Impact statement

This research challenges persistent narratives that frame drylands as marginal and unproductive, demonstrating instead that these environments have long supported resilient and sustainable forms of agriculture and pastoralism. By integrating archaeological and ethnographic perspectives, this perspective paper highlights how traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and nonmechanized subsistence strategies constitute vital forms of biocultural heritage, offering models for sustainability rooted in centuries of local adaptation. The impact of this work lies in reframing archaeology as a key discipline for informing present and future land-use strategies in the context of accelerating aridification and global climate change. Through the documentation of long-term socio-ecological adaptation, archaeology provides empirical, deep-time evidence that can guide the design of context-specific, sustainable agroecosystems. The project promotes an interdisciplinary dialogue between archaeology, environmental science and policy, advocating for the incorporation of TEK into agricultural planning and climate resilience frameworks. Ultimately, this research contributes to empowering dryland communities by validating indigenous knowledge systems and demonstrating their relevance to contemporary sustainability challenges. It encourages policymakers and scientists to view drylands not as ecological frontiers to be mitigated, but as landscapes of opportunity where the lessons of the past can inform adaptive strategies for a more sustainable future.

Introduction

Drylands are home to more than 35% of the world’s population and produce 44% of the crops globally according to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD, 2017). Still, the idea persists that arid environments are not fully suitable for food production, especially where annual rainfall is lower than 450 mm/year. As a result, mainstream studies (e.g., Portmann et al., Reference Portmann, Siebert and Döll2010; Xie et al., Reference Xie, You, Wielgosz and Ringler2014; Rockström and Falkenmark, Reference Rockström and Falkenmark2015; Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Chiarelli, Rulli, Dell’Angelo and D’Odorico2020; Potapov et al., Reference Potapov, Turubanova, Hansen, Tyukavina, Zalles, Khan, Song, Pickens, Shen and Cortez2022) have often considered drylands as marginal areas where cultivation is unfeasible and mobile pastoralism is the only possible economic activity (but see Biagetti et al., Reference Biagetti, Ruiz-Giralt, Madella, Magzoub, Meresa, Gebreselassie, Veesar, Abro, Chandio and Lancelotti2022 for a recent discussion). This significantly contrasts with the ethnographic and archaeological literature, which has provided a significant number of examples showing that food production is possible, including rainfed agriculture. This is the case even in arid and hyperarid regions, where indigenous communities have developed resilient, sustainable agropastoral systems as a result of long-term processes of socio-ecological adaptation (see Lancelotti and Biagetti, Reference Lancelotti and Biagetti2021; Ruiz-Giralt et al., Reference Ruiz-Giralt, Biagetti, Madella and Lancelotti2023a and references therein). In fact, recent studies on biodiversity and productivity in drylands have demonstrated that it is not a lack of potential but rather flawed observational methodologies and data gaps that have contributed to the construction of a misleading paradigm around drylands (Wang and Collins, Reference Wang and Collins2024).

Recent perspectives on drylands are gradually shifting, although this is not yet fully reflected at the global scale. Long-term, evidence-based accounts can contribute to this transition by building a positive reinforcement of resilient and adapted practices. An archaeological (long-term) perspective is essential alongside historical data, as it captures temporal lags and internal variability of slow variables across distinct and changed environmental states, offering crucial insights beyond the “instrumental era” (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Reide, Gouramanis, Keenan, Stoffel, Hu and Ionita2022, 8). Archaeological and ethnoarchaeological research can play a key role in evidencing that these landscapes have long supported complex and resilient subsistence strategies (e.g., Lancelotti et al., Reference Lancelotti, Biagetti, Zerboni, Usai and Madella2019; Barker, Reference Barker2022; Biagetti et al., Reference Biagetti, Ruiz-Giralt, Madella, Magzoub, Meresa, Gebreselassie, Veesar, Abro, Chandio and Lancelotti2022; Rosen, Reference Rosen, Izdebski, Haldon and Filipkowski2022; D’Agostini et al., Reference D’Agostini, Ruiz-Pérez, Madella, Vadez, Kholova and Lancelotti2023; Rieger, Reference Rieger, Bentz and Heinzelmann2023; Ruiz-Giralt et al., Reference Ruiz-Giralt, Nixon-Darcus, D’Andrea, Meresa, Biagetti and Lancelotti2023b). Archaeobotany is also essential to deepen our comprehension of the development of plant species adapted to these environments, often neglected (referred to as “orphan crops,” cf. Mabhaudhi et al., Reference Mabhaudhi, Chimonyo, Hlahla, Massawe, Mayes, Nhamo and Modi2019). Such an understanding has the potential to foster the construction of new theoretical models that mitigate existing biases about human–environment interactions in dryland areas.

Toward a deep history of dryland livelihood systems

While sources such as written documents, oral history and/or artistic representations can help us understand the more recent historical past, the study of livelihood systems from a long-term perspective relies primarily on archaeological evidence. A wide range of archaeological approaches can contribute to this goal, including analyses of material culture, architectural remains and landscape features. In this perspective article, we focus on those archaeological subfields within our expertise (i.e., archaeobotany, zooarchaeology and geochemistry) that jointly enable the reconstruction of past lifeways in arid environments. We consider it crucial to combine these techniques with experimental and ethnoarchaeological data to generate a more robust and comprehensive understanding of past-to-present human adaptation to drylands and its evolution over time.

Beyond the grain: Multiproxy archaeobotany reshapes our understanding of possible dryland agricultural systems

A growing number of archaeobotanical case studies from dryland regions have begun to shift long-standing assumptions about ancient agricultural systems. Notable among the outcomes is the research on macro- and micro-remains from both wild and domesticated millets that has revealed their central role in sustaining past economies in drylands (e.g., Madella et al., Reference Madella, García-Granero, Out, Ryan and Usai2014; Beldad, Reference Beldados2015; Lucarini et al., Reference Lucarini, Radini, Barton and Barker2016; Out et al., Reference Out, Ryan, García-Granero, Barastegui, Maritan, Madella and Usai2016; Winchell et al., Reference Winchell, Stevens, Murphy, Champion and Fuller2017; Bao et al., Reference Bao, Zhou, Liu, Hu, Zhao, Atahan, Dodson and Li2018; Beldados et al., Reference Beldados, Manzo, Murphy, Stevens, Fuller, Mercuri, D’Andrea, Fornaciari and Höhn2018; Beldados, Reference Beldados2019; Lucarini and Radini, Reference Lucarini and Radini2020; Le Moyne et al., Reference Le Moyne, Fuller and Crowther2023; Ruiz-Giralt et al., Reference Ruiz-Giralt, Nixon-Darcus, D’Andrea, Meresa, Biagetti and Lancelotti2023b, see Table 1 for further references). These findings have encouraged a revaluation of traditional models of agricultural development, which had often privileged large-scale, C3 cereal-based economies and sedentary lifeways (see Fuller and Lucas, Reference Fuller and Lucas2025 for a recent example). Case studies that integrate phytolith and starch grain analyses have further contributed to this reassessment by identifying the use and consumption (foodways) of alternative crops, including plant storage organs that are often not considered (e.g., Piperno et al., Reference Piperno, Ranere, Holst and Hansell2000, Reference Piperno, Ranere, Holst, Iriarte and Dickau2009; García-Granero et al., Reference García-Granero, Lancelotti, Madella and Ajithprasad2016; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Cheng, Li, Yao, Li, Luo, Yuan, Zhang and Zhang2016; Louderback and Pavlik, Reference Louderback and Pavlik2017; Veth et al., Reference Veth, Myers, Heaney and Ouzman2018; Lucarini and Radini, Reference Lucarini and Radini2020; Santiago-Marrero et al., Reference Santiago-Marrero, Tsoraki, Lancelotti and Madella2021; Ruiz-Giralt et al., Reference Ruiz-Giralt, Nixon-Darcus, D’Andrea, Meresa, Biagetti and Lancelotti2023b; Castillo et al., Reference Castillo, Beldados, Ryan, Bond, Vrydaghs, Lulekal, Borrell, Hunt and Fuller2025). In parallel, recent models based on phytolith abundance, such as those proposed by D’Agostini et al. (Reference D’Agostini, Ruiz-Pérez, Madella, Vadez, Kholova and Lancelotti2023), point to forms of land management that challenge the assumed reliance on intensive agriculture and are compatible with nomadism. Alongside, innovative approaches using stable carbon δ13C (13C/12C), nitrogen δ15N (15N/14N) and silicon δ30Si (30Si/28Si) isotopes on both macro- (e.g., C4 grains) and micro-remains (phytoliths) are emerging to investigate the role of water and land management in dryland agriculture. These methods allow for indirect assessment of subsistence strategies and levels of agricultural investment, which in turn may reflect more sedentary or mobile lifeways. Although still in development for millet species, early applications show significant promise. Notable examples include isotopic studies on millet grains (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Lalk, Marshall and Liu2018; Lightfoot et al., Reference Lightfoot, Jones, Joglekar, Tames-Demauras, Smith, Muschinski, Shinde, Singh, Jones, O’Connell and Petrie2020; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Bi, Wu, Belfield, Harberd, Christensen, Charles and Bogaard2022; Varalli et al., Reference Varalli, D’Agostini, Madella, Fiorentino and Lancelotti2023, Reference Varalli, Beldados, d’Agostini, Mvimi, D’Andrea and Lancelotti2024; see Table 1 for further references) and on phytoliths (D’Agostini et al., Reference D’Agostini, Ruiz Pérez, Madella, Vadez and Lancelotti2025). By incorporating a broader spectrum of crops and cultivation strategies, these archaeobotanical studies have enabled a more nuanced interpretation of past land use, mobility and resilience in dryland environments – one that recognizes the diversity of human–environment interactions and the importance of marginalized crops like millets in sustaining communities under variable and often challenging ecological conditions.

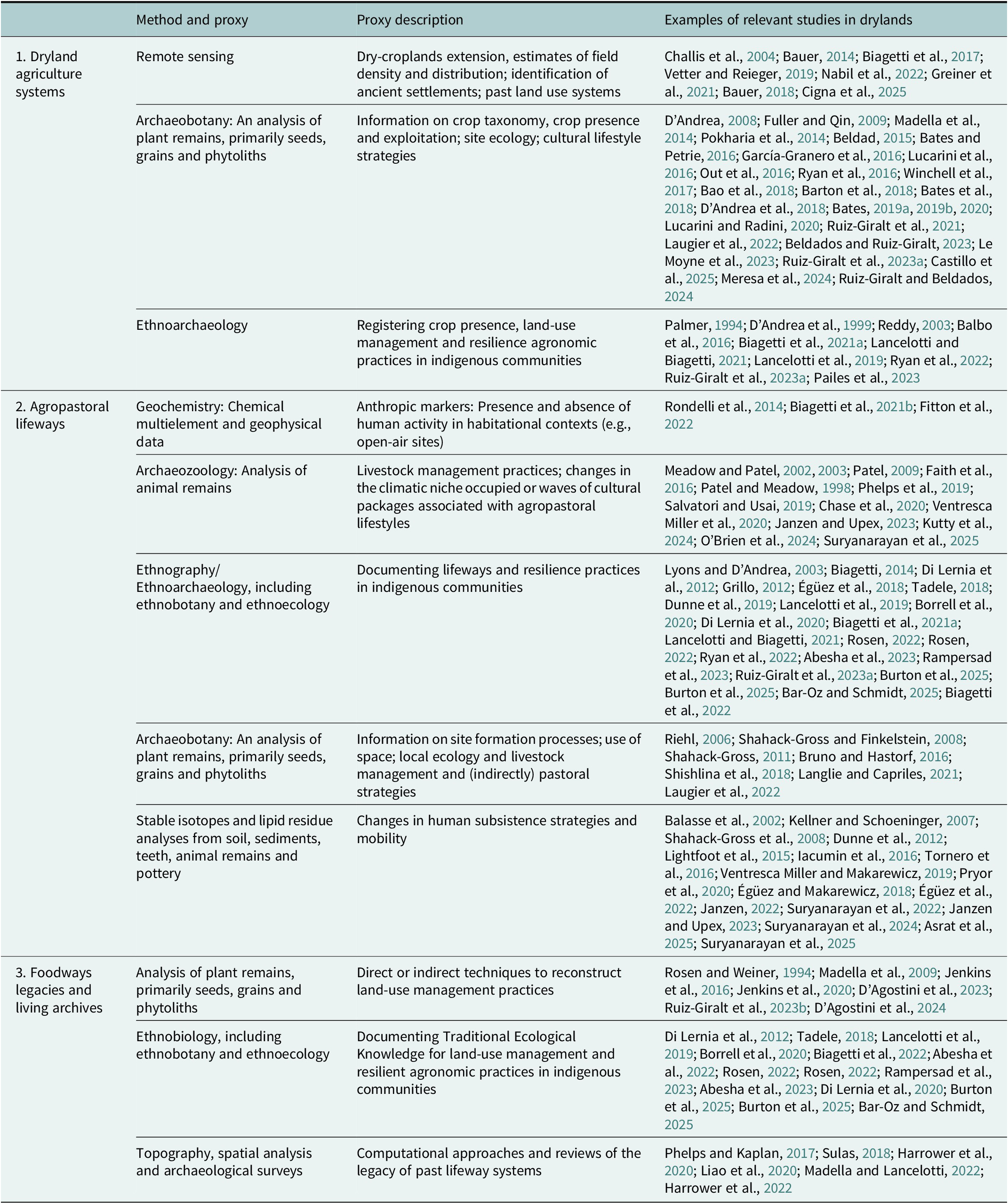

Table 1. Selected publications on drylands archaeology, encompassing studies in remote sensing, archaeobotany, ethnoarchaeology, geochemistry (with a focus on anthropic markers), archaeozoology and ethnobiology. The purpose of this table is to summarize relevant literature – partly cited in the main text and partly included for broader reference – organized by topic as the sections of the main text (drylands agricultural systems, agropastoral lifeways and resilient foodways, legacies and living archives) and then by proxy type. This structure mirrors the analytical approach adopted throughout the manuscript, which highlights the value of archaeology and its long-term perspective for understanding the evolution of land-use systems in drylands. The studies cited in this table collectively demonstrate that the long-standing paradigm portraying drylands as devoid of biodiversity and agricultural potential is inaccurate. Archaeological evidence, even from the deep past, consistently reveals traces of complex, adaptive and byresilient human–environment interactions that challenge this misconception.

Note: Only works whose area of investigation or excavation was located within properly defined dryland regions were included. The selection of studies presented here also reflects the specific areas of expertise of the contributing authors.

Crucially, it is the integration of macro-remains (i.e., charred seeds and wood charcoal) with micro-remains (i.e., phytoliths and starch grains) that allows archaeobotanists to reveal a broader picture of plant–human interactions on ancient landscapes. In fact, the macro-botanical record is often skewed toward certain plant taxa due to pre- and post-depositional processes (see Boardman and Jones, Reference Boardman and Jones1990; Hastorf and Wright, Reference Hastorf and Wright1998; Valamoti and Charles, Reference Valamoti and Charles2005; Margaritis and Jones, Reference Margaritis and Jones2006; Madella et al., Reference Madella, Lancelotti and García-Granero2016; Lancelotti, Reference Lancelotti2018; Beldados and Ruiz-Giralt, Reference Beldados and Ruiz-Giralt2023; Stroud et al., Reference Stroud, Charles, Bogaard and Hamerow2023; Varalli et al., Reference Varalli, D’Agostini, Madella, Fiorentino and Lancelotti2023; Jiménez-Arteaga et al., Reference Jiménez-Arteaga, Parque, Lancelotti, Moderato, Veesar, Tasleem Abro, Amin Chandio and Madella2025). Millets, in particular, are commonly underrepresented as a result of combined biases from recovery methods and frequent misidentifications. This has often led to the assumption that millets were not widely present in dryland contexts and, consequently, that C4 agriculture in nonintensive forms, unsupported by irrigation, was absent. For this reason, it is valuable to integrate macro-remain data with phytolith analysis, as the latter may reveal a more abundant presence of C4 plants than previously assumed. However, taxonomic representativeness of micro-remains alone can also create biases that distort our understanding of agricultural practices. For example, the presence of C3 plants may not be easily recognized in phytolith assemblages due to redundancy and multiplicity issues (see Neumann et al., Reference Neumann, Strömberg, Ball, Albert, Vrydaghs and Cummings2019). Consequently, it is important to highlight that macro- and micro-botanical remains are highly complementary due to both the nature of the arid contexts – which affects the taphonomy and recovery of archaeobotanical remains – and the morpho-physiological characteristics of the plant material itself. Recent studies have shown that focusing on only one of them can lead to significantly different results (e.g., Out et al., Reference Out, Ryan, García-Granero, Barastegui, Maritan, Madella and Usai2016; Laugier et al., Reference Laugier, Casana and Cabanes2022; D’Andrea et al., Reference D’Andrea, Welton, Manzo, Woldekiros, Brandt, Beldados, Peterson, Nixon-Darcus, Gaudiello, Taddesse, Wood, Batiuk, Meresa, Ruiz-Giralt, Lancelotti, Taffere and Johnson2023; Meresa et al., Reference Meresa, Ruiz-Giralt, Beldados, Lancelotti and D’Andrea2024).

Tracking the elusive: Tracing the evolution of agropastoral lifeways

Although pastoralist lifestyles have been widespread across arid regions for millennia, the study of the evolutionary trajectory of these practices remains a challenging topic, largely due to their inherently ephemeral nature and the lack of diagnostic indicators (see Biagetti and Howe, Reference Biagetti and Howe2017). In fact, the most commonly studied sites associated with pastoralist activities have been related to funerary practices (Sierksma, Reference Sierksma1963; Di Lernia and Manzi, Reference Di Lernia and Manzi1998; Honeychurch, Reference Honeychurch2014; Sawchuk et al., Reference Sawchuk, Goldstein, Grillo and Hildebrand2018; Morandi Bonacossi, Reference Bonacossi, Lawrence, Altaweel and Philip2020; Pleuger-Dreibrodt et al., Reference Pleuger-Dreibrodt, Honeychurch and Makarewicz2025), whereas sites related to everyday activities, including mobile farming, are scarce (see Reference BiagettiBiagetti forthcoming in this issue for a recent review). As a result, the last decades of pastoralism archaeology have concentrated on redefining ancient pastoral landscapes and foodways, integrating new methodologies (see Honeychurch and Makarewicz, Reference Honeychurch and Makarewicz2016; Curta, Reference Curta2025 for more detailed reviews). Among others, these include spatial analysis (e.g., Salzman, Reference Salzman2002; Biagetti et al., Reference Biagetti, Merlo, Adam, Lobo, Conesa, Knight, Bekrani, Crema, Alcaina-Mateos and Madella2017; Hildebrand et al., Reference Hildebrand, Grillo, Sawchuk, Pfeiffer, Conyers, Goldstein, Hill, Janzen, Klehm, Helper, Kiura, Ndiema, Ngugi, Shea and Wang2018; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Van de Voorde, Chen, Bourgeois, Gheyle, Goossens, Yang and Xu2021), as well as site-level investigations targeting specific material proxies – that is, archaeological dung (Shahack-Gross et al., Reference Shahack-Gross, Simons and Ambrose2008; Shahack-Gross, Reference Shahack-Gross2011; Égüez and Makarewicz, Reference Égüez and Makarewicz2018; Égüez et al., Reference Égüez, Dal Corso, Wieckowska-Lüth, Delpino, Tarantino and Biagetti2020), organic residues from archaeological materials (Dunne et al., Reference Dunne, Evershed, Salque, Cramp, Bruni, Ryan, Biagetti and di Lernia2012; Chakraborty et al., Reference Chakraborty, Slater, Miller, Shirvalkar and Rawat2020; Suryanarayan et al., Reference Suryanarayan, Cubas, Craig, Heron, Shinde, Singh, O’Connell and Petrie2021; Chasan et al., Reference Chasan, Spiteri and Rosenberg2022; Mileto et al., Reference Mileto, Cavulli, Carrer, Ferronato and Pecci2023; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, López-Matayoshi, Remolins, Gibaja, Subirà, Fondevila, Palomo-Díez, López-Parra, Labajo-González, Lareu, Perea-Pérez and Arroyo-Pardo2025) or geochemical analysis (Biagetti et al., Reference Biagetti, Alcaina-Mateos, Ruiz-Giralt, Lancelotti, Groenewald, Ibañez-Insa, Gur-Arie, Morton and Merlo2021b).

Within this broader methodological and analytical expansion, the application of classical zooarchaeological methods that explicitly incorporate taphonomic evidence has proven particularly valuable, offering insights into how human groups exploited and managed the full spectrum of animal resources available in arid environments (e.g., Gifford-Gonzalez et al., Reference Gifford-Gonzalez, Isaac and Nelson1980; Gifford-Gonzalez, Reference Gifford-Gonzalez1998; Chase, Reference Chase2010; Channarayapatna, Reference Channarayapatna2018; Goyal, Reference Goyal2021; Katongo et al., Reference Katongo, Fleisher and Prendergast2025; see Table 1 for further references). In parallel, faunal studies in drylands have increasingly adopted biomolecular techniques (e.g., paleo-proteomics and ancient DNA) to refine chronological frameworks and, in some cases, to redefine our understanding of when and how domestic taxa became integrated into agropastoral systems (e.g., Grillo et al., Reference Grillo, Dunne, Marshall, Prendergast, Casanova, Gidna, Janzen, Karega-Munene, Keute, Mabulla, Robertshaw, Gillard, Walton-Doyle, Whelton, Ryan and Evershed2020; Coutu et al., Reference Coutu, Taurozzi, Mackie, Jensen, Collins and Sealy2021; Culley et al., Reference Culley, Janzen, Brown, Prendergast, Shipton, Ndiema, Petraglia, Boivin and Crowther2021; Janzen et al., Reference Janzen, Richter, Mwebi, Brown, Onduso, Gatwiri, Ndiema, Katongo, Goldstein, Douka and Boivin2021).

Complementing these analytical frameworks, biogeochemical approaches have been tested to determine both the diet and mobility of the pastoral and agropastoral communities, again providing more detailed insights on subsistence strategies (e.g., Prendergast et al., Reference Prendergast, Lipson, Sawchuk, Olalde, Ogola, Rohland, Sirak, Adamski, Bernardos, Broomandkhoshbacht, Callan, Culleton, Eccles, Harper, Lawson, Mah, Oppenheimer, Stewardson, Zalzala and Reich2019). Dietary information can be inferred through stable carbon isotope values δ13C and stable nitrogen values δ15N obtained from enamel, dentine and bone tissue (e.g., Vaiglova et al., Reference Vaiglova, Lazar, Stroud, Loftus and Makarewicz2023; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Pederzani, Britton and Wexler2025). Indirectly, this type of analysis has recently provided evidence for the possible presence and consumption of millet species or other C4 taxa included in the suite of exploited plants, indicating their potential contribution to both human and animal diets, even in contexts where C3 species were considered dominant in the archaeobotanical record (e.g., Ventresca Miller and Makarewicz, Reference Ventresca Miller and Makarewicz2019; Chase et al., Reference Chase, Meiggs and Ajithprasad2020; Lightfoot et al., Reference Lightfoot, Jones, Joglekar, Tames-Demauras, Smith, Muschinski, Shinde, Singh, Jones, O’Connell and Petrie2020; see Table 1 for further references). What is particularly interesting about this approach is that it complements archaeobotanical methods, allowing us to explore interpretative hypotheses related not only to subsistence choices but also to patterns of mobility, shedding light on how communities might have managed their resources and adapted to arid environments.

Recently, migratory practices and settlement dynamics of both humans and animals have been substantially refined and applied to dryland communities’ studies. Strontium (87Sr/86Sr), oxygen (δ 18O–16O/18O), sulfur (δ 34S–34S/35S) and hydrogen (δ 2H–2H/1H) isotopes in both archaeobiological materials (teeth, bones, plants and among others) and environmental samples (soil and water) have been applied to provide insights into mobility across dryland landscapes in regions such as Ethiopia (Pryor et al., Reference Pryor, Insoll and Evis2020; Asrat et al., Reference Asrat, Lucchini, Tafuri, Aureli, Gallinaro, Zerboni, Fusco and Spinapolice2025), Kenya (O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Podkovyroff, Fernandez, Tryon, Cerling, Ashioya and Faith2024), South Africa (Balasse et al., Reference Balasse, Ambrose, Smith and Price2002), Tanzania (Tryon and Faith, Reference Tryon and Faith2016), Arabian Peninsula (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Dabrowski, Dapoigny, Gauthier, Douville, Tengberg, Kerfant, Mouton, Desormeau, Noûs, Zazzo and Bouchaud2021) and North West India/South East Pakistan (Chase et al., Reference Chase, Meiggs, Ajithprasad and Slater2018; Parque, Reference Parque2025) and China (Wang and Tang, Reference Wang and Tang2020). Additionally, major improvements have been put in place for the creation of a quantitative spatial isotopic variability, known as ‘isoscapes’ (Bataille et al., Reference Bataille, Crowley, Wooller and Bowen2020), used alongside probabilistic models for geographic assignment of the materials across broad areas (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Vander Zanden, Wunder and Bowen2020), for identifying animal trade networks (Chase et al., Reference Chase, Meiggs, Ajithprasad and Slater2018), and even to recognize intercontinental mobility involving humans (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Bocksberger, Arandjelovic, Agbor, Angedakin, Aubert, Ayimisin, Bailey, Barubiyo, Bessone, Bobe, Bonnet, Boucher, Brazzola, Brewer, Lee, Carvalho, Chancellor, Cipoletta and Oelze2024). The ‘isoscapes’ have made it possible not only to formulate hypotheses on circulation patterns at a more limited spatial resolution but also to support interpretations of hybrid seminomadic lifeways, as well as to substantiate hypotheses of trade across drylands, reinstating these activities as having significant frequency and importance.

Resilient foodways legacies and living archives: Recovering biocultural heritage through ethnoecology and ethnoarchaeology

A key topic in the study of past-to-present resilient dryland economies is the pivotal role of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), defined as a holistic, cumulative body of knowledge, practice and belief. TEK is the result of long-term adaptive processes transmitted across generations, concerning the intricate relationships between living beings and their environment (Kimmerer, Reference Kimmerer2002, Swiderska et al., Reference Swiderska, Argumedo, Wekesa, Ndalilo, Song, Rastogi and Ryan2022 for recent accounts). However, the value of TEK has been increasingly acknowledged over the last three decades (e.g., Inglis, Reference Inglis1993 and references therein, Agrawal, Reference Agrawal1995; Nadasdy, Reference Nadasdy1999, Reference Nadasdy2005; Kimmerer, Reference Kimmerer2002; Houde, Reference Houde2007; Vinyeta and Lynn, Reference Vinyeta and Lynn2013; Ludwig and Poliseli, Reference Ludwig and Poliseli2018; Silva-Ávila et al., Reference Silva-Ávila, Rojas Hernández and Barra2025). In drylands, evaluating the role of TEK is particularly important because it encompasses the documentation of nonmechanized communities and their locally adapted, yet often overlooked, food-related strategies, such as the cultivation of drought-resistant millet crops. Additionally, TEK captures practices deeply rooted in historical experience and living memory, including land-use patterns, seasonal resource planning, information and cultural exchange and communal labor systems, observed in arid environments across diverse livelihood systems, from hunter-gatherer groups to agropastoral communities (e.g., Veth et al., Reference Veth, Smith and Hiscock2005 and references therein, where the connection between archaeology and TEK emerges; Davies and Holcombe, Reference Davies and Holcombe2009; McDonald and Veth, Reference McDonald, Veth, Whallon, Lovis and Hitchcock2011; Ruiz-Giralt et al., Reference Ruiz-Giralt, Biagetti, Madella and Lancelotti2023a; Sharifian et al., Reference Sharifian, Fernández-Llamazares, Wario, Molnár and Cabeza2022; Silva-Ávila et al., Reference Silva-Ávila, Rojas Hernández and Barra2025; Veth et al., Reference Veth, Smith and Hiscock2005 and references therein, where the connection between archaeology and TEK emerges; see Table 1 for further references). Such practices, often neglected or undervalued by dominant development paradigms, not only enrich interpretations of the past but also inform current debates around agricultural productivity, land use and sustainability. Indeed, recent research has underscored TEK potential as a reservoir of adaptive solutions to different environmental and climatic conditions in drylands (Ryan, Reference Ryan2016; Olekao and Sangeda, Reference Olekao and Sangeda2018; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Dabrowski, Dapoigny, Gauthier, Douville, Tengberg, Kerfant, Mouton, Desormeau, Noûs, Zazzo and Bouchaud2021; Biagetti et al., Reference Biagetti, Ruiz-Giralt, Madella, Magzoub, Meresa, Gebreselassie, Veesar, Abro, Chandio and Lancelotti2022; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Janz, Dashzeveg and Odsuren2022; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Dabrowski, Dapoigny, Gauthier, Douville, Tengberg, Kerfant, Mouton, Desormeau, Noûs, Zazzo and Bouchaud2021, Reference Ryan, Kordofani, Saad, Hassan, Dalton, Cartwright and Spencer2022; Conde et al., Reference Conde, Catarino, Ferreira, Temudo and Monteiro2025; see Table 1 for further references). For example, the capacity of farmers to successfully develop agricultural activities in hyperarid areas where mainstream science considers them impossible using only rainfall has been highlighted (see Biagetti et al., Reference Biagetti, Ruiz-Giralt, Madella, Magzoub, Meresa, Gebreselassie, Veesar, Abro, Chandio and Lancelotti2022; Rampersad et al., Reference Rampersad, Geto, Samuel, Abebe, Soto Gomez, Pironon, Büchi, Haggar, Stocks, Ryan, Buggs, Demissew, Wilkin, Abebe and Borrell2023; Ruiz-Giralt et al., Reference Ruiz-Giralt, Biagetti, Madella and Lancelotti2023a), suggesting that scientists should look at the archaeological record with a different perspective, searching for evidence of agrisystems that previously seemed unlikely. By recovering and contextualizing traditional, long-term forms of subsistence, ethnoarchaeology – alongside other archaeological approaches, such as rock art and material culture studies – contributes to the recognition of dryland foodways as expressions of biocultural heritage, systems that integrate ecological adaptation, cultural identity and social memory.

The absence of modern baseline data often constrains our ability to interpret past socio-ecological systems with confidence – particularly in drylands, where both biocultural heritage and biodiversity are frequently misrepresented. An emerging body of research, while not strictly archaeological or ethnoecological, is nevertheless reshaping our understanding of dryland long-term histories and reframing how their archaeological records are interpreted. For instance, Briske et al. (Reference Briske, Huntsinger, Sayre, Scogings, Stafford-Smith and Ulambayar2025) reconsider the ecological significance of grassland biomes in drylands, which are often overlooked or marginalized in environmental narratives. Similarly, Maestre et al. (Reference Maestre, Quero, Gotelli, Escudero, Ochoa, Delgado-Baquerizo, García-Gómez, Bowker, Soliveres, Escolar, García-Palacios, Berdugo, Valencia, Gozalo, Gallardo, Aguilera, Arredondo, Blones, Boeken, Bran, Conceição, Cabrera, Chaieb, Derak, Eldridge, Espinosa, Florentino, Gaitán, Gatica, Ghiloufi, Gómez-González, Gutiérrez, Hernández, Huang, Huber-Sannwald, Jankju, Miriti, Monerris, Mau, Morici, Naseri, Ospina, Polo, Prina, Pucheta, Ramírez-Collantes, Romão, Tighe, Torres-Díaz, Val, Veiga, Wang and Zaady2012) emphasize that arid ecosystems are not biodiversity-poor, as commonly assumed, but in fact exhibit functionality levels often higher than those found in humid environments. To this, we can add studies that highlight the remarkable agricultural biodiversity of drylands, maintained through traditional systems that preserve and cultivate the aforementioned ‘orphan crops’ (see, e.g., Borrell et al., Reference Borrell, Goodwin, Blomme, Jacobsen, Wendawek, Gashu, Lulekal, Asfaw, Demissew and Wilkin2020; Ulian et al., Reference Ulian, Diazgranados, Pironon, Padulosi, Liu, Davies, Howes, Borrell, Ondo, Pérez-Escobar, Sharrock, Ryan, Hunter, Lee, Barstow, Łuczaj, Pieroni, Cámara-Leret, Noorani, Mba, Nono Womdim, Muminjanov, Antonelli, Pritchard and Mattana2020; Burton et al., Reference Burton, Gori, Camara, Ceci, Conde, Couch, Magassouba, Vorontsova, Ulian and Ryan2025). Studies on modern C4 crop cultivations are indispensable to assess misclassified or underestimated potential response to environmental stressors like drought, unpredictable rains or heat stress of marginalized species (Tadele, Reference Tadele2018; Abrouk et al. Reference Abrouk, Ahmed and Cubry2020; D’Agostini et al., Reference D’Agostini, Vadez, Kholova, Ruiz-Pérez, Madella and Lancelotti2022; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Bocksberger, Arandjelovic, Agbor, Angedakin, Aubert, Ayimisin, Bailey, Barubiyo, Bessone, Bobe, Bonnet, Boucher, Brazzola, Brewer, Lee, Carvalho, Chancellor, Cipoletta and Oelze2024; Burton et al., Reference Burton, Mireku Botey, Ceci, Chater, Gutaker, Jackson, Ryan, Seal, Turnbull, Vorontsova, Mattana and Ulian2025; Chater and Lowe, Reference Chater and Lowe2025), but also for understanding what kinds of signals connected with land use management can be detectable in dryland archaeological sites considering that baseline comparison datasets in drylands are scarce (D’Agostini, Reference D’Agostini2022; Ruiz-Giralt et al., Reference Ruiz-Giralt, Nixon-Darcus, D’Andrea, Meresa, Biagetti and Lancelotti2023b; Bar-Oz and Schmidt, Reference Bar-Oz and Schmidt2025).

Archaeology is a fundamental piece of the puzzle

In this study, we aimed to provide examples of archaeological techniques and their recent applications in the study of drylands from the site-level to the landscape- or regional scale, to demonstrate that without employing such approaches, our understanding of these areas remains incomplete and potentially biased. Archaeology offers a multiscalar perspective by integrating excavation and site-level analyses with off-site and medium- to-large-scale spatial approaches such as field survey, landscape analysis or remote sensing (e.g., Challis et al., Reference Challis, Priestnall, Gardner, Henderson and O’Hara2004; Bauer, Reference Bauer2014; Quaranta et al., Reference Quaranta, Salvia, De Paola, Coluzzi, Imbrenda and Simoniello2015; Biagetti et al., Reference Biagetti, Merlo, Adam, Lobo, Conesa, Knight, Bekrani, Crema, Alcaina-Mateos and Madella2017; Phelps and Kaplan, Reference Phelps and Kaplan2017; Bauer, Reference Bauer2018; Sulas, Reference Sulas, Federica and Pikirayi2018; Vetter and Reieger, Reference Vetter and Reieger2019; Harrower et al., Reference Harrower, Nathan, Mazzariello, Zerue, Dumitru, Meresa, Bongers, Gebreegziabher, Zaitchik and Anderson2020; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Liu and Li2020; Greiner et al., Reference Greiner, Vehrs and Bollig2021; Harrower et al., Reference Harrower, Mazzariello, D’Andrea, Nathan, Taddesse, Dumitru, Priebe, Zerue, Park and Gebreegziabher2022; Madella and Lancelotti, Reference Madella and Lancelotti2022; Nabil et al., Reference Nabil, Zhang, Wu, Bofana and Elnashar2022; Nour-Eldin et al., Reference Nour-Eldin, Shalaby, Mohamed, Youssef, Rostom and Khedr2023; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Imbrenda, Lanfredi, Cudlín, Simoniello, Salvati and Coluzzi2023; Rayne et al., Reference Rayne, Brandolini, Makovics, Hayes-Rich, Levy, Irvine, Assi and Bokbot2023; Cigna et al., Reference Cigna, Rayne, Makovics, Irvine, Jotheri, Algabri and Tapete2025). This allows capturing the evidence of past human–environment interactions at the local level, but also their broader systemic implications in human ecology. The scale of analysis depends not on the technique employed – laboratory or field-based – but on the spatial and temporal extent of the collected data, whether derived from a single stratigraphic unit or scalable to regional patterns. Notably, human choices and the environments in which they were made are not separate phenomena but overlapping processes that can be spatially and temporally scaled. The main challenge for archaeology lies in disentangling anthropogenic impacts from natural dynamics within changing ecological niches, while avoiding deterministic interpretations and considering social implications and cultural preferences, but also functional and fitness drive adaptations of plants and animals with which communities interacted.

First and foremost, we aimed to challenge the belief that drylands can only sustain small pastoral communities – an idea that permeated into archaeology theory long time ago, when the hypotheses highlighting the role of large-scale irrigation on the development of early urban and state-level societies appeared (e.g., Clark, Reference Clark1944; Steward, Reference Steward1949; Childe, Reference Childe1950; Wittfogel, Reference Wittfogel1955, Reference Wittfogel1957). In this regard, Wittfogel’s hydraulic hypothesis (Wittfogel, Reference Wittfogel1955) established that the emergence of many urban entities throughout the last six millennia, such as the Mesopotamian states, Ancient Egypt or the Inca Empire, was mainly linked to the implementation of infrastructures to support the use of irrigation for annual crops (see Rost, Reference Rost2022 and references therein for a recent review). Under the assumption that “water has reflected the image of society” (Clark, Reference Clark1944), archaeologists have invested a lot of efforts on the study of past water management systems, mostly because some past state-level civilizations depended on sophisticated techniques of water management for agricultural intensification (Boomgarden et al., Reference Boomgarden, Metcalfe and Simons2019), technological development (Mithen, Reference Mithen2010) and settlement patterns (Schmitz et al., Reference Schmitz, Simberloff, Hofstetter, Haller, Sutton, Simberloff and Schmitz1986). Indeed, research on water techniques for agriculture has provided important pieces of information on the evolution of land use in arid environments (Koohafkan and Stewart, Reference Koohafkan and Stewart2012), as well as on the environmental limits and opportunities of these areas (Marshall and Weissbrod, Reference Marshall and Weissbrod2011). However, this has indirectly led to the marginalization of subsistence strategies and livelihoods that were not based on sedentary, intensive agriculture, but instead relied on extensive and rain-fed agricultural practices.

The contribution of arid environments to food production has been largely overlooked following the Green Revolution of the mid-twentieth century. This is because the Green Revolution only focused on a small group of high-yield crop varieties, irrigation and synthetic inputs in more humid and/or irrigated regions, leaving drylands and the traditional species adapted to them largely unexplored and undervalued, albeit genetically and culturally intact (Borrell et al., Reference Borrell, Goodwin, Blomme, Jacobsen, Wendawek, Gashu, Lulekal, Asfaw, Demissew and Wilkin2020; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Mengesha, Pironon, Pagella, Ondo, Rosa, Wilkin and Borrell2021; Paroda et al., Reference Paroda, Agrawal and Tripathi2024). This has led to the assumption that nonintensive forms of agriculture were (and are) absent or poorly productive in dryland contexts, ignoring key economic activities such as millet agriculture. However, millets are and have been one of the most important agricultural products in arid environments (see Devkota et al., Reference Devkota, Devkota, Mabhaudhi, Nangia, Attaher, Boroto, Timsina and Siddique2025), since they are better suited to low-input management and even support nonsedentary lifestyles due to their minimal water and field requirements (see Biagetti et al., Reference Biagetti, Ruiz-Giralt, Madella, Magzoub, Meresa, Gebreselassie, Veesar, Abro, Chandio and Lancelotti2022). This is not to say that a renewed focus on millet cultivation – or on any traditional crop – could serve as a direct solution to the challenges faced by present-day drylands, especially given the unprecedented demographic pressures and environmental stochasticity of our time. Rather, what archaeology shows is that these crops embody long-term strategies of flexibility and ecological adaptation that allowed past societies to thrive in dryland environments. Recognizing these adaptive logics both at a site-level and at landscape scale can inform the search for sustainable alternatives today, without implying that historical practices can be replicated at modern scales. At the same time, it is important to stress that dryland agriculture should not be understood as inherently linked to demographic growth or intensification. In many cases, these systems were successful precisely because they supported flexible and diverse livelihood strategies, often compatible with mobility and low population densities. From this perspective, “progress” in dryland contexts is better conceived as the capacity to adapt and persist under fluctuating ecological conditions, rather than as a linear trajectory toward the Western notion of growth.

Even though the hydraulic hypothesis has been mostly discredited as a mono-factorial explanation for the development of centralized political systems (Downing et al., Reference Downing, Oakes, Wilkinson and Wright1974; Sagardoy et al., Reference Sagardoy, Bottrall and Uittenbogaard1986; Butzer, Reference Butzer1996; Gupta and Gupta, Reference Gupta and Gupta1998; Harrower, Reference Harrower2009, Reference Harrower2016; Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Vander Linden and Liu2008), its influence can still be noted in scholarly debates regarding the occupation of dryland areas in the past. This is because the idea that sedentary human communities inhabiting arid environments could only be sustained using irrigation to promote agricultural productivity has become an unquestioned axiom. While this may have been the case in certain instances, recent archaeological and ethnoarchaeological research conducted both in the field and through laboratory-based approaches, referenced in this article, suggests that small-scale irrigation and rainfed cultivation, or a combination of them, were enough to sustain human communities in these areas (see, e.g., Lancelotti et al., Reference Lancelotti, Biagetti, Zerboni, Usai and Madella2019), in some cases even leading to the development of state-level political units in areas like the Indus Valley (Madella and Lancelotti, Reference Madella and Lancelotti2022) or the northern Horn of Africa (Sulas, Reference Sulas, Federica and Pikirayi2018; Harrower et al., Reference Harrower, Nathan, Mazzariello, Zerue, Dumitru, Meresa, Bongers, Gebreegziabher, Zaitchik and Anderson2020; Ruiz-Giralt et al., Reference Ruiz-Giralt, Biagetti, Madella and Lancelotti2023a). Archaeological models, when coupled with frameworks, such as the Environmentally Sensitive Area Index (Kosmas et al., Reference Kosmas, Kirkby and Geeson1999) or the Global Aridity Index (Zomer et al., Reference Zomer, Xu and Trabucco2022), can provide spatially explicit tools for assessing land degradation and enable multiscalar reconstructions of human–environment interactions that explicitly account for both environmental sensitivity to rainfall and cultural adaptation to water availability over time. Further, it is imperative to acknowledge that, throughout history, not all communities that developed sophisticated water management techniques evolved into state-level societies. Hence, the advancement of such techniques cannot be understood as a direct measure of societal progress. In fact, even though water harvesting strategies have been considered indicative of agricultural evolution and the specific hydrological conditions to which they had been adapted (Mithen and Black, Reference Mithen and Black2011; Beckers et al., Reference Beckers, Berking and Schütt2013; Hein, Reference Hein2020), the reality is that such systems were not used solely for irrigation. Their utility, especially in drylands, frequently prioritized reservoir management rather than cultivation (Mithen, Reference Mithen2010; Sulas, Reference Sulas, Tvedt and Ostigard2014, Reference Sulas, Federica and Pikirayi2018).

By examining how past societies navigated ecological stress and long-term environmental variability, the archaeological record can serve as a “laboratory” for understanding human adaptive capacity, providing better insights than short-term analyses or speculative Eurocentric models. In particular, archaeology can help challenge Western models of agricultural “progress” by highlighting alternative pathways to food security that are based on long-term processes of ecological adaptation. In addition, it is worth noting that policies are more likely to be effective and embraced when rooted in locally informed, historically situated knowledge (bottom-up approaches) (Cornburn, Reference Cornburn2003; Singh and Singh, Reference Singh and Singh2017). Regarding drylands, this perspective supports the deconstruction of prevailing narratives that frame human–environment interactions primarily in terms of degradation, scarcity and ecological vulnerability (see Biagetti et al., Reference Biagetti, Ruiz-Giralt, Madella, Magzoub, Meresa, Gebreselassie, Veesar, Abro, Chandio and Lancelotti2022 for a nuanced discussion). Moreover, it calls for the development of a new theoretical framework that embraces a holistic understanding of the complex economic systems that have resulted from successful long-term adaptation to arid environments. Altogether, archaeology forces us to reevaluate mainstream assumptions about drylands, showing that far from being marginal areas, these regions have historically fostered sophisticated and sustainable agroecosystems. Notably, sustainable dryland agrosystems can inform present-day research into agricultural techniques and resilient crop varieties offering potential solutions to the escalating issues of desertification, erratic precipitation patterns, loss of biodiversity and increasing heat stress (Altieri et al., Reference Altieri, Nicholls, Henao and Lana2015; Dudley and Alexander, Reference Dudley and Alexander2017; Arias Montevechio et al., Reference Arias Montevechio, Crispin Cunya, Fernández Jorquera, Rendon, Vásquez-Lavin, Stehr and Ponce Oliva2023; Ruiz-Giralt et al., Reference Ruiz-Giralt, Biagetti, Madella and Lancelotti2023a; Okoronkwo et al., Reference Okoronkwo, Ozioko, Ugwoke, Nwagbo, Nwobodo, Ugwu, Okoro and Mbah2024).

Throughout the article, we have proposed examples in archaeology that can help bridge the gap between academic and traditional knowledge by providing evidence-based models that can enable a deep-time understanding of TEK practices in drylands. The challenge, in this sense, is not merely to produce these insights but to effectively translate and integrate them into actionable policy frameworks, which generally operate on different timescales and epistemologies. Recent initiatives have found relative success by encouraging both scientists and policymakers to embrace TEK as a crucial part of designing sustainable agricultural systems (see The Montpellier Panel, 2013; IPCC, Reference Lee and Romero2023). This is even more important for traditionally neglected areas, such as drylands, where long-term resilience is of the utmost importance, more so when we consider the current climatic dynamics toward aridification and population growth. Despite their marginalization within the current global economic system, drylands cover over 40% of the planet surface and are inhabited by more than 2 billion of the world’s population (Devkota et al., Reference Devkota, Devkota, Mabhaudhi, Nangia, Attaher, Boroto, Timsina and Siddique2025), and the numbers keep increasing in relation to the expansion of drylands at the global level. In this regard, we argue that archaeological research can offer a deep-time, comparative perspective on how human communities have historically adapted to resource-limited and unpredictable environments. Traditional agroecosystems are the result of local processes of socio-ecological adaptation that have generated resilient systems capable of persisting for centuries or even millennia. Understanding the mechanisms behind these systems provides valuable insights into the adaptive principles that can inform present-day approaches to sustainability. In this sense, archaeological investigations provide not only a long-term record of human–environment interactions but also conceptual and empirical tools that can guide the development of context-sensitive, bottom-up strategies that effectively address the challenges posed by a changing climate. By drawing on deep historical knowledge, archaeology contributes to building new approaches to sustainable land use that empower local communities reinforcing indigenous priorities and safeguarding biocultural heritage.

Open peer review

For open peer review materials, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2025.10015.

Data availability statement

No new data were created or analyzed during this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article. Artificial intelligence tools were employed for copy-editing in order to enhance the clarity and fluency of the English text.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Stefano Biagetti, Carla Lancelotti and Philippa Ryan for reviewing an earlier version of this article.

Author contribution

-

- Conceptualization: FD and AR-G.

-

- Writing – original draft: FD, CJ-A and AR-G.

-

- Writing – review and editing: FD, CJ-A, OP and AR-G.

Financial support

AR-G is a postdoctoral fellow in the project CAMP funded by the European Union (ERC CoG 2022, CAMP-101088842). CJ-A is a recipient of a Humboldt Research Fellowship for postdocs from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. OP is a postdoctoral fellow in CASEs at UPF. FD is a Kew Research Fellow at Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

Esteemed Member of the Editorial Board and Editor,

I am pleased to submit our manuscript entitled Deep-time perspectives on drylands: archaeology as a lens for understanding long-term livelihood systems and resilience for consideration in Drylands as a perspective paper. We believe this article will be of strong interest to the readership of the journal, as it addresses key themes within its scope, including dryland socio-ecological systems, biocultural heritage, food security, and land use management.

Drylands are often portrayed as marginal areas, unsuitable for long-term settlement and sustainable food production. Our paper challenges this perception by bringing together archaeological and ethnographic evidence that documents how resilient subsistence strategies have historically thrived in even the most arid environments. We argue that archaeology offers unique insights into the long-term dynamics of land use, demonstrating how traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous priorities can inform sustainable practices today.

The manuscript provides a synthetic perspective that highlights the role of archaeological, ethnographic and experimental methodologies in reconstructing deep time socio-ecological adaptations in drylands. By doing so, it emphasizes the value of archaeology not only as a historical discipline but also as a source of evidence-based models that can support future policies and good practices in drylands. In the context of increasing aridification and climate change, these insights are critical to rethinking dryland management and to advancing sustainable agroecosystems tailored to specific environmental conditions. We are confident that this contribution fits well within the aims and scope of Drylands and will be of broad relevance to researchers, practitioners, and policymakers interested in the intersections between past land-use systems and contemporary challenges of sustainability and resilience.

Thank you for considering our submission. We look forward to your response.

Sincerely,

Francesca D’Agostini

(on behalf of all co-authors)