1. Introduction

Garnet is a relatively rare phase in silicic volcanic rocks worldwide (Harangi et al. Reference Harangi, Downes, Kósa, Szabo, Thirlwall, Mason and Mattey2001). It typically crystallizes in peraluminous, corundum-normative volcanic rocks, where its origin is attributed to the partial melting of metasedimentary sources (i.e. S-type magmas) under middle to lower crustal pressures (4–7 kbar) (Clemens & Wall, Reference Clemens and Wall1984; Gilbert & Rogers, Reference Gilbert and Rogers1989; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Zhang, Santosh, Zhao and Chen2017; Sieck et al. Reference Sieck, López-Doncel, Dávila-Harris, Aguillón-Robles, Wemmer and Maury2019; Cravinho et al. Reference Cravinho, Rosa, Relvas, Solá, Pereira, Paquette, Borba, Tassinari, Chew, Drakou, Breiter and Araújo2024). In such magmas, garnets are generally poor in CaO and MnO and coexist with phenocrysts of quartz, biotite, feldspars, occasional cordierite and enclaves or xenocrysts derived from metamorphic rocks (Hamer & Moyes, Reference Hamer and Moyes1982; Clemens & Wall, Reference Clemens and Wall1984; Gilbert & Rogers, Reference Gilbert and Rogers1989). In contrast, garnet may also crystallize in metaluminous andesitic to dacitic volcanic rocks sourced from partial melting of igneous protoliths (i.e. I-type rocks), typically under lower crustal to upper mantle conditions. These garnets in I-type rocks are distinguished by higher CaO contents (>4.0 wt%) and are associated with hornblende, clinopyroxene, orthopyroxene, plagioclase and quartz (Day et al. Reference Day, Green and Smith1992; Harangi et al. Reference Harangi, Downes, Kósa, Szabo, Thirlwall, Mason and Mattey2001; Kawabata & Takafuji, Reference Kawabata and Takafuji2005; Bach et al. Reference Bach, Smith and Malpas2012; Bouloton, Reference Bouloton2021).

The rarity of garnet in silicic volcanic rocks is largely due to its limited stability at low pressures and its preference for deep crustal crystallization (Green & Ringwood, Reference Green and Ringwood1968; Clemens & Wall, Reference Clemens and Wall1984). Its preservation in silicic volcanic rocks requires both a thickened crust, which is typically related to orogenic or compressional regimes, and rapid magma ascent to prevent resorption during decompression (Harangi et al. Reference Harangi, Downes, Kósa, Szabo, Thirlwall, Mason and Mattey2001). Consequently, most garnet-bearing silicic volcanic rocks occur in tectonic settings undergoing a transition from regional compression to post-orogenic extension, often overlying folded sequences unconformably (Clemens & Wall, Reference Clemens and Wall1984; Gilbert & Rogers, Reference Gilbert and Rogers1989; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Zhang, Santosh, Zhao and Chen2017; Coira et al. Reference Coira, Kay, Viramonte, Kay and Galli2018; Sieck et al. Reference Sieck, López-Doncel, Dávila-Harris, Aguillón-Robles, Wemmer and Maury2019). Thus, garnet in silicic volcanic rocks serves as a valuable indicator for magma composition, source conditions and tracking regional tectonic evolution (Kawabata & Takafuji, Reference Kawabata and Takafuji2005; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Schieber and Basu2009; Caffe et al. Reference Caffe, Trumbull and Siebel2012; Coira et al. Reference Coira, Kay, Viramonte, Kay and Galli2018; Bouloton, Reference Bouloton2021).

In this study, we report garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks associated with the Neoproterozoic Fuchuan ophiolite complex (FOC) in the eastern Jiangnan Orogen (JO), Southeast China. This rare occurrence provides key constraints on the Neoproterozoic tectonic evolution of the region.

2. Geologic background

The South China Block comprises the northern Yangtze Craton and the southern Cathaysia Block (Figure 1; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Wang, Qiu, O’Reilly, Xu, Liu and Zhang2007), which are separated by the Neoproterozoic JO (Figure 1a). In its eastern segment, the JO is divided by the NE Jiangxi Fault into the northwest Jiuling Terrane and the southeast Shuangxiwu Island-arc Terrane (Figure 1b; Shu & Charvet, Reference Shu and Charvet1996). Neoproterozoic strata in both terranes consist of a metamorphic basement sequence unconformably overlain by a sedimentary cover (Figure 1b, Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Wang, Qiu, O’Reilly, Xu, Liu and Zhang2007; Yang & Wang, Reference Yang and Wang2020). This regional unconformity, along with widespread (∼830–820 Ma) post-orogenic S-type granitic plutons (Figure 1b), marks the Jinning Orogeny, during which the Yangtze and Cathaysia blocks were amalgamated (Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cawood, Shu and Zhao2019).

Figure 1. Geological sketch maps show the Jiangnan Orogen (JO) in South China. (a) Tectonic framework of the South China Block; (b) schematic map showing the main distribution area of Neoproterozoic rocks and major deep faults in the JO (modified after Xia et al. Reference Xia, Xu, Niu and Liu2018). NCC: North China Craton, QL–DB Belt: Qinling–Dabie orogenic belt. The numbers in the yellow circles represent outcrops of bimodal volcanic rocks: 1 Meiling and Huangshan (∼860–840 Ma, Lyu et al. Reference Lyu, Li, Wang, Pang, Cheng and Li2017); 2 Qimen (∼830 Ma, Li et al. Reference Li, Lin, Xing, Davis, Jiang, Davis and Zhang2016); 3 Zhenzhushan (∼850 Ma, Li et al. Reference Li, Li and Li2010) and 4 Lushan (∼830 Ma, Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Li, Wang, Li and Pang2020).

In the Jiuling Terrane, the basement is dominated by ∼860–820 Ma greenschist-facies meta-volcano-sedimentary rocks, such as the Xikou and Shuangqiaoshan groups (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Zhao, Yu, Qiu and Xing2014). In contrast, the basement of the Shuangxiwu Island-arc Terrane consists of ∼970–860 Ma volcanic and intrusive rocks (Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Li, Lo, Wang, Ye and Yang2009), which are characterized by highly depleted Nd–Hf isotopic signatures and the lack of inherited zircons, indicating an intra-oceanic arc setting (Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Li, Lo, Wang, Ye and Yang2009; Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cawood, Shu and Zhao2019).

As one of two known Neoproterozoic ophiolites, the FOC extends discontinuously for ∼50 km along the NE Jiangxi Fault (Figure 1b, Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Hb, Yang and Wang1989). It occurs as a series of fault-bounded blocks composed of diverse lithologies, which are embedded within highly sheared flysch-like sediments of the Xikou Group (Figure 2). Several post-orogenic, strongly peraluminous granitic plutons (∼830–820 Ma), including the Shexian, Xucun and Xiuning plutons, intrude the folded Xikou Group or FOC (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Zheng, Wu, Zhao, Zhang, Liu and Wu2006).

Figure 2. Geological map of the Fuchuan ophiolite complex (FOC) in eastern JO.

Stratigraphically, the FOC can be divided into mantle and crustal units (Figure 2). The mantle unit comprises serpentinite, minor gabbro and rare pyroxenite (Figure 3a–b), whereas the crustal unit consists of pillow lava, deformed garnet-bearing dacitic ignimbrite, tuff and rare diorite (Figure 3c–d). The garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks occur as detached blocks spanning several square kilometres, partially in fault contact with the pillow lavas.

Figure 3. Field photographs of (a–b) mantle unit and (c–d) crustal unit of the FOC. (a) Serpentinite and gabbros; (b) pyroxenite; (c) pillow lava; (d) deformed garnet-bearing dactic ignimbrite.

3. Sampling and analytical methods

Ten garnet-bearing dacitic ignimbrites and tuffs were collected for whole-rock geochemical and Nd isotopic analyses, which were performed at Nanjing University. Sample locations are indicated by black stars in Figure 2. Electron probe microanalysis of garnet and backscattered electron (BSE) imaging were carried out at the Nanjing Center, China Geological Survey.

Zircon grains separated from ignimbrite sample XN02 were analyzed for in situ U-Pb geochronology and trace elements by laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry at Hefei University of Technology. Subsequent zircon Hf isotopic analyses were performed at NJU using a Thermo Scientific Neptune Plus MC-ICP-MS coupled with a New Wave UP193 solid-state laser ablation system. Detailed analytical procedures are provided in Supplementary File 1.

4. Results

4.a. Petrographic characteristics

Garnet-bearing dacitic tuff and ignimbrite are moderately to strongly deformed, containing less than 15 vol.% crystal fragments (mostly 500–2000 μm) and 20–30 vol.% glassy shards. Crystal fragments are dominated by alkali feldspar, plagioclase and quartz, with minor biotite and garnet (Figure 4), where feldspar fragments are commonly argillized, displaying cloudy surfaces (Figure 4c–d). Biotite crystal fragments are extensively altered into the mixture of chlorite, oxides and clay minerals, but rare grains enclosed in feldspar still show the pseudomorphic shape (Figure 4c). Detailed garnet textures are described in the following section.

Figure 4. Petrographic characteristics of garnet-bearing dacitic (a–b) tuff and (c–d) ignimbrite. Note that the fractured garnet fragment in (a) retain their euhedral outline. Garnets and alkaline feldspar in (d) are simultaneously deformed along the foliation. Afs, alkali feldspar; Bt, biotite; Chl, chlorite; Grt, garnet; Qz, quartz.

Accessory minerals include apatite, ilmenite, titanite and zircon. Apatite and ilmenite occur as inclusions within garnet and alkali feldspar, as well as isolated grains in the matrix. In contrast, zircon and titanite are found predominantly as isolated matrix grains.

4.b. Texture and composition of garnets

Garnet fragments constitute 2–5 vol.% of the samples and mostly range from 100 to 2000 μm in size (Figure 5). They occur as angular to subangular grains scattered in the volcanic matrix, or sheared to discrete subgrains along the foliation (Figures 4a, 5a). No garnet inclusions are observed in the rock-forming mineral phase. Larger garnet fragments are typically fractured, with fractures filled with chlorite, clay minerals and micro-garnet remnants (Figures 4a, 5b). In BSE images, garnets show no apparent zoning or reacted rims and lack metamorphic mineral inclusions (e.g. sillimanite, muscovite), but rarely contain inclusions of ilmenite, apatite and melt (Figure 5c–d).

Figure 5. BSE images of representative garnet crystals in the dacitic volcanic rocks from the FOC. (a) Garnet (Grt) grains are elongated and subgrain-banded due to shearing. (b) Fractured garnet crystals displaying cracks filled with chlorite (Chl). (c) Garnet crystal coexists with alkali feldspar (Afs) and contains ilmenite (Ilm) and apatite (Ap) inclusions. (d) A small euhedral garnet crystal contains melt inclusions. White spots in BSE images denote the locations of the electron probe microanalysis analyses.

Major element compositions of the garnets are given in Supplementary Table S1. The garnet fragments are primarily composed of almandine (Fe2Al2Si3O12, 59–76%) and pyrope (Mg2Al2Si3O12, 17–39%), with minor grossular (CaO3Al2Si3O12, 0–6%) and spessartine (Mn2Al2Si3O12, 1–6%) components. Their MnO, CaO and MgO contents range from 0.3 to 2.6 wt%, 0.5 to 2.5 wt%, and 4.0 to 9.6 wt%, respectively. Concentrations of Cr and Ni contents are generally lower than 1.0 wt%. TiO2 contents are less than 0.2 wt%. No systematic compositional variations are observed among garnet fragments of different sizes or occurrences. The limited composition variations suggest that any growth zoning, if present, could be too weak to be resolved, consistent with the lack of visible zoning in BSE images.

4.c. Zircon U-Pb dating results and Lu-Hf isotope composition

The zircon U-Pb isotopes, geochemical compositions and calculated Ti-in-zircon temperatures are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Based on zircon U-Pb age and texture, the zircon grains separated from XN02 can be divided into two groups:

Group 1 zircon crystals are euhedral and generally show concentric to oscillatory zoning in cathodoluminescence (CL) images (Figure 6), consistent with magmatic origin. Some of these zircon grains are surrounded by narrow rims (mostly <10 μm in width), which are bright and homogeneous and may have been generated during regional greenschist-facies metamorphism (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Zhao, Yu, Qiu and Xing2014). Twenty-four spots analyzed on cores of Group 1 zircon crystals yield concordant 206Pb/238U ages of 827–852 Ma and a weighted mean age of 839 ± 3 Ma (MSWD = 0.26; Figure 7a). This age is consistent with that of gabbros in FOC (842–825 Ma; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wu and Zheng2012, Reference Zhang, Santosh, Zou, Li and Huang2013; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Wang, Qi, Zhang, Wang, Li and Shu2018a; Hong et al. Reference Hong, Yu, Song, Chu, Liu and Zhou2022), interpreted as the crystallization age of the garnet-bearing volcanic rocks.

Figure 6. Representative CL images of zircon crystals from the garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks. Complex internal zoning in Group 2 zircons is outlined by white dashed lines.

Figure 7. (a) Concordia and U-Pb age vs. ϵHf(t) (b) diagrams for zircons from garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks and coexisting rocks in the eastern JO. The zircon ϵHf(t) data from coeval silicic intrusion associated with FCO are from Shu et al. (Reference Shu, Wang and Yao2019). The zircon ϵHf(t) data of mafic intrusions of the FCO are from Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Wu and Zheng2012) and Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Santosh, Zou, Li and Huang2013). Detrital zircon ϵHf(t) data of the Xikou Group (South Anhui) are from Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Zhao, Yu, Qiu and Xing2014), whereas those for Shuangxiwu arc volcanic rocks are from Li et al. (Reference Li, Li and Li2010).

Geochemically, Group 1 zircon crystals have high Th/U (0.06–2.85) and variable Ti (3.1–47.1) contents. Their crystallization temperatures, calculated using αTiO2 = 0.6 and the model of Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Watson and Aikman2007), range from 687 to 960°C, with 16 analyses below 800°C. The 176Hf/177Hf ratios of Group 1 zircons are highly variable (0.281848–0.282651, n = 24), corresponding to ϵHf(t) values from -9.1 to 13.7 (Figure 7b). These ϵHf(t) values overlap with those of coeval felsic intrusions in the Fuchuan region and coeval detrital zircons from the Xikou Group (Figure 7b).

The Group 2 zircon crystals generally exhibit more complex internal textures in CL images, characterized by oscillatory-zoned cores mantled by successive zones of contrasting brightness (Figure 6). Thirteen analyses of their cores yielded two 206Pb/238U age groups: 877–973 Ma (n = 8) and 1013–1780 Ma (n = 5), significantly older than Group 1 zircons. These grains are therefore interpreted as inherited zircons or xenocrysts derived from magma sources or wall rocks.

4.d. Whole-rock geochemistry and Nd isotopic composition

Whole-rock major and trace element compositions are given in Supplementary Table S4. The garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks are slightly peraluminous, with Al2O3/(Na2O + K2O + CaO) molar ratios ranging from 0.99 to 1.21 (Figure 8), comparable to those of coeval silicic volcanic rocks in the eastern JO or the garnet-bearing silicic volcanic rocks worldwide (e.g. Clemens and Wall, Reference Clemens and Wall1984, Reference Clemens and Wall1988; Harangi et al. Reference Harangi, Downes, Kósa, Szabo, Thirlwall, Mason and Mattey2001; Sieck et al. Reference Sieck, López-Doncel, Dávila-Harris, Aguillón-Robles, Wemmer and Maury2019). In the SiO2–K2O diagram, they fall in the medium- to high-K calc-alkaline fields (Figure 9a). Their SiO2, Al2O3 and MgO contents show limited variations, with ranges of 66.2–70.5 wt%, 14.9–16.6 wt% and 1.78–2.75 wt%, respectively (anhydrous basis), and display no systematic variation trends among them (Figure 9b–c). FeOt and TiO2 contents range from 4.33 to 6.45 wt% and 0.55 to 0.84 wt%, respectively, similar or slightly higher than those of coexisting pillow lavas (Figure 9d–e).

Figure 8. Molar Al2O3/(CaO + Na2O + K2O) vs. molar Al2O3/(Na2O + K2O) diagram for garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks and coeval silicic volcanic rocks in the eastern JO. The data of coeval (∼860–830 Ma) silicic volcanic are from Li et al. (Reference Li, Li and Li2010), Zhou et al. (Reference Zhou, Zhang, Liao, Yu, Chen, Zhao, Jiang and Jiang2012), Li et al. (Reference Li, Lin, Xing, Davis, Jiang, Davis and Zhang2016), Lyu et al. (Reference Lyu, Li, Wang, Pang, Cheng and Li2017) and Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Li, Wang, Li and Pang2020).

Figure 9. (a–e) Harker diagrams of garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks and related rocks in the FOC and (f) whole-rock SiO2 histogram of ∼860–830 Ma volcanic rocks in the eastern JO. The boundaries in K2O vs. SiO2 (a) follow Peccerillo & Taylor (Reference Peccerillo and Taylor1976). Diagrams (a–e) include garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks, published data of pillow lavas from the FOC (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wu and Zheng2012; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Santosh, Zou, Li and Huang2013; Zhao & Aismow, Reference Zhao and Asimow2014; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Wang, Qi, Zhang, Wang, Li and Shu2018a), and post-orogenic S-type granite in the eastern JO (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Zheng, Wu, Zhao, Zhang, Liu and Wu2006). Diagram (f) additionally incorporates data of coeval volcanic rocks from the eastern JO, with data sources same as in Figure 8. The whole-rock data were recalculated to anhydrous and only weakly altered samples with loss on ignition < 6.0 are plotted.

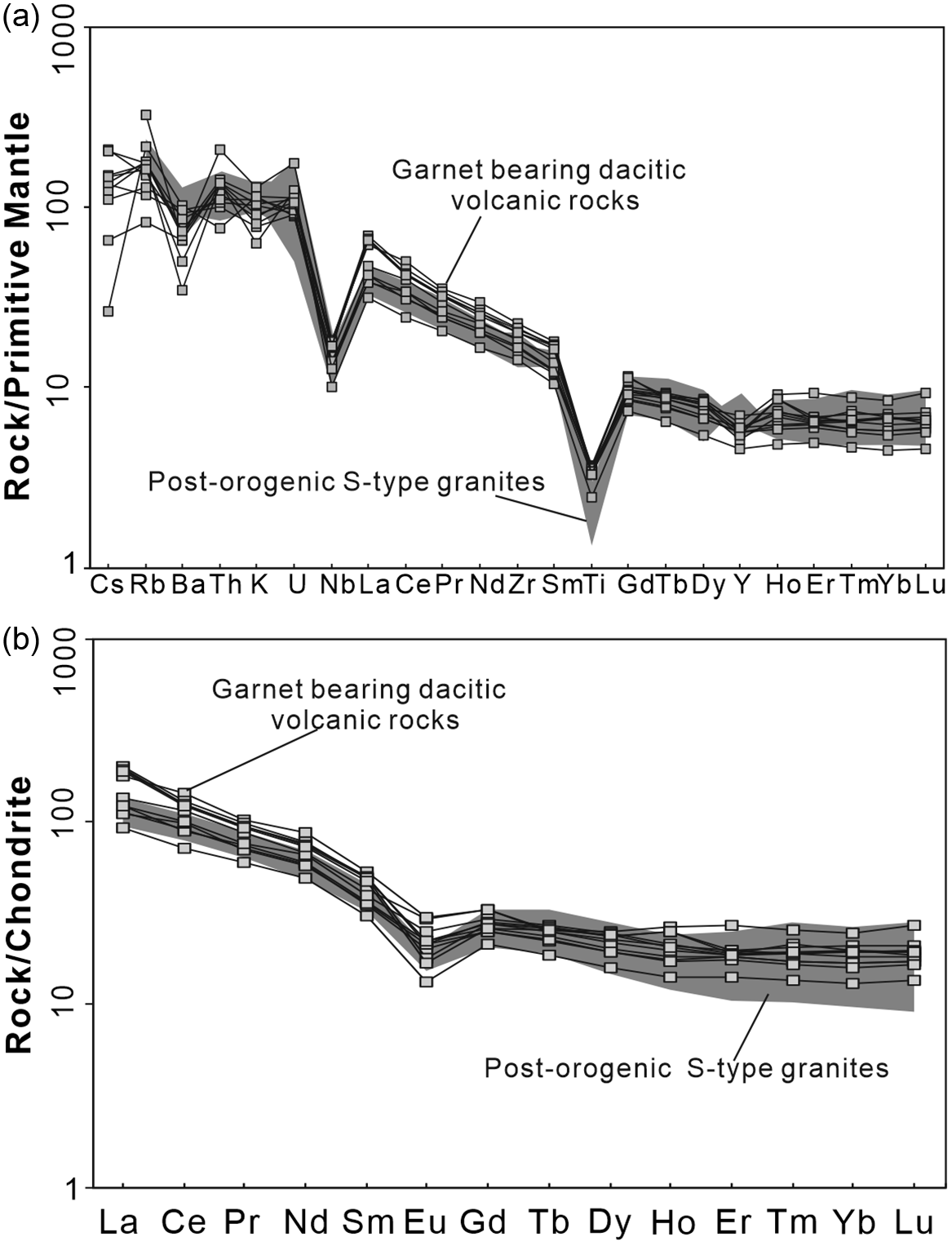

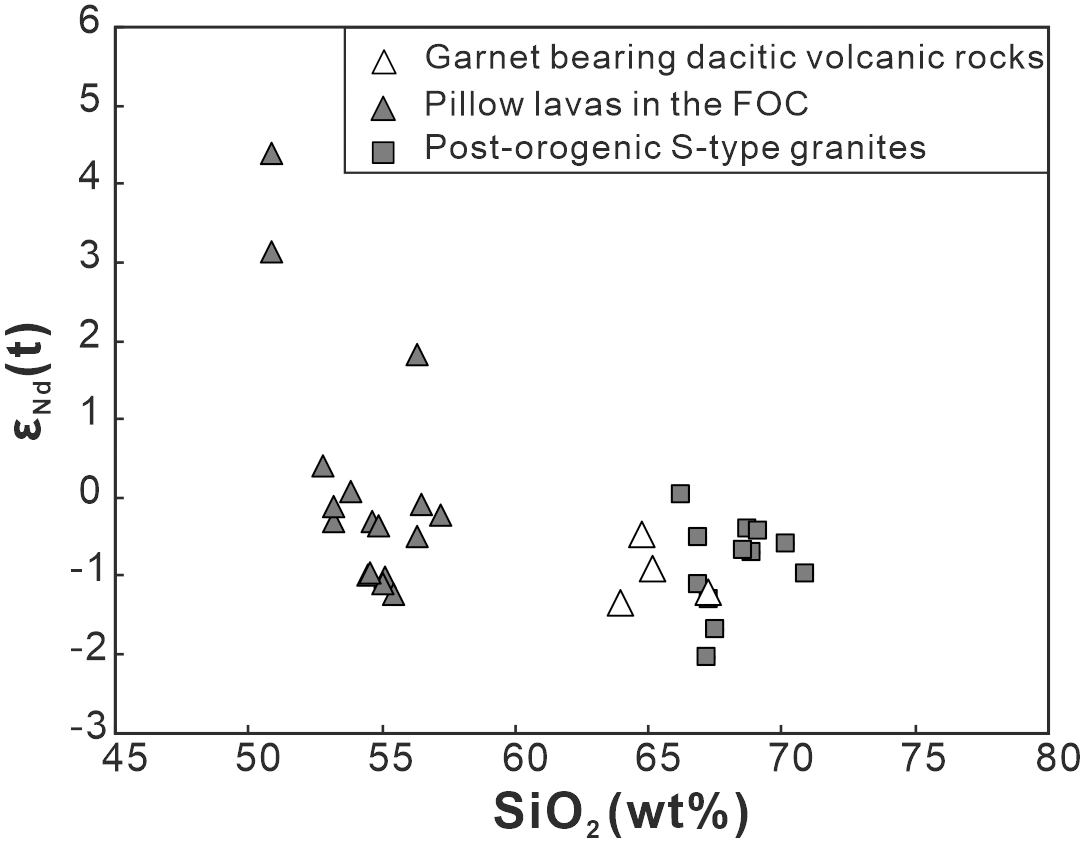

The trace element patterns and Nd isotopic compositions of the garnet-bearing dacitic rocks resemble those of post-orogenic S-type granites in the study region, showing enrichment in large-ion lithophile elements (e.g. Rb, Sr, Th), negative Nb anomalies (Figure 10a) and ϵNd(t) (–1.4 to –1.2) (Figure 11). Their rare earth element (REE) patterns are characterized by light rare earth elements (LREE) enrichment with only minor heavy rare earth elements (HREE) depletion (Figure 10b), as indicated by low (Gd/Lu) N (1.2–1.8).

Figure 10. (a) Primitive mantle-normalized trace element diagrams and (b) chondrite-normalized REE patterns for garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks associated with the FOC. The data sources of the post-orogenic S-type granite are the same as in Figure 9. C1-Chondrite and primitive mantle factors are from Sun & McDonough (Reference Sun and McDonough1989).

Figure 11. SiO2 vs. ϵNd(t) diagram for the garnet-bearing dacitic rocks, pillow lavas in the FOC and the post-orogenic S-type granites. The data sources and symbols are the same as in Figure 9.

According to Zr contents (160–239 ppm) and the model of Watson & Harrison (Reference Watson and Harrison1983), the zircon saturation temperatures (Table 1) of the garnet-bearing dacitic rocks are 900–945℃ (Supplementary Table S4). This temperature range overlaps with Ti-in zircon temperatures and is comparable to the temperatures of coeval A-type granites (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Wang, Zhao and Zheng2018).

5 Discussion

5.a. Origin of the garnets

Garnet in silicic volcanic rocks can present magmatic phenocrysts, xenocrysts from wall rocks or relict phases inherited from source rocks (Tsvetkov & Borisovskiy, Reference Tsvetkov and Borisovskiy1980; Harangi et al. Reference Harangi, Downes, Kósa, Szabo, Thirlwall, Mason and Mattey2001; Kawabata & Takafuji, Reference Kawabata and Takafuji2005). Accurately distinguishing between these origins is crucial for petrogenetic and tectonic interpretations. Previous studies have demonstrated that the FOC and surrounding Xikou Group experienced only greenschist-facies metamorphism (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Zhao, Yu, Qiu and Xing2014), lacking metamorphic garnet. This observation indicates that the garnets in the dacitic volcanic rocks are unlikely to be xenocrysts derived from the wall rocks.

Furthermore, no garnet is enclosed by other mineral phases, while garnet and alkali feldspar grains are locally sheared along the foliation (Figures 4a and 5a). These textural relationships suggest that garnet crystallized early, prior to the regional deformation and metamorphism. In contrast to typical metamorphic garnets, garnet fragments in dacitic volcanic rocks associated with FOC lack compositional zoning and metamorphic mineral inclusions, whereas they contain ilmenite or apatite inclusions, consistent with those of magmatic garnet phenocrysts in intermediate to silicic volcanic rocks (Harangi et al. Reference Harangi, Downes, Kósa, Szabo, Thirlwall, Mason and Mattey2001; Mirnejad et al. Reference Mirnejad, Blourian, Kheirkhah, Akrami and Tutti2008; Patranbis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Schieber and Basu2009. Geochemically, the garnets exhibit low, uniform MnO and high TiO2, contrasting with variable MnO and very low TiO2 (<0.08 wt%) of typical metamorphic garnets (Figure 12).

Figure 12. (a) Garnet MnO vs. CaO adapted from Harangi et al. (Reference Harangi, Downes, Kósa, Szabo, Thirlwall, Mason and Mattey2001) and (b) MnO vs. TiO2 diagrams that show the compositional differences between almandine-rich garnets from different origins. Almandine-rich garnets from metapelites typically have TiO2 < 0.08 wt% (data from Whitney & Dilek, Reference Whitney and Dilek1998; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, McDougall, Ellis and Williams2000; Zeh & Holness, Reference Zeh and Holness2003; Miyazaki, Reference Miyazaki2004; Cai et al. Reference Cai, Liu and Liu2017; Nakano et al. Reference Nakano, Osanai, Owada, Satish-Kumar, Adachi, Jargalan and Boldbaatar2015). The data of almandine-rich garnets in metaluminous silicic volcanic rocks were collected from Kawabata & Takafuji (Reference Kawabata and Takafuji2005) (Setouchi volcanic belt, southwest Japan), Harangi et al. (Reference Harangi, Downes, Kósa, Szabo, Thirlwall, Mason and Mattey2001) (North Pannonian Basin, Europe) and Bach et al. (Reference Bach, Smith and Malpas2012) (Northland Arc). The data of almandine-rich garnets in peraluminous silicic volcanic rocks are from Hamer & Moyes (Reference Hamer and Moyes1982) (Antarctica), Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Chu, Shen, Chen and Wang1992) (South China), Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Zhang, Santosh, Zhao and Chen2017) (Northwest China), Clemens & Wall (Reference Clemens and Wall1984) (Victoria, Australia), Mirnejad et al. (Reference Mirnejad, Blourian, Kheirkhah, Akrami and Tutti2008) (Deh Salm area, Iran), Patranabis-Deb et al. (Reference Patranabis-Deb, Schieber and Basu2009) (Chhattisgarh Basin, India) and Sieck et al. (Reference Sieck, López-Doncel, Dávila-Harris, Aguillón-Robles, Wemmer and Maury2019) (Mesa Central, Mexico).

Collectively, the petrographic and geochemical evidence indicate that garnets in the dacitic volcanic rocks are primary magmatic phases and can therefore be used to constrain the petrogenesis of their host magmas and the regional tectonic evolution.

5.b. Petrogenesis of the garnet-bearing dacitic rocks

In the Harker diagrams (Figure 9a–e), the garnet-bearing dacitic rocks are separated from the coexisting pillow lavas by a ∼6 wt% SiO2 gap. This compositional gap indicates that the volcanism associated with FOC was bimodal, as documented in coeval volcanic rocks in the JO (Lyu et al. Reference Lyu, Li, Wang, Pang, Cheng and Li2017; Figure 9f). Silicic magmas of bimodal associations typically form via crustal partial melting triggered by basaltic underplating (Suneson & Lucchitta, Reference Suneson and Lucchitta1983; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Sun, Shen, Shu and Niu2006; Sieck et al. Reference Sieck, López-Doncel, Dávila-Harris, Aguillón-Robles, Wemmer and Maury2019), although mafic magma differentiation may also contribute in certain contexts (e.g. Briand et al. Reference Briand, Bouchardon, Capiez and Piboule2002).

The limited geochemical variations in the Harker diagrams suggest that the crustal crystallization differentiation during garnet-bearing dacitic magma ascent was negligible. Moreover, given that garnet-bearing dacitic rocks have similar or even higher FeOt and TiO2 contents compared to the coeval pillow lavas, they are unlikely to be derived from the differentiation of a mafic magma, as crystallization differentiation would lower the concentrations of these elements in evolved melts (Sisson & Grove, Reference Sisson and Grove1993; Grove et al. Reference Grove, Elkins-Tanton, Parman, Chatterjee, Müntener and Gaetani2003).

The analyzed garnets show geochemical characteristics consistent with those in peraluminous silicic volcanic rocks globally (Figure 12). In addition, their host rocks are weakly peraluminous and exhibit geochemical and Nd isotopic characteristics comparable to post-orogenic S-type granites in the eastern JO (Figure 8, 10–11). These observations strongly suggest that the primary magma of the garnet-bearing dacitic rocks originated from partial melting of crustal materials (e.g. Patiño Douce & Johnston, Reference Patiño Douce and Johnston1991).

The low garnet MnO (<4.0 wt%) and CaO contents support a deep crustal origin for their host magmas, as Mn-poor garnets are stable only at high pressures (>5–7 kbar) in felsic melts (Green, Reference Green1976, Reference Green1977; Clemens & Wall, Reference Clemens and Wall1984; Skjerlie & Johnston, Reference Skjerlie and Johnston1996). This interpretation is confirmed by applying the machine-learning-based thermobarometer of Weber & Blundy (Reference Weber and Blundy2024) to the garnet + alkali feldspar + biotite assemblage and the whole-rock major-element composition, which yields pressures of 6.0–7.7 kbar (Supplementary Table S4), consistent with a lower crustal condition.

Regarding zircon Hf isotopic composition, zircon crystals from the garnet-bearing dacitic rocks display large intra-sample ϵHf(t) variations (Figure 6b), as observed in many S-type granitic rocks (e.g. Iles et al. Reference Iles, Hergt and Woodhead2018; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Li2021). Such variations may reflect a compositionally heterogeneous magma source (e.g. Hammerli et al. Reference Hammerli, Kemp, Shimura, Vervoort and Dunkley2018), mixing of isotopically diverse magmas (e.g. Streck, Reference Streck2008), or disequilibrium melting processes (e.g. Tang et al. Reference Tang, Wang, Shu, Wang, Yang and Gopon2014). Magma mixing is unlikely given the absence of petrographic evidence (e.g. resorbed minerals, mafic enclaves), and the high magma temperatures would have promoted Hf diffusion, minimizing isotopic heterogeneity from disequilibrium melting (Tang et al. Reference Tang, Wang, Shu, Wang, Yang and Gopon2014; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Du and Li2021). Therefore, the observed large zircon ϵHf(t) variations are best explained by a heterogeneous magma source.

Compositionally, the garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks plot within the fields of both metapelitic and metabasic sources (Figure 13, Altherr and Siebel, Reference Altherr and Siebel2002), suggesting the involvement of both lithologies in the source region. The most isotopically depleted zircons with ϵHf(t) values comparable to coeval mafic intrusions (Figure 7) suggest a juvenile, metabasaltic source component (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Wang, Qiu, O’Reilly, Xu, Liu and Zhang2007, Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Zhao, Yu, Qiu and Xing2014). In contrast, zircons with negative ϵHf(t) values (−9.1 to −3.0) indicate isotopically enriched metapelitic contributions, likely represent the basement of the Yangtze Craton.

Figure 13. Chemical compositions of partial melts derived from various sources (Altherr & Siebel, Reference Altherr and Siebel2002). The symbols and data source are the same as in Figure 9.

In terms of magma temperature, the >900℃ zircon saturation temperatures and low Al2O3/TiO2 ratios (20–29) are characteristic of ‘hot granites’ (Miller et al. Reference Miller, McDowell and Mapes2003; Bucholz & Spencer, Reference Bucholz and Spencer2019) while resembling the ultrahigh-temperature post-collisional granites in South Bohemian batholith of the Variscan orogenic belt (Finger et al. Reference Finger, Schiller, Lindner, Hauzenberger, Verner and Žák2022). The generation of such high-temperature crustal magma typically requires additional heat input from mantle-derived mafic magma underplating (Miller et al. Reference Miller, McDowell and Mapes2003; Finger et al. Reference Finger, Schiller, Lindner, Hauzenberger, Verner and Žák2022). Considering the widespread occurrence of coeval mafic rocks in the JO (e.g. Zhang & Wang, Reference Zhang and Wang2020; Hong et al. Reference Hong, Yu, Song, Chu, Liu and Zhou2022), we infer that the garnet-bearing dacitic magmas were generated by high-temperature partial melting of a heterogeneous lower-crustal source comprising both juvenile basaltic and ancient pelitic components, triggered by such underplating-induced heating.

5.c. Tectonic setting of the garnet-bearing dacitic rocks

The Neoproterozoic southern margin of the Yangtze Craton represents an active continental margin and was juxtaposed to a multi-arc oceanic basin to the south (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhao, McCulloch, Zhou and Xing1997). This system eventually evolved into the JO during the amalgamation of the Yangtze Craton and the Cathaysia Block (e.g. Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cawood, Shu and Zhao2019). Several models have been proposed for the specific tectonic setting of the FOC or the coeval magmatic rocks of the JO, including back-arc basin within a continental margin (Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Hb, Yang and Wang1989; Li et al. Reference Li, Zhao, McCulloch, Zhou and Xing1997; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Zhao, Yu, Qiu and Xing2014; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Wang, Qi, Zhang, Wang, Li and Shu2018a), island arc (Xing, Reference Xing1990) and fore-arc setting (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Santosh, Zou, Li and Huang2013; Zhao & Aismow, Reference Zhao and Asimow2014).

As demonstrated above, ∼860–820 Ma volcanic rocks occurred in the eastern JO are bimodal (Figure 9f). Such bimodal magmatism is uncommon in typical continental or oceanic island arcs but is characteristic of many ensialic back-arc basins (e.g. the Okinawa Trough, Japan Sea and Bransfield Strait, Shinjo et al. Reference Shinjo, Chung, Kato and Kimura1999; Keller et al. Reference Keller, Fisk, Smellie, Strelin and Lawver2002), where garnet-bearing volcanic rocks are typically present in the initial stage of basin rifting (Keller et al. Reference Keller, Fisk, Smellie, Strelin and Lawver2002; Kawabata & Takafuji, Reference Kawabata and Takafuji2005). Moreover, mafic rocks in the FOC and those interlayered in the basement sequence of eastern JO exhibit both arc-like and MORB-like trace element patterns (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wu and Zheng2012; Yao et al. Reference Yao, Shu and Santosh2014; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Wang, Yu, Zhou and Sun2017; Hong et al. Reference Hong, Yu, Song, Chu, Liu and Zhou2022). This compositional diversity is also typical of basaltic rocks in extensional back-arc basins, reflecting complex mantle sources, crustal interactions and subduction-related metasomatism (Saunders & Tarney, Reference Saunders and Tarney1984; Keller et al. Reference Keller, Fisk, Smellie, Strelin and Lawver2002; Shinjo et al. Reference Shinjo, Chung, Kato and Kimura1999; Pearce & Stern, Reference Pearce and Stern2006).

Based on above evidence, we interpret the garnet-bearing volcanic rocks associated with the FOC to have formed in a back-arc setting. Detrital zircon U-Pb ages and dates from interlayered volcanic rocks suggest that the basement sequences in the JO were deposited between ∼860 and ∼820 Ma (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Wang, Qiu, O’Reilly, Xu, Liu and Zhang2007, Reference Wang, Wang, Zhou and Shu2013a; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Wang, Yu, Zhou and Sun2017; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Wang, Qi, Zhang, Wang, Li and Shu2018a), constraining the timing of the back-arc basin formation. The widespread Mesoproterozoic to Paleoproterozoic zircons in the ∼860–820 Ma magmatic rocks of the basement sequence indicate that the back-arc basin developed on an ancient continental crust (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Zhao, Yu, Qiu and Xing2014; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wu and Zheng2012; Lyu et al. Reference Lyu, Li, Wang, Pang, Cheng and Li2017), and thus is comparable to modern analogues such as the Okinawa Trough and Japan Sea (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhao, McCulloch, Zhou and Xing1997; Hong et al. Reference Hong, Yu, Song, Chu, Liu and Zhou2022), as originally proposed by Zhou et al. (Reference Zhou, Hb, Yang and Wang1989).

5.d. Implications for tectonic evolution of eastern JO

Garnet-bearing silicic volcanic rocks in fossil orogens commonly occur in regional extensional settings that closely follow early crustal thickening or orogeny (Clemens and Wall, Reference Clemens and Wall1984; Gilbert & Rogers, Reference Gilbert and Rogers1989; Harangi et al. Reference Harangi, Downes, Kósa, Szabo, Thirlwall, Mason and Mattey2001; Coira et al. Reference Coira, Kay, Viramonte, Kay and Galli2018; Sieck et al. Reference Sieck, López-Doncel, Dávila-Harris, Aguillón-Robles, Wemmer and Maury2019). The ∼840 Ma garnet-bearing dacitic rocks reported here, together with the ∼860 Ma garnet-bearing diorite located southwest of the FOC (Cui et al. Reference Cui, Zhu, Fitzsimons, Wang, Lu and Wu2017), record an orogenic event and crustal thickening predating ∼860 Ma. This orogenic event clearly occurred before the ∼820 Ma Jinning (or Sibao) orogeny and reflects a distinct tectonic process.

In the Jiuling Terrane, widespread ∼860–970 Ma detrital zircons and island-arc plagiogranite lithoclasts derived from Shuangxiwu arc terrane indicate sedimentary input from the arc (Wang & Zhou, Reference Wang and Zhou2013; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Zhou and Shu2013a; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Griffin, Zhao, Yu, Qiu and Xing2014). Meanwhile, the Luojiamen Formation, which unconformably overlies the Shuangxiwu arc volcanic rocks, contains plenty of Mesoproterozoic to late Archaean detrital zircons sourced from the Yangtze Craton (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Zhou and Shu2013a; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Wang, Yu, Zhou and Sun2017). As the Shuangxiwu arc terrane formed in an intra-oceanic setting (Figure 14a, Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Li, Lo, Wang, Ye and Yang2009), these observations indicate that the Shuangxiwu and the Jiuling terranes were juxtaposed by ∼860 Ma, enabling mutual sedimentary exchange during basement sequence deposits.

Figure 14. A simplified model for the Neoproterozoic tectonic evolution of the eastern JO. (a) Early Neoproterozoic (∼970–880 Ma) Shuangxiwu Island-arc formed due to the eastern subduction. (b) The collision between the arc and the Yangtze Craton took place at ∼880–860 Ma. (c) After the collision, subduction polarity reversal results in the new continent arc and the back-arc basin rifting. In the back-arc basin, the FOC and associated garnet-bearing dacitic volcanic rocks were generated. (d) The collision between the Cathaysia Block and the south margin of Yangtze Craton resulted in extensive post-orogenic S-type granites in the eastern JO.

Therefore, the orogeny responsible for crustal thickening and the subsequent garnet-bearing magmatism is best ascribed to the collision between the Shuangxiwu island-arc and the southeastern margin of Yangtze Craton (Figure 14b, Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhou, Wan, Kitajima, Wang, Bonamici, Qiu and Sun2013b; Cui et al. Reference Cui, Zhu, Fitzsimons, Wang, Lu and Wu2017). This collision is also evidenced by the ∼866 Ma blueschist in the NE Jiangxi ophiolite and by regional southeastward thrusting associated with the obduction of the Yangtze Craton margin over the Shuangxiwu Island-arc Terrane (Figure 14b; Shu & Charvet, Reference Shu and Charvet1996; Charvet, Reference Charvet2013). In this context, the NE Jiangxi Fault and associated ophiolites (NE Jiangxi ophiolite and FOC, Figure 1) mark the suture between the collided arc terrane and the continental margin (Figure 14b). The timing of this arc–continent collision, constrained by ∼880 ± 19 Ma obduction-related leucogranite in the NE Jiangxi ophiolite (Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Li and Lou2008; Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cawood, Shu and Zhao2019) and 863 ± 4 Ma basal conglomerate of the Luojiamen Formation (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Zhou and Shu2013a), is ∼880–860 Ma (Cui et al. Reference Cui, Zhu, Fitzsimons, Wang, Lu and Wu2017; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Shu, Santosh and Wang2018b).

Before the collision, ∼970–860 Ma magmatism was restricted in the Shuangxiwu arc and characterized by highly depleted Nd-Hf isotopic compositions (e.g. ϵNd(t) ∼5–10, Xia et al. Reference Xia, Xu, Niu and Liu2018), consistent with an eastward subduction (Figure 14a, Li et al. Reference Li, Li, Li, Lo, Wang, Ye and Yang2009). By contrast, ∼860–830 Ma magmatism with enriched isotopic signatures (e.g. ϵNd(t) < ∼3) was widespread across the JO and locally intruded Shuangxiwu arc volcanic rocks (e.g. Shenwu diorite and Gangbian complex, Figure 14c, Li et al. Reference Li, Li and Li2010), recording a switch to westward subduction (Shu & Charvet, Reference Shu and Charvet1996; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang, Zhou and Shu2013a; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Wang, Yu, Zhou and Sun2017). Such contrasting spatial distributions and isotopic features between the two magmatic stages provide robust evidence for subduction polarity reversal along the Yangtze Craton margin (Clift et al. Reference Clift, Dewey, Draut, Chew, Mange and Ryan2004; Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Ellis and Mann2009; Magni et al. Reference Magni, Faccenna, van Hunen and Funiciello2014; Tao et al. Reference Tao, Yin, Spencer, Sun, Xiao, Kerr, Wang, Huangfu, Zeng and Chen2024). The absence of prolonged UHP metamorphism and long-lived post-collisional magmatism, together with the rapid spatial-temporal reorganization of regional magmatism, suggests that compression-induced plate coupling during arc–continent collision could have facilitated the polarity reversal (Tao et al. Reference Tao, Yin, Spencer, Sun, Xiao, Kerr, Wang, Huangfu, Zeng and Chen2024), a mechanism that warrants further investigation.

Following the subduction reversal, a new continent arc formed in the southeast margin of Yangtze Craton, represented by ∼830 Ma Miaohou arc-like diorites and high-Mg diorites that intrude the basement sequence in Hunan (Xia et al. Reference Xia, Xu, Niu and Liu2018). However, considering the rarity of such typical arc-like rock in the eastern JO, this continental arc could be largely eroded by continued subduction (e.g. Clift et al. Reference Clift, Dewey, Draut, Chew, Mange and Ryan2004; Yamamoto et al Reference Yamamoto, Senshu, Rino, Omori and Maruyama2009). Zhuji and Longsheng ophiolite relics (∼870–855 Ma) sporadically occur within the Shaoxing–Jiangshan suture, alongside deep-sea turbidites, broadly outlining the leading edge of the ∼860–820 Ma continental arc (Shu et al. Reference Shu, Faure, Jiang, Yang and Wang2006; Yao et al. Reference Yao, Cawood, Shu, Santosh and Li2016).

Furthermore, subduction polarity reversal can relieve the resistive forces of collisional shortening through reversed subduction, leading to rapid uplift and collapse of the original collisional orogen (Draut & Clift, Reference Draut and Clift2012; Dewey, Reference Dewey2005; Zhang & Leng, Reference Zhang and Leng2021). Therefore, the subduction polarity reversal may have also triggered the opening of the back-arc basin (Figure 14c, Clift et al. Reference Clift, Dewey, Draut, Chew, Mange and Ryan2004; Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Ellis and Mann2009; Magni et al. Reference Magni, Faccenna, van Hunen and Funiciello2014). Upwelling of hot asthenosphere during back-arc opening caused partial melting of the lower crust, generating garnet-bearing silicic magmas and high-temperature A-type granites (Figure 14c, Huang et al. Reference Huang, Wang, Zhao and Zheng2018). Following the ocean closure, the Yangtze Craton and Cathaysia blocks collided, forming the JO and generating a series of S-type granites, such as the Shexian pluton intruded in the FOC (Figure 14d).

6. Conclusions

-

1) Magmatic garnets from the ∼840 Ma dacitic volcanic rocks associated with FOC are predominantly almandine (76–79%) with minor grossular (12–19%). Their composition, together with the geochemistry of the host rocks, indicates crystallization from peraluminous magmas. These magmas originated from the partial melting of a heterogeneous lower-crustal source, which was constituted by a mixture of juvenile basaltic and ancient pelitic components, under high-temperature (>900°C) and lower-crust pressure.

-

2) The presence of the unusual garnet-bearing volcanic rocks records the initial extension of the back-arc basin along the Yangtze Craton margin. This extension immediately followed the ∼880–860 Ma collision of the Shuangxiwu Island-arc Terrane with the southeastern Yangtze margin. We propose that the collapse of the collisional orogen, triggered by subduction polarity reversal following the arc–continent collision, was the primary mechanism for the opening of this back-arc basin.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756826100533

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the constructive comments provided by Dr. André Cravinho and careful editorial handling by Dr. Sarah Sherlock. We also sincerely thank Pro. R. Klemd for his help in improving the English text.

Financial support

This study was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant number 2022YFF0800401), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 41702061) and the China Geological Survey Program (Grant numbers DD20240037, DD20242972).

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.