items, we adapt Reiljan's (Reference Reiljan2021) Affective Polarization Index, replacing party with candidate feelings thermometers. Since the primary focus of interest of our research question is the relationship between candidates’ personalities and affective polarization, we deem it more plausible that their personality translates most significantly into polarized feelings towards party leaders, along the lines of recently proposed conceptualizations of Leader Affective Polarization (Reiljan et al., Reference Reiljan, Garzia, Ferreira da Silva and Trechsel2024).Footnote 4

This measure calculates, for each respondent, the mean difference between the thermometer score given by survey respondents to the leader of the party they identify with and each other party leader running on any given party system, weighted by their respective parties’ vote shares. The resulting measure ranges from 0 (Minimum distance/polarization; all leaders receive the same score on the feeling thermometer) to 10 (Maximum distance/polarization; the most liked leader is rated with a 10 and all other leaders with a 0).

Results

To what extent is the personality of major political figures associated with affective polarization in the public? We answer this fundamental question by looking, first, at the driving role of the personality of in‐party candidates, that is, the personality traits of candidates of respondents’ preferred party. In a second time, we will replicate the analysis but looking at the personality of out‐party candidates, that is, the personality traits of candidates of respondents’ most disliked party. In line with the idea that proximity should be more likely to drive attitudes, we expect stronger effects exerted by the personality of in‐group, versus out‐group, candidates.

In‐party candidates

The dark personality profile of respondent's in‐party candidate is not directly associated with a significant or substantial higher (nor lower) level of affective polarization (Table B1, model M1, Appendix B). This is also the case for the two other personality traits, that is, the meta‐traits of plasticity (extraversion, openness) and stability (agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability).

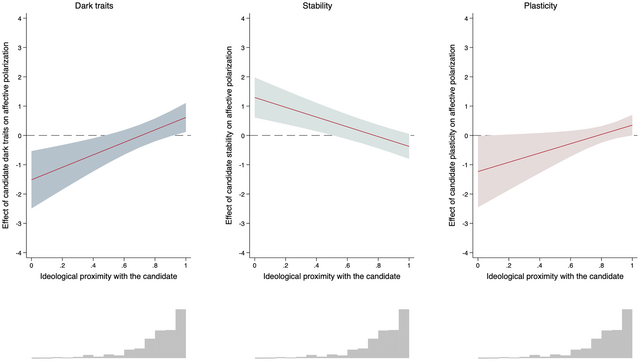

We do, however, find strong support for the general idea that candidate proximity matters. Figure 1 plots the results of three separate models, where the effect of the in‐party candidate personality traits on respondents’ level of affective polarization are moderated by the ideological distance between the respondent and the candidate.Footnote 5 The leftmost panel tests for the moderated effect of candidate dark traits, the middle panel for the moderated effect of candidate stability, and the rightmost panel for the moderated effect of plasticity. All models are controlled for important covariates at the candidate (gender, age, incumbency status, left‐right ideology), country (regime type, number of effective parties, geographical region) and voter levels (gender, age, interest in politics). Full results are in Tables B1 (model M2) and B2, Appendix B. All panels plot marginal effects with 95 per cent confidence intervals, reflecting the effect of personality on affective polarization for increasing proximity between the candidate and the voter (x‐axis).

Figure 1. Affective polarization by in‐party candidate personality * ideological proximity with the candidate.

Note. Marginal effects with 95 per cent confidence intervals. All covariates fixed at their mean value. Full results in Tables B1 and B2 (Appendix B).

As the figure shows (leftmost panel), for high levels of ideological proximity between the in‐party candidate and the voter, the effect of candidate dark personality on affective polarization is positive, whereas it is negative for candidates that are more ideologically distant.Footnote 6 Inversely (middle panel), though more weakly so, the effect of candidate stability on affective polarization is negative for high levels of ideological proximity, whereas it is positive for low levels of proximity. Finally, there does not seem to be a meaningful interaction effect between plasticity and proximity (rightmost panel). All in all, very close in‐party candidates’ dark traits bolster affective polarization, whereas stability somewhat reduces it. Compared to the other two meta‐traits, the effects are strongest for the dark traits, likely reflecting the importance of negative assessments (negativity bias) over positive ones.

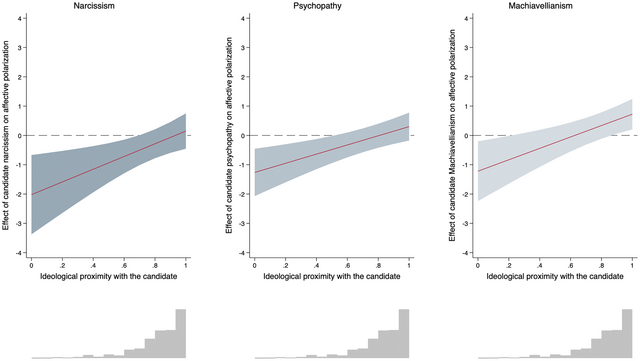

Figure 2 presents models that replicate the same analysis, but for the three dark traits taken separately (full results in Table B3, Appendix B). While the effect is nominally stronger for narcissism, it is for Machiavellianism that we find the strongest moderation of close ideological proximity on the positive effect of in‐party candidate personality trait on affective polarization. While a significant upwards trend appears also for narcissism and psychopathy, the effect at high levels of proximity is less clear‐cut for these two dark traits.

Figure 2. Affective polarization by in‐party candidate separate dark traits * ideological proximity with the candidate.

Note. Marginal effects with 95 per cent confidence intervals. All covariates fixed at their mean value. Full results in Table B3 (Appendix B).

It is important to note that the main trends for the dark meta‐trait are replicated in alternative model specifications in four key robustness checks. First, because expert ratings of social and political phenomena have been criticised in the past for the potential presence of ideological biases (e.g., Wright & Tomlinson, Reference Wright and Tomlinson2018), we estimated models with an ‘adjusted’ measure of personality that ‘filters out’ such biasing influence.Footnote 7 These yield even slightly stronger results (Table B4). Second, the main results hold in models controlling for the average profile of experts in terms of gender, domesticity, left‐right ideology, familiarity with elections in the country and ease of answering the survey (Table B5). All in all, what these additional models seem to suggest is that the positive effect of dark personality on affective polarization, for ideologically close in‐party candidates, is likely not a fluke due to biased measurement. Third, additional models that control for the ‘dark’ rhetoric employed by the candidates during the election, in terms of their use of political attacks and fear appeals,Footnote 8 yield robust results (Table B6). These additional controls are important to ensure that the effect unfolded by the dark personality traits on affective polarization comes from personality itself, and not from the fact that dark candidates are more likely to use more aggressive rhetoric in their campaigns (Nai & Maier, Reference Nai and Maier2024, Reference Nai and Toros2020). Finally, fourth, the results are robust – and even slightly stronger (Table B7) – when using an alternative measurement for the dependent variable that relies on party instead of candidate feeling thermometers. For this alternative dependent variable, our models even pick up a significant (p < 0.1) direct positive effect for candidate dark traits on affective polarization (model M1).

Out‐party candidates

To what extent do we find similar trends when it comes to the (dark) personality traits of out‐group candidates, that is, candidates of respondents’ most disliked party? On paper, while the effect should likely be stronger for in‐party candidates, reasons exist not to exclude an effect for out‐party candidates as well. Much evidence exists that voters make up their mind also with regards to candidates or parties they particularly dislike (‘negative voting’; e.g., Garzia & Ferreira da Silva, Reference Garzia and Ferreira da Silva2024), which suggests that such despised actors can alter the way they feel about politics in general.

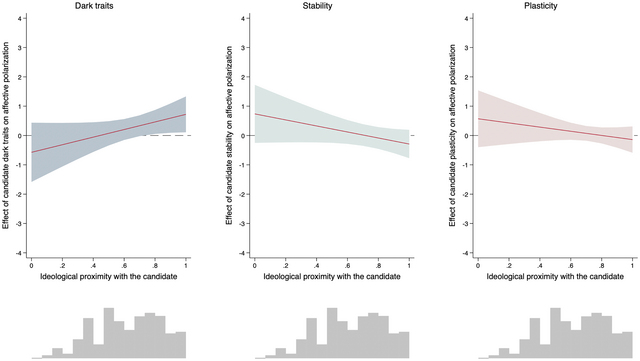

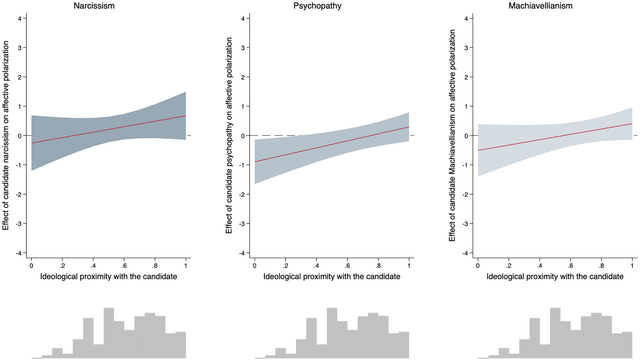

As earlier for in‐party candidates, the personality of out‐party candidates does not affect directly respondents’ levels of affective polarization (Table C1, model M1, Appendix C). None of the three meta‐traits (dark core, stability, plasticity) has a significant direct effect. Additionally, the effect of personality is in this analysis a weaker function of the ideological distance between the voter and their most disliked candidate; proximity does significantly interact with dark traits, but rather weakly so and only significantly at p < 0.1 (see also as Figure 3, left‐hand panel). None of the three dark traits, taken separately, drive affective polarization upwards (or downwards) in a substantial way with changing levels of voter‐candidate distance. Our models do pick up a significant (but rather weak) effect for psychopathy (Table C3, model M2, Appendix C; see also Figure 4): increasing levels of psychopathy in the most disliked candidate are associated with higher affective polarization for candidates that are less ideologically distant. Beyond being relatively weak, this effect is not suggestive of strong out‐group effects – for that, we would have had to identify stronger effects for dark traits among disliked candidates that are particularly far ideologically from the voter, which is not what we find. If anything, then, this effect is again suggestive that it is not candidates that are relatively far from the voter (either ideologically, or in the out‐party) that matter when it comes to their personality, but rather candidates that are close to them.

Figure 3. Affective polarization by out‐party candidate personality * ideological proximity with the candidate.

Note. Marginal effects with 95 per cent confidence intervals. All covariates fixed at their mean value. Full results in Tables C1 and C2 (Appendix C).

Figure 4. Affective polarization by out‐party candidate separate dark traits * ideological proximity with the candidate.

Note. Marginal effects with 95 per cent confidence intervals. All covariates fixed at their mean value. Full results in Table C3 (Appendix C).

The (already weaker) interaction between candidate dark traits and proximity, furthermore, disappears when using adjusted measures of personality that filter out the possible intervening effect of experts’ ideology (Table C4), even if it resists in models that control for average expert profile (Table C5) and candidates’ usage of negative and fear‐based rhetoric (Table C6), and in models that use an alternative dependent variable based on party thermometers (Table C7).

Conclusion and discussion

Our study addresses an important omission in the increasingly dense field of affective polarization research: whether the dark personality of political leaders can fuel affective polarization. In order to shed light on such a question, our article linked large‐scale observational data coming from two independent sources: a collection of post‐electoral survey data (CSES), and a large dataset including the personality profiles of politicians worldwide, based on expert judgements (NEGex; Nai & Maier, Reference Nai and Maier2024) – the intersection of the two yielding an integrated dataset respectively covering the personality of 90+ top politicians worldwide and the profile of more than 30,000 voters that have taken part in elections where these candidates competed.

Our results suggest that the dark personality of top politicians can be associated with heightened affective polarization in the public – but only for candidates of voters’ in‐party (that is, their preferred party), and only for high levels of ideological proximity between the candidate and the voter. The other personality traits have weaker effects, and the personality of out‐group candidates (that is, candidates of voters’ most disliked party) seems overall rather marginal. In other terms, what our results suggest is a proximity effect for dark personality in elites. Somewhat at odds with the popular idea that people might become cynical and radicalized due to how much they dislike the character of their political opponents – for example, in the US, a deepening of out‐partisan antipathy among Democrats rising in response to the cantankerous personality of Donald Trump Nai & Maier, Reference Nai and Maier2021, – what our results suggest is that dark traits in elites have an ‘in‐house’ effect. It is ‘our’ candidate, in particular if we feel close to them, that drives our partisan animosity the most – specifically, their dark traits. In other terms, our models predict that it is in particular among very close supporters of dark candidates that we find the highest levels of affective polarization. As discussed in the article's front end, this main trend should not surprise us. Voters tend to lend a preferential treatment to congruent political cues (e.g., Slothuus & De Vreese, Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010), suggesting that it is in particular the example given by proximate candidates, more than ideologically distant ones, that should be attitudinally consequent for voters. Partisan proximity, furthermore, should be particularly consequent in times of heightened political conflicts, during which voters should naturally express a stronger preference for more ‘dominant’ politicians (Laustsen & Petersen, Reference Laustsen and Petersen2020).

The trends shown in our analysis come with some notable limitations. On the one hand, although they stem from a large‐scale analysis and should thus be more resistant towards critiques of low external validity, they nonetheless build on evidence that is essentially observational in nature, with the inherent risk of endogeneity. Specifically, our data and results cannot exclude the fact that voters self‐select into being close to darker candidates because they are affectively polarized – and not the other way around. That is, we cannot prove that it is the dark personality of politicians that cause affective polarization to move upwards. Moving ahead, experimental evidence and/or longitudinal designs should be considered to disentangle the essential matter of causality between candidate profile and affective polarization in the public. Second, due to data availability, our analyses include ‘top’ politicians only – party leaders and main presidential candidates – and are unable to pick up likely effects exerted at more local levels, for instance during subnational elections. And because it seems likely that voters have a closer and more personal contact with more local candidates, we cannot exclude that the dynamics shown here exists even stronger at subnational levels.

These limitations notwithstanding, the trends shown in this article unpack a novel research agenda on the intersection between candidate (dark) personality and intra‐party animosity in voters. Beyond their intrinsic electoral interest, the findings discussed in our article are furthermore worrisome in light of dynamics of democratic backsliding (e.g., Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019). Dark traits seem to be particularly prevalent among autocrats and populist (Nai & Toros, Reference Nai and Toros2020, Nai & Martinez i Coma, Reference Nai and Martínez i Coma2019), suggesting a potentially nefarious intersection between uncompromising leaders, democratic deconsolidation and affective polarization. Further research should investigate these dynamics more in detail, including regarding the intervening role of (dark) communication strategies linking elites and voters directly.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the EJPR editors and anonymous reviewers for their inputs during the revisions process – their constructive comments were instrumental to rework our piece and get it to its current form. All remaining mistakes are of course our responsibility alone. A sincere thank you to all NEGex experts for donating their precious time, and to CSES for making the cross‐national survey data available to the scientific community. Alex Nai acknowledges the generous financial support by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF Ref. P300P1_161163).

CRediT authorship contribution statement. Alessandro Nai: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Frederico Ferreira da Silva: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Loes Aaldering: Conceptualization; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Katjana Gattermann: Conceptualization; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Diego Garzia: Conceptualization; Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Data Availability Statement

All data and codes are available for replication and re‐analysis at the following OSF repository: https://osf.io/2c7w4/

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

APPENDIX A – Candidates included and expert samples

APPENDIX B – In‐party candidates: Full results and robustness checks

APPENDIX C – Out‐party candidates: Full results and robustness checks

APPENDIX D – Research ethics

APPENDIX E – Personality batteries