On 9 October 2019, Robert Ssentamu, popularly known by his stage name Bobi Wine, made a dramatic escape from the police. In a video that was circulated on Ugandan social media, Bobi Wine is seen in a chaotic crowd of people on the streets of Kampala. Among the crowd is a police officer, and Wine is gesturing wildly with his arms. Clearly, a verbal altercation is taking place between him and the officer. That very morning, Wine had posted photographs on social media showing police barricading his home in an attempt to block a concert that was planned at his private property in Busabala. With police preventing Wine’s fans from coming to him, his appearance in the city made it clear that they did not successfully block him from going to his fans. Instead of acquiescing to the authority of the police, Bobi Wine hops on the back of a boda,Footnote 1 the driver speeds away, and the Afrobeat star-turned-presidential candidate stands up as he rides on the back of the motorbike with his fist raised to scores of cheering onlookers.Footnote 2

Since declaring his bid for the Ugandan presidency a few months earlier in July 2019, Wine had become a thorn in the side of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party. While President Museveni, in power since seizing it after prolonged civil conflict in 1986, had been challenged before, Bobi Wine’s campaign seemed to reinvigorate opposition politics in the country. Leading a movement he called People Power, Wine used his music, along with his upbringing in what he described as the Kamwokya ‘slum’ of Kampala, to reach youth across Uganda. This captured the hearts and imaginations of many international journalists, with profiles of Wine appearing in popular media outlets ranging from The New York Times and Rolling Stone to the BBC and France 24. While some journalists and academics compellingly argued that People Power’s popularity owed much to opposition figures of the past, most especially Kizza Besigye and the Forum for Democratic Change party (Broadway Reference Broadway2019; Khisa Reference Khisa2023; Pier and Mutagubya Reference Pier and Mutagubya2023; Wilkins et al. Reference Wilkins, Vokes and Khisa2021), this did not stop others from labelling Wine’s momentum as unprecedented (Schneidermann Reference Schneidermann2021; Woldemikael Reference Woldemikael2018).Footnote 3 Regardless of your side of the debate, the excitement that youth felt for Wine during the time of the viral video was palpable on the streets of Kampala.

This article focuses less on Bobi Wine himself, and more on the people who made possible the escape elaborated in the opening paragraph. It was a boda driver who enabled Wine to ride through the streets of Kampala that day, defying police with his fist raised and signature red beret securely atop his head. As presidential campaigning began, crowds of boda drivers would ride through the city with their horns blaring, encouraging onlookers to join People Power. Any person who has spent time in Uganda’s capital will be familiar with boda drivers and their role in the city. From their hypervisibility (Courtright Reference Courtright2023), to their entanglements with moral economies (Doherty Reference Doherty2020), to their ability to circumvent traffic and create alternative mobilities (Evans et al. Reference Evans, O’Brien and Ng2018) and to the ways in which the drivers assert their masculinities (Nyanzi et al. Reference Nyanzi, Nyanzi-Wakholi and Kalina2009), motorbike drivers in Kampala and throughout Uganda have long been subjects of ethnographic and academic enquiry. Boda drivers reflect Kampala as a ‘modern city’, an embodiment of the ‘flow and motion’ of capitalism (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2004: 377). Goodfellow stresses that boda drivers are a predominant force in Uganda’s informal economic sector, explaining that ‘boda-boda drivers were often labelled foremost among the city’s “untouchables” – groups that the state effectively could not touch because they were protected by a range of powerful interests’ (Goodfellow Reference Goodfellow2015: 136). Goodfellow argues that boda drivers are a key voting constituency for President Museveni, and he cites Museveni’s reluctance to effectively tax boda drivers as evidence of their importance for the NRM. Because of their ubiquity, outward shows of support for the ruling regime, such as the donning of signature-yellow NRM clothing, are as important as votes themselves. In the weeks following the video of Bobi Wine’s escape, however, police rounded up scores of drivers and their bikes in what appeared to be a series of retributive acts for the viral video. Suddenly, all boda drivers were potential Wine supporters.

Aesthetic interruptions and the politics of seeing

Based on long-term ethnographic fieldwork conducted in the summer of 2017 and in 2019–20, this article argues that the aesthetics of boda drivers offer new ways of theorizing how people are imagining Ugandan state pasts and futures. The visual markers discussed below range from stickers on helmets to T-shirts worn while riding to flags pinned to motorbikes; rather than name such aesthetic markers as political or ‘everyday’ (Scott Reference Scott1985) resistance, I call them aesthetic interruptions. I use aesthetic interruption to conceptualize visual displays that disrupt widely held assumptions about political action and affiliation. Whether drivers had ‘People Power’ patches sewn on their jackets or were displaying photographs of Idi Amin on their helmets, all were using visual cues that symbolized their distinct, alternative visions for Uganda’s political future. For Bobi Wine supporters, that future was inextricably linked to his presidency; for those donning photographs of Amin, a secure future could be better imagined through strongmen of the past. The hypervisibility of boda drivers made these obvious political symbols critical tools that such drivers knew people would see every day as they navigated the city. I argue that the divergent political visions offered by the aesthetic interruptions that drivers displayed must be understood through the cosmopolitanism of Kampala and the continued potency of ethnicity, and I use Rancière’s theory of the distribution of the sensible (Reference Rancière2018 [Reference Rancière2006]) to wrestle with the varying imaginaries of Ugandan political pasts and futures.

During the time when fieldwork for this article was conducted, exerting political agency in ‘traditional’ ways was near impossible. Section 8 of Uganda’s Public Order Management Act 2013 was still law, which granted ‘sweeping powers to arbitrarily prevent or stop public gatherings organized by opposition politicians, and to crack down on protests’.Footnote 4 Throughout the city, anything perceived as political campaigning was swiftly broken up by the police. This did not stop Wine supporters from making their presence known, but it did make large marches or sit-ins difficult to sustain, as participants faced assault and arrest. The absence of sustained physical gatherings that would immediately be recognizable as political protests made the aesthetic choices of drivers even more critical during this time. Aesthetic interruptions to power enabled drivers to act as a collective without explicitly breaking the law, while still daring to show their dissatisfaction with the government.

The degree to which Wine’s campaign affected Museveni was also evident after the government created its first ever gazette of military clothing. Exemplifying the importance of aesthetics in campaigning, the punishment for citizens donning any of the clothing items identified in the gazette was life imprisonment.Footnote 5 The ruling regime argued that military-style garments could deceive the public as ordinary citizens could be mistaken for soldiers, but those same ordinary citizens were not deceived by the ban or by the disproportionate punishment for its infraction. Among the banned clothing were seemingly harmless items such as camouflaged baseball hats and Museveni’s signature bush hat, but most importantly for People Power, the red beret that had become inextricably linked to Bobi Wine was also included. People saw the gazette as a transparent attempt to suppress visible support for the opposition candidate.

In the weeks and months following the ban on the red beret, many boda drivers openly defied the law and continued to wear it. But others did not want to risk arrest, especially due to the threat of life imprisonment that accompanied it. Instead of rejecting the law altogether, some boda drivers chose aesthetic interruptions. Far from acquiescing to Museveni’s power, they found creative ways to work within the limits of the law to show their disapproval. On the back of one driver’s black helmet was ‘People Power’ handwritten in bright red paint; another had a sticker that read ‘Mission: Free Uganda, 2021’; and numerous others had stickers of Wine himself.Footnote 6 Working within the limits imposed by the release of the gazette, boda drivers continued to make their politics known.

This article not only is concerned with interruptions to power, but also interrogates why certain forms of politics remain relatively invisible in Kampala. While it is certainly not my intention to offer a defence for the ruling regime, it is my intent to take seriously those who refrained from supporting Wine, or even professed loyalty to the NRM when such a view seemed unthinkable. Jacques Rancière argues, ‘Politics revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of space and the possibilities of time’ (Reference Rancière2018 [Reference Rancière2006]: 13). The boda drivers who are the focus of this article are young men living in precarious economic circumstances, and their aesthetic choices enable a re-theorizing of contemporary Ugandan politics. Particularly with regard to the 2021 Ugandan elections, Bobi Wine’s domination of international headlines made it appear as though every ‘ordinary’ Ugandan would cast their vote for the opposition candidate, easily defeating President Museveni if only there were free and fair elections. I am far from arguing that Wine could not win the presidency; rather, I am using Rancière’s theory of the distribution of the sensible to take seriously the divergent political opinions among boda drivers.

While Rancière’s theory allows us to interrogate what is seen and what is hidden within a specific time and place, Raymond Williams’ conception of dominant, residual and emergent within an ‘“epochal” analysis’ (Reference Williams2009 [Reference Williams1977]: 121) allows for a theorization of the competing interpretations of Museveni’s long rule, and his challengers. For those invested in the future of Uganda, Bobi Wine’s campaign could be theorized as an emergence of something new, although the emergent is not easily identifiable:

The process of emergence … is then constantly repeated, an always renewable, move beyond a phase of practical incorporation: usually made much more difficult by the fact that much incorporation looks like recognition, acknowledgment, and thus a form of acceptance. In this complex process there is indeed regular confusion between the locally residual (as a form of resistance to incorporation) and the generally emergent. (Williams Reference Williams2009 [1977]: 124–5)

As discussed above, there were many journalists and academics (Khisa Reference Khisa2023; Pier and Mutagubya Reference Pier and Mutagubya2023; Wilkins et al. Reference Wilkins, Vokes and Khisa2021) who rejected Wine’s campaign as a break from the past and instead viewed it as a local residual of Besigye’s long-time opposition to Museveni. I now turn to the lived experience of Kampala as a cosmopolitan, multiethnic city to further argue why we must allow emerging understandings of the city to come to the surface.

Cosmopolitan Kampala

It would be misleading to present all motorbike drivers as Wine supporters. Wine’s ethnic identity as a Muganda, the largest ethnic group in Uganda, was a source of consternation for non-Baganda people worried about Ganda hegemony in the country. It is, of course, overly simplistic to attribute voting patterns or political support solely to ethnic identity,Footnote 7 but Wine himself has understood the potency of ethnicity in Uganda throughout his political career. His insistence on moving beyond ‘tribal’ divides points to the continued existence of ethnic tensions, and the efforts he has made to reach non-Luganda-speaking fans show the importance of garnering support across ethnic lines. Using the internet to reach his fans while he was under house arrest, he would translate his lyrics for non-Ganda fans who might be watching his livestreaming sessions.Footnote 8 Yet, boda drivers from a diverse array of ethnic groups remained unconvinced that Bobi Wine was anything other than a Ganda nationalist.

Kampala is situated within the physical territory of Buganda, the largest and most dominant kingdom in Uganda throughout the colonial period. Because of the significance of the kingdoms in Uganda, and as Kampala is within the territorial bounds of Buganda, it is tempting to view the city as the centre of ‘a Ganda-centric world’ (Reid Reference Reid2017: 149). Scholarly work has approached Kampala using Ganda cosmologies and cultural particularities (Doherty Reference Doherty2021; Wyrod Reference Wyrod2016; Zoanni Reference Zoanni2019), while those studying other parts of the country (Behrend Reference Behrend1999; Doyle Reference Doyle2006; Dubal Reference Dubal2018; Mamdani Reference Mamdani1976) have often used the lens of ethnic groups from their respective places of study, thus separating the country’s population into regional groups. The historical significance of Buganda, and the ways in which it was both favoured and manipulated by British indirect rule, has been the subject of many historical works (Hanson Reference Hanson2003; Ray Reference Ray1991; Reid Reference Reid2002; Wrigley Reference Wrigley1996). Obote’s decision to abolish all kingdoms within Uganda after he seized power in a coup d’état in 1966 was motivated by the power that the Buganda kingdom maintained. Suspicious about the power of ‘ethnic patriotism’ (cf. Peterson Reference Peterson2012), Obote and his circle feared that ethnic separatists and traditionalists would be a threat to national unity and dilute their capacity to forcefully construct a postcolonial Ugandan national identity. The king of Buganda, the kabaka, was sent into exile, and remained so as successive regimes with rulers from the ‘martial races’ (Streets-Salter Reference Streets-Salter2004) of Northern Uganda refused to recognize the kingdom. It was not until President Museveni re-established the kingdom in 1993 that the kabaka could return home, a source of great jubilation for Baganda. While President Museveni and his ruling NRM may have thought that re-establishing the monarchies in Uganda would appease potential voters, giving Baganda a semblance of control over their cultural life, such appeasement has not led to a lessening of allegiance to the monarchy. As Golooba Mutebi argues, ‘The tremendous loyalty [the monarchy] commands cannot and should not be dismissed as only a reaction to the incompetence of the central government’ (Golooba Mutebi Reference Golooba Mutebi2011: 12).

Unlike the ‘strongmen’ of the past who hailed from Northern Uganda, Museveni identifies as a MunyankoleFootnote 9 from Western Uganda, and contemporary prejudices against Western ethnic groups have come to mirror the resentment that has built against the president over the course of his decades-long rule. Many Baganda lament that there has yet to be a Muganda president, even though, in fact, the first president of Uganda (1962–66) was king of Buganda Kabaka Mutesa II, until he was overthrown by Obote in 1966. A first-year student complained, ‘We are the most developed tribe and yet we have never led the country since independence.’ The feeling of deserving a chance to rule contemporary Uganda was evident in many conversations I had with young Baganda men, and this added excitement to the possibility of a Bobi Wine presidency.

The linguistic dominance of Luganda sometimes conceals Kampala’s diversity. Throughout fieldwork, I was confronted with the ways in which the city could not function without ethnic minorities from across the country. Everywhere I went, I met non-Ganda minorities who had moved to Kampala in search of wage labour. The city’s ethnic diversity was also evident from casual suppositions people make in everyday life: security guards are assumed to be from Northern Uganda, bar owners are thought to be from Western Uganda, ‘white collar’ jobs are expected to go to Central Ugandans, and police are presumed to be from Eastern Uganda. Such stereotypes have a long history and date back to the way in which British colonial authorities often used members of particular ethnic groups for certain jobs. Such assumptions are not value-neutral and the weight of post-independence ethnic tensions is evident in the discerning ways in which people choose their motorbike taxi drivers, greet their co-workers, or accuse others of witchcraft or stealing. Indeed, such stereotypes are also reflected in how certain groups of people are considered more qualified or desirable to be national leaders.

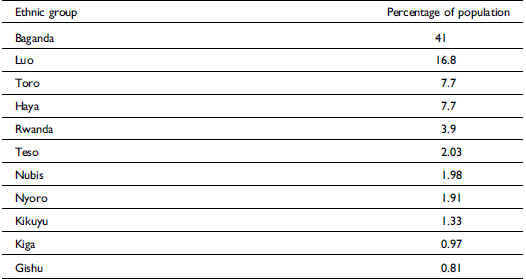

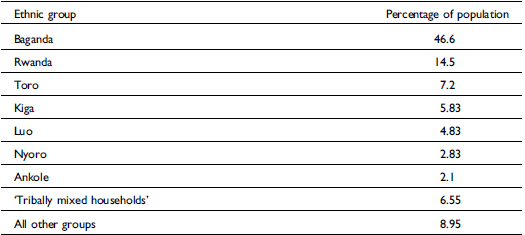

Although Kampala’s importance to the kingdom of Buganda is longstanding and the city served as the kingdom’s capital, it was Frederick Lugard’s arrival in 1890 that would make it the centre of the entire Uganda Protectorate. In a direct challenge to Kabaka Mwanga’s sovereignty, who was the king of Buganda at the time, Lugard camped on a Kampala hill until Mwanga formally accepted British ‘protection’. This made it a centre for political and commercial activities and led to an influx of migrants from other parts of the protectorate (Southall and Gutkind Reference Southall and Gutkind1957: 1–3). Sometimes ethnic tensions do emerge across the city. When a friend from Karamoja came to Kampala for temporary employment, he expressed frustration at having to spend time among Baganda people. ‘They think the city belongs to them,’ he stated, stressing that Kampala is the capital city for all of Uganda, not just for its majority group, and Ugandans from all over the nation live and work there. If ethnic minority migrant workers allow Kampala to function, he insisted that they all should have the right to the country’s capital. Tables 1 and 2 show ethnic diversity in Kampala’s Kisenyi and Mulago neighbourhoods in 1957.

Table 1. Ethnic groups in Kisenyi, 1957.

Source: Southall and Gutkind (Reference Southall and Gutkind1957: 27).

Table 2. Ethnic groups in Mulago, 1957.

Source: Southall and Gutkind (Reference Southall and Gutkind1957: 107–8).

Kampala’s ethnic diversity clearly pre-dated Uganda’s independence. A study conducted nearly twenty years later in Kisenyi found similar ethnic diversity (Halpenny Reference Halpenny and Parkin1975). Any attempt to grapple with boda drivers and the aesthetic choices they make must contend with Kampala’s ethnic cosmopolitanism. The continuing linguistic dominance of Luganda within the city indexes the group’s cultural control, yet Kampala is a place that can only be understood through its ethnic diversity. The city’s many boda drivers reflect this ethnic diversity, which often maps onto divergent views about the country’s future. And despite Bobi Wine’s conscious efforts at his political rallies and in his music to address Uganda and the capital’s diversity, groups of Baganda boda drivers could often be heard saying things like ‘Twagala ebyaffe [We want ours]!’ For non-Baganda, especially those from Western Uganda, where President Museveni comes from, those words evoked fear. Boda drivers such as Simon, discussed below, expressed concern about the potential for ethnic purging if Bobi Wine came to power. They insisted that all Banyankole were believed to support the ruling regime, and their ethnicity tied them to Museveni regardless of their actual political leanings.

Breaking Baganda hegemony

For drivers from the North who did not support Museveni nor believe that Wine was a strong enough candidate to fix Uganda’s corrupt political system, other strongmen featured on the stickers of choice for their bikes. They were not particularly concerned about retaliation if Bobi Wine won the presidency; rather, they feared that the entire country might dissolve into chaos. During two short visits to the Karamoja district in the North in late 2019 and early 2020, the shift in political atmosphere from Kampala was obvious, with casual everyday conversations inevitably leading to discussions about the election. I witnessed very little support for Bobi Wine, which was not altogether unexpected given Museveni’s previous pacification campaigns in the region.Footnote 10 Many Karimojong think of President Museveni as bringing peace and stability to their region, despite the violent, often lethal, force that was used during the ‘peace process’. Many youth and elders agreed that Bobi Wine was too young and inexperienced to govern the country, with elders especially concerned that he had never fought in a war. Workers from places such as Arua and Lira likewise reported their respective regions’ reluctance to embrace Wine. Unsurprisingly, drivers from Northern Uganda did not speak in laudatory terms about the current regime after migrating to Kampala, but they still hesitated in giving enthusiastic support to Wine because they questioned his ability to govern with a strong hand. The motorbikes of such men were often decorated with images of leaders such as Muammar Gaddafi, and, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin. Pictures of Osama bin Laden were also not uncommon, because he, like Gaddafi and Putin, was perceived as a strongman in defiance of ‘the West’. However, the most commonly displayed leader of the past was Idi Amin.

Those familiar with the violence of Idi Amin’s rule are likely to find the public displays of support for him disturbing, yet such displays are critical for deciphering Uganda’s politics of ethnicity and belonging. WhatsApp content has become a critical medium through which people socialize and politicize,Footnote 11 and clips of Amin’s speeches emphasizing the importance of keeping Uganda’s economy for Ugandans circulated widely among drivers and other working-class people. A particularly popular clip contained parts of an interview between Idi Amin and a British journalist, showing the dictator calmly discussing Enoch Powell’s notoriously racist ‘Rivers of blood’ speech to the Conservative Party in Birmingham in the wake of the UK’s Race Relations Act of 1968, in which he argued that the UK’s immigration policies were a threat to the ‘indigenous’ English population, and that immigration must be controlled. The journalist, clearly in disbelief that an African leader could support a British man in favour of expelling African migrants from his country, presses Amin: ‘I know that you’re interested in, and indeed actually go along with, much of what Mr Enoch Powell has been saying recently.’ Amin responds:

Mr Powell Enoch is full supported [sic] by me of what he has said. He’s not discriminating against any races, but he wanted indigenous Londoners, their children, to have a bright future. He does not want England to be colonized by Africa, by Asia. London for Londoners, Scotland for Scottish, Wales for Welsh, Uganda for Ugandans, Rhodesia for Zimbabwean people – not for the white minority regime, and South Africa and Southwest Africa for the black majority. But London can have any technical assistant, anybody they wanted to employ in London. But they are not to dominate the people of England.Footnote 12

The striking part of this interview – and indeed of all of the clips circulating on Ugandan social media around the 2021 election – is how rational Amin’s propositions could appear. The dangers of his brand of nativism seem lost, as he often simply appears to be pushing against ‘minority rule’, such as in apartheid South Africa or pre-independence Zimbabwe.

Lacking a strong hand was not the only point of contention for non-Ganda boda drivers who were hesitant to support Bobi Wine. Being a Muganda was viewed as a hindrance for Wine, as many felt that he would act on behalf of the kabaka and ignore the needs of people from Uganda’s non-Central regions. Particularly striking in videos that were circulating, like the one described above, is the implication that a prosperous Uganda could be realized only through racial or ethnic purging. Would Wine actually be able to govern the country himself, or would he forever be taking orders from the kabaka? If Baganda could not be trusted to care about the country beyond the kingdom, how would that differ from the ‘minority rule’ described in the Amin clip?

One common concern about the country’s leadership that was unanimously shared was the question of who would govern after Museveni’s death if Wine’s campaign proved unsuccessful. With President Museveni then in his late seventies (reaching eighty in 2024), many people throughout the country worried that Museveni’s son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, would ascend the presidency upon his death. One Karimojong man I spoke to, Godwin Lochoru, encapsulated many people’s feelings about that possibility. A driver for one of the many non-governmental organizations in Karamoja, Godwin is a man of few words, preferring to listen to conversations around him and chuckling softly when he finds something funny or amusing. I accompanied him on one of his road trips to conduct surveys and fieldwork when our conversation turned to politics and the possibility of Muhoozi taking control of the country. He turned to look me in the eye and said: ‘I will get a gun and go to Kampala before letting that man take power.’

Despite the North providing a large swathe of support for Museveni, the thought of his son governing was enough to worry even the most mild-mannered of people. After leaving Kampala in March 2020 (at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic), I continued to communicate with my interlocutors through WhatsApp. By spring 2022, Muhoozi’s camp had begun to realize the power of boda drivers that Wine’s campaign had harnessed and coupled with drivers’ admiration for strongmen. By May 2022, boda drivers all over Kampala could be seen with Muhoozi’s face on their windshields and ‘TEAM MUHOOZI: BODA BODA INITIATIVE UGANDA’ written underneath. For other boda drivers in Kampala, Team Muhoozi’s drivers were said to not really be motorbike drivers, but rather men paid to fight with actual drivers who ‘do not agree with him’. Without publicly talking about his plans to succeed his father or run for president, Muhoozi has begun to assert himself as a strongman. Images of Muhoozi dressed in military apparel, donning the red beret previously associated with Bobi Wine, now often appear on motorbikes. Separating himself in dress from his father, Muhoozi seems to be embracing militaristic aesthetics as visual proof of his might. The bush hat that is central to Museveni’s image may have worked to remind his early supporters of the Bush War that took him to power several decades ago, but for younger generations far removed from that conflict, a modern military-chic look inspires more fear than broad-rimmed safari hats.Footnote 13

Boda cooperatives, coopted and coerced?

Boda drivers who were sceptical of Muhoozi’s fleet explained that drivers who are registered with boda cooperatives are often indebted to their local office. As driver Simon Tugume put it: once you register with an office, ‘you will be used by them’. Cooperatives own boda stages, and when you become a member of a particular stage, you have access to the group’s resources. Within boda cooperatives, loans are given for obtaining or maintaining motorbikes, and every driver with whom I spoke said that they would not have been able to become a driver without the assistance of their association. Without savings or kinship networks, they have an ‘experience of transience and juxtaposition, displacement and precariousness’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2004: 391) that their cooperatives help alleviate.

Boda cooperatives are not unique but are one of many types of savings and credit cooperative organization (SACCO). SACCOs are voluntary associations where members regularly pool their savings and can subsequently obtain loans for different purposes.Footnote 14 SACCOs can be formally registered with the government,Footnote 15 which has led to a proliferation of rumours and conspiracies. It is rumoured that President Museveni deposits money directly into particular SACCOs when he needs to mobilize people for political purposes. Thus, drivers donning black T-shirts with the words ‘Silent Majority’ written in silver ink to signal their quiet support for the ruling regime, or showing explicit signs of support such as NRM yellow berets, were often dismissed as simply coerced into doing so by accepting Museveni’s money. While the corruption of the ruling regime must be considered in any political analysis of Uganda, Banyankole insisted that showing any support for Museveni was dangerous. They explained that people were publicly beaten on election days if they admitted to voting for Museveni, and that groups of People Power supporters patrolled the streets to smash the knuckles of anyone wearing NRM gear. I never met a Munyankole who was the victim of such a crime, but these stories were influential in maintaining the seemingly insurmountable divides that existed between Museveni and Wine. The actual threat of violence must therefore also be considered when analysing the proliferation of outward shows of support for the NRM.

The political leaders that boda drivers chose to display acted as symbols, marking people’s different visions for Uganda. But beyond that, these images also served as a different form of interruption: Amin’s images horrified tourists and expatriates; NRM gear made people question a unified opposition to Museveni; Muhoozi’s band of boda drivers made people re-evaluate his potential for authoritative rule; Bobi Wine’s pictures were a visual protest against the current regime. These bold displays of men who had – or have the potential to have – such profound effects on Uganda allow us to see how the future of the country is at the forefront of people’s concerns. Critically, seeing all of the possibilities that drivers presented forces us to reckon with unexpected futures that have previously remained hidden in our current Rancièrian distribution of the sensible.

Despite the diverse political leanings of different boda drivers, which included support for Museveni and the ruling regime as well as for Bobi Wine and the opposition, or which featured other national or regional ‘strongmen’ (such as Gaddafi, Bin Laden and Amin, as discussed above), the circulation of videos such as the one described at the start of this article made all of them targets in the days of October 2019. The ‘informality’ of the boda boda economy did nothing to free them from those dangers. The police set up roadblocks at major intersections, people’s motorbikes were confiscated and thrown onto police trucks, and drivers were arrested for minor infractions. Without stringent regulations, or normally any enforcement, many drivers lack formal credentials, licences and insurance, and common transgressions include drivers refusing to wear helmets or to abide by regulations limiting passengers to one. During October 2019, and running up to the election, however, drivers were regularly stopped and asked to show their licence and insurance information. Unless a person had enough cash to negotiate a deal with an interrogating officer, lacking either was enough for the police to detain drivers. Mass roundups of drivers took place under the guise of public safety,Footnote 16 but drivers and their passengers alike knew they were paying the price for the regime’s disdain for and fear of Wine’s popularity. For the police, it was often also an opportunity to extract bribes from drivers.Footnote 17 But, even during boda roundups, drivers and passengers quickly learned which intersections the police were targeting and then used longer, more discreet routes to avoid arrest and evade fines. Interrupting absolute authority, drivers found creative ways to pick up passengers, get them to their desired destinations, and avoid police attention.

It is tempting to view aesthetic interruptions merely as examples of the state ‘reaffirming that this power is incontestable – precisely the better to play with it and modify it whenever possible’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe and Mbembe2001: 129, emphasis in the original), or as illustrating ‘how the practices of those who command and those who are assumed to obey are so entangled as to render both powerless’ (ibid.: 133). Indeed, the severity of state punishments imposed to maintain Museveni’s control resembles Mbembe’s description of commandement described in ‘The aesthetics of vulgarity’ (ibid.), and critiques of ‘power’ reify, often inadvertently, the presence of the powerful. Yet we should also take seriously the efficacy of the symbols themselves, as utilized and displayed by boda drivers. Symbols consciously displayed cannot necessarily be reduced to an aesthetic political ‘culture’, or a misunderstanding of history, but they can be powerful appeals to the politics of the past; symbols can act in the world themselves (Lévi-Strauss Reference Lévi-Strauss1963). The proliferation of Idi Amin icons and images among Kampala’s boda drivers during the run-up to the 2021 elections speaks most directly to this, as he is not a contemporary opponent to Museveni, and was therefore not an actual challenge to his power. The political choice to carry Idi Amin images among some boda drivers was agentive in its own right, indexing particular visions of Uganda’s past and its possible futures.

Aesthetic refusal: the story of Simon

Throughout this article, focusing on the aesthetic choices of boda drivers was meant to highlight the ways in which they were actively asserting their political views. Ethnic diversity, and the ways in which history politicizes ethnicity, encourages the diversity of aesthetic interruptions elaborated above. However, a deeper understanding of the potency of these symbols can be gleaned from a driver who refused such political displays. Simon Tugume is one of countless young men who migrated to Kampala in search of wage labour. Originally from a small village in Ankole, Simon identifies as a Munyankole, or Muiru more specifically, and he lives with his wife Mary and their young daughter in Kampala. He does not particularly like the city; working long hours every day as a driver while his wife sells produce in a makeshift stand outside their rented room, they are in a precarious economic situation without extended family to help with childcare. They are often scrambling to gather enough cash to send their three-year-old child to preschool, which Simon claims is more expensive than it would be in his home village. Like many other migrants to the city, Simon and Mary are without the extended kin network that often exists in more rural settings.

Simon was one of my closest interlocutors throughout fieldwork, and our close relationship was made possible by him being my boda driver. Travelling throughout Kampala during rush hour was nearly impossible by car, and his safe – or safer than average – habits made him my go-to boda driver, and we spent many hours together. On one of my first rides with him, we passed a group of Wine supporters blasting their horns and wearing red berets, and Simon sucked his teeth and shook his head as they rode by. When I asked him about this negative reaction, he repeated a concern that I heard from many non-Ganda people in Kampala: he did not trust a Muganda to be president. Simon was convinced that a Muganda would not act on behalf of all Ugandans, but would instead act on behalf of the kabaka. Upon hearing his concerns, I naively assumed that his ethnic identity and misgivings about Bobi Wine would translate into support for the ruling regime. However, we had not known each other for very long, so some months went by between this seemingly mundane happening and the beginning of our long discussions concerning Museveni and the NRM.

As we grew more comfortable with one another, events in the city made politics impossible to ignore. We had to drive by the Makerere campus every day during protests that erupted in October 2019 over a tuition fee hike, as it was en route to an orphanage that served as one of my main field sites, and I could not comprehend people’s calm in the face of such obvious violent state repression. Simon’s reactions to the quotidian forms of state violence against protests were largely representative of most working-class people; he explained, as a casual fact, that the police regularly ‘use teargas like water’. The frequent use of such tactics made it an ordinary, uneventful part of life, violence thus forcing its way into the folds of the everyday akin to contexts of war within and beyond the African context (cf. Lubkemann Reference Lubkemann2008; Thiranagama Reference Thiranagama2011). Yet the even tone in his voice made me wonder if Simon was sympathetic to the regime beyond mere acceptance of it, so, having known him for several months by the time of the October protests, I asked him directly if he was an NRM supporter.

His response revealed neither acceptance nor resistance, interrupting the idea that people are restricted to binaries. Instead of speaking about the 2021 elections, he referred to the previous election cycle. ‘We go to bed thinking Besigye wins, we wake up to Museveni as president again!’ he explained. He said that he went to bed on the night of the 2016 election so happy, expecting celebrations and long-awaited change, only to wake up to Museveni staying in power, the same man who was president when Simon was born. His vote for the opposition party indicates his dissatisfaction with President Museveni, but Simon simply did not think there was a way to ever vote him out of office, a view shared by many. As Moses Khisa explains, when ‘an election … is organized and superintended by Museveni himself … [the] electoral commission can never, never declare any other person president-elect other than Museveni’ (as quoted in Broadway Reference Broadway2020). Although Simon was not a Wine supporter, he was convinced that voting could not possibly lead to anything other than another Museveni victory and was not going to vote in the upcoming election.

It cannot be assumed, then, that drivers who refused public displays of opposition to Museveni are content under his rule. Acceptance of the seeming impossibility of voting him out is not the same as acceptance of his regime. In this way, Simon’s own aesthetic refusal was revealing in its own right. As Ssentongo and Alava have argued, ‘some opted out of voting due to the belief that neither Museveni nor Bobi Wine, the key contenders, offered what Uganda needed’ (Ssentongo and Alava Reference Ssentongo and Alava2023: 317). While choosing not to vote may appear to be a cynical choice and illustrative of the lack of agency Ugandans feel in their political system, disengagement can be a form of resistance in places such as Kampala. If political action is controlled by the state, and thus even Wine’s campaign becomes folded into the state’s power (cf. Mbembe Reference Mbembe2004), refusal of both candidates allows for alternative futures for the country.

Futures and pasts: a post-Museveni Kampala

Taking seriously the diversity of aesthetic interruptions offered by boda drivers in Kampala forces one to contend with competing visions of the past and the future of the country. Attempting to expand who has ‘the ability to see and the talent to speak’ (Rancière Reference Rancière2018 [2006]: 13) challenges a dichotomous view of politics in Uganda. While the intention of this article is not to reinforce unchanging ideas of ethnicity, Kampala’s long history of ethnic diversity is one of the contributing factors to diverging political ideals. Bobi Wine’s support was certainly not limited to Baganda within Buganda, but his conscious efforts to reach fans and supporters across ethnic boundaries does point to ethnicity’s continued salience. For young Baganda drivers, supporting a co-ethnic who grew up in the city was easier than for Banyankole drivers who interpreted phrases such as ‘We need ours’ as calls for ethnic violence and further division. For some young men from Northern Uganda, a prosperous future could only be had by returning to the exclusionary and often violent authoritarian styles of the past. Aesthetic choices indicate politics and, in turn, often index ethnicity.

President Museveni will not live forever, and there is much speculation on the ground as to what may happen when he dies. Although Banyankole report being targets of resentment due to their shared ethnicity with the president, many members of the Banyankole working class in Kampala are as disillusioned with his long grip on power as people of other ethnic groups. The diversity of aesthetic interruptions among boda drivers suggests that there is far from a simple dichotomous view regarding what constitutes a prosperous future, and we cannot just assume that Idi Amin stickers ‘are ripped out of their contexts’ (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2004: 404) for the sake of a fantastical memorialization; rather, we must take seriously what Amin represents for the underclass donning his image. The boda drivers displaying Amin’s image are young and did not live through the brutality of his regime, yet the proliferation of WhatsApp content made his speeches and interviews widely available for consumption. Muhammed Aate, an askari Footnote 18 from Idi Amin’s home region of Arua, plainly said to me, ‘All you foreigners should go!’ Echoing a similar logic as found in Amin’s interview cited above, Muhammed believed that foreign-born people were profiting from Uganda’s riches at its citizens’ expense. Because the effects of his policies were not experienced by Muhammed or the boda drivers in Kampala, Amin’s violent nationalism took on new meanings in the present.

Beyond (dis)satisfaction with present political leaders, then, the aesthetic choices of boda drivers express resentment. They work long hours for little money and struggle to provide for their kin, and in this context Amin’s violent rule of the past is used to make sense of possible futures. As Mike McGovern theorizes, ‘Resentment is not purely backward-looking, as Nietzsche suggests. As part of a more encompassing means of narrativizing and making sense of life, it is often linked to other tropes, including betrayal and liberation’ (McGovern Reference McGovern2011: 93). The aesthetic interruptions that feature Amin are expressing resentments among boda drivers that cannot be resolved by President Museveni or by the contemporary political opposition. Ethnicity’s continued potency in Kampala, combined with the realities of economic precarity, has inspired boda drivers born long after Amin’s rule to reimagine the possibilities of xenophobic nationalism. When the present is not providing what is needed, looking backward and moving forward can mistakenly be conflated. Temporal separation has allowed Amin to emerge as something new.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the National Science Foundation and the African Studies Center, the Department of Anthropology, and Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for funding the research for this article, as well as the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for funding the writing stage. Two anonymous reviewers strengthened the article. Many thanks to Dominique Arambula and Kevin Osei Bonsu for attempting the impossible task of improving the quality of images taken on my Ugandan phone. My deepest thanks to Kenda Mutongi for her incisive comments on an early draft, as well as Derek Peterson, Erik Mueggler, Kelly Askew and Adam Ashforth. Quincy Amoah, Zehra Hashmi, Vinicius Furuie and Kaan Kartel provided generative feedback, and my greatest intellectual debt goes to Mike McGovern.

Christine Chalifoux is Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Africana Studies at Franklin & Marshall College.