This paper presents a typology of occupation-related volunteering where an individual’s occupational competencies and resources are necessary for their volunteer role. Drawing on the employment literature (see Meijs et al., Reference Meijs, Ten Hoorn and Brudney2006), it uses employability––the personal characteristics, circumstances and external factors affecting employment––to explore the intersection with their volunteerability––the availability, willingness, and ability to volunteer. Occupations are socially constructed groups. They define a category of work and individuals as practitioners of the work, enacting the role of an occupational member and the systems upholding the occupation (Anteby et al., Reference Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno2016). This paper’s starting point is the phenomenon (see Jaakkola, Reference Jaakkola2020) of individuals practicing their occupation as a volunteer (Meijs et al., Reference Meijs, Ten Hoorn and Brudney2006).

Employment’s interconnections to other life domains over time, including education, volunteering, and other work, are not new theoretical (e.g., Abbott, Reference Abbott, Smelser and Swedberg2005; Giles Jr. & Eyler, Reference Giles and Eyler1994; Taylor, Reference Taylor2004) or empirical topics; for instance, careers after retirement (Cook, Reference Cook2015) or using international corporate volunteering for executive development (Pless et al., Reference Pless, Maak and Stahl2011). However, it is a fragmented topic, with inconsistent definitions, characterizations, and application of work and volunteering concepts. As a result, research inadequately captures the phenomenon in all its guises, leaving gaps between theory and praxis, especially in “less obvious” occupations and “less productive” work-life stages, and between volunteering and other disciplinary approaches (see also Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010). This paper addresses these limitations by describing occupation-related volunteering (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Breitsohl and Meijs2024) as the intersection of volunteerability and employability.

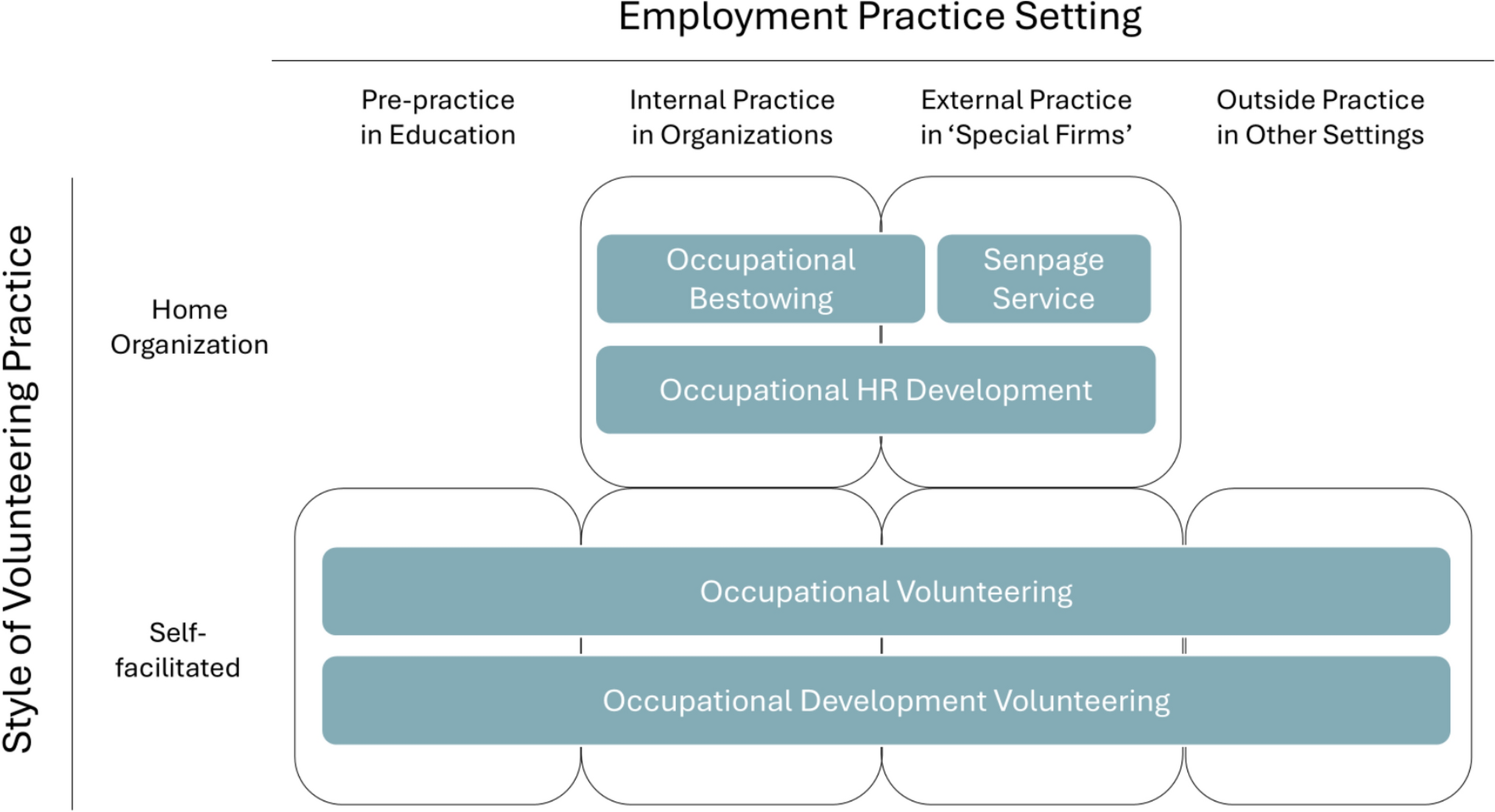

A conceptual typology “explains the fuzzy nature of many subjects by logically and causally combining different constructs into a coherent and explanatory set of types” (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2017, p. 3). This paper starts by summarizing and critiquing current research approaches, then reorganizing and combining them to create the conceptual typology of occupation-related volunteering presented in the third section. The typology combats the fuzziness, fills the gaps, and bridges praxis, theory, and current approaches; it covers all work-life stages and forms of volunteering, including with and without employer involvement. It creates five explanatory types of occupation-related volunteering: self-facilitated Occupational Volunteering and Occupational Development Volunteering and the employer-facilitated Occupational Bestowing, Senpage Service, and Occupational HR Development.

As an individual’s occupation is the intersection of volunteerability and employability, it seems appropriate that occupation-related volunteering research uses approaches developed to research occupations: through lenses of “becoming,” “doing,” and “relating” (Anteby et al., Reference Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno2016, p. 184). Becoming is how individuals socialize into their occupational community’s cultural values, norms, worldviews, and habitus. Doing is the ways individuals perform employment and volunteering tasks or practices and enact claims about their expertise. Relating is how individuals build collaborative relations with others, including intra-, inter-, extra-employment, and volunteering practices. In this paper’s last section, the three lenses and the typology’s two dimensions––an occupation practiced before, during, between, and after employment and a style of volunteering practice––form the basis of research opportunities and extensive questions.

Main Research Approaches and Definitions in the Literature

This paper conceptualizes situations where a volunteer’s occupation––their competencies and resources for employability––are prerequisites for their volunteerability. Volunteering research has three “dominant paradigms” (Rochester, Reference Rochester2013). First, the nonprofit paradigm considers volunteering as altruistic unpaid work, usually in a bureaucratic, social welfare-orientated organization, performing specific tasks and supervised by paid staff. Second, the civil society paradigm describes volunteering for participation, advocacy, or self-help in formal or informal settings with volunteer leadership and management. Finally, volunteering as recreation––“serious leisure”––with intrinsic appeal, undertaken individually or in clubs and societies, and ranging from one-off action to an “amateur career” (Stebbins, Reference Stebbins1996). Going a step further, Hustinx et al. (Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010) note that theorizing volunteering needs to consider how other fields or disciplines “idiosyncratically” treat volunteering.

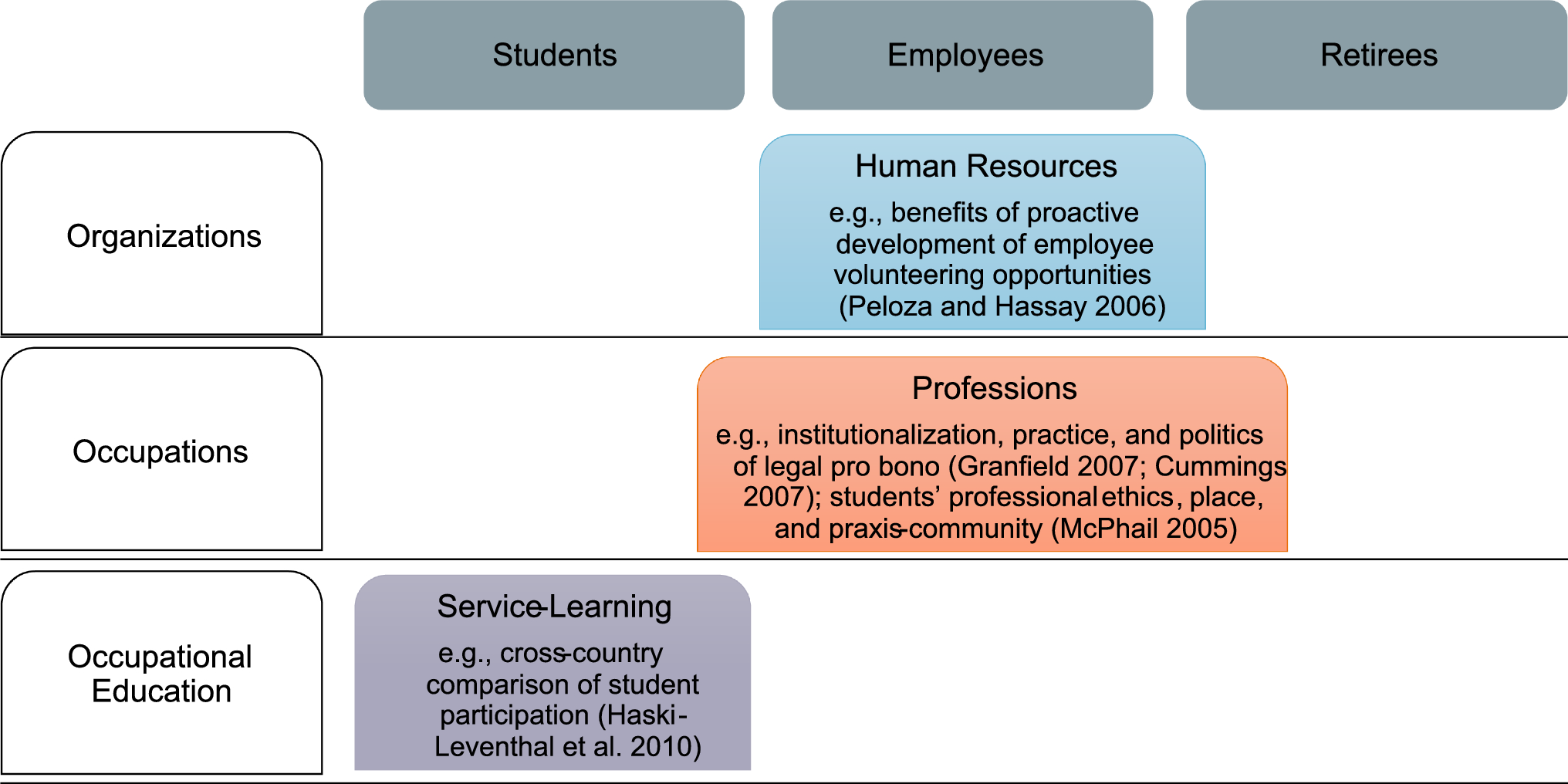

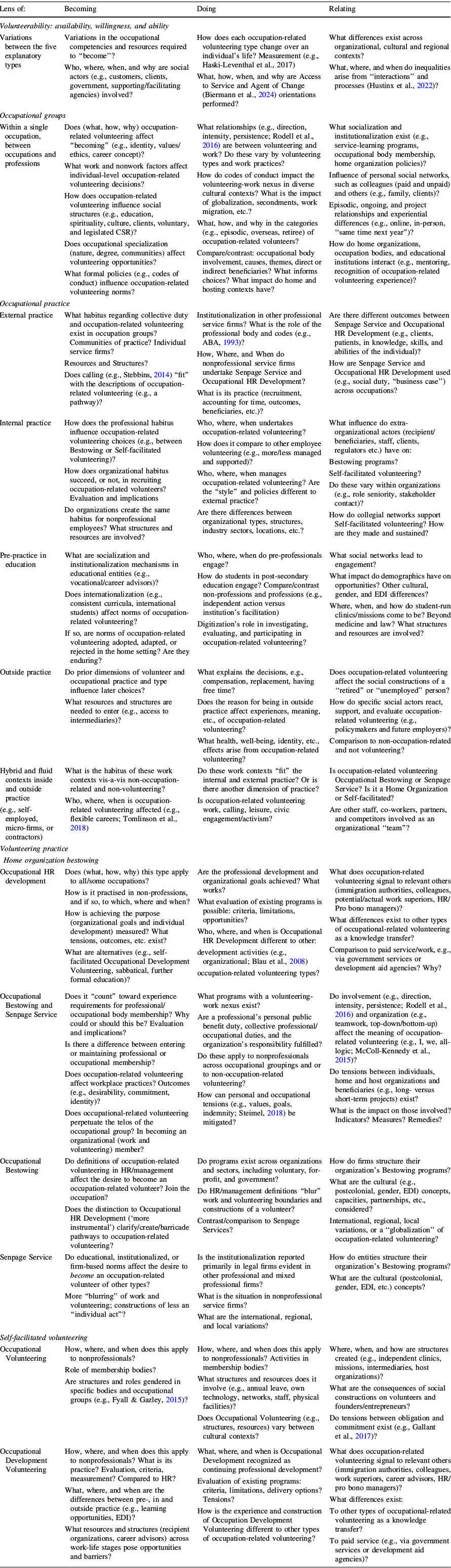

Accordingly, a trans-disciplinary narrative review (Paré et al., Reference Paré, Trudel, Jaana and Kitsiou2015) of selected practitioner resources and academic literature sourced during the systematic review (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Breitsohl and Meijs2024) gathered definitions of occupational volunteerability intersecting employability (see online supplementary file) and identified three main research approaches. The three categories do not suggest a homogeneous theoretical view exists within a field but indicate the field’s foremost empirical approach (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Main research approaches about the volunteerability–employability intersection with examples

The organization’s approach comes from business and management research, especially human resources (HR) management and development, as well as corporate social responsibility (CSR), marketing, and cross-sector collaborations. The volunteers are an organization’s employees and productive economic resources, bringing an implicit for-profit perspective despite multi-sector relevance, such as nonprofit governance, public administration, and volunteer management. The second approach is studying occupations, primarily professions and individuals in employment, less so students (e.g., McPhail, Reference McPhail2005) and retirees (e.g., Cummings, Reference Cummings2004), and more in service firms than other organizations. The third approach is occupational (primarily professional) education through service-learning: employability is the aim, and volunteerability is the tool. The approaches concentrate on three work-life stages: students learning occupations, employees, and retirees.

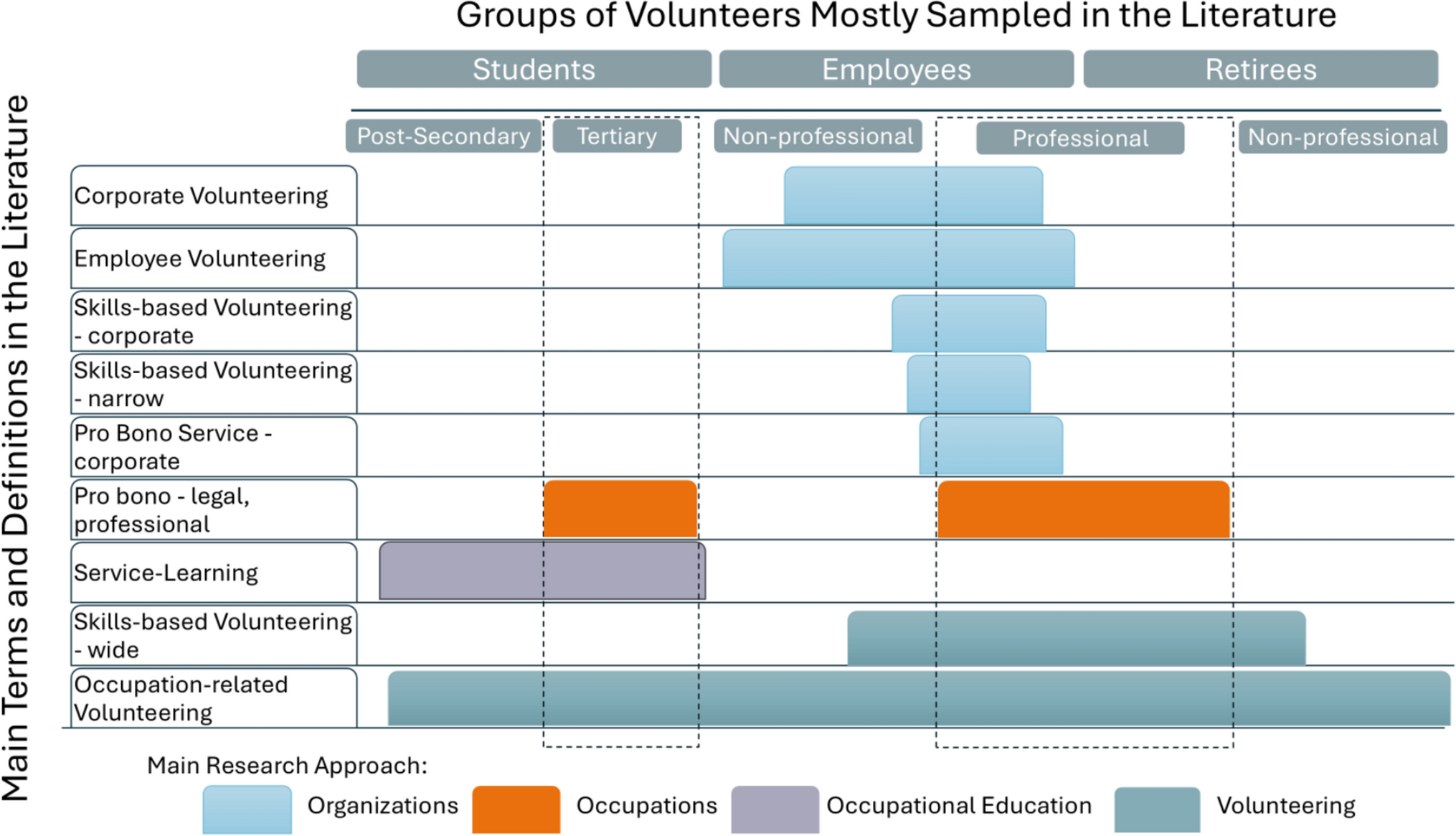

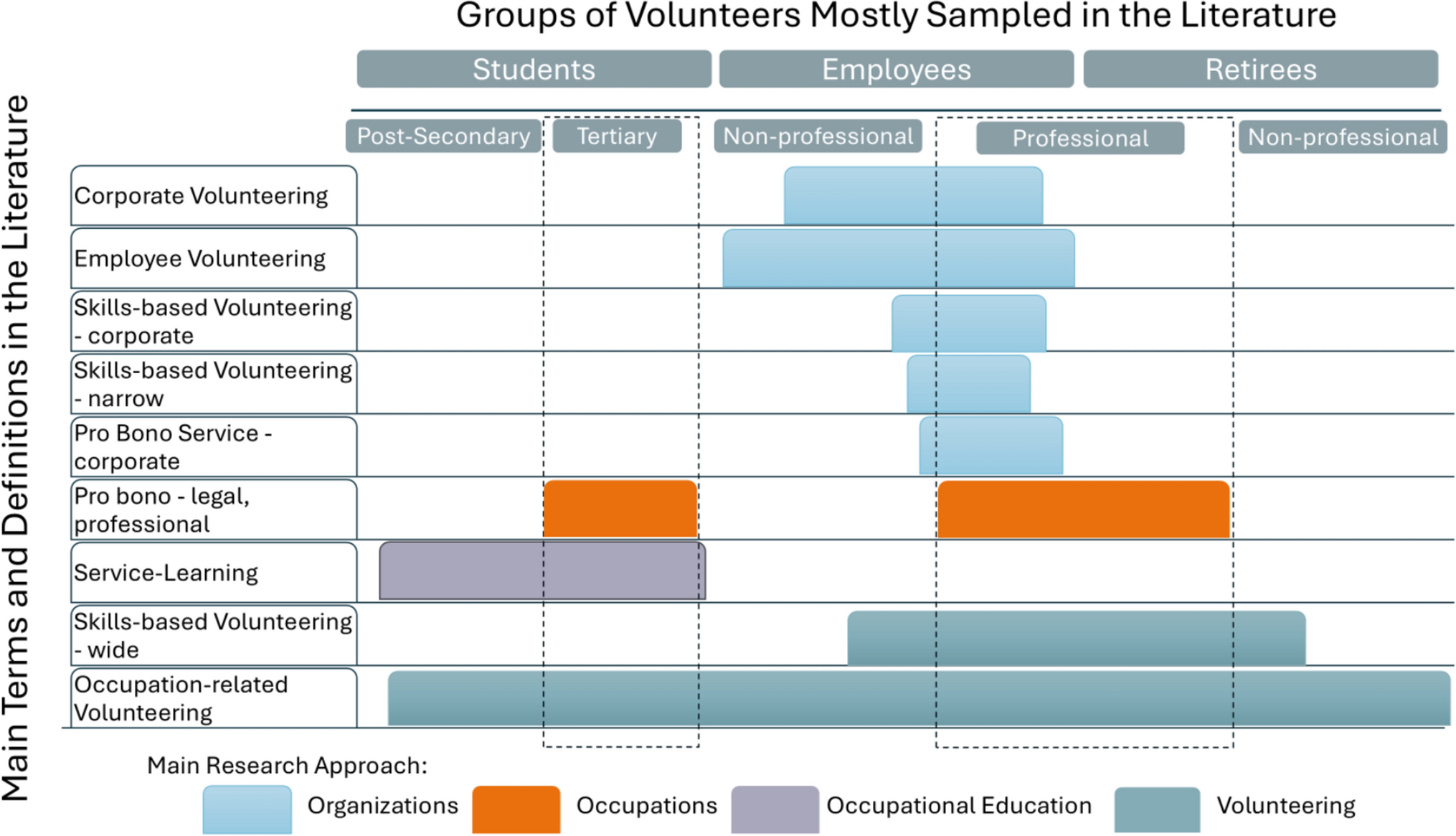

Figure 2 organizes the main definitions across the work-life stages shown in Fig. 1. It divides occupations into professional and nonprofessional occupations, a divide changing over time and place (Abbott, Reference Abbott1988; Anteby et al., Reference Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno2016), but sufficient for this paper. In this paper, terms are taken as given in the literature, including the helpful distinction that tertiary education is academic (e.g., bachelor and higher), whereas “post-secondary non-tertiary education” is “vocationally orientated” (e.g., technicians) or undertaken as pre-tertiary study (OECD 2015). The varying approaches result in differing definitions and coverage of the topic and may explain discrepant empirical findings (Rodell et al., Reference Rodell, Breitsohl, Schröder and Keating2016).

Fig. 2 Definitional coverage across research approaches, professions and non-professions, and work-life stages

The organizations approach leans toward employability, where “definitions often perceive the employees merely as the ‘instrument’ through which the societal benefit is achieved” (van Schie et al., Reference van Schie, Guentert and Wehner2011, p. 11). Employee volunteering (see review by Rodell et al., Reference Rodell, Breitsohl, Schröder and Keating2016) is extra-organizational, with no home organization (employer) direction or support, inter-organizational with passive involvement, and intra-organizational, describing “volunteer efforts made by employees within company-sanctioned programs on behalf of causes/organizations selected by their employer” (Peloza & Hassay, Reference Peloza and Hassay2006, p. 360). Inter- and intra-organizational employee volunteering covers all volunteering and is indistinguishable from corporate volunteering (e.g., Roza et al., Reference Roza, Shachar, Meijs and Hustinx2017). Corporate skills-based volunteering involves job-related inter- and intra-organizational employee volunteering, similar to a narrow definition of skilled-based volunteering but with a deliberate HR orientation (Dempsey-Brench & Schantz, Reference Dempsey-Brench and Schantz2021). The US Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) summit on corporate volunteering first reflects on pro bono as “a subset of skilled volunteering” (online appendix; CNCS 2008, p. 1), later developing a skilled-based volunteering definition (CNCS, 2010). Nonprofit organizations are designated beneficiaries across corporate and skill-based definitions, ignoring volunteering for individuals, the government, for-profits, and informal groups.

The occupations approach concentrates on (professional) pre-practice and employability. Pro bono has evolved from a primarily North American history of lawyers providing informally organized, independent legal services for the public good “without charge” into a formal, institutionalized practice with codes of conduct, commercial drivers, and communities of practice (Cummings, Reference Cummings2004; Granfield, Reference Granfield2007; Kay & Granfield, Reference Kay and Granfield2022). Despite the definition of service-learning not referring to any occupation, service-learning research concentrates on legal and medical pro bono clinics (other occupations are research opportunities). The theoretical basis for service-learning is learning from experience and reflexivity balanced with citizenship, community, and democracy (see Giles Jr. & Eyler, Reference Giles and Eyler1994). Some service-learning is mandated or for academic credit, but when organized and self-initiated, service-learning is volunteering (Haski-Leventhal et al., Reference Haski-Leventhal, Grönlund, Holmes, Meijs, Cnaan, Handy, Brudney, Hustinx, Kang, Kassam, Pessi, Ranade, Smith, Yamauchi and Zrinscak2010). As with employee volunteering, when service-learning involves occupational work, it intersects with volunteerability but is not its prime focus.

Across these three main approaches, research focuses on individuals entering their occupation, developing technical competencies and embodying practices to “become an occupational member and recognize the intra- and inter-professional practice boundaries” (Anteby et al., Reference Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno2016). Less covered is occupational training/education/development undertaken parallel to “doing” the occupation, for example, in health (von Schnurbein et al., Reference von Schnurbein, Hollenstein, Arnold and Liberatore2022) and education (Liddy & Tormey, Reference Liddy and Tormey2023), and “relating” to others, such as inter-professional service-learning (see Higbea et al., Reference Higbea, Elder, VanderMolen, Cleghorn, Brew and Branch2020). Compared to other service-learning and volunteering, there are unique exchanges, collaborations, and boundary management when professionals and volunteers, occupational colleagues or not, are involved (e.g., van Bochove et al., Reference van Bochove, Tonkens, Verplanke and Roggeveen2018; von Schnurbein et al., Reference von Schnurbein, Hollenstein, Arnold and Liberatore2022).

The last and seemingly least-used approach in Fig. 2 is volunteering. In its widest definitional form, skills-based volunteering includes all occupations in and outside employment. Pro bono also refers to volunteering, but only professional services (McColl-Kennedy et al., Reference McColl-Kennedy, Patterson, Brady, Cheung and Nguyen2015). A newer term and definition, occupation-related volunteering (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Breitsohl and Meijs2024), has the broadest coverage involving the competencies and resources of any occupation, not only professional services.

Critique of Current Approaches to Volunteerability Intersecting Employability

Volunteers act unpaid, uncoerced, and to benefit others (Meijs et al., Reference Meijs, Handy, Cnaan, Brudney, Ascoli, Ranade, Hustinx, Weber, Weiss, Dekker and Halman2003 among others), making personal decisions about acting or not, for which activity, and who benefits (van Schie et al., Reference van Schie, Guentert and Wehner2011, Reference van Schie, Gautier, Pache and Güntert2018). Organizations-orientated definitions acknowledge that employees may receive their paychecks, but this is not definitionally problematic: “the company voluntarily fulfils its social responsibility in organising CV[corporate volunteering] activities… [and] the employees voluntarily show their civic engagement by participating” (van Schie et al., Reference van Schie, Guentert and Wehner2011, p. 122). By opting in, the employee allows their employer to bestow their employment service on another.

More problematic is defining volunteering with a “charitable” or “non-profit” beneficiary (e.g., in Grant, Reference Grant2012; Rodell et al., Reference Rodell, Breitsohl, Schröder and Keating2016). Wishing to exclude spontaneous help (hardly relevant to organizations) and dealing with unorganized groups and individuals limits beneficiaries to formal structures and contradicts volunteering’s praxis. It is an unnecessary condition without definitional or empirical value. First, a volunteer has (given the definition) a choice in whom they benefit. Second, despite long-standing critique, voluntary action becomes defined by idiosyncratic charity and taxation statutes (Garton, Reference Garton2005; Salamon & Anheier, Reference Salamon and Anheier1992). Third and related, it ignores expressive views of voluntary action (Rochester, Reference Rochester2013; Studer & von Schnurbein, Reference Studer and von Schnurbein2013) and perpetuates the “non-profit paradigm” of volunteers as unpaid productive resources requiring control and coordination (Rochester, Reference Rochester2013). Organizations approach definitions view beneficiaries as close, particularly as employee and employer (e.g., Dempsey-Brench & Schantz, Reference Dempsey-Brench and Schantz2021; Pless et al., Reference Pless, Maak and Stahl2011) and may head toward the gray zone of mandated volunteering (“institutionalized practices,” Kay & Granfield, Reference Kay and Granfield2022; “voluntolding,” Kelemen et al., Reference Kelemen, Mangan and Moffat2017; or “marginal volunteering,” Stebbins, Reference Stebbins1996).

Empirical research often mixes or does not distinguish between the occupations sampled (e.g., McCallum et al., Reference McCallum, Schmid and Price2013; McColl-Kennedy et al., Reference McColl-Kennedy, Patterson, Brady, Cheung and Nguyen2015), limiting understanding of the practices studied. Notwithstanding, it seems little scholarly attention goes to nonprofessionals (see findings in Anteby et al., Reference Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno2016; Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Breitsohl and Meijs2024). Non-professions may fall outside the academic fields in universities and, therefore, researchers’ realm of expertise. Possibly, professionals face more pressing issues, such as professional codes and statutory duties creating litigation risks, tensions between paid and volunteer colleagues, and concerns regarding service and ethical standards (e.g., McColl-Kennedy et al., Reference McColl-Kennedy, Patterson, Brady, Cheung and Nguyen2015; Steimel, Reference Steimel2018). However, nonprofessional occupations’ codes and statutory duties also create risks and tensions and “becoming, doing, and relating” to a nonprofessional occupation may also include an ethos of providing services without charge, such as hairdressers supporting cancer patients and other causes (Dinoto, Reference Dinoto2024; Friseure gegen Krebs, 2024; St. Paul’s Hospital, 2018).

Pro bono as lawyers offering lower or no charge services to uphold justice has evolved into businesses providing “professional services … the recipient nonprofit would otherwise have to pay [for]” (CNCS, 2008, p. 1). Nonprofit governance positions are unpaid; however, it is difficult to grasp what services a recipient (nonprofit or otherwise) would receive for no charge if volunteers did not perform them. Instead (and in contrast to employers bestowing their employees), it is the selling firm, organization, or giver’s perspective; what they would otherwise invoice for payment is, in this case, provided senpage (Esperanto; without charge).

The volunteering field faces epistemological (e.g., Dean, Reference Dean2015; Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and Shachar2022) and praxis (e.g., J. Cook & Burchell, Reference Cook and Burchell2018; Eimhjellen, Reference Eimhjellen2023) inequities, but the service-learning view of volunteering seems harsh:

[It] is a form of charity. It is about providing service, with no intentional link to reflection or learning. While volunteer activities can be ongoing, they often occur on a one-time or sporadic basis. Many service-learning advocates view volunteerism as a one-way, rather paternalistic kind of “feel good” concept that infers the perpetuation of the status quo and dependency. (Jacoby & Howard, Reference Jacoby and Howard2014 , p. 2)

Service-learning “seeks to strike a balance” between the student and the beneficiary, and service and learning (Jacoby & Howard, Reference Jacoby and Howard2014) yet is criticized for perpetuating Western ideals and neocolonial inequalities (e.g., Santiago-Ortiz, Reference Santiago-Ortiz2019; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Smith-Tolken, Naidoo and Bringle2011). The attention to professions over non-professions creates similar inequitable discourses, constructions, and hierarchies of service-learners and community needs. Although the definition of service-learning (online appendix; Jacoby, Reference Jacoby1996) does not specify any occupations, little research exists on post-secondary education for nonprofessional occupations. For example, Biermann et al.’s review (Reference Biermann, Breitsohl and Meijs2024) only identified university service-learning and this narrative review only two on technical students’ service-learning (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Said and Nor2019; Zulch et al., Reference Zulch, Saunders, Peters and Quinlivan2016).

A closer analysis of service-learning and post-qualification continuing occupational development (COD) reveals an anomaly significant to occupation-related volunteering. Post-qualification occupation-related service-learning offers improved occupational competencies, including technical skills, leadership, ethical decision-making, and confidence (e.g., Liddy & Tormey, Reference Liddy and Tormey2023; Pless et al., Reference Pless, Maak and Stahl2011). In contrast, COD does not develop competencies but is “better characterised as a support for improvements in professional practice” (Friedman & Phillips, Reference Friedman and Phillips2004, p. 374). These fronts are reconcilable as improved practice does serve client/patient/community needs. It also uncovers an occupation-related volunteering practice missed by service-learning and COD research. On one side is voluntary pre- and post-qualification service-learning (sometimes with COD points). On the other side is re/certification and compulsory COD mandated by the legislator (directly or delegated to occupational/professional bodies, such as medical or master builders’ associations). Compliance is part of maintaining occupational “belonging” and employability, consistent with the definitions of the organizations and occupations approaches.

The wide skills-based volunteering term is subjective and imprecise, defined as “build and sustain” and “achieve … successfully” (online appendix; CNCS, 2010). What happens if volunteers are unsuccessful and do not build and sustain the nonprofit? Who makes the evaluations? Further issues with the skills-based volunteering definitions (appendix) are its reference to formal nonprofit organizations and employees (no other work-life stages) but omitting occupational links. Other individuals have the skills to perform occupational tasks, such as a certified emergency responder performing nursing tasks. The conceptual (and real-life) difference is that they, their colleagues, clients/patients, and others understand it is not the volunteer’s “professional” occupational work but their leisure-time “amateur” career (Stebbins, Reference Stebbins1996, Reference Stebbins2014).

Reorganizing Concepts to Develop the Typology

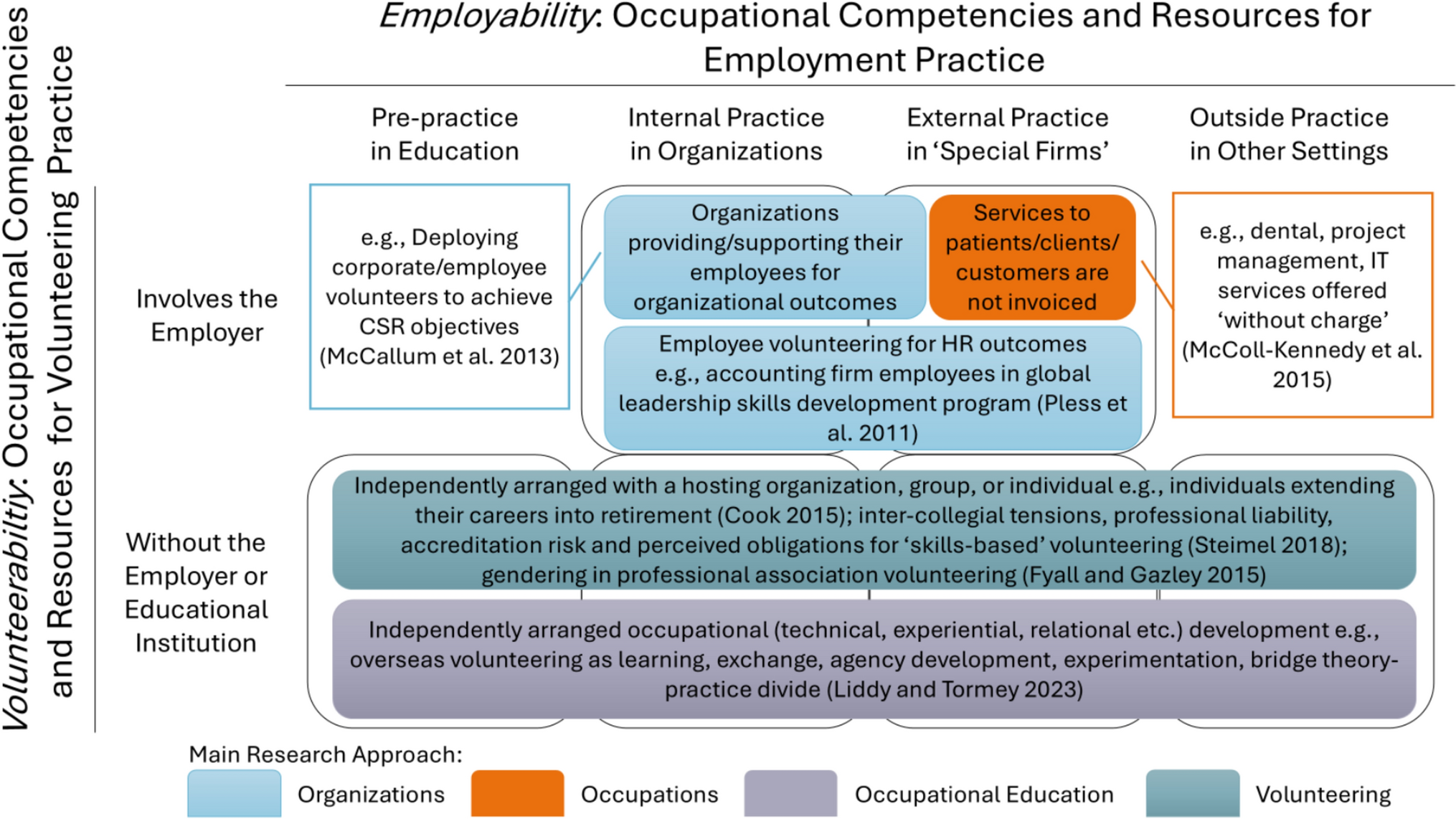

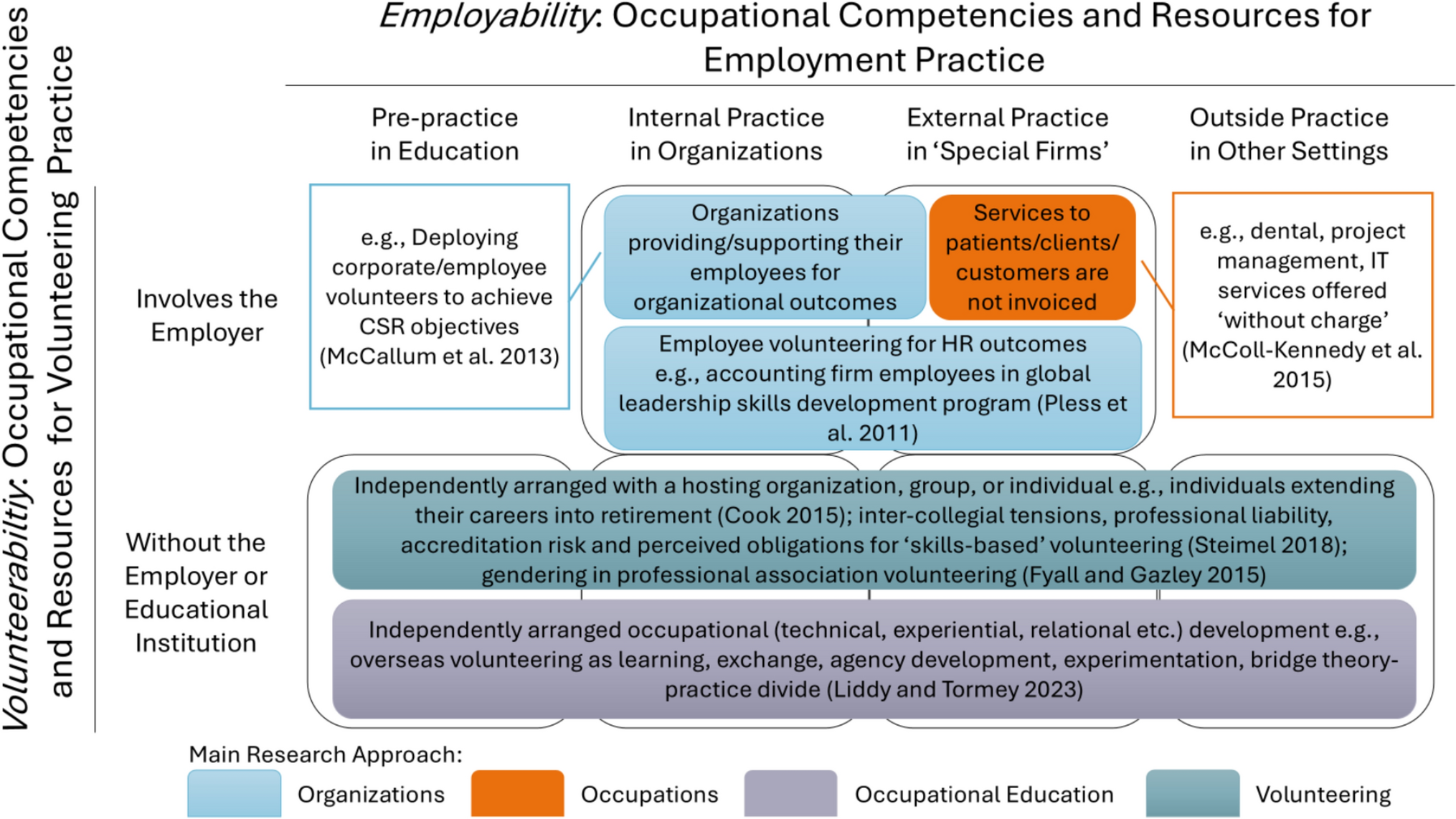

Conceptually, the two dimensions of volunteerability intersecting employability blend the terms, definitions, and main research approaches presented in Fig. 2. Examples from the literature in this paper (see Fig. 3) help “flesh out a set of novel constructs” (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2017, p. 7) that then create the conceptual typology of occupation-related volunteering, the last definition in Fig. 2.

Fig. 3 Reorganizing terms, definitions, and research approaches with examples

The occupation-related volunteering definition supports the three-element construction of a volunteer––individuals acting unpaid, uncoerced, and benefitting others––adding a fourth: occupational competencies and economic, social, and cultural capital (appendix; Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Breitsohl and Meijs2024). The definition captures all work-life stages and occupations and, as with service-learning, self-benefit coexists alongside benefitting others with COD as a type of occupation-related volunteering. It is broader than the organizations approach and, as with pro bono, allows self-facilitated action for beneficiaries they choose, be it individuals, informal, or formal structures. Whether inter-professional exchanges (e.g., Liddy & Tormey, Reference Liddy and Tormey2023) or performing services only their qualifications/certifications allow (e.g., Steimel, Reference Steimel2018), the competencies and resources of their occupation are necessary for their volunteering. Therefore, occupation-related volunteering is the best fit because its definition covers all intersections along the volunteerability and employability dimensions in Fig. 3.

A Typology of Occupation-Related Volunteering

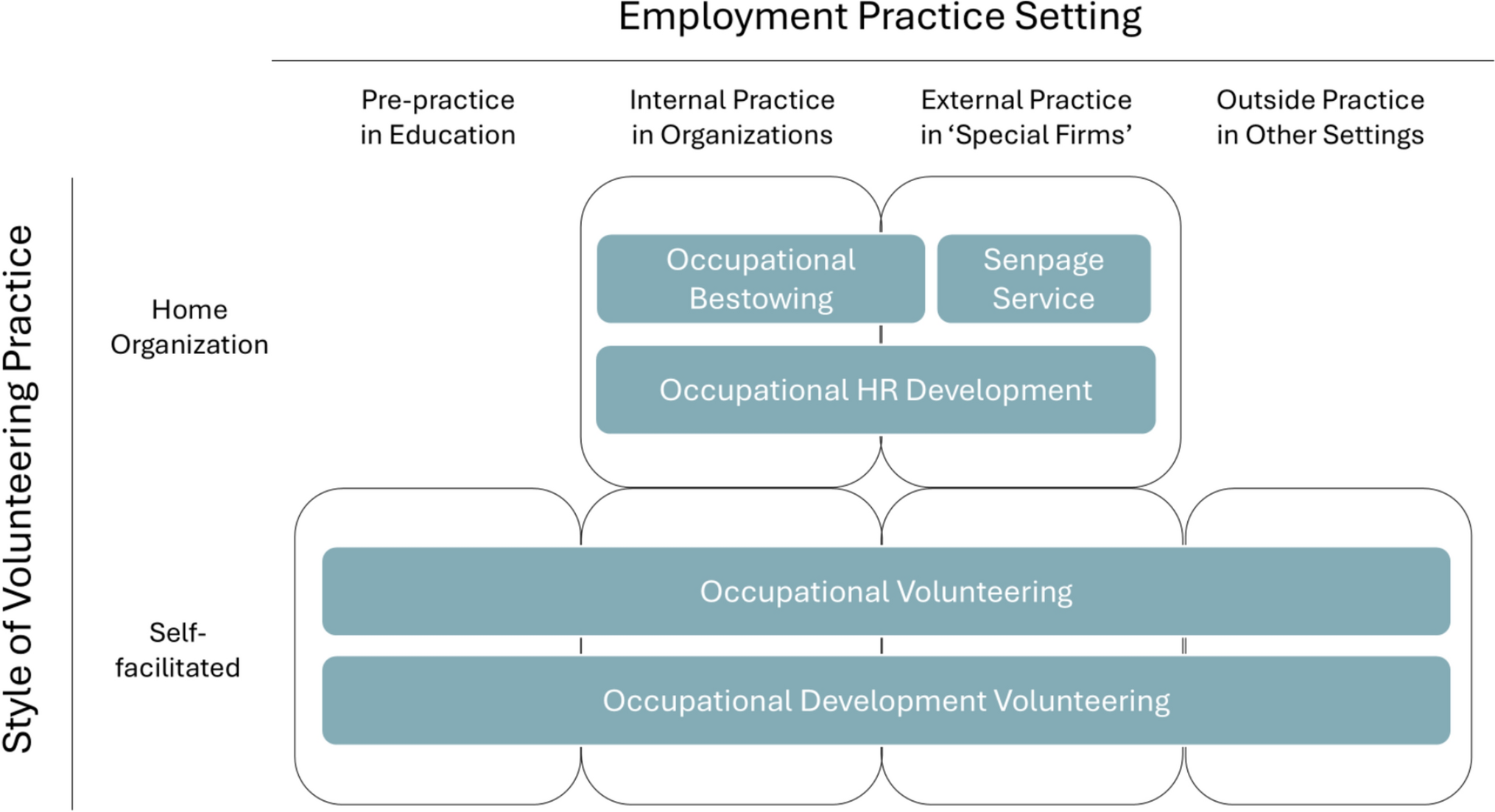

The definition of occupation-related volunteering uses continuums, not absolutes; similarly, the typology’s dimensions and types use constructs and causal interactions with “general yet variable” boundaries (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2017, p. 7). The typology of occupation-related volunteering (Fig. 4) illustrates the “co-evolution, conflict and interference of two or more practices” (Nicolini, Reference Nicolini, Jonas, Littig and Wroblewski2017, p. 30): the “becoming, doing, and relating” to an occupation for employment and volunteering. The two dimensions remove the fuzziness with new “explanatory types” (see Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2017; Jaakkola, Reference Jaakkola2020) of occupation-related volunteering.

Fig. 4 Typology of occupation-related volunteering

The typology adopts a different lexicon. It uses senpage (Esperanto; without charge, at no cost) to avoid professional connotations––it is unlikely hairdressers describe themselves as pro bono service providers––and conflicting legal, professional, and corporate pro bono definitions. As explained earlier, it uses bestowing because the organization “donates” their employees’ service, and, definitionally, volunteers are individuals. Therefore, individuals volunteer, but their employer bestows their services, making it different from other volunteering opportunities. Finally, it introduces five new occupation-related volunteering types to reorganize current knowledge.

The vertical axis shows occupation-related volunteering ranging from within-home organizations to self-facilitated leisure time, reflecting the continuum of extra-, intra-, and inter-organizational employee volunteering (Peloza & Hassay, Reference Peloza and Hassay2006). Home organization bestowing refers to an individual’s employment organization of any structure (e.g., corporation, service firm, self-employed, charity) or sector (for-profit, third, or government). Self-facilitated volunteering closely resembles the social constructions of a volunteer, for assumedly, “most volunteers are not purely altruistic,” choosing activities of personal interest in their leisure time (Meijs et al., Reference Meijs, Handy, Cnaan, Brudney, Ascoli, Ranade, Hustinx, Weber, Weiss, Dekker and Halman2003).

The horizontal axis has work-life stages found in occupation-related volunteering studies: pre-practice (students transitioning into the occupation), outside practice (not in education or employment, including retirees), and, in-between, in practice (employees). Employment is split into internal or external practice to overcome public/private practice terminology, which varies by occupation and internationally (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Breitsohl and Meijs2024).

Pre-practice is the transitional phase of becoming an occupational member, where individuals have sufficient knowledge, skills, abilities, and resources for limited and usually supervised practice of their (future) occupation, such as student clinics. Outside Practice refers to individuals who consider themselves occupational members but are not in employment or education, for example, retired, in other occupations, or between roles for health, relocation, or other reasons. Developing, using, or maintaining occupational competencies and resources (employability) requires different volunteerability practices with different coordination, facilitation, and systems. These are processes of “doing and relating” to their occupation and the practice of occupation-related volunteering.

Internal Practice is in structures where practitioners perform services to advance their organization’s (private) interests. In contrast, external practice covers service firms offering services to and advancing the interests of their (public) patients/clients. Pro bono literature makes the legal field an exemplar for external practice, constructing a profession and a professional with institutionalized duties of care to clients (e.g., Granfield, Reference Granfield2007). However, external practice includes nonprofessionals, a neglected sample with significant research opportunities. Conceptually, some but not necessarily all occupations perform occupation-related volunteering, perhaps hairdressers but not plumbers, through the distinctive socialization processes when “becoming, doing, and relating” to their occupation with similar opportunities, risks, and tensions as well-studied professional occupations.

Additionally, the institutionalization of occupation-related volunteering practices is distinctive to some service firms, for example, employer-remunerated pro bono patterns in legal firms (Kay & Granfield, Reference Kay and Granfield2022, p. 83), supporting the conceptual segregation of external practice. However, unlike the professional service firm literature (e.g., as Westernized, global “professional partnerships,” Boussebaa, Reference Boussebaa2024; as professionalism, Noordegraaf, Reference Noordegraaf2015; as knowledge-intensive firms, Von Nordenflycht, Reference Von Nordenflycht2010), occupation-related volunteering includes all occupations, meaning its practice exists in “special” but not all external practice firms.

Occupational Volunteering crosses all occupational practice settings. The practitioner’s availability, willingness, and ability––their occupational competencies and resources––decide volunteerability’s practice. Occupational Volunteering includes elected board positions (e.g., treasurer) and operational roles (e.g., IT administration), self-organized initiatives (e.g., international medical trips), and membership body activities (e.g., discussion group organizer). The three main approaches (see Fig. 2) inadequately construct this type of occupation-related volunteering despite it being closest to the social constructions of a volunteer and, possibly, what most occupation-related volunteers perform.

Occupational Development Volunteering is in all practice settings and according to the practitioner’s occupational development needs as they decide. Service-learning and COD are ways of “becoming, doing, and relating” to the occupational group. Intersecting volunteerability with occupational development practices is quite unlike the approaches of organizations and occupations/professions, and it opens a novel volunteering-specific research direction.

Occupational Bestowing and Senpage Service are wholly or partially determined by the organization’s policies and practices to fulfill its responsibilities and mission. Individuals in internal or external practice perform Occupational Bestowing, for example, in a firm’s corporate volunteering project. In contrast, Senpage Service is only in external practice. Examples used in this paper include firms offering indigent clients pro bono advice or hairdressers providing patients with haircuts “without charge.” As noted earlier, the term avoids unintended connotations and definitional conflicts; it expresses that some firms perform services for a patient/client just like any other; the difference is that no invoice is payable. Senpage Service is part of the organization and practice of work within the firm: it is a socialized and institutionalized practice where the firm has a “special” relationship with clients/patients embedded in social, statutory, and occupational duties of care and conduct. Finally, Occupational HR Development is by individuals in their paid occupational work in either internal or external practice. The organization’s policies, practices, and human resource requirements, alongside the individual’s training and development needs, determine its practice.

Occupation-Related Volunteering Research Opportunities

This paper has reorganized the theoretical features of occupation-related volunteering using the dimensions of volunteerability and employability. The conceptual typology is a foundation for exploring an individual’s availability, willingness, and ability to be an occupation-related volunteer and, crucially, how they vary across the five explanatory types of occupation-related volunteering, for example, across the volunteerability measurement scale (Haski‐Leventhal et al., Reference Haski‐Leventhal, Meijs, Lockstone‐Binney, Holmes and Oppenheimer2017).

The typology ignores formal/informal organization, hierarchies of professional/nonprofessional and having greater or lesser resources. It acknowledges all occupations, work-life stages and employment settings. This section’s discussion and research questions encourage critical research to counter knowledge primarily generated by and for Western scholars (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Breitsohl and Meijs2024, p. 6) and broadly in line with the “non-profit paradigm” of voluntary action (Rochester, Reference Rochester2013). With occupation-related volunteering occurring outside worktime, the leisure “paradigm” offers an alternative to the research approaches discussed in this paper (see Fig. 1), as does volunteering for advocacy and participation.

A Dynamic View of Occupation-Related Volunteerability

When employability and volunteerability are in the same sentence, the association may well be volunteering for employability as an instrument to improve (although contested; e.g., Kamerāde & Paine, Reference Kamerāde and Paine2014) employment and career opportunities (e.g., McCallum et al., Reference McCallum, Schmid and Price2013; Pless et al., Reference Pless, Maak and Stahl2011). The definition of occupation-related volunteering involves competencies and resources, but unlike resource theories of volunteering (where employment and resources affect volunteering choices; e.g., van Schie et al., Reference van Schie, Gautier, Pache and Güntert2018; Wilson & Musick, Reference Wilson and Musick1997), it does not contend that resource excess/deficiency generates greater/lesser availability, willingness, and ability to volunteer. Competencies and resources could be a unit of analysis, for example, capital volume and volunteering positions (Eimhjellen, Reference Eimhjellen2023), but this is not their only function.

For the definition and typology, having occupational competencies and resources is the conceptual boundary around occupation-related volunteerability: being available, willing, and able (as with any volunteering) but with the crucial difference of having the occupational competencies and resources to do so. Resources may start in the educational and occupational domains (with inherently inequitable distributions); however, individuals develop, use, and maintain them through occupation-related volunteering. Therefore, there is a two-way, dynamic exchange of resources from an occupation practiced in different social worlds by practitioners within a distinct occupational group. In this sense, “becoming, doing, and relating” to one’s occupation applies to occupational employability and occupation-related volunteerability.

Societal, Occupational, and Employability Changes

Workplace transformations have a more direct impact on occupation-related volunteerability than other volunteering. Constructions of work, employment, and occupations continually evolve, illustrated by the demise of traditional Western life-course trajectories of study → employment → homecare for women → retirement and the emergence of kaleidoscope, protean, and boundaryless careers (see the overview by Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Baird, Berg and Cooper2018). As liberating as these developments seem (e.g., women in occupations allows women in occupation-related volunteering), they occur with structural upheavals: redundancies, job crafting, international employment migration, platform and gig work, and leisure and poverty-driven second and post-retirement careers (e.g., London, Reference London1996; Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Richardson and Zorn2012). Such developments have resource theory effects for all volunteers but immediate, direct, and distinctive consequences for occupation-related volunteering praxis, practices, and practitioners. The typology captures the causal interactions of practices in one domain affecting others that are, to date, under the radar of volunteering research. For example, Anteby et al. (Reference Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno2016) ponder new work-life trajectories, where occupational affiliation fills the void as organizational affinity subsides. Such void-filling opens research questions about changes in the relative appeal of professional/occupational body Occupational Volunteering compared to home organization Occupational Bestowing.

Awareness of the legacy of societal change supports researching “inequalities and occupations” (Anteby et al., Reference Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno2016) reflected in practitioner hierarchies and segregation (e.g., profession over occupation, professional/paid over amateur/volunteer, manager over managed) and the mechanisms and processes of practices in one setting interacting with practices in another (Antonacopoulou & Pesqueux, Reference Antonacopoulou and Pesqueux2010). Research can advance understanding of employment practices molding (inequitable) discourses and (mis)conceptions about––and real-life opportunities for––occupation-related volunteering praxis, practices, and practitioners (e.g., kinship, Cutcher & Dale, Reference Cutcher and Dale2023; gender, Fyall & Gazley, Reference Fyall and Gazley2015).

Specific Research Questions Investigating the Intersection

The typology of occupation-related volunteering’s dimensions of volunteering and employment practice and their explanatory types lead to questions about the dynamics and variations between and across those practices (Antonacopoulou & Pesqueux, Reference Antonacopoulou and Pesqueux2010; Nicolini, Reference Nicolini, Jonas, Littig and Wroblewski2017).

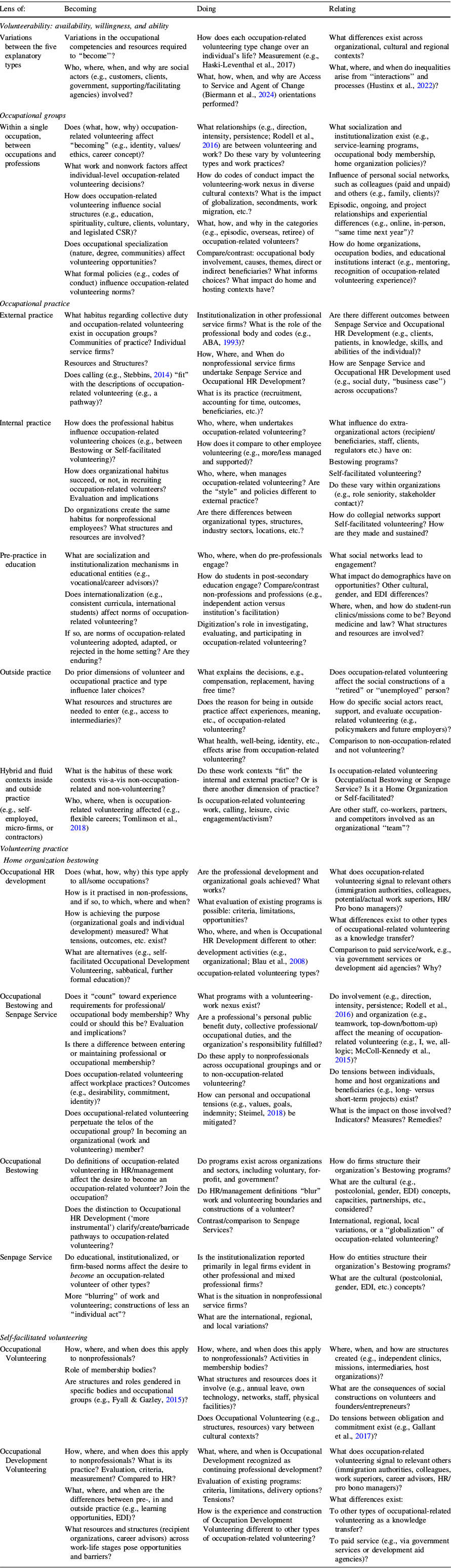

Table 1 provides an extensive list of research opportunities for volunteering-specific research into occupation-related volunteering. Using the typology and research lenses of “becoming, doing, and relating” (Anteby et al., Reference Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno2016), Table 1 has questions about occupation-related volunteering praxis, practices, and practitioners. The questions can rectify the limitations of current approaches highlighted throughout this paper: investigating all occupations (not only “traditional” professions), formal and informal organizational structures, and all work-life stages, including pre-practice and continuing occupational education/development.

Table 1 Future research questions based on lenses of becoming, doing, and relating to an occupation (based on Anteby et al., Reference Anteby, Chan and DiBenigno2016) (EDI = equity, diversity, and inclusion)

|

Lens of: |

Becoming |

Doing |

Relating |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Volunteerability: availability, willingness, and ability |

|||

|

Variations between the five explanatory types |

Variations in the occupational competencies and resources required to “become”? Who, where, when, and why are social actors (e.g., customers, clients, government, supporting/facilitating agencies) involved? |

How does each occupation-related volunteering type change over an individual’s life? Measurement (e.g., Haski‐Leventhal et al., 2017) What, how, when, and why are Access to Service and Agent of Change (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Breitsohl and Meijs2024) orientations performed? |

What differences exist across organizational, cultural and regional contexts? What, where, and when do inequalities arise from “interactions” and processes (Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Grubb, Rameder and Shachar2022)? |

|

Occupational groups |

|||

|

Within a single occupation, between occupations and professions |

Does (what, how, why) occupation-related volunteering affect “becoming” (e.g., identity, values/ethics, career concept)? What work and nonwork factors affect individual-level occupation-related volunteering decisions? How does occupation-related volunteering influence social structures (e.g., education, spirituality, culture, clients, voluntary, and legislated CSR)? Does occupational specialization (nature, degree, communities) affect volunteering opportunities? What formal policies (e.g., codes of conduct) influence occupation-related volunteering norms? |

What relationships (e.g., direction, intensity, persistence; Rodell et al., Reference Rodell, Breitsohl, Schröder and Keating2016) are between volunteering and work? Do these vary by volunteering types and work practices? How do codes of conduct impact the volunteering-work nexus in diverse cultural contexts? What is the impact of globalization, secondments, work migration, etc.? What, how, and why in the categories (e.g., episodic, overseas, retiree) of occupation-related volunteers? Compare/contrast: occupational body involvement, causes, themes, direct or indirect beneficiaries? What informs choices? What impact do home and hosting contexts have? |

What socialization and institutionalization exist (e.g., service-learning programs, occupational body membership, home organization policies)? Influence of personal social networks, such as colleagues (paid and unpaid) and others (e.g., family, clients)? Episodic, ongoing, and project relationships and experiential differences (e.g., online, in-person, “same time next year”)? How do home organizations, occupation bodies, and educational institutions interact (e.g., mentoring, recognition of occupation-related volunteering experience)? |

|

Occupational practice |

|||

|

External practice |

What habitus regarding collective duty and occupation-related volunteering exist in occupation groups? Communities of practice? Individual service firms? Resources and Structures? Does calling (e.g., Stebbins, Reference Stebbins2014) “fit” with the descriptions of occupation-related volunteering (e.g., a pathway)? |

Institutionalization in other professional service firms? What is the role of the professional body and codes (e.g., ABA, 1993)? How, Where, and When do nonprofessional service firms undertake Senpage Service and Occupational HR Development? What is its practice (recruitment, accounting for time, outcomes, beneficiaries, etc.)? |

Are there different outcomes between Senpage Service and Occupational HR Development (e.g., clients, patients, in knowledge, skills, and abilities of the individual)? How are Senpage Service and Occupational HR Development used (e.g., social duty, “business case”) across occupations? |

|

Internal practice |

How does the professional habitus influence occupation-related volunteering choices (e.g., between Bestowing or Self-facilitated volunteering)? How does organizational habitus succeed, or not, in recruiting occupation-related volunteers? Evaluation and implications Do organizations create the same habitus for nonprofessional employees? What structures and resources are involved? |

Who, where, when undertakes occupation-related volunteering? How does it compare to other employee volunteering (e.g., more/less managed and supported)? Who, where, when manages occupation-related volunteering? Are the “style” and policies different to external practice? Are there differences between organizational types, structures, industry sectors, locations, etc.? |

What influence do extra-organizational actors (recipient/beneficiaries, staff, clients, regulators etc.) have on: Bestowing programs? Self-facilitated volunteering? Do these vary within organizations (e.g., role seniority, stakeholder contact)? How do collegial networks support Self-facilitated volunteering? How are they made and sustained? |

|

Pre-practice in education |

What are socialization and institutionalization mechanisms in educational entities (e.g., vocational/career advisors)? Does internationalization (e.g., consistent curricula, international students) affect norms of occupation-related volunteering? If so, are norms of occupation-related volunteering adopted, adapted, or rejected in the home setting? Are they enduring? |

Who, where, when do pre-professionals engage? How do students in post-secondary education engage? Compare/contrast non-professions and professions (e.g., independent action versus institution’s facilitation) Digitization’s role in investigating, evaluating, and participating in occupation-related volunteering? |

What social networks lead to engagement? What impact do demographics have on opportunities? Other cultural, gender, and EDI differences? Where, when, and how do student-run clinics/missions come to be? Beyond medicine and law? What structures and resources are involved? |

|

Outside practice |

Do prior dimensions of volunteer and occupational practice and type influence later choices? What resources and structures are needed to enter (e.g., access to intermediaries)? |

What explains the decisions, e.g., compensation, replacement, having free time? Does the reason for being in outside practice affect experiences, meaning, etc., of occupation-related volunteering? What health, well-being, identity, etc., effects arise from occupation-related volunteering? |

Does occupation-related volunteering affect the social constructions of a “retired” or “unemployed” person? How do specific social actors react, support, and evaluate occupation-related volunteering (e.g., policymakers and future employers)? Comparison to non-occupation-related and not volunteering? |

|

Hybrid and fluid contexts inside and outside practice (e.g., self-employed, micro-firms, or contractors) |

What is the habitus of these work contexts vis-a-vis non-occupation-related and non-volunteering? Who, where, when is occupation-related volunteering affected (e.g., flexible careers; Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Baird, Berg and Cooper2018) |

Do these work contexts “fit” the internal and external practice? Or is there another dimension of practice? Is occupation-related volunteering work, calling, leisure, civic engagement/activism? |

Is occupation-related volunteering Occupational Bestowing or Senpage Service? Is it a Home Organization or Self-facilitated? Are other staff, co-workers, partners, and competitors involved as an organizational “team”? |

|

Volunteering practice |

|||

|

Home organization bestowing |

|||

|

Occupational HR development |

Does (what, how, why) this type apply to all/some occupations? How is it practised in non-professions, and if so, to which, where and when? How is achieving the purpose (organizational goals and individual development) measured? What tensions, outcomes, etc. exist? What are alternatives (e.g., self-facilitated Occupational Development Volunteering, sabbatical, further formal education)? |

Are the professional development and organizational goals achieved? What works? What evaluation of existing programs is possible: criteria, limitations, opportunities? Who, where, and when is Occupational HR Development different to other: development activities (e.g., organizational; Blau et al., Reference Blau, Andersson, Davis, Daymont, Hochner, Koziara, Portwood and Holladay2008) occupation-related volunteering types? |

What does occupation-related volunteering signal to relevant others (immigration authorities, colleagues, potential/actual work superiors, HR/Pro bono managers)? What differences exist to other types of occupational-related volunteering as a knowledge transfer? Comparison to paid service/work, e.g., via government services or development aid agencies? Why? |

|

Occupational Bestowing and Senpage Service |

Does it “count” toward experience requirements for professional/occupational body membership? Why could or should this be? Evaluation and implications? Is there a difference between entering or maintaining professional or occupational membership? Does occupation-related volunteering affect workplace practices? Outcomes (e.g., desirability, commitment, identity)? Does occupational-related volunteering perpetuate the telos of the occupational group? In becoming an organizational (work and volunteering) member? |

What programs with a volunteering-work nexus exist? Are a professional’s personal public benefit duty, collective professional/occupational duties, and the organization’s responsibility fulfilled? Do these apply to nonprofessionals across occupational groupings and or to non-occupation-related volunteering? How can personal and occupational tensions (e.g., values, goals, indemnity; Steimel, Reference Steimel2018) be mitigated? |

Do involvement (e.g., direction, intensity, persistence; Rodell et al., Reference Rodell, Breitsohl, Schröder and Keating2016) and organization (e.g., teamwork, top-down/bottom-up) affect the meaning of occupation-related volunteering (e.g., I, we, all-logic; McColl-Kennedy et al., Reference McColl-Kennedy, Patterson, Brady, Cheung and Nguyen2015)? Do tensions between individuals, home and host organizations and beneficiaries (e.g., long- versus short-term projects) exist? What is the impact on those involved? Indicators? Measures? Remedies? |

|

Occupational Bestowing |

Do definitions of occupation-related volunteering in HR/management affect the desire to become an occupation-related volunteer? Join the occupation? Does the distinction to Occupational HR Development (‘more instrumental’) clarify/create/barricade pathways to occupation-related volunteering? |

Do programs exist across organizations and sectors, including voluntary, for-profit, and government? Do HR/management definitions “blur” work and volunteering boundaries and constructions of a volunteer? Contrast/comparison to Senpage Services? |

How do firms structure their organization’s Bestowing programs? What are the cultural (e.g., postcolonial, gender, EDI) concepts, capacities, partnerships, etc., considered? International, regional, local variations, or a “globalization” of occupation-related volunteering? |

|

Senpage Service |

Do educational, institutionalized, or firm-based norms affect the desire to become an occupation-related volunteer of other types? More “blurring” of work and volunteering; constructions of less an “individual act”? |

Is the institutionalization reported primarily in legal firms evident in other professional and mixed professional firms? What is the situation in nonprofessional service firms? What are the international, regional, and local variations? |

How do entities structure their organization’s Bestowing programs? What are the cultural (postcolonial, gender, EDI, etc.) concepts? |

|

Self-facilitated volunteering |

|||

|

Occupational Volunteering |

How, where, and when does this apply to nonprofessionals? Role of membership bodies? Are structures and roles gendered in specific bodies and occupational groups (e.g., Fyall & Gazley, Reference Fyall and Gazley2015)? |

How, where, and when does this apply to nonprofessionals? Activities in membership bodies? What structures and resources does it involve (e.g., annual leave, own technology, networks, staff, physical facilities)? Does Occupational Volunteering (e.g., structures, resources) vary between cultural contexts? |

Where, when, and how are structures created (e.g., independent clinics, missions, intermediaries, host organizations)? What are the consequences of social constructions on volunteers and founders/entrepreneurs? Do tensions between obligation and commitment exist (e.g., Gallant et al., Reference Gallant, Smale and Arai2017)? |

|

Occupational Development Volunteering |

How, where, and when does this apply to nonprofessionals? What is its practice? Evaluation, criteria, measurement? Compared to HR? What, where, and when are the differences between pre-, in and outside practice (e.g., learning opportunities, EDI)? What resources and structures (recipient organizations, career advisors) across work-life stages pose opportunities and barriers? |

What, where, and when is Occupational Development recognized as continuing professional development? Evaluation of existing programs: criteria, limitations, delivery options? Tensions? How is the experience and construction of Occupation Development Volunteering different to other types of occupation-related volunteering? |

What does occupation-related volunteering signal to relevant others (immigration authorities, colleagues, work superiors, career advisors, HR/pro bono managers)? What differences exist: To other types of occupational-related volunteering as a knowledge transfer? To paid service (e.g., via government services or development aid agencies)? |

Conclusion

Volunteerability and employability intersect when an occupation cuts across an individual’s volunteering before, during, between, or after employment practice. Teasing out similarities and differences, finding gaps, and removing prescriptive, hierarchical, and inappropriate attributes––while remaining focused on constructions of a volunteer and volunteering––creates a conceptual typology designed to advance volunteering-specific knowledge. It offers five coherent “explanatory types” of occupation-related volunteering to reorganize existing and new concepts (Cornelissen, Reference Cornelissen2017; Jaakkola, Reference Jaakkola2020), including continuing occupational development. This paper encourages discourses and research using clear concepts and language to answer outstanding questions.

Ironically, occupation-related volunteering is an under-explored topic in volunteering research. It is also striking that the body of knowledge on third-sector organizations’ governance, leadership, management, and operations misses the practice of occupation-related volunteering. The typology offers a framework to reflect occupation-related volunteering in praxis and support current and future volunteers and the individuals, groups, and organizations they benefit. Other fields grapple with the ever-changing social worlds of employment and occupations; the volunteering field can do the same, developing an understanding of occupation-related volunteering––volunteerability intersecting employability––across disparate organizational, cultural, and geopolitical environments.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no competing interests to declare relevant to this article’s content. The author certifies that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial or nonfinancial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The author has no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Ethical Approval/Informed Consent

The paper required no ethical approval or informed consent.

Data Transparency and Statement

Not relevant to a conceptual paper.