Introduction

This paper aims to contribute to the scientific interpretation of policy legitimacy by investigating evidence-informed policy. Decision-making that is informed by evidence, utilizing transparent and reliable data along with suitable consultation methods, is deemed to foster equitable policies and legitimate governance (Head Reference Head2016). In particular, we focus on how communication can improve the effective use of evidence in policy-making. Its scope encompasses the practices and issues involved in the transmission of evidence-based information from spatial planning experts, technicians, and stakeholders to governmental decision-makers.

Evidence-based policy typically relies on a systematic collection and evaluation of research evidence and carries with it prescriptive methodologies for integrating research into policy. However, the process of policy-making is unavoidably rooted in political values, persuasion, and negotiation (Majone Reference Majone1989). The nature of political decision-making is characterized by inherent conflicts, trade-offs, and compromises between interests (Lindblom Reference Lindblom1979), and evidence is utilized to support differing viewpoints on goals and tools. Thus, policy-makers can make an instrumental use of gathered evidence to support their claims (Langer and Weyrauch Reference Langer, Weyrauch, Goldman and Pabari2021), not least because of their “bounded rationality” (Simon Reference Simon1997). In other words, they “can pick and choose, trying to prove their point” (Faludi and Waterhout Reference Faludi and Waterhout2006b, p. 71), and evidence can be “used for partisan purposes” (Head Reference Head2010, p. 81). Moreover, evidence is often incomplete, conflicting, or inconclusive, which complicates the process of making informed decisions instead of simplifying it (Davoudi Reference Davoudi2006).

Against this background, idealized goals of “evidence-based policy” – which many planning scholars view as an agenda associated with the New Public Management or technocratic policy-making (Davoudi Reference Davoudi2006; Faludi and Waterhout Reference Faludi and Waterhout2006a, 2006b; Lord and Hincks Reference Lord and Hincks2010) – have been significantly tempered and, nowadays, many authors prefer to use the more restrained term “evidence-informed policy” (Davoudi Reference Davoudi2006, p. 16; Head Reference Head2016, p. 473). The goal for policy and its participants, it is argued (Faludi and Waterhout Reference Faludi and Waterhout2006b, p. 71), should consist in being “informed by evidence,” while acknowledging that policy and accompanying political decisions cannot be entirely justified by evidence alone. To guide policy decisions, evidence-informed policy-making seeks to accommodate various forms of expert knowledge, including research evidence, with lay knowledge provided by stakeholders and citizens (Krizek et al. Reference Krizek, Forysth and Schively Slotterback2009; Cairney Reference Cairney2016). This study precisely attempts to shed light on the communicative practices through which information is shared to be used for policy decisions.

Communication is a critical skill, not just a soft one, for practitioners, government agencies, and non-governmental organizations involved in policy-making. It accompanies all stages of the policy process. Without communication, it would be impossible to: raise public attention and authorities’ awareness of policy problems; lobby or recommend policy options to decision-makers; inform the recipients of policy decisions about the public services and benefits they are entitled to; and evaluate and provide feedback on policy outcomes. Most research on “science-policy interfaces” (Sarkki et al. Reference Sarkki, Tinch, Niemelä, Heink, Waylen, Timaeus, Young, Watt, Neßhöver and van den Hove2015), “intermediation” (Neal et al.Reference Neal, Neal and Brutzman2022), and “policy advice” (Galanti and Lippi Reference Galanti and Lippi2022) assumes – even implicitly – that a communicative exchange occurs between actors collecting evidence and those making policy decisions. Both academics and practitioners studying the use of scientific evidence in policy-making agree that communication is essential to that effect (Topp et al. Reference Topp, Mair, Smillie, Cairney, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020; Greenhalgh et al. Reference Greenhalgh, Müller, Thomas, Campbell and Harter2022; ACT 2023; Bandera et al. Reference Bandera, Cattaneo, Galanti and Lippi2024). Communication is vital for coordinating policy-makers and advisors while respecting their identities and spheres of independence (Wildavsky Reference Wildavsky1979; Mulgan Reference Mulgan2007). It is also a crucial competence of academics and practitioners when advising policy-makers, as through communication expert knowledge becomes craft knowledge (Majone Reference Majone1989).

In particular, communication is an invariable element of knowledge brokering, which involves “finding, assessing and interpreting evidence, facilitating interaction and identifying emerging research questions” (Ward et al. Reference Ward, House and Hamer2009, p. 267–8). The purpose of brokering lies in identifying “how best to facilitate the use of research knowledge to inform decision-making” (Lavis et al. Reference Lavis, Ross, McLeod and Gildiner2003, p. 169), i.e., “finding and using appropriate mechanisms for transferring research into policy and practice” (Ward et al. Reference Ward, House and Hamer2009, p. 267), with the ultimate goal of achieving improved policy-making (MacKillop et al. Reference MacKillop, Quarmby and Downe2020). Brokering is primarily focused on assisting decision-makers in recognizing and refining policy problems, identifying and selecting the key attributes of knowledge that meet users’ needs in the decision-making context, and packaging and disseminating evidence (Michaels Reference Michaels2009; Ward et al. Reference Ward, House and Hamer2009; Meyer Reference Meyer2010; Parkhurst Reference Parkhurst2017). For all these purposes, communication is necessary.

Despite its significance, the communicative competencies, channels, and instruments that can facilitate evidence utilization remain empirically under-scrutinized in policy studies. We agree with scholars (Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Liggett, Gilbert and Cvitanovic2024, p. 7) asserting that the social sciences should find “improved ways to foster knowledge exchange” and that social scientists can be “critical in helping to communicate the politically and socially important messages underpinning ‘hard’ science findings.” Hence, we argue that it is time for scholarly inquiry to shed light on the actors, mechanisms, and processes involved in policy communication. This work aims to explore this field. And while it has a limited scope and dataset, we hope it can stimulate interest by providing insights and perspectives for further research.

We conceptualize communication as the exchange of messages containing policy content among multiple subjects, through a specific language, including translating and contextualizing information into a comprehensible code. We consider its effectiveness as the ability “to accomplish a purpose,” i.e., to produce “the intended or expected result,” rather than being deemed “useless” and “futile” (Bina et al. Reference Bina, Jing, Brown and Partidário2011, p. 573). In this context, we define evidence as:

all types of science and social science knowledge generated by a process of research and analysis either within or without the policy-making institution (Juntti et al. Reference Juntti, Russel and Turnpenny2009, p. 208).

Through communicative interaction, evidence is exchanged, knowledge is created, brokered, and transferred, advice is offered, and learning takes place. Moreover, awareness of the significance of evidence is heightened, motivation for its use is encouraged, and trust in its providers is established.

This study aims to discuss the relevance of communication and identify the most effective methods and channels to enhance it. We address the research question: Is communication in any way related to the use of evidence for policy formulation and decision-making? Our analysis focuses on the policy area of spatial planning, where policy communication is unavoidable.

Indeed, spatial planning is a policy area inherently receptive to evidence-based knowledge. Planners have consistently advocated for collecting all pertinent evidence to guide decision-making. In fact, evidence has been integral to the field of urban and regional management and development even before planning became a recognized profession (Krizek et al. Reference Krizek, Forysth and Schively Slotterback2009). Gathering evidence and information is critical for planning since:

Patrick Geddes’ famous aphorism: “survey before plan,” coined in the early 20th century, remained every planning student’s grand rule of good practice for many decades (Davoudi Reference Davoudi2006, p. 16).

Even in the 21st century, “nobody would deny that evidence is a vital element in making plans or in any kind of policy-making for that matter” (Faludi and Waterhout Reference Faludi and Waterhout2006a, p. 7). If planning entails the ability “to obtain a more desirable future by working toward it in the present” or, at least, the attempt “to avoid future evils by anticipating them” (Wildavsky Reference Wildavsky1973, p. 127–8), even by resorting to imagination as a strategic resource to that end (Phelps and Valler Reference Phelps and Valler2024), it is self-evident that at least some foundational information is required on the current state of a given area to be planned before setting future goals. Therefore, urban planners have long prioritized gathering relevant information on specific topics (housing needs, transport infrastructure, demographics, etc.) and territories (Lord and Hincks Reference Lord and Hincks2010) to inform decisions (Krizek et al. Reference Krizek, Forysth and Schively Slotterback2009) made by political officers. While this practice may not be innovative, it is still used to a wide extent. Professional planners typically survey a territory, assess its strengths and weaknesses, engage with residents and stakeholders to surface expectations and needs, and subsequently present this evidence, along with their interpretations, to decision-makers to inform the design of policy options aligned with the latter’s priorities and goals. This makes planning a most likely case (Eckstein Reference Eckstein, Greenstein and Polsby1975), i.e., a field where we expect to find confirmation of the critical relevance of communication for policy decision-making.

Scholars assert that to facilitate knowledge exchange between practitioners, stakeholders, and decision-makers, there is a need for “better communication” to “overcome the difficulties in understanding complex and technical language” (Fernandes et al. Reference Fernandes, Pires, Ramos, Rodigues, Teles and Polido2024, p. 12), and that “making evidence accessible requires better communication channels between policy and research communities” (Davoudi Reference Davoudi2006, p. 20). And yet, scant attention is paid to actual communicative practices and dimensions concerned with the utilization of evidence and its brokering, whose effectiveness, impact, and political character have attracted limited scholarly attention (MacKillop et al. Reference MacKillop, Quarmby and Downe2020), despite the critical role that politics can play in processes of evidence use (Pielke Reference Pielke2007; Parkhurst Reference Parkhurst2017).

Our work aims to complement the existing literature in three ways. First, by shedding light on one essential component of knowledge brokering, namely, communication. Second, by focusing on a policy field characterized by a relatively high technicality. Third, by analyzing attitudes and behaviors of different kinds of policy-makers: local administrators, regional legislators, and representatives of interest organizations. We resort to a sequential explanatory mixed-method design involving a survey of local elected officers and interviews with regional legislators and stakeholders participating in lawmaking on land governance and spatial planning in Lombardy, Italy’s largest region. Such a mixed-method approach allows a triangulation of data in order both to corroborate findings, “thus increasing the validity of results,” and to “gain multilevel understanding of the phenomenon under study” (Mele and Belardinelli Reference Mele and Belardinelli2019, p. 336) by capturing “various perspectives at different levels of analysis” (p. 344).

The remainder of the paper is structured into five sections. The subsequent one presents the conceptual framework of this study, situating it within the theoretical discourse surrounding the division between science and policy-making while highlighting the pertinent communicative dimensions involved. The third section outlines the research design employed in our study. The fourth section illustrates the primary results, and the following one reflects on the findings presented. The concluding remarks connect the findings to the existing literature on the communicative challenges inherent in the interaction between science and policy.

Literature review

Policy studies have investigated a wide array of topics pertaining to the communicative dimensions of policy-making. Seminal work has been developed on communicative skills and tools to support policy arguments (Hambrick Reference Hambrick1974), emphasizing that the relevance of evidence is determined by the cogency, persuasiveness, and clarity of the argument, as well as the plausibility, feasibility, and acceptability of the conclusions presented (Majone Reference Majone1989). Subsequent studies focus on communication styles and tones that can facilitate evidence utilization. For instance, storytelling (Davidson Reference Davidson2017; Druckman Reference Druckman2022; Natow Reference Natow2022) can foster empathy while emphasizing the moral and political significance of policy solutions (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, Mcbeth, Radaelli, Sabatier and Weible2018) through a specific, persuasive frame (Rincón Reference Rincón2021). The narrative policy framework advocates for communication of scientific facts in alignment with the values and expectations of the audience (Crow and Jones Reference Crow and Jones2018; Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, Mcbeth, Radaelli, Sabatier and Weible2018; Goldman and Pabari Reference Goldman, Pabari, Goldman and Pabari2021), for example, by interpreting new evidence through the lens of preexisting beliefs (Weible et al. Reference Weible, Heikkila, deLeon and Sabatier2012). Far-reaching analyses have also examined interactive practices and collaborative arrangements whereby specialists and decision-makers co-produce and share policy-relevant information (van den Hove Reference van den Hove2007; Cairney Reference Cairney2016). Brokerage endeavors can especially aim to build the capacity to use knowledge by enhancing access to it and training its users (Oldham and McLean Reference Oldham and McLean1997; Michaels Reference Michaels2009; Ward et al. Reference Ward, House and Hamer2009; Meyer Reference Meyer2010; MacKillop et al. Reference MacKillop, Quarmby and Downe2020; Neal et al. Reference Neal, Neal and Brutzman2022). Studies also stress the meaningfulness of institutional arrangements that make science-policy exchanges iterative, allowing for drawing on earlier experiences and learn from the interaction between evidence suppliers, brokers, and users (Lemos and Morehouse Reference Lemos and Morehouse2005). This collaborative approach is also notably found in spatial planning (Faludi and Waterhout Reference Faludi and Waterhout2006a), where theoretical proposals for collaboration and deliberation have been set forth and extensively implemented to mitigate the limitations associated with top-down, positivist decision-making (Innes Reference Innes1996; Healey Reference Healey1997).

Drawing from different backgrounds, this body of literature underscores the essential role of communication in both policy design and implementation. It further highlights that “while communication is critical at boundaries” between research and policy-making, “because that is where tension arises, it is nonetheless difficult to make it happen (…) convincingly and credibly.” (Michaels Reference Michaels2009, p. 996). Building on these premises, this study concentrates on the operational aspects of policy communication, specifically exploring how and to what extent communication of technical information impacts the decisions made by lay policy-makers.

Theoretically, we refer to the longstanding thesis that policy-makers and scientific experts represent two distinct communities with differing beliefs, values, and attitudes towards knowledge (Caplan Reference Caplan1979; Dunn Reference Dunn1980). While this interpretation has faced challenges, particularly given the “large number of positions of policy influence held by social scientists” (Radaelli Reference Radaelli1995, p. 174), there remains broad consensus on the existence of two distinct cultures in the scientific and the policy realms (Gluckman Reference Gluckman2018) and their inhabitance by different epistemic communities (van Stigt et al. Reference van Stigt, Driessen and Spit2015). A robust body of literature in policy studies (Majone Reference Majone1989; Head Reference Head2016, p. 478–9; Cairney Reference Cairney2016; Fernández Reference Fernández2016; Cairney and Kwiatkowski Reference Cairney and Kwiatkowski2017; Davidson Reference Davidson2017; Dunn and Laing Reference Dunn and Laing2017; Dunn Reference Dunn2018; Hajdu and Simoneau Reference Hajdu, Simoneau, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020; Greenhalgh et al. Reference Greenhalgh, Müller, Thomas, Campbell and Harter2022) and a more limited focus on planning (Davoudi Reference Davoudi2006; Faludi and Waterhout Reference Faludi and Waterhout2006a; Krizek et al. Reference Krizek, Forysth and Schively Slotterback2009) pinpoint various factors, outlined below, that reinforce this view. All these features contribute to a relatively poor policy uptake of research outputs by politicians (Cherney et al. Reference Cherney, Head, Povey, Ferguson and Boreham2015; Goldman and Pabari Reference Goldman, Pabari, Goldman and Pabari2021).

Firstly, science and policy exhibit distinct epistemologies. “Policy is rarely determined solely by evidence” but is rather “made around a whole lot of considerations, public opinion, political ideology, electoral contracts,” among others (Gluckman Reference Gluckman2018, p. 93–4). To inform policy decisions, politicians may prioritize information from more accessible and trusted sources, such as non-technical contributions from citizens and stakeholders, over expert-produced knowledge, particularly in the field of planning (Krizek et al. Reference Krizek, Forysth and Schively Slotterback2009). It is commonly doubted (Pielke Reference Pielke2007) that evidence suppliers and policy-makers connect in “a linear process” in which the latter “simply compile coherent and neutral evidence as the basis for decision” (Mele et al. Reference Mele, Compagni and Cavazza2014, p. 846). Policy-makers take into account various perspectives, values, interests, and beliefs rather than relying exclusively on evidence, adhering to theoretical frameworks, and trusting the robustness of research methodologies validated through peer review. This phenomenon aligns with Carlile’s (Reference Carlile2004) concept of a “semantic” knowledge boundary arising between subjects with consistently different worldviews and the derived interpretations of facts. From this descends that policy and science have distinct conceptions and metrics of success and failure.

Secondly, there tends to be a misalignment between the designs of scientific research and the knowledge needs of policy-makers. Addressing long-term structural and societal problems necessitates a variety of knowledge types and profiles; however, decision-makers typically seek prompt and clear solutions, which are not always readily accessible. Furthermore, scientific analysis does not yield a best solution due to a persistent lack of consensus within scientific communities on assumptions, approaches, techniques, and the interpretation of results. While science offers probabilities and confidence levels, along with occasional inconclusive evidence, accountable politicians require some degree of certainty when making decisions that frequently involve taxpayer funding.

Thirdly, scientific inquiry and policy-making operate on diverging timeframes. The former unfolds through structured projects that often require significant time to complete and frequently become available in academic publications years after their conclusion. Scientists are motivated by career and reputation advancements to publish in prestigious journals rather than to provide prompt advice to policy-makers on pressing issues and urgent needs (Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Liggett, Gilbert and Cvitanovic2024, p. 12). In contrast, policy-making has to do with “political events and public sentiment that may change rapidly” in “more fluid and chaotic” processes (Dunn and Laing Reference Dunn and Laing2017, p. 150). This disconnection between research and policy agendas complicates efforts for scientists to align their objectives with the requests of policy-makers and deliver timely, effective solutions. Moreover, if policy-makers “don’t have a policy-acceptable solution to them at a point in time, they will usually move on to another issue” or resort to alternative sources (Gluckman Reference Gluckman2018, p. 96), such as interest groups.

Finally, an additional distinction between science and policy, which this work emphasizes, pertains to their respective languages. We align with the views of several authors (Brownson et al. Reference Brownson, Royer, Ewing and McBride2006; Cairney and Kwiatkowski Reference Cairney and Kwiatkowski2017; Hajdu and Simoneau Reference Hajdu, Simoneau, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020) who stress the importance of recognizing that science alone does not generate public policies:

research results don’t speak for themselves outside of the research community, and must be made appropriate for consumption in policy settings and among the public. (Stamatakis et al. Reference Stamatakis, McBride and Brownson2010, p. 2)

This is because, for laypeople – including most politicians and local administrators – scientific language can appear jargonistic, overly technical, and ultimately inaccessible. Such a “syntactic boundary” (Carlile Reference Carlile2004) between individuals who use different grammatical structures and communicative codes can represent an insurmountable barrier. For scientific evidence to be used, it must first be made usable (Lindblom and Cohen Reference Lindblom and Cohen1979). To this purpose, it should be communicated appropriately and effectively, i.e., consensus must be reached on the meaning of fundamental terms and concepts. In planning contexts, expert-produced documents and processes are often laden with technicalities that make them difficult for lay stakeholders to understand (Diduck and Sinclair Reference Diduck and Sinclair2002). Consequently, communication becomes a crucial element of concern in the use of evidence generated and brokered by experts.

Cognitive sciences have extensively demonstrated that, in human communication, sources (in our case, experts) of objective information do not exert a mechanical influence on recipients (in this case, policy-makers), who are not necessarily specialists. When communicating scientific knowledge, technical concepts, or policy recommendations, scientists and experts frequently operate under the assumption that recipients use their reflexive cognitive system (Kahneman Reference Kahneman2011). However, recipients may not necessarily be inclined to do so (Crow and Jones Reference Crow and Jones2018). Thus, the critical challenge is to translate specialist knowledge into languages and codes that are accessible to laypeople, ensuring that it can be understood and, possibly, applied.

To this end, the communication of expert knowledge should encompass several operational considerations. First, evidence should be conveyed in a language that is appropriate for the audience, avoiding scientific concepts and terms that may sound cryptic to recipients. Instead of lengthy explanations, it is advisable to use short sentences and present ideas in a step-by-step manner. To summarize quantitative data and highlight salient information, the use of bullet points, bold text, tables, and graphs is recommended, as these formats are welcomed by politicians since they provide “a simple and immediate representation of the data” (ACT 2023, p. 24). An infographic can convey much more, and more effectively, than many words (Cairney and Kwiatkowski Reference Cairney and Kwiatkowski2017; Dunn Reference Dunn2018; Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Liggett, Gilbert and Cvitanovic2024). This approach is particularly suitable for spatial planning, which typically heavily relies on visual material such as maps, graphs, and designs.

Second, communication should be responsive to the demands for evidence as much as possible. Information is particularly usable when it is timely, i.e., it is provided before decisions are made (Le Grand Reference Le Grand2006). Scientists aiming to influence the policy process should identify the appropriate moment to communicate evidence, for instance by leveraging policy windows (Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Liggett, Gilbert and Cvitanovic2024), i.e., act when the political conditions are favorable for generating receptivity among their target audience (Cairney and Kwiatkowski Reference Cairney and Kwiatkowski2017). However, as noted above, reliable information cannot always be produced quickly through scientific investigation. When timely data is unavailable, it is crucial to swiftly package the existing information for transfer to decision-makers. It may also be appropriate to identify and share important, albeit provisional, information as it becomes accessible (Gregrich Reference Gregrich2003).

Third, evidence producers and brokers should be adept at summarizing large volumes of information. When addressing the knowledge required for a decision, the number of materials and information can be overwhelming. It is ineffective to present all this information to decision-makers, given their “limited ‘bandwidth’” (Topp et al. Reference Topp, Mair, Smillie, Cairney, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020, p. 34) and time constraints (Davoudi Reference Davoudi2006; ACT 2023). Complex reports and lengthy documents should be replaced with short, concise texts. These texts (for example, policy briefs), whether based on hard analytical techniques such as systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or evidence gap maps (Topp et al. Reference Topp, Mair, Smillie, Cairney, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020), or on simpler assessments of existing knowledge, should serve several purposes: they should prioritize essential, indispensable content while minimizing or eliminating irrelevant information that does not enhance understanding; they must ensure that critical information – those details that help to reduce uncertainty for decision-makers – is not excluded or diluted among less pertinent data; and they should avoid unnecessary repetition of the same material (Cairney and Kwiatkowski Reference Cairney and Kwiatkowski2017; Hajdu and Simoneau Reference Hajdu, Simoneau, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020; Greenhalgh et al. Reference Greenhalgh, Müller, Thomas, Campbell and Harter2022). The primary goal is to prevent communicative disorder, which could compel the audience to spend excessive time reading and processing information, thus increasing their cognitive burden. Providing “a concise evidential synthesis to minimize cognitive burden is more effective than bombarding” the audience with more information than “they are willing and able to process” (Cairney and Kwiatkowski Reference Cairney and Kwiatkowski2017, p. 6).

Fourth, communication must be organized in a coherent and logically consistent manner. It is essential to select and structure the appropriate evidence to clarify the key points at hand. Typically, policy briefs and issue papers follow a similar format consisting of: an overview or summary of contents (abstract); a review of previous efforts to address the policy issue (state of the art); a diagnosis detailing the scope, severity, and causes of the problem; a presentation and evaluation of alternative solutions (Dunn Reference Dunn2018); and recommendations for actions to be taken (Siepen and Westrup Reference Siepen and Westrup2002; Dunn Reference Dunn2018). In order to convey messages to diverse audiences, it might also be necessary to select different bodies of evidence and disseminate them through multiple communicative tools, with different languages tailored to the various target audiences and their information needs (Majone Reference Majone1989; Dunn Reference Dunn2018; Hajdu and Simoneau Reference Hajdu, Simoneau, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020).

Fifth, there is a need to simplify useful yet complex concepts and evidence. Simplification is defined as the result of investigative efforts on present and future constraints and assumptions related to a policy or policy instrument. Potential solutions to policy problems are frequently intricate, as the combinations of policy alternatives and their effects can be vast. Therefore, evidence communication must aim to reduce this complexity. This can be achieved, for example, by selecting intervention options based on the logic of appropriateness. This means presenting evidence addressing various social concerns involved in a policy decision, which is crafted in the most effective ways to meet policy objectives and is relevant within the local policy context (Parkhurst Reference Parkhurst2017).

Policy-makers cite the impact on real people as one of the most important factors in enhancing the relevance of scientific evidence for policy (Dunn Reference Dunn2018). As previously noted, this is one of the reasons storytelling, i.e., “translating complex research findings into stories that [are] meaningful to decision-makers” (Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Liggett, Gilbert and Cvitanovic2024, p. 7), is frequently employed as a communication tool. Utilizing storytelling or other framing techniques, which facilitate information retention, proves more effective than simply presenting evidence as though it inherently communicates its message (Cairney and Kwiatkowski Reference Cairney and Kwiatkowski2017). This does not mean adopting a demagogical tone or oversimplifying the complexity of scientific knowledge. Instead, communicators should always be mindful of what the audience knows and can understand, as well as what may be most relevant to them. When engaging with politicians, this involves focusing on issues and problems where public consensus is at stake.

Sixth, if communication is essential for a more evidence-informed policy, policy organizations should commit and allocate resources to understanding their target audiences, and provide their staff, especially researchers, with training in communicative skills (Siepen and Westrup Reference Siepen and Westrup2002; Trench and Miller Reference Trench and Miller2012; Hajdu and Simoneau Reference Hajdu, Simoneau, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020).

Within this framework, we aim to determine whether a mismatch exists between expert knowledge and policy in the context of spatial planning and if this may affect the use of expert-produced evidence in policy decisions. To this end, we have developed the research design described in the following section.

Methodology

Case study

The policy field on which the analysis focuses is spatial planning. According to Italy’s Constitution, spatial planning is a shared legislative domain between central and regional governments: Italian regions legislate on the process of urban plan-making and are also responsible for developing and approving their own spatial plan (Regional Territorial Plan). In Lombardy, this is the main tool for territorial governance. It aligns regional and sectoral planning with the area’s physical, environmental, economic, and social conditions, and provides a framework for coordinated territorial planning across the region, ensuring that town plans work together to implement regional development goals.

At the local scale, town plans outline the context and motivations for policy choices; they establish targets regarding volumes, demographics, land-use conversions, density, etc.; and, in terms of their implementation, they include detailed rules and standards that guide how private developers can contribute to achieving overall targets. Their main strategies, which notably include the areas designated for urban expansion and regeneration, are encapsulated in masterplans, which constitute the town plan alongside zoning maps and regulations. They are subject to a prior Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). This is a public, participatory process in which decision-makers are not involved, whereby practitioners release scoping documentation, environmental reports, formal opinions, and prescriptions. Following SEA, whole town plans, as commissioned by executives to town services or outsourced to private professionals, must statutorily be made accessible to the public, local stakeholders, and elected officers who are members of the municipal assembly prior to voting. They are then adopted by municipal assemblies and subsequently approved after a public participation procedure in a second reading. Hence, the regeneration and development zones included in the masterplan are particularly prominent on the local political agenda and publicly well known within local communities. They represent key strategic outputs for the plans, as they typically include urban infilling and transformation for housing, retail, or industrial purposes, as well as public infrastructure and services.

To recap, spatial planning is a policy field in which Italian regions have extensive powers and municipalities hold full competence: every local elected politician has a role in shaping the primary instrument of planning, which encompasses the entire territory of the municipalities and regulates the use of both private and public land. However, planning is a topic of high technical complexity, especially for non-expert decision-makers (Bianchetti and Balducci Reference Bianchetti and Balducci2013; Caudo and De Leo Reference Caudo and De Leo2018). In fact, here, most local and regional planning decision-makers are laypeople (Mazzoleni Reference Mazzoleni2020). Lay regional lawmakers have support structures for gathering and storing information, blending and summarizing available evidence, reading and condensing the texts to be deliberated. On the contrary, local elected officers do not, as they are not granted allowances or funding to support such kind of activities. The next section provides insights into the technical expertise of the decision-makers we surveyed.

The planning sector appears to be a prominent area of sub-national policy-making in Italy, marked by the broad and varied participation of stakeholders who act both on their own initiative and in reaction to government proposals. Organized interests are diffuse and, alongside residents, statutorily enjoy access in the town plan-making process, which is open to non-governmental contributions in the form of requests and comments, as well as through SEA consultations. Through these channels, they can reasonably expect to influence decisions (Mazzoleni Reference Mazzoleni2022). This also occurs at the regional scale, where organized interests, which all have regional-level branches – some of which we interviewed – frequently interact with political decision-makers, especially on the occasion of legislative reviews and new bills. At least in Lombardy, the spatial planning sector seems poorly contested. This is characteristic of distributive policy arenas, where benefits (i.e., development and building permits) are concentrated among a few, while the costs (i.e., environmental externalities) are spread out over numerous participants (Wilson Reference Wilson1980). In fact, locally, there tends to be a collaborative atmosphere between authorities, residents, and interest organizations: the level of conflict is low except for environmental groups and the relationship between the majority and opposition assembly members (Mazzoleni Reference Mazzoleni2022). Nevertheless, planning is not a policy area of great importance in terms of re-election, especially at the regional level. Usually, the outcomes of planning choices only become visible years after they are fixed in local and regional spatial plans, well after the end of their decision-makers’ term in office.

Mixed-method design

Based on a pragmatic epistemology (Mele and Belardinelli Reference Mele and Belardinelli2019), mixed methods include in a single study more methods of the same category (such as experiments, field study, clinical trials, etc.) or of different ones (Yin Reference Yin2006). We adopt a sequential “quanti-qualitative explanatory” design where the qualitative phase “is aimed at explaining and refining the results” obtained in the first, quantitative stage (Mele and Belardinelli Reference Mele and Belardinelli2019, p. 336). The sequence unfolds in two phases. The first consists of a web survey of local elected officers, and the second of semi-structured interviews with regional lawmakers and stakeholders. Both were conducted in the spring of 2024 and focused on decision-makers’ opinions on evidence communication and use in spatial planning.

The quantitative analysis is based on the premise that the saliency of the proposed policy for decision-makers’ voting behavior is connected to their understanding of the contents involved. We investigate this link by correlating local officers’ personal comprehension of specific contents of spatial plans with the relevance of those aspects in their voting decisions. If a positive correlation is found, this would suggest that communication of evidence-informed policy matters is important for decisions regarding those contents.

Afterwards, to validate these findings and potentially uncover other significant variables, we qualitatively explore the preferred formats and channels of spatial policy communication. This field research primarily consists of semi-structured interviews with regional lawmakers and interest group representatives to obtain a comprehensive view of the communication and use of evidence. We selected respondents who have directly experienced the processes of production and communication (stakeholders) as well as reception and use (lawmakers) of evidence in spatial policy-making and, hence, are suitable and reliable sources of information for our analysis. Semi-structured interviews are particularly effective for capturing first-hand individual perspectives and for revealing informal dynamics and patterns of evidence use, which cannot be detected through other methods. However, this approach has a downside: the data collected might be subjective or influenced by political bias, raising concerns regarding its representativeness and generalizability. To address this critical issue, we conducted a purposeful selection of interview participants focused on their institutional roles and political affiliations, with the goal of achieving the greatest possible diversity in viewpoints across these dimensions. As a result, the interviews targeted eight lawmakers from both the majority and the minority parties who currently serve or have served on the planning committee of the Regional Assembly, including the former chairwoman. Additionally, we interviewed stakeholders who had commented and offered evidence-informed material regarding the region’s spatial plan and planning legislation: the regional directors of the building trade association and the WWF, and representatives from the National Trust for Italy (Fondo per l’Ambiente Italiano) and the National Federation of Natural Parks.

Following Yin’s (Reference Yin2006) framework, we connect the two phases at various levels. First, both methods address the same research question, concerned with finding a connection between communication and the use of evidence in the generation and formulation of policy alternatives as well as in the ensuing decision-making (Howlett et al. Reference Howlett, Ramesh and Perl2009). Second, the focus of analysis is the same, consisting of decision-making in spatial planning in Lombardy, which is investigated by collecting data from local decision-makers (survey) and regional policy-makers (interviews). Hence, the two samples are separate. This allows for independent measures of the investigated phenomenon. At the same time, however, the two samples are part of the same regulatory arena, insofar as regional representatives, lobbied by stakeholders, legislate on the spatial planning process, which is carried out by local representatives. Fourth, the data collection methods differ, and yet they contain analogous – in some cases, overlapping – variables. Thus, findings obtained through the two methods can be easily compared and possibly integrated. Finally, the analysis of the results obtained from both observational strategies aims to check if “the same story” (Yin Reference Yin2006, p. 45) can be described for both levels, hence validating the respective findings. The discussion of results in Section 5 precisely aims to supply an integrated picture of our findings, concerned with the relevance and challenges of the communication of evidence to inform spatial policy.

Data

For the survey, we used the universe of all 372 municipalities in Lombardy where a new plan had been adopted within the previous five years. To ensure its validity, the questionnaire was pilot-tested with two local councilors and two mayors. It was then sent to all official email addresses (N = 677) that could be found online, with the remaining surveys being sent to the organizational secretariat of the municipality or, where applicable, of the municipal assembly. The first page of the survey stated its purpose and requested respondents to provide informed consent to participate in the research.

In the survey, a set of questions was meant to operationalize communicational barriers to the usability of evidence as well as to assess the use of evidence provided in plan documents. The former thereby concerns policy formulation, informed by evidence. Respondents were asked to state (on a 1 to 5 scale) their level of understanding of the following items related to either contents or format plan documents: the specific vocabulary; technical implementation standards; information on the current situation (context analysis); forecast data (demographics, built volumes, land take, etc.); graphics and drawings; the impact of the plan on the environment, on climate change, on residents’ health, on residents’ quality of life, and on local economic development.

We also focused on the dimensions of communicative effectiveness of town plans and checked which of their features were most (and least) appreciated by asking respondents to declare their agreement with the following statements: regarding the summary of evidence, “Documents were not accompanied by an understandable and useful summary” and “Documents were too thick”; as for organization of evidence: “Documents were poorly organized. For example, they did not list priorities or clearly explain the project lines”; and, concerning language, “the vocabulary was too specialized.”

With respect to the use of evidence in policy adoption, we asked how much counted (1–5 scale) in respondents’ voting decision: their personal understanding of the documents (strategies, goals, and tools); development and regeneration areas set by the plan; the opinion of the regional environmental agency and of the local health authority, which are statutorily required.

As a major limitation of the study, the survey results do not statistically represent the universe, as only 193 individuals, with 157 providing valid answers, completed the questionnaire out of a possible 4,379 respondents. This limitation confines how much the data can be generalized. We believe the low response rate is due to 3,702 assembly members, particularly in small municipalities (less than 5000 inhabitants), lacking official email addresses. To reach them, we depended on the local authority’s secretariat to forward our request for completing the questionnaire. We suspect that this did not consistently occur, even though we sent out reminders.

The subsequent qualitative investigation was deployed as a validity check (Mele and Belardinelli Reference Mele and Belardinelli2019) of findings from the survey, also because the latter does not provide statistically representative opinions. Twelve semi-structured interviews aimed to collect information from both evidence demanders (lawmakers) and suppliers (stakeholders) based on their experience regarding the most effective ways and communicative channels for the exchange of evidence and opinions between experts and decision-makers. The interview template was submitted to the Ethics Commission for Research in Psychology of the Catholic University of Milan, receiving approval on May 8, 2024. All participants provided written consent for the interviews, based on the anonymity of answers.

Findings

To explore the relevance of communication to lay policy-makers for the use of evidence, we must first verify that the recipients are not experts. Therefore, to gauge planning policy knowledge, we inquired whether respondents’ occupation was anyhow related to planning: construction entrepreneur, real estate agent, surveyor, town planner, architect, civil engineer, geologist, agronomist, administrative lawyer, or civil servant working in planning services. Out of 157 respondents, planning professionals made up 17.6% of those from small municipalities (less than 5,000 inhabitants), 28.8% of medium-sized towns (5,000 to 50,000 inhabitants), and 25.8% of larger towns. We can therefore consider a large majority of respondents as non-experts and, second, reasonably exclude that the size of the governmental unit significantly impacts the level of knowledge of officeholders in our sample.

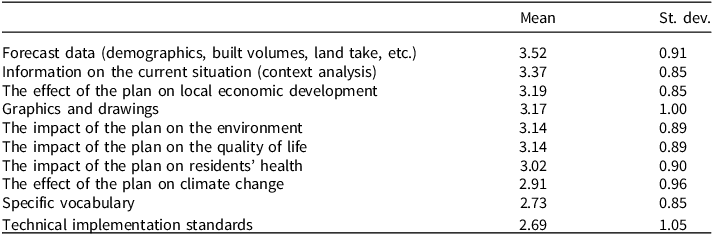

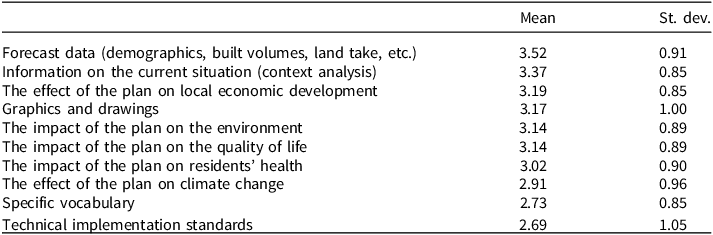

Table 1 presents decision-makers’ grasp of plan contents. The items are ordered in accordance with how easy they were to understand on a 1 (very difficult) to 5 (very easy) scale.

Table 1. Decision-makers’ seizure of communicative features in town plans: descriptive statistics (N: 126)

The items that were least understood were the technical language and implementation standards, the latter being by nature inherently specialized and pertaining to building parameters such as land plot density, building height, construction materials characteristics, building sites regulations, etc. In contrast, information regarding context and forecasts, which is commonly expressed in textual form, was easier to comprehend than the graphic representations. The expected impacts of the plans on the environment and health aspects proved to be less easy to grasp.

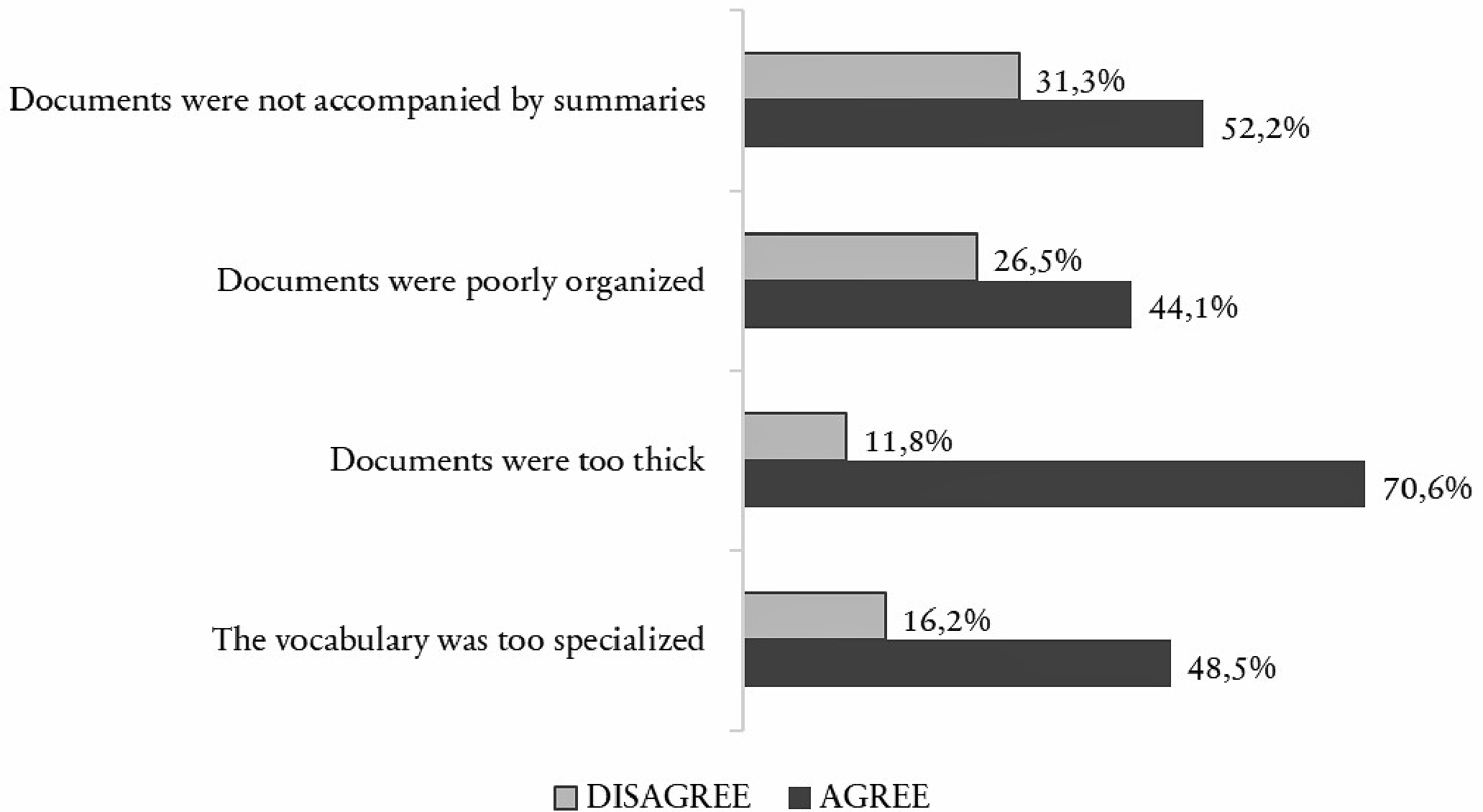

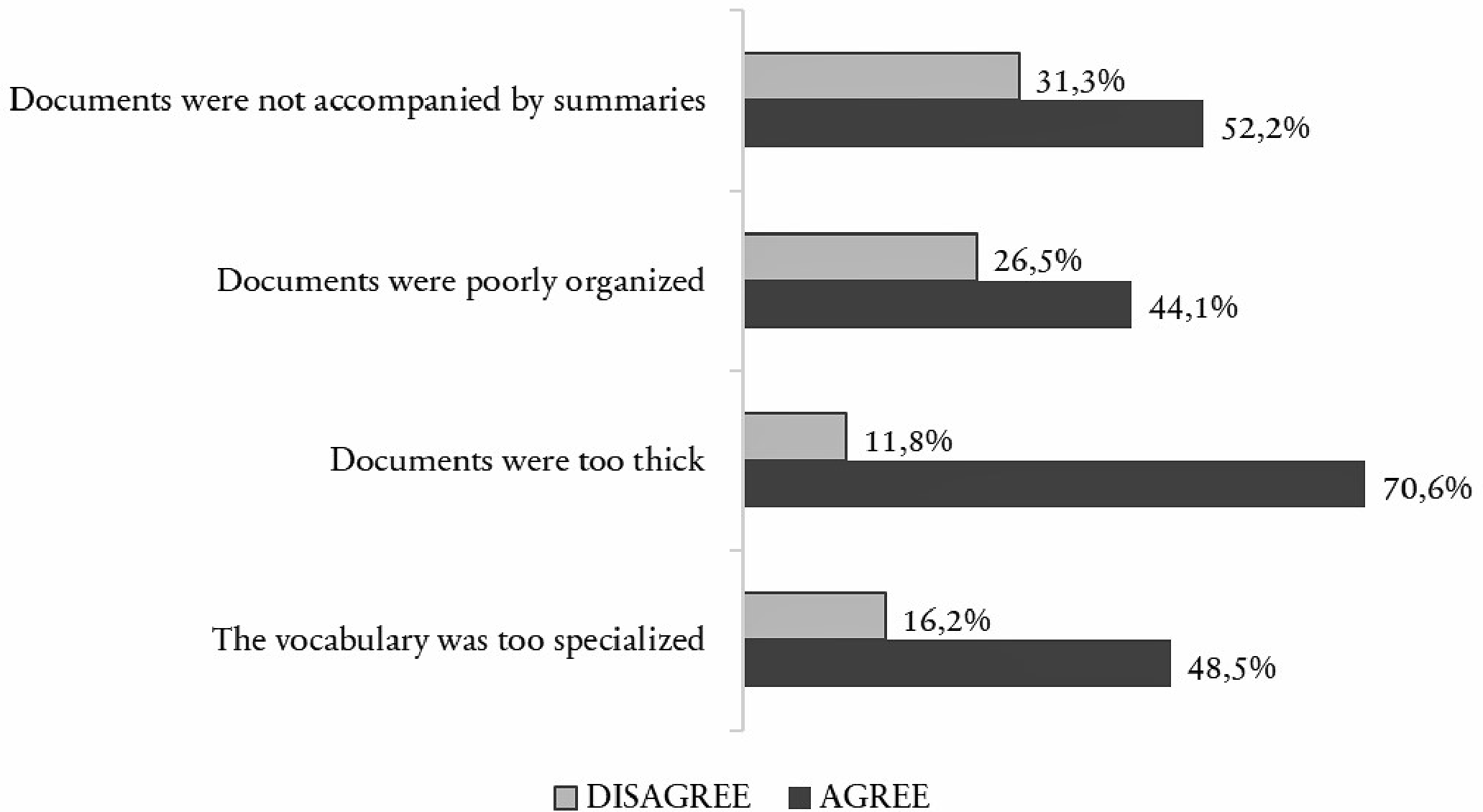

Through the question on the presentation of evidence in plan documents, we examined the reasons behind the difficulty in understanding their elements, targeting only those respondents who had rated at least three items of the question on their understanding of plans as “difficult” or “very difficult,” with a list of possible reasons. The relative frequencies show that in all cases, most respondents agree with the statements proposed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Respondents’ opinions of the communicative features of plan documents (N: 67–68).

Note: data for the answer option “neither agrees nor disagrees” are not shown. Source: The Authors.

The volume of material to be processed emerges as the most significant challenge, particularly since it lacked a summarization. These findings would corroborate the literature, which suggests that products of expert work are perceived as too cumbersome, poorly organized, and laden with jargon. Therefore, they need to be validated through the qualitative analysis.

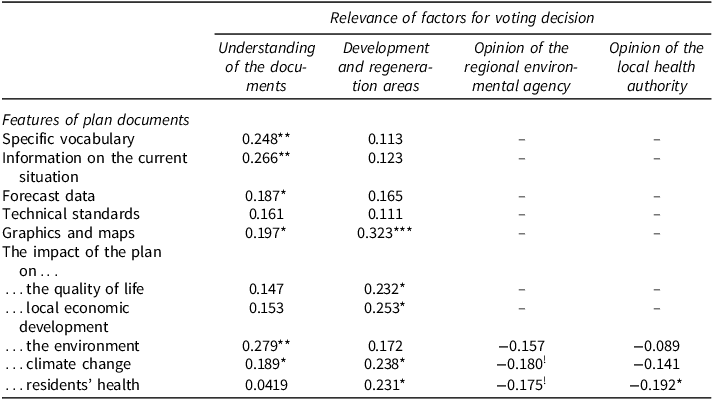

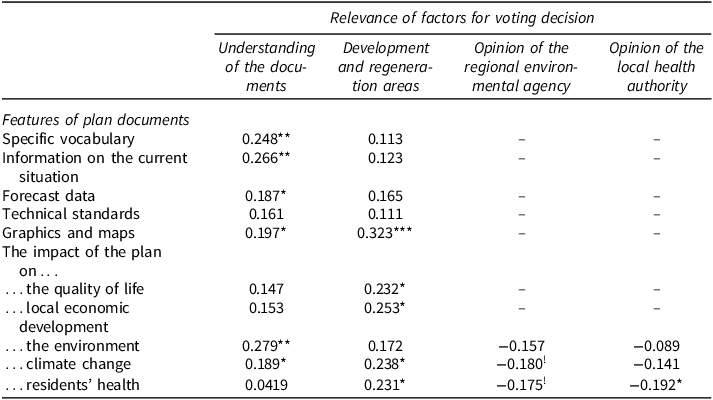

By correlating the previously illustrated responses, which concern the formulation of policy options in draft plans presented by the executive to the assembly, with the weight of selected factors on voting choices – hence, the policy adoption by the assembly – we obtain the results presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Correlation (Pearson’s r) between respondents’ understanding of plan documents and voting behavior (N: 107–111)

Note: ! p < 0.10. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

We find positive and significant correlations, suggesting that the more understandable the entries in the first column of Table 2 were, the more relevant personal understanding and areas for development or regeneration were to voting behavior. The only item for which no significant relation occurs is technical implementation standards, which are indeed the least understood elements of plans (see Table 1); so, a lack of statistical correlation is not surprising here since few respondents did understand them. Conversely, negative correlations emerge between the comprehension of plan impacts on the environment and health and the formal opinions on local plans statutorily issued by the competent regional environmental and health agencies. In other words, as local officers better understood the impacts of plans, the appraisals from governmental agencies became less influential on their voting decisions on those same plans; however, only one of these relationships is significant, with two others nearing marginal significance.

To summarize, the positive correlations we observed, although modest, yet with significant effects, suggest that clear communication on planning policy strategies and outputs can be viewed as beneficial to local decision-makers’ personal judgments on them. Specifically, decision-makers tend to use comprehensible policy documents to inform their attitudes, whereas external opinions (such as those of the environmental and health agencies) tend to carry less weight. Hence, it would appear that the application of evidence is tied to how it is presented.

However, the findings drawn from the survey are limited by both the non-representative nature. Therefore, we sought further explanations by interviewing members of the Regional Assembly and regional-level stakeholders. This enabled us to gain further insights by highlighting themes emerging from the viewpoints of respondents.

In particular, our qualitative analysis can help us delve into the characteristics communication should have to be effective in the eyes of lay decision-makers. Of the regional lawmakers we interviewed, only one – a self-employed surveyor – can be considered as professionally familiar with planning, whereas all others are employed or self-employed in different economic sectors or in the public administration, in areas unrelated to planning. Therefore, we can reasonably assume their technical unacquaintance with plan documents and materials. This was actually one of the criteria we followed in our purposeful sampling.

Firstly, through the survey, we could not highlight decision-makers’ favorite communication channels and instruments, through which evidence can inform the formulation of policy. In fact, they apparently hold diverse levels of meaningfulness. On the one side, as the stakeholders’ preferred communication channels, two mentions were received by: committee hearings, public conferences, public conferences organized in partnership with public authorities and agencies, the production and transmission of reports and papers, press releases or conferences to launch reports and research results, and participation in working groups with the regional government. Conferences focused on a specific topic with targeted invitations, as well as on-site inspections and surveys, are mentioned once. On the other side, for lawmakers, the most preferred communication occasion consists of informal meetings and workshops (5 out of 8 mentioned it). Then follow: committee hearings, closed-door meetings with stakeholders, closed-door informal meetings with experts (pro bono), and concise documents with abstracts or executive summaries (4 mentions); documents – provided they feature practicality – and public conferences (3 mentions); phone calls and one-to-one briefings, and documents and talks illustrating best practices, such as policies and regulations successfully implemented by other regions (2 mentions); and, finally, WhatsApp chatgroups comprising policy experts, the Internet, and Ted Talks (1 mention each). To summarize, the views of politicians and stakeholders significantly differ.

Secondly, a sharp informational asymmetry exists between majority and minority members of the Regional Assembly. When divided into majority and minority, the survey respondents’ numbers are too low to gain any significant information in this respect. Members of the majority are pre-informed by regional Ministers and General Directors about incoming provisions, and are supplied with preparatory documents (drafts, gray documentation) and reports concerning new bills. They are also kept up to date on the Executive’s appraisal (usually backed by majority legislators afterwards) of proposed amendments. Ultimately, they receive all the necessary information for their legislative activity, especially for committee work. This practice is acknowledged by both the majority and opposition and is even considered normal and legitimate. This is accompanied by an ongoing informal, off-the-record dialogue between regional Ministers and majority Assembly members on legislative bills and other proposals tabled in the assembly. Concerning the review of the regional spatial plan, the majority rapporteur stated:

The political dialogue was with the regional minister, of course, but then we went to identify some of the more specific issues through discussions with the technical experts of the Executive (…), and I coordinated a direct dialogue with some majority lawmakers on some of the more specific issues of the plan.

From this flows that, when considering formal ways to access information and evidence, interviewed politicians belonging to the minority also mention formal requests to access documents to be responded to by the regional Executive within one month. Moreover, it is surprising that Assembly committee hearings, whose importance is often overlooked by the interviewed stakeholders (one even describes them as “a waste of time”), are highly valued by several lawmakers from both the majority and the opposition. Stakeholder hearings in the planning committee are particularly noted with reference to extremely important acts, such as the general variation of the region’s spatial plan, approved in 2021, and the 2019 law on urban regeneration.

However, as one would expect, both politicians and interest representatives recognize that evidence presented during committee sessions is likely to be leveraged for partisan purposes by policy-makers, for whom – as in other parliamentary venues – “political considerations” typically “take precedence” over a thorough examination of the information provided and the search for “the best evidence available” (Geddes Reference Geddes2018, p. 300). As a stakeholder put it, referring to minority parties: “We fear that the opposition may use our information instrumentally, for their own consensus.” This would amount to a use of information which is not “honest” (Pielke Reference Pielke2007).

The relevance of committee hearings may be due to them being the privileged venue for lawmaker-stakeholder exchanges, given that the latter find it more efficient to directly contact, rather than Assembly members, Executive ministers and services, in both public occasions and closed-door meetings, prior to the drafting of policy measures:

The most in-depth work is done with the regional structure to “chew” administrative devices and procedures [before they are decided upon]. (…) Decisions are made by the Executive, so we turn to them. Only when a draft measure reaches the Assembly, and it is hence difficult for us to recover, do we contact the lawmakers. But we do not usually send them the material. We only meet them during committee hearings. On those occasions, we refer to the information material (data) we produce, but we do not provide them with the data.

Even lawmakers from the majority acknowledge the relative importance of the Assembly as compared to the Executive in policy drafting and formulation. With respect to the region’s spatial plan, one asserted that:

This is a truly complex document in which the Regional Assembly was only able to intervene in a few areas, unable to overturn the Plan proposed by the Executive, which is a document drafted – in its strategies and largely in its content – by experts, and therefore by officials and professionals. The Regional Council can only request corrections on specific points.

Fourthly, lawmakers seek contextualized information whenever they are called upon to address a policy issue, favoring conciseness and practicality over an excess of information. For them, the absence of usable summaries and abstracts, coupled with an overwhelming amount of material, is perceived as an obstacle to their use in terms of decision-making. As articulated by a regional representative from the majority:

Certainly, this is one of the problems (…) I must say that I have found very few cases where [suppliers of specialist knowledge] are capable of producing documents, perhaps with effective abstracts, which would allow for a more effective reading, especially for lawmakers who, I repeat, deal with a difficult mass of documents to manage. But this applies more or less to everything, both in terms of the approach with stakeholders and the documents to be approved. It is evident that you cannot read everything you vote on; it is harsh to say it, and maybe someone may be scandalized by this.

This preference applies to documents and events (conferences, workshops, meetings) where evidence and information are presented for their consideration.

Finally, similarly to what emerges from the survey, legislative jargon and technicalities appear to be particularly problematic. Three lawmakers, from both the majority and the opposition, express difficulties in understanding existing norms and legislation. They also highlight that legislative texts can be misinterpreted and, as for their scope and impact, underestimated even by experts and lawmakers themselves. Thus, the communication of such documents emerges as a rather critical concern, with one interviewee mentioning introductory notes of legislative pieces (for instance, of EU regulations and directives) as primary sources for comprehending the norms.

Discussion

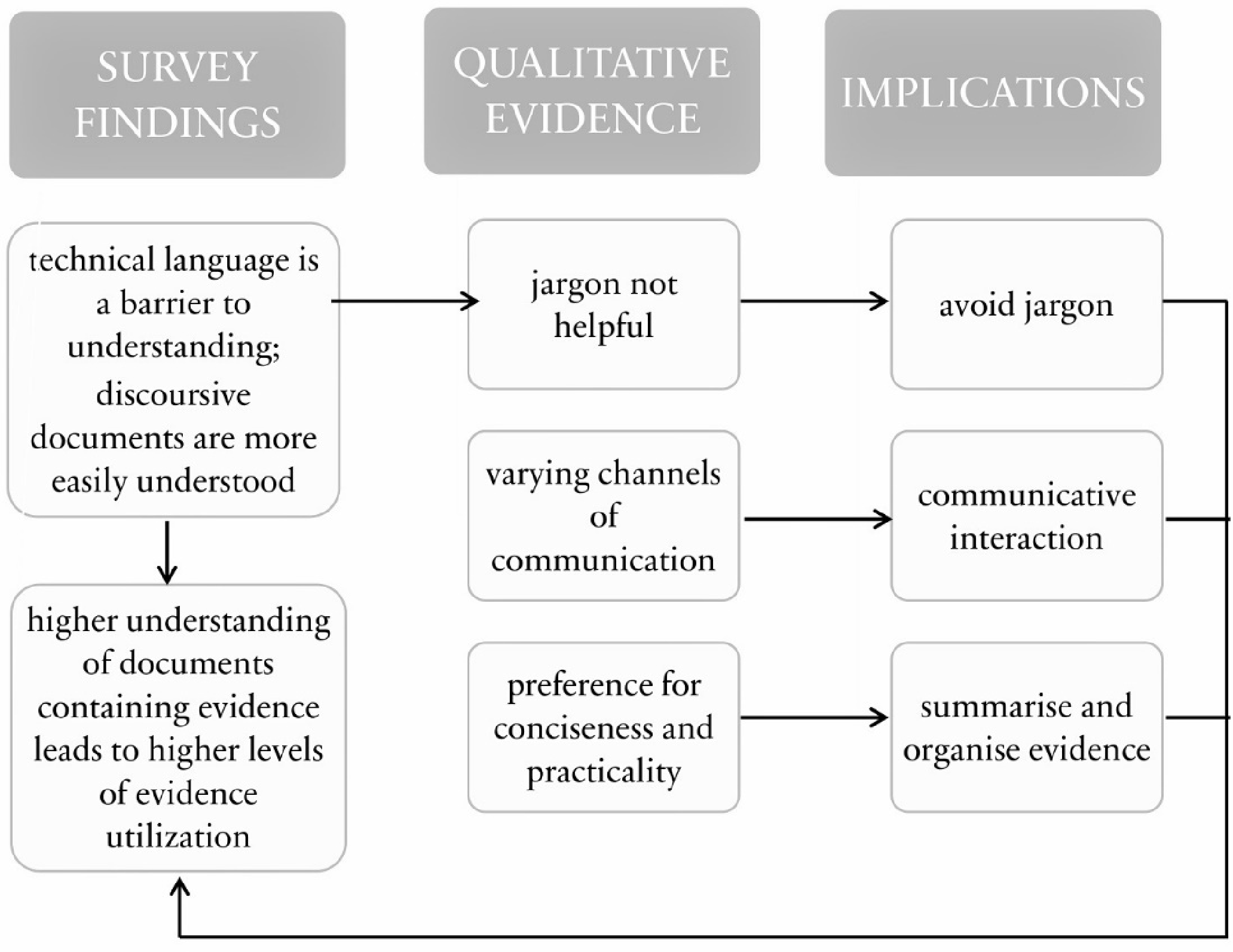

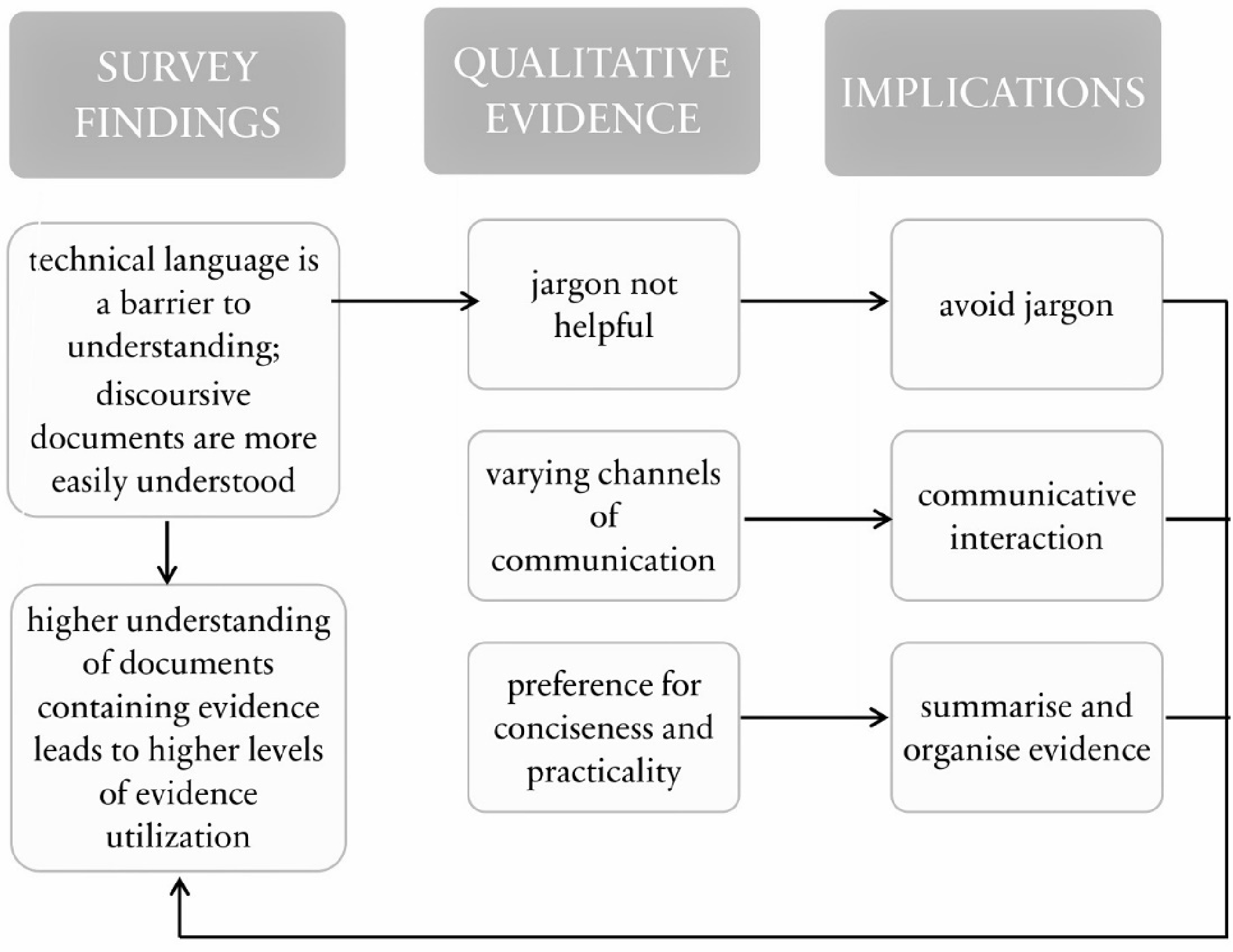

The results we have reached do not cast into doubt the argument put forward by the prevailing literature focusing on the relationship between expert-produced policy materials and their use by non-specialist policy-makers. In fact, they seem consistent with it, and we have hence expanded it to spatial planning policy. As for our case study, at both the local and regional levels of government, communication seems a significant factor in facilitating the uptake of the evidence, presented in the stage of policy formulation, which can thus be presented as more legitimate. The findings of the qualitative investigation notably confirm and enhance those of the quantitative analytic strategy. Figure 2 depicts the findings and implications of our analysis and their respective connections.

Figure 2. What helps the use of evidence by policy-makers? Findings of the two analytic phases and respective connections.

Source: The Authors.

Communication can be considered as enhancing the transparency of the rationales for decisions and allowing for managing the uncertainty in the complex context of decision-making in spatial planning. To this end, it is widely understood that significant challenges include constructing “better ‘learning’ processes” and “establishing new channels and forums for mutual understanding” (Head Reference Head2010, p. 87) between evidence providers and users. We can thereby add building communication skills to the several tools that, according to scholars (Lavis et al. Reference Lavis, Ross, McLeod and Gildiner2003; Ward et al. Reference Ward, House and Hamer2009; Meyer Reference Meyer2010; MacKillop, Quarmby, and Downe Reference MacKillop, Quarmby and Downe2020; Goldman and Pabari Reference Goldman, Pabari, Goldman and Pabari2021), could strengthen the effectiveness of knowledge brokerage: dedicating staff and incentives for knowledge-transfer, formally recognizing and training brokers, creating institutional processes that support continuous dialogue between science and policy, and regularly evaluating brokerage impacts to improve future practice. All this would ensue in a “cultural shift” that could “facilitate the ongoing use of research knowledge in decision-making” (Lavis et al. Reference Lavis, Ross, McLeod and Gildiner2003, p. 165).

Nevertheless, embarking upon participatory and co-production practices can be challenging in smaller policy-making arrangements, such as in Italian town planning, where most local government units, which have the legal responsibility for planning their whole territory, are medium-sized or small. These units lack resources, including political will, to go beyond a mere linear “transfer” or “transmission” (van den Hove Reference van den Hove2007, p. 815) of data and information from technicians to decision-makers. Scale is all but irrelevant in this regard. While regional lawmakers, despite not being specialists, can afford to be supported in selecting, summarizing, and translating pertinent technical information, local elected officers encounter barriers in processing it, notably, as highlighted through our survey, due to the sheer volume and technicality of the material they are expected to handle and vote on. In this respect, three notable takeaways emerge.

First, specialist language seems a barrier to the uptake of evidence, as the specific vocabulary used in planning tools is the least understood communicative element by local officeholders, alongside technical standards that are specialized by definition. There is a positive correlation between the levels of understanding of terminology and the relevance of personal comprehension of plans concerning representatives’ voting behavior. Those who struggle with complex terminology are less likely to depend on their own comprehension when voting on the documents. This issue also extends to the distinct communicative codes employed in planning policy documents, namely graphs and maps. This result is validated by regional lawmakers we interviewed, for whom technical jargon acts as a barrier as well. Consequently, unless they find some specialist help, in their legislative action, these policy-makers will likely rely on external cues, often political in nature, rather than the documents’ contents themselves. To recap, at both levels of government, we found evidence of a semantic boundary (Carlile Reference Carlile2004) between experts and policy-makers. Communication can be crucial in overcoming it. Communication is relevant for evidence utilization, although it is not a powerful predictor.

Second, policy documents ought to be organized by presenting the most salient points in a practical and concise manner. The findings from the survey questions on plan material, displayed in Figure 1, are corroborated by interviewees. Several of them – especially belonging to the minority – mention the meaningfulness of written sources, when they succinctly identify the main points of an issue and substantiate them with data. Therefore, both the survey and interviews underscore the importance of providing politicians with readable and usable materials through abstracts and summaries that clearly outline the intended goals and expected outcomes of the decisions to be made.

Third, lawmakers’ responses helped us identify the preferred communication mechanisms that could not be made to emerge through the survey. Apparently, politicians strongly appreciate communication channels and boundary activities that involve forms of interaction, as unveiled by other studies (Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Liggett, Gilbert and Cvitanovic2024). Committee hearings, and especially working groups, one-to-one meetings in informal settings, and WhatsApp chats are all recognized as means of establishing a direct relationship with knowledge producers. Indeed, these channels can enable participants to consider the “other’s perspectives, creating conditions for communicative discourse” (Mitchell and Leach Reference Mitchell and Leach2019, p. 89) through “meaningful and open dialogues” (Gardiner et al. Reference Gardiner, Liggett, Gilbert and Cvitanovic2024, p. 15), thereby developing “mutual understandings” (p. 7). This reflects the broader normative aspiration in science-policy interfaces to build social processes that involve interactions between scientists and various participants in the policy-making process. These interactions should facilitate the exchange, co-evolution, and collaborative development of knowledge, all intended to enhance decision-making (van den Hove Reference van den Hove2007).

Conclusions

The objective of this work was to emphasize the centrality of communication, notably of expert knowledge, in policy decision-making. We did not explicitly delve into epistemological issues concerning the proximity or distance between science, research, and policy. Instead, we chose a pragmatic approach and explored the practices and operational features of boundary policy communication and interaction between experts and non-specialist decision-makers. We presented data on conceptual dimensions put forward in the relevant literature by investigating the field of planning, which is characterized by a high level of technicality and is seen as a most likely case to put extant knowledge to test. We used a mixed-method design to validate the findings obtained through different techniques, and we showcased that a limited understanding by elected officers of the issues at stake in a policy process prevents specialist evidence from making its impact on policy. Therefore, our findings suggest that expecting decision-makers to use expert-produced information may be illusory unless its communication considers users’ needs, literacy, and preferred communicative channels.

From the evidence-supply side, a further challenge arises, namely that in the communication flows that involve experts and policy-makers, the former are not always able to convey to the latter messages that they themselves might deem scientifically irrelevant (Hajdu and Simoneau Reference Hajdu, Simoneau, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020), yet are considerable for policy application purposes. And it does not always look feasible to devote significant time to cultivating the professional expertise to craft effective policy communication. Thus, knowledge creators seeking to influence politicians to choose the best evidence should communicate their findings in a clear and strategic manner to policy-makers, while ensuring that the information produced is tailored to their needs, also with the aim of increasing “the policy relevance” of their analyses (Topp et al. Reference Topp, Mair, Smillie, Cairney, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020). This would largely depend on experts’ ability to understand the policy context and accordingly adapt the format and contents of their communication.

With this work, we have attempted to offer a pragmatic contribution to the understanding of policy legitimacy. As seen, evidence is constitutive of spatial planning policy. Our study, though limited in scope, highlights how communication can facilitate the use of evidence by decision-makers. Their understanding of policy documents and materials looks to impact their choices, but it is not perceived as the most important basis of decisions. As underlined in both theoretical and more pragmatic approaches to studying policy, evidence is always subject to interpretation. For this reason, rather than evidence-based policy-making, which suggests that objective, unquestioned evidence does underpin policy choices, several scholars prefer talking of evidence-informed policy-making. This requires knowledge exchange between experts and lay policy-makers, which can be facilitated by brokers. In turn, communication is an essential dimension of knowledge brokering. Therefore, our study adds empirical support to existing literature on “governing through evidence” (Mele et al. Reference Mele, Compagni and Cavazza2014), which recognizes that knowledge brokering is inherently relational but neglects the crucial final step: how to convey it through effective communication. We suggest putting greater effort to connect academic literatures on communication and brokerage, thereby broadening the understanding of the latter.

To conclude, communication could hence be seen as a tool for enhancing the legitimacy of policies informed by expert-produced evidence. This lesson might extend to other policy sectors, where policy alternatives, especially those of a technical nature, should be translated into accessible languages tailored to the specific target audiences of decision-makers.

The challenges for evidence communication to be effective, i.e., to inform policy decisions, according to our survey respondents (see Figure 1) and interviewed actors, reside in being concise (i.e., not too thick), meaningfully organized (i.e., and presenting summaries and abstracts), and clear (by avoiding too specialist a language) to a potentially diverse audience, whose receptivity varies. “Written material should be concise and concrete, with few points rather than long reports,” as one lawmaker summarized it. Thus, in line with Lord and Hincks (Reference Lord and Hincks2010), we recommend that local planning authorities clearly link their policy decisions to supporting “information backed by evidence” (Rincón Reference Rincón2021, p. 427), especially when identifying issues and options and choosing a preferred developmental path. Communicative channels and practices should be optimized to engage the audience using the most suitable vocabulary and (textual, visual, or hybrid) codes that enable lay policy-makers to grasp not only the contents but also the saliency of the evidence presented. Knowing the recipients’ needs in advance seems crucial to this effect. Therefore, drawing on Parkhurst’s (Reference Parkhurst2017) contribution, “appropriateness” seems to be the keyword in policy communication. Effective communication to inform policy is also appropriate when it conveys high-quality, relevant evidence in a practical and organized manner, thereby informing the “policy concerns at stake” and furthering the application of such evidence “to the local policy context” (p. 118).

Future research could shed light on whether and how incentives within reflexive policy organizations, aimed at encouraging specialists to collaborate with communication professionals and cultivate effective communicative skills (Hajdu and Simoneau Reference Hajdu, Simoneau, Šucha and Sienkiewicz2020), could enhance the opportunities for evidence-informed policy influence.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UKX0AZ

Acknowledgements

The authors thank colleagues at the Language Centre (Selda) of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy, for providing language editorial support, which was funded by the same university under grant d.1 (2023) for the research “Risk reduction policies and communication.” The authors also thank regional assemblyman Mr Pietro Bussolati for accepting to test the interview template and providing insightful comments on it. The authors thank the reviewers and editor for their invaluable guidance.

Author contributions

Martino Mazzoleni is responsible for conceptualization, methodology, quantitative data analysis, visualization, and writing (original draft, reviewing, and editing). Maria Chiara Cattaneo is responsible for interviews, qualitative data analysis, and writing (original draft and editing).

Funding statement

The authors received funding by Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore under grant d.3.2 (2022) for the research “Communicating science. Mediation and mediators of scientific knowledge in a complex society.” Authors alone are responsible for conducting the study and writing the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.