Introduction

With the development of modern medicine and the decrease in infectious diseases, people are living longer, yet are plagued with a variety of chronic diseases and disabilities.1 In the Global North, there is a trend of decreasing birthrate, an increasing number of older adults, and a growing number of natural disasters worldwide.Reference Cui, Peng and Shi2 With longer lives, many older adults enjoy independent living in their communities and homes. Yet, with older age, loneliness increases as adult children move away, friends and family pass, and one may experience decreased bodily functionality, resulting in diminished social interaction.Reference Ran, Wei, Yang and Yang3

Loneliness affects an individual in many different spheres of life. In 1990, Chicago experienced a prolonged heat wave affecting the whole city and its residents. The heat wave effectively killed many older adults living alone and experiencing social isolation.4 In recent years, loneliness has been labeled as an epidemic, having a significant impact on human health and dictating health outcomes.Reference Jeste, Lee and Cacioppo5 Loneliness can both exacerbate and increase vulnerability in natural disasters.Reference Van Beek and Patulny6, Reference Howard, Agllias, Bevis and Blakemore7

Older adults and people with disabilities are usually more at risk than able-bodied populations in natural disaster contexts. Older individuals face a higher likelihood of developing adverse mental illnesses and suffer from depression at an increased rate.Reference Chao8 Physically disabled individuals and those with chronic illnesses often struggle to manage their symptoms in the chaotic environment. Medication supply tends to be a challenge in disaster contexts, for people rarely evacuate with a comprehensive set of their medications or information on their medications.Reference Krousel-Wood, Islam and Muntner9 This can cause complications, making continued treatments for illnesses and disabilities more difficult, and making preparedness an essential step in hazard-prone areas.Reference Romaine, Peacock, Perry, Murphy and Krousel-Wood10 However, preparedness against disasters has been lower in older adult populations.Reference Liao and Hu11 Prior research lacked a thorough examination of the psychosocial impacts on older adults in disaster preparedness or risk perception, motivating our examination of this topic.

Background

Risk Perception and Loneliness

It is reasonably accepted in the literature that loneliness and its pervasiveness are public health concerns in many domains.Reference Fees, Martin and Poon12 Loneliness in older adults is known to be a more significant health concern than in any other age group.Reference Fees, Martin and Poon12 Older adults are generally more vulnerable due to increased loneliness and the health decline that comes with aging. Natural disaster introduces a layer of complications that may exacerbate the already high likelihood of loneliness and the health decline of aging.

A study examining how social isolation affects risk perception found that those who experienced more social isolation had a more unrealistic risk perception than those who did not experience social isolation.Reference Howard, Agllias, Bevis and Blakemore7

Loneliness and Protective Behavior

Prior studies show a relationship between loneliness and protective behavior, although the literature is minimal. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was observed that individuals who felt lonelier had less intention to engage in protective health behaviors.Reference Kang, Cosme, Pei, Pandey, Carreras-Tartak and Falk13 The same paper noted a significant positive relation with purpose in life and engaging in protective behaviors. Meaning in life was also associated with experiencing less loneliness. Loneliness is also a risk factor in a disaster context. In 1990, Chicago experienced a prolonged heatwave that affected the entire city and its residents. The heat wave killed many older adults living alone.Reference Klinenberg14 In recent years, loneliness has been labeled as an epidemic, having a significant impact on human health and dictating health outcomes.Reference Holt-Lunstad15 Loneliness can both exacerbate and increase vulnerability in natural disasters.Reference Kaniasty16

Preparedness and Recovery

Preparedness is crucial for recovery and health in disaster contexts. Research has shown that individuals with better disaster preparedness tend to recover more quickly and experience fewer adverse health outcomes following disasters.Reference Al-rousan, Rubenstein and Wallace17–Reference Andrade, Jula and Rodriguez-Diaz19 However, the relationship between loneliness, risk perception, and preparedness in the behaviors of older people remains understudied.

To understand this relationship, we surveyed Japanese adults in areas with high seismic risk to assess whether loneliness affects risk perception and preparedness behavior. This study is particularly relevant in the Global North, where older adults tend to be more independent than in the past, often living alone without the traditional family support structures.

Geographic and Environmental Factors

Many Japanese people live in coastal areas, which are particularly vulnerable to certain natural disasters, such as tsunamis and typhoons.Reference Arias, Bronfman, Cisternas and Repetto20 Despite the growing population of older adults in these regions, their specific needs are often not adequately considered in disaster planning and response.Reference Zhang, Bao, Deng, Wang, Song and Xu21

The environment, whether urban, suburban, or rural, also plays a significant role in experiences of loneliness and access to social support and other resources. Rural older adults may face unique challenges due to geographic isolation and limited access to services, whereas urban older adults may experience social isolation despite being physically proximate to others.Reference Kakiuchi22–Reference Chai, Han, Han, Wei and Zhao24

Post-Disaster Changes

Following disasters, loneliness can increase, along with depression and lower social capital, as observed after Hurricane Katrina and the Gulf oil spill. The phases of post-disaster community relationships often follow patterns of initial solidarity or increased altruism, followed by a return to baseline.Reference Daimon and Atsumi25

Model: Japanese Older Adult Preparedness Model (JOAPM)

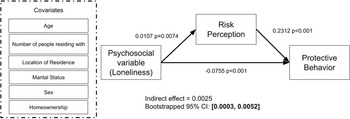

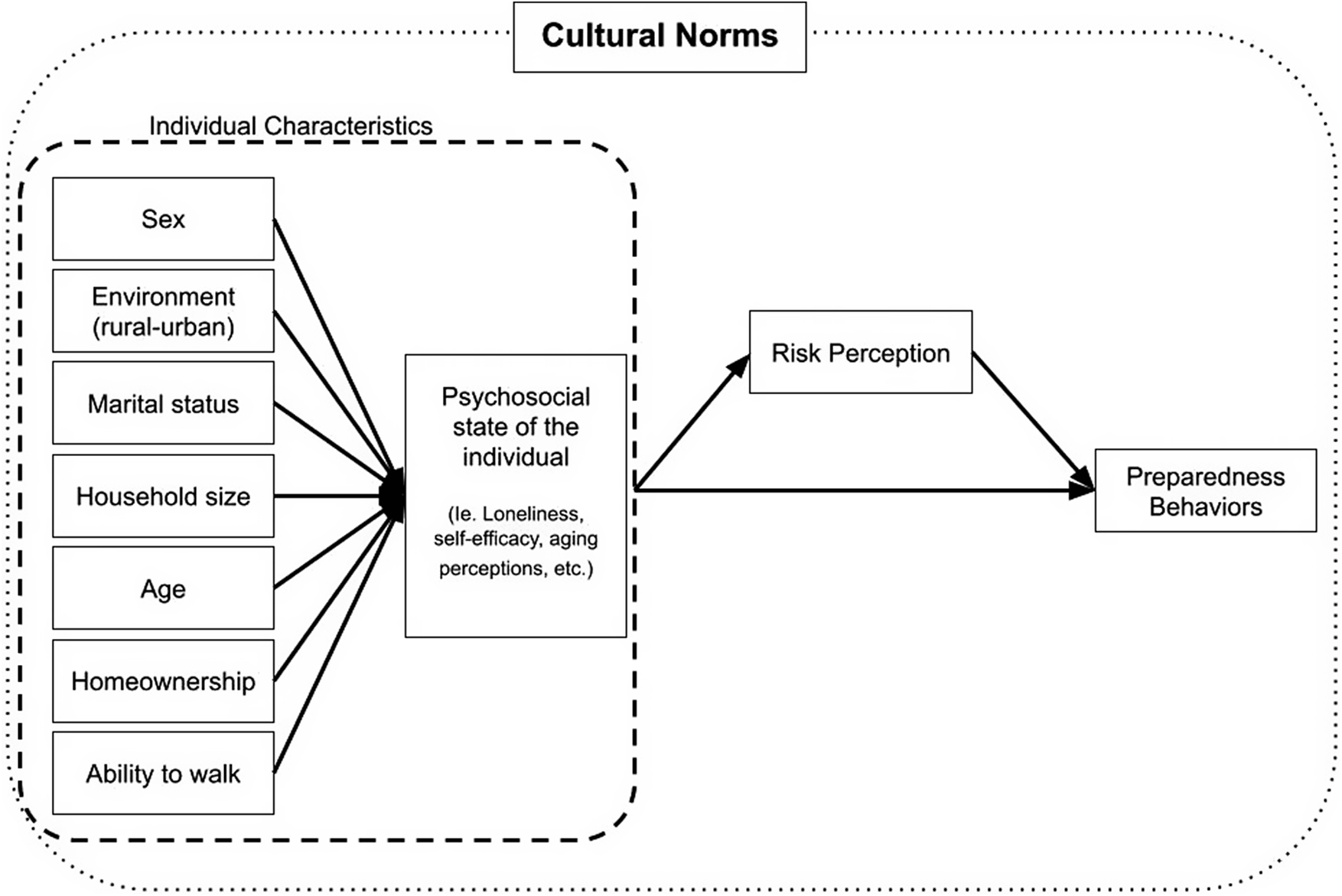

The Japanese Older Adult Preparedness Model (JOAPM) draws from Lindell and Perry’s Protective Action Decision Model (PADM) and emphasizes the influence of the social, environmental, and cultural context on shaping individuals’ risk perceptions, consequently leading to adjustments in preparedness actions (Figure 1). Reference Lindell and Perry26 Expanding on the PADM, the JOAPM adds the psychosocial component as a product of demographic variables and a predictor of risk perception and subsequent preparedness behaviors. The societal experiences and positions of older adults are often unique and rely on psychosocial cues.Reference Mather and Carstensen27 The JOAPM was mapped to explore how psychosocial elements, such as loneliness, affect the disaster perception and response of older adults, especially in Japan.

Figure 1. Japanese Older Adult Preparedness Model (JOAPM) drawing from Lindell and Perry’s 2011 Protective Action Decision Model (PADM).

Demographic Variables

Like the PADM, in the JOAPM, age, location of residence, marital status, and other individual characteristics inform the experience and risk perception, including exposure to information, attention, and comprehension, influencing the decision to engage in preparedness activities. However, in older adults, psychosocial variables, including but not limited to loneliness, self-efficacy, ageism, beliefs about aging, and changes in cognition and outlook, influence their views on risk perception and preparedness behaviors.

Psychosocial Variable

Psychosocial components are essential in these risk appraisal and preparedness models, as older adults are more sensitive to their social and psychological environments.Reference Cacioppo and Hawkley28 Psychosocial factors have been shown to affect older adults in a variety of pathways. In this study, we focused on loneliness in older adults.

Social isolation and loneliness are linked to a range of adverse health outcomes, including depression and cognitive decline, both of which can impair risk perception and reduce individuals’ capacity to prepare for natural hazards.Reference Lyu, Siu, Xu, Osman and Zhong29 Loneliness also lowers resilience by depleting the psychological and emotional resources necessary to manage stress.

In contrast, healthy older adults often exhibit greater emotional resilience and tend to focus on positive emotional experiences, a phenomenon known as the positivity effect. While this adaptive strategy supports emotional well-being, it can also contribute to an optimism bias, where individuals underestimate their vulnerability or overestimate their ability to cope in the face of disaster.Reference Mather and Carstensen27 Research has shown that even when presented with clear risk information, older adults may maintain unrealistic levels of optimism that can hinder preparedness efforts.Reference Sharot, Korn and Dolan30, Reference Mather and Knight31 This is particularly true when optimism serves a mood-regulation function, choosing not to focus on unpleasant realities.Reference Isaacowitz32

However, this protective optimism is fragile. When social isolation and loneliness are present, they can disrupt access to emotionally meaningful activities and diminish the motivation to engage with risk-related information. These psychosocial stressors may contribute to feelings of helplessness or disengagement, thereby undermining both emotional resilience and practical disaster preparedness.

Further complicating the issue, loneliness negatively affects self-efficacy, one’s belief in one’s ability to manage challenges, which is a key predictor of disaster preparedness. High self-efficacy typically supports proactive behavior. However, in the context of loneliness, even those with high self-efficacy may fail to act. Isolation can dampen motivation, reduce perceived social support, and limit opportunities to access or share preparedness information, ultimately lowering an individual’s confidence in their ability to prepare or respond effectively.Reference Hikichi, Tsuboya and Aida33–Reference Lee, Nersesian and Suen35

When optimism bias and loneliness coexist, they can erode both emotional resilience and practical preparedness by reinforcing disengagement, avoidant coping, and a false sense of security. These psychosocial dynamics highlight the need to consider cognitive capacity, knowledge, and emotional and social context when assessing older adults’ disaster readiness.

This study aims to better understand how loneliness affects risk perception and involvement in preparedness measures and how psychosocial states influence how older people relate to disasters. We examine demographic characteristics, including residence location (rural, suburban, or metropolitan), age, gender, etc., and their experience of loneliness. We then test the hypothesized direct relationship between loneliness and risk perception and preparedness.

Hypotheses

-

H1: Demographic characteristics affecting loneliness

-

a. A difference is observed in loneliness and different environments, with metropolitan areas experiencing higher loneliness in older individuals.

-

b. Older adults tend to be lonelier than younger older adults (younger older adults aged 55-64, middle older adults 65-74, older older adults 75+).

-

c. Females are more likely to experience loneliness.

-

d. Marital status is a protective factor for loneliness.

-

e. How many people they live with predicts loneliness; the more people they live with, the less lonely the individual.

-

f. Owning homes will reduce the likelihood of loneliness.

-

g. Inability to walk unassisted increases loneliness.

-

-

H2: Loneliness directly influences protective behaviors negatively.

-

H3: Loneliness is also inversely related to risk perception. Higher loneliness is associated with lower risk perception.

-

H4: Risk perception is positively associated with preparedness. The higher the risk perception, the likelihood of partaking in preparedness increases.

-

H5: Risk perception mediates the relationship between loneliness and preparedness.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Period

Study participants are Japanese. Japan is a rapidly aging country with one of the highest proportions of older adults worldwide.Reference Muramatsu and Akiyama36 With a higher proportion of older adults, protocols and methods for natural disaster preparedness must be adapted to meet the needs of older individuals, taking into account their disabilities, location of residence, social connectedness, and other factors.Reference Eisenman, Cordasco, Asch, Golden and Glik37 Using the Survey Research Center in Japan, we recruited 1,600 individuals from their representative pool of subjects. The survey targeted individuals over 55 years old living in 4 eastern and southeastern prefectures: Tokyo, Kanagawa, Kochi, and Wakayama. The 4 prefectures were selected to observe rural-urban differences in older adults across various social structural environments with similar earthquake risks.

The survey was administered online in April 2024. Using the Yamane sampling method, 400 people were sampled from each prefecture. Notably, a large earthquake and tsunami hit Noto, Japan, on January 1, 2024, killing just over 200 people, which may have affected risk perception and or protective behavior.

Measure

The surveys inquire about respondents’ demographic information, views on risk, household preparedness, and loneliness, among other variables. The JOAPM, inspired by the PADM, follows the logic that individual characteristics influence psychosocial processes, such as loneliness in this study (see Figure 1). These variables affect risk perception, which is the core predictor of preparedness behavior. This study measures preparedness through the average number of preparedness actions taken.Reference Tomio, Sato, Matsuda, Koga and Mizumura38

Loneliness is measured using the Abbreviated UCLA Loneliness Scale.Reference Allen and Oshagan39 The scale uses 7 items measured by a 4-choice Likert Scale that ranges from 1, “I do not feel this way,” to 4, “I feel like this often.” The 7 items ask questions such as, “I lack companionship” and “People are around me but not with me.” The loneliness variable is transformed into 1 variable by averaging the 7 items.

Risk perception is measured through the same set of questions that the government of Japan used in the pre- and post-Tohoku Earthquake and tsunami in 2011.Reference Fukurai and Ludwig40 The questionnaire consists of 4 questions that measure the perception of the degree of an earthquake’s effect. The items measuring risk perception include “I believe a very large earthquake that will devastate Japan is likely in the future,” or “the coming generations will experience more devastating disasters.” The risk perception will be consolidated into a single variable by averaging the scores of the 5 items. This will allow us to compare with the 2011 Tohoku data.

The response variables are protective behaviors. One is the insurance enrollment, answered with a binary “yes” or “no.” Another measurement is household preparedness, which is assessed by a binary response of “yes” or “no” to 6 questions, including “measures taken to secure furniture” and “discussed disaster response and plans with family.” The 6 items for household behaviors will be added to make a composite household preparedness score.

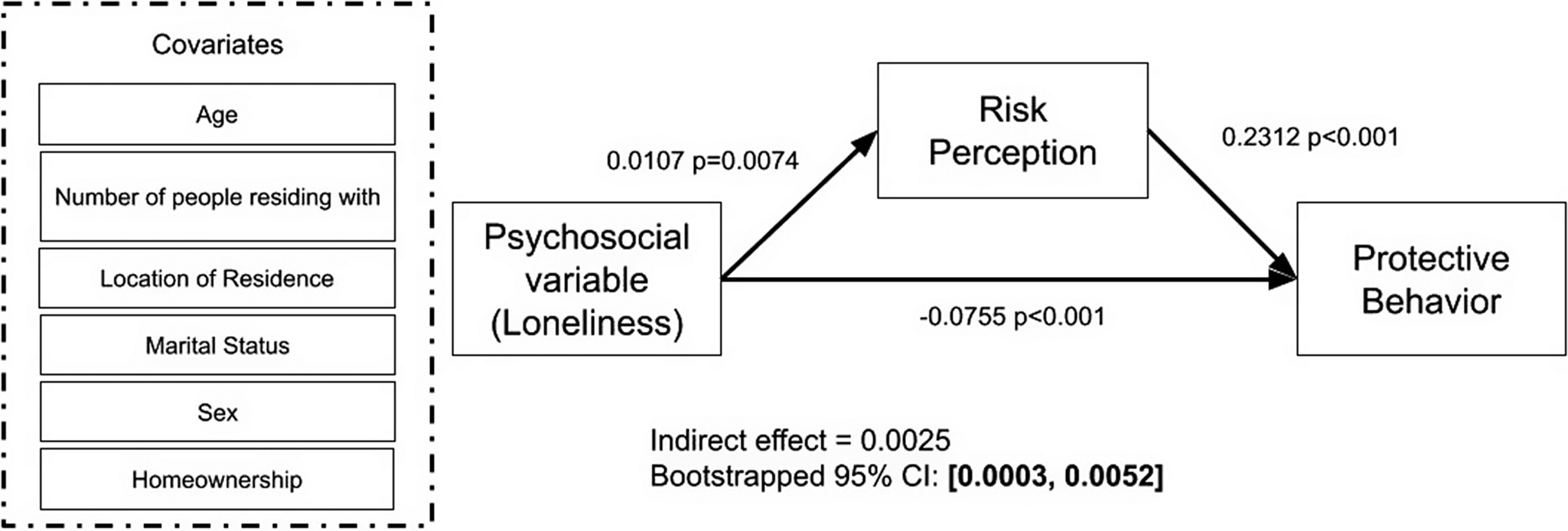

A simple mediation model assessed the relationship between risk perception and preparedness behaviors mediated by loneliness. This model identified Individual characteristics as covariates to isolate the relationship between loneliness, risk perception, and preparedness. Individual characteristics are the location of residence, marital status, homeownership, biological sex, household size, and age.

Procedure

The dataset reflects earthquake experiences and disaster attitudes, including risk perception and preparedness, focusing on earthquakes as a disaster.

The Survey Research Center distributed the questionnaire to its survey population of over 3 million people, which spatially represents the population of older adults (aged 55 and above) in 4 prefectures. The prefectures chosen—Tokyo, Kanagawa, Wakayama, and Kochi—were selected because they all face the Pacific Ocean and have a similar earthquake and tsunami risk, and capture both rural and urban areas.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate analyses were conducted using t- and chi-square tests to explore the relationship between protective behavior, risk perception, various demographic variables, and loneliness. A one-way ANOVA was also employed to test the relationship between demographic variables and loneliness.

We employed Hayes’ Process Model 4 in SPSS to conduct the mediation analysis, using 5,000 bootstrap samples to generate 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effect.Reference Zhang, Bao, Deng, Wang, Song and Xu21

First, the relationship between loneliness, earthquakes, and risk perception is tested. It is hypothesized that loneliness will alter the perception of the risk of future earthquakes. Additionally, the relationship between loneliness and household earthquake preparedness is examined by testing whether there are significant changes in the number of protective behaviors practiced. The relationship between risk perception and protective behavior was also investigated. Then, the total effect of the mediation model was calculated to determine whether loneliness affects protective behavior through altering risk perceptions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mediation model with the relationship between loneliness and preparedness behaviors mediated by risk perception. No significant relationship was found between loneliness and risk perception. A significant relationship was found between risk perception and preparedness, as well as between loneliness and preparedness (in the form of a direct relationship).

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 29.

Ethics Statement

The University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board (IRB) in Human Subject Research approved all analyses of this paper.

Limitations in the Methodology

The survey participants are collected from a pool of registered subjects in Japan. They were randomly selected to reflect the population of each area, considering income and age. The population surveyed is representative of the older population in each prefecture. Representation of the data is limited as the survey was administered via the web, which may skew the results due to the ability to use computers and the access to disaster information provided by the internet.

Result

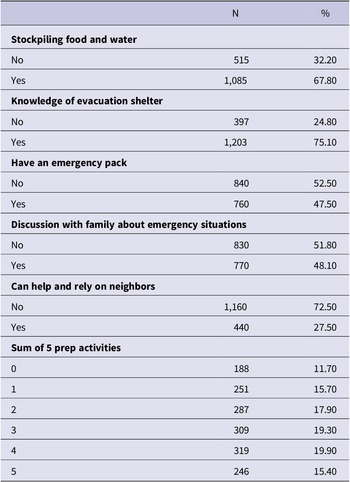

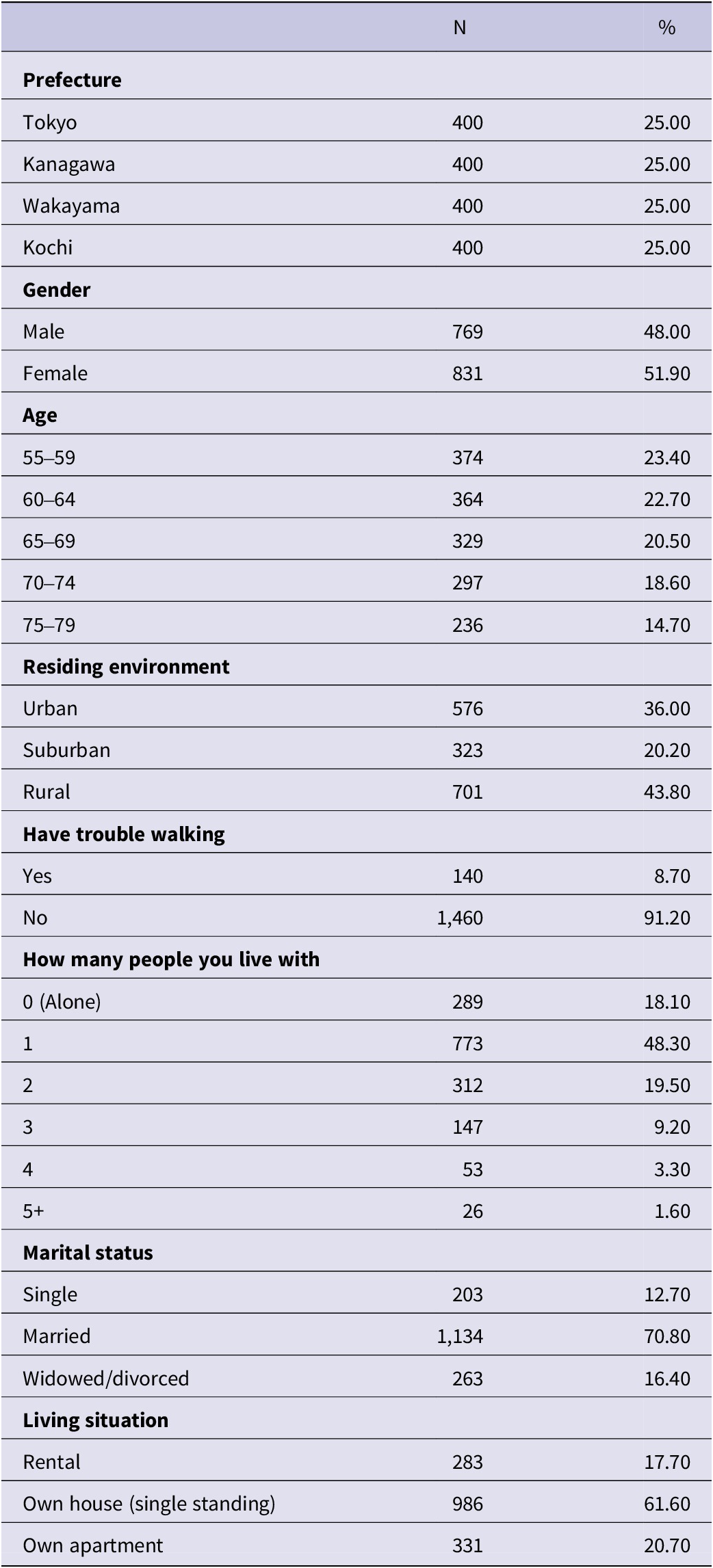

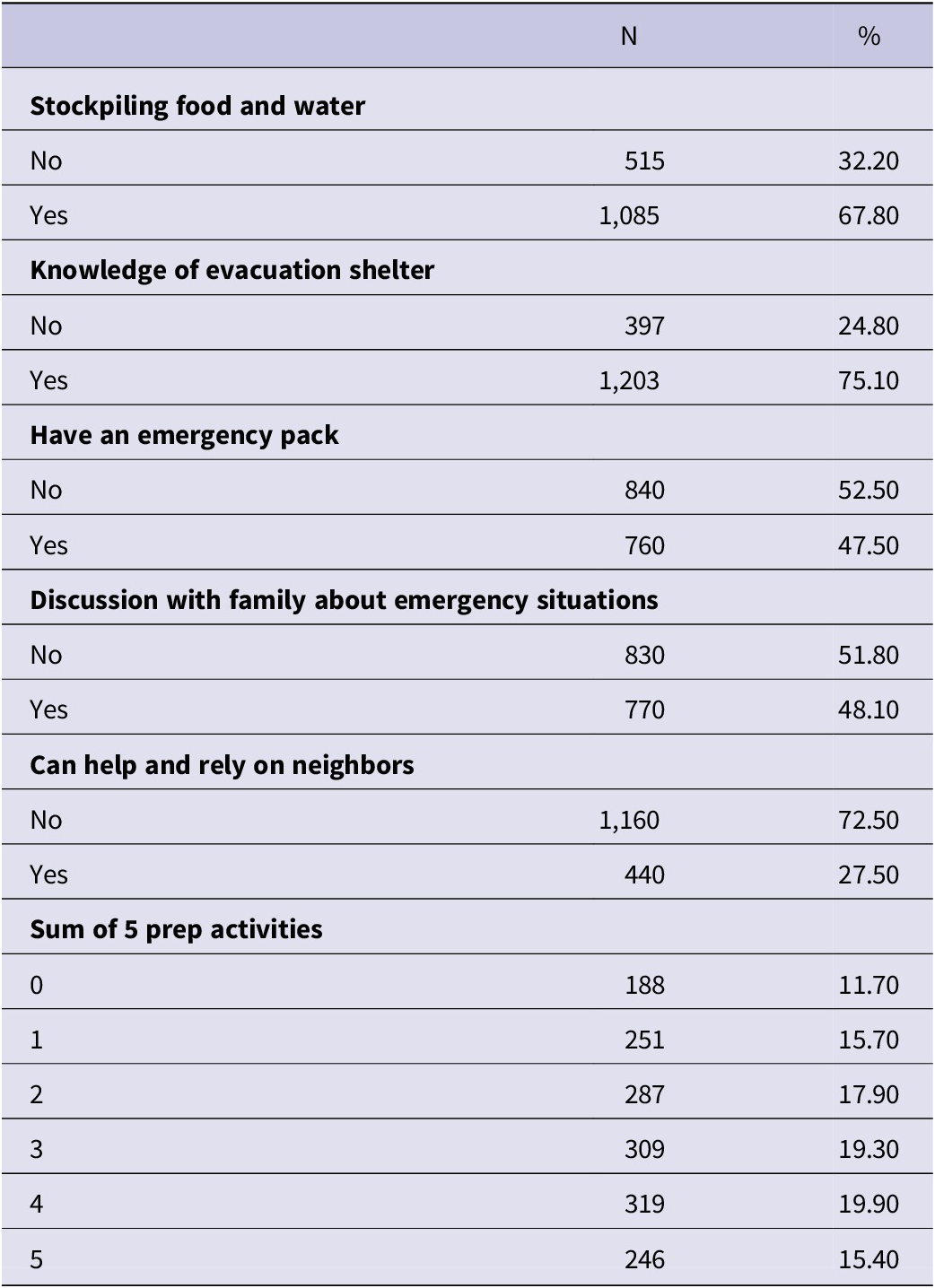

The population of interest was aged between 55 and 79, with 400 individuals sampled from each region to ensure representation. In terms of residence, 576 individuals identified as living in an urban area, 323 in suburban areas, and 701 in rural areas. Regarding marital status, 203 were single, 1,134 were married, and 263 were widowed or divorced (see Table 1). The participants were asked about their participation in 5 preparedness activities, to which they either responded with a yes or a no. Over 85% of the participants had taken action in at least 1 preparedness behavior, and over half the participants had participated in 3 or more (see Table 2).

Table 1. Demographic information

Table 2. Preparedness behaviors partaken

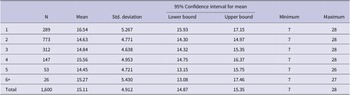

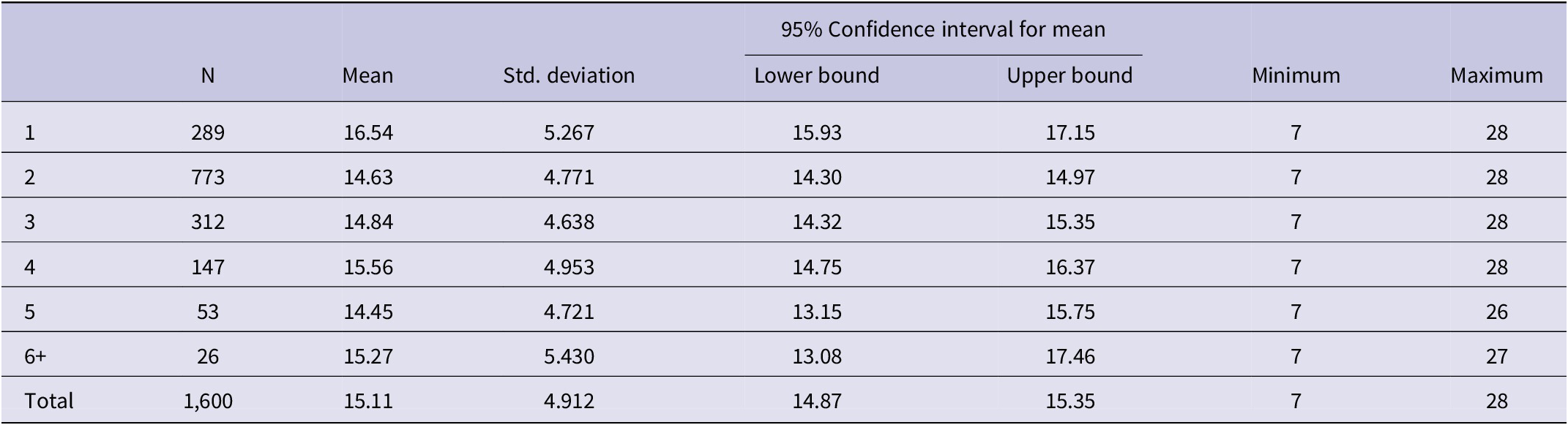

A bivariate analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in loneliness between the areas. As expected, marital status revealed a significant difference (F = 25.92, P < 0.001) in loneliness, with singles reporting the highest level of loneliness and married couples reporting lower loneliness scores, on average. People who rented reported significantly higher levels of loneliness compared to those who owned their residences. Adults who lived with more than 1 person experienced less loneliness, on average (see Table 3).

Table 3. Average loneliness levels by household size

Conducting an ANOVA between different living environments —rural, suburban, and metropolitan areas—and loneliness, we found that living environments have minimal significance or effect on loneliness. A general trend of loneliness is increasing as the environment becomes more rural.

Loneliness directly influences the number of protective actions taken. Loneliness has a direct, negative impact on preparedness: as loneliness increases, people take fewer preparedness actions (−0.0755, P < 0.001). Risk perception (0.2312, P < 0.001) has a more substantial influence on preparedness activities than loneliness does. In other words, people who perceive higher risk tend to engage in more preparedness actions (see Figure 2).

Analyzing the mediating role of risk perception between loneliness and protective behavior, we observed that loneliness does, in fact, slightly increase risk perception (0.0107, P = 0.0074). Since higher risk perception leads to more preparedness, loneliness indirectly increases preparedness by a small amount (0.0025).

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that loneliness is inversely associated with disaster preparedness. Individuals reporting higher levels of loneliness were less likely to engage in protective actions such as preparing emergency packs, securing furniture, or stockpiling supplies. While existing research on the relationship between loneliness and disaster preparedness is limited, this finding aligns with broader literature, suggesting that loneliness diminishes self-efficacy and is linked to lower participation in health-promoting and risk-reducing behaviors.Reference Hawkley and Cacioppo41 Loneliness may reduce one’s motivation or confidence to engage in protective actions due to feelings of helplessness or a lack of perceived support.

Interestingly, our results show that loneliness is positively associated with risk perception, albeit weakly. This partially contradicts some prior findings that suggest socially isolated individuals tend to underestimate risks due to lower exposure to informal information networks.Reference Howard, Agllias, Bevis and Blakemore7 However, other studies during the COVID-19 pandemic noted that loneliness was linked to heightened risk perceptions, mainly regarding financial or existential threats.Reference Okruszek, Aniszewska-Stańczuk, Piejka, Wiśniewska and Żurek42 Loneliness may contribute to elevated anxiety, which may heighten sensitivity to environmental threats.

Despite this slight increase in risk perception, the indirect positive effect of loneliness via risk perception on preparedness was not as strong as the direct negative impact of loneliness on protective behaviors. This suggests that although lonelier individuals may feel more at risk, they remain less likely to translate this concern into preparedness actions—perhaps due to reduced self-efficacy, lack of motivation, or diminished social resources.Reference Holt-Lunstad15, Reference Kaniasty16 This dual pathway highlights the complexity of psychosocial influences in disaster contexts and contributes to the limited but growing literature on loneliness in emergency preparedness.Reference Kaniasty, Urbanska, Williams, Kemp, Porter, Healing and Drury43, Reference Kaniasty and van der Meulen44

These findings have theoretical implications for JOAPM. While the PADM emphasizes cognitive appraisal (e.g., risk perception) as a precursor to protective action, our results suggest that emotional and social variables, such as loneliness, may modify this pathway. Specifically, loneliness might shape risk perception but simultaneously inhibit behavioral follow-through. This disconnect emphasizes the need to expand preparedness models to incorporate psychosocial and affective dimensions more comprehensively, particularly among aging populations.

Our demographic findings offer additional insights. Contrary to some assumptions, no significant differences in loneliness were found across urban, suburban, and rural environments, although a slight trend indicated higher loneliness in rural areas. This supports previous research suggesting that relational factors such as marital status, cohabitation, and housing stability are stronger predictors of loneliness than geographic context.Reference Van Beek and Patulny6, Reference Sparks, Kulcsár and Curtis45 For example, married individuals and homeowners reported significantly lower loneliness scores, consistent with findings that social connection and residential security buffer against emotional distress.Reference Guthmuller46 With lower levels of loneliness, we found that the likelihood of individuals who partake in protective measures against earthquakes is higher.

Regarding risk perception and preparedness, gender and age emerged as significant predictors. Women and older individuals were more likely to take preparedness actions, which supports past research showing that women often engage more in health- and safety-related behaviors.Reference Thompson, Little and Kim18, Reference Flynn, Slovic and Mertz47, Reference Cvetkovic, Roder, Ocal, Tarolli and Dragicevic48 However, these same demographic groups did not necessarily perceive higher levels of risk, suggesting that other mechanisms, such as social roles or cultural expectations, may influence preparedness behavior independently of risk perception.

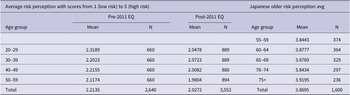

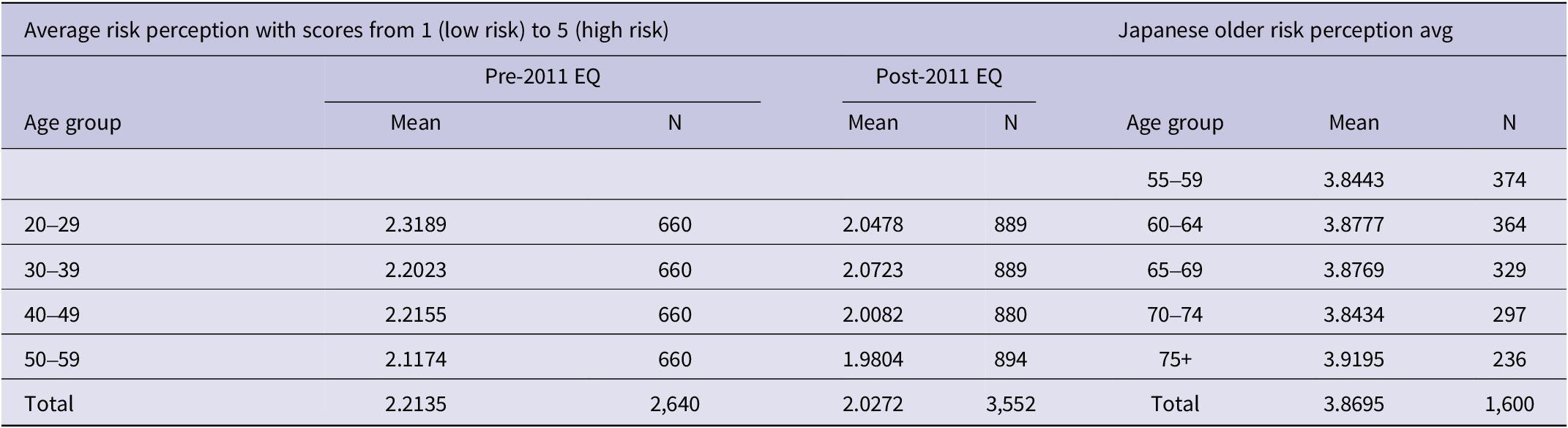

Compared to the 2011 surveys administered to Japanese residents before and after the Tohoku earthquake, using the same items to measure risk perceptions, older adults generally tend to perceive higher risk compared to older individuals in this study. This data agrees with the existing literature, as older adults tend to perceive a higher risk. However, in January of 2024, there was a large earthquake and tsunami in Noto, affecting many older people. This could have affected older adults’ risk assessment (see Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of age groups’ risk perception. Pre- and post-2011 Tohoku EQ and 2024 post-Noto

These results have practical implications for the emergency preparedness, planning, and outreach of older adults. Disaster preparedness strategies must address emotional and social barriers, not just informational availability, as the PADM focuses on, in terms of social context. Interventions for older adults should include social support mechanisms, such as community buddy systems, facilitated family conversations, and outreach to individuals living alone. Preparedness messaging tailored to individuals experiencing loneliness may need to emphasize personal agency and achievable action steps, particularly in the absence of immediate social networks.Reference Kaniasty16, Reference Annear, Otani, Gao and Keeling49

The cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and the online survey format may have biased the sample toward more digitally literate individuals who are possibly less isolated. Additionally, cultural variability in how loneliness, risk, and preparedness are experienced and reported may affect generalizability beyond Japan.Reference Bodas, Peleg, Stolero and Adini50 The reliance on self-reported measures increases the possibility of recall or social desirability bias.

Future Direction

Future research should explore alternative psychosocial mechanisms, such as purpose in life, trust in others, and perceived social capital, which may mediate the relationship between loneliness and preparedness.Reference Kang, Cosme, Pei, Pandey, Carreras-Tartak and Falk13, Reference Kinoshita, Nakayama, Ito, Moriyama, Iwasa and Yasumura51 Longitudinal studies would enable researchers to examine how these relationships evolve before and after disaster events and whether specific interventions, such as strengthening neighborhood ties or increasing social participation, can mitigate the loneliness-related preparedness gap. Another study could survey the populations of older adults across other countries with differing risk mitigation capacities, comparing their communication, understanding of risk, loneliness, and protective behaviors. For example, nations in the Pacific Rim, such as the Western United States and the Southern hemisphere, face high risks of earthquakes.

Understanding how loneliness and related constructs like self-efficacy and optimism bias operate across different cultural contexts remains underexplored. Community values, social connectedness, and cultural narratives around self and responsibility all shape risk perception and preparedness in diverse ways. A culture’s influence on the perception of loneliness can also influence group consciousness and political engagement. For example, literature has found that in a more collective society, a decision reached by trusted leaders will be a cue to action for behavior such as community-wide drills.Reference Iyengar and Lepper52 Meanwhile, individual agency and motivations tend to predict behaviors in a society that values individual decisions.Reference Earley53

Loneliness is also a factor that needs to be addressed pre- or post-disaster; we must value the needs of elderly individuals in general. In a society that values productivity and often measures the value of people by their individual contributions to society, it can be challenging to form relations and focus and allocate the already scarce resources to vulnerable populations.Reference Otani54 A more significant challenge may be encouraging the shift in social attitudes toward the elderly and the value they can provide, particularly in terms of productivity.

Conclusion

This study is among the few empirical studies examining the relationship between aging, earthquake risk perception, and preparedness, with a specific focus on how psychosocial factors, such as loneliness, might affect behaviors. The findings reveal that loneliness has a complex impact on disaster preparedness among older adults, slightly increasing risk perception but significantly reducing the likelihood of taking protective actions.

As societies worldwide age and climate-related disasters become more frequent and severe, it is urgent to understand how emotional and social vulnerabilities may impact disaster readiness. Integrating psychosocial factors in emergency planning is not just a public health issue but also one of equity and resilience.

Future research must further explore the unique effects of loneliness to illuminate the complex relationship between experiencing old age, loneliness, self-efficacy, optimism bias, and information attainment. These factors are crucial in comprehensive disaster preparedness and could further enhance disaster preparedness in community-dwelling adults.

This study investigated the role of loneliness in shaping earthquake risk perception and preparedness behavior among older adults in Japan. We created the Japanese Older Adult Preparedness Model (JOAPM), which was informed by the Protective Action Decision Model (PADM).Reference Cacioppo and Hawkley28 Our findings reveal a complex interplay between psychosocial and behavioral variables, with loneliness exerting both direct and indirect influences on preparedness actions through its relationship with risk perception.

Acknowledgments

Support from the Wen Public Health Dean’s Graduate Fellowship (MF) and the California Institute of Hazards Research MRP (LGL).

Author contribution

Mihoka Fukurai: Writing—original draft, formal analysis.

Lisa Grant Ludwig: Writing—review and editing, supervision, conceptualization.

Competing interests

None.