It was approaching midnight on the outskirts of Ituura. Mwaura and I had just returned home from watching a UEFA Champions League game at the local Motel.

We had taken our usual route home, walking in the darkness down from the Motel along the main road. Mwaura was anxious about the possibility of being stopped by policemen at that late hour, we hurried towards a turning leading towards Ituura’s homesteads. Underneath the looming silhouettes of trees, we continued along a path that was barely visible in the gloom. Rainy season had arrived, and a chill was in the air. Both of us were wearing our raincoats, though Mwaura had gone out in his ‘slippers’ (a pair of flip-flops), much to the chagrin of Catherine. We bantered back and forth about the match as we went, Mwaura disappointed by his team Manchester United’s struggles against Belarusian side, BATE Borisov. ‘Jose Mourinho is the worst Manchester United manager of all time’, I insisted, trying to provoke him. Mwaura was having none of it.

Eventually we arrived at his father’s shamba (the Kiswahili word for ‘garden’ or ‘farmland’), and adjacent to it, an unfinished stone house. We passed through a makeshift gate. I could hear Cheezi, the family’s enormous watchdog, begin barking from somewhere beyond. Rounding the corner from the gate, a small wooden house with a corrugated iron roof came into view. We approached the door and, after a few knocks, Catherine answered with not a vague hint of annoyance before returning to where she was sitting in front of a soap being broadcast on the television by the Gĩkũyũ-language station Inooro TV.

The house’s earth floor was damp beneath our feet. Mwaura took a seat next to the television to text his friends from his university in Kitui about the result of the football match and I set about heating up some cai, milky tea usually made with tea leaves and cinnamon, left-over from earlier in the evening. The silence of night was punctuated only by the sounds of insects, distant cars speeding on the main road, faint voices on the television, and the hissing of the gas canister that I had switched on to warm up the tea.

From the bedroom, separated from the living space by a thin wall of timber, came the sounds of Mwaura’s father muttering to himself in his sleep. The muttering soon became a whimpering, panicked and super-natural. Somewhat surprised, Mwaura asked his mother what was going on with his father. ‘He’s stressed’, she answered (E na stress, Mwaura). Her tone was almost one of reproach. Not simply an explanation, it was a reminder to her son of the physical and mental sacrifices his father made to maintain their household, of the toll taken by his money worries, the worries and concerns of the distinctive figure of the wage-labouring family patriarch. The conversation ended there.

*

While Mwaura and I spent our weekends perambulating the neighbourhood, his father Kimani remained largely absent from the homestead, away at the border with Tanzania waiting for goods to transport to Nairobi in his lorry. When Kimani did return to the homestead, he often made an impression, even inadvertently, as he had done that cold night in September 2017.

Earlier that evening, Kimani had cut an exhausted figure, beset with worries and tired from driving. As usual, he had returned home to sleep after travelling from the town of Namanga on the Tanzanian border. Kimani worked as a long-haul lorry driver, using his own lorry, which he had purchased through loans and savings from his previous employment as a pickup driver. Since then, he had used his lorry to transport cargo of goats (mbuzi) and stone (mawe) to markets in Nairobi. But being tasked with actual work – with the short-term contracts to transport these goods – was an uncertain prospect for Kimani, and he could go weeks waiting at the border until suddenly a job transpired and he made enough cash in a few days to pay his debts left over from previous months. After ferrying goods to Nairobi, he would often return home to sleep, spend some brief time with his family and tend to his homestead. When at home, Kimani could regularly be glimpsed, panga in hand,Footnote 1 working on his shamba or tending to the hedges and fences that surrounded his plot.

We saw in Chapter 1 that Kimani’s neighbourhood is emblematic of Kiambu’s geography – a patchwork of smallholder farms that have shrunk with subdivision, interspersed with much larger tea plantations owned by businessmen and Kiambu’s wealthy elites. Unlike some of his neighbours, Kimani’s shamba was fairly large at slightly over an acre, but generally most men in the neighbourhood were all in much the same predicament. Kimani’s brother Mwangi, for instance, worked as a taxi driver in Nairobi and was also absent for most of the working week, coming home only on Saturday and Sunday to oversee matters at his homestead (mũciĩ). Other local men worked a variety of jobs – selling sausages at the roadside in nearby towns, transporting agricultural produce in pickup trucks, or working as matatu drivers in the local transport infrastructure. The absence of middle-aged and older men from the neighbourhood during the weekdays was starkly evident, though a few would arrive in the evenings – exhausted construction workers, and the local shopkeeper who sold bread and mandazis (a type of doughnut) to the people of the neighbourhood (andũ a itũũra) from his kiosk.

It was on these occasions, when struck by the sheer extent of Kimani’s exhaustion, that I began to reflect more concertedly on what I believed to be his predicament as the family’s breadwinner. I wondered what sustained Kimani in spite of the immense stresses, the economic setbacks, and struggles that characterise life for families like his in peri-urban Kiambu, many of which are reliant on a mode of what some anthropologists have described as ‘wage-hunting’ (Gill Reference Gill, Day, Papataxiarchis and Stewart1999; Kalb, Kasmir and Eräsaari Reference Kalb, Kasmir and Eräsaari2016: 51; cf. Day, Papataxiarchis, and Stewart Reference Day, Papataxiarchis, Stewart, Day, Papataxiarchis and Stewart1999: 7–10) in the informal economy carried out by one of or both parents. Kimani’s predicament – as we shall soon see – is a reminder of the precarity that defines the income of Kenyan families, the sheer temporal unpredictability of when money would be ‘found’ (as he put it) to cover household costs.

Focusing on Kimani’s struggles, this chapter discusses the way senior men like him understood their obligations to create the social future by working for money and retaining land, to earn school fees for their children, and see them towards a better future. But Kimani also contrasted these obligations with what he saw as the delinquency of other men – their desires to project wealth and reputation over the proper locus of morality: the family. Kimani articulated his moral agency in negative terms, that he had ‘denied’ himself the life of consumption lived by so many others.

Kimani’s perspective provokes a deeper inquiry into the moral principles underpinning economic life in Kiambu – especially a suspicion of consumption, of turning fungible cash into alcohol by selling land. For senior men, selling land was said not to ‘make sense’, an economic ‘mistake’ (makosa) and a transgression against the wish of one’s parents that such land ought to be a family heirloom. Discourses about land’s inalienability (Weiner Reference Weiner1992) speak to different categories of wealth placed in hierarchical order: the morality of household maintenance and reproduction, the immorality of short-term ‘fun’, and its pathway towards destitution. The perspectives of Kiambu elders hark back to Bohannan’s (Reference Bohannan1955) path-breaking essay on Tiv spheres of exchange. For Tiv, different sorts of wealth or ‘things’ could be categorised, belonging in different ‘spheres’ that could be hierarchically arranged. Bohannan showed that the lowest-ranking sphere involved exchangeable objects – food for subsistence traded in market exchanges – while the highest-ranking sphere involved persons, particularly women acquired through bridewealth. As Bloch and Parry note, in Bohannan’s model, conversions between spheres ‘were the focus of strong evaluations – grudging admiration for the man who converted “up”, scorn for the one who converted “down”’ (Parry and Bloch Reference Parry, Bloch, Parry and Bloch1989: 12). Great prestige could be won from investing wealth achieved via farming if exchanged for wives.Footnote 2 Utter condemnation could come from selling value-producing things such as land that would otherwise secure one’s subsistence.

These are not straightforward ‘cultural’ ideas about what counts as wealth (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1992), but pragmatic discourses about the material basis of social reproduction and its destruction.Footnote 3 These anxieties about poverty reflect genuine fears of falling into it for those who live on the economic margins, and the need to resist it keenly. Such perspectives are reflected across Africa, and the ethnographic canon throws up numerous similar examples of moral debate about life’s self-reproducing generativity and the dangers of its destruction through economic activity viewed as improper or indeed wholly anti-social (Shipton Reference Shipton1989; cf. Ferguson Reference Ferguson2006: 72–3). Hannah Elliott’s research has described the ‘evil’ ‘desires’ (tamaa) that have animated the sale of land in northern Kenya to developers by businessmen who, it turns out, expropriated ‘community’ land earmarked for the construction of schools and hospitals. The ‘forbidden money’ (pesa haram) that such sales produced was viewed locally as ‘cursed by the tears of those … who had suffered’, never capable of producing any further value.Footnote 4 Moral debates surrounding economic conversions, acts ‘in which valuables of a lower category are exchanged for or invested in valuables of a higher category’ (Guyer Reference Guyer2004: 28), often focus upon protecting of sources of reproduction – people, land, and animals.Footnote 5

Whilst these ideas are powerfully espoused by senior men, who proclaim their own virtue by retaining land in a theory of free moral agency. Through a discourse of negative obligation, they argue that they have ‘denied themselves’ the opportunity to live a life of short-term consumption in conscious embrace of longer-term obligations to the family. They find morality in ‘hanging on’ (Weiss Reference Weiss2022) to what they see as the values of their own fathers – of family and land. They argue they are virtuous through their knowledge of the potential ‘freedom to do otherwise’ (Walsh Reference Walsh2002), valorising their decision to place the virtue of familial obligation over and above the short-term possibilities of spending land money. They claim that one of their principal achievements is their self-restraint, because they feel they have resisted the temptation to ‘give up’ because of the unfavourable terms of the political economy. Labour, they argue, remains the proper means to wealth, not expropriating land.

Insofar as these ideas about the virtue of economisation – of converting money into school fees – and the immorality of consumption constitute the cornerstone of patrilineal kinship, these claims are being undermined by the economy of an impoverished Kiambu County. Livelihoods based upon piecemeal incomes gleaned from the informal economy mean that shortages of cash become small-scale disasters within household budgets, prompting families to look inward, at their own assets, and to consider sale. While men like Kimani insist upon the virtue of retaining land, these narratives barely conceal the extent to which his life is lived on the cusp of genuine hardship – that contingent misfortunes can easily force one into selling-off land to pay for vital costs, such as medical bills or school fees (Prince Reference Prince2023). Under such circumstances, ideas about the inherent immorality of land sale are being tested.

This chapter shows how some senior men who are forced to sell by contingent circumstances insist that they had no alternative. They defend land sale as a necessary act in order to create liquidity for other vital tasks. But in addition, this chapter looks at the experiences and perspectives of men with limited economic agency, who live their lives on the margins. Because when we shift our attention towards men who sell, and those who would like to consider doing so, we see the other side of a living argument about how to live in this world of shrinking plots of land and meagre job opportunities: appeals to constraint, to non-agency (Weiss Reference Weiss2015). Poor men describe themselves as destitute, lacking viable futures, and facing limited prospects for living up to the patrilineal ideal. These are men who embrace binge economies because joblessness, and land and cash shortages have already ground down their hopes for the future, as we saw in Chapter 2. They turn fire on those who would judge them, arguing that chasing virtue through fatherly responsibility looks like a fool’s errand, a futile pursuit of remembrance, when one’s kin will not remember you.

At the sharp end of economic uncertainty, therefore, narratives of patrilineal moral agency and the ethical dimension of economisation reach their limit. Men embrace short-term consumption as a logical response to an inability to ‘progress’ themselves in economic terms, feeling that there is little chance of a middle-class future. This chapter therefore shows the way rural poverty shaped the advance of Nairobi’s urban frontier. But it also points towards themes yet to fully emerge in the course of this book – especially the predicament of family members who lose out in these land sales, not least sons who feel their fathers are failing them, and fear for their own futures when ancestral land is sold.

Struggling for School Fees

It was late March 2018, and Kimani’s work had taken a turn for the worse. His lorry had broken down twice in quick succession, forcing him to call upon friends to provide him with loans of as much as 50,000 KSh to help pay for its repair (approximately 500 USD). The break-down had hit Kimani just as his work was beginning to return to normal following a long spell of disruption in the aftermath of the 2017 elections. Fear of ethnic violence had ground the economy to a halt, and businesses had closed, freezing commerce oriented around the transportation and sale of goods in Nairobi city centre.

Throughout 2017, Kimani regularly complained that money had become scarce (pesa imekosa), and he speculated that even after Kenya’s year of elections was over, the heavy rains of early 2018 had possibly extended the economic malaise.Footnote 6 With his father’s already inconsistent income in jeopardy, Mwaura knew that life at home would quickly become defined by scarcity. Whereas in times of abundance his mother Catherine could afford to shop regularly for meat and milk, stretches when Kimani went without work were usually marked by the repetitive meals of ugali and sukuma wiki harvested from the shamba.Footnote 7 But there were also more serious effects, as I found out when Kimani’s daughter Njoki was returned from her secondary (boarding) school in northern Kiambu in a state of tears after Kimani had failed ‘to find’ the money to pay for her school fees upon her return for the start of term in early April. While it only took Kimani a couple more days to come up with the money, the precarity of the family’s aspirations for their children’s futures was laid bare by the episode.

A few weeks later, I talked with Kimani about the incident. By then, Njoki was back at boarding school, and Mwaura in Kitui. Kimani had stopped home from the border for just a few days. As we began to talk, our conversation quickly turned to his own priorities and obligations as a father.

You see people like us … for example, I or my brother Mwangi. People from the neighbourhood normally say we have progressed a lot [tuko mbele sana] because of denying ourselves [kujinyima] things like those cigarettes, alcohol, bhang [cannabis], something called shisha that we use, and that is why at least [we are ahead] – not to praise ourselves [kujivuna] too much. Now God has helped me because I have returned to work. Now Njoki is heading back to school. But you see people from this area, in some houses if a child gets to standard eight [i.e., finishes primary school] that’s it [utaona mtoto akifika standard seven, baas]. He doesn’t continue with education. He searches for a construction job [anaenda kutafuta kazi ya kujenga nyumba] or something like that, because his mum and dad don’t have what? They don’t have enough money for him to continue with school [hawana nguvu ya pesa aendelee, lit. ‘the strength of money’]. Therefore, I give thanks to God because I have an income [ninaambia Mungu asante kwa sababu mimi nimepata]. Mwaura is finishing university, Njoki will go to university too because of denying myself that kind of fun of alcohol and what not. You know it finishes a lot of money [unajua inamaliza pesa sana].

I found it striking that not only did Kimani contrast his own fortunes with those from other families unable to send their children to secondary school, but he also described this as the consequence of his and his brother’s decision to deny themselves (kujinyima) the transient fun of alcohol and other indulgences. Kimani knew the fun (raha) of this other life all too well, having quit alcohol in the mid-2000s after his financial obligations to his son, an unwell wife, and his ageing mother forced him to become ‘serious’ (in Mwaura’s words), and he gave up alcohol for good. To quote Mwaura’s gloss on his father’s decision to give up alcohol, ‘He was hit by reality!’

Kimani went on, this time reflecting on his decision to postpone the construction of his stone house in order to fund his children’s education.

If you go to work and get 10,000, you keep it in the bank [ukienda kazi, ukipata 10,000, unaiweka kwa benk] because you know at the end of the month Mwaura needs 50,000, 60,000. Njoki needs to go back to school with 20,000, meaning you don’t want to do what [i.e., spend your money, a rhetorical question]? And that’s why you see this house? [Kimani gestured towards his unfinished stone house standing nearby] That’s why I am unable to move out from this house to go to that other one, because I feel if I move from this and go to the other house, that house will cost [lit. eat, kula] like 300,000. Now, if I spend that money Mwaura and Njoki might not continue studying, and that’s very bad [Sasa nikitumia hiyo Mwaura na Njoki waweza kukosa kusoma]. That’s why I took that position.

It was a matter of immense satisfaction to Kimani that his children were in school. Mwaura believed that what motivated his father was anticipated paternal pride – the satisfaction that would come from having a son who had finished university and progressed to paid work:

Their main purpose is to see me stable. They want to have that pride to say, ‘I took my child to school, he learned, he made me proud and now he’s doing this and this, he’s working somewhere, he has a family.’ I think that sense of I am stable, I think that is the satisfaction they want – being able to not rely on them anymore.

Mwaura’s university education, Kimani told me himself on one of his visits home, would allow him to ‘stand for himself’ (kujisimamia). While the expectation was that Mwaura would inherit a portion of his father’s land, along with his sister who would inherit a separate portion, an implicit hope was that Mwaura would find kazi, perhaps for the government or a business based in Nairobi.

These particular aspirations for Mwaura reflected the value placed upon education as a means to social mobility in Kenya. Neither Kimani nor any of his siblings attended secondary school, in contrast to some of their relatives descended from their father’s brothers. Since the colonial period, education has been not only a marker of status in central Kenya (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 398), but also, parents believe, a requisite for their children to lead better material lives than they did.Footnote 8 Now more achievable than ever, pursuing education for one’s children is just one of the manifestations of aspiration in a new Kenya where improved economic growth and foreign investment since the early 2000s has given rise to widespread hopes of living a ‘middle-class’ lifestyle. And although Kenya, like other countries in Africa and across the Global South (see, e.g., Mains Reference Mains2012; Masquelier Reference Masquelier2019), has seen an explosion in the number of graduates who expect to be able to find a government job only to be disappointed by their unemployment, the positive valuation of education as a worthwhile investment of time and money persists. However, there was no naïvety on the part of Mwaura, who knew all too well that it was ‘who’ one knew that would help him find a white-collar job, rather than his degree in commerce. A ‘connection’ was vital, and Mwaura pessimistically predicted that after graduation, it would be he rather than his father who returned to the family homestead to farm (Chapter 7).

Regardless of Mwaura’s real or imagined prospects, Kimani’s determination to educate his children contrasted sharply with the fates of most of Mwaura’s own age-mates. Mwaura was the only young man in the neighbourhood to attend university. Practically all of his peers ‘hustled’ for low wages in the peri-urban wage economy on construction sites, as matatu touts and tea-pickers. Mwaura was keenly aware of his father’s commitment to his future, one registered in guilt when it came to his studies, not least because of his astronomically high university fees at practically 55,000 KSh per term, the household’s single largest expense:Footnote 9

You know sometimes I think of my dad and, man, I feel sorry for him because we are like … We are sort of letting him down … in all aspects. I mean this guy is ever driving, day and night. And we are here [at university] and not studying hard enough.

When Kimani was at home, Mwaura commented how his father ‘could not see him idle’. When his father was home, Mwaura worked with him tending to the homestead – building a new shelter for the pigs or digging and planting on the shamba. As father and son, theirs was a relationship of emotional distance, but through Kimani’s toils raising money for his education, Mwaura saw the care his father expressed for his future.

The Obligations of the Father and the Freedom to Do Otherwise

In Kimani’s words, we heard one man’s perspective on what matters – what it was worth ‘struggling’ for (kũgeria). But his description of his own economic decisions in negative terms, and his emphasis on the immorality of neglect, reflected wider moral perspectives about the moral requirements of fatherhood within a wider landscape of masculine destitution: the need for self-discipline, to control desires for consumption, not simply of alcohol, but of the money that might otherwise produce good things.

Similar perspectives to Kimani’s circulated in Gĩkũyũ-language popular culture, not least in gospel songs oriented around the theme of labour’s morality. Consider, for instance, Kikuyu gospel singer Henry Waweru Karanja’s 2013 hit single, ‘I’ll never eat the sweat of another’.

Songs like Waweru’s that valorised wage labour could often be heard in public transport vehicles and in the pickup trucks that men drive transporting goods. They were particularly popular amongst Kimani’s generation of men and women, though younger men also enjoyed their aural aesthetic alongside a more eclectic variety of hip-hop from Nairobi sung in the Sheng creole or reggae music broadcast on the popular Ghetto Radio. Their lyrics were telling. While on the one hand, the ‘sweat of another’ in Waweru’s song implies a criminal livelihood or dependence on social others to find the cash to reproduce one’s household, it also implied the consumption of wealth meant for one’s children and their futures. Such songs recognised the choices men made to ‘do the right thing’, by refusing what might be understood as ‘easier’ modes of accumulating and spending wealth, thus living up to one’s values and claiming virtue in the process.

Waweru’s words, like Kimani’s, remind us of the changing nature of masculine obligations over the life course. Though all Kikuyu youths must move out of their mother’s house after initiation and into their own house, it is marriage (and often, shortly after, the arrival of children) that more clearly defines the beginning of a new type of responsible male adulthood (cf. Geissler and Prince Reference Geissler and Prince2010: 126–7), turning a ‘young man’ (mwanake) into an ‘adult’ or ‘married man’ (mũthuuri). Occasionally, this is referred to (in English) as a process of having become ‘serious’ in life (Cooper Reference Cooper2018). Usually this happens in a man’s mid to late twenties, and as we have seen, one of the problems Kiambu residents perceive is that jobless young men no longer appear willing or capable of sustaining marriages. By contrast, Kimani had not only long been married, but had two children who were both practically adults.

By this point in a man’s life, his father (or mother if a widow) would have set land aside for him to build his own house, possibly by sub-dividing it formally between children or by informally telling children where to build on land to which he holds title. It is this establishment of one’s own homestead or mũciĩ – a word that connotes both an affective notion of home and usually thought of as a free-standing house adjacent to one’s own garden (Dutto Reference Dutto1975: 177) – that begins a process of detachment from parents and siblings. Once a man inherits a portion of land and builds a house for a wife and child, it is establishing the particularity of his homestead that becomes a focus of his work. ‘Hustling’ becomes ‘a must’ (no muhaka) in light of the needs of dependents – particularly children in primary and secondary school. It is at this later stage of the life course that children’s success comes into view, and their success can be read as evidence of the time and labour their parents invest in them. This emphasis on children can also clarify what the affective import of the household or homestead really is: not a building, not a symbol of wealth, but the family lineage and its longevity through people (Shipton Reference Shipton2007; Sahlins Reference Sahlins2011). To produce it was framed as a matter of moral choice. To have one was a powerful means of distinction.

We have already seen how a labour ethic, wielded in discourse as a tool of moral chastisement, is used to police those cast as ‘lazy’ and valorise the conduct of men who work (Chapters 1 and 2). ‘As a man you must get up in the morning and do something to find money’, Catherine’s forty-five-year-old brother Philip once told me during the brief period in which he stayed with us as he explored work opportunities in Nairobi. These were languages of criticism, but also of self-praise – of lauding one’s own economic struggles as a facet of dutifully meeting obligations, especially to one’s family.

On the one hand, these perspectives on obligation reflect histories of labour migration that have shaped the emergence of provider masculinities across the continent. Naomi van Stapele (Reference van Stapele2021) has argued that a ‘provider identity’ emerged in Kenya during the colonial period, a product of the hut tax and its requirements of cash, a transformation that turned men out of the house in pursuit of ‘off-farm income’ (cf. Kitching Reference Kitching1980; Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992). I have already shown how similar transformations shaped masculine identities and moralities in Chapter 1. Further points of comparison can be glimpsed across the continent. Mark Hunter (2006) has shown in the case of South Africa that fatherhood has been reshaped by experiences of labour migration away from fathering per se, and towards provision (Mavungu Reference Mavungu2013).

However, if colonial economic reordering escalated the need for cash, the obligations underpinning its pursuit have deeper continuities that reside in ideas about the morality of reproduction and the virtue of creating wealth-in-people. In central Kenya, historian John Lonsdale’s classic essay on the origins of the Mau Mau rebellion, sub-titled Wealth, Poverty and Civic Virtue in Kikuyu Political Thought (Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992) underscored the responsibility of fathers to produce wealth for their successors. Kikuyu ‘fathers … worked for their sons’ (Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 334). A remembered ancestor was a mũtiga-irĩ na irĩirĩ, a ‘leaver of wealth and honour’, one who worked ‘for their children’s children’ (Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 338). Wealth implied not only well-tilled fields, but children, and ‘honour’ evoked the ‘upbringing’ children received in order to succeed on their own terms (see also Kinoti Reference Kinoti2010). In turn, responsible fatherhood was the condition for earning ‘civic virtue’ in the eyes of others – the social standing and public recognition of moral personhood that comes with fulfilling the normative expectations associated with one’s gender and age (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale and Falola2005: 564–5).

Such literature not only provides a point of comparison about the flow of wealth from fathers to children but also that such decisions to meet obligations were objectified as moral in so far as they were viewed as precisely that: choices, recognising that obligations are rarely mechanically met (Lambek Reference Lambek2008: 136). In the contemporary moment, anthropologists have written at length about the challenges men across Africa face in living up to ‘provider’ expectations. Daniel Jordan Smith (Reference Smith2017) has shown how men in Nigeria experience enormous anxiety about living up to them under conditions of cash scarcity. More recently, in Kenya, Mario Schmidt (Reference Schmidt2024) has described the challenges experienced by migrants in Nairobi who struggle with the expectations their partners place upon them to generate prosperity for their families.

However, what we see objectified by Kimani are the challenges of provision in a world not simply of lack, but where other tempting economic choices compete for one’s attention, not least the ‘fun’ (raha) of alcohol. The actions of ‘bad’ social others meant that Kimani framed his actions not as obligation but as a decision to control desires to consume that he otherwise might have. The decision itself is worth dwelling upon, since it recalls what Michael Lambek has described as ‘judgement’ (Reference Lambek2008: 136) – the decision to meet a particular type of commitment (Reference Lambek2008: 138–9). Kimani’s words evoke different transactional pathways with starkly different moral valences (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1992: 69). On the one hand, there was the proper wealth – as he saw it – of reproducing the household. On the other, there was the destruction of money by converting it into alcohol, its value consumed and thus destroyed (Munn Reference Munn1986). To stay on the right pathway required self-denial (kujinyima), since he saw all too well the temptations of the other path, its immediate promise of fun but its slippery slope towards destitution.

In central Kenya, this aspect of self-discipline, of moral choice to reproduce the household, also has longer continuities recognised through local concepts of agency. Older, married men were known then, as they are today, as athuuri, literally ‘those who choose’ (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 326). Kikuyu, Lonsdale tells us, possessed a rugged individualism, one that valued individual effort. It scorned poverty, a fool’s errand, not only because it destroyed one, but because it deprived a man of his legacy: his connection with the future through having kin survive him. Without such an underlying notion of agency, a man’s actions maintaining his household could not be interpreted as moral. Andrew Walsh’s useful formulation (Reference Walsh2002) captures precisely this understanding of possible alternatives that a morally valued type of responsibility assumes, of the ‘freedom’ people have ‘to do otherwise’: ‘[t]o be responsible for an act … one must have the option not to do it’ (Walsh Reference Walsh2002: 453).

These same issues of agency characterise fatherhood in Kiambu today. Sticking with the difficulty of work and not ‘giving up’ was a central aspect of Kimani’s identity, and a source of distinction from other men who – as he saw it – had succumbed to the temptations of alcohol. He always admonished me and Mwaura not to drink alcohol, associating it with the waste of precious money otherwise invested in the future.

To Leave a ‘Legacy’ Behind

Fatherly obligation expresses deeper ideas about the significance of the family’s continuity and the legacy one leaves behind in death. Yvan Droz’s (Reference Droz, Jindra and Noret2011: 77–9) writings on Kikuyu burial practices draw our attention to vital principles of patriarchal achievement – a good death and remembrance through ‘passing on’ wealth to the next generation. Burial at one’s homestead, on one’s ancestral land, is vital, an expression of male rootedness and belonging to the land. Being buried in public cemeteries remains a matter of great shame for Kikuyu men in contemporary Kenya (Droz Reference Droz, Jindra and Noret2011). Attachments to land express connections not only to the past but to the future, the morality of efforts to leave children generational wealth. Notions of ‘leaving behind wealth’ (gũtiga irĩ) remain as prominent in central Kenya today as they were in the pre-colonial period (Lonsdale Reference Lonsdale, Berman and Lonsdale1992: 334). Those who leave nothing to their children or, worse, have no children, die social deaths.

Consider, for instance, the eulogy of Watene, one of our neighbours in Ituura who died an untimely death from a heart attack at the age of fifty-one in late January 2018. Watene was a popular man in the neighbourhood. A taxi driver, and hardly a wealthy man, he was nevertheless seen to have supported his wife and four children more than adequately. Though he drank with his friends at local bars, he was not seen to have done so excessively, as with those such as Ikinya we met in Chapter 2. He projected his modest achievements through his generosity, and often bought beers for his friends and especially his young cousin Stevoh. His eulogy enshrined his career accomplishments, and that he and his wife had been blessed by four children. That his funeral was extremely well attended was a testament to his character.

Consider, by contrast, another man from Ituura known as Mguu. Mguu could be regularly found drunk at the local county Motel, usually on harsh spirits like Kenya Cane. He often sat aside from the tables of wealthier local men who drank bottles of Tusker and discussed politics at great length. In 2019, he died at the age of fifty-six, alone and without children. By the time of his death, he had sold much of his inherited land. Some of it he had directly exchanged for alcohol. Few attended his funeral. Mwaura saw his life as one of abject failure with an ignominious end. Mguu’s fate represents an extreme sort of social failure in Ituura, precisely the sort of destitution Kimani sought to avoid by ‘denying’ himself alcohol.

However, Kimani’s words evoke the decisions of other men whose livelihoods had allowed them to accumulate enough wealth to build ‘stone’ (mawe, cinderblock) houses but had not invested in their children’s education. In Kimani’s view, this desire to show off wealth contravened the moral project he himself had chosen to invest in: that of his son’s future. In Kimani’s eyes, provisioning for one’s children’s futures trumped the modicum of status gained in the eyes of others by possessing a stone house. The normative, moralising aspect of Kimani’s articulation of his personal values is on show here. His was a narrative that distracted from the poor state of his own house, one of justification that turned his own poverty into a virtue. That he did not have the prestige of wealth underscored his careful economisation, oriented towards others within his family and not himself. The choice to eschew projecting wealth reflects wider stereotypes about the visible appearance of middle-aged Kikuyu men in central Kenya – that they often dress in a simple shirt and suit trousers, rejecting contemporary fashions that might convey economic success more conspicuously. Mwaura joked that his uncle John dressed as though he was ‘going to get credit’, in other words, that he looked as though he had just stepped out of the house. Mwaura saw John’s humble appearance as characteristic of the stereotypical Kikuyu patriarch: a man more concerned with his homestead, his income, and his children’s futures than his appearance.

On Status and Control: Ways to Do Weekend Drinking

It was not only ‘wasted’ youth that one would find in the corners of the Motel getting drunk on Kenya Cane, but also tables of wealthier men from the neighbourhood who came together there at weekends. The Motel was busiest at weekends when it broadcast Premier League football on its solitary flat-screen television. Men from much further afield drove there in search of a context suitably removed from kin and friends who would recognise them. Such groups of men often drank bottles of Tusker, at 160 KSh, an indication of their comparative wealth. Some of them were wealthy enough to bring escorts. The visible act of drinking bottled beer created a powerful impression of economic success and capacity, one encoded in the accumulation of empty beer bottles, to ‘dirty the table’ (chafua meza), as this practice of conspicuous consumption is known. These were images of economic success that other men attempted to emulate, with rather reduced means. Poorer men tended to arrive there on foot from the local area. They drank cheaper, harder spirits in whatever quantities they could afford. Kenya Cane was the most popular, followed by Napoleon brandy and Legend whiskey.

However, the Motel was also frequented by local businessmen in their forties and fifties. These were hardly the sorts of social failures like those to whom Kimani contrasted himself. On the contrary, they were respected local men who were seen as having ‘made it’ – in other words, that they had reached a point in their lives where they had generated enough cash to enjoy themselves at the weekends. They were, in a sense, ‘hustlers’, in the language of contemporary Kenya – a word that identified a man who had become successful through hard work and clarity of mind, seizing economic opportunities that had come his way.Footnote 10 In many cases, they had also come into wealth through long journeys of economising that opened up subsequent opportunities, particularly through agri-business trends. One of them, Kinuthia made a small fortune buying quails and selling their eggs to distributors and local vendors. In 2018, he was living not in Ituura but in a nearby gated estate that had been built a stone’s throw from the neighbourhood, closer to Chungwa Town. Its fabulous middle-class stone houses had been built using the labour of local youth. In Mwaura’s words, Kinuthia was ‘too young to be that rich’.

‘They were where Kimani was like ten years ago. As you can imagine they are far much ahead!’, Mwaura told me as he looked over at the table of such a group of men at the Motel one weekend, their wealth made visible in the gradual accumulation of Tusker and Guinness bottles on the surface of the table in front of them. They drank with the owner of the Motel himself, who sometimes appeared there with much younger women of whom he was said to be a ‘sponsor’, in the current parlance of Kenya, in other words, maintaining a relationship in secret from his wife.

These men emphasised that constraint was an essential part of their success, that it allowed them to drink in the first place. Consider, for instance, another discussion I had at the Motel with Kinuthia’s brother, Adam, upon my return to Ituura in 2019. Like Kinuthia, Adam was a relatively successful local ‘hustler’ in his forties, though unlike his brother, he still lived in the neighbourhood. On one of these trips to the Motel, Adam began speaking to me at the bar after a few drinks. ‘Never spend more than you earn!’, he said, smiling. ‘Today I have earned 800 …’, he began. ‘I have spent 150 on food, and now 400 on alcohol, but you cannot spend more than you earn.’.

Sitting at the table alongside Adam was a local man who had recently sold land. Mwaura and I had tried to engage him in a discussion the previous week while eating nyama choma (grilled goat’s meat) at his butchery shop. He was loosely related to Mwaura, a descendant of his grandfather Gathee from his first wife. Earlier that month, the man had evaded our questions about his sale of land, insisting that since he had bought a plot elsewhere, he could not be afflicted by the ‘curse’ (kĩrumi) said to attach to, and kill, those who sell ancestral land. Mwaura doubted the man’s logic, ‘But it’s all Gathee’s land.’ Mwaura insisted that the curse still applied. He began impersonating the tone his father regularly took when describing such people: ‘Let me tell you Peter, it doesn’t make sense. How can you have sold land for 4 million, bought one acre elsewhere, and you’re drinking?’ As far as Mwaura was concerned, this man was consuming his inheritance to associate with men far wealthier than he really was. If young entrepreneurs performed their economic capacity, Mwaura suggested that men like Mguu degraded themselves by trying to live lives of consumption without the relevant means. He once told me a story about a young man in his thirties who had been successful in agri-business who visited the Motel, only for older men to beg him to buy them drinks. Mwaura saw in this a failure of the proper progression towards seniority and prestige through the accumulation of wealth that would facilitate hospitality to younger men and guests. ‘I mean, they should be buying for him!’, he said.

But Mwaura’s frustrations also manifested not only with the neighbourhood’s poor senior men, but with his own father. As his comment about Kimani’s lack of economic progress indicates, he believed that his father should have been more successful, facilitating not just his prospects, but his comfort and enjoyment in the present.

‘Man, is there any end to this shit work?,’ Mwaura asked me.

It was October 2017, and we were doing our usual chores at the weekend while Catherine remained at home with a chest infection. He and I walked the streets of Ituura, going house-to-house with buckets collecting animal feed for his pigs.

‘Why did you say that?,’ I asked him.

‘I mean, will there ever be a day when I don’t have to do this dirty work?’

‘And do what? Sell the land?,’ I ventured.

‘That’s one option,’ he shot back.

While Kimani remained absent on the Tanzanian border waiting for work, Mwaura remained poor and idle in Ituura, his frustration growing that his family were not able to access a higher standard of living. Mwaura compared his predicament to his peers at university from ‘working-class’ families, and palpably felt the gulf in lifestyles between them. ‘He’s broke!’, Mwaura often said of his father in late 2017. He tried to convince Kimani to abandon lorry driving for pig-rearing on their land, but his own experiments in that field regularly failed when his own pigs died from disease, the business plan coming to nothing. As 2017 wore on, and as the heavy rains arrived, Catherine’s health declined. Living in the small wooden house offered the family little in the way of warmth, and the house’s dirt floor flooded from time to time. Feeling alone, with his father now constantly away, yet complaining of being ‘broke’, it was little wonder that Mwaura might think of ways to relieve the stress on his family, even if it involved expropriating patrilineal wealth.

Drinking the Land

Kimani’s narrativisation of his obligations in a negative sense – that it was because of ‘denying’ himself alcohol that he met them – conjures up broader events afoot in Kiambu. By 2017, the topography of the county had already shifted rapidly from rural to peri-urban, spurred by new ring-roads constructed around the Nairobi perimeter. For Mwaura, his region of Kiambu was slowly becoming ‘more of Nairobi’.

As the city approached, land values increased, fomenting debate about the relative morality of selling land for a large, one-off amount of cash.Footnote 11 Kimani had an especially low opinion of fathers who sold their land, believing that those who did so only spent the proceeds on alcohol (njohi) and prostitutes (maraya). His perspective reflected broader discussion taking place in Ituura and Chungwa about the destitution land sale had brought upon the recent wave of self-expropriators. It was not long after my arrival in Ituura in January 2017 that I began to hear stories by members of my host family and their neighbours about the illness and poverty that afflicted neighbours who had sold inherited ‘ancestral’ land. Those who sold such family plots, so these stories went, ended up putting the proceeds to poor use, frittering away the finite quantity of cash they had acquired, before ultimately falling into destitution and an untimely death, leaving nothing to their children. This, it was said, was evidence that such people had broken irumi, statements against the sale of family land laid down by their deceased parents and ancestors. The example regularly used in such stories was the case of Ruaka town, just 10 kilometres away from Chungwa Town. Ituura residents claimed that it was there that men who had inherited land from their fathers had sold their plots to housing developers and – according to popular opinion – drunk the proceeds before drifting into lives of poverty and destitution. In the words of one of my interlocutors, ‘They died like dogs’. In short, they sold their homes. Reduced to a state of wandering alcoholism, so the stories go, many died young.

Debates about land sale reflect these same questions of economic responsibility but with heightened material and existential stakes. Of course, for some residents of Kiambu’s peri-urban corridor, the refusal ever to sell land was grounded in the existence of irumi issued by their fathers and grandfathers forbidding such sales. Kimani himself had seen the effects of the kĩrumi when his half-brother Kang’ethe (a son of his father’s first wife) had sold land in order to open a butchery in Chungwa Town. Kang’ethe was paid gradually by the new owner, and Kang’ethe grew accustomed to having an income. According to Kimani’s story, when the final payment was made, Kang’ethe realised he no longer had enough money to purchase the stock he needed to maintain his business. ‘The money was finished’ (zimeisha). Kang’ethe then took his own life.

According to what my father used to say, we fear something like that of passing on because it is his, the title deed is his.Footnote 12

The Gikuyu was seen to take effect either when issued (i.e., through the words of a parent saying ‘Never sell this land’) or when the issuer died (e.g., when the issuer says, ‘After I am dead, never sell this land’). When its rule was broken, it would begin to afflict the rule-breaker in question, usually leading to death in about a year.Footnote 13 This was not simply a type of curse that afflicted a person’s health, however. It was also described as affecting the quality of the money gained from the proceeds of land sale. Such money, people claimed, ‘can’t help you’ (citigagũteithia) and was unable ‘to bring blessings’ (kũrehe irathimo) that were furnished by ‘money you work for’.

On the surface at least, ideas about money that ‘can’t help you’ recall the work of Parker Shipton from his landmark book Bitter Money. Based on fieldwork carried out in western Kenya during the 1970s and 1980s, Shipton argued that the metaphor of ‘bitter money’ (Reference Shipton1989: 31) was used by his Luo interlocutors to refer to ill-gotten money, from the sale of ancestral land or the accumulation of wealth through selling homestead roosters. He argued that such transactions were akin to selling the household lineage, and thus understood to go against the grain of moral reproduction.Footnote 14 Shipton’s research primarily focused on how the money that emerged from such transactions possessed different qualities depending on how it was acquired (Shipton Reference Shipton1989: 10). Though seen as ‘cursed’, money from land sale was nonetheless thought to be very tempting to spend, described as ‘sweet’ (tamu) by my interlocutors (see also Schmidt Reference Schmidt2017, Reference Schmidt2020: 120). Kiambu men insisted that the money itself could not be physically touched because of this. Some advocated handing the proceeds over to a lawyer or accountant as a solution. Such money can thus be thought of as liquid ‘riches’ (Daswani Reference Daswani2016: 109–10), lacking the long-term associations latent in land, a durable store of wealth (Elliott Reference Elliott2022; cf. Parry and Bloch Reference Parry, Bloch, Parry and Bloch1989).

As we saw in Chapter 1, Kiambu men inherited plots from their fathers in the late colonial period, the introduction of freehold title deeds guaranteed individual ownership in the eyes of the state. The opportunity to realise land’s market value via sale has long existed, but nonetheless, Kiambu men continue to stress its inalienability (Weiner Reference Weiner1992). Land evoked not only affective ties with the past – its ‘genealogical’ significance (Shipton Reference Shipton1989: 30) – but also practical and pragmatic ideas about the material basis for social reproduction. As Tania Li (Reference Li2014b) has written, land’s ‘life-giving affordances’ make it an ‘awkward’ type of commodity, precisely because its alienation comes with severe consequences: homelessness, and disconnection from the very thing that stood to generate more value, and more property in the future (Strathern Reference Strathern1999: 162). Whether through the production of cash crops, animal husbandry, or now the construction of residential apartments with one’s own or borrowed capital, land in Kiambu continues to have a vital function as a generator of future value.

Amidst a land rush, desires to become rentiers, to replace one’s limited farmland with so-called ‘plots’, have become widespread, a new way of realising land’s value that allows one to benefit from urbanisation while retaining it. As Kimani himself noted, ‘Building isn’t bad … Isn’t it also a business? If someone rents out he can be getting money per month. Won’t he get a lot of money?’ (Kujenga sio mbaya … si ni biashara? Akodeshe apate pesa per month. Si atakuwa na pesa nyingi sana?). As attractive as such investments were, they also required ‘capital’ (a term used by interlocutors), and because of high interest rates attached to bank loans, most attempt to generate such capital by saving wages in the long term or letting land out. During fieldwork, Kimani began letting a piece of land at the edge of his shamba to a man who had constructed a kiosk, bringing in a small amount of rent (approximately 7,000 KSh per month), though this was small in relation to Mwaura’s astronomical university fees. If building plots did not break irumi, such curses were not about the use of the land for farming or its maintenance in a particular form. ‘Generational wealth’ now came in the form of plots, evoking a more ‘durable’ form of wealth. As Hannah Elliott (Reference Elliott2022) has shown, despite concerns about windfall cash generated from sales, its reinvestment in rental housing was lauded as the route to economic security.

However land’s value was realised, its retention was thought to guarantee the reproduction of the family, its material future. It is in this context that sale was seen as the ultimate act of fatherly neglect because it denied children their inheritance by destroying any potential value to be realised from it. ‘It doesn’t make sense’, Mwaura’s uncle Murigi would emphasise. Resisting the commodification of land was the flipside of keeping it within the tacit moral community of the family lineage.

Describing the nature of the curse, Kimani explained that his grandfather’s land ‘is meant to take care of [lit. ‘to grow’] his children and his great grandchildren, but not to be sold’ (ni ya kulea watoto wa watoto wa watoto wake, lakini isiuze). It was on this basis that Kimani judged those who sold land not only because of the threat of a curse, but because they used their proceeds irresponsibly, often with no thought to long-term familial concerns.

When you see many people here selling land, it’s just that someone decides to sell to get money, to go and drink alcohol or [do] other bad things.Footnote 15

Murigi, Kimani’s brother, would speak in similar terms about sale:

[Selling land can] kukosa [i.e., fail] to make the sense. [PL: Why?] Because, that shamba is to help your family. There is no need to sell the shamba and then go to rent. That money kuuza [to sell] the shamba, you are eating, you are drinking and then it’s finished. The people who are benefiting are the people who bought that land.

‘If you sell you are lazy’, Murigi continued, evoking once again a contrast between the work of adding value to one’s rural homestead by hustling for wages in Nairobi and destroying value through selling. He spoke to the domestic ethic underpinning his labour. He paused briefly to hail his daughter as ‘mum’, a common practice in central Kenya, evoking the responsibilities given to children to tend to the homestead, and that they are also named after the parents of their parents. Murigi asked her to pour some cai (tea) and then turned back to me. He recalled the instructions of his father, Gathee. ‘He said this land [Amesema hii shamba] is a nursery to this’, and gestured to his daughter. ‘So there’s no need to sell the shamba.’

Men like Kimani and Murigi rejected arguments about the rationality of land sale with recourse to stories about the destructiveness of the binges that land sellers would go on. In some ways, the destitution of vendors was seen as evidence of a kĩrumi at work. But it was also further evidence of the irresponsibility of vendors themselves: that they could not invest the proceeds from sale in land elsewhere, or in rental plots. Indeed, some men claimed that sale could be accepted but only on the condition that a new piece of land was purchased immediately. A ritual would then take place at the purchased homestead, merging the soil of one’s ancestral land with the new.

Ideas about the sensibility of investing in the land were therefore characterised less by cosmological attachments to an ancestral past than notions of responsible economisation towards the future. Droz showed through his research amongst Kikuyu communities in Laikipia in the 1990s how excessive land sale amounted to ‘the very picture of failure for a Kikuyu man’, an effect of ‘a lack of foresight or through an inordinate desire for money’ (Droz Reference Droz, Jindra and Noret2011: 78). In Ituura, older men like Ndovu would regularly talk about the money from such sales being literally drunk (kunywa pesa). Senior men emphasised their role as custodians, responsible for ensuring that ancestral land was maintained and passed on. The supposed ‘sweetness’ of the money connoted related desires to ‘get rich’ through selling it, deliberately voiding familial obligations for a life of consumption, often in the company of one’s peers. Controlling such desires was described as a function of restraint, self-denial, moral agency.

It is in this sense that maintenance of the land can be seen as a matter of masculine responsibility to ‘pass on’ wealth, to keep it within the family lineage (Abrahams Reference Abrahams2011) as a topic of an intensifying matter of moral concern, given the gradual encroachment of Nairobi. Changes to the law in Kenya have meant that in theory men are less capable of disposing of the land how they please – that land cannot be sold without it being gazetted, giving families time to appeal the process of sale. In practice, however, men continue to exert ownership and agency over their family land, often formally through having title deeds in their name. Men in their forties and fifties might not own title deeds, possessing only the informal word of their own fathers in their seventies and eighties that they will inherit. However, land sale is still eminently possible. Land is regularly sold surreptitiously, through backdoor channels via land brokers. The secrecy of such dealings often means that other relatives can exert very little agency over land sale. Left with the choice of either accepting the sale or pursuing protracted litigation to challenge sale, family members are often forced into the former.

That men are aware of such possibilities defined the way they articulated their conduct as a conscious embrace of the virtues of passing on land. Consider, for instance, the words of Ndovu, one of my oldest interlocutors at seventy-two, and an elder (mũthuuri wa kĩama) of the neighbourhood, when describing how his father subdivided his land between him and his children. According to Ndovu’s age, I estimate that this subdivision took place shortly after independence in 1963, by which time, land titles had been consolidated, and it is therefore likely his father was part of the first generation to have received a freehold title.

He told us, ‘Now, I want to give everyone their portion … And you should know it’s not that I don’t have a mouth to eat meat or to drink beer [i.e., he could have sold the land to finance such activities but was thoughtful]. Therefore, you all [i.e., his children], be very careful … This shamba is a small shamba, but it’s for your children. They shouldn’t go and rent in Chungwa when their father had a shamba – it’s very shameful.’Footnote 16

Ndovu’s recollection of his father’s words shows us the terms in which subdivision is viewed – not simply as paving the way for generations, but as an achievement in so far as the alternative possibility was avoided. His father’s reminder that he could have done otherwise served to underscore the understanding of a man’s agency that underpinned responsibility. Like Kimani, he claimed a degree of virtue for himself in meeting obligations to his children against the grain of the temptations of consumption. Ndovu’s words also evoked the sense in which responsibility itself is passed on through its own conduct. Rather than attachment to the land itself, Kimani often remarked upon his father’s refusal to sell land despite his status as a poor farmer. ‘My father was poor, but he never sold land, so why should I?’, he insisted. Not selling remained a matter of protecting a key asset, an act of economic morality, even if such a sale could generate enormous proceeds.

A Virtue of Necessity

Kimani’s self-praise underscored a degree of pride at having retained a life of land and labour under the unfavourable terms of an ailing rural economy. But as we have seen, a dividing line was emerging in Ituura between those who were able to build and those who were forced to sell. The empty shell of Kimani’s own stone house stood as a testament to his incapacity to ‘develop’ his plot. In this way, Kimani’s retention of land not only threw into relief his incapacity to build but also that he was hardly much better off than men who had been forced to sell through contingent circumstance.

Andrew Maina was a seventy-nine-year-old man from the neighbourhood. Like his brothers, he had inherited land from his father, who in turn had inherited it from his grandfather. In 2022, his land stood at 1.5 acres, but he had sold 0.5 acres in 2010 to pay for the untimely death of his first-born son in Sudan, where the latter had migrated for work. At short notice, he had been forced to raise 300,000 KSh in medical costs. He sold the land for 8 million KSh and used the remaining proceeds to purchase a further acre of land in Kirinyaga County, and three cows for dairy farming. He tacitly defended his decision by arguing that his wages would never have covered the medical bill. What’s more, he claimed to have provided for his children’s inheritance by distributing his land to them, both boys and girls. He also emphasised that he had ensured the curse could not affect him by mixing the soil from his ancestral land with the soil of his Kirinyaga plot.

His concerns about the curse had been raised by the fate of his two brothers, Paul and James, who had died in 2014 and 2016, respectively, after selling land. He drew a strong distinction between his fate and theirs, claiming that unlike him, they had failed to purchase another piece of land and therefore could not say they had made a good investment. What’s more, beyond the rental plots they built, he claimed the rest was used only for enjoying themselves, spending it upon ‘ahiki’, young unmarried women, a reference to sex workers. All of this, Andrew suggested, demonstrated their ‘ũkoroku wa mbeca’ (greed for money).

Andrew was conscious to emphasise that in his case, the norms of ‘passing on’ the land were being followed. He claimed that his sale of land, brought on by the contingency of economic misfortune, could be re-encompassed within the logic of kinship. He knew that others in the neighbourhood would talk about his decision to sell (andũ matiagaga kũaria – ‘people can’t fail to talk’). However, even with his avowedly legitimate investments, the rest of the 8 million remained strangely unaccounted for. Andrew conceded that he had ‘enjoyed’ (tũkĩrĩa, lit: ‘we ate’) the rest of the proceeds along with his much younger girlfriend, who was in her late thirties, with whom he had entered into a relationship after the death of his own wife. He referred to his girlfriend as a ‘gacungwa’ (lit. ‘little orange’), a Gĩkũyũ term often applied to mistresses of older men. Such women are often described as ‘gold diggers’ in misogynist discourse, seen to be interested in the wealth they can generate by entering into transactional relationships with older men. Andrew’s use of the word ‘eat’ to describe his enjoyment of the money is also telling, an admission that this money was consumed for enjoyment – not invested as the other proceeds were.

In the knowledge that others might judge him, Andrew tacitly defended his right to ‘enjoy’ life having reached a certain age, that it was what he had earned from working when he was younger and providing his children with an inheritance. In his view, as an old man, he had earned a retirement of sorts. His view can be compared with that of David, another landowner in Ituura and one of Kimani’s age mates. In contrast to other men from the neighbourhood, David insisted that his land was his own ‘business’ (biacara), that he could dispose of as he wished. He had done so, selling off a large portion of it, where an enormous mansion was being constructed next to his home in 2022. David had invested the proceeds in chicken farming and had constructed high-rise chicken coops next to his corrugated iron house. Instead of fathers being at risk of catching curses, he framed young men who clamoured for their parents’ land as worthy of getting a kĩrumi, especially if their demands contravened the decision of parents to sell. He insisted there had never been a curse on his land, even though others in the neighbourhood looked at the poor state of his home and his ailing farming business and claimed that it was the fault of the curse, that he was perpetually ‘broke’ and that despite his protestations, he had ‘wasted’ his birthright.

The Exhaustion of Patrilineal Virtue

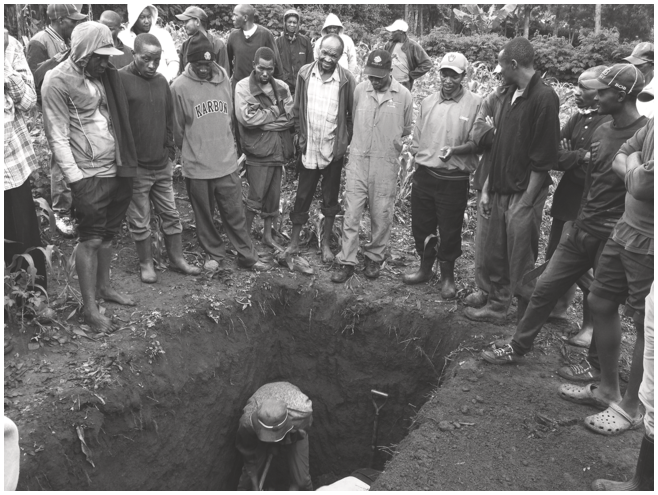

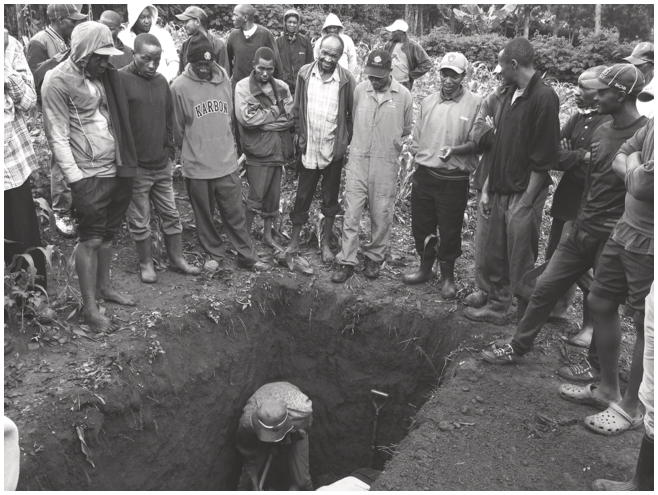

If, in 2018, Kimani could hang on to the vision of masculine obligation tethered to land, labour, and kinship, others from Ituura were exposed to difficulties such that wage labouring patriarchy itself began to look like a fool’s errand. Exhausted and hopeless, they narrativised their limited agency – not simply their vulnerability, but also their intention to ‘cash in’ upon their own hardships, to ‘give up’ on the virtue to be found from working for the future and to enjoy the possibilities of ‘drinking’ the land. In Chapter 2, we got a sense of this reversal of normative masculine discourse. Men from Ituura in their thirties rejected lives of responsibility in exchange for short-term consumption. At local grave-digging gatherings, men commented on this – creating counter-discourses that challenged hegemonic patrilineal morality, and that reflected the attitudes of those labelled ‘wasted’ men (Figure 3.1). Suddenly conspicuously present amongst the homesteads, these groups of poorer local men often arrived drunk, and talked raucously about their drinking exploits and what they claimed to be the pointlessness of pursuing a legacy through propping up a family.

Figure 3.1 A burial digging group

Figure 3.1Long description

In the drizzle of the rainy season, a group of poor men from Ituura have gathered to dig the grave of a neighbour in the field belonging to the neighbour's homestead. They watch the two men below them digging the hole with shovels. Some are wearing overalls, and others, Wellington boots. Most are dressed in dirty clothes favoured by labourers and farm workers. The earth below them is dark in the rain, and the grave is already deep.

In late March 2018, a forty-nine-year-old man called Daniel from a neighbouring family was killed in a car accident on a nearby road, having stumbled into traffic, drunk in the middle of the night. As was customary in neighbourhoods like ours – comprising households that relate through more concrete notions of patrilineal descent as well as looser ones of cousinage – Mwaura and I attended the grave-digging (kwenja irima) the day before his burial on Daniel’s father’s plot of land. Like other such gatherings I attended in Ituura, it was an all-male affair, a display of mutual assistance between households through volunteering their younger kin to the party in need.

The atmosphere on the rainy March morning was, however, not sombre, but full of wise-cracks, stories, and gossip. Men stood around the deepening grave chatting and smoking cigarettes, as those doing the digging rotated in and out of the empty grave, shovelling earth out and onto the surface of flattened maize plants.

As one might expect, the death of a man did eventually bring forth reflections on the transience of life. One of the neighbourhood men, Chege, a successful man in his early thirties with an office job in Kiambu, took it upon himself to advise his age-mates to enjoy their lives in the present. Dressed in overalls, shovelling earth as he spoke, Chege reminded those present about the perils of oblivion, and the thankless task of family patriarchs. ‘Instead of keeping money in the bank, it’s better to kick it [i.e., money] around with prostitutes, drinking [it] alcohol instead of leaving it behind to people. They will spend it [lit. eat it] without thinking!’ (Handũ ha kũiga mbia cia kũbengi-rĩ, kaba gũcihũranga mateke na maraya, ugĩgĩcinyuaga njohi handũ ha gũtigĩra andũ. Magũcirĩa mategwĩciria). The implication was clear: working as hard as patriarchal figures like Kimani was a fool’s errand since in contemporary Kiambu, one’s legacy was all too quickly forgotten.

Another youth could only agree. Echoing typically misogynistic discourses that describe Kiambu women as money-oriented, he argued that: ‘By the third day of mourning there’s a [new] guy in the house guarding the property’ [lit. ‘taking care of things’, i.e. sleeping with the wife of the deceased] (Na mũthenya wa gatatũ wa macakaya-rĩ, hena kanda nyũmba ĩkarangĩra marĩ). Perspectives such as this argue that even close family cannot be trusted with one’s wealth, and neither is it unique to Chege. Stories circulate in Kiambu about wives that have murdered husbands in order to seize control of their assets, whether land or cars. Many younger men in Ituura and Chungwa Town perceived women as money-oriented, a perception that indexes a concern that even close kin cannot be trusted (Chapter 5).

Many of the men present did of course have families of their own and took part in these discourses from the perspective of bitter irony, making fun of their own errands as men trying to raise cash for their wives and children. But as a discourse, Chege’s words evoke a tendency amongst men to feel that, in a self-interested world where others are generating wealth quickly and spending it on themselves, obligation has a diminished moral significance. A self-interested worldview attributed to others provided the basis of one’s own self-interested reasoning. If even family can forget you, negating one’s efforts in life to sustain it, what else is there to do but embrace the temporary but nonetheless compelling fun of alcohol? Consider Mwaura’s take on the trend towards land sale:

In my view, I think it’s happening, because that’s why I think many people are selling their land and just drinking the money. Because when you look at some people who have sold their land they haven’t done it for a specific reason like something that makes sense. They’re just doing it because they want money to make their lives more comfortable than they are. So I think that’s why they’re doing, because they think their families aren’t worth being left the land so they think they’ll also sell the land.

Questioning Mwaura about such attitudes the day after the burial, he shed doubts on his own father’s legacy. ‘If Paul Kimani dies, we’ll mourn him like a month then continue with our lives, maybe sell his truck, maybe sell his land.’ Was that what he really thought? I pushed him to commit to what he had said. He back-tracked. ‘I’m just saying.’ And what about the dangers of selling the land? Mwaura shook himself, recanting quickly, ‘I can’t support that motion.’

Conclusion

Narratives of ‘self-denial’ and ‘struggle’ espoused by senior men like Kimani show us that senior men lived their lives of obligation in the knowledge that they could avoid it by selling land. They turned their struggles into a narrative of their own virtue, reiterating the principles of patrilineal kinship against the backdrop of the irresponsible consumption land sale was taken to be. But under conditions of poverty, the possibility of remembrance, and of social continuity in kin were becoming increasingly uncertain. A nagging feeling was emerging that ‘ungrateful’ women were waiting in the wings to expropriate one’s legacy (Chapter 6). Younger men argued that selling land and embracing alcohol drinking was a rational response to an economy of limited opportunities for becoming economically ‘stable’. Others considered embracing the ‘sweetness’ of land sale money, given that they were already alcoholics, spending their earnings on Kenya Cane. ‘We are not going to last much longer,’ the logic went. The sense that the gap between economic means and moral ends was too great meant that the virtue of ‘struggle’ could no longer be maintained, especially when pressures on providing a good life for one’s family were higher than ever. Land sale constituted a knowing relief from peri-urban poverty, albeit time-limited by finite proceeds.

This chapter has illuminated the way Nairobi’s urban frontier is shaping material conditions, economic ideologies, and moral thought oriented around social reproduction amongst Kiambu’s poor smallholders (compare, e.g., Weiss Reference Weiss2022; cf. Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1987; Bear et al. Reference Bear, Ho, Tsing and Yanagisako2015; Hann Reference Hann2018). Anthropologists have shown that under contemporary capitalism in Africa – especially the crisis of ‘surplus people’ (Li Reference Li2010) – the material possibilities for realising dominant modes of self-accomplishment have been thoroughly undermined, producing wide-scale unemployment, hopelessness, and boredom (see, e.g., Honwana Reference Honwana2012; Mains Reference Mains2012; Masquelier Reference Masquelier2019). For landed families in an urbanising central Kenya, the product of such destitution is not only youth ‘waithood’, as in so many other contexts, but modes of self-expropriation – the desire to ‘eat’ into one’s own land reserves in order to live lives of consumption defined by the feeling that short-term enjoyment is all that remains. Work as a virtue remains tethered to the pursuit of the patrilineal moral order: social reproduction through generating ‘off-farm income’ (Kitching Reference Kitching1980: 3), reinvested in the homestead. Conceptualised through a form of denial rather than endurance, such discourse suggests that ‘binge economies’ of land sale represent not only their inversion (Day, Papataxiarchis, and Stewart Reference Day, Papataxiarchis, Stewart, Day, Papataxiarchis and Stewart1999; Wilk Reference Wilk2014), but their future, as ‘hanging on’ to the patrilineal ideal becomes ever more difficult under conditions of land poverty and joblessness. Amidst Kiambu’s economy of collapsing peasant livelihoods, where an urbanising frontier brings new opportunities for fast wealth into view, pathways to masculine self-accomplishment meet their material limits. A labour theory of virtue was failing as a way of making economic life meaningful, giving way to a knowingly destructive short-termism, the only possible option that some men felt was left available to them.

Even senior men fell afoul of their labour theory, so espoused. As we have already seen, in 2022, Kimani broke his own word and sold part of his inherited land for 3.5 million KSh, a large part of Mwaura’s future inheritance. On the surface, Kimani seemed to have been forced into sale by his debts. But revelations emerged that he had used a portion of the proceeds to fund a lavish lifestyle for his new wife, indulging in the very consumption he had once condemned. Mwaura’s words at the end of the chapter evoked the escape route sale offered towards living a different life—to generate liquidity and access a new capacity to spend, to put paid to ‘dirty work’. In 2017, Mwaura had not envisioned that it was his father who would sell the land.

By 2022, Mwaura, disillusioned and feeling betrayed, reflected on the hollowness of patrilineal kinship’s moral economy, condemning the ‘selfishness’ he saw as characteristic of older men. He realised that the economic landscape was shifting beneath his feet, leaving the younger generation to navigate a future path fraught with challenges, often without parental support (Chapter 7). As Mwaura looked toward the future, one without Catherine’s support after her death in 2020, he pondered how he would create his own family legacy and moral integrity through work that seemed elusive and precarious. While his parents had been his providers, adulthood approached, and this struggle for ‘stability’ would define the next years of his life.