According to Alzheimer’s Disease International there are over 10 million new cases of the devastating disease every year – one new case every 3 s. 1 Cognitive impairment caused by neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease creates significant challenges for patients, their families and friends, and clinicians who provide their healthcare. Reference Morley, Morris, Berg-Weger, Borson, Carpenter and del Campo2 Early recognition of these problems allows for diagnosis and appropriate treatment, education, psychosocial support and engagement in shared decision-making regarding life planning, healthcare, involvement in research, and financial matters. Although there is no known cure for Alzheimer’s and other dementias, pharmacological and lifestyle interventions can extend the quality of life for those affected. Reference Devanand, Masurkar and Wisniewski3,Reference Ornish, Madison, Kivipelto, Kemp, McCulloch and Galasko4 Dementia is the seventh leading cause of death and ‘one of the major causes of disability and dependency among older people globally’, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). 5 In 2019 an estimated 55 million people had dementia, which is projected to have a global cost of $2.8 trillion by 2030. 5 The majority of these individuals with dementia (60%) live in low- and middle-income countries, and this number is expected to rise to 71% in the next 25 years. 5 Egypt has a population of 110 million people, one-quarter of the world’s Arabic-speaking population, and to date there are 3 to 5 million known cases of dementia. Reference Elshahidi, Elhadidi, Sharaqi, Mostafa and Elzhery6

Cognitive screening tools used in the Arab world

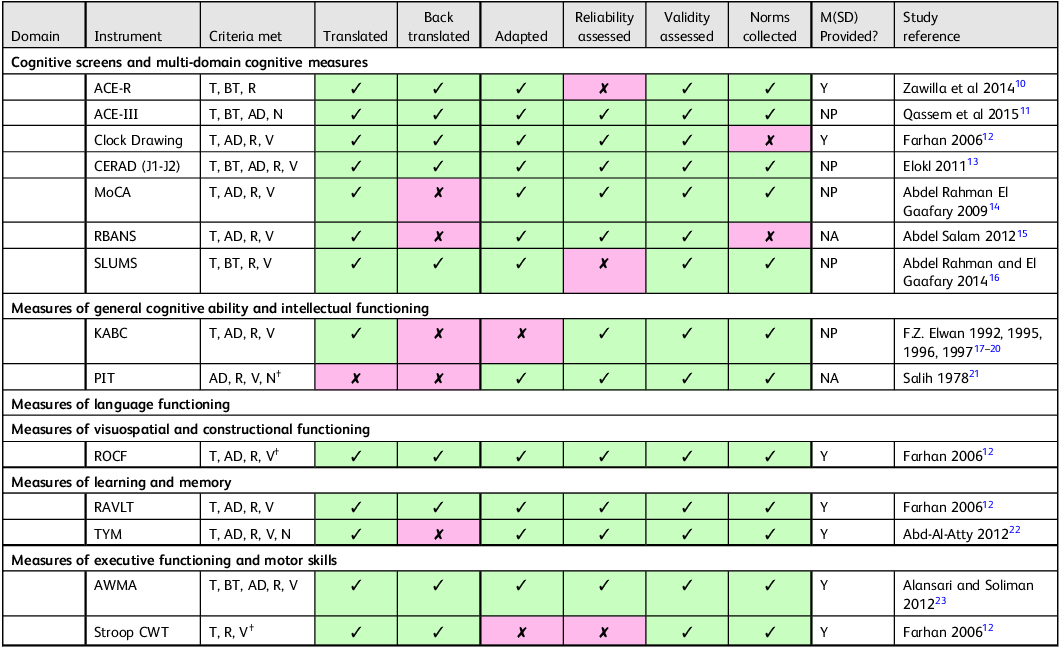

In 2017, Fasfous and colleagues published a systematic review of the literature on neuropsychological testing measures in the Arab world. Reference Fasfous, Al-Joudi, Puente and Pérez-García7 The purpose was to understand which tools had met the quality criteria for appropriate adaptation for use in the region. The quality criteria were that the tests had been translated into the local dialect, back-translated, adapted, reliability assessed, validity assessed, and that normative data had been collected. The review included 384 studies, nearly half (176) of which were from Egypt. Half of these 176 publications reported tests that were not developed, translated, adapted or standardised according to international guidelines of psychological measurement. Reference Judd, Colon, Dutt, Evans, Hammond and Hendriks8,Reference Nguyen, Rampa, Staios, Nielsen, Zapparoli and Zhou9 Only 17% of the 176 studies included validation and/or normative data. Tests were included in the review if they met 3 or more of the quality criteria and reported more than 40 data points from healthy individuals for comparison. Just 14/176 tests met these criteria (Table 1). Table 2 illustrates studies with the most extensive adaptation, validation and norming that have been published since Fasfous and colleagues initial systematic review. Reference Fasfous, Al-Joudi, Puente and Pérez-García7

Table 1 Egyptian studies on neuropsychological measures with the most extensive adaptation, validation and norming, as reported in Fasfous et al (2017) Reference Fasfous, Al-Joudi, Puente and Pérez-García7

† Some of Fasfous et al’s (2017) Reference Fasfous, Al-Joudi, Puente and Pérez-García7 suggested adaptation quality criteria may not apply to this test (e.g. when aspects of the test did not require linguistic adaptation).

Y = Yes.

NP = Not provided.

NA = Not accessed but cited elsewhere as fulfilling criteria.

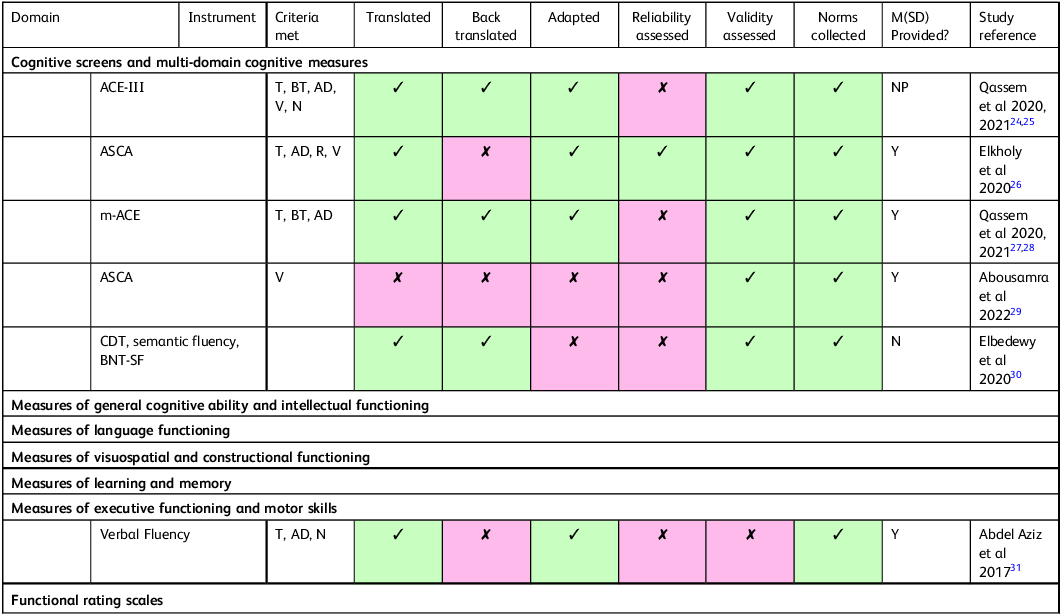

Table 2 Egyptian studies with the most extensive adaptation, validation and norming published after Fasfous et al (2017) Reference Fasfous, Al-Joudi, Puente and Pérez-García7

Y = YES.

NP = Not Provided.

NA = Not accessed but cited elsewhere as fulfilling criteria.

ASCA = Ain Shams Cognitive assessment scale.

Verbal Fluency = includes letter and category fluency.

Cognitive screening tools used in Egypt in particular

A number of cognitive screening tools used in the West are also used to conduct cognitive assessments in Egypt. Generally speaking, these have been translated into literary Arabic so they can be used with the Arabic-speaking Egyptian population. However, most of these tests have not been properly adapted, standardised and validated according to International Test Commission (ITC) guidelines for cross-cultural adaption of cognitive screening measures. Reference Judd, Colon, Dutt, Evans, Hammond and Hendriks8,Reference Nguyen, Rampa, Staios, Nielsen, Zapparoli and Zhou9

In the autumn of 2023 a conference was held in Egypt to discuss cross-cultural adaptation of cognitive screening and assessment measures for use with Egyptian Arabic populations. We surveyed conference participants on the use of these tools in Egypt and ran a forum at the conference to explore Arabic-language cognitive measures more broadly. This paper presents the results of the survey and discusses themes emerging from the forum.

Method

A survey on the use of cognitive screening tools in Egypt was sent to registrants of the 2023 Cognitive Screening and Cognitive Interventions in Egypt conference. Of the 88 who registered in advance, 23 agreed to participate in the survey, 3 of whom were male. Participants were practitioners, trainees/students and academics who worked or practiced in Egypt. Of those who were practising, most had between 11 and 20 years of experience, with 1 person having more than 20 years and 5 people having less than 11 years. Eleven of the respondents were academics or recent graduates and did not report using tools such as these for assessment. They did, however, provide further cultural insights regarding research capacity and cross-cultural adapation into Egyptian society.

The survey asked participants: what screening tools they currently used; what screening tools they would like to begin using; what screening tools they have observed their colleagues using; and what screening tools they believed are appropriate for the Egyptian population. It included an additional open-ended question regarding what might be done to improve screening.

Ethics

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Institutional Review Board of The American University in Cairo (Case no. 2023-2024-049). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the survey prior to answering any of the survey questions.

Results

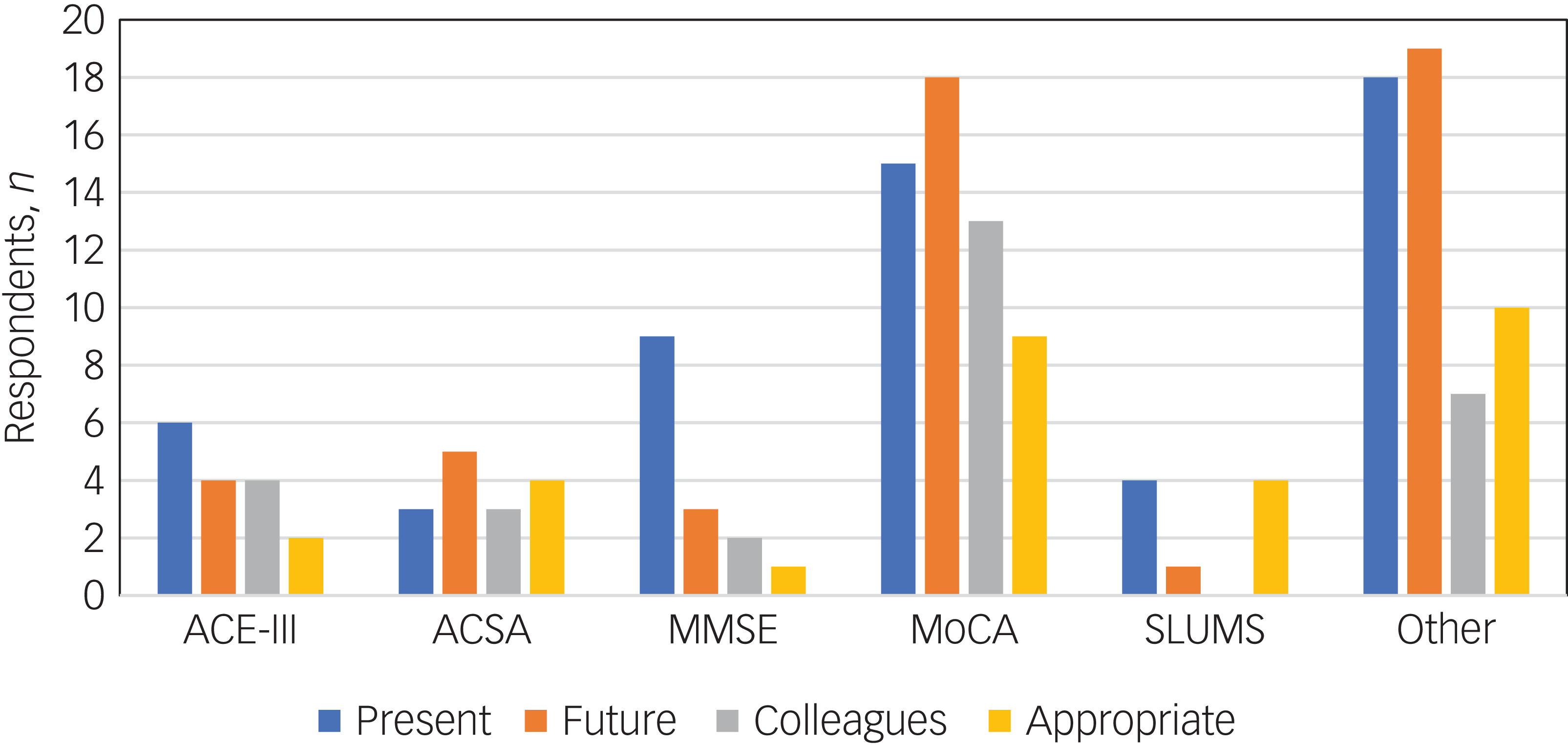

Figure 1 summarises the results of our survey of assessment tools. Most Egyptian practitioners surveyed reported using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE), the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination, Third Edition (ACE-III) and the Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) tests, all of which have been translated into literary Arabic. Other Western-oriented tools were reportedly used, although in smaller numbers, such as the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS), the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) assessments and Weschler tests.

Fig. 1 Use of cognitive impairment screening tools in Egypt as reported by the survey respondents (n = 23). ACE-III, Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination, Third Edition; ASCA, Ain Shams Cognitive Assessment; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SLUMS, Saint Louis University Mental Status test; Present, screening tools the participant currently uses; Future, screening tools they wish to begin using; Colleagues, screening tools they have observed their colleagues using; Appropriate, screening tools they believe are appropriate for the Egyptian population. For example, 6 reported currently using the ACE-III and 18 reported wanting to use the MoCA in the future. We included wanting to use a new or different version of the MoCA than they are currently using, as ‘future’ tools.

Discussion

The majority of our respondents with experience of conducting cognitive evaluations reported using tools developed in the West, such as the MoCA and MoCA-B tests. Many have been translated into literary Arabic and some screening measures have been validated in Egyptian populations. Reference Zawilla, Taha, Kishk, Farahat, Farghaly and Hussein10–Reference Farhan12 However, the lack of information on the clinical validity of the majority tests available for Arabic-speaking individuals has implications at the heart of neuropsychological service provision. Namely, using such measures can result in errors of measurement. False positives may occur, incorrectly concluding dementia and risking stigmatisation. False negatives might also occur, thereby missing dementia and consequently missing out on treatment/management opportunities.

However, Egyptian practitioners have astutely taken steps to resolve issues related to test validation in their patient population, and some tests, such as the MoCA (Basic version) and the ACE-III, have been validated among Egyptians with dementia and/or cognitive impairment. 5–Reference Fasfous, Al-Joudi, Puente and Pérez-García7 Future work in this vein could include some of the other tests reportedly used and adhere to the recently published ITC guidelines. Reference Judd, Colon, Dutt, Evans, Hammond and Hendriks8 A group of geriatric doctors have developed a cognitive assessment tool designed specifically for Egyptians, the Ain Shams Cognitive Assessment (ASCA). The ASCA, named after the Ain Shams University Hospital, avoids some of the problems associated with unadapted, globally popular measures. Reference Rasheedy, Abou-Hashem, Mohammedin, Hassanin and Tawfik32 These doctors also operate a memory clinic which rehabilitates diagnosed patients. Reference Qassem, Khater, Emara, Rasheedy, Tawfik and Mohammedin11

How might screening be improved?

In addition to querying the respondents regarding the cognitive screening tools currently in use, the survey included an open-ended question regarding what might be done to improve screening. This was also discussed during a conference forum involving the Egyptian delegates and the conference speakers representing other nations. The resulting qualitative analysis of the comments revealed five main themes: training, collaboration, validation, adaptation (including translation) and community engagement.

Training

Many younger practitioners who were still in training reflected on the dearth of training programmes giving guidance on how to conduct cognitive assessments. Furthermore, some of the practitioners described wanting to use certain tools that they were not trained to administer. It seems that part of the problem is a lack of awareness among the public and healthcare workers about the nature and severity of brain diseases. At the moment in Egypt there are limited options for acquiring the proper training, and the online options that are offered are often at inappropriate times, exclusively in English and expensive in relation to most Egyptians’ available resources.

Collaboration

Practitioners and practitioners-in-training alike wanted more opportunities for collaboration. Clinical neuropsychology is new in Egypt, with just a handful of trained professionals practising. Collaborations between doctors and researchers largely occur within a practice, with few gaps being bridged across practices or laboratories. One doctor expressed appreciation at the chance to collaborate with the other doctors present and a practitioner-in-training from Somalia thought it would be possible to collaborate between the two countries.

Validation

To our knowledge, very few cognitive assessments now used in Egypt have been fully normed and validated according to ITC guidelines Reference Judd, Colon, Dutt, Evans, Hammond and Hendriks8 in an Egyptian population. However, we believe that the lack of fully standardised and validated tools for this population is not reflective of the desire for properly developed tools. This belief is supported by clinicians’ views regarding test properties such as good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, predictive power, construct validity, specificity and sensitivity. Namely, all judged these properties to be important, rating the desirability of each at between 4 and 5 out of 5. So, although most of the tests have not undergone rigorous evaluation, that does not reflect a lack of desire for robust test measures.

Adaptation

Two main issues emerged regarding adaptation of measures when clinicians were asked their thoughts. The first was adaptations for individual physical disabilities and the other was Egyptian cultural adaptation. Individuals with disabilities are at a disadvantage when presented with a Western-made test designed for a non-disabled person. Clinicians mentioned that some of their patients are blind and cannot complete the drawing tests or other tests that rely on vison. Aphasic patients, they pointed out, are non-verbal and so the many verbal fluency tests present in most measures are completely ineffective, as are any verbally based working memory measures. They also highlighted the need for tests for those who are hard of hearing and illiterate.

Cultural adaptation should ensure that tests include appropriate and relevant test items. For example, one item on one of the popular cognitive measures requires patients to remember five words, two of which are ‘daisy’ and ‘church’. Although these are common Western words, they could have diminished relevance to an Egyptian. Egyptian culture recognises and appreciates flowers, but daisies per se are less familiar. Similarly, Egypt has many churches, but is a predominantly Muslim country and so churches are less prevalent. Although these test items might be less relevant to Egyptians, another test item includes an image of a camel, with two other animals, that the person must name. Near certain tourist areas in Egypt camels are very prevalent and might therefore be seen almost daily. This is advantageous for Egyptians who are completing this test item, but the item may not culturally appropriate for most Westerners. In short, the geographical, cultural and linguistic contexts must be accounted for as tests are translated from English into Arabic.

Translation

An issue under the heading of adaptation is that of translation. Many Western-made cognitive assessments have been translated into Arabic. Although this may seem relatively straightforward, utilising these translated tests is not that simple for practitioners or patients. The primary issue is the matter of the Arabic language into which the tests have been translated. In the 24 countries for which Arabic is an official language, there is diglossia, meaning there are two varieties of the same language used under different conditions. Citizens of these countries use Modern Standard, or literary, Arabic for news and media, education, official communications, legal documents and so forth. However, informal communication takes place using colloquial Arabic, also known as spoken Arabic, and this is entirely different for each country, with speakers from some countries, such as Morocco, being unable to effectively communicate with speakers from other Arab states. This situation biases those who can be effectively tested, as only those who are well-educated are proficient in Modern Standard Arabic. Practitioners are aware of this and will often swap out terms and phrases to make the test more appropriate for certain patients. However, as those techniques have not been standardised, this ad hoc approach can lead to inconsistencies within and between practices.

Community engagement

Many practitioners highlighted the need for increased public awareness. The thinking is that as more people are aware of the importance of brain health and that cognitive impairment is treatable, they will be more likely to go to the doctor, or refer a family member, in suspected cases. Public awareness is also a avenue to prevention and early intervention, which are underappreciated in Egypt. They want it to be known that cognitive decline is not ‘just part of the ageing process’, so that people do not let individuals with mild cognitive problems become worse. Some doctors also impart caregiver training and want to bring to light people with lived experience to explain their stories as guidance for others.

Conclusion

Egypt holds one-quarter of the world’s Arabic-speaking population. Despite this, the majority of neuropsychological tests used for assessing cognitive impairment have not been properly standardised, normed and validated according to ITC guidelines for use in an Egyptian population. This problem can lead to devastating outcomes, as the prevalence of dementia rises in Egypt and other low- and middle-income countries. The results of a survey of conference delegates who convened to discuss the topic showed that Egyptian practitioners were very much in favour of conducting research to establish norms, validate tests and promote cultural adaptation of the Western-made assessments now used.

Data availability

The research materials and data-set collected for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs Eman Nabil, Operations Manager, and Ms Asmaa Elnagar, Research Associate, for providing analysis support in preparing the manuscript.

Author contributions

Jac. B. and Jam. B.: conceptualisation, survey development, administration, writing, data analysis and table and figure development. Z.N.: writing and editing. N.L.: editing. K.B.: references and table and figure development.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

N.L. is a member of the BJPsych International editorial board and did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.