With democracies declining worldwide and a noticeable global shift towards autocracy, Reference Gorokhovskaia and Grothe1 understanding the impact of authoritarian regimes on citizen health is becoming increasingly important. Political repression is a defining characteristic of authoritarian regimes,Footnote a used to sustain rule, prevent popular rebellion and uphold established power structures. Reference Davenport2–Reference Peterson and Wahlström5 It refers to systematic repressive actions directed against individuals or groups, based on their current or potential involvement in non-institutional efforts for social, cultural or political change. Reference Peterson and Wahlström5 Beyond overt repression methods, such as imprisonment or torture, so-called soft or quiet political repression may serve as a powerful tool to maintain control while avoiding public attention to human rights violations. Soft repression involves less visible measures than overt physical violence, often operating beneath the threshold of criminal persecution. This includes surveillance, restrictions on freedom of speech or the deliberate creation of obstacles in private and professional life domains. These tactics can strip political opponents of time, money, security or allies – vital resources of resistance. Reference Earl6–Reference Yuen and Cheng9 As a result, an atmosphere of fear emerges where people hesitate to voice critical opinions, struggle to trust others and live in a constant state of self-policing and anticipatory anxiety. Reference Jämte and Ellefsen10,Reference Marheinecke, Strauss and Engert.11

One prominent example of soft repression were practices used in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR: 1949–1990), an authoritarian state in East Germany, closely linked to the Soviet Union and part of the Warsaw Pact. Targets included individuals, groups and organisations that perceivably worked subversively against the GDR, 12 including emigration applicants, artists, church groups, societal movements and youth subcultures. Reference Süß13 Frequently employed practices of soft repression were wiretapping, denunciation or provoking failures in professional and social domains, all of which were tailored to systematically undermine a (perceived) political opponent’s psychosocial integrity by inducing anxiety, panic, social isolation and confusion (for more detail, see Reference Marheinecke, Strauss and Engert.11 ). Soft repression typically does not fulfil the DSM-5 definition of a traumatic event. 14 Nevertheless, it fosters feelings of uncontrollability, social threat and uncertainty – core elements of psychosocial stress (for closer examination of soft repression as an extreme chronic psychosocial stressor, see Reference Marheinecke, Strauss and Engert.11 ). Evidence suggests that individuals exposed to soft repression in the GDR exhibit elevated rates of mental health disorders, particularly affective and anxiety disorders, later in life. Reference Spitzer, Ulrich, Plock, Mothes, Drescher and Gurtler15,Reference Maltusch, Krogmann and Spitzer16 While there is some research on the psychological consequences of soft repression, little is known about its long-term physiological imprint. Understanding this gap is crucial, as stress-related physiological processes are known pathways through which repression impairs downstream health and well-being. Reference Rohleder17

Research on other chronic stressors, such as bullying or discrimination shows that prolonged psychosocial stress may cause long-term dysregulation of stress and immune systems, increasing vulnerability to stress-related diseases. Reference Olweus18,Reference Berger and Sarnyai19–Reference Ravi, Miller and Michopoulos21 Specifically, chronic stress has been linked to elevated levels of pro-inflammatory markers, including interleukin-6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), as well as shortened leukocyte telomere length. Reference Segerstrom and Miller22,Reference Slavich, Harkness and Hayden23–Reference Egle, Heim, Strauß and von Känel29 Shortened telomere length, in turn, has been associated with greater susceptibility to age-related diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular and Alzheimer’s disease. Reference Rizvi, Raza and Mahdi30 These biomarkers therefore represent meaningful end-points for assessing the physiological consequences of repression experiences.

Given the limited knowledge of its effects, those affected by soft repression often struggle to be taken seriously or receive appropriate (health) care. Reference Frommer, Gallistl, Regner and Lison31 The present study aims to fill this gap by examining the long-term psychobiological consequences of soft repression, focusing on mental health, pro-inflammatory activity and telomere length. We hypothesised that individuals who experienced soft repression in the GDR would show elevated levels of depression, anxiety and trauma-related symptoms, compared with a non-repressed control group. Consistent with evidence from other severe stressors, we further expected repression to be associated with elevated levels of interleukin-6 and hs-CRP as well as shorter telomere length, indicating accelerated biological ageing.

Since repression in the GDR occurred over 30 years ago, individual outcomes were bound to vary. We considered resilience, social support and socioeconomic status (SES) particularly relevant for understanding the long-term consequences of soft repression. Repressive strategies directly undermine these domains: social bonds are targeted through surveillance and denunciation, educational and occupational opportunities are hindered with potential effects on SES and repeated experiences of fear and unpredictability likely erode resilience. Reference Peña, Meier and Nah7,Reference Jämte and Ellefsen10,Reference Marheinecke, Strauss and Engert.11 Beyond their specific relevance to repression, higher SES, stronger social support and greater resilience are well-established protective factors for adverse health outcomes in the stress literature. Reference Egle, Heim, Strauß and von Känel29 On this basis, we conceptualised resilience, social support and SES as potential pathways through which repression may exert long-term effects on health. For feasibility reasons, we treated these factors as moderators, examining whether they buffered the associations between repression and psychobiological outcomes. All hypotheses were preregistered and tested in a confirmatory manner.

Method

Study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Germany with participant recruitment and data collection taking place between June 2022 and June 2024. The hypotheses and study methods were preregistered at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/GHWE3. To streamline the manuscript, not all preregistered variables were included. Instead, we focused on the variables that were part of the main hypotheses. A separate publication presenting the omitted results is under preparation. We followed the STROBE reporting guidelines for cross-sectional observational studies. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the ethics committee of Jena University Hospital (No. 2022-2605_1-BO).

Participants

Two groups of former GDR citizens (total N = 100, aged 50–78 years), primarily from the states of Thuringia and Saxony in Germany, were recruited using flyers, local newspaper ads and support from local organisations (e.g. church communities). Recruitment strategies varied for the repression and control groups: the first specifically sought individuals who had experienced soft repression, providing examples in the recruitment materials. The latter targeted a broader audience of individuals aged 50 and older who grew up in the GDR. Final group allocation and inclusion was determined through telephone interviews. The repression group comprised 49 individuals who had experienced at least two state-organised soft repression techniques in the GDR, including planned surveillance, summoning to interrogations, denunciation or school/workplace harassment. The control group consisted of 51 individuals who lived in the GDR but reported no personal repression experiences. Both groups were matched for age, gender and GDR origin. Participation was deemed too challenging for individuals with acute psychopathology, leading to their exclusion from the study. Exclusion because of medication affecting cortisol levels was necessary due to an additional study component not reported here (measurement of acute and diurnal cortisol release; see below). In detail, exclusion criteria were (a) political imprisonment at any time, (b) current use of medications affecting cortisol release (e.g. steroids, antidepressants), (c) acute psychopathology, (d) active symptoms of affective disorders or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) within the past two months, (e) active symptoms of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders within the past two years and (f) excessive alcohol or recreational drug use.

We acknowledge that these criteria may have introduced a selection bias, excluding those most affected by their repression experiences. Furthermore, due to its heterogenic nature, the degree of experienced repression varied significantly within the repression group, while even the control group had experienced general systemic repression in the former GDR. In ambiguous cases, participants’ self-classification was respected at first, and their experiences further explored in an in-person interview. All such cases were subsequently confirmed as meeting the repression criteria. Despite these challenges to optimising the contrast between the experimental and control groups, we expected psychological and physiological differences to remain observable. The rationale for the recruitment process and detailed sample characteristics are provided in Marheinecke et al. Reference Marheinecke, Winter, Strauss and Engert32

The sample size for current analyses was predetermined for group differences in cortisol reactivity (separate preregistration: https://osf.io/s2c6p) through an a priori power analysis. The analysis indicated a required sample of N = 72 (one-sided t-test, α = 0.05, power 0.60, equal group sizes). To account for potential drop-outs and data loss, the target sample size was set at N = 100 (50 per group).

Procedure

Participants were initially screened in a telephone interview to determine group allocation and assess inclusion/exclusion criteria. All participants then completed a questionnaire battery, based on preference either in paper-and-pen format or online. The questionnaires included demographic information (e.g. age, gender, income, education and relationship status) and standardised measures assessing psychological distress (depression, anxiety or trauma symptoms). Subsequently, participants attended a 10 h laboratory visit (one participant instead requested a home visit) to provide two 7 ml blood samples. Blood samples were analysed to measure interleukin-6, hs-CRP and telomere length. Participants were instructed not to eat, drink coffee, exercise or smoke for at least two hours before the blood draw to avoid influences on leukocyte distribution. Furthermore, appointments were rescheduled if participants reported symptoms and signs of inflammatory or infectious diseases.

Other components of the study, not included in this manuscript, involved a qualitative interview during a separate visit scheduled prior to the laboratory appointment, an adapted version of the Trier Social Stress Test conducted on the day of the blood draw and diurnal cortisol sampling in daily life. These results are presented in separate publications currently under preparation. All participants provided written informed consent and were debriefed about the study’s aims upon completion.

Outcomes

Psychological questionnaires

To assess symptoms of depression, anxiety and trauma, we administered the German versions of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), the trait subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the symptoms scale of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ). As potential moderators, we measured resilience and perceived social support using the German versions of the Resilience Scale and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). Please see the Supplementary Material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10493 for the internal consistencies of and references for these measures (S.1).

Biological markers

For interleukin-6 and hs-CRP analysis, blood samples were centrifuged on-site to obtain plasma; for telomere length analysis, whole blood was used. Blood was pipetted into four screw-cap tubes and stored at −80 °C until termination of data collection. Subsequently, the plasma samples were sent to the laboratory of the Institute of Health Psychology in Erlangen, Germany, for the analysis of interleukin-6 and hs-CRP. The whole blood samples were shipped to the University of California San Francisco Blackburn/Lin lab for the measurement of telomere length (for information on the lab assay method, please see the information in Supplementary Material S.2).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted with the program R (version 4.4.1). T-tests or chi square tests were used to check for demographic differences (including age, gender and body mass index (BMI)) in the repression and control groups. No outliers were detected in the biological data, therefore no winsorisation was used. Due to non-normal distributions, interleukin-6, hs-CRP and telomere length were logarithmised using natural log. Within the questionnaire data, the data were condensed into summary or mean scores, as suggested by the respective authors. For sum score calculations, up to two randomly missing items per scale per participant were imputed using multiple imputation with the predictive mean matching method implemented in the mice package with 50 iterations. For mean score calculations, missing items were not imputed, but mean scores were calculated using the available items. For all scales, if a participant had more than two missing items, the respective score for that participant was not calculated (see Supplementary Material S.3). Missing biological data were not imputed. Final analyses included only participants with complete (imputed) data on the respective outcome and predictor variables. SES was calculated as an equally weighted sum score of income and education. Correlation tables of all variables were calculated for the full sample and for each group separately (see Supplementary Material S.14 and S.15). For all regression analyses, we report ß- and (adjusted) p-values; for significant effects, we report the effect size partial η 2.

Psychological distress

A MANCOVA was conducted including all psychological measures as dependent variables, group as predictor and gender and age as covariates. Subsequently, to further differentiate the effects, separate ANOVAs were ran for each dependent variable using the same predictors. To account for multiple testing, significant p-values were adjusted using false discovery rate (FDR). As a sensitivity analysis and to enhance robustness, we applied bootstrapping to the MANCOVA and ANOVA results (see Supplementary Table S.4).

Biological markers

We conducted separate linear regression models for each biological outcome variable (interleukin-6, hs-CRP and telomere length) to examine group differences (repression versus control), controlling for age, gender and BMI, given their significant influence. Reference Blackburn, Epel and Lin33,Reference Thorand, Baumert, Döring, Herder, Kolb and Rathmann34 To account for multiple testing within the immune marker cluster (interleukin-6 and hs-CRP), significant p-values were adjusted using FDR.

In a second step, we examined whether interactions of group with resilience, social support and SES predicted biological outcomes. To this end, the three interaction terms (group × resilience, group × social support and group × SES) were simultaneously entered into each of the three models (interleukin-6, hs-CRP and telomere length), resulting in a total of six models. Collinearity was assessed, and to prevent it, all interaction variables were centred. Although our preregistration proposed structural equation modelling to test a mediation, this approach was not feasible because of missing data and a resulting insufficient sample size. Therefore, we tested moderation models instead, examining whether psychosocial factors influenced the strength or presence of associations between repression and biological outcomes. ANOVAs were conducted to compare all models with and without covariates, assessing whether the inclusion of covariates significantly improved explanatory power. In all cases, the model including covariates showed a significant improvement, so covariates were retained in the final models. Model assumptions were visually checked (see Supplementary Material S.5) Additionally, we had hypothesised experience of transformation (time of and after German reunification) as another influential variable. However, the exploratory measure used to assess this variable resulted in predominantly missing data, making valid analyses impossible; therefore, it was excluded from all analyses.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Results

In total, 139 telephone screenings were conducted to assess eligibility – 77 with potential participants of the repression group and 62 with control individuals. Ultimately, 100 participants (49 in the repression group) were eligible and willing to participate, leading to their inclusion in the study. However, not all participants completed the psychological questionnaires, and some faced challenges with or declined the blood draw, resulting in varying sample sizes across different study components. For the blood data, there was an attrition rate of 18.37% in the repression group and of 17.65% in the control group (for details, see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S.6).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of inclusion process divided by repression and control groups.

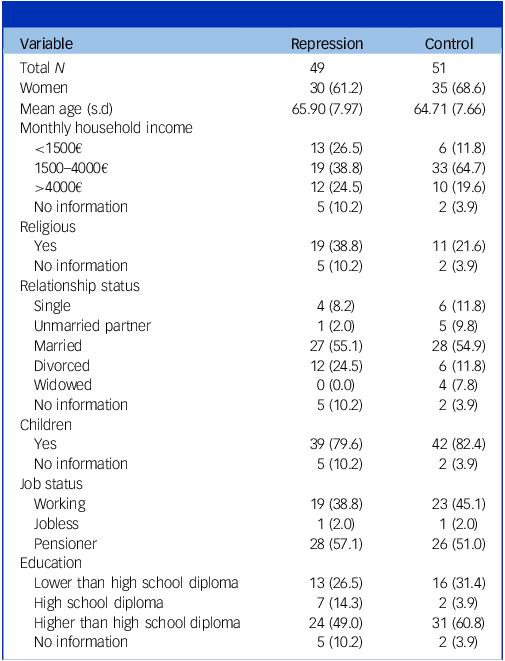

Repression and control groups did not differ in age (t(97.37) = −0.76, p = 0.448), gender (χ 2(1) = 0.32, p = 0.571) or BMI (t(88.42) = −0.14, p = 0.889). For full descriptive information, see Table 1. Visual inspection of correlation networks suggested differences in the relationships between psychological and biological variables across groups (see Supplementary Material S.14 and S.15).

Table 1 Demographic information

Unless otherwise stated, reported are respective numbers with percentages in brackets. For relationship status, multiple answers were possible. For demographic information on the subsample with complete blood data, see Supplementary Table S.7.

A MANCOVA (Estimate Wilks Λ) was conducted across the psychological distress variables, including age and gender as covariates, to test for group differences in depression, anxiety and trauma symptoms. As predicted, a significant effect of group on the combined distress variables (Λ = 0.82, F(3,85) = 6.40, p = <0.001) was revealed, with the repression group scoring higher on all three distress variables (see Supplementary Table S.8 and Fig. 2 for a detailed overview of the conducted ANOVAs). Neither age (Λ = 0.99, F(3,85) = 0.40, p = 0.751) nor gender (Λ = 0.99, F(3,85) = 0.10, p = 0.958) showed significant effects.

Fig. 2 Group differences in distress variables. Depicted are boxplots (including raw data points) of group differences between repression group (orange (grey in print edition)) and control group (blue) on psychological distress variables: anxiety (measured with the trait scale of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory), depression (measured with the Becks Depression Inventory) and trauma symptoms (measured with the trauma symptoms scale of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire). The p-values are reported as: ** ≤0.01, ***≤0.001.

The conducted regression analyses revealed that, for interleukin-6, group status was a significant predictor (β = 0.33, p adjust = 0.009, η2 = 0.13; see Fig. 3), indicating higher interleukin-6 levels in the repression group. As expected from prior research, BMI was also a significant predictor of interleukin-6 (β = 0.07, p adjust< 0.001, η2 = 0.30), with higher BMI associated with elevated interleukin-6 levels. Neither age (β = 0.00, p = 0.773) nor gender (β = 0.07, p = 0.597) had a significant effect.

Fig. 3 Group differences in interleukin-6 (IL-6), hs-CRP (high sensitive C-reactive protein) and telomere length (TL). Depicted are boxplots (including raw data points) of group differences between repression group (orange (grey in print edition)) and control group (blue) on physiological health variables. ** p ≤0.01.

Regarding hs-CRP, group status (β = −0.30, p = 0.274), gender (β = −0.28, p = 0.358) and age (β = 0.01, p = 0.721) showed no effect. Only BMI was a significant predictor of hs-CRP (β = 0.13, p adjust<0.001, η2 = 0.21), with higher BMI associated with elevated hs-CRP levels.

For telomere length, group status (β = 0.01, p = 0.829) and BMI (β = 0.01, p = 0.099) showed no effect. Older age (β = −0.01, p = 0.014, η2 = 0.10) and male gender (β = −0.09, p = 0.011, η2 = 0.08) were significant predictors of shorter telomere length. All regression tables are depicted in Supplementary Table S.9.

The repression group reported lower resilience compared with controls (Mrep = 5.45, Mcon = 5.83; t(76.70) = 2.67, p = 0.009), while no group differences were found for social support Mrep = 22.7, Mcon = 23.9; (t(87.59) = 1.3015, p = 0.196) or SES (t(89.28) = 0.71, p = 0.478). To test whether interactions of group with social support, resilience or SES were linked to interleukin-6, hs-CRP and telomere length values, we conducted three additional regression analyses. Interleukin-6 and hs-CRP were uninfluenced by group by social support (interleukin-6: ß = 0.02, p = 0.626; hs-CRP: ß = −0.10, p = 0.268), group by SES (interleukin-6: ß = 0.28, p = 0.383; hs-CRP: ß = −0.32, p = 0.666) and group by resilience interactions (interleukin-6: ß = −0.24, p = 0.367; hs-CRP: ß = 0.24, p = 0.695, see Supplementary Fig. S.10). However, there was a significant interaction effect for social support and group on telomere length. In the repression group, higher social support values predicted longer telomeres (ß = 0.02, p = 0.032, η2 = 0.07; see Supplementary Fig. S.11 and Table S.13). Group by SES (ß = −0.01, p = 0.870) or resilience interactions (ß = −0.05, p = 0.506) showed no effects (see Supplementary Table S.12).

Discussion

The current study examined the lasting impact of soft political repression in the former GDR, focusing on its psychological and physiological health consequences. In line with prior research, Reference Spitzer, Ulrich, Plock, Mothes, Drescher and Gurtler15,Reference Maltusch, Krogmann and Spitzer16 results showed that experiencing repression was associated with elevated psychological distress levels (anxiety, depression or trauma symptoms). Further, the repression group exhibited elevated levels of interleukin-6, indicating increased systemic inflammation in comparison with the control group. No group level differences were found for hs-CRP and telomere length. The repression group (versus control group) reported lower resilience, while no group differences were found for social support. However, an interaction effect between social support and group membership on telomere length suggested that the presence of social support can buffer the negative effects of repression on cellular ageing. Resilience and SES, and their interactions with the group had no influence on any of the biological outcome variables.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the psychobiological health consequences of soft repression. Results suggest that even more than 30 years after the repression experience, affected individuals show heightened systemic inflammation as measured by levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6. Chronic inflammation is proposed to be a key pathway from – particularly psychosocial – chronic stress exposure to a variety of stress-related conditions, including cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular, pulmonary and neurological diseases, as well as depression, Reference Egle, Heim, Strauß and von Känel29,Reference Slavich, Auerbach, Butcher and Hooley35 underscoring its relevance to the health impact of soft repression. The lack of a similar effect on hs-CRP aligns with findings from depression research, where interleukin-6 has been more consistently and strongly associated with the clinical phenotype and relevant stress-related factors. Reference Ye, Kappelmann, Moser, Davey Smith, Burgess and Jones36 The interaction between repression experience and social support on telomere length conveys a hopeful message: repression experiences do not seem to determine the rate of cellular ageing, but rather, harmful effects may be buffered by social support networks. This finding aligns with trauma research, in which social support is recognised as a key protective factor mitigating the negative impact of traumatic experiences, including effects on mental health outcomes like PTSD. Reference Wang, Chung, Wang, Yu and Kenardy37 While a recent meta-analysis has found no general association between social support and telomere length Reference Montoya and Uchino38 – a pattern mirrored in our control group – some studies have reported such a link in populations facing chronic stressors, such as discrimination, or in individuals with heightened vulnerability, such as older adults. Reference Carroll, Diez Roux, Fitzpatrick and Seeman39,Reference Hailu, Needham, Lewis, Lin, Seeman and Roux40 Our findings carefully extend this evidence, suggesting that social support may be linked to cellular ageing processes specifically in populations experiencing chronic accumulation of adverse experiences or increased vulnerability. This aligns with our observation of seemingly different correlation networks between psychological and biological measures in the control versus repression groups, indicating potentially distinct biopsychosocial profiles that warrant further investigation.

Although the exact methods of repression used in the GDR are historically unique to their specific context, soft repression techniques continue to play an active role in authoritarian (but also democratic or hybrid Reference Davenport2 ) regimes today, as studies in Hong Kong, Zimbabwe or Colombia demonstrate. Reference Peña, Meier and Nah7,Reference Yuen and Cheng9,Reference Young41 These methods pursue the same objectives as soft repression in the GDR, and are carried out in comparable ways. Reference Nussmann42 We assume that similar underlying psychological mechanisms are at play, potentially leading to comparable psychobiological health consequences. In line with this, the few existing studies on psychological consequences in repression victims across different populations show similar outcomes as found here, including fear and depressive states, as well as behavioural effects like self-policing. Reference Peña, Meier and Nah7,Reference Jämte and Ellefsen10

There are likely other factors that influence how repression experience is perceived and processed. Purposefully engaging in oppositional work, for instance, can provide a sense of coherence, offering protection against negative consequences. In contrast, being targeted without understanding why may evoke feelings of shame, uncertainty and confusion, making coping more difficult (sense of coherence Reference Antonovsky43 ). To this end, a finer distinction of the individual repression experience and its psychophysiological consequences within a larger sample size would be interesting for future research. It might also be important to consider the context in which repression occurs – what defines a stressor in a particular regime, under specific circumstances, and within a given cultural background (e.g. the meaning of joblessness in a communist versus democratic regime, see Reference Marheinecke, Strauss and Engert.11 ). This would be especially important when comparing repression experiences and their consequences across several countries and times.

There are several limitations to our study. First, sample size is relatively small and was predefined by a study part not subject to the current manuscript. Given that this is the first study to explore the topic, and effect sizes are substantial, findings remain meaningful. Nevertheless, some analyses, particularly the interaction models, may be underpowered and should be interpreted with caution – especially since only one interaction reached significance. These results highlight the need for replication in larger samples to confirm the robustness of the observed patterns. Second, the study employs a cross-sectional design, limiting the ability to draw causal inferences and to examine potential moderating or mediating mechanisms. Moreover, the reporting of repression experiences was retrospective, possibly introducing memory bias or reinterpretation of past events in light of participants’ current circumstances. Third, group allocation was challenging. Since all participants lived in the GDR, everyone experienced some form of systemic repression, even if it was not specifically targeted to the individual. As a result, the distinction between repression and control groups is not clear-cut. Additionally, the repression experiences within the repression group were highly heterogeneous. However, artificially standardising groups would not do justice to the complex nature of repression. Anticipating the heterogeneity, we collected extensive qualitative interview data that will help to better understand the varied experiences made. Importantly, we do observe group differences in our quantitative surveys and stress-related biomarkers, suggesting that despite the heterogeneity and systemic repression in both groups, there are common factors influencing health within the repression group. Moreover, due to strict exclusion criteria (e.g. current psychopathology, corticosteroids), our sample may reflect particularly resilient individuals. Thus, the actual impact of soft repression may be more pronounced. Future research should examine repression as a dimensional construct, exploring how varying levels of severity lead to different consequences. Another relevant consideration is self-selection: who chose to participate in our study – those most affected, least affected or simply those most interested? All limitations related to the sample are discussed in detail in Marheinecke et al. Reference Marheinecke, Winter, Strauss and Engert32

Globally, many democratic regimes are currently showing a shift towards autocracy, with repression rising and freedom declining. Reference Gorokhovskaia and Grothe1 Also, with the advancement of technological innovation, possibilities for surveillance and repression have dramatically improved. Reference Feldstein44 Understanding the health impact of soft political repression is, therefore, not only crucial in a historical context, but also for supporting individuals facing this form of repression today and in the future. We show here that soft political repression may have profound and lasting effects on individual health. Future research should focus on understanding how repression impacts diverse populations, exploring both the psychological and physiological consequences in different cultural and political contexts. Identifying key protective factors, such as social support and coping strategies, is essential for mitigating negative health outcomes. Moreover, there is a pressing need for psychological research that captures the complexity of individual health, as greater nuance can support more effective clinical care for those affected by repression. It is equally important to consider the broader systemic context in which affected individuals live, ensuring that interventions extend beyond the personal level to also target the larger political and social structures that sustain repression experiences.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10493

Data availability

The study protocol, informed consent forms, all R code and other relevant study material are provided on the OSF platform (https://osf.io/k2ezx/). De-identified participant data will be provided upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ann-Christin Winter, Laura Beuthien, Tuba Korkmaz-Walther and Hazel Imrie for their contributions to the laboratory testings. Further, we gratefully acknowledge Nico Schneider’s ever-present help in the organisation of the study. ChatGPT-4 was used to assist in streamlining individual sentences within the manuscript and optimising R code. All AI-generated content was reviewed and revised by the authors.

Author contributions

CRediT author statement: conceptualisation (R.M., V.E.); methodology (R.M., V.E.); formal analysis (R.M., J.B.); investigation (R.M.); resources (V.E., B.S., J.L., N.O.); writing – original draft (R.M.); writing – review and editing (all authors); visualisation (R.M.); supervision (V.E., B.S., E.E.); project administration (R.M.); funding acquisition (B.S., C.S.). All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. R.M. and J.B. have accessed and verified the data.

Funding

R.M., C.S. and B.S. are part of the multicentre-project Health Consequences of SED Injustice, which receives funding from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (Bundeshaushalt 2021, Kapitel 0910, Titel 68603 and Bundeshaushalt 2024/25, Kapitel 0415, Titel 544 01 Förderzeichen 411-AS 06/2024). R.M. was additionally funded by a Fulbright Doctoral Scholarship awarded by the Fulbright Germany Commission.

Declaration of interest

V.E. serves as a member of the advisory board for Heel regarding the medication Neurexan. This relationship has no influence on the content or conclusions of the current publication. All other authors have no known interests to declare.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.