Introduction

The circulation of doubtful, contestable or outright false information with harmful effects, and indeed sometimes intent, is a serious problem that the world has long endured.Footnote 1 But it has emerged as a significant societal challenge in recent years. Since the mid-2010s, a range of actors – from policymakers and politicians to civil society groups and myriad individuals – have raised concerns about the amount of misinformation and disinformation spreading across the internet, especially (but not only) in the hands of malicious actors. Information circulating during the COVID-19 pandemic amplified public anxieties and highlighted the risks associated with its societal impacts. More recently, fears about misinformation and disinformation (commonly described as misinformation with malicious intent) have increased following the widespread availability of inexpensive and easy-to-use artificial intelligence (AI) tools.Footnote 2

Older laws, including laws around defamation, privacy and data protection, fraud, deceptive acts or practices, free and fair elections, copyright and other intellectual property, are already being used to address some of these concerns. However, many states have not been comfortable relying on these and have passed additional laws. According to one study, more than half the countries of the world now have laws addressing misinformation or disinformation (Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025). Some are very tailored. For instance, some states have introduced, or are in the process of introducing, laws around hate speech, sexually explicitly deepfakes, political interference and scams. The United States is an example with its TAKE IT DOWN Act of 2025 geared to sexually explicit deepfakes. Others are broader in focus, as with the European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA) of 2022 and Artificial Intelligence Act of 2024 (AI Act) and the United Kingdom’s Online Safety Act (OSA) of 2023. Australia and Singapore, our home countries, offer further interesting examples.

Nevertheless, the argument of this Element is that the new laws, and indeed law more generally, will not be sufficient to address the diverse harms associated with misinformation and disinformation. Of course, it is too soon to assess the impact of all the current and still-to-be created laws. But one problem that is already evident is that while information easily spreads across the internet, the laws that seek to address its harms tend to be national or (in the case of the EU) regional in character. Another is that, for all the talk of ‘rights’ in this area, the harms of misinformation and disinformation may be differently perceived in different parts of the world, as may be the harms associated with efforts to regulate it. For instance, what in Europe may be considered a proportionate legal response to the harms of hate speech under the DSA, building on the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (2000), may in the US be viewed as impacting overly negatively on innovation and on free speech protected by the First Amendment (US Judiciary Committee Staff Report, 2025). A third, less noticed, problem is that even where laws may be good at deterring harmful conduct, they may do little to address the underlying social causes and build social resilience for the future. In short, we argue that while many jurisdictions have turned to legal solutions to address harms, which we go on to detail, these reform agendas can often dominate the policy conversation, leaving little air for the technical developments and social approaches that support long-term civic resilience.

The remainder of this Element represents our attempt as respectively media studies and legal scholars to advance the earlier arguments in greater detail. In Section 1, we track some of the current and emerging laws with a goal of understanding some of the actual and anticipated harms they seek to avoid or alleviate, and the ways they go about this. In Section 2, we then move on to technical efforts by digital platforms to address harmful misinformation and disinformation. Here, we explore how digital platforms are using technical systems and the extent to which these can be used to address harmful misinformation and disinformation. Some of these measures may be changing as we write, but they exemplify various currents at work. Finally, we end with our argument for exploring the role that social approaches and tools can play.

1 Proliferating Laws

1.1 Perceived Need for Legal Intervention

This section considers the growing array of legislative efforts geared (in whole or in part) to addressing the harms of misinformation and disinformation. In terms of the sheer number of enactments, these laws are noteworthy. For instance, a study conducted by Gabrielle Lim and Samantha Bradshaw for the Center for International Media Assistance and the National Endowment for Democracy reports that, globally, ninety-one items of legislation were enacted between 2016 and 2022 to address misinformation and disinformation (Lim and Bradshaw, Reference Lim and Bradshaw2023). Another study from Simon Chesterman at the National University of Singapore reports that, as at the start of 2024, more than half the countries of the world had adopted laws designed to ‘reduce the impact of false or malicious information online’ (Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025: 934).

While touched on in the second study, we pay particular attention in this section to two significant pieces of regional and national legislation adopted in 2022 and 2023 which are geared specifically to platforms that host and circulate misinformation and disinformation posted by users, namely the EU DSA and the UK OSA. (The Australian version of the OSA was passed in 2021, albeit in more restricted form.) As Chesterman points out, and as we come back to later, in practice ‘much [in this space] has depended on technical interventions by platforms’ (Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025: 944). Laws such as the DSA and OSA provide some legal oversight but bring their jurisdictions into sharp relief with the US where § 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA) of 1999 provides that platforms are generally immunised from legally responsibility for content posted by users,Footnote 3 and ‘good Samaritan’ interventions by platforms are further protected from legal responsibility (Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025: 946).

Another focus of this section is the EU AI Act of 2024, with its provisions currently scheduled to come into operation in stages from February 2025 to August 2027. This will also impact on (some) AI-fuelled misinformation and disinformation. Indeed, its impact could be very significant, although its precise reach is still not clear with much depending on how the provisions (once in force) are deployed in practice (see Duivenvoorde, Reference Duivenvoorde2025). But the EU is not the only jurisdiction to address AI-related misinformation and disinformation specifically, even if its AI Act is the most comprehensive legislation to date. For instance, in the US now, there is new federal legislation in the form of the TAKE IT DOWN Act of 2025 to address sexually explicit deepfakes (see Ortutay, Reference Ortutay2025). Other laws, such as Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act of 2019 (POFMA), are broad enough in their terms to address deepfakes (Shanmugam, Reference Shanmugam2024).

No doubt there will be more legislative efforts to come in this space. Some may be controversial, as indeed are many of the legislative efforts noted previously. However, in this section we do not seek to critique particular legislative initiatives (see, for instance, Coe, Reference Coe2023 on the OSA), or particular types or features of legislation (for a comprehensive review, see Katsirea, Reference Katsirea2024), or the definitional challenges of embedding vague terms such as ‘misinformation’ and ‘disinformation’ into law (see Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Morris and Sorial2025; OECD, 2024: 17), or the fact of using legislation to manage what some might say is ‘a sense of urgency expressed in polemical terms’ (Burgess, Reference Burgess2023). Instead, we think it is useful to treat misinformation and disinformation as a problem that can lead to real harms and then consider broadly the legislation being introduced to address concerns around these harms. At the same time, we acknowledge concerns about actual and potential impacts of these laws on other rights, freedoms and interests, such as freedom of speech and innovation. And we point out the limits of these laws, even if well designed to address misinformation and disinformation in a properly balanced, or ‘proportionate’, way – and of law in general.

1.2 Continuing Reliance on Older Laws

Of course, the new laws do not operate in a vacuum. Older laws continue to regulate and their significance should not be underestimated. For instance, users of Facebook successfully settled class action claims in California inter alia for breach of various privacy torts and negligence following Cambridge Analytica’s harvesting of their data to target political and commercial advertising without their knowledge or consent (In Re Facebook, Inc. Consumer Privacy User Profile Litigation, 2018). Such torts might also be drawn on to address AI-related practices. Indeed, some have suggested that AI was already being used by Cambridge Analytica in 2016 (see Delcker, Reference Delcker2020). More recently Scarlett Johansson’s legal dispute with OpenAI after its launch of an AI-generated voice in ChatGPT ‘eerily’ resembling her own is reminiscent of the earlier California right of publicity case Midler v Ford Motor Co where Bette Midler succeeded in arguing that the use of a soundalike voice in Ford advertising for a nostalgic line of cars was a violation of her common law right of publicity under California law (Midler v Ford Motor Co, 1998).Footnote 4 Open AI has since reluctantly withdrawn the soundalike voice (Robins-Early, Reference Robins-Early2024). Further, in Starbucks v Meta Platforms (2025), conservative activist Robby Starbuck successfully claimed defamation against Meta for disseminating false statements about his participation in the capital riot of January 2021, among other false statements, via its chatbot Meta AI, resulting in a settlement (see Starbuck v Meta Platforms, Inc., 2025; Volokh, Reference Volokh2025a). Starbuck has followed up with another complaint of defamation against Google, alleging that the company spread ‘outrageously false’ lies through its AI products (Volokh, Reference Volokh2025b).

Misinformation and disinformation in trade or commerce may also be targeted under consumer protection laws such as the Federal Trade Commission Act (FTCA) in the US (specifically, its § 5 prohibition on ‘unfair or deceptive acts or practices’), the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) of 2010 in Australia (including its s 18 prohibition on misleading or deceptive conduct), and the EU Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD) of 2005 in Europe (see Federal Trade Commission, 2024; Harding, Paterson and Bant, Reference Harding, Paterson and Bant2022; Duivendoorde, Reference Duivenvoorde2025). Fraud may also be claimed in egregious cases.Footnote 5 Already, there are examples. For instance, following the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in 2019 Facebook was fined a record $5b by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for deceiving users about their ability to keep personal information private (FTC, 2019a), and Cambridge Analytica was prohibited from making further misrepresentations (FTC 2019b). A securities fraud claim launched by investors against Mark Zuckerberg and others has also been settled (Associated Press, 2025). The FTC further has responsibility for the US Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) 1998, requiring parental consent for children (under 13 years) to access commercial websites and online services. As such, COPPA in a sense protects children from online misinformation and disinformation, although its remit is much broader. The same may be said of the Australian social media ban for children (under 16 years) in the Online Safety Amendment (Social Media Minimum Age) Act 2024, in force from December 2025.

Data protection laws establishing standards for the processing of personal data may also be relied on to address the generation and spread of misinformation and disinformation within their compasses.Footnote 6 The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) 2016 could well prove to be especially powerful, given its design as a comprehensive modern regime (see Yeung and Bygrave, Reference Yeung and Bygrave2021). Its impact can be seen already in certain cases, including a recent case against Google where the European Court of Justice (CJEU) held that the right of erasure/right to be forgotten in article 17 GDPR may be drawn on to require dereferencing by search engines of ‘manifestly inaccurate’ personal data in breach of article 5(1)(d), under specified conditions (TU and RE v Google LLC, 2022).Footnote 7 But other regimes may also provide important protections, either directly through their accuracy requirements for data processing or indirectly through other standards applied to data processing of personal data. To give just one example, in Illinois, a class action lawsuit launched under the Biometric Information Privacy Act 2008 (BIPA) in relation to Clearview AI’s generation and dissemination of profiles harvested from biometric face images on the internet, for use by Clearview’s commercial customers including in law enforcement, was recently settled (In Re Clearview AI Consumer Privacy Litigation, 2025). Although the non-consensual processing of individuals’ biometric data was the main legal foundation of the BIPA claims, the court noted as ‘not wholly without merit’ the concern expressed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) that ‘numerous studies have shown that face recognition technology misidentifies Black people and other people of colour at higher rates than white people’ leading to ‘higher incidence of wrongful arrest’ (In Re Clearview AI Consumer Privacy Litigation, 2025: 32).Footnote 8

Also worth noting are electoral laws which may be drawn on to deal with current issues of misinformation and disinformation in election contexts. For instance, in Australia, in the lead-up to the May 2025 federal election, the Australian Electoral Commission established under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) launched a ‘Stop and Consider’ campaign urging Australian voters to pause and reflect on ‘information being distributed which is seeking to influence your vote’, to ask questions such as whether it is from ‘a reliable or recognisable source’, and whether it could ‘be a scam’, and stressed the AEC’s role in providing reliable information on the electoral process and in investigating complaints (AEC, 2025; see Grantham, Reference Grantham2025). In other countries, more concrete steps have been taken under existing political advertising laws. For instance, in the US the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) which has responsibility for telephone and broadcast communication, determined that the US Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA) of 1991 extends to telephone calls that use or include AI-generated voices, and in September 2024 fined a political consultant $6 million over robocalls that mimicked President Joe Biden’s voice, urging New Hampshire voters not to vote in that state’s Democratic primary (FCC, 2024a).

The developments discussed earlier suggest that older laws (including some laws that are not all that old and are still being interpreted and updated) will continue to be looked to in this context, as in others. At the very least, they highlight the flexibility of established legal frameworks and doctrines that may be called on to address misinformation and disinformation. In some, perhaps even many, instances they provide a way to address these, while still providing a balance with free speech and innovation.

We now turn to newer laws, which have been designed (at least in part) to deal with misinformation and disinformation, and their associated harms.

1.3 Newer Laws

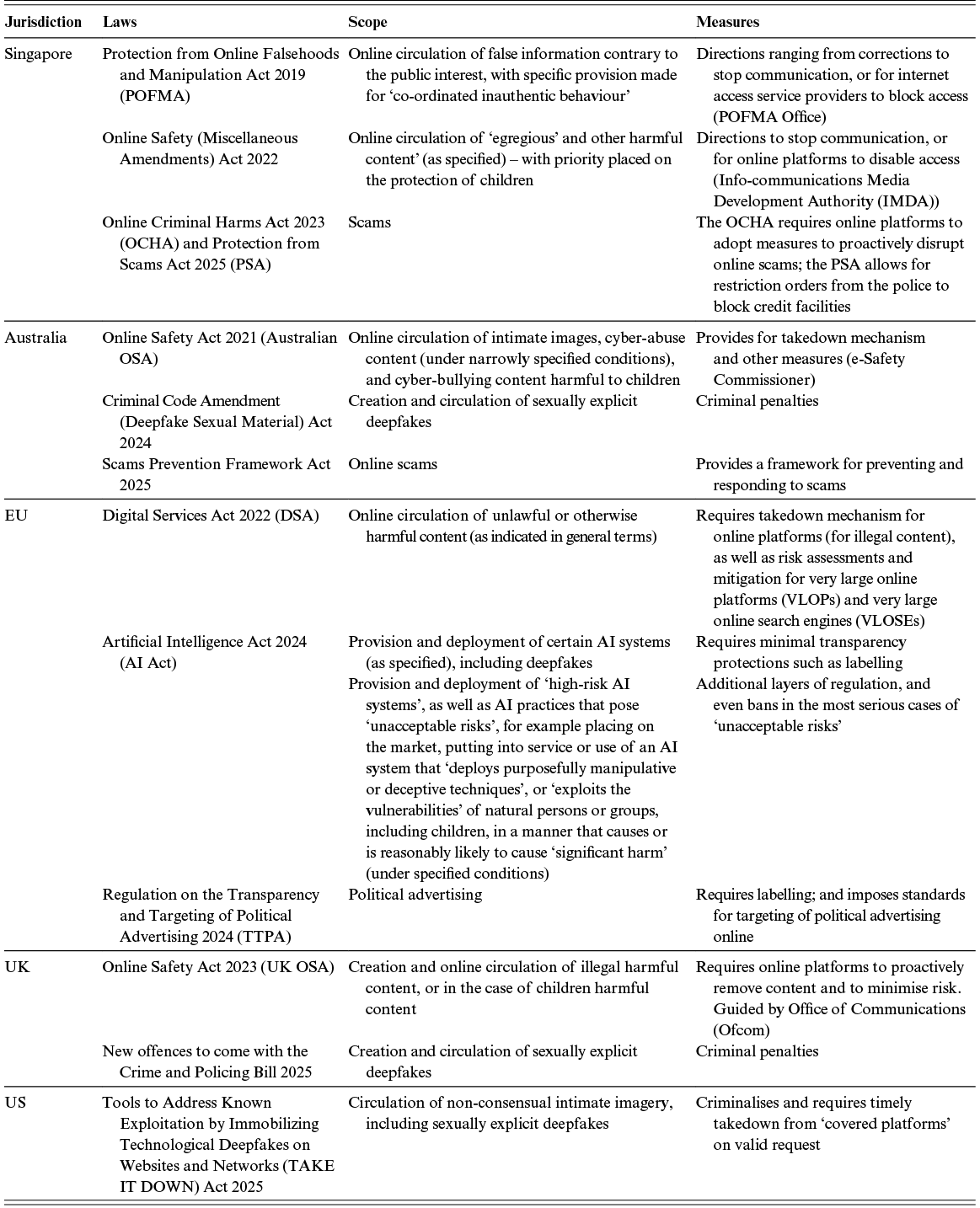

As a preliminary comment, we note that, while most jurisdictions view misinformation and disinformation and their harms as problems that requires a definite legal solution, there is little consistency in terms of the scope and range of the new laws that are emerging (including whether they should be framed in broader or narrower terms, and whether their focus should be primarily on misinformation and/or disinformation, or rather on harm, or on some combination of these) and their balances with freedom of speech and innovation. Table 1 presents examples of legislative initiatives in selected jurisdictions over the last five to six years. We then move on to consider some of the types of harms that these laws seek to address (in either specific terms or as part of a broader sweep), focussing on hate speech, sexually explicit deepfakes, political interference, and scams,Footnote 9 although we still note considerable variations between jurisdictions as to whether, when, and how these should be regulated.

Table 1Long description

This table compares legal and regulatory frameworks across Singapore, Australia, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It contains four columns: jurisdiction, laws, scope, and measures.

Each jurisdiction has several rows listing individual statutes.

In respect of Singapore, laws addressing false information, harmful online content, and scams are listed.

In respect of Australia, laws concerning online safety, sexually explicit deepfakes, and scam prevention are listed.

In respect of the European Union, instruments covering illegal or harmful online content, AI system regulation including deepfakes, and political advertising transparency are listed.

In respect of the United Kingdom, laws on harmful online content and upcoming offences related to sexually explicit deepfakes are listed.

In respect of the United States, a federal act targeting non-consensual intimate imagery, including deepfakes, is listed.

Within each row, the “Scope” column summarizes what the law covers (e.g., falsehoods, minors’ safety, scams), while the “Measures” column describes the enforcement mechanisms such as takedowns, blocking orders, transparency requirements, risk mitigation duties, or criminal penalties.

1.3.1 Hate Speech

Hate speech was an early focus of new efforts at legal regulation, including in Europe, with some adopting strongly interventionist approaches. An example is the now superseded German Network Enforcement Act (or NetzDG, 2017), which required platforms with over two million users to allow users to report content easily, remove ‘manifestly unlawful’ content within twenty-four hours, remove unlawful content within seven days, and produce transparency reports. Following NetzDG, amendments to the Russian Federal Statute ‘On Information, Information Technologies and Protection of Information’ (or the IT Law) and the Code on Administrative Offences were made in 2017, empowering the federal executive body (or Roskomnadzor, part of the Ministry of Digital Development, Communication and Mass Media) to monitor relevant online content, determine whether certain content essential to the public was false, and to obligate news aggregators to stop disseminating such information (Rumyantsev, Reference Rumyantsev2017). Other comparable laws have been identified in Pakistan, Turkey and other countries with various political challenges such as authoritarian governments, persistent challenges with free speech, a lack of competitive elections, or a combination of all three (Meese and Hurcombe, Reference Meese and Hurcombe2020; Canaan, Reference 50Canaan2022).

NetzDG is now superseded by the EU DSA 2022 which adopts an overarching risk-based approach to platform liability for third-party content posted on the platform, paying particular attention to rights protected in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (2000). Specifically, articles 34 and 35 DSA require ‘very large online platforms’ (VLOPs), such as YouTube, LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and X, and ‘very large online search engines’ (VLOSEs), such as Google (article 33 DSA; European Commission, 2025a) to engage in risk assessment and mitigation (Husovec, Reference Husovec2024a, Reference Husovec2024b).Footnote 10 Article 34 requires VLOPs and VLOSEs to conduct ongoing assessments and analysis of their systems, including algorithmic systems, or from the use made of their systems, to identify systemic risks around the dissemination of illegal content through their services, actual or foreseeable negative effects on civic discourse and public security, and negative consequences to a person’s physical and mental well-being. Article 35 obligates VLOPs and VLOSEs to implement a range of tailored measures to mitigate a variety of systemic risks, from adjusting their algorithmic systems (article 35(1)(d)) to adapting their terms and conditions (article 35(1)(b)). Martin Husovec argues that the European Commission did not set out to become a ‘Ministry of Truth’ (Husovec, Reference Husovec2024a: 48), and that the law’s aim was to function as a broader effort to support a positive online ecosystem rather than authorising government actors to restrict specific forms of legal speech, based on their conceptions of harm (Husovec, Reference Husovec2024a: 56). However, on its face, the DSA can regulate content deemed harmful, including hate speech through the risk management and transparency measures it imposes on VLOPs and VLOSEs (and through its required takedown mechanism which is directed at illegal content). On the whole, the DSA offers an interesting co-regulatory model in its efforts to conscript VLOPs and VLOSEs to act as ultimate authorities in the regulation of misinformation and disinformation on these platforms (see generally Husovec, Reference Husovec2024a, Reference Husovec2024b; Kenyon, Reference Kenyon, Krotoszynski, Koltay and Garden2024).

On top of that, the EU AI Act of 2024 adopts a risk-based approach to the regulation of hate speech (along with other types of harmful speech), including hate speech involving misinformation and disinformation generated through AI systems. In brief, while AI systems considered to be low risk are subject to minimal transparency regulation under article 50 of the AI Act, ‘high-risk’ AI systems that are deemed to pose serious risks to health, safety or fundamental rights are subject to higher regulation under articles 6–15. Practices that are deemed an ‘unacceptable risk’ are banned if they fall within the categories listed in article 5 (and meet the conditions specified). Examples include the placing on the market, or putting into service or the use of an AI system that ‘deploys … purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques’ impacting on conduct or decision-making of individuals or groups a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause ‘significant harm’ (article 5(1)(a)), or ‘exploits any of the vulnerabilities of a natural person or a specific group of persons’, such as children, in a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause ‘significant harm’ (article 5(1(b))).

Compare the UK OSA: although its focus, except where children are affected, is illegal harmful speech, there are other UK hate speech laws.Footnote 11 Singapore’s POFMA is framed more broadly in terms of addressing online falsehoods and manipulation in the public interest (see Tan, Reference Tan2022a; Chen, Reference Chen2023), with further protections for children via the Online Safety (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act 2022. The Australian OSA’s protections against circulation of cyber-abuse material directed at adults and cyber-bullying material directed at children likewise catches some hate speech involving misinformation and disinformation.Footnote 12 Moreover, the Australian OSA’s provisions for takedown of non-consensual intimate images (s 35) may be viewed as addressing one particular type of ‘gendered hate speech’ (see Suzor, Seignior and Singleton, Reference Suzor, Seignior and Singleton2017: 1092), and the Criminal Code Amendment (Deepfake Sexual Material) Act 2024 provides further criminal penalties. Likewise, the UK’s Crime and Policing Bill 2025 will introduce new offences covering sexually explicit deepfakes and will further expand the remit of the UK OSA to address what may be viewed as gendered hate speech. The same may be said of the criminalisation of the non-consensual publication of intimate images including sexually explicit deepfakes under the US TAKE IT DOWN Act. Although hate speech has generally not been subject to regulation in the US where the constitutional free speech mandate of the First Amendment is considered to be very broad (Kenyon, Reference Kenyon, Krotoszynski, Koltay and Garden2024; Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025: 947 n 83) and the legal scope for assigning platform responsibility is limited by § 230 CDA, the TAKE IT DOWN Act is an apparent derogation framed for the current environment (see Wihbey, Reference Wihbey2025a).

Such laws reflect the overlap when addressing what may be called ‘gendered hate speech’ with the next category of sexually explicit (and other) deepfakes.

1.3.2 Sexually Explicit Deepfakes

The deepfake non-consensual sexual imagery example is particularly concerning in social terms because, according to some estimates, 90–95% of deepfake videos involve non-consensual pornographic videos and, of those videos, 90% target women (Hao Reference 57Hao2021). Even the US, a country reluctant to regulate misinformation or disinformation based on content due to perceived First Amendment restraints (as well as concerns about the likely impact on innovation), has introduced reforms directly targeting the problem of sexually explicit deepfakes and other intimate visual content posted online without consent in the form of the TAKE IT DOWN Act passed in the Senate in December 2024, in the House in January 2025, and signed by President Donald Trump in March 2025 (Croft, Reference Croft2024; Ortutay, Reference Ortutay2025). The Act criminalises the non-consensual publication of intimate images of an identifiable individual, including specific provisions for ‘authentic visual depictions’ of children and requires measures from ‘covered platforms’ to take down deepfakes and other non-consensual intimate images upon receipt of valid complaints (with the latter coming into effect in May 2026).Footnote 13 Some states have gone further in regulating the production and distribution of deepfake non-consensual sexual imagery. For example, California amended its penal code to criminalise the distribution of ‘photo realistic image, digital image, electronic image […] of an intimate body part […] engaged in specified sexual acts, that was created in a manner that would cause a reasonable person to believe the image is an authentic image’ (CA Penal Code, 2024: § 647(j)(4)(A)(ii)). Numerous other states have followed suit including Washington, Florida and Utah (NCSL, 2024).

Similar trends towards addressing deepfakes can be seen in other jurisdictions, although with considerable variation as to the scope of the laws and the measures deployed. The EU DSA addresses non-consensual circulation on digital platforms of sexually explicit deepfakes through its takedown mechanism (article 16) and may also address a wider range of deemed-to-be harmful deepfakes through its content moderation processes (article 35). The AI Act requires AI deepfakes to be labelled under article 50 and generally adopts an approach that low-risk AI systems are to be minimally regulated through transparency requirements (see Fragale and Grilli, Reference Fragale and Grilli2024), although higher-risk AI systems may be more highly regulated (articles 6 to 15), and practices deemed ‘unacceptable risk’ (under article 5, already in operation) – and this may, of course, apply to some practices involving the use of deepfakes.Footnote 14 In Australia, as noted earlier, the creation and sharing of ‘non-consensual deepfake sexually explicit material’ by individuals has been criminalised under the Criminal Code Amendment (Deepfake Sexual Material) Act 2024 (s 5, substituting s 474.17A of the Criminal Code). Further, the non-consensual sharing of intimate images (including deepfakes) is regulated under the Australian OSA (s 75) and jurisdiction is given to the e-Safety Commissioner to require the images to be removed (s 27 and ss 77–78) and to take proceedings to court for penalties. This power has already been used in one case in Australia, concerning the posting by a Queensland man of deepfake images of high-profile Australian women, and a penalty of $343,500 (Australian dollars) was ordered (eSafety Commissioner v Rotondo, 2025). The UK’s Online Safety Act of 2023 (UK OSA) also provides for penalties, as well as setting out a procedure for requiring online platforms to remove content that is illegal and harmful (or, in the case of children, harmful) under Ofcom’s oversight (ss 2, 10, 12–13, and pt. 7), including with respect to non-consensual sharing of intimate images including deepfakes.Footnote 15 Criminal provisions and penalties to supplement the UK OSA’s regulation are being introduced under the Crime and Policing bill 2025 which will criminalise the making and sharing of intimate deepfakes.

1.3.3 Political Interference

Chesterman notes that an early and still common focus of laws around misinformation and disinformation is ‘on national security broadly construed’ (Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025: 936). There is little general federal regulation of misinformation and disinformation in political advertising in the US, especially in the online environment, with the First Amendment often cited as a reason (see Caplan, Reference Caplan2024; Pasquale, Reference Pasquale and Diurni2025b) and the CDA § 230 another consideration. Regardless, various states in the US have introduced reforms addressing the use of deepfakes and other AI-related misinformation and disinformation in election campaigning (see citizen.org tracker (2025) for a list). Many of these reforms have centred around disclosure and transparency requirements.Footnote 16 For example, in Michigan, New Hampshire and New York (among others), the use of AI in political advertising needs to simply be disclosed. California offered a more systemic response under the Defending Democracy from Deepfake Deception Act of 2024, requiring an online platform to ‘block the posting or sending of materially deceptive and digitally modified or created content related to elections, during certain periods before and after an election’ (NCSL, 2024). However, the latter was struck down in August 2025 for violation of the CDA § 230, without pronouncing on the First Amendment issue (see Spoto, Reference Spoto2025).

Singapore, under amendments to elections laws in 2024, now criminalises ‘the publication of online content that realistically depicts a candidate saying or doing something that … [the candidate] did not’ over critical election periods (see Chin, Reference Chin2024). Singapore’s POFMA has additionally been deployed against (what is deemed to be) misinformation or disinformation in political advertising, drawing on the powers of the POFMA office to issue directions for correction of false statements made or, in more extreme cases, to stop communication of statements or block access to online locations (POFMA, 2019: parts 3 to 6). Because the High Court is precluded from exercising judicial review regarding whether a falsehood undermines public interest, safeguards against the wrongful issuance of directions under POFMA are suggested to be weak (Tan and Teng, Reference Tan and Teng2020). And, more generally, the limited scope to raise free speech concerns has made the regime controversial, with some arguing that at very least its potential for censorship merits further study (Teo, Reference Teo2021).Footnote 17

The EU DSA has also been used to address political interference involving misinformation and disinformation, and the results have also proved to be controversial. For instance, in early 2024, the European Commission required digital platforms to show how they plan to address deepfakes, following evidence of Russian interference in elections (O’Carroll and Hern, Reference O’Carroll and Hern2024). Later, in December 2024, the Commission followed up with formal proceedings against TikTok to investigate whether the platform appropriately managed electoral risks in Romania after the failed election there, alongside allegations of interference (using TikTok) by Russia (Albert, Reference Albert2024; Radu, Reference Radu2025). The political consequences of the revelations were felt in the May 2025 election, with the online space in the period leading up to the election becoming mired in ‘personal attacks, fear-driven messaging, and fake narratives targeted [the eventual elected candidate] Nicușor Dan’, much of which was fuelled by AI (Radu, Reference Radu2025). As Roxana Radu puts it, ‘[w]hile Dan’s victory signals resilience in the face of digital manipulation, it also reflects a broader protest vote – a desire to move past the political paralysis and digital toxicity that defined the last six months’ (Radu, Reference Radu2025). And, although the DSA represented ‘a step in the right direction’, the Commission’s investigation was ‘slow, even for accelerated procedures, like the one opened for the annulled Romanian elections in December 2024’, whose conclusions were still awaited in May 2025 (Radu, Reference Radu2025).

Some legal support for addressing systemic misinformation and disinformation risks in political advertising involving AI systems may also now be found in the EU AI Act’s bans on AI practices posing ‘unacceptable risks’ (article 5), requirements for AI systems classified as high-risk (articles 6 to 15) and labelling inter alia of AI-generated deepfake content (article 50). Another potential source of regulation is the EU Regulation on the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising 2024 (TTPA) (in effect October 2025). At minimum, this states, political advertising must be labelled and further standards apply for targeting of political advertising online (European Commission, 2025b). Finally worth noting is the increasing use of foreign interference laws inter alia to address the problem of ‘misinformation and/or disinformation and … foreign intelligence’ (Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025: 958).Footnote 18

1.3.4 Scams

In addition to general consumer protections and protections against fraud discussed earlier, scams – or, as Chesterman puts it, ‘targeting individuals for the purposes of fraud’ – are becoming a focus under the new laws (Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025: 938). For instance, the UK OSA extends to scams as a type of harmful (and illegal) disinformation. Likewise, scam-related disinformation is covered under the EU DSA, and (as noted earlier) the AI Act regulates AI aspects.Footnote 19 Australia now has specific far-reaching provisions for scams including in the online environment, with the passing of the Scams Prevention Framework Act 2025 (Cth). Among other things, this empowers the ACCC to ‘closely monitor’ regulated entities’ compliance with Act’s ‘principles to prevent, detect, disrupt, respond to and report scams’, and to enforce the digital platforms sector scams code established under the Act (ACCC, 2022). Singapore also treats scams as a particular subject for intervention (Tang, Reference Tang2025). We have already noted POFMA as a tool to combat online misinformation and disinformation in the public interest, and this applies equally to scams. The Online Criminal Harms Act of 2023 also addresses online scams and obliges online platforms to implement measures to proactively disrupt online scams, including removing scam content upon detection (MDDI, 2024). And Singapore’s new Scams Act of 2025 allows inter alia for the addressing of scams via restriction orders issued by the police to block credit facilities.

By contrast, in the US efforts to impose obligations on platforms to deal with scams (beyond reliance on the consumer protection provision of the FTCA) would potentially run counter to § 230 CDA, although this may be less so if the platform is viewed as involved in contributing materially to the scam.Footnote 20 As to the potential impact of First Amendment when it comes to attempts to regulate scams more generally, as Mark Goodman puts it, although commercial speech and especially false speech is less protected under the First Amendment, ‘[f]ree speech now means protections sometimes for … scams’ (Goodman, Reference Goodman2023; see also Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025: 947 n 83).

1.4 Summary

This section has considered some of the new legislation addressing misinformation and disinformation and their associated harms. As we have seen, there are significant differences between these jurisdictions, with the EU adopting a much more expansive approach in terms of the types of conduct and harms being addressed than the US, and a third group (UK, Australia and Singapore) coming in between. Further, the variations between the jurisdictions surveyed reflect not just different conceptions of what harms should be addressed, and how they should be addressed, but also different balances found with (among other things) freedom of speech and innovation. In particular, the narrow scope of legal regulation of misinformation and disinformation in the US compared to the broader, more open-ended and proactive legal regulation in (most) of the other jurisdictions surveyed, and especially the EU, suggest some very different balances between freedom of speech and innovations in these jurisdictions. This conclusion is reinforced by the recent publication of the US (Republican led) House of Representatives Staff Report characterising the EU DSA as a ‘powerful censorship law’ (US Judiciary Committee Staff Report, 2025: 2, 15).Footnote 21 While this may be regarded as an extreme statement of the US position on freedom of speech and innovation, there can be little doubt that (as Chesterman puts it) the US ‘is somewhat of an outlier in this area, with strong First Amendment protections covering speech that would be unlawful in many other jurisdictions’ (Chesterman, Reference Chesterman2025: 947, footnote 83).

Such divisions discussed earlier suggest that much of the work in addressing the harms of misinformation and disinformation, which anyway often operate across national and regional boundaries with little regard to law, will (continue to) fall to platforms and their practices, including their uses of technologies, and to broader social measures. Indeed, in our view, one of the strengths of the EU DSA, as explored further in the following section, is its acknowledgement of the value of these alternative modalities.

2 Platforms Using Technologies

2.1 Content Moderation

As our previous section has shown, despite the extensive and highly variable amount of legal regulation focussed on addressing harmful misinformation and disinformation in many jurisdictions, which may be underpinned by different conceptions of rights, there are normative and practical limits to legal intervention. Further, even where there are laws in place, the scale and scope of online content distribution has meant that jurisdictions are increasingly turning to self-regulatory or co-regulatory frameworks that necessarily require the assistance and input of platforms. As a result, it is impossible to discuss the current state of misinformation and disinformation regulation without considering the complex and often-technical system of content moderation that shapes our contemporary online environment. Indeed, one thing that is particularly notable about content moderation today is the way that AI is being employed to detect misinformation and disinformation and suppress its distribution. We outline these developments in this section and highlight an alternative narrative around AI, where the technology is cast as (at least part of) a solution to the misinformation and disinformation problem as opposed to the cause. While we are equally sceptical of claims that AI can solve all of these challenges, a claim often circulated by self-interested platforms, our examples allow us to assess the extent to which developments around AI can help address a significant policy issue.

The section also examines key normative questions about the challenges associated with private regulation of speech, in particular deploying technical systems, sometimes in conjunction with human fact-checkers. Of course, the absence of law does not entail the absence of regulation or intervention. And nor does the presence of law necessarily determine the amount of regulation that goes on. It is quite commonly being done privately on platforms anyway, with much less accountability and oversight – although Meta’s Oversight Board presents a notable exception here. While this argument about lack of accountability and insight has been made many times (Balkin, Reference Balkin2018; Gillespie, Reference 56Gillespie2018b), we have chosen to highlight Michael Davis, a scholar and former public servant who was involved in the development of Australia’s self-regulatory framework around misinformation and disinformation. He notes that without establishing wider regulatory infrastructures, content moderation is left to platforms who become ‘the arbiters of truth’ (Davis, Reference Davis2024). We build on this useful critique and suggest that in many cases, these tensions around regulation point to the need for a more sophisticated infrastructure around platforms, involving efforts such as researcher data access and platform observation.

The section proceeds as follows. First, we introduce and define what we mean by content moderation. In the process, we sketch out how AI and other technologies such as blockchain are being deployed by platforms. Second, looking forward, we discuss experimental and scholarly work directed at the capacity of these technologies to detect or address harmful misinformation and disinformation, either by themselves or in conjunction with human fact-checkers – using examples of detecting deepfakes and automated fact-checking to further explore the interventions. Finally, we end with a reflection and development of our argument, addressing what we set out at the beginning of this Element, as well as those views outlined in this section.

2.2 Definitions, Tools and Techniques

The term content moderation refers to a range of practices that digital platforms employ to manage the constant stream of messages, pictures, videos, articles and other forms of content that are published online along with any interactions that occur. One of the most productive and expansive definitions of the term is provided by Gillespie et al. (Reference Gillespie, Aufderheide and Carmi2020) who describe it as:

[T]the detection of, assessment of, and interventions taken on content or behaviour deemed unacceptable by platforms or other information intermediaries, including the rules they impose, the human labour and technologies required, and the institutional mechanisms of adjudication, enforcement, and appeal that support it.

From the earlier description, the centrality of private power is made clear. The practice of content moderation emerges from and is shaped by the terms and conditions of platforms as well as any associated guidelines (although legislation can inform these rules). There is also a brief nod to the significant emotional and physical labour that moderation can involve, given its reliance on human beings as well as technical systems (Gillespie, Reference Gillespie2018a; Roberts, Reference Roberts2019). While promotion of safety, or alleviation of harm, emerges as an obvious lens through which to view moderation, it is deployed for a range of reasons including managing the spread of misinformation and disinformation. A range of techniques are used to moderate content, and it is worthwhile briefly noting these before turning our focus to the (seemingly) cutting-edge misinformation and disinformation detection technologies promoted as part of the wider AI moment.

Even though the entire goal of content moderation is to anticipate issues and remove problematic content before it is even published on the platform, the large volumes of content posted online every day inevitably continues to cause concern amongst audiences. In response, people are encouraged to ‘flag’ content that concerns them, which refers to the act of a person using platform tools to report content through the ‘predetermined rubric of a platform’s […] community guidelines’ (Crawford and Gillespie, Reference Crawford and Gillespie2016: 411). The practice on its own raises significant concerns as people can use the tool to silence or harass ‘users that are already vulnerable to platforms’ censorship, such as sex workers, LGBTQIA+ and sex-positive users, activists and journalists’ (Are, Reference 48Are2024) – to highlight just a few affected demographics.

Another strategy is labelling, which sees potentially controversial or inaccurate content identified as such. In some cases, this may be a fact-check (more on this aspect later), but labels can also include ‘a click-through barrier that provides a warning, a content sensitivity alert, or the provision of additional contextual information’ (Morrow et al., Reference Morrow, Swire-Thompson and Montgomery Polny2022: 1365). One example of the latter is the addition of a ‘forwarded’ label on WhatsApp messages, in an effort to add further context around viral misinformation or spam (Morrow et al., Reference Morrow, Swire-Thompson and Montgomery Polny2022). X (formerly Twitter) also may label content that is ‘significantly and deceptively altered, manipulated, or “fabricated”’ (Authenticity, 2025). Other digital platforms such as Meta, TikTok and YouTube require users to label AI-generated and manipulated content. There are also growing plans to incorporate content credentials (i.e., metadata that are cryptographically attached to digital content to provide verifiable trails of the content’s origins and edits) on their platforms (Soon and Quek, Reference Soon and Quek2024). C2PA is the most visible initiative with a range of key players, from Adobe and Microsoft to BBC and Sony. Other efforts include Open AI ensuring that images generated by their DALL-E 3 model contain metadata. These efforts go beyond classic concerns associated with content moderation and highlight an emerging problem space around ensuring the provenance of content and identifying the presence of synthetic media (Soon and Quek, Reference Soon and Quek2024). While labelling for different purposes has become more prominent across a variety of platforms, the overall efficacy of the intervention is still uncertain (Morrow et al., Reference Morrow, Swire-Thompson and Montgomery Polny2022; Peters, Reference Peters2023). Still, it presents a potentially useful first step to addressing harms.

Labels do not happen in isolation, with various platforms often seeking to additionally reduce the visibility of labelled content amongst the wider audience. While removal had long been seen as the preferred outcome from content moderation efforts, there are increasing concerns about the potential for ‘backfire effects’ (Nyhan and Reifler, Reference Nyhan and Reifler2010) where motivated users posting and sharing misinformation become emboldened because of enforcement efforts, which to the targeted individual can feel like censorship. In response to this, platforms are starting to restrict the circulation of suspect content (often called ‘borderline content’) without removing it from the platform (Gillespie, Reference Gillespie2022; Zeng and Kaye, Reference Zeng and Kaye2022; Are, Reference 48Are2024). The removal of, or restriction of access to, content identified to be false, altered, unverified or harmful, or user accounts propagating such content by digital platforms such as TikTok, Meta and YouTube is arguably done in pursuit of the goal of responsive protection (Soon and Quek, Reference Soon and Quek2024). Once again, these efforts do not always solely focus on issues such as misinformation and disinformation. For example, the approach has allegedly been used by TikTok to restrict the visibility of certain types of content related to the Black Lives Matter movement, developmental disorders (such as autism) and unattractive individuals (Zeng and Kaye, Reference Zeng and Kaye2022). Along with these efforts, platforms may stop people from engaging with selected content, or creators from monetising their content by, for example, placing advertisements against their posts. With creators rarely told about these interventions, the term ‘shadow-banning’ (or reduction) has become a commonly used term to describe this form of moderation (Gillespie, Reference Gillespie2022; Are, Reference 48Are2024).

Indeed, once we get past interventions like flagging that involve human effort, technical systems and interventions that are commonly referred to as AI starts to enter the picture. Machine learning systems are regularly used to support the shadow-banning (or reduction) methods described previously. The effort involves the use of natural language processing, which relies on supervised training, clean datasets and structured systems to produce predictions. We outline these details to point out the differences between these carefully constructed models, as well as the open and adaptive nature of generative systems like ChatGPT. As Robert Gorwa and colleagues go on to explain, these systems can be used to ‘predict whether text may constitute hate speech, and based on that score, flag it for human review’ (Gorwa, Binns and Katzenbach, Reference Gorwa, Binns and Katzenbach2020). In a similar fashion, misinformation and disinformation can be identified by using machine learning to extrapolate from a massive database of ratings produced by human classifiers (Gillespie, Reference Gillespie2022).

In general, content moderation has always involved the use of technical systems to a greater or lesser extent. The introduction of machine learning has simply resulted in different technical capabilities being made available to both platforms and the human moderators, who are still deeply involved in the overall enterprise. Given this track record, it is perhaps no surprise that one of the most human-intensive misinformation and disinformation interventions – fact-checking, which requires working fact-checkers to develop detailed assessments of incorrect information – is starting to engage with AI technologies. Various platforms collaborate with fact-checking organisations to better identify and correct misinformation and disinformation. Google and YouTube have provided funding to the International Fact-Checking Network to ‘increase the impact of fact-checking journalism’, and Meta famously introduced a third-party fact-checking programme, which has funded a significant number of fact-checking institutions currently in operation (Watt, Montaña-Niño and Riedlinger, Reference 68Watt, Montaña-Niño and Riedlinger2025). The most notable deployment was around COVID-19, which saw concerns about the quality of information circulating online become particularly pressing. Conspiracies about how the virus is transmitted, as well as the quality and efficacy of the vaccines, spread like wildfire – in response, platforms were pressured to ensure that official communications were prioritised. Extra initiatives were taken by platforms, demonstrating their stronger commitment to combat misinformation and disinformation over the pandemic, as well as their support of the vaccination programmes (Tan, Reference Tan2022a, Reference Tan2022b). For example, both platforms X and Google worked with public health authorities like WHO and the respective health ministries in many countries to review health information on the pandemic and to ensure that credible information is accessible.

Looking forward, there is an increasing perception in technology quarters that some elements of fact-checking – although perhaps not the whole role – may be able to be automated using AI. This raises the following questions: How close are we to a world where ‘corrections’ are automated, and what are the ethical limitations of moving to this approach?

2.3 From Fact-Checkers to Fact-Bots?

Fact-checking originally started in the early 2000s as a way of correcting the record in political debate, challenging the wordsmithing and obfuscations of statements and claims made by politicians. These efforts were originally located on dedicated websites like FactCheck.org, before gradually spreading across the wider institution of journalism. Various established newsrooms launched their own fact-checking operations, often for election periods; new fact-checking organisations started to appear across the world, with a particular boom period noted in the early to mid-2010s (Graves, Reference Graves2018; Vinhas and Bastos, Reference Vinhas and Bastos2023). Funding and support for the practice boomed following the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Not only did Trump make a habit of verbally disparaging the press and making wild and inaccurate claims, but as noted earlier, there was evidence of Russian interference in that US election. As part of this period of growth and transition, fact-checking became embedded in the wider content moderation process across various platforms (Vinhas and Bastos, Reference Vinhas and Bastos2023).

It is worth repeating that fact-checking is not (and has never been) wholly free from automation, AI or other technical advances. To pick one leading example from the technology sector, Meta’s third-party fact-checking programme, which has been switched to a ‘community notes’ system in the US,Footnote 22 embeds fact-checkers in systems and processes. The standard process involves human fact-checkers accessing a stream of content that Meta’s system has identified as misinformation and disinformation. Accredited fact-checking organisations then selected pieces of content to fact-check, and label the content accordingly as ‘false, altered or partly false’ or ‘Missing context’ (Meta, 2025). As an interesting aside, the organisations earn revenue from Meta for the completed tasks, which has turned the technology giant into one of the major funders of fact-checking more generally (Watt, Montaña-Niño and Riedlinger, Reference 68Watt, Montaña-Niño and Riedlinger2025).

Nevertheless, as with many other sectors, questions are being raised about whether human labour can be augmented (or even replaced) with AI. Fact-checking – like all journalism – takes a significant amount of time. Phone calls need to be made, information must be sourced, and details must be confirmed and re-confirmed before publication. The question is whether automation and AI can help do this within a shorter time and at lower costs. Many platforms are relying on algorithmic moderation and promoting authoritative sources, rather than deleting misinformation which could reflect alternative viewpoints or constitute legitimate dissent. As a result, these platforms are making certain disputable or contestable content less visible, rather than removing it completely, hence allowing for different perspectives to be shared while reducing the viral potential of what could be harmful falsehoods (see Cademix, 2025).

Discussions around efficiencies are a common feature of debates around AI and the labour market, and it is no surprise that we find them circulating around fact-checking (OECD, 2021). For one, these tendencies align with the natural philosophical orientation of technology firms raised in the ashes of the ‘Californian ideology’ (Barbrook and Cameron, Reference Barbrook and Cameron1996) – one centred around optimism and technological determinism – to embrace technical solutions over socio-technical interventions. However, the sort of policy discourses we set out in the opening of this Element have also added to the perceived sense of crisis and the need for automation. If there is a misinformation and disinformation crisis on our hands, and Generative AI is going to lead to even more error-strewn or conspiratorial information circulating online, then an argument can be easily made that these issues are no longer able to be managed by purely human interventions. These fact-checking specific debates also fit into a much a wider narrative around content moderation and scale (Gillespie, Reference Gillespie2020) which both invokes and demands AI and automation as some sort of solution to managing the significant amount of content online. Early evidence, however, reveals that AI is being used increasingly as a way of augmenting fact-checking work, rather than replacing it entirely.

Critical work is still being done in universities, with researchers actively experimenting with technology to better understand how AI can assist fact-checkers. In a literature review on what they call automated fact-checking (AFC), Dierickx and colleagues (Reference Dierickx, Lindén and Opdahl2023) identify four different areas where AFC may be valuable: finding claims, detecting already fact-checked claims, evidence retrieval and verification. Guo and colleagues (Reference Guo, Schlichtkrull and Vlachos2022) offer a broadly similar framework but go further in outlining the specific technologies involved. For example, they describe the growing use of neural networks to help identify whether a particular claim is worth checking. The ability to incorporate additional context around the claim is incredibly beneficial, when compared to previous classification efforts which had to rely on fixed features, such as up-votes or named political entities such as parties or politicians. Other efforts have seen LLMs increasingly used to identify the veracity of certain claims. However, because AI systems are dependent on the datasets upon which they are trained – a phrase which has become something of a truism in recent years – the ability of AI to detect false information may be limited.

For the success of these systems, what is considered to be misinformation and disinformation to be censored must be agreed on. One significant shortcoming is the over-blocking of lawful content by AI through its over-inclusivity, henceforth potentially negatively affecting the freedom of expression through censorship of reliable content (Kertysova, Reference Kertysova2018). In the same vein, the systems also appear to be inaccurate, with Das and colleagues (Reference Das, Liu, Kovatchev and Lease2023) noting that ‘even the state-of-the-art natural language processing models perform poorly on […] benchmarks’, referring to the capacity of models to accurately detect claims worth checking.

Although the deployment of automation including especially AI in the context of fact-checking is still in its infancy, there is a growing effort to use the technology to assist both content moderation directly, as well as support downstream efforts in fact-checking organisations. As might be expected, the other area where AI is being deployed with a view to supporting content moderation in the future is in relation to deepfakes, where a similar tale of experimental academic research and gradual industry engagement is occurring. Both of these examples are discussed further in the following section.

2.3.1 Detecting Deepfakes

Certain sub-disciplines in computer science have started to focus some of their efforts on the detection of deepfakes with the support of industry. Meta ran a Deepfake Detection Challenge in 2019, and Google has released a dataset of deepfake videos to support research efforts in the field (Meta, 2020; Dufour and Gully, Reference Dufour and Gully2019). Platforms are also keen to promote their detection abilities across their products, with Meta changing their Facebook policies in preparation for the US election, going so far as to label ‘digitally altered media’ that was likely to have an impact on the public’s interpretation of the campaign (Paul, Reference Paul2024). The way that technology companies communicate about these initiatives can imply that deepfake detection is a solved problem, and something that can easily be incorporated into existing content moderation routines. However, the technical capacity to detect manipulated media is still developing with efforts directed to improve state of the art methods.

Before exploring the process of deepfake detection, it is worth talking about exactly what AI manipulation looks like. As we already know, deepfakes can be image, video or audio based and can be deployed in several ways. For example, an audio deepfake might get a celebrity voice to conform to a particular script or alternatively, prerecorded audio might be amended to sound more like the celebrity (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Tanwar, Gupta and Bhattacharya2023). Similarly, an image might be entirely AI-generated or combine two or more photos into a new context. These descriptions are really scene-setting – what is most critical for detection is understanding minor changes that can still be discernible. For example, if the lighting in a static image is changed, detection might involve ‘analysing the image’s metadata [or] searching for inconsistencies in the image’s pixels or patterns’ (Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Noori Hoshyar and Saikrishna2024). With videos, it can be more productive to look for ‘visible inconsistencies’, such as an ‘inconsistent head pose’ or a strange ‘blinking pattern’ (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Tanwar, Gupta and Bhattacharya2023).

Some of these identification methods can be achieved through a dedicated visual check or through basic open-source tools, that support operations like metadata analysis. However, the vast majority of deepfake detection methods rely on AI – and more specifically deep learning – for reasons of scale and efficiency. Like most forms of deep learning, this involves training an AI model on datasets to identify ‘patterns, anomalies, or inconsistencies’ through statistical analysis, prediction and identification (Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Noori Hoshyar and Saikrishna2024). The dataset used by Facebook’s Deepfake Detection Challenge provides some insight into the scale and type of data being used by these models. It contained ‘128,154 videos sourced from 3,426 paid actors’ and featured ‘104,500 fake and 23,654 real videos’, with videos recorded in various lighting conditions (Stroebel et al., Reference Stroebel, Llewellyn and Hartley2023). A research team would build a model to be trained on this dataset (or perhaps another one), and then focus on statistically identifying inconsistencies or errors. While we have already noted some, a particularly fascinating example comes from Agarwal and colleagues, who have found that deepfake videos do not effectively reproduce mouth shapes (or visemes). While the mouth should completely close to pronounce words using the letters M, B and P, this does not happen in deepfake videos. To address this issue, they trained a neural network to identify whether ‘a mouth is open or closed in a single video frame’ (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Farid, Fried and Agrawala2020). Additional complications are presented by developments in synthetic imagery. It is important to note that the tools mentioned earlier were already struggling with simple face swaps, and synthetic media has developed significantly since then.

Available deep learning models perform well on the datasets they are trained on, but there is still a difference between what success looks like and the realities of content moderation. The winner of the Deepfake Detection Challenge won with an accuracy of 82.56% – while impressive, this still represents an almost 20% error rate. Indeed, although various detection models function reasonably well on the datasets they are trained on, they still perform poorly in the wild, when assessing deepfakes they have not come across before (Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Noori Hoshyar and Saikrishna2024). For example, the winning Detection Challenge model’s success rate went down to 65.18% when tested against a black box dataset (a dataset where no-one knows what’s in it). As a result, as Stroebel and colleagues note, while these models report ‘high performances in these metrics when trained, validated, and tested on the same dataset’, they are not generalisable, and therefore are not ‘equipped to handle real-world applications’ (Stroebel et al., Reference Stroebel, Llewellyn and Hartley2023).

There are also adjacent challenges associated with computational resources and diversity. On the first issue, developing increasingly complex models in the search for accuracy can be beneficial from a technical perspective, but little consideration is given to the length of time associated with deepfake detection (Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Noori Hoshyar and Saikrishna2024). A balance between accuracy and efficiency will need to be achieved before any detection systems can be integrated into existing content moderation systems. On the topic of diversity, dataset availability and composition remain a critical issue with respect to detection. There can be significant shortfalls of key demographics in available visual datasets, which has led to the introduction of specific datasets to address the issue, like the Korean Deepfake Detection Dataset to improve knowledge of Asian facial features. However, some other notable gaps remain, like the ‘limited amount of available full-body deepfake data’ (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Nebel, Greenhill and Liang2024). There is also a continuing focus on visual deepfakes, whether they be image or video, with a noticeable absence of studies looking at synthetic audio (Stroebel et al., Reference Stroebel, Llewellyn and Hartley2023). When audio deepfakes are considered, the vast majority of studies focus on the English language (Dixit, Kaur and Kingra, Reference Dixit, Kaur and Kingra2023).

2.3.2 Automated Fact-Checking

Looking beyond deepfake detection, we are also seeing evidence of augmentation with AI tools in automated fact-checking practice. US-based fact-checking unit, PolitiFact, ‘uses a large database of claims, called ClaimReview, to detect what a politician says in a video, match it to a previously published fact-check, and display the relevant fact-check onscreen’. While the process is not without error, Professor Bill Adair – the founder of the organisation – describes the benefits of ‘instant fact-checking’ (Abels, Reference Abels2022). Snopes have developed a chatbot, establishing a large language model based on their archives, which allows people to ask questions about rumours (Richmond, Reference Richmond2024).

Deepfake detection can be said to be less progressed than automated fact-checking, with limited incorporation into existing content moderation efforts. That being said, these trends do collectively point to something of an arms race, with various AI capacities being developed in response to an anticipated increase in misinformation and disinformation.

2.4 Technical and Ethical Limitations

As mentioned earlier, AI systems are technically dependent on the datasets upon which they are trained, and its capabilities in detecting false information can be limited. Hence, it becomes imperative for the training dataset: to be large enough so that it can be adequately reflective for the AI to differentiate between false information and truth; to be updated regularly to counter new campaigns; and to contain text accurately labelled as false content (Marsoof et al., Reference Marsoof, Luco, Tan and Joty2023). Ascertaining which content is false can be hard, since online content may contain a mix of true, false, as well as true but misleading claims. Further, there may be opinions, speculations and predictions not intended by the author to be assertions of fact. These subtle differences both between what is true and what is false or misleading, as well as what are opinions and facts can only be identified with linguistic competence and background knowledge of more complex topics (Brasoveanu and Andonie, Reference 49Brasoveanu and Andonie2021), which trained AI may not have at hand. Prior studies have also demonstrated that reliably labelled datasets of false information are hard to come by (Asr and Toboada, Reference Asr and Taboada2019). Therefore, notwithstanding the promise of automated techniques, algorithmic moderation has the potential to exacerbate, rather than relieve, several key problems with content policy.

There are several tensions that need to be resolved. For example, when the removal of content by a ‘fallible’ human moderator is associated with scientific impartiality, it allows online platforms to both justify replacing people with automated systems as well as keep their decisions non-negotiable and non-transparent (Crawford, Reference Crawford2016). This worsens the problem that content moderation is infamously seen to be an opaque and secretive process (Gillespie, Reference 56Gillespie2018b; Flew, Suzor and Martin, Reference Flew, Suzor and Martin2019). The absence of a human-in-the-loop in fully automated decision-making systems is a dangerous progression. To elaborate on what has been said earlier, because machine learning is notoriously poor at making difficult context-dependent decisions, automated systems could both over-block important forms of expression, or under-block such content (including harmful content), thereby not protecting informational integrity either way. Having people in the loop moderates this risk and limitation of AI. As algorithmic moderation becomes more seamlessly integrated into regular users’ daily online experience, the reality behind the use of automated decision making in content moderation must continue to be questioned, so that online platforms remain accountable to the public and engaged with crucial content policy decisions (Gorwa, Binns and Katzenbach, Reference Gorwa, Binns and Katzenbach2020).

Unfortunately, some AI systems like large language models are unexplainable (or at least very difficult to explain), involving sophisticated layers of architecture that are almost impossible to analyse and explain – they are hence frequently referred to as ‘black boxes’ as there is little insight into how they are coded, what datasets they are trained on, how they identify co-relations and make decisions, as well as how accurate and reliable they are (Pasquale, Reference Pasquale2025a). If users do not understand why their content is removed due to the lack of transparency, accountability and explainability in platforms’ content moderation policies, their trust in online platforms may be eroded, together with their ability to challenge takedowns, thereby impacting on these users’ rights to online speech (Fischman-Afori, Reference Fischman-Afori and Schovsbo2023; Marsoof et al., Reference Marsoof, Luco, Tan and Joty2023). It has been suggested that some implementations of algorithmic moderation techniques threaten to: decrease decisional transparency, through making non-transparent practices even more difficult to understand; complicate outstanding issues of justice (with respect to biases and how certain viewpoints, groups or types of speech are privileged); as well as obscure the complex politics that underlie the practices of contemporary content platform moderation (Gorwa, Binns and Katzenbach, Reference Gorwa, Binns and Katzenbach2020). Given these critiques it has been suggested that the use of content-filtering AI should always be subject to mandatory human review (i.e. a human-in-the-loop), particularly in high-risk and low-accuracy scenarios (Marsoof et al., Reference Marsoof, Luco, Tan and Joty2023). And, to further improve accuracy, datasets relied on to train such AI should contain articles which are individually labelled by people with expertise on the topic of these articles (Asr and Toboada, Reference Asr and Taboada2019).

Digital platforms are making some efforts to improve the accuracy of AI systems. For instance, platforms like YouTube are partnering with external evaluators and using their inputs as training data for machine learning systems to build models that review large volumes of videos to detect harmful misinformation and disinformation. OpenAI has been working on developing detection classifiers to evaluate the likelihood that the content is AI generated (Soon and Quek, Reference Soon and Quek2024). Additionally, given the challenges of AI-based systems in understanding subtler forms of human expression and contextual cues beyond explicit content, such as sarcasm and irony that can give content further meaning (Santos, Reference Santos and Carrilho2023), the approach of semi-supervised learning – involving people in the text analysis process to develop AI tools for the automated detection of misinformation and disinformation – may ameliorate these difficulties and further help to improve the accuracy of such tools. Similarly, involving people in the actual detection of misinformation and disinformation may circumvent the challenges faced with respect to the accuracy of textual analysis programmes in identifying misinformation and disinformation, due to the difficulty of parsing complex and sometimes conflicting meanings from text (Marsden and Meyer, Reference Marsden and Meyer2019).

Additionally, while no longer seen as especially viable, blockchain technology has also been considered as a method of verifying the authenticity of digital content. Blockchains can provide a transparent and immutable record of authenticity. Examples of initiatives that use blockchain to combat misinformation and disinformation include the News Provenance Project, Fake Check and Democracy Notary. The New York Times, for instance, conducted a project to provide provenance metadata around news, using blockchain technology to track the dissemination and provide contextual information to readers of online news (Santos, Reference Santos and Carrilho2023). Separately, there are initiatives such as the DeepTrust Alliance which verifies the provenance and authenticity of digital content (through metadata), as well as WeVerify’s Deepfake Detector which maintains a public database of known fakes and uses blockchain to scrutinise social media and web content for disinformation and fabricated content (Harrison and Leopold, Reference Harrison and Leopold2021). As Fátima Santos concludes after an exhaustive study, combining blockchain technologies with AI’s capacity to analyse large volumes of content in real time can result in a more efficient system against misinformation and disinformation (Santos, Reference Santos and Carrilho2023). At the same time, she does not suggest that these tools can provide a complete solution, arguing rather that ‘the fight against disinformation requires a multifaceted approach that involves not only the use of AI and other technological tools but also human verification’.

2.5 Value and Limits of Technical Regulation

There are ongoing normative debates about the role that private entities should play in the regulation of private speech (Klonick, Reference Klonick2017; Balkin, Reference Balkin2018; Gillespie, Reference Gillespie2018a; Santos, Reference Santos and Carrilho2023). As Davis and Molitorisz put it (Reference Davis and Molitorisz2025: 3), ‘platforms are largely to control the dissemination of content on their services, and this lies at the heart of their market offering […] and their moderation of content often exhibits arbitrariness, inconsistency and deference to power rather than rights’. While we have been emphasising the tools available to platforms to address misinformation and disinformation in this section, our comments highlight the limits of leaving the choice whether to do so, or not, to private actors – whose practices may vary sharply, shaped by corporate goals of maximising user engagement and profit or political changes, and whose ideas about what and how misinformation and disinformation should be regulated may also be very different from those of their own communities.Footnote 23 Indeed, even where decisions made by platforms seek to address misinformation and disinformation, technical tools may still be insufficient, especially if the end goal is alleviation of harm and/or vindication of some idea of rights. They may also be controversial. For instance, the use of AI and technological tools in fact-checking and content moderation processes often face technical and ethical challenges.

The question we now turn to is whether, given our arguments that reliance on law, and even platforms and their technologies will not be enough to address the harmful effects of misinformation and disinformation in balance with freedom of speech and innovation, social interventions can assist.

3 Building Social Resilience

3.1 Beyond Law and Technology

In this section we outline the important role of tools and approaches which are predominantly social. We are mindful not just of the harms which are already being identified with misinformation and disinformation, including those being targeted by various laws (as discussed in Section 1) or highlighted in the moderation of platforms (as discussed in Section 2), but the need to build general social resilience so as better to head off future harms. The idea that tackling misinformation and disinformation for the future requires ‘a comprehensive or total defence system, in which every individual and organisation should play a role, including as checks and balances in the overall information ecosystem’ is not a new idea (see, e.g., OECD 2024: 74). But what is needed is a fuller understanding of the predominantly social tools and approaches that might be adopted within that system.