Introduction

The development and implementation of social housing policy in Brazil is a topic of critical importance, as it concerns a pressing issue that affects a substantial segment of the population and is reflected in a persistent housing deficit. The trajectory of this social policy has been marked by discontinuous and often contradictory developments, which have compromised its overall effectiveness and sustainability.

The literature on housing policy in Brazil is already extensive and has expanded significantly in recent years. However, its articulation with broader social policy has received relatively little attention – unlike in other areas, such as studies examining programmes like Bolsa Família. This article seeks to address that gap. By exploring the influence of market and financial forces, as well as the process of housing financialisation, the paper aims to highlight the aspects that characterize and distinguish the housing field from other domains of the welfare state.

Brazil faces a significant housing deficit. Although the country has gained prominence for the development of social policies, housing has assumed an increasingly central role within this framework. Despite the fact that Brazilian legislation – most notably the 1988 Constitution – has long recognised housing as a matter of social interest, the implementation of policies has not always aligned with this principle. Furthermore, the housing programmes adopted over the years have been marked by different approaches and strategies, as illustrated by the contrasts between the Minha Casa, Minha Vida (My House, My Life Program – MCMV) and the more recent Casa Verde e Amarela (Green and Yellow House Program – CVA). This trajectory, characterised by unstable guidelines and divergent policy orientations, has exacerbated the challenges of housing access, particularly for the most vulnerable populations, who are the primary intended beneficiaries of social housing.

The MCMV marked Brazil’s largest housing initiative, combining substantial public subsidies with the formalisation of informal housing. While expanding access to homeownership, MCMV also intensified the commodification of housing and facilitated the incursion of financial capital into low-income real estate markets (Pereira, Reference Pereira2017). This emerging housing production model in Brazil reflects a broader global trend under advanced capitalism, prioritising exchange value over use-value. It has reshaped relations between the State, private developers, and financial actors – intensifying social housing financialisation. Similar patterns are evident across Latin America, where market-driven approaches dominate housing policy. Financialised housing has rapidly expanded in the Global South, deepening debt and commodification among lower-middle-income groups. In response, social movements in Mexico and Brazil have mobilised to resist these dynamics, advocating for housing justice and the de-financialisation of urban life (Basile and Reyes, Reference Basile and Reyes2025).

Access to adequate housing has long represented a major challenge for a significant portion of the Brazilian population. In 2019, the national housing deficit was estimated at 5.9 million households (FJP, 2021). Since the introduction of the National Housing Plan in 2009, Brazil has implemented the MCMV, which has supported the construction of approximately 4.5 million housing units for low-income families. Large-scale housing developments have frequently resulted in substantial environmental impacts (CODEPLAN, 2020). These outcomes highlight the urgent need for a more integrated and holistic approach to social housing policy – one that fully embeds principles of sustainability. The rapid and late urbanisation of Latin America, outpaced infrastructure development and led to widespread deficiencies in environmental sanitation. Unlike earlier, more gradual urban transitions in Europe and the U.S., Latin America’s accelerated process resulted in inadequate housing and limited access to basic services such as clean water, sewage, and waste management, exposing populations to serious health risks (Johansen et al., 2013).

The development of social housing and its intersection with environmental issues are of particular significance in the context of the Federal District of Brasília (FDB). The FDB is entirely located within the Cerrado biome, the second largest in South America, covering over 200 million hectares. In recent decades, rapid population growth and intensified economic activity have placed increasing pressure on water resources, threatening their preservation and sustainability. It is also recognised as the world’s most biodiverse savanna, a status that, combined with the high risk of habitat loss, has led to its classification as a global biodiversity hotspot (IPDF, 2020). The development of social housing in this region presents numerous challenges, making it a particularly significant case study. The FDB also possesses unique characteristics that render it both emblematic and representative of broader socio-spatial and environmental dynamics. Brasília – the capital of the country, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2010, is internationally recognised for its distinctive modernist urban design. Conceived by urban planner Lúcio Costa and architect Oscar Niemeyer, the city was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Urban growth in Brazil unfolds amid pronounced socio-spatial segregation. Well-serviced central areas drive up land values, displacing low-income populations to peripheral or environmentally vulnerable zones with inadequate infrastructure, further undermining their quality of life (Mesquita and Kós, Reference Mesquita and Kós2017). Recent transformations in Brazil’s social housing policy – and their environmental implications, particularly regarding sustainability – have become increasingly relevant to contemporary debates in social policy. Housing, especially social housing, is now frequently situated within the broader framework of eco-social policies, given its intersection with climate change (Bohnenberger, Reference Bohnenberger2023). Social policy scholarship argues that climate change constitutes an emergent social risk, prompting a shift from the traditional welfare state towards an “eco-state” (Jakobsson et al., Reference Jakobsson, Muttarak and Schoyen2018). Eco-social policies, therefore, emerge as a promising avenue for integrating environmental sustainability with social justice (Johansson and Koch, Reference Johansson and Koch2020).

The past two decades have witnessed profound changes with significant global impacts, particularly in Latin America. Social policy has played a fundamental role in shaping these societies. The effects of multiple crises – social, economic, financial, and environmental – on contemporary societies underscore the relevance of discussing Latin America in relation to the future of social policies at a global level. In this context, the sustainability emerges as a pressing issue, highlighting its critical importance for the development of these policies.

This paper discusses the research question: in what ways do recent trends in social housing development in Brazil shape the direction of social policy?

This article unpacks the multiple levels involved in the policymaking and implementation of social housing, considering the perspectives of various social actors, including political and administrative agents. In doing so, it sheds light on a key domain of social policy and its interrelationships with housing policy. The structure of the paper is organised as follows: initially, an introduction to the topic is presented, followed by an analysis of the key legislative milestones related to social housing. Subsequently, a literature review is conducted, highlighting the main contributions in the field of social housing policy. The methodology employed in this research is then described in detail in the results, the main findings from the interviews conducted with social actors involved in social housing in the FDB are analysed. Finally, in the discussion and conclusion sections, the study’s key conclusions are presented, and the implications for the development of eco-social policies and the strengthening of a sustainable welfare state are discussed.

The development of social housing in Brazil over the last two decades

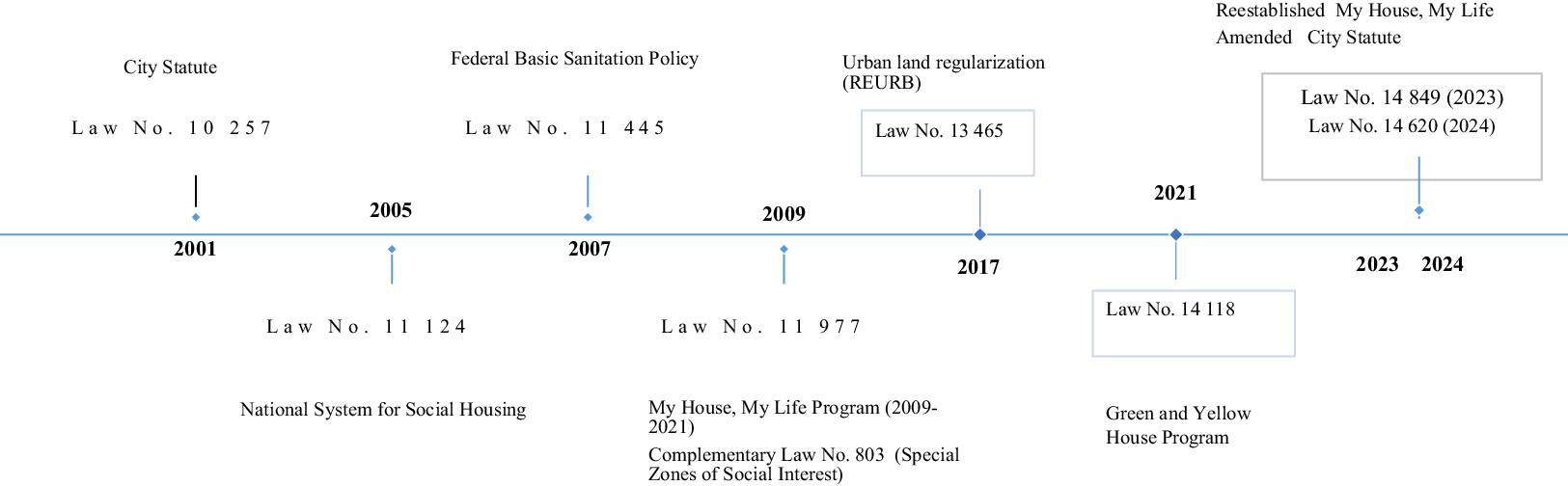

The development of social housing in Brazil over the past two decades can be traced through key milestones in land use planning, sanitation, and environmental policy. Its foundations lie in the 1988 Federal Constitution – the “Citizen Constitution” – which enshrines the right to housing as a fundamental social right. Contemporary housing policy emerged in the early twenty-first century with the enactment of the City Statute (Law No. 10,257/2001) and the establishment of the Ministry of Cities in 2003 (Nascimento Neto and Arreortua, Reference Nascimento Neto and Arreortua2019) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Timeline of legislation of social housing development.

City statute

This analysis begins with the 2001 City Statute (Law No. 10.257), enacted during Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s presidency. This landmark legislation establishes public order and social interest norms to regulate urban property use for the common good, public safety, citizen well-being, and environmental balance. Central to the law is the right to sustainable cities, encompassing access to land, housing, sanitation, infrastructure, transport, services, employment, and leisure for present and future generations – an explicit recognition of sustainability as a guiding principle. The statute operationalises Articles 182 and 183 of the 1988 Constitution, outlining general guidelines for urban policy to ensure cities fulfil their social functions and uphold the right to adequate housing (Lima et al., 2022).

National system for social housing

Law No. 11,124 of 2005 established the National System for Social Housing with the aim of facilitating access to serviced land and to adequate and sustainable housing for low-income populations. However, the commodification of social housing has disproportionately benefited the middle and upper classes, as well as the real estate sector, rather than the majority of the population experiencing housing shortages (Ronald et al., Reference Ronald, Lennartz and Kadi2017; Mosciaro and Aalbers, Reference Mosciaro and Aalbers2020).

Sanitation and environment

The Federal Basic Sanitation Policy was established in the presidency of Lula da Silva by Law No. 11,445 in 2007 and updated by Law No. 14,026 on July 15, 2020. This policy aims to universalize access to potable water and sewage collection and treatment for the entire population. According to this law, public sanitation services must be provided based on the principle of universal access, ensuring that everyone has the right to these essential services. The current legislation sets specific goals to achieve universal access to these services by 2033, requiring that 99% of the Brazilian population have access to treated water and 90% have access to sewage collection and treatment.

Special zones of social interest in the Federal District of Brasilia

The Federal District of Brasília has established and regulated Special Zones of Social Interest (ZEIS) through its Territorial Planning Master Plan, enacted under Complementary Law No. 803 of 2009. This plan consolidates a legal framework rooted in the principles of the right to the city and the social function of property, aiming to ensure fair and equitable access to urban benefits. According to this principle, urban property must serve the collective interest and comply with planning regulations (Ondetti, Reference Ondetti2016; Stefanello & Pagliarini, 2011). Within this framework, legal instruments for urban management have been developed to promote the sustainable and appropriate use of urban land, including compulsory subdivision, building, and utilisation requirements that oblige property owners to assign a social function to their holdings, under penalty of sanctions such as increased taxation.

My house, my life program

During President Lula’s administration, housing policy was expanded with Law No. 11,977 of 2009, which established the MCMV Program, one of the largest social housing initiatives in Latin America, aiming to reduce the housing deficit and ensure access to housing for low-income families. This programme provided direct subsidies, facilitated access to credit, and was theoretically targeted at families with incomes of up to three minimum wages (track 1). However, despite the extensive provision of housing units throughout its duration, studies indicate that, in practice, Track 1 was the least benefited.

Urban land regularisation (REURB)

Law No. 13,465 of 2017 defines REURB – Urban land regularisation – as a set of legal, urban, environmental, and social measures aimed at incorporating informal urban settlements into urban territorial planning and granting titles to their occupants. REURB-S, or Social Interest Land Regularization, specifically applies to informal urban settlements predominantly occupied by low-income populations.

Green and yellow house program

In 2021, during President Bolsonaro’s administration, the Green and Yellow House Program (Programa Casa Verde e Amarela – CVA) was created through Law 14,118 of 2021. In the same year, the federal government established CVA Program discontinued the MCMV Program, and reduced funding allocated to social housing by over 93%. This programme significantly reduced resources allocated to social housing financing. The established goal was to provide housing financing for 1.6 million low-income families by 2024. The programme encouraged the financialisation of housing, promoting homeownership and expanding credit access for low-income families. The dream of owning a home became central to the narrative of this new programme.

Recent developments

In 2023, the Ministry of Cities resumed its functions, marking the federal government’s renewed centrality in integrated urban planning. The current approach prioritises the expansion of social housing, integrating it with urban mobility and the sustainability of housing initiatives. Notably, the planned revision of the City Statute in 2024 seeks to modernise land use and spatial planning regulations, thereby facilitating the provision of affordable housing within consolidated urban areas. Nonetheless, despite these legislative developments, structural inequalities continue to hinder access to housing across Latin America (Maniglio and Casado, Reference Maniglio and Casado2022), with Brazil exhibiting particularly acute disparities.

Law No. 14,849 of 2024 amended Law No. 10,257 of 2001 (the City Statute) to make the inclusion of urban mobility analysis mandatory in preliminary neighbourhood impact studies. Meanwhile, Law No. 14,620 of 2023 reinstated the MCMV Program and ended the exclusive role of Caixa Econômica Federal as its sole operator. With this change, private banks, digital financial institutions, and credit cooperatives became eligible to participate in the programme’s implementation. As Ferraz (Reference Ferraz2022) reports, focusing solely on legal texts provides a limited understanding of how constitutional ideas influence society. While laws carry symbolic significance, their actual impact depends on political, economic, and cultural contexts.

Literature review

Since the early 2000s, Latin American countries have experienced a profound transformation in social policy. Access, coverage, and benefit levels expanded significantly across various sectors (Altman and Castiglioni, Reference Altman and Castiglioni2019). In Brazil, an unprecedented alignment between the state, the financial sector, and the construction industry allowed large firms and developers to enter housing markets that had previously been beyond their reach. This model – driven by an industrial-financial consortium – combined substantial public subsidies, parastatal funding, and private capital. It was reinforced by legal and institutional safeguards and sustained by state-backed expansion of consumer credit (Shimbo, Reference Shimbo2019).

Housing in Latin America has sparked significant debates about the commodification and financialisation of the sector (Botega, Reference Botega2008; Valença and Bonates, Reference Valença and Bonates2010; Monteiro, Reference Monteiro2015; Fuller, Reference Fuller2019), with direct impacts on the fundamental right to adequate housing (Soares, Reference Soares2017). In this context, institutional arrangements and the discretionary power of public administration are identified as factors that hinder the effectiveness of housing policies (Nascimento Neto and Arreortua, Reference Nascimento Neto and Arreortua2019), contributing to economic instability, increased inequality, and the emergence of negative externalities in social policies (Fuller, Reference Fuller2019).

Extensive state investment in the private construction sector, aimed at stimulating the economy and generating employment, has not guaranteed equitable access to social housing. This approach mirrors the developmentalist housing policy of the military regime, which prioritised the real estate market at the expense of broader social interests (Rolnik and Nakano, Reference Rolnik and Nakano2009; de Sampaio Jr, Reference de Sampaio2012; Lima, Reference Lima2018). Consequently, even during its most progressive phase of neo developmentalism (2003–2016), Brazil’s social housing policy failed to fully align with the principles of public policy for social equity.

Statistics on the housing deficit in the Federal District of Brasília reveal that low-income and vulnerable populations account for approximately 83% of this deficit. For those excluded from access to housing programmes, the options are often limited to peripheral settlements or homelessness (Walker et al., Reference Pimentel Walker, de Alarcón, Santo Amore, Lopes dos Reis, Rajkumar Nair, Yelk and Liu2021).

Financialisation

The asset-based welfare state has shaped the logic of housing finance since the establishment of the housing finance system (Ronald et al., Reference Ronald, Lennartz and Kadi2017; Mosciaro and Aalbers, Reference Mosciaro and Aalbers2020). The use of workers’ savings to subsidise housing production has disproportionately benefited the middle and upper classes, as well as the real estate sector, to the detriment of most of the population experiencing a real housing deficit. Globally, the asset-based welfare state has proven ineffective in improving the living conditions of impoverished populations (Mosciaro and Aalbers, Reference Mosciaro and Aalbers2020). On the other hand, this model cannot be considered inherently corrupt, even though it diverts resources from the poor majority to sustain the commodification and financialisation of housing. However, social injustice is intrinsic to it, as it excludes from the right to adequate housing those already marginalised by the formal labour market and those experiencing homelessness (Mosciaro and Aalbers, Reference Mosciaro and Aalbers2020). Neoliberalism is historically specific and inherently diverse in its forms (Saad-Filho, Reference Saad-Filho2020), and the sociopolitical framework that transforms social housing into a commodity has been shaped by various nuances of this ideology.

Housing policy in Brazil has prioritised the economic-financial aspects of housing over its role as a social good and fundamental human right (Bonduki, Reference Bonduki2008; Shimbo, 2010; Cardoso et al., 2011; Ferreira et al., 2019; de Camargo, Reference de Camargo2020). Since 2005, the National Housing Policy has reflected a synthesis of neoliberalism and the Workers’ Party’s social democratic economic framework. This convergence positioned the private sector as the primary driver of economic growth policies, consequently distorting the original objectives of social housing programmes (Lima, Reference Lima2018).

Housing policy in Brazil has historically been, and remains, driven by market forces, albeit financed predominantly by workers’ resources, such as the Severance Indemnity Fund (Pimentel Walker et al., Reference Pimentel Walker, de Alarcón, Santo Amore, Lopes dos Reis, Rajkumar Nair, Yelk and Liu2021; Falchetti, 2020; de Ru Reference de Russo2016; Cardoso et al., 2011).

Implementation of housing policy

The case of the FDB, one of the most significant political and economic decision-making hubs in Latin America, reveals speculative and land-grabbing characteristics within the belief systems and interest-defence mechanisms of political coalitions observed in the structuring of territorial governance (Vicente et al., Reference Vicente, Calmon and Araújo2017). Through the lens of the advocacy coalition framework (Cairney, 2019; Weible et al., Reference Weible, Sabatier and McQueen2009), this territorial management policy is rooted in the ideology of private interest, shaping institutional arrangements under the influence of policy brokers and the manipulation of the sovereign decision-maker’s discretion.

Under the aegis of discretion, strategies devoid of technical and budgetary induction mechanisms are adopted to promote planning and management actions for the provision of social housing in territories characterised by complex urban dynamics. In essence, the actions of planning, executing, and managing housing policy are inefficient (de França, Reference de França2015).

The implementation of social policies has gained increasing prominence in the scientific analysis of the Brazilian case. Recent studies in other areas of social policy, such as poverty alleviation, have revealed that this process has also been characterised by commodification. This is the central argument of Georges (Reference Georges2024), who examined the implementation of social policies in São Paulo, Brazil, during the 2000s, concluding that these policies exemplify the commodification of poverty. The study demonstrates how market logics and processes of privatisation have reshaped social protection within a broader context of expanding labour informalisation.

My house, my life program

Despite the broad scope of social policy analysis, housing is often overlooked, even after the launch of the MCMV which brought international visibility to the issue. The development of social housing in Brazil, particularly in the last two decades, represents a significant case for the study of social policies. The implementation of housing policies is shaped by multiple factors, and a detailed analysis of these elements helps to understand their comprehensive influence on social policy.

The interaction between the State, businesses, and the strong influence of the financial market on the MCMV, has been widely criticised (Cardoso et al., 2011). The real interests and the mercantilist or social foundations of the programme are subject to intense questioning. The literature indicates that social housing policy alone does not present a viable solution for mitigating the effects of poverty in Latin America, as the housing supply is insufficient (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2014). Furthermore, the programme’s social outcomes have not driven the necessary urban transformations; on the contrary, they have contributed to the perpetuation of urban planning issues (Nascimento and Tostes, Reference Nascimento and Tostes2011). The “social interest” underlying the housing policy focused on the MCMV is often interpreted as market-driven interest (Balbim et al., Reference Balbim, Krause and Lima Neto2015; de Camargo, Reference de Camargo2020). Over the past two decades, Brazilian housing policy has focused on the MCMV, linked to the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), launched in 2007.

With a strategy aimed at promoting economic growth, job creation, and improving living conditions for the population in priority areas such as infrastructure, sanitation, housing, transportation, energy, and water resources, the programme exhibits a financialised nature that generates socially undesirable externalities due to the incompatibility between social interests and the pursuit of profitability (Cardoso and Leal, Reference Cardoso and Leal2010; Valença Reference Valença, Fernandez and Alfonsin2014). Sociological analysis highlights the influence of publicly traded real estate developers on housing policies (Shimbo et al., Reference Shimbo, Bardet and Baravelli2022).

Historically, the state and local governments have played a central role in facilitating and promoting capital circulation, serving as the driving force behind most physical transformations in the built environment through specific professional practices. In this context, the MCMV program brought together public and private elites around financial objectives (Shimbo et al., Reference Shimbo, Bardet and Baravelli2022). This resulted in the consolidation of an alignment between the interests of the national economic elite and foreign investors, driven by profit, and public administrators, driven by power control. Within the realm of social policies, this alignment generates a conflict of interest to some extent, as the logic of financialisation is rooted in profit, while the core of social interest lies in the well-being of the population.

Green and yellow house program

In 2020, the Bolsonaro administration introduced the Green and Yellow House Program (Casa Verde e Amarela – CVA) to replace the MCMV. The CVA allocated insufficient funding for completing ongoing housing projects for the lowest-income group. Instead, its primary focus is on promoting land and housing regularisation to integrate informal settlements into the real estate market. By allowing private actors to set land prices, the programme risks excluding low-income populations. Moreover, the state’s role in land titling is significantly reduced, with CVA channelling public funds to private companies to manage the regularisation process.

Sustainable welfare state and eco-social policy

The discussion on sustainable welfare has emerged relatively recently, emphasising a redefinition of welfare and well-being from an ecological perspective, rooted in human needs and planetary boundaries (Koch and Mont, Reference Koch and Mont2016; Gough, Reference Gough2017). Sustainable welfare refers to a welfare or social policy system designed to meet human needs while respecting planetary boundaries (Büchs, Reference Büchs2021). Coupled with global eco-social policies, it aims to safeguard vulnerable groups (Gough, Reference Gough2013; Kaasch Reference Kaasch, Wulfgramm, Bieber and Leibfried2016; Kaasch and Waltrup, Reference Kaasch and Waltrup2021; Lindellee et al., Reference Lindellee, Alkan Olsson and Koch2021). This approach presents sustainable welfare as an alternative framework for welfare provision and policy development, aligning social goals with ecological imperatives.

The literature on eco-social policy has expanded rapidly, reflecting the need to address ecological and social challenges in an integrated manner. Such integration is motivated by the concern that poorly designed environmental policies may disproportionately impact disadvantaged groups (Laruffa, Reference Laruffa2024). Eco-social policies, defined by Mandelli (Reference Mandelli2022) as public interventions pursuing social and environmental objectives jointly, differ from traditional social policies by focusing on formerly peripheral welfare domains – such as energy, transport, housing, and food – and by aligning social welfare with environmental goals.

Bohnenberger (Reference Bohnenberger2023), in a systematic literature review, highlights housing as key domain where eco-social policies are increasingly advocated due to their dual relevance: they are critical to achieving climate objectives and have direct, immediate impacts on households. The social housing is playing an important role in Brazil, due to the necessity of its expansion. Currently, many residential projects perform poorly in terms of energy efficiency and thermal comfort. In addition, the impact of climate change on energy consumption may aggravate the energy scenario, increasing the dependence on the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (Cruz and Da Cunha, Reference Cruz and Da Cunha2021). Most MCMV projects do not incorporate energy-efficient measures, which are typically perceived by developers as cost-increasing rather than value-enhancing (Mesquita and Kós, Reference Mesquita and Kós2017).

Despite the progress observed in Europe and some specific countries, these approaches have seen more limited development in Latin America. However, Brazil presents significant potential for advancing these perspectives (Pedrosa and Xerez, Reference Pedrosa and Xerez2023). These approaches are essential for understanding and tackling the contemporary challenges faced by these countries, which require integrated solutions capable of articulating social, economic, and political dimensions, as proposed by the vision of the sustainable welfare state and eco-social policies.

Data and methods

The analysis of legislation involved identifying key legal frameworks developed over the past decade, followed by a detailed examination of the most relevant documents related to the implementation of social housing policy in Brazil. The results of this analysis were presented at the beginning of the article.

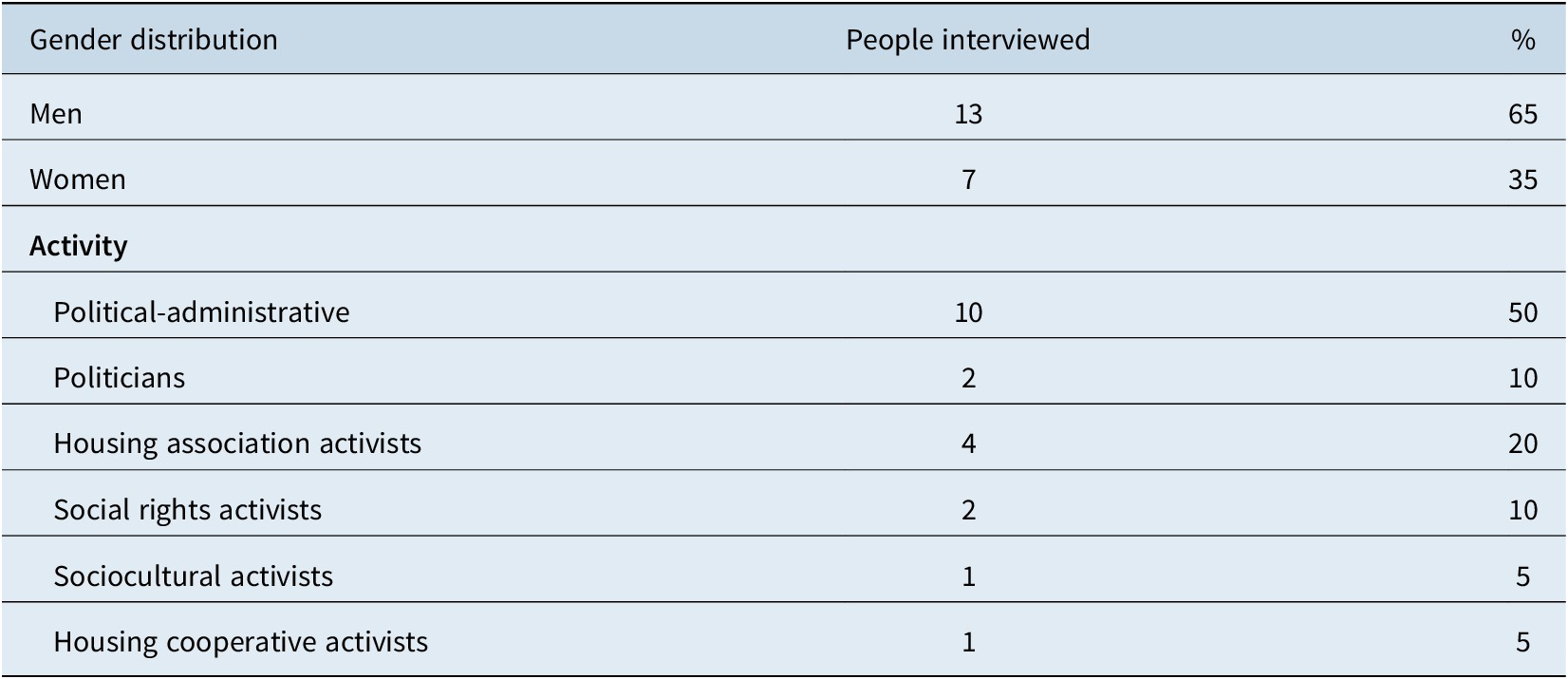

This research employs qualitative methods, specifically semi-structured interviews. A total of 20 interviews were conducted between June and September 2021. The participants were individuals involved in the coordination of the social housing sector between 2000 and 2020. The recruitment process was carried out in three phases. First, potential participants were identified, and invitations were sent to the communication offices of relevant institutions, requesting them to nominate administrative staff members willing to volunteer for the interviews. In the second phase, 16 formal, personalised invitations were sent via email and WhatsApp. Out of these, 12 participants accepted and completed the interviews, all of whom were political-administrative actors. In the final phase, 311 entities were contacted via email, resulting in five representatives from associations and cooperatives agreeing to participate.

All participants voluntarily agreed to be interviewed and were encouraged to freely share their experiences and perceptions of social housing in the Federal District of Brasilia. In total, 12 interviews were conducted with political-administrative actors (individuals holding public office of a political nature), five with representatives of associations and cooperatives, and three with activists from social movements (leaders of social movements committed to the defence and promotion of social rights) (see Table 1). Only one interview was conducted in person at the request of the interviewee. The average interview duration was 74.95 minutes. This methodological approach was chosen to capture the insights of actors with expertise in social housing processes and the perspectives of social movement activists.

Table 1. Sample characterisation

The semi-structured interviews involved 20 participants, whose distribution shows sociodemographic diversity in terms of gender, age group, and activity, providing a valuable database of almost 25 hours of recordings and over 226,000 transcribed words. Regarding gender, there is a predominance of men (65%, n = 13), with a percentage of women (n = 7) in the sample. Age analysis reveals that the majority of interviewees are over 50 years old (55%, n = 11), followed by the 35–50 age group (45%, n = 9). In the field of social activity, there is also a significant diversity: 50% (n = 10) of the interviewees are political and administrative actors, including public managers and politicians. 20% (n = 4) are housing association activists; 10% (n = 2) are social rights activists; 5% (n = 1) are sociocultural activists; 5% (n = 1) are housing cooperative activists; and 10% (n = 2) are political activists.

Due to restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, most interviews were conducted via videoconferencing. The first three interviews were transcribed using traditional audio recording methods, while the remaining interviews were transcribed using the Microsoft Word transcription tool available on the Office 365 platform.

The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical norms of University of Lisbon and procedures of scientific investigation, including adherence to ethical codes and compliance with anonymity and confidentiality requirements. All interviewees provided their informed consent in writing. The interviews were recorded and transcribed, and their content was analysed, with the main findings presented below.

Findings

Implementation of the social housing policy

An analysis of the implementation of the social housing policy in the Federal District of Brasília reveals, based on the perspectives of social actors, that this policy encounters significant challenges. Among the primary obstacles identified is the discontinuity of governmental actions, marked by the interruption and abandonment of initiatives with each change in administration. Social housing is shaped by complex urban dynamics, which have increasingly undermined its effectiveness and efficiency (de França, Reference de França2015; Vicente et al., Reference Vicente, Calmon and Araújo2017). This lack of continuity undermines administrative consistency, as emphasised by the interviewees:

(…) previous governments fail to continue the processes that were initiated. (I18, Political-administrative).

(…) it works like this: one government comes in and starts a project; then it leaves, and the next government, unfortunately, does not carry forward the work of its predecessor… (I20, Housing cooperative activists).

The high turnover of leadership and frequent changes in institutional arrangements and guidelines create a vicious cycle that undermines the effectiveness of housing policies. This discontinuity also reveals the influence of economic and financial power over state structures. The dominance of financial interests in political decision-making is significant, leading to the implementation of policies driven by these interests at the expense of the social needs of the population. The interviewees provide compelling accounts of how political campaign financing can impact even the choice of locations for social housing construction, as illustrated by the following statements, by interviewees 6 and 9 (Political-administrative):

(…) major real estate developers shape public decisions, prioritizing financial interests over social considerations. (I6, Political-administrative)

This interview’s perspective aligns with previous research, such as Carvalho et al. (Reference Carvalho, Sauerbronn, Haslam and Denedo2025), which reports that the housing construction model has notably reshaped the relationships between private construction companies, the state, and financial actors through a logic centred on maximising returns and profitability. In this context, the right to adequate housing for vulnerable and low-income populations is undermined.

The government, as a temporary authority, is subordinated to financial power, [which] funds their campaigns, you know! And it certainly ends up influencing decisions, including the choice of where these housing projects will be built…. (I9, Political-administrative)

My house, my life program (MCMV)

Another phenomenon that undermines the effectiveness of social housing policy is the logic of commodification, which fundamentally involves the financialisation of social housing, transforming the right to housing into a profit-oriented commodity. Regarding the practical application of this policy, the interviews highlight, for example:

(…) the requirement to contract construction companies for the financing of social housing has undermined self-construction and excluded many people in need. (I16, Political-administrative)

Commodification and financialisation of housing

The processes linked to this logic not only hinder access to housing for the most vulnerable populations but also create barriers for social movements and housing cooperatives. In this context, although legislation promotes mechanisms of inclusion through participatory councils in social policies, in practice, it reveals the fragility of institutional arrangements. Social participation faces restrictions imposed by this model, as expressed in the interview:

The role of the association is merely to act as an intermediary between the member and the financier. (I14, Housing association activists)

Effective social participation highlights the absence of civil society leadership in the decision-making process, as the state aligns itself with the private sector to speculate and profit from social housing, disregarding applicable legislation and actual housing needs. This alignment is illustrated by the statement of interviewee.

(…) the MCMV provided access to financing, you know! Through companies that redirected their investment focus to social housing, which also expanded the social housing market. (I8, Political-administrative)

The interview data suggest the relevance of commodification and financialisation aspects of this programme, which have become more significant than the social interest aspects of housing (Balbim et al., Reference Balbim, Krause and Lima Neto2015; de Camargo, Reference de Camargo2020).

The perceptions of social actors suggest that the development and implementation of the social housing in the FDB follow the patterns of capitalism. Despite regional specificities, this dynamic is comparable to the social housing policies implemented across Brazil and Latin America, shaped by the neoliberal that dominates the political economy of capitalism’s peripheries.

The interview data suggest the relevance of the financialisation process in Brazil’s social housing sector (Ronald et al., Reference Ronald, Lennartz and Kadi2017; Mosciaro and Aalbers, Reference Mosciaro and Aalbers2020; Saad-Filho, Reference Saad-Filho2020). Carvalho et al. (Reference Carvalho, Sauerbronn, Haslam and Denedo2025) argue, as also expressed by several interviewees, that social housing responses are shaped by a process of financialisation that primarily benefits the upper urban circuit while exacerbating inequalities in the lower circuit, displacing vulnerable residents without guaranteeing adequate housing alternatives.

A range of factors impacts the effectiveness of social housing policy, particularly planning, governance, and the alignment of political and social interests. However, the neoliberal market-oriented ideology fosters a bureaucracy characterised by discontinuities and frequent changes in norms, rules, and procedures, prioritising private interests over public housing policy as established by legislation and the Constitution. This is illustrated in the following excerpt:

(…) in practice, social housing policy does not reflect what is stated in the laws and the Constitution. (I19, Housing cooperative activist)

Socioeconomic inequality in Latin America represents the most significant challenge to social policy. Housing programmes intended to serve the most impoverished segments of society often end up benefiting middle- and upper-class groups. This is a well-established point in both academic literature and the perspectives of social actors, particularly regarding the MCMV program. For instance, referring to a Public-Private Partnership project in the FDB:

(…) the lists were dominated by middle-class individuals, leaving the poorest marginalized. (I7, Political-administrative)

Such distortions contribute to social exclusion and urban segregation, undermining universal access to adequate housing. As Lopes et al. (Reference Lopes, Figueiredo, Gil and Trigueiro2023) note, efforts to reduce housing deficits have expanded globally; however, many policies, particularly in the Global South, are criticised for overlooking the spatial distribution of new housing. The following interview excerpt illustrates the challenges associated with implementing housing policies in Brazil:

(…) the truth is, there is no lack of resources; the problem is the lack of prioritisation in addressing social demands. (I10, Political-administrative)

The entanglement of political action with economic and financial interests, dependence on private financing, and mismanagement of public funds severely hinder the implementation of social policies, particularly social housing policy. This challenge is heightened because its primary resource – land – is the most valuable asset in Brazil’s capital market.

These findings align with those of previous studies (Ronald et al., Reference Ronald, Lennartz and Kadi2017; Lima, Reference Lima2018; Mosciaro and Aalbers, Reference Mosciaro and Aalbers2020; Saad-Filho, Reference Saad-Filho2020).

Implementation difficulties: Shortage of civil servants

Interviewee 1 highlights that the shortage of civil servants at the Federal District Housing Company impacts the continuity of social housing efforts:

We still don’t have our own staff, and, due to the pandemic, there was a public selection process, but we couldn’t appoint anyone because… I think it’s Law 173, a federal supplementary law; Bolsonaro, as president… froze and prevented hiring, so we have a selection waiting to appoint… the lack of a permanent team… causes the entire company to change every 4 years, erasing its institutional memory. (I1, Political-administrative)

The shortage of professionals working in the field of social housing has worsened in recent years, emerging as an increasingly pressing issue. The findings of this study are particularly relevant, having been corroborated by several interviewees, as evidenced in the excerpts analysed. The results of our research are significant insofar as they contribute to a deeper understanding of the challenges associated with the implementation of social policies.

The shortage of civil servants impacting the execution of social housing was also mentioned in other interviews (I7, I9, I10, Political-administrative) by different interviewees.

Sustainability, land use, and occupation

The FDB holds a significant portion of public lands, making land ownership a central issue for social housing policies. The management of this asset is frequently associated with speculative interests driven by market logic, as highlighted in the following interview excerpt.

(…) The public company responsible for managing public lands maintains a land bank that serves real estate capital (…) profit-driven factors condition social action, both by society and the State. (I6, Political-administrative)

The issue of land is also at the core of institutional arrangements. In the Federal District, the dynamics by which economic elites control the land market and co-opt the State through institutions such as public companies intensify land speculation while neglecting the social function of land. This structure restricts access to housing for impoverished populations, while prioritising the interests of middle- and upper-class groups. In this context, the alignment of state structures with land commodification exacerbates problems such as land grabbing and irregular subdivisions, directly undermining environmental sustainability. Environmental sustainability is further compromised by the lack of integrated planning and basic infrastructure in irregularly occupied areas, as illustrated in the following excerpt:

(…) the government offers areas for social housing without resolving the issue of land ownership or implementing measures to mitigate environmental damage. (I19, Housing cooperative activists)

This approach fails to ensure that land fulfils its social function, as mandated by the Federal Constitution. In addressing environmental issues related to land use and occupation, the role of social activism and cooperativism stands out for promoting alternative and more sustainable actions. As noted in one interview:

Self-construction was one of the most effective strategies to meet the needs of the poorest. (I4, Political-administrative)

These strategies, which demonstrate the effectiveness of collaboration between civil society and the State in achieving inclusive and participatory solutions, have been progressively abandoned in favour of less sustainable political and financial options.

Environmental issues play a critical role in social housing in Brazil. Although legislation addresses these aspects, the implementation of housing policies has failed to effectively incorporate them. Challenges related to basic sanitation, noncompliance with environmental standards, poverty, precarious housing conditions, and the ongoing environmental crisis exacerbate this scenario, placing Brazil among the countries most affected by these issues. The close interrelation between social housing, the environment, and sustainability emerges as one of the most significant findings of this study, several interviewees emphasised the importance of these dimensions. While some results are consistent with prior research that has recognised the centrality of these issues – particularly in the context of social housing programmes such as MCMV and CVA (Mesquita and Kós, Reference Mesquita and Kós2017) – this study also introduces new empirical insights that highlight the role of social housing within broader eco-social policy frameworks. Especially noteworthy are the findings pertaining to the Brazilian context, which underscore the pioneering contribution of this article. These results are of even greater significance because eco-social policy, which reflects the need to address ecological and social challenges in an integrated manner, is driven by the concern that poorly designed environmental policies may disproportionately affect disadvantaged groups (Laruffa, Reference Laruffa2024).

In Latin America, these problems are particularly pronounced, underscoring the importance of robust and integrated social policies in local, regional, and global contexts. In this sense, the interplay between social, economic, and environmental dimensions highlights the essential role of eco-social policies in fostering well-being and sustainability.

The implementation of social housing policies in Brazil faces numerous challenges related to environmental and sustainability issues. These problems conflict with existing legislation, which mandates greater adherence to environmental protection principles. Environmental concerns are particularly significant in this context, as they generate negative consequences that jeopardize the well-being of both present and future generations. Nonetheless, these aspects have received limited attention within the scope of social housing policies. Scientific evidence on the relationship between social sustainability and housing policies is essential to inform debates on the implementation of housing policies in Brazil, a topic of great importance both in the Latin American context and from a global perspective (Koch and Mont, Reference Koch and Mont2016; Gough, Reference Gough2017; Büchs, Reference Büchs2021; Kaasch and Waltrup, Reference Kaasch and Waltrup2021; Lindellee et al., Reference Lindellee, Alkan Olsson and Koch2021).

The issues of sanitation and housing precariousness during the COVID-19 pandemic, along with the intervention by the Bolsonaro government, were highlighted by some interviewees. (I7, Political-administrative)

Interviewee 5 points to social inequalities and emphasizes sanitation issues and the precarious state of housing. They also condemn government actions that have worsened the crisis. These actions are part of the Federal District’s urban regularisation policy targeting social interest areas. In this case, the government’s urban regularisation efforts led to the demolition of a home, along with essential materials that the family depended on for their livelihood, as recounted in this interview.

Imagine… during COVID, having the opportunity to visit areas affected by evictions from public land and then coming across a situation where, in talking to the waste collectors, they said – ‘Federal District Legal [program]… knocked down our house. That was bad, but it was worse when they took all the trash we had collected, which is how I buy beans and rice for my family. They destroyed it all’. (I5, Political-administrative).

The challenges of precarious living conditions and inadequate sanitation were also raised by different interviewees. These issues significantly impact quality of life, which directly affects human dignity, as recommended by the United Nations and outlined in the Brazilian Constitution. The pandemic has further underscored the urgent need for adequate social housing, as reflected in the following statement:

The pandemic has made this clearer: look at how many people stopped getting the flu, stopped having dysentery… just by practicing hand hygiene, right? Providing a home with sewage, water, electricity, and proper roads improves people’s quality of life tremendously. (I07, Political-administrative).

Green and yellow house program (CVA)

The new national housing programme, CVA stands in stark contrast to the social housing initiatives previously implemented MCMV Interviewee 5 comments on this shift, stating:

CVA even distorted the concept of social interest! (I5, Political-administrative)

This complex scenario, marked by multiple crises, adds further challenges for actors and institutions involved in implementing and executing social housing. In the Federal District, unique conditions could potentially ease social housing management, as the state and municipal structures exist within a single legal entity, holding a significant portion of habitable land. Paradoxically, the barriers to delivering a more equitable right-to-housing policy are rooted in the very institutional framework responsible for managing social housing.

Anti-environmentalism has become a hallmark of Bolsonaro’s government, and several interviewees suggest similar neoliberal tendencies also impact social housing. Regarding the Urban Territorial Regularization Policy, interviewee 1 explains:

We face significant challenges due to legal issues and also political and economic interests that end up reshaping urban areas, which prevents… let’s say, sustainable growth. There’s no focus on the citizen. (I1, Political-administrative).

Political manipulation, he adds, often affects master and local plans that should ensure sustainable planning and environmental preservation.

Interviewee 2 reflects on past policies that failed to be implemented due to conflicting demands between different agencies:

Policies proposed by one agency were often not achievable by others. A clear example is the demands made by environmental bodies that, to this day, can’t be fulfilled by others, making it impossible to regularize the city. While unrealistic demands are made, society suffers, unable to move forward or backward. The requirements may be legal, but they must be achievable. If a demand will never be met, the problem will never be resolved. (I2, Politician)

The fine line between feasibility for social housing and legal environmental standards remains difficult to navigate, as legislation seeks to protect environmental sustainability, often clashing with the public’s social housing interests. According to interviewee 6, reflecting on the Roriz era (Governor of the Federal District, serving four terms from 1989 to 2006):

The legislative framework for environmental licensing and urban planning wasn’t as stringent then as it is now. Fercal [administrative region of the Brazilian Federal District] wouldn’t exist in its current form if it had to go through three stages of environmental licensing. (I6, Political-administrative).

Some interviewees view these evolving environmental standards as signs of growth and maturity in urban and territorial planning policies (I5, I8, I9, Political-administrative).

Interviewee 7 comments on the tension between environmental interests and the availability of land for social housing in Brasília:

Public lands in Brasília have beautiful, well-located areas close to highways and transportation infrastructure, available for low-cost development. But then interests get pulled in different directions, and environmental authorities don’t always help; it feels like they’re from another power altogether. (I7, Political-administrative)

Interviewee 8 partially agrees, adding that:

There are technical aspects and, unfortunately, also political issues to consider. Balancing private and public interests falls within the discretionary scope of Public Administration. (I8, Political-administrative)

Similarly, interviewee 9 points out how economic interests influence environmental decision-making:

The Environment Department is responsible for preserving all legally designated areas. But there seems to be an overlap between the responsibilities of the Housing and Environment Departments. Many times, land that could meet the social interest of people in need remains off-limits due to lobbying from large contractors. This often allows certain authorities, including environmental ones, to permit large development projects. (I9, Political-administrative)

Governments often use environmental concerns as a pretext to restrict public land from being used for social housing, while also bending these standards to favour large real estate developments. Interviewee 15 adds another perspective:

Often, the government – even beyond this administration – allocates areas without necessary environmental approval from IBRAM, leading to delays that wear down community associations. (I15, Political-administrative)

Allocating land for social housing without proper studies and licensing not only highlights private sector violations of environmental laws but also implicates the State itself. It reflects a lack of commitment to social housing and can serve as a tactic to politically manipulate vulnerable communities, as interviewee 11 emphasises:

The government’s role is often to wear people down, those already in extreme vulnerability, by dragging things out; they win through attrition and by rolling out delay tactics. (I11, Social rights activists)

The sentiments of interviewees 16, 19, and 4 (Political-administrative) align with this perspective.

Discussion

The findings of this research highlight the importance of social housing policy in Brazil within the broader debate on social policies, particularly in terms of implementation. The FDB faces ongoing conflicts over land use, as well as significant environmental challenges. These factors have often been overlooked in social housing projects, as evidenced by the programmes MCMV and, more recently, CVA. The transition from one programme to the other occurred in the context of a change in government and reflected profound shifts in the housing policy approach. The new programme revealed a weakening of financial support directed at low-income families, alongside a diminished emphasis on socio-environmental criteria. These changes underscore not only a discontinuity in public policies but also significant weaknesses in their implementation.

Additionally, the research points to bureaucratic hurdles and a shortage of human resources within public administration as further obstacles to the effectiveness of these policies. The growing financialisation of social housing also emerges as a critical issue, identified across the different contexts analysed. One of the key contributions of this study is the emergence of a new agenda that links social policy and environmental sustainability (Koch and Mont, Reference Koch and Mont2016; Gough, Reference Gough2017; Büchs, Reference Büchs2021; Kaasch and Waltrup, Reference Kaasch and Waltrup2021; Lindellee et al., Reference Lindellee, Alkan Olsson and Koch2021). Given the severe environmental challenges Brazil faces – including extreme temperatures, prolonged droughts, and flooding – the integration of environmental criteria into social housing construction is urgent, particularly because low-income families are the most vulnerable to such phenomena.

Our findings, derived from research conducted in Brazil’s Federal District of Brasília, are corroborated by recent studies undertaken in other Brazilian regions. Carvalho et al. (Reference Carvalho, Sauerbronn, Haslam and Denedo2025) suggest that the financialisation of social housing reinforces socio-spatial inequalities. These authors call for a re-evaluation of housing policies founded on principles of public accountability and social justice, and advocate for the advancement of counter-accounting practices designed to challenge the neoliberal housing model.

Although the data were collected in the FDB, the results may be applicable to other regions of Brazil and to other Latin American countries, where similar issues of urbanisation, inequality, and environmental crisis are at stake (Reyes & Basile, Reference Reyes and Basile2022).

Conclusion

The data analysed in this paper reveals that the development of social housing policy in Brazil over the past two decades is a topic still underexplored in social policy but of great interest. During this period, we have observed several highly significant events with both global and regional dimensions. Social housing, is commonly known in the country, plays a prominent role in social, economic, political, and environmental aspects. Although these issues have not received due attention over the years, they are of growing importance.

There is a noticeable discrepancy between the intended legislation – designating low-income individuals as the primary beneficiaries of social housing – and the reality, where, in some cases, these benefits have been directed toward more privileged groups. This situation suggests a possible lack of transparency and other irregularities that disproportionately affect the most vulnerable populations.

In recent years, two governments with distinct characteristics have implemented housing policies with different approaches. The MCMV program, created during Lula’s government, and the CVA program, introduced under Bolsonaro’s government, represent these differences and merit analysis. An examination of the main legislation has allowed the identification of various emerging aspects within these laws, with a special focus on the environmental dimension. Despite the deficiencies faced in this area, the environmental concerns expressed in the legislation are not always adequately addressed in the implementation of social housing projects. The interviews conducted highlight these gaps.

The data also reveal that sanitation is a highly relevant topic in the legislation, with numerous deficiencies, particularly in the social housing context. The financialisation of social housing, although little studied, is of great importance. The data in this article suggest a broad process of financialisation in social housing, particularly in supporting homeownership for low-income families. The participation of national and, especially, international financial institutions need to be further analysed and investigated.

The findings of this article reveal that policy discontinuity, clientelism, and other factors play crucial roles in the implementation of social policies. Over the past 20 years, the development of legislation in key areas has incorporated relevant aspects such as sustainability and the protection of the interests of present and future generations. However, the implementation of these policies has significantly diverged from their original design. In this context, Brazil and the Federal District exhibit characteristics that may provide generalisable insights for other Latin American countries and hold significant implications at the international level.

The findings provide practical insights into how recent trends in social housing development in Brazil shape social policy. They highlight the multi-level dynamics of policymaking and implementation, incorporating political and administrative perspectives, and reveal the interconnections between housing and social policy. Empirical evidence points to the commodification and financialisation of housing, gaps between law and practice, sustainability and land-use challenges, and policy discontinuities. These findings enhance understanding of the broader social and housing policy landscape and inform the design of new eco-social policies that address both social needs and planetary boundaries. The study provides original empirical insights into the role of social housing within broader eco-social policy frameworks. It highlights the interlinkages between social housing, environmental issues, and sustainability, with the Brazilian case offering a particularly distinctive and pioneering contribution. The discussion and conclusion emphasise the study’s main findings and explore their implications for advancing eco-social policies and reinforcing a sustainable welfare state.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to all interview participants, whose valuable contributions made this work possible. Appreciation is also extended to the Government of the Federal District of Brasília, whose data on social housing were essential to the development of this research. All views and analyses presented are the sole responsibility of the authors.