Introduction

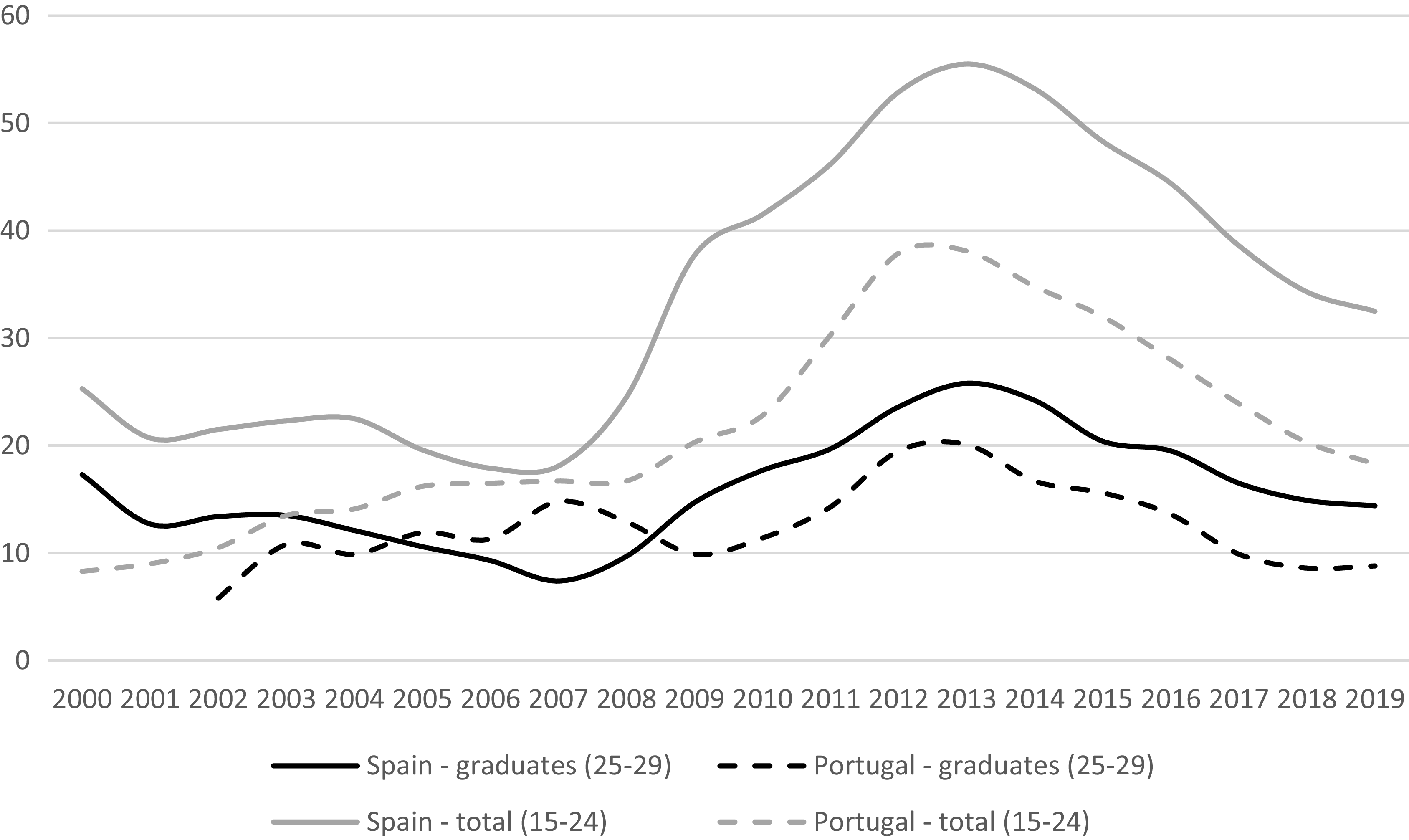

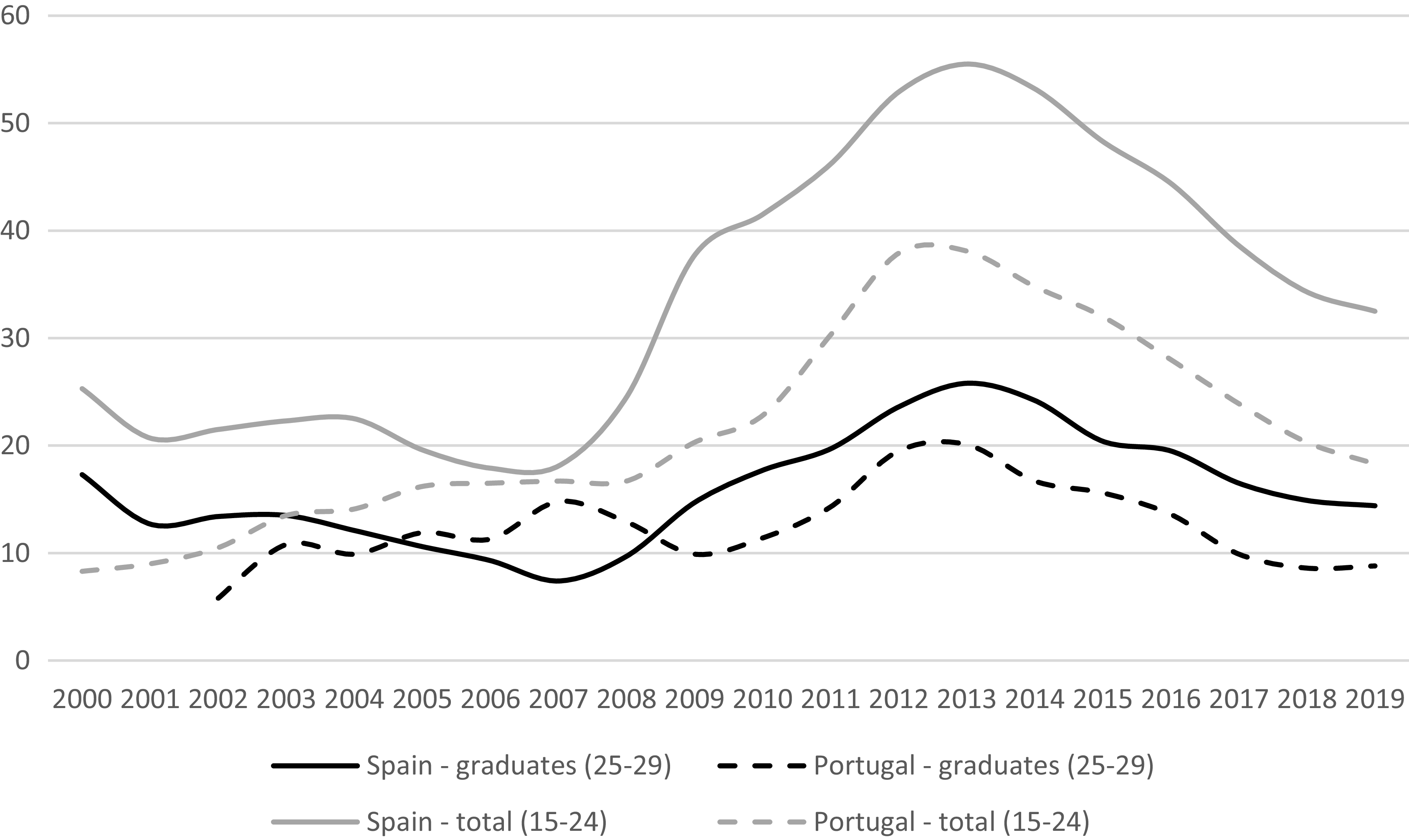

There has been a marked escalation in youth unemployment in numerous European Union (EU) member states over the past two decades, most notably in Southern Europe (Marques and Horisch Reference Marques and Hörisch2020). Whereas the youth unemployment rate in Portugal surged from 8.9% in 2000 to 38.1% in 2013, in Spain, it increased from 26% to 55.5% over the same timeframe (Eurostat 2021). The rising youth unemployment rates have highlighted the imperative for public policies designed to enhance the employability of young individuals. Consequently, there has been a proliferation of active labor market policies (ALMPs) targeting youth across the EU, especially in the wake of the 2008 global economic crisis. Nevertheless, member states have displayed differing priorities in the formulation of these ALMPs. These divergent policy approaches are clearly visible in Portugal and Spain, countries characterized by high youth unemployment rates between 2000 and 2019, including among higher education graduates, as well as similar welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990) and economic growth models (Baccaro et al. Reference Baccaro, Blyth and Pontusson2022). While Portugal’s policy measures concentrated primarily on boosting the employability of higher education graduates, Spain directed its efforts toward reforming its vocational education and training (VET) system. This research aims to shed light on the rationale behind these distinct political priorities by exploring the question: Why did Portugal focus on ALMP for graduates while Spain prioritized VET?

Drawing explicitly on Hassel and Palier’s (Reference Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021) distinction between growth regimes (stable configurations of leading economic sectors, institutional complementarities, and the main components of aggregate demand) and growth strategies (the deliberate policy choices made by governments to stimulate economic development), the key argument of this paper is that national growth strategies fundamentally shape the divergence between Portugal and Spain’s youth-oriented ALMPs. Specifically, Portugal’s strategic focus on transitioning toward a knowledge-based economy has driven targeted internships and innovation schemes aimed at higher education graduates. Conversely, Spain’s sustained emphasis on a dual VET system reflects a growth strategy oriented toward strengthening its manufacturing sector. Thus, this study illustrates how governments’ explicit choices of growth strategies directly inform the orientation and design of their ALMPs.

We systematically examine all ALMPs targeting youth in the two countries from 2000 to 2019. Data were sourced from the LABREF database, which provides a comprehensive compilation of ALMPs across EU member states. Furthermore, the study delineates the growth strategies adopted by successive governments (Hassel and Palier Reference Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021). To achieve this, we analyze the key indicators relevant to the transition toward a knowledge-based economy, complemented by a detailed content analysis of the National Reform Programmes (NRPs) implemented in both countries. Finally, the research establishes the nexus between the content analysis of ALMPs and the growth strategies pursued by respective governments.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. The next section presents a critical review of the extant literature on the determinants of ALMPs and conceptualizes the interrelationship between ALMPs and various economic growth strategies. The theoretical framework culminates in the formulation of the principal hypotheses guiding the study. This is followed by the research design, an in-depth description of the data utilized, and the presentation and discussion of key findings derived from the comparative case studies. The concluding section summarizes the main insights and offers reflective observations on the study’s contributions to the academic discourse.

The determinants of active labor market policies: a review of the extant literature

ALMPs comprise a variety of government interventions designed to enhance the employability of unemployed individuals and facilitate their reintegration into the workforce. The typology of ALMPs proposed by Bonoli (Reference Bonoli2010: 439–443) identifies four main dimensions: incentive reinforcement, which strengthens work incentives through benefit conditionality or wage supplements; employment assistance, which focuses on job-search services and placement support; occupation, which encompasses measures directly subsidizing employment; and human capital investment, centered on training and skill acquisition. This framework provides policymakers and researchers with a nuanced understanding of ALMPs, enabling them to differentiate clearly between interventions designed to reinforce work incentives and those aimed primarily at skill development. This paper concentrates on the latter three dimensions (employment assistance, occupation, and human capital investment) due to the relatively limited relevance of incentive reinforcement measures for young people. Youth labor markets have typically restricted access to unemployment benefits, particularly within Southern welfare regimes, where entitlement to these benefits is often contingent upon prior social security contributions (Ferrera Reference Ferrera1996).

The prominent role accorded to training within human capital investment is a particularly contested aspect of ALMPs; for instance, internships are recognized as part of the ALMP repertoire. Nevertheless, certain training initiatives, such as broader vocational education programs, extend beyond the traditional scope of employment policies, which have historically prioritized direct job placements and work incentives. Notwithstanding, compelling arguments justify their inclusion. Since their pioneering introduction in Sweden during the 1950s, ALMPs have consistently emphasized human capital investment, particularly through extensive vocational training schemes, thereby establishing upskilling as a fundamental element of the Nordic approach to labor market policy (Swenson Reference Swenson2002: 275). International organizations, including the OECD (2006) and the European Commission (2004), have repeatedly emphasized the significance of training in fostering long-term employability and addressing structural labor market mismatches. Furthermore, scholars of social investment and flexicurity stress that training initiatives not only facilitate individuals’ reintegration into employment but also equip them with the skills required to prosper within a rapidly evolving labor market (Wilthagen and Tros Reference Wilthagen and Tros2004; Morel et al. Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012). Consequently, despite their broader remit, training measures remain pivotal to the efficacy of ALMPs by ensuring workers maintain the competencies needed to remain competitive and adaptable. This conceptualization of ALMPs provides the analytical foundation for the discussion presented in this paper.

Although we adopt this approach, it does not follow that all education policies fall within the ALMP framework. We employ an activation‑centered definition of ALMPs: instruments administered through the labor‑market policy apparatus (ministries of labor and/or public employment services), whose primary objective is to enhance the employability of jobseekers or to facilitate the matching of labor demand and supply. Accordingly, we include only training initiatives with a clear activation focus – such as subsidized internships, on‑the‑job training, and apprenticeship contracts – while excluding broad expansions of investment in general secondary or higher education, curricular reforms, and student‑support measures.

The literature on the determinants of ALMPs converges around four main, yet interrelated, explanatory frameworks: partisan politics; policy diffusion and its interaction with domestic institutional legacies; employer involvement; and the role of trade unions.

Power-resource theory was the first to draw attention to the role of partisan politics in shaping ALMP adoption. According to this perspective, strong social-democratic or left-wing parties are expected to support extensive activation measures, viewing ALMPs as universal tools to foster social inclusion and mitigate unemployment, irrespective of individuals’ prior contributions to social insurance (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Iversen and Stephens Reference Iversen and Stephens2008). ALMPs, ranging from training schemes to job counselling, fit neatly within a “social democratic” welfare regime that emphasizes labor market participation for all. However, the insider – outsider paradigm offers an important corrective. Rueda (Reference Rueda2006) argues that center-left parties frequently forge alliances with trade unions to protect the interests of “insiders” (established, unionized workers) while neglecting the needs of “outsiders” (the long-term unemployed). In such contexts, parties may deprioritize ALMPs if they are seen as benefiting outsiders at the expense of insiders. Tepe and Vanhuysse (Reference Tepe and Vanhuysse2013) extend this logic by showing that in environments where insider job security remains tenuous, social-democratic actors may endorse ALMP spending – particularly training and human capital investments – as a second-best mechanism to offer labor market protection when direct job security measures are not achievable.

Building on these insights, Cronert (Reference Cronert2019) demonstrates that partisan differences extend beyond overall spending to the specific types of ALMPs prioritized. Center-left governments typically favor human capital investment and employment assistance programs – such as vocational training, career counselling, and targeted internships – especially those aimed at reducing registered unemployment among individuals already in the labor force. These measures serve both ideological and electoral purposes by reinforcing social inclusion and addressing unemployment head-on. By contrast, center-right governments tend to promote incentive-reinforcement and occupation-focused schemes, including wage subsidies, tax breaks for employers, and support for self-employment. Rather than targeting unemployment per se, these interventions seek to expand the labor supply by activating non-participants and stimulating market engagement through employer demand and entrepreneurial incentives. Thus, the observed divergence between left and right does not simply reflect preferences on spending levels, but a structural difference in policy orientation: the left aims to reintegrate unemployed individuals into work, while the right seeks to mobilize broader participation through market-based incentives. This refined typology clarifies how partisan politics shapes the design of ALMP portfolios, even in countries with similar institutional legacies and macroeconomic pressures.

A second strand of work examines how international organizations, particularly the OECD and the EU, shape national ALMP agendas through policy diffusion. By issuing guidelines, facilitating peer-review mechanisms, and conditioning financial support on activation targets, these bodies exert significant normative and cognitive pressure on member states (Van Vliet and Koster Reference Van Vliet and Koster2011; Armingeon Reference Armingeon2007). During periods of rising unemployment, governments often turn to successful foreign exemplars and adopt OECD or EU-endorsed activation measures in an effort to demonstrate responsiveness and secure legitimacy.

Yet the diffusion process is rarely seamless. Bonoli (Reference Bonoli2010) emphasizes that the uptake of externally promoted policies depends crucially on their compatibility with path-dependent domestic institutions – existing welfare-state architectures, administrative capacities, and social concertation arrangements. In countries characterized by a conservative welfare regime (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990), for instance, a sudden spike in unemployment may prompt increased spending on passive income-maintenance programs, which can crowd out resources for activation measures. Thus, the effectiveness of policy diffusion hinges on the interaction between external recommendations and entrenched national legacies.

A third body of scholarship highlights the central role of employers in both the design and implementation of ALMPs. Departing from portrayals of employers as inimical to welfare expansion, Martin (Reference Martin2004) demonstrates that many firms actively engage in ALMPs, particularly those with built-in workplace components such as on-the-job training and employment subsidies, because they yield direct benefits in skill development and productivity. Employers thus become key co-producers of activation measures, often in collaboration with state agencies. Cronert (Reference Cronert2018) further argues that the presence (or absence) of corporatist structures conditions the degree and form of employer involvement. Where strong tripartite arrangements exist, employers can shape both the funding and the structure of ALMPs to suit their needs, favoring programs that dovetail with firm-level training and recruitment strategies. In settings lacking such frameworks, employer engagement may be ad hoc and limited, leading to a narrower set of activation instruments.

While much of the literature has focused on employers as key co-producers of ALMPs, particularly in the design and delivery of workplace-based training, recent research has increasingly highlighted the role of trade unions in shaping vocational training regimes. Within collective skill formation systems, unions are not merely passive actors but actively contribute to the institutional governance of training, influencing both the structure and content of vocational pathways (Busemeyer and Trampusch Reference Busemeyer, Trampusch, Busemeyer and Trampusch2012). Their involvement is often critical to upholding training standards, ensuring the portability of qualifications across firms and sectors, and balancing the interests of workers and employers. Moreover, unions frequently act as stabilizing agents that foster coordination among firms, thereby preventing the fragmentation of training provision. In this context, their institutional strength and degree of integration into training governance can significantly affect the orientation and coherence of youth-oriented ALMPs (Durazzi and Geyer Reference Durazzi and Geyer2020; Geyer and Durazzi Reference Geyer, Durazzi, Bonoli and Patrick2022). These dynamics may, in turn, shape the broader strategic direction of ALMPs.

These four explanatory frameworks – partisan politics, policy diffusion, employer involvement, and union participation – have each provided valuable insights into the design of ALMPs. Yet their explanatory power in contexts like Portugal and Spain, which share key institutional and macroeconomic features, remains underexplored. This study tests these traditional drivers alongside a fifth hypothesis centered on national growth strategies with the aim of assessing which mechanisms best explain the contrasting trajectories of youth-oriented ALMPs in two otherwise comparable Southern European countries.

Advancing beyond the current literature: examining the relationship between ALMPs and different growth strategies

This section proposes a new driver in the analysis of ALMPs: the relationship between ALMPs and the various growth strategies associated with the transition to a knowledge economy. This perspective is essential because ALMPs are not isolated policies but rather components of broader governmental strategies.

Since the 1990s, the knowledge-based economy has assumed ever greater prominence, with Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) permeating virtually every sector. Yet advanced economies have navigated this transition in markedly different ways, giving rise to distinct “growth regimes” that combine sectoral specializations, institutional complementarities, and demand-side drivers (Hassel and Palier Reference Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021). While debate continues over whether varieties-of-capitalism or post-Keynesian frameworks best capture these differences (Baccaro et al. Reference Baccaro, Blyth and Pontusson2022; Thelen Reference Thelen2019), there is broad agreement that many Southern European economies have long depended on domestic consumption, underpinned by wages and welfare, and that this consumption-led regime has struggled with stagnating growth and mounting public debt, especially since the sovereign-debt crisis.

Hassel and Palier (Reference Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021) make a pivotal contribution by distinguishing between growth regimes – the relatively stable configurations of leading sectors (for example, high-quality manufacturing or dynamic services), institutional complementarities and the main components of aggregate demand – and growth strategies, the purposeful bundles of policy decisions that governments deploy to stimulate growth and employment. They identify five regimes – high-end manufacturing exports; dynamic-services exports; FDI-led export growth; financialization-driven consumption; and wage-and-welfare-driven consumption – and argue that policymakers may adopt strategies that diverge from their inherited regime for ideological reasons or to effect structural change (Hassel and Palier Reference Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021: 24). Crucially, each growth regime corresponds to a characteristic welfare-policy orientation. Hassel and Palier show that social investment – the targeted expansion of education, training and ALMPs to equip citizens for evolving economic demands (Morel et al. Reference Morel, Palier and Palme2012) – is most compatible with a dynamic-services export regime. This insight reveals that even in consumption-based contexts, governments possess genuine scope for policy innovation: by pursuing a growth strategy oriented toward knowledge-intensive services, they can reconfigure welfare and activation measures to foster technological upgrading and economic diversification.

We complement the growth‑strategy perspective with the concept of growth coalitions – cross‑class, sector‑anchored constellations of firms, employer associations, and fractions of labor that sustain the policy mix aligned with a country’s growth strategy. In normal times, such coalitions tend to be insulated from electoral competition and help maintain policy continuity; in moments of crisis, they may shrink or be recomposed (Baccaro and Pontusson Reference Baccaro and Pontusson2022).Footnote 1

To accelerate a shift toward radical innovation, ALMPs must target the actors and sectors at the knowledge frontier. Graduates trained in engineering, science, and technology, together with firms committed to ICT-enabled transformation, require support that extends beyond generic training. Activation measures should dovetail with reforms in research and development (R&D), higher education, and the broader innovation ecosystem. Such coherence enhances both human capital and organizational absorptive capacity, enabling economies to adapt to rapid technological change (Drabing and Nelson Reference Drabing, Nelson and Hemerijck2017).

Although social-investment scholars often praise VET, policies that prioritize dual-system apprenticeships can clash with knowledge-services objectives. Collective skill-formation systems typically require institutional prerequisites, such as high employment protection and robust social-partnership frameworks, that are not aligned with the needs of radical innovation (Busemeyer and Trampusch Reference Busemeyer, Trampusch, Busemeyer and Trampusch2012; Estevez-Abe et al. Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001; Hall and Soskice Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001). Moreover, whereas manufacturing sectors derive direct benefit from VET investments, service-oriented growth regimes demand broader, generalist competencies and cross-disciplinary skills.

The literature remains divided on whether advanced manufacturing nations are now recalibrating toward greater higher-education expansion and R&D investment in response to digitalization pressures (Diessner et al. Reference Diessner, Durazzi and Hope2022; Durazzi Reference Durazzi2023). Some observers argue that countries with strong apprenticeship traditions are simultaneously boosting graduate numbers through partnerships with universities of applied sciences, whereas others emphasize the enduring path-dependence of dual-VET institutions (Thelen Reference Thelen2019: 302).

This debate is less pertinent for peripheral economies, such as those in Southern Europe, where the manufacturing sector depends heavily on foreign-owned firms and therefore much frontier innovation originates abroad.

In sum, our analysis demonstrates that the design of ALMPs is not dictated simply by partisanship, institutional legacies, or employer and union pressures in isolation, but by the broader growth strategies pursued by governments. When a state adopts a knowledge-services strategy, it aligns its ALMPs – through graduate internships, innovation-linked training, and R&D support – to accelerate that transition; when it pursues a manufacturing-export model, it channels activation measures into dual-VET and apprenticeship schemes tailored to industry needs. The recognition of this alignment between ALMP portfolios and growth strategies provides a more comprehensive explanation of policy divergence than any one driver alone and offers policymakers a clear heuristic for integrating activation measures with overarching economic objectives.

The main hypotheses underpinning this study

Based on the literature reviewed in the previous sections, four hypotheses are formulated to explain the varying priorities for ALMPs in Portugal and Spain. These first four hypotheses relate to the traditional drivers identified in the literature, while a final hypothesis draws on the argument presented in the previous section.

H1 (Partisan Politics): Countries governed by left-wing parties will prioritize ALMPs that aim to reduce registered unemployment among core labor-force participants, including human capital investment (e.g. internships and general vocational training) and employment assistance. In contrast, right-wing or conservative-led governments will favor labor supply expansion measures, such as employer tax incentives, promotion of self-employment, and occupation-focused schemes, aimed at activating non-core groups through market-oriented mechanisms (Cronert Reference Cronert2019).

H2 (Policy Diffusion and Institutional Legacies): Member states whose welfare-state architectures, administrative capacities, and social-partnership arrangements align with OECD and EU activation recommendations will exhibit a more rapid diffusion and enduring adoption of comprehensive ALMPs. Conversely, EU member states embedded in the Southern welfare regime will display a slower uptake and may channel resources into passive income-maintenance measures during unemployment spikes (Van Vliet and Koster Reference Van Vliet and Koster2011; Bonoli Reference Bonoli2010; Artiles et al. Reference Artiles, Lope, Barrientos, Moles and Carrasquer2020; Guillén et al. Reference Guillén, Jessoula, Matsaganis, Branco, Pavolini, Burroni, Pavolini and Regini2022).

H3 (Employers’ Involvement): Economies characterized by robust corporatist or tripartite frameworks will feature a higher share of employer-led ALMPs – such as on-the-job training, wage subsidies, and apprenticeship schemes – than those without such institutions, as firms in corporatist settings co-produce policies that directly address their skill and recruitment needs (Martin Reference Martin2004; Cronert Reference Cronert2018).

H4 (Union Involvement): In contexts where trade unions possess strong institutional capacity and are integrated into the governance of vocational training systems, youth-oriented ALMPs are more likely to be oriented toward dual-VET models. In such settings, unions contribute to the coordination, standardization, and quality assurance of training provision, reinforcing collective skill formation principles. Conversely, where union involvement in training governance is limited, ALMPs are less likely to prioritize dual VET and more prone to adopt fragmented or employer-led approaches (Durazzi and Geyer Reference Durazzi and Geyer2020; Geyer and Durazzi Reference Geyer, Durazzi, Bonoli and Patrick2022).

H5 (Growth Strategies): Governments that adopt growth strategies aimed at accelerating the transition to a knowledge-based economy – characterized by explicit support for knowledge-intensive services, ICT, and complementary reforms in R&D and higher education – will design youth-oriented ALMPs that prioritize higher-education graduates and sectors critical to radical innovation (e.g. targeted internship schemes in ICT, engineering, and science fields). Conversely, governments pursuing growth strategies centered on (FDI-financed) manufacturing development will orient ALMPs toward VET measures, particularly dual-VET and apprenticeship contracts, reflecting the skill needs of manufacturing industries (Hassel and Palier Reference Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021; Busemeyer and Trampusch Reference Busemeyer, Trampusch, Busemeyer and Trampusch2012; Estevez-Abe et al. Reference Estevez-Abe, Iversen, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001).

Data and methods

The paper employs a comparative case-study design, examining Portugal and Spain as most-similar cases in which the variation in the dependent variable, the type and content of youth-oriented ALMPs, can be most clearly observed.

Following Ferrera’s classic formulation, Portugal and Spain are classified as part of the Southern welfare regime. In Ferrera’s ideal type, this regime is characterized by (i) Bismarckian, status‑segmented income maintenance combined with Beveridgean/universalist healthcare, (ii) high institutional fragmentation and polarization across occupational schemes, and (iii) a transfer‑centered bias with comparatively large old‑age expenditure and underdeveloped anti‑poverty and family policies. It also relies heavily on households, particularly women, for care provision, often described as “familialism by default” (Ferrera Reference Ferrera1996). In addition, Ferrera highlights a low degree of state penetration in welfare and a collusive public – private mix with clientelistic allocation of benefits. Building on this ideal type, recent comparative work by Guillén et al. (Reference Guillén, Jessoula, Matsaganis, Branco, Pavolini, Burroni, Pavolini and Regini2022) nuances the Southern model by showing systematic within‑group differences. Since the 1980s, Spain and Portugal have combined welfare expansion with institutional recalibration – universalizing healthcare, establishing and strengthening minimum‑income and social‑assistance instruments, and maintaining the old‑age share of social expenditure closer to EU‑15 profiles – whereas Italy and Greece have remained more pension‑centric and institutionally unbalanced. Although post‑2010 austerity produced some downward convergence, Portugal and Spain still resemble each other more closely than they do Italy or Greece. Beyond these similarities, over the past two decades, both countries have experienced a significant rise in youth unemployment, including among university graduates. Youth‑unemployment rates were already high between 2000 and 2007, but escalated sharply after the global financial crisis, persisting as a central policy challenge throughout the period (Figure 1). Our empirical strategy therefore treats Portugal and Spain as most‑similar cases within the Southern European welfare regime, combining their shared welfare characteristics with their parallel challenges of high youth unemployment.

Figure 1. Youth unemployment (15–24 years) and youth unemployment among graduates (25–29 years).

Source: Labour Force Survey (Eurostat, 2021).

The empirical analysis of youth-oriented ALMPs relies on data from the LABREF database (European Commission 2021), which compiles national and EU-level policy measures across member states. We identify 75 youth-targeted policies implemented between 2000 and 2019. This timeframe was chosen for two reasons. First, although LABREF also covers 2020 and 2021, we exclude these years to avoid distortions arising from the COVID-19 pandemic’s exceptional labor-market interventions. Second, 2000 marks the launch of the Lisbon Strategy, providing a natural baseline for analysing subsequent reforms. In addition to LABREF, we conducted a documentary analysis of all relevant legislation and policy documents to ensure a comprehensive understanding of each measure.

To classify these policies, we adapt the typology of Tosun et al. (Reference Tosun, Hunt and Wadensjö2017),Footnote 2 resulting in eight categories: school-based VET; dual VET system; labor-market training and internships; job-search assistance and monitoring; wage subsidies; public-sector employment programs; promotion of self-employment and entrepreneurship; and other. Variations of this typology have been widely used in cross-country comparisons (Marques and Horisch Reference Marques and Hoerisch2019; Marques and Videira Reference Marques, Videira and Jagannathan2021) as they allow for a nuanced, qualitative examination of policy design and strategic orientation.

Programs are coded as school‑based VET or dual-VET system only if enacted via labor‑market policy (and/or financed as activation measures). Purely educational reforms (e.g., general expansion of VET or Higher Education capacity, curricula changes, and student aid) are excluded. Likewise, labor‑market training and internships include only measures delivered through public employment services or ALMP‑dedicated budgets.

Our adaptation differs in three respects. First, we disaggregate Tosun et al.’s “human capital investment” into distinct categories of “school-based VET” and “dual VET system” to reflect the separate pathways offered by in-school training and work-based apprenticeships. Second, we introduced a new category, “promotion of self-employment and entrepreneurship,” which frequently targets higher-education graduates and merits distinct consideration. Third, we removed the “packages” category, instead treating each program as an individual policy. A comprehensive list of policies and coding explanations is provided in online Appendix A.

Finally, we matched each program to the political orientation of the government that enacted it, recognizing that partisanship often shapes ALMP design. We drew on the PARLGOV database (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2021), which classifies the ideological orientation of EU governments throughout the period under study.

To evaluate the growth strategies formulated by each country, we collected and analyzed two types of data. First, we conducted a content analysis of the NRPs developed by each government during the specified period. Introduced in 2005, the NRPs were part of the implementation of the Lisbon Strategy, an EU initiative aimed at transforming the EU into the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world by 2010. The NRPs required EU member states to formulate national action plans outlining specific reforms to achieve the broader objectives of the strategy, which included promoting economic growth, improving employment, and fostering social inclusion. These programs were designed to align national policies with the Lisbon objectives, addressing critical areas such as labor market reform, innovation, education, and environmental sustainability. Later, the NRPs were incorporated into the European Semester, a framework introduced in 2011 to enhance the coordination of economic and fiscal policies within the EU. From 2011 onward, countries were required to submit two documents: the NRPs and the National Stability and Convergence Plans (NSCPs). The NSCPs focus primarily on fiscal policy and are necessary for EU member states to demonstrate their commitment to maintaining sound public finances in accordance with the Stability and Growth Pact. Consequently, the NRPs address policies designed to stimulate economic growth and are aligned with EU strategies focused on growth, such as the Lisbon Strategy and the EU2020 Strategy. Therefore, we considered the NRPs to be a valuable source of information for assessing the growth strategies of each government.

In our analysis, we explored several dimensions in each country to determine whether they pursued distinct growth strategies and how these related to their ALMP priorities. For Portugal, we assessed the presence of internships in official documents, the linkage of graduate-targeted internships to innovation or education, and the degree to which innovation and education were prioritized. For Spain, we examined the prominence of the apprenticeship contract, its specific role in addressing youth unemployment, its association with investment in the manufacturing sector, and any evidence of strategic support for that sector. We also conducted a reverse analysis, considering whether Portugal had prioritized dual-VET, and whether Spain had promoted policies targeting university graduates to support the transition to a knowledge-based economy.Footnote 3 Our content analysis covers the period 2005 to 2019, commencing in 2005 when these documents were first introduced. The full results are provided in online Appendix B.

To complement our document-based content analysis of ALMPs, we benchmark Portugal and Spain across the three dimensions highlighted in Burroni et al.’s (Reference Burroni, Gherardini and Scalise2019) growth triangle: innovation, employment, and education. We adopt the indicator families employed by Burroni et al., restricting our analysis to those consistently available for both countries.Footnote 4 Accordingly, we read the indicator families not only as levels but as a diagnostic of alignment across pillars, a necessary condition for the transition to a knowledge‑based economy and for ALMP returns to materialize.

The following two sections present empirical data on the implementation of youth-oriented ALMPs in Portugal and Spain over the selected period. The analysis is organized into two distinct case studies to enhance clarity. Each section begins with a concise overview of the types of ALMPs implemented, followed by an examination of the strategic direction adopted by the respective governments. It then proceeds to assess the growth strategies pursued during the transition to a knowledge-based economy and concludes with an analysis of how various actors, including political parties and producer groups, positioned themselves in relation to these reforms.

Youth-oriented ALMPs in Portugal and the national growth strategy (2000–2019)

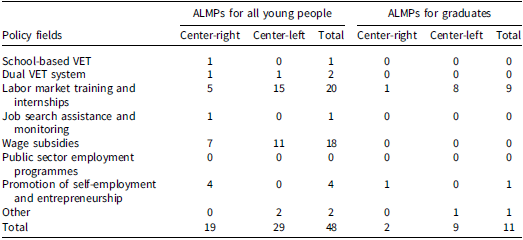

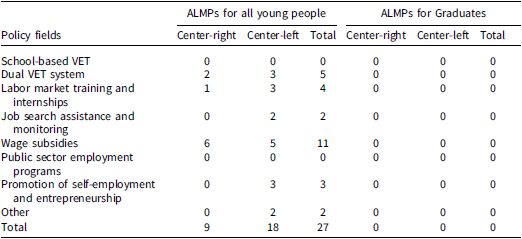

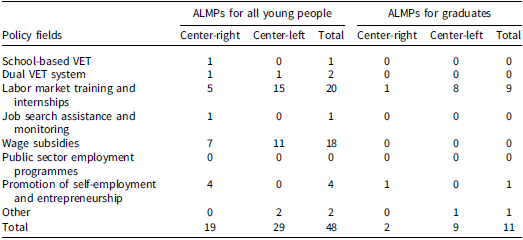

Table 1 summarizes the youth-oriented ALMP measures implemented in Portugal between 2000 and 2019. Although many initiatives fell under labor-market training and internships or wage-subsidy schemes, the substantive content and shifting priorities over time warrant closer examination.

Table 1. Youth-oriented ALMPs in Portugal (2000–2019)

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on the LABREF database (European Commission, 2021).

Note: See Online Appendix A for further details. In the appendix, each policy is coded according to whether it targets university graduates, which political party enacted the reform, and the policy field to which it belongs. Graduate targeting is determined by examining the policy descriptions provided in the LABREF database and cross-referencing them with the corresponding official documents. For party classification, we identify the governing party responsible for the reform and use the PARLGOV database to categorise it as either center-left or center-right.

Scope note: VET categories denote labor‑market instruments (e.g., apprenticeship contracts, PES‑funded bridging courses) and exclude general education reforms.

Between 2000 and 2004, only three policies were introduced, all focusing on extending training cycles and awarding vocational qualifications with substantial instructional hours. These limited measures reflected a broader political agenda aimed at easing young people’s transition into the labor market amid economic stagnation.

The most notable shift occurred under the socialist government that took office in 2005.Footnote 5 From 2005 to 2011, ALMPs targeting graduates became a central priority, forming part of an integrated strategy to accelerate the transition to knowledge-intensive services. However, following the center-right coalition’s electoral victory in 2011, the complementarity between innovation, education, and employment policies was diminished, and graduate-focused schemes subsequently lost prominence.

Between 2000 and 2019, Portugal’s ALMPs featured an unusually high number of measures targeting higher-education graduates, 11 of the 48 programs, underscoring a deliberate political focus. Nine of these schemes were enacted under the socialist government in office from 2005 to 2011, the most prominent being INOV-JOVEM. Instituted by the Portuguese Resolution 87/2005 of the Council of Ministers, INOV-JOVEM formed part of a broader strategy to accelerate the shift toward a knowledge-based economy under the Lisbon Strategy. The programme offered financial support exclusively to small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that hired recent graduates in fields critical to innovation – management, engineering, science and technology – a significant intervention given SMEs’ historically low investment in workforce training despite their economic predominance.

In the same year, INOV-CONTACTO was introduced to fund professional internships abroad in dynamic markets and multinational firms, with the expectation that interns would return to Portugal, thereby bolstering SME internationalization (Portuguese Resolution of the Council of Ministers 93/2005). Positive evaluations of these initial schemes, measured by participant numbers and subsequent long-term SME employment, prompted both an expansion of existing programs and the launch of four additional graduate-focused initiatives: INOV-ART (arts and culture graduates), INOV-VASCO DA GAMA (young managers and entrepreneurs), INOV-MUNDUS (development cooperation), and INOV-SOCIAL (integration into social-economy institutions) (Portuguese Resolution of the Council of Ministers 63/2008; Portuguese Resolution of the Council of Ministers 93/2008). Further measures included an internship scheme for public administration (2010) and a requalification program aimed at up to 5,000 graduates in sectors with limited employability (Portuguese Resolution of the Council of Ministers 112/2009; Portuguese Ordinance 285/2010; Portuguese Decree 18/2010).

The scale of these graduate-targeted ALMPs is striking. Between 2005 and 2007, they served 6,250 participants, approximately 6.5 per cent of all ALMP training beneficiaries,Footnote 6 increasing to 11,966 (18.7 per cent) in 2008–09 and 24,966 (36.6 per cent) in 2010–11 (European Commission 2022). Financial cost data for individual programs are absent from the databases and legislation. However, Costa and Varejão (Reference Costa and Varejão2012: 70) report that the Portuguese Government invested €86 million in INOV-JOVEM and INOV SOCIAL between 2008 and 2010. Considering that total expenditure on ALMPs (training category) in Portugal was approximately €690 million in 2010, a figure encompassing schemes for both younger and older participants (European Commission 2022), the investment in just these two graduate-focused initiatives underscores their particular significance.

The election of a center-right coalition in 2011 marked a strategic pivot. In 2012, the government introduced PASSAPORTE EMPREGO, comprising six types of internships, only one of which was graduate-specific (Portuguese Ordinances 408/2012, 65-B/2013, 225-A/2012). By 2013, all internships were opened to non-graduates, and all INOV programs were discontinued except for INOV-CONTACTO, which was absorbed by the Youth Guarantee (Portuguese Ordinance 204-B/2013). The targeting of graduates was confined to a modest entrepreneurship initiative, PASSAPORTE EMPREENDEDORISMO, characterized by limited sectoral focus, weak innovation linkages, and modest funding (Portuguese Ordinance 370-A/2012). Out of the Youth Guarantee’s €343 million budget, €289 million funded internships and only €23 million were allocated to entrepreneurship support (CESOP 2018). The coalition also launched three universal youth initiatives: a cooperative-entrepreneurship scheme, an agricultural-cooperative investment program, and the Youth Invest start-up fund for unemployed young people (2014). This expansion of eligibility can also be attributed to the sharp escalation in youth unemployment, which reached unprecedented levels in 2013 (Figure 1).

In 2015, a new socialist government led by António Costa, supported by two radical left-wing parties, took office amidst economic recovery and declining youth unemployment. This administration significantly reduced the introduction of new ALMPs and reoriented policy toward promoting permanent contracts and enhancing digital skills among young people.

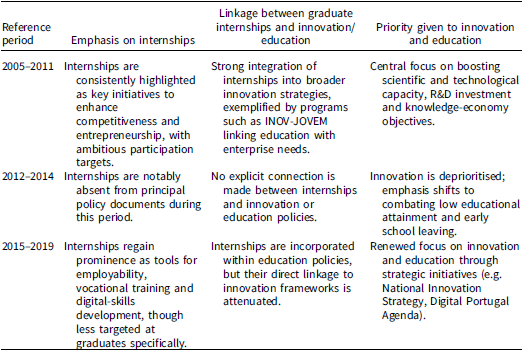

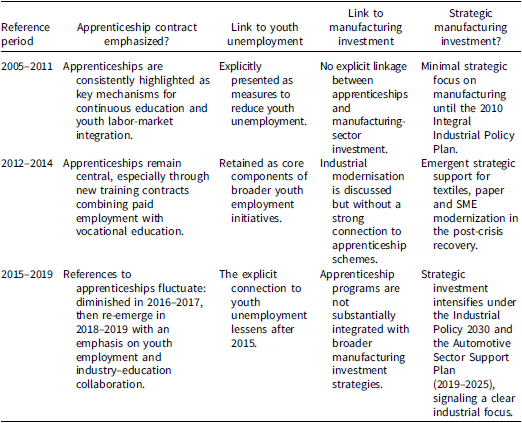

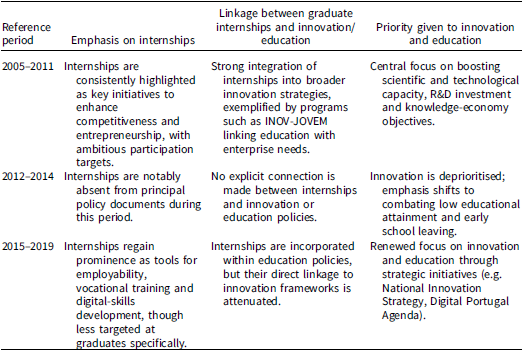

Remarkable disparities emerge when examining how successive governments have managed the transition to a knowledge-based economy. As detailed in the Methods section, we undertook a content analysis of NRPs, the annual documents EU member states submit under the European Semester, which articulate each government’s growth strategy. We also analyzed key quantitative data on innovation, employment, and education. The NRP analysis shows that internships targeting graduates feature prominently in official policy agendas, underscoring their strategic importance. As Table 2 demonstrates, between 2005 and 2011, there was a clear alignment between the presence of graduate-targeted internships, strong linkages to innovation and education, and an explicit prioritization of both innovation and education. By contrast, this alignment disappears in the 2012–2014 and 2015–2019 periods, a finding consistent with our earlier scrutiny of ALMP measures.

Table 2. Content analysis of Portuguese National Reform Programmes (2005–2019)

Source: Portuguese Government (2005, 2008, 2011, 2015–2019).

Notes: From 2012 to 2014, Portugal was exempt from submitting a National Reform Programme under EU requirements due to its external intervention following the 2011 financial bailout. During this interval, the Memorandum of Understanding between the Portuguese Government, the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund effectively replaced the National Reform Programme. Consequently, we used that Memorandum as the basis for our content analysis for the 2012–2014 period. Refer to Online Appendix B for further year-by-year details.

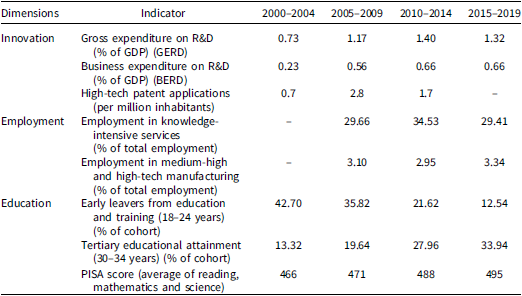

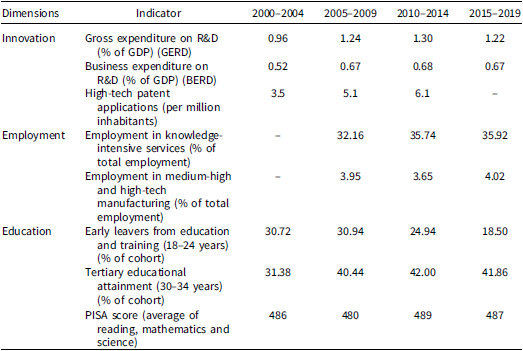

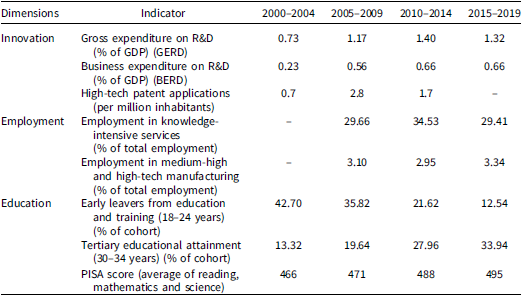

The quantitative data in Table 3 reinforce these observations, charting trends from 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014, and 2015–2019. Innovation indicators progressed markedly between 2005 and 2014: gross expenditure on R&D rose from 0.73 per cent of GDP in 2000–2004 to 1.17 per cent in 2005–2009 and peaked at 1.40 per cent in 2010–2014; business R&D climbed steadily from 0.23 per cent to 0.66 per cent of GDP. High-technology patent applications increased from 0.7 to 2.8 per million inhabitants in 2005–2009, before easing to 1.7 in 2010–2014. Employment in knowledge-intensive services expanded from 29.66 per cent to 34.53 per cent between the same periods, while employment in medium-high and high-technology manufacturing dipped slightly from 3.10 per cent to 2.95 per cent, then rose to 3.34 per cent in 2015–2019. Education indicators also improved: early leavers from education and training fell from 42.70 per cent in 2000–2004 to 12.54 per cent in 2015–2019, and tertiary attainment more than doubled from 13.32 per cent to 33.94 per cent. PISA scores climbed from 466 to 495 over the period. In sum, 2005–2014 witnessed significant gains in innovation and employment metrics, while educational improvements persisted and accelerated in 2015–2019, reflecting a sustained commitment to educational development.

Table 3. Principal indicators assessing the transition to a knowledge-based economy in Portugal (2000–2019)

Source: Eurostat (2024; 2025a–d); OECD (2001; 2004; 2007; 2010; 2013; 2019a).

Notes: “High-tech patent applications” covers data up to 2013; the 2010–2014 average therefore uses only 2010–2013 figures. Employment-by-sector data start in 2008; accordingly, the 2005–2009 averages are based on 2008 and 2009 only. PISA assessments were conducted in 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009, 2012, 2015 and 2018; period averages reflect the available survey years.

Regarding the positioning of different actors within the political cycle from 2005 to 2011, the government emerged as the main driving force, although other actors also supported this policy trajectory. José Sócrates, the Portuguese Prime Minister, asserted that “with the PS, the priority will be investment in knowledge, innovation, and technology” (PS 2005: 3). Reflecting on budgetary priorities in 2009, he emphasized that “investment in science was the only item in the State budget that consistently showed positive and significant progress in terms of national public investment” (PS 2009). By 2008, he observed, Portugal had achieved 1.55 per cent of GDP in R&D investment, “one of the fastest accelerations in development of the past twenty years” (PS 2010). Additionally, members of the government highlighted the link between graduate-targeted internships and innovation investment. For example, Minister Silva Pereira explained that “the INOV-JOVEM programme will cost the State 10 million euros per year in contributions to participating companies with the objectives of reviving the economy, stimulating qualification and innovation in companies, and combating youth unemployment” (Correio da Manhã Reference da Manhã2005).

Regarding other actors supporting these policies, evidence of broad social-partner endorsement is demonstrated by employers’ associations and the General Union of Workers (UGT-PT), as reflected in the inclusion of graduate internships in two Tripartite Agreements. The 2008 Tripartite Agreement on labor market regulation and the 2011 Agreement for Competitiveness and Employment – signed by the Government, all employers’ associations, and UGT-PT – explicitly reference schemes such as INOV-JOVEM as key mechanisms for graduate activation (Economic and Social Council 2008; Economic and Social Council 2011). UGT-PT, for instance, argued that “all unemployed graduates should be entitled to a paid one-year internship, with social security contributions” (Correio da Manhã Reference da Manhã2009).

Center-right political parties also expressed support for these internships, although they noted several problems with their implementation. For instance, during a parliamentary debate on the topic, a Social Democratic Party (PSD) Member of Parliament (MP) stated: “We are once again here to contribute to the integration of young graduates into the labor market by creating incentive mechanisms that encourage companies to hire these qualified human resources” (National Parliament 2006: 5242). In the same debate, a People’s Party (CDS-PP) MP affirmed: “The CDS identifies with the resolution you have just presented because it is indeed something that can contribute to reducing youth unemployment” (National Parliament 2006: 5247).

In contrast, the General Confederation of the Portuguese Workers (CGTP), the Left Bloc, and the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) expressed strong reservations due to the potential for exploitation. The CGTP warned that extended internships could provide firms with cheap labor (CGTP 2011). The Left Bloc accused the government of failing to “defend those who need to be defended, namely unemployed graduates who, in desperation, are even willing to work for free” (Visão 2009). Similarly, the PCP repeatedly condemned the use of internships as a means of promoting precariousness, as illustrated by the following statement from a PCP MP: “This is not a programme for young people. It is a programme for companies, consisting of direct and indirect incentives to businesses.” (National Parliament 2006: 5257).

When viewed in its entirety, three distinct political cycles emerge in the evolution of ALMPs in Portugal, each reflecting a shifting coalition and policy focus. Between 2005 and 2011, a knowledge‑services coalition – comprising core ministries, innovation agencies, SMEs benefitting from INOV‑schemes, and social‑partner backing in tripartite agreements – underpinned graduate‑targeted internships closely tied to innovation and higher education. This period sought to accelerate the transition to a knowledge‑based economy, although CGTP and radical‑left actors opposed these internships on grounds of precariousness. From 2011 to 2014, under a center‑right administration operating under external conditionality, eligibility was broadened, the emphasis on university graduates was reduced, and wage‑subsidy instruments and general internships became the priority, diluting the explicit link to innovation while investments in key indicators slowed. From 2015 onwards, immediately prior to the pandemic, youth unemployment declined, and signs of economic recovery were clear. The first Costa administration prioritized permanent contracts for young people, mainly through wage subsidies, while gradually re‑elevating innovation and education, with a particular focus on digital skills, albeit at a more modest pace than that of 2005–2011.

Youth-oriented ALMPs in Spain and the national growth strategy (2000-2019)

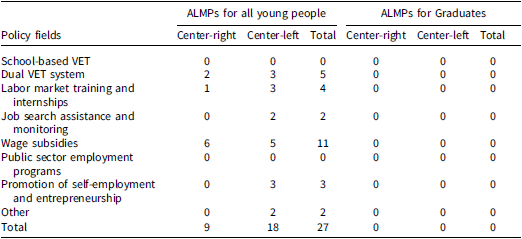

Table 4 shows that Spain implemented 27 youth-oriented ALMPs between 2000 and 2019, most falling under “wage subsidies” and “labour-market training and internships”. More noteworthy, however, is the substantive content: Spain’s 2008 reform establishing a dual-VET system represents its most emblematic and ambitious intervention. Prior to 2008, only one measure (in 2006) sought to promote entrepreneurship and self-employment. Below, we summarize the main features of the 2008 reform and its alignment with Spain’s growth strategy.

Table 4. Youth-oriented ALMPs in Spain between 2000 and 2019

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on the LABREF database (European Commission, 2021).

Note: See Online Appendix A for further details. In the appendix, each policy is coded according to whether it targets university graduates, which political party enacted the reform, and the policy field to which it belongs. Graduate targeting is determined by examining the policy descriptions provided in the LABREF database and cross-referencing them with the corresponding official documents. For party classification, we identify the governing party responsible for the reform and use the PARLGOV database to categorize it as either center-left or center-right.

Scope note: VET categories denote labor‑market instruments (e.g., apprenticeship contracts, PES‑funded bridging courses) and exclude general education reforms.

Workplace-based training remained a consistent policy priority throughout the period, yielding several landmark programs. In 2008, the socialist government overhauled the VET system by creating 25 autonomous National VET Reference Centers and easing access to initial and intermediate qualification programs (Spanish Royal Decree 229/2008). These new centers were charged with designing and delivering innovative, experimental training under the National List of Professional Qualifications. Public grants enabled workers aged 18 to 24 to acquire these qualifications while remaining in employment.

Following the 2011 election of a center-right coalition, three further reforms refined workplace training. The training and apprenticeship contract was redesigned to combine paid employment with VET for low-skilled young workers (initially aged 16–25, later extended to 30 until 2013) (Spanish Royal Decree 10/2011). Trainees’ working hours were capped at 75 per cent of full-time work, and training was delivered via the national VET network, culminating in recognized professional qualifications. Employers received fiscal incentives for hiring individuals over 20 and additional bonuses – first €1,000, then €1,500 – for converting apprenticeships into permanent contracts. During the sovereign-debt crisis, these measures were expanded to increase permissible working hours, raise the age limit, and allow apprentices to be rehired while pursuing further qualifications (Spanish Royal Decree 3/2012). Social-security contributions were reduced or waived for both firms and trainees. Later in 2012, legislation was enacted to scale up dual training through a combination of formal VET and apprenticeships, explicitly aimed at establishing a dual-VET system anchored by apprenticeship contracts (Spanish Royal Decree 1529/2012). Many of these provisions were incorporated into the Youth Guarantee in 2014 (Artiles et al. Reference Artiles, Lope, Barrientos, Moles and Carrasquer2020).

In 2018, the socialist government launched the Youth Employment Plan 2019–2021, reaffirming its commitment to dual training by pledging €165 million for apprenticeship contracts and €360 million for mixed employment-and-training programs between 2019 and 2021 (Spanish Ministerial Decree 7/12/2018).

Given Spain’s annual expenditure of approximately €1.2 billion on ALMP training measures, these investments underscore the centrality of dual training (European Commission, 2022). Participant data further underscore the significance of these policies. Arco-Tirado et al. (Reference Arco-Tirado, Fernández-Martín, Jagannathan and Jagannathan2021) report that enrolment in dual-VET in Spain rose from 4,292 in 2013 to 23,974 in 2017. Drawing on European Commission data (2022), we calculated the proportion of students enrolled in these programs relative to the total number of young participants in ALMPs within the training category. This measure reveals that the share of young people attending dual-VET, as a percentage of all ALMP training participants, increased from 4.8 per cent in 2013 to 32.7 per cent in 2017. Notably, this agenda was initiated by a socialist administration in 2008, further advanced by a center-right government in 2011–12, and maintained by the Sánchez government in 2018.

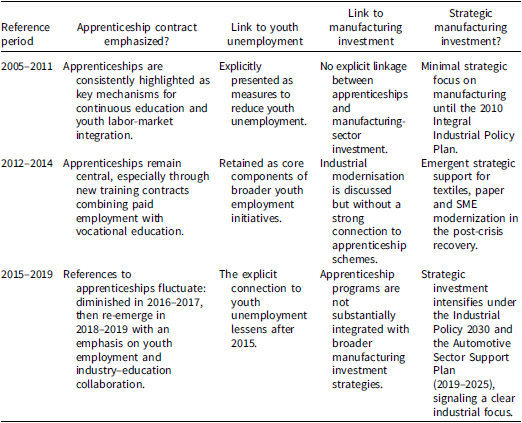

Our content analysis of the NRPs (Table 5) reveals that apprenticeships consistently occupied a prominent strategic position and were repeatedly linked to the reduction of youth-unemployment, highlighting their recognized role in addressing young people’s labor-market challenges. Although no direct correlation between apprenticeships and manufacturing investment was observed, overall investment in the manufacturing sector rose steadily. This finding accords with scholarship documenting Spain’s efforts to strengthen its industrial base, particularly the automotive sector, through FDI-led, export-oriented growth (Bulfone and Tassinari Reference Bulfone and Tassinari2021; OECD 2015). Similar trends emerged in chemicals and other industries, suggesting that dual-VET and apprenticeships complemented the expansion of medium- and high-technology manufacturing. Indeed, roughly 70 per cent of dual-VET projects are in industrial fields (energy, textiles, metal, machinery, chemicals, electronics, automotive) because these larger, more technology-advanced firms have the capacity to invest intensively in on-the-job training (Artiles et al. Reference Artiles, Lope, Barrientos, Moles and Carrasquer2020: 77).

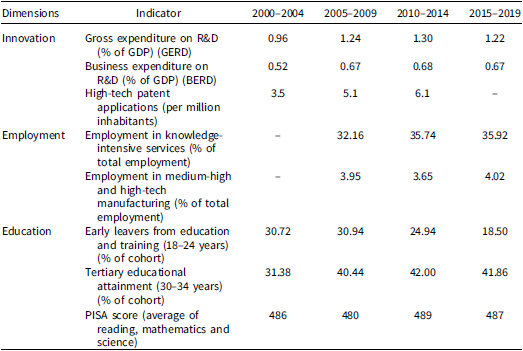

Table 5. Content analysis of Spanish National Reform Programmes (2005–2019)

The data delineated in Table 6 corroborate the analyses presented, particularly when juxtaposing key indicators that evaluate the transition toward a knowledge-based economy in Portugal and Spain (Tables 3 and 6). Striking disparities are evident, notably within the domains of innovation, education, and manufacturing. Portugal manifests a substantial commitment to innovation, as evidenced by its significant investments in R&D. While Spain’s GERD as a percentage of GDP rose from 0.96% during 2000–2004 to a peak of 1.30% between 2010–2014, followed by a slight decrease to 1.22% in the 2015–2019 period, the corresponding figures for Portugal indicate a more rapid and sustained growth trajectory. This trend underscores Portugal’s proactive stance in fostering innovation-driven development. In the educational sphere, Portugal’s investments have yielded notable advancements. Spain has achieved a reduction in early school leaving rates from 30.72% to 18.50% and an increase in tertiary educational attainment from 31.38% to 41.86% over the same period. While these improvements are commendable, Portugal’s accelerated progress in reducing early school leaving rates and enhancing higher education attainment highlights the efficacy of its educational reforms and investment strategies. Conversely, Spain has exhibited enduring strength within the manufacturing sector. Employment in medium-high and high-technology manufacturing industries has remained relatively stable, increasing from 3.95% during 2005–2009 to 4.02% between 2015 and 2019. This stability reflects the resilience of Spain’s industrial base, which continues to constitute an important component of its economy. In conclusion, Portugal’s significant advancements in innovation and education underscore its assertive investment strategies, whereas Spain’s enduring strengths are rooted primarily in the sustained robustness of its manufacturing sector.

Table 6. Principal indicators assessing the transition to a knowledge-based economy in Spain (2000–2019)

Source: Eurostat (2024; 2025a–d); OECD (2001; 2004; 2007; 2010; 2013; 2016; 2019b).

Notes: “High-tech patent applications” covers data up to 2013; the 2010–2014 average therefore uses only 2010–2013 figures. Employment-by-sector data start in 2008; accordingly, the 2005–2009 averages are based on 2008 and 2009 only. PISA assessments were conducted in 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009, 2012, 2015 and 2018; period averages reflect the available survey years.

There was a broad consensus among politicians and social partners regarding the actors supporting investment in dual training. We begin by highlighting statements made by members of successive governments, followed by an examination of the positions adopted by the social partners. In 2009, the Spanish Prime Minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, emphasized the need to encourage firms to participate in the planning and delivery of vocational training. In the same statement, he linked this initiative to the imperative of tackling youth unemployment and stimulating investment in the manufacturing sector (Heraldo 2009). Subsequently, in 2015, under the leadership of Mariano Rajoy, the People’s Party (PP) government stated that “dual vocational training, which has been a great success both in Germany and in Austria, is also improving in our country” (Rajoy Reference Rajoy2015). In the context of the 2015 national election campaign, Pedro Sánchez declared: “we need a strong Spain, and for that, a strong industry … I want that for Spain as well… for Spain to be an industrial power in 10 years’ time.” To achieve this, he advocated dual vocational training alongside an industrial policy focused on investment in R&D&I and Industry 4.0 (Servimedia 2015).

Regarding social partners, both employers (Spanish Chamber of Commerce 2016) and the two main trade union confederations – the General Workers’ Union (UGT-ES) (2018) and the Trade Union Confederation of Workers’ Commissions (CCOO) (2014; 2018) – expressed support for the transition toward dual-training. Nevertheless, as Artiles et al. (Reference Artiles, Lope, Barrientos, Moles and Carrasquer2020: 79) observed, “trade unions complain that they participate only in institutional consultations and not in the planning or development of dual VET”. Their involvement therefore differs from that seen in countries characterized by collective skill formation systems, where trade unions play a more active role (Busemeyer and Trampusch Reference Busemeyer, Trampusch, Busemeyer and Trampusch2012).

In summary, Spain’s dual-VET system based on apprenticeships emerged as the country’s defining youth-oriented ALMP, consistently pursued by both socialist and center-right administrations to combat youth unemployment and support manufacturing development. This continuity was underpinned by a stable coalition of employer organizations – especially in the automotive and other industrial sectors – alongside the Chamber of Commerce and consultative union confederations, which ensured the maintenance of dual‑VET and apprenticeship contracts across partisan alternation from 2008 to 2019. By aligning workplace‑training instruments with industrial upgrading and an FDI‑driven export strategy, this coalition sustained a coherent dual‑VET trajectory that contrasted with Portugal’s shifting priorities and remained the core youth employment policy regardless of the governing party.

Discussion

This study tested five hypotheses concerning the drivers of youth-oriented ALMPs in Portugal and Spain. Hypothesis 1 (Partisan Politics) posits that left-wing governments prioritize ALMPs aimed at reducing registered unemployment among core labor-force participants, particularly through human capital investment and employment assistance, whereas right-wing administrations favor labor supply expansion measures, such as employer incentives, self-employment promotion, and occupation-focused schemes (Cronert Reference Cronert2019). Portugal broadly conforms to this pattern: the 2005–2011 socialist government introduced a series of graduate-targeted internships aligned with a knowledge-based growth strategy, while the 2011–2015 center-right coalition pivoted toward broad-based wage subsidies, tax relief for employers, and self-employment grants that aimed to expand labor supply. In Spain, however, the consistent cross-partisan support for dual-VET and apprenticeship contracts, initially launched by the socialist government and later expanded by the center-right, suggests a bipartisan consensus around a human capital strategy tied to industrial competitiveness. This continuity, and the absence of a clear partisan shift in program type, indicates that partisan politics cannot account for Spain’s ALMP orientation. Consequently, H1 is confirmed for Portugal but not for Spain.

Turning to Hypothesis 2 (Policy Diffusion and Institutional Legacies), both countries share broadly similar Southern welfare regimes, with modest institutional complementarities (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990; Hall and Soskice Reference Hall, Soskice, Hall and Soskice2001). OECD and EU activation guidelines, promoting vocational training and internships, aligned with the institutional frameworks of both states (European Commission 2004; OECD 2006). However, these diffusion pressures yielded divergent outcomes, indicating that similar institutional legacies did not produce convergent ALMP designs. H2 is therefore not supported.

Hypothesis 3 (Employers’ Involvement) receives only limited support. While Portuguese SMEs engaged with INOV-JOVEM internships and Spanish manufacturers underpinned apprenticeship schemes, neither country has entrenched corporatist arrangements (Molina Reference Molina2014). Moreover, employer engagement declined in Portugal once growth strategies shifted post-2011. Employers influenced specific programs but did not act as consistent, independent drivers of national ALMP strategies. Thus, H3 is only weakly confirmed.

Evidence for Hypothesis 4 (Union Involvement) is mixed. In Spain, trade unions (UGT-ES and CCOO) publicly supported a high-quality dual-VET model, advocating for regulatory oversight and institutional coherence (CCOO 2018; UGT-ES 2018). However, their formal role remained consultative rather than participatory (Artiles et al. Reference Artiles, Lope, Barrientos, Moles and Carrasquer2020). In Portugal, union involvement in this area was similarly limited (DGERT 2021). While UGT-PT endorsed dual training in principle, CGTP-IN expressed skepticism toward it (UGT-PT 2024; CGTP-IN 2013). Nonetheless, it is important to note that CGTP-IN’s opposition to internships targeting graduates did not prevent their implementation; such schemes were ultimately adopted and expanded. As a result, Portuguese ALMPs remained largely state- and employer-driven. In summary, although union engagement contributed to the legitimization of dual-VET policies in Spain, it did not decisively influence the policy divergence between the two countries, as the Socialist government in Portugal could have proceeded with a dual-training reform based on UGT-PT’s support. Therefore, the evidence offers only partial support for H4. While unions played a supportive or oppositional role in legitimizing specific initiatives, their limited institutional leverage in both countries meant they were not decisive actors in shaping the overall trajectory of ALMP reform.

By contrast, Hypothesis 5 (Growth Strategies) receives compelling confirmation. Portugal’s 2005–2011 strategy explicitly prioritized knowledge-intensive services, leading to targeted internships and innovation schemes for graduates in ICT, engineering, and science. Spain, meanwhile, pursued a coherent, FDI-driven manufacturing strategy supported by a persistent investment in dual-VET and apprenticeships (Artiles et al. Reference Artiles, Lope, Barrientos, Moles and Carrasquer2020). This divergence aligns directly with the strategic objectives of each country’s growth model. H5 thus provides the most robust explanation for the contrasting orientations of youth-oriented ALMPs in the two cases.

In short, while each of the first four hypotheses offers partial insights into ALMP design, it is the growth strategy hypothesis (H5) that most convincingly explains why two otherwise comparable Southern European countries pursued markedly different activation trajectories.

Conclusions

Between 2000 and 2019, Portugal and Spain weathered analogous macro-economic shocks – most notably the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2011 sovereign-debt crisis – which drove youth unemployment to unprecedented levels across all educational strata. In response, both governments expanded their ALMPs through training programs and wage subsidies. However, the substantive design of these measures diverged markedly. Spain’s successive socialist and center-right administrations coalesced around a dual-VET and apprenticeship framework, both to mitigate immediate joblessness among young people and to bolster its FDI-driven manufacturing base (Artiles et al. Reference Artiles, Lope, Barrientos, Moles and Carrasquer2020). By contrast, Portugal’s socialist government from 2005 to 2011 embedded ALMPs within a coherent knowledge-economy growth strategy, rolling out graduate-targeted internships, most notably INOV-JOVEM, alongside complementary reforms in R&D, innovation funding and higher-education partnerships to accelerate the transition to knowledge-intensive services.

This policy divergence underscores our principal theoretical contribution. Drawing on Hassel and Palier’s (Reference Hassel, Palier, Hassel and Palier2021) distinction between growth regimes and growth strategies, we demonstrate that ALMP orientation is shaped less by structural economic factors or partisan affiliation alone than by the deliberate set of strategic choices through which governments steer their economies toward specific growth regimes. Portugal’s “knowledge-services” strategy, for example, combined higher-education linkages, innovation policies, and targeted internship schemes, whereas Spain’s “manufacturing-export” strategy placed dual-VET and apprenticeships at its core. Our analysis thus advances the literature by identifying growth strategies as the mechanism through which macro-economic objectives are translated into concrete welfare-state instruments.

The mechanism we identify should extend to Italy and Greece, that is, the remainder of Southern Europe. Where national strategies leaned toward knowledge‑intensive services, we would expect more graduate‑oriented internships; where strategies favored manufacturing competences, dual‑VET/apprenticeship instruments should be more salient. Future work could test these scope conditions explicitly.

Nonetheless, several limitations qualify our conclusions. First, our focus on only two Southern European cases may limit the generalizability of our findings to contexts with different institutional legacies. Second, by restricting the period to 2000–2019, we omit the significant policy innovations prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, our national-level approach risks obscuring critical regional heterogeneity, particularly within Spain’s autonomous communities.

These findings yield clear policy implications. Activation measures must be closely aligned with broader growth imperatives. Economies aspiring to nurture knowledge-intensive sectors should invest in graduate internships, R&D partnerships, and innovation ecosystems. In contrast, countries aiming to sustain manufacturing competitiveness should strengthen dual-VET and apprenticeship pathways in close collaboration with industry. Rather than treating ALMPs as technocratic tools or one-size-fits-all solutions, policymakers should design them as instruments that reflect and reinforce national growth strategies.

Future research should further investigate the role of political agency in aligning activation policies with growth strategies. While this study shows that partisan preferences and institutional legacies only partially explain policy divergence, it also highlights the capacity of political actors, especially governing elites, to steer policy design in line with macroeconomic priorities. Comparative studies could explore how governments build coalitions, manage policy trade-offs, and deploy ALMPs as strategic tools within broader economic agendas. A closer examination of agenda-setting processes, elite discourses, and bureaucratic leadership would deepen our understanding of how activation instruments are selected, sequenced, and sustained over time.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X25100949.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods; however, two online appendices are provided, containing a list of youth-targeted ALMPs and relevant excerpts from the NRPs.

Funding statement

This work was funded by Portuguese public funds through FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology, both via the SOLID-JOB project (project no. 06230; Reference: PTDC/CPO-CPO/6230/2020) and through the Youth Employment Observatory (funding reference: UID/3127/2025, DINÂMIA’CET).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Paulo Marques is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Economy at Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL). His research focuses on labor market policies and labor market segmentation and contributes to the field of comparative political economy. His work has been published, among others, in the Socio-Economic Review, Comparative European Politics and European Journal of Industrial Relations. His email address is paulo_miguel_marques@iscte-iul.pt.

Pedro Videira is a researcher at DINÂMIA’CET (Centre for Socioeconomic and Territorial Studies) and at CIPES (Centre for Research in Higher Education Policies). His main research interests lie in the field of higher education policies, namely changes to the academic profession and graduates’ employability and skills development. He has published several articles and book chapters on those subjects. His email address is pedro.videira@iscte-iul.pt.