1 Introduction

HERITAGE IS EVERYWHERE.

When David Lowenthal began his seminal work The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History some twenty years ago, he wrote this statement to critique the global heritage movement. Here, I borrow it, not only to mean that the heritage movement is more pervasive today and demands for more critical inquiries but also to summon greater diversity in heritage thinking, research, and practice. Indeed, heritage is everywhere, but people in different parts of the world may talk about, understand, and deal with it differently. This Element starts from the premise that heritage is not something out there but a meaning-making process and sociocultural practice; a key component is how discourse works to represent and construct what heritage is (not) and coerces how people perceive and act upon heritage (Smith Reference Smith2006; Waterton Reference Waterton2010a; Wu & Hou Reference Wu, Hou, Waterton and Watson2015). I aim to accentuate that heritage (as) discourse is culturally saturated and should be diverse or diversified in relation to geography and time. For critical heritage scholars, searching for and rearticulating alternative cultural discourses of heritage that have been marginalized, devalued, or forgotten in the global heritage movement is equally, if not more, important than critiquing the dominant discourses to advance this new interdisciplinary field of inquiry.

In recent years, we have seen increasingly more research endeavors to explore alternative discourses of heritage, among which most are done from ethnographic and community-archaeological perspectives (e.g., Astudillo & Salazar Reference Astudillo and Salazar2024; Byrne Reference Byrne2014; De Jong & Rowlands Reference De Jong and Rowlands2007; Evans & Rowlands Reference Evans and Rowlands2021; Onciul Reference Onciul2015; Rico Reference Rico2016; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2017; Yu & Mei Reference Yu and Mei2024). This Element intends to showcase a different approach to critical heritage studies, one that turns our attention to forgotten or transformed discourses of heritage in their cultural-historical contexts. In other words, I advocate for an approach to researching and rearticulating cultural discourses of heritage in past times. As Harvey (Reference Harvey2001) has pointed out, heritage is a human condition, rather than a modern movement starting from the nineteenth century or any other time. By analyzing how people write and make meaning of the past in the past, we can not only challenge the knowledge/power of the Western “Authorized Heritage Discourse” (AHD, Smith Reference Smith2006) but also demonstrate how heritage might be conceptualized, categorized, communicated, and construed in different ways and with alternative cultural logics over time and across geographical areas.

This historical perspective on heritage (as) discourse is largely overlooked in current critical heritage scholarship. It is not that critical heritage researchers have little interest in history or historical materials. On the contrary, most of them do. Yet, rarely do they conduct discourse analysis of historical documents to rearticulate forgotten or substituted cultural ideas of heritage, or their underlying ways of thinking and valuing the past. As I will demonstrate, unpacking heritage discourse in history is genuinely beneficial to diversify heritage thinking, research, and practice. In China, this historical approach is particularly useful, if not indispensable. For one thing, China has a long history of dealing with sites and objects that we tend to call “heritage” today, yet its contemporary heritage policies and practices have been largely shaped by modern, Western discourses, the AHD in particular. Though the cry for rethinking and reformulating heritage becomes increasingly louder, Western-originated concepts, principles, and models of heritage practice are still mainstream. For another, China is extremely rich in historical documents, which provide data for us to find alternative cultural ways of conceptualizing, categorizing, and constructing what we today term heritage. My focus in this Element is on a Chinese cultural discourse – guji (古迹, ancient traces or vestiges) in historical times. Guji is putatively the first term that would come to mind if a Chinese person were asked for a counterpart to cultural heritage in their language (Hou Reference Hou2019: 456; see also Li Reference Li2013). As will be shown, although this Chinese word is still widely in use, the meaning or idea it conveys has been subtly transformed by the Western, globalized discourse of heritage. My central task is to rearticulate how the Chinese, in times before their enthusiastic embrace of modern, Western historical consciousness and the World Heritage Movement, represented and made meaning of their guji for remembrance and responsive actions. Guji might include historic buildings, sites, and places that readily fall into the category of cultural heritage, as well as others that are hard to classify as heritage in its contemporary definition such as a tree or a stone (see section 3). I will first examine how guji is generally understood in China in the present era of “world heritage craze” (Yan Reference Yan2018) and in historical times. This can be regarded as a macroanalysis of the Chinese guji discourse. Then, I come to the core of this treatise: a focused cultural-historical discourse analysis of guji in an ordinary Chinese heritage city, namely, Quzhou in the Zhejiang province.

This grounded historical inquiry into the guji discourse will help rearticulate Chinese cultural ways of meaning-making and remembering the past, which have been discarded, forgotten, or transformed while the country has embraced the modern historical consciousness and ethos of heritage conservation originating from Europe. It is thus both a critical project to challenge the AHD and other globalized heritage ways of thinking that construe commonsense knowledge of what heritage is and how it should be handled, and a constructive enterprise to promote dialogue and diversity regarding heritage from a Chinese cultural and historical perspective. In Harvey’s (Reference Harvey2024: 4) words, this Element presents a “more-than-critical” approach to heritage studies, as I will not only critique the dominant, authoritative discourses but also take “an invitational attitude towards alternative modes of being and doing.” I can also say this approach reflects a Chinese cultural understanding of critical scholarship: being critical does not necessarily mean confronting, challenging, or deconstructing; acts of historicizing, exploring alternatives, or remaking can be critical as well (Hou & Wu Reference Hou and Wu2015; Zhu Reference Zhu2024b; see also Hou & Wu Reference Hou and Wu2017 for an alternative approach to critical discourse studies based on a case study of heritage in Quzhou).

Furthermore, this Element also contributes to advancing heritage discourse studies – a research line that integrates heritage studies and discourse studies, the history of heritage (particularly, the conceptual history, or history of ideas of heritage in China), and other pertinent interdisciplinary areas of scholarship, such as memory studies, historical geography, and Chinese studies. As Wu and Hou (Reference Wu, Hou, Waterton and Watson2015) have pointed out, heritage discourse studies focus mostly on critiquing the authoritative, dominant, and globalized, by adopting various discourse analytical methods such as critical discourse analysis (Barry & Teron Reference Barry and Teron2023; Smith Reference Smith2006: chapter 3; Waterton Reference Waterton2010a; Waterton et al. Reference Waterton, Smith and Campbell2006), Foucauldian discourse analysis (Melis & Chambers Reference Melis and Chambers2021; Wight Reference Wight2016), multimodal discourse analysis (Feng et al. Reference Feng, Li and Wu2017, Reference Feng, Dai, Jiang and Wei2018; Skrede & Andersen Reference Skrede and Andersen2023; Waterton Reference Waterton2009, Reference Waterton, Waterton and Watson2010b), and sociolinguistic discourse analysis (Coupland & Coupland Reference Coupland and Coupland2014; Coupland et al. Reference Coupland, Garrett, Bishop, Jaworski and Prichard2005), as well as a combination of discourse analysis with other methodological or epistemological perspectives (Angouri et al. Reference Angouri, Paraskevaidi and Wodak2017; Skrede Reference Skrede2020; Skrede & Hølleland Reference Skrede and Hølleland2018). However, discourse analytical perspectives and methods are much less frequently applied to explore alternative ways of talking about and thinking of what we today tend to call “heritage.” To present a discourse analysis of an alternative concept of heritage from historical China, this Element intends to bridge historical and discourse studies of heritage, and to encourage cross-fertilization of these two subfields of heritage research. As I will show, rearticulating disregarded, forgotten cultural discourses of what is now termed “heritage,” such as guji, in their pasts is a compelling approach to rethinking and reconstructing heritage.

Although historical research on heritage has been growing in recent years (e.g., Bloembergen & Eickhoff Reference Bloembergen and Eickhoff2020; D’Agostino Reference D’Agostino2021; Falser Reference Falser2020; Jokilehto Reference Jokilehto2017; Swenson Reference Swenson2013; Zhu Reference Zhu2024a), it remains a relatively underdeveloped subfield of heritage scholarship. Systematic studies in the conceptual history or history of ideas regarding heritage are even scarcer (but see Eriksen Reference Eriksen2014; Wang Reference Wang, Stolte and Kikuchi2017). It should be noted that many scholars have concerns over perceptions or understandings of heritage in historical times, yet their studies are concentrated on historical practices or ways of practicing what we now tend to call “heritage.” (Gilman Reference Gillman2010: chapter 4; Wang Reference Wang2020; Wang & Rowlands Reference Wang, Rowlands, Geismar and Anderson2017; Zhu Reference Zhu2024a) These studies are better described as cultural or social histories of heritage. The current Element is intended to contribute to the conceptual history of heritage by explicating the Chinese notion of guji. Eriksen’s (Reference Eriksen2014) historical inquiry into the evolution of such concepts as antiquity, monument, and cultural heritage in Nordic culture since the 18th century is a rare and laudable book-length contribution to this branch of heritage history. My work in this Element is more focused: It investigates one single Chinese cultural concept of heritage in an eastern Chinese city–Quzhou (衢州)–during the period from late imperial to mid Republican China, or, more precisely, from the 1500s to the 1920s. Wang Shu-li’s (Reference Wang, Stolte and Kikuchi2017) historical exposition of the Chinese term wenwu (文物) is, perhaps, the most similar to my research. However, her study is rather general, without detailed analysis of specific historical texts. Adopting a discourse analytical approach, I attempt to unravel the disregarded cultural episteme and meaning-making apparatus of guji, hoping to facilitate heritage rethinking and dialogue in a more nuanced manner.

A Cultural-Historical Discourse Approach to Heritage

Discourse, as Foucault (Reference Foucault1972: 49) states, consists of “practices which systematically form the objects of which they speak.” Heritage can be viewed as such an object formed in and through discursive practices, primarily our words that speak of it. In this Element, I further highlight, following cultural discourse scholars, the embeddedness of discourse in culture. Shi-xu (Reference Shi-xu2005, Reference Shi-xu2014), for example, theorizes discourse as cultural ways of speaking. As he writes:

different cultures have different histories, conditions, problems, issues, aspirations, and so on. Consequently, the different cultural discourses which constitute them will have not only different objects of construction or topics, but also different categorizations, understandings, perspectives, evaluations, and so on. They make up different cultural worlds, so to speak.

Donal Carbaugh, another leading advocate of cultural discourse research, defines cultural discourse as “a historically transmitted expressive system of communication practices, of acts, events, and styles, which are composed of specific symbols, symbolic forms, norms, and their meanings” (Reference Carbaugh2007: 169). Both of these scholars have pinpointed the link between cultural discourse and history. When studying cultural discourses of heritage, this link should be more accentuated. The reason for this is simple: Heritage is “historically transmitted” as well. What is more, as will be shown, careful investigations into history can lead us to see alternative ways of heritage conceptualization, categorization, communication, construction, and action, which should be transmitted yet are largely stigmatized, marginalized, or forgotten in the present climate of global heritage craze. Therefore, we need to approach history from a discourse perspective, particularly a cultural discourse perspective. That means studying history is not to trace historical facts, events, causes, or backgrounds but rather to look into the texts produced in the past and scrutinize how those texts construct what we tend to classify as “heritage” today.

That said, I am bringing to light a cultural-historical discourse approach to heritage. It grows out of my efforts in collaboration with colleagues in exploring alternative Chinese understandings of heritage (Hou Reference Hou2019; Hou & Wu Reference Hou and Wu2012, Reference Hou and Wu2015; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Liu and Gao2019). It is different from the established cultural approaches to discourse analysis, such as Shi-xu’s “cultural discourse studies” (Reference Shi-xu2005, Reference Shi-xu, Tracy, Ilie and Sandel2015) and Carbaugh’s “cultural discourse analysis” (Reference Carbaugh1996, Reference Carbaugh2007) in that it focuses on historical rather than contemporary texts as its main data. The defining attribute of this approach is that it is simultaneously cultural and historical. That is, the researcher takes on a discursive perspective on history and a historical perspective on discourse. Following Foucault (Reference Foucault and Rabinow1984) and White (Reference White1973, Reference White1987), I see history as a form of narrative or discursive construction. Historical inquiries are not much about finding a systemic process of development or the causes for a present discourse (cf. Blommaert Reference Blommaert2005: 37; Flowerdew Reference Flowerdew2012; Reisigl & Wodak Reference Reisigl, Wodak, Wodak and Meyer2015). Rather, they involve collecting and interpreting various texts produced in historical times and unpacking the meaning production, reality construction, and ways of remembering, valuing, and using what we today term “heritage” in the past. In other words, by probing into history, we come to understand the forgotten historical words and worlds, values and ways of valuing, and thoughts and modes of thinking about “heritage”; and we can attend to the divergences, ruptures, and transformations in how heritage is conceptualized, categorized, and coped with in different times. Such an approach will allow us to historicize present discourses of heritage in China and reflect upon their underlying ways of knowing and politics of the past.

Furthermore, this cultural-historical discourse approach to heritage will not rigidly follow any established discourse analytical framework to explain and interpret data, given that they are designed primarily for or based on the investigation of texts coded in modern languages, especially European languages (Shi-xu Reference Shi-xu2012). Nor will I attempt to set up a new discourse analytical framework claimed to be more applicable for examining texts in classical Chinese, which is impossible in the space this Element allows. Instead, some analytical strategies can be outlined here to serve as rough guidelines for cultural-historical discourse studies of heritage.

First, the beginning of this cultural-historical discourse approach is a set of commonly asked questions for undertaking discourse analysis:

(1) What is (not) said about “heritage” (in general terms or a specific instance) in the texts under investigation?

(2) How is the said articulated, and how is the unsaid concealed?

(3) What underlying meaning- and value-making may be sustained, and what ideology or cultural way of thinking may be significant in such forms of discursive representation of “heritage”?

(4) What social and cultural consequences and responses may such discursive representations of “heritage” bring forth?

Bearing these questions in mind, the researcher starts to read the textual data they have collected critically.

Second, the noticeable features in the textual data under inspection generally become the focal points for analysis. These features may be about content (topics, themes, categories, events) or form (linguistic-textual, intertextual, stylistic, rhetorical, generic, and so on) in representing “heritage.” Analytical vocabularies from heritage studies, discourse and communication studies, and other relevant disciplines may be useful for describing those content or formal features, such as materiality, authenticity, site, emotion, and quotation.

Third, it is also important to interpret the meaning- or value-making process, discursive-constructing work, and cultural ways of thinking, doing, and being regarding “heritage” underlying the content and form of the historical texts under study. This interpretive procedure should involve careful examination of the local, cultural, and historical contexts in which the texts are produced. Furthermore, comparative and contrastive analysis with reference to the dominant, globalized discourses may be illuminating.

I should note that, when doing cultural-historical discourse analysis of “heritage,” it is not always necessary to address every point mentioned in the commonly asked questions outlined previously, or to scrutinize every form or content feature identified in the textual data. Rather, the researcher selects the most salient features that serve their analytical purposes, as discourse analysts usually do. For example, the researcher may choose the thematic and some of the linguistic-textual features to analyze their data and then interpret how those features work to construct alternative heritage understandings and values.

This cultural-historical discourse approach is effective in rearticulating alternative understandings of heritage in cultural settings. For example, I have adopted this method to delineate the remembrance of trees as heritage in the city of Hangzhou during the Qing dynasty (1636–1911), revealing a fourfold meaning-making apparatus through which trees, physically existent or not, were rendered culturally significant for the remembrance of historical figures, place names, poetic writings, and exceptional landscapes. In this Element, my focus is Quzhou in the late imperial and mid Republican eras.

Quzhou as an Ordinary Chinese Heritage City: The Context and Texts

To study Chinese guji discourse, it would be useful to probe into a particular locality, apart from observations and analyses at macro levels. As Walsh states in his critical study of heritage representations in the United Kingdom, “What is necessary is a rearticulation of discourses based on the locality, a manageable context which permits the development of democratic discourse” (Reference Walsh1992: 3; my emphasis). I chose the city of Quzhou as the locality to serve my objective of rearticulating a marginalized, forgotten Chinese cultural discourse of heritage, hoping to facilitate the development and dialogue between different heritage discourses. Nonetheless, I do not think there is one democratic discourse that is good for all. As is known, either democracy or discourse implies choice-making, that is, to select and foreground one among possible alternatives.

Situated in western Zhejiang (see Figure 1), Quzhou is about 230 kilometers northwest from the provincial capital Hangzhou, and about 400 kilometers southwest from the biggest Chinese city Shanghai. Like most Chinese cities, Quzhou has a long history to trace. According to local historiographies, it was first established as a county in 192 AD, called Xin’an (新安), which was renamed Xin’an (信安) in 280. In 621, the prefecture of Quzhou was founded in the early Tang dynasty, with Xin’an County (信安县) being its prefectural seat (Shen et al. Reference Shen and Wu2009: 7; Lin et al. Reference Lin and Ye2009: 380). Some 250 years later, the city name Xin’an (信安) was changed to Xi’an (西安), which lasted until the end of imperial China. With the transition to the Republic of China in 1912, its name was altered to Qu County (衢县; Zheng Reference Zheng1984: 118, 121). The county of Xin’an, Xi’an or Qu shares roughly the same territory as the present Quzhou city. It is the regional scope this Element will focus on.

Figure 1 A map of Zhejiang province emphasizing Quzhou.

Quzhou is one among the 142 renowned cultural-historical cities sanctioned by the Chinese central government since 1994. It has several national heritage sites and dozens more provincial and prefectural ones. As a heritage city, Quzhou is not especially outstanding or unique in the vast territory of China. It is just an ordinary city of its kind and, for that matter, not much visited by cultural tourists or examined by heritage scholars apart from me and a few colleagues I have worked closely with (Hou & Wu Reference Hou and Wu2012; Hou et al. Reference Hou, Liu and Gao2019; Wu Reference Wu2012b; Wu & Hou Reference Hou and Wu2012; Zhang Reference Zhang2019). It is certainly less appealing than many other well-known Chinese heritage cities such as Beijing, Xi’an, Hangzhou, or Lijiang. However, the politics of heritage shaped by Western AHD and local AHDs as a fusion or interaction of the global, Chinese national, and local authoritative discourses, is no less observable in Quzhou than in other parts of China (e.g., Blumenfield & Silverman Reference Blumenfield and Silverman2013; Shepherd & Yu Reference Shepherd and Yu2013; Su & Teo Reference Su and Teo2009; Svensson & Maags Reference Svensson and Maags2018; Yan Reference Yan2018; Zhu & Maags Reference Zhu and Maags2020). Postulating this in contemporary Quzhou might be an interesting project to pursue, but it is not my main concern in this Element. What I want to do, as stated earlier, is to contribute to a cultural-historical discourse approach to heritage, and particularly to rearticulating the Chinese discourse of guji for cultural reflections on the globalized heritage movement and its politics. In historical China, guji was a ubiquitous discourse, and an ordinary heritage city like Quzhou can well serve as the locality for a cultural-historical project I wish to pursue.

From a cultural-historical discourse approach, historical texts that document what we call “heritage” are of key importance. However, historical texts are usually utilized as testimony in contemporary heritage projects. In that manner, the pastness of those texts is rendered subject to the present idea of what heritage is and what values heritage has. Following Fairclough (Reference Fairclough1992), I see a text as manifestation or materialization of a discourse. Thus, a historical text about guji is a materialization of this particular Chinese discourse in context.

Among the most useful sources of such historical texts for studying Chinese guji discourse are the premodern fangzhi or local gazetteers. Fangzhi is a Chinese genre for recording a locale, as fang means locale, and zhi means documentation or written records. Fangzhi has been categorized as either geographic or historical writing. Some scholars view them as both historical and geographic; they are historicized geography and geographically bounded history (Yang Reference Yang1999: 3). In other words, local gazetteers record historicized places and localized history. The compilation of such local gazetteers can be dated back to far ancient times in Chinese history. It is generally held that the genre came to its maturity in the Song dynasty (960–1279) and the peak of its compilation was seen in the Ming (1368–1644) and the Qing (1644–1911) eras. Most of the surviving premodern local gazetteers were compiled during this timeframe. They have been mainly used as references for governance, education, and culture- and memory-making (Cang Reference Cang1990: 1–2).

Seven premodern local gazetteers of Quzhou have been found; they will serve as the data for exploring the Chinese discourse of guji in this Element. I should note that my distinction between “modern” and “premodern” local gazetteers is based not so much on the historical phases circumscribed by historians, but rather on the linguistic features and historical consciousness an individual local gazetteer demonstrates. The premodern local gazetteers were coded in the classical Chinese language and, more importantly, the historical consciousness that underwrote them was rooted in the Confucian historiographical tradition. In other words, the modern sense of historicity from the West had not yet exercised its considerable influence on the way they were written. These seven premodern local gazetteers of Quzhou were compiled in the late imperial and the Republican China eras, including four prefectural gazetteers and three county gazetteers. The prefectural gazetteers, bearing the same title Quzhou Prefectural Gazetteer (衢州府志), encompass local-historical records of the greater Quzhou region, which includes the present Quzhou city and some neighboring cities. My analysis, however, will concentrate primarily on the records of guji in the city of Quzhou.

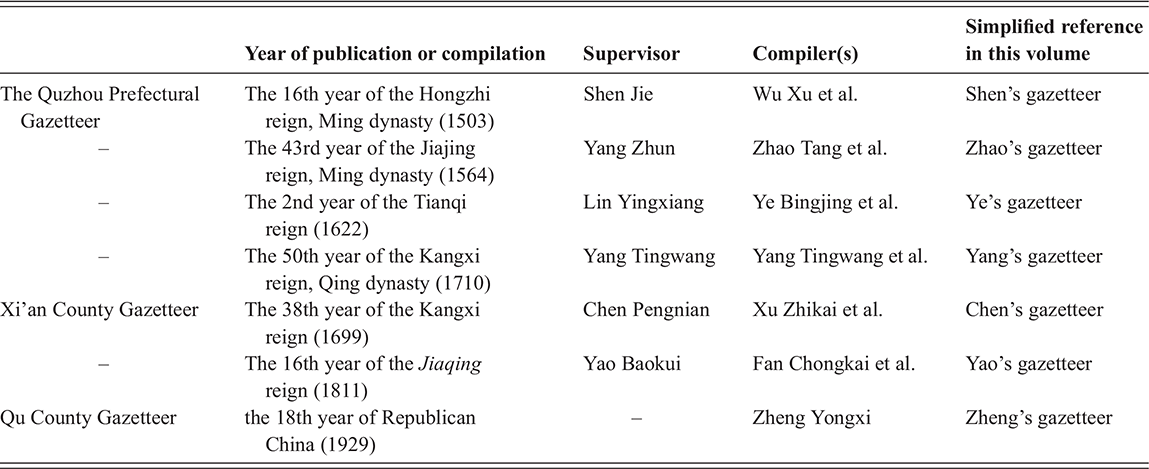

Three of these prefectural gazetteers were compiled in the Ming dynasty. They were completed in, respectively, the sixteenth year of the Hongzhi reign (1503) by Shen Jie (沈杰), Wu Xu (吾冔), and others, the forty-third year of the Jiajing reign (1564) by Yang Zhun (杨准), Zhao Tang (赵镗), and others, and the second year of the Tianqi reign (1622) by Lin Yinxiang (林应翔), Ye Bingjing (叶秉敬), and others. The other one was a Qing-dynasty gazetteer finished in the fiftieth year of the Kangxi reign (1710) by Yang Tingwang (杨廷望) and others.Footnote 1 The three county gazetteers are records of the Quzhou city proper, including the two Qing-dynasty Xi’an County Gazetteers (西安县志) compiled, respectively, in the thirty-eighth year of the Kangxi reign (1699) by Chen Pengnian (陈鹏年), Xu Zhikai (徐之凯), and others, and the sixteenth year of the Jiaqing reign (1811) by Yao Baokui (姚宝煃), Fan Chongkai (范崇楷), and others, and the Qu County Gazetteer (衢县志) finished in the eighteenth year of the Republican China period (1929) by Zheng Yongxi (郑永禧, 1866–1931). For an overview of these local gazetteers, see Table 1.

| Year of publication or compilation | Supervisor | Compiler(s) | Simplified reference in this volume | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Quzhou Prefectural Gazetteer | The 16th year of the Hongzhi reign, Ming dynasty (1503) | Shen Jie | Wu Xu et al. | Shen’s gazetteer |

| – | The 43rd year of the Jiajing reign, Ming dynasty (1564) | Yang Zhun | Zhao Tang et al. | Zhao’s gazetteer |

| – | The 2nd year of the Tianqi reign (1622) | Lin Yingxiang | Ye Bingjing et al. | Ye’s gazetteer |

| – | The 50th year of the Kangxi reign, Qing dynasty (1710) | Yang Tingwang | Yang Tingwang et al. | Yang’s gazetteer |

| Xi’an County Gazetteer | The 38th year of the Kangxi reign (1699) | Chen Pengnian | Xu Zhikai et al. | Chen’s gazetteer |

| – | The 16th year of the Jiaqing reign (1811) | Yao Baokui | Fan Chongkai et al. | Yao’s gazetteer |

| Qu County Gazetteer | the 18th year of Republican China (1929) | – | Zheng Yongxi | Zheng’s gazetteer |

The Qu County Gazetteer was not commissioned by any officials. I should note, though, that it is an excellent one, perhaps the best in quality among the seven local gazetteers (Tang Reference Tang2015). The compiler, Zheng Yongxi, took five years to finish it. He eventually lost his eyesight working on the project day and night. His friend Yu Shaosong (余绍宋, 1883–1949) helped him proofread the draft and publish it (Tang Reference Tang2015: 96). Zheng Yongxi was born into a family of literati and was well trained in traditional Chinese scholarship. Although the Qu County Gazetteer was compiled in the late 1920s, that is, at a time when the Chinese historiographical revolution under Western influences had spread quite widely (see Huang Reference Huang1997; Wang Reference Wang2001), it is regarded as a premodern local gazetteer because it is written in classical Chinese, and, as shall be seen in later sections, reflects traditional historical consciousness and ways of writing. Considering the excellence of this local gazetteer, I will not shy away from using its entries as examples in my cultural-historical discourse analysis.

Outline of Sections

This Element will present macro- and micro-analyses of the Chinese guji discourse in its cultural-historical contexts as an alternative to the current dominant, globalized idea of heritage. It consists of six sections. Apart from this first section, which provides an overview of the Element, and a concluding section to reflect on my findings under a philosophical lens and the insights it may shed on further research, the main body is divided into four sections.

Section 2 sets out to do a macroanalysis of the Chinese discourse of guji in the present and in the past. I will first explain how guji is defined in contemporary China, revealing its convergence with the AHD. Then I will elucidate the concept of guji in historical Chinese contexts through two steps: (1) an analysis of guji via a philological reading of the two Chinese characters that make the word, gu and ji, and (2) an analysis of the prefaces to the guji chapters or volumes in Chinese local historiographies compiled in historical times. In so doing, I will be able to give a glimpse of the Chinese guji discourse compared to the mainstream notion of heritage today. It can also function as an exploration of the cultural root and context to my discourse analysis in later sections.

In the third section, I will begin a focused discourse analysis of guji in Quzhou in the late imperial and mid Republican eras of China, aiming to display its dynamic categorization and boundary negotiation of the past in the local past. First, I shall examine how guji had been categorized and recategorized in the local gazetteers of Quzhou in different ages. This reveals that there was no standardized framework to coerce the Chinese thinking of what guji could be. How it might be categorized was open to negotiation. In other words, the boundaries of guji were not fixed, but traversable. To further illustrate this understanding, I will then delineate the remembrance of natural existence, including bodies of water, trees, and stones, as guji in historical Quzhou, unpacking the meaning-making process through which they were transformed into culturally significant sites of memory about human figures and their deeds.

The fourth section will be devoted to the issue of materiality or physicality in Quzhou’s historical discourse of guji. I will show that very often materiality was not a concern. When it was, the meaning-making of materiality in the guji discourse would be at odds with today’s AHD. Most fundamentally, it was the Chinese Li (礼) thinking that shaped how the physical or material existence of a guji was meaningful. For that matter, guji might engender alternative cultural politics of the past. In addition, I will examine how sites, either with or without identifiable material remains, were remembered as guji in historical Quzhou.

Section 5 will offer a holistic view of the Chinese guji discourse through a focused case analysis of a particular guji without material remains, the House of Yin Hao. Specifically, I will conduct a cultural-historical discourse analysis of this guji in the local gazetteers of Quzhou. I shall demonstrate that most of the features or understandings of guji revealed in the previous sections, such as the neglect of materiality, meaning-making through association with historical figures and their deeds, poetry from the past as a source of meaning, and the importance of site tracing, can and usually do converge.

In the concluding section, I place my analytical findings and arguments in this Element in philosophical (and, occasionally, theological) perspectives. Reflecting on the existence of heritage in words, and the use of heritage as the use of language, I bring the cultural-historical understandings of guji in Quzhou to the global dialogue on what heritage is and does. It is hoped that readers will be stimulated to imagine how many different cultural words or concepts there have been in the world throughout human history.

2 Guji Present and Guji Past

He assumed that words had kept their meaning, that desires still pointed in a single direction, and that ideas retained their logic; and he ignored the fact that the world of speech and desires has known invasions, struggles, plundering, disguises, ploys.

At the outset of his essay “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” Foucault critiques the linear perspective underlying the German philosopher Paul Rée’s history of morality, pinpointing his misconception that words, desires, and ideas are consistent or unwavering. In this section, I examine the Chinese word guji as a cultural concept of heritage and the ideas it has sustained. As Foucault warns, the meaning of this Chinese word and the logic of ideas it holds might not be static or constant. Presumably, it has undergone meaning transformations throughout time, especially when China began to embrace Western modernity to reshape historical consciousness and relationship with its history around the turn of the 20th century (see Huang Reference Huang1997; Wang Reference Wang2001). For that matter, I first look into the contemporary Chinese conceptualization of guji and then investigate how guji was understood in historical eras when the modern Western historical consciousness had not yet taken control of Chinese historical and historiographical practices.

The Contemporary Idea of Guji

In the contemporary Chinese context, guji is understood as a synonym to wenhua yichan (文化遗产) – the Chinese term for cultural heritage. Although in everyday interactions, guji is more frequently heard, these two terms may be used interchangeably in most situations. In Chinese dictionaries and encyclopedias, guji is usually defined as “the remains of ancient times, referring mostly to ancient architecture.”Footnote 2 Baidu Encyclopedia, the Chinese counterpart to Wikipedia, equates guji to “wenwu baohu danwei” (文物保护单位), a term now officially translated as “unit of cultural heritage.”Footnote 3 Let us look at how guji is explained in this most popular Chinese online encyclopedia:

Guji (Wenwu baohu danwei) is historic, cultural, architectural and artistic heritages or sites left by the ancient people. It includes ancient architecture, traditional settlements, ancient cities and streets, archeological sites, and historic and cultural remains. It may be significant in terms of politics, defense, religion, sacrifice, inhabitation, daily life, entertainment, labor, society, economy, education, etc. It functions to make up for the shortage of written, historic and other documentation. (My translation and emphasis)Footnote 4

As can be seen, guji is clearly stated as “historic, cultural, architectural and artistic heritages or sites,” including “ancient architecture, traditional settlements, ancient cities and streets, archeological sites, and historic and cultural remains.” This conceptualization of guji is in line with UNESCO’s definition of (tangible) cultural heritage. As defined in the World Heritage Convention, “cultural heritage” includes:

monuments: architectural works, works of monumental sculpture and painting, elements or structures of an archaeological nature, inscriptions, cave dwellings and combinations of features, which are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

groups of buildings: groups of separate or connected buildings which, because of their architecture, their homogeneity or their place in the landscape, are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science;

sites: works of man or the combined works of nature and man, and areas including archaeological sites which are of outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological point of view.

In the Chinese legal framework for heritage protection, the term wenwu (文物) serves as the standard designation. Wenwu is classified into two categories: movable and immovable. Immovable wenwu that has been inscribed by government authorities is referred to as wenwu baohu danwei (文物保护单位), commonly translated as “unit of cultural heritage.” This category encompasses (1) ancient yizhi (遗址, sites), tombs, architectural structures, cave temples, stone carvings and murals, and (2) modern historical sites, objects, and buildings associated with significant events, movements, or figures. The concept of wenwu baohu danwei bears a strong resemblance to contemporary ideas of wenhua yichan (cultural heritage) and guji in China.Footnote 5 This is why these terms are used interchangeably in sources such as Baidu Encyclopedia and in a variety of other public contexts.

It should be pointed out that neither guji nor wenwu in traditional China can be equated to what is now termed cultural heritage. As Wang Shu-li (Reference Wang, Stolte and Kikuchi2017) has contended, it was under Western influence – largely through Japan as an intermediary in the early 20th century – that the concept of wenwu underwent a historical transformation to encompass anything of historical or aesthetic value and thus to be often used as a substitute for cultural property or cultural heritage. In far ancient China, wenwu was initially a term to denote significant objects in ritual systems, functioning as symbols of political power and hierarchical relations, and since the Song dynasty (960–1279) it was expanded to include various kinds of ancient objects for virtue and self-cultivation. Its modern transformation into an equivalent to cultural heritage was the result of a translingual practice (Liu Reference Liu1995) that regenerates new meanings of old words through translating ostensible equivalences from the West (see also Wang & Rowlands Reference Wang, Rowlands, Geismar and Anderson2017: 268–70).

This is also true to the concept of guji. The contemporary definition of guji as above outlined can be understood as a translation of or substitute by the modern discourse of cultural heritage from Europe (Li Reference Li2005). China ratified the World Heritage Convention in 1985, and the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004. Now, the country ranks number one in both the World Heritage List and the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and there are numerous properties and elements on its domestic heritage lists sanctioned by the central, provincial, municipal, and county authorities. Nonetheless, the notion of heritage in contemporary China is an imported concept or, in an expression coined by the eminent 20th-century Chinese writer Lu Xun (1881–1936), “domestically made imported product” (自造的舶来品) (Lu Reference Lu and Xun1973: 48). Chinese heritages are “made in China,” but their “brand” and fundamental logic are global or, in most cases, Western. Professionals and researchers have translated concepts, categorizations, codes, criteria, conservation guidelines, laws, policy documents, and research publications from the developed world (Western Europe, the United States, Australia and, more recently, Japan and South Korea) and call on governmental entities and the society at large to learn from them in policy and practice (see Bi et al. Reference Bi, Vanneste and van der Borg2016: Wang Reference Wang, Stolte and Kikuchi2017; Zhu & Maags Reference Zhu and Maags2020). Adams (Reference Adams, Blumenfield and Silverman2013: 277) coins a phrase to speak of such a situation – “Chinese heritage management with Western characteristics.” The contemporary “heritage fever” in China is a process of acquiring and implementing international knowledge and discourse.

Actually, the Chinese began to develop a modern consciousness of conserving and preserving cultural relics and ancient architecture under Western influence since the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some scholars, such as Lai (Reference Lai, Matsuda and Mengoni2016) and Zhu and Maags (Reference Zhu and Maags2020: 29–34), have traced the Chinese “journey of Westernization” in establishing their institutions, legislations and disciplinary knowledge for heritage conservation. Not only were the first Chinese public museums and legal regulations of heritage protection in the late Qing period influenced by the West, but also the academic disciplines and the professional institutions for heritage conservation in the Republican China era were established through translating or imitating Western ones, with efforts initiated by those intellectuals coming back to China with Western university degrees, notably Li Ji (李济 1896–1979) and Liang Sicheng (梁思成 1901–72) (see also Lai et al. Reference Lai, Demas and Agnew2004; Shepherd & Yu Reference Shepherd and Yu2013: 9–10). Then, “much of the twentieth century saw the formation of a heritage conservation system in contemporary China, in close association with the West” (Bi et al. Reference Bi, Vanneste and van der Borg2016: 198), along with the conceptual shifts, institutional developments, and discourse remaking (see Zhu & Maags Reference Zhu and Maags2020: chapters 2–3).

What did guji mean in premodern China before the Western idea of heritage influenced Chinese elites and the public? How is it divergent from the mainstream conception of heritage in contemporary China and the wider world? To provide general answers to these questions, I adopt two procedures of analysis. First, from the perspective of exegetics, I look into some ancient text fragments concerning gu and ji, so that the deeper Chinese understandings of guji may be unpacked. Second, I refer to the small preface (xiaoxu) to guji chapter or volume in some renowned Chinese local gazetteers. From there, expositions of what guji used to mean and how it was valuable can be found.

Guji as Gu and Ji

One of the most esteemed ways of explaining a word in traditional Chinese scholarship is exegetics. Adopting this approach, scholars often dismantle a multiple-character word by tracing the meaning of each of its constituent characters. In this subsection, I try to understand guji through explicating its two constituent characters, gu and ji.

Gu, in its literal sense, means the ancient or the past. In Shuowen Jiezi (说文解字), which is generally regarded as the first Chinese dictionary, Xu Shen (许慎, ca. 58 BCE–ca. 147 BCE) interprets this character as “gu” (故) or raison d’être (Xu & Duan Reference Xu and Duan1981: 88). Duan Yucai (段玉裁, 1735–1815) explains, “Raison d’être refers to the whys and wherefores for things, which are all based on gu (the past). That is the reason why this interpretation—‘Gu, raison d’être’ is offered” (88). To further explicate gu, Duan Yucai presents two more quotations: “the heaven is gu; the earth is jiu (long-lasting)” from a most ancient Chinese historiography Yizhoushu (Book of Zhou), and “recollecting gu is in accordance with heaven” from Zheng Xuan’s (郑玄, 127–200) commentaries on a pillar Chinese classic Shangshu (Book of Documents). From these meaning expositions, it is not hard to see that gu had been highly valued in traditional China. The understanding of gu served as an essential entrée to the raison d’être of things in the world. Gu was also regarded as being connected with Tian (天) or Heaven – the highest being that humans on Earth should follow its way to act and live in Chinese cultural thinking (see Chan Reference Chan2012; Nikkilä Reference Nikkilä1992). Recollecting gu, for that matter, was a way of acting in line with Heaven. It is safe to conclude that gu was regarded as a most crucial matter to explore for the Chinese in old times.

Another important point detected from reading the entry of gu in the Shuowen Jiezi is that gu was conceived of as entwined with language, particularly words from the past. As Xu Shen goes on with his explanation of the character, he states that “in terms of meaning, gu is composed of ‘ten’ (shi) and ‘mouth’ (kou); it means to record earlier words” (Xu & Duan Reference Xu and Duan1981: 88). Duan Yucai elucidates, “It is the mouths that record earlier words. When those [words] have passed down through ten [mouths], a convention is formulated” (88). That is to say, it is through the transmission of words from the past that gu establishes itself.

Let us now turn to the character ji. As in the word guji, ji could be written as either 跡, 蹟, or 迹. Xu Shen brings them together in his dictionary. He explains the first one as “where the steps were” (70). Duan Yucai cites Zhuangzi (369 BCE – 286 BCE), an early master of Daoism, to lead us to think further, “Ji refers to what is produced by the shoes, but is ji simply about the shoes that produce them?” (70) Ostensibly, this is a rhetorical question to say that ji is more than the shoes that produce the footsteps. As human traces, ji is of fundamental value. Duan Yucai refers to the Mao Tradition of PoetryFootnote 6 to expose its deeper meaning, which goes, “non-observation of ji means deviation from the Dao” (70). This suggests that ji was considered to be allegorical to Dao, a primordial concept in both Daoist and Confucian thinking. Dao is extremely challenging to define, yet is often postulated as the fundamental Way by which the world exists, as well as the ultimate human pursuit (Cheng Reference Cheng and Cua2003).

To conclude, both gu and ji were perceived as crucial or fundamental in the Chinese tradition, relatable to and illuminating primordial Chinese concepts such as Dao and Heaven. Gu was considered inextricably intertwined with language and ji with human traces. Such a conceptualization of guji is more explicitly pronounced in the small prefaces (xiaoxu) to guji volumes or chapters in premodern Chinese local gazetteers.

Understanding Guji in the Small Prefaces

A small preface was a common way of commencing a chapter or a volume in historiographic and other genres of writing in premodern China. As Xu Shizen (徐师曾, 1517–80) states, “A small preface is written to prelude a part or part in one’s writing. To differentiate it from the big preface (daxu), such a name is given” (Xu Reference Xu1998: 135–36). Like a big preface or, simply, preface, at the beginning of a work, a small preface is usually intended to articulate the purpose(s) of the volume, chapter, or section of one’s writing. Therefore, by examining the small preface to a guji chapter or volume in premodern Chinese local gazetteers, I will be able to tease out the meaning and value negotiations of guji in historical China.

First, I will look at the small preface to the guji volume in the Guangdong Provincial Gazetteer compiled in the Yongzheng reign (1723–35) of the Qing dynasty. It reads as follows:

Does the transmission of gu rely on ji? Or vice versa? Since the beginning of heaven and earth, [there have been] big rivers and mountains, remote rocks, and gullies. How can they not be called gu? But they are not ji. Ji are the traces and remains of the forerunners’ tracks and ruts. That is why it is called ji. If so, when is not a time ji comes into being? There were places the renowned officials and ministers had climbed up for sightseeing, places where the literati and poets left their words, and numerous daises, pavilions, stone tablets. They were shining for a while, yet nothing would remain after they were demolished. All these are ji, not gu. Only those like the Jiucheng Dais, the Post of the General Fubo, the Touyanchenxian Shore, the stream called Eyu (crocodile), the mountain peak named Baihe (white crane), Across even thousands of years, those who behold them linger around in reflection, unable to depart. As for the traces of Buddhas and deities, such as the Fuqiuzhangren, the Zhumingbaopu, and the Caoxidajian, they, though bizarre ji, share the same essence of being gu. [古以迹传乎? 抑迹以古传乎? 自开辟以来, 高山大川, 幽岩邃壑, 岂不称古? 而非迹也。迹也者, 前人所留之轨、所履之辙而迹遗焉, 故曰迹也。顾迹亦何时蔑有? 名臣巨卿之所登览, 骚人词客之所留题, 台榭碑铭非不林立, 然而当时艳之, 没即已焉, 则又迹也, 而非古也。惟夫九成之台, 伏波之柱, 投砚沉香之浦, 溪记鳄鱼, 峰名白鹤, 千百世下, 见者犹低回留之不能去。至于梵迹仙踪, 若浮丘丈人、朱明抱朴、曹溪大鉴, 其迹虽殊, 而古则一也。]Footnote 7

Here the characters gu and ji are explained to delimit the meaning of guji. For the then local gazetteer compilers, ji referred mainly to the traces of human activity, rather than the remains of a physical structure; those that were not associated with human or divine beings could not be regarded as guji. Apparently, the globalized concept of cultural heritage and the contemporary idea of guji are different, as they speak primarily of the material remains inherited from the past. In the same vein, the idea of guji as presented in this small preface distinguishes itself from the contemporary notion of “natural heritage” that underlines the ancientness of physical or biological formations (UNESCO 1972: 3). As clearly stated, natural beings without human or divine traces could not be remembered as guji, no matter how far back in time they might be dated. Nonetheless, if they were known for having association with the traces of renowned human figures or divine beings, they could well be guji.

A further point revealed in this small preface is that guji was not simply about time depth or the pastness, but also about what values it might have in the present. As is known, presentness has been a key issue in both the authoritative idea of heritage and critical heritage studies. For the former, the presentness of heritage is manifested through the so-called historic, artistic, and technological values for the human race. For the latter, heritage presentness is perceived predominantly from a political point of view, as it is a site of identity, ideological, and/or rights contestations in the present (see, e.g., De Cesari Reference De Cesari2019; Hall Reference Hall1999; Harrison Reference Harrison2010; Littler & Nadioo Reference Littler and Naidoo2005; Losson Reference Losson2022; Smith Reference Smith2004; Waterton Reference Waterton2010a). While critical heritage researchers treat heritage as “the root of problem” (Harvey Reference Harvey2024: 5) that causes contention and struggle, the Chinese hopefully saw guji as “a part of the solution” (5) for problems in their society and politics. Through guji, they should be able to excite reflections and emotions, primarily respects paid to virtuous individuals in the past. These virtuous figures would usually serve as examples or means for people to reflect on or forward critiques of pertinent problems in the present. This is more explicitly articulated in the Qing dynasty General Gazetteer of Henan, where the small preface to the volume of guji reads:

The junzi (man of great virtue) in the far ancient demonstrated their virtues to benefit people, and their reputations can travel through time. They are not only recorded in the history books. The places they had stayed and visited attract later generations to pay memorial visits and linger around there reluctant to leave. Isn’t that because of the personage of the junzi? The Book of Poetry remarks, “To the high hills I looked; the great way I pursued.” [上古之君子, 德泽加于民, 名声流于时, 匪独垂竹帛炳丹青而已也。其生平所经历与钓游处往往使人凭吊流连而不能去, 岂非以其人哉? 《诗》云: “高山仰止, 景行行止。”]Footnote 8

Here, guji is associated particularly with junzi (man of great virtue) in the far past. It is their virtuous deeds and reputations that generate an aura on a guji and evoke emotions in visitors. With these emotions, visitors would linger around the guji wanting not to depart. Perceivably, these emotions or feelings were admiration and respect. This is confirmed by the ending quotation from the Book of Poetry. The most well-known Chinese historian Sima Qian (司马迁, ca. 145 BCE – ca. 87 BCE) also cited this when he concluded his narrative of Confucius in the Shiji (Records of the Great Historian) (Sima Reference Sima1959: 1947) to show his deepest esteem to the ancient sage or junzi It can be said that the affective feelings toward ancient junzi bridges the past and the present in guji. As a phrase in the small preface to the guji chapter in the Jiangnan General Gazetteer (Jiangnan Tongzhi) goes, through guji, “feelings get across a hundred decades to be fused with those in the past.”Footnote 9 Interestingly, a turn to emotions and affects is emerging in critical heritage studies in recent years. Scholars have shown how heritage and museum visitors’ feelings and affective responses are entangled with identity politics or family attachment in heritage meaning-making (Kearney Reference Kearney2009; Marchant 2019; Smith Reference Smith2020; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Wetherell and Campbell2018; Tolia-Kelly et al. Reference Tolia-Kelly, Waterton and Watson2017; Zhang Reference Zhang2020). The affectivity of guji in premodern Chinese contexts, as epitomized in the previous quotation, was about identification with certain individuals of virtue in history, rather than with a present community one belongs to, such as race, nation, culture, ethnicity, lineage, or family. In other words, guji was linked to an alternative politics based on feelings of respect and admiration toward the past, not the present recognition or inclusion of particular communities (cf. Smith Reference Smith2020).

Related to such affective bonds across time directed to virtuous historical figures, guji was also meaningful in some other ways. For example, as the small preface to the guji chapter in the General Gazetteer of Jiangnan goes on to state, it “can also be of help to guan (观) and xing (兴).”Footnote 10 To understand this, we need to see what guan and xing mean in premodern Chinese contexts. Duan Yucai interprets guan by referring to The Guliang Commentaries on the Spring and Autumn Annals, stating, “Towards common matters, we say shi (视, see or watch); towards extraordinary matters, we say guan”(Xu & Duan Reference Xu and Duan1981: 408). If this explains guan as a particular kind of looking or observing, the Kangxi Dictionary, a celebrated Chinese dictionary compiled in 1716, directs us to the deeper connotations this Chinese character has. Under its entry of guan, one reads a quotation from the leading Song-dynasty scholar Zhu Xi’s (朱熹, 1130–1200) comments on the I Ching (Book of Change) – “Guan means having something central and correct to show to others, and thus to be looked upon by them” (Zhang Reference Zhang2002: 1112). This suggests that guan is a value-laden act of observing and that what is exposed to guan should be the right and virtuous. With this understanding, it becomes clear why guji could assist guan. As pinpointed previously, guji was considered to be meaningful for the historical figures of virtue and later generations’ affective and emotional visits aroused by their admiration and respect for those virtuous individuals in the past. In this sense, guji could certainly be places upon which guan occurs. Through the guan of guji, one would be led to the virtuous historical figures, looking upon them and learn to be a junzi.

Let us move to the word xing. In the Commentaries on Shuowen Jiezi, Duan Yucai remarks, “Among the six types of poetry in the Zhouli, there are what is called bi and what is called xing. Xing is to embed [our] thoughts about an event in the [poetic] speaking of things” (Xu & Duan Reference Xu and Duan1981: 205). For the Chinese literati in premodern times, the connection between guji and poetry is intimate. On the one hand, when visiting guji, they often wrote poems about or for it. On the other hand, in documenting guji in local gazetteers, travel writing or other forms of work, poetry has an important role to play (Hou Reference Hou2019; Wang Reference Wang, Zeitlin and Liu2003). By means of xing, the poet can lead people to more profound meanings and concerns. The Qing Chinese scholar Yao Chenxu’s (姚承绪) Wuyue Fanggu Lu (吴越访古录 Records of Visiting the Past in the Wu and Yue regions) well epitomizes this. In that work, which intends to document guji in Wu and Yue (roughly, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Shanghai today), he amassed 546 poems of his own for the task. Cheng Tingwu (程庭鹭), a friend of the author, exposes in the preface to the book the deep meaning underlying such poetic writing of guji:

Places are to render known human beings, and human beings are to render known places. [This volume] demonstrates the author’s capacity in reading humans and expounding the world. It brings to light what is obscure and makes manifest what is minute, not simply a work to show off poetic talent.

In this perspective, guji can be places that endorse the full play of xing. When reading a poem about a guji, one appreciates not only the poet’s literary talent but also the profound and delicate meanings beneath the poetic lines to understand the past and the present human world. Through such poetic writings or xing, both the guji it describes and the historic figures it commemorates get passed down to later generations.

To synthesize the insights gained in this macroanalysis of guji, I reiterate four main divergences between this repressed Chinese concept and the mainstream conceptualization of heritage today:

(1) Guji is predominantly about human and, sometimes, divine beings. It is their deeds and virtues that render guji meaningful and appealing to people. As such, it differentiates from the universalized notion of (tangible) cultural heritage, which rests heavily on the material remains of the past and the so-called innate values within its materiality or physicality.

(2) Guji does not include pure natural creations. What is called “natural heritage” today could not be remembered as guji in traditional Chinese contexts. However, this is not to mean that the natural beings could not be guji. A stream or a mountain peak might fall into the category of guji if they have traces of memorable human or divine beings.

(3) Guji is not simply a matter of the past; presentness is its overriding concern. Different from our concern over the presentness of heritage as a site of political control and contestation, guji is deemed to be a resource for critiquing or rethinking the present through value-laden acts of guan (looking or observing) to learn from the right and the correct, as well as the affective bondage it establishes with historical figures of virtue.

(4) Guji is also linked to language, especially poetic language that embodies xing to negotiate delicate and profound meanings concerning the present. This is still neglected in contemporary heritage practices, though critical heritage researchers have problematized the language of present experts and policy texts.

In the ensuing sections, I will present cultural-historical discourse analysis of guji recorded in Quzhou local gazetteers to demonstrate how the Chinese represented, constructed, and made meaning of the past within this forgotten cultural discourse of heritage. With different focuses, they serve as a crystallization of the fundamental logic of ideas associated with guji.

3 What Can Guji Be? The Categorization and Boundary Negotiation of Guji

[A]s I read the passage, all the familiar landmarks of my thought – our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography – breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things, and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten with collapse our age-old distinction between the Same and the Other.

As Foucault has shown in many of his works (Reference Foucault1972, Reference Foucault1977, Reference Foucault1989), debunking the categorization or order of things under a notion can be an expedient means to unravel knowledge production and modes of thinking. It is a fertile approach to studying how a concept or an object is discursively constructed to shape the ways we think and act. In this section, I explicate the categorization of guji in Quzhou from late imperial to mid Republican periods (specifically, 1500s–1920s). By examining how guji is categorized, including how natural beings, such as trees and stones, could be classified into its realm, I will show, from a particular angle, alternative ways of constructing the past in a specific local-historical context, and thereby stimulate reflections on contemporary heritage research and practice that usually presuppose a system of categorization endorsed by international authoritative organizations, such as UNESCO and International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS).

Categorizing and Recategorizing Guji

In Quzhou, before the modern Western ideas of history and historic conservation had become decisively influential, what could (not) be said in the discourse of guji? How did guji as a discourse order or classify things in Quzhou from late imperial to mid Republican eras of China? With these questions in mind, I have analyzed the seven premodern local gazetteers from a cultural-historical discourse perspective. Those questions are then transformed into some more specific ones: In the examined local gazetteers, what is included in the category of guji? What subcategories of guji can be found? What upper category could guji be assigned to? And what categories ran parallel to it? In this section, I report my findings regarding these specific questions from examining the seven local gazetteers of Quzhou one by one. Then I conclude with a discussion on what such historical modes of categorization tell us about the forgotten Chinese idea of guji, particularly in terms of boundary thinking.

In Shen’s gazetteer, guji constitutes a section or category in its seventh volume, which does not have a title (other volumes in the gazetteer are without titles too). Along with guji, the only other section in the volume is siguan (寺观, Temples and Monasteries). That is to say, the compilers of Shen’s gazetteer considered guji a parallel category to that of temples and monasteries, and a higher-level category that can accommodate these two might be difficult, if not impossible, to assign. Furthermore, it is found that guji is further classified geographically in Shen’s gazetteer. Specifically, different guji show themselves under such titles as Fu (府), Xi’an (西安), Longyou (龙游), Jiangshan (江山), Changshan (常山), and Kaihua (开化), which were then counties under the administration of the Quzhou prefecture. This is a common way through which a prefectural gazetteer organizes its records under a category undividable otherwise. Therefore, we can say that the compilers of Shen’s gazetteer did not consider guji as having subtypes, or worthwhile to be classified into subtypes.

In Zhao’s gazetteer, the category of guji is seen in the third volume, Shanchuanji Er (山川纪二, The Record of Mountains and Rivers II), with such parallel categories as Jindu (津渡, Ferries), Piyan (陂堰, Lakes and Weirs), and Tangjin (塘井, Pools and Wells). In the section on guji, one finds almost the same geographical subclassification as seen in Shen’s gazetteer. This, again, means guji was not able or worthwhile to be further divided into subtypes for the compilers of Zhao’s gazetteer.

A somewhat different picture unfolds in Ye’s gazetteer. In the volume Yudi Zhi (Geographic Records), records of guji constitute an individual chapter, along with parallel chapters such as Xingye (星野, Hoshino), Shengzhai (圣宅, The House of the Sage’s Descendants), Jiangyu (疆域, Territory), Yange (沿革, Historic Transitions), Xingsheng (形胜, Landscapes), Fangxiang (坊乡, Urban Neighborhoods and the Countryside), and Yandu (堰渡, Weirs and Ferries). Although under the chapter of guji is, again, a geographical subclassification, as seen in the two earlier Quzhou gazetteers mentioned, in the table of contents of Ye’s gazetteer, ten subtypes are named under the category of guji: Cheng (城, Cities), Zhai (宅, Houses/Mansions), Lou (楼, Towers), Ge (阁, Pavilions), Ting (亭, Kiosks), Tai (台, Daises), Tang (堂, Halls), Miao (庙, Temples), Ci (祠, Memorial Temples), and Mu (墓, Tombs) (Lin et al. Reference Lin and Ye2009: 365). This means that for the compilers of Ye’s gazetteer, guji could be further classified into these different subcategories.

Surprisingly, no specific volume, chapter, or section on guji is identified in Yang’s gazetteer. However, this does not mean that what is recorded under the category of guji in the earlier local gazetteers of Quzhou is excluded from this local gazetteer. Rather, they are scattered in several different volumes of it, such as Shanchuan (山川, Mountains and Rivers), Xieyu (廨宇, Government Buildings), Fangxiang (坊巷, Neighborhoods and Alleys), and more. Thus, it is fair to say that, in Yang’s gazetteer, guji as a category is buried or dissolved.

In Chen’s gazetteer, a chapter on guji is located in the volume of Shanchuan, along with parallel chapters Zhi Shan (志山 Recording Mountains), Zhi Dongyan (志洞岩, Recording Caves and Rocks), Zhi Chuan (志川, Recording Rivers), Wuchan (物产, Natural and Agricultural Products). In the chapter of guji, there are no further subcategories given.

Finally, in Yao’s gazetteer and Zheng’s gazetteer’ guji has the privilege of constituting an independent volume. While the former does not encompass any subcategories of guji, six of them are found in the latter gazetteer. They are, in sequence: (1) Gucheng (故城, Ancient Cities), (2) Jiushu (旧署, Old Official Seats), (3) Fangxiang (坊巷, Blocks and Alleys), (4) Ta (塔, Pagodas), (5) Zhaidi Yuanting (宅第园亭, Mansions, Gardens and Pavilions), with Loutai Chitang (楼台池塘, Towers, Daises, Ponds, and Pools) supplemented, and (6) Zhongmu (冢墓, Tombs).

From these findings, it becomes clear that the classification of guji was not static or rigid in Quzhou from the 1500s to the 1920s. To which upper category guji should belong and how it could be divided into subcategories was rather elastic. With the vicissitudes of time, local gazetteer compilers might have varying understandings or considerations about their guji documentation and thus chose to order it in quite different manners. In other words, how guji should be classified or ordered was open to negotiation for the premodern local gazetteer compilers. There was no standard for them to follow. As such, it contrasts with UNESCO’s World Heritage framework, as well as the national and local heritage frameworks in different countries forged with direct or indirect influence from the World Heritage framework. Today, in China and the wider world, heritage is commonly perceived as a system that consists of cultural heritage, natural heritage, and cultural landscape. Other categories would be extremely hard, if not impossible, to get in. Furthermore, each of these subcategories of heritage is clearly defined to exclude one another. They are further separated into definable subtypes, and those subtypes are classifiable as well. For example, we divide cultural heritage into tangible and intangible cultural heritage, and tangible heritage into monuments, sites, and groups of buildings. Such a systematic categorization of heritage has been taken for granted in practices and most of our research. It serves as basic or fundamental knowledge that coerces our thinking of and actions upon heritage. In recent critical heritage studies, the nature–culture divide in this system of heritage conceptualization continues to be criticized, even though the category of cultural landscape was added into UNESCO’s world heritage framework in 1992. The deep root of this problem, as critical researchers have pointed out, is the Western dualist thinking that separates a wholeness into two binary parts (see, e.g., Brown, Reference Brown, Brown and Goetcheus2023; Harrison Reference Harrison2015; Katelieva et al. Reference Katelieva, Muhar and Penker2020).

With this analysis of guji categorization and recategorization in historical Quzhou, what I can add is that the system of heritage is problematic in that it sets up clear-cut boundaries and discards relational, dynamic, and transformative thinking. In the Chinese cultural context, dual categorizations are common. A fundamental one is the yin–yang thinking, which orders the world and matters therein into two categories, yin and yang. However, yin and yang are not separable, definite categories that exclude one another; they are rather dynamic and relative. Yin and yang are “experienced as a matter of degrees of contrast,” and they are divided “based on our limited experience and special ends from our understanding of yin and yang as cosmic forces and states of becoming” (Cheng Reference Cheng and Mou2008: 75; see also Graham Reference Graham1986). Furthermore, “yin and yang are related in many intimate, reciprocal and interactive ways: yang can be said to bring out yin, just as yin can be said to bring out yang”; they are “mutually supporting, transforming, balancing, enhancing and furthering of the new” (Cheng Reference Cheng and Mou2008: 75; see also Fang Reference Fang2012). The boundary between yin and yang is open and changeable. In the same vein, the boundaries of guji are also dynamic and open to negotiation. It could be categorized and recategorized differently throughout time.

I should note that I am not suggesting a complete absence of convergence in the ways how guji was classified across time. As described earlier, some similar subtypes of guji are seen in Ye’s gazetteer and Zheng’s gazetteer. What I hope to contend is that the then local gazetteer compilers had the privilege to express different understandings in compartmentalizing guji, without a standardized system of classification to coerce their thinking. Through designing their categorizations of guji with a similar basic idea of what it could and could not be, the local gazetteer compilers might extend intellectual dialogue with those doing parallel projects in the past and in the future. This is clearly articulated in the section of Fanli (凡例, Principles of compilation) of Chen’s gazetteer:

The ways of naming and grouping are generally similar in different prefectural and county gazetteers. Divergences and distinctions occur mainly due to diverse understandings. They are not deliberately made to look different.Footnote 11

A more elaborate expression of this is found in the Fanli section of Zheng’s gazetteer:

Chen’s gazetteer places guji in the volume of Mountains and Rivers, which might make it oversimplistic. Yao’s gazetteer has recorded more [guji]. I have collected even more and attempted to trace the provenances and transformations they have gone through. Therefore, I give guji an individual volume, so as to satisfy the desire of later generations for studying the past.

Here, Zheng Yongxi extends dialogue with earlier local gazetteer compilers, arguing that guji should not simply be a subcategory of Shanchuan, but needs to be an ultimate rubric to include more. His treatment of guji as a category was based on what he had found in his research, as well as his understanding of later generations’ expectation of guji as a resource for studying the past or, rather, his own expectation of guji as such a resource for later generations. In this manner, his dialogue on (the writing of) guji is directed to both previous- and later-generation colleagues and those interested in studying the past.

Ultimately, it can be said that the categorization of guji was more about boundary negotiation than boundary setting for the Chinese in historical times, which was in line with their yin–yang thinking. Though working to delimit what guji could be and how they could be ordered, it was contingent, dynamic, and open to dialogue. Such a dialogical and dynamic boundary thinking was not only reflected in the making and remaking of guji categorization, but also in the transformation of non-guji into guji, such as the remembering of natural beings as guji.

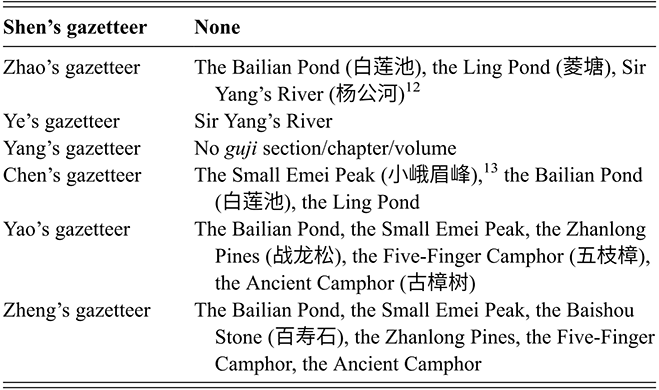

Natural Beings as Guji

As observed in Section 2, guji does not include what is today categorized as natural heritage, but natural beings might be recognized as guji if they could be linked to human or divine figures. From the yin–yang perspective, one can say this is a manifestation of the Chinese understanding of nature and culture as relative, interactive, and transformative binaries, and of guji as having unsettled, negotiable boundaries. Through examination of the seven local gazetteers of Quzhou, I have identified several instances of natural beings recorded as guji. These include specific bodies of waters, trees, and stones. Table 2 catalogs the documented natural elements as guji in the local gazetteers under scrutiny.

| Shen’s gazetteer | None |

|---|---|

| Zhao’s gazetteer | The Bailian Pond (白莲池), the Ling Pond (菱塘), Sir Yang’s River (杨公河)Footnote 12 |

| Ye’s gazetteer | Sir Yang’s River |

| Yang’s gazetteer | No guji section/chapter/volume |

| Chen’s gazetteer | The Small Emei Peak (小峨眉峰),Footnote 13 the Bailian Pond (白莲池), the Ling Pond |

| Yao’s gazetteer | The Bailian Pond, the Small Emei Peak, the Zhanlong Pines (战龙松), the Five-Finger Camphor (五枝樟), the Ancient Camphor (古樟树) |

| Zheng’s gazetteer | The Bailian Pond, the Small Emei Peak, the Baishou Stone (百寿石), the Zhanlong Pines, the Five-Finger Camphor, the Ancient Camphor |

As displayed in Table 2, natural beings as guji were an evolving idea over time. In Shen’s gazetteer, no natural beings were recognized as guji. In Zhao’s and Ye’s gazetteers, only bodies of water could be remembered as guji. Then stones became guji in Chen’s gazetteer. In Yao’s and Zheng’s gazetteers, trees were added in the rubric. Among the three types of natural beings, bodies of water seem to be more readily recognizable as guji. This might be because they were more often associated with historical events, human figures, and their poetic writings than stones and trees were. As the boundaries of guji were not static but open to negotiation, trees and stones could be recognized by this Chinese discourse of “heritage” and recorded for remembrance. It should also be observed that, though the transmission of guji was mostly constant across time, a particular natural being recognized and recorded as guji in one local gazetteer might not always be recognized in another. One can find more or less variations in the documentation of natural beings as guji across the seven inspected local gazetteers of Quzhou. This, again, confirms that there was no standardized idea or uniform definition of guji.

To further explicate such dynamic conceptualization and boundary negotiations of guji, I now turn to examine a few records of trees and stones as found in the guji part of Quzhou’s seven local gazetteers. These two types of natural beings are chosen as they are less likely to be considered as heritage today. To delve into these records can better illustrate the boundary-crossing nature of guji-making.

Trees as Guji

As is known, cultural landscape was added to the World Heritage Convention in 1992 to recognize the combined works of nature and human beings, in response to the critiques against the “nature–culture” dichotomy in Western-originated heritage thinking. However, in this more inclusive heritage framework, can trees or stones be considered heritage? The answer may still be negative. At least, one does not find any trees or stones in the World Heritage List. In the Registration Forms for the Third National Survey of Immovable Heritage (Quzhou) in 2009, no documentation of trees or stones can be identified either. Nonetheless, for people in China and many other parts of the world, trees might be important places of historic significance or sites of memory. For instance, in Kaiija, northwestern Tanzania, there is a huge tree shrine near a village that functions as a compelling mnemonic for the ancient history of Kaiija, and the focal point of identity for social groups such as the royal clan and the Indigenous ironworking clan (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2010). And a few miles north of Cibecue in Western Apache, locals may point one to a huge cottonwood tree at Gizhyaa’itiné (Trail Goes Down between Two Hills). Amusing stories about Old Man Owl and two beautiful sisters who tried to tease the senior amorist with open legs standing in the tree have been told from generation to generation, shaping Apache people’s morality and sense of place (see Basso Reference Basso, Feld and Basso1996: 61–5). In early 20th-century Sweden, “a great and beautiful juniper,” “a giant spruce,” “a ‘troll’ pine,” and “a majestic old oak” were recorded as naturminnesmärker, a concept that means “a combination of nature, remembrance, and mark (trace)” (Sundin Reference Sundin2005: 13). Are these trees heritage? If yes, what kind of heritage are they: natural, cultural, or cultural landscape heritage? For me, they do not seem to be straightforwardly categorizable into the contemporary idea of heritage. Elsewhere, I have examined how in the discourse of guji trees were remembered in Qing-dynasty Hangzhou, the capital city of Zhejiang province. I have argued that tree guji might be more analogous to cultural or cultural landscape heritage, yet still with observable cultural distinctiveness of its own (Hou Reference Hou2019). Here, my examination of trees as guji in the historical context of Quzhou is quite similar, but more focused on individual cases. My aim here is to illustrate the dynamics of boundary negotiation, rather than the more general apparatus of meaning-making in the Chinese cultural discourse of guji.

As shown in Table 2, three tree guji were recognized in Qing and Republican Quzhou, namely, the Zhanlong Pines (战龙松), the Five-Finger Camphor (五枝樟), and the Ancient Camphor (古樟树). My case analysis will be based on the documentation of the first two, through which I hope to further challenge the globalized, standardized framework of heritage categorization and, more importantly, showcase Chinese cultural-historical understanding of boundary negotiation in ordering the past in the local past. The first one is the Zhanlong Pines, a group of pine trees on a famous mountain of Quzhou. In Yao’s gazetteer the record of it reads as follows:

Example 1–1